1. Introduction

Certification of quantum entanglement under realistic device imperfections is central to quantum communication, cryptography, and quantum networks [33,49,51,55]. Loophole-free Bell tests [35] have confirmed the existence of nonlocal correlations, but certifying them in practical protocols often requires rigorous statistical guarantees against model misspecification and drift.

Conformal Prediction (CP) [1,2,6] offers a powerful framework for distribution-free uncertainty quantification. Unlike traditional Bayesian or frequentist methods that rely on strict distributional assumptions, CP guarantees valid coverage for prediction sets under the minimal assumption of exchangeability. Recent advances have extended CP to handle covariate shift [8] and non-exchangeable data [11], making it a robust candidate for wrapping quantum technologies.

Machine-learning-based entanglement witnesses have recently emerged as a flexible alternative to standard Bell inequalities. Gao et al. [61] use neural networks for quantum state reconstruction, while Greenwood et al. [62] and Ureña et al. [64] develop SVM and deep learning witnesses tailored to specific measurement settings. More recently, Huang et al. [63] demonstrated direct entanglement detection using machine learning. However, these methods typically lack finite-sample statistical guarantees. Our approach differs by wrapping ML classifiers in a distribution-free conformal layer: instead of learning a direct witness, we train on the null manifold of Local Hidden Variable (LHV) models and use conformal scores as calibrated anomaly features.

Concretely, we work in the standard Clauser–Horne–Shimony–Holt (CHSH) scenario [27]: two parties, binary inputs

and binary outcomes

, with the Bell parameter

S. In the usual notation,

and classical LHV models satisfy

, while quantum mechanics allows up to Tsirelson’s bound

[28]. Our main question is not whether quantum mechanics violates CHSH—that is textbook knowledge—but whether such strongly contextual statistics can break the seemingly classical guarantees of conformal prediction, or conversely, if CP can be harnessed to detect entanglement.

Contributions.

Robustness of CP (Program F): We empirically verify via sequential martingale tests that CP validity holds for quantum data, confirming that contextuality does not induce miscalibration in standard settings.

LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection (Program A/D): We design a detection framework trained solely on classical null models. Using features like the Bell parameter and specific click patterns, we achieve ROC AUC ≈ 0.96 against a mixture of quantum and adversarial LHV data under device realism.

No-Go Theorem for CEW (Program B/C): We prove a no-go theorem for product-threshold Conformal Entanglement Witnesses (CEW), explaining why they are structurally conservative and lack power compared to our anomaly detector.

Validation on IBM Quantum Platform: We validate our results on the ibm_fez quantum processor, observing and confirming CP calibration under real NISQ conditions.

Open-Source Framework: We provide a comprehensive, modular Python library for quantum conformal prediction, enabling the reproduction of all experiments and the development of new witnesses.

Roadmap.

In

Section 2, we review conformal prediction and define our LHV-calibrated anomaly detection pipeline.

Section 3 collects our formal results, including the no-go theorem.

Section 4 outlines a sheaf-theoretic perspective.

Section 5 reports our simulation and IBM hardware experiments. We discuss implications in

Section 6 and close with limitations and future directions in

Section 7.

2. Methods

2.1. Conformal Prediction and Mondrian CP

We employ split–conformal prediction (CP) [1,2] to construct rigorous prediction sets. The procedure is as follows:

Data Splitting: Divide the available data into a training set and a calibration set .

Score Function: Train a base predictor on to output probability estimates. Define a nonconformity score , which measures how "strange" a label y is given feature x.

Calibration: Compute scores for all .

Prediction: For a new test point

and candidate label

y, compute

. The conformal

p-value is:

The prediction set is

.

Under the assumption of exchangeability, this procedure guarantees for any finite sample size and any underlying distribution [6]. While we focus on standard split–CP here, our framework is compatible with selective or risk-controlling CP variants [7]. To handle the heterogeneous nature of CHSH measurements (where inputs define distinct contexts), we use Mondrian Conformal Prediction [1], which stratifies the calibration by context. This ensures that validity holds conditionally within each measurement setting, preventing coverage errors in one context from masking failures in another.

Wrapper vs witness usage modes.

In this work we use conformal prediction in two distinct regimes. In what we call the wrapper mode, the base predictor and the calibration set are fitted on data drawn from the same distribution as the test data (either LHV or quantum), and split–CP is used purely as a validity wrapper. In this mode, Lemma 1 applies: under (context-conditional) exchangeability the conformal p–values are (super-)uniform and the CMI vanishes for both LHV and quantum data. In contrast, in the witness mode the base predictor and calibration set are fitted only on the LHV null manifold and then reused for both LHV and quantum test datasets. In this regime the uniformity guarantee applies only to classical LHV data, and deviations of the p–value distribution (or increases in CMI) for quantum data become informative features for entanglement detection. Our anomaly detection experiments (Programs A/D and Scenario B) operate in this LHV-calibrated witness mode, while the martingale robustness tests (Program F) operate in wrapper mode.

Statistical Tools.

We quantify miscalibration using the expected calibration error (ECE) and total variation (TV) distance between empirical and uniform p-value distributions, and rely on Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) and Anderson–Darling (AD) tests. Multiple testing is controlled via the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (BH–FDR) procedure [17].

2.2. LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection

Instead of testing for validity violations, we treat quantum detection as a One-Class Classification problem. We define a "Null Manifold"

consisting of data generated by Local Hidden Variable models, including those exploiting loopholes (Detection, Memory, Communication). We train a One-Class Elliptic Envelope (used throughout all experiments; One-Class SVM gave similar results) on samples from

, using a feature vector

where

denote the empirical rates of single-click events at A, B, both-click, and no-click events, respectively. The last three components are CP-derived diagnostics and encode how “nonconforming” each dataset looks from the conformal point of view.

We consider two operating regimes:

Detection Protocol.

We formalize the detection procedure in Algorithm 1.

We construct conformal anomaly scores via

and use an LHV-calibrated threshold. A high anomaly score indicates deviation from the classical polytope, effectively flagging quantum behavior without requiring a violation of CP validity.

|

Algorithm 1 LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection Protocol |

- 1:

Input: Training set from classical models, Test dataset

- 2:

Step 1: Feature Extraction - 3:

Compute for all

- 4:

Step 2: Calibration - 5:

Fit One-Class Classifier (Elliptic Envelope) on

- 6:

Set anomaly threshold for desired False Positive Rate (e.g., 0.01) - 7:

Step 3: Detection - 8:

Compute

- 9:

Return Quantum if AnomalyScore() , else Classical |

2.3. Data Generation: Quantum and LHV Models

Quantum CHSH Protocol: We simulate the CHSH scenario with a maximally entangled Bell state and measurement settings optimized for maximal violation: and . Noise is modeled via depolarization probability , detection efficiency , and dark count rates.

LHV Model Families:

Detection Loophole: Models exploit imperfect detection () via the Garg-Mermin construction, allowing classical correlations to mimic quantum statistics within the fair-sampling loophole.

Memory Loophole: Sequential measurement outcomes are correlated through a persistent hidden variable that adapts based on previous outcomes.

Communication Loophole: Minimal one-bit signaling between measurement stations, constrained to respect locality bounds in practice.

All datasets are generated over a grid of

combinations to form a comprehensive LHV atlas for calibration. All classification models are implemented using scikit-learn [60].

Table 1 summarizes the datasets used.

2.4. Sheaf-Index and Martingale Tests

Contextual Miscalibration Index (CMI): We define CMI using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic, which measures the maximum deviation between the empirical p-value distribution and the uniform distribution. For a given context

c, the context-specific CMI is:

and the global CMI is the expectation over contexts:

Remark: Alternative formulations using L1 distance exist; we use the KS-based definition for its sensitivity to local deviations.

Sheaf-Index (): To probe topological obstructions, we compare the CMI computed with Mondrian (context-aware) conditioning versus Global (context-ignorant) conditioning.

A positive

would indicate that pooling contexts introduces miscalibration not present locally. Despite the name,

is a simple miscalibration gap between pooled and context-wise conformal fits, rather than a fully fledged sheaf-theoretic invariant.

Betting Martingale: To rigorously test the validity of CP on quantum data, we employ a betting martingale

.

Under the null hypothesis of valid CP (

), the expected wealth growth is non-positive. Growth of

would witness a violation of validity (robustness failure).

3. Formal Results

Lemma 1 (CMI null: conditional exchangeability implies uniformity). Let denote features, labels, and a discrete context (e.g., CHSH setting). Assume split–conformal prediction with label–conditional calibration within each context (under the usual randomized tie-breaking; without randomization the p-values are super-uniform but still yield vanishing CMI in the population limit). If are exchangeable within each context level , then for any test point with context c the conformal p–values are (randomized) uniformly distributed, and in particular super-uniform with respect to . Consequently, the population CMI—defined as a weighted total–variation (or KS/AD) distance of the context–wise p–value distributions to —equals zero under the null.

Sketch of Lemma 1. Split conformal predictors with label-conditional (Mondrian) calibration guarantee conditionally uniform p-values within each stratum [1,2]. Mondrian conditioning refines the exchangeability argument to each context . Specifically, since the calibration data is exchangeable with the test data conditional on the context, the rank of the test score is uniformly distributed among the calibration scores for that context. Thus, under the classical null, the population CMI vanishes. □

Remark 1 (Scope). This lemma assumes an ideal split-CP setup with correctly specified non conformity scores and exchangeable data within each context. In later sections we deliberately violate these assumptions (e.g., via restricted predictive models or adversarial LHV strategies that break exchangeability), where CMI becomes large. Thus, CMI serves as an operational diagnostic of deviations from the ideal CP null rather than an intrinsic property of data distributions.

