1. Introduction

The apricot (

Prunus armeniaca L.) is a significant temperate fruit species that is extensively grown throughout Europe and Asia because of its early harvesting, nutritional benefits, and versatility for both fresh eating and processing [

1,

2]. In Romania, the cultivation is primarily found in the western and southern areas, where it contributes to rural development and the diversification of fruit production systems [

3]. Nevertheless, recent fluctuations in climate—marked by erratic rainfall, extended droughts, and increasing summer temperatures—have heightened the necessity for efficient irrigation to sustain stable growth and ensure high-quality nursery plants.

Agriculture constitutes over 70% of the global freshwater usage, and nurseries are under growing pressure to boost water efficiency due to competing demands from municipal and industrial sectors [

4]. Diminishing groundwater supplies, limited access to surface water, and seasonal restrictions on irrigation have rendered water availability increasingly erratic [

5]. The effects of climate change have escalated summer evapotranspiration levels, increasing the need for irrigation water at a time when supplies are most limited [

6,

7]. These issues underscore the necessity for irrigation methods that improve water-use efficiency while maintaining sufficient soil moisture for plant growth.

Managing water resources in nurseries poses specific challenges. Young plants possess shallow and underdeveloped root systems, making them particularly vulnerable to short-term changes in soil moisture levels [

8]. Over-irrigation can result in waterlogging, the loss of nutrients through leaching, and a decrease in soil aeration, while insufficient watering causes water stress, hampers shoot development, restricts branching, and undermines structural integrity [

9,

10,

11]. Recent reviews increasingly highlight the importance of utilizing advanced irrigation methods and precise scheduling to preserve plant quality and minimize water waste [

13].

The availability of water plays a crucial role in apricot physiology, impacting photosynthesis, leaf growth, biomass development, and shoot extension. While apricot trees are generally regarded as moderately drought-resistant, they are particularly vulnerable to reductions in soil moisture during active growth phases [

14,

15,

16]. In temperate regions, the annual water needs typically lie between 600 and 700 mm, influenced by soil types and evaporation rates, with the highest demands occurring during the flowering stage, shoot growth, and fruit development [

17,

18]. There is significant genetic diversity among apricot varieties regarding traits like osmotic adjustment, stomatal regulation, hydraulic control, and drought tolerance, resulting in distinct growth and water usage patterns specific to each cultivar [

19,

20]. This diversity highlights the necessity for irrigation approaches that are customized for different genotypes, particularly in nursery settings where consistent growth is critical.

Irrigation management has demonstrated its impact on plant physiology, yield, and fruit quality in apricot and other

Prunus species, with regulated deficit irrigation methods capable of sustaining vegetative growth while enhancing water-use efficiency [

21,

22,

23]. These techniques emphasize the optimization of irrigation depth—the amount of water supplied during each irrigation session—to align with the water needs of the plant and minimize unnecessary losses from evaporation or deep percolation. Although there has been significant advancement in research on orchard irrigation, there is still limited understanding of how varying irrigation depths affect the initial vegetative growth in nursery-raised trees. This gap in knowledge is particularly important, as young plants need steady but not excessive water supplies to cultivate structurally sound and well-branched canopies.

The development of branches and shoots during the initial growth phases is crucial for determining canopy structure, future productivity, and successful planting [

24]. In apricot trees, sufficient water availability promotes the initiation and extension of primary shoots, which ultimately influence the future architecture of the orchard and enhance early fruiting potential [

24,

25]. Genetic variations also play a role in branch development, with certain cultivars exhibiting greater adaptability in conditions of limited water supply [

26]. Therefore, it is vital to understand how irrigation depth interacts with the traits of different cultivars during the nursery stage to generate high-quality planting materials.

Effective management of irrigation is increasingly acknowledged as a fundamental aspect of sustainable horticultural production. Advanced techniques such as regulated deficit irrigation (RDI), partial root-zone drying, and scheduling based on soil moisture have demonstrated enhancements in water-use efficiency in mature orchards, while still achieving acceptable yields [

27,

28,

29]. These strategies highlight the necessity of modifying irrigation depth—the volume of water applied during each irrigation event—to align more closely with the water needs of plants and reduce losses through evaporation, runoff, or deep percolation. However, there is significantly less understanding of how varying irrigation depths affect vegetative growth during the nursery phase, where the physiological needs and root system development of young plants differ greatly from those of fully grown trees.

