Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

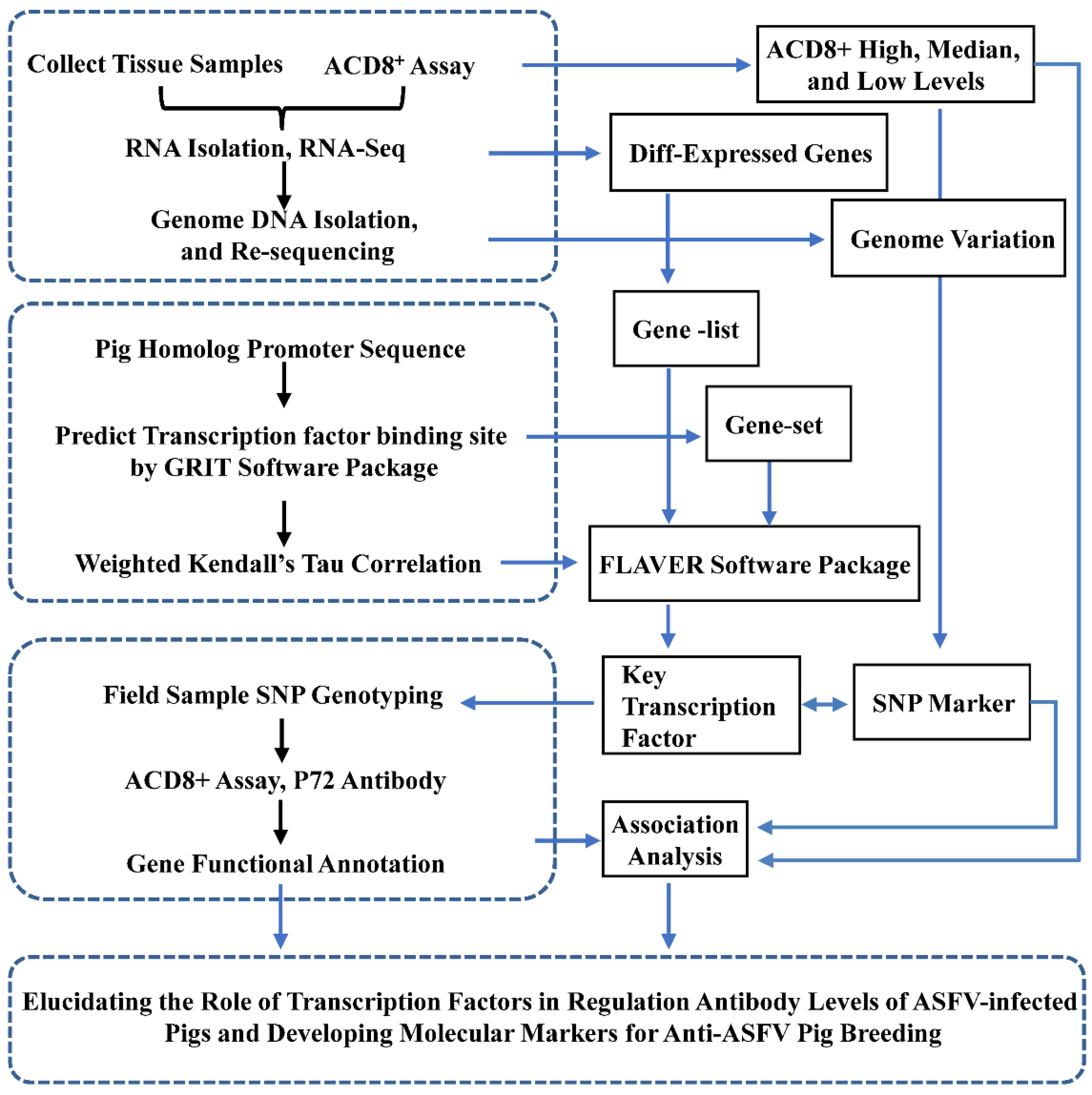

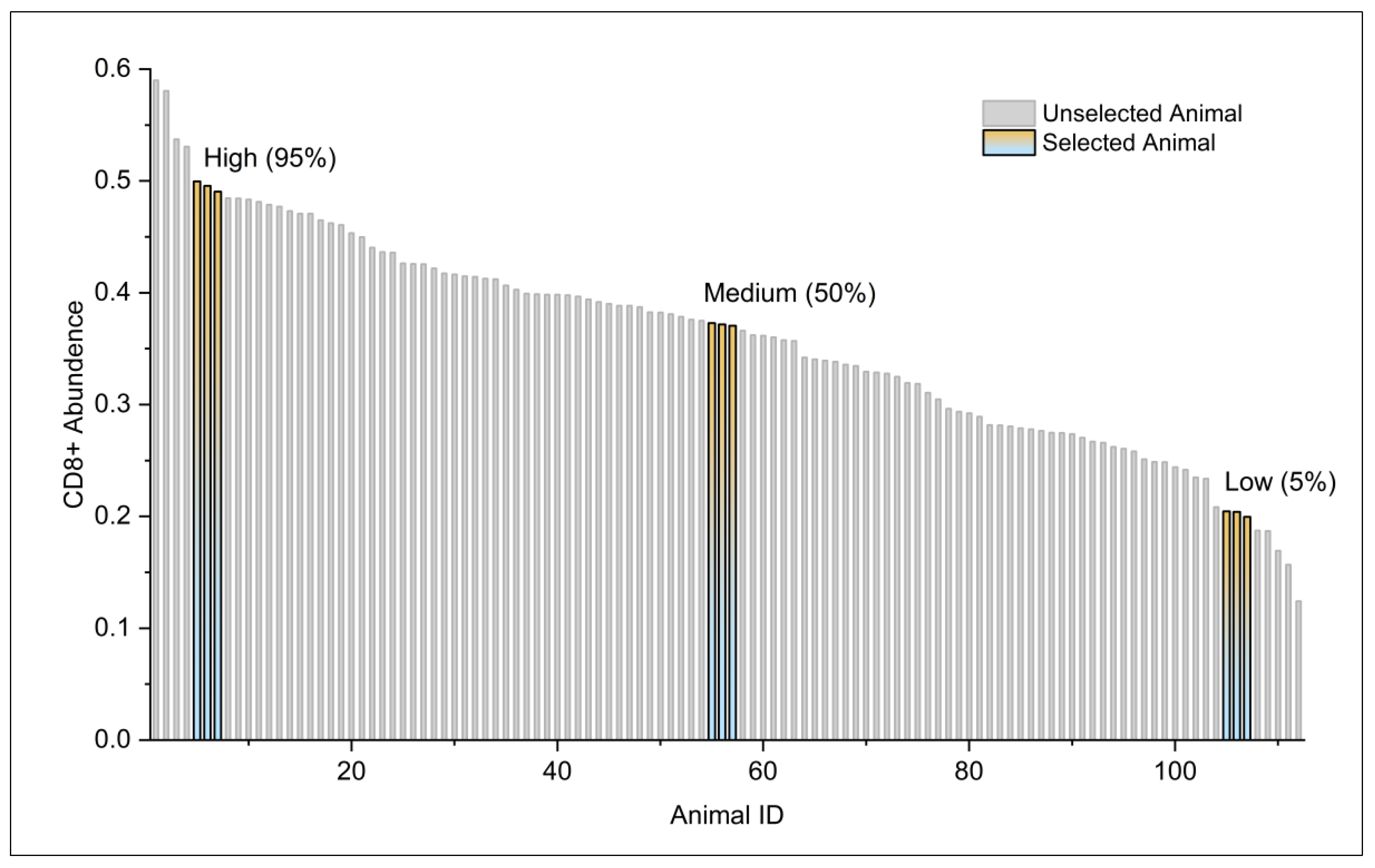

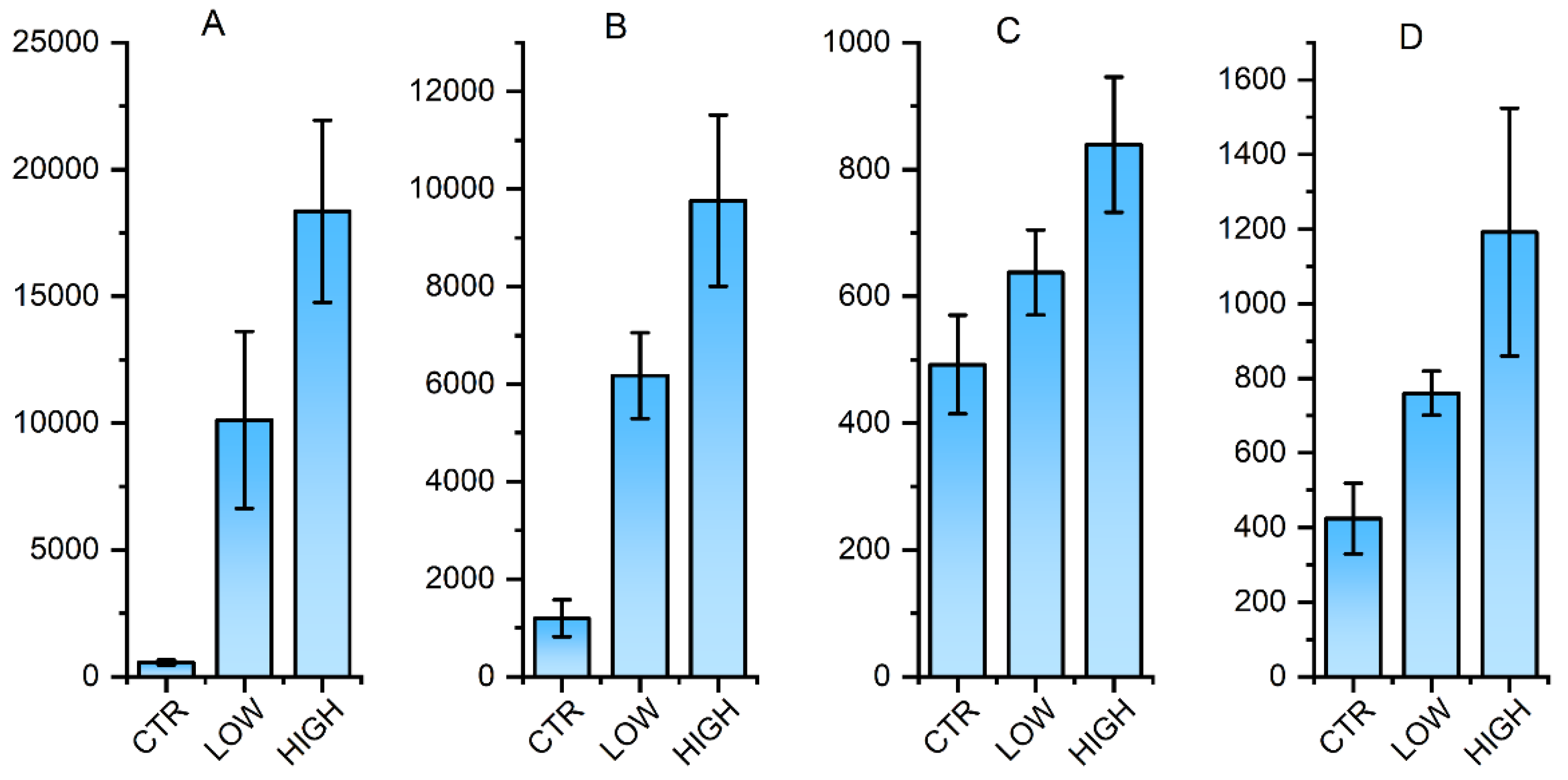

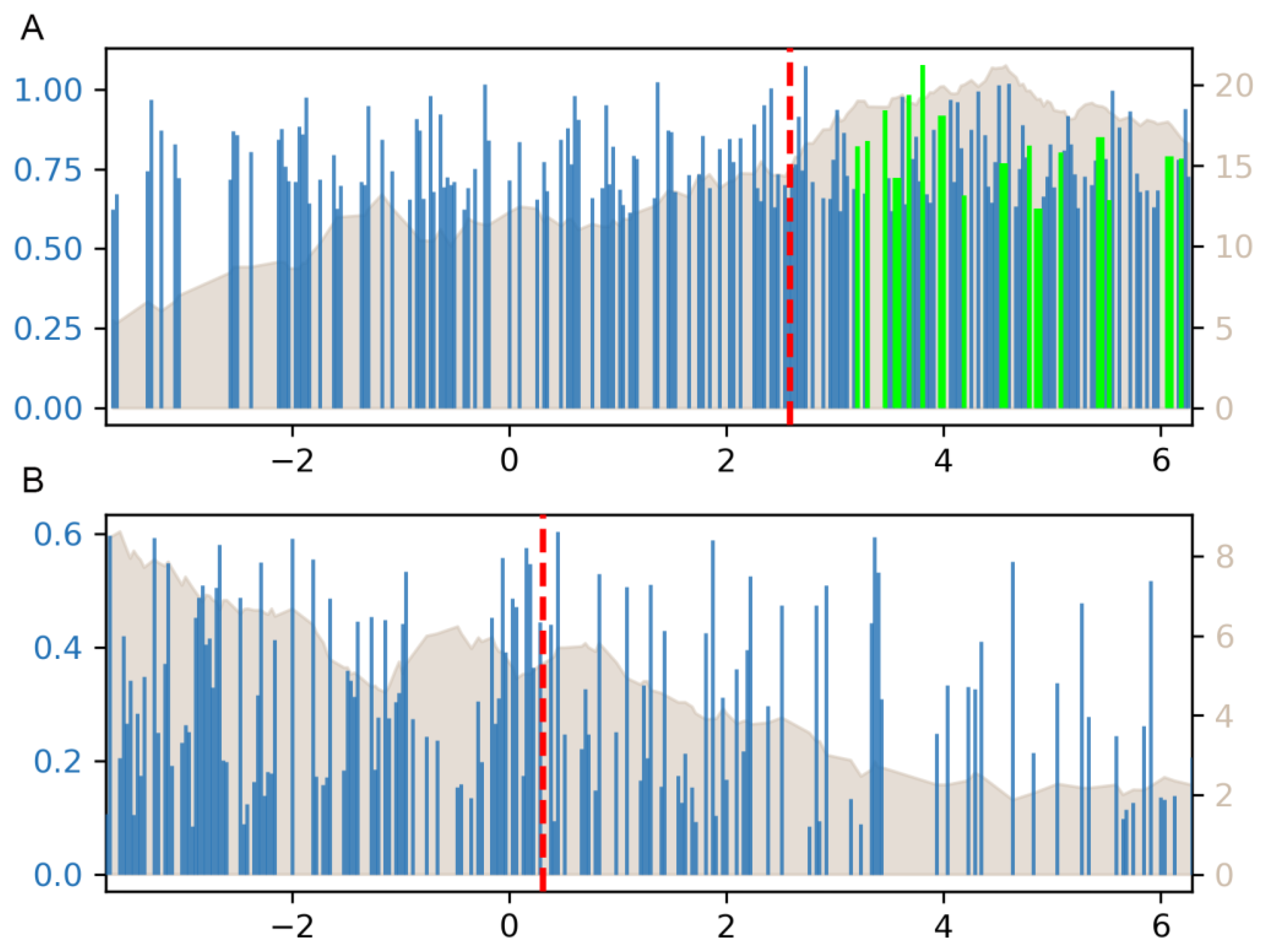

Background: Individual differences in immune responses to African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV), whether induced by vaccination or natural infection, may be linked to genetic variation in genes involved in antigen presentation. Methods: A total of nine pigs from the 112-population were selected for RNA-seq analysis. To pinpoint key transcription factors (TF) regulating gene expression in the lymph nodes, Weighted Kendall's Tau rank correlation analysis was to link the TF binding potential with the extent of differential expression of target genes. Results: CD8+ T cells expressing a specific epitope of the ASFV p72 protein (ACD8+) accounted for 41% of the total CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood. A total of 2,062 transcripts were identified as differentially expressed across the nine pigs (q-value < 1E-8). Differential expression levels of the target genes for MECP2, ETS1, ZBTB33, ELK4, and E2F4 were significantly correlated with their TF binding potential (P < 0.05). Six SNPs were identified in the promoter region of ELK4. Analysis of the 112-pig population revealed that SNPs at S.-404A>G and S.-668C>T loci were significantly associated with ACD8+ levels (q-value < 0.01). Individuals with the AA genotype at S.-404A>G had significantly higher ACD8+ counts compared to those with AG and GG genotypes (q-value < 0.05). At the S.-668C>T locus, ACD8+ levels were highest in the CC genotype, followed by CT and TT genotypes, with CC showing notably higher ACD8+ counts (q-value < 0.05). Notably, the S.-404A>G site overlaps with potential binding sites for TFs FOXA2, GATAs, and TRPS1, while the S.-668C>T site lies within the binding regions for NR1H3, RARA, VDR, and NR1I3. Conclusion: These mutations may disrupt TFs binding to the ELK4 promoter, potentially reducing ELK4 expression and impairing antigen processing and presentation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Testing the abundance of CD8+ T cells specific for ASFV p72 protein peptide