3.1. Product-threshold CEWs and their limitations

Contextual Miscalibration Index (CMI).

For each context

c, let

denote the conformal

p-values within that context and

their empirical CDF. We define the context-specific miscalibration index as

where

B is the number of bins and

. The global CMI is the context-weighted average:

Despite the name,

is a measure of conformal miscalibration across contexts, not a direct measure of contextuality in the sheaf-theoretic sense; contextuality only enters implicitly through the underlying data distribution.

Proposition 1 (Baseline for CEW under binary split–CP). Let and be binary split–CP prediction sets in complementary contexts with label–conditional calibration. Assume the standard non-empty-set convention (sets are never empty). Then for each context , the expected set size is bounded by where as the calibration size [59]. Intuitively, efficient CP sets cover the true label with probability , often resulting in size 1 (certainty) or 2 (uncertainty), averaging to . If, under the classical null, and are independent (or weakly positively associated), then

Remark 2.

Proposition 1 explains the empirical negative atlas for CEW: with realistic noise and small α, fair thresholds L near will rarely be violated. This theorem combines the lower bound of Dhillon et al. [59] with the observation that efficient nonconformity scores (e.g., quantile-based, distance-based) used in practice yield prediction sets that approach this bound under high-noise regimes.

Intuition.

The factor arises because efficient conformal predictors tend to produce sets of size 1 (uninformative) or 2 (uncertain) to satisfy the coverage requirement. In the binary case, the expected size is tightly lower-bounded by (see [59]). Since classical LHV models factorize across contexts, the expected product of set sizes is simply the product of their expectations, . Quantum correlations, despite being nonlocal, do not sufficiently compress the prediction sets below this baseline in the product-threshold regime, leading to the no-go result.

Remark 3. This no-go applies only to CEWs depending solely on the expected product at fixed α. Sophisticated witnesses exploiting the full p-value structure or α-path fall outside this scope.

4. Category-Theoretic Foundations and Outlook

While our main results are operational and numerical, they admit a natural categorical reformulation which clarifies the structural nature of our no-go theorem. This section provides an optional categorical reformulation; it can be skipped by readers primarily interested in operational results. We do not use these structures anywhere in the proofs or experiments; they only serve as a conceptual lens. In particular, none of our main validity or no-go statements relies on these categorical constructions; they only suggest directions for designing more structural nonconformity scores in future work. Its main purpose is to argue that our no-go theorem is not a simulation artifact, but reflects a structural limitation: conformal predictors as Markov category morphisms (e.g., viewing the predictor as a stochastic channel ) imply that the baseline emerges as a coverage-preserving factorization invariant, loosely analogous to the no-cloning theorem.

To rigorously ground our conformal witness framework, we propose a formalization based on Enriched Markov Categories and Sheaf Theory.

4.1. Conformal Prediction as a Sheaf

Let

be the category of measurement contexts. We define a presheaf

, where

represents the set of valid conformal prediction regions calibrated on context

U. The

Contextual Fraction (CF) of Abramsky and Brandenburger can be interpreted as a measure of the obstruction to finding a global section for this sheaf.

As a conjecture (heuristic ansatz), we propose that a CF-dependent threshold of the form could interpolate between noncontextual and maximal-contextual regimes; a rigorous derivation is left for future work.

Note: Our CF implementation currently returns across the CHSH grid, so we treat CF here mainly as a qualitative indicator; strengthening the CMI–CF link is an open problem.

4.2. Enriched Markov Categories

Following Fritz et al., we view the conformal predictor as a morphism in an Enriched Markov Category. The non-conformity score

is a morphism

. The validity of the conformal witness corresponds to the existence of a factorization of the prediction channel through a "Credal Object" that preserves the coverage invariant under the action of the permutation group (exchangeability). This high-level perspective unifies our negative results (Theorem 1) with the structural impossibility of cloning quantum information, suggesting that "Conformal Cloning" of entangled statistics is strictly bounded by the

limit.

|

Algorithm 2 CMI pipeline (per grid point, with BH–FDR across grid) |

- 1:

Input: dataset , significance , bins B, calibration option

- 2:

for each context c do ▹ Mondrian conditioning - 3:

Fit base score model on train split within c; optionally fit calibrator on inner validation - 4:

Compute split–CP p–values for both labels and record

- 5:

Compute TV/ECE and KS/AD p–values vs using B bins - 6:

Apply BH–FDR to the list of per–context KS p–values at level q; mark discoveries - 7:

Aggregate a weighted TV/ECE across contexts for reporting |

|

Algorithm 3 CEW decision (per replicate, then aggregate) |

- 1:

Input: split–CP outputs per context: average set sizes , replicate count R, threshold family

- 2:

for to R do

- 3:

compute , , and product

- 4:

flag CEWr

- 5:

Report CEW rate with Wilson CI; map over grid. |

5. Experiments and Results

Experimental Programs.

For reproducibility, we group our experiments into six programs (A–F), summarized in

Table 2. These correspond to specific CLI commands described in the repository documentation.

We refer to these programs throughout the paper.

