1. Introduction

In recent decades, the production, dissemination, and use of knowledge have become decisive factors in socioeconomic development—both through the incorporation of discoveries into products and human skills, and through the competitive pressure among firms, cities, and countries, which makes innovation an imperative [

1]. This phenomenon, termed the Knowledge Economy or Knowledge Society, together with macroeconomic trends and international political dynamics, has guided public policies worldwide, particularly in the formation and strengthening of robust knowledge-generation capacities for regional development [

2,

3,

4,

5].

In this context, public policies have allocated material and immaterial resources to strategic sites—ranging from land parcels and districts to entire cities—with the aim of producing, disseminating, and applying knowledge. This movement builds on the precedent of first- and second-generation science and technology parks, generally located in suburban areas near universities and, respectively, organized according to linear “science push” and “demand pull” models [

6]. A pioneering example is the Stanford Research Park where, in 1950, Stanford University allocated land for companies and research centers, establishing a direct university–industry communication channel.

Seventy-five years after the establishment of the first of these strategic sites, both the nomenclature and the number of initiatives have multiplied—with around 1,500 examples already recorded in 2009 [

7]. Initially, the variations centered on the term “park,” generating labels such as science and technology park, science park, science, technology and innovation park, research park, and innovation park. More recently, due to macroeconomic and social transformations and shifts in the knowledge production modes and use, contemporary denominations have emerged that broaden the conceptual scope, such as knowledge city, innovation area, innovation district, knowledge district, knowledge region, knowledge and innovation space, and knowledge and innovation environment [

8]. This semantic broadening even influenced the International Association of Science Parks (IASP), which incorporated “areas of innovation” into its name and scope of action.

Although the terminological proliferation surrounding these sites demonstrates their diversity and adaptability, it generates substantial challenges. First, the multiplicity of concepts fragments the body of literature, hindering the systematization of studies and the consolidation of empirical evidence. Second, terminological ambiguity leads to divergent interpretations in policy design, undermining the effectiveness of innovation promotion and regional development programs. Finally, the absence of a unified theoretical framework prevents rigorous comparison across initiatives and consistent evaluation of their outcomes, limiting the extraction of general lessons and the formulation of strategic guidelines for these territories. These challenges are even greater for more recent conceptions, which encompass not only land parcels but also neighborhoods, districts, urban, peri-urban, and rural regions, and even entire cities—thus expanding the geographic and functional scope of these sites and raising the level of coordination required in their planning and management.

Against this backdrop, previous studies such as [

9,

10,

11,

12] have conducted systematic reviews to map this conceptual evolution and propose typologies, classifications, and frameworks associated with the terms under analysis. While providing relevant insights, these works have generally focused on a single concept—for instance, “innovation district” or “knowledge city”—and therefore do not adequately capture the thematic diversity or the cross-cutting areas that structure the development of knowledge territories. For example, few employed advanced analytical techniques, such as bibliometric methods, and nearly all restricted their scope to English-language publications and databases dominated by studies from the Global North. These limitations compromise the breadth and depth of an integrated understanding of this contemporary phenomenon.

To address these gaps and limitations, this study makes three main contributions. First, by systematically mapping diverse conceptions and employing bibliometric methods to measure knowledge production and link cross-cutting themes, it reduces the fragmentation of the literature and organizes it into a coherent framework. Secondly, it proposes knowledge territories as an umbrella concept that provides a consolidated theoretical reference, capable of incorporating contemporary terminological variations under a single analytical spectrum. This is a contribution towards minimizing ambiguity in the development and interpretation of public policies and enables comparison between initiatives. Furthermore, by making explicit the common characteristics and distinguishing the specific dimensions of each type of site, we provide conceptual tools to support policymakers and managers in designing innovation programs and coordinated actions—from the smaller scales (centers, districts and neighborhoods) to the level of more complex urban areas (cities and metropolitan regions).

Accordingly, with the aim of consolidating this literature, this study seeks to answer the following questions:

What is the state of the art on knowledge territories, considering the diversity of terms used—e.g., knowledge city, innovation area, innovation district, knowledge district, knowledge region, knowledge and innovation space, and knowledge and innovation environment?

Which conceptual, structural, or functional elements are shared across these different denominations, enabling their analysis under a common theoretical and analytical framework?

What are the main gaps, limitations, and biases identified in the existing literature, in research groups, collaboration networks, thematic, methodological, geographic, and linguistic terms?

To which extent are those territories concerned with contemporary and socioenvironmental problems - e.g. bioclimatic architecture, urban vitality, urban drainage, urban mobility, food production, sanitation, housing, place attachment, climate change, energy, participatory processes, social innovation, governance, and participatory management.

These questions are addressed in the following sections based on the results of a systematic literature review.

2. Methodological Procedures

The review was conducted in accordance with the criteria established by PRISMA. This protocol is widely recognized for ensuring transparency and comprehensiveness in reporting the methodological procedures adopted, covering aspects such as eligibility criteria, sources of information, search strategies, selection and data extraction processes, description of analyzed items, risk of bias assessment, synthesis methods, verification of publication bias, and analysis of the level of confidence in the results. All these elements are detailed below.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The review established clear guidelines for the selection of studies, based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only texts published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish were considered, in order to encompass both international and regional scientific production. In addition, preference was given to peer-reviewed publications, including original articles, case studies, literature reviews, framework proposals, and book chapters. Conversely, documents such as editorials, short reports, letters, conference papers, and books were excluded, as they did not meet the scope and comparability requirements of the review.

Another fundamental principle was the thematic focus. Only studies whose central object was related to the different denominations of knowledge and innovation territories—such as knowledge territory, knowledge and innovation space or environment, knowledge city or district, knowledge region, innovation area, and innovation district—were included. Therefore, studies addressing innovation in generic terms, without direct connection to these territories, as well as those using the aforementioned denominations merely as geographical delimitations to discuss other topics, were excluded. To illustrate this guideline, a study entitled “A study of the role of conflict resolution in micro and small enterprises in the innovation area of Salvador” would not be included, as it addresses innovation merely as context. By contrast, a text such as “Innovation area of Salvador: an overview of the contribution of conflict resolution” would be accepted, as it takes the innovation area as the central object of analysis.

These guidelines ensured consistency in the selection process and guaranteed that the included studies were conceptually and thematically aligned with the objectives of the review, enabling a robust and coherent comparative analysis.

2.2. Sources of Information and Search Strategy

Three international databases—Web of Science, Scopus, and Dimensions.ai—were consulted on February 23, 2025. The choice of Web of Science and Scopus is due not only to the tradition, quality, and rigor of their indexing processes but also to the reliability of the bibliographic references associated with each indexed article [

13]. However, considering the predominance of studies from developed countries in these databases, and with the aim of overcoming limitations identified in previous reviews, Dimensions was included, since according to [

14], it offers a broader coverage of publications from often underrepresented countries.

The search strategy consisted of using the terms “Knowledge and innovation space,” “Knowledge and innovation environment,” “Knowledge city,” “Knowledge territory,” “Knowledge district,” “Knowledge region,” “Innovation area,” and “Innovation district” in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, combined with the Boolean operator “OR.” The exact terms and translations used are described in

Supplementary Materials II – Protocol and search strategy. It is important to highlight that, intentionally, the search strategy did not include the terms “science parks,” “science and technology parks,” and other derivatives of “park.” This exclusion is justified by the fact that such concepts have conceptual, structural, and functional bases linked to less contemporary models, often associated with productive enclaves poorly integrated into the urban dynamic, which diverges from the analytical scope adopted in this review.

The query led to the identification of a total of 2,238 raw records (

Table 2).

2.3. Selection Process

The metadata of the articles retrieved from Web of Science, Scopus, and Dimensions.ai were organized with the support of the Rayyan.ai platform—a collaborative tool that assists in systematic review screening and the deduplication process, including artificial intelligence features for identifying redundant records. From the total of 2,238 imported records, 1,488 were classified as duplicates: 1,124 were automatically removed for showing more than 95% similarity, while 364 with lower similarity were manually analyzed by an independent reviewer, ensuring the maintenance of unique records linked to the same study. After this step, 1,361 valid records remained. Subsequently, conference papers (n = 248) and books (n = 35) were excluded, resulting in 1,078 records containing title and abstract, which advanced to the next stage of analysis.

The final selection was conducted by two independent reviewers, randomly chosen among the team members, to ensure the inclusion of relevant studies. To standardize and guide the screening process,

Supplementary Materials II – Selection Protocol: Titles and Abstracts was used. This protocol was structured in three phases: in the first, the reviewer was to identify the language of the study; in the second, to assess the type of publication; and in the third, to verify whether the focus was on knowledge territories in their different denominations. Texts that received a positive assessment (meeting inclusion criteria and not falling under exclusion criteria) from both reviewers were selected.

