1. Introduction

In the past century, the global ecological environment has undergone significant changes. Among them, a series of ecological problems caused by climate warming increasingly threaten the sustainable development of human society, and therefore have attracted more and more attention from governments and scientists around the world. Vegetation is an important component of global ecosystems and an intermediate link connecting soil, atmosphere, and moisture [

1]. Surface vegetation participates in the surface energy cycle, water cycle, biogeochemical cycle and other processes through photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration, etc., and plays an important role in regulating climate, maintaining soil and water, and improving ecological conditions [

2,

3]. At the same time, because vegetation has obvious interannual and seasonal variation characteristics, it serves as an “indicator” in global changes [

4,

5]. Vegetation coverage represents the overall ecological environment to a large extent, and its condition is directly related to the stability and security of the regional ecological environment [

6].

Since the launch of the first Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS) carrying a Multispectral Scanner (MSS) in 1972, people’s perspective on regional environmental monitoring has gradually shifted from land to sky. Research on vegetation cover changes in different regions based on RS (Remote Sensing) and GIS (Geographic Information System) technology has become a focus [

7], and has been continuously deepened in many fields such as ecological environment protection and restoration, land use planning, disaster risk assessment, and climate change research [

8]. Currently, the main methods used to study vegetation cover change characteristics include Leaf Area Index (LA1), Fraction of absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation (FPAR), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Ratio vegetation index (RVI) and kernel NDVI [

9,

10]. Among them, NDVI has become the most classic vegetation index in practical applications due to its advantages of simple calculation, high vegetation monitoring sensitivity, and high spatial-temporal adaptability, and is also an important indicator for evaluating regional and local vegetation changes [

11,

12,

13].

Continuous and stable NDVI data are the basis and prerequisite for long-term monitoring of surface vegetation characteristics [

14]. The more commonly used satellites include: Landsat series, MODIS (Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer), Sentinel-2, etc. Among them, the most typical Landsat series satellite data, whose multispectral band image spatial resolution is 30 m, is widely used in vegetation coverage type mapping and condition investigation. However, its 16-day revisit period, coupled with the extended impact of cloud and rain weather, seriously affects its application in vegetation dynamic monitoring [

15]. The vegetation products of MODIS data have good consistency and multi-temporal characteristics, and have good applications in monitoring vegetation phenology and status dynamics. However, its spatial resolution is low, making it difficult to capture the differences in spatial characteristics within a small area and meet refined vegetation monitoring and management [

16]. Seninel-2 data has the characteristics of high spatial-temporal resolution, and can more accurately monitor vegetation changes since 2016 than Landsat and MODIS data. However, for longer time scales and specific areas, the sensitivity of high temporal resolution MODIS data and high spatial resolution Landsat data to vegetation index is still unknown and requires further comparison and verification.

At present, most research focuses on the monitoring of spatial-temporal dynamic change characteristics of vegetation coverage, the driving mechanism of regional vegetation coverage changes, and the qualitative analysis and prediction of regional vegetation coverage using multi-model combination methods. There have been considerable results in these aspects. For example, in the direction of monitoring spatial-temporal change characteristics, the study found that the interannual variation of NDVI in most areas of China (80.1%) has shown an increasing trend in the past 40 years, and the areas showing a degradation trend are mainly concentrated in the Northeast, northern Xinjiang and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [

17]; In the direction of studying influencing factors, based on geographical detectors, using methods such as differentiation, factor detection, and interaction detection [

18], the impact of climate change, land use change and other factors on vegetation coverage was studied, and it was found that climate change (especially precipitation) is one of the main factors leading to changes in vegetation coverage [

19]. However, based on the topography, longitude and latitude of different regions, its impact on vegetation coverage varies [

20,

21]. In addition, as the scope and intensity of human activities continue to expand, human factors have gradually become an important factor affecting changes in vegetation coverage [

19,

22]. In terms of qualitative analysis of influencing factors, people usually use the Pearson correlation coefficient and the Spearman rank correlation coefficient to build correlation models to explore the positive and negative correlations of influencing factors on vegetation cover changes [

10]. With the continuous follow-up of research, people have introduced partial correlation coefficients to build models on this basis [

23,

24,

25], further improving data accuracy and reducing the error of other factors on correlation results.

The Qinling Mountains are one of the key areas for global biodiversity. It is the dividing line between the north and south of China’s climate and an important ecological security barrier in China. Its north and south slopes have typical climate differences and vegetation distribution differences [

26,

27]. At the same time, the Qinling Mountains are a transition zone and sensitive area to climate change in China. Studies have shown that the air temperature in the Qinling Mountains has changed to varying degrees at different spatial-temporal scales [

27,

28]. The northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi have large areas of forest, wetland, grassland and other ecosystems, which provide important ecological services to the region. However, these ecosystems are at risk of degradation and destruction due to human activities and climate change. Therefore, this paper uses multi-source remote sensing data to jointly analyze the spatiotemporal variation characteristics and influencing factors of vegetation index in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains and its north area in Shaanxi from 2001 to 2023. The research results are expected to provide scientific basis for regional vegetation dynamic monitoring, environmental protection and restoration, provide decision-making reference for ecological environment construction and coordinated development of man-land relations in the northern foothills of Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi, and achieve sustainable development of the ecological environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains and its north area in Shaanxi are an important ecological barrier and water conservation area for the Guanzhong Plain. The administrative division includes 15 counties (districts) of Xi ‘an, Baoji and Weinan, such as Baqiao, Chang ‘an, Huxian, Zhouzhi, Tongguan, Linwei, Lintong, Huayin, Hua County, Lantian, Meixian, Taibai, Baoji, Qishan and Weibin [

29]. The geographical location and altitude distribution of the study area are shown in

Figure 1.

Affected by the terrain, the Qinling Mountains have formed a complex climate environment and rich and diverse climate resources. The Qinling Mountains have four distinct seasons, with rain and heat occurring at the same time. The climate elements are obviously different with the increase of altitude. In the area below 1800 m above sea level, the annual average air temperature is 10-16℃, the average air temperature of the coldest month is 15℃, the average air temperature of the hottest month is 20-28℃, and the annual precipitation is 600-900 mm; in the area with an altitude of 1800-2800 m, the annual average air temperature is 2-10℃, the coldest month air temperature is -9-1℃, the hottest month air temperature is 10-20℃, and the annual precipitation is 800-1000 mm; In the zone above 2800 m, long winter and no summer are the most significant climate features. Low air temperature is the most significant climate feature. The average annual air temperature does not exceed 2℃, the air temperature in the coldest month is below -9℃, and the average air temperature in the hottest month is below 10℃. Due to the high altitude, the water vapor content in the airflow decreases, and thus the precipitation also decreases, with the annual precipitation being less than 1000 mm [

30]. Rich climate resources have given birth to rich vegetation resources. The vegetation at the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains shows obvious vertical zonation. From bottom to top, there are evergreen broadleaved forest, deciduous broadleaved forest, evergreen needle-leaved forest and sub-alpine grass. In addition, the Guanzhong Plain area is suitable for farming, and its natural vegetation has been replaced by artificial vegetation. The main vegetation type is cultivated vegetation, including crops that crop once a year and three crops every two years, cold-resistant economic crops, and deciduous fruit trees [

31] (

Figure 2).

2.2. Data

The Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS data used in this study were all downloaded through the GGE platform. Sentinel-2 is a high spatial-temporal resolution multispectral imaging satellite. The revisit period of one satellite is 10 days, and the two complement each other. The revisit period is 5 days and the spatial resolution is 20m; the Landsat data revisit period is 16 days. The spatial resolution is 30m; MODIS data has high temporal resolution and can provide 8-day vegetation index with a spatial resolution of 500m.

The Landsat 8 L2 and Sentinel-2 L2 data have been preprocessed by radiometric correction, geometric correction and atmospheric correction. De-cloud processing is performed before calculation to avoid cloud interference. The MODIS image preprocessing process includes radiometric calibration, geometric correction, geometric cropping, atmospheric correction and cloud removal. The wavelength bands selected for the study are red light band and near-infrared band. The maximum value synthesis method was used to obtain monthly time series NDVI data in the study area. In addition, the study further calculated spatial data such as annual average NDVI, growing season (April-October), spring (March-May), summer (June-August) and autumn (September-November) average NDVI.

Precipitation and air temperature data come from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Center (

https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/home) [

33,

34,

35,

36], and the time range is 2001- 2022, the temporal resolution is monthly and the spatial resolution is 1 km. DEM data comes from NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC) (

https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/news/release-nasadem-data-products/), with a spatial resolution of 30m .

