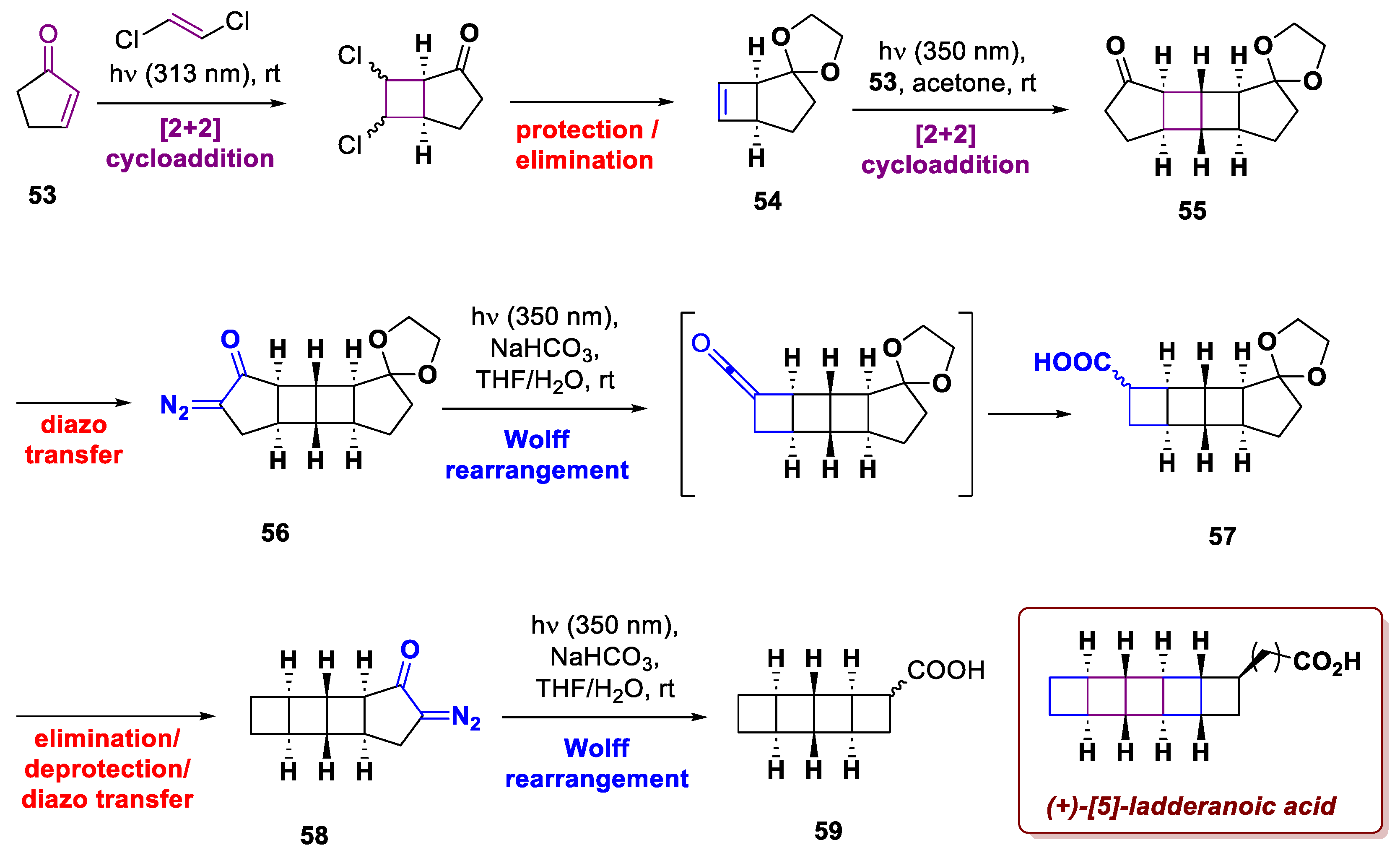

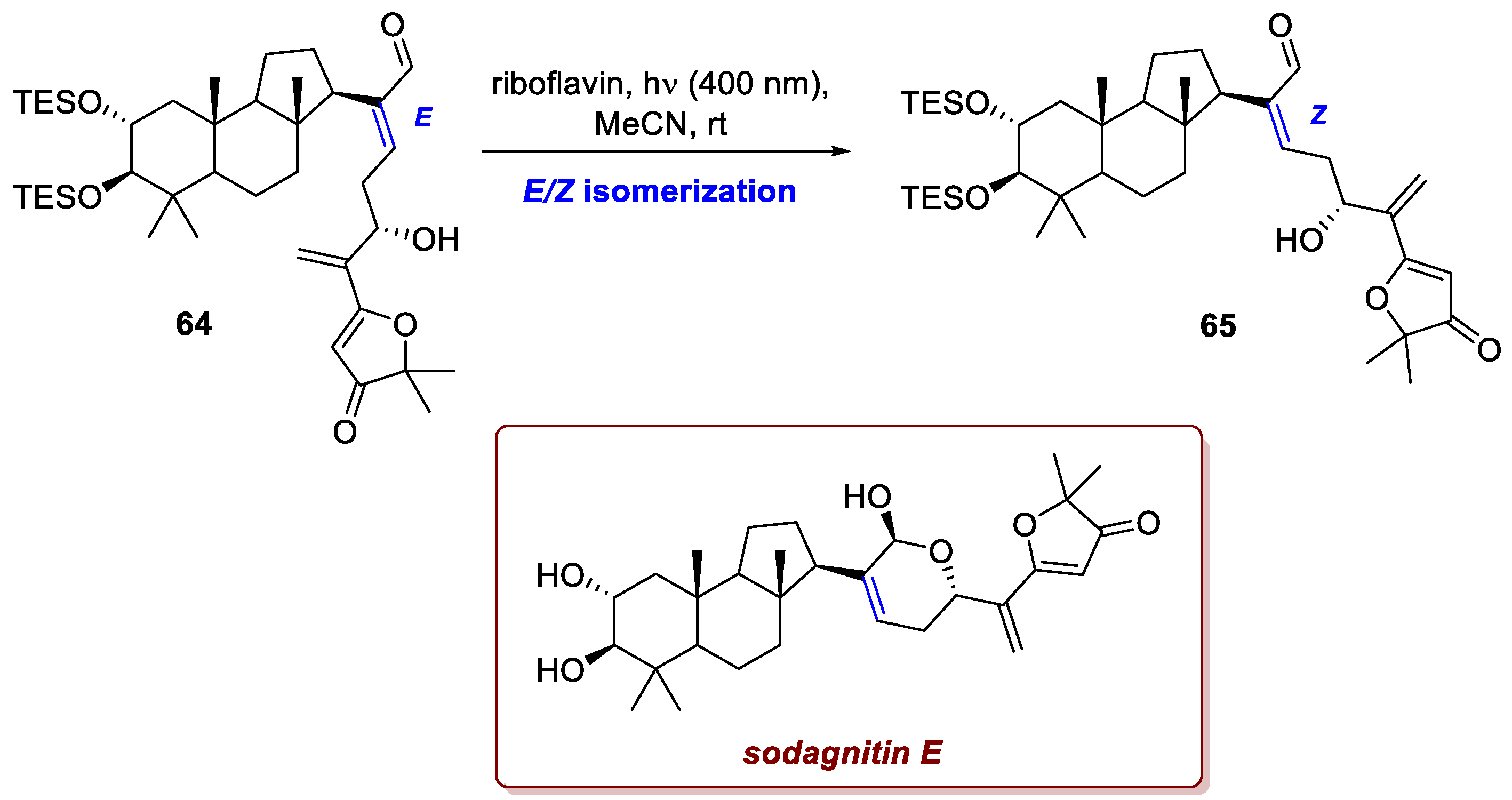

Among them, the [2+2]-cycloaddition stands out as a powerful method for forming cyclobutane rings—structural motifs that are widespread in natural molecules. In most cases, the use of light has been the key element enabling chemists to achieve this assembly during synthesis. A noteworthy subclass is represented by Paternò–Büchi reactions, whose relevance in this topic has been well recognized. Some recent studies have expanded on their scope and application; therefore, we have devoted a specific subchapter to this topic. Similarly, the [4+2]-cycloaddition has proven to be an invaluable tool in total synthesis, particularly in reactions leading to endoperoxides. The use of singlet oxygen in Diels–Alder reactions involving dienes and furan moieties has emerged as an interesting strategy for achieving high levels of oxygenation along carbon chains, a typical feature of these products. Finally, several other photochemical methods for ring construction have attracted attention, such as the Norrish–Yang cyclization and the Nazarov cyclization. Given their growing relevance and the recent publications on the topic, these transformations are discussed together in a miscellaneous subchapter.

2.1. [2+2]-Photocycloadditions: Accessing Strained Cyclobutane Rings

As mentioned in the introduction, [2+2]-cycloadditions are of vital importance, as they enable the incorporation of four-membered rings into complex molecular frameworks. Despite the inherent strain of the cyclobutane ring, this structural motif is widely distributed and plays a crucial role in a broad range of natural products.

Two reaction pathways are commonly used to photochemically assemble cyclobutane motifs: the first involves the direct excitation of one of the two substrates—typically an α,β-unsaturated ketone, whose excitation leads, via a fast ISC, to a relatively stable triplet state. Accordingly, the reaction pathway is similar to that of the Paternò–Büchi cycloaddition, proceeding stepwise via radical addition to the olefin, intersystem crossing of the resulting biradical to a singlet state, and final recombination to yield the desired cyclobutane product. The regioselectivity for the two possible products, commonly referred to as head-to-head or head-to-tail isomers, depends on the nature of the substituent on the second olefin, preferentially yielding the former with electron-withdrawing and the latter with electron-donating groups.

The second strategy involves photosensitization via energy transfer, using a photocatalyst with an easily accessible triplet state at a higher energy level than that of the target molecule. This approach allows even olefins with relatively low triplet energies to be effectively engaged in cycloadditions. Typical sensitizers include diarylketones (e.g. benzophenone) or common photoredox catalysts (e.g. ruthenium or iridium catalysts). In general, photocycloadditions perform best when the two reactive double bonds are installed within the same precursor, ideally with geometrical constraints to induce high degrees of regio- and stereoselectivity, which necessitates installing them onto complex molecular scaffolds. The utility of this class of reactions, however, is by no means limited to the introduction of the cyclobutane ring into the structure; on the contrary, they are particularly valuable also for enabling further modifications.

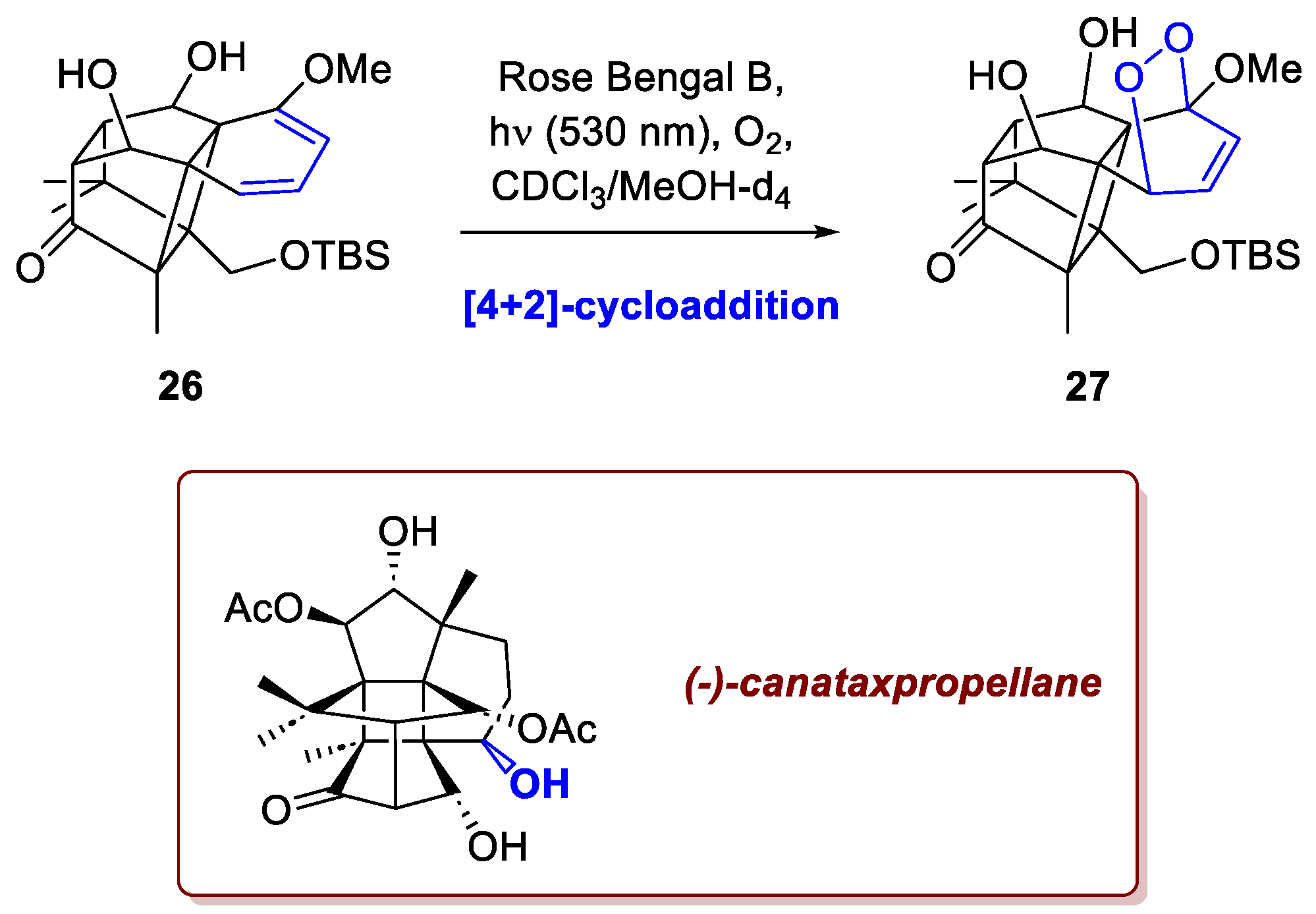

A recent example is the work of Jiao

et al. [

2], who successfully completed the total synthesis of the potent neurotoxin and NaV channel blocker, (+)-saxitoxin (

Scheme 1). Saxitoxin is a formidable synthetic target, characterized by a dense, tricyclic core and the presence of multiple guanidinium groups. The researchers’ success pivoted on a key, novel transformation: an asymmetric intramolecular [2+2]-photocycloaddition involving an alkenylboronate ester as chiral auxiliary. Recognizing that the conventional approach—namely, an intramolecular Michael addition to form the C4–C12 bond—would face significant thermodynamic and kinetic challenges, the researchers devised an unconventional retrosynthetic strategy. Their innovative alternative relied on the aforementioned intramolecular [2+2]-photocycloaddition between the alkenylboronate ester incorporated in an 8-oxoxanthine derivative

1. The success of this crucial step is rooted in the unique properties of the 8-oxoxanthine: its photoexcitation causes it to lose planarity and undergo intersystem crossing to the triplet state. This creative approach offered major advantages beyond simply bypassing the problematic Michael addition. Crucially, it eliminated the need for difficult chemo- and regioselective enol formation and provided excellent stereocontrol over the [2+2]-photocycloaddition. As depicted in

Scheme 1, the resulting intermediate

2, upon mild oxidation, was converted into a tertiary alcohol, which subsequently underwent a retro-aldol reaction to

3.

