1. Introduction

Research into storage materials, particularly metal hydrides, has attracted the attention of scientists around the world in recent years. The search for alternative energy sources has been prompted by scientific groups’ predictions about the limited availability of traditional energy sources. The use of hydrogen as an energy source is the most promising due to its high energy density, widespread availability, and the absence of harmful emissions during its use, extraction, and production [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Hydrogen can be used in the form of gas (low gravimetric density and high pressure), liquid (strict adherence to temperature conditions) and in a chemically bound state. The latter storage method meets most of the properties of the most effective hydrogen storage material, as defined by the Ministry of Hydrogen Energy.

High gravimetric density, acceptable operating temperatures, fast sorption and desorption kinetics are characteristics inherent to solid storage materials. Studying the mechanisms, establishing patterns and improving the characteristics of hydrogen interaction with these materials is one of the main challenges in this field. Various research groups around the world [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] have studied metal hydrides, carbon nanotubes, zeolites, intermetallics, and other types of metals. However, the diversity of the materials studied and the different approaches used do not allow for a complete explanation of the patterns of behavior of these materials. This was the basis for this study – comparing experimental data with theoretical material for a more complete understanding of the processes involved.

Research on carbon nanomaterials [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] has established their particular effectiveness on a par with MOFs (metal-organic framework structures) [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], nanorods, and zeolites [

36,

37,

38]. Such materials allow certain characteristics of effective storage devices to be achieved at an acceptable level. They have low density, high specific surface area, and high reproducibility. However, their synthesis is expensive and labor-intensive.

Further, scientists’ attention was drawn to the study of metal hydrides, one of the most prominent examples of which is LaNi₅ [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Despite its low hydrogen content by mass (about 1.2-1.4 wt. %), it has excellent cyclic stability at room temperature. Since it is a rare-earth compound with high density, its use is limited by its high cost. For this reason, one of the most studied metal hydrides in recent decades is magnesium hydride. Its main advantages are high gravimetric density in terms of hydrogen (7.66 wt. %), low density (1.738 g/cm³), abundance in the Earth’s crust, and low cost [

48,

49,

50]. At the same time, it has a sufficiently high stability of hydrogen-metal bonds, as a result of which it has a high hydrogen release temperature of 400 °C [

20,

51,

52]. In view of this fact, a large number of studies are aimed at improving its thermodynamic characteristics. This can be achieved by various methods, such as the use of transition metals and their oxides, varying the synthesis parameters, reducing the dispersion of materials, adding catalysts, and so on [

53,

54,

55,

56].

The large amount of research has been directed towards investigating the effect of nickel addition on reducing the desorption temperature. The authors of such studies come to the same conclusions that the formation of the Mg₂Ni phase, which has a high affinity for hydrogen, allows the formation of the hydride phase at lower energies. The mechanism is described by the fact that this phase is acts like a “hydrogen pump” that creates local diffusing pathways in the crystal lattice of the material. The resulting Mg₂NiH₄ phase is in addition easily dissociated due to the same effects observed in our previous studies [

2,

5].

The work of authors M. Polanski et. al [

57] demonstrates rather good cyclic stability of a composite based on magnesium hydride and chromium oxide (Cr₂O₃) at 325 °C. The authors present the results of 150 hydrogenation cycles during which the capacity of the material decreases from 5.2 to 4.6 wt. %. In a similar study M. Polanski, J. Bystrzycki [

58] studied the effects of adding different metal oxides on the hydrogen absorption properties of materials. One of the main results was that the addition of chromium oxide powder significantly accelerates the reaction rate of material interaction with hydrogen. This applies to both the sorption and desorption processes. About 6 wt. % of hydrogen was desorbed in 5 minutes at a temperature of 325 °C and a pressure of 1 atm. The study of the same chromium oxide powder by the authors Pukazhselvan et.al. [

59] demonstrates a positive effect both in decreasing the desorption temperature and accelerating the reaction kinetics. Several studies on nickel [

60,

61,

62,

63] demonstrate a positive effect in reducing the temperature of hydrogen desorption from the material. As mentioned above, this is due to the formation of a special phase, which acts like a “hydrogen pump” and allows the formation of hydride phases at much lower energies.

The use of various catalysts to improve the properties of magnesium hydride has been discussed in a number of scientific studies. However, our research group decided to establish patterns and explain the mechanisms of such behavior in correlation between experimental and theoretical data. The fundamental novelty of this scientific work is the study of the influence of nanoscale additives produced by the method of electrical explosion of wires as catalysts for reducing the operating temperatures of magnesium hydride. A deeper understanding of these processes and a comprehensive approach to solving current issues will bring us closer to the development of the most effective storage materials for use as mobile supplies for hydrogen storage and transport.

Thus, nickel-chromium powder produced by the electrical explosion of wires (EEW) method leads to improve the characteristics of hydrogen interaction with the material. The hydrogen storage properties of the composite were determined to demonstrate the influence of nickel-chromium nanoparticles on the magnesium-hydrogen interaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Preparation

The used powder MPF-4 (Russia) has a purity of 99.2% and a particle size from 50 to 300 microns. The size of the nickel-chromium powder has nanoscale particles up to 100 nm. The initial magnesium hydride and composites were prepared and studied using the automated Gas Reaction Automated Machine (GRAM50) complex developed at the Department of Experimental Physics of Tomsk Polytechnic University. Before the hydrogenation process, magnesium powder was pre-activated in the planetary ball mill AGO-2 (Russia, Novosibirsk) at a rotation speed of 900 rpm and a total operating time of 120 minutes. Next, the activated powder was subjected to a hydrogenation process at a temperature of 663 K and a pressure of 30 atmospheres for 300 minutes. Mechanical synthesis was carried out using a planetary ball mill AGO-2. Such experimental parameters are based on previous studies by our and similar scientific groups and are optimal for this process. The amount of nanoscale nickel-chromium powder added was 20 wt. %. The parameters of mechanical synthesis were chosen the same as during the activation of the initial magnesium metal powder. However, the ratio of the mass of the balls to the powder was not 10:1, but 20:1. All procedures for loading and unloading samples were carried out using a SPEKS GB02M glove box in an inert argon atmosphere. Activation and synthesis were carried out in an inert atmosphere.

2.2. Analysis and Characterization

The hydrogen concentration was measured by melting samples in an inert gas atmosphere using a RHEN602 hydrogen analyzer (LECO Corporation, USA).

The microstructure of the composite was studied using a TESCAN VEGA 3 SBU scanning electron microscope (Tescan Orsay Holding a.s., Czech Republic). The elemental composition of the composite was analyzed by the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy on an X-Max 50 X-ray spectrometer (Oxford Instruments plc, UK).

The crystal structure of the samples was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) in the scanning range (5–80)° using XRD-7000S (Shimadzu, Japan). The diffractometer operated in the Bragg-Brentano configuration with a Cu Kα anode (λ=0.154 nm) operating at 40 kV and 30 mA.

Low-temperature sorption of N₂ was used to characterize the textural properties of samples at cryogenic temperature using a 3Flex automated gas adsorption analyzer (Micromeritics Instruments Corporation, USA). The values of the surface area were calculated by linearization using the coordinates of the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation in the range of relative pressure from 0.05 to 0.3. To plot the mesopore size distribution, the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method was used with the analysis of the isotherm desorption branch. The micropore distribution was calculated using the Horvath-Kavazoe method. The samples were degassed in vacuum at a temperature of 573 K for 10 hours before the measurements.

The method of temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) of hydrogen at heating rates of 2, 4, 6 and 8℃/min to a temperature of 723 K in the experimental chamber with simultaneous data collection of desorption spectra using a quadrupole mass spectrometer RGA100 (Stanford Research Systems, USA) was used to estimate the state of hydrogen in the material. Each of the analyses performed was carried out more than five times. The experimental data described in the article are average values for the materials studied. The data presented in this paper is the average result from the data set obtained. Each measurement was taken at least five times to ensure the most accurate result.

2.3. Methods and Calculation Details

Within the framework of the electron density functional theory (DFT) using the method of projected augmented plane waves implemented in the ABINIT program package [

64,

65], calculations of hydrogen binding energies on the pristine α-MgH₂ (110) surface as well as in the presence of adsorbed Cr and Ni atoms have been performed. The generalized gradient approximation in the form of Perdue, Burke, and Ernzerhof [

66] was employed to describe exchange and correlation effects. A four-layer Mg₄₈H₉₆ film in the 2 × 3 structure (supercell dimensions are 12.72 × 9.01 Å) was used to study the interaction of Cr and Ni atoms with the (110) surface of α-MgH₂ with a TiO₂-like structure (

Figure 1). As shown in

Figure 1b, each atomic layer of the computational supercell contains 12 magnesium and 24 hydrogen atoms, which ensures a stoichiometric system. The vacuum layer separating the Mg₄₈H₉₆ film systems in adjacent computational cells was set to approximately 15 Å. This vacuum layer allows us to prevent the interactions between the adsorbed Cr and Ni atoms and the surface Mg and H atoms in neighboring supercells. In this work, 6 non-equivalent adsorption positions of Ni and Cr atoms on the (110) MgH₂ surface were considered.

Figure 2 shows the top view of the (110) surface, illustrating the non-equivalent positions of H atoms and the adsorption sites of Cr and Ni atoms with the highest adsorption energies. Relaxation was considered complete when the force acting on each atom was less than 10 meV/Å. At each iteration of self-consistency, the eigenvalues of the Hamiltonian were calculated on a 6×8×1 grid of k-points generated by the Monkhorst-Pack scheme in the entire Brillouin zone of the described supercells. The cutoff energy at the wave function decomposition by the plane wave basis was 700 eV. To analyze the nature of interaction of nickel and chromium with hydrogen on the α-MgH₂ (110) surface, the valence electron distribution was studied and the Bader charge calculations [

67] were performed.

The hydrogen binding energy

Eb on the (110) surface of α-MgH₂ was calculated using the following expression:

where

is the total energy of the magnesium hydride supercell containing

n Mg atoms and adsorbed

x Ni atoms and

y Cr atoms (in the computational cell,

x and

y take values of 0 or 1).

is the total energy of the magnesium hydride supercell from which one of the surface H atoms has been removed,

is the total energy of the hydrogen molecule.

