Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of mortality globally, with elderly individuals aged >60 years experiencing a disproportionately high burden of disease and poor outcomes[

1,

2]. Statistics from the 2019 American Heart Association (AHA) report on heart disease and stroke show that the incidence rate is typically 35%-40% among adults aged 40-60 years, averages 77%-80% in those aged 60-80 years, and xceeds 85% in individuals over 80 years old[

3]. The complex interplay of age-related metabolic changes, comorbidities (such as hypertension and diabetes), and altered lipid homeostasis in elderly CVD patients highlights the need for reliable prognostic markers to optimize risk stratification and clinical management[

4,

5].

Apolipoprotein B (APO.B) is a key structural component of atherogenic lipoproteins (including low-density lipoprotein, very-low-density lipoprotein, and intermediate-density lipoprotein) and a critical mediator of atherosclerotic pathogenesis[

6,

7]. Unlike traditional lipid parameters (e.g., low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), APO.B directly reflects the number of atherogenic lipoprotein particles, making it a more accurate indicator of atherosclerotic burden in CVD patients[

6]. In CVD cohorts, APO.B levels correlate with coronary plaque characteristics—including necrotic burden and fibrofatty burden—and exhibit associations with disease progression[

8,

9]. However, in elderly CVD patients specifically, the nature of the association between APO.B and long-term survival remains unclear, with unresolved questions about potential nonlinear patterns or threshold effects that could modify its prognostic value[

10,

11].

All-cause mortality serves as the most comprehensive endpoint for evaluating long-term prognosis in elderly CVD patients, as it integrates the cumulative impacts of CVD progression, comorbid conditions, and treatment responses[

12,

13]. In elderly populations with established CVD, all-cause mortality is influenced by multiple factors, including lipid metabolism disorders, inflammatory status, and socioeconomic factors[

14,

15,

16]. Notably, lipid-related markers often show distinct associations with mortality in this group compared to younger individuals—for example, extreme deviations in APO.B levels may correlate with altered survival risks, while traditional lipid parameters may lose predictive power after adjusting for age and comorbidities[

17]. Clarifying how APO.B relates to all-cause mortality in elderly CVD patients is therefore essential to refine prognostic assessment in this high-risk subgroup[

11,

18].

This study focuses on elderly patients with CVD aged >60 years to address two core objectives: (1) characterize the relationship between APO.B levels and all-cause mortality, with a focus on identifying potential nonlinear patterns or threshold effects that may define optimal APO.B ranges for survival; (2) explore whether this association varies across key subgroups (e.g., by gender, socioeconomic status, or lifestyle factors) to identify populations where APO.B may serve as a more robust prognostic marker. By focusing on this specific high-risk cohort, we aim to fill critical gaps in current knowledge—including the lack of clarity on APO.B’s prognostic role in elderly CVD patients—and provide evidence to inform personalized risk assessment and management strategies[

10,

11]. This work is particularly relevant given the rising global prevalence of elderly CVD patients and the need for tailored biomarkers to guide clinical decision-making.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

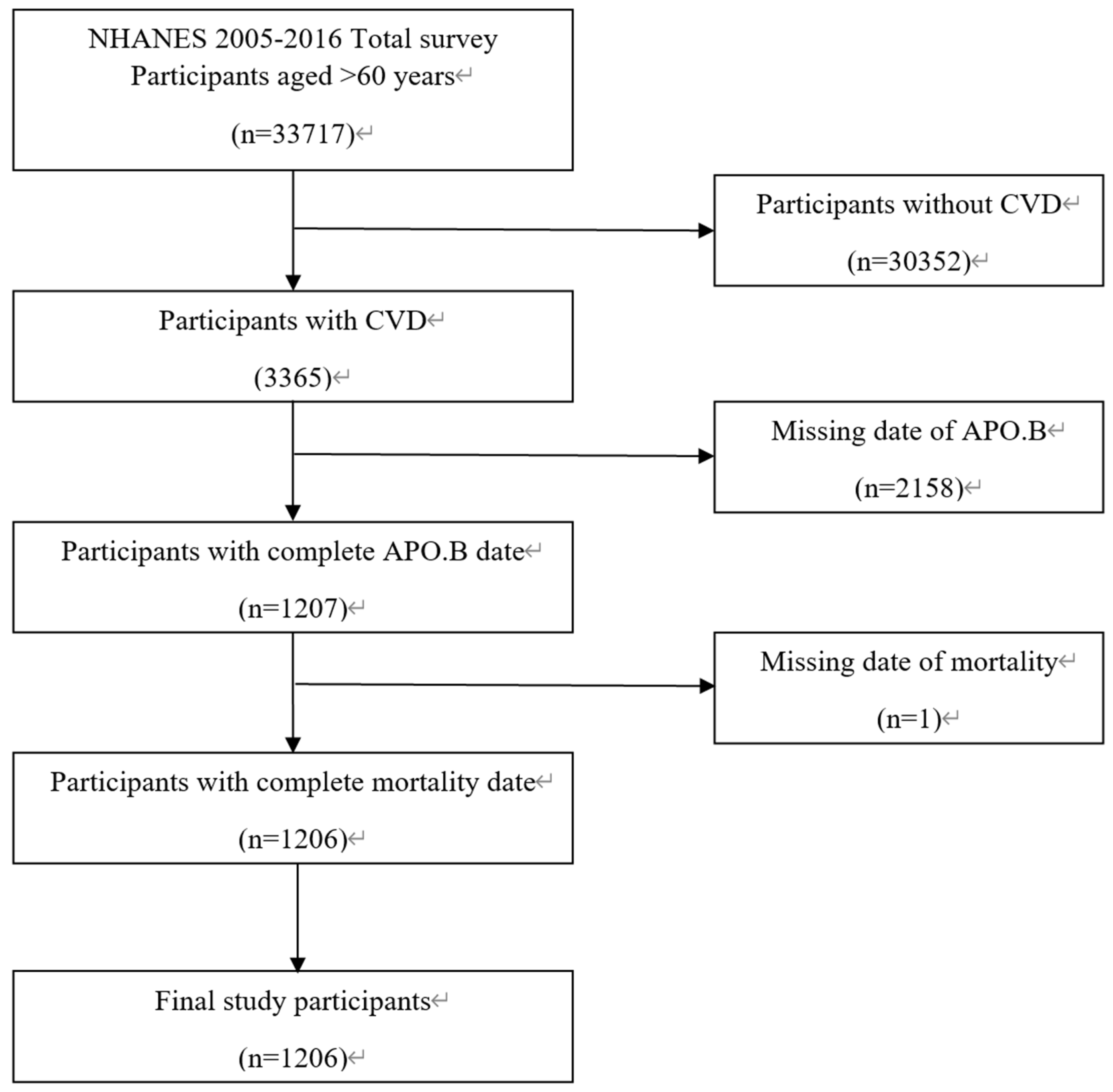

This study extracted data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2016 database[

19], with participant recruitment and selection conducted following a standardized process as detailed in the study flowchart (

Figure 1). The initial study pool included 33,717 participants aged >60 years from the NHANES 2005–2016 cohort. To ensure the validity and specificity of the study population, participants were excluded based on strict criteria: first, 30,352 individuals without a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) were excluded to focus on the target population with pre-existing CVD; second, 2158 participants with missing apolipoprotein B (APO.B) concentration data were excluded due to the core exposure variable being APO.B; finally, 1 participant with incomplete mortality status data was excluded to ensure the integrity of the outcome variable. After applying these exclusion criteria, a total of 1206 elderly patients with CVD were included in the final analysis. The inclusion criteria for the final cohort were: age >60 years at the time of the NHANES interview, confirmed diagnosis of CVD, complete APO.B measurement data, and complete follow-up records of mortality status.