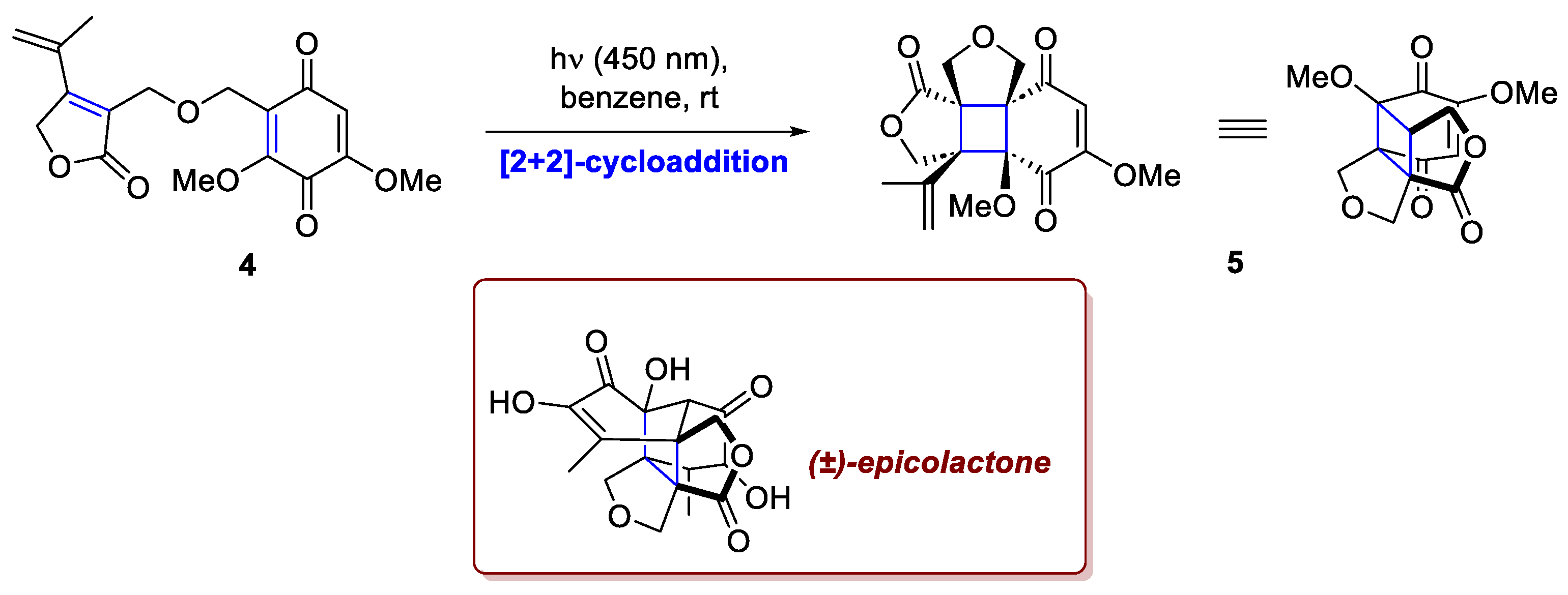

Similarly, in their work toward the total synthesis of epicolactone, Kravina and Carreira strategically exploited the intrinsic ring strain of the cyclobutane unit for a ring expansion methodology executed through a retro-aldol/aldol cascade sequence, which effectively constructed the central five-membered ring of the natural product's core [

3]. For the synthesis of this bioactive and structurally intricate secondary metabolite produced by endophytic fungi of the genus

Epicoccum associated with cash crops, the [2+2]-cycloaddition served as the key step for introducing the required structural complexity. This reaction between a quinone and an electron-deficient diene, both embedded in intermediate

4, is distinguished by its operational simplicity, proceeding under exceptionally mild conditions (just blue LED irradiation). The desired intermediate

5 is obtained with complete diastereoselectivity, remarkably establishing three quaternary stereocenters in situ from a conformationally flat starting material (

Scheme 2). This high level of selectivity is fundamentally attributed to two factors: the favorable polarity matching between the reaction components and the critical role of the covalent tether, which ensures optimal spatial proximity and conformational control through its carefully engineered length and flexibility.

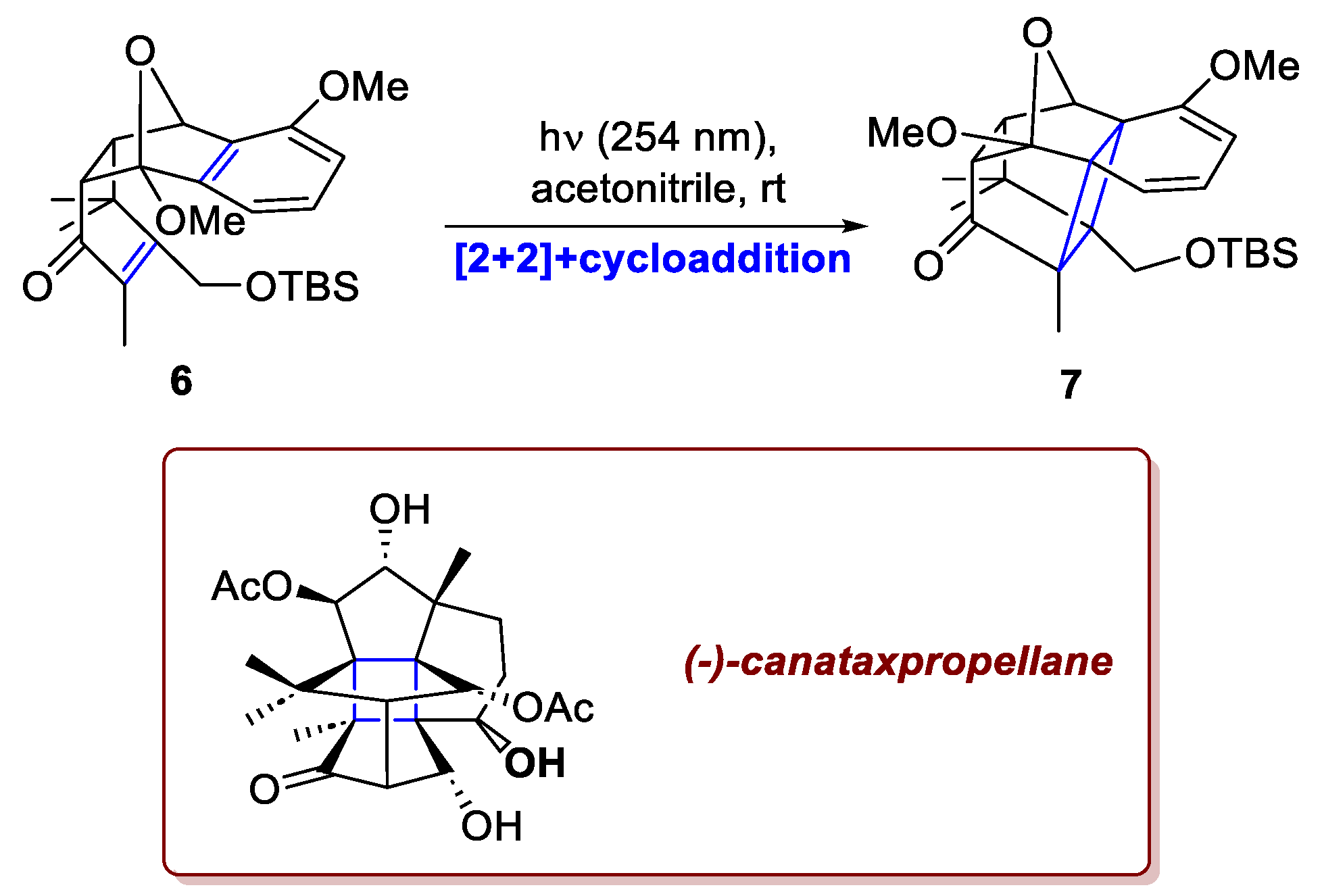

In the recent total synthesis of (–)-canataxpropellane, a structurally intricate diterpenoid natural product from

Taxus spp. reported by Schneider

et al., the ability to achieve exceptional regio- and stereoselectivity through a [2+2]-photocycloaddition once again proved to be essential [

4]. Closely related to the anticancer agent Taxol (paclitaxel), this molecule exhibits high complexity, combining two propellane motifs and twelve contiguous stereocenters—five quaternary and four located on a cyclobutane ring—within a densely oxygenated framework. The authors proposed an alkene–arene ortho-photocycloaddition that delivered the key intermediate in excellent yield (

Scheme 3). The efficiency of this transformation relied on both the polarity complementarity between the α,β-unsaturated ketone and the electron-rich arene in

6, and the spatial proximity of these moieties, achieved through the high diastereoselectivity of the preceding Diels–Alder step. As shown in the section dedicated to the [4+2]-cycloadditions (section 2.3 and

Scheme 10), the oxidative functionalization of

7 was also performed photochemically. In a total of 26 steps, the total synthesis of canataxpropellane was completed with an overall yield of 0.5%.

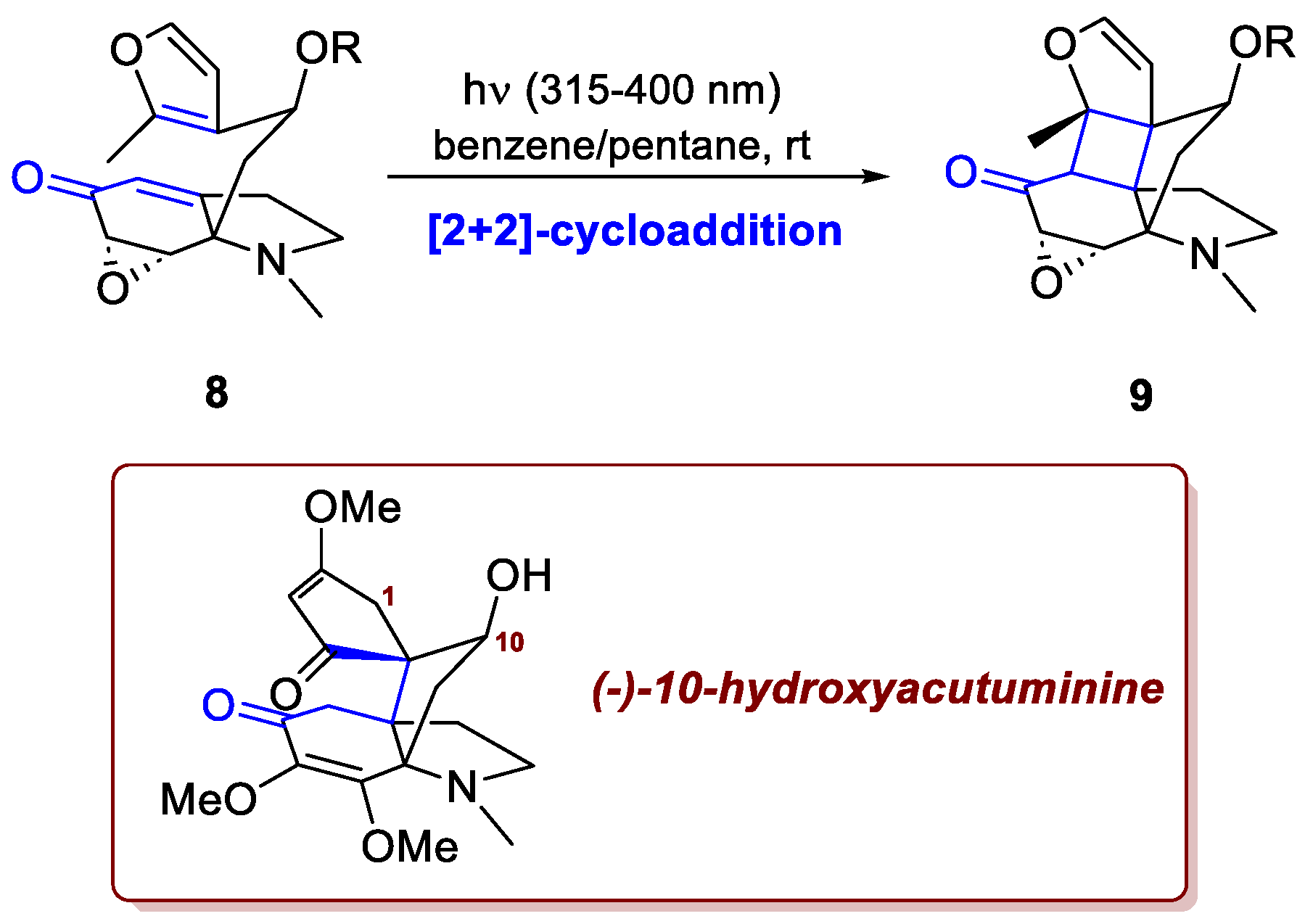

Another elegant example in which a [2+2]-cycloaddition has proven valuable for constructing densely functionalized propellane cores, is illustrated by Grünenfelder

et al. in the enantioselective total synthesis of (–)-10-hydroxyacutuminine [

5]. Although this strategy does not directly afford acutumine or acutuminine, it provides an elegant and efficient route to functionalized propellane cores. The target compounds differ from acutuminine by a hydroxyl at C10 and from acutumine by the absence of one at C1. As shown in

Scheme 4, the intramolecular [2+2]-cicloaddition between enone and the electron-rich methyl-substituted furan in

8, leads to the selective formation of a single regioisomer

9. In this synthesis, as in many other examples, the cyclobutane ring is not retained in the final product; nonetheless, its formation is crucial, as it enables the installation of two vicinal quaternary stereocenters in a single step. In the end, the enantioselective synthesis of (−)-10-hydroxyacutuminine was accomplished in 24 steps.

The functionalization of the reaction partners is essential, not only for achieving high regio- and stereocontrol but also for enabling the reaction itself. When less functionalized olefins are used in the construction of cyclobutane rings, direct irradiation of the starting material is often insufficient to promote the reaction. As mentioned in the introduction, another approach relies on the use of a photocatalyst, which can overcome this limitation. Using a suitable photocatalyst also allows the reaction to be carried out at different wavelengths, avoiding UV light, which can be problematic in complex molecules with many functional groups that may absorb UV and interfere with the [2+2]-cycloaddition. While the reaction generally proceeds via energy transfer, it can, in certain cases, also occur through SET.

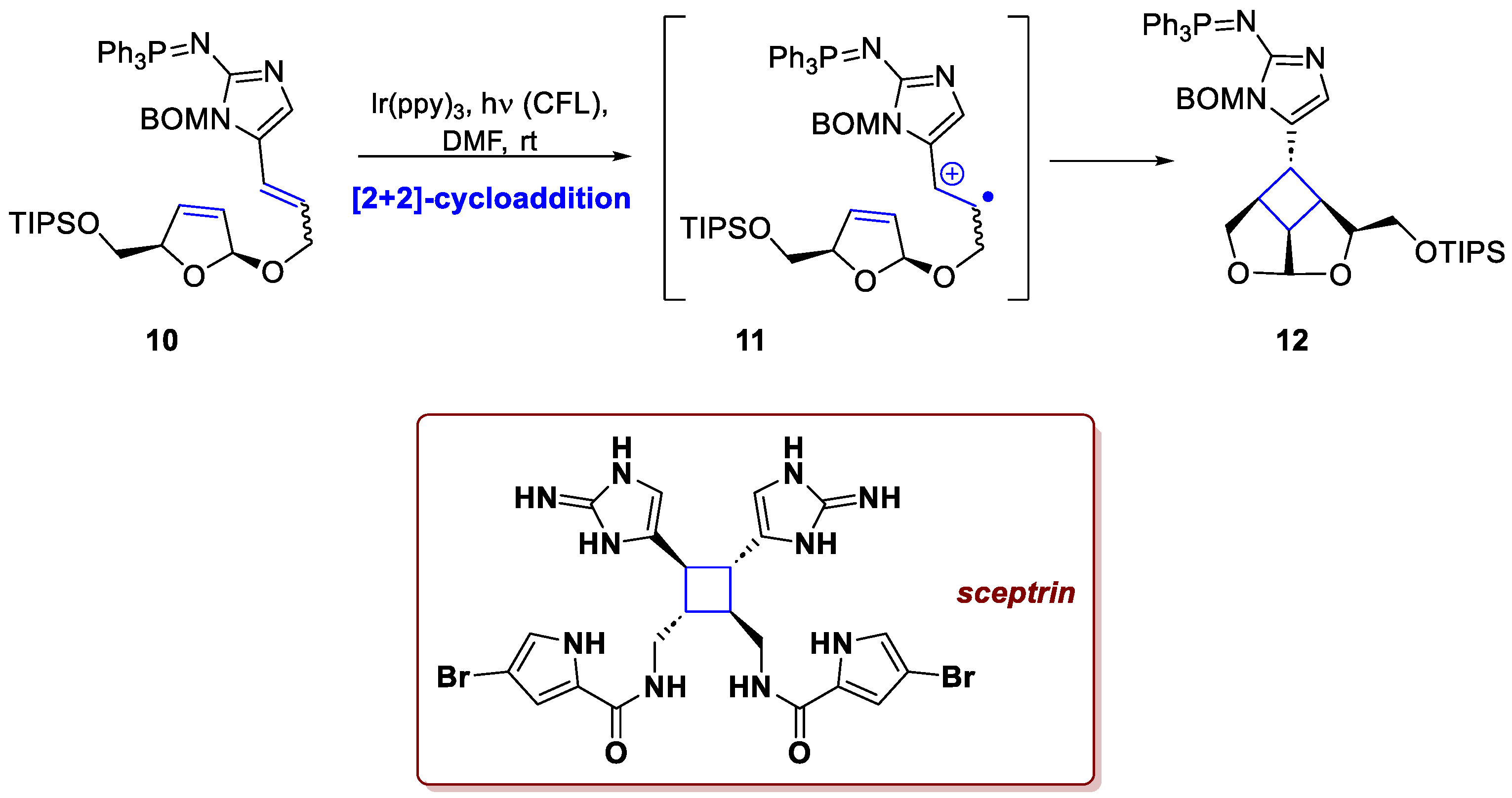

A remarkable example is provided by the total synthesis of sceptrin by Ma

et al. [

6]. Sceptrin is a dimeric alkaloid containing pyrrole–imidazole units, produced by a marine sponge that may use an enzyme-promoted single-electron oxidation as a central mechanism to promote the cycloaddition. Its high nitrogen content renders it highly polar, redox-labile, and pH-sensitive, posing significant synthetic challenges. The fundamental concept in their total synthesis involved the efficient construction of the central cyclobutane ring through a SET-mediated photocycloaddition, closely replicating the proposed biosynthetic route. Following a procedure reported by Lu and Yoon [

7], they performed the reaction of

10 with 3 mol% of Ir(ppy)

3 and a CFL, hence the photoinduced SET generated a radical cation intermediate

11, which smoothly underwent the desired [2+2]-cycloaddition to afford tricyclic adduct

12 in good yield and with an acceptable diastereomeric ratio (

Scheme 5). It should be emphasized that this approach also provided insight into the biosynthetic mechanism. When 9-fluorenone was used as a photocatalyst in place of Ir(ppy)₃, the reaction did not proceed, even though the two catalysts have comparable triplet energies. This outcome indicates that the dimerization operates through an oxidation–radical dimerization pathway rather than via energy transfer. Further elaboration led to

ent-sceptrin in 16 additional steps, with an overall yield of 0.4%.