Nursery systems present specific challenges because young trees have shallow and limited root structures, making them particularly sensitive to changes in soil moisture and heavily reliant on a steady supply of water. Insufficient irrigation can hinder shoot growth and decrease biomass production, whereas too much water can lead to nutrient leaching, inefficient water use, and weak plants that have limited adaptability following transplantation. The early development of shoots and branches is critical in determining the architecture of the canopy and the long-term productivity of fruit trees [

30]. In apricot trees, the availability of water has a significant impact on the initiation and growth of primary shoots, which in turn affects the design of the orchard, the balance of the canopy, and the potential for fruit production [

31].

Variations in genotype also play a significant role in how plants respond vegetatively under conditions of limited or ample water supply [

32]. Research on apricot cultivars from Romania reveals notable agro-morphological differences, especially in environments with variable water availability. Since the formation of branches affects light capture, structural balance, and the capacity for early fruiting, the aim of producing well-branched and morphologically consistent nursery plants is crucial in propagation systems [

33,

34]. However, there has been comparatively little research on how the depth of irrigation interacts with cultivar-specific physiological characteristics to influence branch development in open-field nurseries. This gap highlights the necessity for irrigation strategies tailored to specific genotypes that promote both efficient water usage and high-quality plant growth in the early stages.

This study aims to fill a research gap by investigating how four different irrigation depths influence branch growth and vegetative performance in two apricot varieties from Romania, ‘Excelsior’ and ‘Favorit’, which are grafted onto Prunus cerasifera rootstock. The objectives were to: (i) measure the effects of irrigation depth on overall branch length, (ii) evaluate how each cultivar specifically reacts to managed water supply, and (iii) identify irrigation thresholds that foster ideal structural growth while enhancing water-use efficiency. These results support the planning of precision irrigation in apricot nurseries and promote sustainable propagation practices amid rising climatic fluctuations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site: Soil and Climate Conditions

The study took place in 2024 at a commercial nursery in northwestern Romania (47°03′ N, 21°56′ E), an area noted for its temperate continental climate marked by hot summers and inconsistent rainfall patterns. This region is situated within a lowland geomorphological zone with elevations ranging from 80 to 190 meters. Climate variables such as daily air temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and relative humidity were monitored using an automatic weather station (Bresser, Germany) located close to the experimental site.

Table 1 illustrates the monthly climate data for the 2024 growing season. The mean annual temperature was recorded at 12.6 °C, with August identified as the hottest month at 24.1 °C, while December was the coldest at 1.2 °C. The total annual precipitation was 637.2 mm; however, its distribution throughout the year was highly irregular. July experienced the highest amount of precipitation at 127.6 mm, which primarily fell as brief but intense storms followed by prolonged dry periods. Due to elevated levels of evapotranspiration and rapid drying of the soil during the summer months, additional irrigation was required to ensure sufficient soil moisture for growth.

The soil at this location is identified as a Luvic Gleysol, featuring a profile that includes Am (0–30 cm), ABw (30–60 cm), and BvG (60–90 cm) horizons. The top layer is medium-loam, containing 2.1% organic matter and a pH level of 6.8. The field capacity of the topsoil is around 32%, while the wilting point is approximately 17%. The subsurface horizons show moderate drainage restrictions, which can lead to temporary water saturation after heavy rainfall. These traits suggest a medium water-holding capacity and highlight the necessity for careful irrigation management to prevent moisture depletion or excessive water accumulation.

2.2. Plant Material and Experimental Design

The research involved one-year-old Prunus armeniaca L. liner plants from two Romanian varieties, ‘Excelsior’ and ‘Favorit’. All trees were grafted in 2023 onto a consistent Myrobalan (Prunus cerasifera) rootstock to reduce variability related to the rootstock. The grafting was conducted by the same technician using uniform methods, and only healthy, visually consistent plants were chosen. The trees were cultivated in an open-field nursery, organized in single rows with a spacing of 0.8 m × 0.3 m. The experiment utilized a randomized complete block design (RCBD) that included four irrigation treatments and three replications for each cultivar. Each replication comprised ten plants. The four irrigation treatments included 0, 10, 20, and 30 mm of water applied in each irrigation cycle. These treatments roughly equated to 0%, 50%, 75%, and 100% replenishment of the soil water deficit in the 0–30 cm layer—reflecting typical nursery irrigation levels ranging from deficit to adequate supply.