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. NDVI

The NDVI can reflect the background effects of the plant canopy, such as soil, wet ground, snow, dead leaves, roughness, etc., and is related to vegetation cover. Although NDVI is more sensitive to changes in soil background, NDVI can eliminate most of the irradiance changes related to instrument calibration, solar angle, terrain, cloud shadow and atmospheric conditions, and enhance the response ability to vegetation, which is the most widely used among more than 40 existing vegetation indices [

37]. NDVI is defined as [

38]:

In the formula, NIR is the reflection value of the near-infrared band in the remote sensing image, and RED is the reflection value of the red light band in the remote sensing image. NDVI always ranges from -1 to +1, but there are no clear boundaries for each type of land cover. When the NDVI value is negative, it’s probably water. When the NDVI value is close to +1, it is likely to be dense vegetation. When NDVI is close to zero, it may be bare land or urbanized areas.

2.3.2. Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficient is used to calculate the correlation of monthly NDVI data of Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS. The calculation formula is:

In the formula, is the correlation coefficient between variables x and y; i is the number of samples; and are the NDVI data of month i respectively; and are the mean values of x and y during the study period, respectively.

The partial correlation coefficient can temporarily ignore the influence of other factors and analyze the correlation degree between the two factors separately [

24]. Its calculation formula is:

In the formula, r is the partial correlation coefficient between i and j when k is used as the control variable; j and k represent different climate factors respectively. i, j and k in this article represent NDVI, average air temperature and precipitation respectively.

The value range of the correlation coefficient is -1~1. A positive value represents a positive correlation between variables, and a negative value represents a negative correlation between variables. The greater the absolute value of the correlation coefficient, the stronger the correlation between variables.

2.3.3. Linear Regression Trend Analysis

In this paper, a single linear regression equation is used to calculate the NDVI interannual trend, and the slope of the linear regression equation is taken as the NDVI interannual trend rate [

24,

39]. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula, Slope is the slope of the linear regression equation fitting NDVI and time variables, n is the number of years in the study period, and is the average NDVI in year i. When Slope>0, it means that the research object is on an upward trend, otherwise it is on a downward trend. The larger the absolute value of Slope, the faster the NDVI changes. The F test was used to determine the significance of any trend; a trend was considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Consistency and Difference Analysis of Various Remote Sensing Data

3.1.1. Spatial Consistency and Dissimilarity

This article selects February and August 2022 as representatives of low and high NDVI values in the study area to conduct adaptability analysis of Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS remote sensing images.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show the February, August and annual average NDVI spatial distribution maps of Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS remote sensing images of the study area in 2022, in which the white areas represent missing values. The greater the degree of phase missing, the more incomplete the monthly NDVI spatial distribution in the entire study area is.

Figure 5 shows the missing rate of the monthly data synthesized from the three types of data.

Judging from the spatial distribution of NDVI (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), the distribution patterns of Sentinel-2 and MODIS data in February and August and the annual average NDVI are relatively consistent. The high-value areas in February were concentrated in the Qishan County-Fufeng County area. In August, obvious north-south stratification of NDVI could be seen. The NDVI value in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains south of the Wei River was significantly higher than that in the Guanzhong Plain. This is consistent with the distribution of the annual average NDVI, but the Landsat data does not show this feature well.

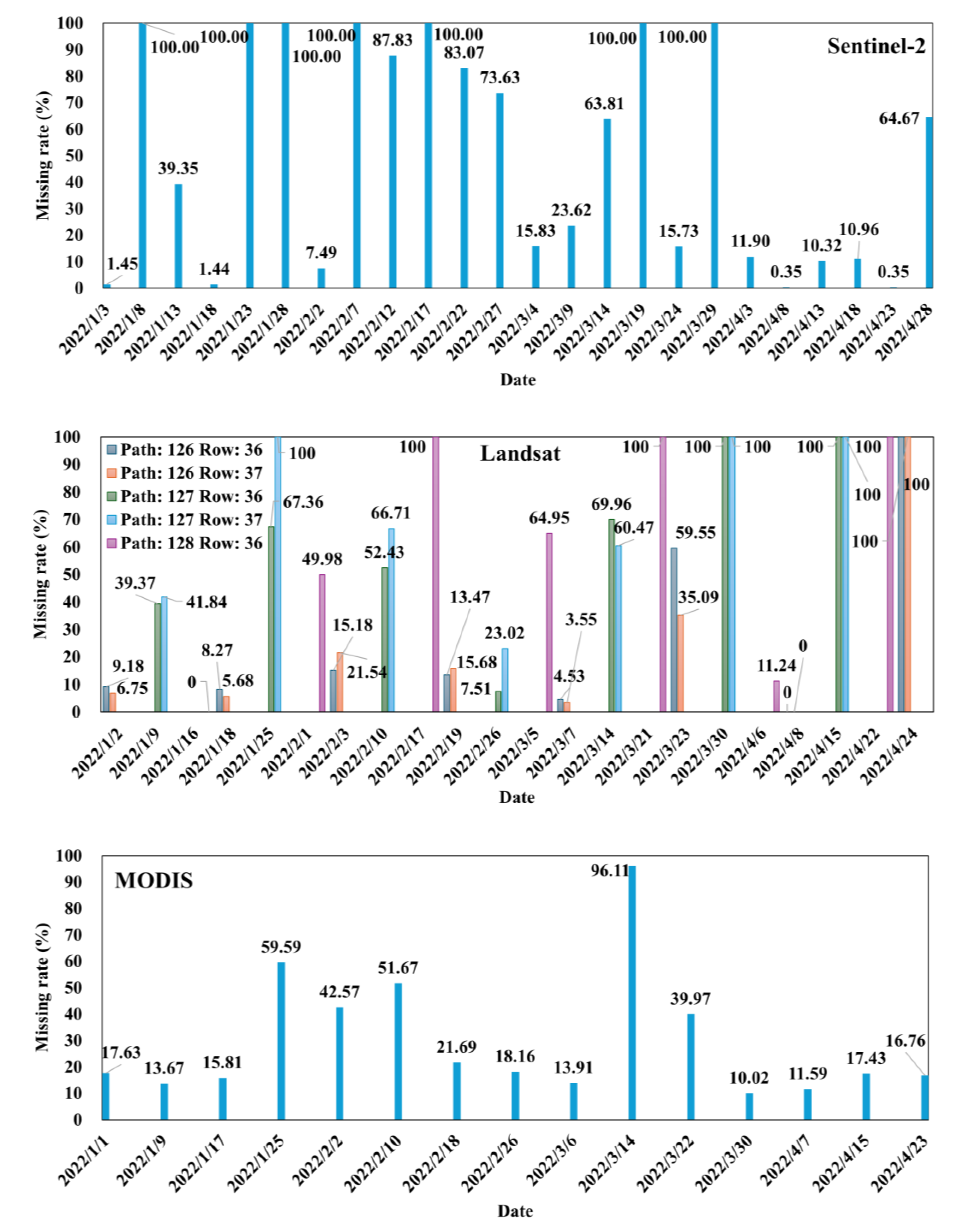

From the perspective of the missing rate (

Figure 5), Sentinel-2 and MODIS monthly NDVI phases have a smaller degree of missing, most of the missing rates are less than 20%, and both have good spatial integrity. The missing rates of these two types of data in October are relatively high, and the missing values of MODIS data are mainly concentrated in the area west of Lishan Mountain, where there is less vegetation (

Figure 2). The missing rate in Landsat data is relatively high in most months, especially in October, November and December.

