Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

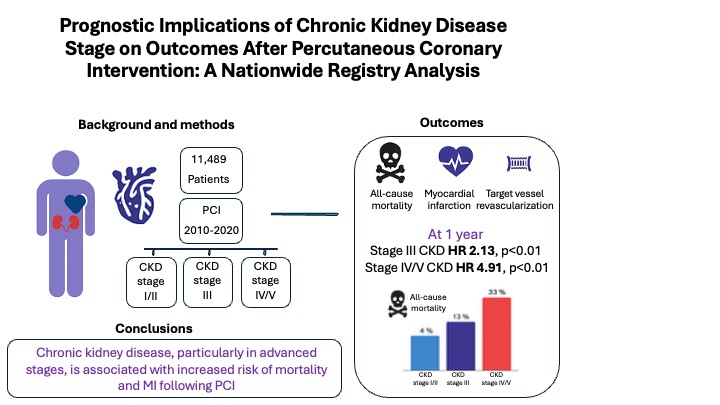

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Follow-Up and Outcomes

2.3. Data Collection and Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Strata

3.2. Follow-Up and Outcomes

3.3. Multivariable and Competing Risk Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest

References

- Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, Jafar TH, Heerspink HJL, Mann JF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. The Lancet [Internet]. 2013 Jul [cited 2025 Jul 16];382(9889):339–52. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673613605954.

- Saeed D, Reza T, Shahzad MW, Karim Mandokhail A, Bakht D, Qizilbash FH, et al. Navigating the Crossroads: Understanding the Link Between Chronic Kidney Disease and Cardiovascular Health. Cureus. 2023 Dec;15(12):e51362.

- Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, Bilo HJ, Chalmers J, Heerspink HJL, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: a meta-analysis. The Lancet [Internet]. 2012 Nov [cited 2025 Jul 16];380(9854):1662–73. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673612613506.

- Na KY, Kim CW, Song YR, Chin HJ, Chae DW. The Association between Kidney Function, Coronary Artery Disease, and Clinical Outcome in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. J Korean Med Sci [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2025 Jul 16];24(Suppl 1):S87. Available from: https://jkms.org/DOIx.php?id=10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S87.

- Lee JM, Kang J, Lee E, Hwang D, Rhee TM, Park J, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease in the Second-Generation Drug-Eluting Stent Era. JACC Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2016 Oct [cited 2025 Jul 16];9(20):2097–109. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1936879816310895.

- Kwon W, Choi KH, Song YB, Park YH, Lee JM, Lee JY, et al. Intravascular Imaging in Patients With Complex Coronary Lesions and Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2023 Nov 29 [cited 2025 Jul 16];6(11):e2345554. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2812357.

- Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int [Internet]. 2005 Jun [cited 2025 Jul 16];67(6):2089–100. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0085253815506984.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009 May 5;150(9):604–12.

- Mitchell C, Rahko PS, Blauwet LA, Canaday B, Finstuen JA, Foster MC, et al. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr [Internet]. 2019 Jan [cited 2025 Jul 16];32(1):1–64. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0894731718303183.

- Vichova T, Knot J, Ulman J, Maly M, Motovska Z. The impact of stage of chronic kidney disease on the outcomes of diabetics with acute myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Int Urol Nephrol [Internet]. 2016 Jul [cited 2025 Jul 23];48(7):1137–43. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11255-016-1260-9.

- Grandjean-Thomsen NL, Marley P, Shadbolt B, Farshid A. Impact of Mild-to-Moderate Chronic Kidney Disease on One Year Outcomes after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Nephron [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2025 Jul 23];137(1):23–8. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto Y, Ozaki Y, Kan S, Nakao K, Kimura K, Ako J, et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on In-Hospital and 3-Year Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated by Contemporary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Optimal Medical Therapy ― Insights From the J-MINUET Study ―. Circ J [Internet]. 2021 Sep 24 [cited 2025 Jul 23];85(10):1710–8. Available from: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/circj/85/10/85_CJ-20-1115/_article.

- Soh RYH, Sia CH, Lau RH, Ho PY, Timothy NYM, Ho JSY, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease on long-term outcomes following semi-urgent and elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis [Internet]. 2021 Sep [cited 2025 Jul 23];32(6):517–25. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000980.