At the end of the title and abstract screening, 257 studies were selected for full-text retrieval. Of these, 19 were excluded for not being available in English, Spanish, or Portuguese, and 24 could not be accessed, even after attempts through libraries and requests sent to the authors via email and academic social networks. Thus, the number of eligible documents was reduced to 214 texts, available for data extraction.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Item Data

The selected texts were organized in the Taguette tool (app.taguette.org), which enables qualitative data extraction through codes (tags) linked to the interest themes. To guide the analysis, we held discussion meetings with a multidisciplinary team—comprising architects, urban planners, public administrators, political scientists, sociologists, philosophers, and experts in science and technology policy—in order to define which codes should be applied, that is, which data would be extracted and how they would be related to the different themes. The meetings included a preliminary bibliometric analysis and a set of ten texts randomly selected from the 214 identified. The outcome of these meetings was the definition of 37 codes, organized into structuring denominations, descriptive codes, and thematic/transversal codes.

The structuring denominations correspond to the recurrent terms in the literature used to refer to knowledge territories, covering: Knowledge and innovation space, Knowledge and innovation environment, Knowledge city, Knowledge territory, Knowledge district/precinct, Knowledge region, Innovation area, Innovation district/precinct, Innovation cluster, Knowledge-Based Urban Development, and other associated terms.

The descriptive codes focused on the methodological characteristics of the analyzed studies, including: cases cited or studied in the article, country and city of the case, method employed, spatial scale linked to the denomination, actors involved, and productive sector.

Finally, the thematic codes encompassed recurring dimensions in the debate on urban planning, innovation, and knowledge territories, such as: bioclimatic architecture, urban vitality, urban drainage, urban mobility, food production, sanitation, housing, place attachment, climate change, social sustainability, environmental sustainability, energy, healthy cities, economic sustainability, participatory processes, social innovation, negative effects of innovation, governance, and participatory management.

The 214 texts were divided among the 10 researchers involved. Thus, the data from each article were collected by one reviewer. To ensure normalization and accuracy of the data, a series of definitions for each code (

Supplementary Materials II – Data extraction protocol) and collection procedures were jointly established, as shown in

Table 3.

2.5. Method of Synthesis and Analysis of Results

The synthesis and analysis of the results were carried out using bibliometric analysis techniques and AI-assisted content analysis.

The bibliometric analysis was based on the 214 texts included after peer review, using data extracted from the consulted databases and supplemented with information obtained from OpenAlex or collected directly from the studies when not available in the original metadata. The compilation of these results was processed through the Bibliometrix library in R, which enables advanced bibliometric analyses. In parallel, we used the Semantic Scholar and OpenAlex APIs , integrated into VOSviewer software, to generate maps of the interaction networks among the producers and products of the analyzed corpus.

The qualitative data extracted were grouped by code sets. The denominations were analyzed preliminarily, and the literature’s bias between normative and descriptive concepts was identified. In this process, we selected only the descriptive concepts, which were presented in

Section 3 (Knowledge territories: an “umbrella” for polysemy). Normative concepts were used as the basis for discussions about the expected futures of these territories. This analysis was carried out considering the most recurrent convergences and divergences among the definitions of each denomination.

The descriptive data of cases and themes were analyzed with the support of Google NotebookLM. Recent studies have explored this tool [

15,

16] due to its potential to systematize unstructured data. However, as highlighted by [

17], its use requires caution, which guided our analytical process. For each theme, a specific notebook was created, into which only excerpts previously validated by the team were inserted, coded with record name, text number, and corresponding theme. This procedure ensured that inputs were restricted to relevant and validated information. In this way, NotebookLM was able to operate with greater precision, while the adopted organization favored efficiency in verifying the outputs generated from the applied prompts (

Supplementary Materials II — Prompt).

2.6. Assessment of Reported Bias

The results were evaluated by three independent reviewers from the team. The analysis indicated the possibility of bias stemming from the very scope of the included studies, since not all of the previously defined descriptive codes were necessarily present in each publication, particularly in case studies. Depending on the methodological approach and the dimensions prioritized, certain descriptors may not have been addressed, generating gaps in the synthesis. Moreover, in case studies, some dimensions appear only marginally.

2.7. Assessment of Confidence Level

The results of this study were evaluated by the research team and by a group of 08 independent reviewers, achieving an average confidence level of 91,6% in the evidence presented (

Supplementary Materials II - Assessment of confidence level).

3. Bibliometric Mapping of the Literature

Important theoretical pillars of the literature on knowledge territories emerged in the mid-2000s. Studies by Bugliarello [

18], Ergazakis [

19], and Yigitcanlar [

20] explored sets of ideas grounded in the conception of knowledge-based development strategies, with an explicit prospective orientation—that is, aimed at shaping desired forms of future development. However, it is important to mention theoretical antecedents such as [

21] and [

22], who began by observing the latent associations between territory and knowledge production. This debate can, in part, be attributed to the diffusion of the post-industrial economy perspective promoted by multilateral organizations, such as the OECD, across several countries, eg. Portugal with the Lisbon strategy [

23]. In this context, the academic community began to mobilize to study this new development logic and to propose strategies aligned with it. Building on these early works, a significant body of research has gradually consolidated over the years. In this study, we identified 214 works whose object and central focus are designated under the terms knowledge city, innovation area, innovation district, knowledge district, knowledge region, knowledge and innovation space, and knowledge and innovation environment.

Although there is no steady growth in production, the identified corpus exhibits the characteristics of an established body of literature (

Supplementary Materials I). This observation is reinforced by the results of the bibliometric authorship and journal analysis, interpreted through bibliometric analysis of Lotka’s Law and Bradford’s Law. The former indicates that most authors tend to publish only a few works, while a small number of authors account for a large share of publications. The latter shows that most publications are concentrated in a limited number of journals, whereas many journals include only a handful of articles on the subject. The confirmation of this pattern reinforces the consistency of the knowledge corpus under analysis. Conversely, the absence of such behavior would suggest the possibility of multiple distinct themes being grouped within the same set, or even an imbalance in the composition of the sample.

In this case, the identified corpus confirms this pattern. From the perspective of authorship, among the 400 mapped authors, 339 published only one study, 37 authors published two studies each, and 13 authors were responsible for three studies(

Supplementary Materials I). In addition, 11 authors published four or more studies (

Supplementary Materials I), with the following standing out: Yigitcanlar T (29 articles), Guaralda M (10), Ergazakis K (8), Metaxiotis K (8), Pancholi S (7), Piqué J (6), Carrillo F (5), Esmaeilpoorarabi N (5), Musterd S (5), Psarras J (5), and Erol I (4). In terms of journals, there is evidence of a central core of sources consisting of 11 journals, which concentrate 73 of the 214 articles analyzed. These are: International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development (17 articles), Journal of Knowledge Management (13), Cities (7), Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business (6), Land Use Policy (6), SSRN Electronic Journal (6), Built Environment (5), Expert Systems with Applications (4), Buildings (3), Journal of Place Management and Development (3), and Journal of Urban Technology (3)(

Supplementary Materials I). This result reinforces, on the one hand, the existence of shared conceptual elements among the different denominations of knowledge territories, which can be explored in an integrated way; on the other hand, it highlights the presence of biases in the analyzed literature, particularly regarding its geographical distribution.

The position of the countries associated with the studies reveals both similarities and contrasts (

Supplementary Materials I). Australia stands out as the leading country, both in terms of scientific production (57 studies) and impact (1,516 citations), a result explained by the affiliation of the field’s main authors with Australian institutions. However, when examining the position of other countries, some relevant discrepancies emerge. China ranks second in number of publications (31 articles) but only tenth in citations (56). The United Kingdom, in turn, accounts for 25 studies but ranks only eighth in impact, with 74 citations. The Netherlands, with 21 publications, holds the second position in citations, with 387. The most striking case is Greece: with just 9 studies, the country reached 199 citations, indicating a high relative impact of its output. This scenario can be partly explained by the nature of the studies, which may be more oriented toward regional realities, influencing both their international visibility and citation patterns. The data suggest that, except for Australia and the Netherlands, the other countries show low levels of international collaboration in the production process, in some cases being limited to only one or two co-authored studies with other countries (

Supplementary Materials I).

In addition, a discrepancy can be observed between the local citation score (LCS) and the global citation score (GCS). Of the 214 studies included in the corpus, only 44 registered an LCS, while 177 were cited in other sources of the global literature (GCS) (

Supplementary Materials I). This result may indicate the existence of subgroups or authors with a low level of engagement with the more consolidated literature.