Data Acquisition and Variable Definitions

All study data, including demographic information, clinical measurements, laboratory test results, and mortality follow-up data, were obtained from the NHANES 2005–2016 database, which employs standardized interview protocols, physical examination procedures, and laboratory analysis methods to ensure data reliability. The primary outcome variable was all-cause mortality (Final Mortality Status), defined as death from any cause during the follow-up period; follow-up time was calculated as person-months from the date of the NHANES interview to the date of death or the end of the follow-up period, with mortality status verified by linking to the National Death Index. The core exposure variable was APO.B, measured in mg/dL; based on the distribution of APO.B levels in the 1206 participants, the population was stratified into three tertiles: Low tertile (31.00–74.00 mg/dL, n=418), Middle tertile (75.00–97.00 mg/dL, n=419), and High tertile (98.00–220.00 mg/dL, n=369).

Covariates included in the analysis covered multiple dimensions: demographic factors such as age (years), sex (male/female), ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Other Race), marital status (Married/Living with Partner, Widowed/Divorced/Separated, Never married), poverty income ratio (Poor, Nearly poor, Middle income, High income), and educational level (Below high school, High school, Above high school); anthropometric indicators including body mass index (BMI, kg/m²), height (cm), weight (kg), and waist circumference (cm); clinical factors such as hypertension (yes/no), lymphocyte count (×10⁹/L), monocyte count (×10⁹/L), and white blood cell count (WBC, ×10⁹/L); and lifestyle factors including smoking status (Never, Former, Current), alcohol use (Never, Former, Mild, Moderate, Heavy), and total physical activity (MET/week, categorized as <600 or ≥600).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1) and EmpowerStats software, with statistical significance set at a two-tailed

P<0.05[

20,

21,

22,

23]. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics: continuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) depending on normality, while categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages (n%)[

24]. Group comparisons across APO.B tertiles were conducted using appropriate tests: one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ² test for categorical variables[

25,

26].

To evaluate the association between APO.B and all-cause mortality, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed with two levels of adjustment[

17]: Model Ⅰ adjusted for demographic and lifestyle covariates (age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, poverty income ratio, educational level, smoking status, alcohol use, total physical activity), and Model Ⅱ further adjusted for clinical and anthropometric factors (hypertension, BMI); both categorical (APO.B tertiles) and continuous (APO.B tertile variable) forms of the exposure were analyzed. Threshold effect analysis was performed using piece-wise linear regression to identify the inflection point of APO.B on all-cause mortality, with the log-likelihood ratio test used to confirm the statistical significance of the threshold effect.[

18]

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential effect modifications, stratifying the population by demographic (age, sex, ethnicity), socioeconomic (marital status, poverty income ratio, educational level), lifestyle (smoking, alcohol use, physical activity), and clinical (hypertension) factors; the APO.B Z-score was used to quantify effect sizes in each subgroup, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) reported. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted to visualize all-cause mortality differences across APO.B tertiles, with the log-rank test used to compare survival differences[

27].

Results

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of participants (N =1206).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of participants (N =1206).

| Characteristic |

Platelet Count Quartiles (×109/L) |

P-value |

T1

(n=418) |

T2

(n=419) |

T3

(n=369) |

|

| No. of participants |

418 |

419 |

369 |

|

| Age, (years) |

73.94 ± 6.20 |

72.45 ± 6.69 |

72.07 ± 7.02 |

<0.001 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) |

28.89 ± 6.26 |

30.45 ± 5.99 |

29.50 ± 6.42 |

0.002 |

| Height (cm) |

166.62 ± 9.25 |

166.54 ± 10.07 |

164.97 ± 10.33 |

0.036 |

| Weight (kg) |

80.22 ± 18.82 |

84.78 ± 19.71 |

80.78 ± 20.33 |

0.002 |

| Waist (cm) |

103.89 ± 14.08 |

107.20 ± 14.97 |

104.87 ± 14.62 |

0.006 |

| LYMPHOCYTE (×10⁹/L) |

1.81 ± 1.77 |

1.88 ± 0.71 |

2.29 ± 6.00 |

<0.001 |

| MONOCYTE(×10⁹/L) |

0.63 ± 0.24 |

0.58 ± 0.20 |

0.59 ± 0.26 |

0.013 |

| WBC (×10⁹/L) |

7.06 ± 2.67 |

7.23 ± 2.17 |

7.52 ± 6.36 |

0.236 |

| Apolipoprotein (B) (mg/dL) |

62.17 ± 8.92 |

85.45 ± 6.55 |

118.19 ± 18.48 |

<0.001 |

| Person-Months of Follow-up from NHANES Interview date (Months) |

71.10 ± 39.70 |

84.45 ± 42.42 |

82.97 ± 44.95 |

<0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Male |

271 (64.83) |

253 (60.38) |

185 (50.14) |

- |

| Female |

147 (35.17) |

166 (39.62) |

184 (49.86) |

|

| Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Non-Hispanic White |

255 (61.00) |

257 (61.34) |

222 (60.16) |

|

| Non-Hispanic Black |

71 (16.99) |

80 (19.09) |

69 (18.70) |

|

| Mexican American |

28 (6.70) |

38 (9.07) |

31 (8.40) |

|

| Other Hispanic |

34 (8.13) |

27 (6.44) |

31 (8.40) |

|

| Other Race |

30 (7.18) |

17 (4.06) |

16 (4.34) |

|

| MARITAL recoded, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.011 |

| Married/Living with Partner |

255 (61.00) |

239 (57.04) |

185 (50.14) |

|

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated |

147 (35.17) |

160 (38.19) |

173 (46.88) |

|

| Never married |

16 (3.83) |

20 (4.77) |

11 (2.98) |

|

| Poverty income ratio, n (%) |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