3.1.2. Temporal Consistency and Variability

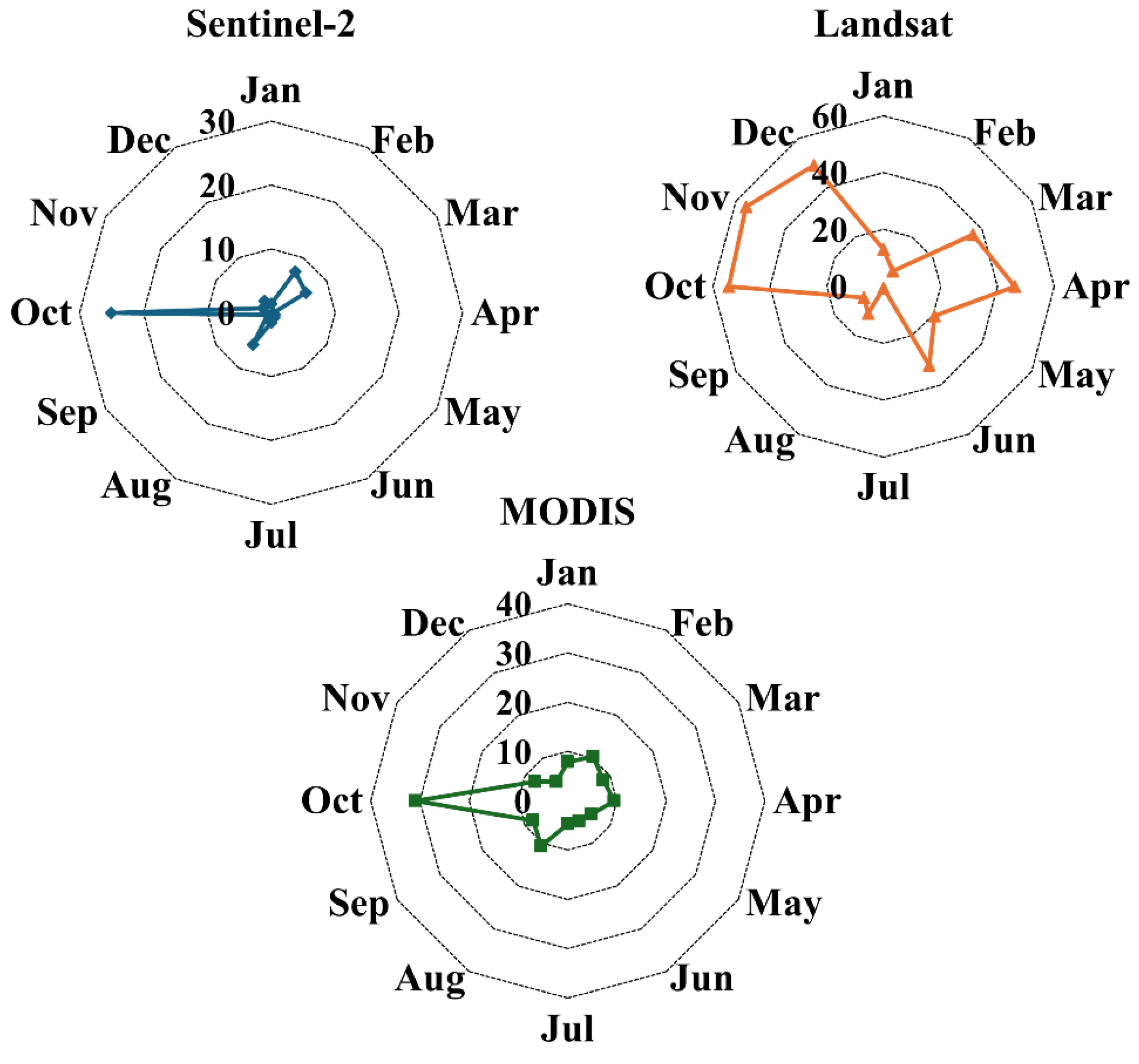

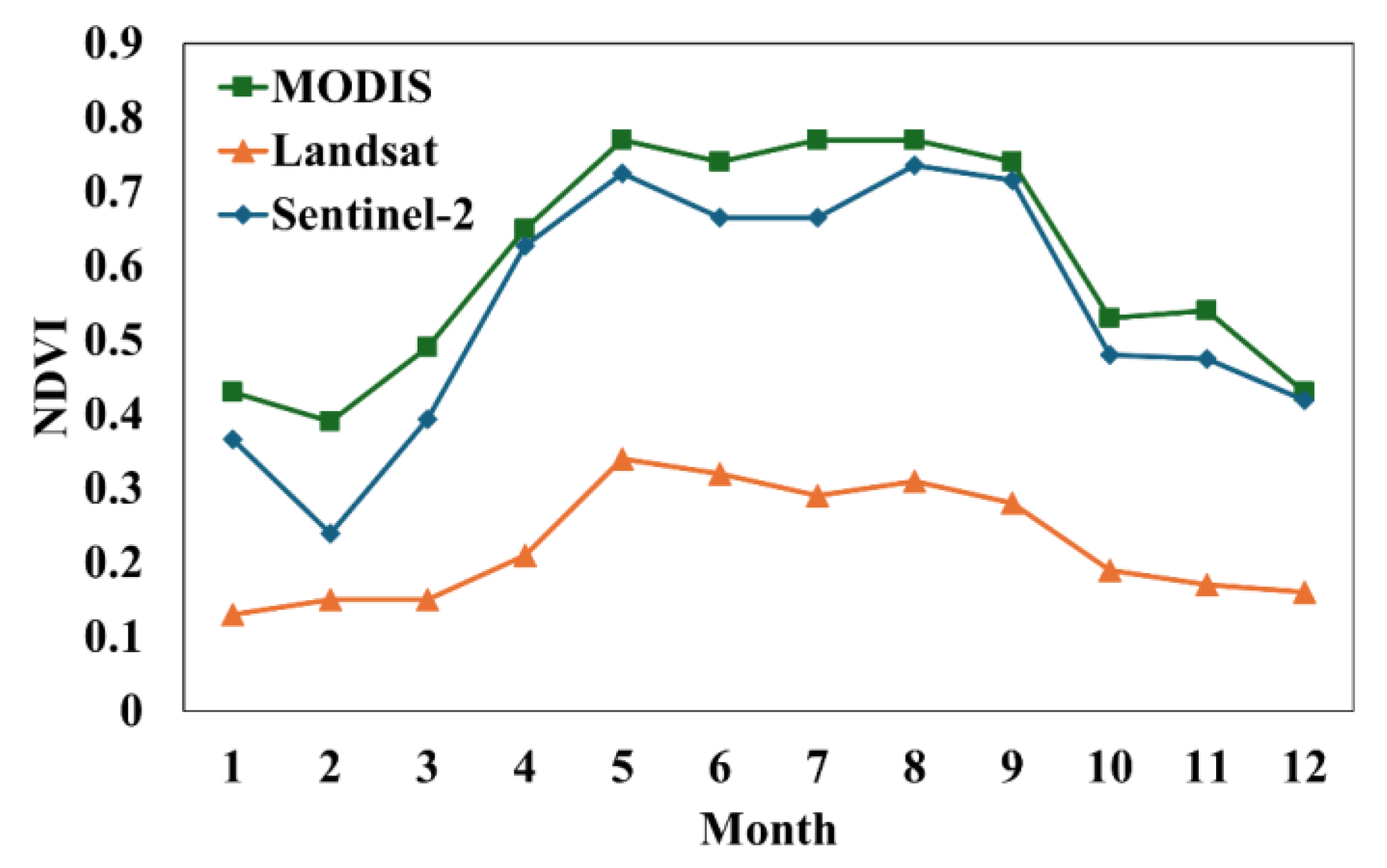

By analyzing the monthly NDVI data of Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS in 2022 (

Figure 6), it can be seen that the three data are relatively consistent in capturing phenological changes in vegetation growth, and the month in which the NDVI peak appears is basically the same, but the minimum NDVI value of Sentinel-2 and MODIS appears in February, while the minimum value of Landsat is in January. The former is consistent with existing studies [

31]. In terms of numerical values, the monthly NDVI values of MODIS and Sentinel-2 are generally greater than the monthly NDVI values of Landsat. By calculating the correlation between the three, it was found that Sentinel-2 has a strong correlation with the MODIS monthly NDVI value (R=0.97, P<0.01).

In order to further analyze the temporal consistency and difference of the three types of data, we selected daily data from January to April to compare the sensitivity of Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS data to vegetation changes. We calculate the availability of three types of NDVI data, as shown in

Figure 7. It can be seen that due to the influence of clouds and fog, the missing rate of daily NDVI data is generally high. Half of the Sentinel-2 images have a missing rate of more than 50%. There are 3 MODIS images with a missing rate of more than 60%. However, comparing

Figure 5, we can see that the high time resolution of Sentinel-2 and MODIS data can better make up for the problem of missing detection rate. The missing rate of synthetic monthly NDVI data is basically stable at less than 10%, while the Landsat data with a revisit period of 16 days occupy two images in a large study area (Path: 127, Row: 36; Path: 127, Row: 37) had a very high missing rate, and only 2/7 groups of images had a missing rate below 50%, and the monthly NDVI data synthesized from these 5 images could not compensate for the missing rate (

Figure 5).

