1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have made substantial advances in natural language understanding and generation across diverse tasks. However, their practical use is limited by a persistent tendency to produce hallucinations—outputs that may be fluent and coherent yet factually incorrect or semantically implausible.

To address the challenge of detecting unsupported or fabricated model outputs, a wide range of hallucination detection techniques have been proposed (Huang et al., 2025). Existing approaches are commonly grouped into white-box, gray-box, and black-box categories. White-box methods leverage internal model representations or intermediate activation patterns to identify factual inconsistencies (Azaria & Mitchell, 2023; Su et al., 2024). Although these approaches achieve high precision by directly accessing the model’s internal states, they are tightly coupled to particular architectures and are therefore difficult to generalize across models. Gray-box methods exploit intermediate signals such as token-level probabilities or entropy profiles (Varshney et al., 2023). However, such signals are often imperfect proxies for factual correctness, especially in open-ended generation scenarios where low-probability outputs may still be true and high-probability outputs may be confidently incorrect. Black-box methods, which rely solely on generated text, offer the greatest generality but also face substantial challenges (Heo et al., 2025). Approaches that depend on external knowledge bases can perform well in closed-domain tasks, yet their coverage limitations render them unreliable for open-domain reasoning (Kossen et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2025). Other strategies based on heuristics—such as self-consistency or majority voting among multiple model samples—frequently struggle to uncover hallucinations that remain linguistically fluent and semantically coherent despite being factually wrong (Galitsky 2021).

Motivated by these limitations, we introduce a neuro-symbolic, abductive approach to hallucination detection that complements existing black-box methods. Rather than relying on internal activations, probability signals, or external fact databases, the abductive framework treats each model-generated explanation as a hypothesis whose validity must be tested against a set of alternative explanations generated through counter-abduction. In this view, hallucination corresponds to the failure of the model’s preferred explanation to withstand competition from rival hypotheses that provide stronger explanatory support or fewer inconsistencies. By operationalizing hallucination as defeat under counter-abductive challenge, this approach uses structured reasoning—rather than factual lookup or probabilistic heuristics—to detect unsupported premises, hidden contradictions, and gaps in causal structure. Because abduction operates solely on the model’s output and does not depend on model internals or curated knowledge bases, it provides a robust black-box alternative capable of identifying subtle, high-fluency hallucinations that evade existing detection frameworks.

Example: Hallucination ≈ Abductive failure + Counter-abductive defeat

For the query “who are grandmothers of Russian poet Pushkin” YandexGPT hallucinates with

H0:

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin had two grandmothers — one on his father’s side and one on his mother’s side.

Maria Alekseyevna Ganibalkova (née Pushkina) (1745–1818) — grandmother on his father’s side.

Olga Vasilyevna Cherkasova (née Mineeva) (1737–1802) |

The correct answer is:

Paternal Grandmother: Olga Vasilyevna Chicherina)

Maternal Grandmother: Maria Alekseevna Pushkina / Hannibal |

Abduction begins with a simple question:

Is there any hypothesis H such that, if H were true, the model’s output would be a coherent explanation of the evidence and background knowledge?

Crucially:

The first names and patronymics (Maria Alekseyevna, Olga Vasilyevna) are correct for Pushkin’s maternal and paternal lines.

The surnames (Ganibalkova, Cherkasova, Mineeva) are completely fabricated and do not appear in any genealogical sources.

Abduction now tries to answer:

“Given the genealogical record of Pushkin’s family, can we find any consistent hypothesis HHH that makes these names plausible grandmothers?”

One attempts to build a hypothesis that would make the LLM’s answer consistent with KB:

H₀: “Ganibalkova” and “Cherkasova” are alternate or undocumented surnames for Pushkin’s actual grandmothers.

Abduction attempts to see if H₀ is viable:

→ No evidence exists.

→ No record exists.

Contribution

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically demonstrate how abductive reasoning can be used to identify and correct hallucinations in large language models. We show that abduction provides a principled mechanism for hypothesizing and testing missing premises, allowing the system to detect when an LLM’s answer relies on unsupported or logically inconsistent assumptions. By integrating counter-abduction and discourse-weighted validation, our approach further exposes weak or spurious reasoning chains that typical retrieval-augmented or likelihood-based methods fail to catch. This establishes abduction as a powerful and generalizable framework for enhancing LLM factuality, interpretability, and robustness.

2. Deduction, Induction, and Abduction: Peirce’s Triadic Framework of Reasoning

Charles S. Peirce (1878; 1903) identified three fundamental modes of inference—deduction, induction, and abduction—that together constitute the foundation of human reasoning and scientific discovery. These reasoning forms differ in their epistemic orientation, logical direction, and ampliative strength (adds new information not contained in the premises). Peirce emphasized that deduction is non-ampliative and certain, while both induction and abduction are ampliative and uncertain, expanding knowledge beyond what is explicitly contained in the premises.

Deduction operates by applying general rules to specific cases to derive necessary conclusions. It preserves truth but does not introduce new information: if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. Deductive reasoning thus provides logical certainty but no epistemic novelty. Example: all metals expand when heated. Iron is a metal. Therefore, iron expands when heated.

Induction, by contrast, generalizes from specific instances to formulate general laws or statistical regularities. It infers generality from repetition: from observing many cases of a phenomenon, one concludes that it holds universally or probabilistically. Inductive inference is inherently uncertain and probabilistic—its strength depends on the representativeness and size of the observed sample.Example: Iron, copper, and aluminum all expand when heated. Therefore, all metals expand when heated.

Abduction—sometimes called inference to the best explanation—reverses this direction of reasoning. It begins with an observed or surprising fact and seeks the most plausible hypothesis that could account for it. Abduction is therefore explanatory and hypothetical in nature: it introduces a new conceptual assumption that, if true, would make the observed fact intelligible.

Example: The lawn is wet. If it had rained last night, the lawn would be wet. Therefore, it probably rained last night.

Peirce maintained that induction and abduction are irreducible to one another, despite both being ampliative. Their irreducibility lies in their distinct epistemic roles within inquiry. Abduction functions as the logic of discovery, generating explanatory hypotheses to make sense of observations. Induction functions as the logic of verification, evaluating the empirical adequacy of those hypotheses through repeated testing. Deduction mediates between the two, deriving predictions from the abductively generated hypotheses for inductive testing.

This cyclical relationship—abduction → deduction → induction—constitutes what Peirce regarded as the

complete logic of scientific inquiry. In modern contexts such as abductive logic programming

, probabilistic reasoning, and neuro-symbolic AI

, this triad continues to serve as a conceptual framework for balancing hypothesis generation, logical inference, and empirical validation (

Table 1)

According to Schurz (2021) a family of abductive inferences has the following schema in common:

General pattern of abduction:

Premise 1: A (singular or general) fact E that is in need of explanation.

Premise 2: An epistemic background system S, which implies for a hypothesis H that H is a sufficiently plausible explanation for E.

Abductive conjecture: H is true.

|

The epistemic background system usually contains several possible hypotheses, H1,…Hn, which potentially explain the given evidence E, and the abductive inference selects the most plausible hypothesis among them. In this sense, Harman (1965) transformed Peirce’s concept of abduction into the schema of Inference to the best explanation (Lipton 2004).

3. Abduction as a Structural Corrective Layer for Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting has become a dominant strategy for eliciting multi-step reasoning from LLMs. By encouraging models to articulate intermediate steps, CoT aims to expose the latent reasoning trajectory behind a prediction (Zhong et al 2025). However, numerous empirical analyses suggest that CoT outputs often reflect post-hoc narratives rather than veridical reasoning traces. Because CoT unfolds autoregressively, each step is strongly influenced by the preceding linguistic surface form rather than by an internal, constraint-driven reasoning structure. This generates characteristic failure modes: invented premises, circular justifications, incoherent jumps between steps, and a high degree of variance under paraphrase. As a result, CoT explanations may be fluent and plausible but lack global coherence or factual grounding.

Abductive reasoning provides a natural remedy for these limitations because it is explicitly designed to construct the best available explanation for a set of observations under incomplete information. Unlike deduction, which propagates truth forward from known rules, or induction, which generalizes from samples, abduction seeks hypotheses that make an observation set minimally surprising. When integrated with LLMs, abduction can serve as a structural corrective layer that aligns free-form CoT text with formal explanatory constraints. The goal is not merely to post-verify LLM output but to reshape the generative trajectory itself, yielding reasoning paths that are coherent, defeasible, and governed by explicit rules.

In a neuro-symbolic pipeline, the role of abduction is to constrain the model's reasoning space, reveal implicit assumptions, and ensure that the chain as a whole satisfies the explanatory minimality principles characteristic of abductive logic programming and related frameworks (e.g., probabilistic logic programming, argumentation-based abduction, and paraconsistent abduction). The resulting system treats CoT not as a static artifact but as a dynamic structure subject to revision, hypothesis insertion, and consistency checking. This greatly mitigates classical CoT hallucinations, particularly those involving unjustified intermediate premises.

LLMs exhibit several well-documented weaknesses in generating extended reasoning chains:

Local coherence without global consistency. Autoregressive generation ensures that each step is locally plausible, but the chain as a whole often lacks a unifying explanatory structure. This makes even long chains susceptible to hidden contradictions.

Narrative drift. The model may start with a plausible explanation but gradually drifts toward irrelevant or speculative content, especially when confronted with ambiguous or incomplete premises.

Invented premises and implicit leaps. Because LLMs are rewarded for fluent continuations, they may introduce explanatory elements that have no grounding in the problem context.

Inability to retract or revise past steps. CoT is monotonic: once a step is generated, the model rarely revises it when new evidence appears.

Lack of minimality. CoT chains often include redundant or extraneous content that weakens verifiability and expands the space for hallucination.

These deficiencies reflect the absence of a symbolic structure guiding the explanation. They are symptoms of the “language-model fallacy”: the assumption that linguistic plausibility implies logical validity. Abduction directly targets these pathologies.

3.1. Abduction as a Missing-Premise Engine

One of the most powerful contributions of abduction to CoT reasoning is its ability to identify and supply missing premises. If the LLM asserts a conclusion for which no supporting evidence exists, the abductive engine detects the explanatory gap and suggests minimal hypothesis candidates to fill it. Because the goal in abduction is to construct the best available explanation rather than an arbitrary one, the resulting hypotheses must satisfy structural constraints: consistency with the domain theory, minimal additions, and coherence with all observations.