| Poor |

65 (15.55) |

62 (14.80) |

87 (23.58) |

|

| Nearly poor |

129 (30.86) |

139 (33.17) |

114 (30.89) |

|

| Middle income |

119 (28.47) |

95 (22.67) |

89 (24.12) |

|

| High income |

78 (18.66) |

70 (16.71) |

47 (12.74) |

|

| Missing |

27 (6.46) |

53 (12.65) |

32 (8.67) |

|

| EDU recoded, n (%) |

|

|

|

0.024 |

| Below high school |

75 (17.94) |

84 (20.05) |

61 (16.53) |

|

| High school |

162 (38.76) |

168 (40.10) |

185 (50.14) |

|

| Above high school |

180 (43.06) |

166 (39.62) |

121 (32.79) |

|

| Missing |

1 (0.24) |

1 (0.24) |

2 (0.54) |

|

| SMOKE recoded, n (%) |

|

|

|

- |

| Never |

172 (41.15) |

169 (40.33) |

173 (46.88) |

|

| Former |

193 (46.17) |

179 (42.72) |

140 (37.94) |

|

| Now |

53 (12.68) |

71 (16.95) |

56 (15.18) |

|

| Alcohol use recoded, n (%) |

|

|

|

- |

| Never |

68 (16.27) |

56 (13.37) |

67 (18.16) |

|

| Former |

149 (35.65) |

149 (35.56) |

107 (29.00) |

|

| Mild |

129 (30.86) |

121 (28.88) |

116 (31.44) |

|

| Moderate |

21 (5.02) |

28 (6.68) |

25 (6.78) |

|

| Heavy |

16 (3.83) |

29 (6.92) |

30 (8.13) |

|

| Missing |

35 (8.37) |

36 (8.59) |

24 (6.50) |

|

| Total physical activity (MET/week), n (%) |

|

|

|

- |

| <600 |

64 (15.31) |

71 (16.95) |

67 (18.16) |

|

| >=600 |

153 (36.60) |

155 (36.99) |

125 (33.88) |

|

| Missing |

201 (48.09) |

193 (46.06) |

177 (47.97) |

|

| Hypertension, n (%) |

|

|

|

- |

| No |

84 (20.10) |

70 (16.71) |

62 (16.80) |

|

| Yes |

334 (79.90) |

349 (83.29) |

307 (83.20) |

|

| Final Mortality Status, n (%) |

|

|

|

- |

| Assumed alive |

204 (48.80) |

227 (54.18) |

194 (52.57) |

|

| Assumed deceased |

214 (51.20) |

192 (45.82) |

175 (47.43) |

|

A total of 1206 elderly patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) aged >60 years were stratified into three apolipoprotein B (APO.B) tertiles (Low: 31.00–74.00 mg/dL, n=418; Middle: 75.00–97.00 mg/dL, n=419; High: 98.00–220.00 mg/dL, n=369). Significant differences across tertiles included: mean age (highest in Low tertile: 73.94±6.20 years, lowest in High tertile: 72.07±7.02 years, P<0.001); male proportion (decreasing with APO.B: 64.83% vs. 60.38% vs. 50.14%, P<0.001); APO.B levels (increasing significantly: 62.17±8.92 vs. 85.45±6.55 vs. 118.19±18.48 mg/dL, P<0.001); and mean follow-up time (shortest in Low tertile: 71.10±39.70 months, longest in Middle tertile: 84.45±42.42 months, P<0.001). Socioeconomic factors (poverty income ratio, educational level, marital status) and anthropometric indicators (body mass index, weight, waist circumference) also differed significantly (all P<0.05). Racial/ethnic distribution, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, and hypertension prevalence showed no inter-tertile differences (all P>0.05). Continuous and categorical variables were compared using ANOVA and chi-square tests, respectively.Association between APO.B and All-Cause Mortality Based on Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis

Table 2.

Relationship between APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status.

Table 2.

Relationship between APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status.

