Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

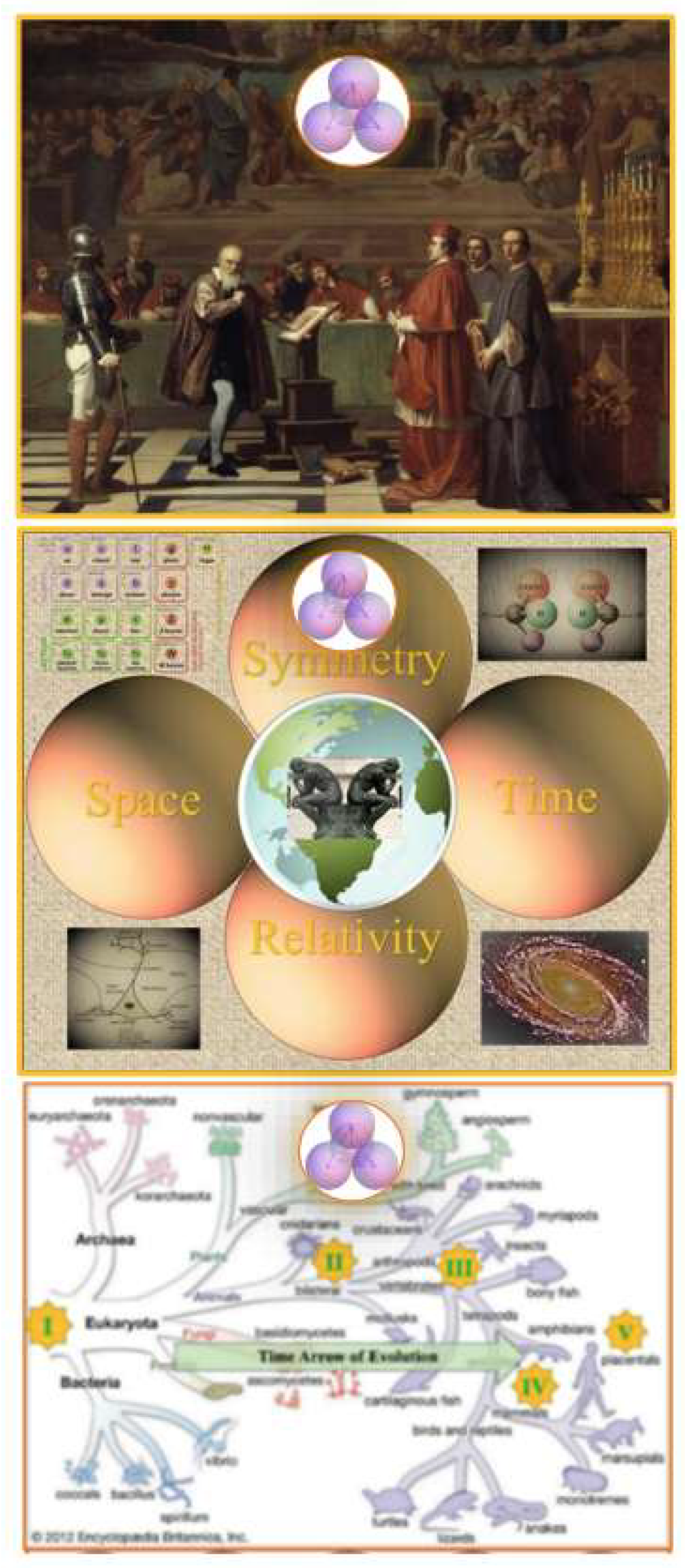

The Tails of Galileo Ideas

From Galileo to Quantum Physics

Biological Relativity

Phase Transition (Physics and Biology)

Scale Relativity (Physics and Biology)

Biological Frame of Reference

Conclusion

Appendix I.

Abbreviations

References

- [Euclid. 2022] Book by Euclid (Author), Dana Densmore (Editor), T.L. Heath (Translator). Publisher: Green Lion Press 2022. 529 pg.

- Galileo, 1632–Gailei, G. “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems” Modern Library Science Classics ed.). 1632. 586 pg.

- [Thompson. 1996] Book by Thompson, A, C. Minkowski Geometry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 368 pg.

- [Cropper. 2004] Book by Cropper, W.H. Great Physicists. The Life and Times of Leading Physicists from Galileo to Hawking. 512 pg.

- [Pas. 2023] Book by Heinrich Päs. The One: How Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics. Publisher: Basic Books 2023.

- Einstein, 1954–Einstein, A. “Ideas and Opinions by Albert Einstain”. Pg. 271 New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. NY. 1954, 1985. 80 pg.