In practice, this mechanism serves two complementary purposes. First, it prevents the LLM from inventing arbitrary premises, because only hypotheses justified by the symbolic knowledge base are admissible. Second, it allows an LLM to maintain explanatory completeness even when the input is under-specified. Rather than hallucinating supporting details, the LLM can explicitly acknowledge abductive hypotheses, yielding transparent explanations that distinguish between observed facts and inferred assumptions.

This missing-premise correction is particularly valuable in domains such as medical reasoning, legal argumentation, or engineering diagnostics, where unjustified intermediate steps pose significant risks. The integration ensures that all steps in a CoT chain are grounded in either evidence or structured hypotheses.

3.2. Global Coherence Enforcement and Defeasibility

Whereas CoT operates locally, abduction imposes global coherence. An abductive solver evaluates the entire chain as a unified explanation: all steps must jointly account for the observed evidence and must not introduce contradictions. This shifts the verification problem from a linear inspection of transitions to a constraint-satisfaction problem over the whole chain.

The outcome is a substantial reduction in common CoT error categories. Circular reasoning becomes detectable when the chain contains no true explanatory base. Inconsistencies are exposed when hypotheses contradict established background rules. Moreover, the chain can be evaluated under multiple candidate abductive explanations, allowing the system to select the one with the lowest explanatory cost.

The global enforcement makes CoT suitable for integration with probabilistic logic scoring, weighted abductive frameworks, or discourse-aware logical verifiers. In particular, rhetorical structure theory (RST) can be used to weight the importance of CoT segments, allowing nucleus content to be treated as central evidence and satellite content as context. This enables abductive evaluation to be sensitive to discourse salience, improving robustness for long chains.

Abduction is inherently defeasible: hypotheses remain valid only until contradicted by new evidence. This property introduces non-monotonic reasoning into CoT generation. When new information renders a previously accepted step invalid, the system can revise the chain, retracting or modifying steps as needed.

In a neuro-symbolic architecture, this revision can be implemented as a feedback loop:

The LLM generates an initial CoT chain.

The abductive engine tests it for consistency.

Violations trigger targeted requests for revision, hypothesis insertion, or alternative explanations.

The LLM regenerates corrected steps under abductive constraints.

This process transforms CoT from a static output into an iteratively refined reasoning structure. The ability to revise previous steps directly counters a major weakness of current CoT approaches and aligns more closely with human reasoning-with-revision.

CoT typically expresses reasoning as a single narrative thread. Abduction naturally supports contrastive reasoning: why explanation A is preferable to B. This allows the system to articulate “why this and not that,” which significantly enhances interpretability. By generating multiple competing abductive hypotheses, the system can present a ranked set of possible reasoning trajectories rather than a single brittle chain.

For complex reasoning domains—clinical diagnosis, regulatory compliance, legal argumentation—contrastive abductive CoT provides a richer and more trustworthy reasoning interface. Importantly, contrastive explanations expose the structure of the hypothesis space, something LLMs typically hide behind fluent surface text.

3.3. Minimality as a Regularizer for CoT

Abductive models enforce minimality: explanations should contain no unnecessary assumptions. This principle acts as a structural regularizer on CoT, pruning verbose or extraneous content and discouraging speculative detours. Minimality also makes verification more tractable because the reasoning chain becomes closer to a canonical explanation.

Moreover, minimality reduces one of the main sources of hallucination in CoT systems: the inclusion of tangential premises or loosely associated facts. A minimal abductive explanation is not only easier to inspect but also more robust to adversarial perturbations and paraphrased prompts.

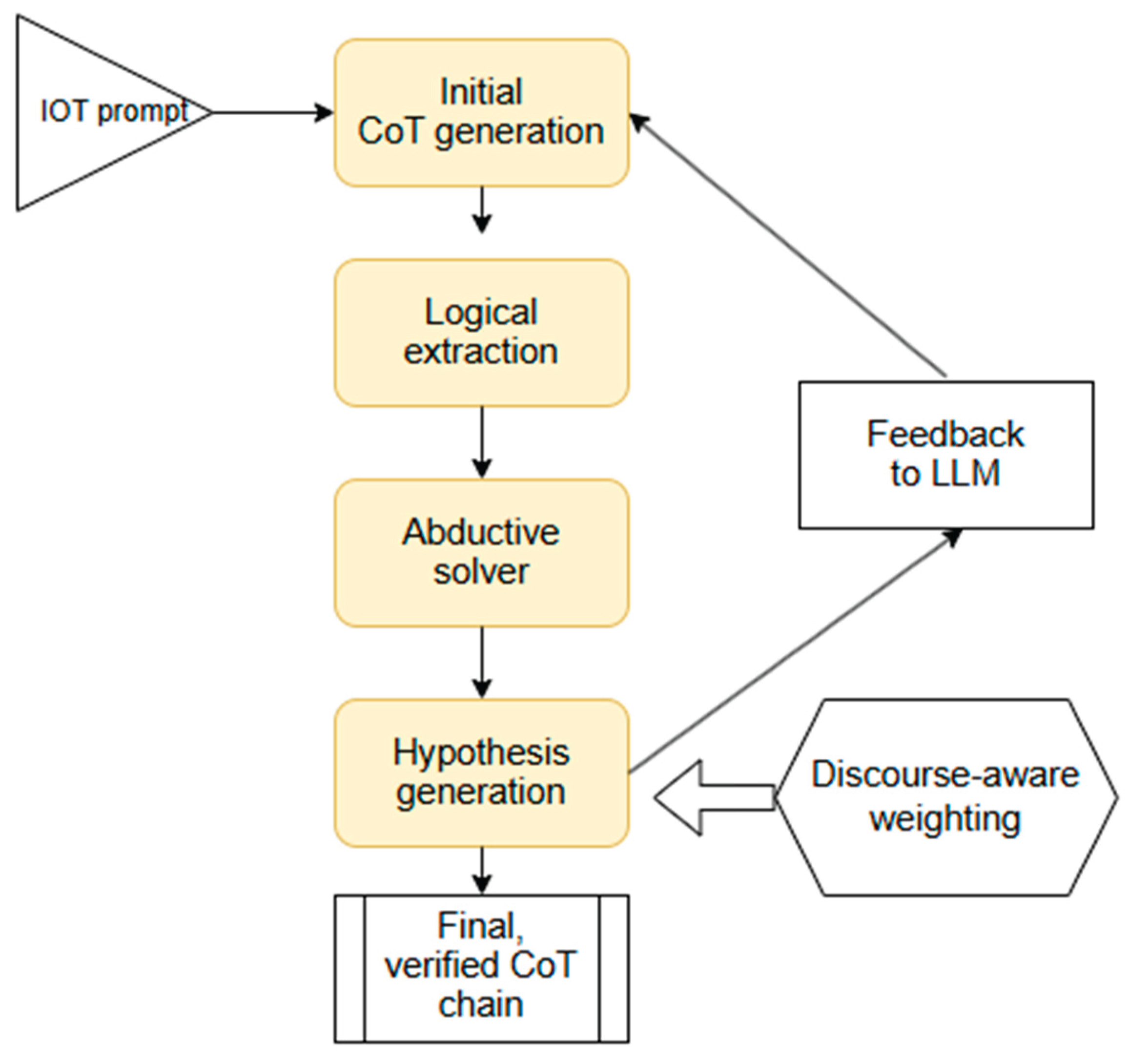

A coherent architecture for Abductive CoT emerges from combining these elements (

Figure 1):

Initial CoT generation by the LLM.

Logical extraction converting text into predicates or defeasible rules.

Abductive solver evaluates consistency, minimality, and coherence.

Hypothesis generation to fill explanatory gaps.

Feedback to LLM prompting revision or alternative reasoning paths.

Discourse-aware weighting using RST to distinguish central from peripheral content.

Final, verified CoT chain that satisfies explanatory constraints.

This loop is compatible with multiple logical formalisms, including probabilistic abduction, argumentation-based abduction, and paraconsistent abductive reasoning—allowing different degrees of uncertainty, conflict tolerance, and rule expressiveness. The core advantage is that the LLM no longer bears the full burden of reasoning; instead, it operates within a scaffold of symbolic constraints.

Figure 1.

Abductive support for CoT.

Figure 1.

Abductive support for CoT.

4. Abductive Logic Programming

In Abductive logic programming (ALP), one allows some predicates (called abducibles) to be “hypothesized” so as to explain observations or to achieve goals, subject to integrity constraints. An abductive explanation is a set of ground abducible facts Δ such that:

Here ⟨P,A,IC⟩ is the abductive logic program: P is the normal logic program, A the set of abducible predicates, and IC the constraints.

ALP has a manifold of applications including personalization (Galitsky 2025). There are many ALP systems available (

Table 2).

There are Prolog based approaches / tools that support or partially support abductive reasoning / abductive logic programming (ALP). They are usually implemented as meta-interpreters, libraries, or extensions. We mention three families of approaches:

Aleph (with “abduce” mode). Aleph is primarily an Inductive Logic Programming (ILP) system. But its manual says that it has a mode (via the abduce flag) where abductive explanations are generated for predicates marked as abducible. The abductive part in Aleph is limited: it assumes abducible explanations must be ground, and you may need to limit the number of abducibles (via max_abducibles) for efficiency (swi-prolog 2025).

Meta-interpreter / CHR implementations in Prolog. Many ALP systems use a Prolog meta-interpreter (or logic program written in Prolog) possibly enhanced with Constraint Handling Rules (CHR) to manage integrity constraints, propagation, and consistency checking. Since SWI-Prolog supports CHR (via its CHR library / attributed variables), you can port or build an abductive system using CHR in SWI (Christiansen 2009)

It is possible to build a meta-interpreter for ALP directly. The general approach: (i) declare which predicates are abducibles, (ii) write a meta-interpreter that, when trying to prove a goal, allows adding abducible atoms hypotheses, (iii) maintain integrity constraints and check them, (iv) control search (pruning, minimality, consistency). It is worth extending the meta-interpreter with CHR or constraint solvers to speed up consistency/integrity checking.