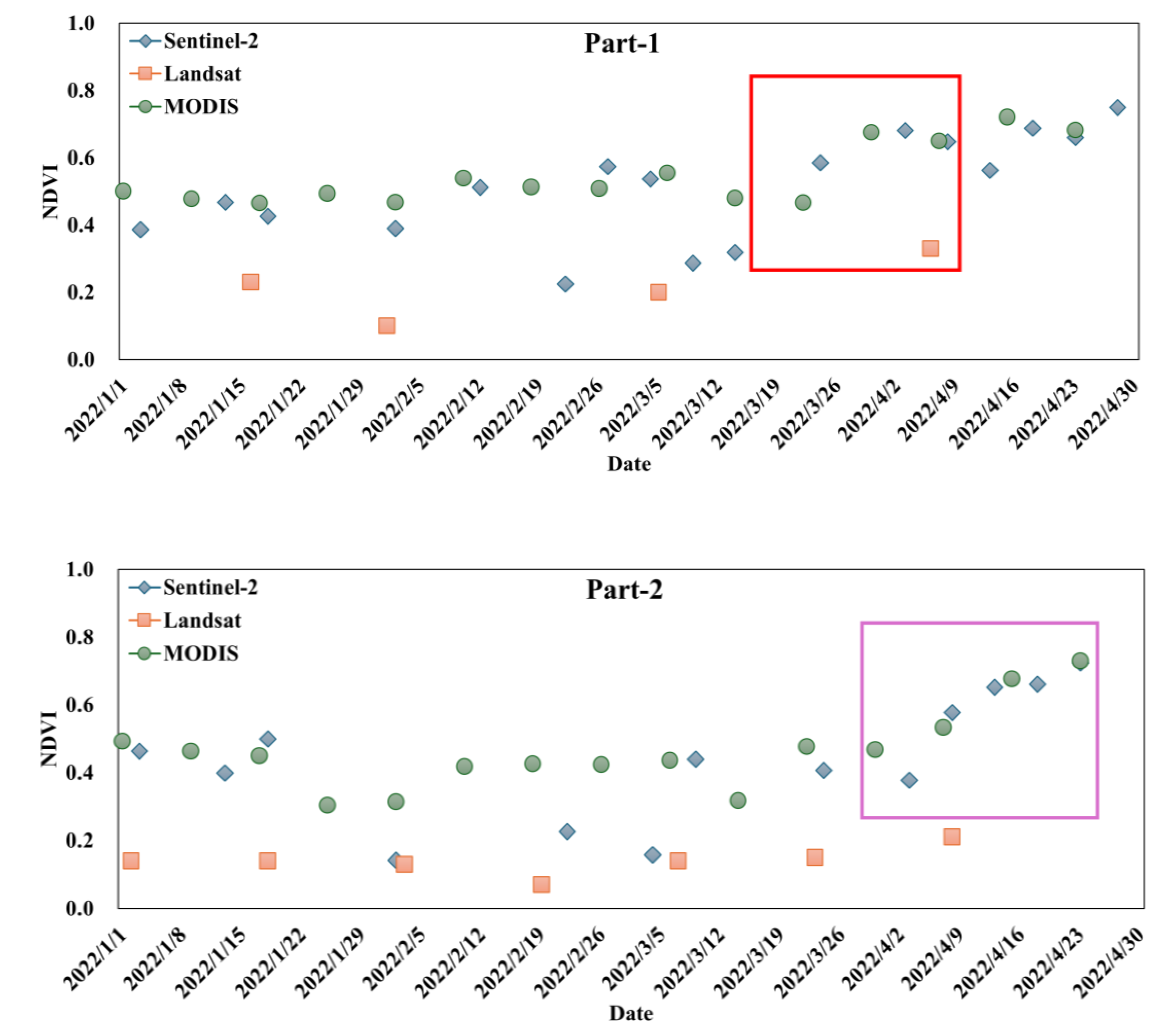

According to vegetation type (

Figure 2) and daily NDVI loss rate (

Figure 7) in the study area, we selected two sub-regions to compare the ability of three kinds of data to refine vegetation phenological characteristics of early cropland (Part-1) and forest land (Part-2) (

Figure 8). Overall, the time series curves of these two sub-regions are relatively complete. As time goes by, the NDVI of the three data all show a trend of first decreasing and then increasing. The low peak is between January 22 and February 5. The NDVI values of Sentinel-2 and MODIS data are relatively close, with fewer Sentinel-2 NDVI values showing abnormalities, while the NDVI values of Landsat data are still significantly low, and the data volume is small, making it impossible to accurately capture changes in vegetation. In addition, there are certain differences in the phenological characteristics of the two sub-regions. The NDVI of cropland basically maintained around 0.5 from January to March, and began to increase significantly from mid-to-late March to early April (red frame line area in

Figure 8), which was consistent with the time of winter wheat jointing in this region [

40]. The rapid growth of NDVI in forest land began in early April (pink frame line area in

Figure 8). This is due to the fact that after April, the air temperature rises, the precipitation increases, and the vegetation growth speed accelerates [

6]. Overall, Sentinel-2 and MODIS data have good consistency in the time series of cropland and forest land, and have the ability to refine early vegetation phenological characteristics.

3.2. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Evolution of NDVI

3.2.1. Long-Term Spatial and Temporal Variation Characteristics of NDVI

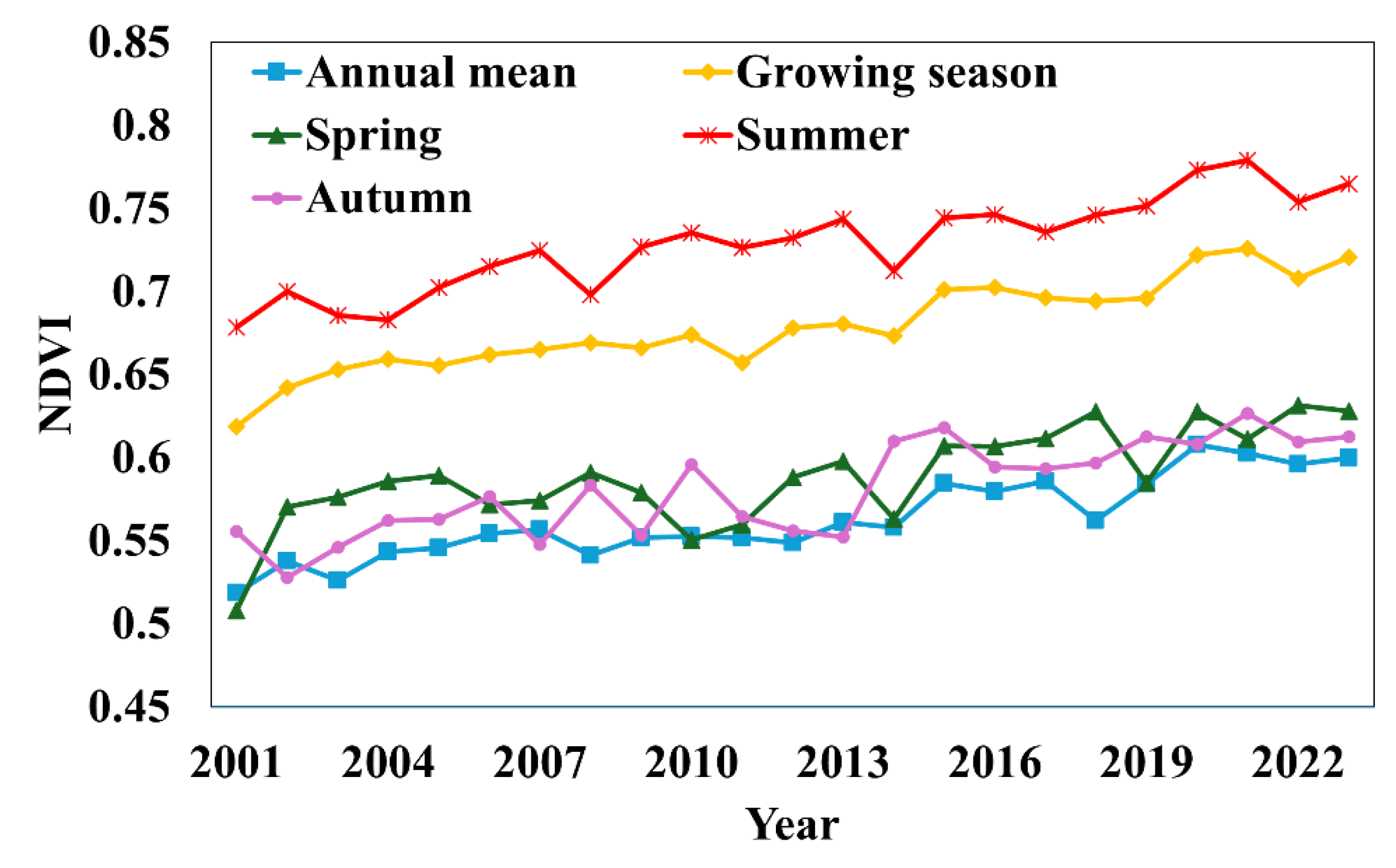

Since the NDVI calculated by MODIS data and Sentinel-2 data have higher spatiotemporal consistency in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains and its north area in Shaanxi, MODIS will be selected to obtain the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of NDVI in the study area from 2001 to 2023 (