Nevertheless, a set of recurring references can be identified within the corpus. Panel A (

Figure 1) highlights two distinct groups of co-cited references: one composed mainly of studies published before 2010 (in pink) and another consisting mostly of studies published after that period. However, these groups largely share the same authors and, in some cases, even the same research teams, as shown in Panel B (

Figure 1), which reinforces the hypothesis of the existence of thematic subgroups. This interpretation is further supported by the Bibliometric Coupling analysis (

Figure 2), which reveals a relative intellectual distance between the older studies (represented in purple shades) and the more recent ones (in yellowish tones).

This overview suggests the emergence of new pillars within the analyzed corpus, such as the works of Esmaeilpoorarabi [

24,

25]. The main difference between earlier references—such as [

18,

19,

20]—and more recent ones lies in the terminology and the focus of the object of study. While the former are dedicated to the conception of the “knowledge city,” the latter direct their attention towards “innovation districts.” Although there is interaction through co-authorships between representatives of both groups, as well as the use of shared references, a semantic broadening can be observed, which is not accompanied by significant transformations in the conceptual foundations of the literature—still grounded in the idea of Knowledge-Based Urban Development (KBUD). KBUD is conceived as a new form, approach, or development paradigm in the knowledge era, aimed at bringing economic prosperity, socio-spatial order, environmental sustainability, and good governance to territories [

26]—an aspect that becomes even more evident when qualitatively examining the content of these studies.

4. Knowledge Territories: an “Umbrella” for Polysemy

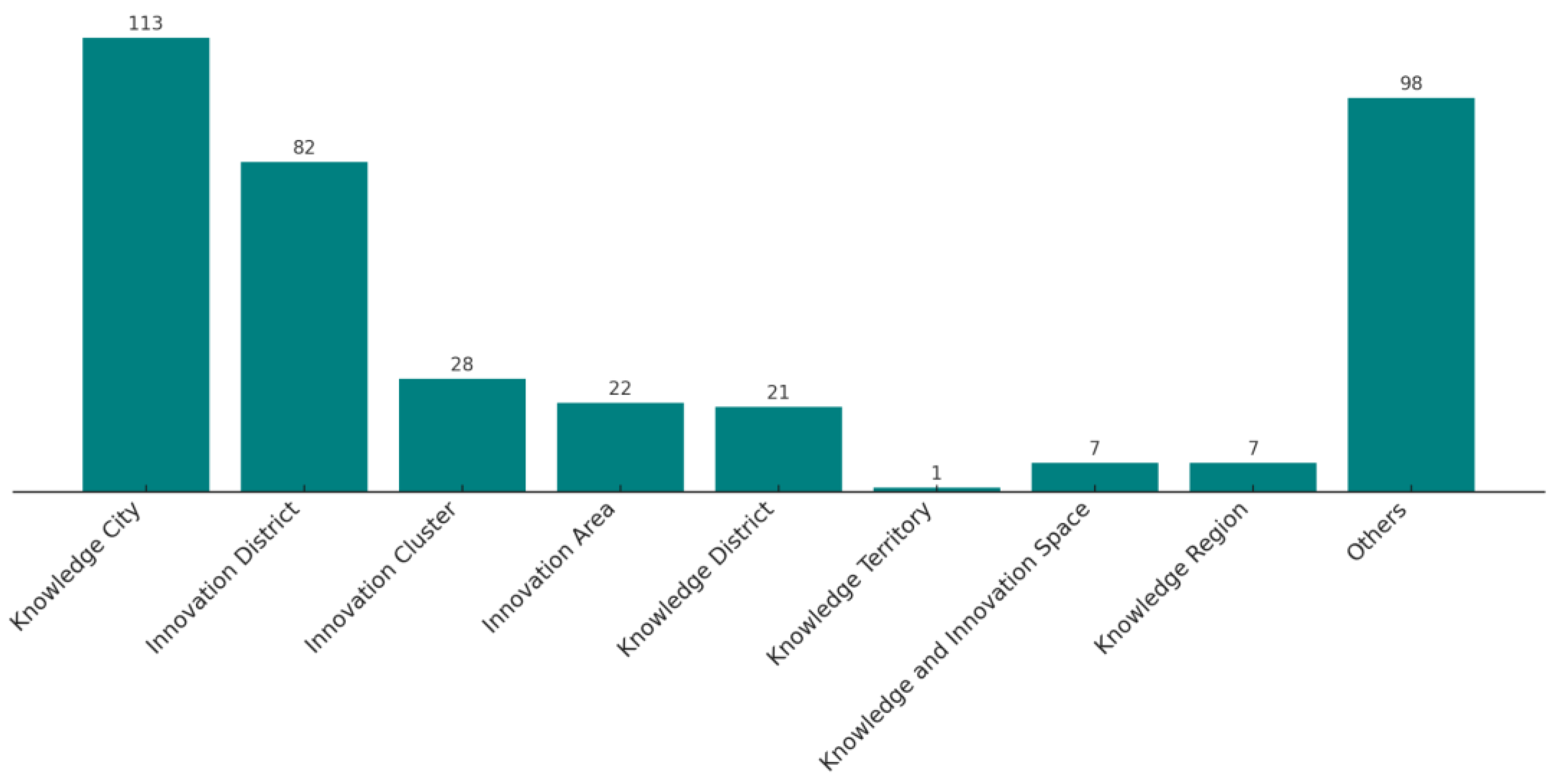

The literature makes explicit reference to several terms. However, the content analysis reveals the predominance of certain denominations within the corpus (

Figure 3). The term “knowledge city” is the most recurrent, appearing in 113 documents. Next, the concept of “innovation district” (82) also stands out, being referenced in many studies. Other categories with significant presence include “innovation cluster” (28), “innovation area” (22), and “knowledge district” (21). Less frequent are “knowledge and innovation space” (7), “knowledge region” (7), and “knowledge territory” (1). The category “others,” which encompasses conceptual variations and less consolidated denominations (Such as

creative hubs, technology parks, creative-knowledge hubs, district, experimental districts, industrial cluster, industrial district, knowledge-based area, knowledge-based cluster, knowledge-based innovation area, knowledge-based space, knowledge community precinct, knowledge hub.), appears in 98 documents. With the exception of those studies that only mention the object (without defining it), the ambiguity among denominations is acknowledged in all works that attempt to delimit the analyzed phenomenon.

In this regard, although a consolidated corpus exists on the phenomenon, the process of creating, developing, and validating theories is complex, since studies are subject to logical errors. At the same time, scientific practice itself promotes peer scrutiny, contributing to the continuous improvement of knowledge. We revisit this perspective—fundamental to research—because, in analyzing this corpus, we identified a recurring logical error in the construction and use of concepts. Specifically, we observed an overlap between what ought to be (normative) and what is (descriptive), which can lead to the naturalistic fallacy—deriving norms from facts—and the moralistic fallacy—presuming facts from norms. This likely occurred due to the ambiguities that motivated this study and are frequently cited in the corpus. The point here is not to highlight flaws in these studies, but rather to avoid falling into the same mistakes. To this end, in this section we present the descriptive definitions of these concepts.

The

Knowledge City is defined as a territory with intentionality, based on the knowledge economy, incorporating knowledge management processes, an emphasis on the human and cultural dimension, capital systems, and networks. Regarding intentionality, it is highlighted that these are cities purposefully designed to stimulate the creation, renewal, and circulation of knowledge [

20,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In this sense, the idea of continuous creation, sharing, evaluation, and updating of knowledge appears repeatedly [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Concerning its grounding in the knowledge economy, many descriptions associate the concept with KBUD, emphasizing education, science, technology, innovation, and human capital as drivers of development [

9,

32,

37,

38]. Other definitions emphasize, as part of the human and cultural dimension, the focus on learning, local values, quality of life, creativity, active citizenship, and the diversity of social actors [

26,

27,

37,

39,

40,

41]. More marginally, some definitions are associated with the concept of capital systems and with the need for adequate IT networks, ICTs, and urban infrastructure [

30,

42,

43,

44].

The

Innovation District is defined by deliberate planning and a clearly delimited geographic scale, the clustering of actors and activities, the physical and social environment, purpose, governance, and collaboration. They are frequently described as compact, accessible, mixed-use areas integrated into the urban fabric [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. In particular, the literature highlights the concentration of universities, research centers, startups, anchor firms, incubators, and accelerators, which foster proximity and collaboration [

25,

45,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. In addition, the role of urban design, spatial planning, and amenities (leisure, housing, commerce, transportation) is emphasized as key to attracting and retaining talent [

45,

46,

47,

57,

58]. Many definitions also link innovation districts to neighborhood revitalization, the transformation of industrial areas, economic value creation, and social inclusion [

54,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. Furthermore, across definitions, attention is given to complex arrangements involving public-private partnerships, triple or quadruple helix models, and reliance on collaborative networks [

46,

63,

64,

65]. These models (triple and quadruple helix) refer to knowledge production processes based on the interaction among universities, industry, and government — known as the triple helix — and, when society is incorporated, referred to as the quadruple helix. More recently, studies have also pointed to the quintuple helix, which includes the environment in these processes.

