1. Introduction

Poor diet is the leading risk factor for death worldwide associated with over 10 million premature deaths annually [

1]. Excessive salt, sugar, and red and processed meats specifically are linked to chronic inflammation accelerating atherosclerosis which underlies the expanding epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) of hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that such unhealthy diets cost

$8 trillion every year or nearly 10% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) [

2]. Conversely, healthy diets followed by sufficient exercise, smoking avoidance, and moderated alcohol intake as part of the preventive social determinants of health (SDoH) drive approximately 80% of health outcomes, leaving 20% from acute medical care treatments [

3]. 85% of clinicians report they are not sufficiently trained or competent to provide healthy nutrition assessment, education, or support for their patients, with 75% of medical schools lacking any required nutrition classes for future clinicians [

4]. Funding trends suggest that these health trends will only continue for the foreseeable future. Of the nearly

$10 trillion health sector, the United States accounts for nearly half of it by revenue and spending, which is almost twice as much per capita as other large developed countries despite worse health outcomes—with almost 95% of American health expenditures going to healthcare systems delivering mostly acute medical care, with the rest going to public health that traditionally has specialized in disease prevention particularly through healthy diets [

5,

6]. Globally, 77% of the rising diet-related NCD deaths are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South, with Africa containing nearly half of them, and where most of the shortage of 11 million healthcare workers is also concentrated [

7,

8]. While high-income countries (HICs) typically face excess caloric intake as part of unhealthy diets driving NCDs, LMICs face the double-threat of these along with malnutrition from inadequate calories (impairing growth, development, cognition, and thus long-term overall health and economic productivity). Over 70% of the continents’ clinicians have emigrated to HICs in the Global North mostly to the United States and the United Kingdom, while Africa already spends less on health than its debt service costs as it is trying to cross the Digital Divide to join the modern digitalized and industrialized global economy [

9].

Solutions seem underway. Artificial intelligence or AI is rapidly emerging as history’s most disruptive, innovatively dynamic, rapidly scaled, cost-efficient, and economically productive technology that is increasingly providing transformative counter-measures to these negative health trends, especially in LMICs and underserved communities [

10]. AI already is revolutionizing industries globally. But adoption in the health sector continues to lag behind others, slowed by complex regulations, fragmented ecosystems, data security challenges, slow return on investment (ROI), and limited validated tools guiding implementation that can preserve patients’ trust and advances their wellbeing at affordable costs to them and their healthcare systems. We cannot improve what we cannot measure. Yet despite the proliferation of AI indexes for this, there are no validated full-spectrum ones to empirically inform safe, effective, and affordable AI’s embrace by the health sector, constituted by the healthcare, public health, and global health sub-sectors. Further,

AI’s speed and complexity of development is largely driven by private AI platform companies that vastly outpace healthcare systems and even governments’ capabilities to define best-practices and appropriately regulate them at the speed of relevance (amid shrinking public health and global health budgets, shunting more of the traditional societal needs of public health nutrition and wider prevention to them). Stanford University’s AI Index demonstrates the intense global competition to dominate the centralization of top AI: the United States owns nearly two-thirds of AI computing hubs, over 80% of advanced AI chips, nearly 70% of the leading models, and 12 times the private investment (as the next competitor, China, which is making significant gains catching up) [

12]

. Governments pass laws and institutions publish guidelines. But private platforms determine the bulk of daily AI priorities, operations, capabilities, applications, and trajectory. The World Health Organization (WHO) in its Nature 2025 publication outlined its Global Initiative on AI for Health (GI-AI4H) with particular LMIC focus to “harmonize governance standards” for AI as part of its larger strategic priority of accelerating the digitalization of healthcare systems worldwide through responsible, accessible, and sustainable AI in collaboration with aligned governments and companies. Yet widespread confusion persists among healthcare systems’ clinicians, executives, and policymakers especially in LMICs on how to best identify, integrate, and evolve the safe, trusted, effective, affordable, and equitable AI solutions right for their communities. This is especially true in nutrition which may be among the most effective fulcrums of public health advanced by healthcare systems, all the more so within LMICs and underserved communities which stand to benefit the most from such advances.

We therefore provide here the first known global, comprehensive, and actionable narrative review of the state-of-the-art of AI-accelerated nutrition assessment and healthy eating spanning public health nutrition for healthcare systems, generated by the first automated end-to-end empirical index for responsible health AI readiness and maturity. These twin innovations are meant to ultimately assist health actors to actually implement and benefit from the leading nutrition AI use cases. It is contextualized in the larger evolution, digitalization, and platformization of the health ecosystem globally, using the index to map the likely trajectory of nutrition AI within the ecosystem through a unique full epistemic stack of scientific, economic, and ethical analyses. The index, analysis, and review are built by a multi-national team spanning the Global North and South, consisting of current and former front-line clinicians, ethicists, engineers, executives, administrators, public health practitioners, and policymakers. It builds on our team’s January 2025 policy analysis and recommendations solicited by the WHO for responsible AI digitalization of LMIC healthcare systems [

13]

. This review codifies that earlier analysis and recommendations into a novel AI index which is then applied to reviewing nutrition AI within healthcare systems for practically advancing the health of the populations they serve.

2. Methods

2.1. Responsible Health AI Readiness and Maturity Index (RHAMI) Design

The first known full-spectrum composite AI index for health is described here—the Responsible Health AI readiness and Maturity Index (RHAMI)—to facilitate standardized, continuous, automated, and real-time multi-disciplinary and multi-dimensional strategic planning, implementation, and optimization of AI capabilities and functionalities worldwide, aligned with healthcare systems’ strategic objectives, practical constraints, and local cultural values. The ultimate strategic objectives of RHAMI are to improve population health, financial efficiency, and societal equity through a global cooperation of the public and private sectors stretching across the Global North and South. The automated RHAMI can thus allow longitudinal and customizable reviews of AI-augmented nutrition assessments and healthy eating advances even after this paper’s publication, along with other aspects of essential health services by healthcare systems for their communities. RHAMI automation is two-fold: hard (agentic AI orchestrator as a cloud-based API in Python that can be embedded in existing dataflows and modifiable for the needs of local healthcare systems with existing enterprise database management systems for real-time dashboard visualization, regardless of users’ technical expertise) and soft (education and calculator, including upskilling for staff, executives, and policymaker education on RHAMI as an analytic framework in parallel with a customizable calculator with weights that can be modified according to local healthcare system needs).

2.2. RHAMI Generated Narrative Review

An AI unassisted comprehensive literature review was performed from 2005 to 2025 using EBSCO, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, PubMed, and the citations of identified studies by experts specialized in the subject matter. To better democratize and sustain this methodology for more healthcare system actors worldwide regardless of technical background, we also performed an AI assisted literature review using the free ChatGPT large language model (LLM), in addition to reviewing news articles, social media, books, and Common Crawl for the most up-to-date advances. In both review tracks, the search focused on search terms associated with nutrition and AI, including: “nutrition”, “nutrition assessment”, “dietary assessment”, “healthy eating”, “healthy nutrition”, “healthy diet”, “clinical nutrition”, “personalized nutrition”, “precision nutrition”, “nutrition education”, “diet education”, “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “reinforcement learning”, “computer vision”, “agentic AI”, “orchestrator AI”, “spatial AI”, artificial general intelligence”, and “AGI”. To refine the search, AND/OR as Boolean operators were used. Hard RHAMI automated analysis was then deployed on the AI unassisted and assisted literature review tracks to identify and stratify leading responsible AI use cases in nutrition according to readiness and maturity within and with healthcare systems.