2.3. High Throughput Sequencing

2.4. Identification of key transcription factors

2.5. Genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) based on Sanger sequencing

3. Results

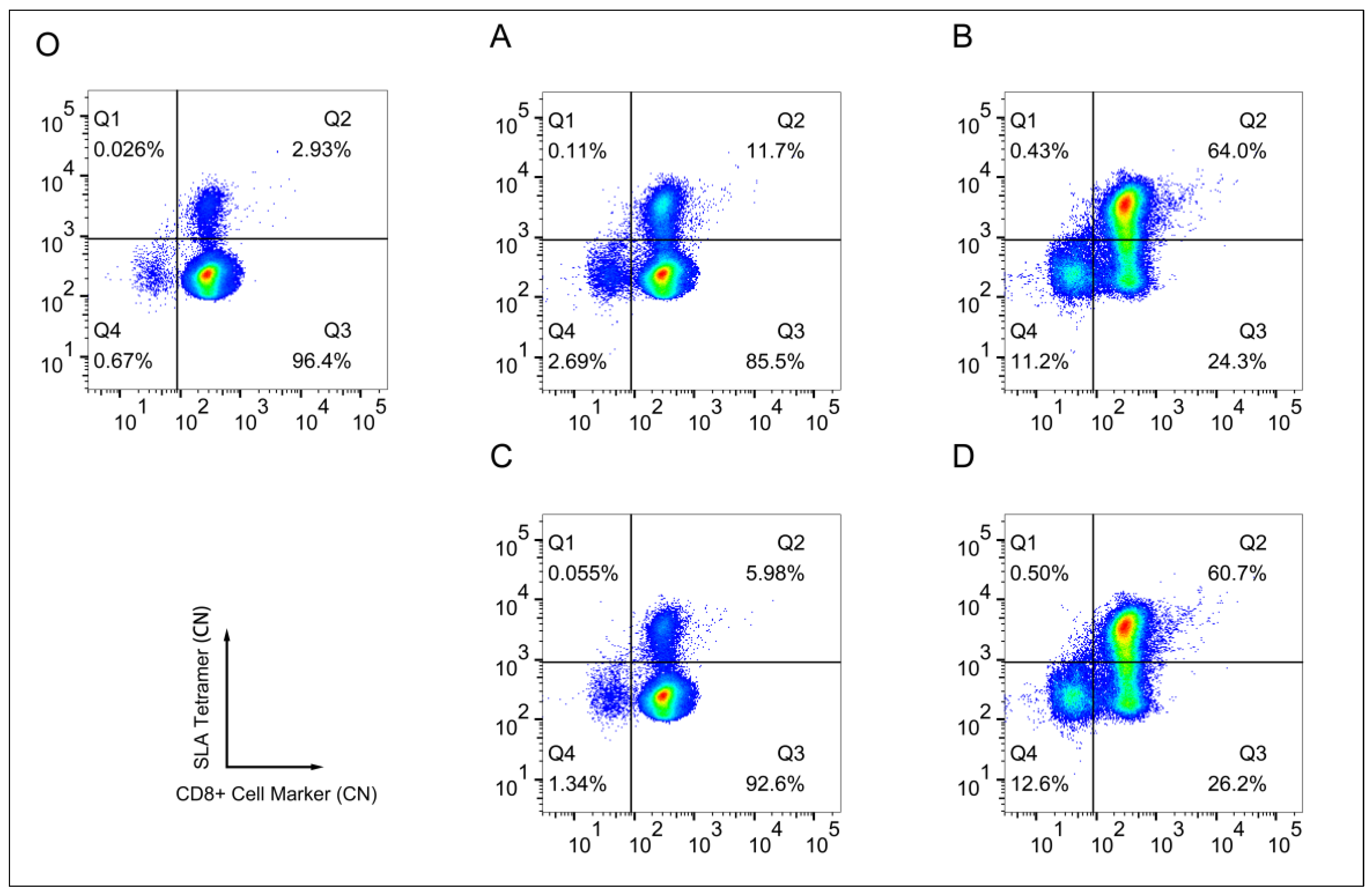

3.1. Specificity of the SLA-Peptide Tetramer Complex

3.2. Lymph node transcriptome analysis of individuals with varying levels of antigen specific CD8+ T cells

3.3. Identification of key transcription factors for antigen-specific CD8+ T cell's abundance

3.4. SNP genotyping and association analysis with the abundance of antigen-specific T cells

| SNP ID | Antigen-specific CD8+ Cell Abundance for Genotype | Overlap with Transcription Factor Binding Site | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XX | Xx | xx | ||

| S.-291C>T | 0.36±0.1a | 0.34±0.1a | 0.31±0.11a | G7566_ZNF18 |

| S.-404A>G | 0.39±0.08a | 0.28±0.08b | 0.21±0.1b | G15376_Foxa2, MA0036.3_GATA2, MA0037.4_Gata3, MA0482.2_GATA4, MA1104.2_GATA6, MA1970.1_TRPS1 |

| S.-463A>C | 0.36±0.09a | 0.35±0.1a | 0.34±0.09a | G20852_Stat6 |

| S.-604C>T | 0.36±0.1a | 0.35±0.08a | 0.36±0.11a | G4772_NFATC1 |

| S.-668C>T | 0.41±0.07a | 0.27±0.06b | 0.19±0.08b | G10062_NR1H3, G12355_Nr1i3, G22337_Vdr, G5914_RARA, G7421_VDR, G9970_NR1I3 |