- Jiang W, Zhou Y, Chen S, Liu S. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tex Heart Inst J [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 23];50(1). Available from: https://thij.kglmeridian.com/view/journals/thij/50/1/article-e227873.xml.

- Ronco C, Bellasi A, Di Lullo L. Cardiorenal Syndrome: An Overview. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis [Internet]. 2018 Sep [cited 2025 Jul 16];25(5):382–90. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1548559518301204.

- Kumar U, Wettersten N, Garimella PS. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Pathophysiology. Cardiol Clin. 2019 Aug;37(3):251–65.

- Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, Blair JEA, Chang TI, Costa S, Lentine KL, et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Classification, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2019 Apr 16 [cited 2025 Jul 16];139(16). [CrossRef]

- Vasu S, Gruberg L, Brown DL. The impact of advanced chronic kidney disease on in-hospital mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2007 Nov 1;70(5):701–5.

- Skalsky K, Shiyovich A, Steinmetz T, Kornowski R. Chronic Renal Failure and Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Appraisal. J Clin Med [Internet]. 2022 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Jul 16];11(5):1335. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/5/1335.

- Milojevic M, Head SJ, Mack MJ, Mohr FW, Morice MC, Dawkins KD, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with complex coronary artery disease: five-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. EuroIntervention [Internet]. 2018 May [cited 2025 Jul 17];14(1):102–11. Available from: http://www.pcronline.com/eurointervention/134th_issue/15.

- Milojevic M, Head SJ, Mack MJ, Mohr FW, Morice MC, Dawkins KD, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with complex coronary artery disease: five-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. EuroIntervention [Internet]. 2018 May [cited 2025 Jul 24];14(1):102–11. Available from: http://www.pcronline.com/eurointervention/134th_issue/15.

- Saltzman AJ, Stone GW, Claessen BE, Narula A, Leon-Reyes S, Weisz G, et al. Long-Term Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated With Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2025 Jul 24];4(9):1011–9. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1936879811005450.

- Chaitman BR, Cyr DD, Alexander KP, Pracoń R, Bainey KR, Mathew A, et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Implications of Myocardial Infarction in the ISCHEMIA-CKD Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv [Internet]. 2022 Aug [cited 2025 Jul 17];15(8). [CrossRef]

- Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O’Brien SM, Fleg JL, Kretov EI, Briguori C, et al. Management of Coronary Disease in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 23 [cited 2025 Jul 17];382(17):1608–18. [CrossRef]

- Szummer K, Lundman P, Jacobson SH, Schön S, Lindbäck J, Stenestrand U, et al. Influence of Renal Function on the Effects of Early Revascularization in Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Data From the Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART). Circulation [Internet]. 2009 Sep 8 [cited 2025 Jul 17];120(10):851–8. [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Guo Y, Mauricio R, Bangalore S. Management and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol [Internet]. 2017 Jan [cited 2025 Jul 17];227:1–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167527316334726.

- Gaut JP. Time to Abandon Renalism: Patients with Kidney Diseases Deserve More. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol [Internet]. 2023 Apr [cited 2025 Jul 24];18(4):419–20. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.2215/CJN.0000000000000127.

| Stage I/II (n=8781) | Stage III (n=2063) | Stage IV/V (n=645) | P | |

| Demographics | ||||

| age (years) | 63.4 (11.6) | 75 (10.1) | 72.5 (12.9) | 0.000 |

| Female gender (%) | 20.1 | 33.7 | 33 | 0.000 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| DM (%) | 40.8 | 54.9 | 70.7 | 0.000 |

