Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Properties of Oxide Surfaces

3.1. Titanate Surfaces

3.2. Aluminate Surfaces

3.3. Cobaltate Surfaces

3.4. Manganite Surfaces

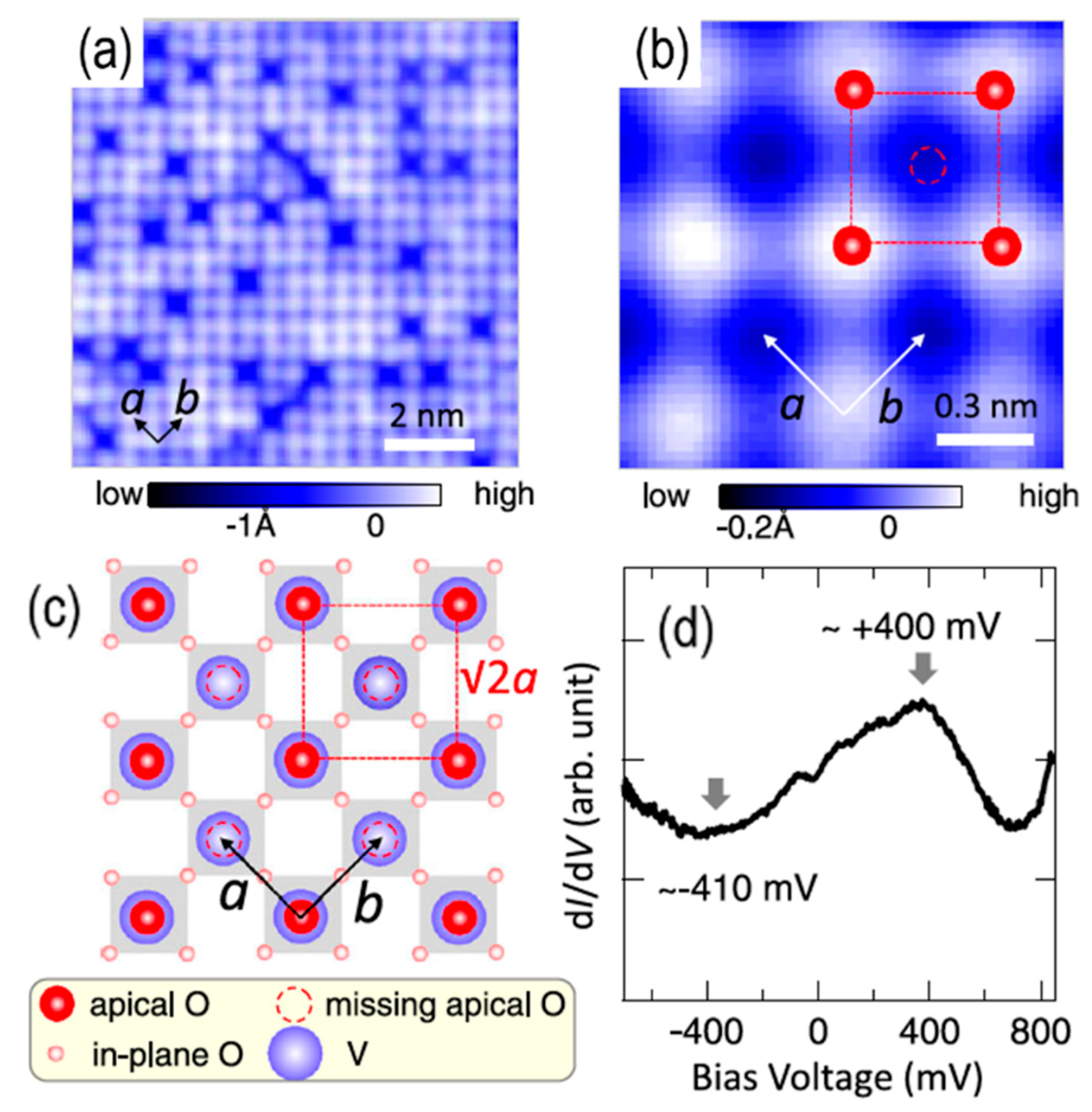

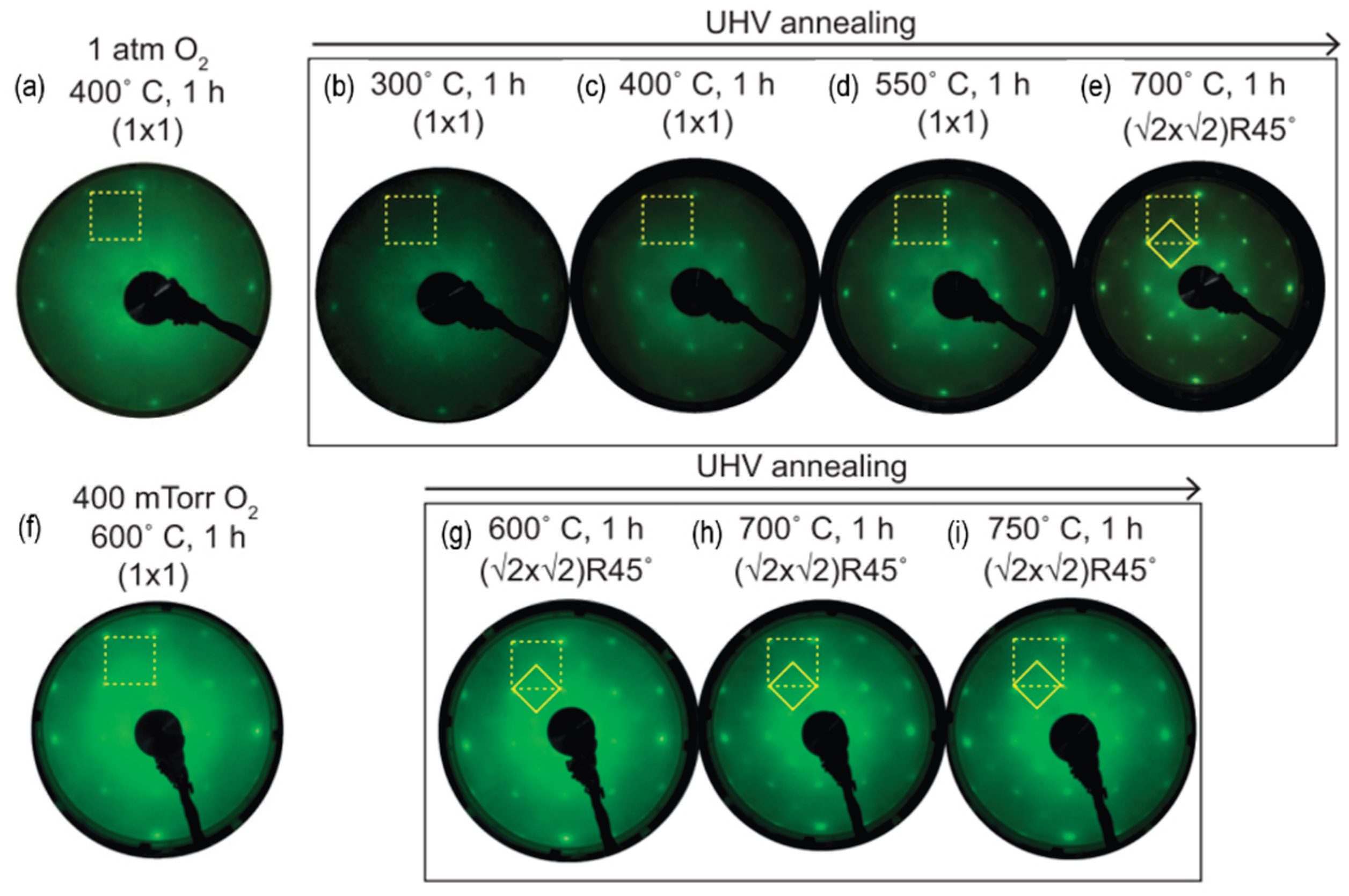

3.5. Other Systems: Vanadate and Stannate Surfaces

4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertaglia, T., et al., Eco-friendly, sustainable, and safe energy storage: a nature-inspired materials paradigm shift. Materials Advances, 2024. 5(19): p. 7534-7547. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A., et al., Recycling of waste into useful materials and their energy applications, in Microbial Niche Nexus Sustaining Environmental Biological Wastewater and Water-Energy-Environment Nexus. 2025, Springer. p. 251-296.

- Worku, A.K., et al., Recent advances and challenges of hydrogen production technologies via renewable energy sources. Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research, 2024. 5(5): p. 2300273. [CrossRef]

- Loubani, M.E., et al., Multifunctional Electrocatalysts for Low-temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. 2024.

- El Loubani, M., et al., Influence of redox engineering on the trade-off relationship between thermopower and electrical conductivity in lanthanum titanium based transition metal oxides. Materials Advances, 2024. 5(22): p. 9007-9017. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., et al., Achieving Fast Oxygen Reduction on Oxide Electrodes by Creating 3D Multiscale Micro-Nano Structures for Low-Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2023. 15(43): p. 50427-50436. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., et al., Understanding the influence of strain-modified oxygen vacancies and surface chemistry on the oxygen reduction reaction of epitaxial La0. 8Sr0. 2CoO3-δ thin films. Solid State Ionics, 2023. 393: p. 116171. [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M., et al., Perovskite type ABO3 oxides in photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and solid oxide fuel cells: State of the art and future prospects. Chemical Reviews, 2025. 125(6): p. 3165-3241. [CrossRef]

- Maggard, P.A., Capturing metastable oxide semiconductors for applications in solar energy conversion. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2021. 54(16): p. 3160-3171. [CrossRef]

- Park, J., et al., Applicability of Allen–Heine–Cardona theory on Mo x metal oxides and ABO3 perovskites: Toward high-temperature optoelectronic applications. Chemistry of Materials, 2022. 34(13): p. 6108-6115.

- Yang, G., et al., Control of crystallographic orientation in Ruddlesden-Popper for fast oxygen reduction. Catalysis Today, 2023. 409: p. 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.N., et al., Designing Eco-functional redox conversions integrated in environmental photo (electro) catalysis. ACS ES&T Engineering, 2022. 2(6): p. 1116-1129. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., K.A. Steiniger, and T.H. Lambert, Electrophotocatalysis: combining light and electricity to catalyze reactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2022. 144(28): p. 12567-12583. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., et al., Universal band alignment rule for perovskite/organic heterojunction interfaces. ACS Energy Letters, 2023. 8(3): p. 1313-1321. [CrossRef]