Knowledge and innovation spaces are described as specialized mixed-use areas, associated with KBUD [

66,

67]. These territories are developed drawing inspiration from New Urbanism, emphasizing permeability, accessibility, walkability, safety, and diversity of uses [

68]. In addition, they are presented as part of the conception of innovation districts [

69]. To some extent, they are described as territories that have undergone a conceptual evolution, transforming from introverted industrial districts into open mixed-use environments [

70]. In summary, knowledge and innovation spaces are specialized urban territories, with an emphasis on public space quality, social diversity, and mixed-use development, functioning as the spatial core of KBUD—essentially a synonym for innovation districts.

Innovation areas are described as an expanded urban ecosystem that goes beyond the economic dimension, encompassing social, urban, and educational impacts [

71]. They are structured around cooperation among universities, businesses, and government [

72] and operate within arrangements where the government defines land use, universities provide talent and entrepreneurship, and firms/investors absorb innovation [

73]. In particular, these territories seek to align the productive system, culture, and the natural environment [

72].

Knowledge clusters are described as concentrations of organizations whose production uses knowledge both as an input and as an output [

74]. In addition, they function as central places within an epistemic landscape, articulating local and global flows of information and innovation. These territories are regarded as engines of innovation and new industries, while simultaneously training specialists and generating publications and patents.

Innovation clusters are described as business agglomerations, based on creative industries, advanced technologies, and high-growth startups[

12,

73]. They are composed of diverse actors, adaptable to change, and capable of transforming regional contexts [

75]. They combine venture capital, incubators, accelerators, research parks, and professional services [

71], and can be “closed, semi-open, or open,” depending on the permeability of interactions[

76].

Despite their differences, these concepts are complementary and converge toward the current understanding that the diversity of actors and the spatial organization of innovation and knowledge constitute fundamental bases for socioeconomic and environmental development. Based on these elements, we propose the “umbrella” definition of

knowledge territories as

forms of spatial organization that bring together different actors in processes of production, circulation, and application of knowledge and innovation. In our review, we identified only one study [

77] that employs this term in Spanish, arguing that the knowledge territory constitutes a niche that also expresses the generalization of the Knowledge Society, in both its positive and negative aspects, which reinforces the relevance of the concept proposed here.

In this sense we employ the term territory as defined by Milton Santos [

78]: a concept that transcends spatial continuities to include intersectoral participation and management. [

78] (p.256) defines territories through what he calls horizontal and vertical relationships. While horizontalities are a result of spatial contiguities, verticalities refer to different forms of association that can be social, cultural or even economic processes, creating networks of places.

Given the inherent complexity of the phenomenon, the literature relies on case studies as a central methodology, complemented by exhaustive reviews of scientific production, the collection of primary data—through interviews and surveys—and documentary analysis. Quantitative methods, including different statistical techniques, are also common to characterize and evaluate the performance of knowledge territories. The application or development of theoretical and conceptual frameworks, as well as the undertaking of comparative analyses, likewise constitute recurring approaches. These methodologies are applied at different scales—from the city to the neighborhood, from the district to the cluster—and generate data and information on diverse thematic topics, such as climate change, governance, and social and environmental sustainability. It is from this diversity of scales and themes that the analytical panorama presented below is delineated.

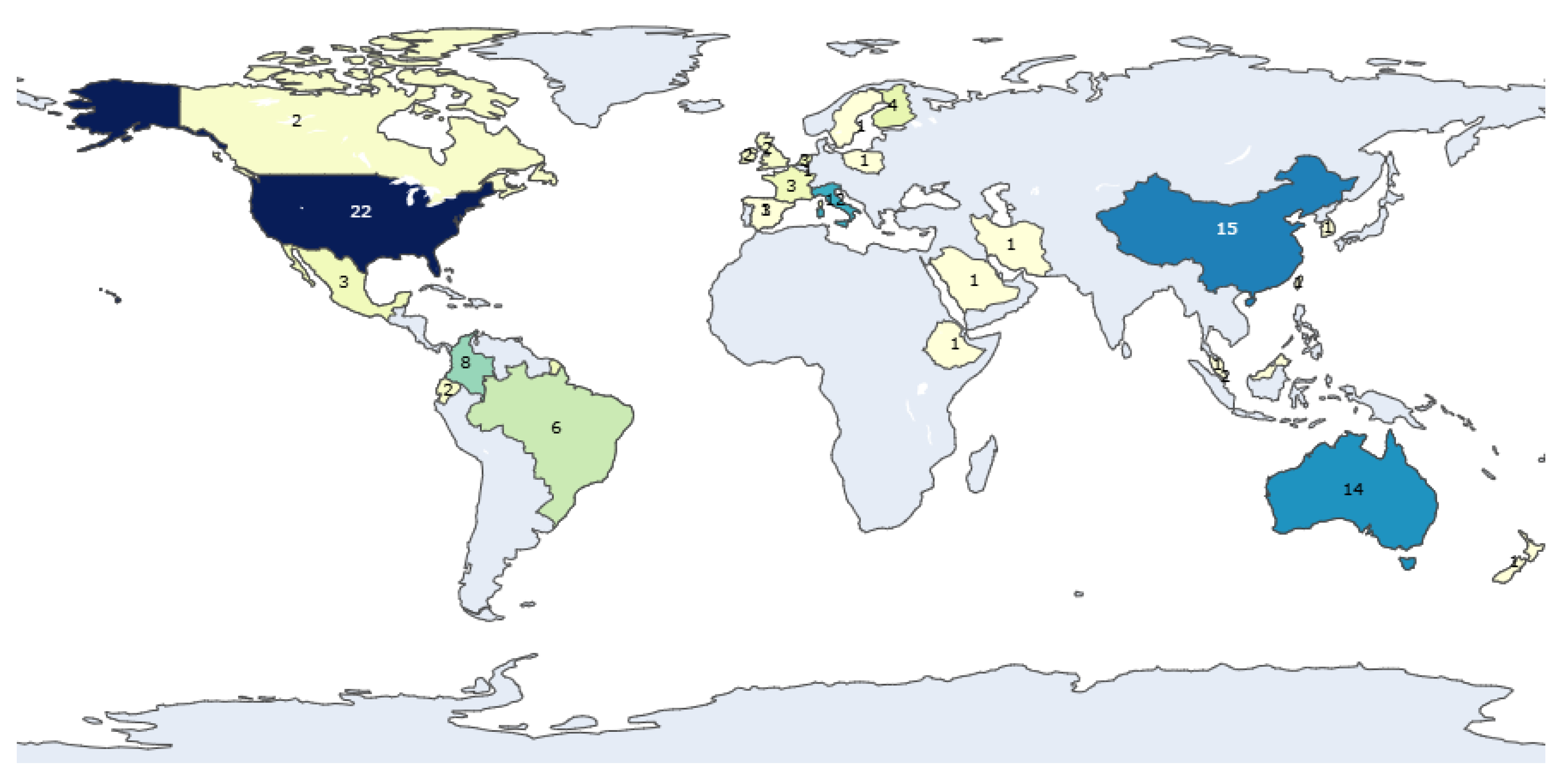

5. Case Studies of Knowledge Territories

We identified 114 cases studied in the corpus. The distribution of countries in the sample reveals a significant concentration in a few cases. The United States stands out, with 22 occurrences, corresponding to 19.3% of the total. Next, China accounts for 15 records (13.2%), Australia 14 (12.3%), and Italy 12 (10.5%). Colombia also has a notable presence, with 8 occurrences (7.0%). The remaining countries appear with lower frequencies, generally fewer than five records each, representing more modest shares of the total, as shown in

Figure 4.

This distribution highlights the predominance of a few countries,i.e., United States, China, Australia, and Italy, which together account for more than half of the observed cases. However, the number of cases in different parts of the world is greater than what has been covered in the literature and is distributed less evenly, as can be seen in the databases of international associations linked to the topic [

79].

The literature presents different scales for knowledge territories, which can be described in terms of administrative scales and geographic/spatial scales. In the case of administrative scales, the most prominent are Municipal/Local, State/Provincial, Federal/National, and Supranational levels. With respect to geographic and spatial scales, the main ones are presented in

Table 1.

In knowledge territories, the literature highlights the presence of a multifaceted productive fabric that combines traditional industries, high-tech sectors, and knowledge-intensive services. On one hand, industrial and manufacturing sectors remain important, ranging from classical activities—such as metallurgy, chemicals, food, beverages, glass, cement, steel, ceramics, and household appliances [

44,

77,

80,

81]—to specialized segments such as the aeronautical, automotive, aerospace, and mechatronics industries [

82,

83,

84], as well as advanced manufacturing supported by innovative materials and precision engineering [

84]. In parallel, the centrality of science, technology, and innovation sectors is evident, including nanotechnology, microelectronics [

18,

81,

85], artificial intelligence [

86], biotechnology [

84], biomedical and pharmaceutical industries [

80,

86], and green technologies [

87], which position these territories at the frontier of knowledge.