Despite the synthetic breakthroughs achieved in batch mode, scaling up these demanding photochemical transformations remains a significant hurdle. It is in this context that the work of Latrache

et al. becomes particularly relevant [

8]. Their report details a unified, bio-inspired total synthesis for a family of eight dimeric natural products, namely nigramide R, chabamide, dipiperamides F and G, and the notable marine alkaloids sceptrin, dibromosceptrin, ageliferin, and dibromoageliferin. The core of this approach lies in a photocatalytic dimerization of either piperine or fully elaborated hymenidin- and oroidin-type precursors, executed

via catalyst-controlled [2+2] or [4+2]-cycloadditions. To overcome the limitations posed by prolonged photochemical exposure and the resulting photodegradation, they proposed a strategic shift from traditional batch processing to low-cost, 3D-printed photoflow reactors, enabling improved efficiency and significantly enhanced scalability compared to batch-based methods.

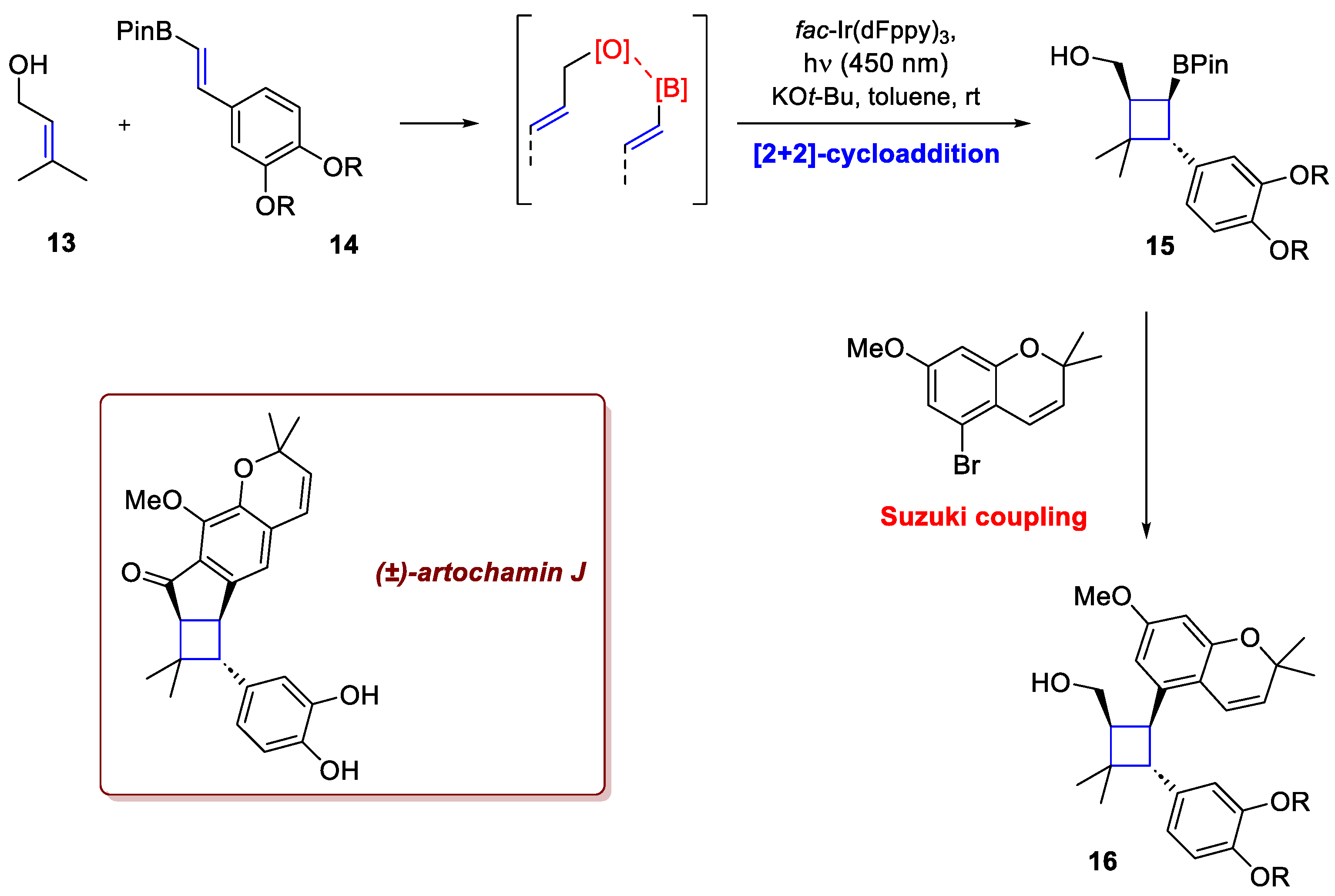

While most [2+2]-photocycloadditions typically necessitate an intramolecular setup to achieve high regio- and stereocontrol, Liu

et al. have demonstrated that this is not strictly required. In the total synthesis of (–)-artochamin J [

9], careful substrate design successfully by-passed the need for this covalent tethering. Exploiting boron's inherent oxophilicity, allylic alcohol

13 can undergo highly controlled photocycloadditions with alkenylboronate

14 via a temporary coordination (

Scheme 6), thereby ensuring excellent regio- and stereocontrol without a permanent intramolecular link. The reaction employs a straightforward protocol, typically using 1.0 mol %

fac-Ir(dFppy)

3 blue LED (450 nm) for the photosensitization. The transient association of the allylic alcohol with the Bpin moiety is the mechanistic linchpin that effectively guides the two reacting partners into the correct geometry, enabling the efficient cycloaddition despite their intermolecular nature. Following this key step, the resulting boronate ester intermediate

15 provides a robust handle for subsequent manipulation. Specifically, this intermediate allows for the direct functionalization of the cyclobutane adduct via a Suzuki coupling. This cycloaddition–Suzuki sequence consistently yielded the target product

16 in excellent yield and diastereoselectivity, requiring only a few additional steps to complete the total synthesis of the natural product. The same approach was also used for the synthesis of (–)-piperaborenine B.

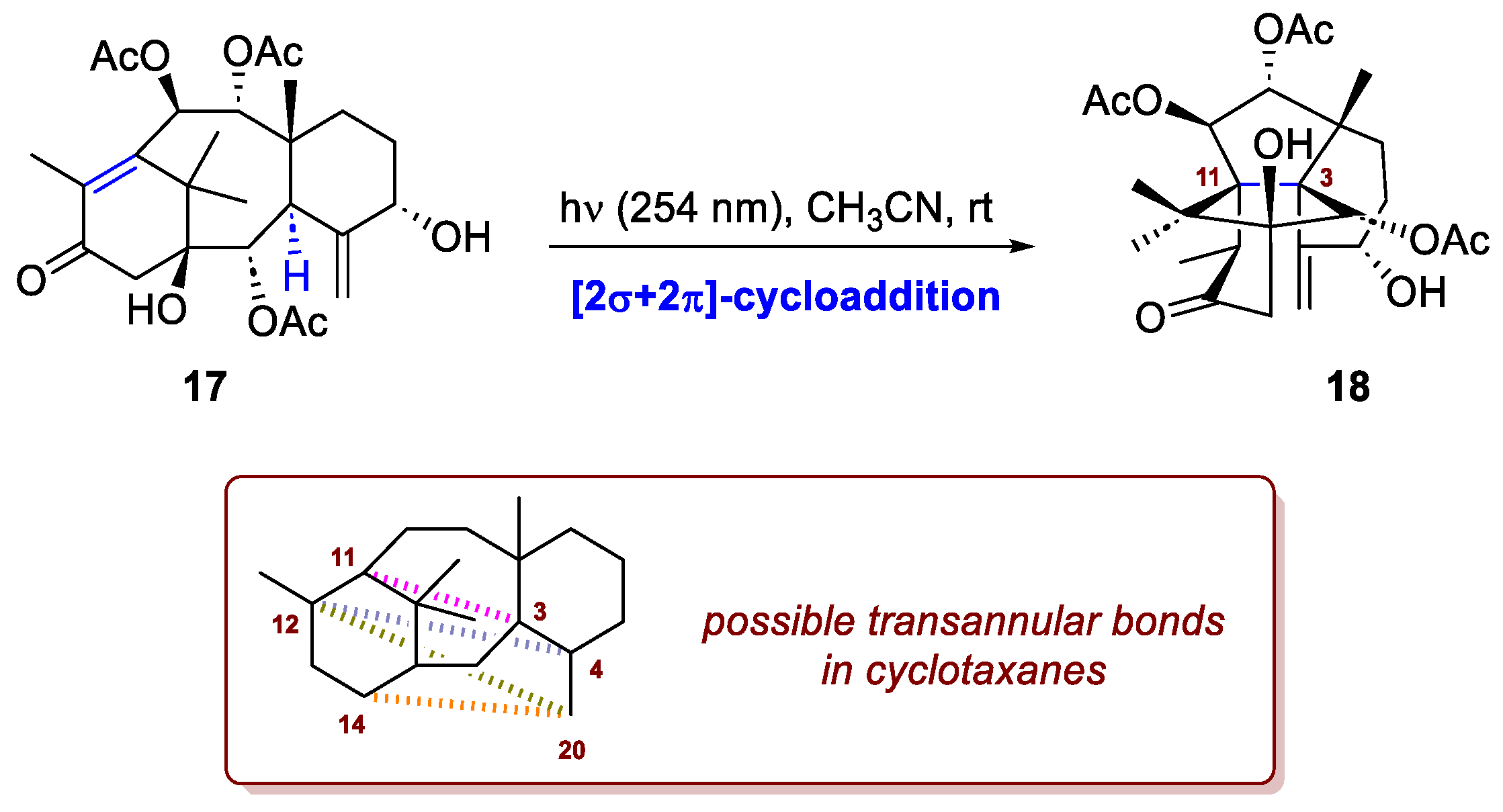

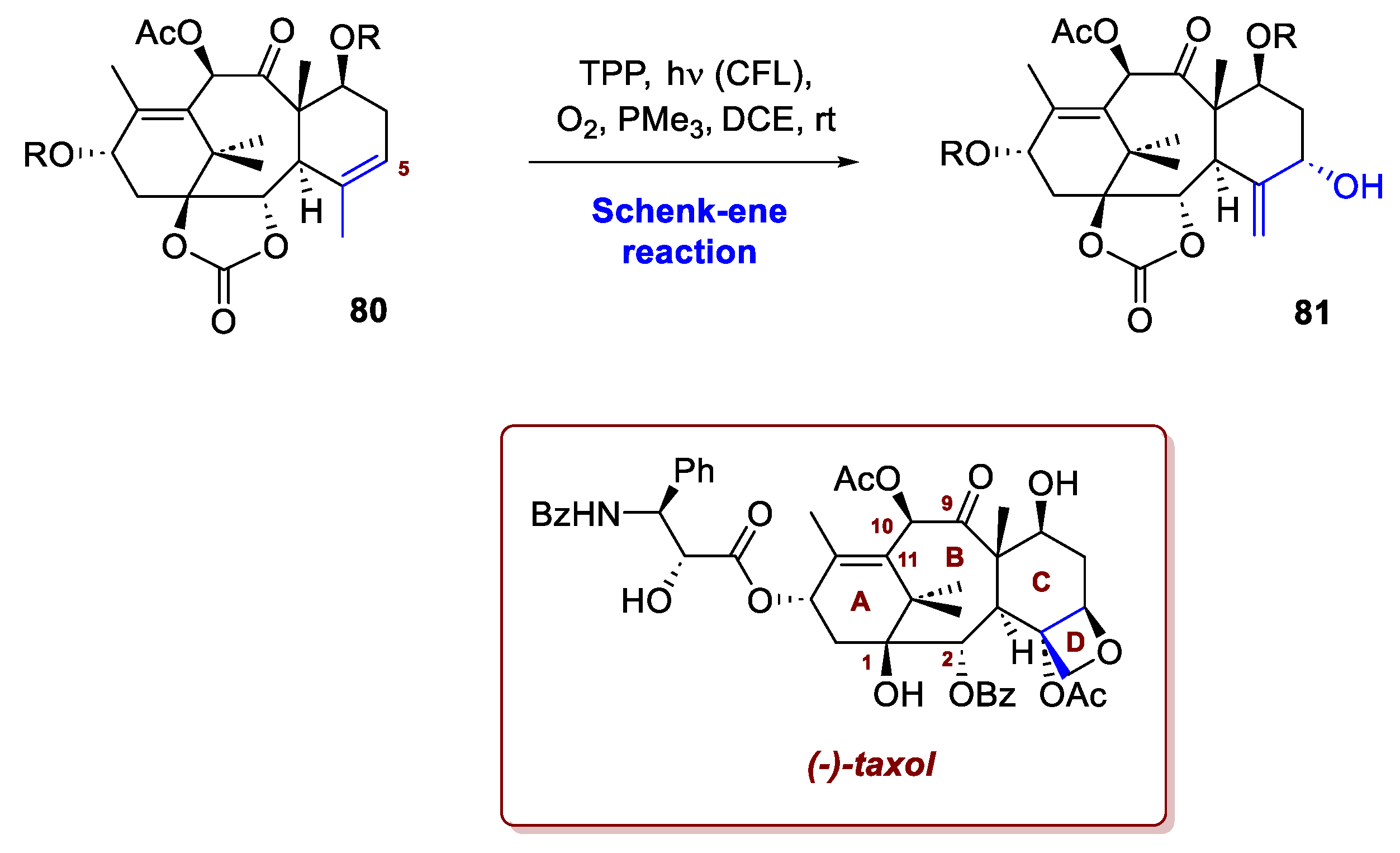

A recent application of this class of reaction has been reported by Schoch

et al. in their successful semisynthesis of the complex taxane diterpenoid, 1-hydroxytaxuspine C [

10], starting from readily available 10-deacetylbaccatin III. Taxanoid diterpenes, commonly known as taxanes, are secondary metabolites produced by slow-growing

Taxus species, known for their strong cytotoxic activity, making them highly valuable lead structures for drug discovery and pharmaceutical development. Among them, nonclassical taxanes featuring up to four transannular bonds (C3–C11, C14–C20, C12–C4, C12–C20) within the typical 6/8/6 core are classified as cyclotaxanes. The most common subgroup, the (3,11)-cyclotaxanes, characterized by a C3–C11 transannular bond, includes 32 naturally occurring members identified so far. In their work the authors developed a scale-up-friendly and reproducible route, providing the first gram-scale synthetic access to C1-hydroxylated cyclotaxanes. The final natural product is achieved in 17 steps and for the installation of the pivotal C3-C11 bond, inspired by literature, they adopted a photochemical transannular bond formation from enone

17 (

Scheme 7). Upon irradiation of

17 with 254 nm light under an inert atmosphere, 1.04 g of the desired (3,11)-cyclotaxane

18 was obtained, with no detectable formation of byproducts. It is important to emphasize that the mechanism of this transformation remains under investigation. A concerted σ2s + π2s pathway has been proposed as a plausible one, which justifies its inclusion in this subsection. Alternatively, excitation of the enone

17 to its first singlet excited state, followed by intersystem crossing to the triplet state, would generate a biradical intermediate. Facilitated by the close spatial proximity of C3 and C12, this species could undergo a 1,6-hydrogen atom transfer (1,6-HAT), forming a tertiary allylic radical. Subsequent recombination of the resulting C3,C11-diradical intermediate would then lead to the formation of the transannular C3–C11 bond.