The value of the Eb should be interpreted as an indication of how hydrogen atoms promote hydrogen release. Positive values of Eb indicate that the removal of the hydrogen atom from the system requires energy consumption, i.e., such atoms are strongly bound within the surface. Negative values, in contrast, imply that the removal of the hydrogen atom is thermodynamically favorable. Nevertheless, even in the case of negative Eb, hydrogen release does not necessarily proceed spontaneously, as it requires overcoming significant activation energy. Thus, the value of Eb reflects the strength of hydrogen retention on the surface: the smaller its value, the weaker the interaction. In particular, hydrogen atoms with negative Eb are the most prone to desorption and are likely to be released first under external perturbations.

In order to verify the computational parameters, the influence of k-points and cutoff energy on the computational accuracy was investigated. Thus, the change in the hydrogen binding energy for the system studied did not exceed the value of 1 meV with the increasing of the k-point mesh grid from 6×8×1 to 8×10×1 and cutoff energy from 700 eV to 900 eV. This change is insignificant and allows us to claim about an accurate description of interaction between additives with hydrogen atoms on the MgH₂ (110) surface.

3. Results

3.1. Composite Characterization

Figure 3 shows the XRD results of ball-milled MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr. The main components of the ball-milled MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr sample were Mg, MgH₂, Ni-Cr.

Diffraction analysis of the materials made it possible to determine the composition and did not reveal the presence of extraneous phases. The magnesium hydride lattice has a tetragonal rutile-type structure, the main phase in the prepared magnesium hydride was the

β-MgH₂ phase. The phases found in the composite material are HCP Mg,

β-MgH₂, CrNi with a BCC lattice for chromium and FCC lattice for nickel. Characteristic peaks for CrNi are observed at diffraction angles: 44.5°, 51.8°, 75.4°. In addition, peaks broadening is observed in the composite, which is due to the accumulation of defects during the milling process. To clarify the structural characteristics of the crystal lattice of the materials under study,

Table 1 below presents the calculated microstrains values using PowderCell24 software.

Based on the results of microstrains analysis in the material from

Table 1, it can be established that the amount of internal strains in the crystal lattice increases almost by a factor of 4. The data obtained on changes in the crystalline structure of the material indicate a more developed defect structure and a decrease in the dispersibility of the ground materials. All this contributes to easier bonding of hydrogen with magnesium atoms, as well as their permeation/ release into/from the bulk. During the analysis of diffraction curves, no alloy compounds between magnesium and Ni-Cr were detected. The Cr

0.4Ni

0.6 phase is clearly visible in the composite material. It is a direct factor influencing the change in the discussed properties of magnesium. A comprehensive approach combining experimental and theoretical data allows us to establish the nature of the mechanism of this effect. In our previous studies [

2,

5], we found a significant influence on the change in hydrogen desorption kinetics, which was partly related to the formation of the Mg₂NiH₄ phase. The phase acted as a ‘hydrogen pump’ [

2,

5] – nickel catalyzed the hydrogen sorption properties of Mg/MgH₂. The principle of this mechanism is described in more detail in another study and is also presumably one of the fundamental principles for the MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite discussed in this study.

Figure 4 shows microphotographs of magnesium hydride and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite obtained using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), as well as histograms of particle size distribution and element distribution maps.

From the images presented above, most of the magnesium hydride particles are agglomerates with an average size of about (50 ± 12.5) μm, with the largest particles reaching about 200 μm in size. In

Figure 4 (f), the particle size is reduced significantly to (0.1 ± 0.0125) µm, which is due to the milling in a planetary mill and the co-milling of magnesium powder with balls and nanoscale nickel-chromium powder. This reduction in size improves the hydrogen interaction characteristics of the material.

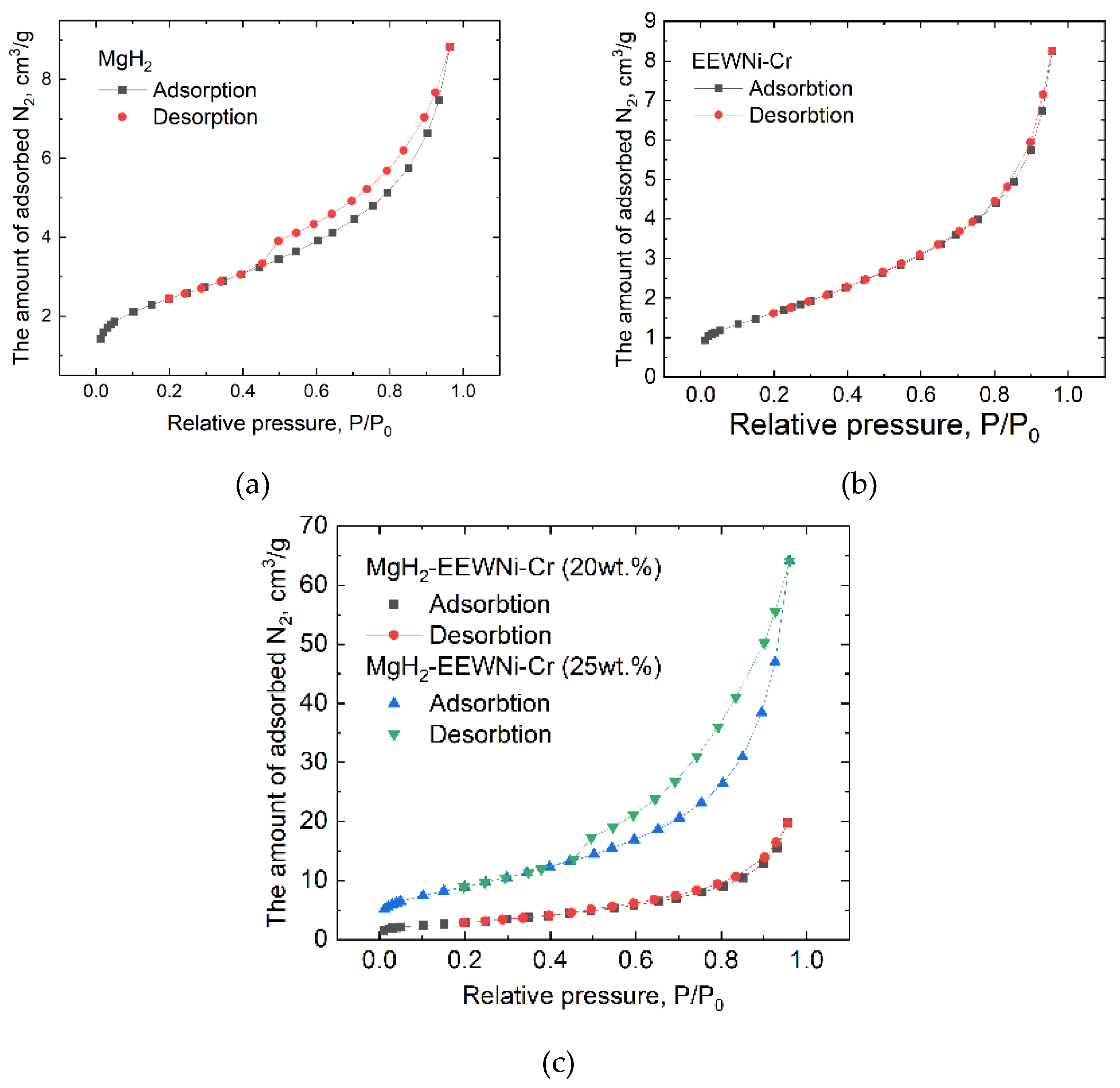

The nitrogen absorption method (BET method) allowed us to study the textural properties of the materials of this work. Adsorption-desorption isotherms at 573 K for magnesium hydride and composite were determined for them.

Figure 5 shows the isotherms, in which a larger hysteresis is well observed for the composite than for the original magnesium hydride. This behavior of the material is due to the increase in the interface area, thereby increasing the number of diffusing pathways in the crystalline lattice of the material. On the other hand, the main adsorption of N₂ on the adsorption isotherms for the MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite starts at a slightly lower relative pressure (

P/

P₀ ≈ 0.6). The amount of adsorbed nitrogen in the composite material is greater by tens of times. The surface area (

Table 2) for MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr is 3-5 times larger. A larger average pore diameter and pore volume in addition characterizes the material.

Thus, the co-milling of MgH₂ and EEWNi-Cr powders allows to significantly increasing BET surface area and N₂ absorption, which may be a consequence of the milling process effect, as well as the specific features of the “core-shell” structure appearance. The amount of powder used for BET analysis is usually between 0.2 and 1 g. The porosity of the materials studied is represented by the total pore volume and average pore diameter values. For composites, a significant change in material porosity can be observed, as well as in specific surface area (

Table 2).