2.3. Irrigation System and Soil- Water Monitoring

Irrigation was carried out using a drip system fitted with inline emitters that provided 2 L h⁻¹. Soil moisture levels were tracked using two tensiometers installed at a depth of 20 cm on opposite sides of the representative plant in each plot. Readings from the tensiometers were recorded daily, and irrigation was started whenever soil moisture dropped below 60–65% of field capacity, adhering to moisture-based scheduling guidelines typically recommended for precision irrigation. Throughout the 2024 growing season, irrigation was applied seven times for each of the irrigated treatments (10, 20, and 30 mm), with each application delivering the full designated irrigation amount. This method of monitoring facilitated consistent triggering of irrigation events and a dependable evaluation of soil-water depletion across all treatment plots. The reference evapotranspiration (ETo) was determined using climatic data along with the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith equation. Crop evapotranspiration (ETc) was calculated using a crop coefficient (Kc = 0.70–0.80) appropriate for young apricot trees during their active growth phase [

35]. Irrigation amounts were selected to simulate realistic nursery conditions, varying from rainfed scenarios (0 mm) to complete replenishment (30 mm).

2.4. Water Consumption Measurements

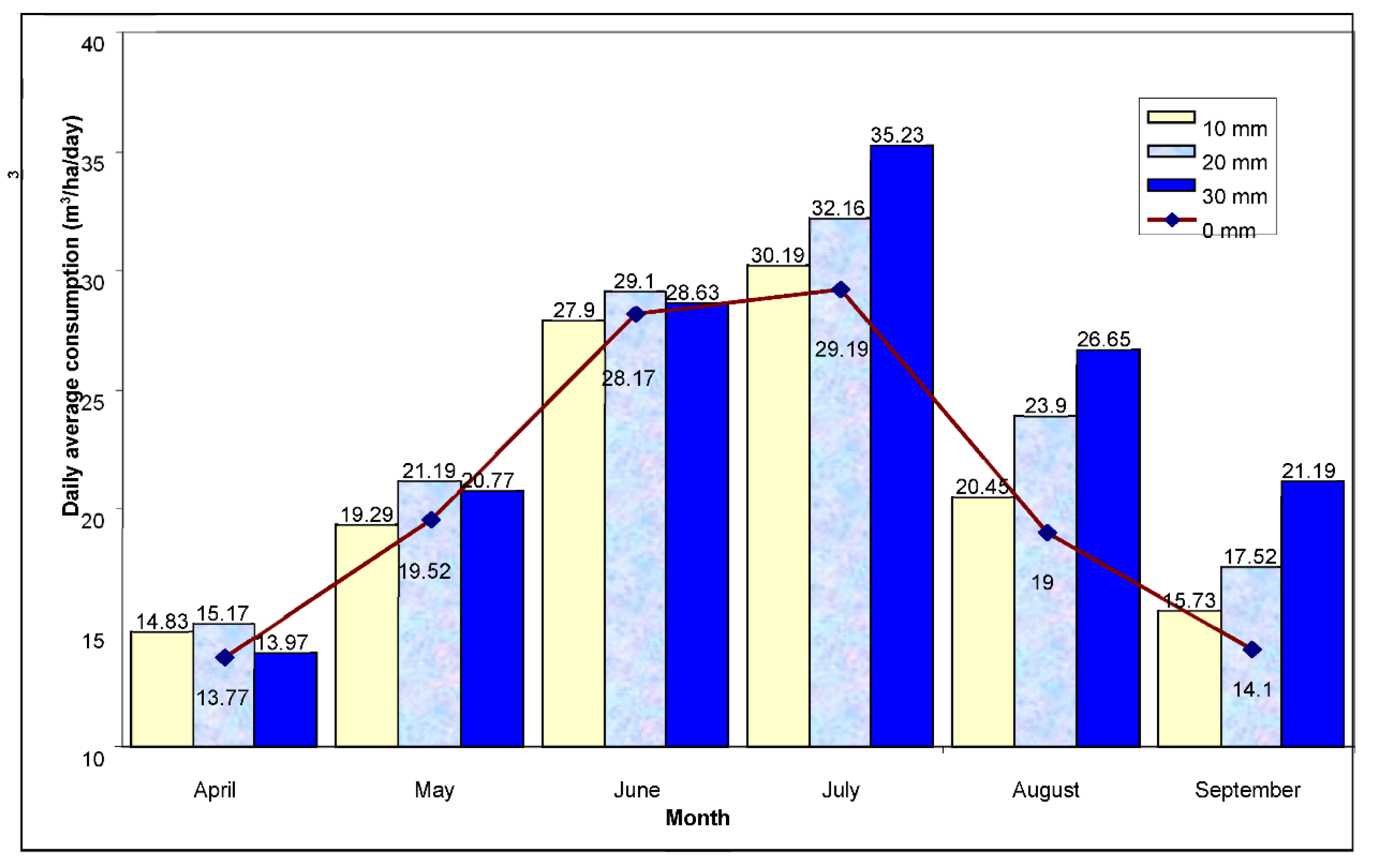

Daily water usage in the field was monitored throughout the season (

Figure 1). The values fluctuated between 13.77–15.17 m³ ha⁻¹ in April, peaking at 29.19–35.23 m³ ha⁻¹ in August, depending on the treatment applied. Water usage trends were influenced by both climatic requirements and the irrigation strategy employed. Soil moisture reserves in the top 30 cm layer showed moderate variability (1,490–2,390 m³ ha⁻¹), indicating a stable but not overly high capacity for water retention.

2.5. Morphological Measurements

At the conclusion of the growing season (October 2024), the extent of vegetative growth was evaluated by measuring the total length of all first-order shoots per plant (cm). This measurement serves as a reliable indicator of canopy initiation potential and is commonly utilized in assessing nursery quality. One plant demonstrating typical vigor and height in relation to the group was selected from each replicate for precise measurement to ensure representative sampling. No baseline branch-length measurements were recorded at the season’s outset, as the focus of the study was to quantify total seasonal growth across different irrigation levels. During the experiment, the integrity of the graft union and plant survival were continuously monitored. There were no indications of incompatibility or variations in mortality rates between cultivars.

2.6. Lp- Norm Index Calculation

