Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

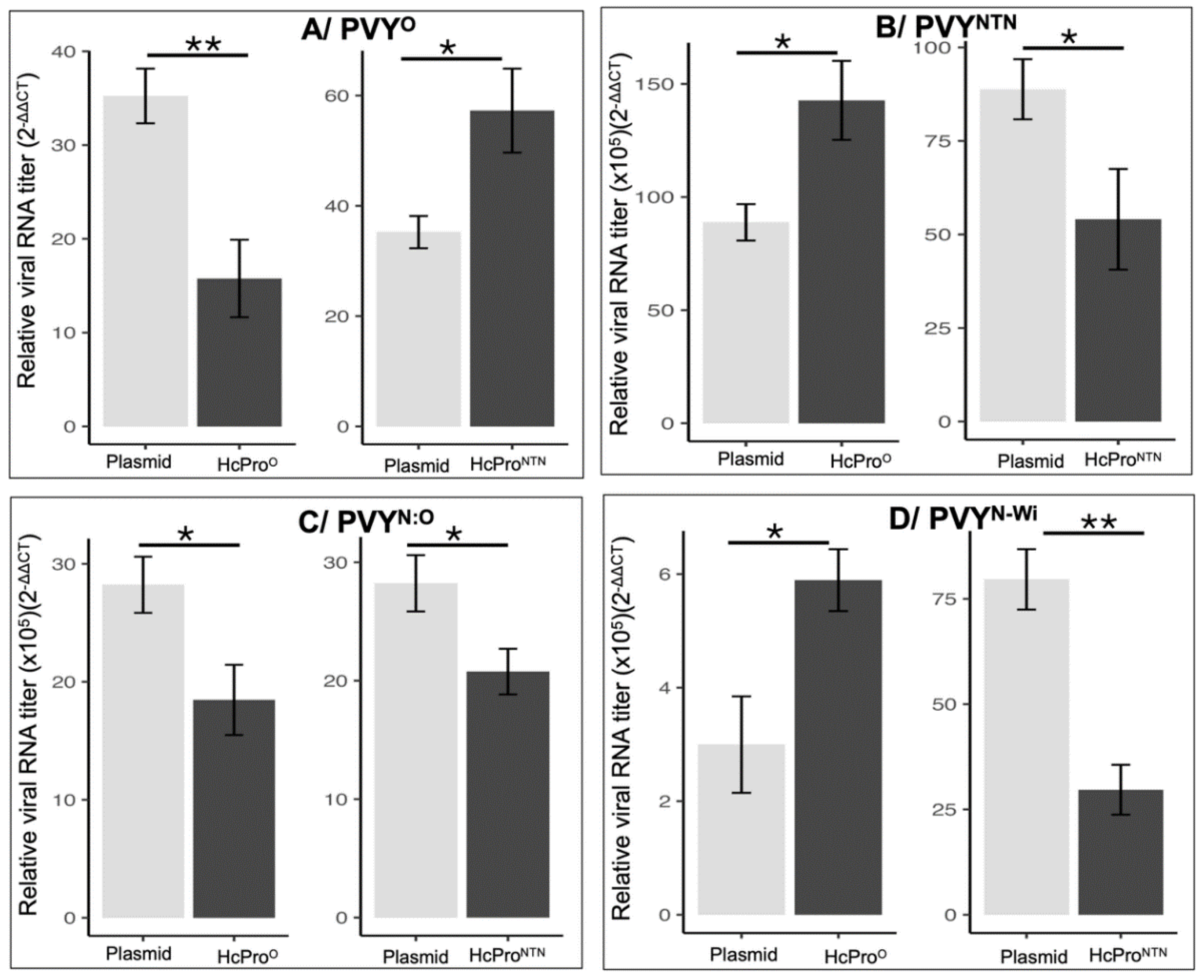

2.1. HcPro Induces SIE in a Sequence Specific Manner

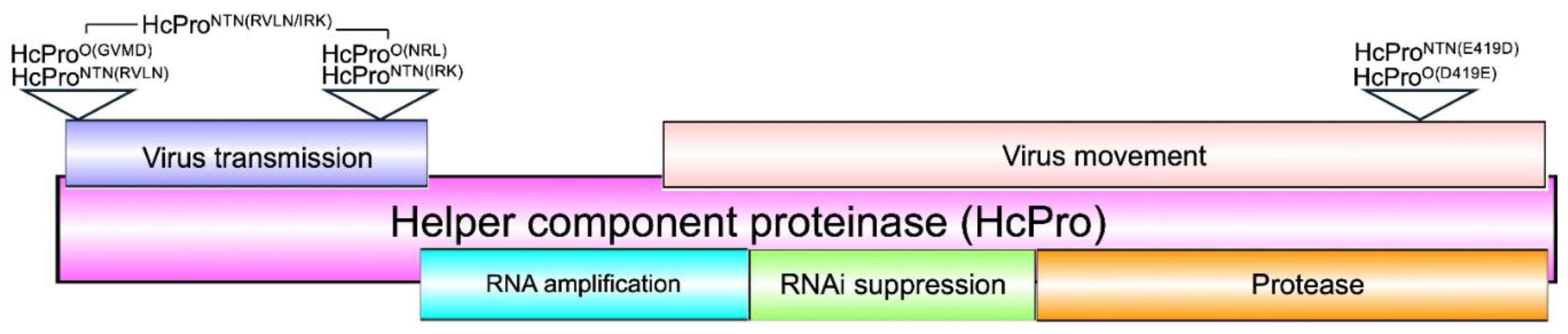

2.2. The Four N-Terminal Amino Acid Residues Provide Specificity of HcPro Induction of SIE

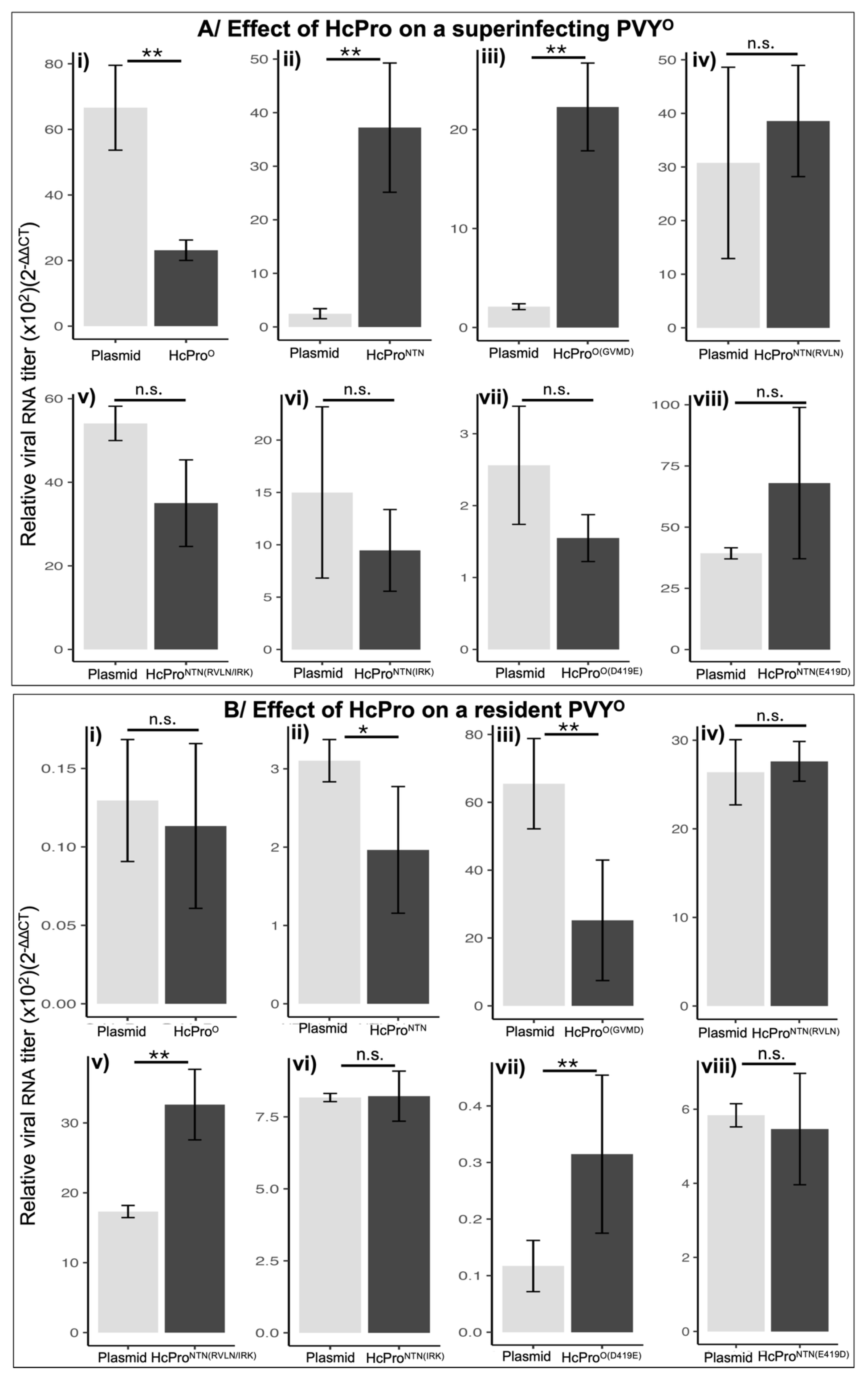