| HTN (%) | 67.2 | 87.6 | 94.4 | 0.000 |

| Smoking History (%) | 38.6 | 22 | 19.2 | 0.000 |

| COPD (%) | 7.6 | 11.8 | 14 | 0.000 |

| PVD (%) | 4.1 | 7.4 | 15.5 | 0.000 |

| Prior Stroke (%) | 5.6 | 10.4 | 14.6 | 0.000 |

| Cardiac diseases | ||||

| Known CHF (%) | 7.7 | 14.9 | 11.6 | 0.000 |

| EF (%) | 54.9 (8.9) | 52.7 (10.3) | 49.9 (11.5) | 0.000 |

| Known Atrial Fibrillation (%) | 4.4 | 7.6 | 8.2 | 0.000 |

| S/P CABG (%) | 9.1 | 15.7 | 18.8 | 0.000 |

| Other diseases | ||||

| Prior Malignancy (%) | 9.7 | 18.2 | 22.2 | 0.000 |

| Active Malignancy (%) | 4 | 5.5 | 2.9 | 0.002 |

| Dementia (%) | 1.5 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 0.000 |

| Blood tests results | ||||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 170.8 (44.7) | 156.9 (44.2) | 147.8 (44.3) | 0.000 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 41.5 (12.4) | 42.8 (13.9) | 39.3 (12.8) | 0.000 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 99.7 (37.8) | 85.7 (36.5) | 78.2 (35.7) | 0.000 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 153.7 (106.6) | 143.1 (85.2) | 157.6 (96.2) | 0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.8 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.8) | 7.2 (1.9) | 0.000 |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 13.7 (1.7) | 12.4 (2) | 10.7 (1.7) | 0.000 |

| MPV (fL) | 8.9 (1.2) | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.2 (1.3) | 0.000 |

| Plt (10^3/µL) | 232.2 (73.7) | 227.5 (86.1) | 221.8 (84.9) | 0.000 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.3) | 4.3 (2.6) | 0.000 |

| Uric Acid (mg/dL) | 5.8 (1.5) | 7.2 (1.9) | 7.7 (2.7) | 0.000 |

| WBC (10^3/µL) | 8.7 (4.7) | 9.2 (9.4) | 8.6 (4.1) | 0.002 |

| Coronary intervention | ||||

| Acute MI (%) | 44.8 | 42.7 | 38 | 0.002 |

| STEMI (%) | 21.4 | 16.5 | 12.9 | 0.000 |

| ACS (excluding MI) (%) | 24 | 21.7 | 18.3 | 0.001 |

| CX_treated (%) | 30.6 | 30.8 | 34.1 | 0.183 |

| LAD_treated (%) | 48.3 | 46.2 | 42.8 | 0.009 |

| RCA_treated (%) | 32.4 | 28.1 | 29.1 | 0.000 |

| LM_treated (%) | 5.3 | 10.5 | 12.6 | 0.000 |

| Graft treated (%) | 2.1 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 0.000 |

| Multivessel PCI (%) | 10.3 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 0.308 |