2.2. The Paternò-Büchi Reaction: Assembling the Oxetane Ring

As previously mentioned, it is worth to include in this review a brief subsection dedicated to the Paternò–Büchi reaction. Setting aside the well-known controversy between Paternò and Ciamician regarding the origin of this reaction, it is known that in 1909 Paternò investigated the photochemical reaction of benzaldehyde with amylene and reported the formation of the corresponding [2+2]-cycloadduct. However, he was unable to distinguish between the two possible constitutional isomers of the oxetane, and the stereochemistry of the products could not be fully determined. Despite its potential, the Paternò–Büchi reaction was largely overlooked for several decades. It was not until 1954 that Büchi successfully repeated Paternò’s experiment and definitively identified the oxetane product. Traditionally, the Paternò–Büchi reaction is defined as a [2+2]-photocycloaddition between an alkene and the excited state of a carbonyl compound, leading to the formation of a four-membered oxetane ring. Although the reaction typically involves an excited carbonyl species reacting with a ground-state alkene, the reverse situation can also occur [

11]. The remarkable potential of this reaction lies in its ability to provide an efficient synthetic route to small heterocyclic structures such as oxetanes, which are commonly found in natural products and biologically active molecules. There can be found different naturally occurring oxetane-containing compounds, such as thromboxane A

2, mitrephorone A, and maoecrystal I, that also display a wide range of biological activities, including anticancer and cytotoxic effects. Regarding its role in total synthesis, the Paternò–Büchi reaction continues to hold considerable potential for further innovation and advancement. Although this transformation has been employed less frequently in natural product synthesis than the [2+2]-cyclobutane photocycloaddition, it has nonetheless been successfully applied to the syntheses of (

+)-preussin [

12], (

±)-oxetanocin [

13], and (

±)-1,13-herbertendiol [

14], although the oxetane ring is not always preserved in the final product. Additional noteworthy examples, albeit from earlier studies, are discussed in the comprehensive review by Kärkas

et al. [

15].

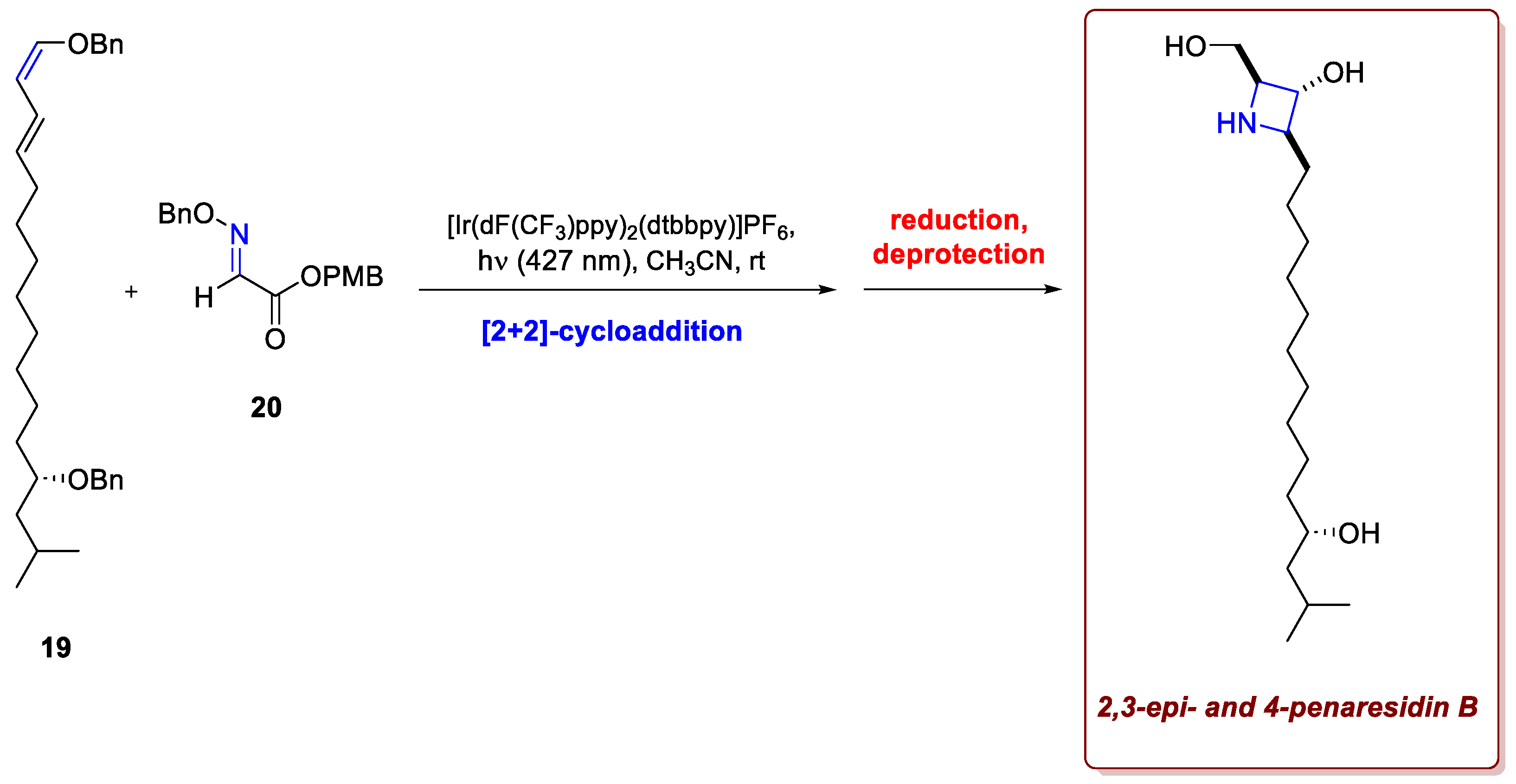

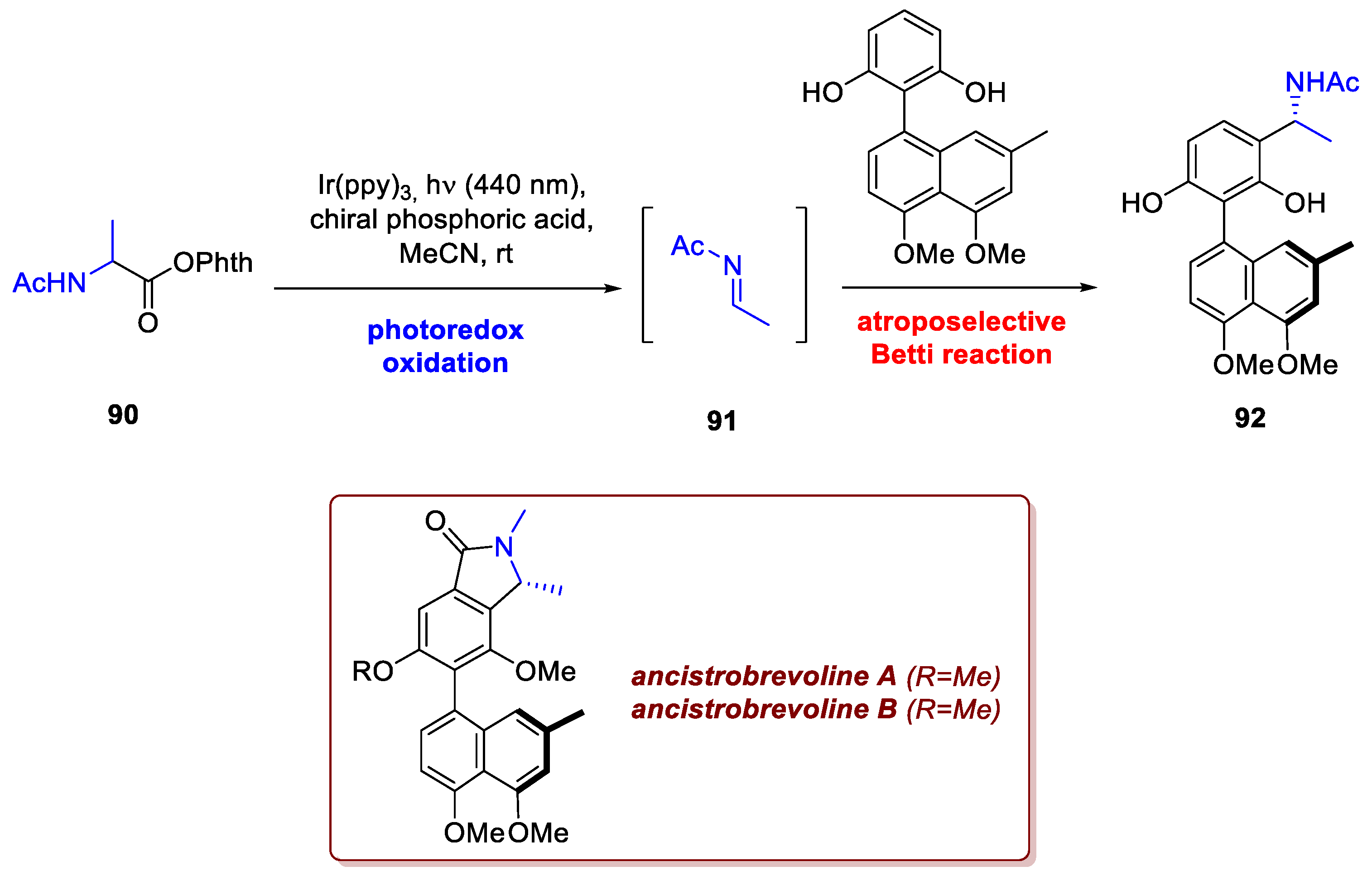

While classical Paternò–Büchi reactions are quite widespread throughout the synthetic records, their aza-variant delivering azetidines is remarkably underdeveloped, mainly due to the fast relaxation

via isomerization of the imine excited state that hampers the development of cycloaddition strategies via direct irradiation. In this regard, the recent work of Wearing

et al. represents a huge leap forward in accessing 4-membered nitrogen-containing rings in a straightforward fashion [

16]. To extend the scope of the aza-Paternò–Büchi cycloaddition to acyclic imine equivalents in an intermolecular fashion, the researcher tailored the reactivity profile of the substrates, using conjugated oximes as imine components and conjugated alkenes as cycloaddition partners. The lowering of the frontier orbital energy gap through conjugation allows for a [2+2]-cycloaddition to occur upon excitation of the alkene

via EnT using an iridium photocatalyst under blue light irradiation. This new strategy for accessing 2,3,4-substituted azetidine scaffolds avoids harsh reaction conditions (

e.g. reduction of β-lactams), steric constraints (

e.g. in nucleophilic cyclizations) for densely substituted products, or long reaction routes that were otherwise limiting the access to installing azetidine rings. Remarkably, this strategy was implemented in the synthetic pathway towards penaresidin A and B, sphingosine alkaloids isolated from the marine sponges

Penares spp. known for their biological activity and their cytotoxic effects against tumour cells (

Scheme 8). After the assembly of diene

19, the desired azetidine core was assembled with ease using conjugated oxime

20 and standard reaction conditions, and followed by reduction and deprotection, 2,3-

epi- and 4-

epi-penaresidin B were obtained. Noteworthy, related penaresidin stereoisomers have recently been demonstrated to exhibit similar or improved cytotoxicity compared with the natural diastereomer.

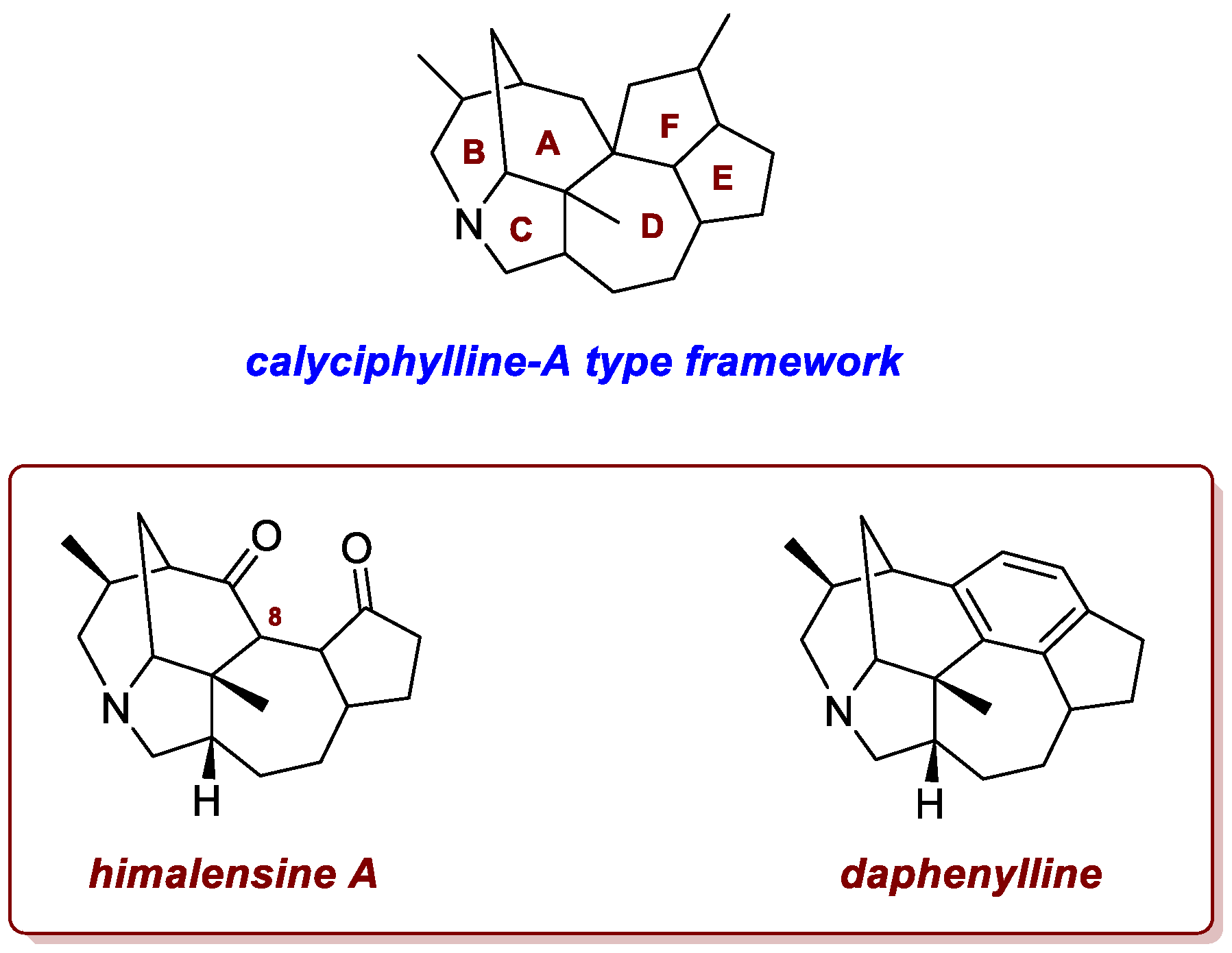

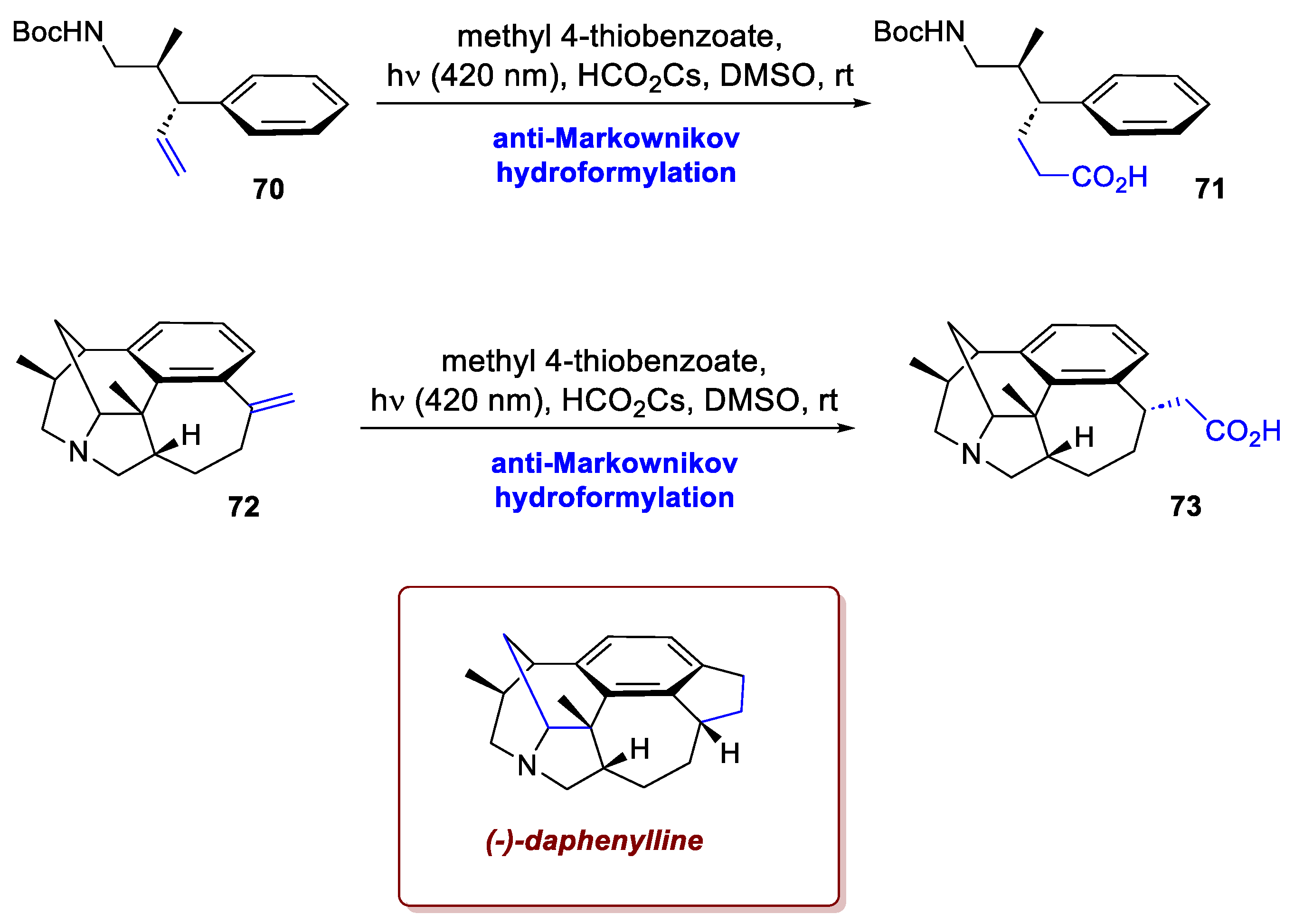

A thia-Paternò–Büchi reaction was used by Wright

et al. in the synthetic approaches to calyciphylline A-type daphniphyllum alkaloids, himalensine A and daphenylline [

17]. Since the discovery of calyciphylline A, over 50 calyciphylline A-type daphniphyllum alkaloids have been reported, making them the largest subclass of this alkaloid family (

Figure 1). Many of these molecules show some structural differences from the original type: himalensine A, isolated in 2016 from

Daphniphyllum himalense by Yue and colleagues, lacks the F-ring and a quaternary carbon at C8, while daphenylline, isolated from the fruits of

Daphniphyllum longeracemosum in 2009, has a unique benzene-fused ring within the calyciphylline A-type framework (another recent report on the total synthesis of daphenylline is discussed in section 3.3).