2.2.1. Characterization of HcPro Induction of PVYO SIE

2.2.2. HcProO Does not Induce Exclusion of PVYO

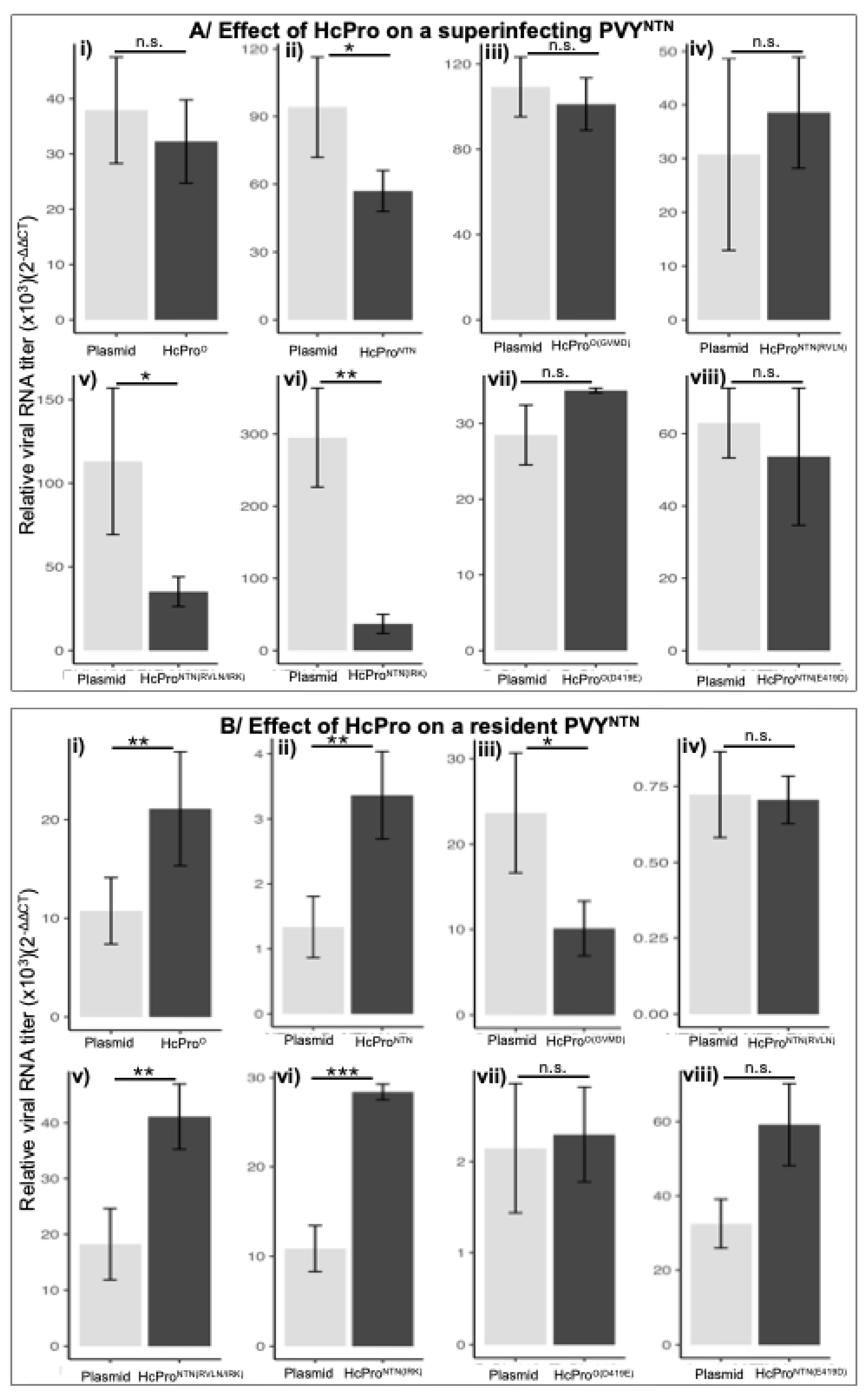

2.2.3. HcProNTN Induction of PVYNTN SIE

2.2.4. The Superinfecting HcPro Does not Induce Exclusion of a Resident PVYNTN

2.2.5. Subcellular Localization Does not Influence Behavior of HcPro Mutants

2.3. HcPro Induction of SIE and RNA Silencing Suppression Are Regulated Through Distinct Mechanisms

2.3.1. HcPro Suppression of PTGS

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plasmid Construction and Inoculations

4.2. Isolation of RNA and Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.3. Determination of Relative Viral RNA Levels