3.2. Hydrogen Storage Properties of Composite

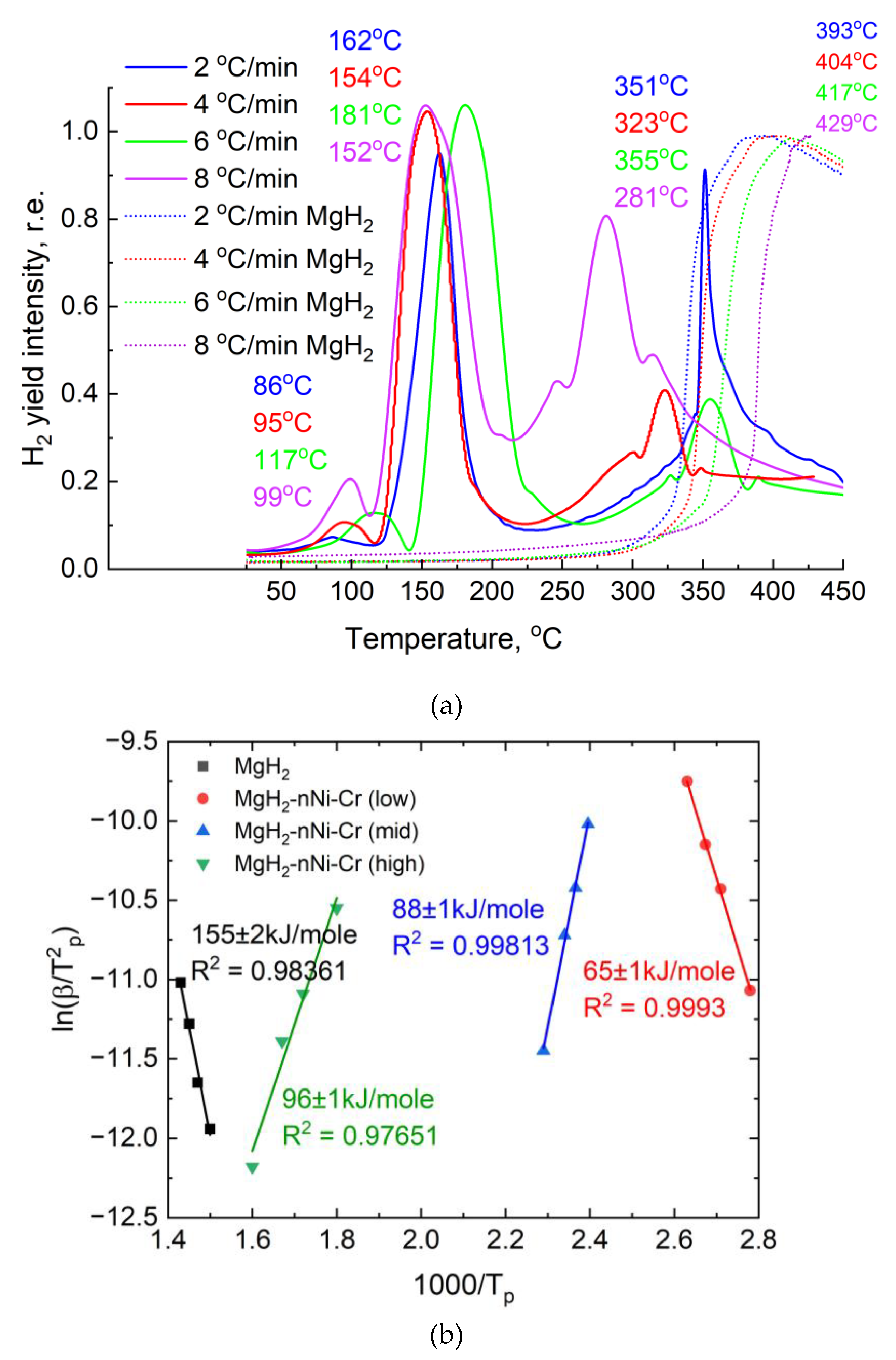

The study of temperature-programmable desorption (

Figure 6) demonstrated the positive effect of adding nickel-chromium powder. In this case, desorption process was divided into 3 stages in different temperature regions, which are further designated as low-, medium- and high-temperature regions. The dissociation of the hydride occurs in the high-temperature region, which is due to the high stability of the hydrogen bonds in magnesium. The temperature can be reduced by ball milling in a planetary ball mill. This is demonstrated by the high-temperature decomposition region of the composite (281–351 °C). This area is directly related to the decomposition of the magnesium hydride phase, the other two areas (low and medium) are related to the catalytic effect of nickel-chromium powder and the decomposition of the hydride phase of the composite material.

The Kissinger method is an overwhelmingly popular way of estimating the activation energy of thermally stimulated processes. The essence of the method is to remove these desorption curves at different heating rates (in this case – 2, 4, 6, 8℃/min), resulting in peak shifts. For the most accurate calculation of desorption activation energy using this method, a minimum of 3-5 heating rates are required, which we used in this study. It is also necessary to have a sufficiently accurate value of the heating rate of the material in relation to the values of hydrogen yield temperatures and their intensity, which is achieved by the availability of high-precision measuring and heating equipment.

We relate the three temperature regions in which hydrogen is released from the material to a complex of effects consisting of changes in the specific surface area of the material and changes in its lattice and electronic structures in the presence of a Ni-Cr catalyst:

1. We attribute the low-temperature hydrogen desorption peak at 86-117 °C mainly to surface dissociation of the hydride and the catalytic effect.

2. The hydrogen yield at 152-162 °C is also associated with the catalytic effect of the added material, but the width of the peak and its intensity suggest a bulk decomposition of the hydride phase in the material.

3. hydrogen desorption at 281-351 °C is associated with the full dissociation of the magnesium hydride phase in the composite material, which was subsequently confirmed by the results of in situ XRD in

Figure 7 below.

Similar thermodynamic effects can be observed in studies [

68,

69]. The temperature values at peaks at different heating rates are taken, a calculation is performed to construct in Arrhenius coordinates (1000/

Tp from

ln(β/T2p)) and the angular coefficient (

A) is determined, which gives the activation energy (

Ed):

here

А – angular coefficient,

R – universal gas constant,

β- heating rate,

Tp - the temperature of the peak hydrogen yield.

Table 3.

Calculation of desorption activation energy by Kissinger method.

Table 3.

Calculation of desorption activation energy by Kissinger method.

| № |

Sample |

β,

℃/min

|

TP, K |

|

,

|

A, angular coefficient |

Activation energy of desorption, kJ/mol |

| 1 |

MgH₂ |

2 |

666 |

-11.94 |

1.5 |

-15.75 |

155 ± 2 |

| 4 |

677 |

-11.65 |

1.47 |

| 6 |

690 |

-11.28 |

1.45 |

| 8 |

700 |

-11.02 |

1.43 |

| 2 (low) |

MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr |

2 |

359 |

-11.07 |

2.78 |

-10.66 |

65 ± 1 |

| 4 |

368 |

-10.43 |

2.71 |

| 6 |

390 |

-10.14 |

2.56 |

| 8 |

372 |

-9.75 |

2.68 |

| 3 (mid) |

2 |

435 |

-11.45 |

2.29 |

16.19 |

88 ± 1 |

| 4 |

427 |

-10.72 |

2.34 |

| 6 |

454 |

-10.44 |

2.20 |

| 8 |

425 |

-10.02 |

2.35 |

| 4 (high) |

2 |

624 |

-12.18 |

1.60 |

7.98 |

96 ± 1 |

| 4 |

596 |

-11.39 |

1.67 |

| 6 |

628 |

-11.09 |

1.59 |

| 8 |

554 |

-10.55 |

1.80 |

The calculated desorption activation energies for the three temperature regions were 65, 88 and 96 ± 1 kJ/mol. The strong catalytic effect of nickel-chromium powder has reduced the energy required for the decomposition of the hydride phase of the material. According to the data obtained from the RHEN602 hydrogen analyzer, the hydrogen content in magnesium hydride and composite material was 7.2 ± 0.2 and 5.2 ± 0.1 wt.%, respectively.

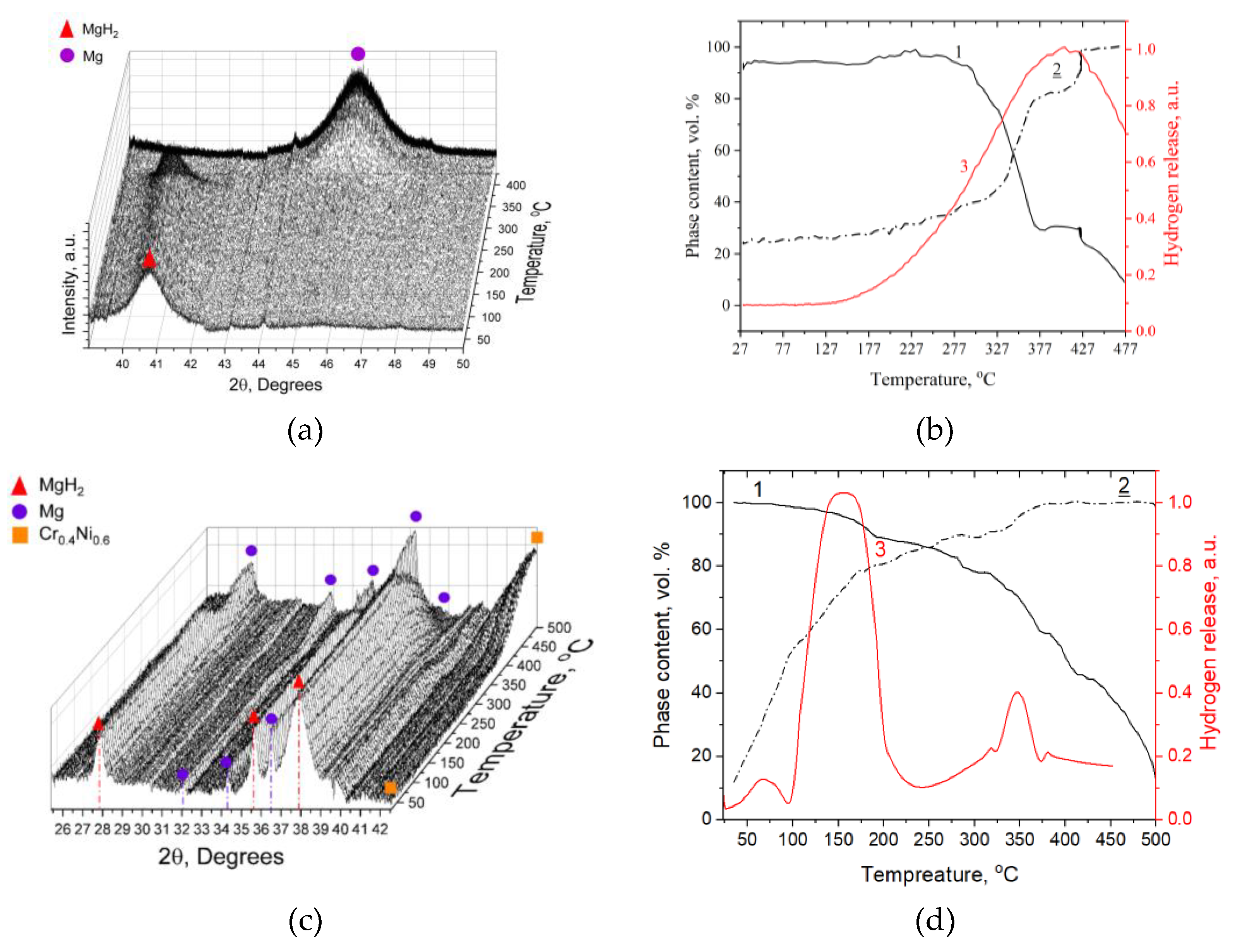

Figure 7 is an

in situ X-ray phase analysis (

in situ XRD) during step heating at a rate of 5 K/min from 25 to 500 °C with a dwell time at each step of 60 seconds (measurement time).

