Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

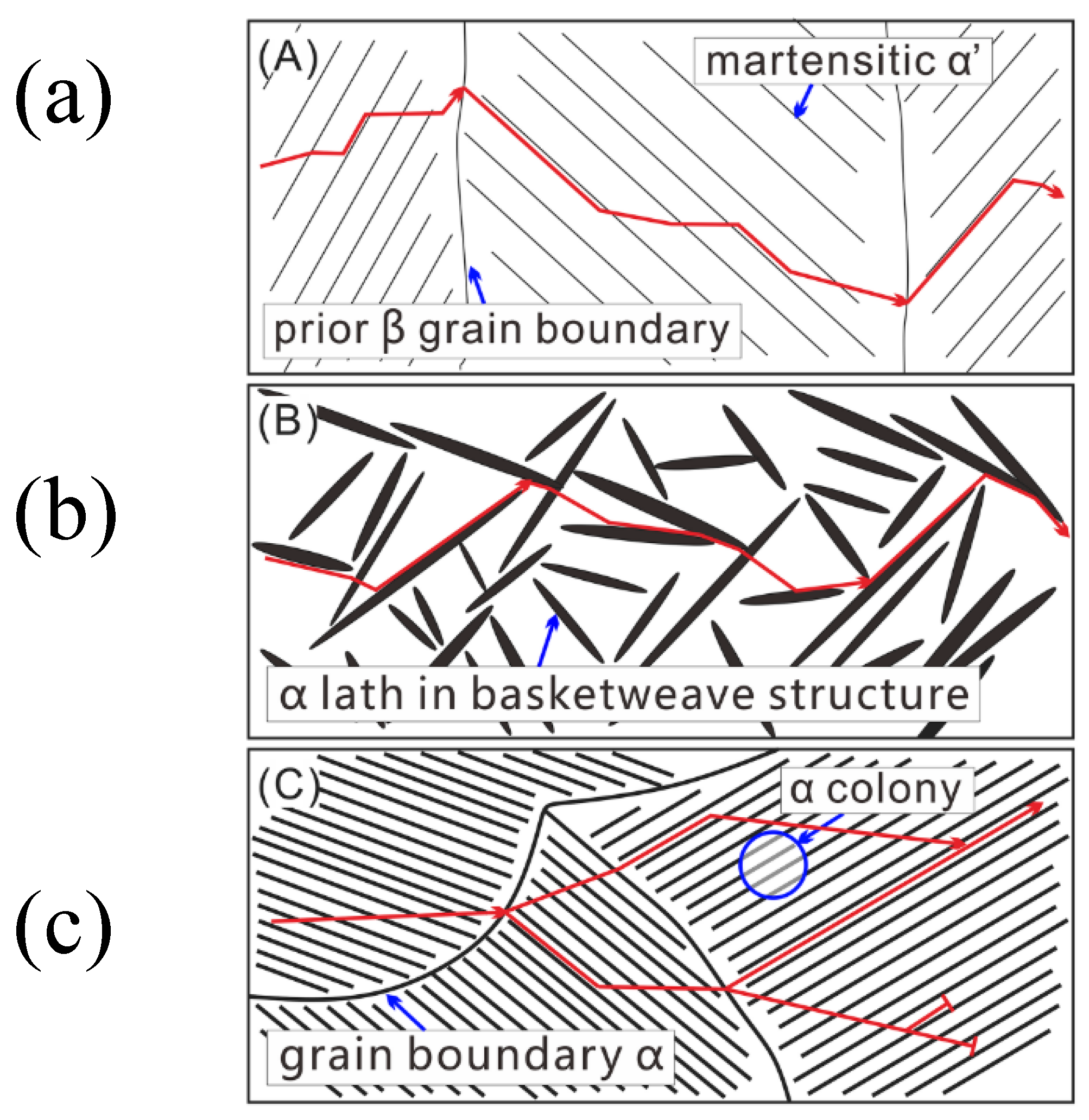

2. Microstructure of AM Ti64

- (a)

- Stress relieving (480-800 °C): Stress-relieving treatments reduces residual stresses in the AM build while causing minimal coarsening of the α′ martensite. It increases ductility and dimensional stability while largely preserving the as-built microstructural features [38].

- (b)

- Super-transus heat treatment (β-annealing): In this heat treatment procedure, Ti64 is heated 20–200 °C above its β-transus temperature (995 °C [29,35,39]) to fully convert the microstructure to the β phase. Controlled cooling then produces equiaxed, recrystallized prior-β grains, reducing build-direction texture and improving mechanical isotropy[35].

- (c)

- Sub-transus treatment (recrystallization annealing): Heating Ti64 to ~800–950 °C (within the α+β two-phase field) [40] triggers recrystallization of both hcp α and bcc β grains. Controlled soak times and cooling rates refine grain size, adjust α/β phase fractions, and enable a tailored balance of strength and ductility.

- (d)

- Solution treatment and aging (STA): Solution treatment is conducted just below or above the β-transus (995 °C) to dissolve metastable α′ and homogenize the β matrix. After quenching or air cooling, aging at 400–750 °C precipitates fine α phases, which strengthen the alloy while retaining ductility [38].

- (e)

- Hot isostatic pressing (HIP) (800–1200 °C, 100–200 MPa): HIP closes internal pores and homogenizes the microstructure in AM Ti64 [41]. It is classified into super-transus HIP (1000–1200 °C) and sub-transus HIP (800–950 °C), with further distinctions based on pressure, hold time, and cooling rate, each influencing the microstructure and mechanical behavior.