- Wigner, 1967–Winger E.P. Scientific Essays “Symmetries and Reflections: Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 1967. Pg. 193-207.

- Samaroo, 2018–Samaroo. R. “The principle of equivalence as a criterion of identity” Synthese. 2018, 197(8):3481–3505. [CrossRef]

- Brading et al. 2023–Brading, K.; Castellani, E. and Teh, N. “Symmetry and Symmetry Breaking”. Stanford Encycl. of Philosophy Archive. {https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2024/index.html) Published in. 2023.

- Fay, 2015–Fay, S. “An easy journey from Galilean to General Relativity”. arXiv:1511.07485v1 [physics.pop-ph], 2015. [CrossRef]

- Shahen, 2015–Shahen, H. “Galileo and the equivalence principle: a faulty argument with the correct conclusion”. European Journal of Physics, 2015, 36(6), 065044. [CrossRef]

- Ciufolini et al. 2019–Ciufolini, I.; Matzner, R., Paolozzi, A. et al. “Satellite Laser-Ranging as a probe of fundamental physics”. Sci. Reports 2019, 9, 15881. [CrossRef]

- Norton, 1985–Norton, J. “What was Einstein’s Principle of Equivalence?” John Norton Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 1985, 16 (3), 203, 203-246, Printed in Great Britain. [CrossRef]

- Smarandache, 2013–Smarandache, F. “Unsolved Problems in Special and General Relativity (22 collected papers). Education Publishing ISBN: 9781599732206, 2013.

- Blennow. 2021–Blennow, M. “300 Problems in Special and General Relativity” 1st Edition Publisher: Cambridge University Press 2021.

- Cai, Y.Q. and Papini, G. The effect of space-time curvature on Hilbert space. General Relativity and Gravitation 1990, 22(3), 259-267, Y. Q. Cai and Giorgio Papini. [CrossRef]

- Hilbert "Die Grundlagen der Physik" [Foundations of Physics], Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen – Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse (in German), 2015, 3: 395–407.

- Browne, 2020–Browne, K.M. “Galilei proposed the principle of relativity, but not the “Galilean transf7rmation” Am. J. Phys. 2020, 88, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Machamer & Miller, 2021–Machamer, P. and Miller, D.M. “Galileo Galilei”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy {https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/galileo/} First published 2005; substantive revision, 2021.

- Ramírez, 2024–Ramírez, S.M. “Galileo’s Ship and The Relativity Principle.” Nous.2024. [CrossRef]

- [Nolte. 2018] Book by Nolte, D.D. Galileo Unbound (Science Answers Why. A Path Across Life, the Universe and Everything. Oxford University Press 2018.

- Gray & Ferreirós, 2021–Gray, J. and Ferreirós, J.” Epistemology of Geometry”. Stanford Encycl. Of Philosophy. First published 2013; substantive revision in 2021.

- [Gibson & Pollard. 1980] Book by Gibson, W.M. and Pollard, B.R. Symmetry principles in elementary particle physics. Cambridge University Press. 1980. 402 pg.

- Thorngren & Else, 2018–Thorngren R. and Else, D.V. “Gauging Spatial Symmetries and the Classification of Topological Crystalline Phases”. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 011040. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury & Perdew, 2021–Chowdhury, S.T.R. and Perdew, J.P. “Spherical vs non-spherical and symmetry-preserving vs symmetry-breaking densities of open-shell atoms in density functional theory”. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 234110. [CrossRef]

- Wesson, 2003–Wesson, P.S. “The Equivalence Principle as a Symmetry”. Gen.Rel.Grav. 2003, 35 (2003) 307-317. [CrossRef]

- Wolkowski, 2008–Wolkowski, Z.W. “Symmetry and its consequences: from Pierre Curie to transdisciplinarity”. Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie, 2008, 33(1-2) 193–196 2008.

- Petkov, 2012–Petkov, V. (Editor). Space and Time. Minkowsky Papers on Relativity. Translated by Lewertoff F. and Petkov, V. Translated by Robert D. Martin. Publisher: Minkowski Inst. Press 2012.

- Editorial. 2018–Editorial. “Celebrate the mathematics of Emmy Noether. Nature. 2018, 561, 149-150. [CrossRef]

- Book Lee Phillips.” Einstein’s Tutor”. The Story of Emmy Noetter and the Invention of Modern Physics. Publisher: PublicAffairs. First Edition 2024.

- [Yousef. 2019] Book by Yousef, M.H. Time Chest: Particle-Wave Duality: from Time Confinement to Space Transendence. Publisher: Independently published 2019.