3. Results

3.1. RHAMI Design and Development

RHAMI was constructed by synthesizing the Stanford University Institute of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence’s AI Index, the International Monetary Fund’s AI Readiness Index, the Oxford Government AI Readiness Index, Microsoft’s Health AI Maturity Roadmap, Access Partnership’s Responsible AI Readiness Index, IMD’s AI Maturity Index, the African Global Center on AI Governance’s Global Index on Responsible AI, and the GSAS AI-driven Efficiency-Inequity Index then customized for the health sector [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Additional consideration was added to the typically overlooked system need of financial sustainability to improve effective planning and durable use enterprise-wide (or across the system as an organization), especially for LMIC healthcare systems and those integrated or partnered with public health and global health agencies. Continuous optimization testing was then conducted for RHAMI to confirm it exceeded performance benchmarked to the above indexes in their respective domains from their replated publications. The same iterative process was repeated with RHAMI then applied as a meta-index to confirm streamlined end-to-end analyses accurately replicated primary consensus factors driving the top-performing healthcare systems globally (balancing the often competing objectives the above individual indexes measure of patient access, health effectiveness, and financial sustainability within ethical safeguards of responsibility to the common good).

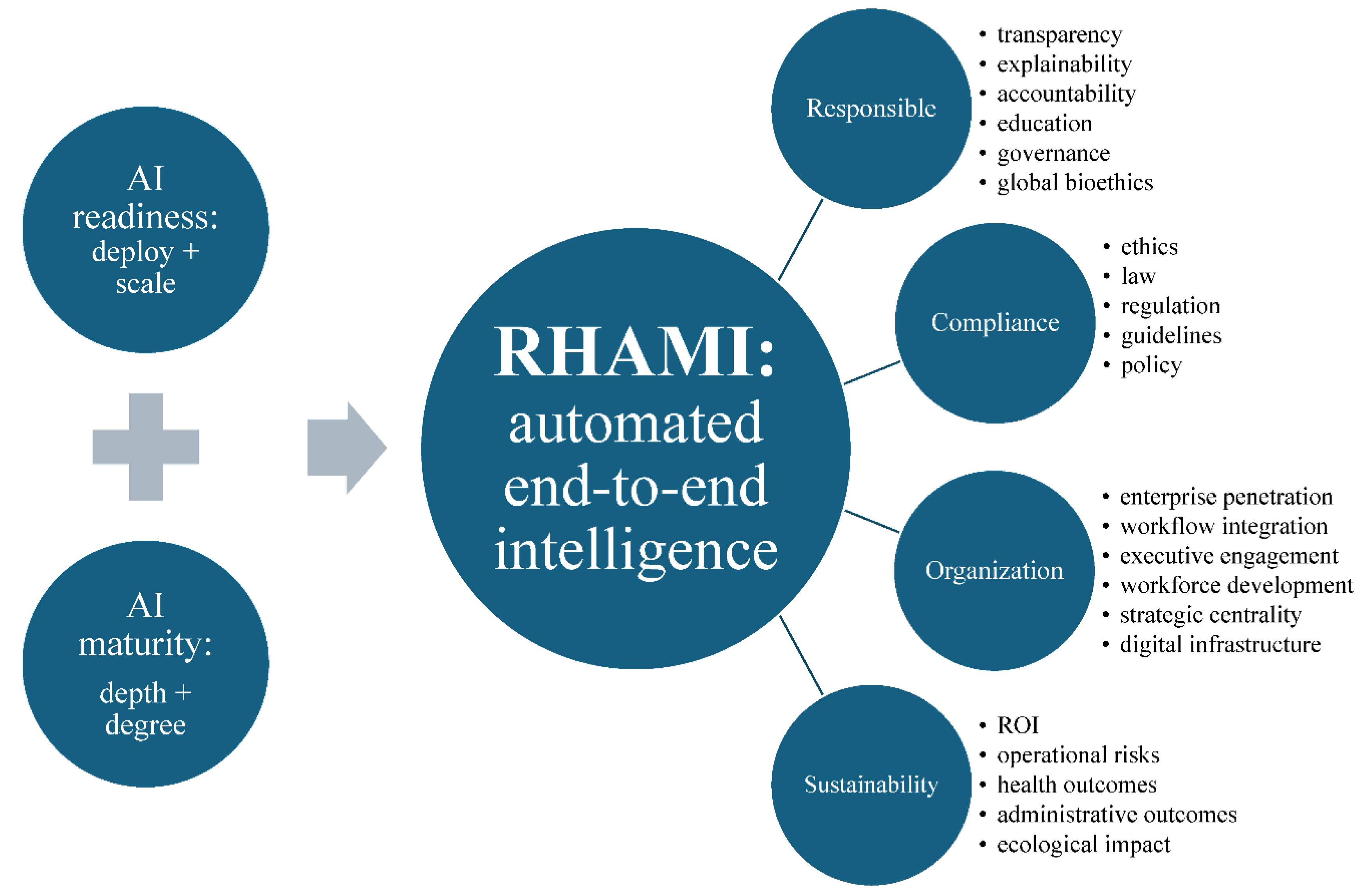

In its final optimized formula, RHAMI was engineered with 2 primary pillars: measuring the readiness of systems to deploy and scale AI, and then the maturity of its enterprise-wide depth and degree of advanced applications for this AI integrated with systems’ strategy, organizational structure, data infrastructure, culture, and governance (

Figure 1). It spans 4 key domains: responsible AI (with sub-components of transparency, explainability, accountability, education, governance, and global bioethics), compliance (with sub-components of ethics, law, regulation, guidelines, and policy), organization (with sub-components of enterprise penetration, workflow integration, executive engagement, workforce development, strategic centrality, and digital infrastructure), and sustainability (with sub-components of ROI, operational risks, health outcomes, administrative outcomes, and ecological impact). The index functioning as a quantitative assessment was normalized to a 100-point with 50 specific criteria total. Given the various and often ambiguous definitions of ‘responsible AI’, RHAMI featured the first end-to-end epistemic model in this topic that progressively builds from Personalist Quantum Metaphysics to Personalist Social Contract ethics to Personalist Liberalism (moral political economics) to Personalist AI Governance, providing a novel analytic incorporation into this empirical index of global political economic, multi-sector, and multicultural drivers of AI, nutrition, and health [

17]. It operationalizes

the WHO’s One Health human security-based approach by integrating the modern rights-based social contract ethics embodied in the only world-wide institutionalized moral consensus (codified by the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights from which the WHO’s Health Organization, international law, and all major AI governance frameworks derive), anchored in classical Aristotelian realist metaphysics (with Thomistic personalist refinement) to uniquely allow substantive and practical convergence of the world’s diverse belief systems underlying our political economics as the meta-determinants of health, ultimately by safeguarding individual dignity fulfilled in commitment to the common good of the global human family, which in turns safeguards the good of each individual. RHAMI accordingly maps how the form and function of the health ecosystem globally is a network of public-private partnerships driving AI infrastructure provisioned by user-facing platforms, expanding healthcare systems’ technical scale, clinical effectiveness, cost efficiency, and societal equity of their collective efforts generating AI-accelerated public health nutrition. Finally, the index was optimized according to the AI technique of reinforcement learning from human feedback, and then operationalized for healthcare systems scaled to global health according to the template by the Boston University’s WHO-backed pioneering BEACON platform as a free, real-time, open-source, decentralized global biothreats surveillance platform with expert human-in-the-loop quality control [

19].