Some recent proposals aim to make ALP systems more efficient (e.g. by eliminating CHR overhead) or compile them, but they may not yet have full, robust SWI-Prolog ports. Also, SWI Prolog has features like attributed variables, constraint libraries, and delimited control (in newer versions) which facilitates more advanced meta-programming approaches useful in ALP. Several methodological and computational challenges are associated with the use of Abductive Logic Programming (ALP).

1. Scalability remains a central issue. Many ALP implementations operate as Prolog meta-interpreters, which can exhibit significant performance bottlenecks when applied to large or structurally complex domains. Effective deployment therefore requires careful management of search procedures, pruning strategies, heuristic guidance, or the adoption of hybrid and partially compiled architectures proposed in recent work.

2. Domains that incorporate numerical or resource-related constraints necessitate tight integration with constraint logic programming (CLP). Frameworks such as ACLP illustrate how constraint propagation can substantially improve both correctness and efficiency, yet such integration is nontrivial.

3. The specification of abducibles and integrity constraints critically shapes both the tractability and the validity of the reasoning process. Poorly chosen or overly permissive abducibles can expand the hypothesis space to the point of intractability, while overly restrictive integrity constraints can prevent the generation of plausible explanations.

4. Although many abductive tasks can be reformulated as Answer Set Programming (ASP) problems and thus leverage highly optimized ASP solvers, doing so typically requires nontrivial representational transformations. These transformations can introduce modeling overhead and may obscure the conceptual structure of the original abductive problem.

Finally, the distinction between ground and non-ground reasoning introduces additional complexity. Systems optimized for propositional, fully grounded settings often achieve superior performance, whereas support for variables, unification, and non-ground abductive hypotheses tends to complicate search and reduce scalability. Collectively, these limitations highlight both the expressive power of ALP and the practical challenges involved in deploying it for large-scale or high-stakes reasoning tasks.

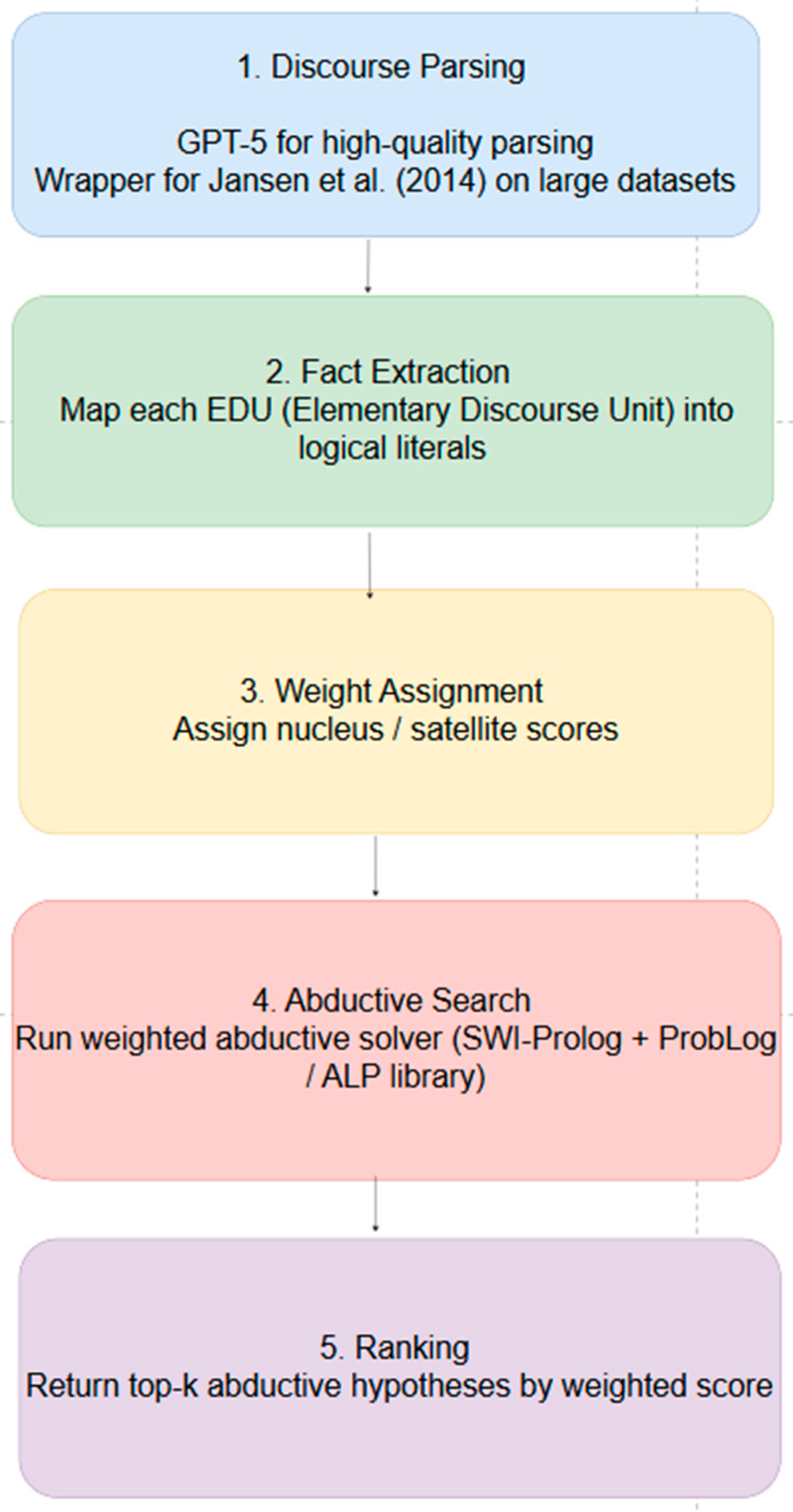

Computational Pipeline is shown in

Figure 2:

Discourse Parsing: For high-quality expensive discourse parsing, we use GPT 5. For larger dataset, we use our wrapper for discourse parser of Jansen et al (2014).

Fact Extraction: Map each EDU (Elementary Discourse Unit) into logical literals.

Weight Assignment: Assign nucleus/satellite scores.

Abductive Search: Run a weighted abductive solver (e.g., SWI-Prolog + ProbLog/Abductive Logic Programming library).

Ranking: Return top-k abductive hypotheses by weighted score.