- Zhao et al. 2023–Zhao, D.; Xu, M.; Dai, K.; Liu, H.; Jiao, Y. and Xiao, X. “The preparation of chiral carbon dots and the study on their antibacterial abilities: Materials Chemistry and Physics 2023, 295, 127144. [CrossRef]

- Lee & Yang, 1956–Lee, T.D and Yang, C.N. “Question of Parity Conservation in Weak Interactions”. Physical Review 1956, 104, 254. [CrossRef]

- Wu et al. 1957–Wu CS, Ambler E, Hayward RW, Hoppes DD, Hudson RP. “Experimental test of parity conservation in beta decay”. Phys. Rev. 1957, 105, 1413–1415. [CrossRef]

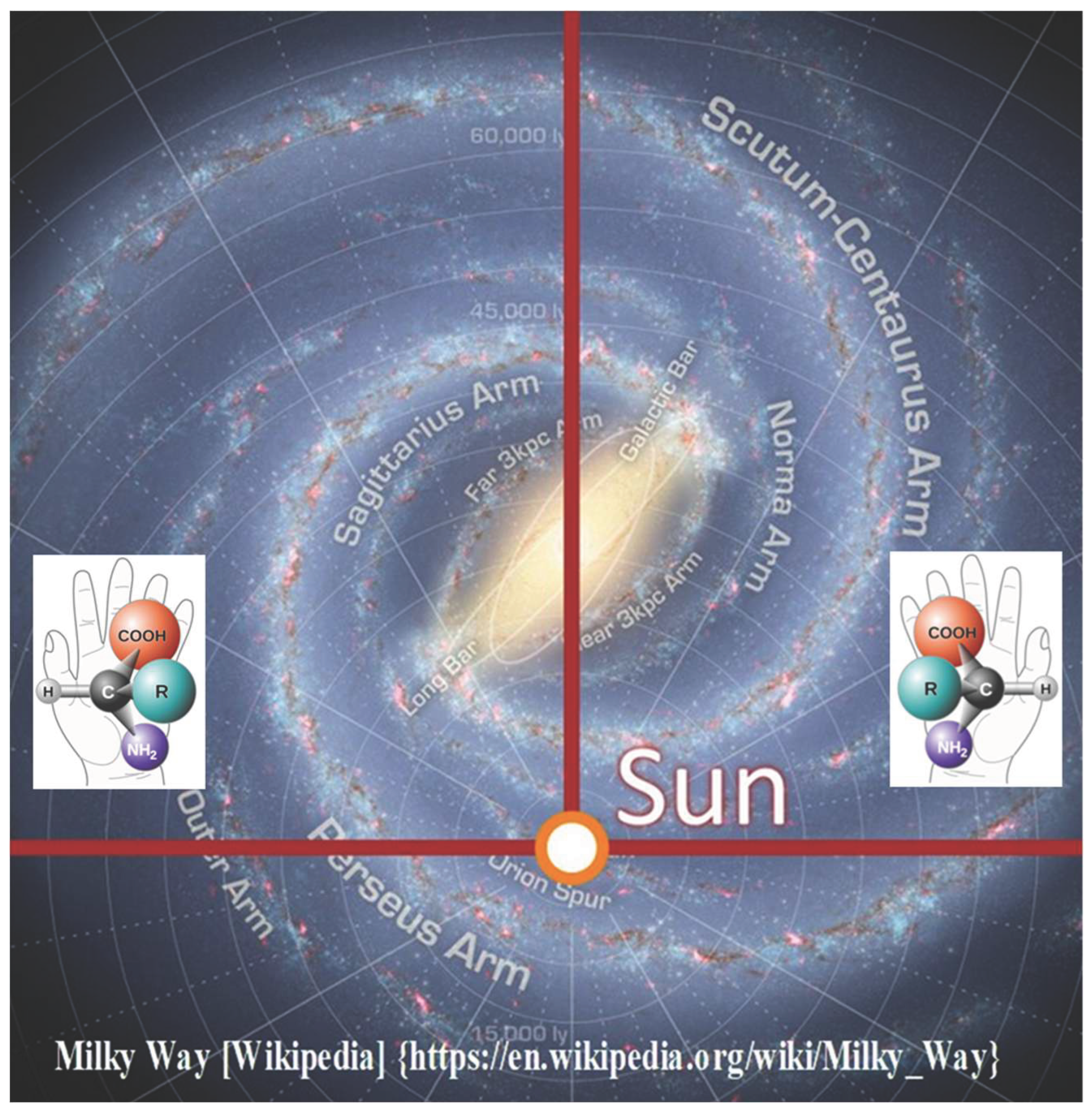

- Kondepudi & Durand, 2001–Kondepudi D.K. and Durand D.J. “Chiral asymmetry in spiral galaxies? “ Chirality 2001, 13, 351–356. [CrossRef]

- Popa et al. 2010–Popa, R.; Cimpoiasu, V.M. and Scorei, I-r. Consequences of expanding chirality to include spin isomery (The dilemma of broadening chirality into handedness). Annals of the University of Craiova, Physics 2010, 20(1):64-72.