AI unassisted literature review and AI assisted literature review were compared by root mean squared error (RMSE), as was RHAMI performance benchmarked off the performance of the above indexes given the absence of a widely recognized gold standard in or published demonstration of such an integrated index.

3.2. RHAMI Identification and Stratification of Leading Healthcare Systems and Their Nutrition AI

The highest readiness and maturity across the greatest concentration of healthcare systems for adopting responsible AI for nutrition were in the United States, followed by Europe and the Asian countries of Japan, South Korea, and India along with the United Arab Emirates (with which American healthcare systems and technology companies have historically dense institutional partnerships and supply chains across healthcare and technology). Within the health sector, most healthcare systems are at the earliest stages of AI maturity including being aware of or experimenting with AI but not yet operationalizing, scaling, nor transforming their systems with it. Within healthcare systems, Mayo Clinic as the world’s largest integrated non-profit medical group has the most mature enterprise-wide responsible health AI, after launching the first comprehensive AI-augmented Mayo Clinic Platform in support of its care network stretching across 60 healthcare organizations globally. But if the plan is realized, Cleveland Clinic—the world’s top ranked healthcare system behind Mayo Clinic—is best positioned to displace Mayo in the medium-term if Mayo were to lose its lead. Among AI platforms in parallel and partnering with healthcare systems, the top performing ones for nutrition included America’s SnapCalorie and MyFitnessPal, the United Kingdom’s Zoe, Canada’s Nutrigenomix, India’s HealthifyMe, and South Korea’s Samsung Food. Healthcare systems principally partnered with individuals and populations using such nutrition AI platforms to fill technical capability gaps in their nutrition assessments and healthy eating support. But there were no healthcare systems with mature enterprise-wide nutrition AI, either in standardized and scaled best-practices in nutrition assessments nor in healthy eating education and support. Overall, the primary application areas for leading systems’ public health nutrition AI included: edge AI nutrition assessments, scaled precision nutrition, and sustainable healthy diets detailed below.

3.3. Multimodal Edge AI Nutrition Assessments as Ambient Intelligence

Nutritional assessments are the historical cornerstone for informing individual behaviors and population policies facilitating healthier eating, by first detailing the amount, types, and timing of food intake (typically in the context of individuals’ height, weight, body-mass-index, medical conditions, physical exam, and laboratory tests to identify nutrition imbalances, excesses, and deficits) [

20]

. Yet they are notoriously difficult to accurately, quickly, consistently, and affordably conduct at population scale. If you do not know where the nutrition problems are, then you do not know how to personalize the individual interventions and population policies to address them. Healthcare systems worldwide especially in LMICs lack the necessary number of dieticians skilled in these assessments, and healthcare providers generally lack sufficient and standardized education and practice with them. That is where AI is rapidly gaining momentum. Early use cases focused on labor and cost-intensive hand-built machine learning algorithms to replicate the traditional step-wise nutrition assessment [

21]

. By the late 2010s, deep learning algorithms became more widespread as more complex models automatically learned more relevant features faster and directly from raw data with less human programming, mostly achieving adequate performance in energy estimation and macronutrient tracking but lagging in micronutrients. The more advanced recent deep learning deploys computer vision such as on the digital applications or apps of smartphones, functioning as edge digital devices linked to their cameras to provide users real-time assessments [

22]

. Wearable smart watches, glasses, and e-buttons provide even more complex ambient monitoring through motion sensing. The current leading use cases are coalescing around such edge AI nutrition assessment as ambient intelligence. This trend brings together edge computing (more private, secure, and energy efficient local data processing and AI applications such as smartphone apps to reduce latency, bandwidth use, and cloud reliance at the edge of the global digital ecosystem), AI-enabled nutrition assessments (computer vision, audio detection, motion sensors, voice logging, smart food appliances, and wearable sensors to identify, quantify, and categorize foods consumed and their related nutrients and eating behaviors in progressively more automated and augmented fashion), and ambient intelligence (running such AI in the background without regular human commands). A 2024 Nature publication of EgoDiet (based on a mask region-based convolutional neural network) demonstrated that passive monitoring with low-cost AI-enabled wearable cameras were superior to traditional self-reported and dietician-conducted nutrition assessments for healthy portion sizes of local African cuisines in rural Ghana [

23]

. This culturally-sensitive ambient intelligence enables more precise and personalized nutrition assessments and thus recommendations for healthy eating based on tracked individual food preferences, portion sizes, and meal timing. A 2025 American feasibility clustered randomized controlled trial demonstrated that primary care physicians utilized a multi-lingual AI expert clinical decision support (CDS) for nutrition assessment on 100% of outpatient encounters in lower resourced safety net clinics, up from the historic threshold of 30-40% for expert CDSs required to be considered successful enough to scale for widespread clinical use [

24]

. This system, Nutri, was co-designed with clinicians, patients, and AI engineers to provide automated multi-level behavioral nutrition assessments and recommendations that can reliably be incorporated into brief but effective counseling segments of less than 3 minutes within a typical provider-patient visit. Nutri rapidly assesses and personalizes recommendations from the latest guidelines and research that clinicians can then modify and apply for achievable diet modifications, while complementing rather than disrupting the other core aspects of clinical visits. A 2025 Chinese study showed how a LMIC hospital successfully deployed an extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) AI algorithm using the GLIM (Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition) framework running in the background on EHR records for successful malnutrition screening, with the top 6 predictors identified being decreased food intake, weight loss, BMI, white cell count, neutrophil percentage, and pre-albumin [

25]

. A 2024 Chinese randomized controlled trial across 11 hospitals and 5,763 patients showed that an AI-based rapid nutritional diagnostic system embedded within routine clinical care significantly improved malnutrition diagnosis and reversal, at an AI intervention cost that is 73% cheaper than China’s per capita cost of malnutrition’s health effects.