Figure 9). As can be seen from the figure, the annual mean NDVI value in the study area fluctuates between 0.52 and 0.61, showing an increasing trend (Slope=0.003), and passes the 99% significance test (

Table 1). The average NDVI in the growing season is higher than the annual mean NDVI, with a difference of 0.10~0.13, showing a more significant growth trend. From the time series of NDVI changes in spring, summer and autumn (

Figure 9), it can be seen that in 23 years, NDVI was the largest in summer, while spring and autumn alternated with each other, fluctuating between 0.51~0.63, 0.68~0.78 and 0.53~0.63, respectively. From the perspective of the changing trend of each season, it showed an upward trend, and the rising trend in summer and autumn was relatively faster, passing the significance test of 99% (

Table 1).

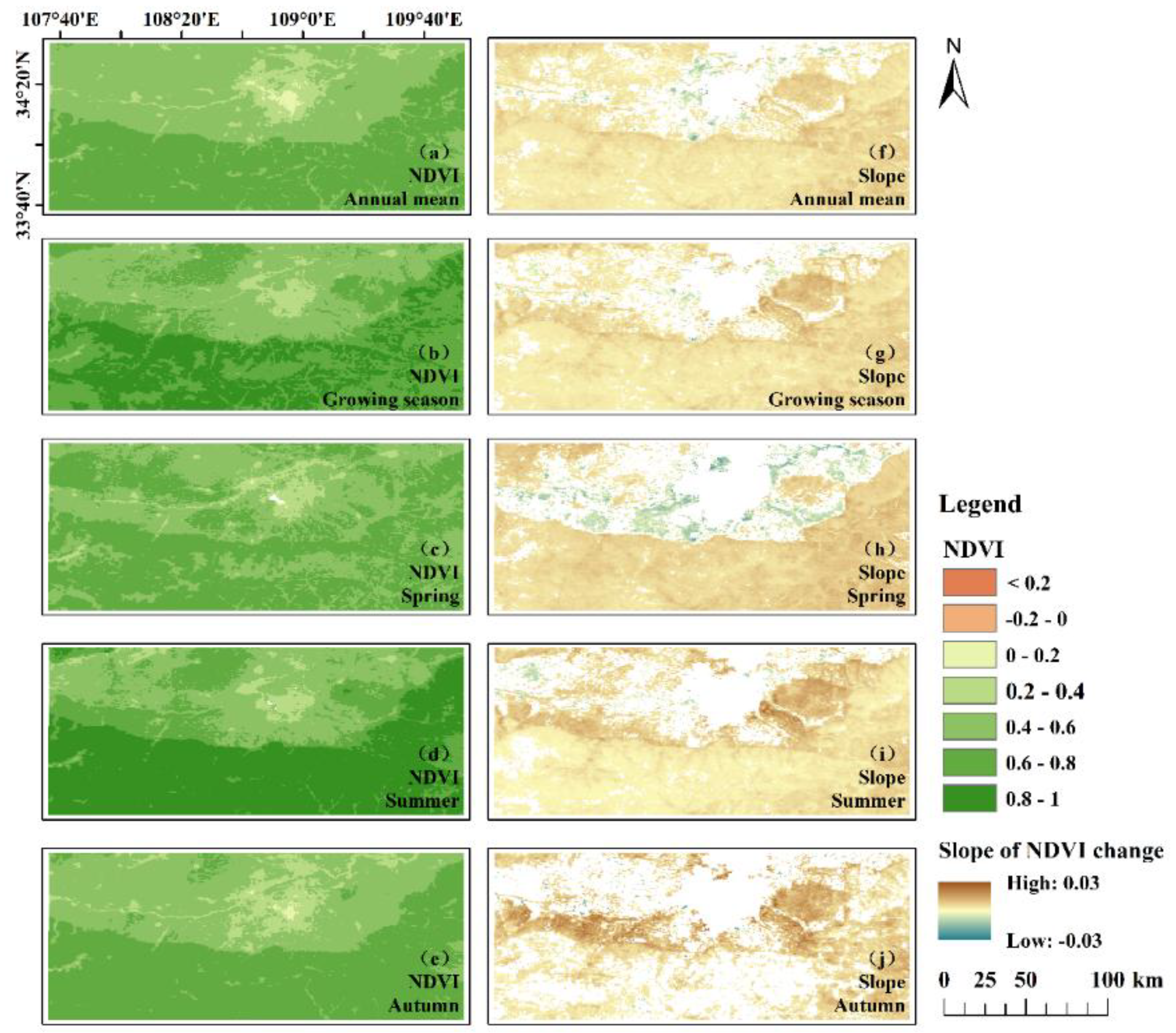

The multi-year mean NDVI in the study area from 2001 to 2023 generally shows a spatial distribution characteristic of higher in the south and lower in the north (

Figure 10 a-e), which is consistent with the altitude distribution (

Figure 1). The annual mean NDVI of the entire region is 0.56, with a maximum value of 0.78. Vegetation growth is in good condition, of which dense vegetation coverage (NDVI>0.6) accounts for 45.89%. The high NDVI value areas in summer, autumn and growing season are concentrated in the Qinling Mountains in the south of the study area, and the low NDVI value areas are mainly concentrated in the urban areas of the Guanzhong Plain. However, there is no obvious north-south difference in the multi-year average NDVI value in the study area in spring.

By analyzing the change rate of the multi-year mean NDVI in the study area from 2001 to 2023 (

Figure 10 h-j, the color area passed the 95% significance test), the NDVI in most areas of the study area showed a significant increasing trend. The substantial growth is mainly concentrated in the eastern part of the study area, especially in the Lishan Mountain area, while the areas with a decrease or no significant change in NDVI are mainly urban areas where human life and production are relatively frequent.