4.4. Western Blot Analysis

4.5. Confocal Microscopy

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, R.P.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Gray, S.M.; Boonham, N.; Jones, R. a. C.; Kerlan, C.; Schubert, J. Discussion Paper: The Naming of Potato Virus Y Strains Infecting Potato. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Karasev, A.V.; Brown, C.J.; Lorenzen, J.H. Sequence Characteristics of Potato Virus Y Recombinants. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 3033–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, J.S.; Gray, S.M.; Karasev, A. V. Screening Potato Cultivars for New Sources of Resistance to Potato Virus Y. Am. J. Potato Res. 2014 921 2015, 92, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenouille, J.; Vassilakos, N.; Moury, B. Potato Virus Y: A Major Crop Pathogen That Has Provided Major Insights into the Evolution of Viral Pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merits, A.; Rajamäki, M.-L.; Lindholm, P.; Runeberg-Roos, P.; Kekarainen, T.; Puustinen, P.; Mäkeläinen, K.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Saarma, M. Proteolytic Processing of Potyviral Proteins and Polyprotein Processing Intermediates in Insect and Plant Cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.Y.-W.; Miller, W.A.; Atkins, J.F.; Firth, A.E. An Overlapping Essential Gene in the Potyviridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 5897–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revers, F.; García, J.A. Molecular Biology of Potyviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2015, 92, 101–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcuqui-Inchima, S.; Haenni, A.-L.; Bernardi, F. Potyvirus Proteins: A Wealth of Functions. Virus Res. 2001, 74, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozieł, E.; Surowiecki, P.; Przewodowska, A.; Bujarski, J.J.; Otulak-Kozieł, K. Modulation of Expression of PVYNTN RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (NIb) and Heat Shock Cognate Host Protein HSC70 in Susceptible and Hypersensitive Potato Cultivars. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olspert, A.; Chung, B.Y.-W.; Atkins, J.F.; Carr, J.P.; Firth, A.E. Transcriptional Slippage in the Positive-Sense RNA Virus Family Potyviridae. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodamilans, B.; Valli, A.; Mingot, A.; San León, D.; Baulcombe, D.; López-Moya, J.J.; García, J.A. RNA Polymerase Slippage as a Mechanism for the Production of Frameshift Gene Products in Plant Viruses of the Potyviridae Family. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 6965–6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Luan, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, A.; Cheng, X. P3N-PIPO Interacts with P3 via the Shared N-Terminal Domain To Recruit Viral Replication Vesicles for Cell-to-Cell Movement. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01898-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, J.C.; Herndon, K.L. Characterization of the Potyviral HC-pro Autoproteolytic Cleavage Site. Virology 1992, 187, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchot, J.; Herndon, K.L.; Carrington, J.C. Mutational Analysis of the Tobacco Etch Potyviral 35-kDa Proteinase: Identification of Essential Residues and Requirements for Autoproteolysis. Virology 1992, 190, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandalakshmi, R.; Pruss, G.J.; Ge, X.; Marathe, R.; Mallory, A.C.; Smith, T.H.; Vance, V.B. A Viral Suppressor of Gene Silencing in Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 13079–13084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasschau, K.D.; Carrington, J.C. A Counterdefensive Strategy of Plant Viruses: Suppression of Posttranscriptional Gene Silencing. Cell 1998, 95, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruss, G.; Ge, X.; Shi, X.M.; Carrington, J.C.; Bowman Vance, V. Plant Viral Synergism: The Potyviral Genome Encodes a Broad-Range Pathogenicity Enhancer That Transactivates Replication of Heterologous Viruses. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, K.I.; Eskelin, K.; Bašić, M.; De, S.; Lõhmus, A.; Varjosalo, M.; Mäkinen, K. Molecular Insights into the Function of the Viral RNA Silencing Suppressor HCPro. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 85, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-F.; Wei, W.-L.; Hong, S.-F.; Fang, R.-Y.; Wu, H.-Y.; Lin, P.-C.; Sanobar, N.; Wang, H.-P.; Sulistio, M.; Wu, C.-T.; et al. Investigation of the Effects of P1 on HC-pro-Mediated Gene Silencing Suppression through Genetics and Omics Approaches. Bot. Stud. 2020, 61, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govier, D.A.; Kassanis, B.; Pirone, T.P. Partial Purification and Characterization of the Potato Virus Y Helper Component. Virology 1977, 78, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Valli, A.; Calvo, M.; García, J.A. A Functional Link between RNA Replication and Virion Assembly in the Potyvirus Plum Pox Virus. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e02179-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, A.; Gallo, A.; Calvo, M.; Pérez, J. de J.; García, J.A. A Novel Role of the Potyviral Helper Component Proteinase Contributes To Enhance the Yield of Viral Particles. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 9808–9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kd, K.; S, C.; Jc, C. Genome Amplification and Long-Distance Movement Functions Associated with the Central Domain of Tobacco Etch Potyvirus Helper Component-Proteinase. Virology 1997, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.R.; Zerbini, F.M.; Allison, R.F.; Gilbertson, R.L.; Lucas, W.J. Capsid Protein and Helper Component-Proteinase Function as Potyvirus Cell-to-Cell Movement Proteins. Virology 1997, 237, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáenz, P.; Salvador, B.; Simón-Mateo, C.; Kasschau, K.D.; Carrington, J.C.; García, J.A. Host-Specific Involvement of the HC Protein in the Long-Distance Movement of Potyviruses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plisson, C.; Drucker, M.; Blanc, S.; German-Retana, S.; Le Gall, O.; Thomas, D.; Bron, P. Structural Characterization of HC-Pro, a Plant Virus Multifunctional Protein*. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 23753–23761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkonen, J.P.T.; Rajamäki, M.-L.; Kekarainen, T. Mapping of Viral Genomic Regions Important in Cross-Protection between Strains of a Potyvirus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2002, 15, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergua, M.; Zwart, M.P.; El-Mohtar, C.; Shilts, T.; Elena, S.F.; Folimonova, S.Y. A Viral Protein Mediates Superinfection Exclusion at the Whole-Organism Level but Is Not Required for Exclusion at the Cellular Level. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11327–11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folimonova, S.Y. Superinfection Exclusion Is an Active Virus-Controlled Function That Requires a Specific Viral Protein. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 5554–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folimonova, S.Y.; Harper, S.J.; Leonard, M.T.; Triplett, E.W.; Shilts, T. Superinfection Exclusion by Citrus Tristeza Virus Does Not Correlate with the Production of Viral Small RNAs. Virology 2014, 468–470, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S.; French, R. The Coat Protein and NIa Protease of Two Potyviridae Family Members Independently Confer Superinfection Exclusion. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10886–10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunna, H.; Qu, F.; Tatineni, S. P3 and NIa-Pro of Turnip Mosaic Virus Are Independent Elicitors of Superinfection Exclusion. Viruses 2023, 15, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardello, G.; Scuderi, G.; Russo, M.; Bazzano, M.