Figure 7a,d clearly shows the change of

β-MgH hydride phase in MgH₂. The decrease in the hydride phase is provoked by heating of the material with further dissociation of hydride phase as shown in

Figure 7b,d. In addition to the phase composition change,

Figure 7b,d also shows the thermal-stimulated desorption spectra at a heating rate of 6 K/min from 25 to 500 °C for the MgH₂ and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite (20 wt. %). The main hydrogen release occurs at a temperature maximum of 150 °C for the composite (

Figure 7d, 3

rd line), while for magnesium hydride this value is 417 °C (

Figure 7b, 3

rd line). From

Figure 7b,d, the shift of the crossing point of the phase change lines (1 and 2) during the hydrogenation/dehydrogenation process is well observed. For the initial magnesium hydride, this value is around 327 °C, while for the composite it is around 250 °C, which is presumably due to the enhancement of the thermodynamic characteristics of the material with the addition of EEWNi-Cr. It is observed that the hydride phase in the initial material starts active decomposition at a temperature around 300 °C, while for the composite a gradual decrease of the hydride phase can be observed, demonstrating a faster kinetics of hydrogen desorption from the material.

In a recent study [70], several Mg2TM-Mg2TMHn (TM = Cr and Mn) materials were synthesized and the characteristics of hydrogen interaction with the obtained materials were investigated. For the Mg3(CrMnFeCoNi)0.2Hx composite, the hydrogen capacity is 5.3 mass % with two desorption peaks: 247 and 277 °C. In [71], a magnesium hydride-based composite with 5 wt. % CrO3 added demonstrates a reversible capacity of about 5 wt% H₂ in the temperature range 250-270 °C at 5.9 atm. The results of the study [72] demonstrate a MgH₂+10wt% Cr composite capable of desorbing hydrogen at 200 °C and undergoing re-sorption at 28 °C. The material has a reversible capacity of 6.28 wt% after 20 cycles at 285 °C. The initial dehydrogenation temperature in [73] MgH₂-9 wt% CrCoNi was significantly reduced from 325 °C to 195 °C, which is 130 °C lower than that of MgH₂ without additives. The composite released 4.84 mass % H₂ at 300 °C for 5 minutes and absorbed 3.19 mass % hydrogen at 100 °C for 30 minutes (3.2 MPa). The calculated activation energy of dehydrogenation/rehydration was reduced by 45 and 55 kJ/mol. The onset temperature of dehydrogenation became 195 °C, and the material was capable of releasing 6.02% by mass of hydrogen at 300 °C for 15 minutes. The results of ABINIT calculations performed in study [74] demonstrated the properties of Mg1-x-yCrxH₂ depending on the amount of transition metal added. It was found that the alloyed material and hydrogen atoms form weak hybridization in the structure, in contrast to pure magnesium hydride, which mainly consists of strong hybridization between hydrogen and magnesium atoms.

3.3. Influence of the Ni and Cr Additives on H-Mg Bonding

Hydrogen binding energies

Eb on the (110) surface of α-MgH₂ were calculated both in the absence and in the presence of Ni and Cr adsorbates for several geometrically nonequivalent surface H sites, using equation (1). In addition, the H–Mg bond lengths

dH–Mg corresponding to these sites were computed. The results are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively.

As evidenced by the data in

Table 4, the hydrogen binding energies of all Ni/Cr-modified (110) α-MgH₂ systems are lower, reaching negative values, compared to the pristine surface. A distinctive feature of the Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr system, containing a surface Ni–Cr complex, is the emergence of a single negative hydrogen binding energy value (at H10 site) among all the Mg₄₈H₉₆, Mg₄₈H₉₆Ni, Mg₄₈H₉₆Cr, and Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr system configurations considered. A negative binding energy indicates that, for this specific hydrogen atom, formation of an H₂ molecule is energetically more favorable than remaining adsorbed on the (110) Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr surface. Consequently, such hydrogen atoms are expected to desorb significantly earlier with increasing temperature. Furthermore, adsorption of the Ni–Cr complex leads to a pronounced reduction in all hydrogen binding energies. Notably, in the Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr configuration, binding energies for the majority of surface hydrogen atoms fall below 1 eV that is not observed in any of the other systems considered, thereby positioning Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr as a uniquely reactive surface with enhanced hydrogen release propensity.

A common feature across all the systems considered is that hydrogen atoms with the lowest binding energy

Eb are located within an intermediate radial range from the adsorbate center of mass (

r1 < r < r3). At the same time, each region in

Figure 2 also contains hydrogen atoms with moderately higher binding energies (1.0–1.4 eV), comparable to those on the pristine surface. At larger distances from the adsorbates (

r > r4), the elevated hydrogen binding energies are consistent with a reduced perturbation of the surface electronic structure, as the influence of Ni and Cr becomes negligible. In contrast, the high binding energies observed for hydrogen atoms located in close proximity to the adsorbates (

r < r4) can be attributed to a spatial redistribution of valence charge density induced by the presence of Ni and Cr atoms.

The computed H–Mg bond lengths

dH–Mg (

Table 5) for hydrogen atoms at positions H1–H13 exhibit a consistent increase in the presence of Ni and Cr adsorbates. This increase is more pronounced for hydrogen atoms located near the adsorbates and becomes less significant at greater distances, indicating a distance-dependent weakening of the adsorbate-induced structural perturbation.

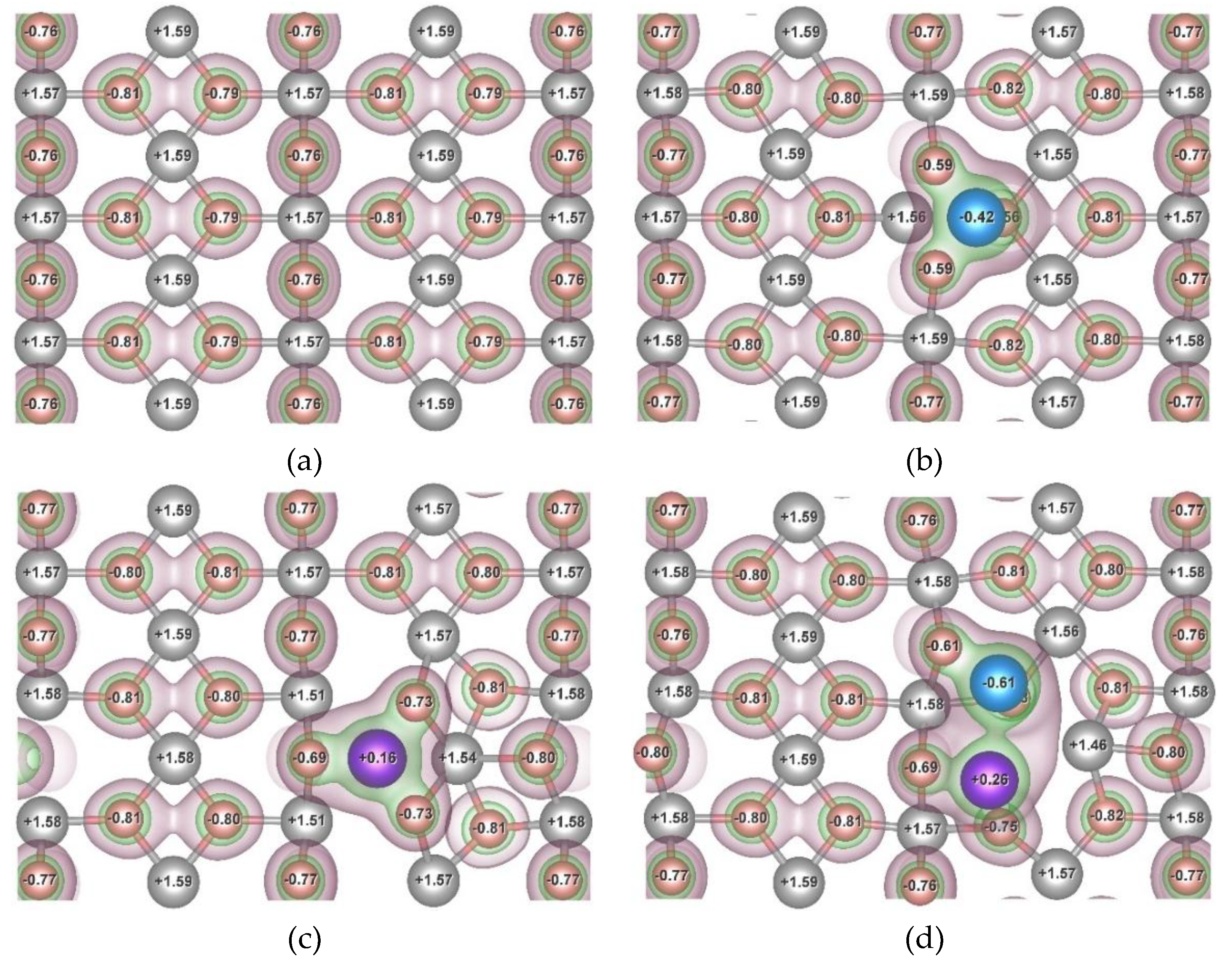

To provide insight into the origin of H–Mg bond weakening in the presence of adsorbed Ni and Cr atoms, the valence electron density distribution was analyzed for the pristine α-MgH₂ (110) surface, as well as for surfaces modified by single Ni and Cr atoms and by the Ni–Cr complex (

Figure 8). The Bader charge transfer was also calculated, it is marked by numbers in the

Figure 8. It is expressed in units of elementary charge and characterizes the amount of charge transferred to the atom during bond formation.

Bader charge transfer (Δq) analysis reveals that on the pristine (110) surface of α-MgH₂ the bonding between Mg and H atoms is predominantly ionic in character. The calculated transfer values Δq are approximately +1.6e for Mg and –0.8e for H atoms, which clearly indicates strong electron transfer from hydrogen to magnesium. This finding is consistent with the valence electron density distribution, where regions of electron density more than 0.02 e/ų are concentrated around hydrogen atoms and do not extend toward Mg atoms. The pronounced ionicity of the H–Mg interaction contributes to its high bond strength; therefore, a shift toward a more covalent character may result in a weakening of the bond.

In the Mg₄₈H₉₆NiₓCry systems, high valence electron density isosurfaces of 0.05 e/ų indicate the formation of covalent bonds between the adsorbed Ni and Cr atoms and their nearest hydrogen neighbors. The size of high-density regions around the hydrogen atoms nearest to the Ni-Cr complex (at a distance less than r1) are slightly reduced compared to the pristine surface (Figure 8a) or to the surfaces with the single Ni or Cr atom (Figure 8b,c). This size reduction and increase in H–Mg bond lengths reflect a suppression of charge localization, implying that the presence of the Ni–Cr complex noticeably decreases the ionic character of H–Mg bonds near the adsorbate atoms.

