Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of the Independent-Samples t-Test

2.1. Studying the Difference Between Two Independent Groups

2.2. Null and Alternative Hypotheses

2.3. Effect Sizes

2.4. Sample Size and (un)Balanced Designs

3. Study Designs

4. Methodological Steps

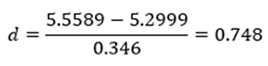

5. Data Setup and Example

5.1. Example Used in This Guide

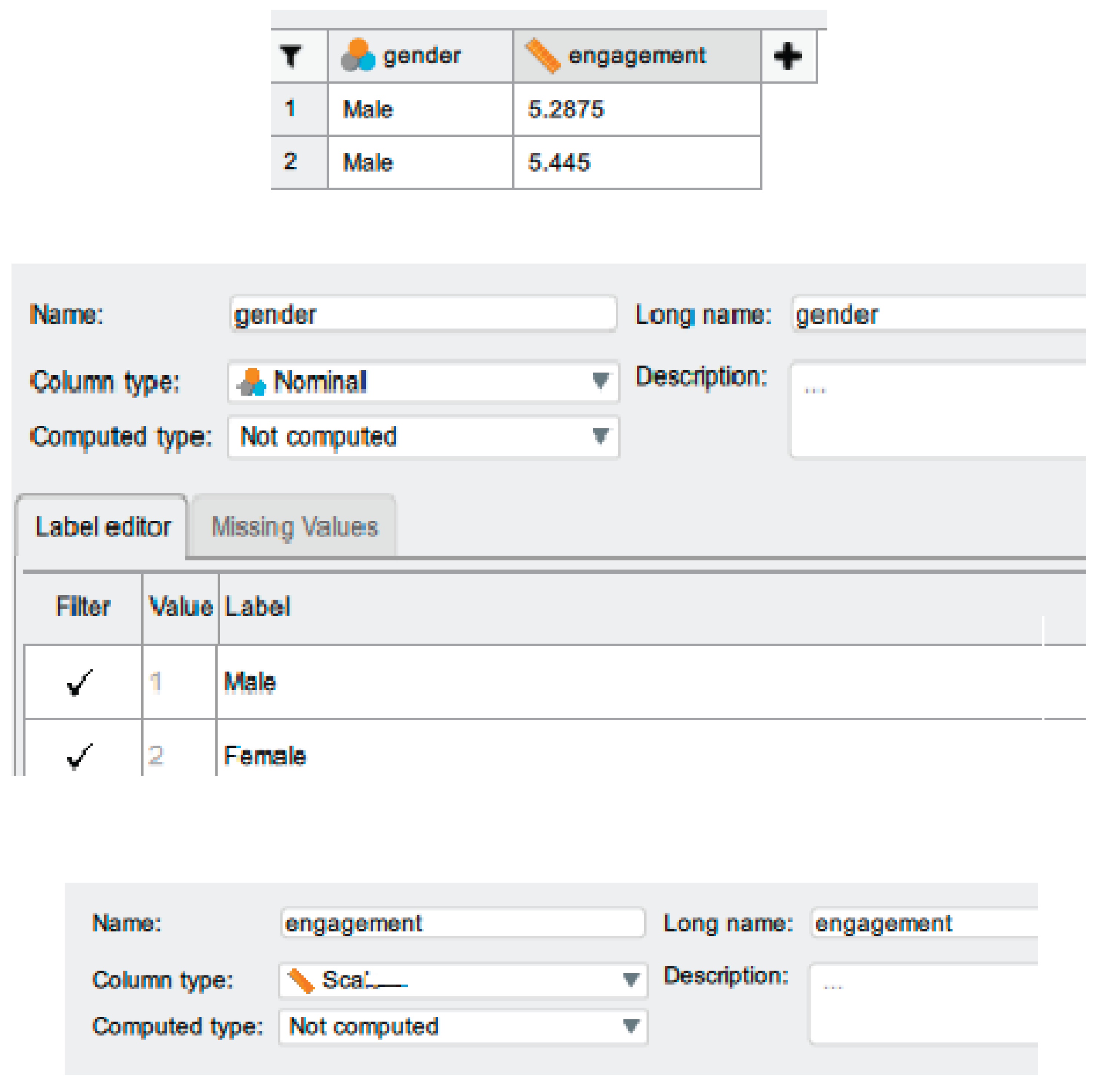

5.2. Setting Up the Data

5.3. Null and Alternative Hypotheses

6. Assumptions and Prerequisites

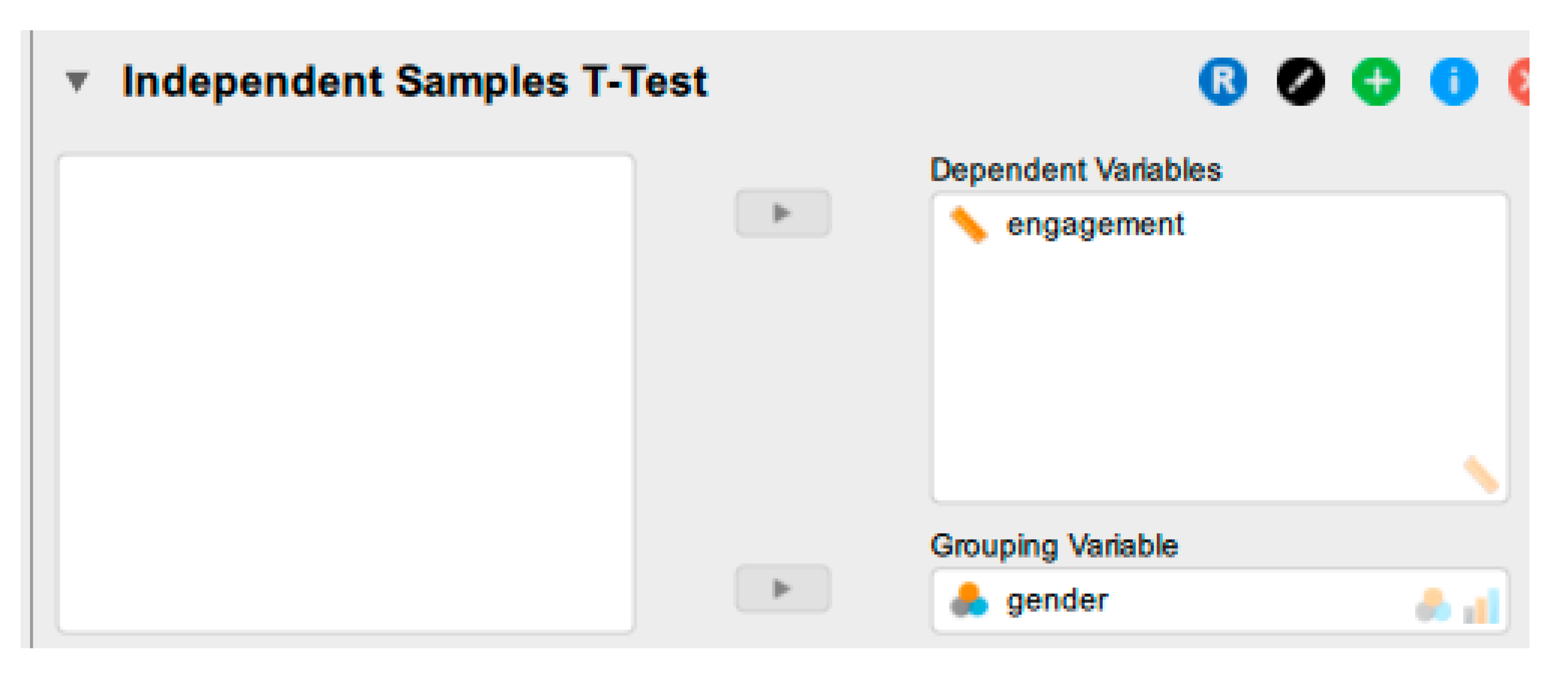

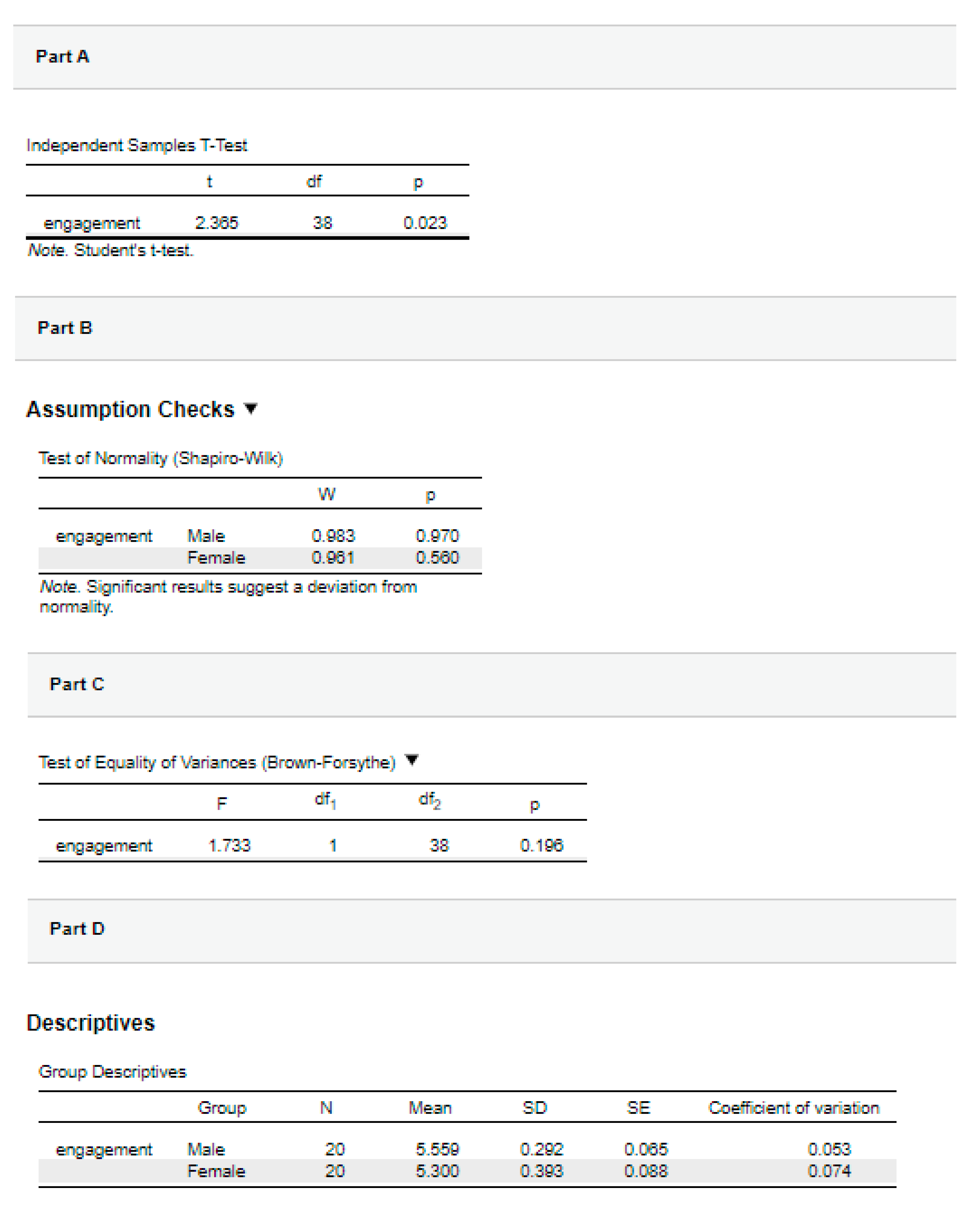

7. Running the Test