To deliver a holistic evaluation of vegetative performance, the Lp-norm index (p = 2.5) was applied. The values of total branch length were adjusted to fit within the [0,1] range: Xi = (Ti-Tmin)/ (Tmax-Tmin)

Where Ti represents the total length of the shoot for plant i.

The Lp-Norm was calculated using the general p-space normalization formula: . In this research, an Lp-norm value of p=2.5 was utilized to calculate the Lp-norm values for each combination of Cultivar and Water_Norm, as shown in Figure 3.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were examined using a two-way ANOVA, where cultivar and irrigation treatment were treated as fixed factors. If significant effects were found (p < 0.05), means were differentiated using Tukey’s HSD test. The analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics v26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Results are presented as means ± standard error (SE).

3. Results

3.1. Soil Water Balance and Water Consumption Under Different Irrigation Regimes

At the start of the 2024 growing season, the soil water reserves in the top 30 cm were between 2367 and 2458 m³ ha⁻¹, which represented 84–88% of field capacity—ideal moisture conditions for the early growth of apricot liners (

Table 2). Due to adequate rainfall in April and early May, soil moisture remained consistent, ranging from 2380 to 2443 m³ ha⁻¹. Significant rainfall during May and June resulted in further increases in soil reserves, reaching levels of 2743 to 2784 m³ ha⁻¹ by the end of June. In July, high temperatures along with low rainfall caused a dramatic decrease in soil moisture, falling below 2112 m³ ha⁻¹, the point at which water stress starts to impede vegetative growth. As a result, irrigation became necessary in July to sustain plant hydration. Following the application of the 10, 20, and 30 mm treatments, soil reserves rose to between 2158 and 2204 m³ ha⁻¹ by the end of July.

In August, soil moisture experienced a significant reduction due to high temperatures and a lack of rainfall, dropping to between 1491 and 1652 m³ ha⁻¹—far below field capacity. Irrigation replenished the soil water levels to a range of 1952 to 2391 m³ ha⁻¹ based on the treatment applied, ensuring that plants had sufficient moisture during peak periods of evapotranspiration.

By September, the shortage of water became more severe, as evidenced by further declines in reserve levels, especially in the non-irrigated treatment which recorded 1494 m³ ha⁻¹. In contrast, the 30 mm irrigation treatment kept soil reserves above 2046 m³ ha⁻¹, effectively averting late-season moisture stress.

In summary, the water balance data indicates that rainfed conditions led to extended moisture deficits, whereas irrigation-maintained soil reserves at nearly optimal levels for continued vegetative growth.