3. FCG Behavior of AM Ti64

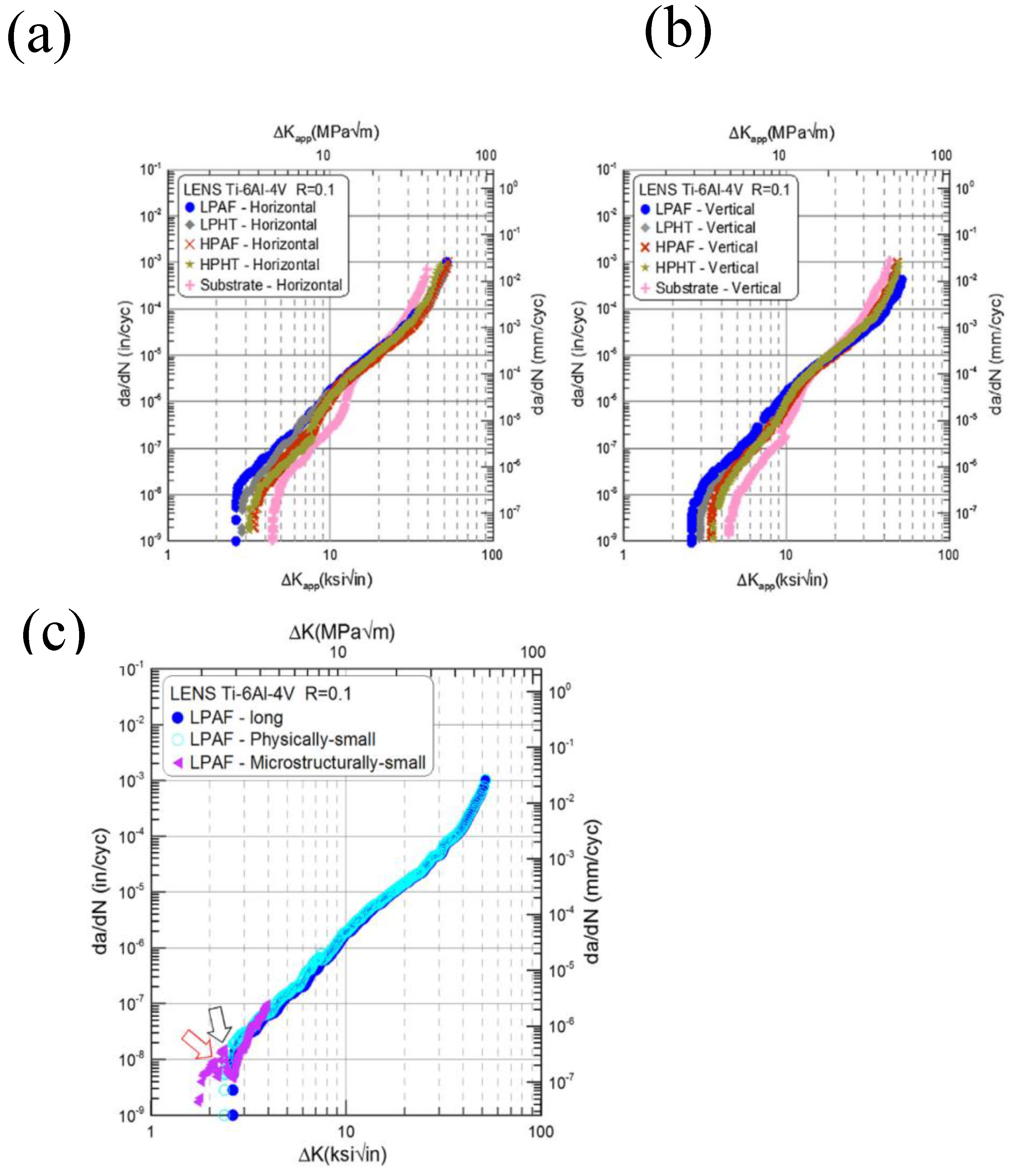

3.1. Build Orientation

3.2. Mean Stress Effect

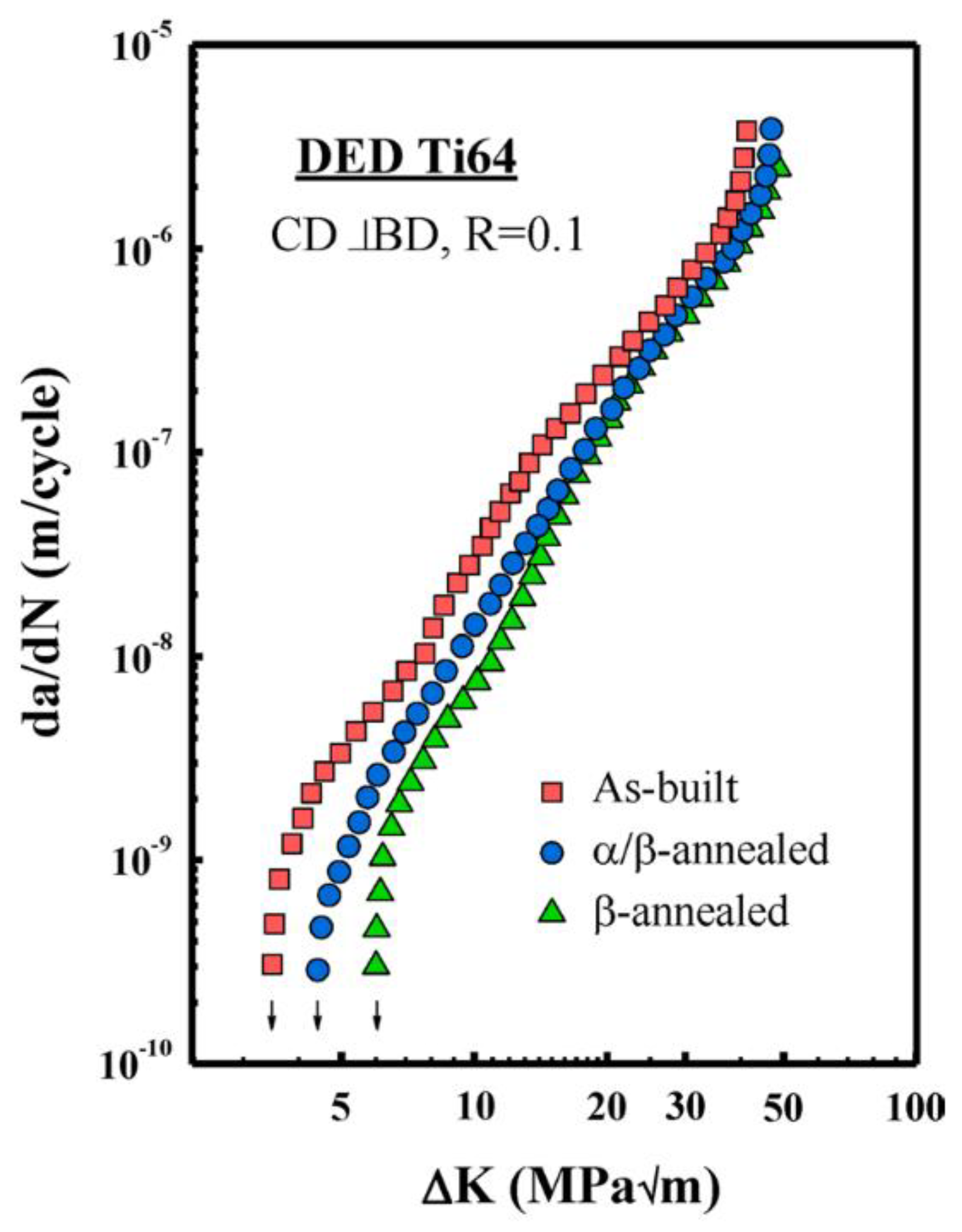

3.3. Post-Processing Heat Treatment

3.4. Combined Factors

3.5. Effect of Processing Parameters

3.6. Repairs

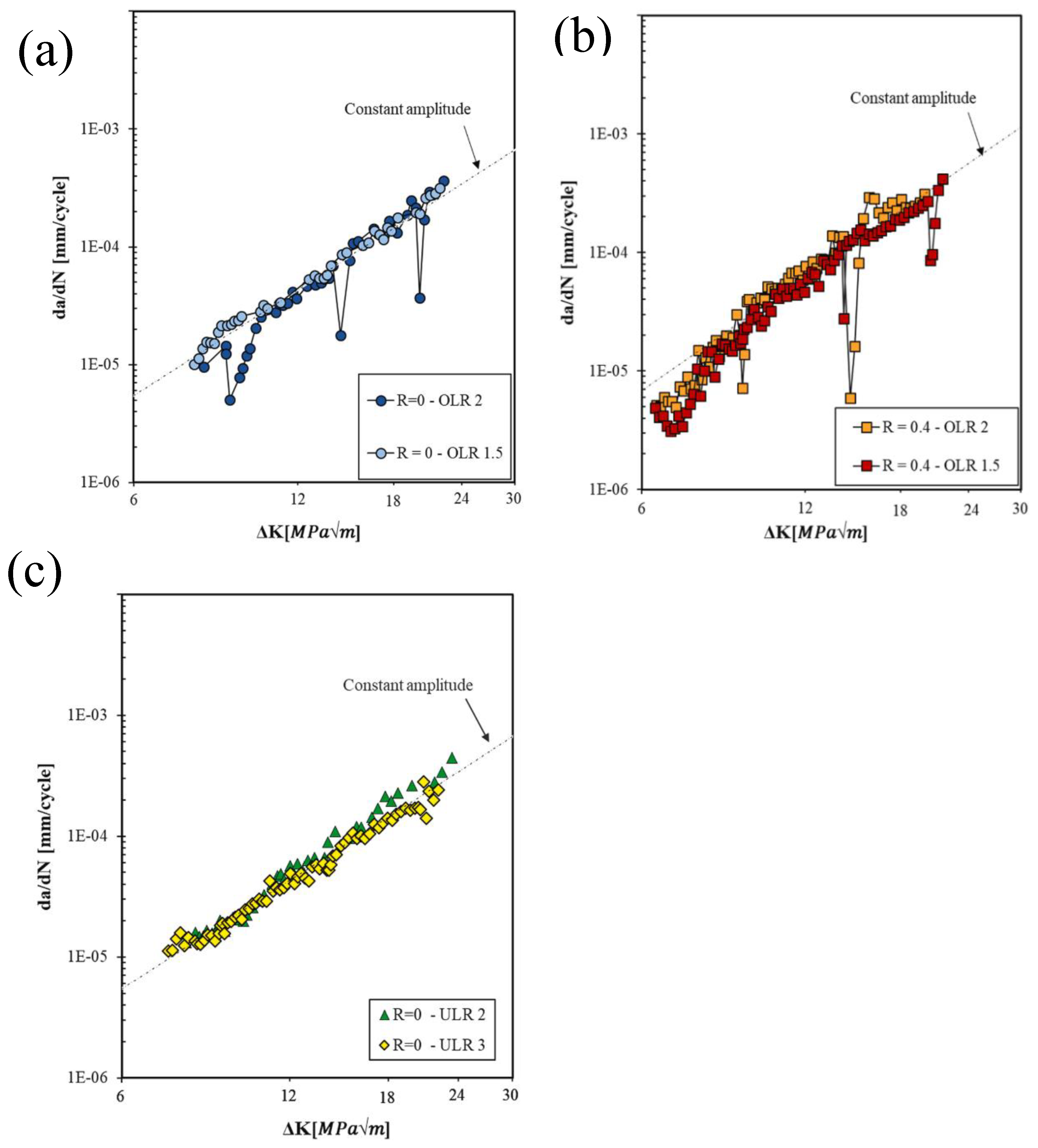

3.7. Variable Amplitude Loading

3.8. Environmental Assisted FCG

3.9. Temperature Effects

3.10. Small Cracks

4. Perspectives for Future Research

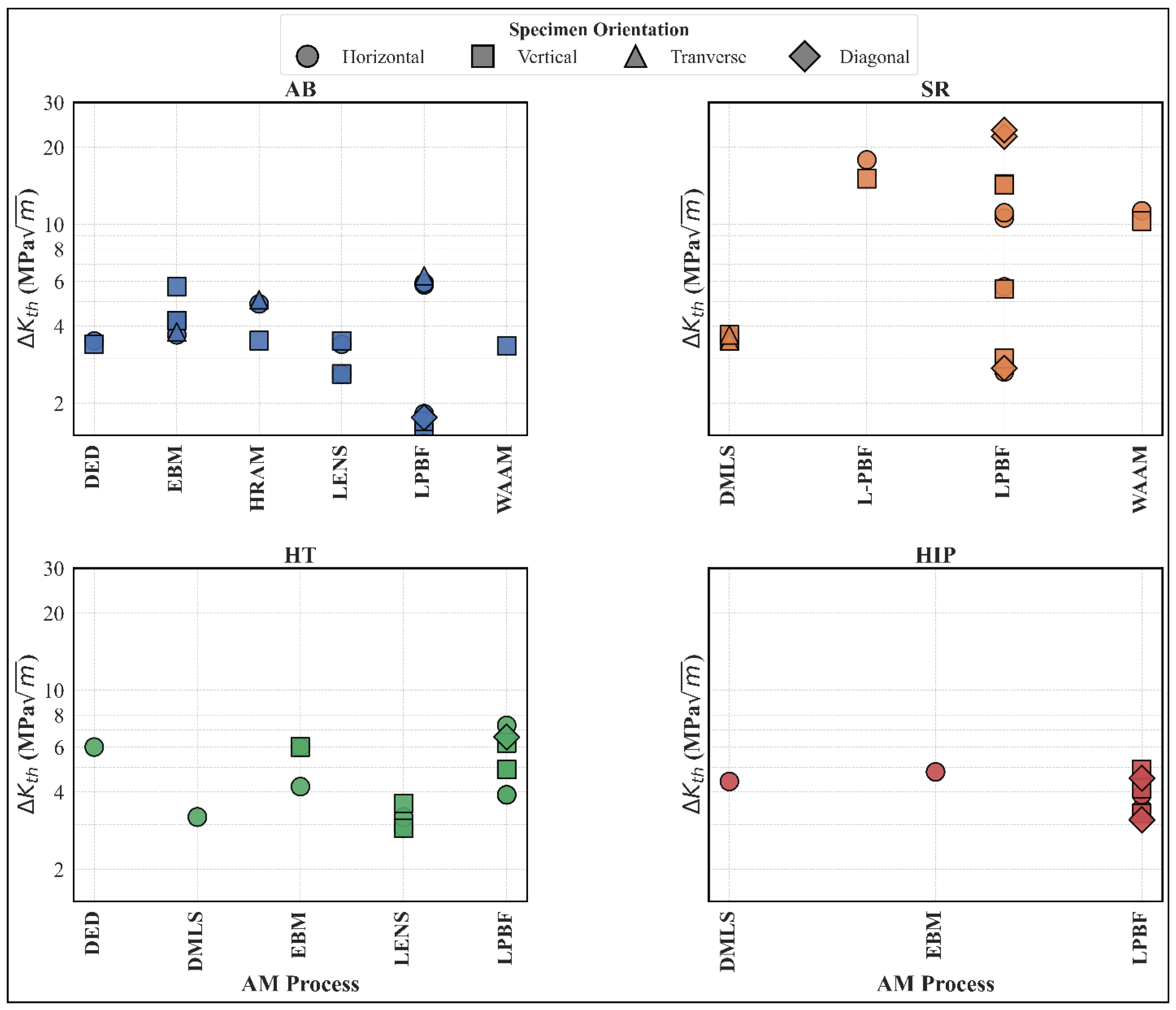

- Build Orientation Effects: The influence of build orientation on FCG behavior in AM Ti64 remains inconclusive in the current literature. Some studies report a strong dependence of FCG resistance on build orientation, whereas others find only minimal effects. These divergent results are primarily attributed to variations in residual stress states, microstructural characteristics, and defect distributions associated with specific printing directions. Most research has focused on horizontal and vertical specimen orientations; however, real-world components often experience multiaxial loading and complex geometries, which promote crack propagation along off-axis directions [117]. Evaluating FCG in off-axis orientations is therefore essential to fully capture the effects of anisotropy and layer-related defects.

- 2.

- Mean Stress Effects and Microstructural Sensitivity: The influence of mean stress, typically characterized by the stress ratio, on FCG in AM Ti64 is well documented. Higher stress ratios generally lead to faster FCG and lower ΔKth [13,118]. However, the combined effects of mean stress and microstructural features such as grain orientation, α/β morphology, and porosity on crack closure are not well understood, particularly during the transition from microstructure-sensitive near-threshold behavior (Region I) to steady-state crack growth (Region II). Addressing this knowledge gap requires targeted research that integrates comprehensive microstructural characterization with in-situ FCG testing under varying mean stress conditions. By combining advanced imaging and analysis techniques with real-time crack growth measurements, researchers can directly observe how specific microstructural features and applied mean stresses interact to influence crack closure and subsequently FCG. These insights are essential for developing more robust design standards for AM Ti64 components, ultimately ensuring greater damage tolerance and structural reliability.

- 3.

- Process Parameters and Defect Populations: FCG behavior in AM Ti64 is sensitive to process parameters such as laser power, scan speed, and hatch spacing, since these factors determine the resulting microstructure and the distribution of defects including pores and lack-of-fusion defects. Few studies [79,95,109] have systematically isolated the effects of individual process parameters, especially for small cracks where conventional fracture mechanics models may not be fully applicable. Achieving a deeper understanding of how these processing conditions impact microstructure and fatigue performance across different build orientations and loading scenarios is essential for optimizing AM processes and improving FCG resistance in AM Ti64.

- 4.

- Repairs, Interfaces, and Service-Relevant Conditions: As AM is increasingly employed for component repair, it has become crucial to understand FCG behavior at repair interfaces. Even when DED techniques closely replicate the substrate microstructure, FCG rates at the bond line are often higher than those observed in wrought Ti64 [88,110] . The specific impacts of interface microstructure on FCG performance are still not well characterized. Furthermore, most existing FCG studies are performed under constant amplitude loading, whereas actual service environments involve variable amplitude loading, multiaxial stresses, and exposure to harsh conditions. This gap in representative test data limits the ability to accurately model and predict damage tolerance for repaired components operating under real-world conditions.