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Catara, A.F. Minor Variants of Orf1a, P33, and P23 Genes of VT Strain Citrus Tristeza Virus Isolates Show Symptomless Reactions on Sour Orange and Prevent Superinfection of Severe VT Isolates. Viruses 2023, 15, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, K.; Zhou, X.; Jackson, A.O.; Li, Z. The Matrix Protein of a Plant Rhabdovirus Mediates Superinfection Exclusion by Inhibiting Viral Transcription. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00680-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, I.-C.; Li, W.; Sui, J.; Marasco, W.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. Influenza A Virus Neuraminidase Limits Viral Superinfection. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4834–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Tscherne, D.M.; Yun, S.-I.; Frolov, I.; Rice, C.M. Dual Mechanisms of Pestiviral Superinfection Exclusion at Entry and RNA Replication. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 3231–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.K.; Fitzpatrick, A.D.; Schwartzkopf, C.M.; Faith, D.R.; Jennings, L.K.; Coluccio, A.; Hunt, D.J.; Michaels, L.A.; Hargil, A.; Chen, Q.; et al. A Filamentous Bacteriophage Protein Inhibits Type IV Pili To Prevent Superinfection of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. mBio 2022, e0244121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Q.; Sun, R.; Wei, T.; Qu, F. A New Mechanistic Model for Viral Cross Protection and Superinfection Exclusion. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Meng, F.; Nie, X.; Bai, Y. Potato Virus Y Strain N-Wi Offers Cross-Protection in Potato Against Strain NTN-NW by Superior Competition. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, C.; Yuan, X. A New Strategy of Cross-Protection Based on Attenuated Vaccines: RNA Viruses Are Used as Vectors to Control DNA Viruses. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, Y.; Aranda, M.A. Cross-Protection against Pepino Mosaic Virus, More than a Decade of Efficient Disease Control. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2024, 184, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, H.; Chavan, D.D.; Meena, V.K.; Kashyap, A.S.; Sathiyaseelan, K.; Elangovan, M.; Patil, L.; Meena, B.R.; Gauns, A.; Bhattacharyya, U.K.; et al. Differentiation and Validation of Mild and Severe Strains of Citrus Tristeza Virus through Codon Usage Bias, Host Adaptation, and Biochemical Profiling. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardello, G.; Scuderi, G.; Russo, M.; Bazzano, M.; Paradiso, G.; Bar-Joseph, M.; Catara, A.F. Progress in Our Understanding of the Cross-Protection Mechanism of CTV-VT No-SY Isolates Against Homologous SY Isolates. Pathogens 2025, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozzo, F.; Faoro, F. Systemic Acquired Resistance (50 Years after Discovery): Moving from the Lab to the Field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12473–12491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, E.; Mulugeta, T.; Lankinen, Å.; Liljeroth, E.; Andreasson, E. Plant Resistance Inducers against Pathogens in Solanaceae Species—From Molecular Mechanisms to Field Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glais, L.; Faurez, F.; Tribodet, M.; Boulard, F.; Jacquot, E. The Amino Acid 419 in HC-Pro Is Involved in the Ability of PVY Isolate N605 to Induce Necrotic Symptoms on Potato Tubers. Virus Res. 2015, 208, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinnet, O.; Vain, P.; Angell, S.; Baulcombe, D.C. Systemic Spread of Sequence-Specific Transgene RNA Degradation in Plants Is Initiated by Localized Introduction of Ectopic Promoterless DNA. Cell 1998, 95, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondong, V.N.; Reddy, R.V.C.; Lu, C.; Hankoua, B.; Felton, C.; Czymmek, K.; Achenjang, F. The Consensus N-Myristoylation Motif of a Geminivirus AC4 Protein Is Required for Membrane Binding and Pathogenicity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. MPMI 2007, 20, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowda-Reddy, R.V.; Achenjang, F.; Felton, C.; Etarock, M.T.; Anangfac, M.