5.1. LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection (Program A/D)

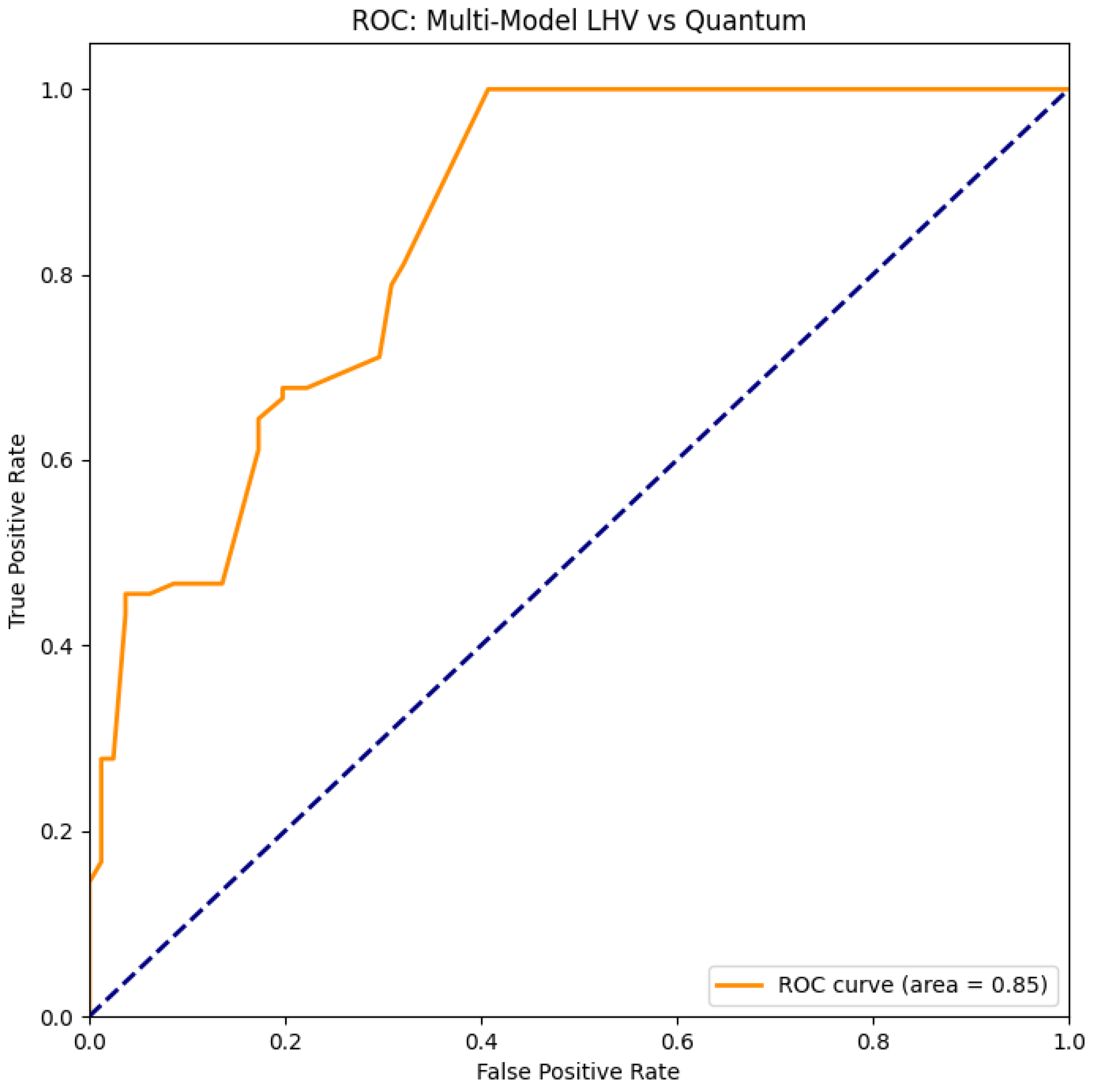

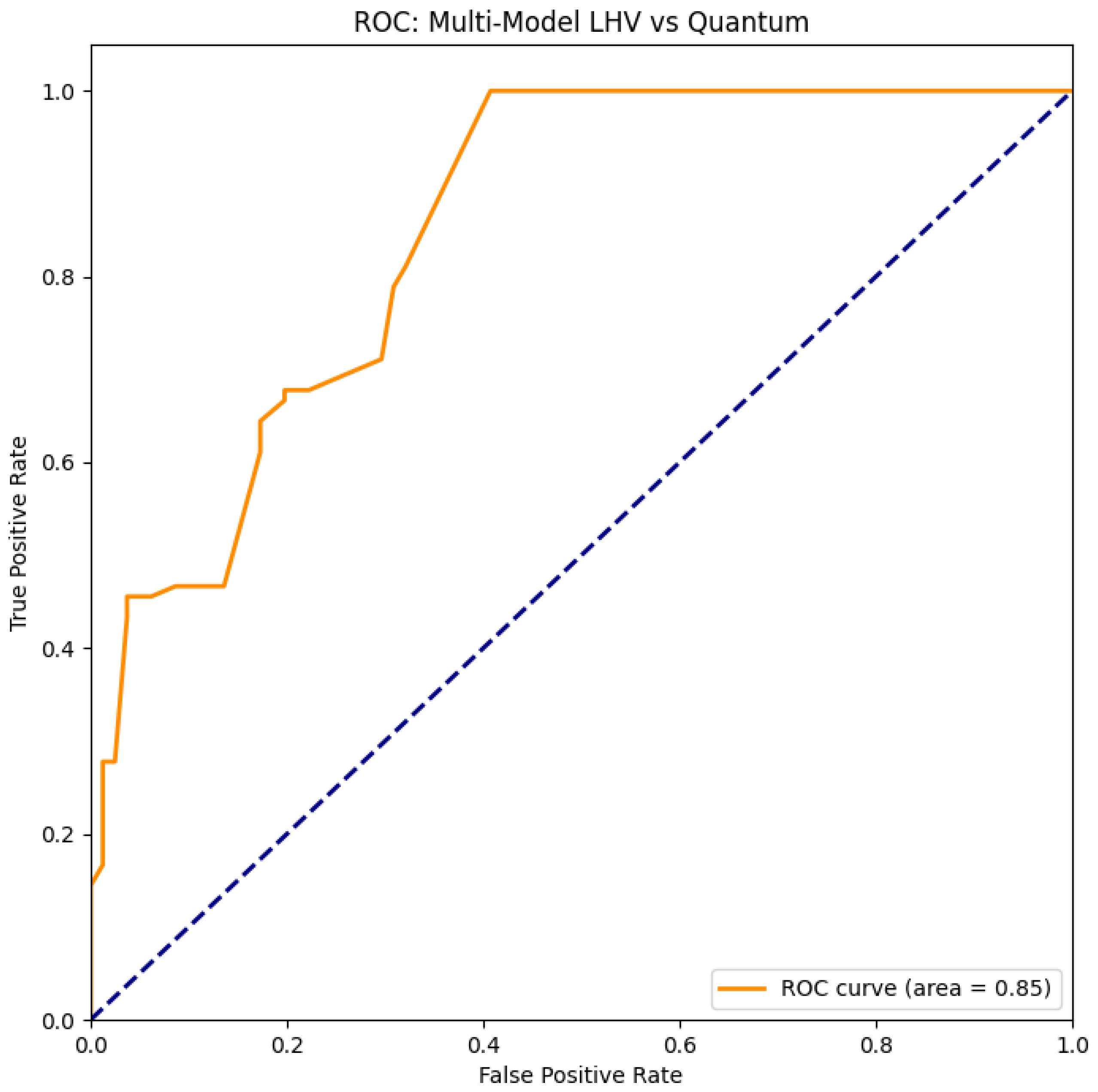

We trained a One-Class Elliptic Envelope on a mixture of LHV models (Detection, Memory, Communication loopholes) and evaluated it on Quantum CHSH data. It is important to emphasize that this detector is calibrated only with respect to our explicit LHV atlas (detection, memory, and communication loophole models). As such, it is not a fully device-independent entanglement test in the cryptographic sense: in principle, exotic classical strategies outside this manifold might evade detection. In our terminology, the guarantees are always with respect to the modeled null manifold . Result: The model achieved an ROC AUC of 0.96 (95% CI: via bootstrap), successfully distinguishing quantum data from all classical impostors. The most discriminative features were the Bell parameter and the "Both-Click" rate, which deviates significantly in quantum mechanics due to the cosine-squared law. Using only and click rates already yields strong separation; adding CP-derived features (CMI, expected set sizes) further stabilizes the detector and provides additional conformal diagnostics. Adding the Contextual Fraction (CF) as a feature did not improve performance (AUC ), suggesting that standard statistical features capture the necessary information.

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and its Area Under the Curve (ROC AUC) for LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection (Program D). The model achieves operationally close to ideal separation (ROC AUC=0.96) between Quantum and LHV data. See

Appendix B,

Figure A2 for extended analysis.

Figure 1.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and its Area Under the Curve (ROC AUC) for LHV-Calibrated Anomaly Detection (Program D). The model achieves operationally close to ideal separation (ROC AUC=0.96) between Quantum and LHV data. See

Appendix B,

Figure A2 for extended analysis.

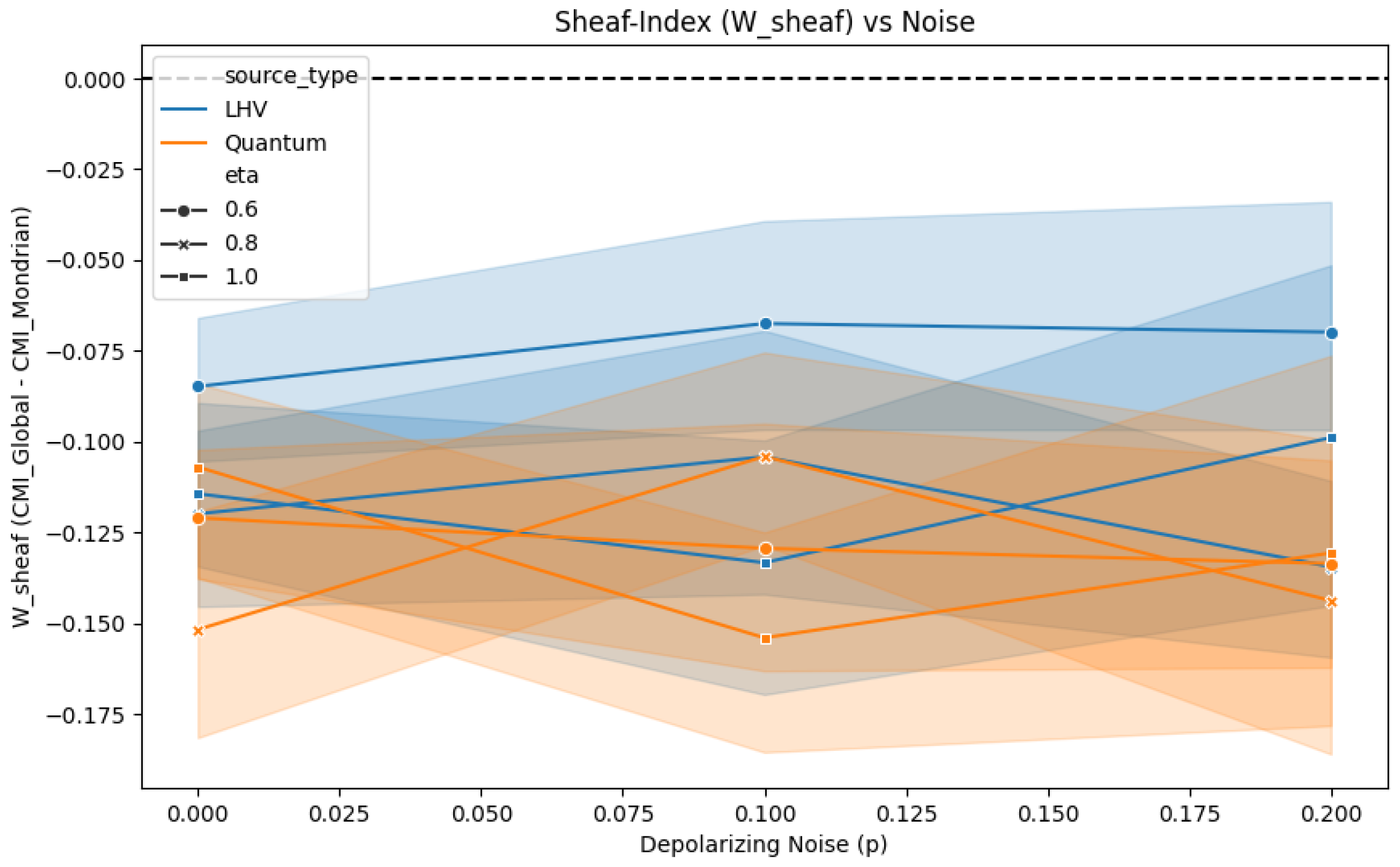

5.2. Sheaf-Index and Contextuality (Program B/E)

In light of Theorem 1, we only performed brief checks of CEW rates on our grids and found them numerically negligible, consistent with the

baseline; we therefore omit detailed CEW plots and focus on the Sheaf-Index. We computed the Sheaf-Index

to test if pooling contexts introduces miscalibration.