3.2. Effects of Irrigation on Total Branch Growth

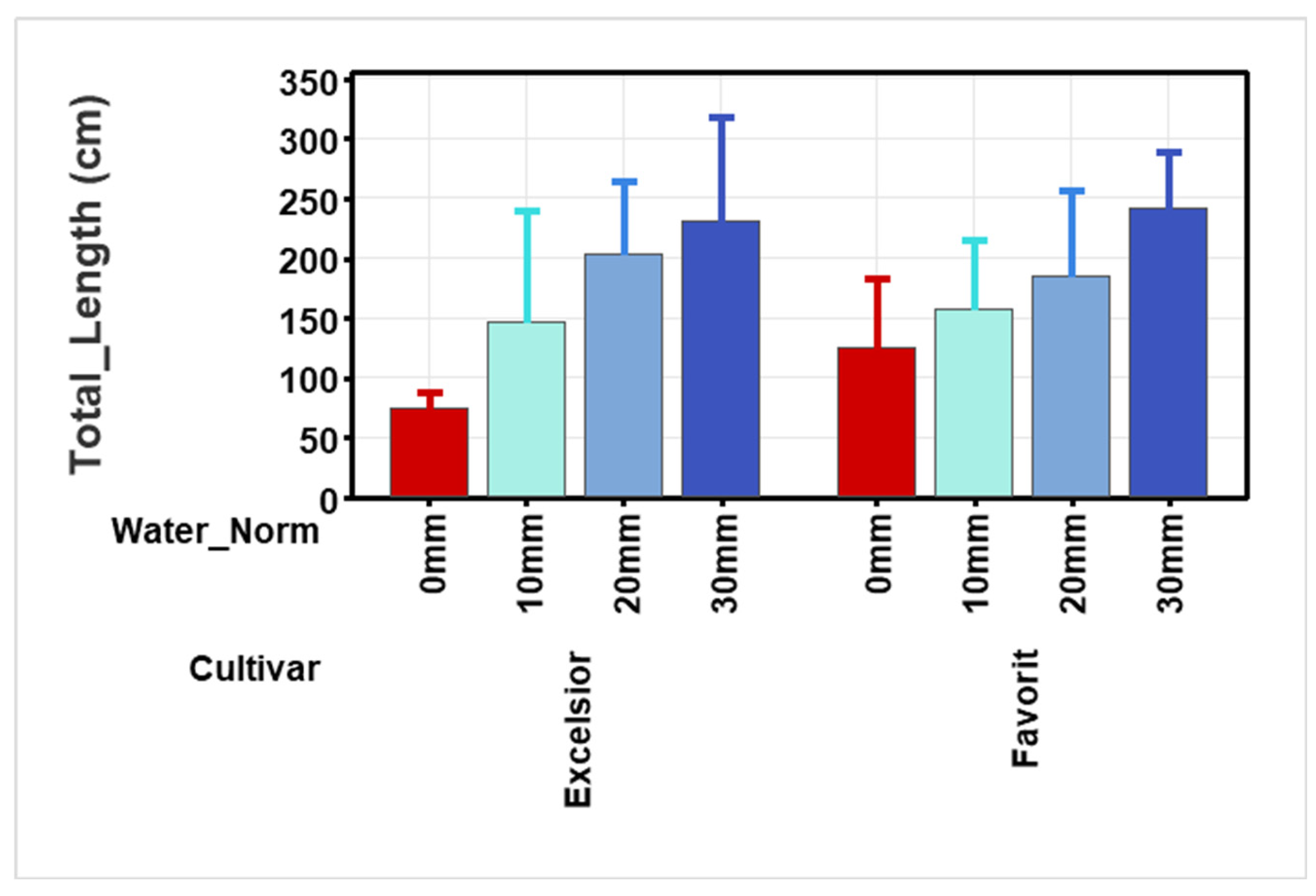

Irrigation had a beneficial impact on the overall length of branches in both cultivars, even though the effect was not statistically significant at p > 0.05 (

Figure 2). Nonetheless, distinct developmental patterns were observed.

For the ‘Excelsior’ variety, branch length rose from roughly 80 cm in the non-irrigated treatment to 150 cm at 10 mm and increased to about 200 cm with 20 mm irrigation. A subsequent rise to approximately 230 cm was noted at the 30 mm level. The standard errors expanded at higher irrigation amounts, indicating greater variability among the plants.

In the case of ‘Favorit’, the initial branch length at 0 mm irrigation was higher (≈130 cm) than that of ‘Excelsior’. Growth progressed modestly to about 160 cm at 10 mm and 190 cm at 20 mm, followed by a more substantial increase to around 230 cm under the 30 mm regimen. In comparison to ‘Excelsior’, the variation among replicates was less pronounced at intermediate irrigation levels, suggesting a more consistent response.

