Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Model Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

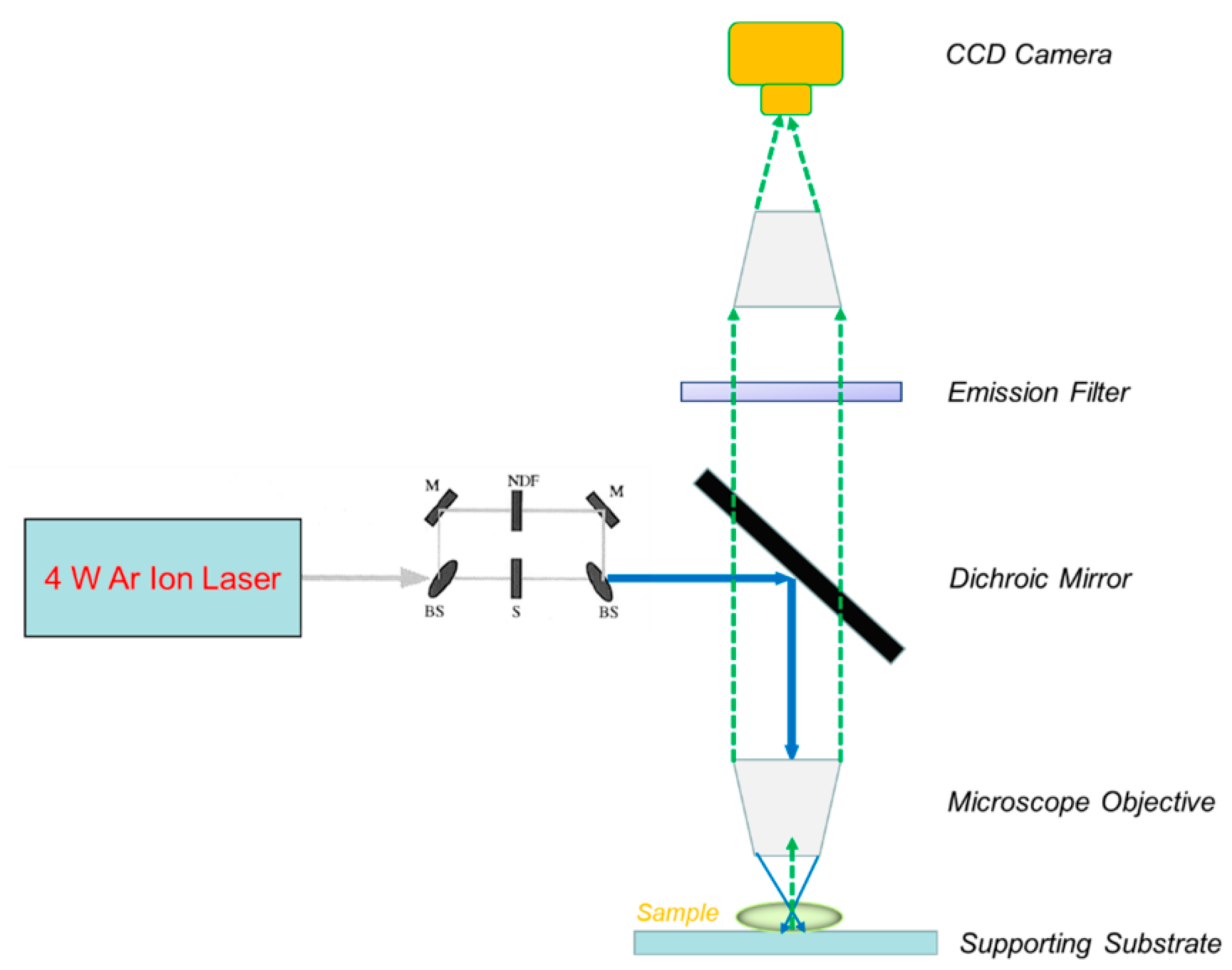

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Analytical Formulas

2.5. Experimental Conditions and Reproducibility

3. Results and Discussion

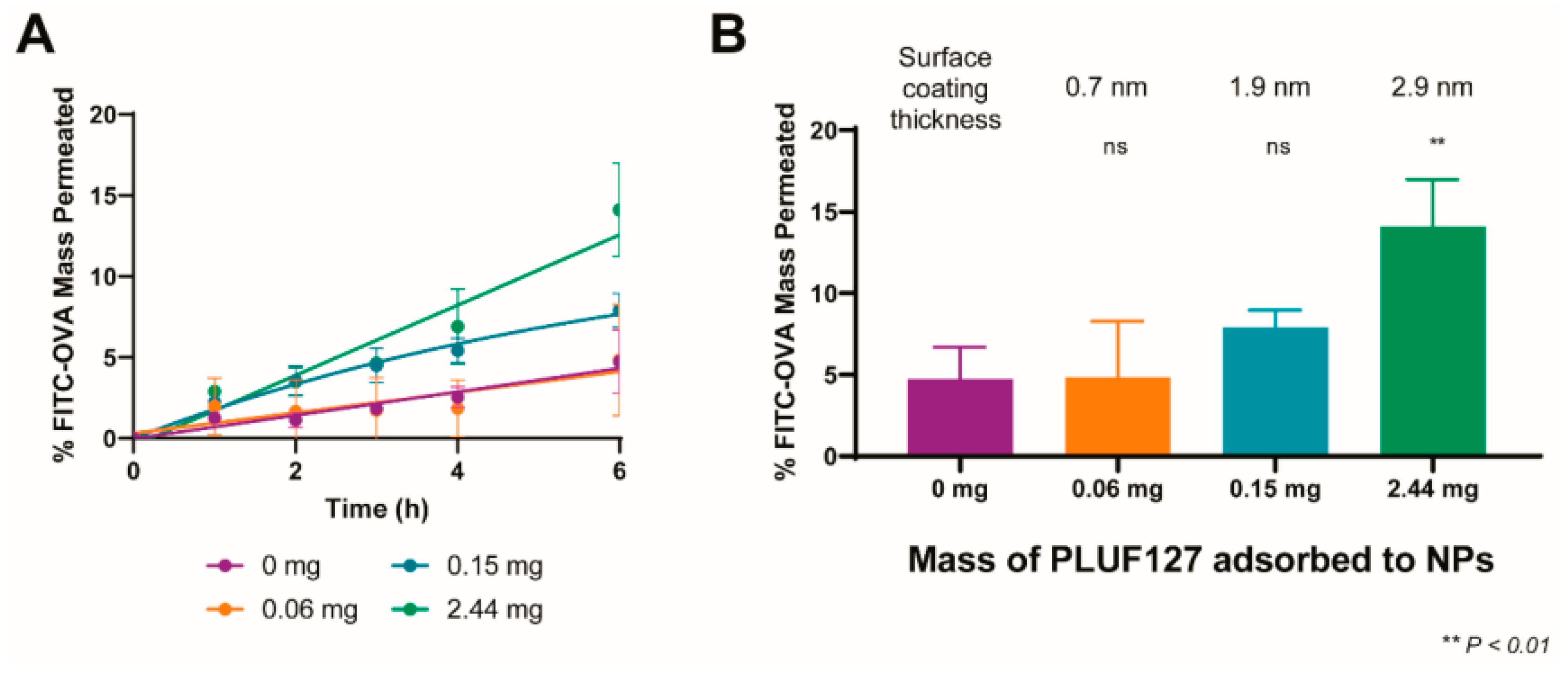

3.1. Effect of PEG Chain Length on Nanoparticle Diffusion

3.2. Mucus Penetration and Cellular Delivery

3.3. FRAP Validation and Consistency Across Methods

3.4. Comparison with Previous Studies and Practical Significance

4. Conclusion

References

- Abrami, M., Biasin, A., Tescione, F., Tierno, D., Dapas, B., Carbone, A., ... & Grassi, M. (2024). Mucus structure, viscoelastic properties, and composition in chronic respiratory diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(3), 1933.