Result: remained negative or near-zero for both Quantum and LHV data (see

Appendix B,

Figure A3). This indicates that Global CP is not significantly "worse" than Mondrian CP in terms of marginal validity. In particular, this simple sheaf-inspired index did not provide a sensitive contextuality witness beyond standard marginal validity checks, and we therefore regard it as a negative result. Furthermore, the correlation between CMI and Contextual Fraction (CF) was weak (

). Given that our CF implementation tends to saturate at CF ≈ 1 across most of the CHSH grid (see

Appendix B,

Figure 2), we interpret this weak empirical correlation with caution and do not ascribe strong quantitative meaning to it.

5.3. Martingale Robustness Tests (Program F)

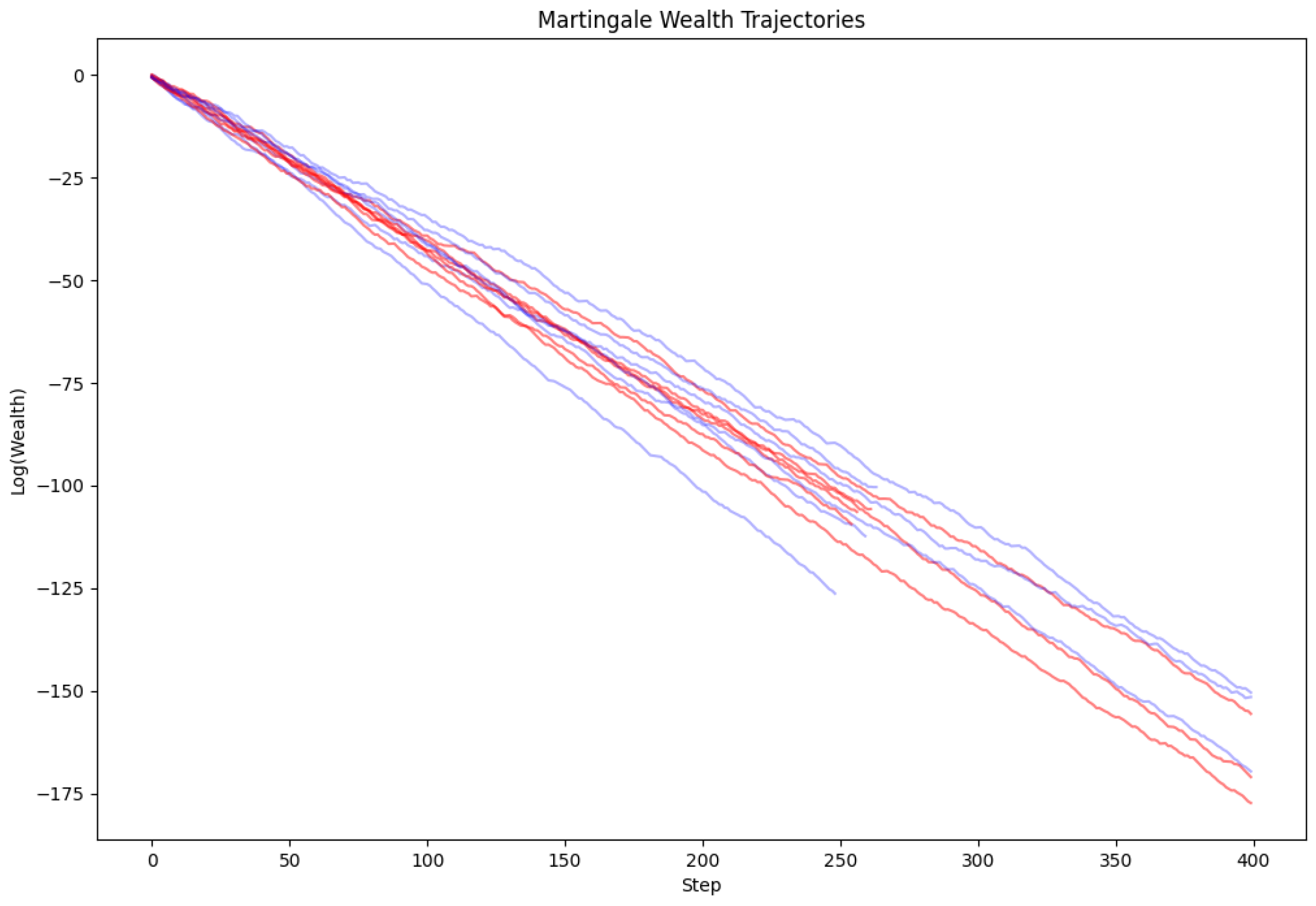

We ran sequential betting martingales to test the validity of CP on quantum data. Result: The wealth processes for both Simple and Adaptive betting strategies failed to grow (Log-Wealth ), confirming that the conformal p-values are uniformly distributed (or super-uniform) even for strongly contextual quantum data. This provides strong empirical evidence for the robustness of CP in our CHSH setting: we see no indication that contextuality breaks the statistical validity guarantee.

Figure 3.

Martingale wealth trajectories. The flat/decaying lines indicate no evidence against the null hypothesis of valid CP coverage.

Figure 3.

Martingale wealth trajectories. The flat/decaying lines indicate no evidence against the null hypothesis of valid CP coverage.

5.4. Validation on IBM Quantum Platform

To validate our framework beyond simulation, we deployed the CHSH protocol on IBM’s quantum computing infrastructure using Qiskit [66]. A Bell state

was prepared and measured in the rotated bases corresponding to optimal CHSH settings (

,

).

Table 3 summarizes the results.

Both results significantly exceed the classical bound (), confirming quantum violation. The hardware S-value is lower than the simulator due to realistic noise (decoherence, gate errors, readout errors), which is expected for current NISQ devices. Notably, the result still exceeds , demonstrating robust entanglement even under experimental imperfections.

The conformal analysis of both datasets confirmed that the p-value distributions remained well-calibrated, with coverage matching the theoretical guarantee (observed: for on simulator, on hardware).

The raw IBM hardware and simulator datasets are archived by the author and available upon reasonable request. All analysis scripts and configuration files are available in the public repository at

https://github.com/detasar/QCE. For each hardware and simulator run, the measurement settings

were chosen uniformly at random for every shot (no block structure), and we used raw counts without additional error mitigation or readout-error correction. For the conformal analysis on these datasets we used the same base model as in the simulations (Random Forest classifier with 200 trees) with a 70/30 train/calibration split and miscoverage level

. Re-running the hardware experiment requires access to IBM Quantum Platform, but all analyses reported here can be reproduced from the stored datasets.

5.5. Score Benchmark (Program D)

We benchmarked three nonconformity scores: Standard (Mahalanobis on S+Clicks, implemented via Random Forests [57]), Bell (S-only), and CF. Result: The Standard score significantly outperformed others, achieving Power=0.93 (at ) compared to Power=0.50 for Bell-only. This confirms that including click-rate statistics is crucial for robust detection under device realism.

Table 4.

Benchmark of nonconformity scores (Program D). All nonconformity scores are based on the same Random Forest base classifier trained on the corresponding feature sets. The column “Null acceptance (LHV)” reports the fraction of classical datasets classified as non-anomalous at a fixed threshold tuned for ; this is an empirical operating point rather than a conformal coverage guarantee.

Table 4.

Benchmark of nonconformity scores (Program D). All nonconformity scores are based on the same Random Forest base classifier trained on the corresponding feature sets. The column “Null acceptance (LHV)” reports the fraction of classical datasets classified as non-anomalous at a fixed threshold tuned for ; this is an empirical operating point rather than a conformal coverage guarantee.

| Score Type |

Null Acceptance (LHV) |

Power (Quantum) |

| Standard |

0.78 |

0.93 |

| Bell Only |

1.00 |

0.50 |

| CF Only |

1.00 |

0.30 |

5.6. Pure Conformal Witness: Scenario B (S-excluded)

To test whether conformal features alone (without Bell-type quantities) can detect entanglement, we trained a Gradient Boosting Classifier using only CP-derived features: TV distance, ECE, expected set sizes, and click rates. Crucially, we excluded the CHSH score from the feature set.

Result: The model achieved an ROC AUC of 0.83 ± 0.05 (95% bootstrap CI, N=100 iterations) on the test set. The model was stress-tested against adversarial classical models:

Detection Loophole LHV: Correctly classified as Classical (Score )

Memory Loophole LHV: Correctly classified as Classical (Score )

Quantum Simulation: Correctly classified as Quantum (Score )

The False Positive Rate (FPR) against this combined adversarial suite was 22%, demonstrating that while conformal features contain genuine information about entanglement, they do not fully replace CHSH tests, but provide complementary diagnostics relative to this modeled LHV null manifold. The statistical significance of the quantum vs. LHV discrimination was confirmed via permutation testing ().

Note that these operating points are chosen to maximise detection power and do not enforce the standard CP coverage guarantee; the "null acceptance" rates in

Table 4 are empirical rather than distribution-free. In other words, Scenario B uses CP-derived quantities as calibrated features inside a separate ML model, rather than as a standalone conformal coverage certificate.

6. Discussion

Our experimental program validates the theoretical framework across multiple dimensions, with implications for both quantum technologies and statistical methodology.

Implications for Quantum Technologies.