- Djordje and Chia-Hsiung, 2004–Djordje, M. and Chia-Hsiung. T. A general theory of quantum relativity. Physics Letters B, 2004, 581(1-2), 111-118. [CrossRef]

- Daus et al. 2020–Daus, T.; Hebecker, A.; Leonhardt, S. and March-Russell, J. “Towards a Swampland Global Symmetry Conjecture using weak gravity”. Nuclear Physics B 2020, 960, 115167. [CrossRef]

- Dragan & Ekert, 2020–Dragan, A. and Ekert, A. ‘Quantum Principle of Relativity.” New Journal of Physics 2020, 22, 033038. [CrossRef]

- Wetzel et al. 2013–Wetzel, A.R.; Tinker, J.L.; Conroy, C. and Bosch, F.C. “Galaxy evolution in groups and clusters: satellite star formation histories and quenching time-scales in a hierarchical Universe”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2013, 432(1)1, 336–358. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, 2023–Dyakin, V.V. “Fundamental Cause of Bio-Chirality: Space-Time Symmetry—Concept Review”. Symmetry 2022, 15(1):79. [CrossRef]

- [Knoflacher. 2024] Book by Knoflacher, M. Relativity of Evolution. Translation of an updated and revised version of the original German work: Relativität der Evolution, ISBN 978-3-662-63936-8. 2024.

- Glattfelder, 2019–Glattfelder, J.B. “The Unification Power of Symmetry”. Chapter in thr book Information—Consciousness—Reality. The Frontiers Collection. Springer, Cham. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Frattolin et al. 2021– Frattolin, J.; Watson, D.J.; Bonneuil, W.V.; Russell, M.J.; Masci, F.; Bandara, M.; Brook, B.S.; Nibbs, R.J.B. and Moore, Jr.,J.E. “The Critical Importance of Spatial and Temporal Scales in Designing and Interpreting Immune Cell Migration Assays”. Cells 2021, 10(12), 3439. [CrossRef]

- Sampathkumar & Nakamura, 2025–Sampathkumar, A. and Nakamura, M. Editorial overview: “Spatial and temporal regulation of molecular and cell biological process across biological scales”. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2025, 83, 102675. [CrossRef]

- Hansson & Åkesson, 2014–Book by Hansson, L-A. and Åkesson, S. (Edotors). Animal Movement Across Scales. Publisher: Oxford University Press 2014. 294 pg.

- Hameroff & Penrose, 2014–Hameroff, S. and Penrose, R. Review. “Consciousness in the universe: A review of the ‘Orch OR’ theory”. Physics of Life Reviews 2014, 11(1) 39-78. [CrossRef]

- Mondal & Kolomeisky, 2025–Mondal, A. and Kolomeisky, A.B. Review. “Microscopic origin of the spatial and temporal precision in biological systems”. Biophysical Reports, 2025, 5(1),100197. [CrossRef]

- Shkursky, 2025–Shkursky, A. “Generalized Theory of Cognitive Relativity: Bridging Philosophical Tradition, Cognitive Science, and Artificial Intelligence through Pure Reason”. OSF PREPRINT 2025 {https://osf.io/preprints/osf/8kanm v1} See Phil ArXive.

- Zaidi et al, 2013–Zaidi, Q.; Victor, J.; McDermott, J. Geffen, M.; Bensmaia, S. and Cleland., T.A. “Perceptual Spaces: Mathematical Structures to Neural Mechanisms”. J Neurosci. 2013, 33(45), 17597–17602. [CrossRef]

- Pizzolant et al. 2024–Pizzolante, M., Bartolotta, S., Sarcinella, E.D. et al. “Virtual vs. real: exploring perceptual, cognitive and affective dimensions in design product experiences”. BMC Psychol 12, 10 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, 2017–Ahamed, S.A. “Quantum Flow Theory of Knowledge, Chapter in Evolution of Knowledge Science. Psychological Space. Science Direct. 2017 {https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-}.