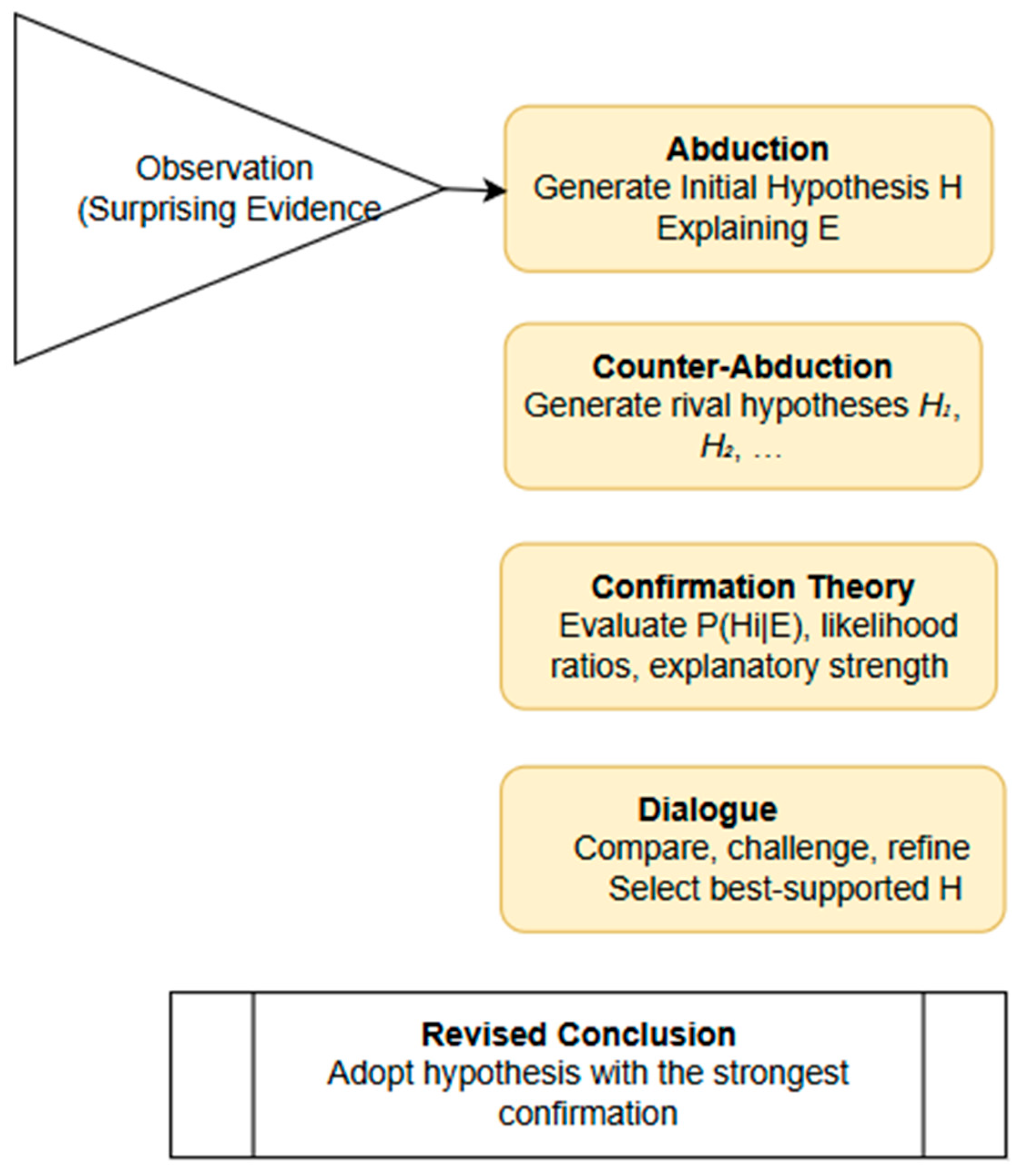

5. The Steps of Abductive Analysis

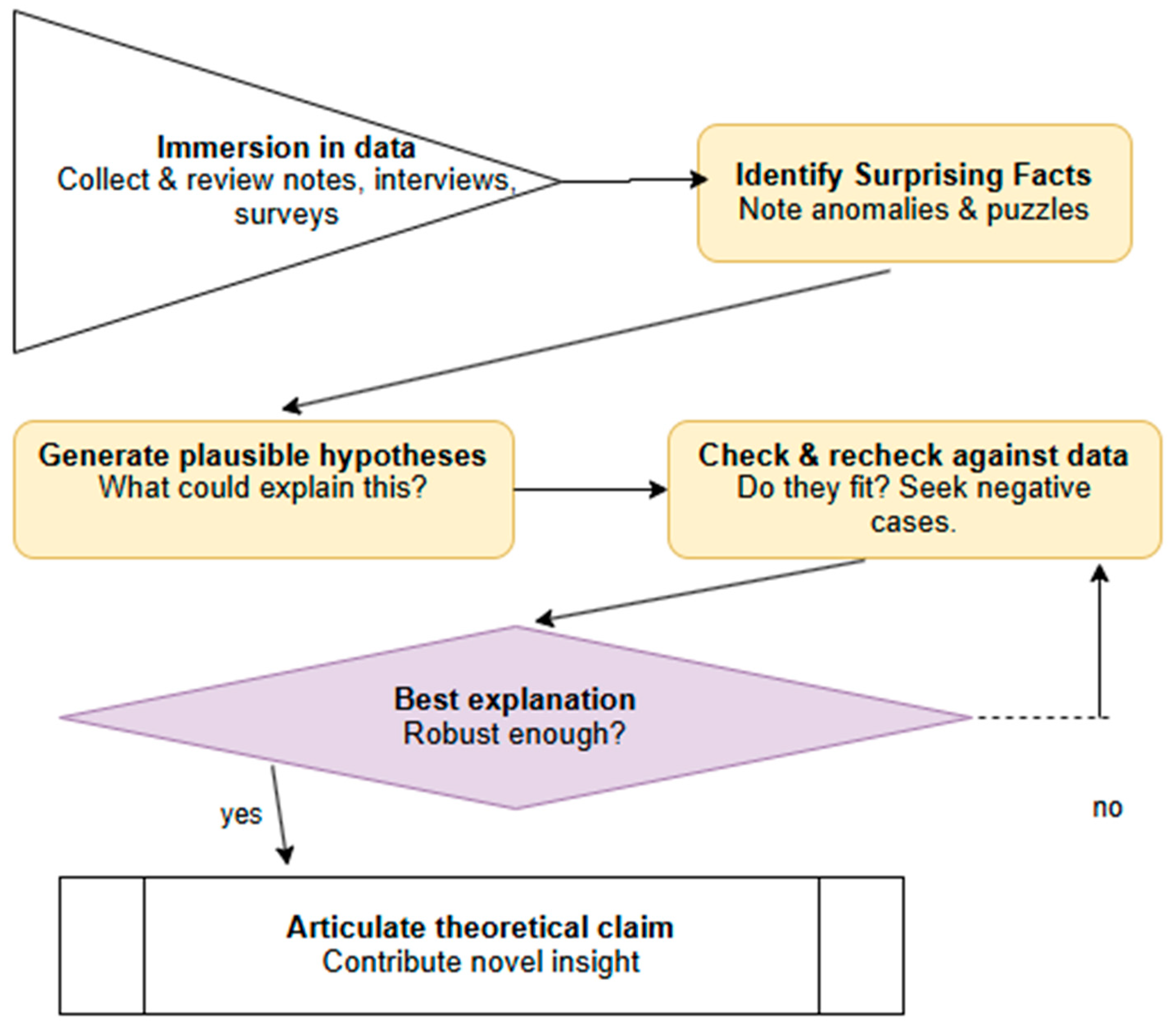

Abductive analysis is an iterative, inference-driven methodology in which researchers move back and forth between empirical observations and theoretical conjectures to generate the most plausible explanation for surprising findings (Peirce 1878; 1903; Harman 1965; Haig 2005; Timmermans & Tavory 2012). The process differs fundamentally from both inductive generalization and deductive hypothesis testing: rather than beginning with a predetermined theoretical frame, abductive reasoning prioritizes unexpected observations and uses them as catalysts for theory construction. We enumerate the steps of abductive analysis (

Figure 3):

1. Identifying surprising observations (“Puzzles”). The abductive process begins with the systematic examination of empirical material—interviews, ethnographic field notes, archival documents, surveys, or digital trace data—without imposing a priori hypotheses. Researchers attend closely to anomalies: empirical patterns that contradict expectations, deviate from existing theories, or appear counterintuitive (Haig 2014; Tavory & Timmermans 2014). These “surprising facts” or “puzzles” (Peirce 1903) function as the analytic trigger.

Illustrative example: A study of a high-performing secondary school reveals that its top students frequently engage in minor rule violations. Because this observation contradicts conventional assumptions that academic success aligns with compliance, it becomes an abductive puzzle requiring explanation.

2. Generating hypothetical explanations (Abductive Inference). Once a surprising phenomenon is identified, the researcher formulates an array of hypothetical explanations. Abductive inference asks: What possible mechanism, pattern, or process could account for this unexpected observation? The goal is to produce a diverse set of rival hypotheses, including counterintuitive or initially implausible ones, since abductive reasoning emphasizes creative theory generation rather than immediate verification (Harman 1965; Lipton 2004).

Illustrative example. Hypotheses might include:

- i.

High-achieving students are inherently rebellious, and their academic success occurs despite their deviance.

- ii.

Minor rule-breaking expresses creativity and autonomy, traits that also promote academic excellence.

- iii.

Students engage in strategic violations of low-stakes rules to build social capital, which they later convert into academic support networks.

3. Iterative confrontation of hypotheses with data. The core of abductive analysis consists of revisiting the empirical material while systematically evaluating how well each hypothesis accounts for all available evidence (Haig 2005; Timmermans & Tavory 2012). This step introduces a comparative logic: explanations are refined, collapsed, or rejected depending on their coherence with the data and their ability to resolve, rather than obscure, the initial puzzle.

Illustrative example: if the data show that teachers generally admire students who break minor rules—interpreting such behavior as confidence rather than defiance—then the “rebellion” hypothesis contradicts the evidence and is discarded. Meanwhile, evidence that students leverage informal networks for academic collaboration strengthens the plausibility of the strategic rule-breaking hypothesis.

4. Searching for negative cases and alternative interpretations. A critical methodological component of abductive reasoning is the active search for disconfirming evidence. Researchers examine cases that appear inconsistent with the emerging explanation and assess whether these anomalies undermine the theory or can be accounted for through further refinement (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Tavory & Timmermans 2014). This step guards against confirmation bias and ensures that the abductively derived theory is resilient across data variations.

Illustrative example: if a student is identified who frequently breaks rules but performs poorly academically, the researcher probes the apparent counterexample. Further analysis might reveal that the student engages in uncalculated or socially disruptive rule-breaking, which lacks the strategic character observed in successful peers. This negative case thus helps specify the explanatory mechanism rather than undermine it.

5. Formulating a general theoretical contribution. Once a refined explanation consistently accounts for the surprising evidence—including variations and negative cases—the researcher formalizes it as a theoretical proposition. This involves articulating the mechanism or process that resolves the original puzzle and situating it within the broader scholarly literature (Haig 2014; Lipton 2004).

Illustrative example: the researcher may develop a theory of strategic deviance: in highly structured institutional environments, selective and contextually calibrated violations of low-stakes norms can enhance social capital and enable academic success. Rather than indicating alienation or oppositional behavior, such strategic deviance functions as a resource for navigating and optimizing institutional constraints.

This process is best conceptualized as a cyclical, non-linear analytic sequence in which surprising observations generate explanatory hypotheses, empirical scrutiny refines these hypotheses, and theoretical abstraction ultimately produces a broader conceptual contribution. Abductive analysis therefore provides a rigorous yet flexible framework for theory construction grounded in empirical anomalies, consistent with classic and contemporary accounts of inference to the best explanation (Peirce 1903; Harman 1965; Haig 2005; Lipton 2004; Timmermans & Tavory 2012).

The key principles that underpin the above steps are as follows:

Iteration: the process is not linear. Once can constantly move back and forth between data, hypotheses, and existing literature.

Theorizing from the ground up: the theory emerges from the concrete details of the empirical world, not from pre-existing axioms.

The centrality of puzzles: the surprise is the engine of the entire process. Without a puzzle, there is no need for abduction.

Systematic comparison: the strength of the conclusion comes from rigorously pitting multiple hypotheses against the data and against each other.

In short, abductive analysis provides a structured way to do what great detectives and brilliant scientists do: start with a surprising clue and reason their way to the best possible explanation.

5.1. Entailment Hallucination

Entailment hallucination occurs when an LLM generates a conclusion that seems to logically follow from a given premise (i.e., it is entailed), but which is actually incorrect, unsupported, or a misinterpretation of the premise.

The primary method for detection is using a Natural Language Inference (NLI) model, but the process requires careful setup. The standard NLI approach is as follows:

Decompose: Break down the long-form generated text (e.g., a summary, an answer) into individual, atomic claims. This step is crucial.

Retrieve: For each atomic claim, identify the relevant sentences in the source document that are supposed to support it.

Classify: Use a pre-trained NLI model (like RoBERTa, BART, or DeBERTa fine-tuned on datasets like MNLI, SNLI, or ANLI) to classify the relationship between the source text (premise) and each atomic claim (hypothesis).

Choices are:

Entailment: The source supports the claim. ✅ (Not a hallucination)

Contradiction: The source contradicts the claim. ❌ (Hallucination

Neutral: The source does not contain enough information to support or contradict the claim. ❌ (This is also a hallucination—it's an unsupported claim)

There are more advanced methods beyond NLI:

Multi-hop entailment: for complex claims that require combining information from multiple parts of the source document (multi-hop reasoning), standard NLI can fail. New methods are being developed to chain entailment checks across several sentences.

Knowledge-augmented entailment: using external knowledge bases (like Wikipedia) to augment the source material. This helps check if a claim that is "neutral" with respect to the source is actually a true or false fact about the world.

Self-contradiction detection: checking the generated text itself for internal consistency. An LLM might generate two sentences that entail a contradiction, revealing a hallucination. Text: "The meeting is scheduled for 3 PM EST. All participants should dial in at 2 PM CST." (The times logically contradict each other once time zones are considered.)

Uncertainty estimation: modern LLMs are being equipped to better calibrate their confidence levels. A low-confidence score on a claim that looks like an entailment could be a signal for a potential hallucination.