Another recurrent axis is information and communication technologies (ICTs), which encompass software, hardware, telecommunications [

44,

80,

83], digital games, and digital services [

86,

88], serving as foundations for the knowledge-based economy. Complementarily, knowledge territories also rely on knowledge-intensive services and creative industries, which include finance, law, consulting, accounting, advertising [

18,

84,

89], design [

51], visual arts, music, cinema, television, performing arts [

88,

90], tourism, hospitality, and retail [

84,

91], forming a symbolic economy that reinforces the identity and attractiveness of these spaces [

92].

Finally, the literature highlights the importance of strategic and infrastructural sectors, such as logistics [

84], energy [

85], science, and education [

87,

93]. This diversity of sectors shows that knowledge territories are not limited to hosting high-tech firms but constitute complex ecosystems, where the interaction among industry, services, science, creativity, and urban policies sustains their innovative dynamics.

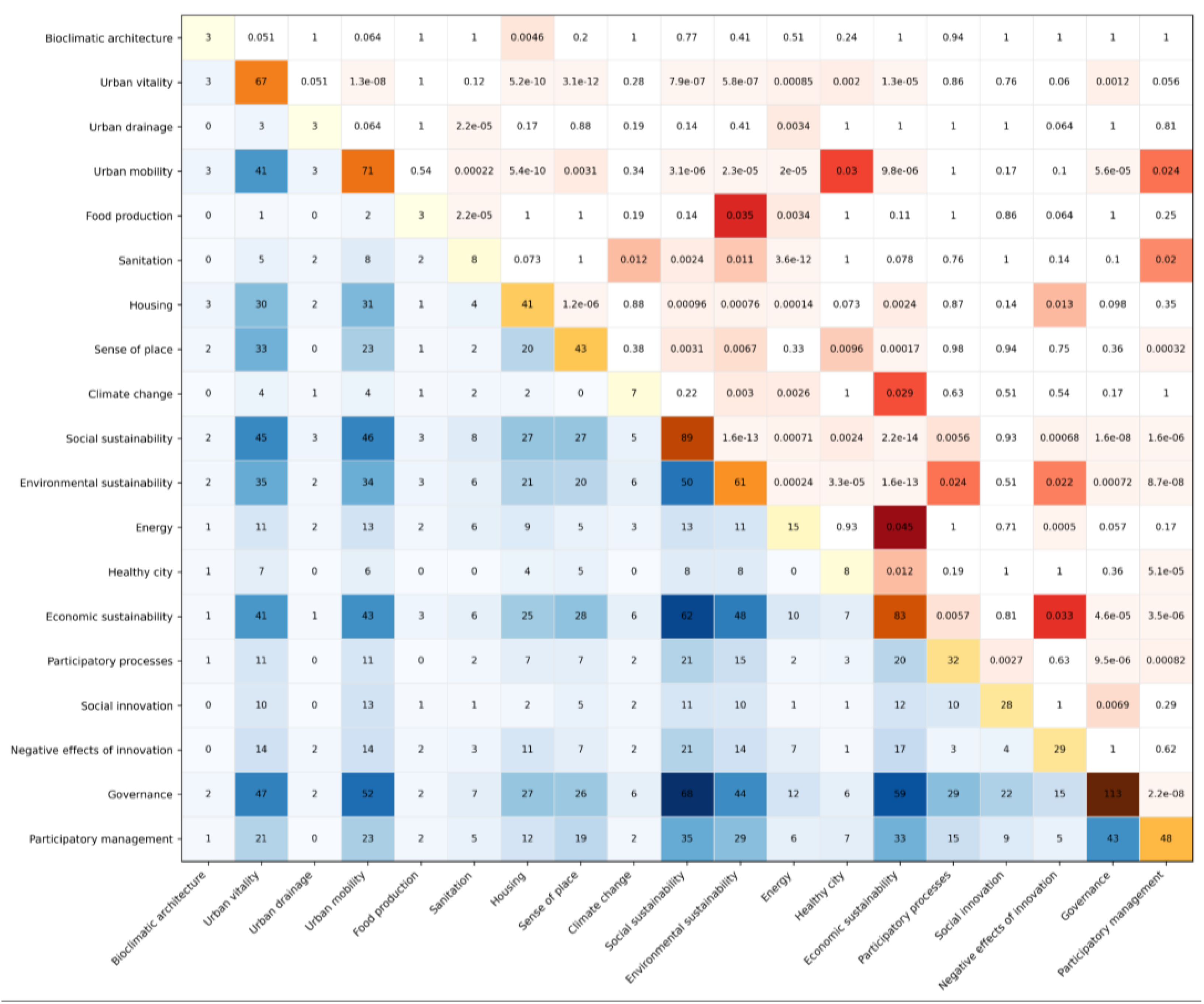

6. Topics Addressed

Figure 5 presents the distribution of the number of texts (N = 214) containing excerpts related to each analyzed thematic code. Governance is the most recurrent topic, appearing in 113 texts, which corresponds to about 53% of the total. Next, social sustainability (89 texts, 42%) and economic sustainability (83 texts, 39%) also stand out prominently, indicating that debates are strongly concentrated on institutional and structural aspects related to sustainable development.

In the intermediate range of occurrence are dimensions such as urban mobility (71 texts, 33%), urban vitality (67 texts, 31%), environmental sustainability (61 texts, 29%), participatory management (48 texts, 22%), sense of place (43 texts, 20%), and housing (41 texts, 19%).

When observing the co-occurrence of tags and the chi-square association between them (

Figure 5), we identified that governance, social sustainability, economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, urban mobility, urban vitality, and participatory management present the strongest associations, with statistical significance (p-value < 0.05). These results suggest that these dimensions are fundamental to understanding knowledge territories.

Among the less frequent topics are participatory processes (32 texts, 15%), negative effects of innovation (29 texts, 14%), social innovation (28 texts, 13%), and energy (15 texts, 7%). Even more marginal are healthy cities (8 texts, 4%), sanitation (8 texts, 4%), climate change (7 texts, 3%), as well as bioclimatic architecture, urban drainage, and food production, each present in only 3 texts (1%). This low representativeness indicates that, although relevant, such dimensions still appear only marginally in the analyzed set.

6.1. Governance and Sustainability as Central Pillars

Governance emerges as a recurring theme in the analyzed literature, standing out as a structuring axis for understanding knowledge territories. Alongside it, dimensions such as social, economic, and environmental sustainability also occupy a prominent position. These recurrences indicate that the debate on such territories is strongly anchored in institutional, normative, and strategic issues, within which sustainable development plays a central role.

6.1.1. Governance

Regarding governance, the literature highlights several common conceptual, structural, and functional elements. The pursuit of good governance stands out [

94,

95,

96], characterized by transparency, accountability, and participation [

53,

97,

98], supported by collaboration among actors [

63], citizen inclusion [

19,

38,

67], adaptive and flexible approaches [

85,

99], multi-level and multi-scale articulation, and the definition of a long-term strategic vision [

63,

100]. Governance is organized through institutional arrangements such as triple helix [

85] and quadruple helix models [

12], involving governments at different levels, universities and research institutions, the private sector, and civil society, as well as committees, agencies, and regulatory frameworks that provide normative and organizational support. In its functional dimension, governance manifests itself in the coordination and integration of actors and policies [

101,

102], in the enabling and facilitative role played by public and private institutions, in the formulation and implementation of policies, in financing and investment in initiatives, in the promotion of innovation and entrepreneurship, in knowledge management and circulation, in urban planning and development, and in the incorporation of social and environmental concerns aimed at cohesion and collective well-being [

98].

6.1.2. Social Sustainability

From a conceptual perspective, social sustainability is understood as part of a holistic vision that integrates economic and environmental dimensions [

19,

62,

84], with governance serving as an additional pillar in some cases [

26,

95]. Within this perspective, the promotion of life quality and well-being, equity and social inclusion, the strengthening of human and social capital, as well as tolerance and the appreciation of diversity, are fundamental principles that structure development strategies and shape the inclusive and vibrant character of knowledge cities [

25,

38,

103]. At the structural level, universities stand out as anchor institutions, able to go beyond their traditional teaching and research roles to assume positions as drivers of innovation [

94], economic development, and community engagement [

10,

104]. This structure is reinforced by physical urban environments that foster social interaction [

30], such as high-quality public spaces [

51], infrastructure networks [

37], and housing, which aim to promote social cohesion [

105,

106]. In addition, the establishment of collaborative networks among universities, citizens, businesses, policymakers, and communities [

94,

107], together with adequate governance frameworks and public policies, provides the necessary support to coordinate initiatives and ensure the social sustainability of the model [

51]. In its functional dimension, social sustainability materializes through the promotion of interaction and collaboration among different actors [

94,

108,

109], the attraction and retention of knowledge talent [

90,

110], the mitigation of negative impacts such as gentrification and inequality [

61,

68], the strengthening of skills and competencies through education and training [

95,

111], and the civic engagement of communities in planning and decision-making [

88,

112]. Complementarily, actions aim to foster openness and multiculturalism, valuing cultural, ethnic, and social diversity as central components of urban vitality [

90,

106].