| S.-808G>A | 0.36±0.09a | 0.35±0.11a | 0.42±0.1a | MA0102.4_CEBPA |

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eustace Montgomery, R. On A Form of Swine Fever Occurring in British East Africa (Kenya Colony). Journal of Comparative Pathology and Therapeutics 1921, 34, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.K.; Islam, M.; Nash, R.; Reis, A.L. African swine fever virus evasion of host defences. Virus Res 2019, 266, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas-Fernández, E.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M.; van den Born, E.; Kosowska, A.; van Kilsdonk, E.; Fernández-Pacheco, P.; Gallardo, C.; Arias, M.; Barasona, J.A. High Doses of Inactivated African Swine Fever Virus Are Safe, but Do Not Confer Protection against a Virulent Challenge. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, M.; de la Torre, A.; Dixon, L.; Gallardo, C.; Jori, F.; Laddomada, A.; Martins, C.; Parkhouse, R.M.; Revilla, Y.; Rodriguez, F.A.J. Approaches and Perspectives for Development of African Swine Fever Virus Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2017, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Yu, H.; Miao, F.; Ke, J.; Hu, R. Attenuated African swine fever viruses and the live vaccine candidates: a comprehensive review. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0319923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.L.; Tabarés, E. Characteristics of the major structural proteins of African swine fever virus: Role as antigens in the induction of neutralizing antibodies. A review. Virology 2022, 571, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ding, P.; Du, Y.; Ren, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Chang, Z.; Li, R.; et al. Development and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of African swine fever virus structural protein, CD2v. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1056117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Geng, R.; Shao, H.; Ye, J.; Qian, K.; Chen, H.; Qin, A. Identification of novel linear epitopes in P72 protein of African swine fever virus recognized by monoclonal antibodies. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1055820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Shi, B.; Geng, R.; Liu, Y.; Gong, L.; Shao, H.; Qian, K.; Chen, H.; Qin, A. Function investigation of p11.5 in ASFV infection. Virol Sin 2024, 39, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, A.J.; Wardley, R.C.; Wilkinson, P.J. The immunological response of pigs and guinea pigs to antigens of African swine fever virus. Arch Virol 1982, 74, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebus, C.A. African swine fever. Adv Virus Res 1988, 35, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blome, S.; Gabriel, C.; Beer, M. Modern adjuvants do not enhance the efficacy of an inactivated African swine fever virus vaccine preparation. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3879–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunwoo, S.Y.; Pérez-Núñez, D.; Morozov, I.; Sánchez, E.G.; Gaudreault, N.N.; Trujillo, J.D.; Mur, L.; Nogal, M.; Madden, D.; Urbaniak, K.; et al. DNA-Protein Vaccination Strategy Does Not Protect from Challenge with African Swine Fever Virus Armenia 2007 Strain. Vaccines (Basel) 2019, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancovich, J.K.; Chapman, D.; Hansen, D.T.; Robida, M.D.; Loskutov, A.; Craciunescu, F.; Borovkov, A.; Kibler, K.; Goatley, L.; King, K.; et al. Immunization of Pigs by DNA Prime and Recombinant Vaccinia Virus Boost To Identify and Rank African Swine Fever Virus Immunogenic and Protective Proteins. J Virol 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopera-Madrid, J.; Osorio, J.E.; He, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Adams, L.G.; Laughlin, R.C.; Mwangi, W.; Subramanya, S.; Neilan, J.; Brake, D.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of mammalian cell derived and Modified Vaccinia Ankara vectored African swine fever subunit antigens in swine. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2017, 185, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilaguet, J.M.; Pérez-Martín, E.; Nofrarías, M.; Gallardo, C.; Accensi, F.; Lacasta, A.; Mora, M.; Ballester, M.; Galindo-Cardiel, I.; López-Soria, S.; et al. DNA vaccination partially protects against African swine fever virus lethal challenge in the absence of antibodies. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, C.C.; Goatley, L.; Fishbourne, E.; Chapman, D.; Cooke, L.; Oura, C.A.; Netherton, C.L.; Takamatsu, H.H.; Dixon, L.K. Deletion of virulence associated genes from attenuated African swine fever virus isolate OUR T88/3 decreases its ability to protect against challenge with virulent virus. Virology 2013, 443, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogweng, P.; Bowden, C.F.; Smyser, T.J.; Muwanika, V.B.; Piaggio, A.J.; Masembe, C. Ancestry and genome-wide association study of domestic pigs that survive African swine fever in Uganda. Trop Anim Health Prod 2024, 56, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisimwa, P.N.; Ongus, J.R.; Tonui, R.; Bisimwa, E.B.; Steinaa, L. Resistance to African swine fever virus among African domestic pigs appears to be associated with a distinct polymorphic signature in the RelA gene and upregulation of RelA transcription. Virol J 2024, 21, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, P.C.; Zinkernagel, R.M. T-cell-mediated immunopathology in viral infections. Transplant Rev 1974, 19, 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchereau, J.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 1998, 392, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, F.J. Comparative Pathology and Pathogenesis of African Swine Fever Infection in Swine. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, P.R.; Ploegh, H.L. How MHC class II molecules acquire peptide cargo: biosynthesis and trafficking through the endocytic pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1995, 11, 267–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.J.; van der Merwe, P.A. The kinetic-segregation model: TCR triggering and beyond. Nat Immunol 2006, 7, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.E.; Harndahl, M.; Rasmussen, M.; Lamberth, K.; Golde, W.T.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M.; Buus, S. Porcine major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and analysis of their peptide-binding specificities. Immunogenetics 2011, 63, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.E.; Jungersen, G.; Sorensen, M.R.; Ho, C.S.; Vadekær, D.F. Swine Leukocyte Antigen (SLA) class I allele typing of Danish swine herds and identification of commonly occurring haplotypes using sequence specific low and high resolution primers. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2014, 162, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patch, J.R.; Pedersen, L.E.; Toka, F.N.; Moraes, M.; Grubman, M.J.; Nielsen, M.; Jungersen, G.; Buus, S.; Golde, W.T. Induction of foot-and-mouth disease virus-specific cytotoxic T cell killing by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2011, 18, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Leary, N.A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J.B.; Anderson, W.R.; Falk, R.; Hem, V.; Tsuchiya, M.T.N.; Schuler, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Torcivia, J.; et al. Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Sci Data 2024, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, G.H.; Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Pimanda, J.E.; Zanini, F. Analysing high-throughput sequencing data in Python with HTSeq 2.0. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2943–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Xiao, H.; Tian, Q.; He, Z.; Yuan, C.; Lin, Z.; Gao, X.; Yao, M. Identification of upstream transcription factor binding sites in orthologous genes using mixed Student's t-test statistics. PLoS Comput Biol 2022, 18, e1009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Niu, S.; Zhang, F.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Yao, M. Correlating gene expression levels with transcription factor binding sites facilitates identification of key transcription factors from transcriptome data. Front Genet 2024, 15, 1511456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; He, H.; Wang, B.; Huang, X.; Zheng, S.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Huang, T. Testing the Significance of Ranked Gene Sets in Genome-wide Transcriptome Profiling Data Using Weighted Rank Correlation Statistics. Curr Genomics 2024, 25, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Ramanathan, P.; Bishop, E.A.; O'Donnell, V.; Gladue, D.P.; Borca, M.V. Mechanisms of African swine fever virus pathogenesis and immune evasion inferred from gene expression changes in infected swine macrophages. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0223955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Nie, S.; Feng, W.H. Regulation of antiviral immune response by African swine fever virus (ASFV). Virol Sin 2022, 37, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, N.; Burnaevskiy, N.; Chen, D.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Alto, N.M.; Yan, N. STING Activation by Translocation from the ER Is Associated with Infection and Autoinflammatory Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ao, D.; Jiang, S.; Xia, N.; Xu, Y.; Shao, Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, W.; Chen, N.; et al. African Swine Fever Virus A528R Inhibits TLR8 Mediated NF-κB Activity by Targeting p65 Activation and Nuclear Translocation. Viruses 2021, 13, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, H.; Xue, M.; Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Feng, C.; Cao, S.; Ye, G.; Zhou, Q.; et al. African Swine Fever Virus HLJ/18 CD2v Suppresses Type I IFN Production and IFN-Stimulated Genes Expression through Negatively Regulating cGMP-AMP Synthase-STING and IFN Signaling Pathways. J Immunol 2023, 210, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogal, M.L.; González de Buitrago, G.; Rodríguez, C.; Cubelos, B.; Carrascosa, A.L.; Salas, M.L.; Revilla, Y. African swine fever virus IAP homologue inhibits caspase activation and promotes cell survival in mammalian cells. J Virol 2001, 75, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Sun, J.; Xu, X. The A179L Gene of African Swine Fever Virus Suppresses Virus-Induced Apoptosis but Enhances Necroptosis. Viruses 2021, 13, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.K.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Galindo, I.; Alonso, C. Investigations of Pro- and Anti-Apoptotic Factors Affecting African Swine Fever Virus Replication and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Belmonte, R.; Pérez-Núñez, D.; Pittau, M.; Richt, J.A.; Revilla, Y. African Swine Fever Virus Armenia/07 Virulent Strain Controls Interferon Beta Production through the cGAS-STING Pathway. J Virol 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, C.; Bustos, M.J.; Granja, A.G.; de León, P.; Sabina, P.; López-Viñas, E.; Gómez-Puertas, P.; Revilla, Y.; Carrascosa, A.L. The African swine fever virus lectin EP153R modulates the surface membrane expression of MHC class I antigens. Arch Virol 2011, 156, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannhorst, K.; Carlson, J.; Hölper, J.E.; Grey, F.; Baillie, J.K.; Höper, D.; Wöhnke, E.; Franzke, K.; Karger, A.; Fuchs, W.; et al. The non-classical major histocompatibility complex II protein SLA-DM is crucial for African swine fever virus replication. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinkernagel, R.M.; Doherty, P.C. Restriction of in vitro T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in lymphocytic choriomeningitis within a syngeneic or semiallogeneic system. Nature 1974, 248, 701–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallusto, F.; Lenig, D.; Förster, R.; Lipp, M.; Lanzavecchia, A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 1999, 401, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Bevan, M.J. CD8(+) T cells: foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity 2011, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyst, M.J.; Bird, A. Rett syndrome: a complex disorder with simple roots. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S.Q.; Lykken, E.; Zhao, L.T.; Sevilla, J.; Zhu, B.; Li, Q.J. MeCP2 enforces Foxp3 expression to promote regulatory T cells' resilience to inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, E2807–E2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Shao, F.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, W. ETS Transcription Factors in Immune Cells and Immune-Related Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhao, Q.; Tang, D. Machine learning and single-cell sequencing reveal the potential regulatory factors of mitochondrial autophagy in the progression of gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 15561–15572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W.; Ge, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Lin, L.; Li, J.; Liu, C.Y.; et al. ELK4 exerts opposite roles in cytokine/chemokine production and degranulation in activated mast cells. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1171380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fan, G.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Hu, M.; Shen, S.; Liu, S.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, R. The role of ELK4 up-regulation in macrophage polarization and its mechanism in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Int Immunopharmacol 2025, 163, 115226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, D.; Costello, P.; Sargent, M.; Treisman, R. ERK Signaling Controls Innate-like CD8(+) T Cell Differentiation via the ELK4 (SAP-1) and ELK1 Transcription Factors. J Immunol 2018, 201, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L. MKL1/2 and ELK4 co-regulate distinct serum response factor (SRF) transcription programs in macrophages. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | Averaged Expression Level (logg2) | Fold Change | P-value | P-value Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKRD11 | 11.1479 | -2.6274 | 1.36E-22 | 1.58E-18 |