-T.; Nugent, P.; Fondong, V.N. Role of a Geminivirus AV2 Protein Putative Protein Kinase C Motif on Subcellular Localization and Pathogenicity. Virus Res. 2008, 135, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowda-Reddy, R.V.; Dong, W.; Felton, C.; Ryman, D.; Ballard, K.; Fondong, V.N. Characterization of the Cassava Geminivirus Transcription Activation Protein Putative Nuclear Localization Signal. Virus Res. 2009, 145, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Sun, R.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, S.; Meulia, T.; Halfmann, R.; Li, D.; Qu, F. A Self-Perpetuating Repressive State of a Viral Replication Protein Blocks Superinfection by the Same Virus. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syller, J. Facilitative and Antagonistic Interactions between Plant Viruses in Mixed Infections. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syller, J.; Grupa, A. Antagonistic Within-Host Interactions between Plant Viruses: Molecular Basis and Impact on Viral and Host Fitness. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.; Maiss, E. Fluorescent Labelling Reveals Spatial Separation of Potyvirus Populations in Mixed Infected Nicotiana Benthamiana Plants. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2871–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondong, V.N.; Pita, J.S.; Rey, M.E.C.; De Kochko, A.; Beachy, R.N.; Fauquet, C.M. Evidence of Synergism between African Cassava Mosaic Virus and a New Double-Recombinant Geminivirus Infecting Cassava in Cameroon. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Lin, Y.-H.; Carroll, J.E.; Wenninger, E.J.; Bosque-Pérez, N.A.; Whitworth, J.L.; Hutchinson, P.; Eigenbrode, S.; Gray, S.M. Potato Virus Y Transmission Efficiency from Potato Infected with Single or Multiple Virus Strains. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M.; Fusco, D. Superinfection Exclusion: A Viral Strategy with Short-Term Benefits and Long-Term Drawbacks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatineni, S.; Riethoven, J.-J.M.; Graybosch, R.A.; French, R.; Mitra, A. Dynamics of Small RNA Profiles of Virus and Host Origin in Wheat Cultivars Synergistically Infected by Wheat Streak Mosaic Virus and Triticum Mosaic Virus: Virus Infection Caused a Drastic Shift in the Endogenous Small RNA Profile. PloS One 2014, 9, e111577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, T.; Rush, C.M. Evidence of Cross-Protection Between Beet Soilborne Mosaic Virus and Beet Necrotic Yellow Vein Virus in Sugar Beet. Plant Dis. 1999, 83, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazono-Nagaoka, E.; Takahashi, T.; Shimizu, T.; Kosaka, Y.; Natsuaki, T.; Omura, T.; Sasaya, T. Cross-Protection Against Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus (BYMV) and Clover Yellow Vein Virus by Attenuated BYMV Isolate M11. Phytopathology® 2009, 99, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.V.C.; Dong, W.; Njock, T.; Rey, M.E.C.; Fondong, V.N. Molecular Interaction between Two Cassava Geminiviruses Exhibiting Cross-Protection. Virus Res. 2012, 163, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameyaw, G.A.; Domfeh, O.; Dzahini-Obiatey, H.; Ollennu, L. a. A.; Owusu, G.K. Appraisal of Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus (CSSV) Mild Isolates for Cross Protection of Cocoa Against Severe Strains in Ghana. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinney, H.H. Mosaic Diseases in the Canary Islands, West Africa, and Gibraltar. 1929, 557-578.