These studies provide notable evidence of practical sustainability, workflow embeddedness, clinical effectiveness, and cost efficiency respectively. Yet none of these use cases, nor any AI-enabled nutrition assessments are in standard or sustainable enterprise-wide deployment within healthcare systems as part of comprehensive nutrition care. And none outside of Nutri provide substantive detail behind their governance safeguards to assess let alone ensure responsible AI deployment. In RHAMI analysis, a feasible and affordable integrated nutrition assessment would marry such use cases as the American Nutri-like outpatient expert system with the Chinese inpatient malnutrition screen, paired with a smartphone or smartglass version of the African EgoDiet for longitudinal and personalized ambient nutrition assessments (with embedded compliance-by-design governance as with Nutri based on the American HIPAA, or Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the world’s leading regulatory framework for protecting individual health data along with the mostly comparable European GDPR, or the General Data Protection Regulation). But most healthcare systems in the Global South significantly lag behind their northern counterparts in EHR adoption and functionality. Less than 25% of African LMIC healthcare systems have EHRs [

26]

, but already over 65% of Africans have internet-capable smartphones and are on course to reach over 90% by 2030 [

27]

. AI platforms may thus extend the limited reach of healthcare systems as with EgoDiet, or similar tools like MyFitnessPal [

28]

. It serves as the top nutrition app on the digital edge with over 250 million users in 120 countries, generating personalized nutrition plans from over 5 million foods based on this free tracker (for calories, macronutrients, micronutrients enabled with computer vision, along with the fee-based subscription including barcode scanning and voice logging also).

3.4. Strategic Scaling of Practical Embedded Precision Nutrition Platforms

The results of AI-accelerated nutrition assessments are meant to then inform actionable recommendations, with the more personalized being the more likely to ultimately succeed in improving health. At the most advanced end of that spectrum, precision nutrition arose out of translational multi-omics in precision medicine and precision public health to individualize dietary recommendations, including according to health status, lifestyle, microbiome, and genetics [

29]

. This trend is fueled by the historic successes in particular of precision medicine for cancer care to translate granular knowledge of individuals’ genes, lifestyles, and environments into targeted treatments with maximum clinical benefit, minimum risk, and optimized overall affordability (uniting genomics, epigenomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other -omics biological fields to facilitate healthier states faster, thus reducing often unaffordable longitudinal clinical and financial costs of disease). But despite promising individual results, precision nutrition has been slow to scale even in HICs amid the substantive up-front investment, funding, infrastructure, and training required, thus limiting its population impact especially among LMICs. There a number of recent academic studies advancing isolated but effective use cases of AI-enabled precision nutrition to accelerate its scaling throughout healthcare systems. A 2024 Greek study in Nature not only demonstrated a novel LLM with deep generative AI could accurately produce guideline-based personalized dietary recommendations over 84% of the time (among 1,000 real profiles and 7,000 daily meal plans). But it also showed it could be paired with the more globally accessible ChatGPT at over 700 million weekly active users to improve the accuracy and meal variety across more local cuisines worldwide [

31]

. The novel model accounted for individuals’ medical conditions, anthropometric measurements, and caloric needs with consensus recommendations as by the WHO. An American team in 2023 had already shown that ChatGPT already been shown to effectively generate meal plans customized for pregnant mothers from underserved populations [

32]

. Considered together, the Greek study may support how AI-enabled personalized nutrition through free open-source leading frontier AI platforms can produce comparable results to custom-built proprietary models for particular benefit to LMIC healthcare systems, while also suggesting the feasibility for multi-omics data to be added as another data input as the above health data to move from personalized to precision nutrition at scale. A 2025 Stanford University in Nature provided a more mature AI-augmented precision nutrition intervention integrated within its healthcare system for newborn children admitted to neonatal intensive care units requiring total peripheral nutrition (TPN) [

33]

. TPN can be life-saving interventions infused through the blood vessels to provide hospitalized patients nutrition when they cannot receive it through their digestive tract. Yet ordering it requires specialized knowledge with dieticians, pharmacists, and physicians collaborating on building these complex prescriptions, thus prone to error and complications. The team built TPN2.0 as a deep learning approach using a variational neural network with semi-supervised iterative clustering on an EHR dataset of routinely collected variables (including diagnoses, demographics, and TPN details across 79,790 TPN orders from 5,913 patients, followed by model validation with a second hospital’s dataset). TPN2.0 identified 15 customized TPN formulas according to the unique needs of newborns grouped precisely into similar clusters. A blinded analysis within the trial showed that physicians were over 3 times as likely to rate TPN2.0 orders as superior to non-AI TPN orders crafted by traditional best practices. It also showed the AI orders had notably less risk of complications (including sepsis and death). The authors explicitly investigated the potential of scaling TPN2.0 globally to LMICs, as the clinical adoption of AI in neonatology is non-existent and customized TPN is generally inaccessible at population scale for LMICs. By balancing clustered treatment standardization with clinically relevant personalization, the Stanford model “can enable a precision-medicine approach” for nutrition that is safer to deploy, easier to order, and cheaper to generate (through mass manufacturing of the TPN formulas and embedded use of TPN2.0 within healthcare systems’ existing EHRs).

A 2025 Nature review by an American-Bangladesh team detailed the latest applications of precision nutrition in low resource settings with particular focus on such maternal and child health, citing the above Stanford study [

34]

. Healthcare systems especially in LMICs generally focus on public health nutrition by identifying malnutrition, supplementing micronutrients, and fortifying foods to prevent and reverse the undernutrition common in Stanford’s critically sick newborns and even more so in low-resource communities worldwide. Such AI uses of public health precision nutrition enable more impactful resource prioritization not only in intensive care units, but more generally across populations by focusing on diseases that can benefit from more targeted and affordable nutrition interventions. The American-Bangladesh team additionally highlighted how AI-enabled microbiota-directed complementary foods produced twice the mean rate of growth compared to traditional ready-to-use therapeutic foods for severe acute malnutrition (though the study lacked demonstration of longitudinal follow-up after 3 months, cost efficiency, and healthcare system scale-up). But the LMIC analysis also pointed to the gradual introduction into precision nutrition of AI-powered personalized digital twins to virtually simulate various customized nutrition interventions for patients according to their specific health status, microbiome, biochemistry, social settings, and environment. This approach can ultimately empower healthcare systems working in parallel (and preferably in coordination of limited health and digital resources) to better improve public health nutrition through precision nutrition scaled up to the population level. Doing so across HIC is a struggle, and among LMICs is nearly absent. But translational research for more equitable precision nutrition is expanding. The American National Institutes of Health (NIH) has unveiled within its All of Us program the largest AI-augmented precision nutrition research project across 14 healthcare systems and universities with 10,000 individuals, particularly drawn from historically underrepresented and underserved groups [

35]

. Over 53 million Americans are immigrants, as the United States has nearly 20% of all the world’s migrants (and history’s highest and longest immigration flow). The NIH’s overarching All of Us was therefore launched early in 2018 and has since built the largest and most diverse health dataset and precision health study ever, monitoring multi-omics data longitudinally on over 1 million people (with 80% identifying with a racial and ethnic minorities who historically have been underrepresented in health research, and thus derivative drugs and procedures). The USA government behind the NIH provides nearly half of all global health funding (nearly 4 times more than the next donor country being the United Kingdom) [