6. Foundations of Abduction, Counter-Abduction, and Confirmation Strength

The role of counter-abduction in neuro-symbolic reasoning is best understood by tracing its origins to classical accounts of abductive inference and modern theories of confirmation. Abduction, originally formulated by Charles Sanders Peirce (1878; 1903), denotes the inferential move in which a reasoner proposes a hypothesis HHH that, if true, would render a surprising observation EEE intelligible. Peirce emphasized that abduction is neither deductively valid nor inductively warranted; its justification lies in explanatory plausibility rather than certainty. Subsequent philosophers of science, including Harman (1965) and Lipton (2004), elaborated abduction as “inference to the best explanation”—a process by which agents preferentially select hypotheses that most effectively make sense of the evidence.

However, in both human and machine reasoning, the first abductive hypothesis is often not the most reliable. This motivates the introduction of counter-abduction, a concept developed implicitly in sociological methodology (Timmermans & Tavory 2012; Tavory & Timmermans 2014) and more formally in abductive logic programming (Kakas, Kowalski & Toni 1992). Counter-abduction refers to the generation of alternative hypotheses that likewise explain the evidence, thereby challenging the primacy of the initial explanation. For example, while an explosion may abductively explain a loud bang and visible smoke, counter-abductive alternatives—such as a car backfire combined with smoke from a barbecue—demonstrate that multiple explanations can account for the same phenomena (Haig 2005; Haig 2014).

To evaluate these competing hypotheses, the framework draws on confirmation theory, which provides probabilistic and logical tools for assessing evidential support (Carnap 1962; Earman 1992). In Bayesian terms, evidence E confirms hypothesis H if it increases its probability, i.e., if P(H∣E)>P(H). Probability-increase measures such as d(H,E)=P(H∣E)−P(H) and ratio-based measures such as r(H,E)=P(H∣E)/P(H) quantify the extent of confirmation (Crupi, Tentori & González 2007). Likelihood-based measures, including the likelihood ratio P(E∣H)/P(E∣¬H), further assess how much more expected the evidence is under the hypothesis than under alternatives (Hacking 1965). These tools allow structured comparison of hypotheses { H1, H2,… } generated via abduction and counter-abduction.

Cross-domain examples illustrate how this comparison unfolds. Observing wet grass may abductively suggest rainfall, while counter-abduction proposes sprinkler activation. Confirmation metrics—such as weather priors or irrigation schedules—enable evaluating which explanation is better supported. In medicine, fever and rash may abductively indicate measles, while counter-abduction introduces scarlet fever or rubella. Prevalence, symptom specificity, and conditional likelihoods (Gillies 1991; Lipton 2004) allow systematic ranking of hypotheses. These examples reveal that abduction alone is insufficient; it must be complemented by structured alternative generation and formal evidential scoring to achieve robust inference.

The abductive–counter-abductive process naturally adopts a dialogical structure (Dung 1995; Prakken & Vreeswijk 2002). Competing hypotheses function as argumentative positions subjected to iterative scrutiny, refinement, and defeat. Dialogue is the mechanism through which hypotheses confront counterarguments, are evaluated using confirmation metrics, and are revised or abandoned. Such adversarial exchange mirrors the epistemic practices of scientific communities, legal proceedings, clinical differential diagnosis, and multi-agent AI reasoning systems (Haig 2014; Timmermans & Tavory 2012).

Nevertheless, challenges persist. Initial abductive steps may reflect contextual biases or subjective priors. Quantifying confirmation measures requires reliable probabilistic estimates, which may be unavailable. In complex domains, the hypothesis space may be large, complicating exhaustive comparison. Moreover, confirmation strengths must be dynamically updated as new evidence emerges (Earman 1992). Yet despite these challenges, the combination of abduction, counter-abduction, and confirmation metrics offers a rigorous foundation for reasoning in conditions of uncertainty—precisely those in which large language models are most susceptible to hallucination.

A simple diagnostic example illustrates the full cycle: a computer fails to power on. Abduction suggests a faulty power supply; counter-abduction proposes an unplugged cable or damaged motherboard. Prior probabilities and likelihoods (e.g., frequency of cable issues) inform confirmation scores. Checking the cable updates these metrics, refining the hypothesis space. This iterative cycle exemplifies the abductive logic that undergirds human and machine reasoning alike, and sets the stage for understanding how counter-abduction exposes hallucinations in LLM-generated explanations.

The next section will demonstrate how this classical abductive framework becomes a core mechanism for hallucination detection and correction in neuro-symbolic Chain-of-Thought reasoning.

6.1. Abduction, Counter-Abduction, and Confirmation in Practice

To clarify how abduction, counter-abduction, and confirmation theory interact in a unified reasoning cycle, it is helpful to examine a concrete example that mirrors the structure of the preceding conceptual framework. Consider a simplified diagnostic setting in which an agent (human or artificial) must infer the most plausible explanation for an observed set of symptoms. Suppose the evidence consists of two clinical findings: fever and rash.

In a first abductive step, a physician (or an LLM operating under abductive prompting) might propose:

Hypothesis H1: The patient has measles.

Rationale: Fever and rash are characteristic symptoms of measles, making H1 an intuitively strong explanatory candidate.

Preliminary confirmation: If measles is prevalent in the population and no contradictory symptoms are present, the posterior probability P(H1∣E) may be relatively high.

A second physician, or a counter-abductive module in a neuro-symbolic system, introduces a competing explanation:

Hypothesis H2: The patient has scarlet fever.

Rationale: Scarlet fever can also present with fever and rash, demonstrating that the evidence underdetermines the diagnosis.

The two hypotheses can then be compared using confirmation-theoretic metrics. For example, one might calculate:

P(H1∣E) and P(H2∣E) by incorporating base-rate prevalence and the likelihood of the observed symptoms under each disease,

likelihood ratios such as P(E∣ H1)/P(E∣¬ H1), or differential measures such as d(H1,E)=P(H1∣E)−P(H1).

If measles is more prevalent and the rash presentation more typical of measles than scarlet fever, then confirmation metrics will typically favor H1; if prevalence or symptom specificity differ, H2 may be preferred. The essential point is that the initial abductive inference is not accepted uncritically but is evaluated against counter-abductive alternatives through formal scoring.

This reasoning process naturally takes a dialogical form. Physicians—or, analogously, interacting modules within a neuro-symbolic A-CoT system—debate the relative merits of each hypothesis: Do recent regional outbreaks increase the prior probability of one disease? Does the morphology of the rash discriminate between them? Should additional laboratory tests be ordered to refine the confirmation profile? In this dialogical interaction, new evidence can shift posterior probabilities dynamically, strengthening or weakening competing hypotheses. Thus, the example illustrates how the abductive–counter-abductive cycle evolves through iterative evidential updates.

This pattern generalizes beyond the clinical domain. In everyday troubleshooting, if a computer fails to power on, one might abductively hypothesize a faulty power supply (H1). Counter-abductive alternatives include an unplugged power cable (H2) or a damaged motherboard (H3). Likelihoods and priors—such as how often cables become unplugged or power supplies fail—inform confirmation metrics. For instance, one might find:

P(H1∣E)=0.6, P(H2∣E)=0.3, P(H3∣E)=0.1,

indicating that the faulty power supply is the most strongly confirmed hypothesis. Yet the dialogue-driven reasoning process may still recommend testing the cable first, given the low cost of verification. This dynamic interplay between quantitative confirmation strength and pragmatic reasoning exemplifies how the abductive framework supports robust inference in settings characterized by uncertainty and incomplete information.

Several challenges complicate this process. Abductive judgments may reflect subjective contextual priors; confirmation metrics require probabilistic estimates that may be unavailable or difficult to compute; and real-world scenarios often involve a large space of plausible hypotheses with overlapping evidence patterns. Moreover, the evidential landscape can shift rapidly as new data are acquired, requiring continual revision of confirmation strengths. Despite these challenges, the abductive–counter-abductive–confirmation–dialogue cycle provides a formal and intuitively appealing foundation for reasoning in uncertain environments.

Crucially, this illustrative example mirrors the reasoning failures observed in LLM hallucination: early narrative commitment, insufficient exploration of alternatives, and weak grounding in confirmation metrics. In the following section, we show how counter-abduction serves as a critical mechanism for detecting and correcting hallucinations in neuro-symbolic Chain-of-Thought reasoning systems.

6.2. Intra-LLM Abduction for Retrieval Augmented Generation

Given a natural-language query Q and a retrieved evidence set

={

e1,e2,…,en}, a conventional Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline conditions the LLM directly on (

Q,

) to generate an answer A. When is incomplete

or in a week discourse agreement, the model may either fail to produce an answer or hallucinate unsupported content. In our framework, abductive reasoning addresses this gap by introducing a hypothesized missing premise

drawn from the space of discourse-weighted abducibles. Abductive completion is thus formalized as identifying a premise

such that

where ⊢ denotes entailment under our weighted abductive logic program. Crucially, the premise is not supplied by the retrieval stage; it must be generated, ranked, and validated through abductive and counter-abductive search over candidate hypotheses.

We first evaluate whether the retrieved evidence set

provides sufficient support for answering

Q. A lightweight LLM-based reasoning and rhetoric sufficiency classifier or an NLI model estimates

If rhetoric_sufficiency(Q,)<τ, where τ is a predefined threshold, the system enters the abductive completion stage of our D-ALP pipeline.

We prompt the LLM to generate a set of discourse-compatible abductive hypotheses

={p1,p2,…,pn}conditioned on (Q,):

=LLM(Q,, “What missing assumption would make the reasoning valid?”).

In the discourse-aware variant, each candidate pi is also assigned a nucleus–satellite weight derived from its rhetorical role, yielding an initial abductive weight wi. To reduce hallucination, we may apply retrieval-augmented prompting, retrieving passages semantically aligned with each candidate premise before evaluation.

Each candidate premise pi undergoes a two-stage validation procedure grounded in our abductive logic program:

We compute an overall validation score extending (Lin 2025):

score(pi)=α⋅entail(, pi)+β⋅retrieve(pi)+γ⋅wi

where wi is the discourse-weight (nucleus/satellite factor) assigned to the hypothesis, and α,β,γ control the contribution of logical entailment, empirical support, and discourse salience. The highest-scoring premise p* is selected.