| RAI1 | 9.0294 | -2.9162 | 3.82E-21 | 2.22E-17 |

| TNRC18 | 10.2425 | -2.5437 | 3.43E-16 | 1.33E-12 |

| GSE1 | 9.4431 | -2.3632 | 1.18E-15 | 3.44E-12 |

| SCAF1 | 8.9799 | -2.0116 | 3.29E-15 | 7.68E-12 |

| ZC3H18 | 9.6552 | -1.8883 | 2.89E-14 | 5.62E-11 |

| EHBP1L1 | 10.9143 | -1.7063 | 2.86E-13 | 4.76E-10 |

| MAD1L1 | 8.5019 | -1.8961 | 5.03E-13 | 7.33E-10 |

| SART1 | 8.7391 | -1.9650 | 5.89E-12 | 7.63E-09 |

| SOD3 | 6.7259 | -2.5104 | 2.05E-11 | 2.38E-08 |

| ZNF865 | 6.0999 | -2.4209 | 5.90E-10 | 6.25E-07 |

| TRAPPC12 | 9.1359 | -1.6968 | 9.63E-10 | 9.36E-07 |

| 5_8S_rRNA | 5.2200 | -7.1821 | 1.31E-09 | 1.17E-06 |

| CRAMP1 | 8.9867 | -1.7361 | 1.70E-09 | 1.42E-06 |

| PLEC | 12.1363 | -1.4223 | 4.38E-09 | 3.40E-06 |

| MYCT1 | 9.8294 | -2.5476 | 4.69E-09 | 3.42E-06 |

| HIC1 | 8.5407 | -1.9721 | 1.03E-08 | 7.09E-06 |

| HDGF | 9.8249 | -1.3268 | 1.45E-08 | 9.38E-06 |

| HTATSF1 | 9.5369 | -1.5280 | 1.93E-08 | 1.12E-05 |

| PRR11 | 8.8894 | -2.5128 | 1.92E-08 | 1.12E-05 |

| MAPK7 | 8.2983 | -1.8414 | 2.68E-08 | 1.49E-05 |

| CAMSAP1 | 9.1223 | -1.4343 | 3.39E-08 | 1.80E-05 |

| CCDC88C | 9.4835 | -1.3329 | 4.81E-08 | 2.44E-05 |

| ZNF579 | 5.8989 | -2.1196 | 6.21E-08 | 3.02E-05 |

| C17orf78 | 5.2230 | -3.7325 | 7.80E-08 | 3.56E-05 |

| COL6A1 | 11.9465 | -1.9199 | 7.93E-08 | 3.56E-05 |

| PPARGC1B | 7.3056 | -1.8476 | 1.03E-07 | 4.46E-05 |

| BAHCC1 | 7.3152 | -1.8492 | 1.19E-07 | 4.78E-05 |

| SYNPO | 6.9863 | -2.0361 | 1.17E-07 | 4.78E-05 |

| CACNA1F | 5.4370 | -2.3937 | 1.79E-07 | 6.74E-05 |

| Gene symbol | Averaged expression level (logg2) | Fold change | P-value | P-value adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPS27 | 11.5508 | 4.1664 | 3.62E-41 | 4.31E-37 |