36,

37]

. Most of that $12.4 billion annually is concentrated in Global South, with 84% going to Africa alone, though only 1% or $168 million goes to nutrition (among the smallest funding priorities). But nearly 4 times the global health budget, America pours nearly $50 billion annually into biomedical research as the world’s largest funder of it—8 times the collective amount of the next 5 donors being British, Canadian, Australian, and European institutions and governments [

38]

. But worsening debt crises, distress, and pressure worldwide mean more efficient prioritization on more impactful translational research is required, especially in nutrition which hold the greatest return-on-investment for public health. In RHAMI analysis, such institutional funding structures are central nodes in the public-private networks constituting the health ecosystem, having disproportionate influence setting the research agenda, funding priorities, and practical health applications. The AI-enabled precision nutrition within All of Us therefore potentially represents a potent template and impetus for expanding the inclusivity, relevance, and impact globally especially in LMICs for such applications (with an emphasis on those that can scale throughout healthcare systems even after study periods and their funding cycles conclude). But for now, RHAMI analysis also highlights there are still no mature or even system-wide AI-enabled precision nutrition capabilities in HICs, and no clear enduring use cases in LMICs. The study at Stanford (which also houses the Stanford Institute of Human-Centered AI as a world leader in responsible AI governance) is limited to the United States with their financially and resource-intensive neonatal intensive care units. But it does represent the most clinically integrated, financially sustainable, and advanced governance demonstration of precision nutrition. It also suggests an underexplored trajectory gaining momentum—strategically sustainable scaling of patient-first rather than AI-first practical precision nutrition. The goal of AI-enabled precision nutrition is not AI for AI’s sake, or precision nutrition for its own sake, but the ultimate public health achieved by effective coordination and alignment of healthcare systems, empowered by AI improving the care they provide more widely, affordably, and sustainably. TPN2.0 tries to find and fix a current deficit in services by healthcare systems such as safe, affordable, and scalable TPN. It reverses those deficiencies with AI-enabled solutions embedded in clinical workflows that become routine even after their study periods. RHAMI may uniquely be used to help healthcare systems rapidly identify such promising scalable solutions that address the gaps and priorities most of interest to local systems (and most aligned with their strategy and local values), rather than trying the mostly slower and costlier approach of uncritically experimenting with various AI precision nutrition applications.

3.5. Sovereign Swarm Agentic AI Social Networks for Sustainable Healthy Diets

AI-accelerated nutrition assessments tell you what to fix, precision nutrition shows you how, but agentic AI may help you actually do it in healthy diets [

39]

. AI chatbots like ChatGPT can answer your questions, while AI agents can solve them, autonomously performing multi-step reasoning, making goal-directed planning, adapting to changing conditions, and iteratively improving results with minimal human direction. Yet they are much more expensive to build and maintain, amid escalating geopolitical tensions and strained supply chains dividing and even balkanizing the global AI ecosystem (working to advance large scale agentic AI through the prerequisite innovations technically and financially). So, there is a concurrent rise in platforms for sovereign agentic AI-as-a-service with the American company, NVIDIA, being far and away the leading provider of such enterprise AI factories or full stack AI (the layered end-to-end architecture of chips, data centers, algorithms, workers, and governance as a resilient, self-reliant, and self-contained AI ecosystem). NVIDIA continues to power our AI era by providing countries and companies worldwide including in LMICs such as India and in the Middle East this full stack AI locally, especially for healthcare systems facing more stringent regulations than in other economic sectors. Instead in sovereign AI, the data, models, and compute are done locally and thus more securely and affordably (than users having to build out themselves those stacks as history’s most labor, capital, and expertise-intensive infrastructures ever)—including at the edge of the global digital ecosystem, rather than ferrying those assets across state borders to other countries’ cloud centers. Look at big hospitals and you will often see power plants not far away, as the electric grid feeding them is part of the critical infrastructure enabling healthcare systems to operate (i.e., operating rooms cannot lose the lights in the middle of surgeries). It appears increasingly not far from now that hospitals will have to have neighboring AI factories as their critical digital infrastructure so they can process, analyze, and leverage their massive data sets and streams to provide care including in nutrition. The decentralized counterpart to such sovereign AI may be swarm intelligence which is rising in healthcare and is poised to break into nutrition in the near-term [

40]

. Inspired by self-organized systems like ant colonies naturally, swarm agentic AI can collectively execute complex tasks, often secured through blockchain to keep data locally secure while sharing insights across the network. Stanford took this a step further partnering with the private American software company, Microsoft, to create healthcare’s first multi-AI agent orchestrator at multi-center deployment in real-world clinical care [

41]

. With embedded HIPAA-compliant responsible governance, this AI for AIs compress hours of complicated work per patient into minutes to integrate multimodal health and biologic data into actionable diagnosis and treatment recommendations as a digital tumor board. A traditional tumor board is a very time and resource costly collaboration of multiple medical specialists to design a complex care plan—which is usually only done for a small segment of patients with complicated or rare cancers served by large healthcare systems, and mostly in HICs. Microsoft’s orchestrator in contrast coordinates diverse AI agents (each for the patient’s history, imaging, pathology, cancer staging, relevant clinical guidelines and clinical trial opportunities, latest research, and report creation, securely connecting the ambient EHR intelligence with real-time data from the global digital ecosystem for precision medicine). While nutrition appears to be moving there, it is just beginning with agents, including AI nutritionists and health coaches. A 2025 Dutch team demonstrated a globally scalable approach applicable for low-resource communities and LMICs with Meta’s freely available LLaMA3 to provide personalized, sustainable, evidence-based healthy meal plans [

42]

. By integrating authoritative dietary guidelines and the United Nation Sustainable Development Goals, the edge “virtual nutritionist” can make real-time recommendations on customized meals worldwide for users regardless of their health literacy using this local AI and locally sourced ingredients (keeping user data private and secure). Meanwhile, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is funding Dimagi South Africa to create an AI coach for Malawi to empower LMIC frontline healthcare workers with LLM-generated personalized coaching—spanning early childhood development, skin-to-skin contact, financial management, and self-care—to holistically boost healthy eating for mothers and newborns [

43]

.