- Chrysler, M., et al., Tuning band alignment at a semiconductor-crystalline oxide heterojunction via electrostatic modulation of the interfacial dipole. Physical Review Materials, 2021. 5(10): p. 104603. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z., et al., Surface coverage and reconstruction analyses bridge the correlation between structure and activity for electrocatalysis. Chemical Communications, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Blank, D.H., M. Dekkers, and G. Rijnders, Pulsed laser deposition in Twente: from research tool towards industrial deposition. Journal of physics D: applied physics, 2013. 47(3): p. 034006. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., et al., Recent Advances on Pulsed Laser Deposition of Large-Scale Thin Films. Small Methods, 2024. 8(7): p. 2301282. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.M., The Influence of various parameters on the ablation and deposition mechanisms in pulsed laser deposition. Plasmonics, 2025: p. 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., et al., Review on preparation of perovskite solar cells by pulsed laser deposition. Inorganics, 2024. 12(5): p. 128. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A., et al., Hybrid molecular beam epitaxy for the growth of stoichiometric BaSnO3. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A: Vacuum, Surfaces, and Films, 2015. 33(6): p. 060608. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, W. and M. Usman, Applications of molecular beam epitaxy in optoelectronic devices: an overview. Physica Scripta, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nunn, W., T.K. Truttmann, and B. Jalan, A review of molecular-beam epitaxy of wide bandgap complex oxide semiconductors. Journal of materials research, 2021. 36(23): p. 4846-4864. [CrossRef]

- Rimal, G. and R.B. Comes, Advances in complex oxide quantum materials through new approaches to molecular beam epitaxy. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2024. 57(19): p. 193001. [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R. and B. Jalan, Atomically precise synthesis of oxides with hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. Device, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ruvireta, J., L. Vega, and F. Viñes, Cohesion and coordination effects on transition metal surface energies. Surface Science, 2017. 664: p. 45-49. [CrossRef]

- Noguera, C., Physics and chemistry at oxide surfaces. 1996: Cambridge University Press.

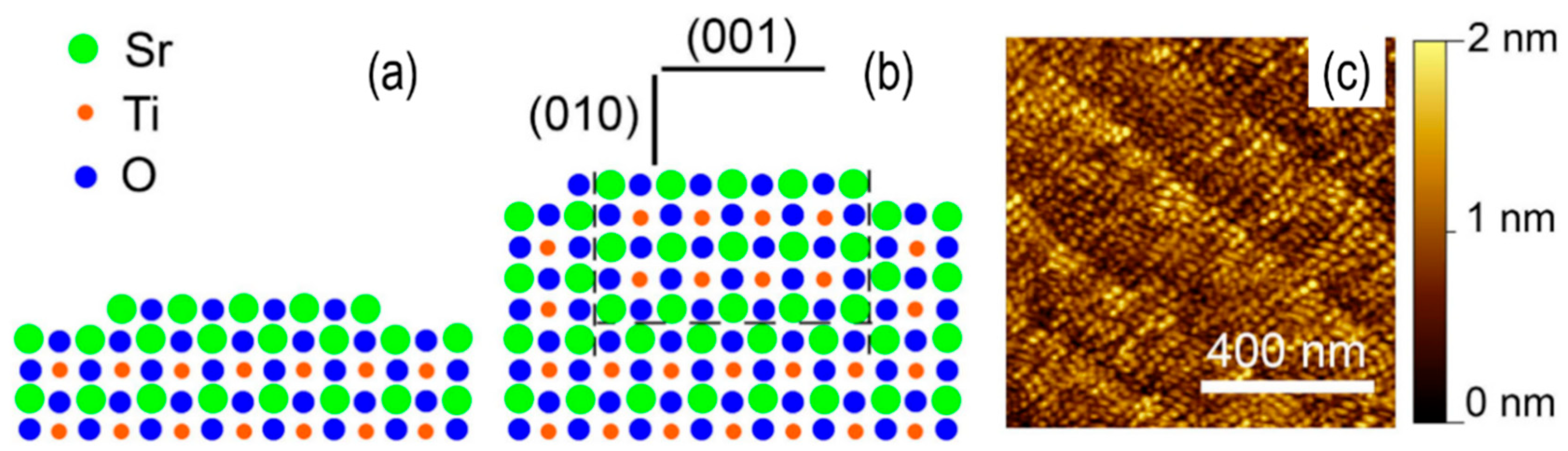

- Kawasaki, M., et al., Atomic Control of the SrTiO3 Crystal Surface. Science, 1994. 266(5190): p. 1540-1542.

- Kubo, T. and H. Nozoye, Surface structure of SrTiO3(100). Surface Science, 2003. 542(3): p. 177-191.

- Castell, M.R., Nanostructures on the SrTiO3(001) surface studied by STM. Surface Science, 2002. 516(1): p. 33-42. [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, T., et al., Negligible Sr segregation on SrTiO3(001)-( 13×13)-R33.7° reconstructed surfaces. Applied Physics Letters, 2016. 108(16): p. 161603.

- Hesselberth, M., S. van der Molen, and J. Aarts, The surface structure of SrTiO3 at high temperatures under influence of oxygen. Applied Physics Letters, 2014. 104(5): p. 051609. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Evolution of the surface structures on SrTiO 3 (110) tuned by Ti or Sr concentration. Physical Review B, 2011. 83(15): p. 155453.

- Marks, L., et al., Transition from order to configurational disorder for surface reconstructions on SrTiO 3 (111). Physical review letters, 2015. 114(22): p. 226101.