| Exposure |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

| Apo B (Tertile) |

HR(95% CI) |

P-value |

HR(95% CI) |

P-value |

HR(95% CI) |

P-value |

| Low |

ref |

ref |

ref |

| Middle |

0.72 (0.59, 0.88) |

0.0010 |

0.75 (0.61, 0.92) |

0.0049 |

0.75 (0.61, 0.92) |

0.0068 |

| High |

0.75 (0.62, 0.92) |

0.0060 |

0.84 (0.68, 1.04) |

0.1093 |

0.86 (0.69, 1.07) |

0.1741 |

|

P for trend |

0.0054 |

0.0894 |

0.1431 |

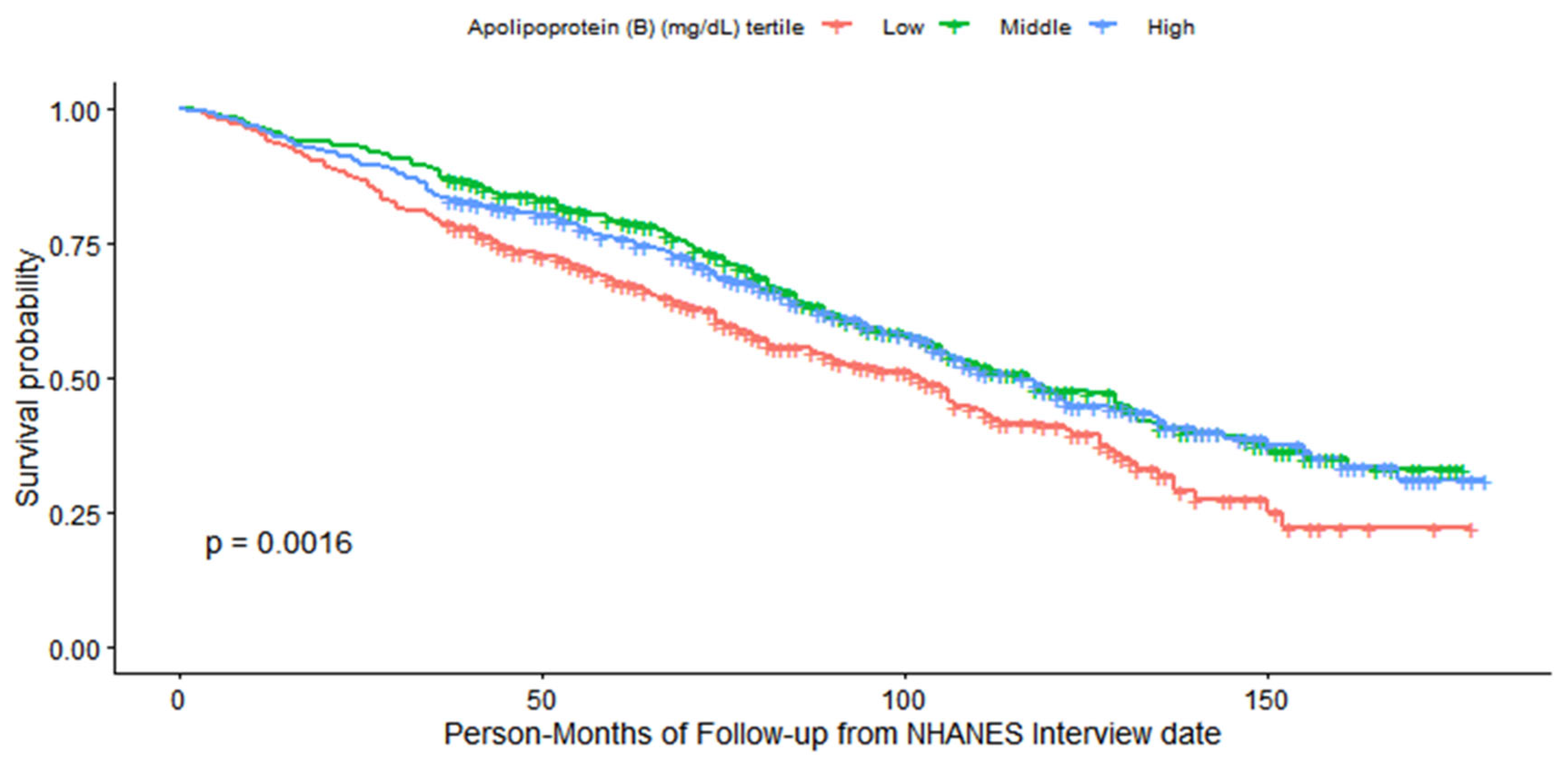

Caption:Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality stratified by apolipoprotein B (APO.B) tertiles in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD). Tertile definitions: Low (31.00–74.00 mg/dL, n = 418), Middle (75.00–97.00 mg/dL, n = 419), and High (98.00–220.00 mg/dL, n = 369). The log-rank test P value is 0.0016. The “Number at risk” panel indicates the number of participants remaining in each tertile at specified follow-up time points (person-months from NHANES interview date). The “Number of censoring” panel displays the number of censored events over follow-up time. All participants were ≥60 years of age and from the NHANES 2005–2016 database.

Multivariate Cox regression analyses revealed a significant association between apolipoprotein B (APO.B) tertiles and all-cause mortality, which weakened after adjusting for confounding factors. In the crude model, compared with the Low APO.B tertile (31.00–74.00 mg/dL), the Middle tertile (75.00–97.00 mg/dL) and High tertile (98.00–220.00 mg/dL) were associated with lower mortality risk (HR=0.72, 95%CI:0.59–0.88, P=0.0010; HR=0.75, 95%CI:0.62–0.92, P=0.0060, respectively). When adjusted for demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates (Model Ⅰ and Model Ⅱ), the protective effect of higher APO.B persisted only in the Middle tertile (HR=0.75, 95%CI:0.61–0.92, P=0.0049 for Model Ⅰ; HR=0.75, 95%CI:0.61–0.92, P=0.0068 for Model Ⅱ), while the High tertile showed no statistically significant association (HR=0.84, 95%CI:0.68–1.04, P=0.1093 for Model Ⅰ; HR=0.86, 95%CI:0.69–1.07, P=0.1741 for Model Ⅱ). Similarly, the continuous APO.B tertile variable was significantly associated with reduced mortality risk in the crude model (HR=0.86, 95%CI:0.78–0.96, P=0.0054), but this association became borderline significant in Model Ⅰ (HR=0.91, 95%CI:0.82–1.01, P=0.0894) and non-significant in Model Ⅱ (HR=0.92, 95%CI:0.82–1.03, P=0.1431).

To intuitively characterize all-cause mortality disparities across APO.B tertiles, a combined Kaplan-Meier survival curve integrating three key components (survival trajectory, number at risk, and number of censored cases) was constructed, with the log-rank test used to evaluate intergroup survival differences. As depicted in

Figure 2, there was a statistically significant distinction in survival probabilities among the three APO.B tertile groups (

P=0.0016 by log-rank test). Throughout the entire follow-up period, participants in the middle APO.B tertile (75.00–97.00 mg/dL) maintained the highest survival probability, whereas those in the low tertile (31.00–74.00 mg/dL) exhibited the poorest survival outcomes. The high APO.B tertile (98.00–220.00 mg/dL) presented intermediate survival trends between the low and middle tertiles. Notably, the embedded subplots displaying the “Number at risk” and “Number of censoring” at sequential follow-up time points confirmed adequate completeness of the follow-up process, with no excessive attrition that could bias the results. This unadjusted survival pattern—consistent with the subsequent multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression findings—further validates the protective effect of moderate APO.B levels in elderly patients with established cardiovascular disease, laying a visual foundation for the quantitative association analyses described below.

Threshold Effect of APO.B on All-Cause Mortality

Table 3.

Threshold Effect Analysis of APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status using Piece-wise Linear Regression.

Table 3.

Threshold Effect Analysis of APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status using Piece-wise Linear Regression.

| ApoB |

HR (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Fitting by the standard linear mode |