Such interventions understand that improving healthy behaviors is best done in community, where individual changes are reinforced by others in one’s own social network (with the inverse being true also). The landmark network study from the New England Journal of Medicine had shown through the Framingham Heart Study cohort across over 30 years and 12,067 people that obesity spreads up to 3 degrees of separation—independent of biology and geography—to the point that individuals’ chance of becoming obese increased by nearly 60% if their friends did first [

44]

. Leveraging such network dynamics for healthy eating, one of this review’s authors (D.J.M.) co-founded culinary medicine in the world’s first medical school-based teaching kitchen for underserved communities as an end-to-end, cost-efficient, and culturally-sensitive public health nutrition intervention (augmented by novel AI agents for real-time continuous analysis and health improvement) [

45]

. The Bayesian adaptive randomized controlled trial within the largest longitudinal nutrition education study he created demonstrated that families in low-resource communities could lower their weekly food bills while tripling their odds of achieving healthy eating habits compared to the standard-of-care, while the medical students and physicians teaching those cooking classes had at least 5-fold increased odds of healthy eating habits themselves after going through the course (which has since been implemented at over 55 healthcare systems, medical schools, and universities across the United States). The leading AI platforms also understand the compounding effect of community. Meta’s edge AI-enabled smartglasses enable hands-free cooking with personalized meal plans, networked into its sister platform, Facebook, as the world’s largest social media network used by nearly half of the world’s population stretching across the Global South as well [

46]

. Its mature enterprise-wide AI already leverages AI agents for automated productivity, reinvesting its historic profits into historic capital expenditures explicitly seeking to be the first platform to turn its agents into AGI (artificial general intelligence capable of doing all human cognitive tasks as good as humans) and ultimately ‘personal’ superintelligence (doing so better than humans) to electrify the world’s largest digitally connected social network. Think of it as the smartest AI orchestrator of a swarm of edge AI on each digital device, streamlined in your day, supposedly empowering your healthy diets and lifestyles that are reinforced by like-minded friends and family in your community, and networked into families and communities worldwide collectively learning at unprecedented speed)—amid significant critics that AGI governance is even possible, or superintelligence can be controlled, let alone fairly benefit populations outside the small number of massive technology companies rushing to build it, along with humanity’s future that supposedly will run on it.

In RHAMI analysis, Stanford’s Microsoft AI orchestrator provides a potential responsible AI-driven cost-saving democratization of one of the healthcare’s most time and resource-intensive services—tumor board’s complex multi-specialty cancer care—in a way that can democratize and scale such services to lower resource communities and LMICs, along with the less complex but more societally impactful services as boosting population-level healthy eating. Microsoft’s Responsible AI compliance-by-design embedded in this technology already has global scale by the company’s status as the world’s largest software provider including in healthcare systems. Along with AI nutritionists and coaches especially promising for the Global South, there is a clear pathway for private AI platforms provisioning best-in-class sovereign swarm agentic AI amplified by social networks to collectively and thus sustainably advance healthy diets at population and global scale. Yet the much higher profit margin for their use in specialized healthcare services like complex oncology means strategic, deliberate, and collaborative focus is required by executives and front-line healthcare workers to selectively bring these technologies to bear to realize enterprise-wide AI throughout systems. No healthcare systems in HICs or LMICs feature even sustained organization-wide programs boosting healthy eating within essential public health nutrition as part of routine healthcare. So the most likely path to reverse this is for the continued rise of increasingly capable and versatile agentic AI, paired with smart edge devices like users’ smartphones whose adoption rate is growing fastest in LMICs as rapid and decentralized swarm learning in ways that are useful, relevant, impactful, and still secure for users (with healthcare systems progressively integrating these largely private platform services into their existing clinical workflows as sovereign ambient intelligence).

4. Discussion

This narrative review attempts to provide a concise but novel, actionable, and global outline for the emergent roadmap helping move nutrition research and practice from what may work to what stably scales in AI-accelerated public health nutrition driven by healthcare systems. Persistently urgent and unmet population health needs especially in LMICs demonstrate it is not enough for AI research on nutrition to be about what are interesting use cases. Executives and clinicians need rigorous full-spectrum analysis of how to scale the best ones throughout their local healthcare systems. To move from nutrition research experimenting with AI to actually transforming nutrition with AI through more mature translational research, this paper details and applies the novel AI meta-index of RHAMI to generate a uniquely comprehensive and actionable healthcare tool to standardize the qualifying process in responsible enterprise-wide AI capabilities and functionalities for continuous optimization of strategic planning and daily operations. Like building useful health AI, strategically implementing, growing, and maturing it within healthcare systems—where most health services, research activities, and societal funding occurs—is an increasingly complex, costly, and confusing process for most systems. With shrinking financial and human capital resources, there is already a global and quickly growing practical need to rapidly identity, implement, integrate, innovate, and institutionalize AI-accelerated public health nutrition within healthcare systems that saves more lives (than the other interventions for which resources could be prioritized), saves more money (than it spends for patients, systems, and populations), and saves more of our common home (than the ecological resources required for less sustainable interventions). RHAMI provides a potentially high-impact, practical, and scalable democratization especially for lower-resource communities globally to automatically synthesize the major domains of data inputs required for effective, efficient, and equitable solution outputs to build human-centered AI-accelerated healthcare systems, beginning with the public health nutrition essential for humanity’s health. Built collaboratively (by front-line clinicians, public health practitioners, nutritionists, engineers, executives, and policymakers with decades of experience in direct service and system strategy), it is engineered to be used cooperatively in the increasingly globalized health ecosystem.

There are a number of recent robust narrative reviews of AI’s role in nutrition assessments and healthy eating [

34,

47,

48,

49]

. But their utility is limited for healthcare workers, leaders, and policymakers practically advancing the field for healthcare, public health, and global health. This gap between analysis and application arises from their descriptions of largely isolated nutrition AI use cases for nutrition detached from an empirical analysis within healthcare systems of (a) their readiness to integrate affordable nutrition AI into existing workflows and organizational structures, (b) their maturity building sufficiently sophisticated and scaled nutrition AI throughout their enterprises, and (c) their governance of nutrition AI to ensure its ethical, regulatory, legal, and professional compliance for sustainable net benefit for the organizations and the health communities they serve. They also lack the specific focus on underserved communities and LMICs who stand to most benefit from such nutrition AI, and who face the greatest disparities receiving them. Additionally, the AI indexes cited in the methods attempting to make AI useful not just useable for such urgent health challenges are influential, but also limited in their practical benefit for healthcare systems. They focus on AI readiness, maturity, or responsibility (but fail to meaningfully unite them for end-to-end decision-making). And they provide high-level guidance, but not operationally significant insights in system administration or clinical care to actualize it. Instead, this paper uniquely provides the first multi-dimensional, multi-disciplinary, and multi-sector narrative review through a novel end-to-end automated health AI index for AI-enabled nutrition assessment and healthy eating by an international team of front-line clinicians, ethicists, engineers, and leaders. Such an integration is necessary (and increasingly inevitable given worsening resource constraints on the current trajectory pressuring more seamless analysis and leadership). Even in the United States with the most mature national AI ecosystem and richest national health sector, only 18% of healthcare systems have mature AI, less than half report sufficient resources just to begin implementation of AI, most are making or moving toward AI investments principally to reduce costs, and over 80% report insufficient capabilities to identify and integrate AI within their system [

50]

. Nearly 80% report that they depend on their current vendors (or their AI partners) to implement AI given their lack of endogenous capabilities to do so. Without an end-to-end empirically verifiable approach embodied by RHAMI, there is no clear pathway to scaling responsible and mature AI for nutrition let alone health globally where it is most needed.