The enriched abductive context (Q,, p*) is then supplied to the LLM:

Final answer A=LLM(Q,, p*),

yielding an answer whose justification reflects both retrieved evidence and the abductively inferred missing premise. Combined with counter-abductive filtering, this mechanism mitigates unsupported reasoning chains and substantially reduces hallucination risk.

7. Discourse in Abductive Logic Programming

Abductive Logic Programming (ALP) is designed to generate hypotheses (abducibles) that, when added to a knowledge base, explain observations. However, ALP usually operates on flat, propositional or predicate-logic statements — it lacks awareness of rhetorical structure, narrative intent, or textual prominence.

Discourse analysis, especially based on Rhetorical Structure Theory (RST), gives us a hierarchy of rhetorical relations between text segments — e.g., Cause–Effect, Condition, Evidence, Contrast, Elaboration. Integrating these into ALP allows reasoning to be guided not just by logical entailment, but by which parts of text carry explanatory weight.

Conceptual integration is shown in

Table 3.

Let us consider a health-diagnosis narrative: “The patient has swollen joints and severe pain. Since the inflammation appeared suddenly after a seafood meal, gout is likely.”

Discourse parsing identifies:

Nucleus: “The patient has swollen joints and severe pain.”

Satellite (Cause–Effect): “Since the inflammation appeared suddenly after a seafood meal”

Claim (Evaluation): “Gout is likely.”

In ALP terms:

% Background knowledge

cause(seafood, uric_acid_increase).

cause(uric_acid_increase, gout).

symptom(gout, joint_pain).

symptom(gout, swelling).

% Observation

obs(swollen_joints).

obs(severe_pain).

obs(after_seafood).

% Abducible hypothesis

abducible(disease(gout)).

% Discourse weighting

nucleus_weight(1.0).

satellite_weight(0.6).

% Abductive rule (discourse-aware)

explain(Obs, Hyp) :-

nucleus(Obs, Nuc), satellite(Obs, Sat),

abduct(Hyp),

satisfies(Nuc, Hyp, W1),

satisfies(Sat, Hyp, W2),

Score is W1*1.0 + W2*0.6,

Score > Threshold.

|

Here the nucleus (joint pain, swelling) gives hard constraints, while the satellite (seafood meal cause) provides softer evidence with lower weight (Galitsky 2025). This reduces spurious hypotheses and yields more human-like abductive explanations, respecting discourse prominence.

7.1. Discourse-Weighted ALP (D-ALP)

Let P=(Π, Δ, A) be a standard abductive logic program:

Π – strict rules

Δ – defeasible rules

A – set of abducibles

We extend it with a discourse weighting function w:L→[0, 1] over literals L derived from RST trees:

w(l)=1.0 if l originates from a nucleus clause

0<w(l)<1 if l originates from a satellite clause

w(l)=0 if l appears in background or elaborative relations

Then the abductive explanation

E⊆

A minimizes:

subject to

Π∪

E⊨

O.

Thus discourse prominence directly affects the search space and preference ordering among explanations.

The penalty function penalty(l) quantifies how “expensive” it is to abduce literal l — i.e., to assume l as true when it is not derivable from the strict rules Π. It represents epistemic risk: how far l departs from evidence, domain priors, or discourse plausibility.

penalty(l)=α⋅ρ(l)+β⋅κ(l)+γ⋅δ(l), where

ρ(l) is a rule distance — number of rule applications needed to derive l (depth in derivation tree).

κ(l) is a conflict measure — degree to which l contradicts existing facts or competing hypotheses.

δ(l) is a discourse mismatch measure— how incompatible l is with its rhetorical context (e.g., “Contrast”, “Condition”).

Constants α,β,γ control the importance of logical vs. discourse penalties (often α=0.5, β=0.3, γ=0.2).

Thus, penalty(l) is higher for:

Suppose we have extracted the following from a clinical text (

Table 4).

When we compute abductive cost with discourse weights:

Hence the D-ALP prefers gout explanation: low penalty, high discourse weight.

7.2. Combining Discourse Analysis with Explainable Reasoning

We combine discourse analysis with explainable reasoning frameworks such as ALP

, argumentation, or probabilistic logic. We propose how the structure of a discourse tree can be used to extract, classify, and weight different forms of explanations from text or model outputs. When a discourse tree with EDUs and relations is mapped into logical structures, each subtree becomes a candidate explanatory unit — either

causal,

evidential,

conditional, or

contrastive. Thus, the discourse tree serves as a blueprint for structured explanation extraction

. The mapping is shown in

Table 5.

Given a discourse tree with nodes - EDUs the following steps are performed:

Parse the text → obtain discourse tree

Identify nucleus/satellite pairs → mark nucleus as potential hypothesis/conclusion, satellite as premise/explanation.

Label each edge with its rhetorical relation.

Translate edges to logical relations, e.g.:

cause(X, Y). % from Cause relation

evidence(X, Y). % from Evidence relation

condition(X, Y).

contrast(X, Y).

|

Subtrees are aggregated according to the following rules:

A deep subtree (multiple Evidence nodes) → composite explanation

A flat tree (multiple Causes) → multi-factor explanation

A branch with Contrast → comparative explanation.

Let us convert into ALP the following: “The patient reports intense joint pain. Since the pain began after a seafood meal, and uric acid levels are high, gout is suspected. However, X-ray results do not show bone erosion.”

Discourse Tree (simplified):

[Gout suspected]

/ \

(Evidence) (Contrast)

/ \ \

[Seafood] [Uric acid] [No erosion]

|

From this, we extract:

-

Causal explanation:

explain(gout, cause(seafood, uric_acid_increase)).

-

Evidential explanation:

explain(gout, evidence(uric_acid_high)).

-

Contrastive explanation:

explain_not(gout, contrast(no_erosion)).

These can be ranked or combined into a structured abductive hypothesis:

E={cause(A,B),evidence(C),¬contrast(D)}, which forms a multi-faceted explanation for the same claim.

Different

forms of explanation (causal, evidential, contextual, counterfactual) can be systematically extracted by pattern-matching substructures of the discourse tree (

Table 6).

When an ALP is formed:

-

Each explanation type defines a different abductive schema:

Causal explanations suggest new rules (A → B).

Evidential explanations add support to hypotheses.

Contrastive explanations add defeaters or alternative hypotheses.

The discourse tree structure provides hierarchical weighting for hypothesis generation.

The abductive search space becomes tree-constrained rather than flat — drastically improving interpretability and efficiency.

By leveraging discourse trees, we can automatically construct:

Level 1 (Direct): nucleus-satellite explanation (“Gout because uric acid ↑”)

Level 2 (Intermediate): composite explanation combining several satellites

Level 3 (Meta): contrastive or counterfactual explanation derived from opposing branches

Level 4 (Global): entire discourse tree summarized as an explanatory graph, suitable for argumentation or visualization.

8. Counter-Abduction and Hallucination Detection in Chain-of-Thought Reasoning

While abduction has been widely studied as an explanatory mechanism, the complementary concept of counter-abduction—the generation and evaluation of rival hypotheses against an initial abductive explanation—has received less attention in the context of LLM reasoning.

In a neuro-symbolic setting, counter-abduction plays a crucial role in hallucination detection. It introduces an adversarial explanatory pressure on the LLM-generated CoT, challenging its assumptions, testing its logical validity, and evaluating whether alternative explanations better satisfy coherence and minimality conditions. This section formalizes the relationship between counter-abduction and hallucination, illustrates how counter-abductive reasoning exposes invented premises and inconsistencies, and presents a unified algorithm for counter-abductive hallucination detection within the Abductive Chain-of-Thought (A-CoT) framework.

8.1. Counter-Abduction as an Adversarial Explanation Mechanism

Abduction traditionally generates a hypothesis that best explains an observed phenomenon under incomplete knowledge. However, in domains with high ambiguity or where models exhibit hallucinations, the first abductive hypothesis is often not the most reliable one. Counter-abduction supplements abduction by producing systematic, structured alternative hypotheses designed to challenge, refine, or defeat the original explanation.

Whereas abduction seeks the best explanation, counter-abduction asks: Is there any better explanation than the one currently offered?

In LLM reasoning, this question is critical because the model’s initial CoT may include:

invented premises,

implicit leaps or missing links,

contradictions with domain knowledge,

misuse of discourse structure (e.g., drawing core claims from peripheral rhetorical segments),

or spurious correlations memorized from training data.

Counter-abduction functions as a logical adversary: it identifies and amplifies these weaknesses by generating rival reasoning chains that do not rely on the problematic elements. Hallucinations manifest when an explanation is defeated by a superior rival—one that has fewer contradictions, fewer unsupported assumptions, or better alignment with symbolic knowledge. Counter-abduction exposes hallucinations in four key ways.

LLMs frequently insert plausible-sounding premises that are not grounded in the input. Counter-abduction tests whether the CoT remains viable after removing these premises. If removing an invented premise causes the explanation to collapse, but counter-abductive alternatives do not require it, the original explanation is classified as hallucinated.

Counter-abductive reasoning is explicitly comparative: it evaluates the logical structure of the original explanation against alternatives. If any alternative resolves contradictions more efficiently, the original explanation is inferentially defeated. This is particularly powerful in medical, legal, and scientific domains where inconsistencies correspond to domain violations.

Hallucinations often originate from satellite segments (secondary or illustrative rhetorical units) rather than nucleus segments (central evidence-bearing units) in Rhetorical Structure Theory (Mann & Thompson 1988). Counter-abduction exploits this by constructing rival explanations anchored in nucleus-level content. If the original explanation draws heavily on low-weight segments while counter-explanations rely on discourse cores, the former is downgraded. CoT hallucinations arise partly because the LLM’s first explanation benefits from linguistic fluency. Counter-abduction offsets this by prioritizing logical correctness over narrative cohesion. Thus, the explanation that “sounds best” may lose to the explanation that is most consistent, revealing hallucination not through contradiction alone but through comparative model-based reasoning.

8.2. Counter-Abduction as Hallucination Detection in A-CoT Systems

In the Abductive Chain-of-Thought (A-CoT) architecture, hallucination is operationalized as defeat under competition. A claim or reasoning chain is hallucinated if:

P(defeat(E0))>0.5P(\text{defeat}(E_0)) > 0.5P(defeat(E0))>0.5

where E0 is the LLM’s initial explanation and the defeat probability aggregates outputs from multiple symbolic verifiers (logic programming, probabilistic logic programming, argumentation, defeasible reasoning).