- 5.

- Functionally Graded Ti64: Ti64 alloys offer excellent high-temperature strength, yet their limited wear resistance and hardness restrict use in certain aerospace applications [119]. AM enables the fabrication of functionally graded materials (FGMs) with tailored composition gradients, providing location-specific mechanical properties [119]. Unlike conventional composites with sharp interfaces, FGMs promote smooth transitions between dissimilar materials, enhancing overall performance and expanding aerospace applicability. Studies investigating reinforcements such as TiC, Al₂O₃, stainless steel, and Mo in Ti64 have reported varying improvements in micro-hardness and tensile properties depending on phase fractions [120,121,122,123]. However, while tensile and hardness data are available for functionally graded Ti64, their fatigue behavior remains underexplored. For instance, Li et al. [2] showed that TiC-reinforced Ti64 fabricated by LMD exhibited enhanced tensile and micro-hardness properties when 5% TiC is added to Ti64. This underscores the need to examine FCG, as microstructural modifications can greatly affect durability under cyclic loading and high temperatures. Comprehensive FCG evaluation is essential to establish reliable design criteria and fully realize the potential of these FGMs. High-integrity joining of Ti64 and stainless steels is vital for aerospace structures, but direct welding often leads to the formation of brittle intermetallics such as FeTi and Fe₂Ti, causing premature failure [119,120]. FGMs address this challenge by introducing graded interlayer zones, often employing Cu, Ni, or Al alloys, to reduce incompatibility. The selection of suitable interlayer materials and assessment of their fatigue properties, especially FCG behavior, are crucial for advancing robust multi-material joints.

- 6.

- Cold Spray AM: Among solid-state AM processes, cold spray has emerged as a promising technique for fabricating and repairing structural metallic components[124]. Unlike fusion-based AM methods, cold spray operates entirely in the solid state, producing dense, oxidation-free deposits with minimal thermal distortion [125,126,127]. As its applications expand from coatings to structural and load-bearing parts, evaluating the fatigue performance of cold spray materials has become increasingly important. The adoption of nondestructive inspection techniques for structural health monitoring is vital to establishing cold spray as a certified method for structural restoration, particularly in aerospace applications where continuous health monitoring is required [126,128]. Studies have shown that cold spray coatings can improve fatigue performance, with the degree of enhancement governed by coating–substrate material compatibility, interface quality, and residual stress state. Coatings composed of higher-strength materials than the substrate generally yield greater fatigue improvements. Fatigue resistance is equally critical in repair applications, where restored components must recover the fatigue strength of undamaged parts. Although variations in damage geometry and size complicate systematic evaluation, optimized cold spray repairs can extend component life while reducing costs and environmental impact.

- 7.

- Standardization and Data Openness: Progress in understanding FCG in AM Ti64 is limited by incomplete documentation and inconsistent reporting across studies. Many publications lack comprehensive details about the AM process, FCG testing methods, and post-processing conditions, making it difficult to compare results or build reliable datasets for accurate FCG modeling. To address these challenges, it is essential to establish standardized testing protocols, adopt consistent terminology, and encourage open data-sharing practices. These steps will improve reproducibility, enable robust meta-analyses, and ultimately support the development of dependable fatigue design guidelines for AM Ti64.

- 8.

- In-situ FCG testing: Of the reviewed FCG studies, only a few [61,68,73,77,89] employed in-situ FCG testing. In-situ FCG testing offers a powerful approach to directly observe crack initiation and propagation in AM Ti64, capturing the dynamic interactions between cracks, microstructure, inherent defects, and residual stresses. Unlike conventional ex-situ tests, in-situ methods provide high-resolution, real-time data that enable a mechanistic understanding of defect criticality, microstructural influences, and residual stress effects, thereby supporting improved predictive modeling, process optimization, and damage-tolerant design for aerospace applications.

- Multiscale and In-Situ Characterization: Perform more in-situ studies are needed to systematically investigate these interactions across different AM process parameters, build orientations, and heat treatment conditions to fully leverage the benefits of in-situ testing for fatigue performance assessment.

- Service-Relevant Spectrum Testing: Develop fatigue testing protocols that incorporate variable amplitude loading, multiaxial stresses, and realistic environmental conditions, such as high temperatures and corrosive media. Implementing these protocols will ensure that laboratory data more accurately represent the performance and reliability of AM Ti64 under actual service conditions.

- Data-Driven Process Optimization: Employ machine learning and big data analytics to model the complex relationships among AM process parameters, resulting microstructure, defect populations, and FCG performance. Establishing open-access databases will further accelerate the optimization of processing strategies, enabling enhanced fatigue resistance and damage tolerance in AM Ti64 components.

- Standardized Test Results Reporting: Establish unified testing protocols, clear conventions for specimen orientation, and thorough documentation of processing conditions. Promoting open data sharing and adherence to best practices will enhance the reproducibility of results, facilitate meaningful benchmarking across studies, and provide a robust foundation for certifying and qualifying AM Ti64 components in critical applications.

- Data-driven advancements in AM fatigue: Recent progress in data-driven approaches has demonstrated that these methods can significantly enhance our understanding of fatigue behavior in AM materials [137,138]. Machine learning algorithms and advanced statistical analyses are increasingly employed to uncover key process-structure-property relationships that govern fatigue performance, providing predictive capabilities that match and potentially surpass those of conventional mechanistic models. By harnessing large, high-fidelity datasets that capture the intricacies of the AM process, including build parameters, microstructural features, defect distributions, and post-processing conditions, researchers are able to develop robust models for predicting FCG behavior in Ti64. Data-driven modeling not only improves the accuracy of fatigue property predictions [138], but also facilitates the early identification of process-induced anomalies.

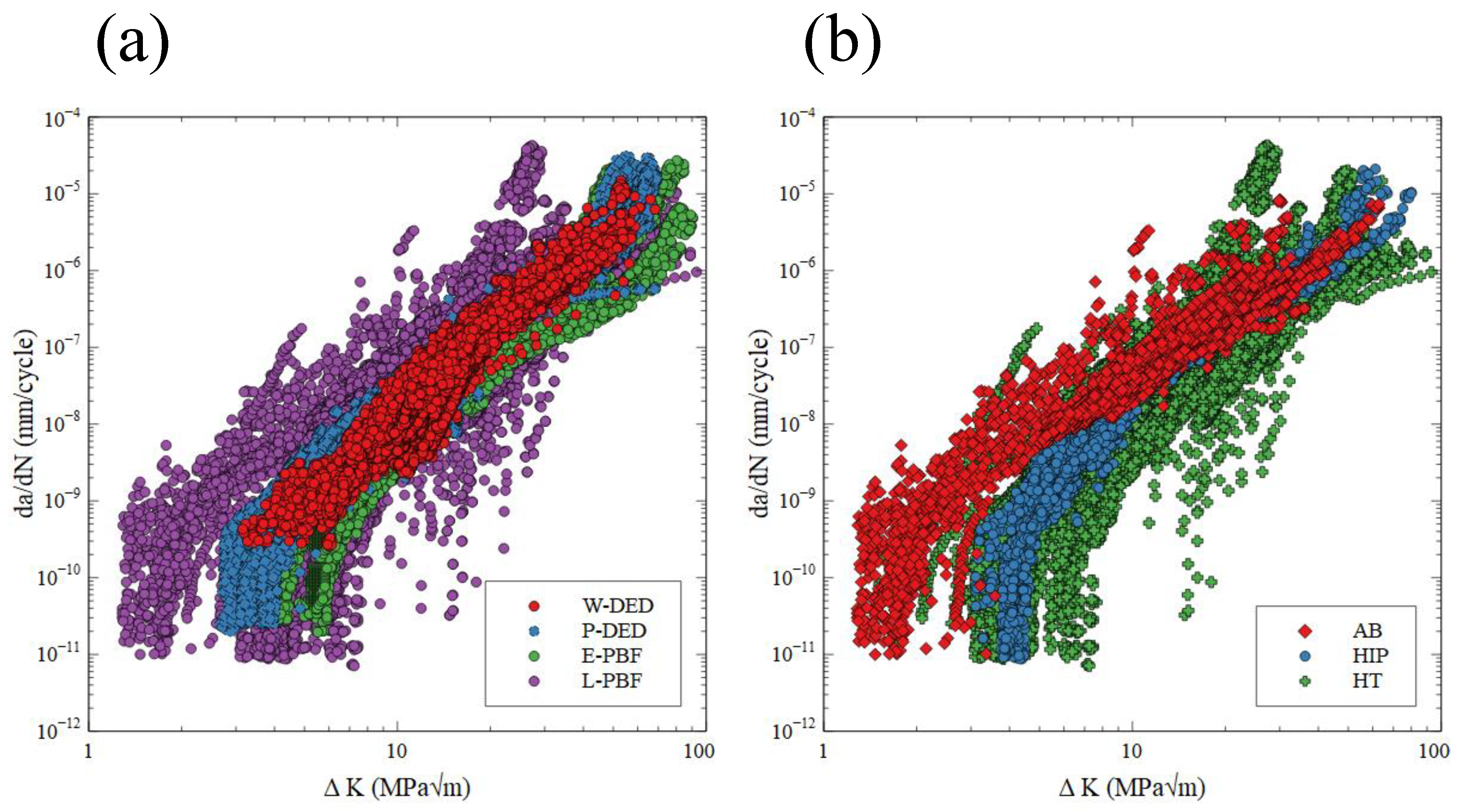

4.1. Observations on Experimental Trends in AM Ti64 FCG

4.2. A Reporting Benchmark for Quantitative Assessment of FCG Data in AM Studies

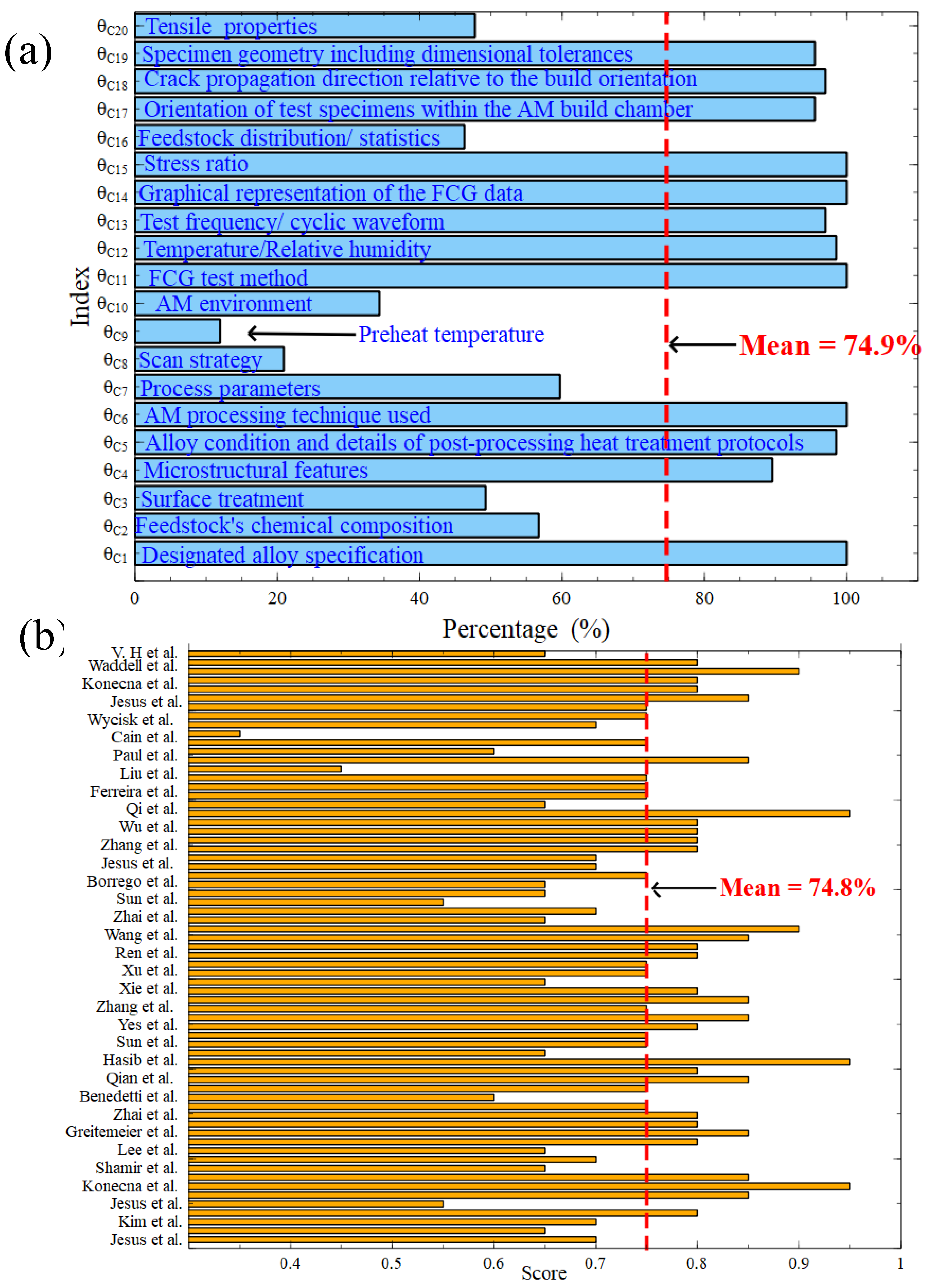

- The average score, ,for the reporting benchmark across all the reviewed AM Ti64 FCG studies is 0.75.