Compared to prior studies in this field, RHAMI’s results on national AI ecosystems and AI-enabled healthcare systems are collectively comparable to other indexes and analyses focused on more isolated aspects of their AI [

12,

51,

52]

. But it goes further to provide this end-to-end approach for responsible AI readiness and maturity evaluation including at the global level applied to nutrition AI (with more granular and real-time insights for local healthcare systems’ clinicians and executives according to their particular needs). The analysis does support how Mayo Clinic appears to likely remain the frontrunner in mature health AI including on nutrition, while Cleveland Clinic is most likely to leap frog it if the latter can deliver on its strategic partnership announced in May 2025 with the Emirati’s G42 and Oracle Health for the first nation-scale and most advanced AI-accelerated healthcare platform [

53]

. This trajectory analysis technically derives from Oracle’s capabilities as the world’s largest database management system (operating the first cloud-native EHR with embedded voice-first agentic AI, second only to Epic in global market share of EHRs), along with G42’s status as a leading sovereign AI infrastructure company within the Global South (also operating 480 clinics in 26 countries, and the world’s largest genomics program for nation-scale implementation of precision medicine) [

54]

.

There are several key limitations to this narrative review. Given the broad scope of the topic and limited space of the paper, some degree of depth had to be sacrificed to allow sufficient scope of the methodology and results on the leading nutrition AI use cases manifesting the larger structural trends (yet to improve such analyses, and the AI index methodology doing so, much greater detail is required to allow sufficient peer and public scrutiny of the index to improve it, which is contained in the next paper). More granular country and system-specific analyses are also required, which the next phase of this study pipeline is underway with an open-source API to address. Also, this analysis lacked a more detailed analysis of China for instance which has a booming national AI ecosystem second only to America, but limited investments and expenditures in its national health system (half the global per capita average as a percentage of their GDP), and even lower scaling of responsible AI governance throughout it—though China still has significant innovations as noted above, along with a world leading position in AI infrastructure [

55,

56]

. Notwithstanding such limitations, this narrative review still concisely provides a unique full-spectrum overview of the state-of-the-art scaling AI-accelerated innovations by healthcare systems for nutrition assessment and healthy eating (with particular focus on low-resource communities and LMICs) using a novel end-to-end AI index to automate future optimization by front-line clinicians, leaders, and policymakers. The smarter our AI methods and interventions become in health nutrition, the more it appears to be facilitating us getting back together at the dinner table to recover what health and community mean, together.

Author Contributions

D.J.M.: design, analysis, drafting, revision, and submission; L.O., P.O., D.K., J.R., C.S., O.S., T.A., S.B.D., K.M., D.G., D.J., T.S., A.G., C.G., C.I., N.A.: analysis, revision, and submission; S.M.: design, revision, and submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was used in this study. D.J.M. provided all analyses pro bono.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

None for all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

None for all authors.

References

- GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators , 2019. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393 (10184): 1958–1972.

- FAO, 2024. The state of food and agricultures. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-state-of-food-and-agriculture/en (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- Ganatra, S., Khadke, S., Kumar, A., Khan, S., Javed, Z., 2024. Standardizing social determinants of health data: A proposal for a comprehensive screening tool to address health equity a systematic review. Health Affairs Scholar 2 (12): qxae151.

- Krishnan, S., Sytsma, T., Wischmeyer, P.E., 2024. Addressing the urgent need for clinical nutrition education in postgraduate medical training: New programs and credentialing. Advances in Nutrition 15 (11): 100321.

- Xu, K., Garcia, M.A., Dupuy, J., Eigo, N., Li, D., 2024. Global spending on health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086746 (accessed: 18 July 2025).

- Wager, E., Rakshit, S., Cox, C., 2024. What drives health spending in the U.S. compared to other countries? Peterson Center on Healthcare. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/what-drives-health-spending-in-the-u-s-compared-to-other-countries/#Growth%20in%20health%20spending%20per%20capita%20by%20category,%20United%20States%20and%20comparable%20countries,%202013%20-%202021 (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- WHO, 2023. Noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- WHO, 2025. Health workforce. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1 (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- UN, 2023. Africa spends more on debt servicing than health care. United Nations. https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm21809.doc.htm (accessed: 3 January 2025).

- Monlezun, D.J., 2024. Artificial intelligence re-engineering the global public health ecosystem: A humanity worth saving. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Publishing Academic Press.

- Hussain, S.A., Bresnahan, M., Zhuang, J., 2025. Can artificial intelligence revolutionize healthcare in the Global South? A scoping review of opportunities and challenges. Digital Health 11: 20552076251348024.

- HAI, 2025. The 2025 AI Index Report. Stanford University Institute of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- Monlezun, D.J., Omutoko, L., Oduor, P., Kokonya, D., Rayel, J., Sotomayor, C. et al., 2025. Digitalization of health care in low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 103 (2): 148–154.

- Durlach, P., Fournier, R., Gottlich, J., Markwell, T., McManus, J., Merill, A., et al. The AI Maturity Roadmap: A framework for effective and sustainable ai in health care. New England Journal of Medicine (accessed: 3 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gupte, N., 2024. Responsible AI Readiness Index: A tool to track the progress and impact of responsible AI. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Seminars/Conferences/2024/11/20/12th-statistical-forum (accessed: 2 July 2025).

- IMD, 2025. AI Maturity Index. International Institute for Management Development. https://www.imd.org/artificial-intelligence-maturity-index/ (accessed: 3 July 2025).

- Monlezun, D.J., 2025. Quantum health AI: The revolution of medicine, public health, and global health by quantum computing-powered artificial intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

- GCAG, 2025. Global Index on Responsible AI. Global Center on AI Governance. https://www.global-index.ai/ (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- BEACON, 2025. Biothreats Emergence, Analysis and Communications Network (BEACON). Boston University. https://beaconbio.org/en/ (accessed: 19 September 2025).

- El-Kour, T.Y., Kelley, K., Bruening, M., Robson, S., Vogelzang, J. et al., 2021. Dietetic workforce capacity assessment for public health nutrition and community nutrition. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 121 (7): 1379–1391.

- Chotwanvirat, P., Prachansuwan, A., Sridonpai, P., Kriengsinyos, W., 2024. Advancements in using AI for dietary assessment based on food images. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26: e51432.

- Phalle, A., Gokhale, D., 2025. Navigating next-gen nutrition care using artificial intelligence-assisted dietary assessment tools-a scoping review of potential applications. Frontiers in Nutrition 12: 1518466.

- Lo, F.P., Qiu, J., Jobarteh, M.L., Sun, Y., Wang, Z., 2024. AI-enabled wearable cameras for assisting dietary assessment in African populations. Nature Digital Medicine 7 (1): 356.

- Burgermaster, M., Rosenthal, M., Altillo, B. S., Flores, M. R., Nayak, E., 2025. Pilot trial of Nutri, a digital intervention for personalized dietary management of diabetes in safety-net primary care. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 57 (7): 614–626.

- Wang, X., Yao, K., Huang, Z., Zhao, W., Fu, J., 2025. An artificial intelligence malnutrition screening tool based on electronic medical records. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 68: 153–159.

- Mugauri, H.D., Chimsimbe, M., Shambira, G., Shamhu, S., Nyamasve, J., 2025. A decade of designing and implementing electronic health records in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Health Action 18 (1): 2492913.