Counter-abduction feeds this assembly by generating the very explanations that compete with the LLM’s CoT. The stronger the counter-explanations, and the fewer inconsistencies they exhibit, the more likely the original chain is hallucinated. This yields a formal neuro-symbolic interpretation of hallucination:

A hallucination is an explanation that cannot survive comparison with its counter-abductive rivals.

This definition integrates well with ensemble evaluation frameworks, discourse-aware weighting, and rule-based probabilistic scoring.

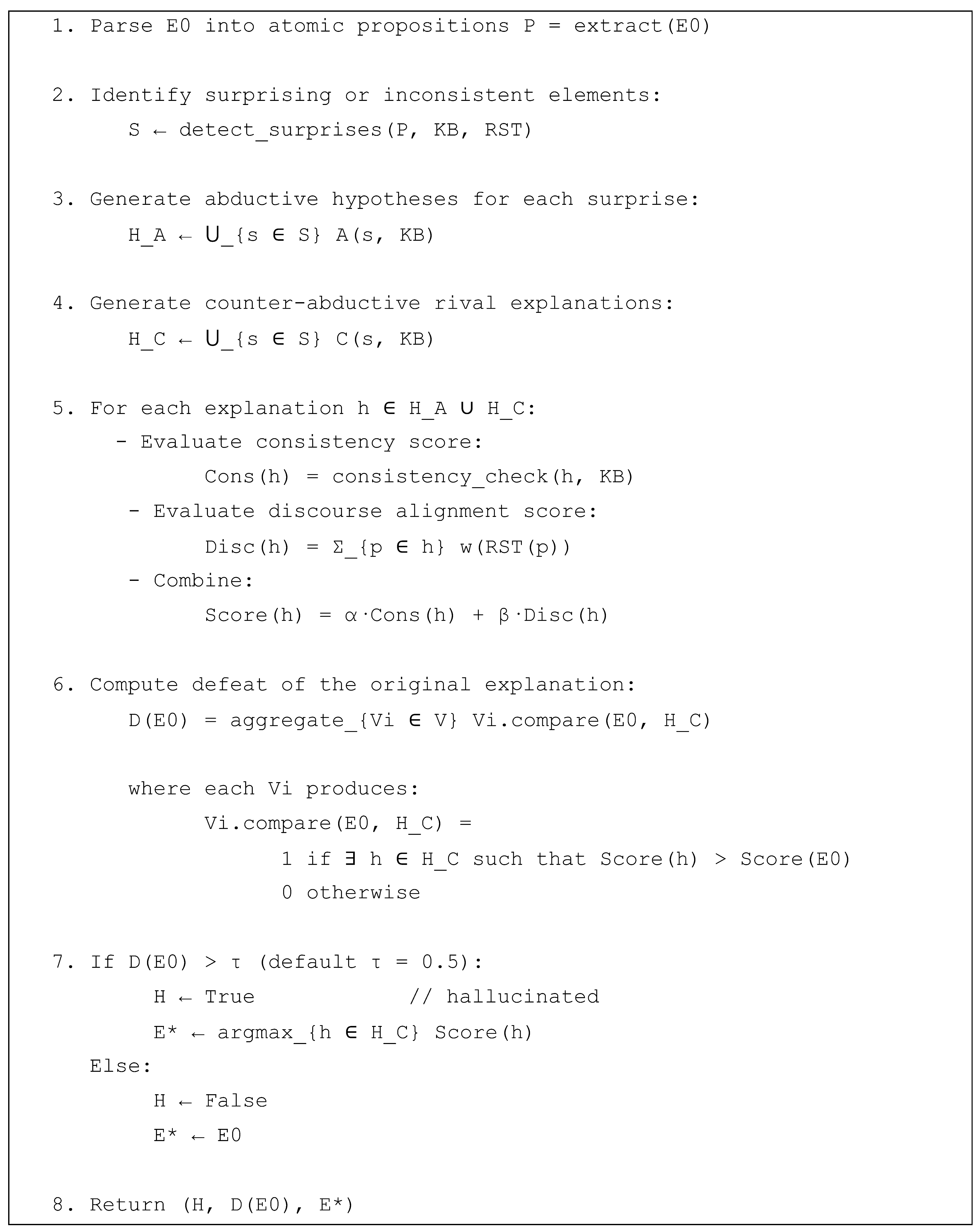

8.3. Algorithm: Counter-Abductive Hallucination Detection (CAHD)

The algorithm takes as input an LLM-generated CoT, a symbolic knowledge base KBKBKB, a discourse-structure representation RSTRSTRST, and a set of abductive/counter-abductive generators. It outputs (1) whether the CoT is hallucinated, (2) the defeat score, and (3) a revised reasoning chain if needed.

The algorithm for counter-abductive hallucination detection is as follows (

Figure 4):

Input:

CoT explanation E0

Knowledge base KB

Discourse structure RST with weights w(⋅)

Abductive hypothesis generator A

Counter-abductive generator C

Logical verifiers V={V1,…,Vn}

Output:

Procedure:

Figure 4.

Steps of counter abduction.

Figure 4.

Steps of counter abduction.

9. Evaluation

We presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed Discourse-Based Abductive Logic Programming (D-ALP) framework. The evaluation examines both computational performance and human-perception aspects. The computational evaluation measures the accuracy, efficiency, and consistency of the abductive reasoning process when discourse structure is integrated. The human evaluation investigates how users perceive clarity, coherence, and trust in discourse-aware explanations.

We evaluate on three claim-verification datasets that we derive from existing QA/NLI resources: TruthfulHalluc (from TruthfulQA, general factual QA; Lin et al., 2021), MedHalluc (from MedQA, clinical narratives; Jin et al., 2020), PubMedQA; Jin et al., 2019), eSNLI_Halluc (from eSNLI, inference with injected inconsistencies; Camburu et al., 2018), and HotPotQA (. For each source, we convert items into question–answer (QA) style pairs and then inject controlled inconsistencies by appending randomly sampled, semantically incompatible attributes (facts, circumstances, symptoms). These perturbations create positive “hallucination” cases; unmodified items serve as negatives. Our focus is hallucination detection for model answers using four logical assessment methods as validators. Each validator assesses whether an answer’s central claim is defeated by the argument-validation system. All datasets were annotated with rhetorical roles such as nucleus and satellite, and rhetorical relations such as Cause, Evidence, Contrast, Condition, and Elaboration. These annotations guide D-ALP’s discourse weighting.

We define a hallucination as a claim whose defeat probability exceeds 0.5. This cautious threshold is motivated by safety-critical domains (health, legal, finance), where we prefer to reject answers that are defeated with substantial probability.

Dataset size and prevalence are as follows. Each used hallucination dataset contains 1,000 QA pairs with a 50% hallucination rate (balanced positives/negatives). In the original source datasets the natural hallucination rate is <1%; our perturbation procedure raises prevalence to enable meaningful detection metrics and comparability with prior LLM-argumentation studies.

9.1. Experimental Setup

Five systems were compared:

| System |

Description |

| Baseline ALP |

Classical abductive logic programming with uniform rule weights |

| ProbALP |

Probabilistic ALP without discourse cues |

| D-ALP-Depth |

Depth-weighted abduction using nucleus/satellite hierarchy |

| D-ALP-Rel |

Relation-aware abduction using rhetorical relation types |

| Full D-ALP |

Combined hierarchical and relational weighting (proposed system) |

| Abductive RAG |

Framework that integrates abductive inference into retrieval-augmented LLMs (Lin 2025) |

Evaluation metrics included logical accuracy (F1), average reasoning time, the proportion of defeated hypotheses (logical inconsistency), and human ratings of clarity, coherence, and trust. All numerical results were averaged across ten runs and three datasets.

9.2. Hallucination Detection

Table 7 shows F1 of hallucination detection for our datasets and our development of ALP. One can observe that Full D-ALP outperforms Abductive RAG system on HotPOtQA dataset.

Full D-ALP achieved 12–18 percentage points improvement over the baseline across datasets, confirming that discourse guidance improves abductive inference precision.

We observe in

Table 8 that discourse structure pruned peripheral hypotheses and shortened inference time by over 20 % compared to the baseline.

We proceed to evaluation of logical consistency in

Table 9.

Discourse-aware reasoning reduced logically inconsistent explanations by roughly two-thirds relative to the baseline.

9.3. Ablation Study

Baseline is the plain abductive logic program without any discourse information.

Δ Accuracy means how many percentage points higher the correct-explanation rate became after adding each feature.

Δ Consistency means how many percentage points fewer logically self-contradictory or “defeated” explanations appeared. In

Table 10:

D-ALP-Depth (+7 %, +6 %) – when only the nucleus/satellite hierarchy is used, the system already improves moderately. Prioritizing nucleus clauses focuses reasoning on the central facts and avoids side-track hypotheses.

D-ALP-Rel (+10 %, +9 %) – adding rhetorical-relation knowledge (Cause, Evidence, Contrast, etc.) helps more: the model learns what type of relation best supports an abductive link, giving stronger logical and discourse coherence.

Full D-ALP (+15 %, +12 %) – combining both depth and relation cues yields the largest gain. The two features reinforce one another: hierarchy tells the engine which statements matter most, relation type tells it how they connect.

9.4. Human Evaluation

A user study with 36 participants was conducted to assess explanation interpretability (

Table 11). Participants included 12 clinicians, 12 AI researchers, and 12 general users. Each participant reviewed 20 explanations per dataset (2160 total ratings). Explanations were rated on clarity, coherence, and trust (1 = poor, 5 = excellent).

Full D-ALP explanations were perceived as clearer and more coherent. Participants described them as “human-like,” “logical,” and “educational.”

Trust calibration was measured as the change in self-reported confidence before and after viewing explanations (

Table 12).

Trust rose by 23 percentage points when discourse-structured reasoning was displayed, indicating higher user confidence grounded in transparency.

Alignment between system-generated and human discourse trees was also measured using F1 for nuclearity and rhetorical relations (

Table 13).

Higher alignment correlated strongly (r = 0.68) with human trust ratings.