1.00 (0.99, 1.00) |

0.0461 |

Fitting by the two-piecewise linear

model |

|

| Inflection point |

83.0 |

| ApoB < 83(mg/dL) |

0.63 (0.51, 0.79) |

< 0.0001 |

| ApoB ≥ 83(mg/dL) |

1.10 (0.96, 1.26) |

0.1881 |

| Log likelihood ration |

<0.0001 |

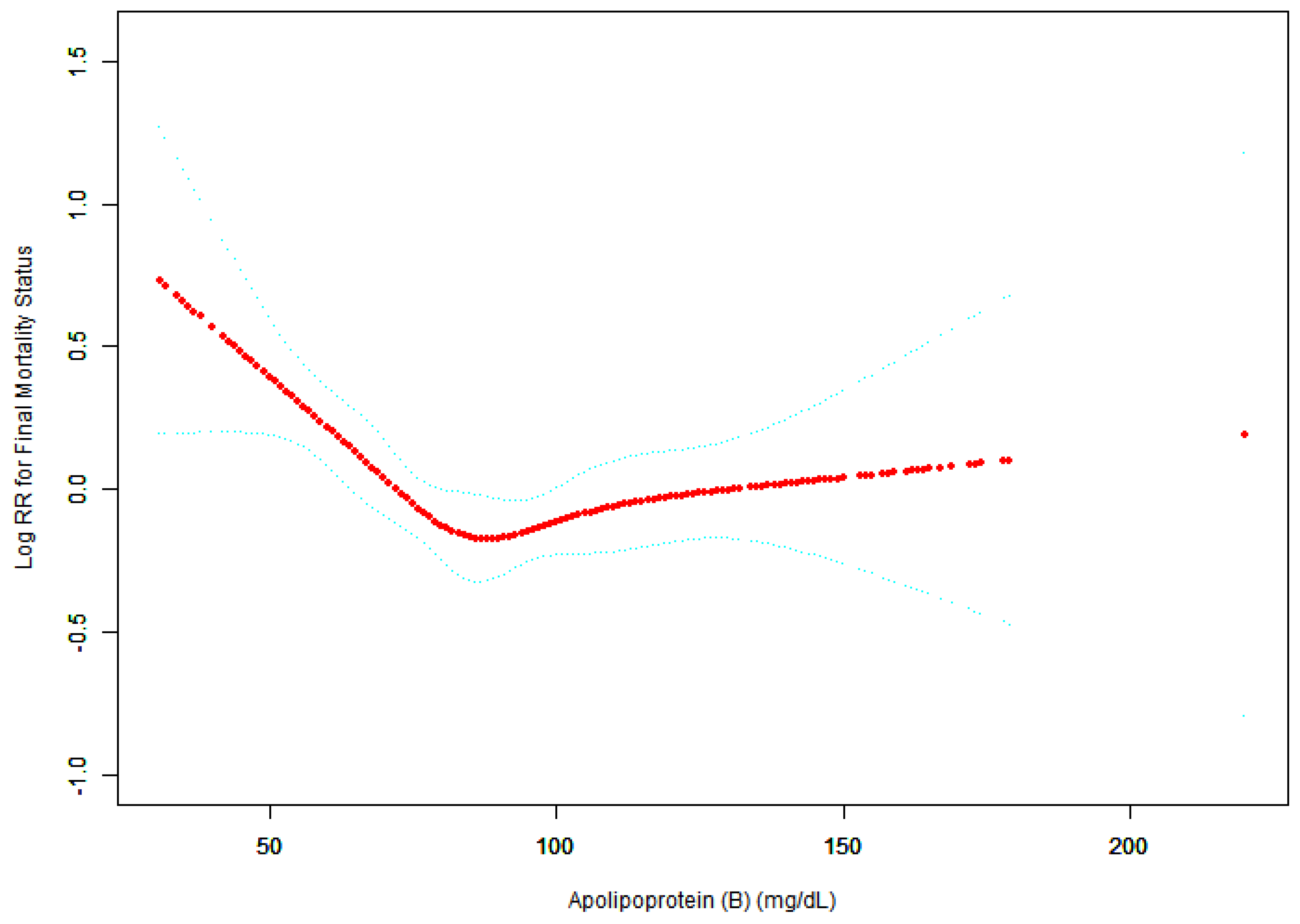

Figure 3.

Association between APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status.

Figure 3.

Association between APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status.

A threshold, nonlinear association between APO.B (mg/dL) and Final Mortality Status was found in a generalized additive model (GAM). Solid rad line represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit. All adjusted for Sex; Ethnicity; MARITAL recoded; Poverty income ratio; EDU recoded; SMOKE recoded; Alcohol use recoded; Total physical activity (MET/week); Hypertension; Body Mass Index (kg/m2).

Piece-wise linear regression analysis (adjusted for demographic, lifestyle, and clinical covariates) identified a significant threshold effect of apolipoprotein B (APO.B) on all-cause mortality, with an inflection point at 83 mg/dL. Below this threshold, each 1 mg/dL increase in APO.B was associated with a significantly reduced mortality risk (OR=0.98, 95%CI:0.97–0.99, P<0.0001). In contrast, above 83 mg/dL, the association between APO.B and mortality risk became non-significant (OR=1.00, 95%CI:1.00–1.01, P=0.1877). The difference in effect sizes between the two segments was statistically significant (OR=1.02, 95%CI:1.01–1.03, P=0.0004), confirming a distinct nonlinear relationship between APO.B and all-cause mortality in elderly CVD patients.

Subgroup Analysis of APO.B on All-Cause Mortality

Table 4.

Effect size of APO.B (mg/dL) on Final Mortality Status in prespecified and exploratory subgroups in Each Subgroup.

Table 4.

Effect size of APO.B (mg/dL) on Final Mortality Status in prespecified and exploratory subgroups in Each Subgroup.