- Of the 20 elements of the reporting benchmark evaluated, only alloy specification, AM process type, FCG test method, graphical representation of FCG data, and R were reported in 100% of the studies.

- Additionally, the following indices were frequently reported : microstructural features, alloy condition and details of post-processing heat treatment protocols, temperature and/or relative humidity conditions during testing, fatigue test frequency and cyclic waveform characteristics, orientation of test specimens within the AM build chamber, Specimen geometry including dimensional tolerances, and crack propagation direction relative to the build orientation

- Conversely, some important indices were underreported. For example, only 12% of studies reported preheat temperature of the powder or build plate , even though preheating is critical in processes such as LPBF to reduce residual stresses, distortion, and warping, reducing the need for post-process stress-relief treatments[143,144,145]. Information on build plate preheating, another significant means of stress reduction, is also rarely included, despite evidence that elevated base plate temperatures further mitigate thermal gradients [146].

- Other commonly omitted indices include feedstock’s chemical composition, surface treatment or roughness measurements, AM process parameters , details of the controlled AM environment and shielding gas composition, powder size distribution for powder feedstock or wire diameter specification , and tensile properties

- As illustrated in Figure 17, none of the reviewed AM FCG Ti64 studies achieved full documentation

- Test conditions and data representation (Category C) are the most consistently reported, with an average of ~99.1%, demonstrating strong compliance.

- Material properties (Category A) are moderately reported (~68.1%), with gaps in powder/wire specifications and tensile properties.

- AM process and specimen preparation (Category B) are the least documented (~66.3%), with frequent omissions in preheating, scan strategy, and shielding gas details.

- Enhance documentation of AM process parameters, including preheating temperature, scan strategy, laser or electron beam power, layer thickness, build orientation, hatch spacing, powder flow rate, wire feed rate, shielding gas type, and power settings. Comprehensive reporting of these parameters is essential, as they strongly influence microstructure, porosity, defect formation, and residual stress, all of which have a critical impact on FCG behavior in AM Ti64.

- Improve reporting of material properties by thoroughly documenting powder characteristics such as particle size distribution, morphology, and chemical composition, as well as tensile behavior. These properties directly influence crack initiation and growth in AM Ti64.

- Maintain comprehensive reporting of testing conditions by consistently documenting load type, stress intensity range, R-ratio, frequency, and environmental factors. Future efforts should continue this level of thoroughness while also prioritizing the inclusion of upstream AM process parameters to further improve the reproducibility of FCG results in AM Ti64.

5. Conclusion

References

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A. Biomedical Applications of Titanium Alloys: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Warner, D.H.; Fatemi, A.; Phan, N. Critical assessment of the fatigue performance of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V and perspective for future research. Int J Fatigue 2016, 85, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, A.H.; Nandwana, P.; Yuan, T.; et al. A review on the fatigue behavior of Ti-6Al-4V fabricated by electron beam melting additive manufacturing. Int J Fatigue 2019, 119, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hadad, S.; Elsayed, A.; Shi, B.; Attia, H. Experimental Investigation on Machinability of α/β Titanium Alloys with Different Microstructures. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.S.; Ingle, S.V.; More, Y.S.; Mathe, M.S. Machining Challenges in Ti-6Al-4V. -A Review. Int J Innov Eng Technol 2015, 5, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, A. Problems and solutions in machining of titanium alloys. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2014, 70, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; et al. Additive manufacturing of metallic components – Process, structure and properties. Prog Mater Sci 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/ASTM Additive Manufacturing - General Principles Terminology (ASTM52900). Rapid Manuf Assoc 2013, 10–12. [CrossRef]

- Diegel, O.; Nordin, A.; Motte, D. Additive Manufacturing Technologies. A Pract Guid to Des Addit Manuf 2019, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.J.; Seifi, M. Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Mechanical Properties. Annu Rev Mater Res 2016, 46, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, W.E. Metal additive manufacturing: A review. J Mater Eng Perform 2014, 23, 1917–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.M.; Cutler, S.; Gao, N. Review : The Impact of Metal Additive Manufacturing on the Aerospace Industry. Metals 2019.

- Alfred, S.O.; Amiri, M. High-Temperature Fatigue of Additively Manufactured Inconel 718 A Short Review. J Eng Mater Technol 2025, 147, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirov, I.; Kolednik, O. The effect of inclusion size on the local conditions for void nucleation near a crack tip in a mild steel. Scr Mater 2005, 53, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangid, M.D. The physics of fatigue crack initiation. Int J Fatigue 2013, 57, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangid, M.D. The physics of fatigue crack propagation. Int J Fatigue 2025, 197, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbst, U.; Bruno, G.; Buffière, J.Y.; et al. Damage tolerant design of additively manufactured metallic components subjected to cyclic loading: State of the art and challenges. Prog Mater Sci 2021, 121, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Tang, W.; Zhu, Y.; et al. A holistic review on fatigue properties of additively manufactured metals. J Mater Process Technol 2024, 329, 118425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.K.; et al. A critical review on additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V alloy: Microstructure and mechanical properties. J Mater Res Technol 2022, 18, 4641–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Zhang, T.; Ryder, M.A.; Lados, D.A. A Review of the Fatigue Properties of Additively Manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Jom 2018, 70, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, D.; Kourousis, K.I.; Wallbrink, C. A review of the as-built SLM Ti-6Al-4V mechanical properties towards achieving fatigue resistant designs. Metals 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, L.; Das, R.; Qian, M.; et al. Fatigue behaviour of laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) Ti–6Al–4V, Al–Si–Mg and stainless steels: a brief overview. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi, A.; Molaei, R.; Simsiriwong, J.; et al. Fatigue behaviour of additive manufactured materials: An overview of some recent experimental studies on Ti-6Al-4V considering various processing and loading direction effects. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2019, 42, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Yang, F.; Bolzoni, L. Fatigue and fracture properties of Ti alloys from powder-based processes – A review. Int J Fatigue 2018, 117, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovvati, B.; Namdari, N.; Dehghanghadikolaei, A. Fatigue performance of selective laser melted Ti6Al4V components: State of the art. Mater Res Express 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Affolter, C. High-Cycle Fatigue Performance of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Ti-6Al-4V Alloy with Inherent Internal Defects: A Critical Literature Review. Metals 2024, 14, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgren, H.R.; Zhai, Y.; Lados, D.A.; et al. Characterization of fatigue crack growth behavior in LENS fabricated Ti-6Al-4V using high-energy synchrotron x-ray microtomography. Addit Manuf 2016, 12, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, R.N.; El-Hadad, S.; Nofal, A. Influence of heat treatment processes on microstructure evolution, tensile and tribological properties of Ti6Al4V alloy. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shin, Y.C. Additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V alloy: A review. Mater Des 2019, 164, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.K.; et al. A critical review on additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V alloy: Microstructure and mechanical properties. J Mater Res Technol 2022, 18, 4641–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.E.; Palmer, T.A.; Beese, A.M. Anisotropic tensile behavior of Ti-6Al-4V components fabricated with directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Acta Mater 2015, 87, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, B.; Lyu, T.; Zou, Y. A Review on Additive Manufacturing of Titanium Alloys for Aerospace Applications: Directed Energy Deposition and Beyond Ti-6Al-4V. Jom 2021, 73, 1804–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, C.; Peters, M. Titanium and Titanium Alloys. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Qu, D.; et al. Microstructure and Electrochemical Behavior of a 3D-Printed Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laleh, M.; Sadeghi, E.; Revilla, R.I.; et al. Heat treatment for metal additive manufacturing. Prog Mater Sci 2023, 133, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Aristizabal, M.; Wang, X.; et al. The influence of heat treatment on the microstructure and properties of HIPped Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater 2019, 165, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Feng, H. Study on selective laser melting and heat treatment of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Results Phys 2018, 10, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancken, B.; Thijs, L.; Kruth, J.P.; Van Humbeeck, J. Heat treatment of Ti6Al4V produced by Selective Laser Melting: Microstructure and mechanical properties. J Alloys Compd 2012, 541, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

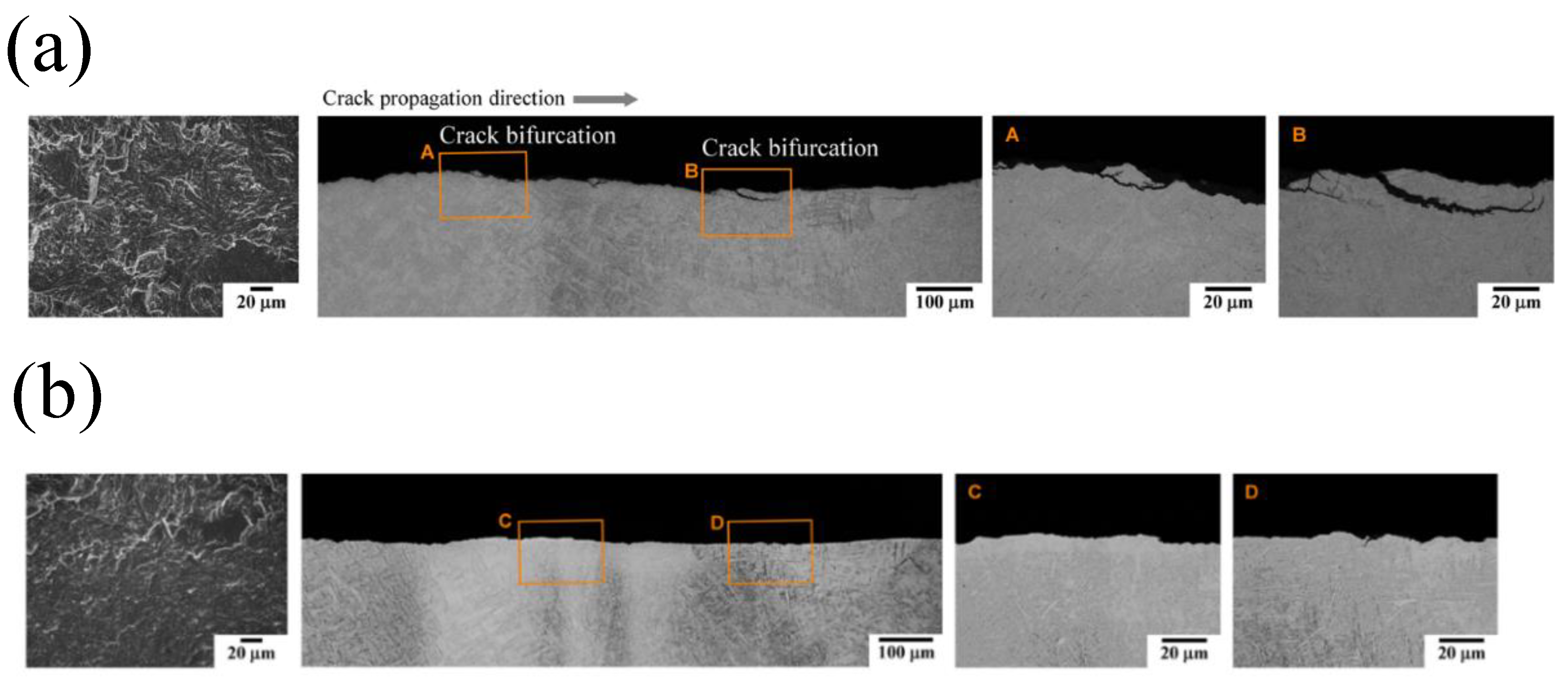

- Qi, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P.; et al. Different effects of multiscale microstructure on fatigue crack growth path and rate in selective laser melted Ti6Al4V. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2022, 45, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Chinthapenta, V.; Brandt, M.; et al. Microstructure control in additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V during high-power laser powder bed fusion. Addit Manuf 2024, 96, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sames, W.J.; List, F.A.; Pannala, S.; et al. The metallurgy and processing science of metal additive manufacturing. Int Mater Rev 2016, 61, 315–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard Test Method for Measurement of Fatigue Crack Growth Rates. 2023. [CrossRef]