| SERINC1 | 9.6209 | 4.8169 | 3.46E-39 | 2.06E-35 |

| DDX3X | 11.3334 | 3.9483 | 2.52E-37 | 1.00E-33 |

| IFIT5 | 10.3411 | 5.7359 | 2.91E-36 | 8.68E-33 |

| IL33 | 9.4154 | 3.9776 | 3.83E-35 | 9.13E-32 |

| CHMP5 | 8.7612 | 5.1705 | 2.09E-33 | 4.15E-30 |

| COX7C | 8.9350 | 4.3618 | 3.55E-33 | 6.04E-30 |

| TMEM33 | 8.7260 | 4.2521 | 1.54E-32 | 2.30E-29 |

| IFI44L | 10.8402 | 5.0269 | 2.05E-31 | 2.71E-28 |

| CYTIP | 10.1038 | 3.9767 | 7.62E-31 | 9.09E-28 |

| SNRPE | 8.1885 | 5.0955 | 1.08E-30 | 1.17E-27 |

| SLC38A2 | 10.2469 | 3.8788 | 2.41E-30 | 2.40E-27 |

| RESF1 | 10.1303 | 3.4245 | 1.42E-29 | 1.30E-26 |

| BLTP1 | 10.3354 | 3.7263 | 2.51E-29 | 2.14E-26 |

| PSMA1 | 9.0348 | 4.8175 | 3.18E-29 | 2.53E-26 |

| CNOT7 | 8.5011 | 5.2794 | 4.25E-29 | 3.17E-26 |

| STT3B | 9.4294 | 3.6171 | 1.90E-28 | 1.33E-25 |

| TMED2 | 8.5665 | 4.8602 | 2.92E-28 | 1.94E-25 |

| CLIC2 | 8.4517 | 4.7903 | 3.98E-28 | 2.50E-25 |

| HSPE1 | 9.1219 | 4.8445 | 1.07E-27 | 6.40E-25 |

| USP34 | 9.8910 | 3.5871 | 1.28E-27 | 7.26E-25 |

| BCL2A1 | 8.2664 | 4.9111 | 3.86E-27 | 2.09E-24 |

| CCNT2 | 8.6709 | 4.4719 | 6.15E-27 | 3.19E-24 |

| TRPM7 | 9.7825 | 3.8772 | 7.35E-27 | 3.65E-24 |

| JCHAIN | 11.5718 | 3.6999 | 1.50E-26 | 7.16E-24 |

| ZFYVE16 | 8.9988 | 4.3539 | 1.57E-26 | 7.20E-24 |

| RICTOR | 9.3228 | 3.2834 | 3.18E-26 | 1.40E-23 |

| RPL26 | 9.1549 | 4.2806 | 8.87E-26 | 3.78E-23 |

| COPB2 | 8.8352 | 3.3305 | 1.23E-25 | 5.07E-23 |

| CHORDC1 | 9.2806 | 3.8059 | 1.28E-25 | 5.10E-23 |

| Transcription factor | Number of target genes | Correlation direction | Kendall's Tau | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G4204_MECP2 | 2990 | + | 0.1202 | 4.36E-20 | 3.18E-17 |