- Ferreira & Vermo, 2017–Ferreira, R.R and Vermot, J. Review. “The balancing roles of mechanical forces during left-right patterning and asymmetric morphogenesis”. Mechanisms of Development 2017, 144, Part A, 71-80. [CrossRef]

- Levin et al, 2016–Levin, M.; Klar, A.J.S. and Ramsdell, A.F. Introduction to provocative questions in left–right asymmetry. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016, 371(1710):20150399. [CrossRef]

- [Bohr. 1958/2010] Book by Niels Bohr (Author)Atomic Physics and Human Knowledge Publisher: Dover Publications 2010. 112 pg.

- Ellis, 2013–Ellis, G.F.R. The arrow of time and the nature of spacetime. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2013, 44(3)242-262. [CrossRef]

- Jiang & Moubayidin, 2022–Jiang, Y. and Moubayidin, L. Floral symmetry: the geometry of plant reproduction. Emerg Top Life Sci 2022, 6(3), 259–269. [CrossRef]

- Lim & Lee, 2022–Lim, S. and Lee, S. Chemical Modulators for Targeting Autism Spectrum Disorders: From Bench to Clinic. Molecules 2022, 27(16), 5088. [CrossRef]

- Conway et al. 2016–Conway, L.G.; Repke, M.A. and Houck, S.C. Psychological Spacetime: Implications of Relativity Theory for Time Perception. SAGE Open 2016, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Pillai & Jirsa, 2017–Pillai, A.S. and Jirsa. V.K. Perspective. Symmetry Breaking in Space-Time Hierarchies Shapes Brain Dynamics and Behavior. Neuron. 2017, 94(5), 1010-1026. [CrossRef]

- Glicksoh, 2022 -,Glicksoh, J. From illusion to reality and back in time perception. Front Psychol. 2022; 13: 1031564. [CrossRef]

- Buzsáki & Llinás, 2017–Buzsáki, G. and Llinás, R. Space and time in the brain. Science. 2017, 358(6362): 482–485. [CrossRef]

- Rosandić & Paar, 2023–Rosandić, M. and Paar, V. The Supersymmetry Genetic Code Table and Quadruplet Symmetries of DNA Molecules Are Unchangeable and Synchronized with Codon-Free Energy Mapping during Evolution. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14(12), 2200. [CrossRef]

- Harlander et al. 2023–Harlander R, Martinez JP, Schiemann G. "The end of the particle era?" The European Physical Journal H. 2023 48(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin et al. 2021–Dyakin VV, Wisniewski TM, Lajtha A. (2021). “Racemization in Post-Translational Modifications Relevance to Protein Aging, Aggregation and Neurodegeneration: Tip of the Iceberg”. Symmetry. 2021, 13, 455. [CrossRef]

- Blackmond DG, Klussmann, 2007–Blackmond DG, Klussmann M. (2007). “Spoilt for choice: assessing phase behavior models for the evolution of homochirality”. Chemical Communications. 2007, 39, 3990–3996. [CrossRef]

- Whitesides & Boncheva, 2002–Whitesides GM, Boncheva M. (2002). “Beyond molecules: Self-assembly of mesoscopic and macroscopic component”s. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99(8):4769–4774. [CrossRef]

- Jeffery & Rovelli, 2020–Jeffery K.J. and Rovelli C. (2020). “Transitions in Brain Evolution: Space, Time and Entropy”. Trends Neurosci. 2020, 43(7), 467–474. [CrossRef]

- Pietruszka, 2021–Pietruszka MA. (2021).” Non-equilibrium phase transition at a critical point of human blood”. Scientific Reports. 2021, 11(1),22398. [CrossRef]

- Englert & Brout, 1964–Englert F and Brout R. (1964). “Broken Symmetry and the Mass of Gauge Vector Mesons”. Physical Review Letters. 1964, 13(9), 321–323. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, 1964 – Higgs. PW. “Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons”. Physical Review Letters. 1964, 13(16):508–509. [CrossRef]

- Stokes et al. 2023–Stokes, A.; Riley, H. and Nazir, A. “The gauge-relativity of quantum light, matter, and information”. Open Systems & Information Dynamics 2023, 30, 2350016. [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Gomes, 2025–De Andrade Gomes, H. Gauge “Theory and the Geometrisation of Physics” Series: Elements in the Philosophy of Physics. Cambridge Elements 2025. Publisher: Cambridge University Press. 2025 Henrique De Andrade Gomes.