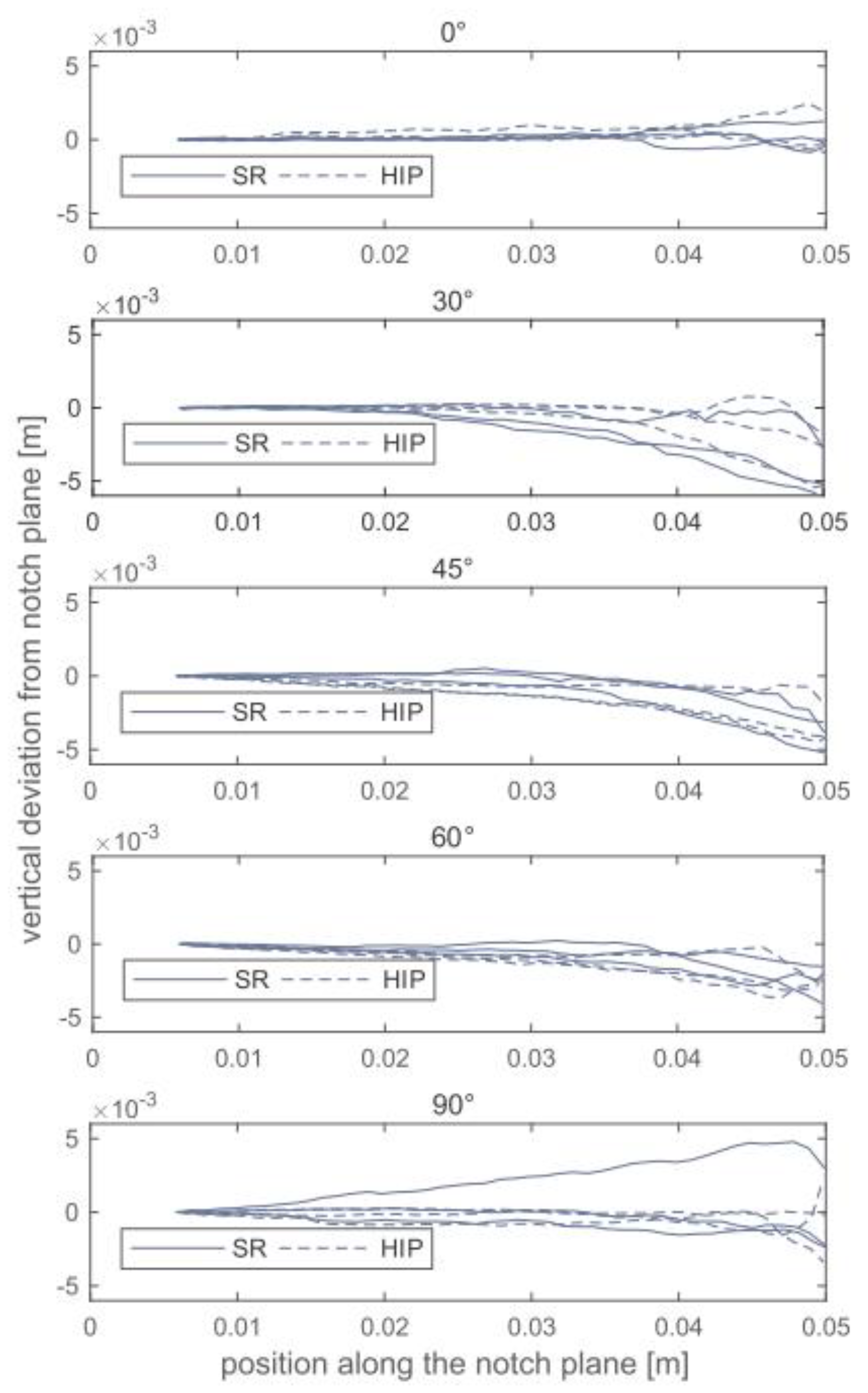

- Rans, C.; Michielssen, J.; Walker, M.; et al. Beyond the orthogonal: on the influence of build orientation on fatigue crack growth in SLM Ti-6Al-4V. Int J Fatigue 2018, 116, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.S.; Borrego, L.P.; Ferreira, J.A.M.; et al. Fatigue crack growth behaviour in Ti6Al4V alloy specimens produced by selective laser melting. Int J Fract 2020, 223, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. Environment-Assisted Fatigue Crack Propagation (EAFCP) Behavior of Ti64 Alloy Fabricated by Direct Energy Deposition (DED) Process. Metall Mater Trans A Phys Metall Mater Sci 2022, 53, 3604–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Oh, H.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, S. Effect of Annealing and Crack Orientation on Fatigue Crack Propagation of Ti64 Alloy Fabricated by Direct Energy Deposition Process. Met Mater Int 2022, 28, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.H.; Dhansay, N.M.; Haar GMTer Vanmeensel, K. Near-threshold fatigue crack growth rates of laser powder bed fusion produced Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater 2020, 197, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.S.; Borrego, L.P.; Ferreira, J.A.M.; et al. Fatigue crack growth under corrosive environments of Ti-6Al-4V specimens produced by SLM. Eng Fail Anal 2020, 118, 104852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarraga, H.; Warren, R.J.; Lados, D.A.; et al. Fatigue crack growth mechanisms at the microstructure scale in as-fabricated and heat treated Ti-6Al-4V ELI manufactured by electron beam melting (EBM). Eng Fract Mech 2017, 176, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečná, R.; Kunz, L.; Bača, A.; Nicoletto, G. Resistance of direct metal laser sintered Ti6Al4V alloy against growth of fatigue cracks. Eng Fract Mech 2017, 185, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ao, N.; Wu, S.; et al. Influence of in situ micro-rolling on the improved strength and ductility of hybrid additively manufactured metals. Eng Fract Mech 2021, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, M.; Zhang, X.; Syed, A.K. Characterising and representing small crack growth in an additive manufactured titanium alloy. Eng Fract Mech 2021, 253, 107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, E.; Zhang, X.; Lowe, T.; et al. Fatigue of laser powder-bed fusion additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V in presence of process-induced porosity defects. Eng Fract Mech 2022, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.U.; Vasudevan, A.K.; Sadananda, K. Effects of various environments on fatigue crack growth in Laser formed and im Ti-6Al-4V alloys. Int J Fatigue 2005, 27, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