3.2.2. Change Characteristics of NDVI in the Past Five Years

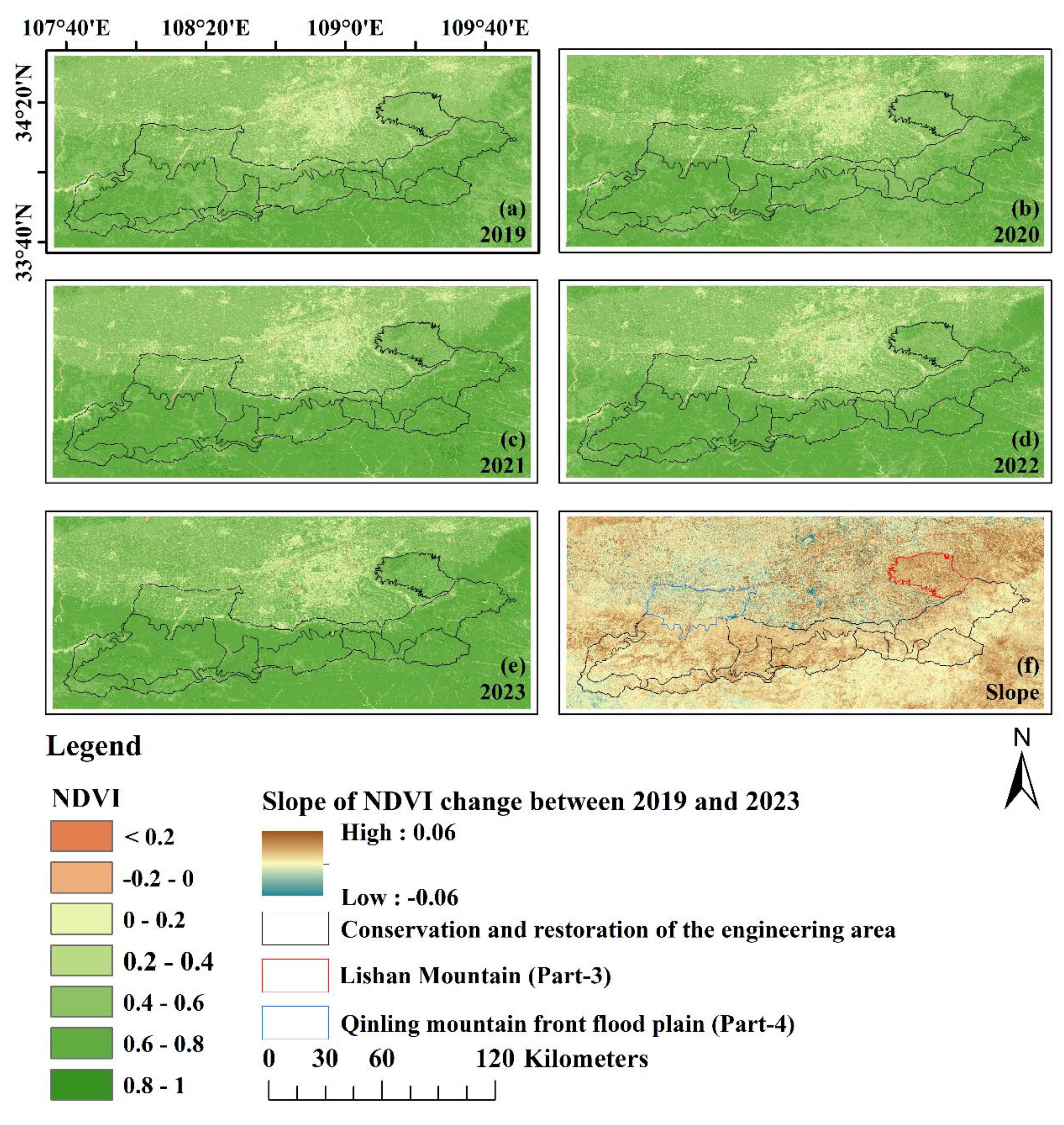

As can be seen from

Figure 9, in the past five years, there has been a fluctuating trend of NDVI rising first, then falling, and then rising again. Here, we use Sentinel-2 data with higher spatiotemporal resolution to monitor the vegetation changes at the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi in the past five years, with a view to providing data support for protection and management.

Figure 9 shows the spatial distribution characteristics of NDVI from 2019 to 2023. It can be seen that the overall distribution characteristics are relatively consistent with the multi-year mean of NDVI. The annual mean NDVI from 2019 to 2023 are 0.52, 0.53, 0.55, 0.54 and 0.57 respectively(

Figure 11a-e). This is consistent with the results obtained from MODIS NDVI data (

Figure 9). By calculating the slope of NDVI from 2019 to 2023, it was found that the NDVI showed an increasing trend in almost most areas, especially in the south and east of the study area. In addition, we observed that the NDVI in the main integrated protection and restoration project area of mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes, grass and sand in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi increased rapidly, especially in the Lishan Mountain area (red frame line area in

Figure 11f), but there was a large area of NDVI reduction in the western part of the Qinling mountain front flood plain (blue frame line area in

Figure 11f).

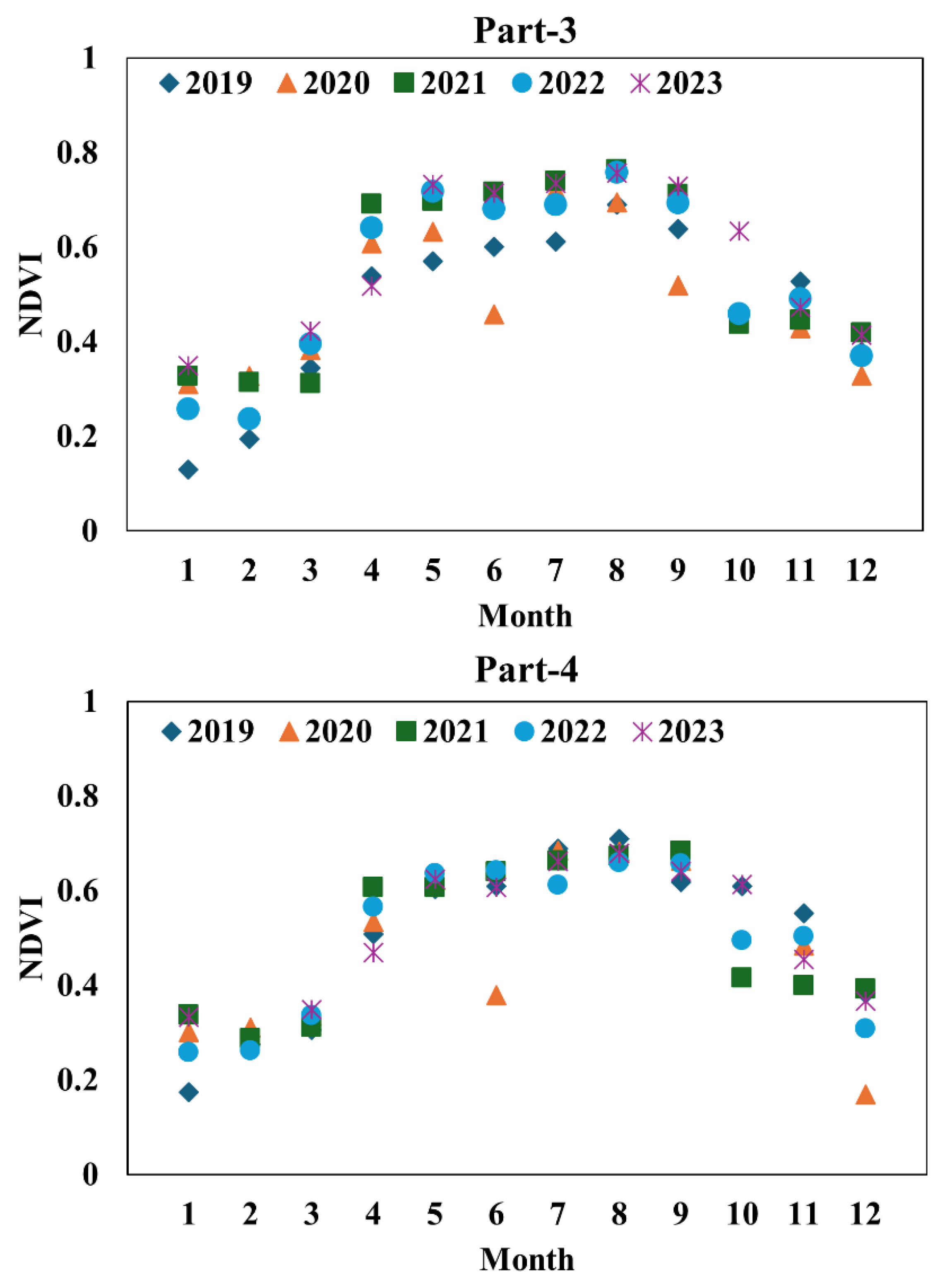

In order to further analyze the preliminary results of the ecological protection and restoration project, we selected the Lishan Mountain area (Part-3) and the Qinling mountain front flood plain (Part-4), two areas with opposite changing trends, to conduct NDVI analysis in the past five years. By comparison (

Figure 10), it can be seen that basically all months in the Lishan Mountain area show an increasing trend year by year, with a decrease in NDVI in 2022, but a significant increase in 2023, and the annual average NDVI in 2019-2023 are 0.47, 0.49, 0.55, 0.53 and 0.59, respectively. After consulting the information, the landscape project at the northern foothills of Qinling Mountains was launched in 2023. It mainly solves the ecological and environmental problems in the shallow hilly area of Lishan Mountain in the main body of the northern foothills of Qinling Mountains, including comprehensive management of water and soil erosion, land remediation, improvement of water source conservation functions, and vegetation restoration. The monitoring results (

Figure 12) can reflect the current effectiveness of the project. However, in the Part-4 area, which is also part of the ecological protection and restoration project area, the NDVI decreased to varying degrees every month in 2019-2023, especially during the growing season (April-October). In the future, we need to focus on the protection and restoration of this area.

4. Discussion

There are many influencing factors that cause changes in vegetation coverage, which can be divided into two major factors: natural and human activities [

41,

42,

43]. Natural factors involve climate factors and geographical environment. In this paper, precipitation and air temperature, which are closely related to the temporal and spatial variation of NDVI, are analyzed and discussed.