- Guralnik et al. 2025–Guralnik GS, Hagen CR, Kibble TWB. "Global Conservation Laws and Massless Particles." Physical Review Letters. 13(20):585–587. [CrossRef]

- Kuno et al. 2022–Kuno J, Ledos N, Bouit PA, Kawai T, Hissler M, Nakashima T. (2022). “Chirality Induction at the Helically Twisted Surface of Nanoparticles Generating Circularly Polarized Luminescence”. Chemistry of Materials. 2022, 34(20), 9111–9118. [CrossRef]

- Anlas & Trivedi, 2021–Anlas K and Trivedi V. (2021). Studying evolution of the primary body axis in vivo and in vitro. eLife. 2021, 10, e69066. [CrossRef]

- Landau et al.1980–Landau L.D ; Lifshitz EM, et al. Statistical Physics (Course of Theoretical Physics. 1980, 5(1). 3rd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1980.

- Livio, 2012–Livio M. (2012). “Why symmetry matters”. Nature. 2012, 490:472–473. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin, 2021–Dyakin VV, Dyakina-Fagnano NV, Mcintire LB, Uversky VN. (2021). "Fundamental Clock of Biological Aging: Convergence of Molecular, Neurodegenerative, Cognitive and Psychiatric Pathways: Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics Meet Psychology. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 23(1),285. [CrossRef]

- Grimes D.T. and Burdine, 2017–Grimes D.T. and Burdine R.D. (2017). Left–Right Patterning: Breaking Symmetry to Asymmetric Morphogenesis. Trends in Genetics. 2017, 33(9), 616–628. [CrossRef]

- Dyakin & Dyakina-Fagnano, 2024–Dyakin V.V, Dyakina-Fagnano NV. (2024). "Enigma of Pyramidal Neurons: Chirality-Centric View on Biological Evolution. Congruence to Molecular, Cellular, Physiological, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions”. Symmetry. 2024, 16(3):355. [CrossRef]

- Gross, 1996–Gross, D.J. The role of symmetry in fundamental physics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14256–1425. [CrossRef]

- Auffray & Nottale, 2008–Auffray, C. and Nottale, L. Review. “Scale relativity theory and integrative systems biology: 1: Founding principles and scale laws”. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2008, 97(1), 79-114. [CrossRef]

- Pinna et al. 2022–Pinna, B.; Porcheddu, D. and Skilters, J. Similarity and Dissimilarity in Perceptual Organization: On the Complexity of the Gestalt Principle of Similarity. Vision, (MDPI) 2022, 6(3), 39. [CrossRef]

- Lin,1996–Lin S-K. “Correlation of Entropy with Similarity and Symmetry”. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1996, 36, 3, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Adam et al. 2022–Adlam, E.; Uribarri, L. and Allen, N. “Symmetry and control in thermodynamics”. AVS Quantum Sci. 2022, 4, 022001. [CrossRef]

- Holl, 2015–Holl, G. “A new paradigm for animal symmetry”. Interface Focus. 2015. 5(6): 20150032. [CrossRef]

- Segal, 1972–Segal, H.L. “On the origin of stereospecificity in biological systems”. FEBS Lett. 1972 20(2), 255-256. [CrossRef]

- Savin, 2010–Savin, D.N.; Tseng, S-C. and Morton, S.M. “Bilateral Adaptation During Locomotion Following a Unilaterally Applied Resistance to Swing in Nondisabled Adults”. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104(6), 3600–3611. [CrossRef]

- Biazzi, 2023–Biazzi, R.B.; Fujita, A. And Takahashi, D.Y. “Convergent Evolution in Silico Reveals Shape and dynamic principles of directed locomotion”. eLife. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, 2014–Watanabe, H.; Schmidt, H.A.; Kuhn, A.; Höger, S.K.; Kocagöz, Y.; Laumann-Lipp, N.; Ozbek, S. and Holstein, T.W. “Nodal signaling determines biradial asymmetry in Hydra”. Nature 2014, 515(7525), 112–115. [CrossRef]

- Will, 2014–Will, B. “Hypothesis and Theory article. Moving from hand to mouth: ech0 phonology and the origin of language”. Front. Psychol. Sec. Psychology of Language 2014, 5. [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, 2008–Wertheim, A. “Perceiving motion: relativity, illusions and the nature of perception”. Netherlands Journal of Psychology Dordrecht 2008, 64(3), 119-125. [CrossRef]

- Falter & Bailey, 2012–Falter, C.M. and Bailey, A.J. “Perception of mirror symmetry in autism spectrum disorders”. Autism. 2012. 16(6):622-6. [CrossRef]

- Herzog & Öğmen, 2013, Herzog M.H. and Öğmen, H. Edited by Johan Wagemans. “Apparent motion and reference frames”. Oxford Handbook of Perceptual Organization. Oxford University Press 2013.