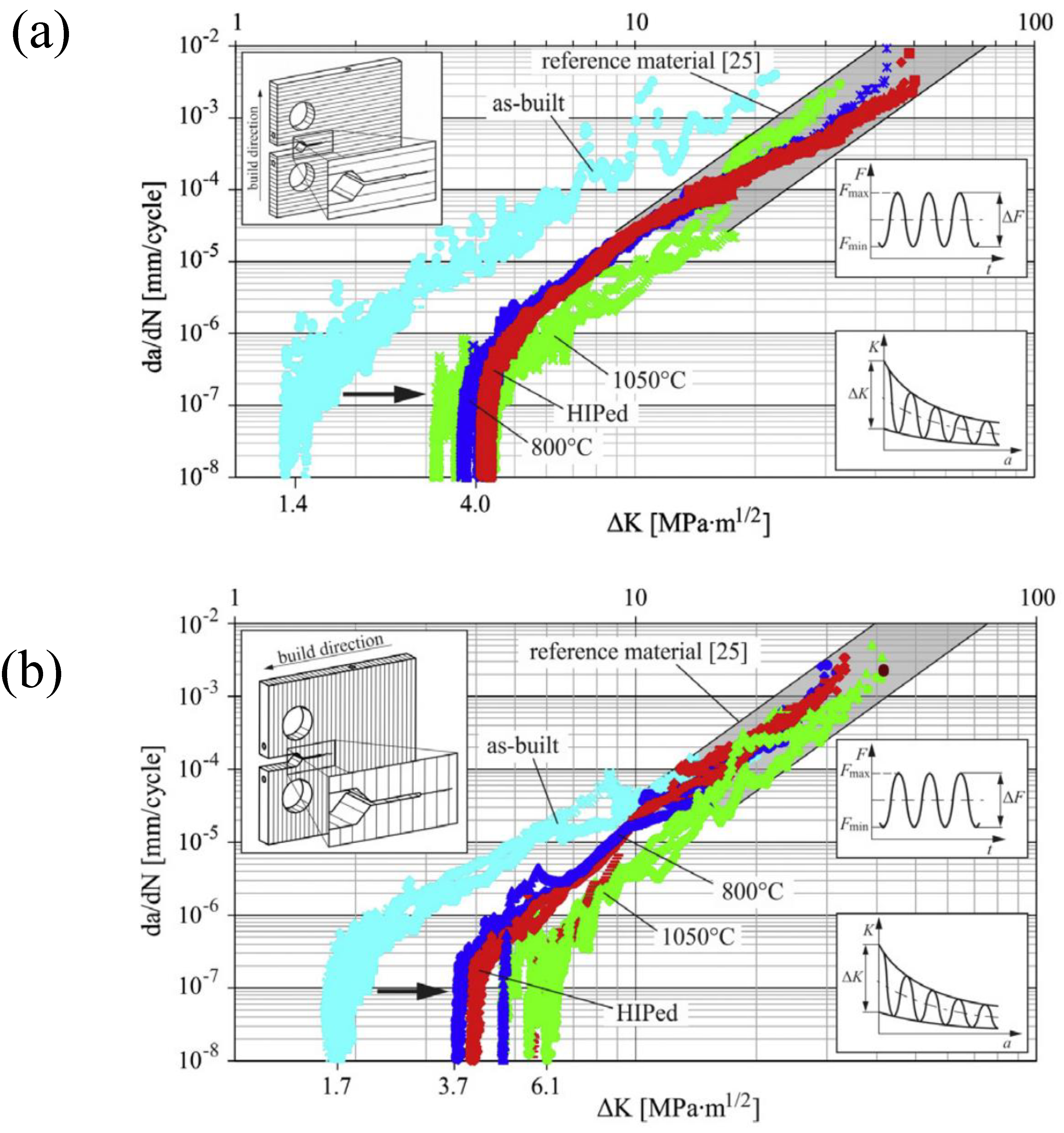

- Leuders, S.; Thöne, M.; Riemer, A.; et al. On the mechanical behaviour of titanium alloy TiAl6V4 manufactured by selective laser melting: Fatigue resistance and crack growth performance. Int J Fatigue 2013, 48, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeier, D.; Palm, F.; Syassen, F.; Melz, T. Fatigue performance of additive manufactured TiAl6V4 using electron and laser beam melting. Int J Fatigue 2017, 94, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, M.; Salem, A.; Satko, D.; et al. Defect distribution and microstructure heterogeneity effects on fracture resistance and fatigue behavior of EBM Ti–6Al–4V. Int J Fatigue 2017, 94, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Lados, D.A.; Brown, E.J.; Vigilante, G.N. Fatigue crack growth behavior and microstructural mechanisms in Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by laser engineered net shaping. Int J Fatigue 2016, 93, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Santus, C. Notch fatigue and crack growth resistance of Ti-6Al-4V ELI additively manufactured via selective laser melting: A critical distance approach to defect sensitivity. Int J Fatigue 2019, 121, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Effects of build direction on tensile and fatigue performance of selective laser melting Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Int J Fatigue 2020, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Jian, Z.; Pan, X.; Berto, F. In-situ investigation on fatigue behaviors of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by selective laser melting. Int J Fatigue 2020, 133, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.N.; Wu, S.C.; Wu, Z.K.; et al. A new approach to correlate the defect population with the fatigue life of selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Int J Fatigue 2020, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarik Hasib, M.; Ostergaard, H.E.; Li, X.; Kruzic, J.J. Fatigue crack growth behavior of laser powder bed fusion additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V: Roles of post heat treatment and build orientation. Int J Fatigue 2021, 142, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlin, M.; Ansell, H.; Moverare, J. Fatigue crack growth for through and part-through cracks in additively manufactured Ti6Al4V. Int J Fatigue 2022, 155, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Y.E.; Li, P.; Wang, Z. Residual stress and long fatigue crack growth behaviour of laser powder bed fused Ti6Al4V: Role of build direction. Int J Fatigue 2022, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Controlling the tensile and fatigue properties of selective laser melted Ti–6Al–4V alloy by post treatment. J Alloys Compd 2021, 857, 157552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Le, F.; Wei, C.; et al. Fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated via laser metal deposition: Effects of building orientation and heat treatment. J Alloys Compd 2021, 868, 159023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, A.; Wang, X. Fatigue performance differences between rolled and selective laser melted Ti6Al4V alloys. Mater Charact 2022, 189, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Paddea, S.; Zhang, X. Fatigue crack propagation behaviour in wire+arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V: Effects of microstructure and residual stress. Mater Des 2016, 90, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.N.; Wu, S.C.; Withers, P.J.; et al. The effect of manufacturing defects on the fatigue life of selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V structures. Mater Des 2020, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gao, M.; Wang, F.; et al. Anisotropy of fatigue crack growth in wire arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Mater Sci Eng A 2018, 709, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.K.; Ahmad, B.; Guo, H.; et al. An experimental study of residual stress and direction-dependence of fatigue crack growth behaviour in as-built and stress-relieved selective-laser-melted Ti6Al4V. Mater Sci Eng A 2019, 755, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.W.; Liu, A.; Wang, X.S. The influence of building direction on the fatigue crack propagation behavior of Ti6Al4V alloy produced by selective laser melting. Mater Sci Eng A 2019, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.K.; Zhang, X.; Davis, A.E.; et al. Effect of deposition strategies on fatigue crack growth behaviour of wire + arc additive manufactured titanium alloy Ti–6Al–4V. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Lin, X.; Jian, Z.; et al. Long fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti–6Al–4V produced via high-power laser directed energy deposition. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 819, 141392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, M.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Effect of microstructure on fatigue crack growth of wire arc additive manufactured Ti–6Al–4V. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 826, 141942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, K.; et al. In-situ SEM investigation on the fatigue behavior of Ti–6Al–4V ELI fabricated by the powder-blown underwater directed energy deposition technique. Mater Sci Eng A 2022, 838, 142783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. The anisotropy of high cycle fatigue property and fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti–6Al–4V alloy fabricated by high-power laser metal deposition. Mater Sci Eng A 2022, 853, 143745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Galarraga, H.; Lados, D.A. Microstructure Evolution, Tensile Properties, and Fatigue Damage Mechanisms in Ti-6Al-4V Alloys Fabricated by Two Additive Manufacturing Techniques. Procedia Eng 2015, 114, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.H.; Xu, R.D.; Yu, H.C.; Wu, X.R. Evaluation on Tensile and Fatigue Crack Growth Performances of Ti6Al4V Alloy Produced by Selective Laser Melting. Procedia Struct Integr 2017, 7, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Y.; Ai, X.; Li, J. Effects of the building direction on fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by selective laser melting. Procedia Struct Integr 2018, 13, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, J.; Borrego, L.P.; Vilhena, L.; etal., *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Effect of artificial saliva on the fatigue and wear response of TiAl6V4 specimens produced by SLM. Procedia Struct Integr 2020, 28, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, L.P.; Jesus, J.S.; Ferreira, J.A.M.; et al. Overloading effect on transient fatigue crack growth of Ti-6Al-4V parts produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Procedia Struct Integr 2021, 37, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; et al. In situ tailoring microstructure in laser solid formed titanium alloy for superior fatigue crack growth resistance. Scr Mater 2020, 174, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.S.; Borrego, L.P.; Ferreira, J.A.M.; et al. Fatigue crack growth in Ti-6Al-4V specimens produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion and submitted to Hot Isostatic Pressing. Theor Appl Fract Mech 2022, 118, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.; Ramulu, M. Effect of build direction on the fracture toughness and fatigue crack growth in selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2015, 38, 1228–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Martina, F.; Ding, J.; et al. Fracture toughness and fatigue crack growth rate properties in wire + arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2017, 40, 790–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, S.; Xie, C.; et al. Fatigue life evaluation of Ti–6Al–4V welded joints manufactured by electron beam melting. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2021, 44, 2210–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jiao, Z.; Yu, H. Study on fatigue crack growth behavior of selective laser-melted Ti6Al4V under different build directions, stress ratios, and temperatures. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2022, 45, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

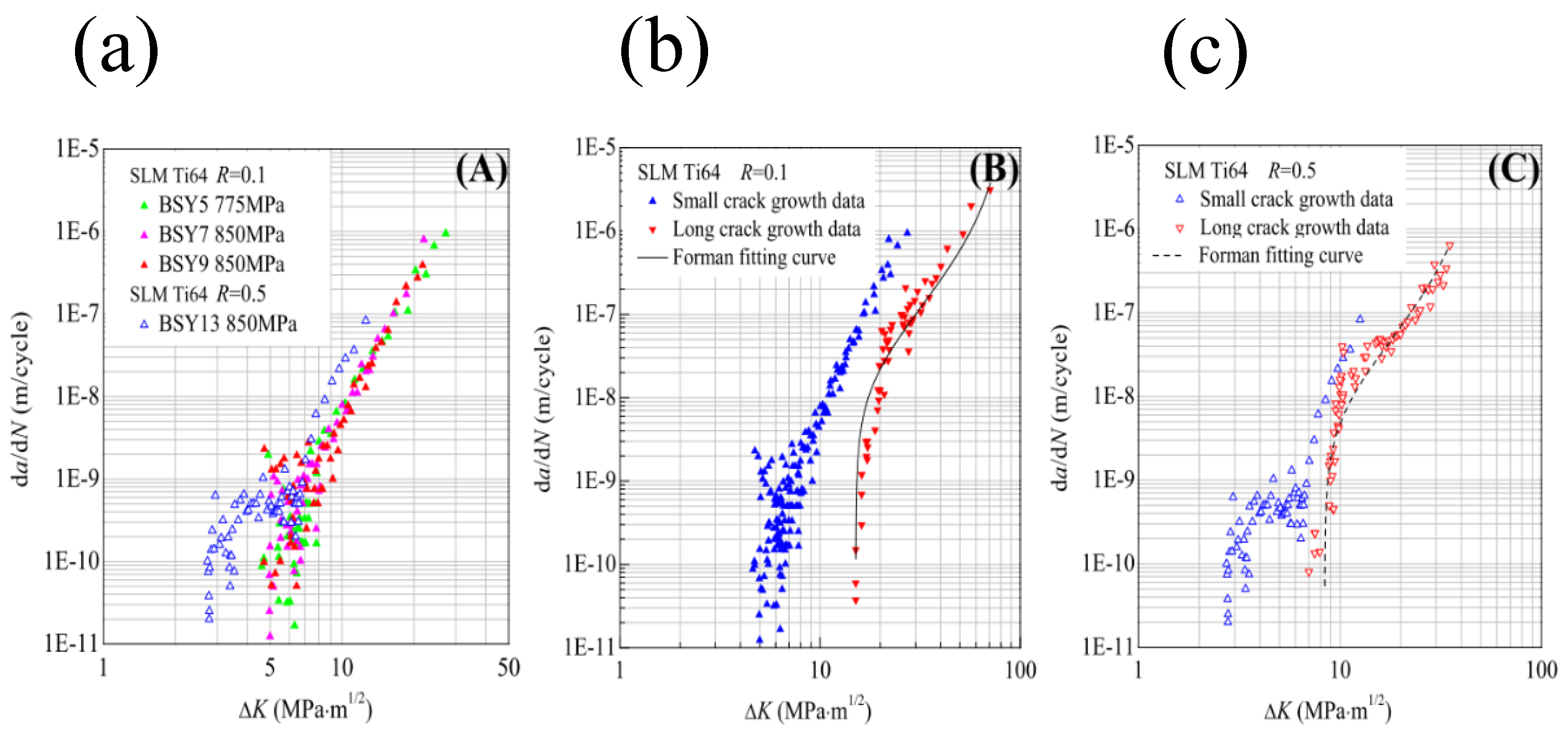

- Wu, L.; Jiao, Z.; Yu, H. Study on small crack growth behavior of laser powder bed fused Ti6Al4V alloy. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; McGill, P.; Foreman, L.; et al. Material characterization of additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V parts for an environmental control and life support system in space flight hardware. Mater Perform Charact 2020, 9, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.F.; Neto, D.M.; Jesus, J.S.; et al. Numerical prediction of the fatigue crack growth rate in SLM Ti-6Al-4V based on crack tip plastic strain. Metals 2020, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Effects of Heat Treatments on Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Ti6Al4V Alloy Produced by Laser Solid Forming. Metals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.D.; Borges, M.; Antunes, F.; Ferreira, J.; Reis, L.; Capela, C. A Novel Specimen Produced by Additive Manufacturing for Pure Plane Strain Fatigue Crack Growth Studies. Metals 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