The two cultivars exhibited different growth behaviors. ‘Excelsior’ demonstrated a more pronounced reaction to increased irrigation, almost tripling its branch length from 0 mm to 30 mm. On the other hand, ‘Favorit’ showed a narrower range of response, with only slight increases across irrigation levels and relatively stable growth under low-water conditions. These observations underline the differing water sensitivity characteristics: ‘Excelsior’ thrived significantly with moderate to high irrigation, while ‘Favorit’ sustained consistent growth even with limited water availability.

3.3. Vegetative Performance Assessed Using the Lp- Norm Index

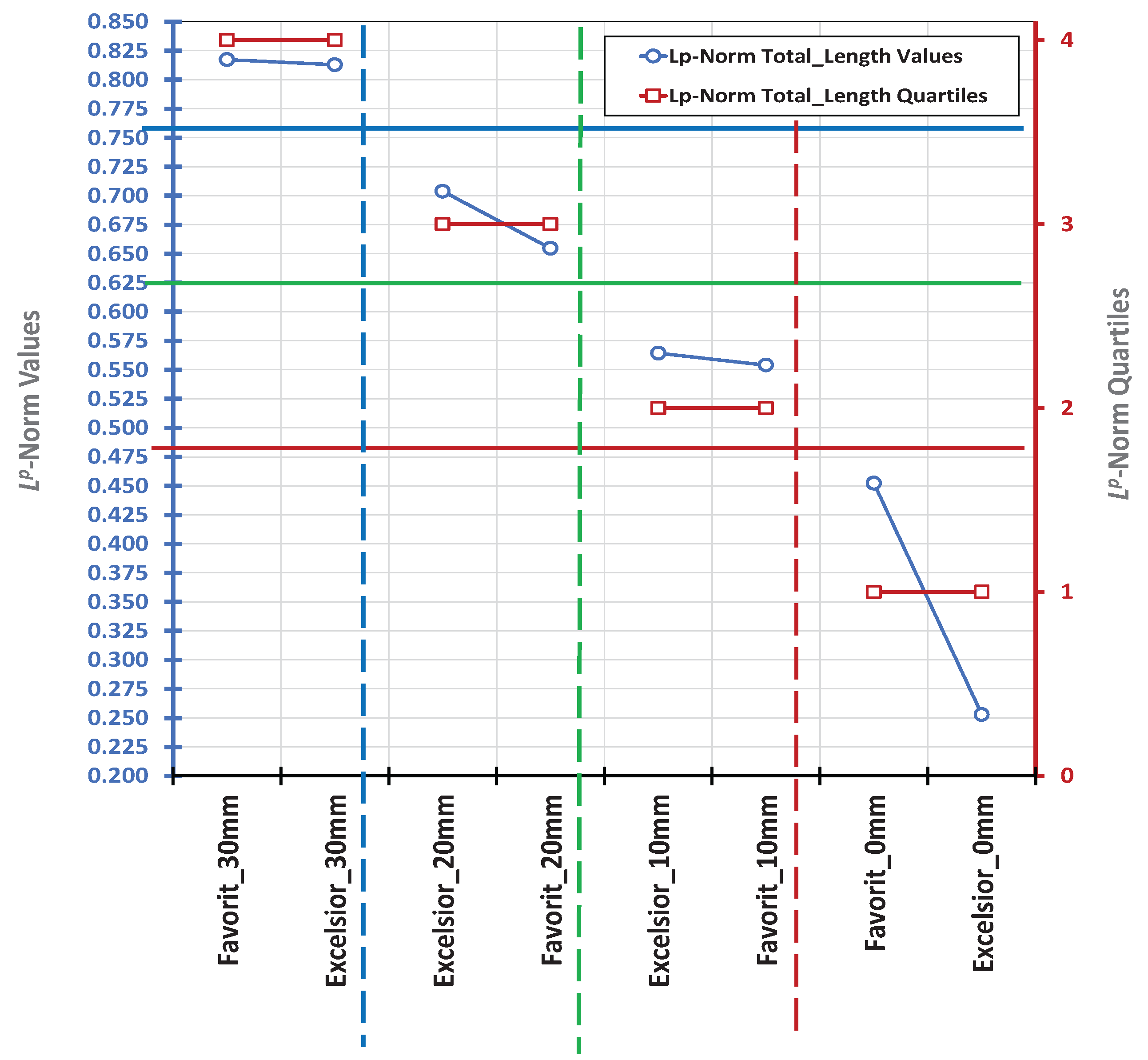

The normalized Lp-norm values (p = 2.5) indicated a distinct, positive, and progressive correlation between irrigation depth and cumulative vegetative growth across both apricot cultivars, highlighting the critical importance of regulated soil water replenishment in influencing shoot development in nursery conditions (