6.1.3. Economic Sustainability

With regard to economic sustainability, from a conceptual perspective, the idea of the knowledge economy stands out, in which knowledge and innovation become the main drivers of added value creation [

60,

96,

113]. This perspective is connected to the pursuit of prosperity and economic growth, but it also incorporates a multidimensional vision of sustainability that integrates social and environmental concerns [

26,

88,

114]. Global competitiveness emerges as a strategic objective, alongside the promotion of endogenous development based on the valorization of local talent and assets [

89,

115]. Added to this is the commitment to inclusion and equity, which seeks to prevent economic gains from exacerbating inequalities [

19]. At the structural level, economic sustainability relies on institutional and infrastructural arrangements that support development. Among these, public–private partnerships stand out as central mechanisms of financing and management [

19,

116], as well as the role of universities and R&D centers as anchor institutions, and the creation of ecosystems and innovation districts that foster collaboration and entrepreneurship [

10,

89,

108]. This foundation is reinforced by investments in physical and digital infrastructure [

19,

25,

90], the diversification of financing mechanisms [

19,

25,

117,

118]—ranging from government subsidies to private and international funds—and the formation of a qualified human capital, considered a fundamental input to sustain competitiveness [

25,

42,

119]. In its functional dimension, economic sustainability is expressed in practices aimed at attracting and retaining talent, firms, and investment, as well as promoting the creation and dissemination of knowledge. Support for entrepreneurship and startups, urban regeneration, and the strengthening of collaborative networks among multiple actors are recurrent functions that ensure dynamism and innovation [

25,

120]. Government action appears as an indispensable component, whether through strategic policies or the orchestration of initiatives [

62,

85,

108]. Finally, improving quality of life and the urban environment is considered an essential function, both to attract and retain people and companies and to sustain productivity and well-being [

38,

90,

121].

6.1.4. Environmental Sustainability

The idea of environmental sustainability is inspired by the notion of meeting present needs without compromising those of future generations [

35,

121,

122], and is also associated with the triple bottom line approach [

62]. Environmental sustainability is anchored in physical and spatial infrastructures that materialize this vision [

29,

95,

123]. The presence of green spaces and urban parks, ecological belts, and water networks is highlighted as essential for environmental quality and the creation of living environments [

46,

87,

122]. Green buildings and infrastructures [

51], including eco-friendly technologies and certifications such as LEED [

74,

90], reinforce the need for energy and water efficiency [

87,

88]. Connections with natural surroundings—such as waterfronts, national parks, and historic sites—enhance the sense of place and value ecosystem services [

90]. The promotion of sustainable mobility, based on public transport, cycling, and walking[

51,

116,

118], completes this set by reducing environmental impacts and integrating urban and natural spaces.

6.2. Intermediate Dimensions and Topics Diversity

The intermediate-occurrence dimensions encompass themes that do not occupy the central position in the debate but nonetheless prove to be recurrent and relevant for understanding knowledge and innovation territories. What they share in common is a focus on concerns related to quality of life, spatial organization, and mechanisms of integration between actors and urban environments

6.2.1. Urban Mobility

Urban mobility is supported by robust public transport systems—metros, buses, trams, and railways—that constitute the core of intra- and inter-urban connectivity. Pedestrian- and cyclist-oriented infrastructures, such as high-quality sidewalks and integrated bike lanes, reinforce active mobility [

62,

102,

124], while road networks remain relevant for ensuring regional integration [

42,

90,

122]. Added to this is the presence of digital and technological infrastructure, with smart networks and innovative transport systems that enhance efficiency and connectivity [

90,

114,

125]. A compact urban form, combined with interconnected public spaces, parks, and green areas, creates conditions for greater urban permeability and social interaction [

68,

126]. Finally, airports and ports consolidate global connections, positioning innovation territories as strategic nodes in the international network of talent and investment [

42,

106].

6.2.2. Urban Vitality

Urban vitality is sustained by physical and institutional arrangements that promote integration and diversity of uses. Mixed-use development is highlighted as a central element, integrating residential, commercial, leisure, educational, and work functions within the same territory [

25,

90]. This foundation is strengthened by the presence of a wide range of amenities—cultural, recreational, green, everyday services, and collaborative workspaces—that expand opportunities for interaction and reinforce quality of life [

25,

32,

38,

51]. Accessibility and connectivity, supported by walkable environments and efficient public transport networks, together with urban density, function as structural factors that increase permeability, stimulate innovation, and reinforce the economic and social vitality of cities [

45,

102,

108].

6.2.3. Participatory Management

Participatory management is sustained by institutional and technological arrangements that enable active inclusion. Multisectoral committees and councils, such as the Knowledge City Committee, emerge as spaces for coordination, consultation, and deliberation, ensuring balanced representation of different actors [

19,

70,

80,

105]. Digital and technological platforms—from single portals to electronic voting tools, surveys, forums, and social networks—expand opportunities for engagement and transparency [

19,

114,

121], while physical meeting spaces—such as parks, squares, and civic centers—provide channels for face-to-face interaction [

51,

98,

112]. Participation is further strengthened by relational networks and partnerships among academic institutions, businesses, governments, and communities; by adaptive governance structures capable of operating across multiple levels and scales [

94]; and by innovative mechanisms such as living labs, which place citizens at the center of solution generation and testing [

63,

112]. Advanced, accessible, and inclusive communication infrastructures complete this foundation by ensuring the connectivity required for continuous interaction [

60,

98,

127].

6.2.4. Sense of Place

Place attachment is sustained by a physical and built environment that integrates architectural quality, functional diversity, and innovation. High-quality infrastructures and amenities—including schools, health centers, cultural facilities, and collaborative workspaces—form the basis of everyday urban life. Mixed-use development, combined with a diversified housing supply, promotes multifunctional and inclusive environments. Public and open spaces, such as squares, parks, and urban centers, act as catalysts for interaction, while integration with nature, high-quality digital connectivity, and the preservation of historical and cultural heritage reinforce local identity and urban continuity [

47,

83,

84,

105,

119,

128].

6.2.5. Housing

Housing is enabled by mixed-use and multifunctional models that integrate residential functions with commercial, cultural, leisure, educational, and service activities, often in high-density buildings with diversified ground-floor uses. Compact, walkable development, combined with urban density, fosters vitality and proximity between residences, workplaces, public transport, and urban amenities. Essential urban infrastructure—such as transport, energy, water supply, sewage, and digital connectivity—complements the physical structure required for everyday life. The typological diversity of housing, ranging from social housing [

39,

60,

105] to high-density apartments [

19,

25] and student housing [

89], expands the capacity to accommodate different social groups and occupation profiles.

6.3. Emerging and Low-Frequency Topics

Emerging and low-frequency topics represent dimensions that appear less frequently in the corpus but signal relevant concerns and trends for the future of knowledge and innovation territories. In general, these are themes that broaden the debate by incorporating critical aspects—such as inequalities and adverse effects—or by projecting new possibilities for urban and social development based on innovation, sustainability, and quality of life.

6.3.1. Participatory Processes

Participatory processes rely on arrangements that ensure diversity and breadth of voices. Structures such as committees and dedicated groups—exemplified by the Knowledge City Committee [

31] or forums such as U-Lab and U-Atelier [

129]—serve as spaces for coordination and consultation. Digital platforms, including electronic voting tools, online surveys, virtual forums, and e-governance portals [

19,

121], complement physical participation in community workshops, thematic events, and in-person roundtables [

93,

129]. In addition, integrative partnerships among municipal authorities, stakeholders, and citizens reinforce multisectoral articulation, while the incorporation of the community into quadruple helix models ensures that different social layers are represented in processes of innovation and urban development.