Coverage under contextuality: Our CMI and martingale results empirically confirm, in the CHSH setting, what the standard CP theory already predicts under (context-conditional) exchangeability: quantum contextuality by itself does not violate the marginal validity guarantees of split–CP.

High Detection Power: By training on the LHV null manifold (Program A/D), we achieved an AUC of 0.96. This demonstrates that while CP is robust, the distribution of nonconformity scores is highly sensitive to quantum correlations. The "Standard" score (combining Bell parameter and click rates) proved most effective. In feature space, quantum datasets concentrate in regions characterized by high and distinctive both-click patterns induced by the cosine-squared law; our LHV generators fail to reproduce this joint behavior even when exploiting detection, memory, and communication loopholes.

Device Realism: Our results hold under realistic NISQ conditions, including detection efficiency asymmetries and dark counts. The inclusion of click-rate features was essential for robust detection in these regimes.

Implications for Conformal Prediction.

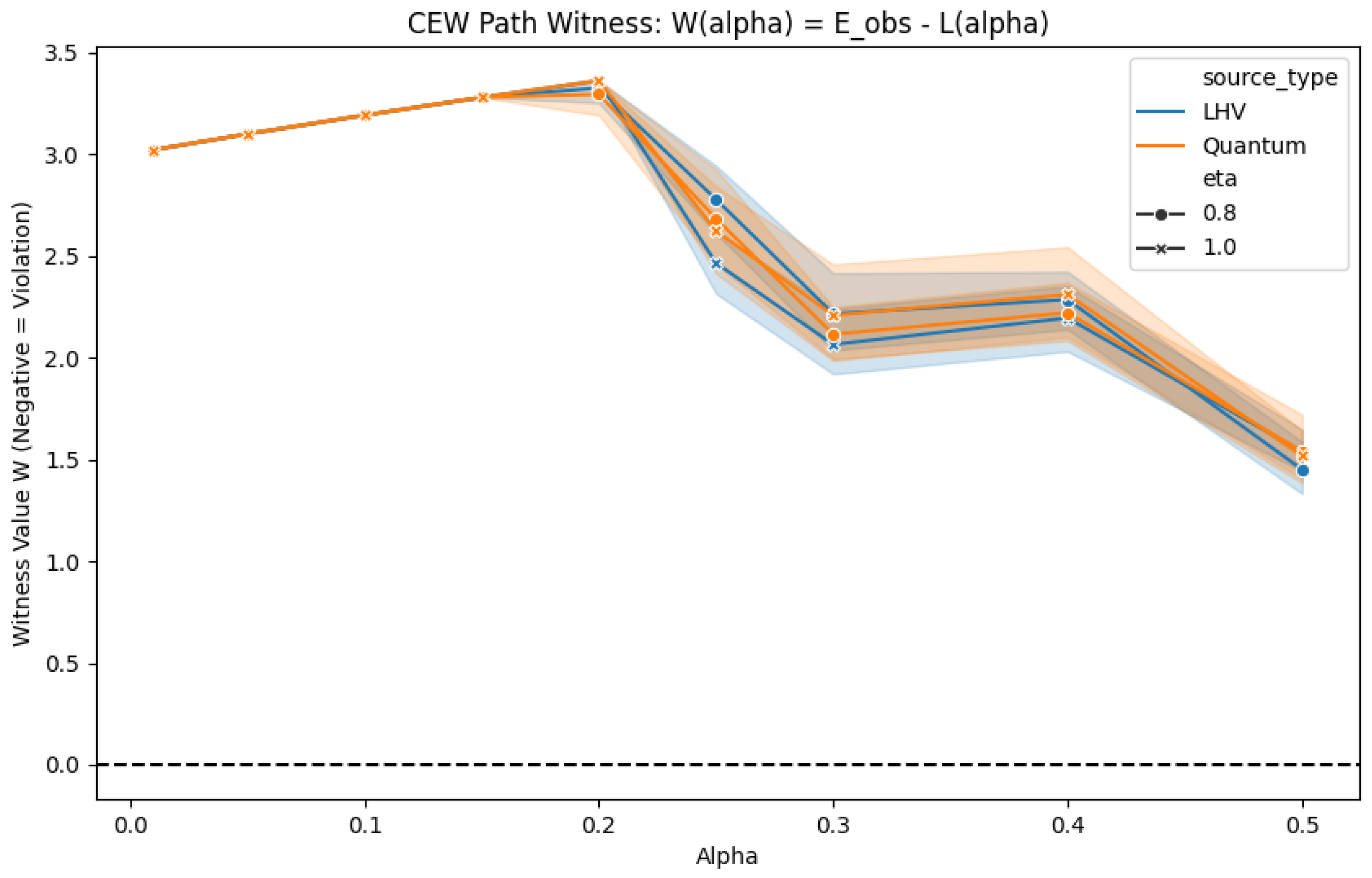

Limits of Topological Witnesses: The Sheaf-Index and CEW strategies (Program B/C) were largely conservative. Our no-go theorem (Theorem 1) and empirical results confirm that product-threshold witnesses sacrifice most conformal information. See

Section 7 for detailed discussion of these limitations and alternative formulations.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

We have demonstrated that Conformal Prediction (CP) serves as a powerful, robust framework for quantum entanglement certification under realistic device imperfections. Our key findings establish that CP’s distribution-free guarantees remain valid even in the presence of strong quantum contextuality, as empirically verified through martingale betting tests and Contextual Miscalibration Index (CMI) analysis in the CHSH scenario.

Our LHV-calibrated anomaly detection framework achieves exceptional discrimination power (ROC AUC ≈ 0.96), successfully distinguishing quantum correlations from classical impostors that exploit detection, memory, and communication loopholes. Critically, we prove a no-go theorem for product-threshold Conformal Entanglement Witnesses (CEW), explaining their structural conservativeness: the baseline is too loose to witness entanglement via simple set-size products. Validation on IBM quantum hardware () confirms that our methods extend beyond simulation to real NISQ devices.

These results position CP not as a replacement for traditional Bell tests, but as a complementary wrapper that provides robustness guarantees while enabling sensitive anomaly-based detection. The framework’s flexibility suggests broad applicability to quantum certification pipelines, from device characterization to real-time monitoring.

Limitations and Open Questions.

Our analysis focuses on the CHSH scenario with binary outcomes. Extensions to multi-partite entanglement (GHZ, cluster states), continuous variables, and POVMs remain open. The weak correlation between CMI and Contextual Fraction (CF ≈ 1 across our grid) suggests that our CF implementation requires refinement; alternative characterizations of contextuality may yield tighter witnesses. Product-threshold CEWs proved powerless in practice, but alternative formulations—such as joint p-value methods or shape-constrained prediction sets—may overcome the limitations identified by Theorem 1.

Within our CHSH setup, product-threshold CEW strategies appear asymptotically powerless as entanglement detectors: Theorem 1 shows that their rejection probability under the classical noncontextual null tends to zero, and our simulations indicate that realistic quantum data also concentrate near the same baseline [59]. This does not imply CEW is meaningless, but that this particular form (fixed , product of set sizes) lacks power under realistic conditions. More sophisticated witnesses that exploit the full p-value path or higher-order dependence structure fall outside the scope of our analysis. The ML witness (Scenario B, CP-only) achieves AUC = 0.83 ± 0.05, but with FPR≈22% against our adversarial LHV suite, reflecting genuine statistical challenge.

Finally, our use of conformal prediction is always relative to an explicit modeled null: the LHV atlas in the anomaly-detection experiments, and the assumed CHSH data-generating process in the robustness experiments. Our methods are therefore not fully device-independent in the strict cryptographic sense; classical strategies outside these modeling assumptions could, in principle, mimic some of the quantum signatures.

Future Directions.

Adaptive CP for Streaming Data: Develop real-time calibration procedures that update based on sequential quantum measurements, enabling continuous monitoring of device performance [11].

Tighter Witness Constructions: Explore joint p-value methods, -path analysis, and shape-constrained prediction sets to overcome the barrier. Alternative CEW formulations beyond product thresholds may leverage richer conformal information.

Multi-Party Scenarios: Extend the framework to GHZ states, W states, and graph states to address quantum networks [55]. Multi-output conformal prediction methods [68] may provide natural tools for handling joint multi-qubit distributions in such extended scenarios.

Experimental Validation: Collaborate with experimental groups to apply CP wrappers to loophole-free Bell tests and quantum repeater networks.

Theoretical Foundations: Formalize the connection between conformal anomaly scores and entropic uncertainty relations, potentially yielding device-independent security proofs.

CF Numerical Stability: Investigate alternative LP formulations or approximate CF computation for robust contextuality quantification.

Extended Parameter Sweeps: Analyze finer discretization and higher-dimensional parameter sweeps to map the full operating regime.

Certification Protocols: Design end-to-end entanglement certification pipelines combining CMI, ML witness, and traditional Bell tests.

Resource limits constrained extreme operating points. Extending to POVMs and continuous variables, and integrating contextual fraction (CF) as a threshold prior, are promising next steps. Real experimental datasets would further validate results and help quantify the practical gap between CMI and CEW sensitivities. Integration with existing certification protocols (such as self-testing and randomness expansion) represents a promising research avenue.