- Dokic & Pacherie, 2006–Dokic, J. and Pacherie, E. “On the very idea of a frame of reference. M. Hickmann &S. Robert. Space in Languages: Linguistic systems and cognitive categories. Typological Studies in Language 2006, 66, 259–280. [CrossRef]

- Xie, 2009–Xie, C-X.; Liu, Q.; Li, A-J.; Tao, WD. and Sun, H-J. “Frame of reference in the mental representation of object layout”. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 2009, 41(5), 414–423. [CrossRef]

- Robinson., 2010–Robinson, D.K. (2010). “Fechner's "inner psychophysics." History of Psychology, 2010, 13(4), 424–433. [CrossRef]

- Marks, 2011–Marks, L.E. “Brief History of Sensation and Reward.” Chapter 2A in the book Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward. Gottfried JA, editor. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2011.

- Aitken, 2020–Aitken, F.; Turner, G. and Kok, P. Prior “Expectations of Motion Direction Modulate Early Sensory Processing”. The J. of Neurosci. 2020, 40(33): 6389–6397. [CrossRef]

- Haarsma, et al. 2020–Haarsma, J.; Knolle, F.; Griffin, J.D.; Taverne, H.; Mada, M.; Goodyer, I.M. et al. “Influence of Prior Beliefs on Perception in Early Psychosis: Effects of Illness Stage and Hierarchical Level of Belief”. J Abnorm Psychol. 2020, 129(6): 581–598. [CrossRef]

- Cowan & Furnstahl, 2022–Cowan, J.A. and Furnstahl, R.L. “Origin of Chirality in the Molecules of Life”. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2022, 6, 11, 2575–2581. [CrossRef]

- Wan et al. 2016–Wan, L.Q.; Chin, A.S.; Worley, K.E. and and Ray, P. “Cell chirality: Emergence of asymmetry from cell culture.” Philosophical Transactions B 2016, 371(1710), 20150413. [CrossRef]

- Levin & Mercola, 1998–Levin, M and Mercola, M. ‘The compulsion of chirality: toward an understanding of SM–right asymmetry”. Genes & Dev. 1998. 12: 763-769 12:763–769. [CrossRef]

- Petrov et al. 2015–Petrov, A.S.; Gulen, B.; Norris, A.M.; Kovacs, N.A.; Bernier, C.R.; Lanier, K.A.; Fox, G.E. et al. History of the ribosome and the origin of translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci (PNAS) U S A. 2015, 112(50): 15396–15401. [CrossRef]

- Torday & Miller, 2016–Torday, J.S. and Miller, Jr., W.B. “Biologic Relativity: Who is the observer and what is observed?” Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016, 121(1):29-34. [CrossRef]

- Book George Mather. “Foundations of Perception”. Publisher: Psychology Press. 2006.

- Drissi-Daoudi et al. 2021 -Drissi-Daoudi, L.; Öğmen, H. and Herzog, M.H. “Features integrate along a motion trajectory when object integrity is preserved”. J Vis. 2021, (12):4. [CrossRef]

- Zadra & Clore, 2011–Zadra, J.R. and Clore, G.L. “Emotion and Perception: The Role of Affective Information”. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2011, 2(6): 676–685. [CrossRef]

- Nanno & Yanagisawa, 2019–Nanno, D. and Yanagisawa, H. “Effect of assistive method on the sense of fulfillment with agency: Modeling with flow and attribution theory”. arXiv:1907.01934 [cs.HC], 2019. [CrossRef]

- Giovannoli, 2024–Giovannoli, J. Lung cancer screening: focus on some psychological aspects, preliminary results. The J. of Tobacco Science 2024, 22(2), 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Oosterwijk et al. 2009–Oosterwijk, S.; Lindquist, K.A.; Anderson, E.; Dautoff, R.; Moriguchi, Y. and Barretta, L.F. “States of mind: Emotions, body feelings, and thoughts share distributed neural networks.” Neuroimage. 2012, 62(3):2110-28. [CrossRef]

- Koonin, 2009–Koonin EV. “Darwinian evolution in the light of genomics”. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1011–1034. [CrossRef]

- Smith, 1963–Smith, G.W. “Process — “A Biological Frame of Reference for The Study of Behavior.” Scandinavian J. of Pschology. 1963, 4(1), 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Kersten et al. 2004–Kersten, D.; Mamassian, P. and Yuille, A. “Object Perception as Bayesian Inference”. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004:55:271-304. [CrossRef]

- Buhusi & Meck. 2009–Buhusi, C.V. and Meck, W.H. “Relativity Theory and Time Perception: Single or Multiple Clocks?” PLOS ONE 2009. [CrossRef]