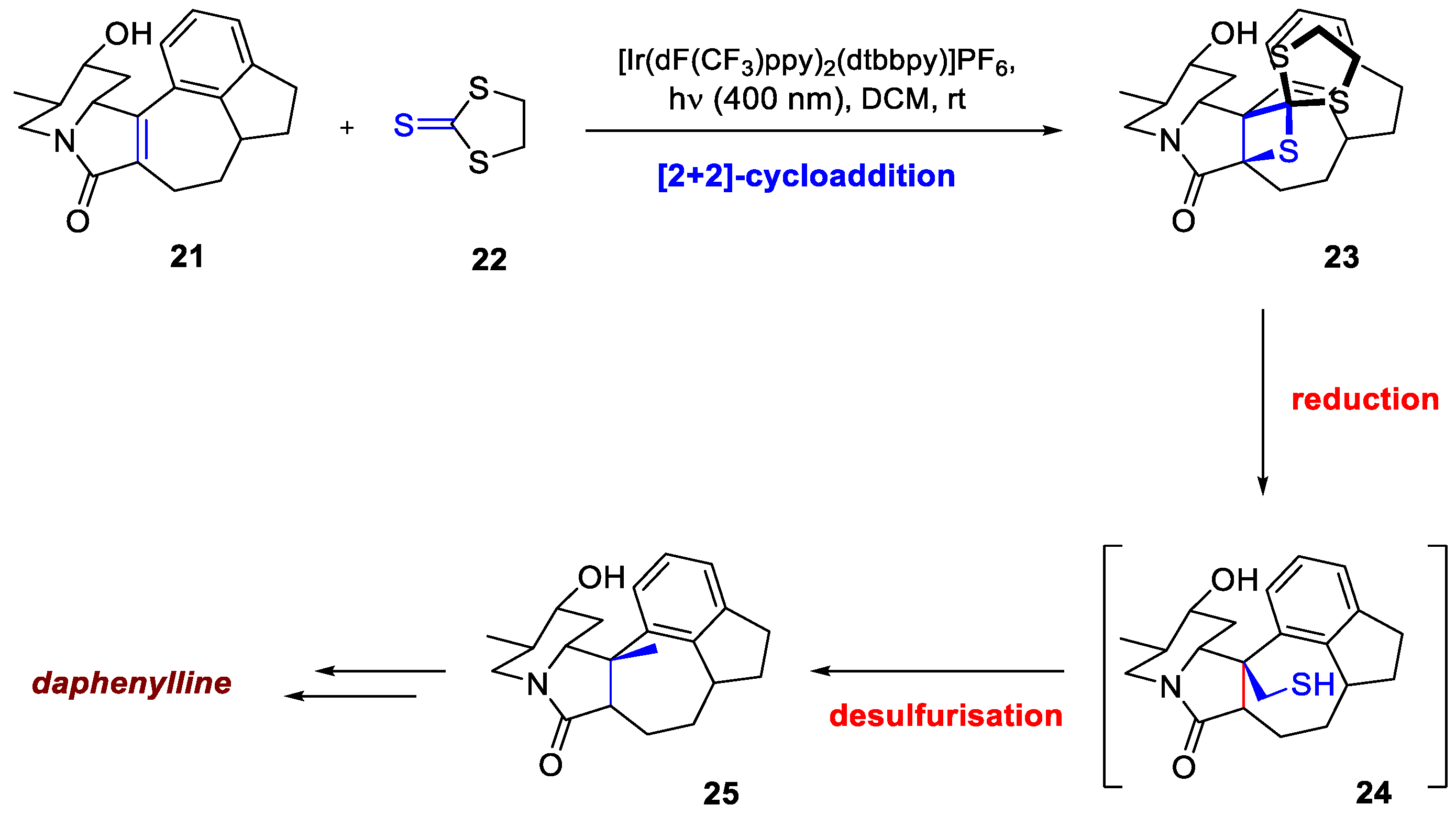

The synthesis of daphenylline faced a major difficulty in introducing a crucial quaternary methyl group. Initial attempts to use a standard [2+2]-photocycloaddition/bond cleavage sequence failed because the reaction exclusively yielded unwanted head-to-tail products, which prevented the necessary stereospecific C–C bond cleavage. To overcome this, the team made a key strategic change, successfully exploiting an intermolecular thia-Paternò–Büchi reaction. Inspired by Padwa's work [

18], they recognized that thioamides could form C–C bonds via thietane intermediates. This approach fundamentally reversed the course of the synthesis by drastically improving the selectivity. Unlike previous attempts, alkyllithium reagents preferentially react at the sulfur atom of thiones, leading to superior control and enabling the desired transformation; the thietane intermediates can subsequently be desulfurized with Raney nickel. Guided by these insights, irradiation of compound

21 with 400 nm blue LEDs in the presence of trithiocarbonate

22 and [Ir(dF(CF₃)ppy)₂(dtbbpy)]PF₆, as per the previous report by He

et al. [

19], resulted in a 55% yield for spirocyclic thietane

23 (77% based on recovered starting material). The thietane intermediate

23 was first reduced to

24 with LiAlH₄, followed by quenching with a Raney Ni/H₂O slurry to complete desulfurization to

25. After a few additional steps, this concise 11-step total synthesis was completed (

Scheme 9).

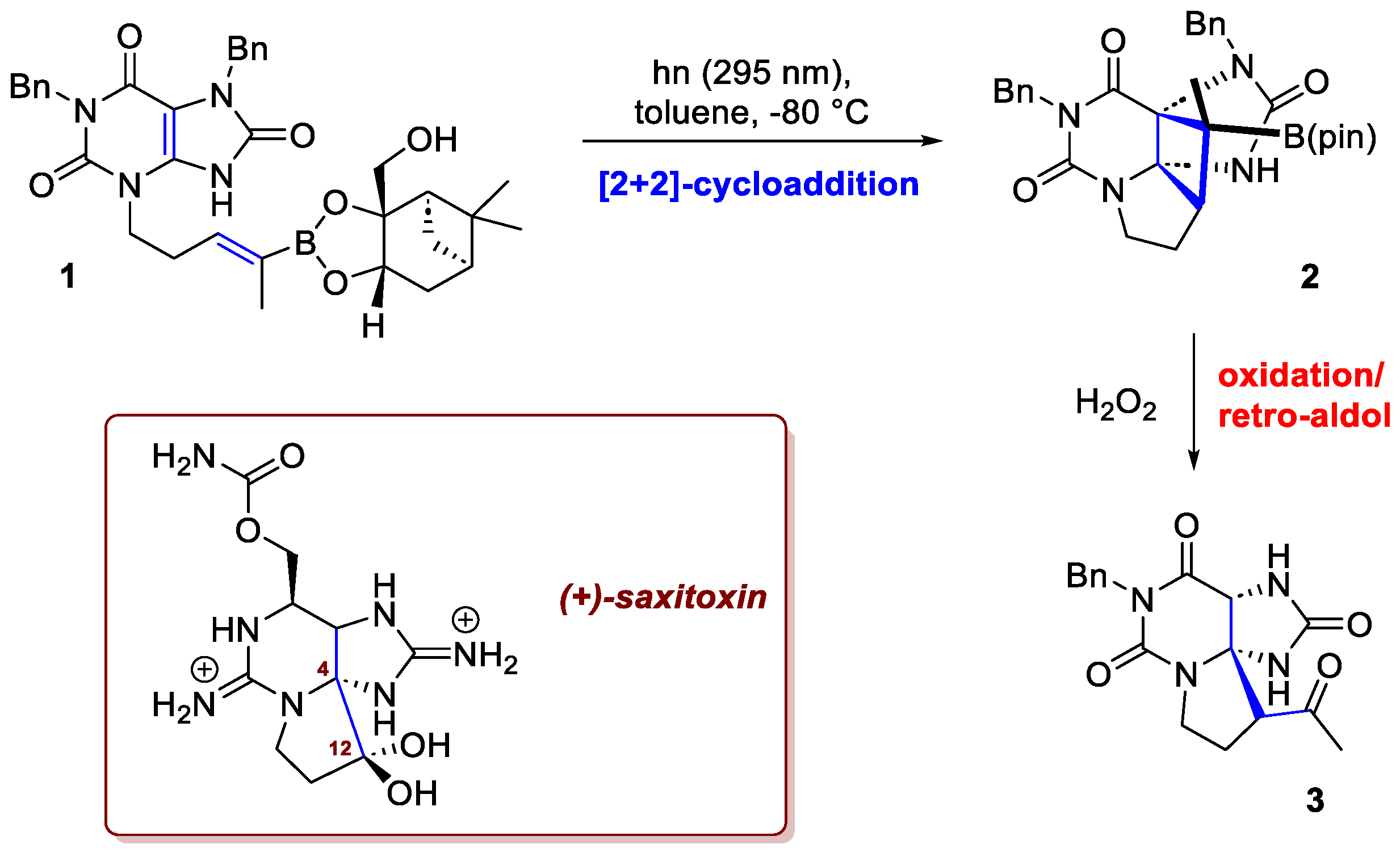

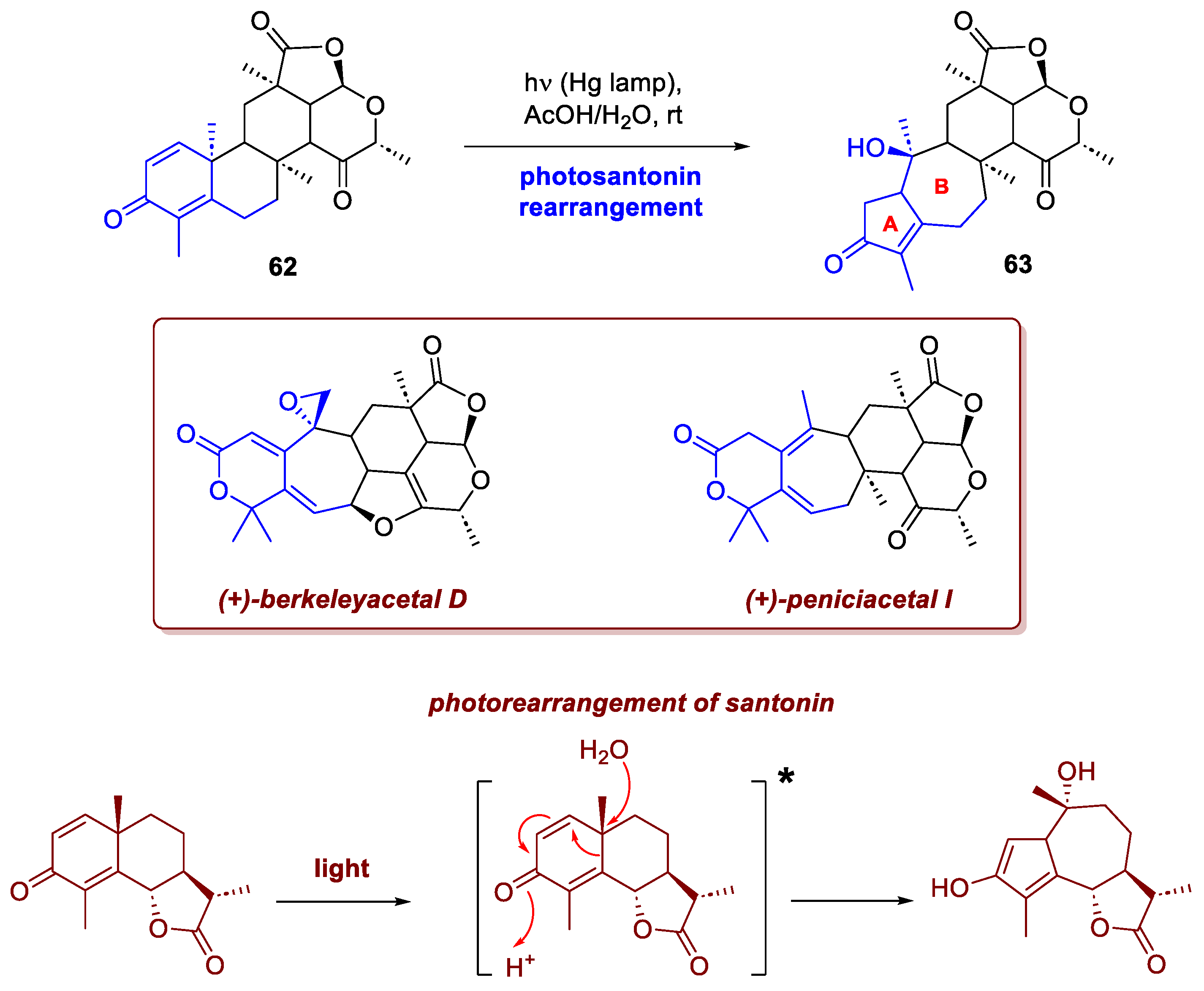

2.3. [4+2]-Cycloadditions with Singlet Oxygen: Controlled Oxygenation and Endoperoxide Formation

The [4+2]-cycloaddition is one of the most powerful and versatile synthetic tools derived from singlet oxygen chemistry. This Diels-Alder type reaction is widely exploited for introducing multiple oxygen atoms and forming endoperoxide moieties. These endoperoxides are privileged, strained-ring structures that can be readily transformed into other valuable functionalities, making this method crucial for complex synthesis. In this regard, the widespread use of photosensitizers granted easier access to the very peculiar and highly reactive reagent, singlet oxygen. Singlet oxygen can also be generated through thermal pathways, but photosensitization offers the most appealing conditions. It only requires an oxygen source, a catalyst (methylene blue, rhodamine B, and tetraphenylporphyrin being the most common), and a narrow-band source of irradiation, thereby granting extremely selective and mild conditions. In general, starting from the 1980s, the use of singlet oxygen in total syntheses has become increasingly frequent, as its unique reactivity allows for the engineering of biomimetic approaches toward natural targets. Cycloaddition reactions involving singlet oxygen can target conjugated systems, proceeding either through a [4+2]-pathway to yield endoperoxide products— the focus of this section— or through a [2+2]-pathway to form dioxetanes.

As anticipated in section 2.1, oxidative functionalization was used to elaborate the [2+2]-cycloadduct toward the synthesis of canataxpropellane [

4]. The diene moiety is expediently employed to incorporate two additional oxygen atoms with complete stereoselectivity (through an exceptionally mild and selective photoreaction utilizing Rose Bengal B and green light. Due to the rigid conformation of intermediate

26, imposed by the four-membered ring, only the diene's

exo-face is accessible. This steric control forces the exclusive formation of the desired endoperoxide product

27, that is further elaborated to afford the natural product.

Scheme 10.

[4+2]-cycloadditions in the synthesis of canataxapropellane.

Scheme 10.

[4+2]-cycloadditions in the synthesis of canataxapropellane.

The recent total synthesis of (+)-tetrodotoxin by Murakami

et al. provides another compelling example of this transformation's applicability [

20]. Tetrodotoxin, initially isolated from puffer fish (order

Tetraodontiformes), possesses an intriguing, highly oxidized structure featuring a dioxaadamantane core fused with a cyclic guanidine moiety. Due to its role as a potent voltage-gated sodium channel blocker, the compound holds significant medicinal importance as a potential scaffold for developing a new class of analgesics. The synthetic route developed by the authors commences with α-methyl-D-mannoside as the primary chiral source. Thanks to a [4+2]-cycloaddition with singlet oxygen on the intermediate

28 (

Scheme 11) using Rose Bengal, that proceeded with complete stereoselectivity, the intermediate

29 was obtained as a single isomer following the reductive cleavage of the endoperoxide photoadduct

30. This approach was essential to obtain the resultant allylic diol which permitted further enantioselective oxidation of the bicyclic core via a Sharpless epoxidation, followed by additional modifications, to afford the target compound.