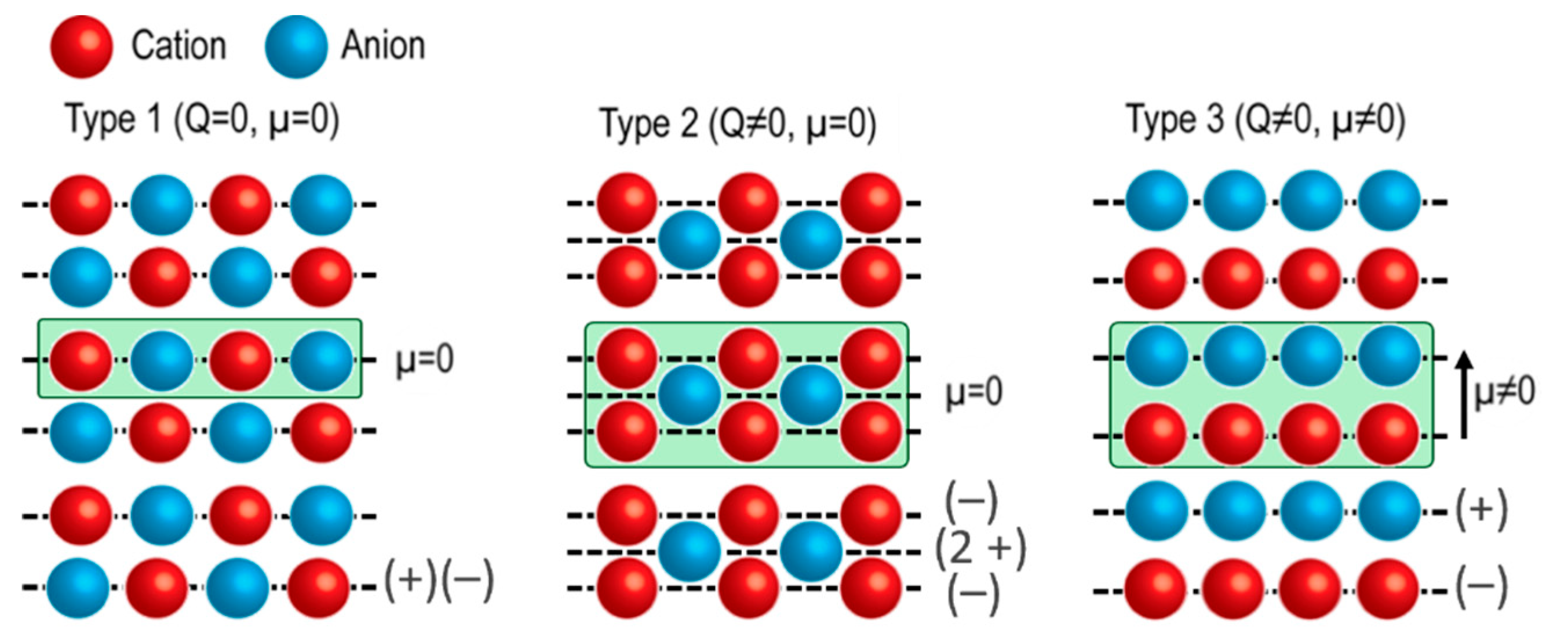

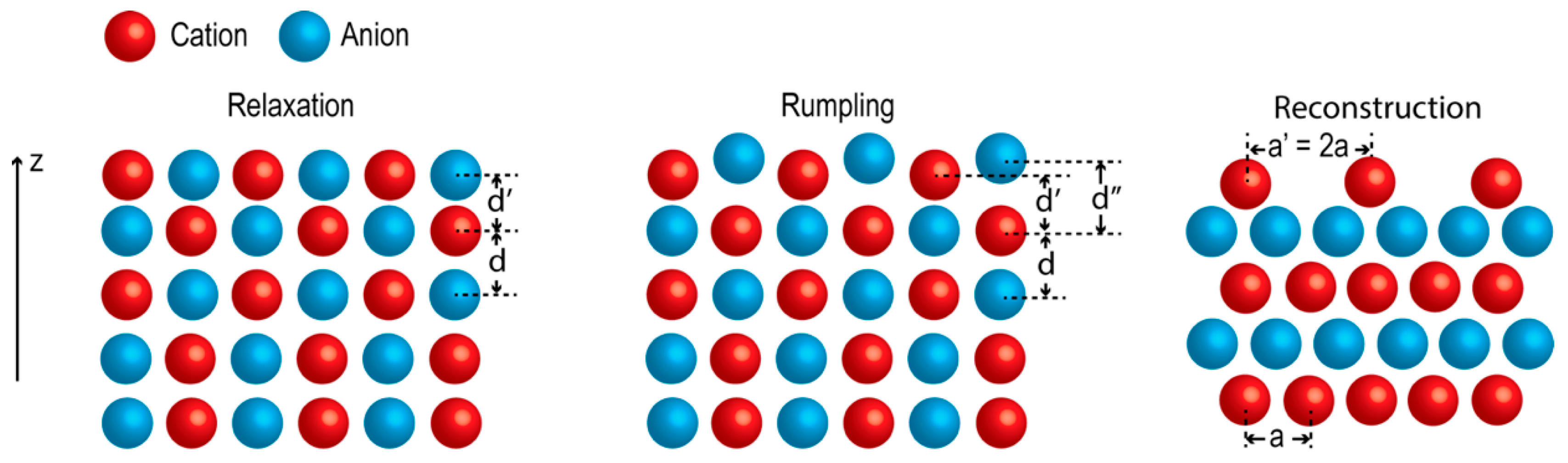

- Goniakowski, J., F. Finocchi, and C. Noguera, Polarity of oxide surfaces and nanostructures. Reports on Progress in Physics, 2007. 71(1): p. 016501. [CrossRef]

- Claudine, N., Polar oxide surfaces. J. Phys, 2000. 12: p. R367.