The adsorption of individual Ni or Cr atoms on the MgH₂ surface leads to the formation of predominantly covalent bonds with nearby hydrogen atoms, which in turn weakens the H–Mg interaction. As a result, the binding energy of hydrogen atoms in the vicinity of the adsorbate is reduced compared to that on the pristine MgH₂ surface. In the case of co-adsorption, Bader charge analysis shows that the charge transfer on the Ni and Cr atoms increases from –0.42

e to –0.61

e and from +0.16

e to +0.26

e, respectively. In addition, the valence electron density map (

Figure 8 d) reveals a common high-density isosurface (0.05

e/ų) between Cr and Ni, confirming the formation of a covalent Cr-Ni bond. This predominantly covalent interaction, together with a formation of Ni–H and Cr–H covalent bonds, leads to a redistribution of the valence electron density on the MgH₂ surface and a reduction in the ionic character of the H–Mg bonding. The decrease in hydrogen binding energy observed in the presence of the Ni–Cr complex is significantly more pronounced than in either single-element system. This synergistic effect is consistent with experimental observations, where co-milling of Ni-Cr nanosized powder and magnesium hydride leads to the emergence of a double low-temperature hydrogen desorption peak. Accordingly, surface hydrogen atoms with negative binding energies are expected to desorb first and correspond to the low-temperature desorption peak, whereas hydrogen atoms with positive binding energies desorb at higher temperatures and account for the second peak. After conducting a series of cyclic hydrogenation/dehydrogenation tests, it was established that the material retains practically all of its initial hydrogen capacity. Further measurements are planned in order to obtain the most complete and accurate results (

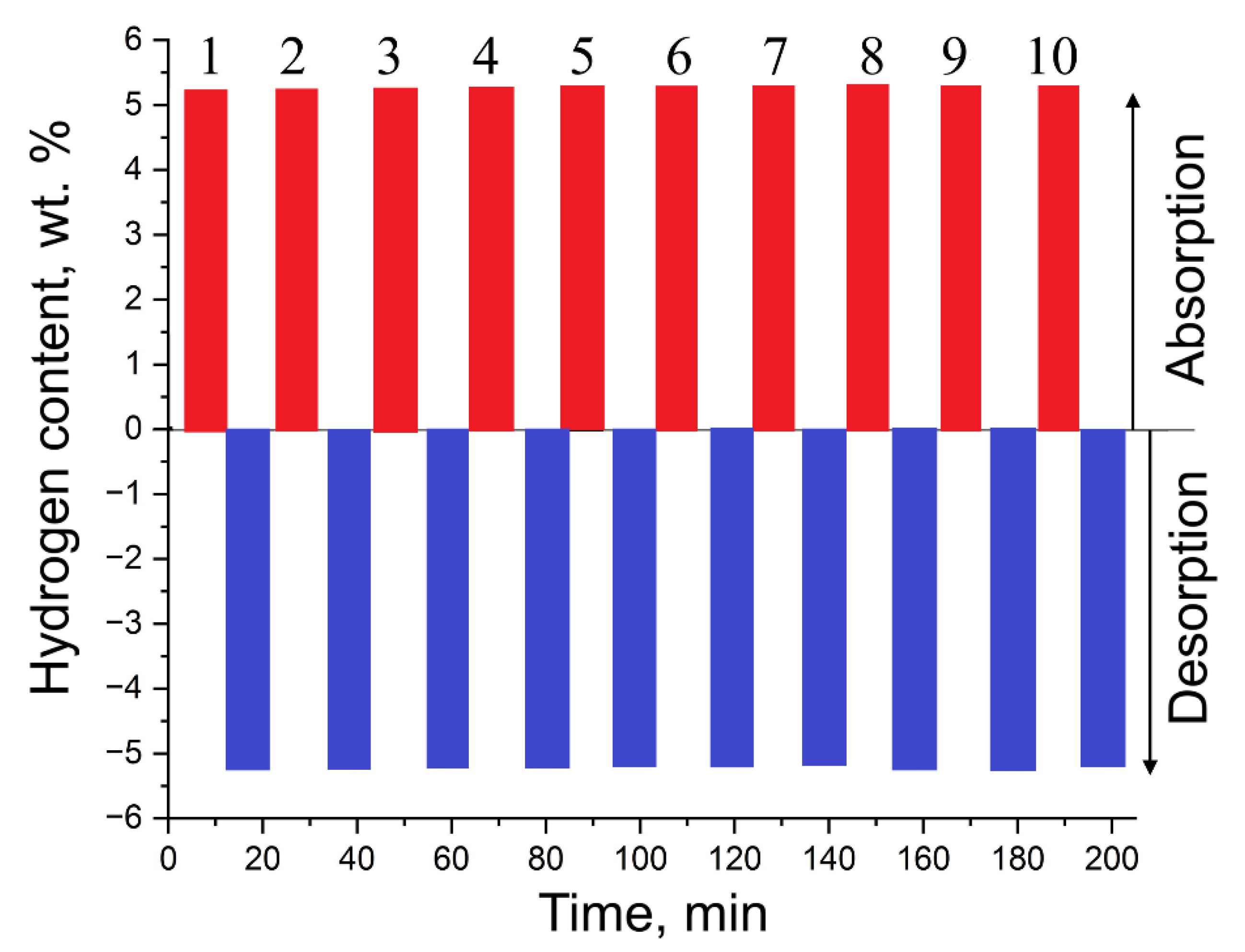

Figure 9).

In the future, we plan to conduct a series of measurements consisting of 50, 100, and 500 cycles. This will allow us to clearly determine the actual effectiveness of the material relative to others.

4. Discussion

The material based on magnesium hydride and EEWNi-Cr powder obtained in this work has potential for further study and future use in mobile hydrogen storage systems in the field of hydrogen energy. Further research will focus on developing a metal hydride cell filled with the material studied in this article. This cell will be used as a source for storing and transporting hydrogen in a bound state. This will enable hydrogen to be stored safely and efficiently for its usage as a fuel.

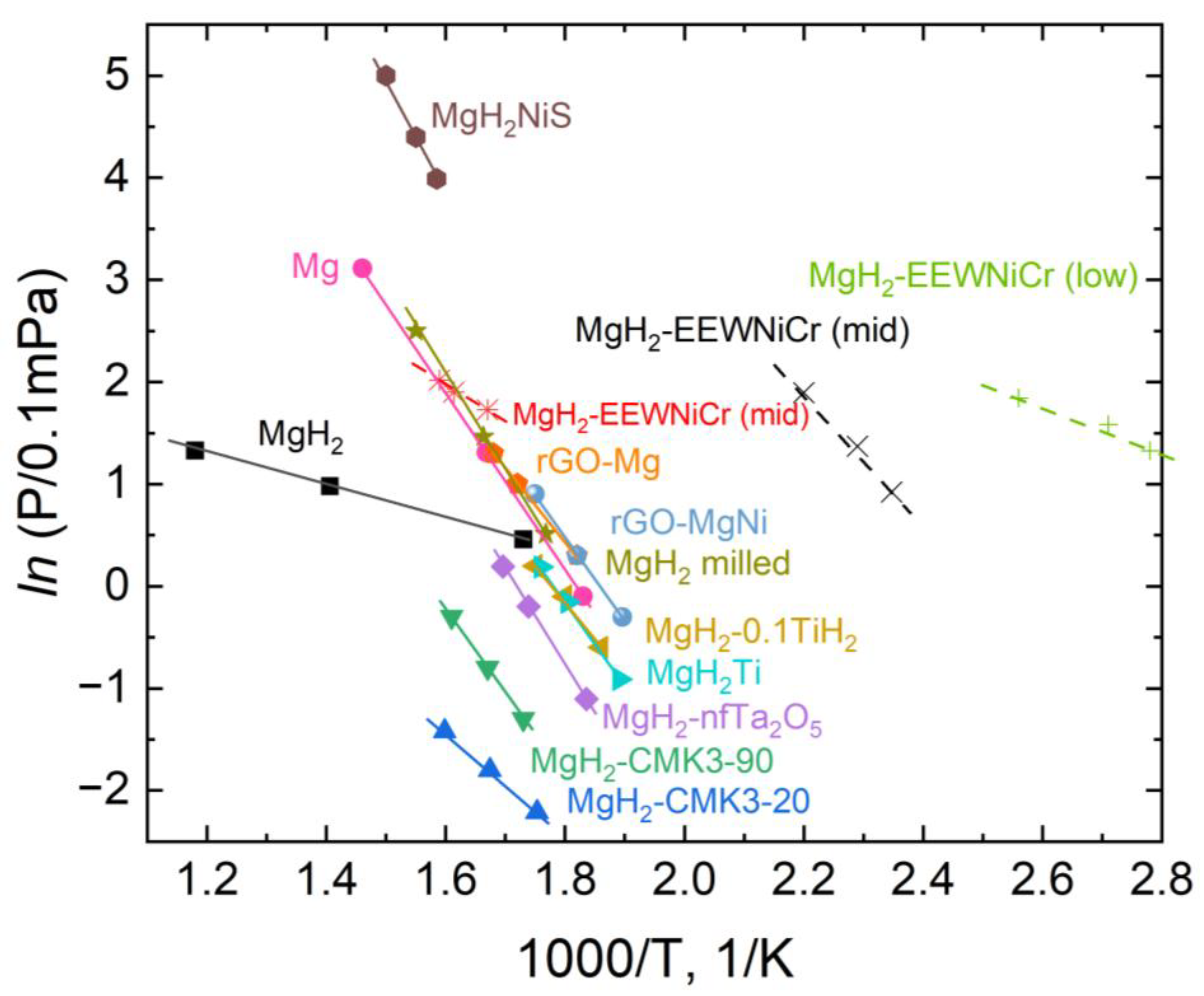

Figure 10 shows graphs of the dependence of

ln (

P) on 1000/

T, representing the efficiency of various materials depending on their hydrogen yield temperature.

As can be seen from the data presented above, the composite material studied in this work is located to the right on the graph. This indicates effective dissociation of the material under the influence of temperature. The MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr material has unique thermodynamic characteristics and allows for easy scaling of the material production technology.