8. Interpreting the Output

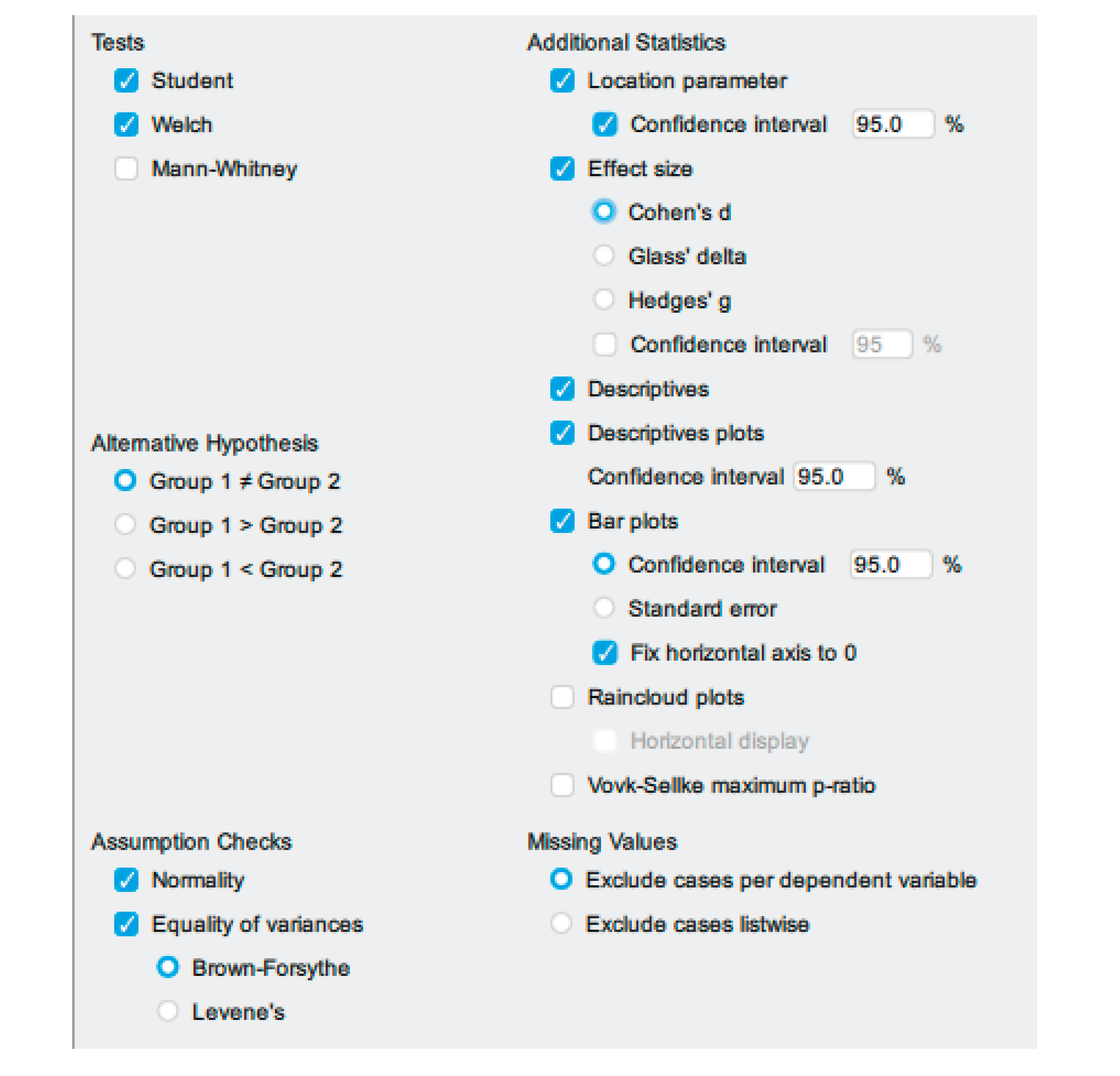

8.1. Descriptive Statistics

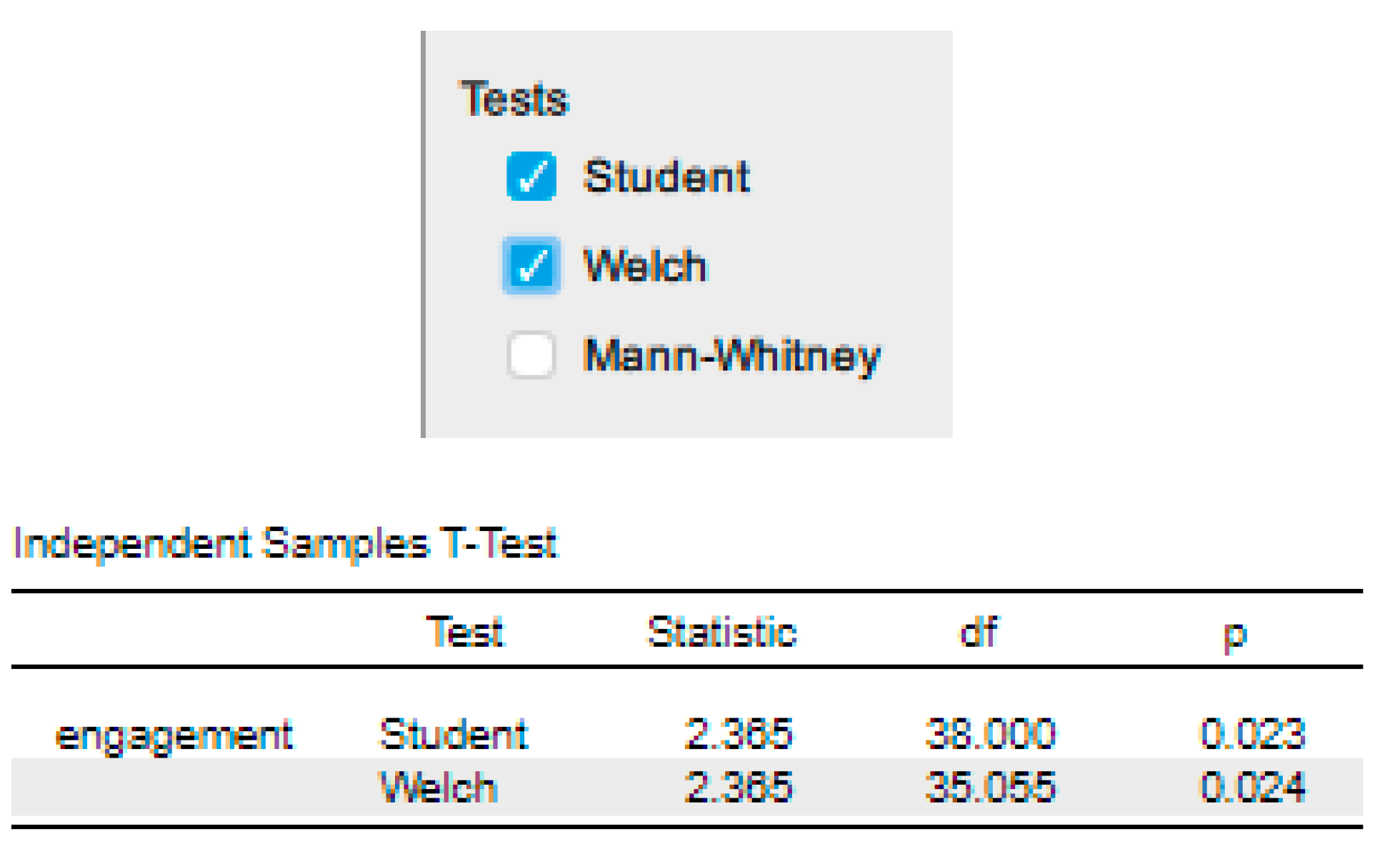

8.2. Assumption of Homogeneity of Variances

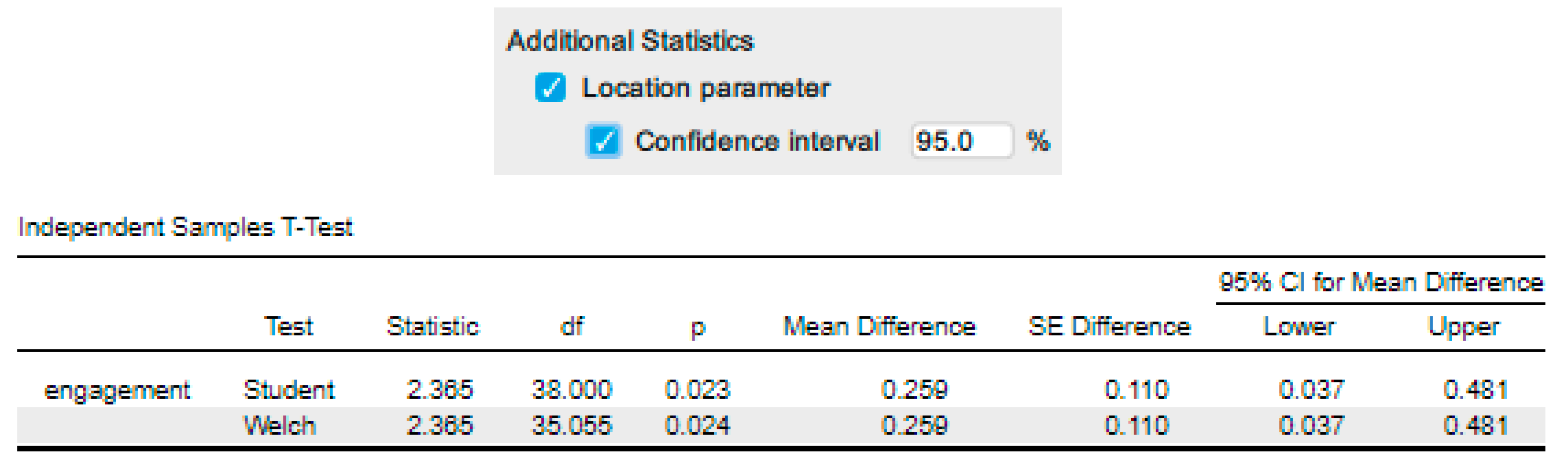

8.3. Mean Difference Between Groups

9. Reporting

9.1. Reporting Statistical Significance

9.2. Reporting the Null and Alternative Hypotheses

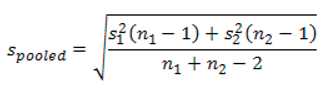

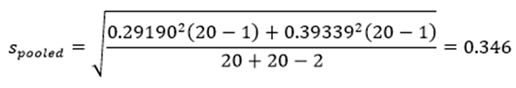

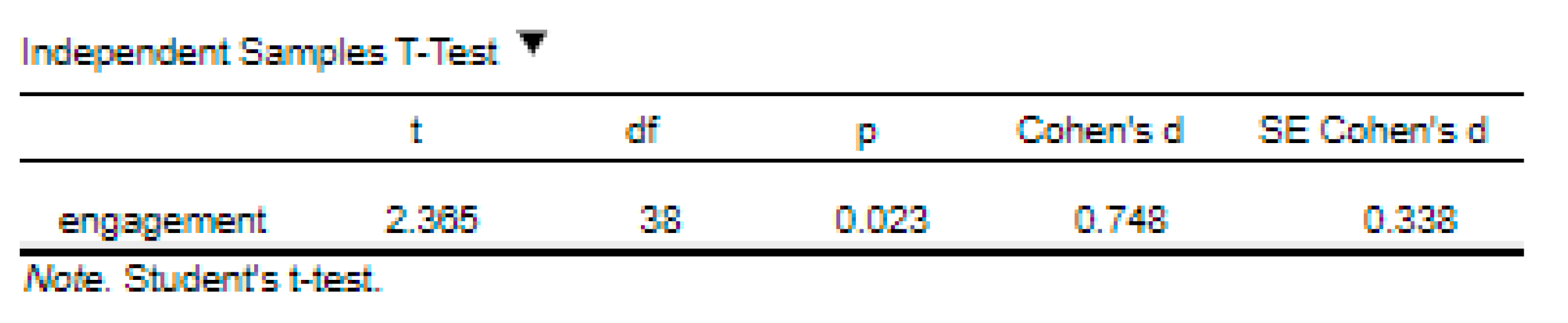

9.3. Calculating and Reporting an Effect Size

10. Practical vs. Statistical Significance

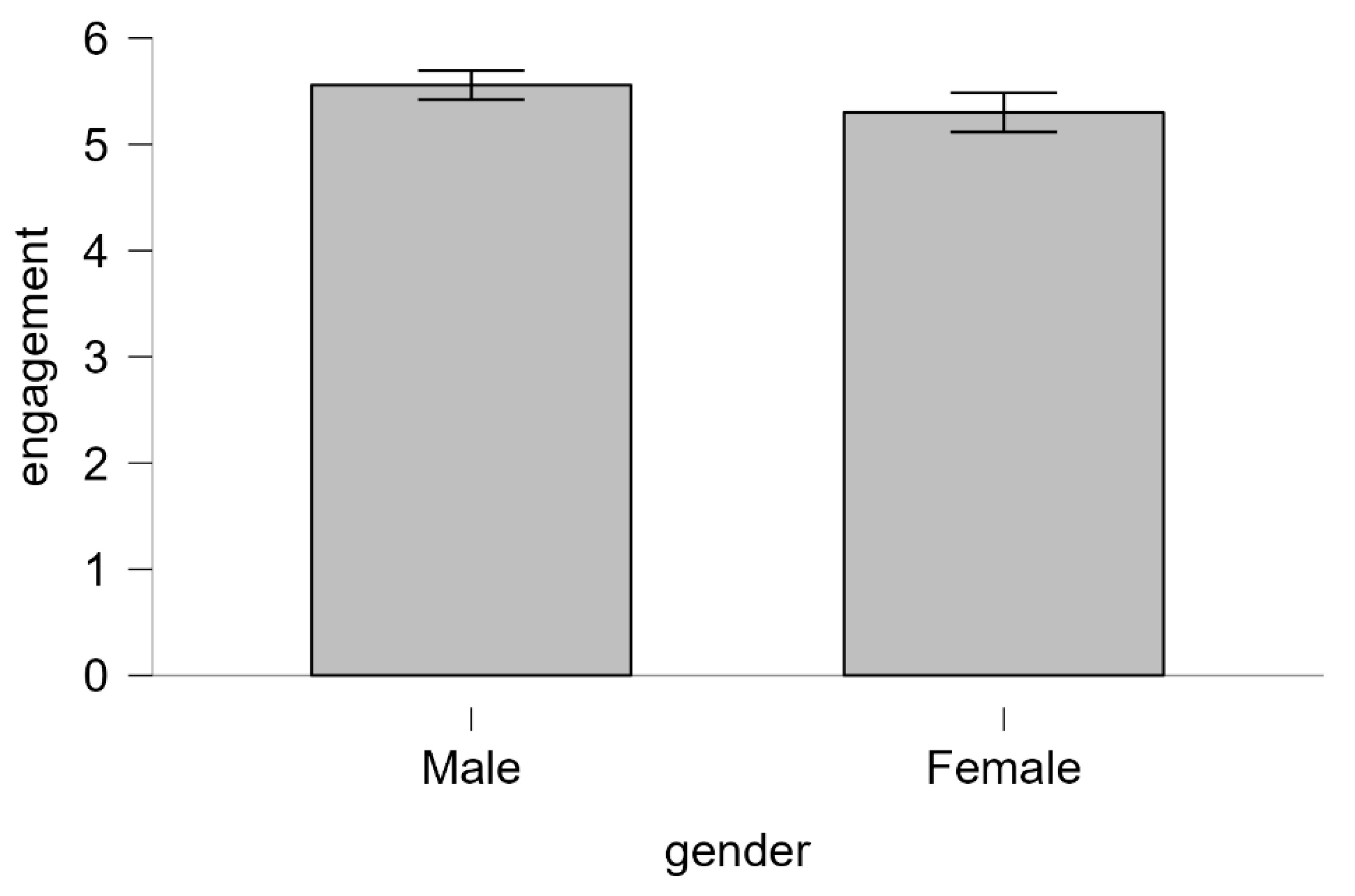

11. Graphing the Output

12. Conclusion