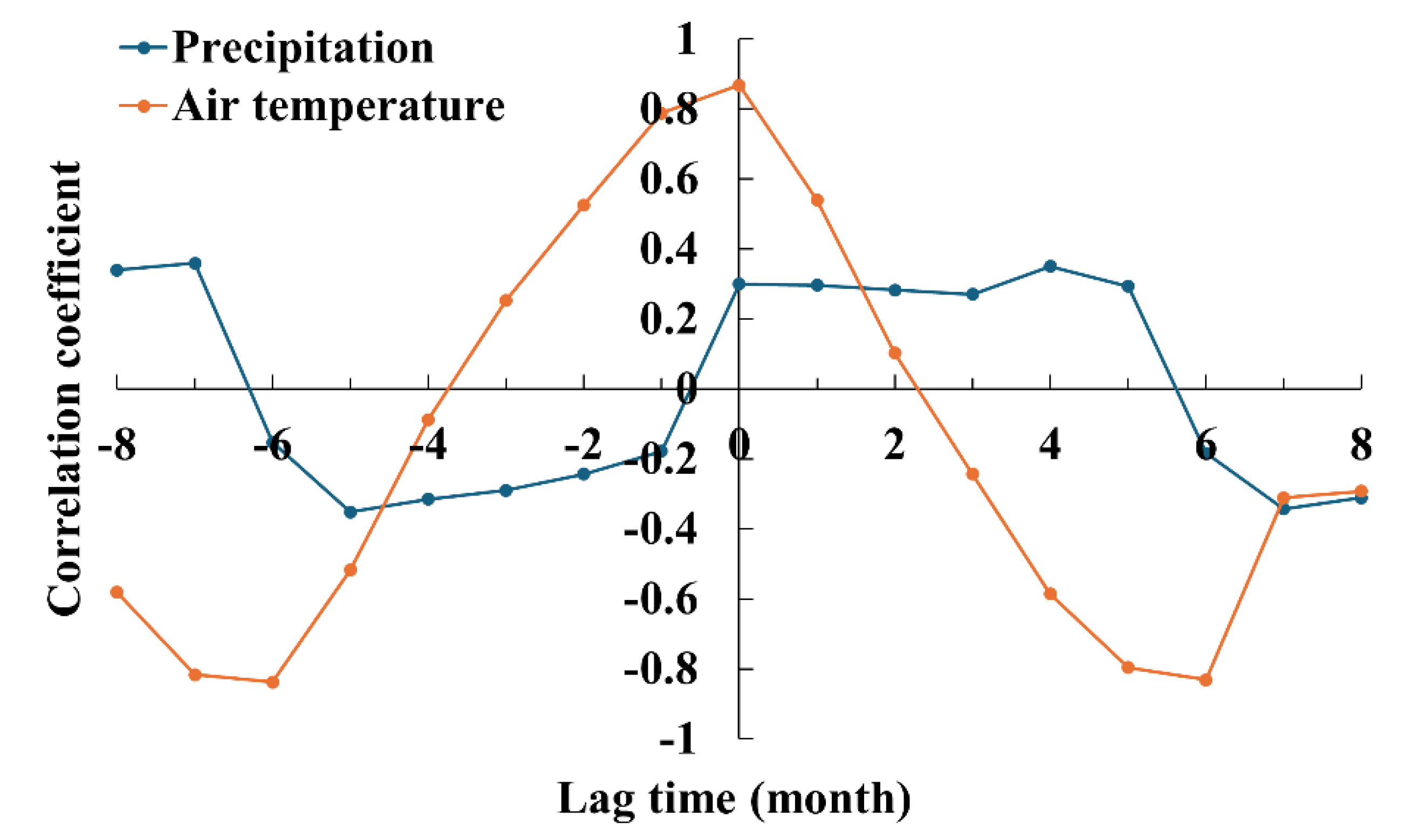

Figure 13 is the result of the lead-lag partial correlation analysis between monthly NDVI sequence changes and precipitation and air temperature in the study area from 2001 to 2022. The abscissa represents the lag time of monthly NDVI and climate factors. It can be found that the partial correlation between monthly NDVI and air temperature ( r=0.87, P<0.01) is much higher than the partial correlation with precipitation (r=0.30, P<0.01), and it is different from the lag effect of precipitation and air temperature. The lag effect of air temperature on monthly NDVI is positive for 1-2 months and negative for 3-8 months. The lag effect of precipitation on monthly NDVI was positive in 1-5 months and negative in 6-8 months. The lag effect of both on NDVI is positive in a short period of time, which indicates that vegetation growth can be controlled by coordinating climate in this region [

24,

44,

45].

Judging from the partial correlations between NDVI and precipitation and air temperature at different time scales (

Table 2), the correlation between air temperature and NDVI in spring is 0.55, passing 99% significance test, and the correlation between precipitation and NDVI is 0.49, passing 95% significance test. Except for spring, NDVI at other time scales has no significant correlation with precipitation and air temperature.

In summary, on the spring and monthly scales, precipitation and air temperature have a positive correlation with vegetation growth in the study area, and the influence of air temperature is more significant.

In this article, we only focuses on the spatiotemporal evolution of NDVI in the study area, its correlation with precipitation and air temperature, and the time-lag effect based on statistical methods. In the future, the response of NDVI to other influencing factors (such as relative humidity, sunshine hours, potential evapotranspiration, etc.) can be further studied, the contribution rate of climate factors and human activities to vegetation change can be quantitatively studied, and the driving mechanism of vegetation change can be further analyzed. In addition, positive human activity like the integrated protection and restoration project of the main mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes, grass and sand in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi is continuing to advance. In the future, high temporal resolution remote sensing data (such as Sentinel-2 and MODIS) will be used to further track the effectiveness of its protection and restoration.

5. Conclusions

The sensitivity of NDVI to vegetation phenological characteristics in the northern foothills of Qinling Mountains and its north area in Shaanxi province was compared and analyzed from Sentinel-2, Landsat and MODIS data, and the change characteristics and possible influencing factors of NDVI from 2001 to 2023 were analyzed from annual mean, growing season, spring, summer, autumn and monthly time scales. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Compared with Landsat images, Sentinel-2 images and MODIS images have better spatial and temporal consistency in obtaining monthly NDVI data at the northern foothills of Qinling Mountains and its north area in Shaanxi and refining vegetation phenological characteristics;

(2) From 2001 to 2023, spring, summer, autumn, growing season and annual mean NDVI showed a significant upward trend, and the average NDVI in growing season was 0.10-0.13 higher than that in annual mean NDVI, and the NDVI in summer was the largest, while the NDVI in spring and autumn alternated with each other. The large spatial increase of NDVI is mainly concentrated in the eastern part of the study area, especially in the Lishan Mountain region, while the areas where NDVI decreases or has no significant change are mainly urban areas where human life and production are relatively frequent.

(3) The NDVI in most areas of the study area showed an increasing trend from 2019 to 2023, especially the Lishan Mountain area in the main mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes, grass and sand integrated protection and restoration project area at the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi. However, there was a large area of NDVI decrease in the western part of the Qinling mountain front flood plain.

(4) The lag effects of precipitation and air temperature on monthly NDVI are both positive in a short period of time. Meanwhile, in spring and monthly scales, precipitation and air temperature have a positive correlation with vegetation growth in the study area, and the influence of air temperature is more significant.

The research results can provide scientific basis and decision-making reference for vegetation protection, soil and water conservation and ecological environment construction in the northern foothills of the Qinling Mountains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and Y.Z.; methodology, J.F.; software, Y.L.; validation, T.L., X.L. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, T.L.; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Data from satellite sensors and field work in the local teams are highly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, S.; Ming, B.; Huang, Q.; Leng, G.; Hou, B. A case study on a combination NDVI forecasting model based on the entropy weight method. Water Resources Management 2017, 31(11): 3667-3681.

- Wookey, P. A.; Aerts, R.; Bardgett, R. D.; Baptist, F.; Bråthen, K. A.; Cornelissen, J. H.; Gough, L.; Hartley, I. P.; Hopkins, D. W.; Lavorel, S.; Shaver, G. R. Ecosystem feedbacks and cascade processes: understanding their role in the responses of Arctic and alpine ecosystems to environmental change. Global Change Biology 2010, 15(5): 1153-1172.

- Sulman, B. N.; Roman, D. T.; Yi, K.; Wang, L.; Phillips, R. P.; Novick, K. A. High atmospheric demand for water can limit forest carbon uptake and transpiration as severely as dry soil. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43(18): 9686-9695.

- Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Niu, Z.; Bukhosor; Li, B. Analysis of the vegetation cover change and the relationship between NDVI and environmental factors by using NOAA time series data. Journal of Remote Sensing 1998, 2(3): 204-210.

- Peng, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Han, Y. Trend analysis of vegetation dynamics in Qinghai–Tibet Plateau using Hurst Exponent. Ecological Indicators 2012, 14(1): 28-39.

- Yu, D. RS time series analysis of vegetation dynamics and ecological security assessment in Weihe Watershed. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, May 2019.

- Kattimani J M, Prasad T J R. Normalised differenciative vegetation index (NDVI) analysis in south-east dry agro-climatic zones of Karnataka using RS and GIS techniques. International Journal of Advanced Research 2016, 4: 1952-1957.

- Yang, L.; Guan, Q.; Lin, J.; Tian, J.; Tan, Z.; Li, H. Evolution of NDVI secular trends and responses to climate change: A perspective from nonlinearity and nonstationarity characteristics. Remote Sensing of Environment 2021, 254: 112247.

- Camps-Valls, G.; Campos-Taberner, M.; Moreno-Martínez, Á.; Walther, S.; Duveiller, G.; Cescatti, A.; Mahecha, M. D.; Munoz-Mari, J.; Garcia-Haro, F. J.; Guanter, L.; Jung, M.; Gamon, J. A.; Reichstem M.; Running, S. W. A unified vegetation index for quantifying the terrestrial biosphere. Science Advances 2021, 7(9): eabc7447.

- Chen, S.; He, L.; Yan, F. Spatiotemporal evolution of vegetation coverage in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and its response to natural anthropogenic changes. China Environmental Science 2024: 1-19.

- Lin, X.; Niu, J.; Berndtsson, R.; Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. NDVI dynamics and its response to climate change and reforestation in northern China. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(24): 4138.

- Vannoppen A, Gobin A. Estimating farm wheat yields from NDVI and meteorological data. Agronomy 2021, 11(5): 946.

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Y.; Li, S.; Wen, Y.; Yu, W. Verification and analysis of high spatial-temporal resolution vegetation index product based on GF-1 satellite data. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2023, 27(3): 665-676.

- Sajadi, P.; Sang, Y. F.; Gholamnia, M.; Bonafoni, S.; Brocca, L.; Pradhan, B.; Singh, A. Performance evaluation of long NDVI timeseries from AVHRR, MODIS and landsat sensors over landslide-prone locations in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(16): 3172.

- Li, S.; Ye, Z.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, N. Comparison of four fusion models for generating high spatio-temporal resolution NDVI. Journal of Zhejiang A&F University 2023, 40(2): 427-435.

- Boyte, S. P.; Wylie, B. K.; Rigge, M. B.; Dahal, D. Fusing MODIS with Landsat 8 data to downscale weekly normalized difference vegetation index estimates for central Great Basin rangelands, USA. GIScience & remote sensing 2018, 55(3): 376-399.

- Zhou, Z.; Ding, Y.; Shi, H.; Cai, H.; Fu, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, T. Analysis and prediction of vegetation dynamic changes in China: Past, present and future. Ecological Indicators 2020, 117: 106642.

- Li, M.; Han, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y. Analysis on spatial-temporal variation characteristics and driving factors of fractional vegetation cover in Ningxia based on geographical detector. Ecology And Environmental Sciences 2022, 31(7): 1317-1325.

- Zheng, K.; Tan, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Duan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gao, C. Impacts of climate change and anthropogenic activities on vegetation change: Evidence from typical areas in China. Ecological indicators 2021, 126: 107648.

- Matsushita, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Onda, Y.; Qiu, G. Sensitivity of the enhanced vegetation index (EVI) and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) to topographic effects: a case study in high-density cypress forest. Sensors 2007, 7(11): 2636-2651.

- Chen, R.; Yin, G.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Verger, A. Evaluation and normalization of topographic effects on vegetation indices. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(14): 2290.

- Nie, T.; Dong, G.; Jiang, X.; Lei, Y. Spatio-temporal changes and driving forces of vegetation coverage on the loess plateau of Northern Shaanxi. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(4): 613.

- Guo, E.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, Z.; Bao, Y.; Mandula, N.; Jirigala, B.; Bao, Y.; Li, H. NDVI indicates long-term dynamics of vegetation and its driving forces from climatic and anthropogenic factors in Mongolian Plateau. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(4): 688.

- Wu, C.; Xu, F.; Wei, S.; Fan, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, K. Study on response of surface vegetation cover to climate change in Weihe River Basin. Ecology and Environmental Sciences 2023, 32(5): 835-844.

- Ma, N.; Bai, T.; Cai, C. Vegetation cover change and its response to climate and surface factors in Xinjiang based on different vegetation types. Research of Soil and Water Conservation 2024, 31(1): 385-394.

- Kang, M.; Zhu, Y. Discussion and analysis on the geo-ecological boundary in Qinling Range. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2007, 27(7): 2774-2784.

- Zhao, T.; Bai, H.; Li, J.; Ma, Q.; Wang, P. Changes of vegetation potential distribution pattern in the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi Province in the context of climate warming. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2023, 43(5): 1843-1852.

- Zhao, T.; Bai, H.; Yuan, Y.; Deng, C.; Qi, G.; Zhai, D. Spatio-temporal differentiation of climate warming (1959–2016) in the middle Qinling Mountains of China. Journal of Geographical Sciences 2020, 30: 657-668.

- Gao J. Impact of land use change on soil nitrogen accumulation and loss in the northern slope region of Qinling Mountains. Doctor’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China, November 2020.

- Wang, B.; Xu, G.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Jia, L.; Zhang, J. Vegetation dynamics and their relationships with climatic factors in the Qinling Mountains of China. Ecological Indicators 2020, 108: 105719.

- Wang, L.; Yu, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Study on Tempo-spatial variations of NDVI and climatic factors and their correlation in the Weihe Watershed. Research of Soil and Water Conservation 2019, 26(02): 249-254.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Xie, S.; Mi, J. GLC_FCS30: Global land-cover product with fine classification system at 30 m using time-series Landsat imagery. Earth System Science Data 2021, 13(6): 2753-2776.

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Wen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Ren, J. Spatiotemporal change and trend analysis of potential evapotranspiration over the Loess Plateau of China during 2011-2100. Agricultural and forest meteorology 2017, 233: 183-194.

- Peng, S.; Gang, C.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y. Assessment of climate change trends over the Loess Plateau in China from 1901 to 2100. International Journal of Climatology 2018, 38(5): 2250-2264.

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth System Science Data 2019, 11(4): 1931-1946.

- Ding Y, Peng S. Spatiotemporal trends and attribution of drought across China from 1901-2100. Sustainability 2020, 12(2): 477.

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J. P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A commentary review on the use of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the era of popular remote sensing. Journal of Forestry Research 2021, 32(1), 1-6.

- Robinson, N. P.; Allred, B. W.; Jones, M. O.; Moreno, A.; Kimball, J. S.; Naugle, D. E.; Erickson, T. A.; Richardson, A. D. A dynamic Landsat derived normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) product for the conterminous United States. Remote sensing 2017, 9(8), 863.

- Wang, F.; Ge, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Jones, P. D. A new estimation of urbanization’s contribution to the warming trend in China. Journal of Climate 2015, 28(22): 8923-8938.

- Zhang, J.; Bai, J.; Yu, Q. Temporal and spatial dynamic monitoring of spring drought in Guanzhong region based on TVDI model. Journal of Lanzhou University(Natural Sciences) 2017, 53(6): 1-8.

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Bai, X.; Tan, Q.; Li, Q.; Wu, L.; Tian, S.; Hu, Z.; Li, C.; Deng, Y. Factors affecting long-term trends in global NDVI. Forests 2019, 10(5): 372.

- Jin, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, R.; Zhao, T.; Liu, Z.; Tu, X. Spatio-temporal distribution of NDVI and its influencing factors in China. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 603: 127129.

- Liu, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, R.; Ding, L. Influences of climate change and human activities on NDVI changes in China. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(21): 4326.

- Jobbágy E G, Sala O E, Paruelo J M. Patterns and controls of primary production in the Patagonian steppe: a remote sensing approach. Ecology 2002, 83(2): 307-319.

- Niu, J.; Chen, J.; Sun, L.; Sivakumar, B. Time-lag effects of vegetation responses to soil moisture evolution: a case study in the Xijiang basin in South China. Stochastic environmental research and risk assessment 2018, 32: 2423-2432.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).