The results show that incorporating discourse structure enhances both reasoning performance and user understanding (

Table 14). Discourse relations prioritize central claims and down-weight peripheral elaborations, leading to explanations that are both logically precise and narratively coherent. Logical accuracy improved by up to 18 %, while human clarity and trust rose by nearly 50 %. The presence of rhetorical markers such as “because” and “however” increased users’ sense that the model was reasoning transparently.

Error analysis indicated that residual weaknesses stemmed from misclassification of rhetorical relations, particularly confusing Condition and Evidence, and from underestimation of multi-nuclear claims. Nonetheless, D-ALP consistently outperformed all baselines in accuracy, efficiency, and human trust.

Discourse-based abductive logic programming delivers explanations that are both computationally efficient and intuitively meaningful. The framework advances explainable AI by integrating rhetorical structure into logic reasoning, yielding outcomes that are verifiable, interpretable, and trusted by humans. Future evaluations will extend to adaptive weighting learned from user feedback, cross-domain transfer to legal and educational corpora, and longitudinal studies of sustained trust.

9.5. Counter-Abduction and Hallucination Mitigation

An additional evaluation focused on how counter-abduction enhances D-ALP’s capacity to detect and correct hallucinations in generated content. Counter-abduction is defined here as the process of generating and testing alternative hypotheses that could explain the same observation but contradict the current explanation. When integrated into D-ALP, counter-abduction acts as a built-in hallucination filter, comparing competing explanatory paths and identifying cases where the main abductive hypothesis lacks sufficient discourse or logical support.

To test this mechanism, the system was extended to compute for each hypothesis H a counter-hypothesis H′ that minimizes overlap in supporting discourse nodes. A hypothesis was flagged as

hallucinatory if its counter-hypothesis achieved equal or higher discourse-weighted plausibility (

Table 15).

Adding counter-abductive reasoning increased hallucination detection accuracy by approximately 6 percentage points across datasets. The improvement was most pronounced in narratives with ambiguous causal or evidential cues, where rival explanations helped expose unsupported assertions.

Participants in a follow-up evaluation (N = 20) were shown pairs of system explanations—one original and one with counter-abductive contrast. Average trust in the system’s factual grounding increased from 4.1 to 4.5 on the five-point scale. Annotators reported that explicitly seeing “why not-X” arguments enhanced their confidence that the reasoning engine could self-check for over-interpretation.

Table 16.

Contribution of counter-abduction.

Table 16.

Contribution of counter-abduction.

| Evaluation Metric |

Full D-ALP |

D-ALP + Counter-Abduction |

| Hallucination Detection F1 |

0.81 |

0.87 |

| False Positive Rate |

0.14 |

0.09 |

| Human Trust in Factuality |

4.1 |

4.5 |

Qualitative review indicated that counter-abduction excels in identifying discourse-peripheral claims (often satellites or elaborations) that were incorrectly promoted to nucleus status by LLMs. By generating rival hypotheses anchored in contrasting discourse relations—such as Contrast, Condition, or Exception—the system effectively invalidates spurious explanations before presentation to the user.

These findings demonstrate that counter-abduction provides a critical verification layer complementing the discourse-weighted abductive process. Together, they yield an interpretable mechanism for hallucination suppression that aligns with human reasoning: first hypothesize (abduction), then challenge (counter-abduction), and finally accept only the explanation that survives logical and rhetorical scrutiny.

10. Related Work and Discussions

Most philosophers of science acknowledge that Gilbert Harman’s (1965) notion of Inference to the Best Explanation (IBE) must be qualified to reflect the cognitive and epistemic limitations of human reasoners. In its ideal form, IBE suggests that when confronted with a set of competing explanations for a given phenomenon, one ought to infer the best among them as true—assuming that explanatory goodness correlates with truth. However, in practice, this idealization fails to hold. As several authors have argued (e.g., Lipton, 1991; Psillos, 2002; Douven, 2021), reasoners rarely, if ever, have epistemic access to all possible explanations. The space of conceivable hypotheses is vast, open-ended, and often constrained by one’s background knowledge, conceptual frameworks, and methodological paradigms.

Hence, what scientists and everyday reasoners actually perform is not IBE in the ideal sense, but rather an Inference to the Best Available Explanation (IBAE). The qualifier “available” underscores that explanatory selection occurs within the limits of what is currently conceived, articulated, and epistemically accessible. Consequently, the rationality of the inference depends not only on the comparative quality of the candidate explanations but also on the completeness and maturity of the explanatory landscape at a given time.

Yet, as Lipton (1991) and other authors have emphasized, even the best available explanation is not always rationally acceptable. In domains characterized by novelty, uncertainty, or insufficient empirical grounding, the best explanation one can offer may amount to little more than an informed conjecture—or even pure speculation. The quality of inference thus depends not on its relative optimality among known hypotheses, but on its absolute adequacy in meeting epistemic and methodological standards.

A historical example illustrates this tension well. In early animistic worldviews, natural phenomena such as the movement of the sun across the sky or the occurrence of thunderstorms were explained in terms of intentional agency—the sun as a sentient being, or thunder as the anger of gods. Within those conceptual systems, these were indeed the best available explanations, since alternative mechanistic or astronomical accounts were not yet conceivable. Nevertheless, such explanations are methodologically inadequate from the standpoint of modern science because they fail to satisfy the essential criteria of empirical testability, causal coherence, and predictive power.

Therefore, while IBAE captures a more realistic model of human explanatory reasoning than idealized IBE, it also highlights a fundamental epistemic constraint: the availability of explanations is historically and cognitively bounded. Scientific progress often depends precisely on expanding this space of availability—by introducing new conceptual resources, methodological tools, or theoretical frameworks that enable the formulation of better explanations than were previously possible.

In this light, the evolution from animistic speculation to heliocentric astronomy or from vitalism to molecular biology illustrates a broader pattern: rational explanation is not static but dynamic, expanding through the iterative cycle of abduction, deduction, and induction. Abduction generates conjectural hypotheses; deduction derives their empirical consequences; induction tests and refines them. IBAE thus marks the context-bound nature of abductive reasoning—it represents the best explanation one can formulate given the current state of knowledge, but not necessarily the best explanation simpliciter.

The distinction between Inference to the Best Explanation (IBE) and Inference to the Best Available Explanation (IBAE) has profound implications for artificial intelligence, particularly for systems that aim to emulate or augment human reasoning. In computational contexts—such as abductive logic programming (ALP), Bayesian reasoning, and neuro-symbolic inference frameworks—the concept of “availability” translates directly into the boundedness of hypothesis spaces and the constraints of representational languages.

Just as human reasoners can only choose among the explanations they can conceive, an AI system can only infer among the hypotheses it is able to generate or represent within its formalism. Hence, the system’s abductive reasoning process operationalizes IBAE rather than ideal IBE. The "best explanation" the model arrives at is the best available given (1) its background knowledge base, (2) its hypothesis-generation rules, and (3) its evaluation criteria (such as likelihood, plausibility, or explanatory coherence).

In abductive logic programming (Kakas & Mancarella, 1990), this principle is evident in the structure of the inference cycle:

Abductive generation: The system proposes candidate explanations—hypotheses that, when combined with background knowledge, entail the observed data.

Deductive testing: The implications of each hypothesis are deduced and checked against constraints.

Inductive evaluation: Empirical or probabilistic measures assess which hypotheses remain consistent with evidence.

Here, the availability constraint manifests through the space of abductive hypotheses the system can construct—defined by its symbolic vocabulary, its logical rules, and its computational resources. Thus, the inferential behavior of an ALP system corresponds not to an ideal IBE, which presupposes access to all possible explanations, but to an IBAE process bounded by representational and algorithmic feasibility.

Inductive inferences in the narrow sense are well-investigated, but their inferential power is limited. With their help it is possible to reason from regularities observed in the past to unobserved or future instances of these regularities, but it is not possible to infer conclusions containing new concepts expressing un observed properties that are not contained in the premises. These inferences are conceptually creative. They are needed in science whenever one reasons from the observed phenomena to theoretical concepts. Theoretical concepts in science describe unobservable properties (e.g., electric forces) or structures (e.g., electrons) that explain the observed phenomena in a unified way. It was an important insight of the post-positivistic philosophy of science that these theoretical concepts cannot be reduced to observable concepts via chains of definitions (see Carnap 1956; Hempel 1951; Stegmüller 1976; French 2008; Schurz 2021). Thus the justification of explanations introducing the oretical concepts cannot be based on conceptual analysis, but must take the form of an ampliative inference.

Modern neuro-symbolic AI systems (Bader & Hitzler, 2005; d’Avila Garcez et al., 2019) face similar epistemic limitations. Even when neural networks are used to expand the hypothesis space by generating candidate patterns or latent variables, the symbolic reasoning layer can only evaluate those that fit within its logic schema. The model therefore performs an approximation to abduction, balancing between expressive generativity (neural) and logical evaluability (symbolic). This interplay mirrors the philosophical IBAE trade-off: the system can only infer the best explanation among those currently expressible and computationally tractable.

Furthermore, the evaluation criterion—what counts as the “best” explanation—must also be contextually defined. In philosophy, explanatory virtues include simplicity, coherence, and unification (Lipton, 1991); in AI, analogous metrics include likelihood, posterior probability, minimality, or information gain. As in human inquiry, a system’s “rational acceptability” depends on whether its best available explanation satisfies the methodological standards relevant to its domain—e.g., causal adequacy in science, logical consistency in expert systems, or interpretability in explainable AI.

Seen through this lens, the evolution of AI reasoning systems can be interpreted as an ongoing attempt to expand the availability space—to make systems capable of generating and evaluating increasingly complex, context-sensitive, and semantically rich hypotheses. Advances in LLMs, probabilistic logic, and symbolic–neural hybrids all contribute to this expansion, approximating the human process of abductive discovery within formal computational frameworks. In doing so, AI research effectively continues the Peircean program: integrating abduction for hypothesis generation, deduction for consequence derivation, and induction for empirical validation—a triadic cycle now realized not only in human thought but also in machine reasoning.

HaluCheck is introduced as a visualization framework for assessing and prominently displaying the likelihood of hallucination in model outputs. It allows users to select among multiple LLMs, providing flexibility for different tasks and preferences. The system integrates a diverse set of hallucination-evaluation metrics, enabling users to compute and compare likelihood scores using alternative methods. By allowing users to switch between these evaluators, HaluCheck supports experimentation with different assessment strategies and helps identify the most effective approach for a given use case.