References

- Kim, T.K. T Test as a Parametric Statistic. Korean journal of anesthesiology 2015, 68, 540–546. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, P.; Fiser, J. A Frequentist Two-Sample Test Based on Bayesian Model Selection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1104.2826 2011.

- Alsuof, E.A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Zraikat, M.S.; Khader, H.A.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Zihlif, M.; Ata, O.A.; Zihlif, M.A.; Abu-Samak, M.; Al Maqbali, M. Molecular Detection of Antibiotic Resistance Genes Using Respiratory Sample from Pneumonia Patients. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 502. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Hasoun, L.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; AbuAwad, A.; Basheti, I.; Khader, H.A.; Al Maqbali, M. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Educational Medical Informatics Tutorial on Improving Pharmacy Students’ Knowledge and Skills about the Clinical Problem-Solving Process. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 2652.

- Alimam, S.M.; Alhmoud, J.F.; Khader, H.A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abusamak, M.; Mohammad, B.A.; Mosleh, I.; Khadra, K.A.; Aljaberi, A.; Habash, M. Effect of Weekly High-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation on the Association between Circulatory FGF-23 and A1c Levels in People with Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized Controlled 10-Week Follow-up Trial. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Al-kilkawi, Z.M.; Basheti, I.A.; Obeidat, N.M.; Saleh, M.R.; Hamadi, S.; Abutayeh, R.; Nassar, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Evaluation of the Association between Inhaler Technique and Adherence in Asthma Control: Cross-Sectional Comparative Analysis Study between Amman and Baghdad. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–12.