- Zha, D. , Gamez, J., Ebrahimi, S. M., Wang, Y., Verma, N., Poe, A. J.,... & Saghizadeh, M. (2025). Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia, 1-16.

- Costa, M. P. , Abdu, J. O. C., de Moura, M. F. C. S., Silva, A. C., Zacaron, T. M., de Paiva, M. R. B.,... & Tavares, G. D. (2025). Exploring the Potential of PLGA Nanoparticles for Enhancing Pulmonary Drug Delivery. Molecular Pharmaceutics.

- Omidian, H. , & Wilson, R. L. (2025). PLGA-Based Strategies for Intranasal and Pulmonary Applications. Pharmaceutics, 17(2), 207.

- Tafech, B. , Rokhforouz, M. R., Leung, J., Sung, M. M., Lin, P. J., Sin, D. D.,... & Hedtrich, S. (2024). Exploring Mechanisms of Lipid Nanoparticle-Mucus Interactions in Healthy and Cystic Fibrosis Conditions. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 13(18), 2304525.

- Chen, D., Liu, J., Wu, J., & Suk, J. S. (2021). Enhancing nanoparticle penetration through airway mucus to improve drug delivery efficacy in the lung. Expert opinion on drug delivery, 18(5), 595-606.

- Xu, J. (2025). Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems.

- Ho, K. W. , Liu, Y. L., Liao, T. Y., Liu, E. S., & Cheng, T. L. (2024). Strategies for non-covalent attachment of antibodies to PEGylated nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 10045-10064.

- Tjakra, M. , Chakrapeesirisuk, N., Jacobson, M., Sellin, M. E., Eriksson, J., Teleki, A., & Bergström, C. A. (2025). Optimized Artificial Colonic Mucus Enabling Physiologically Relevant Diffusion Studies of Drugs, Particles, and Delivery Systems. Molecular Pharmaceutics.

- Wang, Y. , Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., & Cai, H. (2025). Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management.

- Ali, T. (2025). Nanomedicine Approaches to Overcome Barriers in Pulmonary Drug Delivery for Respiratory Diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Research, 30-44.

- Wen, Y. , Wu, X., Wang, L., Cai, H., & Wang, Y. (2025). Application of Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Drug Delivery in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Diseases. Journal of Medicine and Life Sciences, 1(2), 63-69.

- Zha, D. , Mahmood, N., Kellar, R. S., Gluck, J. M., & King, M. W. (2025). Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering.

- Tafech, B. , Rokhforouz, M. R., Leung, J., Sung, M. M., Lin, P. J., Sin, D. D.,... & Hedtrich, S. (2024). Exploring Mechanisms of Lipid Nanoparticle-Mucus Interactions in Healthy and Cystic Fibrosis Conditions. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 13(18), 2304525.

- Semitela, A. , Marques, P. A., & Completo, A. (2024). Strategies to engineer articular cartilage with biomimetic zonal features: a review. Biomaterials Science, 12(23), 5961-6005.

- Xu, K., Lu, Y., Hou, S., Liu, K., Du, Y., Huang, M., ... & Sun, X. (2024). Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications, 15(1), 8223.

- Tsukamoto, Y. , Kawamura, A., Yurtsever, A., Suzuki, H., Rojas-Chaverra, N. M., Sato, H.,... & Sakai, K. (2025). Condensation-dependent interactome of a chromatin remodeler underlies tumor suppressor activities. Nature Communications, 16(1), 9599.

- Dash, P. K. , Chen, C., Kaminski, R., Su, H., Mancuso, P., Sillman, B.,... & Khalili, K. (2023). CRISPR editing of CCR5 and HIV-1 facilitates viral elimination in antiretroviral drug-suppressed virus-infected humanized mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(19), e2217887120.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).