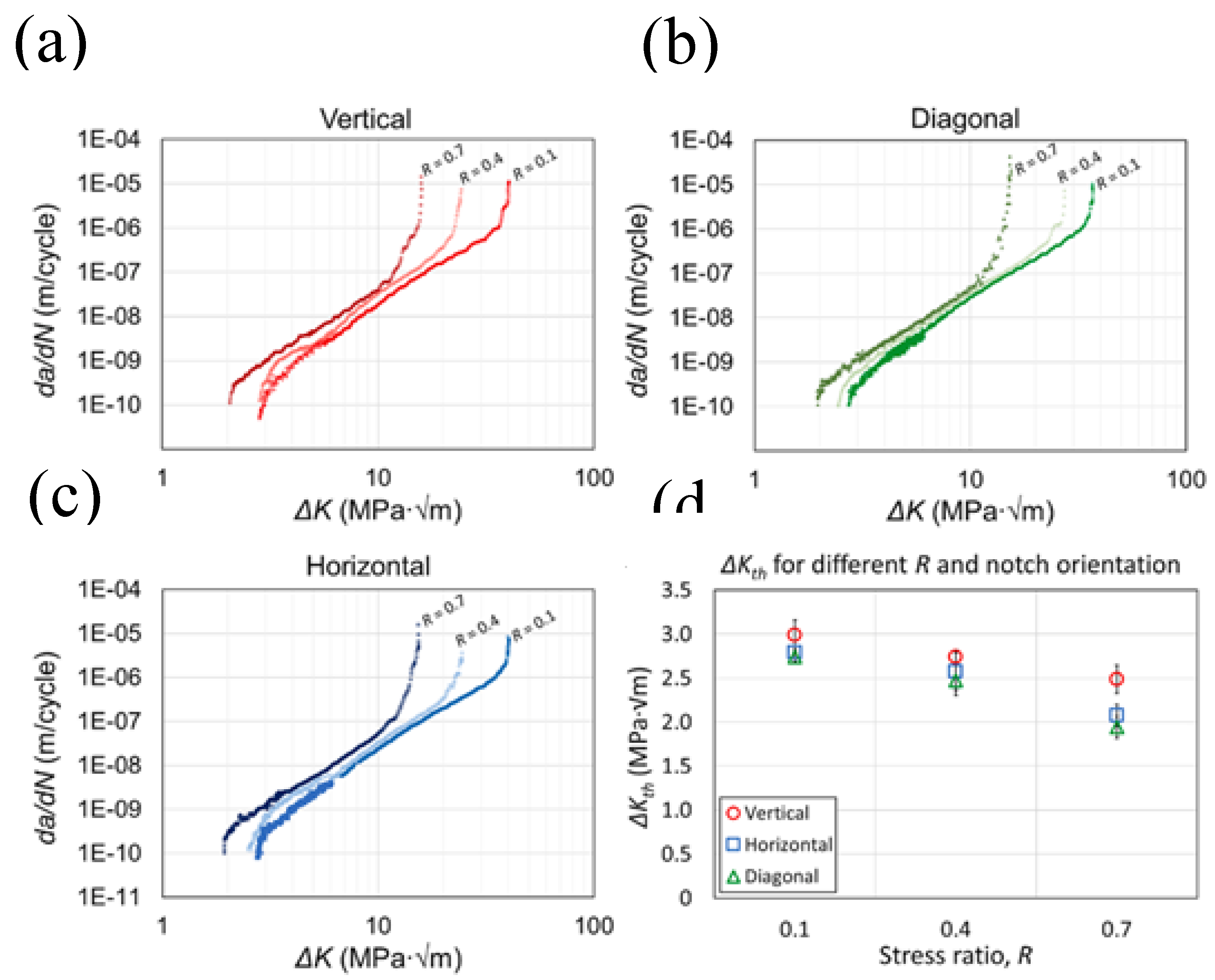

- Paul, M.; Soman, S.; Shao, S.; Shamsaei, N. Fatigue crack growth in L-PBF Ti-6Al-4V : Influence of notch orientation, stress ratio, and volumetric defects. Int J Fatigue 2025, 198, 109027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhansay, N.M.; Tait, R.; Becker, T. Fatigue and fracture toughness of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy manufactured by selective laser melting. Adv Mater Res 1019, 1019, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, V.; Thijs, L.; Van Humbeeck, J.; et al. Crack propagation and fracture toughness of Ti6Al4V alloy produced by selective laser melting. Addit Manuf 2015, 5, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wycisk, E.; Solbach, A.; Siddique, S.; et al. Effects of defects in laser additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V on fatigue properties. Phys Procedia 2014, 56, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dong, D.; Su, S.; Chen, A. Experimental study of effect of post processing on fracture toughness and fatigue crack growth performance of selective laser melting Ti-6Al-4V. Chinese J Aeronaut 2019, 32, 2383–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečná, R.; Kunz, L.; Bača, A.; Nicoletto, G. Long Fatigue Crack Growth in Ti6Al4V Produced by Direct Metal Laser Sintering. Procedia Eng 2016, 160, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macallister, N.; Vanmeensel, K.; Becker, T.H. Fatigue crack growth parameters of Laser Powder Bed Fusion produced Ti-6Al-4V. Int J Fatigue 2021, 145, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, M.; Walker, K.; Bandyopadhyay, R.; et al. Small fatigue crack growth behavior of Ti-6Al-4V produced via selective laser melting: In situ characterization of a 3D crack tip interactions with defects. Int J Fatigue 2020, 137, 105638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Prakash, O.; Ramamurty, U. Micro-and meso-structures and their influence on mechanical properties of selectively laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater 2018, 154, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, V.; Franchitti, S.; Borrelli, R.; Sepe, R. Influence of building direction on the fatigue crack-growth of Ti6Al4V specimens made by EBM. Procedia Struct Integr 2024, 53, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Prakash, O.; Ramamurty, U. Micro-and meso-structures and their influence on mechanical properties of selectively laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Acta Mater 2018, 154, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weertman, J.; Brown, R.D. 7050.

- Correia, J.A.F.O.; De Jesus, A.M.P.; Moreira, P.M.G.P.; Tavares, P.J.S. Crack Closure Effects on Fatigue Crack Propagation Rates: Application of a Proposed Theoretical Model. Adv Mater Sci Eng 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELBERW Fatigue Crack Closure Under Cyclic Tension. Eng Fract Mech 1970, 2, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Lados, D.A.; Brown, E.J.; Vigilante, G.N. Fatigue crack growth behavior and microstructural mechanisms in Ti-6Al-4V manufactured by laser engineered net shaping. Int J Fatigue 2016, 93, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; El Rassi, J.; Kannan, M.; et al. Fracture toughness and fatigue crack growth rate properties of AM repaired Ti–6Al–4V by Direct Energy Deposition. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 823, 141701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, O.E. Spectrum Loading and Crack Growth. J Basic Eng 1972, 94, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, M.; Luo, Z.; et al. Effect of microstructure on short fatigue crack growth of wire arc additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Mater Charact 2021, 177, 111183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; Annigeri, B.S. Fatigue-life prediction method based on small-crack theory in an engine material. J Eng Gas Turbines Power 2012, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; Wu, X.R.; Swain, M.H.; et al. Small-crack growth and fatigue life predictions for high-strength aluminum alloys. Part II: Crack closure and fatigue analyses. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2000, 23, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.C.; Elber, W. 1988.

- Yadollahi, A.; Shamsaei, N. Additive manufacturing of fatigue resistant materials: Challenges and opportunities. Int J Fatigue 2017, 98, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, S.; Lee, K.T.; et al. On the crack resistance and damage tolerance of 3D-printed nature-inspired hierarchical composite architecture. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mote, A.; Lacy, T.E.; Newman, J.C. Assessing fatigue crack growth thresholds for a Ti-6Al-4V (STOA) alloy using two experimental methods. Eng Fract Mech 2024, 301, 110006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, F.; Huang, Z.; et al. Additive manufacturing of functionally graded materials: A review. Mater Sci Eng A 2019, 764, 138209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, L.D.; Bocklund, B.; Otis, R.; et al. Characterization of a functionally graded material of Ti-6Al-4V to 304L stainless steel with an intermediate V section. J Alloys Compd 2018, 742, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Maunoury, C.; Weiss, L.; Acquier, P.; et al. Functionally graded Ti6Al4V-Mo alloy manufactured with DED-CLAD ® process. Addit Manuf 2017, 17, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xie, W.; Tu, Y.; et al. Ti–6Al–4V microstructural functionally graded material by additive manufacturing: Experiment and computational modelling. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 823, 141782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Direct fabrication of compositionally graded Ti-Al2O3 multi-material structures using Laser Engineered Net Shaping. Addit Manuf 2018, 21, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Lu, S.; Silwal, R.; Zhu, W. A Review on Material Dynamics in Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing: Bonding, Stress, and Structural Evolution in Metals. Metals 2025, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, A.; Silwal, R.; Koirala, B.; Zhu, W. Advancements in Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing: Process, Materials, Optimization, Applications, and Challenges. Materials 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, M.; Thirumalaikumarasamy, D.; Sonar, T.; et al. An overview of cold spray coating in additive manufacturing, component repairing and other engineering applications. J Mech Behav Mater 2022, 31, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, O.B.; Alex, A.C.; Kubacki, G.W.; et al. Corrosion Behavior of Cold Sprayed Aluminum Alloys 2024 and 7075 in an Immersed Seawater Environment. Corrosion 2021, 77, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherifard, S.; Guagliano, M. Fatigue performance of cold spray deposits: Coating, repair and additive manufacturing cases. Int J Fatigue 2020, 139, 105744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.W.Y.; Wen, S.; Khun, N.W.; et al. Potential of cold spray as additive manufacturing for TI6AL4V. Proc Int Conf Prog Addit Manuf Part 1290, F1290, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SENGDHL; ZHANGZ; ZHANGZQ; et al. Influence of spray angle in cold spray deposition of Ti-6Al-4V coatings on Al6061-T6 substrates. Surf Coatings Technol 2022, 432, 128068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, R.F.; Avila, J.A.; Barriobero-Vila, P.; et al. Heat treatment effect on microstructural evolution of cold spray additive manufacturing Ti6Al4V. J Mater Sci 2025, 60, 5558–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.S.; Shipway, P.H.; McCartney, D.G. Effect of cold spray deposition of a titanium coating on fatigue behavior of a titanium alloy. Proc Int Therm Spray Conf 2006, 15, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.W.Y.; Sun, W.; Bhowmik, A.; et al. Effect of coating thickness on microstructure, mechanical properties and fracture behaviour of cold sprayed Ti6Al4V coatings on Ti6Al4V substrates. Surf Coatings Technol 2018, 349, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Tan, A.W.Y.; Khun, N.W.; et al. Effect of substrate surface condition on fatigue behavior of cold sprayed Ti6Al4V coatings. Surf Coatings Technol 2017, 320, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, S.; Cormier, J.; Quet, A.; et al. Microstructure optimization of cold sprayed Ti-6Al-4V using post-process heat treatment for improved mechanical properties. Addit Manuf 2024, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondas, J.; Guagliano, M.; Bagherifard, S.; et al. Cold Spray Additive Manufacturing of Ti6Al4V: Deposition Optimization. J Therm Spray Technol 2024, 33, 2672–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y. Fatigue modeling using neural networks: a comprehensive review. Authorea Prepr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alfred, S.O.; Amiri, M. A data-informed knowledge discovery framework to predict fatigue properties of additively manufactured Ti–6Al–4V, IN718 and AlSi10Mg alloys using fatigue databases. Prog Addit Manuf. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.; Burvill, C. Applicability of published data for fatigue-limited design. Qual Reliab Eng Int 2009, 25, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Qian, M.; Elambasseril, J.; et al. Fatigue test data applicability for additive manufacture: A method for quantifying the uncertainty of AM fatigue data. Mater Des 2023, 231, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard Practice for Reporting Data for Test Specimens Prepared by Additive Manufacturing. ASTM F2971 − 13 2021, 13, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- ASTM Standard Practice for Presentation of Constant Amplitude Fatigue Test Results for Metallic Materials. ASTM E468-18 2007, 90, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Bayoumy, D.; Boll, T.; Karapuzha, A.S.; et al. Effective Platform Heating for Laser Powder Bed Fusion of an Al-Mn-Sc-Based Alloy. Materials 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvan, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Fereiduni, E.; et al. Part deflection and residual stresses in laser powder bed fusion of H13 tool steel. Mater Des 2021, 204, 109659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingbeil, N.W.; Beuth, J.L.; Chin, R.K.; Amon, C.H. Residual stress-induced warping in direct metal solid freeform fabrication. Int J Mech Sci 2002, 44, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbareslamloo, S.; Dzukey, G.A.; Islam Muhit, M.M.; Qattawi, A. Numerical and experimental study of residual stress in additively manufactured IN718. Manuf Lett 2025, 44, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | AM type | Orientation | Fatigue Temperature (°C) | Fatigue Environment | Load Ratio | Frequency (Hz) | Specimen Type | Type of fatigue test |