- Alsayed, A.R. Mastering Descriptive Statistics in JASP: From Data to Decisions for Measures of Central Tendency and Dispersion. 2025.

- Melendez, C. A Monte Carlo Study of Several Different Approaches to the Behrens–Fisher Problem. 2016.

- Al-Rshaidat, M.M.; Al-Sharif, S.; Tamimi, T.A.; Al-Zeer, M.A.; Samhouri, J.; Alsayed, A.R.; Rayyan, Y.M. First Middle Eastern-Based Gut Microbiota Study: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Microbiota-Based Therapies. Pharmacy Practice 2025, 23, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zihlif, M.; Zakaraya, Z.; Feda’Hamdan, A.S.; Tahboub, F.; Qudsi, S.; Abuarab, S.F.; Daghash, R.; Alsayed, A.R. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4, Alpha (HNF4A): A Potential Biomarker for Chronic Hypoxia in MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Pharmacy Practice (1886-3655) 2025, 23. [CrossRef]

- Maddeppungeng, N.M.; Syahirah, N.A.; Hidayati, N.; Rahman, F.U.; Mansjur, K.Q.; Rieuwpassa, I.E.; Setiawati, D.; Fadhlullah, M.; Aziz, A.Y.R.; Salsabila, A. Specific Delivery of Metronidazole Using Microparticles and Thermosensitive in Situ Hydrogel for Intrapocket Administration as an Alternative in Periodontitis Treatment. Journal of Biomaterials science, Polymer edition 2024, 35, 1726–1749. [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.A.; Alhmoud, J.F.; Issa, R.; Khader, H.A.; Mohammad, B.A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Khadra, K.A.; Habash, M.; Aljaberi, A.; Hasoun, L. The Variations of Selected Serum Cytokines Involved in Cytokine Storm after Omega-3 Daily Supplements: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Jordanians with Vitamin D Deficiency. Pharmacy Practice 2024, 22, 1–10.

- AL-awaisheh, R.I.; Alsayed, A.R.; Basheti, I.A. Assessing the Pharmacist’s Role in Counseling Asthmatic Adults Using the Correct Inhaler Technique and Its Effect on Asthma Control, Adherence, and Quality of Life. Patient preference and adherence 2023, 961–972. [CrossRef]

- Nour, A.; Alsayed, A.; Basheti, I. Parents of Asthmatic Children Knowledge of Asthma, Anxiety Level and Quality of Life: Unveiling Important Associations. Pharmacy Practice 2023, 21, 1–10.

- Bader, D.; Abed, A.; Mohammad, B.; Aljaberi, A.; Sundookah, A.; Habash, M. The Effect of Weekly 50,000 IU Vitamin D3 Supplements on the Serum Levels of Selected Cytokines Involved in Cytokine Storm: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Adults with Vitamin D Deficiency. Nutrients. 2023; 15 (5): 1188. [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Bossers, S.M.; Schwarte, L.A. Statistical Significance versus Clinical Importance of Observed Effect Sizes: What Do P Values and Confidence Intervals Really Represent? Anesthesia & Analgesia 2018, 126, 1068–1072.

- Yoon, M.; Lai, M.H. Testing Factorial Invariance with Unbalanced Samples. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2018, 25, 201–213. [CrossRef]

- De Winter, J.C. Using the Student’s" t"-Test with Extremely Small Sample Sizes. Practical assessment, research & evaluation 2013, 18, n10.

- Daboul, S.M.; Abusamak, M.; Mohammad, B.A.; Alsayed, A.R.; Habash, M.; Mosleh, I.; Al-Shakhshir, S.; Issa, R.; Abu-Samak, M. The Effect of Omega-3 Supplements on the Serum Levels of ACE/ACE2 Ratio as a Potential Key in Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial in Participants with Vitamin D Deficiency. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 21, 2761. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rshaidat, M.M.; Al-Sharif, S.; Al Refaei, A.; Shewaikani, N.; Alsayed, A.R.; Rayyan, Y.M. Evaluating the Clinical Application of the Immune Cells’ Ratios and Inflammatory Markers in the Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 21, 2755.

- Al Maqbali, M.; Alsayed, A.; Bashayreh, I. Quality of Life and Psychological Impact among Chronic Disease Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Integrative Nursing 2022, 4, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R.; Al-Dulaimi, A.; Alnatour, D.; Awajan, D.; Alshammari, B. Validation of an Assessment, Medical Problem-Oriented Plan, and Care Plan Tools for Demonstrating the Clinical Pharmacist’s Activities. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2022, 30, 1464–1472. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, H. Testing for Normality: What Is the Best Method. ForsChem Research Reports 2021, 6, 1–38.

- Ntumi, S. Reporting and Interpreting Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA): Adopting the Best Practices in Educational Research. Journal of Research in Educational Sciences (JRES) 2021, 12, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Nordstokke, D.W.; Colp, S.M. A Note on the Assumption of Identical Distributions for Nonparametric Tests of Location. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 2018, 23, n3.

- Shatz, I. Assumption-Checking Rather than (Just) Testing: The Importance of Visualization and Effect Size in Statistical Diagnostics. Behavior Research Methods 2024, 56, 826–845. [CrossRef]

- Khader, H.; Alsayed, A.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Alnatour, D.; Awajan, D.; Alhosanie, T.N.; Samara, A. Pharmaceutical Care and Telemedicine during COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Pharmacy Students, Pharmacists, and Physicians in Jordan. Pharmacia 2022, 69, 891–901.

- Al-Shajlawi, M.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abazid, H.; Awajan, D.; Al-Imam, A.; Basheti, I. Using Laboratory Parameters as Predictors for the Severity and Mortality of COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients. Pharmacy Practice 2022, 20, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Khader, H.; Hasoun, L.Z.; Alsayed, A.; Abu-Samak, M. Potentially Inappropriate Medications Use and Its Associated Factors among Geriatric Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on 2019 Beers Criteria. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 789–795. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, A.R. Mastering Descriptive Statistics in JASP: From Data to Decisions for Measures of Central Tendency and Dispersion. 2025.