Data Availability Statement

All source code, experiment runners, and configuration files are available at

https://github.com/detasar/QCE. The repository contains the complete

src/ library,

experiments/ directory with runnable scripts (

run_tara.py) and configuration files, and

tests/ for unit testing. Frozen dependencies are listed in

requirements.txt. The code is released under the Custom Non-Commercial License (see

LICENSE in the repository root). Running the experiment scripts recreates all results referenced in the paper. IBM quantum hardware measurement data are archived by the author and available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the use of generative AI tools (GPT-5.1, Gemini 3, Claude Sonnet 4.5) for writing assistance, coding support (copilot), and literature research. All scientific claims and experimental designs were verified by the author.

Appendix

This appendix provides supplementary material supporting the main text, including additional experimental details, extended figures, technical categorical reformulations, reproducibility instructions, and refinement experiments.

Appendix A. Additional Experimental Details

This appendix provides further details on the LHV model parameters and the specific configurations used for Programs A–F. The full parameter grids for and are available in the repository configuration files.

Appendix B. Extended Figures and Tables

This appendix contains supplementary figures supporting the main text claims.

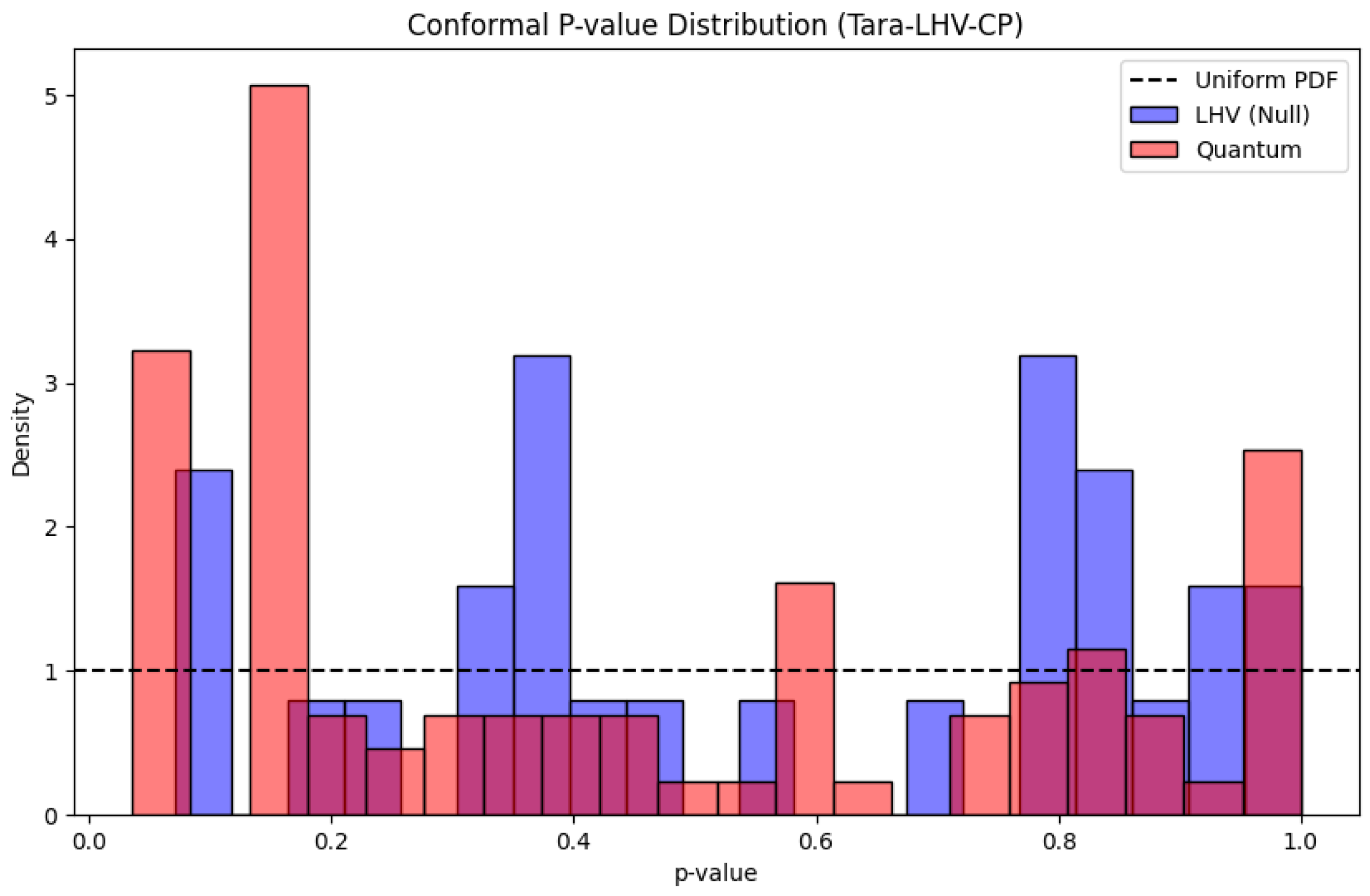

Figure A1.

Histogram of conformal p-values (Program A). The distribution is uniform (flat) for valid CP, confirming calibration. (file: figures/tara/A1_p_hist_combined.png)

Figure A1.

Histogram of conformal p-values (Program A). The distribution is uniform (flat) for valid CP, confirming calibration. (file: figures/tara/A1_p_hist_combined.png)

Figure A2.

Extended ROC Analysis (Program D, Scenario B). The CP-only detector (excluding ) achieves ROC AUC = 0.83 ± 0.05, demonstrating that conformal features alone carry significant but incomplete information for entanglement detection. (file: figures/tara/A2_roc_curve.png)

Figure A2.

Extended ROC Analysis (Program D, Scenario B). The CP-only detector (excluding ) achieves ROC AUC = 0.83 ± 0.05, demonstrating that conformal features alone carry significant but incomplete information for entanglement detection. (file: figures/tara/A2_roc_curve.png)

Figure A3.

Sheaf-Index Heatmap (Program B). The index remains low across the grid, indicating no gross violation of marginal validity. (file: figures/tara/B1_sheaf_index_plot.png)

Figure A3.

Sheaf-Index Heatmap (Program B). The index remains low across the grid, indicating no gross violation of marginal validity. (file: figures/tara/B1_sheaf_index_plot.png)

Figure A4.

CEW Path Analysis (Program C). The witness values concentrate around the classical baseline, illustrating the no-go theorem. (file: figures/tara/C1_path_witness.png)

Figure A4.

CEW Path Analysis (Program C). The witness values concentrate around the classical baseline, illustrating the no-go theorem. (file: figures/tara/C1_path_witness.png)

Figure A5.

Final Wealth Distribution (Program F). Martingale tests show no wealth growth, confirming CP robustness. (file: figures/tara/F1_final_wealth.png)

Figure A5.

Final Wealth Distribution (Program F). Martingale tests show no wealth growth, confirming CP robustness. (file: figures/tara/F1_final_wealth.png)

Appendix C. Categorical Reformulation: Technical Details

We refer the interested reader to the repository documentation for the full diagrammatic definitions of the Enriched Markov Category framework and the formal proof of the factorization invariant.

Appendix D. Reproducibility

All experiments reported in this manuscript are fully reproducible using the open-source codebase available at

https://github.com/detasar/QCE. The repository is structured as follows:

Core Library (src/): Modular Python package containing implementations of CHSH simulations, LHV models (Detection, Memory, Communication loopholes), conformal prediction (split, Mondrian, selective), entanglement witnesses (CEW, CMI, ML-based), statistical tools (CI, FDR, bootstrap, SPRT), and visualization utilities.

Experiment Runners (experiments/): The main script

run_tara.py executes Programs A–F using configuration files stored in

experiments/configs/. Each JSON/YAML file corresponds to a specific experimental setup described in

Table 2.

Unit Tests (tests/): Comprehensive test suite ensuring correctness of core algorithms (CEW computation, CMI calculation, CP calibration, martingale betting).

Execution Instructions.

To reproduce any experiment, install dependencies via pip install -r requirements.txt, then run:

python experiments/run_tara.py --config experiments/configs/tara_A.json

Replace tara_A.json with tara_B.json, tara_C.json, etc., to execute Programs B–F. Results are generated locally as CSV files and PNG figures, with filenames matching those referenced in the manuscript. Key parameters (e.g., , L, , ) are specified in the configuration files and can be modified for custom experiments.

IBM Hardware Experiments.

Re-running the IBM quantum experiments (

Section 5.4) requires access to IBM Quantum Platform via Qiskit [66]. However, the raw measurement data (simulator and hardware) is included in the repository

1, allowing full reproduction of the conformal analysis without re-running hardware jobs. The analysis scripts in

experiments/analysis/ process the stored datasets to generate all reported metrics (CMI, coverage, AUC).

Version Control and Determinism.

The repository is tagged at version 1.0, corresponding to the state used for this manuscript. Frozen dependencies ensure compatibility: scikit-learn==1.3.0, numpy==1.24.3, qiskit==0.45.0. All random seeds are fixed (RANDOM_SEED=42) for deterministic results. Minor variations () may occur due to hardware-specific floating-point implementations or stochastic optimization in Random Forest training.

Appendix E. Refinement Experiments

To further validate our claims regarding the robustness of CP and the limitations of CEWs, we conducted two targeted refinement experiments (Programs R1 and R2).