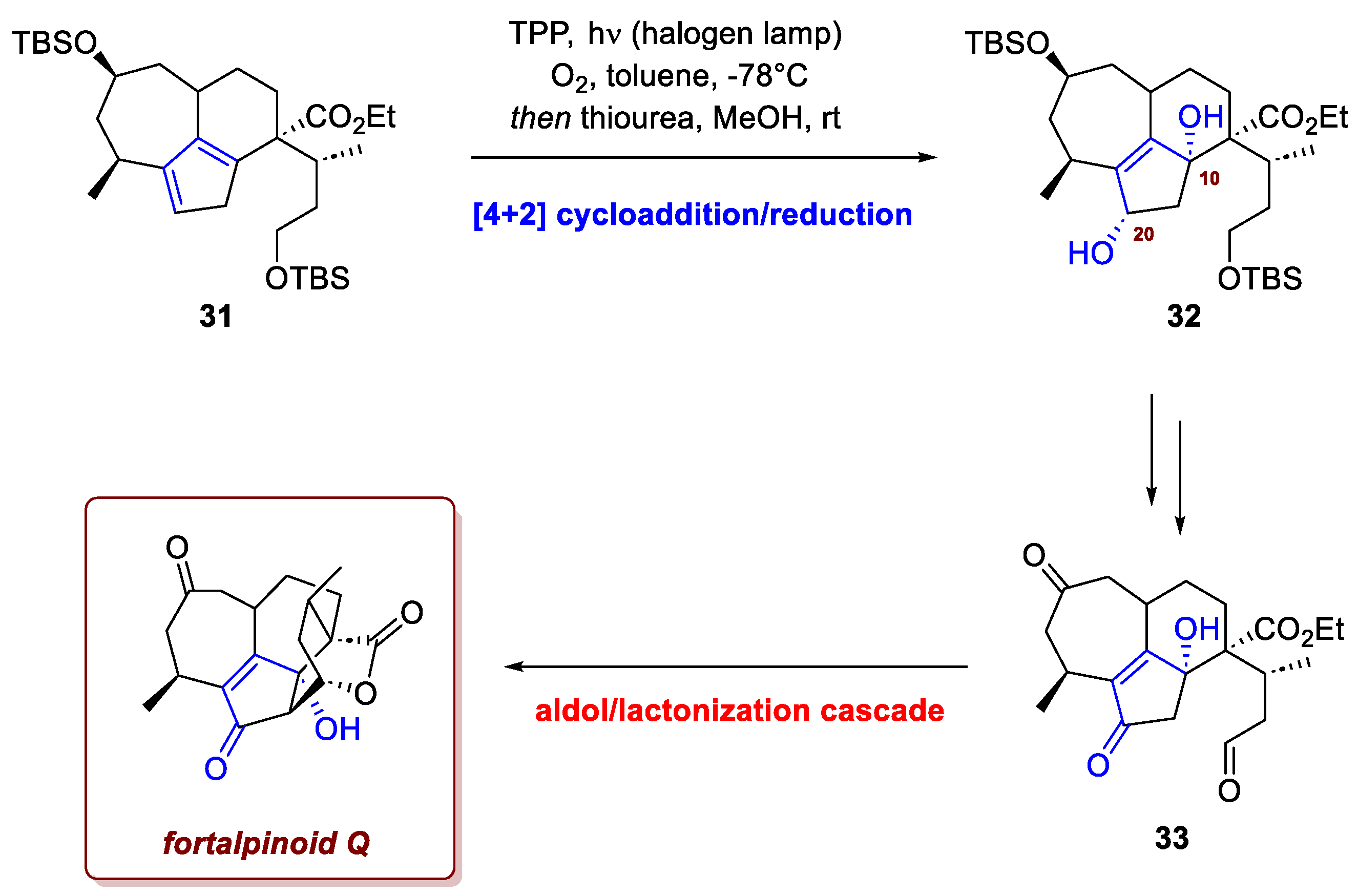

Photooxygenation was also pivotal for Mao

et al. in the 15-step, enantioselective total synthesis of fortalpinoid Q [

21], a specific member of the

Cephalotaxus diterpenoids family. This family is a captivating class of natural products holding significant interest due to both their complex structures and their promising biological activity. Fortalpinoids share a 7-6-5-6-6 pentacyclic ring skeleton as their common structural features, and a key strategic challenge in their synthesis was the construction of the D/E bicyclic ring system. Initially, the authors had envisioned generating this bicyclic system via an aldol-lactonization cascade directly from intermediate

31, following the hydroboration of the cyclopentadiene double bond as described by Frey

et al. [

22] (

Scheme 12). However, all attempts to implement this crucial cascade failed due to a detrimental side-reaction: a vinylogous aldol condensation. This competing, undesired reaction derailed the cyclization sequence. In response to this significant hurdle, a successful, revised strategy was developed. To set the stage for the cascade, the authors introduced an essential modification to the pentacyclic core. This involved a singlet oxygen hetero-Diels-Alder reaction with the cyclopentadiene moiety of intermediate

31. This reaction, followed by the ring-opening of the resulting endoperoxide with thiourea, stereoselectively furnished diol

32. The stereochemical outcome of the Diels-Alder reaction results from the approach of the singlet oxygen to the less sterically hindered face of the cyclopentadiene moiety. This ingenious step served a dual purpose: it introduced the necessary C20 oxidation state and, crucially, it generated an additional C10 hydroxyl group. It was the presence of this C10 hydroxyl group that successfully prevented the parasitic vinylogous aldol reaction that had plagued the previous unsuccessful attempts, allowing the desired cyclization to proceed. The efficient aldol-lactonization cascade ultimately provided the desired fortalpinoid Q in 57% yield from

33.

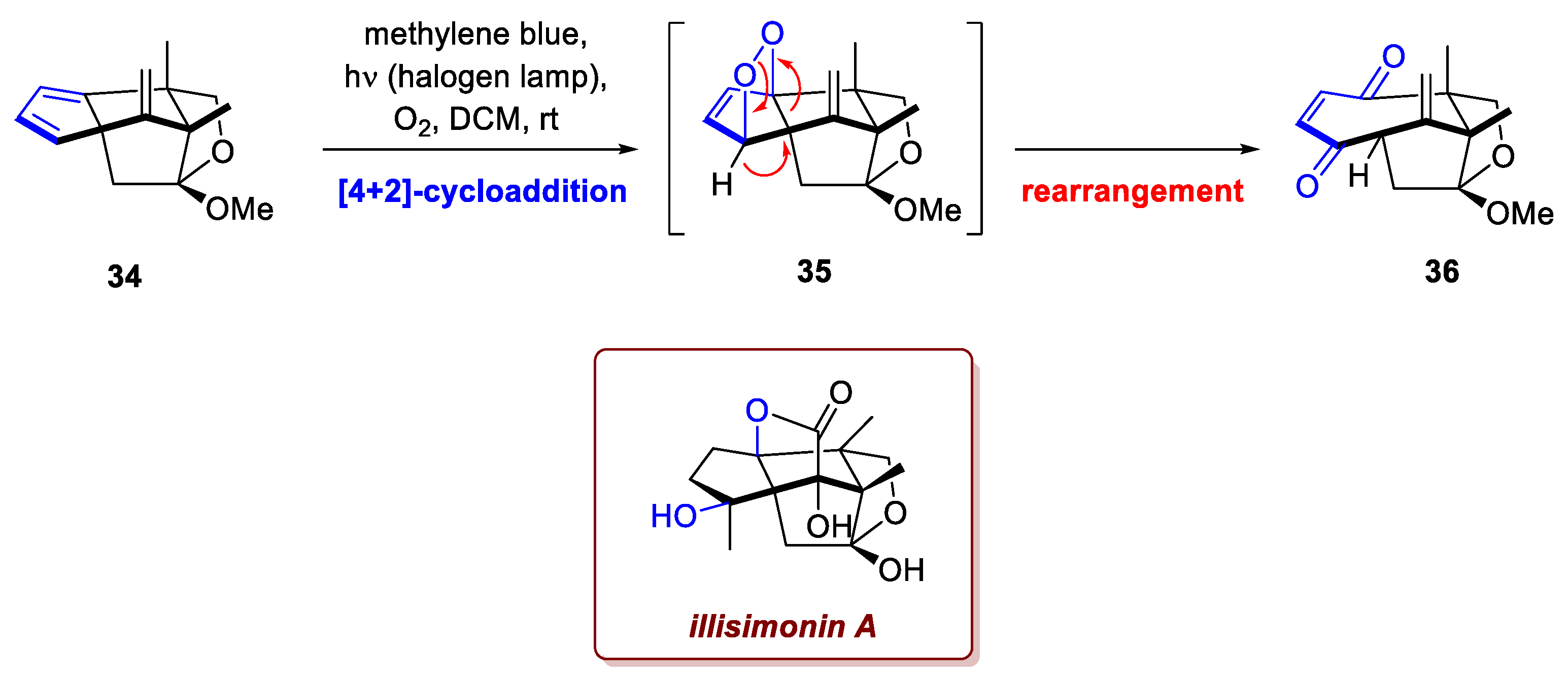

The research by Zhu

et al. on the gram-scale total synthesis of (±)-illisimonin A, a sesquiterpenoid isolated from the

Illicium genus, provides a significant example of a planned key step that failed to deliver the desired intermediate [

23]. This molecule features a highly congested cage-like 5/5/5/5/5 pentacyclic scaffold, with 7 contiguous stereocenters, over a total of only 15 carbon atoms. Specifically, in their attempt to form the polycyclic framework and introduce the oxygenation pattern, the proposed oxa-[4+2]-cycloaddition between a cyclopentadiene intermediate

34 and singlet oxygen was expected to yield a peroxide bridged intermediate

35 (

Scheme 13). However, instead of the desired product, the reaction exclusively furnished a rearranged, ring-expanded product

36. The instability of

35 leads to a consecutive sequence involving O-O bond cleavage, C-C bond cleavage, and hydrogen migration, ultimately resulting in the rearrangement to the conjugated enedione

36. To circumvent this synthetic roadblock, the authors strategically shifted their approach, utilizing a nitroso-Diels–Alder reaction as a crucial alternative. This method successfully enabled the precise installation of the correct oxidation state and the construction of the final molecular architecture, ultimately leading to the completion of the gram-scale total synthesis.

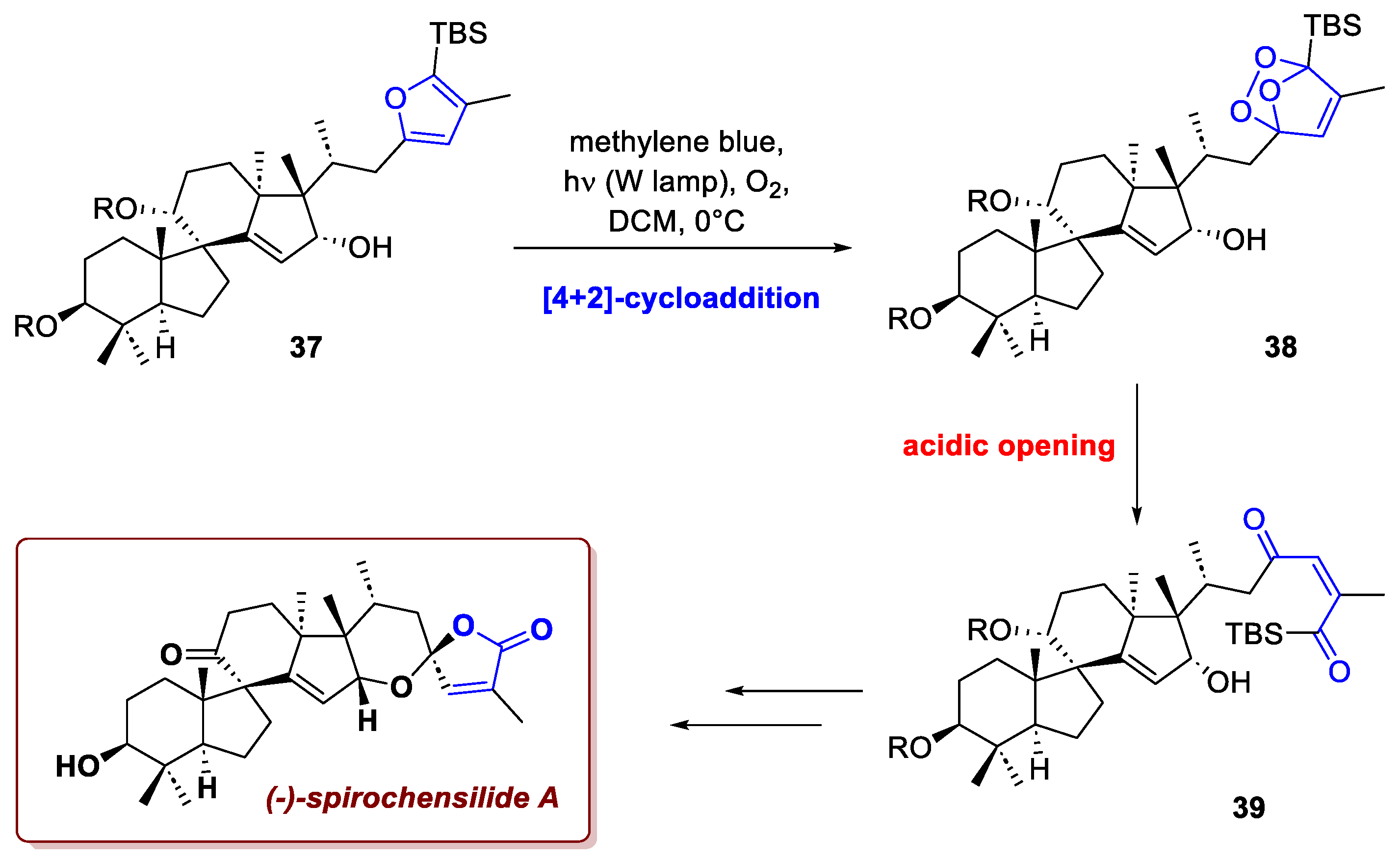

In addition to dienes, there are also furans that are highly effective substrates for singlet oxygen [4+2]-cycloadditions, and the resulting endoperoxides are widely recognized and utilized in chemical synthesis. A striking example of this methodology is demonstrated in the asymmetric total synthesis of (±)-spirochensilide A by Liang et al. [

24]. Isolated from Abies chensiensis (an endemic Chinese coniferous tree), spirochensilide A presents a formidable structural challenge, totalling six rings and nine centres of chirality. The molecule features an uncommon spirocyclic core, two pairs of vicinal quaternary carbon stereocenters, and an anomeric spiroketal. The strategic approach designed to address these peculiarities relied on a singlet oxygen [4+2]-cycloaddition followed by cyclization to install the spiroketal ring (

Scheme 14). The photocycloaddition took place smoothly from advanced intermediate 37 using methylene blue and a tungsten lamp. This furnished the endoperoxide 38, which was immediately opened under acidic conditions to give compound 39. Final deprotections and manipulations ultimately afforded the target molecule in a total of 22 steps with a 2.2% overall yield.