| Characteristic |

No. of participants |

Final Mortality Status,HR (95%CI) |

P -value |

| Sex |

|

|

|

| Male |

709 |

0.85 (0.75, 0.97) |

0.0145 |

| Female |

497 |

0.88 (0.77, 1.00) |

0.0523 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

| Non-Hispanic White |

734 |

0.88 (0.79, 0.98) |

0.0200 |

| Non-Hispanic Black |

220 |

0.87 (0.70, 1.08) |

0.2032 |

| Mexican American |

97 |

0.88 (0.64, 1.21) |

0.4196 |

| Other Hispanic |

92 |

0.60 (0.37, 1.00) |

0.0494 |

| Other Race |

63 |

0.80 (0.44, 1.47) |

0.4719 |

| MARITAL recoded |

|

|

|

| Married/Living with Partner |

679 |

0.84 (0.73, 0.97) |

0.0191 |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated |

480 |

0.81 (0.71, 0.91) |

0.0005 |

| Never married |

47 |

0.95 (0.58, 1.55) |

0.8226 |

| Poverty income ratio |

|

|

|

| Poor |

214 |

0.81 (0.65, 1.00) |

0.0498 |

| Nearly poor |

382 |

0.85 (0.73, 0.98) |

0.0239 |

| Middle income |

303 |

0.89 (0.74, 1.06) |

0.1962 |

| High income |

195 |

0.89 (0.67, 1.18) |

0.4297 |

| Missing |

112 |

0.82 (0.58, 1.16) |

0.2595 |

| EDU recoded |

|

|

|

| Below high school |

220 |

0.84 (0.69, 1.01) |

0.0612 |

| High school |

515 |

0.84 (0.74, 0.96) |

0.0120 |

| Above high school |

467 |

0.84 (0.71, 1.00) |

0.0482 |

| Missing |

4 |

1.70 (0.47, 6.18) |

0.4230 |

| SMOKE recoded |

|

|

|

| Never |

514 |

0.90 (0.78, 1.03) |

0.1316 |

| Former |

512 |

0.87 (0.76, 1.00) |

0.0468 |

| Now |

180 |

0.75 (0.59, 0.96) |

0.0234 |

| Alcohol use recoded |

|

|

|

| Never |

191 |

1.03 (0.85, 1.25) |

0.7790 |

| Former |

405 |

0.88 (0.76, 1.02) |

0.0800 |

| Mild |

366 |

0.81 (0.67, 0.98) |

0.0322 |

| Moderate |

74 |

0.98 (0.63, 1.52) |

0.9283 |

| Heavy |

75 |

1.05 (0.76, 1.46) |

0.7627 |

| Missing |

95 |

0.63 (0.47, 0.85) |

0.0023 |

| Total physical activity (MET/week) |

|

|

|

| <600 |

202 |

0.76 (0.61, 0.96) |

0.0210 |

| >=600 |

433 |

0.95 (0.80, 1.12) |

0.5403 |

| Missing |

571 |

0.83 (0.74, 0.94) |

0.0031 |

| Hypertension |

|

|

|

| No |

216 |

0.84 (0.68, 1.02) |

0.0830 |

| Yes |

990 |

0.86 (0.78, 0.95) |

0.0043 |

Subgroup analyses revealed consistent protective effects of apolipoprotein B (APO.B) Z-score on all-cause mortality across multiple demographic, lifestyle, and clinical subgroups, with varying statistical significance. Notably, significant associations were observed in males (OR=0.85, 95%CI:0.75–0.97, P=0.0145), non-Hispanic Whites (OR=0.88, 95%CI:0.79–0.98, P=0.0200), other Hispanics (OR=0.60, 95%CI:0.37–1.00, P=0.0494), married/living with partner (OR=0.84, 95%CI:0.73–0.97, P=0.0191), widowed/divorced/separated (OR=0.81, 95%CI:0.71–0.91, P=0.0005), poor (OR=0.81, 95%CI:0.65–1.00, P=0.0498), nearly poor (OR=0.85, 95%CI:0.73–0.98, P=0.0239), high school graduates (OR=0.84, 95%CI:0.74–0.96, P=0.0120), above high school education (OR=0.84, 95%CI:0.71–1.00, P=0.0482), former smokers (OR=0.87, 95%CI:0.76–1.00, P=0.0468), current smokers (OR=0.75, 95%CI:0.59–0.96, P=0.0234), mild alcohol users (OR=0.81, 95%CI:0.67–0.98, P=0.0322), participants with total physical activity <600 MET/week (OR=0.76, 95%CI:0.61–0.96, P=0.0210), those with hypertension (OR=0.86, 95%CI:0.78–0.95, P=0.0043), and specific body size subgroups (e.g., height middle tertile: OR=0.78, 95%CI:0.66–0.93, P=0.0046; waist circumference highest tertile: OR=0.81, 95%CI:0.66–0.98, P=0.0333). No significant associations were found in subgroups such as never drinkers, moderate/heavy alcohol users, and participants with total physical activity ≥600 MET/week (all P>0.05), indicating potential effect modifications by lifestyle factors.

Discussion

The present study systematically explored the association between apolipoprotein B (APO.B) and all-cause mortality in elderly patients with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) aged >60 years, leveraging data from the NHANES 2005–2016 database. Core findings revealed a nonlinear relationship between APO.B levels and all-cause mortality, with a critical threshold at 83 mg/dL: below this threshold, each 1 mg/dL increase in APO.B was associated with a reduced mortality risk, while no significant association was observed above the threshold. Additionally, the middle APO.B tertile (75.00–97.00 mg/dL) consistently exhibited a protective effect against all-cause mortality after adjusting for confounding factors, and subgroup analyses identified demographic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors that modified this association. These results extend current understanding of APO.B’s prognostic value in elderly CVD patients and provide actionable insights for clinical management.

Core Findings in Context of Existing Evidence

APO.B is widely recognized as a robust marker of atherogenic lipoprotein particle number, with established associations with CVD progression and mortality in general populations[

28]. However, studies focusing on elderly CVD patients—who exhibit age-related metabolic alterations, comorbidity complexity, and distinct lipid homeostasis—remain limited and inconsistent. Previous research has reported either linear positive associations between APO.B and mortality or no significant correlation, but few have explored nonlinear patterns or threshold effects. Our identification of an 83 mg/dL threshold fills this gap, highlighting that APO.B’s prognostic role is not uniform across concentration ranges in this high-risk subgroup[

18,

29,

30]. The protective effect of moderate APO.B levels (middle tertile) aligns with emerging evidence that extremely low APO.B may indicate malnutrition, frailty, or impaired lipoprotein metabolism in elderly individuals—conditions that independently increase mortality risk[

31,

32]. In contrast, the lack of significant association in the high APO.B tertile may reflect the competing risks of advanced CVD, comorbidities, and age-related physiological decline, which could attenuate the incremental risk of elevated APO.B[

27,

33].

Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Nonlinear Association

The nonlinear relationship between APO.B and all-cause mortality in elderly CVD patients may be explained by multiple interconnected mechanisms. First, APO.B directly reflects the number of atherogenic lipoproteins (LDL, VLDL, IDL), and moderate levels may maintain a balance between preventing excessive atherosclerotic plaque accumulation and avoiding the adverse effects of insufficient lipoprotein function[

6,

18,

34]. In elderly individuals, extremely low APO.B could be a surrogate for reduced hepatic lipoprotein synthesis, malnutrition, or sarcopenia—all of which are linked to increased mortality in CVD populations[

35]. Second, age-related declines in lipoprotein clearance capacity (e.g., reduced LDL receptor activity) may alter the pathogenicity of elevated APO.B: in younger populations, high APO.B drives plaque progression, but in elderly patients with pre-existing CVD, the cumulative burden of disease may overshadow the incremental risk of further APO.B elevation[

27,

36]. Third, the threshold effect (83 mg/dL) may represent an “optimal range” for elderly CVD patients, where APO.B levels are sufficient to support essential lipid transport without promoting excessive atherogenesis or inducing malnutrition-related risks[

9,

27,

28,

32].

Interpretation of Subgroup Differences

Subgroup analyses revealed that the protective effect of APO.B was more pronounced in specific populations, including males, non-Hispanic Whites, former/current smokers, mild alcohol users, and those with total physical activity <600 MET/week. These differences may reflect variations in lipid metabolism, lifestyle-related confounders, and disease severity across subgroups[

27]. For example, males exhibit higher baseline atherogenic lipoprotein levels and distinct hormonal influences on lipid homeostasis, making APO.B a more sensitive prognostic marker. Similarly, individuals with lower physical activity rely more on lipid metabolic balance to maintain vascular health, whereas high physical activity may mitigate the impact of APO.B through improved endothelial function and lipoprotein clearance[

37]. The lack of significant associations in never drinkers, moderate/heavy alcohol users, and those with high physical activity suggests that these lifestyle factors may modify APO.B’s biological effects—either by altering lipoprotein composition (e.g., alcohol-induced changes in VLDL metabolism) or by providing independent cardiovascular protection[

27].

Study Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the observational design of NHANES precludes causal inference, and residual confounding (e.g., detailed CVD subtypes, lipid-lowering medication use, dietary patterns) may affect the observed associations. Second, APO.B was measured only at baseline, and dynamic changes in APO.B levels during follow-up— which could influence mortality risk—were not captured. Third, subgroup analyses may be subject to multiple testing bias, and some subgroups (e.g., specific ethnic minorities) had small sample sizes, limiting the generalizability of subgroup-specific findings. Fourth, the study lacked data on other lipid-related markers (e.g., LDL particle size, remnant cholesterol), which could interact with APO.B to affect mortality risk.