- Druce, J., et al., Surface termination and subsurface restructuring of perovskite-based solid oxide electrode materials. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014. 7(11): p. 3593-3599. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A., et al., Atomically flat single terminated oxide substrate surfaces. Progress in Surface Science, 2017. 92(2): p. 117-141. [CrossRef]

- Tasker, P., The stability of ionic crystal surfaces. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics, 1979. 12(22): p. 4977. [CrossRef]

- Torrelles, X., et al., Electronic and structural reconstructions of the polar (111) SrTiO 3 surface. Physical Review B, 2019. 99(20): p. 205421.

- May, K.J., et al., Thickness-dependent photoelectrochemical water splitting on ultrathin LaFeO3 films grown on Nb: SrTiO3. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2015. 6(6): p. 977-985.

- Lee, D., et al., Oxygen surface exchange kinetics and stability of (La, Sr) 2 CoO 4±δ/La 1− x Sr x MO 3− δ (M= Co and Fe) hetero-interfaces at intermediate temperatures. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2015. 3(5): p. 2144-2157.

- Lim, H., et al., Nature of the surface space charge layer on undoped SrTiO 3 (001). Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2021. 9(38): p. 13094-13102. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., et al., Enhanced oxygen surface exchange kinetics and stability on epitaxial La0. 8Sr0. 2CoO3− δ thin films by La0. 8Sr0. 2MnO3− δ decoration. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2014. 118(26): p. 14326-14334.

- Gurylev, V., C.-Y. Su, and T.-P. Perng, Surface reconstruction, oxygen vacancy distribution and photocatalytic activity of hydrogenated titanium oxide thin film. Journal of Catalysis, 2015. 330: p. 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Oka, H., et al., Two distinct surface terminations of SrVO3 (001) ultrathin films as an influential factor on metallicity. Applied Physics Letters, 2018. 113(17): p. 171601. [CrossRef]

- Herklotz, A., et al., Strain coupling of oxygen non-stoichiometry in perovskite thin films. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 2017. 29(49): p. 493001. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K., et al., The roles of oxygen vacancies in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Nano energy, 2020. 73: p. 104761. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., et al., Tuning perovskite oxides by strain: Electronic structure, properties, and functions in (electro) catalysis and ferroelectricity. Materials Today, 2019. 31: p. 100-118. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. and B. Jalan, Wide bandgap perovskite oxides with high room-temperature electron mobility. Advanced Materials Interfaces, 2019. 6(15): p. 1900479. [CrossRef]