- GSMA, 2023. The mobile economy sub-Sararan Africa. Global System for Mobile Communications Association. https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-economy/sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed: 21 September 2025).

- MyFitnessPal. MyFitnessPal announces acquisition of intent, revolutionizing personalized meal planning for members. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/americans-still-in-the-dark-new-data-from-myfitnesspal-reveals-sizable-continuing-gaps-in-basic-nutritional-knowledge-302083009.html#:~:text=About%20MyFitnessPal,tools%20for%20positive%20healthy%20change.&text=Research%20was%20fielded%20by%20MyFitnessPal,64%20across%20the%20United%20States. (accessed: 21 September 2025).

- Guasch-Ferré, M., Wittenbecher, C., Palmnäs, M., Ben-Yacov, O., Blaak, E. E. et al., 2025. Precision nutrition for cardiometabolic diseases. Nature Medicine 31 (5): 1444–1453.

- Bedsaul-Fryer, J.R., van Zutphen-Küffer, K.G., Monroy-Gomez, J., Clayton, D. E., Gavin-Smith, B. et al., 2023. Precision nutrition opportunities to help mitigate nutrition and health challenges in low- and middle-income countries. Nutrients 15 (14): 3247.

- Papastratis, I., Konstantinidis, D., Daras, P., Dimitropoulos, K., 202. AI nutrition recommendation using a deep generative model and ChatGPT. Nture Scientific Reports 14 (1): 14620.

- Tsai, C.H., Kadire, S., Sreeramdas, T., VanOrmer, M., Thoene, M. et al., 2023. Generating personalized pregnancy nutrition recommendations with GPT-powered AI chatbot. 20th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management 2023 (2023): 263.

- Phongpreecha, T., Ghanem, M., Reiss, J.D., Oskotsky, T.T., Mataraso, S.J. et al., 2025. AI-guided precision parenteral nutrition for neonatal intensive care units. Nature Medicine 31 (6): 1882–1894.

- Mehta, S., Huey, S.L., Fahim, S.M., Sinha, S., Rajagopalan, K., 2025. Advances in artificial intelligence and precision nutrition approaches to improve maternal and child health in low resource settings. Nature Communications 16 (7673). [CrossRef]

- NIH, 2025. Nutrition for precision health, powered by the All of Us research program. United States National Institutes of Health. https://commonfund.nih.gov/nutritionforprecisionhealth/news/NPHRecruitment (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- KFF, 2025. Breaking down the U.S. global health budget by program area. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/breaking-down-the-u-s-global-health-budget-by-program-area/ (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Oum, S., Wexler, A., Kates, J., 2025. 10 things to know about U.S. funding for global health. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/10-things-to-know-about-u-s-funding-for-global-health/ (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Gaind, N., 2025. How the NIH dominates the world’s health research. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00754-4 (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Briski, K., 2025. Sovereign AI agents think local, act global with NVIDIA AI factories. NVIDIA. https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/sovereign-ai-agents-factories/ (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Kollinal, R., Joseph, J., Kuriakose, S.M., Govind, S., 2024. Mapping research trends and collaborative networks in swarm intelligence for healthcare through visualization. Cureus 16 (8): e67546.

- Lungren, M., 2025. Developing next-generation cancer care management with multi-agent orchestration. Microsoft. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/industry/blog/healthcare/2025/05/19/developing-next-generation-cancer-care-management-with-multi-agent-orchestration/ (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Gavai, A. K., van Hillegersberg, J., 2025. AI-driven personalized nutrition: RAG-based digital health solution for obesity and type 2 diabetes. PLOS Digital Health 4 (5): e0000758.

- Gates, 2023. Closing the supervision gap: a large language model (llm)-powered coach for frontline workers. Gates Foundation Global Grand Challenges. https://gcgh.grandchallenges.org/grant/closing-supervision-gap-large-language-model-llm-powered-coach-frontline-workers (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Christakis, N.A., Fowler, J.H., 2007. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. The New England Journal of Medicine 357 (4): 370–379.

- Monlezun, D.J., Carr, C., Niu, T., Nordio, F., DeValle, N., Sarris, L., et al. 2022. Meta-analysis and machine learning-augmented mixed effects cohort analysis of improved diets among 5847 medical trainees, providers and patients. Public Health Nutrition 25 (2): 281–289.

- Meta, 2025. Hands-free cooking with AI glasses. https://www.meta.com/ai-glasses/cooking/?srsltid=AfmBOopjSRoRr9wlScJS4c5wb_h10XY9g9PkvMyqcydTMuQc-vStw4IB (accessed: 22 September 2025).

- Kassem, H., Beevi, A.A., Basheer, S., Lutfi, G., Cheikh Ismail, L. et al., 2025. Investigation and assessment of ai’s role in nutrition: An updated narrative review of the evidence. Nutrients 17 (1): 190.

- Monlezun, D. J., MacKay, K., 2024. Artificial Intelligence and Health inequities in dietary interventions on atherosclerosis: A narrative review. Nutrients 16 (16): 2601.

- Miyazawa, T., Hiratsuka, Y., Toda, M., Hatakeyama, N., Ozawa, H., Abe, C. et al., 2022. Artificial intelligence in food science and nutrition: A narrative review. Nutrition Reviews 80 (12): 2288–2300.

- Muoio, 2025. AI use is common among health systems—fleshed-out governance is not, survey finds. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/ai-and-machine-learning/ai-use-common-among-health-systems-fleshed-out-governance-not (accessed: 20 September 2025).

- Dyrda, L., 2024. 11 health systems leading in AI. UC San Diego Center for Health Innovation. https://healthinnovation.ucsd.edu/news/11-health-systems-leading-in-ai#:~:text=The%20Mayo%20Clinic%20is%20the,new%20healthcare%20tools%20and%20treatments. (accessed: 20 September 2025).

- Durlach, P., Fournier, R., Gottlich, J., Markwell, T., McManus, J., Merill, A., et al. The AI Maturity Roadmap: A framework for effective and sustainable ai in health care. New England Journal of Medicine. (accessed: 3 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Oracle, 2025. Oracle, Cleveland Clinic, and G42 announce strategic partnership to launch AI-based global healthcare delivery platform. Oracle. https://www.oracle.com/news/announcement/oracle-cleveland-clinic-g42-announce-strategic-partnership-to-launch-ai-based-global-healthcare-delivery-platform-2025-05-16/ (accessed: 20 September 2025).

- Landi, H., 2025. Oracle Health debuts AI-powered EHR designed as a ‘voice-first’ solution embedded with agentic AI. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/health-tech/oracle-health-debuts-ai-powered-ehr-designed-voice-first-solution-embedded-agentic-ai (accessed: 20 September 2025).

- Zhang, J., Zhao, D. Zhang, X. China’s universal medical insurance scheme: progress and perspectives. BMC Global Public Health 2 (62). [CrossRef]

- World Bank, 2025. Health expenditures. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=CN (accessed: 20 September 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).