- Cheng, X.; Wang, A. The Potyvirus Silencing Suppressor Protein VPg Mediates Degradation of SGS3 via Ubiquitination and Autophagy Pathways. J. Virol. 2016, 91, e01478-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fondong, V.N.; Rey, C.; Fondong, V.N.; Rey, C. Recent Biotechnological Advances in the Improvement of Cassava; IntechOpen, 2018; ISBN 978-953-51-3741-2.

- Giudice, G.; Moffa, L.; Varotto, S.; Cardone, M.F.; Bergamini, C.; De Lorenzis, G.; Velasco, R.; Nerva, L.; Chitarra, W. Novel and Emerging Biotechnological Crop Protection Approaches. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1495–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, P.M.; Fondong, V.N. Development and Adoption of Genetically Engineered Plants for Virus Resistance: Advances, Opportunities and Challenges. Plants Basel Switz. 2021, 10, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitmayer, C.M.; Levitt, E.; Basu, S.; Atkinson, B.; Fragkoudis, R.; Merits, A.; Lumley, S.; Larner, W.; Diaz, A.V.; Rooney, S.; et al. Mimicking Superinfection Exclusion Disrupts Alphavirus Infection and Transmission in the Yellow Fever Mosquito Aedes Aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2303080120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Randolph, P.B.; Davis, J.R.; Sousa, A.A.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Chen, P.J.; Wilson, C.; Newby, G.A.; Raguram, A.; et al. Search-and-Replace Genome Editing without Double-Strand Breaks or Donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, K.W.; Haag, J.R.; Pontes, O.; Opper, K.; Juehne, T.; Song, K.; Pikaard, C.S. Gateway-Compatible Vectors for Plant Functional Genomics and Proteomics. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 45, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, D.; Glazebrook, J. Transformation of Agrobacterium Using the Freeze-Thaw Method. CSH Protoc. 2006, 2006, pdb.prot4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niraula, P.M.; Baldrich, P.; Cheema, J.A.; Cheema, H.A.; Gaiter, D.S.; Meyers, B.C.; Fondong, V.N. Antagonism and Synergism Characterize the Interactions between Four North American Potato Virus Y Strains. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, J.; Pingoud, A.; Hahn, M. Validation of an Algorithm for Automatic Quantification of Nucleic Acid Copy Numbers by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Anal. Biochem. 2003, 317, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Fusco, D. Superinfection Exclusion: A Viral Strategy with Short-Term Benefits and Long-Term Drawbacks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Designation | Sequence | Construct |

|---|---|---|

|

NTN.Hc-Pro.F NTN.Hc-Pro.R |

attB1+GGGGTTATGGATTCA | HcProNTN |

| attB2+ ACCAACTCTATAGTGCTTAATGTCAGACT | ||

|

O.HcPro.F O.HcPro-Pro.R |

attB1+CGTGTTTTGAACTCAA | HcProO |

| attB2+ACCAACTCTATAATGTTTTATATCAGATTCTAATTCATCATTTGC | ||

|

GVMD(1-4)RVLN-F GVMD(1-4)RVLN-R |

TTGAACTCAATGGTTCAGTTCTCAAGC | HcProNTN(RVLN) |

| AACACGGGCCATAAGGGCGAATTC | ||

|

RVLN(1-4)GVMD -F RVLN(1-4)GVMD-R |

ATGGATTCAATGATCCAGTTTTCGAATG | HcProO(GVMD |

| AACCCCGGCCATTAAGCCTGCTTT | ||

|

NRL(246-248)IRK-F NRL(246-248)IRK-R |

CAAGCATCCGAATGGAACAAGAAAAC | HcProNTN(IRK) |

| CGGATTTCATATGCTGAATAGCC | ||

| GVMD(1-4)RVLN-F | TTGAACTCAATGGTTCAGTTCTCAAGC | HcProNTN(RVLN/IRL)* |

| GVMD(1-4)RVLN-R | AACACGGGCCATAAGGGCGAATTC | |

|

OHcProGlu419-F OHcProGlu419-R |

TTGACCATGAAACTCAAACGTG | HcProO(D419E) |

| CCAATATTCTAGGCAGTTC | ||

|

NTNHcProAsp-F NTNHcProAsp-R |

TCGATCACGACACGCAGACAT | HcProNTN(E419D) |

| CTAGTATTCTAGGCAGTTCTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).