- Welch, B.L. The Generalization of ‘STUDENT’S’Problem When Several Different Population Varlances Are Involved. Biometrika 1947, 34, 28–35.

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. 2016.

| Field | Details |

|---|---|

| Purpose | The independent-samples t-test tests whether the means of two independent groups differ on a continuous DV. More specifically, it will let us determine whether the differences between these two groups are statistically significant. |

| Test Names | This test is also known by many different names, including: 1. Independent t-test 2. Independent-measures t-test 3. Between-subjects t-test 4. Unpaired t-test 5. Student's t-test |

| Examples |

Medical Testing: Suppose a pharmaceutical company is testing a new drug to treat a certain disease. They administer the drug to one group of patients (the experimental group) and give a placebo to another group (the control group). The I_DV here is the administration of the drug (or placebo), and the DV could be improvement in symptoms or any change in health indicators, measured numerically. Education Research: In an educational study, researchers might investigate the effectiveness of a new teaching method. They could have one group of students taught using the traditional method (control group) and another group taught using the new method (experimental group). The I_DV is the teaching method, and the DV might be the students' test scores or comprehension levels. Healthcare Research: Consider a study examining the quality of life among individuals with a particular chronic disease, such as diabetes. Researchers recruit participants with diabetes and divide them into two groups based on gender: one group consists of males, and the other consists of females. The I_DV in this study is the participants' gender (male or female), while the DV is the quality-of-life score. |

| No, | Study Designs | Aim | Process | Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Study Design #1 |

Determining if there are differences between two independent groups | This test would be used to determine whether the DV scores differ between the two independent groups. | In this research design, participants are categorised into groups according to a shared characteristic within each group, but not across different groups. |

We have a study design in which we are measuring a DV (e.g., weight, anxiety level, etc.) in two independent groups (e.g., males/females, under 30 years old/30 years old or older, etc.). We wish to know if there is a mean difference in the DV between the two groups. |

| Study Design #2 | Determining if there are differences between interventions | The primary objective is to identify any differences between the two groups, and consequently, between the interventions. |

The study employs a design in which participants are randomly allocated to one of two groups. Each group receives a distinct intervention (for example, Group A receives no intervention, serving as a 'control', while Group B participates in an exercise programme). Typically, the DV of interest (e.g., weight, anxiety level) is measured in each group after the intervention concludes, often using a questionnaire; it may also be assessed during the intervention. Since the DV is not measured prior to the intervention (i.e., without a pre-test score), this type of study design is commonly referred to as a 'post-test only' design. The nature and duration of the interventions may significantly vary. The DV should generally be measured consistently and concurrently across both interventions. Such measurements are frequently conducted at the conclusion of each intervention. |

Participants were randomly assigned to either a six-week exercise training programme or a six-week control group (where no exercise was performed). At the end of each six weeks, participants' blood cholesterol levels were measured as an indicator of health. An independent-samples t-test was then conducted to determine whether significant differences existed in blood cholesterol concentration following the two distinct interventions. The underlying assumption is that any observed differences in the dependent variable, namely blood cholesterol concentration, after the interventions are attributable to the exercise programme. |

| Study Design #3: | Determining if there are differences in change scores | To determine whether the amount of change in the DV differs between two groups that receive different interventions. |

The DV is measured in both groups before and after the intervention. A change score is calculated for each participant by subtracting the pre-test value from the post-test value. An independent-samples t-test is then used to compare these change scores between the two groups to determine whether the intervention produced different levels of change. | A design in which two groups undergo distinct interventions; for example, Group A acts as a control with no intervention, whereas Group B participates in an exercise program. Within each group, the same DV (e.g., weight, anxiety level) is measured at both the pre-intervention and post-intervention phases. Subsequently, a change (gain) score is computed by subtracting the pre-intervention values from the post-intervention values. |

| Step | Method | Procedure A | Procedure B | Dealing with violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Study Design | Assumption 1 | Continuous DV | X |

| Assumption 2 | The I_DV has 2 independent categories/groups | X | ||

| Assumption 3 | Independence of observations | X | ||

| 2 | JASP, Data Preparation | Set up the two variables (I_DV and DV) | I_DV: Nominal DV: scale |

- |

| 3 | JASP, Decision | Assumption 4 | Outliers | Reasons: 1. Data entry errors 2. Measurement errors 3. Genuinely unusual values Actions: A. Keeping the outlier(s) 1. Run the non-parametric. 2. Modify the outlier by replacing the outlier's value with one that is less extreme (e.g., the next largest value instead to maintain its rank). 3. Transform the DV. 4. Include the outlier in the analysis anyway. B. Removing the outlier(s) |

| Assumption 5 | Normality | If the data is not normally distributed, we have 4 options: 1. Transform the data. 2. Use a non-parametric test. 3. Carry on regardless. 4. Run test comparisons. |

||

| Assumption 6 | Assumption of homogeneity of variances | Use an adjusted t-statistic based on the Welch method in case of violation. | ||

| 4 | JASP, Analysis and Interpretation | If all the assumptions are met, run the independent sample t-test | 1. From additional statistics, select the location parameter and 95% CI 2. Select Effect Size; cohen’s d. 3. Select Descriptives 4. Select Descriptives Plot. 5. Select Bar Plots |

- |

| 5 | Reporting | 1. Report assumptions 2. Report descriptive statistics: mean, SD, SE. 3. Report t-test results: mean difference, 95% CI, t-value, df, p-value, effect size. |