Application of APO.B Threshold in Lipid Management and Prospective Research Priorities for Elderly CVD Patients

Despite these limitations, the present study provides actionable references for lipid management in elderly patients with established cardiovascular disease (CVD), based on the identified APO.B-related findings[

38]. The critical threshold of 83 mg/dL for APO.B offers a concrete basis for personalized intervention: in patients with APO.B levels below 83 mg/dL, overly aggressive lipid-lowering strategies should be avoided to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes such as malnutrition or frailty, and clinical efforts should instead focus on controlling modifiable risk factors like hypertension and chronic inflammation[

27,

39]. For patients in the middle APO.B tertile (75.00–97.00 mg/dL), maintaining existing lipid management regimens may help preserve the protective effect against all-cause mortality observed in this study[

40]. For those in the high APO.B tertile (98.00–220.00 mg/dL), risk assessment should extend beyond APO.B alone, incorporating evaluations of coronary plaque stability, comorbidity control, and functional status to formulate targeted care plans[

41]. Additionally, subgroup-specific results—including the more prominent association of APO.B with mortality in males and patients with total physical activity <600 MET/week—suggest that these populations may require more frequent APO.B monitoring to optimize risk stratification in clinical practice[

42].

Several targeted research directions are warranted to address gaps in the current study. First, validation of the 83 mg/dL APO.B threshold in independent cohorts of elderly CVD patients—particularly non-Western populations—is necessary, as the current analysis relies on data from the U.S.-based NHANES database, which may limit generalizability. Second, mechanistic investigations should explore the biological links between extremely low APO.B levels and increased mortality, such as the potential associations with nutritional deficiencies, sarcopenia, or impaired lipoprotein transport function in elderly CVD patients. Third, prospective interventional studies could evaluate whether targeting APO.B to the optimal range (75.00–97.00 mg/dL) improves long-term survival in this high-risk group, providing evidence to support updates to lipid management guidelines for elderly CVD patients. Fourth, integrating APO.B with other biomarkers (e.g., C-reactive protein for inflammation, frailty assessment indices) may enhance the accuracy of mortality risk prediction, helping to identify elderly CVD patients at the highest risk and allocate clinical resources more effectively.

Conclusions

This study confirms a nonlinear association between apolipoprotein B (APO.B) and all-cause mortality in elderly patients with established cardiovascular disease, along with a protective effect of moderate APO.B levels and demographic/lifestyle modifiers of this association, providing targeted references for clinical lipid management in this high-risk population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and B.Y.; methodology, D.L.; software, D.L.; validation, D.L., M.Y. and S.S.; formal analysis, D.L.; investigation, D.L.; resources, B.Y.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L., C.L., and Y.Z.; visualization, D.L.; supervision, B.Y.; project administration, B.Y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of publicly available and de-identified data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which ensures the protection of participant privacy and confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as all NHANES data used in this study are publicly available, de-identified, and comply with ethical standards for secondary data analysis.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

IThe authors would like to thank the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) for providing access to the NHANES database. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1, 2025) for language polishing and technical editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the scientific accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cui Y, Lei S, Xia Y, Yang F (2025) The trajectory of intrinsic capacity and its related factors among elderly Chinese patients with cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 16:1539982. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Tan S, Zhou Z, Zhao M, Wang Y, Li Q, Zheng Y, Shi J (2025) Predicting Short-Term Risk of Cardiovascular Events in the Elderly Population: A Retrospective Study in Shanghai, China. Clin Interv Aging, 20:825-836. [CrossRef]

- Qu C, Liao S, Zhang J, Cao H, Zhang H, Zhang N, Yan L, Cui G, Luo P, Zhang Q, Cheng Q (2024) Burden of cardiovascular disease among elderly: based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes, 10:143-153. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Ren E, Guo C, Peng Y, Chen H, Li W (2025) Development and validation of a predictive model for frailty risk in older adults with cardiovascular-metabolic comorbidities. Front Public Health, 13:1561845. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Liu Y, Sun G, Zhou J, Luo D, Mao G, Xu W (2025) The predictive value of hsCRP/HDL-C ratio for cardiometabolic multimorbidity in middle-aged and elderly people: evidence from a large national cohort study. Front Nutr, 12:1580904. [CrossRef]

- Wong ND, Budoff MJ, Ferdinand K, Graham IM, Michos ED, Reddy T, Shapiro MD, Toth PP (2022) Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: An American Society for Preventive Cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol, 10:100335. [CrossRef]

- Fischer K, Kassem L (2023) Apolipoprotein B: An essential cholesterol metric for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm, 80:83-86. [CrossRef]

- Wu H, Pang M, Chen H, Zhuang K, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Ding X (2025) Serum proteomic profiling reveals potential predictive indicators for coronary artery calcification in stable ischemic heart disease. J Mol Histol, 56:110. [CrossRef]

- Hagström E, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Danchin N, Diaz R, Goodman SG, Harrington RA, Jukema JW, Liberopoulos E, Marx N, Mcginniss J, Manvelian G, Pordy R, Scemama M, White HD, Zeiher AM, Schwartz GG (2022) Apolipoprotein B, Residual Cardiovascular Risk After Acute Coronary Syndrome, and Effects of Alirocumab. Circulation, 146:657-672. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Ni J, Chen Z (2022) Apolipoprotein B Displays Superior Predictive Value Than Other Lipids for Long-Term Prognosis in Coronary Atherosclerosis Patients and Particular Subpopulations: A Retrospective Study. Clin Ther, 44:1071-1092. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Wang B, Mai Z, Yu S, Zhou Z, Lu H, Lai W, Li Q, Yang Y, Deng J, Tan N, Chen J, Liu J, Liu Y, Chen S (2022) Paradoxical Association Between Baseline Apolipoprotein B and Prognosis in Coronary Artery Disease: A 36,460 Chinese Cohort Study. Front Cardiovasc Med, 9:822626. [CrossRef]

- Su D, An Z, Chen L, Chen X, Wu W, Cui Y, Cheng Y, Shi S (2024) Association of triglyceride-glucose index, low and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in generally Chinese elderly: a retrospective cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 15:1422086. [CrossRef]

- Sarma V, Jin Y, Bandinelli S, Talegawkar SA, Ferrucci L, Tanaka T (2025) Cardiovascular health assessed using Life's Essential 8 is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among community-dwelling older men and women in the InCHIANTI study. Front Public Health, 13:1570463. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Peng K, Xu W, Huang X, Liu X, Li Y, Lu J, Yang Y, Chen B, Shi Y, Han G, Zhang X, Cui J, Song L, Tian A, Runsi W, Wang C, Tian Y, Wu Y, Lin C, Peng W, Li X, Hu S (2025) Cardiovascular disease-specific and all-cause mortality across socioeconomic status and lifestyles among patients with established cardiovascular disease in communities of China: data from a national population-based cohort. Heart, 111:1092-1100. [CrossRef]