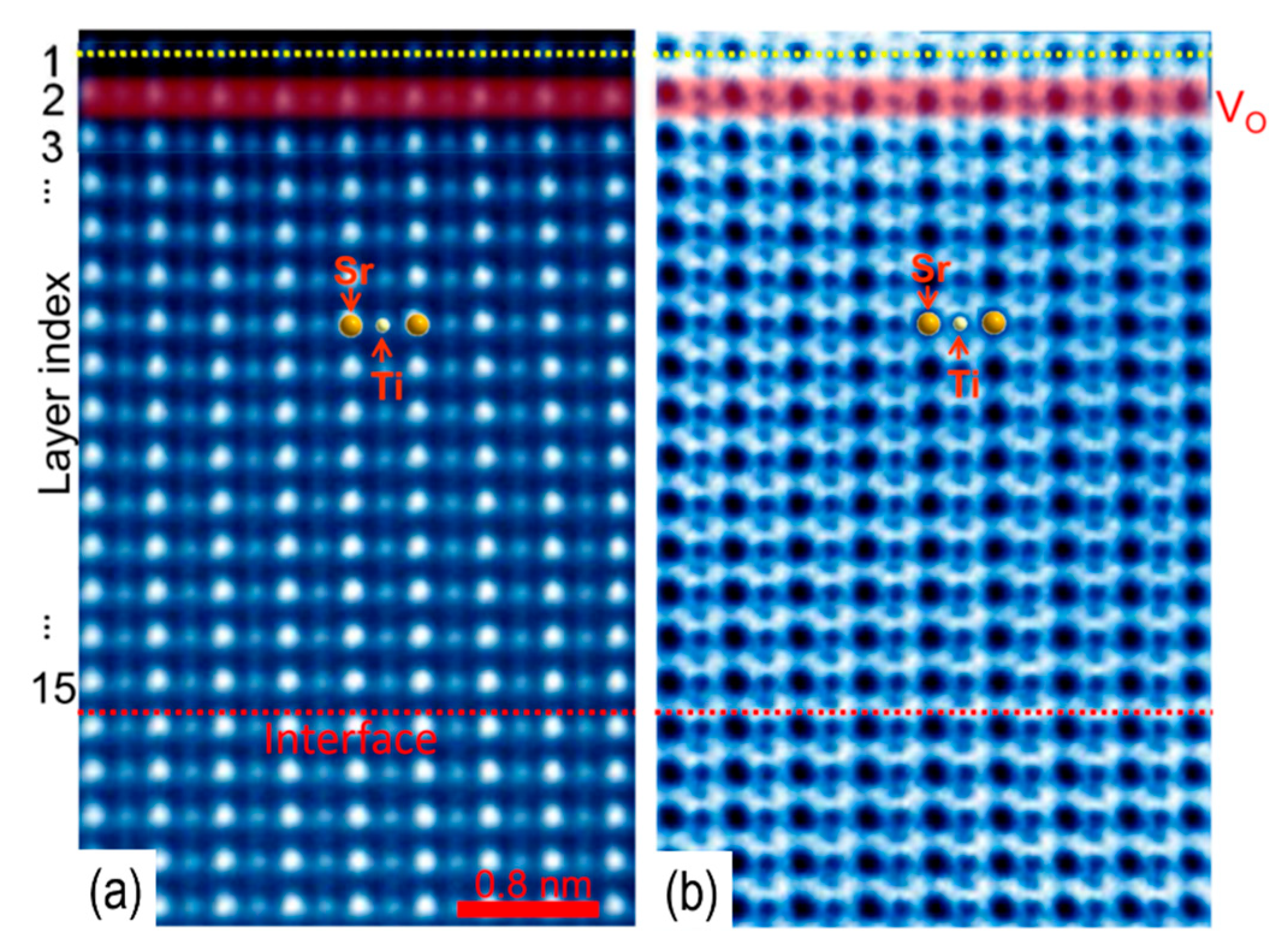

- Tung, I.-C., et al., Polarity-driven oxygen vacancy formation in ultrathin LaNiO 3 films on SrTiO 3. Physical Review Materials, 2017. 1(5): p. 053404.

- Riva, M., et al., Pushing the detection of cation nonstoichiometry to the limit. Physical Review Materials, 2019. 3(4): p. 043802. [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, Y., et al., Growth of Ruddlesden-Popper type faults in Sr-excess SrTiO3 homoepitaxial thin films by pulsed laser deposition. Applied Physics Letters, 2011. 99(17): p. 173109. [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, T., et al., Defects and transport in complex oxide thin films. Journal of Applied Physics, 2008. 103(10): p. 103703. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., Controlling cation segregation in perovskite-based electrodes for high electro-catalytic activity and durability. Chemical Society Reviews, 2017. 46(20): p. 6345-6378. [CrossRef]

- Aravinthkumar, K., et al., Investigation on SrTiO3 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic activity and photovoltaic applications. Inorganic Chemistry Communications, 2022. 140: p. 109451. [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, M.M. and D. Gogova, Theoretical study on electronic, optical, magnetic and photocatalytic properties of codoped SrTiO3 for green energy application. Micro and Nanostructures, 2022. 168: p. 207302. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., et al., Efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under visible-light irradiation on SrTiO3 without noble metal: dye-sensitization and earth-abundant cocatalyst modification. Materials Today Chemistry, 2022. 26: p. 101018. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., et al., Layered SrTiO3/BaTiO3 composites with significantly enhanced dielectric permittivity and low loss. Ceramics International, 2023. 49(14): p. 23326-23333. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J., et al., Enhanced optical and dielectric properties of rare-earth co-doped SrTiO3 ceramics. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2021. 32(10): p. 13837-13849. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L., et al., High dielectric permittivity and ultralow dielectric loss in Nb-doped SrTiO3 ceramics. Ceramics International, 2022. 48(19): p. 28438-28443. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., et al., Review on fabrication methods of SrTiO3-based two dimensional conductive interfaces. The European Physical Journal Applied Physics, 2021. 93(2): p. 21302. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., et al., LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface: 20 years and beyond. Advanced Electronic Materials, 2024. 10(3): p. 2300730.

- Zhang, Z., et al., Tuning the magnetic anisotropy of La0. 67Sr0. 33MnO3 by CaTiO3 spacer layer on the platform of SrTiO3. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 2022. 554: p. 169299. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J., et al., Heterogeneous integration of high-k complex-oxide gate dielectrics on wide band-gap high-electron-mobility transistors. Communications Engineering, 2024. 3(1): p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Eom, K., et al., Electronically reconfigurable complex oxide heterostructure freestanding membranes. Science Advances, 2021. 7(33): p. eabh1284. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., et al., Low-frequency noise behaviors of quasi-two-dimensional electron systems based on complex oxide heterostructures. Current Applied Physics, 2024. 59: p. 129-135. [CrossRef]

- Jäger, M., et al., Independence of surface morphology and reconstruction during the thermal preparation of perovskite oxide surfaces. Applied Physics Letters, 2018. 112(11): p. 111601. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., et al., Formation mechanism of Ruddlesden-Popper-type antiphase boundaries during the kinetically limited growth of Sr rich SrTiO3 thin films. Scientific Reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 38296. [CrossRef]

- Li, F., et al., δ-Doping of oxygen vacancies dictated by thermodynamics in epitaxial SrTiO3 films. AIP Advances, 2017. 7(6): p. 065001. [CrossRef]

- Qu, H., et al., Thermally stimulated relaxation and behaviors of oxygen vacancies in SrTiO3 single crystals with (100), (110) and (111) orientations. Materials Research Express, 2020. 7(4): p. 046305. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Transition from Reconstruction toward Thin Film on the (110) Surface of Strontium Titanate. Nano Letters, 2016. 16(4): p. 2407-2412. [CrossRef]

- Riva, M., et al., Epitaxial growth of complex oxide films: Role of surface reconstructions. Physical Review Research, 2019. 1(3): p. 033059. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.K., et al., Single-layer TiOx reconstructions on SrTiO3 (111): (√7 × √7)R19.1°, (√13 × √13)R13.9°, and related structures. Surface Science, 2018. 675: p. 36-41.

- Song, K., et al., Electronic and Structural Transitions of LaAlO3/SrTiO3 Heterostructure Driven by Polar Field-Assisted Oxygen Vacancy Formation at the Surface. Advanced Science, 2021. 8(14): p. 2002073.