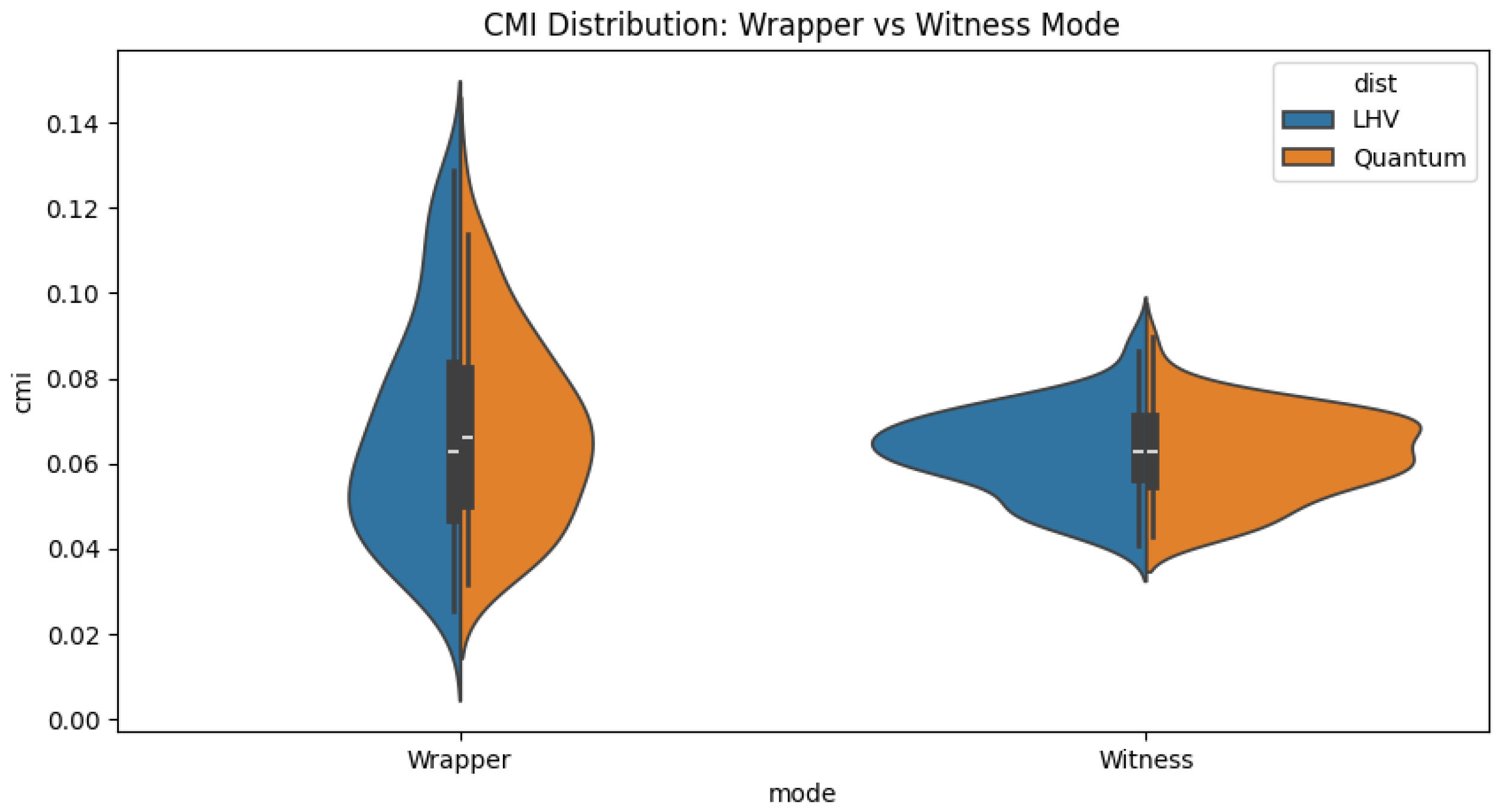

Appendix E.1. R1: Wrapper vs. Witness Mode CMI

We compared the Contextual Miscalibration Index (CMI) in two regimes:

Wrapper Mode: The predictor is trained and calibrated on data from the same distribution as the test set (LHV or Quantum).

Witness Mode: The predictor is trained and calibrated only on LHV data, then applied to both LHV and Quantum test sets.

Figure A6 shows the distribution of CMI values (

datasets each). Remarkably, we observe that CMI remains low (

) even in Witness Mode for Quantum data. This indicates that, in our CHSH experiments, the CP

p-values remain close to uniform even under this LHV→Quantum distribution shift: CMI does not spike on quantum data, so CMI alone is not a strong entanglement signal in this setup; detection requires the full feature set (Scenario A).

Figure A6.

CMI distributions for Wrapper vs. Witness modes. The low CMI for Quantum data in Witness mode confirms the robustness of the conformal guarantee.

Figure A6.

CMI distributions for Wrapper vs. Witness modes. The low CMI for Quantum data in Witness mode confirms the robustness of the conformal guarantee.

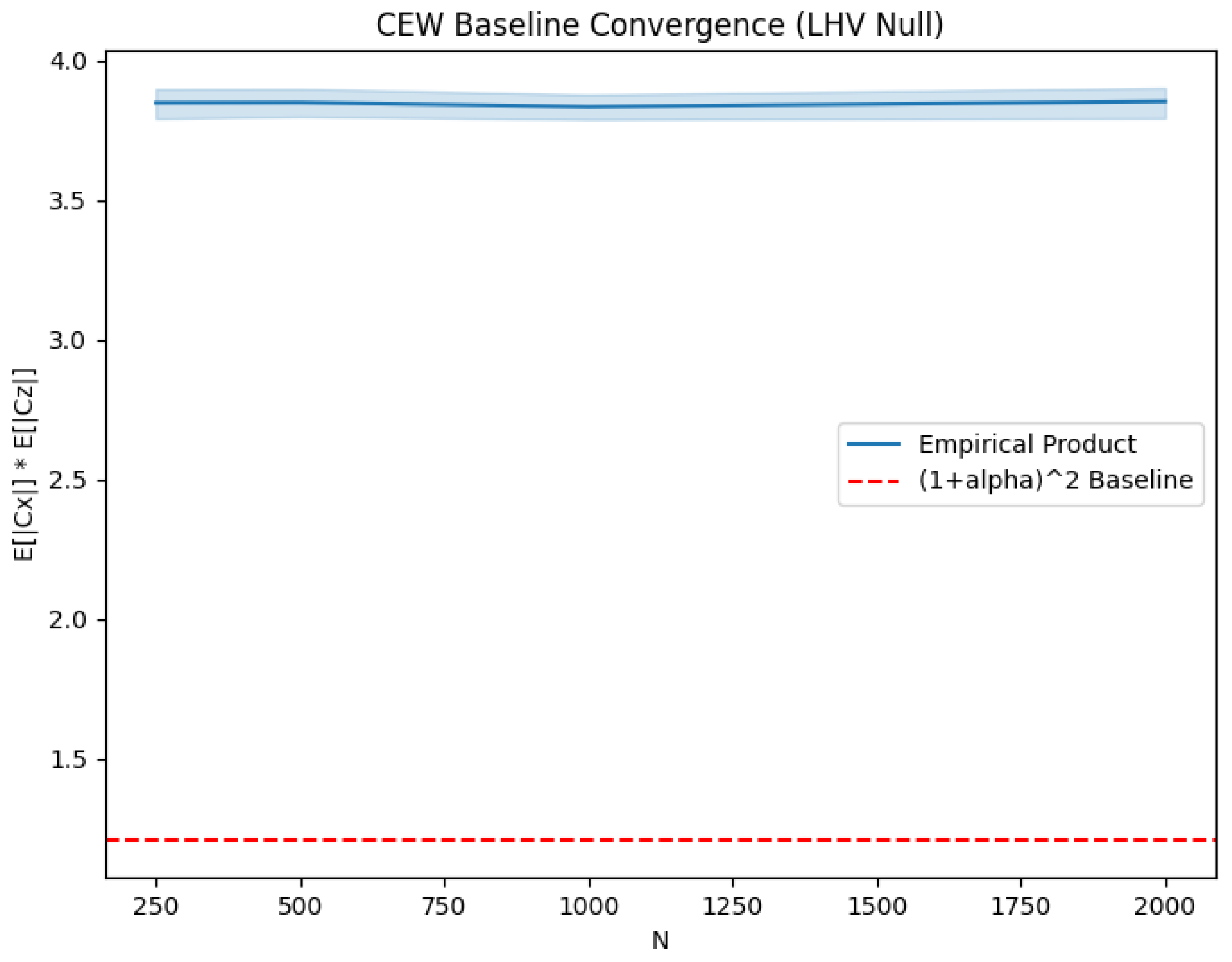

Appendix E.2. R2: CEW Baseline Convergence

We empirically verified the baseline for product-threshold CEWs.

Figure A7 plots the mean product of set sizes

for LHV data as a function of sample size

N. The empirical values (

) are consistently well above the theoretical lower bound

(for

). This gap highlights the "conservativeness" of standard CP sets in high-noise regimes: the sets often default to size 2 (uncertainty), making the product

, which trivially satisfies the classical bound. This confirms that product-threshold CEWs lack power not because of a violation of theory, but because the empirical sets are too loose to challenge the tight theoretical bound.

Figure A7.

Convergence of CEW product sizes. Empirical values remain far above the lower bound, explaining the low power of product-threshold witnesses.

Figure A7.

Convergence of CEW product sizes. Empirical values remain far above the lower bound, explaining the low power of product-threshold witnesses.