| [44] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.05,0.4 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [45] | P-DED | H, V | RT | Air, 3.5% NaCl | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [46] | P-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [47] | L-PBF | H, V, T | RT | Air | 0.1-0.92 | 60,80 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [48] | L-PBF | - | RT | Air, artificial saliva, Ringer’s solution | 0.05 | 1,10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [49] | E-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1,0.5,0.8 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [50] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 50,80 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [51] | W-DED+ roll | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [52] | W-DED | V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [53] | L-PBF | - | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | Rectangular c/s | Uniaxial |

| [54] | P-DED | - | RT | Air, vacuum, 3.5% NaCl | 0.1,0.9 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [55] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10,40 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [56] | L-PBF (E-PBF) | H | RT | Air | 0.1,0.7 | - | C(T), SEN(B) | Uniaxial |

| [57] | E-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1,0.3,0.7 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [58] | P-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1,0.8 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [43] | L-PBF | H, V, D, 30° | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | SEN(T) | Uniaxial |

| [59] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1,1 | 150 | M(T) | Uniaxial |

| [60] | L-PBF | H, V, D | RT | Air | 0.1,0.3,0.6 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [61] | L-PBF | H, V | 400 | Air | 0.2 | 10 | SEN(T) | In-situ SEM |

| [62] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [63] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 60 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [64] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1,0.5 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [65] | L-PBF | 15°,30°,60°,75°, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [66] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | -1 | 20 | SEN(T) | Uniaxial |

| [67] | P-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [68] | L-PBF | H, V, D | RT | Air | 0.1 | 8 | SEN(T) | In-situ SEM |

| [69] | W-DED+wrought | V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [70] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | - | Uniaxial |

| [71] | W-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 8 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [72] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [73] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 8 | SEN(T) | In-situ SEM |

| [74] | W-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

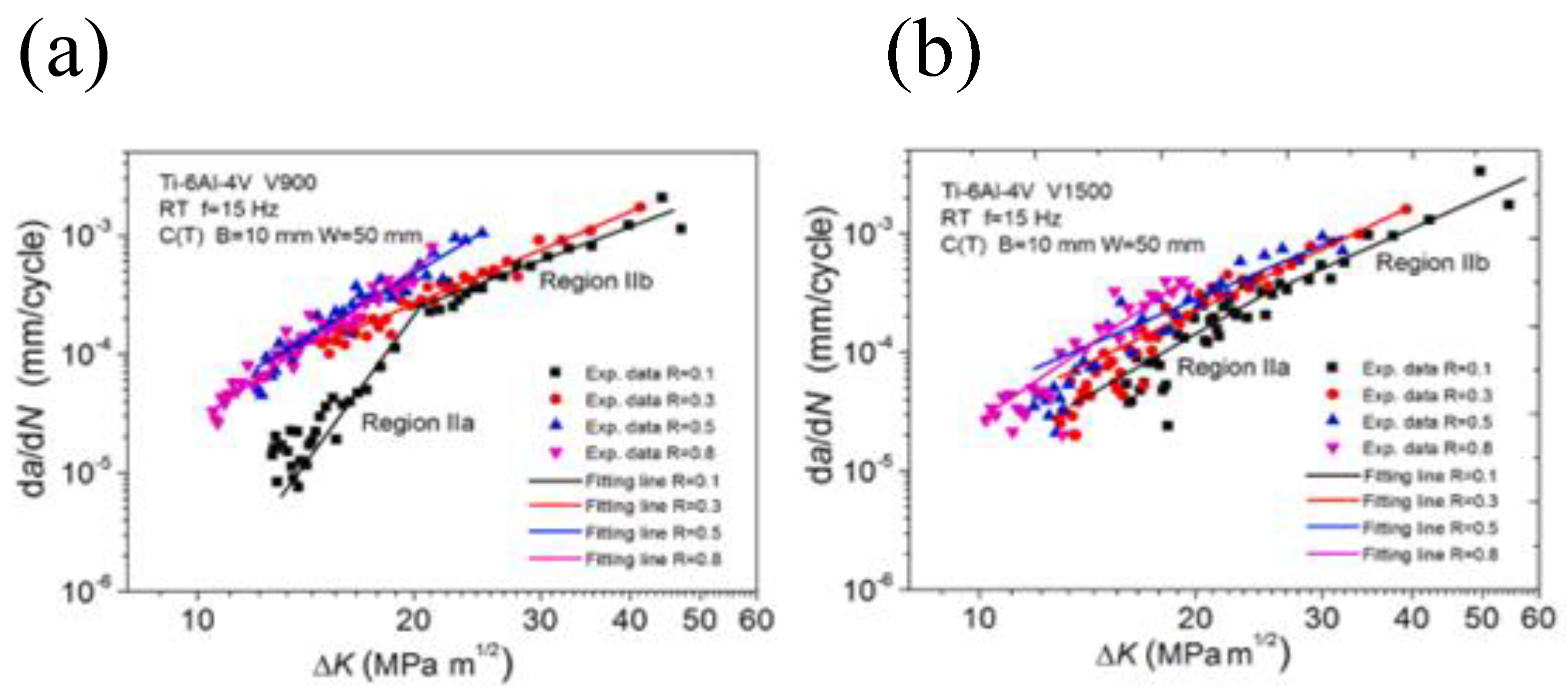

| [75] | P-DED | H | RT | Air | 0.1,0.3,0.5,0.8 | 15 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [76] | W-DED | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 30 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [77] | P-DED | V | RT | Air | 0.2 | 10 | SEN(T) | In-situ SEM |

| [78] | P-DED | V, T | RT | Air | 0.1 | 0.5 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [79] | E-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [80] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1,0.5 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [81] | L-PBF | H, V, D | RT | Air | 0.1 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [82] | L-PBF | V | RT | Air, artificial saliva | 0.05 | 1,10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [83] | L-PBF | V | RT | Air | 0 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [84] | P-DED | H | RT | Air | 0.1 | 15 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [85] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [86] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [87] | W-DED+Wrought | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [88] | W-DED+weld | T | RT | Air | 0.1 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [89] | L-PBF | H, V | RT, 400 | Air | 0.1,0.5 | - | SEN(T) | In-situ SEM |

| [90] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1,0.5 | 10 | SEN(T) | Uniaxial |

| [39] | L-PBF | V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [91] | L-PBF | V | RT | Air | 0.1 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [92] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.05 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [93] | P-DED | H | RT | Air | 0.1 | 20 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [94] | L-PBF | H, V | RT | Air, vacuum | 0 | 15 | Circular c/s | Uniaxial |

| [95] | L-PBF | - | RT | Air | 0.1,0.4,0.7 | 15 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [96] | SLM | H, V, D | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [97] | SLM | H, V | RT | Air | -1 | 5 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [98] | SLM | H, V, D | RT | Air | 0.1 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [99] | L-PBF | - | RT | Air | 0.1 | 13 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [85] | L-PBF | H | RT | Air | 0.1 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [100] | DMLS | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 50,80 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [101] | L-PBF | H, V, T | RT | Air | 0.1 | - | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [102] | SLM | H, V | RT | Air | 0.05 | 0.5,3 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| [103] | SLM | H, V | RT | Air | 0.1 | 10 | C(T) | Uniaxial |

| Element | ASTM Reference | FCG relevant documentation |

| * | Alloy specification (e.g. Ti64) | |

| * | Grade (e.g., general purpose, aerospace, biomedical, extra-low interstitial, etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.3 | The chemical composition and the weight percentage of each element | |

| E647-10.1.1 | Specimen type (C(T), M(T), SENT etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.1 | Drawings showing the specimen geometry and important dimensions | |

| * | Plain stress or plane strain conditions | |

| E647-10.1.13 | Processing route used to produce the specimen | |

| E647-10.1.13 | Heat treatment procedure (duration, temperature, atmosphere, and method of cooling) | |

| E647-10.1.2 | Experimental set up (Test machine, grips used etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.1 | Machine type (pneumatic vs servo-hydraulic) | |

| E647-10.1.4 | Orientation & position: crack/build direction and location in AM build | |

| * | Surface treatment and roughness measurement | |

| * | Machining method (e.g., milling, turning, grinding) | |

| * | Polishing steps and travel direction | |

| E647-10.1.12 | Test method (Constant-force-amplitude test procedure, K-Decreasing procedure) | |

| E647-10.1.8 | Data reduction technique used to convert a-N to da/dN -ΔK and calculate the FCG properties (secant, incremental polynomial method etc.) | |

| * | FCG measurement technique (visual tracking, post-mortem fractographic analysis of striation spacing, and measurement of crack opening displacement) | |

| * | Pre-cracking method (mechanical pre-cracking, electrolytic pre-cracking etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.5 | Terminal values of ΔK, R, and a from fatigue pre-cracking | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Cyclic waveform (e.g., sinusoidal, triangular etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Test frequency | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Load or stress ratio | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Applied force range, ΔP (e.g., ) | |

| E647-10.1.7 | Environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, relative humidity, test medium) | |

| * | Failure criterion (e.g., critical crack length, sudden fracture, unstable crack growth) | |

| * | Target FCG parameters (e.g., Paris law constants, threshold ΔKₜₕ) | |

| E647-10.1.13 | Tabulation of FCG results (e.g., a, N, da/dN, ΔK etc.) | |

| E647-10.1.10 | Graphical FCG results, including a–N, da/dN -ΔK | |

| * | Fracture surface analysis (crack path, roughness, and features) | |

| E647-10.1.11 | Record of test anomalies influencing data validity (e.g., transients from load interruptions, shifts in R, or unexpected system responses | |

| E647-10.1.3 |

Report tensile properties following ASTM E8/E8M test methods |

| Element | ASTM Reference | AM relevant documentation |

| F2971-5.1.1.1 | AM feedstock: description and preparation | |

| F2971-5.1.1.2 | Feedstock reuse procedure | |

| F2971-5.1.1.4 | Special production procedures | |

| F2971-5.1.1.3 | Standard production processes (from feedstock to specimen) | |

| F2971-5.1.1.3 | Specimen placement and orientation in build chamber | |

| F2971-5.1.2.1 | Nominal dimensions and allowable tolerances | |

| F2971-5.1.2.1 | Experimental plan | |

| F2971-5.1.2.1 | Experimental procedures | |

| F2971-5.1.2.1 | Non-destructive testing method | |

| F2971-5.1.2.2 | Description of non-conventional test methods | |

| F2971-5.1.2.3 | Additional post-processing steps |

| ASTM Reference | Description | |

| - | Designated alloy specification or material grade | |

| E647-10.1.3 | Feedstock’s chemical composition | |

| - | Surface preparation/condition/ roughness measurements | |

| - | Microstructural features | |

| E647-10.1.3 | Alloy condition and details of post-processing heat treatment protocols | |

| F2971 -5.1.1.3 | AM processing technique used | |

| F2971 -5.1.1.3 | AM process parameters | |

| F2971 -5.1.1.3 | Scan strategy utilized during the AM fabrication process | |

| F2971 -5.1.1.3 | Build plate or substrate preheating temperature | |

| F2971 -5.1.1.3 | Details of the controlled AM environment and shielding gas composition | |

| E647-10.1.12 | Employed FCG testing methodology | |

| E647-10.1.7 | Temperature and/or relative humidity conditions during testing | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Fatigue test frequency and cyclic waveform characteristics | |

| E647-10.1.13 | Graphical plots illustrating FCG experimental results | |

| E647-10.1.6 | Load ratio or R applied during fatigue testing | |

| F2971 – 5.1.1.1 | Powder size distribution for powder feedstock or wire diameter specification | |

| F2971 – 5.1.1.3 | Orientation of test specimens within the AM build chamber | |

| F2971 – 5.1.2.1 | Precise specimen geometry including dimensional tolerances | |

| E647-10.1.4 | Crack propagation direction relative to the build orientation | |

| E647-10.1.3 | Tensile properties |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).