6.3.2. Diffuse Effects of Territorial Occupation

The “negative” spillovers of knowledge territories manifest in potential public–private partnerships that exacerbate certain inequalities in terms of land occupation and housing models [

61,

130,

131]. Speculative real estate development, driven by risk investments, favors land-use models—residential, touristic, or commercial—that result in gentrification and the displacement of local populations [

55,

118,

124,

132]. The design of exclusive environments, marked by elitized consumption patterns, symbolic architecture, and infrastructure aimed at attracting high-income groups, reinforces social exclusion [

131,

132]. At the same time, the impact of the knowledge economy and Industry 4.0 on the labor market generates contradictions: although it demands new qualifications, it also creates precarious conditions, with an expansion of lower-paid jobs and unequal labor practices [

56,

130,

132].

6.3.3. Social Innovation

Social innovation is grounded in social processes, ecosystems, and collaborative networks, in which social capital plays a strategic role as an asset generated through connections among individuals and communities [

30,

108,

133]. Multisectoral and multi-actor collaboration is another fundamental pillar, involving universities, government, the private sector, and communities, with academic institutions often acting as anchors that extend their role beyond research and education, connecting also to sociocultural networks and promoting the participation of individuals in the co-construction of innovation [

68,

103]. Additionally, knowledge infrastructure—e.g., public libraries and attractive urban services—supports both the production and dissemination of innovation [

33,

74].

6.3.4. Healthy Cities

Healthy cities are supported by qualified green and urban infrastructures that combine sustainability with leisure and social interaction, such as public parks, bike paths, running areas, and sports fields. Sustainable and integrated urban development—characterized by compactness, mixed use, and transit-oriented urban design—constitutes another key element, associated with reducing environmental impacts and improving quality of life. The quality and quantity of urban amenities, ranging from basic services to cultural and recreational spaces, complete this structural foundation, functioning as indispensable components for the livability and attractiveness of territories.

6.3.5. Sanitation

Sanitation is materialized in water supply and sewage treatment systems, which include the collection of wastewater and stormwater, associated with the goal of universalizing access to drinking water [

47,

130]. Waste management structures, such as collection and processing systems—including pneumatic technologies—complement this framework [

61]. More broadly, sanitation is integrated into a comprehensive urban infrastructure that connects essential transport and energy networks, and buildings to the functioning of the city, with planning also encompassing underground solutions for greater efficiency and integration [

61,

130]. Additionally, green spaces and environmental preservation units are incorporated as part of the sanitation structure, reinforcing the link between the urban landscape and nature [

32,

125].

6.3.6. Climate Change

The response to climate change is enabled by institutional arrangements and specific urban contexts. Governance, as well as national and local public policies play a decisive role, with target plans for emission reduction, incentives for low-carbon pilot zones, and multilateral agreements, as exemplified by initiatives in China [

116] and Barcelona [

97]. Monitoring and evaluation systems reinforce this foundation by enabling the measurement of energy consumption, emissions, and environmental performance in cities and districts [

116]. Sustainable urban planning, expressed in experiences such as the rise of eco-cities in China or the initiatives in Helsinki [

115,

116], is structured around accelerated urbanization and the integration between the natural and built environments. Collaborative research and innovation centers, such as those in Barcelona, Chicago, Medellín, and Seoul [

97,

115], strengthen this framework by connecting science, technology, society, and public policies around climate mitigation and urban sustainability.

6.3.7. Bioclimatic Architecture

Bioclimatic architecture is materialized in adaptive built forms that respond to local climatic conditions, often reinterpreting traditional elements—such as trellises, awnings, and screens—together with modern materials and technological solutions [

83]. The preservation and creation of green spaces play a fundamental role, ensuring the conservation of native trees and the development of large green areas that reinforce biodiversity and urban coexistence [

83]. In addition, the definition of appropriate scales and densities, such as medium-sized and low-impact housing, ensures a harmonious integration with the landscape and urban sustainability [

25,

76,

83].

6.3.8. Urban Drainage

Urban drainage is materialized in the fundamental components of the urban water system, integrating water, wastewater, and stormwater within a unified planning logic. Water management systems, conceived as technological and organizational arrangements, constitute key structures for operationalizing this integration. Underground galleries, frequently mentioned, represent multifunctional physical solutions that enable the transport, storage, and disposal of water, contributing to urban resilience. In addition, the preservation and management of the existing water system are conceived as integral parts of the structure to be protected and continuously monitored [

61,

130,

134].

6.3.9. Food Production

Food production is sustained by integrated value chains that seek to reduce costs and time between production and consumption through the proximity of farms to urban centers. This logic is reinforced by the need for full chain control to ensure traceability and safety. The efficient use of natural resources constitutes another structural pillar, associated with the adoption of technologies such as vertical farming and nutrient recycling practices. Different actors are mentioned, including women in the agricultural workforce, youth, local and international food companies, and consumers. The relational structure among these diverse actors constitutes a common element for analysis. In this context, infrastructure and technology emerge as foundations of modernization, incorporating everything from solar-based conservation systems to innovative structures that combine traditional and contemporary methods [

49,

60,

87].

7. Gaps, Discussions, and the Proposal of a Research Agenda

The analyzed literature reveals significant gaps in fundamental aspects necessary to understand knowledge and innovation territories, which can be seen as potential opportunities for increasing their contribution for solving pressing contemporary problems. One of the underexplored points is the relevance of societal participation in these processes, which is often treated as secondary or marginal, as evidenced by the small number of studies that address participatory processes. Moreover, the ambiguity among the different denominations used does not stem from their practical implementations—which present clear conceptual differences—but rather from attempts by some authors to emphasize underlying similarities and, based on specific results, generalize conclusions to other contexts.

Another noteworthy aspect is the absence of a consistent debate on the production, use, and distribution of knowledge. Such processes are often conceived as occurring “naturally” among individuals, requiring only the development of certain infrastructures and the concentration of people within the same territory, while disregarding the possibility of institutional induction or coordination. This view contrasts with critical analyses, such as those of Mazzucato [

135], who highlight the active role of the state in fostering innovation—from Silicon Valley to Chinese innovation districts—and suggest that such processes would hardly be sustainable without strategic state intervention. In this sense, it is not surprising that the literature also devotes marginal attention to themes such as participatory processes, the negative effects of innovation, and social innovation.

Similarly, the limited emphasis on topics such as energy, healthy cities, sanitation, climate change, bioclimatic architecture, urban drainage, and food production reinforces the perception that, although sustainability figures prominently in discourse, it appears more as an ontological and conceptual concern than as a concrete operational challenge. In other words, sustainability tends to be evoked as a principle but is rarely addressed in practical terms of implementation, monitoring, and impact.

Although the issue of scale is presented in the literature almost as a detail, its presence nonetheless reveals important descriptions of the different levels at which knowledge territories can materialize. This contribution is significant, since policymakers require clarity regarding the form and function of these territories to guide the development of their strategies. By indicating possible scales of action, even if secondarily, the literature provides practical insights for designing policies more attuned to local, regional, or national realities.

One point must be emphasized: the literature pays little attention to peripheral and semi-peripheral countries of the Global South, contexts marked by greater heterogeneity of actors, specific forms of social participation, and distinct interaction logics. In these settings, attempts at generalization—and particularly the application of frameworks developed in advanced economies—present significant limitations when confronted with evidence from peripheral contexts. These gaps should be further explored in future studies.

In this regard, there are major questions that need to be addressed. In particular, these questions are associated with the “how,” “what,” and “who.” For example: How can knowledge territories be developed in semi-peripheral and peripheral countries? What are the priorities in developing such territories? What constitutes a successful territory and what defines a failed one? How can the fourth helix (society) of the quadruple helix innovation model be engaged in practice? Who or what represents the fifth helix (environment) in the quintuple helix model at the practical level? These questions lead to reflections that move beyond ontology, resulting in practical answers to the constant challenges of developing such territories.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., M.N., S.S., M.E.S., I.G.S., C.B., L.G., M.V., and G.C.; Data curation, D.D.S.A. and M.N.; Formal analysis, D.D.S.A.; Funding acquisition, M.P.S., M.N., and G.C.; Investigation, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., M.N., S.S., M.E.S., I.G.S., C.B., L.G., M.V., and G.C.; Methodology, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., M.N., S.S., M.E.S., I.G.S., C.B., L.G., M.V., and G.C.; Project administration, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., and G.C.; Software, D.D.S.A. and M.N.; Supervision, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., and G.C.; Validation, D.D.S.A. and M.P.S.; Visualization, D.D.S.A., M.N., and S.S.; Writing—original draft, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., and S.S.; Writing—review & editing, D.D.S.A., M.P.S., M.N., S.S., M.E.S., I.G.S., C.B., L.G., M.V., and G.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by São Paulo Research Foundation, grant number 2025/25737-3, 2023/03301-3, 2021/03864-2, 2021/11962-4, 2024/23617-8 and 2024/07278-9, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), processo n. 311738/2022-2, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001 and Pró-reitoria de pesquisa da Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The database is in the supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used LM Notebook (Google) for the purposes of support analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- David, P.A.; Foray, D. Economic Fundamentals of the Knowledge Society. Policy futures in education 2003, 1, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Snellman, K. The Knowledge Economy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, G. The Structures and Prospects of Knowledge Society. Social Science Information 1997, 36, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Leydesdorff, L. Regional Development in the Knowledge-Based Economy: The Construction of Advantage. The journal of technology Transfer 2006, 31, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabe, T.; Abel, J.; Ross, A.; Stolarick, K. Knowledge in Cities. Urban Studies 2012, 49, 1179–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annerstedt, J. 14 Science Parks and High-Tech Clustering. International handbook on industrial policy 2006, 279. [Google Scholar]

- WORLD ALLIANCE FOR INNOVATION (WAINOVA). WAINOVA ATLAS of INNOVATION: Science/Technology/Research Parks and Business Incubators in the World.; WAINOVA, Ten Alps Publishing: Reino Unido, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bogucharskaya, A. The Role of Science Technology Parks in Creation of Networking Framework between Elements of National Innovation System and Business in Russia. 2018.