- |

| No. | Assumption | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Assumption #1 | We have one DV that is measured at the continuous level. | |

| Assumption #2 | We have one IDV that comprises two categorical, independent groups (i.e., a dichotomous variable). | Note: The two groups of the I_DV are also referred to as "categories" or "levels", but the term "levels" is typically reserved for groups possessing an inherent order (e.g., fitness level, with two levels: "low" and "high"). Individuals cannot belong to multiple groups simultaneously. |

| Assumption #3 | Group Independence: It is essential that observations are independent, indicating that there is no correlation among observations within each group of the I_DV nor between the groups. Both groups must be mutually independent. Each participant will contribute only a single data point for one group. | An important distinction is established in statistical analysis when comparing values across different individuals or within the same individual. Independent groups, examined through an independent-samples t-test, consist of groups with no relationship among the participants within each group. This situation most commonly arises due to differences among participants across groups. Independence requires unrelated individuals within each group, avoiding familial relationships. Additionally, participants in one group should not influence those in another group, thereby ensuring experimental integrity. |

| Assumption #4 |

There should be no significant outliers in the two groups of the I_DV with respect to the DV. |

In both groups of the independent dependent variable (IDV), any scores that are markedly different—either exceedingly small or large in comparison to the other scores—are identified as outliers. Outliers may exert a substantial adverse impact on the outcomes by significantly influencing the mean and standard deviation of the respective group, thereby potentially affecting the results of the statistical analysis. The consideration of outliers becomes increasingly important when dealing with smaller sample sizes, as their influence is proportionally greater. Given that outliers can alter the results, it is necessary to determine whether to include them in the data set when conducting an independent samples t-test using JASP. |

| Assumption #5 |

Normality of the DV: The DV should be approximately normally distributed within each I_DV group. The DV should also be measured on a continuous scale and be approximately normally distributed with no significant outliers. |

The presumption of normality is essential when performing a t-test for independent samples. Nonetheless, the independent-samples t-test is regarded as "robust" to breaches of the normality assumption. This implies that certain violations can be tolerated without compromising the validity of the results. Consequently, it is often stated that this test requires approximately normal data. Moreover, as sample sizes increase, the data distribution may deviate significantly from normality; nevertheless, owing to the Central Limit Theorem, the independent-samples t-test can still yield valid conclusions. Additionally, if the distributions are uniformly skewed (e.g., all moderately negatively skewed), this situation is less problematic compared to scenarios where the groups have differently-shaped distributions (e.g., Group A is moderately positively skewed, while Group B is moderately negatively skewed). |

| Assumption #6 |

Homogeneity of variances (i.e., the variance is equal in each group of the I_DV) | This can be tested using Levene's Test of Equality of Variances. If Levene's Test is statistically significant, indicating unequal group variances, we can correct this violation using an adjusted t-statistic based on the Welch method. |

| Category | Reports |

|---|---|

| Assumptions | |

|

Determining if the data has outliers |

‘There were no outliers in the data, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot for values greater than 1.5 box lengths from the edge of the box.’ |

| ‘The data had no outliers, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot’. | |

|

Determining if the data is normally distributed Shapiro-Wilk test for normality |

‘The DV for each level of I_DV was normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > 0.05).’ |

| ‘The DV was normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > 0.05).’ | |

| Assumption of homogeneity of variances | |

| Assumption of homogeneity of variances was met | ‘Variances were homogeneous for the DV for both groups of the I_DV, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = X).’ |

| ‘Variances were homogeneous, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = 0.X).’ | |

| Assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated | ‘The assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = X).’ |

| Interpreting Results | |

| Descriptive statistics | ‘Data are mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. There were 20 male and 20 female participants. The advertisement was more engaging to males (5.56 ± 0.29) than female viewers (5.30 ± 0.39).’ |

| ‘Data are mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise stated. There were 20 male and 20 female participants. The mean male engagement score (5.56 ± 0.29) was higher than the mean female engagement score (5.30 ± 0.39).’ | |

|

Mean difference between groups Reporting statistical significance Putting it all together |

‘The male mean engagement score was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.48), higher than the female mean engagement score.’ |

| ‘The male mean engagement score was 0.26 ± 0.11 [mean ± standard error] higher than the female mean engagement score.’ | |

| ‘There was a statistically significant difference between means (p < 0.05); therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative hypothesis.’ | |

| We can report the results, without the tests of assumptions, as follows: |

‘An independent-samples t-test was run to determine if there were differences in engagement to an advertisement between males and females. The advertisement was more engaging to male viewers (5.56 ± 0.29) than female viewers (5.30 ± 0.39), with a statistically significant difference of 0.26 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.48), t(38) = 2.365, p = .023.’ |

| Adding in the information about the statistical test we ran, including the assumptions, we have: | ‘Data are mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. There were 20 male and 20 female participants. An independent-samples t-test was run to determine if there were differences in engagement to an advertisement between males and females. The data had no outliers, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot. Engagement scores for each level of gender were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > .05), and variances were homogeneous, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = 0.174). The advertisement was more engaging to male viewers (5.56 ± 0.29) than female viewers (5.30 ± 0.39), a statistically significant difference of 0.26 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.48), t(38) = 2.365, p = 0.023.’ |

|

Calculating and reporting an effect size |

‘Data are mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated. There were 20 male and 20 female participants. An independent-samples t-test was run to determine if there were differences in engagement to an advertisement between males and females. The data had no outliers, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot. Engagement scores for each level of gender were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > .05), and variances were homogeneous, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = 0.174). The advertisement was more engaging to male viewers (5.56 ± 0.29) than female viewers (5.30 ± 0.39), a statistically significant difference of 0.26 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.48), t(38) = 2.365, p = 0.023, d = 0.75.’ |

|

Putting it all together |

‘Data are mean ± standard deviation, unless otherwise stated. There were 20 male and 20 female participants. An independent-sample t-test was run to determine if there were differences in engagement to an advertisement between males and females. The data had no outliers, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot. Engagement scores for each level of gender were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk's test (p > .05), and variances were homogeneous, as assessed by Levene's test for equality of variances (p = 0.174). The advertisement was more engaging to male viewers (5.56 ± 0.29) than female viewers (5.30 ± 0.39), a statistically significant difference of 0.26 (95% CI, 0.04 to 0.48), t(38) = 2.365, p = 0.023, d = .75.’ |

| Effect Size | Strength |

|---|---|

| 0.2 | small |

| 0.5 | medium |

| 0.8 | large |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).