Despite the decrease in the initial hydrogen capacity of the material from 7.2 to 5.2, it remains high enough for use in mobile hydrogen storage systems. In combination with all the advantages of this material over others listed in the study, its use is limited only by the lack of cyclic testing. At present, it is planned to conduct all the missing studies to provide the most comprehensive characterization of the material.

5. Conclusions

The composite MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr (20 wt. %) with hydrogen mass content of 5.2 ± 0.1 wt.% described in this work was synthesized in a planetary ball mill and described using XRD, SEM, EDX, BET, TPD, and DFT analyses. Despite the decrease in the hydrogen capacity of the studied composite material compared to pure magnesium hydride (with hydrogen mass content of 7.2 ± 0.3 wt.%), its hydrogen desorption characteristics have been significantly improved due to the catalytic effect exerted by the added material, as well as due to ball milling.

The composite is characterized by three desorption peaks in different temperature ranges. The presence of three temperature regions is explained by the catalytic effect of the added material. The desorption temperature at a heating rate of 2 °C/min was 86 °C (compared to MgH₂ – 393 °C), which is due to the direct participation of nickel-chromium powder, as well as additional milling with balls and nanoscale particles of the powder itself, which in turn affects the change in the specific surface area. Additional diffusion paths in the crystal lattice of the material make it easier to bind magnesium atoms with hydrogen. The dissociation of the hydride phase in the composite occurs above 250 °C. According to the Kissinger method, the activation energy of desorption is determined to be (65-96) ± 1 kJ/mol, while for hydride it is 155 ± 2 kJ/mol.

Ab initio calculations show that the synergistic effect of Ni and Cr additives on the MgH₂ surface leads to a significant decrease in the hydrogen binding energy compared to pure magnesium hydride. The first peak has a double maximum of low-temperature hydrogen desorption from 70 ℃ to 230 ℃. The presence of a double maximum is due to an uneven decrease in the strength of hydrogen-surface bonds near the additives. In addition to positive hydrogen binding energies, weak hydrogen bonds with the surface, characterized by negative binding energy, are also observed on the MgH₂ surface with Ni and Cr additives. Surface hydrogen atoms with negative binding energies are expected to desorb first and correspond to the lowest temperature desorption peak (~ 90 ℃), whereas hydrogen atoms with positive binding energies desorb at higher temperatures and account for the second peak (~ 150 ℃). The decrease in the strength of the hydrogen-surface bond is caused by the formation of Ni–H and Cr–H covalent bonds, which, due to the redistribution of electron charge on the hydrogen atoms and additives, weaken the ionic bond of hydrogen with nearby magnesium atoms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Viktor Kudiiarov; Data curation, Alan Kenzhiyev and Daria Terenteva; Formal analysis, Alan Kenzhiyev, Daria Terenteva and Dmitrii Vrublevskii; Funding acquisition, Dmitrii Nikitin and Egor Kashkarov; Investigation, Alena Spiridonova; Project administration, Viktor Kudiiarov; Resources, Egor Kashkarov; Software, Daria Terenteva, Dmitrii Vrublevskii and Leonid Svyatkin; Supervision, Viktor Kudiiarov; Validation, Alan Kenzhiyev, Alena Spiridonova, Dmitrii Nikitin and Egor Kashkarov; Writing – original draft, Alan Kenzhiyev and Daria Terenteva; Writing – review & editing, Viktor Kudiiarov and Leonid Svyatkin.

Funding

This research was funded by the Governmental Program, Grant № FSWW-2024-0001

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

Acknowledgment

The scientific infrastructure for the project was organized with the support of Tomsk Polytechnic University’s Priority 2030 development program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABINIT |

lat. Ab initio (“from the beginning”) – first principles calculations |

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory |

| Eb

|

Binding energy |

| Ed

|

Desorption activation energy |

| EEW |

Electrical Explosion of Wires |

| MPF-4 |

Magnesium Powder Fraction-4 |

| GRAM50 |

Gas Reaction Automated Machine 50 bar |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDX |

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| BET |

Brunauer-Emmet-Teller method |

| BJH |

Barrett-Joyner-Halenda method |

| TPD |

Temperature-programmed desorption |

| RGA |

Residual Gas Analyzer |

| JCPDS |

Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| HCP |

Hexagonal Closed Packed lattice |

| BCC |

Base Centered Cubic lattice |

| FCC |

Face Centered Cubic lattice |

References

- Abdi Lanbaran, D.; Wang, C.; Wen, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, B. Modeling the Impact of Temperature-Dependent Thermal Conductivity on Hydrogen Desorption from Magnesium Hydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 138, 491–508. [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kenzhiyev, A.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Terenteva, D.V. Superior Catalytic Activity of Nano Sized Ni Produced by Electrical Explosion of Wires towards the Hydrogen Storage of Magnesium Hydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 436–452. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mao, W.; Su, Y.; Liu, B.; Ji, W. Investigation on Explosion Overpressure and Flame Propagation Characteristics of Magnesium Hydride Dust of Different Particle Sizes. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 438–449. [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Kumar, S.; Majumdar, S. Preparation, Characterization and Modification of Magnesium Hydride for Enhanced Solid-State Hydrogen Storage Properties. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 494–501. [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kenzhiyev, A.; Elman, R.R.; Kurdyumov, N.; Ushakov, I.A.; Tereshchenko, A.V.; Laptev, R.S.; Kruglyakov, M.A.; Khomidzoda, P.I. The Defect Structure Evolution in MgH₂-EEWNi Composites in Hydrogen Sorption–Desorption Processes. Metals 2025, 15, 72. [CrossRef]

- Drawer, C.; Lange, J.; Kaltschmitt, M. Metal Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage – Identification and Evaluation of Stationary and Transportation Applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109988. [CrossRef]

- Elman, R.; Kudiiarov, V.; Sayadyan, A.; Pushilina, N.; Leng, H. Performance Improvement of Magnesium-Based Hydrogen Storage Tanks by Using Carbon Nanotubes Addition and Finned Heat Exchanger: Numerical Simulation and Experimental Verification. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 1375–1388. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, P.; Rathi, B.; Agarwal, S.; Juyal, S.; Gill, F.S.; Kumar, M.; Saini, P.; Dixit, A.; Ichikawa, T.; Jain, A. Core-Shell Structured Ni@C Based Additive for Magnesium Hydride System towards Efficient Hydrogen Sorption Kinetics. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 107, 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Elman, R.; Kudiiarov, V.; Sayadyan, A.; Pushilina, N.; Leng, H. Performance Improvement of Magnesium-Based Hydrogen Storage Tanks by Using Carbon Nanotubes Addition and Finned Heat Exchanger: Numerical Simulation and Experimental Verification. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 92, 1375–1388. [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.; Agarwal, S.; Shrivastava, K.; Kumar, M.; Jain, A. Recent Advances in Designing Metal Oxide-Based Catalysts to Enhance the Sorption Kinetics of Magnesium Hydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 131–162. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, C.; Sui, Y.; Zhai, T.; Hou, Z.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress in Improved Hydrogen Storage Properties of Mg-Based Alloys with Metal-Based Materials and Light Metals. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1401–1417. [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, A.P.; Kanti, P.K.; Mohan, G.; Maiya, M.P. Design and Optimization of Metal Hydride Reactor with Phase Change Material Using Fin Factor for Hydrogen Storage. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109975. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wei, L.; Gong, Y.; Yang, K. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Properties of Magnesium Hydride by Multifunctional Carbon-Based Materials: A Review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 521–541. [CrossRef]

- Markman, E.; Luzzatto-Shukrun, L.; Levy, Y.S.; Pri-Bar, I.; Gelbstein, Y. Effect of Additives on Hydrogen Release Reactivity of Magnesium Hydride Composites. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 31381–31394. [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Laptev, R.S.; Kruglyakov, M.A.; Ushakov, I.A.; Tereshchenko, A.V.; Lider, A.M. The Defect Structure Evolution in Magnesium Hydride/Metal-Organic Framework Structures MIL-101 (Cr) Composite at High Temperature Hydrogen Sorption-Desorption Processes. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 966, 171534. [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, Ö.F.; Topçu, S.; Aksoy, A. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles: Overview and Current Status of Hydrogen Mobility. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 918–936. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Towards Efficient and Safe Hydrogen Storage for Green Shipping: Progress on Critical Technical Issues of Material Development and System Construction. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150913. [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Ayati, A.; Farrokhi, M.; Khadempir, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Farghali, M.; Krivoshapkin, P.; Tanhaei, B.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Innovations in Hydrogen Storage Materials: Synthesis, Applications, and Prospects. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 95, 112376. [CrossRef]

- Kudiiarov, V.N.; Kurdyumov, N.; Elman, R.R.; Svyatkin, L.A.; Terenteva, D.V.; Semyonov, O. Microstructure and Hydrogen Storage Properties of MgH₂/MIL-101(Cr) Composite. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 976, 173093. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Martín-Yerga, D.; Lindén, P.A.; Henriksson, G.; Cornell, A. Green Hydrogen Production via Electrochemical Conversion of Components from Alkaline Carbohydrate Degradation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 3644–3654. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Liu, C.; Feng, Y.; Gao, Z.; Chen, S.; Huang, M.; Ge, H.; Huang, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, W. Size-Dependent Nanoconfinement Effects in Magnesium Hydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 783–793. [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, W.; Berkowicz-Płatek, G.; Wencel, K.; Migas, P.; Wrona, J.; Reyna-Bowen, L. Hydrogen Production from Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers in a Fluidized-Bed Made out of Co3O4-Cenosphere Catalyst. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 136, 358–370. [CrossRef]

- Drawer, C.; Lange, J.; Kaltschmitt, M. Metal Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage – Identification and Evaluation of Stationary and Transportation Applications. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109988. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, C.; Fan, Q.; Wei, Y.; Qu, D.; Li, X.; Xie, Z.; Tang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, D. Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage in Zeolite Template Carbon and Its Application in a Proton/Potassium Hybrid Ion Hydrogel Battery Coupling with Nickel-Zinc Co-Doped Prussian Blue Analogues. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 139–149. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Kundu, A.; Chakraborty, B. High-Capacity Hydrogen Storage in Zirconium Decorated Zeolite Templated Carbon: Predictions from DFT Simulations. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 38671–38681. [CrossRef]