- Edvardsson, I.R.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Pancholi, S. Knowledge City Research and Practice under the Microscope: A Review of Empirical Findings. Knowledge Management Research & Practice 2016, 14, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, A.; Taskoh, A.K.; Nodooshan, S.G. The Required Specifications of a Fourth-Generation University to Shape Innovation District under Anchor Approach: A Meta-Synthesis Analysis Using Text Mining. International Journal of Innovation Science 2021, 13, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Adu-McVie, R.; Erol, I. How Can Contemporary Innovation Districts Be Classified? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, M.G.; Mamhoori, A.; Pilannejad, M. Exploring the Concept of Pardis Innovation Districts: Typology and Conceptual Model. Advances in Social Sciences and Management 2024, 2, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.; Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Large-Scale Comparison of Bibliographic Data Sources: Scopus, Web of Science, Dimensions, Crossref, and Microsoft Academic. Quantitative science studies 2021, 2, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, S.M.; Mokhtar, S.; Rahman, N.A.; Abdullah, K.; Rahmat, A.; Sarkawi, A.A.; Rahmat, A. Waqf Development and Management: A Systematic Literature Review of Best Practices, Challenges, and Strategies.; 2025; Vol. 3, pp. 9–15.

- Tan, J.R.; Ong, Y.T.; Fam, V.J.E.; Sinnathamby, A.; Ravindran, N.; Ng, Y.; Krishna, L.K.R. The Impact of Death and Caring for the Dying and Their Families on Surgeons-an AI Assisted Systematic Scoping Review. BMC surgery 2025, 25, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, R.; Greene, E.A.; Sumberg, L.; Weingrad, A.B. AI Tools in Academia: Evaluating NotebookLM as a Tool for Conducting Literature Reviews. Psychiatry 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugliarello, G. Urban Knowledge Parks, Knowledge Cities and Urban Sustainability. International Journal of Technology Management 2004, 28, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergazakis, K.; Metaxiotis, K.; Psarras, J.; Askounis, D. A Unified Methodological Approach for the Development of Knowledge Cities. Journal of Knowledge Management 2006, 10, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; O’Connor, K.; Westerman, C. The Making of Knowledge Cities: Melbourne’s Knowledge-Based Urban Development Experience. CITIES 2008, 25, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.G. Cities in Civilization: Culture, Innovation, and Urban Order. (No Title), 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M.; Hall, P. Technopoles of the World: The Making of Twenty-First-Century Industrial Complexes. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship 1994.

- European Council Lisbon European Council. 23 and 24 March. Retrieved March 2000, 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Evaluating Place Quality in Innovation Districts: A Delphic Hierarchy Process Approach. LAND USE POLICY 2018, 76, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does Place Quality Matter for Innovation Districts? Determining the Essential Place Characteristics from Brisbane’s Knowledge Precincts. LAND USE POLICY 2018, 79, 734–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzi, C.; Ivaldi, E.; Musso, E.; Penco, L. The Role of Knowledge City Features in Nurturing Entrepreneurship: Evidence from EU Cities. In Urban studies and entrepreneurship; Springer, 2019; pp. 53–76.

- Ergazakis, K.; Metaxiotis, K.; Psarras, J. Towards Knowledge Cities: Conceptual Analysis and Success Stories. Journal of Knowledge Management 2004, 8, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, R.; Pasher, E. Innovation Engines for Knowledge Cities: An Innovation Ecology Perspective. Journal of Knowledge Management 2004, 8, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Position Paper: Benchmarking the Performance of Global and Emerging Knowledge Cities. Expert Sys Appl 2014, 41, 4680–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvinsson, L. Knowledge City Stockholm @ the Forefront. In Entrepreneurial Renaissance; 2017; pp. 101–112.

- Metaxiotis, K.; Ergazakis, K. Exploring Stakeholder Knowledge Partnerships in a Knowledge City: A Conceptual Model. Journal of Knowledge Management 2008, 12, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, E.; Filho, N.C.; Lezana, Á.G.R. DE VALE DO SILÍCIO BRASILEIRO À CIDADE DO CONHECIMENTO: IMPLANTAÇÃO DO CONCEITO DE CIDADE DO CONHECIMENTO EM FLORIANÓPOLIS. South American Development Society Journal 2019, 5, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, W.G. Informational Cities: Analysis and Construction of Cities in the Knowledge Society. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 2011, 62, 963–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.K.D. Developing Knowledge Cities. In Theme Cities: Solutions for Urban Problems; 2015; pp. 381–424.

- Wang, X.; Lihua, R. Examining Knowledge Management Factors in the Creation of New City. Journal of Technology Management in China 2006, 1, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, S.; Payal, R.; Carrillo, F.J. Knowledge Village Capital Framework in the Indian Context. International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 2013, 4, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notari, D.L.; Battistelo, R.; Molin, L.W.; de Ávila e Silva, S.; Fachinelli, A.C. APLICAÇÃO WEB PARA INDICADORES DE CIDADES DO CONHECIMENTO | WEB APPLICATION FOR KNOWLEDGE CITIES INDICATORS. Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Inovação (Brazilian Journal of Management & Innovation) 2020, 7, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, A.; Ivaldi, E.; Bartiromo, M. The History and Evolution of Cities in Terms of the Sustainability and Knowledge-Based Economy Sectors. In Smart Sustainable Cities and Knowledge-Based Economy; 2023; pp. 1–17.

- Pique, J.; Miralles, F.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J. Areas of Innovation in Cities: The Evolution of 22@Barcelona. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF KNOWLEDGE-BASED DEVELOPMENT 2019, 10, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijer, A.C.D.; Magdaniel, F.T.J.C. The University Campus as a Knowledge City: Exploring Models and Strategic Choices. International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 2012, 3, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampangi, R.V.; Ritter, W.; Vighnesh, N.V.; Ray, H.C.A. The Knowledge City Index: A Case Study of Mysore. International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 2012, 3, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penco, L.; Ivaldi, E.; Bruzzi, C.; Musso, E. Knowledge-Based Urban Environments and Entrepreneurship: Inside EU Cities. Cities 2020, 96, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Lzushi, H.; Prokop, D.; Thompson, P. Regional Evolution and Waves of Growth: A Knowledge-Based Perspective. EXPERT SYSTEMS WITH APPLICATIONS 2014, 41, 5573–5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzon, F.; Fachinelli, A.C.; Zanotto, M.P.; Montaña, M.P.; Silva, E.F. da O Desenvolvimento Baseado Em Conhecimento No Contexto Das Cidades: Uma Análise Do Caso de Monterrey. Desenvolvimento em Questão 2019, 17, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, J. Innovation Districts and the Physical Environment of Knowledge-Based Economic Development. In Routledge Companion to Creativity and the Built Environment; 2024; pp. 491–503.

- De Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Taeihagh, A. Smart City Development as Spatial Manifestations of 21st Century Capitalism. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 202, 123299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão, C.M.; Ariente, E.A.; Marinho, M.E. Os Distritos de Inovação No Ordenamento Jurídico Brasileiro: Desafios, Modelos e Regulamentação. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, S.; Zandiatashbar, A. Does Urban Form Matter for Innovation Productivity? A National Multi-Level Study of the Association between Neighbourhood Innovation Capacity and Urban Sprawl. Urban Studies 2018, 56, 1576–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesabathuni, K.; Kraemer, K.; Askari, S.; Lingala, S.; Bajoria, M.; Bloem, M.; Gavin-Smith, B.; Hamirani, H.; Kumari, P.; Milan, A.; et al. Food Systems Innovation Hubs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation; 2023; pp. 455–468.

- Kayanan, C.M. A Critique of Innovation Districts: Entrepreneurial Living and the Burden of Shouldering Urban Development. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2021, 54, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]