Figure 3). In the absence of irrigation (0 mm), the plants experienced significant water deficit stress, as evidenced by the lowest Lp-norm values—around 0.25 for ‘Excelsior’ and 0.45 for ‘Favorit’. These reduced values are associated with limited branch formation and restricted shoot elongation, which are common physiological reactions when soil moisture drops below the levels necessary for sustaining proper plant water status and turgor-driven growth. With the introduction of irrigation, the Lp-norm values showed a steady increase, revealing that even a moderate addition of soil water significantly enhanced plant performance. At an irrigation level of 20 mm per cycle, Lp-norm values increased to roughly 0.65–0.68, suggesting that partial alleviation of soil moisture deficit was adequate to promote ongoing branch extension. The peak irrigation level (30 mm) led to Lp-norm values ranging from 0.80–0.83, placing these plants within the highest performance quartile and confirming that fully compensating for the evaporative losses in the root zone optimizes vegetative growth in apricot liners.

The classification of quartiles illustrates the varying levels of water availability based on treatment conditions and their effect on growth: the 30 mm water regime proved to be the most favorable moisture condition, while 20 mm indicated acceptable yet moderately deficit-sensitive circumstances, 10 mm represented partial deficit irrigation, and 0 mm demonstrated extreme water scarcity. This progression closely aligns with recognized principles in irrigation science, which indicate that gradual enhancements in soil moisture availability directly led to noticeable increases in biomass growth and shoot development in young woody plants. The Lp-norm index, by accounting for growth responses throughout the entire season, highlights the cumulative effect of water availability—showing that the depth of irrigation not only affects immediate plant water relations but also shapes long-term growth potential.

Significant differences specific to genotype were also noted. Throughout the irrigation gradient, ‘Favorit’ consistently exhibited higher Lp-norm values when facing limited water availability, reflecting its superior physiological resilience to low soil moisture and better ability to sustain shoot growth under deficit irrigation. This cultivar seems to manage water usage more conservatively, allowing for consistent growth even during times of reduced soil moisture—a characteristic highly relevant for effective water management strategies in nurseries. Conversely, ‘Excelsior’ displayed a more pronounced increase in Lp-norm values between the 10 mm and 20 mm treatments, indicating a greater sensitivity to enhancements in water availability and a stronger reliance on sufficient irrigation inputs. These differing responses underscore the necessity of incorporating genotype-specific physiological traits into nursery irrigation planning, especially in areas confronting rising climatic variability and water shortages.

The Lp-norm analysis indicates that the depth of irrigation has a significant and cumulative effect on plant growth, with increased water availability consistently promoting branch initiation and shoot elongation during the growing season. This trend confirms that water supply influences not only immediate physiological processes but also long-term canopy development by controlling ongoing cell expansion and maintaining turgor pressure in emerging shoots. Additionally, the differing reactions observed between the two cultivars reveal that sensitivity to water is fundamentally dependent on the genotype. The ‘Excelsior’ cultivar showed a strong dependency on sufficient soil moisture to achieve its growth potential, while ‘Favorit’ exhibited more stable growth with lower water input, indicating a higher intrinsic drought resistance. These cultivar-specific variations highlight the importance of incorporating genotype-based water needs into nursery irrigation plans. By factoring in these physiological differences when scheduling irrigation, it is possible to enhance water-use efficiency, reduce excessive water application, and ensure the production of consistently vigorous planting stock, which is crucial for sustainable nursery operations amid increasingly unpredictable climatic conditions.

4. Discussion

The current research offers fresh perspectives on how the depth of irrigation affects soil water balance and the growth of apricot liner plants in nursery settings. The findings indicate that irrigation is crucial for sustaining sufficient soil moisture during times of high evapotranspiration, especially in July and August when temperatures and atmospheric demands surpass natural rainfall. Comparable trends have been observed in fruit-tree nurseries, where extended periods of moisture shortage hinder shoot growth and affect canopy development [

36,

37]. However, this investigation illustrates the extent of the decline in soil moisture under rainfed conditions, underscoring the susceptibility of nursery-cultivated apricot plants to water shortages and emphasizing the necessity for controlled irrigation in temperate continental climates with irregular rainfall patterns. A significant aspect of this research is the analysis of how different cultivars respond to various irrigation levels. While earlier studies have addressed the impact of water stress on the physiology and growth of apricot trees [

38,

39], not many have assessed the reactions of young liner plants from different genotypes to regulated irrigation in field nursery environments. The current results indicate that the cultivar ‘Favorit’ exhibited notably better vegetative growth under limited irrigation, suggesting a more cautious approach to water usage, while ‘Excelsior’ showed a stronger reaction to progressive increases in soil moisture. Comparable differences in water-use efficiency and drought resistance influenced by genotype have been noted in other

Prunus species, highlighting the need to incorporate cultivar characteristics into irrigation strategies [

40,

41].