- Kashani, F.Z.; Mohsennia, M. Enhancing Electrochemical Hydrogen Storage in Nickel-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) through Zinc and Cobalt Doping as Bimetallic MOFs. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 101, 348–357. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-Q.; Jiang, W.; Si, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. MOF-Derived Carbon Supported Transition Metal (Fe, Ni) and Synergetic Catalysis for Hydrogen Storage Kinetics of MgH₂. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 445–455. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Q.; He, H. Synergistic Effect of Hydrogen Spillover and Nano-Confined AlH3 on Room Temperature Hydrogen Storage in MOFs: By GCMC, DFT and Experiments. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 72, 1224–1235. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Shi, R.; Shao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. Catalysis Derived from Flower-like Ni MOF towards the Hydrogen Storage Performance of Magnesium Hydride. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9346–9356. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhai, T.; Han, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, T. Review on Improved Hydrogen Storage Properties of MgH₂ by Adding New Catalyst. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112786. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.; Kumar, A. MOFs and MOF Derivatives for Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction: Designing Strategies, Syntheses and Future Prospects. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 150, 150148. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yong, H.; Wang, S.; Yan, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y. Investigating of Hydrolysis Kinetics and Catalytic Mechanism of Mg–Ce–Ni Hydrogen Storage Alloy Catalyzed by Ni/Co/Zn-Based MOF. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 1416–1427. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, T.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Mei, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, C.; Guo, J. Synergistic Dual-Modification Regulation of Dehydrogenation Kinetics of MgH₂ by MOF-Derived Core-Shell Ni&C. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 127, 241–251. [CrossRef]

- Yamçıçıer, Ç.; Kürkçü, C. Investigation of Structural, Electronic, Elastic, Vibrational, Thermodynamic, and Optical Properties of Mg2NiH4 and Mg2RuH4 Compounds Used in Hydrogen Storage. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110883. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, S.; Huang, P.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. A Review on Mg-Based Materials for Hydrogen Storage Tanks: Development and Mechanism. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 135, 121–145. [CrossRef]

- Kapsi, M.; Veziri, C.M.; Pilatos, G.; Karanikolos, G.N.; Romanos, G.E. Zeolite-Templated Sub-Nanometer Carbon Nanotube Arrays and Membranes for Hydrogen Storage and Separation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 36850–36872. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chai, X.; Gu, Y.; Wu, W.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T. Advances in Hydrogen Storage Materials for Physical H₂ Adsorption. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 1261–1274. [CrossRef]

- Worth, J.D.; Ting, V.P.; Faul, C.F.J. Exploring Conjugated Microporous Polymers for Hydrogen Storage: A Review of Current Advances. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 152, 149718. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Li, C. Magic of Hydrogen Spillover: Understanding and Application. Green Energy & Environment 2022, 7, 1161–1198. [CrossRef]

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Ramadhani, S.; Ha, T.; Kim, E.-Y.; Baek, J.; Jeong, D.; Park, G.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Shim, J.-H.; et al. Dual Functionality of LaNi5 Metal Hydride as a Catalyst for Toluene Hydrogenation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 167, 150891. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chabane, D.; Elkedim, O. Optimization of LaNi5 Hydrogen Storage Properties by the Combination of Mechanical Alloying and Element Substitution. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 53, 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Thiangviriya, S.; Thongtan, P.; Thaweelap, N.; Plerdsranoy, P.; Utke, R. Heat Charging and Discharging of Coupled MgH₂–LaNi5 Based Thermal Storage: Cycling Stability and Hydrogen Exchange Reactions. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 59–66. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B.; Ilbas, M.; Celik, S. Experimental Analysis of Hydrogen Storage Performance of a LaNi5–H₂ Reactor with Phase Change Materials. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6010–6022. [CrossRef]

- Plerdsranoy, P.; Utke, R. Effects of Operating Temperatures and Hydrogen Flow Rates during Desorption on Hydrogen Sorption of LaNi5-Based Tanks and Integration with PEMFC Stack. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 582–588. [CrossRef]

- Chibani, A.; Boucetta, C.; Haddad, M.A.N.; Boukhari, A.; Fourar, I.; Merouani, S.; Badji, R.; Adjel, S.; Belkhiria, S.; Boukraa, M.; et al. A Novel Metal Hydride Reactor Design: The Effect of Using Copper, AlN and AlSi10Mg Composite Fins on the Dehydrogenation Process of LaNi5-Metal Alloy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 141, 118–132. [CrossRef]

- Chandra Mouli, B.; Sharma, V.K.; Sanjay; Paswan, M.; Thomas, B. Performance Investigations on Thermochemical Energy Storage System Using Cerium, Aluminium, Manganese, and Tin-Substituted LaNi5 Hydrides. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 1203–1214. [CrossRef]

- Eikeng, E.; Makhsoos, A.; Pollet, B.G. Critical and Strategic Raw Materials for Electrolysers, Fuel Cells, Metal Hydrides and Hydrogen Separation Technologies. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 433–464. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Huang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Gao, M.; Pan, H. Realizing 6.7 Wt% Reversible Storage of Hydrogen at Ambient Temperature with Non-Confined Ultrafine Magnesium Hydrides. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 2302–2313. [CrossRef]

- Parviz, R.; Heydarinia, A.; Nili-Ahmadabadi, M. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage via In-Situ Formation of Oxide, Metallic and Intermetallic Catalysts in a Mg-Based Porous-Layered Composite. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 111, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hong, F.; Li, R.; Zhao, R.; Ding, S.; Liu, Z.; Qing, P.; Fan, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, J.; et al. Improved Hydrogen Storage Properties of MgH₂ by Mxene (Ti3C2) Supported MnO2. Journal of Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108738. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Shukla, V.; Pandey, A.P.; Shaz, M.A. Three-Dimensional Graphene Aerogel Decorated with Nickel Nanoparticles as Additive for Improving the Hydrogen Storage Properties of MgH₂. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 107, 96–107. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, V.B.; Júnior, W.O.; Gonzalez Cruz, E.D.; Leiva, D.R.; Pereira Da Silva, E. Casting of Mg-Based Alloy with Ni and Mishmetal Addition (Mg88Ni8MM4) for Hydrogen Storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 63–66. [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, K.S.; Banapurmath, N.R.; Yaliwal, V.S.; Umarfarooq, M.A.; Sajjan, A.M.; Venkatesh, R.; Hosmath, R.S.; Beena, T.; Yunus Khan, T.M.; Kalam, M.A.; et al. From Nickel–Metal Hydride Batteries to Advanced Engines: A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogen’s Role in the Future Energy Landscape. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 1015–1038. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, L.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. State of the Art Multi-Strategy Improvement of Mg-Based Hydrides for Hydrogen Storage. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2019, 782, 796–823. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X.; Man, X.; Zhai, T.; Han, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen Storage Capabilities Enhancement of MgH₂ Nanocrystals. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 515–527. [CrossRef]

- Polanski, M.; Bystrzycki, J.; Varin, R.A.; Plocinski, T.; Pisarek, M. The Effect of Chromium (III) Oxide (Cr2O3) Nanopowder on the Microstructure and Cyclic Hydrogen Storage Behavior of Magnesium Hydride (MgH₂). Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2011, 509, 2386–2391. [CrossRef]

- Polanski, M.; Bystrzycki, J. Comparative Studies of the Influence of Different Nano-Sized Metal Oxides on the Hydrogen Sorption Properties of Magnesium Hydride. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2009, 486, 697–701. [CrossRef]

- Pukazhselvan, D.; Çaha, I.; De Lemos, C.; Mikhalev, S.M.; Deepak, F.L.; Fagg, D.P. Understanding the Catalysis of Chromium Trioxide Added Magnesium Hydride for Hydrogen Storage and Li Ion Battery Applications. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 2024, 12, 1117–1130. [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, K.S.; Beena, T.; Banapurmath, N.R.; Umarfarooq, M.A.; Ramasamy, V.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Ağbulut, Ü. Advances in Hydrogen Storage with Metal Hydrides: Mechanisms, Materials, and Challenges. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 1259–1273. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, S.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y. Hydrogen Storage Property Improvement of La–Y–Mg–Ni Alloy by Ball Milling with TiF3. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 17957–17969. [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Yao, J.; Yong, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Investigation of Ball-Milling Process on Microstructure, Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Ce–Mg–Ni-Based Hydrogen Storage Alloy. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11274–11286. [CrossRef]

- Shang, C. Mechanical Alloying and Electronic Simulations of (MgH₂+M) Systems (M=Al, Ti, Fe, Ni, Cu and Nb) for Hydrogen Storage. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2004, 29, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Gonze, X.; Amadon, B.; Antonius, G.; Arnardi, F.; Baguet, L.; Beuken, J.-M.; Bieder, J.; Bottin, F.; Bouchet, J.; Bousquet, E.; et al. The Abinitproject: Impact, Environment and Recent Developments. Computer Physics Communications 2020, 248, 107042. [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.H.; Allan, D.C.; Amadon, B.; Antonius, G.; Applencourt, T.; Baguet, L.; Bieder, J.; Bottin, F.; Bouchet, J.; Bousquet, E.; et al. ABINIT: Overview and Focus on Selected Capabilities. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2020, 152, 124102. [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University PressOxford, 1990; ISBN 978-0-19-855168-3.

- Rzeszotarska, M.; Dworecka-Wójcik, J.; Dębski, A.; Czujko, T.; Polański, M. Magnesium-Based Complex Hydride Mixtures Synthesized from Stainless Steel and Magnesium Hydride with Subambient Temperature Hydrogen Absorption Capability. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2022, 901, 163489. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, L. Air Exposure Improving Hydrogen Desorption Behavior of Mg–Ni-Based Hydrides. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 22183–22191. [CrossRef]

- Pericoli, E.; Barzotti, A.; Mazzaro, R.; Moury, R.; Cuevas, F.; Pasquini, L. Synthesis and Hydrogen Storage Properties of Mg-Based Complex Hydrides with Multiple Transition Metal Elements. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 4993–5003. [CrossRef]

- Pukazhselvan, D.; Çaha, I.; De Lemos, C.; Mikhalev, S.M.; Deepak, F.L.; Fagg, D.P. Understanding the Catalysis of Chromium Trioxide Added Magnesium Hydride for Hydrogen Storage and Li Ion Battery Applications. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 2024, 12, 1117–1130. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Chen, L. Promoting Catalysis in Magnesium Hydride for Solid-State Hydrogen Storage through Manipulating the Elements of High Entropy Oxides. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys 2024, 12, 5038–5050. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Bian, T.; Shang, D.; Zhang, L. Enhanced Hydrogen Storage Performance of Magnesium Hydride Catalyzed by Medium-Entropy Alloy CrCoNi Nanosheets. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1015–1024. [CrossRef]

- Bahou, S.; Labrim, H.; Ez-Zahraouy, H. Role of Vacancies and Transition Metals on the Thermodynamic Properties of MgH₂: Ab-Initio Study. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 8179–8188. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Top view (a) and side view (b) of the supercell modelling the (110) surface of α-MgH₂. The atoms of

Mg, H, Ni and Cr colored as gray, pink, blue and purple, respectively.