| CTO treated (%) | 13.6 | 11.9 | 10.4 | 0.012 |

| DES (%) | 76.9 | 72.5 | 73 | 0.000 |

| DEB (%) | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 0.494 |

| Radial approach (%) | 64.4 | 51.2 | 40.9 | 0.000 |

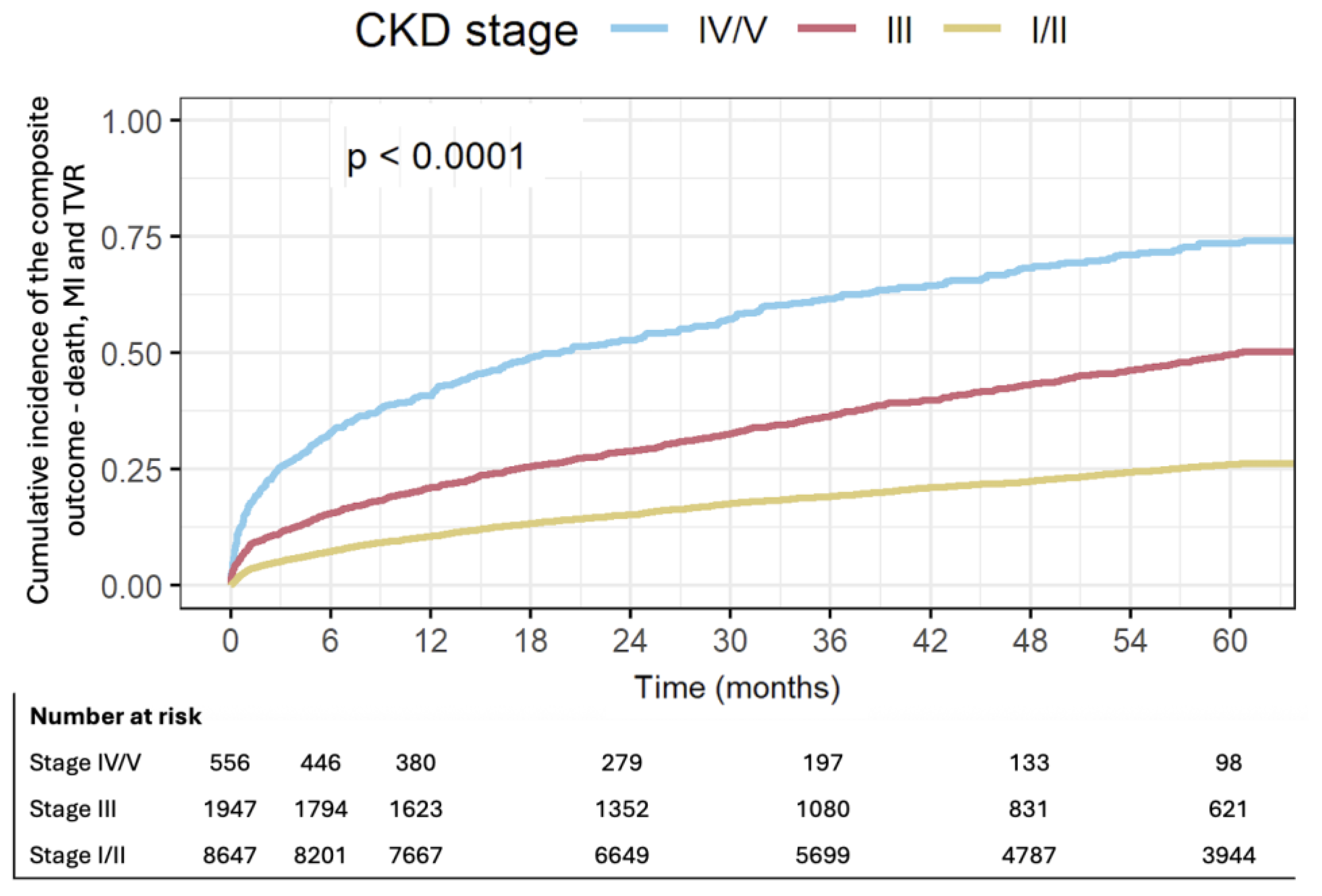

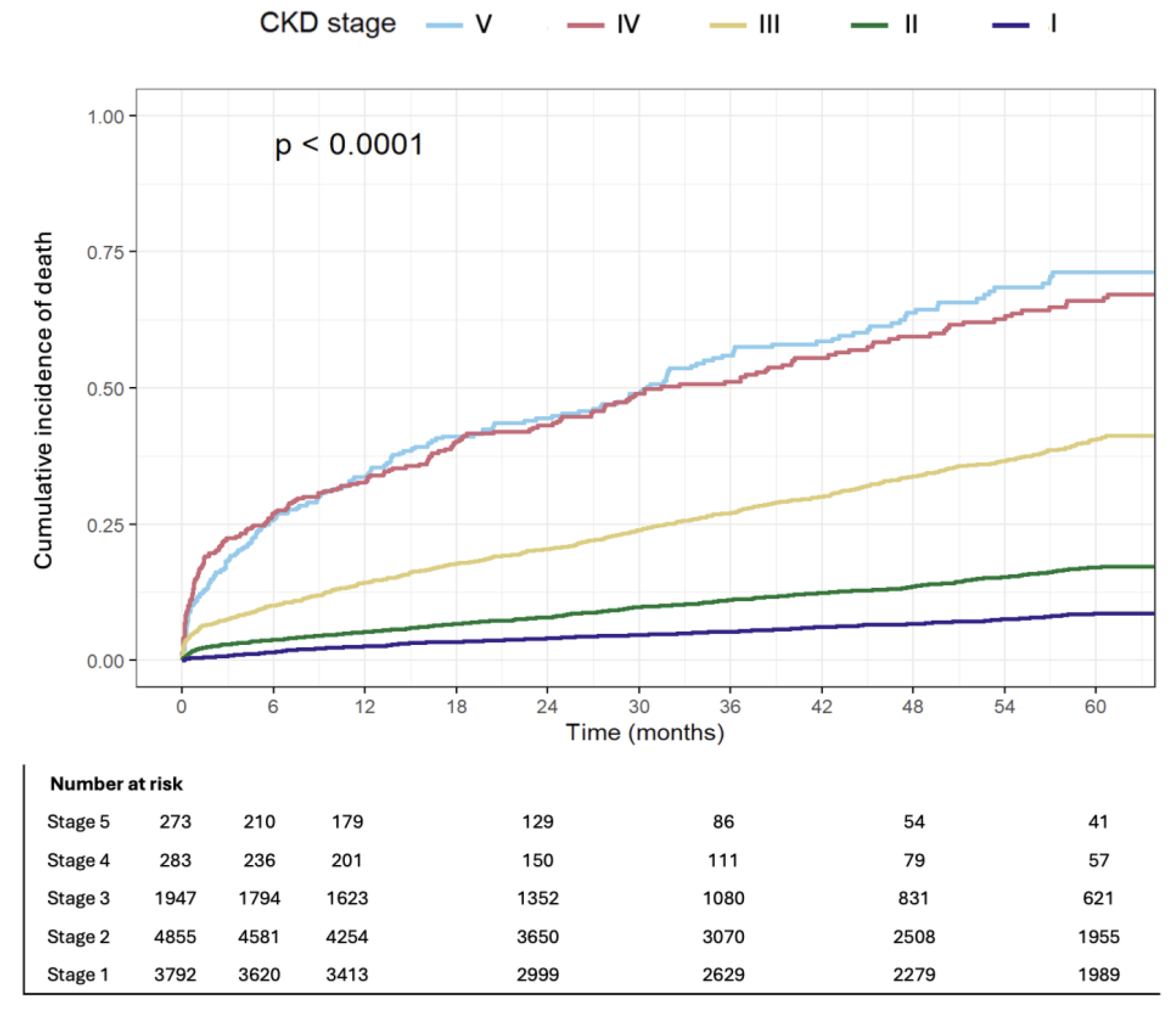

| Outcomes | Preserved kidney function (n=8781), % | Stage III (n=2063), % | Stage IV/V (n=645), % | p |

| Mon-fatal MI, TVR and all-cause mortality at 1y | 10.3 | 20.6 | 40.8 | 0.000 |

| All-cause mortality at 1y | 4 | 14.1 | 33 | 0.000 |

| MI at 1y | 5.8 | 7.1 | 10.5 | 0.000 |

| TVR at 1y | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 0.387 |

| non-fatal MI and all-cause mortality at 1y | 9.4 | 20.1 | 40.2 | 0.000 |

| All-cause mortality at 5y | 10.5 | 33.3 | 57.2 | 0.000 |

| MI at 5y | 11.1 | 12.6 | 15.2 | 0.002 |

| TVR at 5y | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 0.901 |

| Mon-fatal MI and all-cause mortality at 5y | 20.1 | 40.8 | 63.3 | 0.000 |

| Variable | 1-year HR (95% CI) | p-value | 5-year HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| CKD Stage | ||||

| IV/V | 3.00 (2.58–3.49) | <0.001 | 2.78 (2.48–3.13) | <0.001 |

| III | 1.46 (1.29–1.65) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.37–1.63) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted Variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.018 (1.014–1.022) | <0.001 | 1.020 (1.017–1.022) | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | 0.015 | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.107 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.14 (1.03–1.27) | 0.010 | 1.27 (1.18–1.37) | <0.001 |