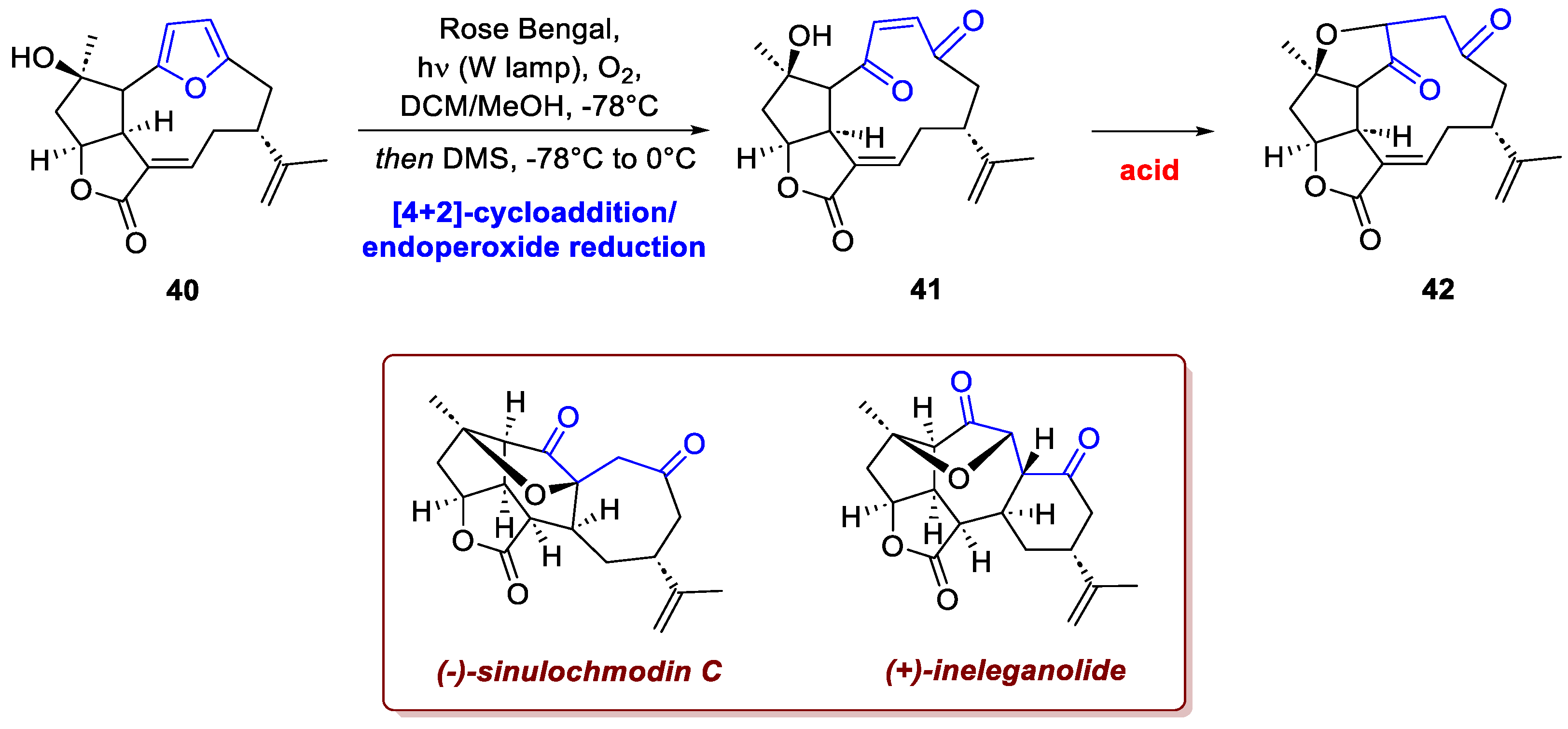

A similar strategy can be observed in Tuccinardi and Wood's total synthesis of the polycyclic nor-furanocembranoids (+)-ineleganolide and (-)-sinulochmodin C [

25], challenging structures that feature seven contiguous stereocenters on a pentacyclic core. The synthesis built the key macrocyclic precursor

40, with the correct stereochemistry, from simple starting materials, subsequently the furan moiety was smoothly oxidized using Rose Bengal (

Scheme 15). The resulting endoperoxide was reduced in situ to the ene-dione

41, which then rearranged under acidic conditions to the keto-tetrahydrofuran

42. The synthesis was completed by a final transannular Michael reaction, which delivered a mixture of the two natural products. The entire 20-step sequence concluded with an approximate 1% yield.

2.4. Miscellaneous Reactions

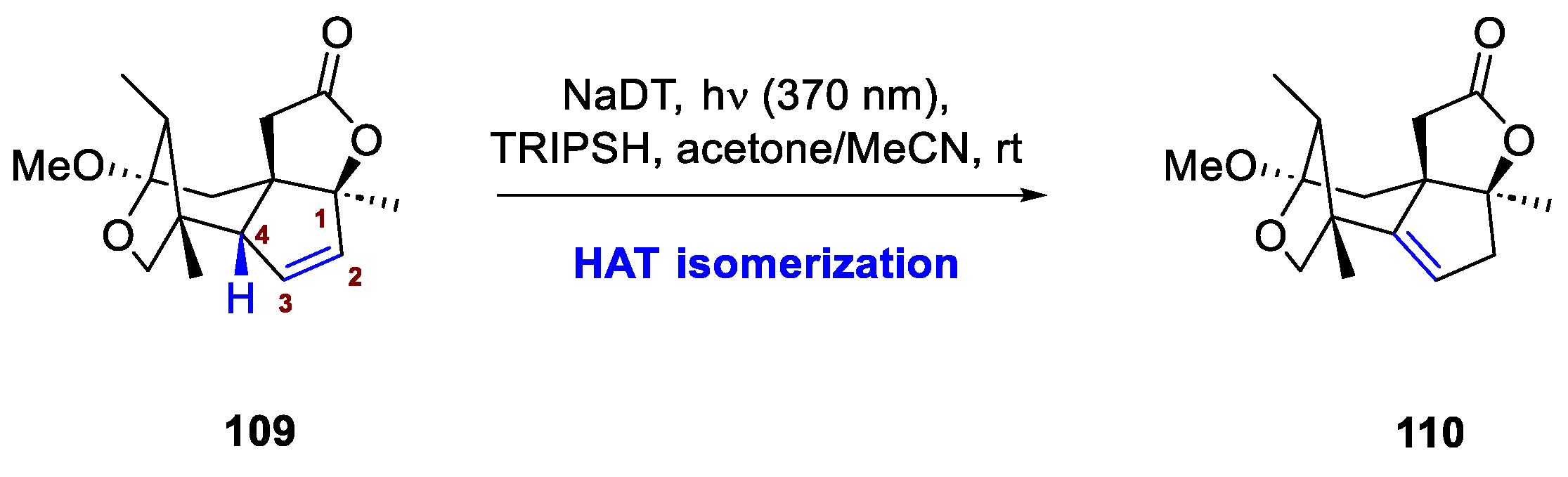

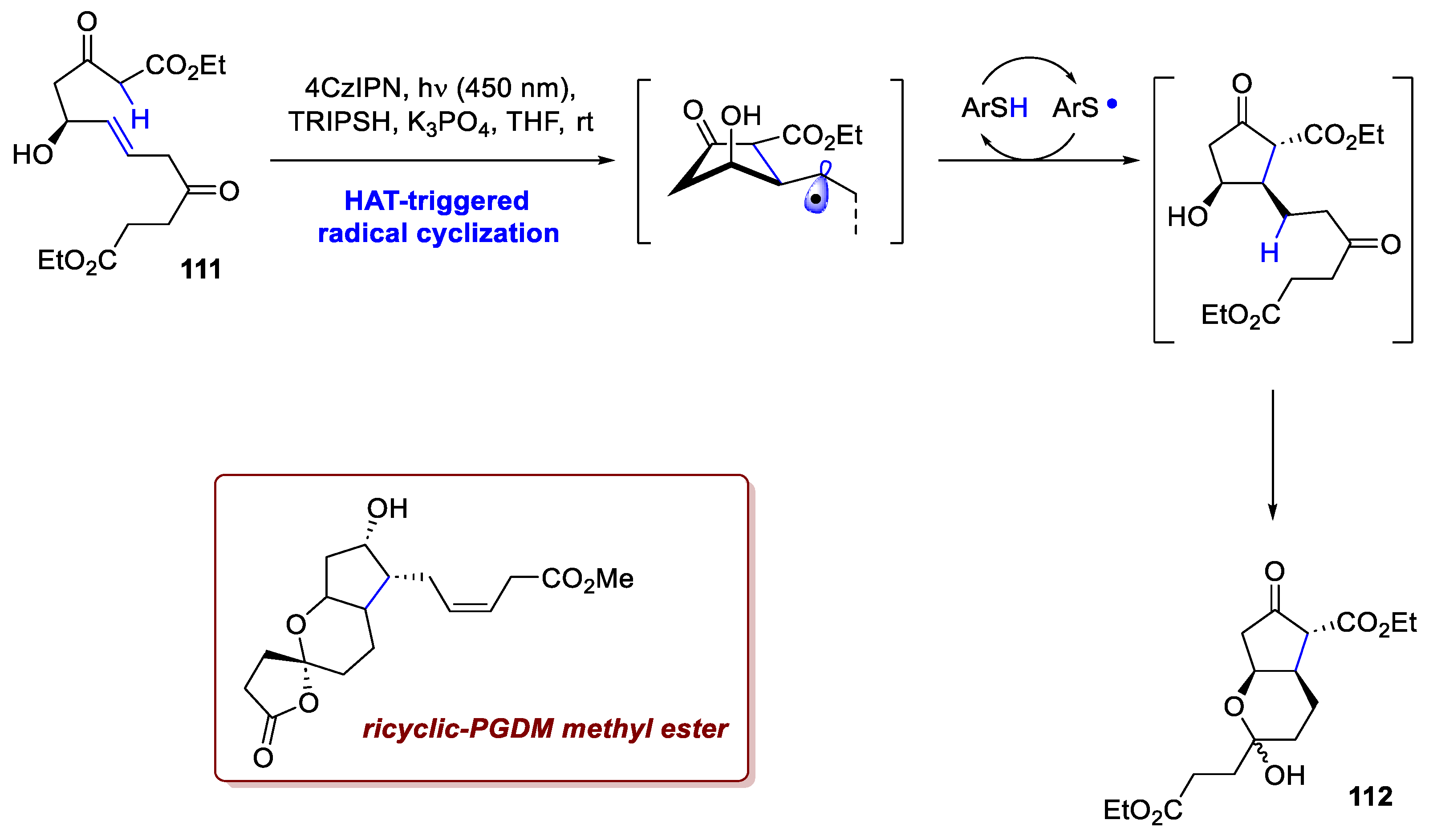

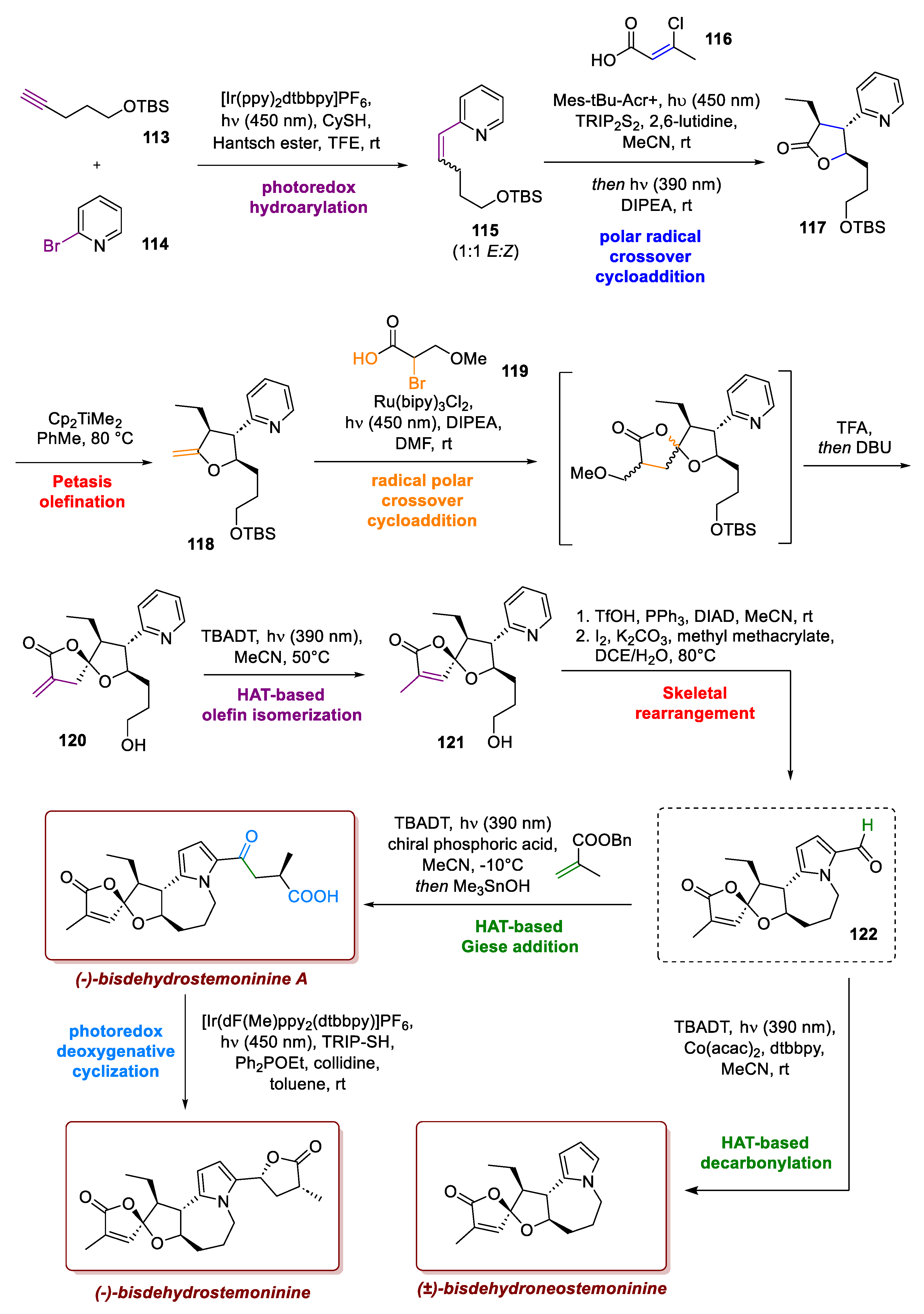

As emphasized in the introduction, the use of light to build rings within complex molecular structures often represents a key step in the total synthesis of natural products. Beyond the cycloadditions discussed above, several other cyclization strategies have been ingeniously employed for this purpose. In general, photocatalyzed HAT- and XAT-based methodologies frequently involve radical cyclization processes and the most notable recent examples are discussed in detail in the corresponding section.

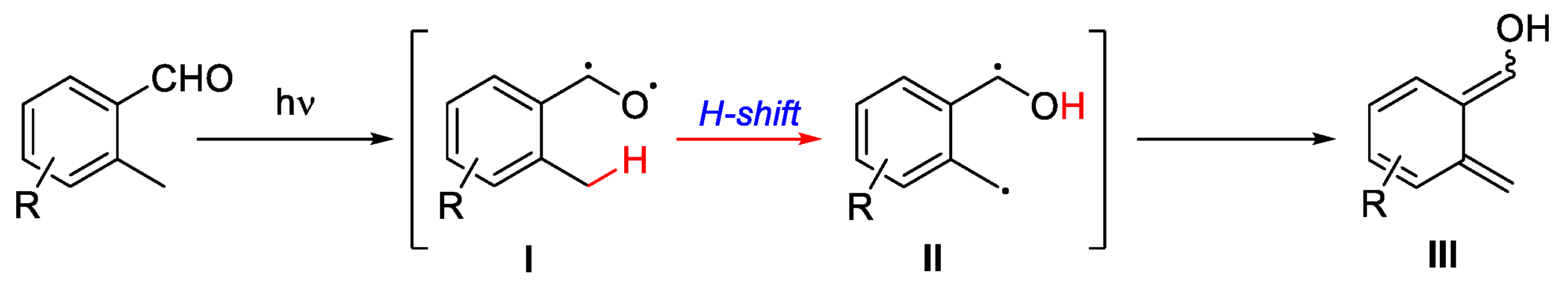

Other processes involving the direct excitation of a reagent, such as the photoenolization/Diels–Alder (PEDA) sequence, also represent fundamental methods that proceed through a cyclization step. The Diels–Alder reaction is a cornerstone of organic synthesis, enabling the stereospecific and regioselective construction of six-membered carbocycles through a concerted [4+2]-cycloaddition under thermal condition. If it is combined with light activation, its scope can be elegantly extended. In the PEDA sequence, photoexcitation of an aromatic carbonyl generates a ketyl diradical

I, this intermediate can undergo a 1,6-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from an ortho-aliphatic C–H bond delivering

II and, after subsequent electronic rearrangement, a corresponding enol

III is produced. So, this photoenolization leads to the generation of an intermediate that can then participate in different cyclizations, such as a DA reaction (

Scheme 16).

