Introduction

There has been very little study of the prevalence rates of autism in military versus civilian families in the United States, despite differences in healthcare as well as exposures to toxins between civilian and military families. An unpublished analysis of autism prevalence in the late 2000s shows that in military families the prevalence was 1 in 88 as compared to the general US population at 1 in 110 [

1]. This may be due to better diagnosis of autism within military families as it has been shown that children in military families receive autism diagnoses earlier than their civilian counterparts [

2]. However, earlier diagnosis of autism does not necessarily account for the differences in stressors including environmental toxin exposures between active duty service members, reservists and civilians.

In this paper, we compare autism prevalence in military and civilian families. We pay specific attention to the effect of service member status (active duty or reserves) and deployment for both male and female parents within the military.

Methods

During the years 2016 thru 2023 the US Census Bureau (USCB) conducted a National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) [

3]. The survey asked a series of predefined questions to tens of thousands of Americans.

Tricare:

The topical variables relevant to this analysis included the following questions for the child:

“Autism ASD” (code: K2Q35A): “Has a doctor or other health care provider EVER told you that this child has…Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)? Include diagnoses of Asperger's Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD).” Responses are coded as ‘Yes’ (1) or ‘No’ (2).

“Health Insurance - TRICARE” (coded TRICARE): “Is this child CURRENTLY covered by any of the following types of health insurance or health coverage plans? TRICARE or other military health care”. Responses are coded as ‘Yes’ (1) or ‘No’ (2).

Active duty status:

The topical variables relevant to this analysis additionally include questions regarding the adult caregiver responding to the survey (designated A1) and, if there is one, a second adult considered a primary caregiver (designated A2). The following questions are utilized for the adults:

Sex (coded A1_SEX and A2_SEX): “What is your sex?” (for A1) or “What is this caregiver's sex?” (for A2). Responses are coded as ‘Male’ (1) or ‘Female’ (2).

Relation (coded A1_RELATION and A2_RELATION): “How are you related to this child?” (for A1) and “How is this other caregiver related to this child?” (for A2). The relevant response coded is “Biological or Adoptive Parent” (1).

Active Duty (coded A1_ACTIVE and A2_ACTIVE): “Have you ever served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces, Reserves, or the National Guard?” (for A1) and “Has this caregiver ever served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces, Reserves, or the National Guard?” (for A2). Responses are coded as “Never served in the military” (1), “Only on active duty for training in the Reserves or National Guard” (2), “Now on active duty” (3), or “On active duty in the past, but not now” (4).

Deployment Status (coded A1_DEPLSTAT and A2_DEPLSTAT): “Were you deployed at any time during this child's life?” (for A1) and “Was this primary caregiver deployed at any time during this child's life?” (for A2). Responses are coded as “Yes” (1) and “No” (2).

This portion of the study seeks to examine an outcome on children of long-term active duty status mothers and fathers. “Never served in the military” form the baseline cohort. “Only on active duty for training in the Reserves or National Guard” form the National Guard/Reserve cohort. “Now on active duty” and “[o]n active duty in the past, but not now” with deployment status of “[n]o” form the Active Duty Not Deployed cohort. “Now on active duty” and “[o]n active duty in the past, but not now” with deployment status of “[y]es” form the Active Duty Deployed cohort.

The responses of ASD were compiled in the context of the mother or father having a history of active duty. A mother or father is defined as either A1 or A2 indicating their relation as “[b]iological or [a]doptive caregiver” and having a sex of ‘[f]emale’ or ‘[m]ale’, respectively. As the children themselves were counted, there was no double-counting for children of same-sex parents. In the event of both same-sex parents with military service, the parent with the highest engagement was represented (in order: Active Duty Deployed; Active Duty Not Deployed; National Guard/Reserve; non-military service).

Statistical adjustments were made using logistic regression for: the child’s age, sex, and race; state (using the 2-digit Federal Information Processing System (FIPS) code; survey year. For analyses involving parental military service engagement, parental age was included in the adjustment. Adjustments were made using the Statsmodels (v0.14.1) library package running on Python (v3.8.10).