Figure 1.

Top view (a) and side view (b) of the supercell modelling the (110) surface of α-MgH₂. The atoms of

Mg, H, Ni and Cr colored as gray, pink, blue and purple, respectively.

Figure 2.

Top view of the (110) α-MgH₂ film: pristine surface (a); surface with an adsorbed Ni atom (b); surface with an adsorbed Cr atom (c); surface with co-adsorbed Cr and Ni atoms (d). The atoms of Mg, H, Ni and Cr coloured as gray, pink, blue and purple, respectively. Concentric regions with radii r1, r2, … r5 are drawn on the MgH₂ surface relative to the mass center of the surface impurities. Nonequivalent surface H atoms are marked by crosshairs and numbered for ease of discussion.

Figure 2.

Top view of the (110) α-MgH₂ film: pristine surface (a); surface with an adsorbed Ni atom (b); surface with an adsorbed Cr atom (c); surface with co-adsorbed Cr and Ni atoms (d). The atoms of Mg, H, Ni and Cr coloured as gray, pink, blue and purple, respectively. Concentric regions with radii r1, r2, … r5 are drawn on the MgH₂ surface relative to the mass center of the surface impurities. Nonequivalent surface H atoms are marked by crosshairs and numbered for ease of discussion.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of magnesium hydride and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite with corresponding JCPDS cards

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of magnesium hydride and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite with corresponding JCPDS cards

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of MgH₂ (a) and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite with the corresponding elemental mapping analysis (EDX) (b, d) and particle size distribution for MgH₂ (e) and composite (f).

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of MgH₂ (a) and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr composite with the corresponding elemental mapping analysis (EDX) (b, d) and particle size distribution for MgH₂ (e) and composite (f).

Figure 5.

N₂ adsorption-desorption isotherms for MgH₂ (a), EEWNi-Cr (b) and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr (c).

Figure 5.

N₂ adsorption-desorption isotherms for MgH₂ (a), EEWNi-Cr (b) and MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr (c).

Figure 6.

Temperature-programmed desorption of hydrogen for MgH₂ and MgH₂–EEWNi-Cr composite (a), the relationship between and for pure MgH₂ and composite MgH₂–EEWNi-Cr (b).

Figure 6.

Temperature-programmed desorption of hydrogen for MgH₂ and MgH₂–EEWNi-Cr composite (a), the relationship between and for pure MgH₂ and composite MgH₂–EEWNi-Cr (b).

Figure 7.

in situ XRD pattern, obtained in situ during heating for (a) MgH₂ and (c) MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr, graph of phase transformations during heating: 1 – decrease in the MgH₂ phase, 2 – increase in the Mg phase, 3 – thermal-stimulated desorption for (b) MgH₂ and (d) MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr.

Figure 7.

in situ XRD pattern, obtained in situ during heating for (a) MgH₂ and (c) MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr, graph of phase transformations during heating: 1 – decrease in the MgH₂ phase, 2 – increase in the Mg phase, 3 – thermal-stimulated desorption for (b) MgH₂ and (d) MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr.

Figure 8.

The valence electron density distribution and Bader charge transfer Δq on atoms on the pristine (110) surface on α-MgH₂ (a), and of α-MgH₂ (110) surfaces with adsorbed Ni atom (b), Cr atom (c), and the Ni–Cr complex (d). The atoms of Mg, H, Ni and Cr coloured as gray, pink, blue, and purple, respectively. Isosurfaces corresponding to electron densities of 0.02 e/ų and 0.05 e/ų are shown in burgundy and green, respectively.

Figure 8.

The valence electron density distribution and Bader charge transfer Δq on atoms on the pristine (110) surface on α-MgH₂ (a), and of α-MgH₂ (110) surfaces with adsorbed Ni atom (b), Cr atom (c), and the Ni–Cr complex (d). The atoms of Mg, H, Ni and Cr coloured as gray, pink, blue, and purple, respectively. Isosurfaces corresponding to electron densities of 0.02 e/ų and 0.05 e/ų are shown in burgundy and green, respectively.

Figure 9.

Results of cyclic tests on MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr.

Figure 9.

Results of cyclic tests on MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the effectiveness of composites for hydrogen storage.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the effectiveness of composites for hydrogen storage.

Table 1.

Values of microstrains in materials.

Table 1.

Values of microstrains in materials.

| Sample |

Phases (PowderCell24 cards) |

Phase content, ± 0.2 vol. % |

Lattice prameteres,

± 0.0005 Å

|

Crystalline size,

± 0.05 nm

|

Microstrains,

± 0.0003 ∆d/d

|

| MgH₂ |

Mg-00-035-0821 |

16.6 |

a = 3.1998

с = 5.1978 |

36.84 |

0.0011 |

| MgH₂-00-012-0697_tet |

83.4 |

a = 4.5003

c = 3.0142 |

64.98 |

0.0016 |

| EEWNi-Cr |

Cr0.4Ni0.6-04-001-3422 |

100 |

a = 3.5540 |

40.49 |

0.0004 |

| MgH₂–20 wt.% EEWNi-Cr |

Mg-00-035-0821 |

9.7 |

a = 3.1950

c = 5.2020 |

7.37 |

0.0054 |

| MgH₂-00-012-0697_tet |

85.8 |

a = 4.5070

c = 3.0110 |

40.95 |

0.0062 |

| Cr0.4Ni0.6-04-001-3422 |

4.5 |

a = 3.5490 |

23.3 |

0.0011 |

Table 2.

BET analysis parameters.

Table 2.

BET analysis parameters.

| Sample |

Degassing vacuum |

BET surface area, m2/g |

Total pore volume, cm3/g |

Average pore diameter, nm |

| MgH₂ (0.4347 g) |

10 h 573 K |

8.5 |

0.014 |

6.4 |

| EEWNi-Cr (0.8781 g) |

6.2 |

0.013 |

8.1 |

| MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr (20 wt.%) (0.3409 g) |

10.6 |

0.031 |

11.5 |

| MgH₂-EEWNi-Cr (25 wt.%) (0.2321 g) |

28.5 |

0.099 |

13.9 |

Table 4.

Hydrogen binding energies for the Mg₄₈H₉₆, Mg₄₈H₉₆Ni, Mg₄₈H₉₆Cr, and Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr systems.

Table 4.

Hydrogen binding energies for the Mg₄₈H₉₆, Mg₄₈H₉₆Ni, Mg₄₈H₉₆Cr, and Mg₄₈H₉₆NiCr systems.

| System |

Position of the H atom relative to the adsorbate, as defined in Figure 2 |

Hydrogen binding energy, eV |

| Distance r from the mass center of the adsorbate |

Label |

| Mg48H96

|

- |

H3 |

1.307 |

| H7 |

1.514 |

| Mg48H96Ni |

r < r1

|

H1 |

0.829 |

| H4 |

1.227 |

|

r1< r < r2

|

H5 |

0.798 |

| H7 |

0.969 |

|

r2< r < r3

|

H9 |

1.159 |

| H10 |

1.106 |

| H12 |

1.159 |

| H13 |

1.048 |

|

r3< r < r4

|

H11 |

1.139 |

| Mg48H96Cr |

r < r1

|

H1 |

1.071 |

| H4 |

1.369 |

|

r1< r < r2

|

H5 |

0.461 |

| H3 |

0.227 |

|

r2< r < r3

|

H7 |

0.089 |

| H9 |

0.918 |

|

r ≈ r4

|

H11 |

1.363 |

| Mg48H96NiCr |

r < r1

|

H1 |

1.009 |

| H₂ |

0.384 |

| H3 |

0.922 |

| H4 |

0.482 |

|

r1< r < r2

|

H5 |

0.729 |

| H6 |

0.626 |

|

r2< r < r3

|

H7 |

0.208 |

| H8 |

0.695 |

| H9 |

1.016 |

| H10 |

-0.624 |

|

r ≈ r5

|

H11 |

0.770 |

Table 5.

The range of H–Mg bond lengths on the (110) surface of the Mg48H96, Mg48H96Ni, Mg48H96Cr, and Mg48H96NiCr systems.

Table 5.

The range of H–Mg bond lengths on the (110) surface of the Mg48H96, Mg48H96Ni, Mg48H96Cr, and Mg48H96NiCr systems.

| Atom H |

, Å

|

| Mg48H96

|

Mg48H96Ni |

Mg48H96Cr |

Mg48H96NiCr |

| H1 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.964–2.335 |

2.117–2.927 |

2.037–2.392 |

| H2 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.886–1.970 |

2.117–2.927 |

1.899–2.983 |

| H3 |

1.865–1.865 |

2.014–2.278 |

1.867–1.914 |

2.005–2.137 |

| H4 |

1.865–1.865 |

2.014–2.278 |

1.987–1.987 |

1.989–2.055 |

| H5 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.914–1.994 |

1.885–1.930 |

1.893–1.911 |

| H6 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.926–1.994 |

1.885–1.930 |

1.888–1.998 |

| H7 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.837–1.957 |

1.958–2.025 |

1.927–1.984 |

| H8 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.960–2.078 |

1.926–2.025 |

1.895–1.934 |

| H9 |

1.865–1.865 |

2.064–2.089 |

1.947–2.089 |

1.977–2.008 |

| H10 |

1.865–1.865 |

2.064–2.089 |

1.869–1.877 |

1.864–1.874 |

| H11 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.879–2.000 |

1.945–2.036 |

1.879–1.992 |

| H12 |

1.865–1.865 |

1.885–1.885 |

1.867–1.914 |

1.858–1.898 |

| H13 |

1.937–1.988 |

1.895–1.957 |

1.954–1.991 |

1.933–1.943 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).