An innovative element of the research is the use of the Lp-norm index (where p = 2.5) to measure overall vegetative performance. Conventional nursery evaluations typically depend on individual morphological characteristics like plant height or shoot length. Nonetheless, comprehensive indices offer a more precise reflection of growth responses under different environmental conditions [

42]. By normalizing variations in shoot length across treatments, the Lp-norm facilitated better differentiation among irrigation levels and cultivars, uncovering subtle growth gradients that traditional metrics might miss. To our knowledge, the use of Lp-norm analysis in studies concerning nursery irrigation is infrequent, making this method a significant advancement in assessing cumulative vegetative performance.

The results have significant implications for scheduling irrigation in nurseries and improving water-use efficiency. Treatments that restored 50–100% of the soil moisture deficit kept soil moisture levels above critical limits for most of the season, whereas conditions relying on rainfall led to ongoing moisture shortages. The notable increase in growth from 0 mm to 20 mm of irrigation suggests that moderate water replenishment encourages satisfactory plant health, while the 30 mm treatment maximized the development of the canopy. This aligns with the concepts of precision and deficit irrigation, where carefully managed water usage fosters growth while reducing the risk of excessive or poorly timed applications [

43,

44]. Such approaches are becoming increasingly vital in horticultural systems facing challenges like water scarcity, heightened evaporation rates, and climate instability [

45].

The genotype-specific reactions identified in this research emphasize the shortcomings of applying uniform irrigation practices. The ‘Favorit’ cultivar showed enhanced resilience to drought, while the ‘Excelsior’ cultivar displayed increased vulnerability to moderate levels of water. Comparable results in other nursery plants suggest that tailoring irrigation strategies to individual cultivars can enhance both water-use efficiency and plant health at the same time [

46]. Incorporating genotype characteristics into irrigation planning is particularly crucial in areas experiencing variable water availability and growing climate-related challenges.

To summarize, this research provides significant insights into water management science by connecting soil moisture variations, irrigation levels, and genotype-specific reactions in apricot nursery plants. The application of the Lp-norm index as a comprehensive tool is a novel method for measuring total vegetative growth. The findings highlight the importance of precision irrigation practices that consider the water needs of different varieties, promoting sustainable nursery operations and enhancing the adaptability of planting materials in a transforming climate.

5. Conclusions

This research illustrates that the depth of irrigation has a significant impact on the dynamics of soil moisture and the growth of apricot liner plants cultivated in nursery field settings. During times of high evaporative demand, soil moisture was rapidly depleted under rainfed conditions, while even moderate irrigation levels helped to stabilize the soil water balance and promoted ongoing shoot elongation. Among the two cultivars studied, ‘Favorit’ demonstrated a more conservative approach to water usage and achieved better vegetative performance under limited irrigation, while ‘Excelsior’ showed a greater responsiveness to increased irrigation depth, suggesting a higher reliance on sufficient soil moisture. A significant innovation of this study is the combination of soil moisture modeling, growth analysis specific to genotype, and the implementation of the Lp-norm index as a novel method for measuring cumulative growth performance. This strategy facilitated a more detailed evaluation of vegetative responses to irrigation compared to traditional single-parameter metrics. To our knowledge, this represents one of the first uses of the Lp-norm technique in nursery irrigation research, highlighting its effectiveness in encapsulating multi-dimensional growth responses in field settings.

The results emphasize the critical role of precise irrigation in nursery production, indicating that partially replenishing soil water deficits (20 mm) can support satisfactory growth, whereas complete replenishment (30 mm) optimizes branch growth. These findings carry significant implications for enhancing water-use efficiency, especially in areas where variations in climate and seasonal water shortages impact nursery practices. The observed differences in genotype-specific responses further highlight the necessity of customizing irrigation schedules based on cultivar characteristics instead of employing uniform watering methods.

This research adds valuable information to the field of water management by elucidating how both irrigation depth and genetic differences influence the initial development of apricot canopies. These findings aid in creating more sustainable nursery methods that improve plant quality, maximize freshwater efficiency, and bolster the long-term stability of fruit orchard establishment.