| G17257_Mecp2 | 2990 | + | 0.1202 | 4.30E-20 | 6.29E-17 |

| MA0098.3_ETS1 | 2154 | + | 0.1359 | 2.44E-18 | 5.10E-16 |

| G56805_Zbtb33 | 1986 | + | 0.1403 | 2.44E-18 | 5.95E-16 |

| G2002_ELK1 | 2630 | + | 0.1242 | 1.33E-18 | 6.48E-16 |

| G10009_ZBTB33 | 1986 | + | 0.1404 | 2.38E-18 | 6.95E-16 |

| MA0076.2_ELK4 | 1472 | + | 0.1655 | 2.12E-18 | 7.76E-16 |

| G104394_E2f4 | 3124 | + | 0.1094 | 1.67E-17 | 3.06E-15 |

| MA1949.1_FLI1::DRGX | 1302 | + | 0.1672 | 3.04E-17 | 4.93E-15 |

| MA1959.1_KLF7 | 3034 | + | 0.1068 | 2.68E-16 | 3.92E-14 |

| MA1483.2_ELF2 | 1522 | + | 0.1507 | 8.91E-16 | 1.18E-13 |

| MA0760.1_ERF | 1978 | + | 0.1305 | 1.10E-15 | 1.35E-13 |

| MA1931.1_ELK1::HOXA1 | 710 | + | 0.2193 | 1.31E-15 | 1.47E-13 |

| MA0666.2_MSX1 | 2092 | + | 0.1253 | 2.65E-15 | 2.77E-13 |

| MA0764.3_ETV4 | 2486 | + | 0.1154 | 2.85E-15 | 2.78E-13 |

| G6668_SP2 | 2986 | + | 0.1037 | 3.75E-15 | 3.23E-13 |

| G78912_Sp2 | 2986 | + | 0.1037 | 3.75E-15 | 3.43E-13 |

| MA0889.1_GBX1 | 1914 | + | 0.1292 | 5.11E-15 | 4.15E-13 |

| MA1651.1_ZFP42 | 798 | + | 0.2009 | 8.44E-15 | 6.50E-13 |

| MA0475.2_FLI1 | 1288 | + | 0.1564 | 1.67E-14 | 1.22E-12 |

| MA1564.1_SP9 | 2842 | + | 0.1028 | 3.55E-14 | 2.47E-12 |

| G7022_TFAP2C | 2680 | - | -0.1051 | 4.35E-14 | 2.89E-12 |

| MA1548.1_PLAGL2 | 1094 | - | -0.1659 | 4.73E-14 | 3.01E-12 |

| MA0654.1_ISX | 2196 | + | 0.1138 | 1.34E-13 | 8.18E-12 |

| MA0641.1_ELF4 | 674 | + | 0.2074 | 2.69E-13 | 1.57E-11 |

| MA1940.1_ETV2::DRGX | 644 | + | 0.2093 | 3.29E-13 | 1.85E-11 |

| G2005_ELK4 | 2536 | + | 0.1049 | 4.14E-13 | 2.24E-11 |

| MA0862.1_GMEB2 | 2154 | + | 0.1128 | 4.81E-13 | 2.51E-11 |

| MA0604.1_Atf1 | 1572 | + | 0.1317 | 9.44E-13 | 4.76E-11 |

| MA0723.2_VAX2 | 1906 | - | -0.1189 | 9.82E-13 | 4.79E-11 |

| Transcription factor | Number of target genes | Correlation direction | Kendall's Tau | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G56805_Zbtb33 | 1790 | + | 0.1432 | 3.33E-17 | 2.44E-14 |

| G10009_ZBTB33 | 1790 | + | 0.1432 | 3.25E-17 | 4.75E-14 |

| MA1564.1_SP9 | 2532 | + | 0.1192 | 1.96E-16 | 5.72E-14 |

| G4204_MECP2 | 2672 | + | 0.1159 | 1.81E-16 | 6.62E-14 |

| G17257_Mecp2 | 2672 | + | 0.1159 | 1.81E-16 | 8.81E-14 |

| MA0098.3_ETS1 | 1938 | + | 0.13 | 4.88E-15 | 1.19E-12 |

| G104394_E2f4 | 2824 | + | 0.1061 | 9.10E-15 | 1.90E-12 |

| MA0076.2_ELK4 | 1350 | + | 0.1515 | 3.95E-14 | 7.22E-12 |

| MA0666.2_MSX1 | 1904 | + | 0.1223 | 2.40E-13 | 3.89E-11 |

| MA1483.2_ELF2 | 1366 | + | 0.1441 | 3.93E-13 | 4.78E-11 |

| MA0760.1_ERF | 1772 | + | 0.1258 | 3.75E-13 | 4.98E-11 |

| G21414_Tcf7 | 2034 | - | -0.1154 | 3.47E-13 | 5.07E-11 |

| MA0747.1_SP8 | 2672 | + | 0.1002 | 1.03E-12 | 1.15E-10 |

| G2002_ELK1 | 2362 | + | 0.106 | 1.93E-12 | 1.76E-10 |

| G13712_Elk1 | 2592 | + | 0.1012 | 1.73E-12 | 1.81E-10 |

| MA0764.3_ETV4 | 2224 | + | 0.1093 | 1.90E-12 | 1.85E-10 |

| MA1944.1_ETV5::DRGX | 1668 | + | 0.1237 | 3.48E-12 | 2.68E-10 |

| MA1583.1_ZFP57 | 2028 | + | 0.1115 | 3.14E-12 | 2.70E-10 |

| MA0765.3_ETV5 | 836 | + | 0.1793 | 3.37E-12 | 2.74E-10 |

| MA0654.1_ISX | 2002 | + | 0.1104 | 9.17E-12 | 6.70E-10 |

| MA0517.1_STAT1::STAT2 | 744 | + | 0.1831 | 1.11E-11 | 7.74E-10 |

| MA0763.1_ETV3 | 2136 | + | 0.1068 | 1.48E-11 | 9.84E-10 |

| G2115_ETV1 | 2648 | + | 0.0953 | 1.74E-11 | 1.10E-09 |

| MA0006.1_Ahr::Arnt | 2702 | + | 0.0926 | 3.07E-11 | 1.87E-09 |

| G1044_CDX1 | 1314 | - | -0.1303 | 3.67E-11 | 1.99E-09 |

| G13555_E2f1 | 2976 | + | 0.0881 | 3.46E-11 | 2.02E-09 |

| G12590_Cdx1 | 1314 | - | -0.1303 | 3.66E-11 | 2.06E-09 |

| G14390_Gabpa | 2092 | + | 0.1053 | 4.00E-11 | 2.09E-09 |

| MA0151.1_Arid3a | 2456 | - | -0.0949 | 4.26E-11 | 2.14E-09 |

| MA0645.1_ETV6 | 2472 | + | 0.0961 | 5.75E-11 | 2.80E-09 |

| Gene symbol | Averaged expression level (logg2) | Fold change | P-value | P-value adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASB3 | 7.73 | 3.82 | 5.01E-07 | 1.97E-06 |

| CDC16 | 8.35 | 3.83 | 1.42E-07 | 6.16E-07 |

| CDC27 | 9.09 | 12.71 | 8.89E-23 | 4.63E-21 |

| FBXO30 | 8.05 | 4.76 | 6.35E-07 | 2.46E-06 |

| KLHL20 | 7.53 | 6.88 | 2.09E-11 | 1.72E-10 |

| LNPEP | 11.04 | 12.55 | 5.36E-22 | 2.49E-20 |

| LTN1 | 9.28 | 5.52 | 5.65E-14 | 7.18E-13 |

| PIK3R4 | 8.51 | 5.09 | 6.76E-08 | 3.06E-07 |

| PJA2 | 9.96 | 10.78 | 4.50E-15 | 6.79E-14 |

| PSMB1 | 9.13 | 9.05 | 2.22E-03 | 4.53E-03 |

| PSMB4 | 9.82 | 7.30 | 3.11E-15 | 4.83E-14 |

| PSMC2 | 9.16 | 7.49 | 1.75E-12 | 1.72E-11 |

| PSMD12 | 8.04 | 4.42 | 7.87E-09 | 4.12E-08 |

| PSMD8 | 8.62 | 5.45 | 1.81E-09 | 1.06E-08 |

| PSME4 | 9.56 | 4.95 | 3.32E-16 | 6.02E-15 |

| PSMF1 | 8.47 | 2.74 | 5.40E-04 | 1.24E-03 |

| RLIM | 8.03 | 13.27 | 1.70E-03 | 3.53E-03 |

| TLR4 | 8.39 | 6.12 | 4.79E-06 | 1.58E-05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).