- Kim, J.R., et al., Experimental realization of atomically flat and Al O 2-terminated LaAl O 3 (001) substrate surfaces. Physical Review Materials, 2019. 3(2): p. 023801.

- Sha, H., et al., Surface termination and stoichiometry of LaAlO3(001) surface studied by HRTEM. Micron, 2020. 137: p. 102919. [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P., et al., Al rich (111) and (110) surfaces of LaAlO3. Surface Science, 2018. 677: p. 99-104.

- Kienzle, D., P. Koirala, and L.D. Marks, Lanthanum aluminate (110) 3×1 surface reconstruction. Surface Science, 2015. 633: p. 60-67. [CrossRef]

- Altaf, A., et al., Enhanced electrocatalytic activity of amorphized LaCoO3 for oxygen evolution reaction. Chemistry–An Asian Journal, 2024. 19(16): p. e202300870. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, E., et al., LaCoO3-BaCoO3 porous composites as efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023. 473: p. 144829. [CrossRef]

- Parwaiz, S., et al., Recent advances in LaCoO3-based perovskite nanostructures for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic applications. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, 2025: p. 1-42. [CrossRef]

- Xia, B., et al., Optimized conductivity and spin states in N-doped LaCoO3 for oxygen electrocatalysis. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2021. 13(2): p. 2447-2454. [CrossRef]

- Ingavale, S., et al., Strategic design and insights into lanthanum and strontium perovskite oxides for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Small, 2024. 20(19): p. 2308443. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., et al., An efficient and robust lanthanum strontium cobalt ferrite catalyst as a bifunctional oxygen electrode for reversible solid oxide cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2021. 9(9): p. 5507-5521. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., et al., Cobalt-based perovskite electrodes for solid oxide electrolysis cells. Inorganics, 2022. 10(11): p. 187. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., et al., Controlling the oxygen electrocatalysis on perovskite and layered oxide thin films for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. Applied Sciences, 2019. 9(5): p. 1030. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., et al., Revealing the atomic structure and strontium distribution in nanometer-thick La 0.8 Sr 0.2 CoO 3− δ grown on (001)-oriented SrTiO 3. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014. 7(3): p. 1166-1174. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., et al., Temporal and thermal evolutions of surface Sr-segregation in pristine and atomic layer deposition modified La 0.6 Sr 0.4 CoO 3− δ epitaxial films. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2018. 6(47): p. 24378-24388.

- Khan, S., et al., A computational modelling study of oxygen vacancies at LaCoO 3 perovskite surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2006. 8(44): p. 5207-5222. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, G.M., et al., Surface chemistry of La 0.6 Sr 0.4 CoO 3− δ thin films and its impact on the oxygen surface exchange resistance. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2015. 3(45): p. 22759-22769.

- Hu, M., et al., Reconstruction-stabilized epitaxy of LaCoO3/SrTiO3 (111) heterostructures by pulsed laser deposition. Applied Physics Letters, 2018. 112(3): p. 031603. [CrossRef]

- Halilov, S., et al., Surface, final state, and spin effects in the valence-band photoemission spectra of LaCoO 3 (001). Physical Review B, 2017. 96(20): p. 205144.

- Crumlin, E.J., et al., Surface strontium enrichment on highly active perovskites for oxygen electrocatalysis in solid oxide fuel cells. Energy & Environmental Science, 2012. 5(3): p. 6081-6088. [CrossRef]

- Ashok, A., et al., Enhancing the electrocatalytic properties of LaMnO3 by tuning surface oxygen deficiency through salt assisted combustion synthesis. Catalysis Today, 2021. 375: p. 484-493. [CrossRef]

- Du, D., et al., A-site cationic defects induced electronic structure regulation of LaMnO3 perovskite boosts oxygen electrode reactions in aprotic lithium–oxygen batteries. Energy Storage Materials, 2021. 43: p. 293-304. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q., et al., Achieving efficient toluene mineralization over ordered porous LaMnO3 catalyst: the synergistic effect of high valence manganese and surface lattice oxygen. Applied Surface Science, 2023. 615: p. 156248. [CrossRef]

- Shao-Horn, Y., Thickness dependence of oxygen reduction reaction kinetics on strontium-substituted lanthanum manganese perovskite thin-film microelectrodes. Electrochemical and Solid-State Letters, 2009. 12(5): p. B82. [CrossRef]

- Hess, F. and B. Yildiz, Polar or not polar? The interplay between reconstruction, Sr enrichment, and reduction at the La 0.75 Sr 0.25 MnO 3 (001) surface. Physical review materials, 2020. 4(1): p. 015801. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., et al., Surface and interface properties of L a 2/3 S r 1/3 Mn O 3 thin films on SrTiO 3 (001). Physical Review Materials, 2019. 3(4): p. 044407.

- Franceschi, G., et al., Atomically resolved surface phases of La0.8Sr0.2MnO3(110) thin films. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2020.

- Vasudevan, R.K., et al., Surface reconstructions and modified surface states in L a 1− x C ax Mn O 3. Physical Review Materials, 2018. 2(10): p. 104418.