- Yang M, Miao S, Hu W, Yan J (2024) Association between the dietary inflammatory index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 34:1046-1053. [CrossRef]

- Engell AE, Bathum L, Siersma V, Andersen CL, Lind BS, Jørgensen HL (2025) Elevated remnant cholesterol and triglycerides are predictors of increased total mortality in a primary health care population of 327,347 patients. Lipids Health Dis, 24:189. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K, Wei C, Shao Y, Wang L, Zhao Z, Yin S, Tang X, Li Y, Gou Z (2024) Association of non-HDL-C/APO.B ratio with long-term mortality in the general population: A cohort study. Heliyon, 10:e28155. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Yuan Y, Dong X, Xier Z, Ma L, Peng H, Li G, Yang Y (2025) Low apolipoprotein B and LDL-cholesterol are associated with the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a prospective cohort. Ann Med, 57:2529565. [CrossRef]

- Suchak T, Aliu AE, Harrison C, Zwiggelaar R, Geifman N, Spick M (2025) Explosion of formulaic research articles, including inappropriate study designs and false discoveries, based on the NHANES US national health database. PLoS Biol, 23:e3003152. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Li J, Cao Y, Bao Z, Dong X, Zhang P, Yan J, Liu Y, Guo Y, Zeng X (2024) Association of different inflammatory indices with risk of early natural menopause: a cross-sectional analysis of the NHANES 2013-2018. Front Med (Lausanne), 11:1490194. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Li J, Li Y, Guan Y (2025) Dietary sodium intake and all-cause mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: an NHANES analysis (2003-2018). Front Nutr, 12:1518697. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Liu Y, Qiao H, Ma Q, Zhao B, Wu Q, Li H (2025) Mediating role of triglyceride glucose-related index in the associations of composite dietary antioxidant index with cardiovascular disease and mortality in older adults with hypertension: a national cohort study. Front Nutr, 12:1574876. [CrossRef]

- Su X, Rao H, Zhao C, Zhang X, Li D (2024) The association between the metabolic score for insulin resistance and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 15:1479980. [CrossRef]

- Cheng H, Huang W, Huang X, Miao W, Huang Y, Hu Y (2024) The triglyceride glucose index predicts short-term mortality in non-diabetic patients with acute heart failure. Adv Clin Exp Med, 33:103-110. [CrossRef]

- Meng J, Yang W, Chen Z, Pei C, Peng X, Li C, Li F (2024) ApoA1, APO.B, ApoA1/B for Pathogenic Prediction of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Complicated by Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 19:309-317. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Limón P, Muralidharan J, Gomez-Perez AM, Murri M, Vioque J, Corella D, Fitó M, Vidal J, Salas-Salvadó J, Torres-Collado L, Coltell O, Atzeni A, Castañer O, Bulló M, Bernal-López MR, Moreno-Indias I, Tinahones FJ (2024) Physical activity shifts gut microbiota structure in aged subjects with overweight/obesity and metabolic syndrome. Biol Sport, 41:47-60. [CrossRef]

- Sniderman AD, Dufresne L, Pencina KM, Bilgic S, Thanassoulis G, Pencina MJ (2024) Discordance among APO.B, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides: implications for cardiovascular prevention. Eur Heart J, 45:2410-2418. [CrossRef]

- Katsi V, Argyriou N, Fragoulis C, Tsioufis K (2025) The Role of Non-HDL Cholesterol and Apolipoprotein B in Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Review. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu YX, Chen J, Liu C, Maitiyasen M, Hou X, Li J, Yi J (2025) Preoperative lipid levels and prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective age-stratified study. Sci Prog, 108:368504251352375. [CrossRef]

- Snyder C, Beitelshees AL, Chowdhury D (2023) Familial Hyperlipidemia Caused by Apolipoprotein B Mutation in the Pediatric Amish Population: A Mini Review. Interv Cardiol (Lond), 15:433-437.

- Li S, Xie X, Zeng X, Wang S, Lan J (2024) Serum apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A-I ratio predicts mortality in patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail, 11:99-111. [CrossRef]

- Agoons DD, Agoons BB (2025) Apolipoprotein B and Glycemic Indices in Normoglycemic Adults: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2016. Cureus, 17:e85656. [CrossRef]

- Glavinovic T, Thanassoulis G, De Graaf J, Couture P, Hegele RA, Sniderman AD (2022) Physiological Bases for the Superiority of Apolipoprotein B Over Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol as a Marker of Cardiovascular Risk. J Am Heart Assoc, 11:e025858. [CrossRef]

- Sarraju A, Brennan D, Hayden K, Stronczek A, Goldberg AC, Michos ED, Mcguire DK, Mason D, Tercek G, Nicholls SJ, Kling D, Neild AL, Kastelein J, Davidson M, Ditmarsch M, Nissen SE (2025) Fixed-dose combination of obicetrapib and ezetimibe for LDL cholesterol reduction (TANDEM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 405:1757-1768. [CrossRef]

- Tan LF, Sia CH, Merchant RA (2025) Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in cardiovascular disease: a comprehensive review. Singapore Med J. [CrossRef]

- Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG (2025) Lipoprotein(a) Cardiovascular Risk Explained by LDL Cholesterol, Non-HDL Cholesterol, APO.B, or hsCRP Is Minimal. J Am Coll Cardiol, 85:2046-2051. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Fu H, Xu H, Yang H, Min X, Wu W, Liu Z, Li D, Dong Y, Chen J (2025) Non-traditional lipid biomarkers in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological mechanisms and strategies to address residual risk. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 16:1576602. [CrossRef]

- Marston NA, Giugliano RP, Melloni GEM, Park JG, Morrill V, Blazing MA, Ference B, Stein E, Stroes ES, Braunwald E, Ellinor PT, Lubitz SA, Ruff CT, Sabatine MS (2022) Association of Apolipoprotein B-Containing Lipoproteins and Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Individuals With and Without Atherosclerosis: Distinguishing Between Particle Concentration, Type, and Content. JAMA Cardiol, 7:250-256. [CrossRef]

- Elshazly MB, Quispe R (2022) The Lower the APO.B, the Better: Now, How Does APO.B Fit in the Upcoming Era of Targeted Therapeutics? Circulation, 146:673-675. [CrossRef]

- Toth PP, Banach M (2024) It is time to address the contribution of cholesterol in all APO.B-containing lipoproteins to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J Open, 4:oeae057. [CrossRef]

- Yu M, Yang Y, Dong SL, Zhao C, Yang F, Yuan YF, Liao YH, He SL, Liu K, Wei F, Jia HB, Yu B, Cheng X (2024) Effect of Colchicine on Coronary Plaque Stability in Acute Coronary Syndrome as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography: The COLOCT Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation, 150:981-993. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wu Q, Li Z, Xiao Y, Wei L (2025) Prognostic Value of Apolipoprotein E in Predicting One-year Mortality in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis, 20:1639-1650. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).