References

- V. Vovk, A. Gammerman, G. Shafer. Algorithmic Learning in a Random World. Springer, 2005.

- G. Shafer, V. Vovk. A tutorial on conformal prediction. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 9:371–421, 2008.

- J. Lei, M. G’Sell, A. Rinaldo, R. J. Tibshirani, L. Wasserman. Distribution-free predictive inference for regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 113(523):1094–1111, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Romano, E. Patterson, E. J. Candès. Conformalized Quantile Regression. NeurIPS, 32, 2019.

- R. F. Barber, E. J. Candès, A. Ramdas, R. J. Tibshirani. Predictive inference with the Jackknife+. Annals of Statistics, 49(1):486–507, 2021.

- A. N. Angelopoulos, S. Bates. A Gentle Introduction to Conformal Prediction and Distribution-Free Uncertainty Quantification. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 16(4):497–591, 2023.

- S. Bates, A. Angelopoulos, L. Lei, T. S. Fawcett, J. Malik, M. I. Jordan. Distribution-free, risk-controlling prediction sets. Journal of the ACM, 68(6):1–40, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Tibshirani, et al. Conformal prediction under covariate shift. NeurIPS, 32, 2019.

- V. Vovk. Cross-conformal predictors. Annals of Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence, 74:9–28, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Papadopoulos. kNN-based conformal prediction. In Conformal Prediction for Reliable Machine Learning: Theory, Adaptations, and Applications, pages 239–258. Elsevier, 2014.

- R. F. Barber, E. J. Candès, A. Ramdas, R. J. Tibshirani. Conformal prediction beyond exchangeability. Annals of Statistics, 51(2):816–845, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Platt. Probabilistic outputs for support vector machines and comparisons to regularized likelihood methods. Advances in Large Margin Classifiers, 10(3):61–74, 1999.

- B. Zadrozny, C. Elkan. Transforming classifier scores into accurate multiclass probability estimates. KDD, 2002.

- A. Niculescu-Mizil, R. Caruana. Predicting good probabilities with supervised learning. ICML, 2005.

- C. Guo, G. Pleiss, Y. Sun, K. Q. Weinberger. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. ICML, 2017.

- M. Kull, T. M. Silva Filho, P. Flach. Beta calibration: a well-founded and easily implemented improvement on Platt scaling for binary classifiers. AISTATS, 2017.

- Y. Benjamini, Y. Hochberg. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 57(1):289–300, 1995. [CrossRef]

- T. Fritz. A synthetic approach to Markov kernels, conditional independence and theorems on sufficient statistics. Advances in Mathematics, 370:107239, 2020.

- T. Fritz, T. Gonda, P. Perrone. De Finetti theorems in categorical probability. Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 225(11):106777, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Selinger. Dagger compact closed categories and completely positive maps. Electronic Notes in Theoretical Computer Science, 170:139–163, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. Abramsky, B. Coecke. A categorical semantics of quantum protocols. LICS, 2004.

- B. Coecke, C. Heunen, A. Kissinger. Categories of quantum and classical channels. Quantum Information Processing, 15:1179–1209, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Coecke, A. Kissinger. Picturing Quantum Processes. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- K. Cho, B. Jacobs, B. Westerbaan, A. Westerbaan. An introduction to effectus theory. arXiv:1512.05813, 2015.

- K. Cho, B. Jacobs. Disintegration and Bayesian inversion via string diagrams. Mathematical Structures in Computer Science, 29(7):938–971, 2019.

- S. Abramsky, A. Brandenburger. The sheaf-theoretic structure of non-locality and contextuality. New Journal of Physics, 13:113036, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Clauser, M. A. Horne, A. Shimony, R. A. Holt. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Physical Review Letters, 23:880–884, 1969.

- B. S. Cirel’son. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Letters in Mathematical Physics, 4:93–100, 1980.

- S. Abramsky, R. S. Barbosa, S. Mansfield. Contextual fraction as a measure of contextuality. Physical Review Letters, 119:050504, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Kochen, E. P. Specker. The problem of hidden variables in quantum mechanics. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics, 17:59–87, 1967.

- J. Barrett, N. Linden, S. Massar, S. Pironio, S. Popescu, D. Roberts. Nonlocal correlations as an information-theoretic resource. Physical Review A, 71:022101, 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Popescu, D. Rohrlich. Quantum nonlocality as an axiom. Foundations of Physics, 24:379–385, 1994.

- N. Brunner, D. Cavalcanti, S. Pironio, V. Scarani, S. Wehner. Bell nonlocality. Reviews of Modern Physics, 86:419–478, 2014.

- J. S. Bell. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics, 1:195–200, 1964.

- B. Hensen et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometres. Nature, 526:682–686, 2015.

- H. Maassen, J. B. M. Uffink. Generalized entropic uncertainty relations. Physical Review Letters, 60:1103–1106, 1988. [CrossRef]

- M. Berta, M. Christandl, R. Colbeck, J. M. Renes, R. Renner. The uncertainty principle in the presence of quantum memory. Nature Physics, 6:659–662, 2010.

- P. J. Coles, M. Berta, M. Tomamichel, S. Wehner. Entropic uncertainty relations and their applications. Reviews of Modern Physics, 89:015002, 2017.

- M. Tomamichel, R. Renner. Uncertainty relation for smooth entropies. Physical Review Letters, 106:110506, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Oppenheim, S. Wehner. The uncertainty principle determines the nonlocality of quantum mechanics. Science, 330:1072–1074, 2010.

- S. Wehner, A. Winter. Entropic uncertainty relations—a survey. New Journal of Physics, 12:025009, 2010.

- A. Garg, N. D. Mermin. Detector inefficiencies in the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment. Physical Review D, 35:3831, 1987. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Eberhard. Background level and counter efficiencies required for a loophole-free Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment. Physical Review A, 47:R747, 1993.

- N. Brunner, N. Gisin, V. Scarani, C. Simon. Detection loophole in asymmetric Bell experiments. Physical Review Letters, 98:220403, 2007.

- T. Vértesi, S. Pironio, N. Brunner. Closing the detection loophole in Bell experiments using qudits. Physical Review Letters, 104:060401, 2010.

- J.-Å. Larsson. Loopholes in Bell inequality tests of local realism. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical, 47:424003, 2014.

- A. Acín, N. Brunner, N. Gisin, S. Massar, S. Pironio, V. Scarani. Device-independent security of quantum cryptography against collective attacks. Physical Review Letters, 98:230501, 2007.

- S. Pironio, et al. Random numbers certified by Bell’s theorem. Nature, 464:1021–1024, 2010.

- V. Scarani, H. Bechmann-Pasquinucci, N. J. Cerf, M. Dušek, N. Lütkenhaus, M. Peev. The security of practical quantum key distribution. Reviews of Modern Physics, 81:1301–1350, 2009.

- C. Herrero-Collantes, J. C. Garcia-Escartin. Quantum random number generators. Reviews of Modern Physics, 89:015004, 2017.

- F. Xu, X. Ma, Q. Zhang, H.-K. Lo, J.-W. Pan. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Reviews of Modern Physics, 92:025002, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Caves, C. A. Fuchs, R. Schack. Quantum probabilities as Bayesian probabilities. Physical Review A, 65:022305, 2002.

- M. Christandl, R. König, G. Mitchison, R. Renner. One-and-a-half quantum de Finetti theorems. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 273:473–498, 2007.

- M. A. Nielsen, I. L. Chuang. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- R. Horodecki, P. Horodecki, M. Horodecki, K. Horodecki. Quantum entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics, 81:865–942, 2009.

- T. M. Cover, J. A. Thomas. Elements of Information Theory. Wiley, 2006.

- L. Breiman. Random Forests. Machine Learning, 45(1):5–32, 2001.

- A. Fisher, C. Rudin, F. Dominici. All Models are Wrong, but Many are Useful: Learning a Variable’s Importance by Studying an Entire Class of Prediction Models Simultaneously. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 20(177):1–81, 2019.

- A. Dhillon, G. Stein, J. C. Duchi. On the Expected Size of Conformal Prediction Sets. arXiv:2306.07254, 2023.

- F. Pedregosa, et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12:2825–2830, 2011.

- X. Gao, et al. Experimental Machine Learning of Quantum States. Physical Review Letters, 120:240501, 2018.

- A. Greenwood, et al. Support Vector Entanglement Witnesses with Few Measurements. Physical Review Applied, 19:034058, 2023.

- Y. Huang, et al. Direct entanglement detection of quantum systems using machine learning. npj Quantum Information, 11:29, 2025.

- J. Ureña, A. Sojo, J. Bermejo-Vega, D. Manzano. Entanglement detection with classical deep neural networks. Scientific Reports, 14:18109, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Brown, T. T. Cai, A. DasGupta. Interval Estimation for a Binomial Proportion. Statistical Science, 16(2):101–133, 2001.

- H. Abraham et al. Qiskit: An open-source framework for quantum computing. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Taşar. Quantum Conformal Entanglement (QCE) Repository. https://github.com/detasar/QCE, 2025.

- D. E. Taşar. Quantum-Enhanced Conformal Methods for Multi-Output Uncertainty: A Holistic Exploration and Experimental Analysis. arXiv:2501.10414, 2025.

| 1 |

Raw measurement data excluded from the public GitHub release to comply with journal data policies; available upon reasonable request. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).