| MI or ACS (non-elective PCI) | 1.43 (1.29–1.60) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction | 1.76 (1.57–1.96) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.52–1.78) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.92 (0.76–1.13) | 0.432 | 1.08 (0.95–1.23) | 0.218 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.33 (1.09–1.63) | 0.005 | 1.56 (1.35–1.79) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1.28 (1.10–1.48) | 0.001 | 1.36 (1.23–1.51) | <0.001 |

| Radial approach | 0.64 (0.58–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.71–0.82) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 0.012 | 1.25 (1.12–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.13 (0.98–1.31) | 0.101 | 1.32 (1.20–1.46) | <0.001 |

| Variable | 1-year HR (95% CI) | p-value | 5-year HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| CKD Stage | ||||

| IV/V | 4.73 (3.90–5.73) | <0.001 | 4.13 (3.60–4.73) | <0.001 |

| III | 2.18 (1.85–2.58) | <0.001 | 2.15 (1.93–2.38) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted Variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Female gender | 1.29 (1.11–1.49) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.01 (0.88–1.16) | 0.913 | 1.20 (1.10–1.32) | <0.001 |

| MI or ACS (non-elective PCI) | 1.17 (1.01–1.35) | 0.032 | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | 0.536 |

| Moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction | 2.46 (2.13–2.84) | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.90–2.30) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.58 (0.42–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | 0.422 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.49 (1.17–1.90) | 0.001 | 1.78 (1.52–2.09) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1.57 (1.31–1.88) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.45–1.85) | <0.001 |

| Radial approach | 0.50 (0.44–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.62–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke | 1.17 (0.95–1.44) | 0.145 | 1.29 (1.13–1.48) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.65 (0.51–0.83) | <0.001 | 1.06 (0.94–1.21) | 0.355 |

| Variable | MI at 1 year HR (95% CI) | p-value | MI at 5 years HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| CKD Stage | ||||

| IV/V | 1.83 (1.40–2.39) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.35–2.09) | <0.001 |

| III | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 0.578 | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 0.292 |

| Adjusted Variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.147 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.894 |

| Female gender | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 0.828 | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) | 0.407 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.31 (1.13–1.53) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.27–1.59) | <0.001 |

| MI or ACS (non-elective PCI) | 2.02 (1.69–2.42) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.46–1.87) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction | 1.09 (0.91–1.32) | 0.350 | 1.13 (0.99–1.30) | 0.076 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.42 (1.11–1.83) | 0.006 | 1.48 (1.23–1.77) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.07 (0.75–1.52) | 0.722 | 1.26 (0.98–1.63) | 0.072 |

| COPD | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 0.687 | 1.00 (0.83–1.21) | 0.979 |

| Radial approach | 0.77 (0.66–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke | 1.35 (1.07–1.72) | 0.013 | 1.25 (1.04–1.50) | 0.019 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.00 (1.65–2.42) | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.77–2.35) | <0.001 |

| Variable | 1-yearHR (95% CI) | p-value | 5-yearHR (95% CI) | p-value |

| CKD Stage | ||||

| IV/V | 1.16 (0.73–1.85) | 0.530 | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 0.714 |

| III | 0.74 (0.53–1.04) | 0.084 | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | 0.774 |

| Adjusted Variables | ||||

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.077 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.894 |

| Female gender | 0.85 (0.64–1.13) | 0.267 | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 0.069 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.88 (1.47–2.41) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.48–2.11) | <0.001 |

| MI or ACS (non-elective PCI) | 1.49 (1.15–1.95) | 0.003 | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) | 0.073 |

| Moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction | 1.22 (0.92–1.63) | 0.169 | 1.06 (0.85–1.33) | 0.589 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.14 (0.75–1.75) | 0.534 | 1.40 (1.05–1.88) | 0.022 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | 0.464 | 1.12 (0.74–1.69) | 0.598 |

| COPD | 0.95 (0.64–1.43) | 0.823 | 0.96 (0.71–1.30) | 0.787 |

| Radial approach | 0.81 (0.63–1.02) | 0.077 | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 0.382 |

| Prior stroke | 1.58 (1.10–2.26) | 0.012 | 1.44 (1.09–1.90) | 0.010 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.16 (1.60–2.91) | <0.001 | 1.96 (1.56–2.45) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).