- Roth, J., et al., Self-regulated growth of [111]-oriented perovskite oxide films using hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. APL Materials, 2021. 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y., et al., Chemical trends of surface reconstruction and band positions of nonmetallic perovskite oxides from first principles. Chemistry of Materials, 2023. 35(5): p. 2047-2057. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al., First-Principles Study of Dominant Surface Terminations on BaSnO3 (001) Surface: Implications for Precise Control of Semiconductor Thin Films. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2024. 7(10): p. 11995-12002. [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, A., et al., Tuning the transparency window of SrVO3 transparent conducting oxide. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2024. 16(36): p. 47854-47865. [CrossRef]

- Sanchela, A.V., et al., Optoelectronic properties of transparent oxide semiconductor ASnO3 (A= Ba, Sr, and Ca) epitaxial films and thin film transistors. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A, 2022. 40(2). [CrossRef]

- Song, X., et al., Oxide perovskite BaSnO3: a promising high-temperature thermoelectric material for transparent conducting oxides. ACS Applied Energy Materials, 2023. 6(18): p. 9756-9763. [CrossRef]

- Ngabonziza, P. and A.P. Nono Tchiomo, Epitaxial films and devices of transparent conducting oxides: La: BaSnO3. APL Materials, 2024. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y., et al., Quasiparticle interference on cubic perovskite oxide surfaces. Physical review letters, 2017. 119(8): p. 086801. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., et al., Role of disorder and correlations in the metal-insulator transition in ultrathin SrVO 3 films. Physical Review B, 2019. 100(15): p. 155114.

- Brahlek, M., et al., Accessing a growth window for SrVO3 thin films. Applied Physics Letters, 2015. 107(14): p. 143108. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, C., et al., Growth of SrVO3 thin films by hybrid molecular beam epitaxy. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology A, 2015. 33(6): p. 061504. [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-J., et al., Realization of an atomically flat BaSnO3(001) substrate with SnO2 termination. Applied Physics Letters, 2017. 111(23): p. 231604. [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S., et al., 2× 2 R 45∘ surface reconstruction and electronic structure of BaSnO 3 film. Physical Review Materials, 2020. 4(5): p. 055003.

- Paik, H., et al., Adsorption-controlled growth of La-doped BaSnO3 by molecular-beam epitaxy. APL Materials, 2017. 5(11): p. 116107. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Epitaxial integration of high-mobility La-doped BaSnO3 thin films with silicon. APL Materials, 2019. 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., et al., Stretching epitaxial La0. 6Sr0. 4CoO3− δ for fast oxygen reduction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 2017. 121(46): p. 25651-25658.

- Cai, Z., et al., Surface electronic structure transitions at high temperature on perovskite oxides: the case of strained La0. 8Sr0. 2CoO3 thin films. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2011. 133(44): p. 17696-17704.

- Mayeshiba, T. and D. Morgan, Strain effects on oxygen migration in perovskites. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2015. 17(4): p. 2715-2721. [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, U., et al., Strain-controlled oxygen vacancy formation and ordering in CaMnO 3. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics, 2013. 88(5): p. 054111.

- Wang, Z., et al., Strain-induced defect superstructure on the SrTiO 3 (110) surface. Physical review letters, 2013. 111(5): p. 056101.

- Zhang, L., et al., Continuously Tuning Epitaxial Strains by Thermal Mismatch. ACS Nano, 2018. 12(2): p. 1306-1312. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., et al., Engineering of octahedral rotations and electronic structure in ultrathin SrIrO 3 films. Physical Review B, 2020. 101(8): p. 085101.

- Sung, H.-J., Y. Mochizuki, and F. Oba, Surface reconstruction and band alignment of nonmetallic A (II) B (IV) O 3 perovskites. Physical Review Materials, 2020. 4(4): p. 044606.

- Tao, F., Development of New Methods of Studying Catalyst and Materials Surfaces with Ambient Pressure Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2024. 58(1): p. 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A., et al., In situ quantitative analysis of electrochemical oxide film development on metal surfaces using ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Industrial alloys. Applied Surface Science, 2023. 611: p. 155714. [CrossRef]

- Frey, H., et al., Dynamic interplay between metal nanoparticles and oxide support under redox conditions. Science, 2022. 376(6596): p. 982-987. [CrossRef]

- Sit, I., H. Wu, and V.H. Grassian, Environmental aspects of oxide nanoparticles: probing oxide nanoparticle surface processes under different environmental conditions. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry, 2021. 14(1): p. 489-514. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.W., et al., Insights into heterogeneous catalysts under reaction conditions by in situ/operando electron microscopy. Advanced Energy Materials, 2022. 12(38): p. 2202097. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-P., et al., Applications of in situ electron microscopy in oxygen electrocatalysis. Microstructures, 2022. 2(1): p. N/A-N/A. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L., et al., Uncovering the nature of active sites during electrocatalytic reactions by in situ synchrotron-based spectroscopic techniques. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2022. 55(18): p. 2594-2603. [CrossRef]

- Qian, G., et al., Structural and chemical evolution in layered oxide cathodes of lithium-ion batteries revealed by synchrotron techniques. National Science Review, 2022. 9(2): p. nwab146. [CrossRef]

- Schindler, P., et al., Discovery of Stable Surfaces with Extreme Work Functions by High-Throughput Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning. Advanced Functional Materials, 2024. 34(19): p. 2401764. [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, A.G., et al., Combined high-throughput DFT and ML screening of transition metal nitrides for electrochemical CO2 reduction. ACS Catalysis, 2023. 13(13): p. 9007-9017. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., et al., Data-driven machine learning for understanding surface structures of heterogeneous catalysts. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2023. 62(9): p. e202216383. [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, A. and M.L. Grilli, Machine learning methods and sustainable development: metal oxides and multilayer metal oxides. 2022, MDPI. p. 836. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).