- Book by Rochelle Forrester. “Sense Perception and Reality–A theory of Perceptual Relativity, Quantum Mechanics and the Observer Dependent Universe”. Publisher: Best Publications Limited; Second Edition. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lanzerath 2016 -,Lanzerath, D. (2016). Life Sciences, Philosophy of. In the book by ten Have, H. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Bioethics. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Rodne, 2022–Rodne, B. “Origin of Life Resulting from General Relativity, with Neo-Darwinist Reference to Human Evolution.” 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4133390 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4133390. [CrossRef]

- Lori, 2022–Lori, N. Darwinian standard model of physics obtains general relativity. Quantum Information processing 2022, 21(112). [CrossRef]

- Laurent et al. 2021–Laurent, G.; Lacoste, D.; Gaspard, P. “Emergence of homochirality in large molecular systems.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2012741118. [CrossRef]

- Fewster, 2025–Fewster, C.J.; Janssen, D.W.; Loveridge, L.D.; Rejzner, K. & James Waldron, J. Quantum Reference Frames, Measurement Schemes and the Type of Local Algebras in Quantum Field Theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 2025, 406, 19. [CrossRef]

- Kurakin, 2011–Kurakin, A. “The self-organizing fractal theory as a universal discovery method: The phenomenon of life”. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2011, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Giacomini et al. 2019–Giacomini, F., Castro-Ruiz, E. & Brukner, Č. “Quantum mechanics and the covariance of physical laws in quantum reference frames. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 494. [CrossRef]

- Capozziello & Lattanzi, 2006–Capozziello, S. and Lattanzi, A.” Spiral Galaxies as Enantiomers: Chirality, an Underlying Feature in Chemistry and Astrophysics”. Chirality 2006, 18(1), 17-23. [CrossRef]

- Helman. 2018. Galactic distribution of chirality sources of organic molecules. Acta Astronautica 2018, 151, 595-602 Daniel S. Helman.

- [Bostic, 2025] Book by Devin Bostick. “Quantum Resonance Dynamics (QRD): A Reframing of Quantum Mechanics Through Structured Resonance: The Hidden Structure Behind Mass, Energy, and the Chiral Nature of Reality.” 2025.

- Alexeev, 2017–Alexeev, B.V. “The Dark Matter Problem” (4.3.1 Galaxy Rotation Curves). Chapter 4 Nonlocal Astrophysics (Dark Matter, Dark Energy and Physical Vacuum) 2017, 141-176. [CrossRef]

- Nelson & William. 2024–Nelson, A.H. and William, P.R. “Recent observations of the rotation of distant galaxies and the implication for dark matter”. Astronomy & Astrophysics (A&A) 2024, 687, A261. [CrossRef]

- Brading & Castellani, 2007–Brading, K. and Castellani, E. “Symmetries and Invariances in Classical Physics”. Chapter In Philosophy of Physics Handbook of the Philosophy of Science 2007, Pg. 1331-1367.

- Huggett, et al. 2021–Huggett, N.; Carl Hoefer, C. and James Read, J. “Absolute and Relational Space and Motion: Post-Newtonian Theories”. Stanford Encycl. of Phil. 2021.

- Kind, 2008 -] Kind, S. “Spinor Relativity”. Int J Theor Phys 2008, 47, 3341–3390. [CrossRef]

- Rose. 2023–Rose, H. Chapter One–Novel theory of the structure of elementary particles Adv. in Imaging and Electron Physics 2023, 225, 1-61. [CrossRef]

- Bell & Korté, 2024–Bell, J.L. and Korté, H. “Herman Weyl”. Sanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2024 {https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weyl/}.

- Chen & Wang.,2024–Chen, D-M. and Wang, L. “Quantum Effects on Cosmic Scales as an Alternative to Dark Matter and Dark Energy”. Universe (MDPI) 2024, 10(8), 333, 1-39. [CrossRef]

- Nath. 2024–Nath, P. “Particle physics and cosmology intertwined”. Entropy (MDPI) 2024, 26(2),110. [CrossRef]

- Genet. 2022–Genet, C. Chiral Light–Chiral Matter Interactions: an Optical Force Perspective. ACS Photonics 2022, 9(2), 319–332. [CrossRef]

- Petelin, & Thumm. 2023 -Petelin, M. and Manfred Thumm. M. On the Ecclesiastes’-Proclus’-Galileo’s Relativistic Approach to the Space-Time-Symmetry. Editor(s) Dr. Jelena Purenovic. Fundamental Research and Application of Physical Science 2023, 2, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Albert. 2025–Albert, D.Z. The special theory of relativity and the general theory of relativity (GRT) in philosophy of physics in the philosophy of space and time. Britannica {https://www.britannica.com/topic/philosophy-of-physics/The-special-theory-of-relativity }.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).