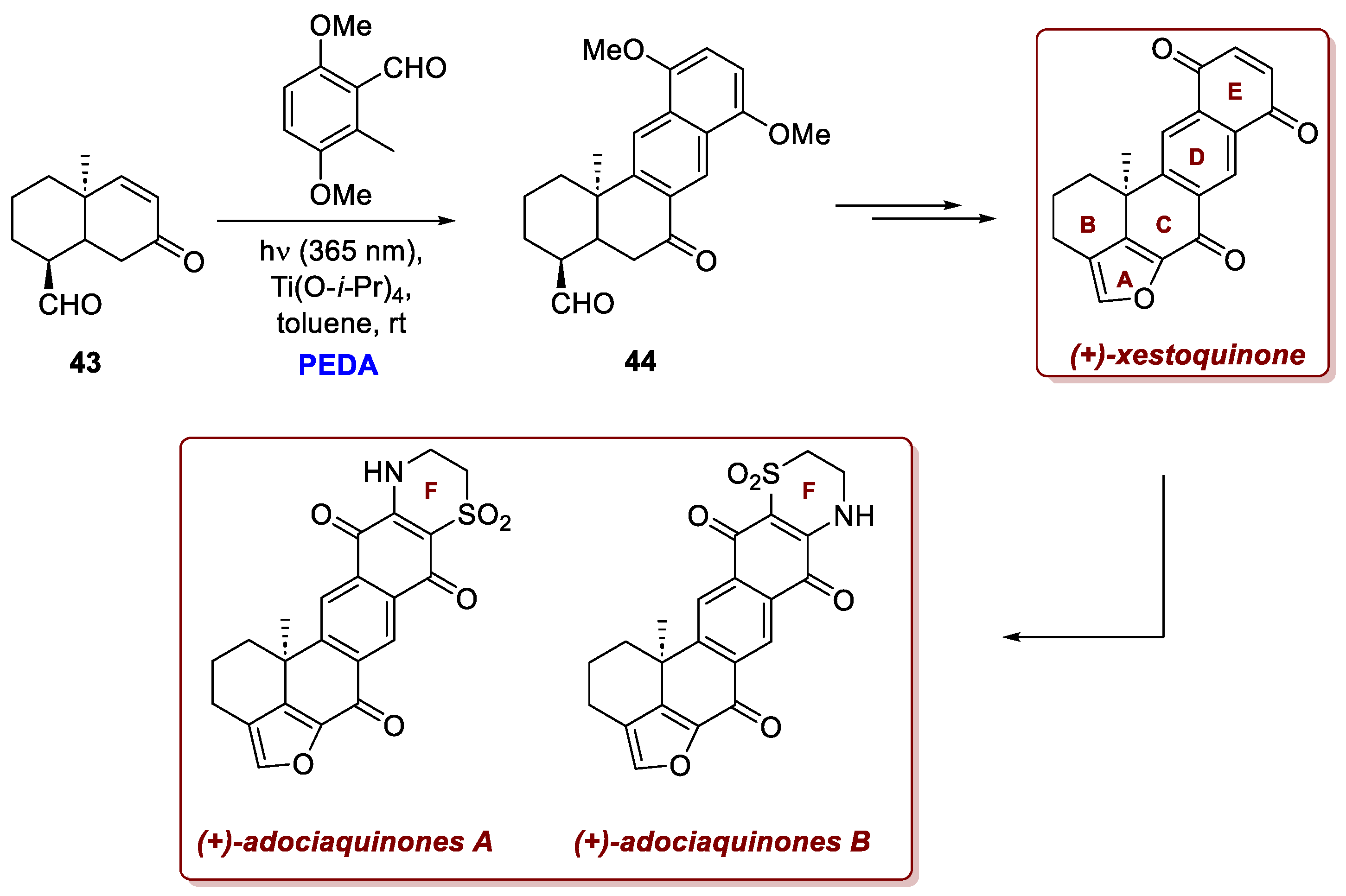

Several examples of its use in the total synthesis of natural products have been reported in the literature, with a recent notable case described in the work of Lu

et al. on the asymmetric total syntheses of (+)-xestoquinone and (+)-adociaquinones A and B complex natural products from

Xestospongia sponges [

26]. These compounds feature a pentacyclic fused core with an additional F ring for adociaquinones. Following a desymmetric intramolecular Michael addition catalyzed by an organocatalyst, the [

6,

6]-bicyclic decalin B–C scaffold

43 bearing an all-carbon quaternary centre at C6 was successfully constructed. Subsequently, formation of the naphthalene diol D–E framework was achieved via a Ti(O-

i-Pr)₄-promoted PEDA sequence, which enabled furan ring formation through a cyclization–oxidation cascade (

Scheme 17). The titanium catalyst was essential, likely stabilizing a chelated transition state that favoured an

endo-selective [4+2]-cycloaddition and promoted dehydration to yield enone

44 with excellent diastereoselectivity. Subsequent transformations furnished (+)-xestoquinone and, through a late-stage cyclization, (+)-adociaquinones A and B in seven steps from the corresponding aldehyde.

The same research group also reported the total syntheses of several hasubanan alkaloids, employing a related PEDA sequence that proceeded intramolecularly [

27]. The hasubanan alkaloids constitute a family of biogenetically related natural products characterized by a tricyclic aza[4.4.3]propellane core, primarily isolated from

Stephania species used in traditional Chinese medicine. Over forty members of this family have been identified, displaying diverse biological activities, including antiviral, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic effects, making them promising targets for medicinal research. In this work, the authors proposed a synthetic route to periglaucines A–C,

N,O-dimethyloxostephine, and oxostephabenine. These molecules represent a subgroup of hasubanan alkaloids, characterized by a higher degree of oxidation and a tetrahydrofuran ring formed via acetalization, along with a densely functionalized and highly oxidised C ring bearing three contiguous quaternary centres (C8, C13, and C14). The PEDA sequence proved to be fundamental for constructing the highly functionalized tricyclic core skeleton bearing a quaternary centre. As described above, the aldehyde underwent rapid photolysis to generate a tetrasubstituted hydroxy-

o-quinodimethane intermediate. Upon chelation with the titanium catalyst, this intermediate undergoes the desired intramolecular [4+2]-cycloaddition with the unsaturated ester moiety, effectively constructing the B and C rings of the hasubanan core (

Scheme 18). The use of (

S)-TADDOL as a chiral ligand for the metal centre established a stereochemically defined environment, enabling smooth reaction progress and affording exclusively the

endo-cycloadduct.

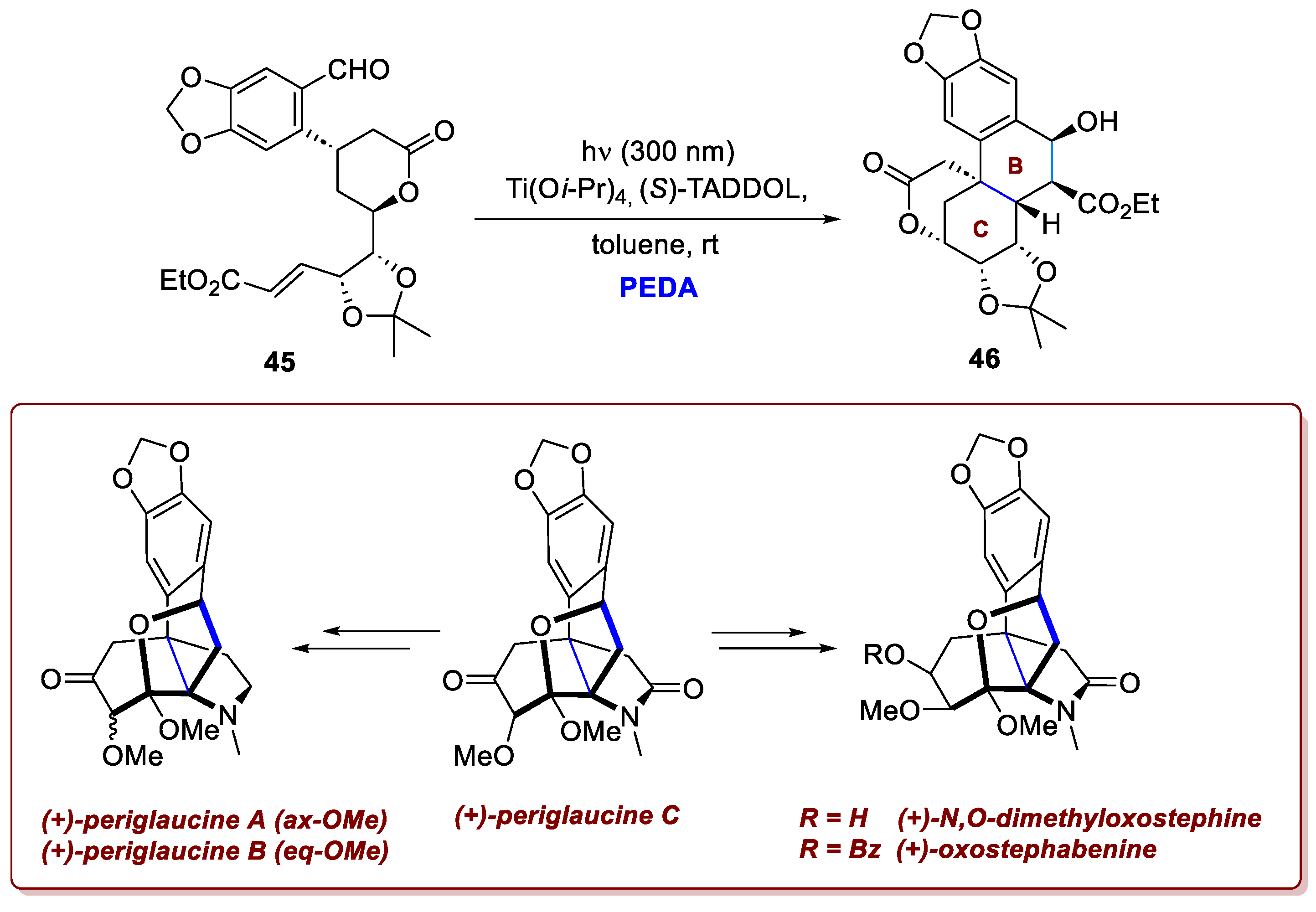

Another fundamental reaction in this field is the Norrish–Yang cyclization, which was masterfully exploited by Zheng

et al. [

28]. The Norrish–Yang cyclization is a photochemical ring closure process wherein a light-activated carbonyl functional group abstracts a hydrogen atom from within the same molecule, creating a 1,4-diradical intermediate. This unstable specie cyclizes to form cycloalkanols. Due to its capacity to introduce functionality into typically unreactive C-H bonds, this transformation has garnered substantial interest within the field of synthetic chemistry, finding wide applicability, notably in the construction of complex natural products. Nevertheless, it should be noted that achieving stereochemical control in the Norrish–Yang reaction often remains challenging, as the coupling of the diradical intermediates typically affords mixtures of both

syn- and

anti-products. Consequently, the attainment of high diastereoselectivity represents a major hurdle to the broader synthetic application of this transformation. Significant improvements have been realized by controlling the conformation of the diradical intermediate through strategies such as intramolecular hydrogen bonding, steric modulation by adjacent substituents, encapsulation within supramolecular hosts, and exploitation of solid-state crystal-packing effects. Zheng and colleagues studied immunosuppressive plant sesterterpenoids and discovered the gracilisoids, an extremely rare new family of natural products. They isolated these compounds from the ethnomedicinal Lamiaceae plant

Eurysolen gracilis. The family includes the known gracilisoids A–E and four new compounds, gracilisoids F–I. Gracilisoid A is a unique monocarbocyclic sesterterpenoid, while the others feature two new types of bicyclo[3.2.0]heptane carbon skeletons, each with six neighboring stereogenic centers. The team used (-)-citronellal as a starting material and a bioinspired approach for the synthesis. The authors proposed gracilisoid A (

47) as the biosynthetic precursor to gracilisoid F and gracilisoid H (

Scheme 19). The crucial step involved an α-diketone-based Norrish–Yang photocyclization followed by an α-hydroxy ketone rearrangement. They readily performed this transformation by irradiating gracilisoid A with a compact fluorescent lamp under oxygen-free conditions. Treating the resulting crude products with silica gel yielded the desired products. This result suggests a radical Norrish–Yang photocyclization: light excites the α-diketone in

47, creating a 1,2-biradical intermediate that abstracts respectively the C10 and C7 hydrogen atoms (respectively) to form the corresponding 1,4-biradicals. These biradicals then form C–C bonds, stereoselectively producing the bicyclic intermediates

48 and

49 while minimizing steric clash. Intermediates

48 and

49 then undergo an α-hydroxy ketone rearrangement on silica gel (mildly acidic), which relieves ring strain and yields the target bicyclo[3.2.0]heptane skeletons. Further photochemical oxidation steps completed the synthesis of the entire gracilisoid family (A-I).

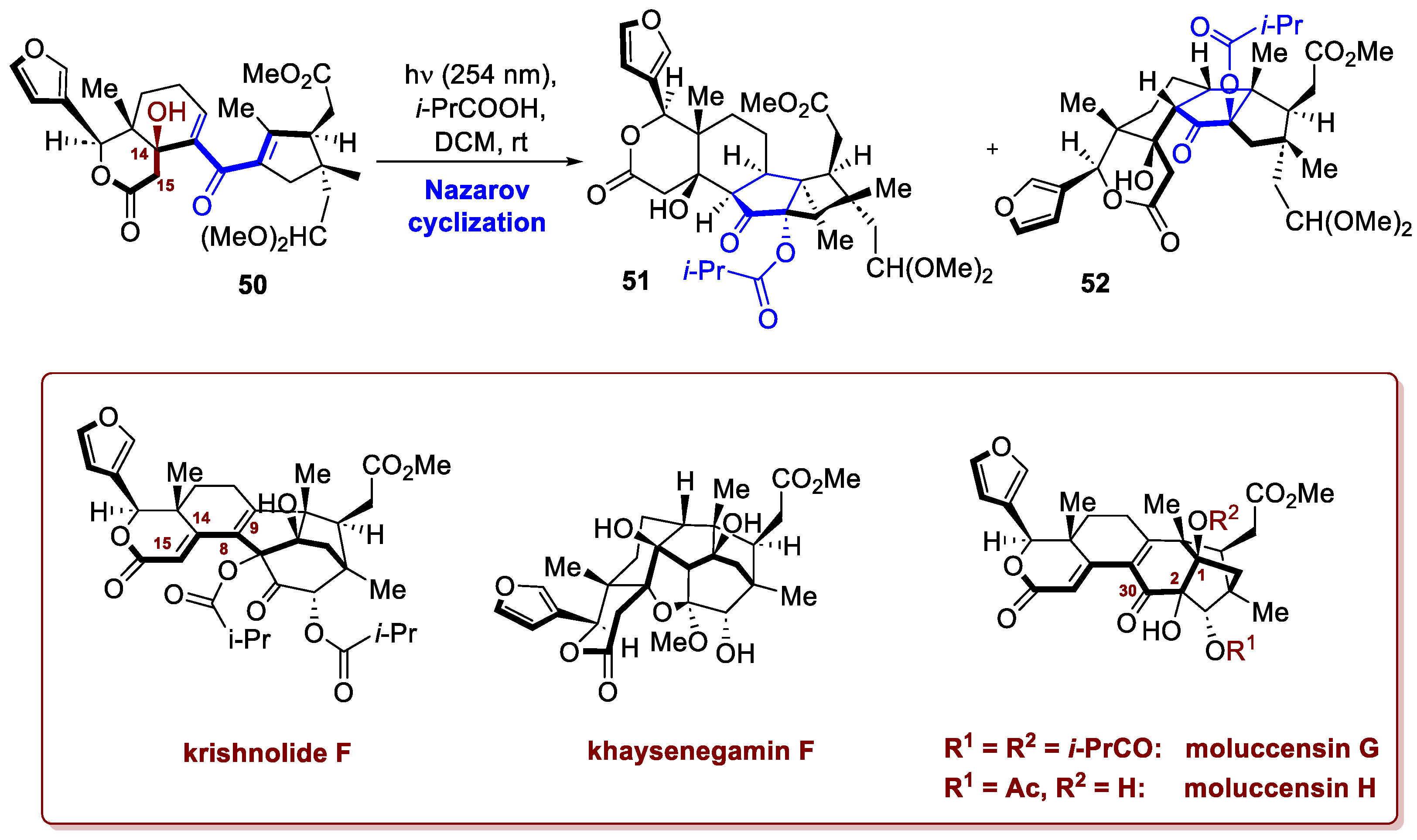

Another remarkable reaction is the Nazarov cyclization, a 4π-conrotatory electrocyclization, which stereospecifically forms functionalized cyclopentanones, structural motifs commonly found in natural products. It must be reminded that to design an efficient cyclization, it is useful to consider the reaction as a two-stage process: the first stage involves the 4π-electrocyclization forming an allylic cation, and the second stage concerns the fate of this cationic intermediate. As highlighted by Frontier and Hernandez [

29], fully understanding the individual steps of the process is crucial for enhancing reactivity and precisely controlling selectivity—an aspect of central importance in total synthesis. A modern emblematic example of its exploitation in natural product synthesis is reported by Rao

et al. [

30]. In this specific case they exploited a torquoselective interrupted Nazarov reaction to obtain the divergent total synthesis of two phragmalin (moluccensins G and H) and two khayanolide-type (krishnolide F and khayseneganin F) limonoids. After inconclusive attempts with Lewis acid–mediated Nazarov cyclization, a milder photochemical activation proved to be the most suitable approach. As shown in

Scheme 20, starting from the dienone

50 and irradiating at 254 nm in the presence of

i-PrCO

2H, the Nazarov cyclization was triggered, providing a 4.8:1 mixture of the two isomers:

51 (the desired one) and

52 in 75% combined yield. The tertiary alcohol at C14 proved to be essential to avoid photoenolization followed by a 6π-electrocyclization and diene isomerization, which would lead to an undesired by-product (not shown). It can therefore be stated that robust methodology has been establish, by integrating a torque-selective interrupted Nazarov cyclization with a Liebeskind-Srogl coupling, a benzoin condensation, and bidirectional acyloin rearrangements. This strategic combination significantly simplifies the synthetic design. Furthermore, this developed approach offers valuable additional perspectives on the biosynthetic connections between these two separate molecular skeletons.