Results

Tricare:

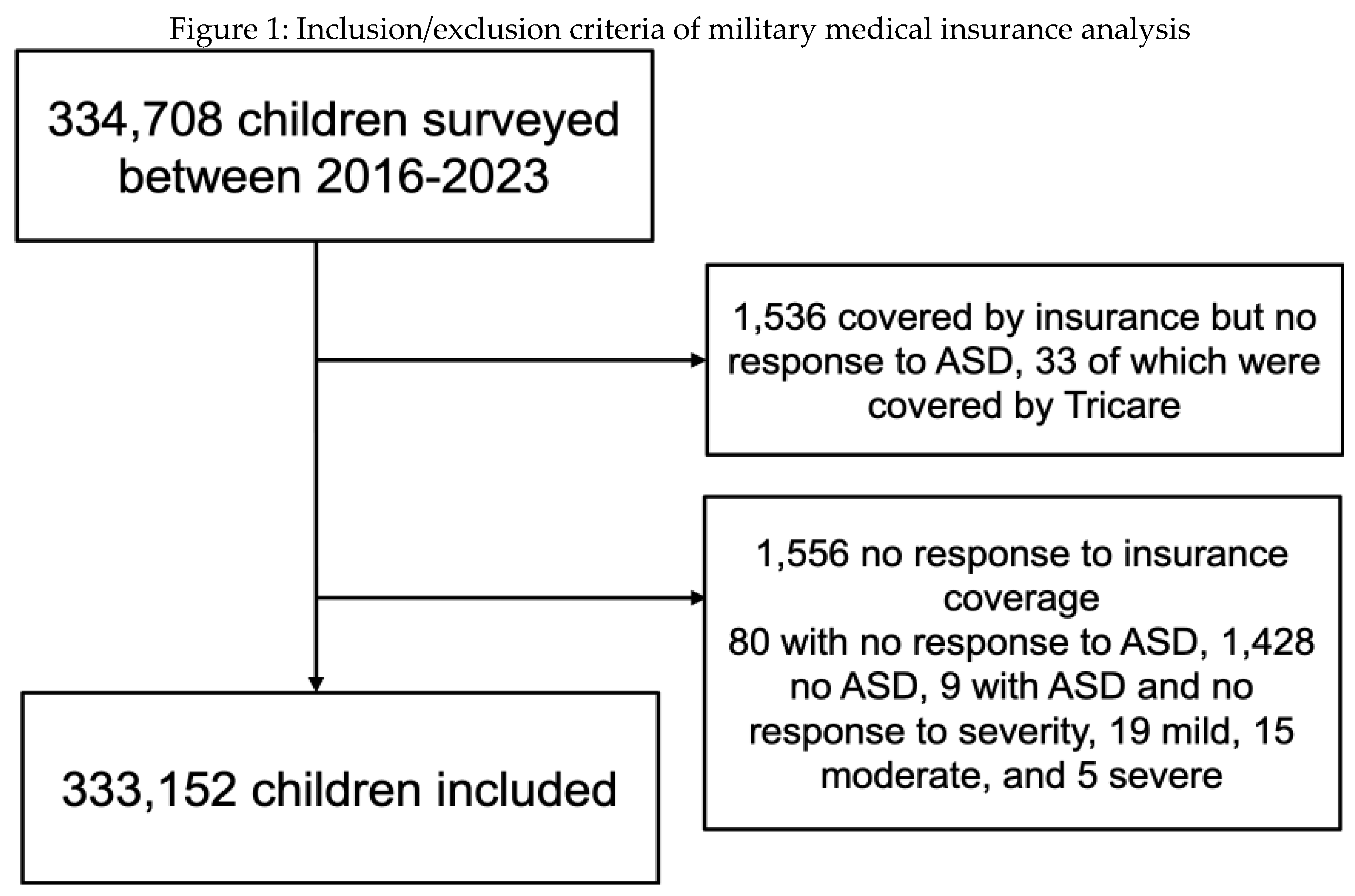

In the 8 years of the USCB’s NSCH caregivers of 334,708 children have been successfully surveyed where ASD may be related to Tricare (or other military insurance) coverage. Of the available child health records 1,539 were excluded for no response to the ASD question, and 1,556 were excluded for no response to insurance coverage (

Figure 1).

Of the remaining 333,152 children, in those 8 years 322,282 children (

Table 1) were covered by non-military insurance at the time of survey, and 9,929 (or 3.194%) were reported to have ASD. In those same years 10,870 children were covered by military insurance at the time of the survey, and 429 (or 4.122%) were reported to have ASD (Supplemental Table S2). That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.2904 (1.1665-1.4244, p-value<0.0001). Adjusting yields an odds ratio of 1.3073 (1.1835-1.4440, p-value<0.0001) (Figure 3).

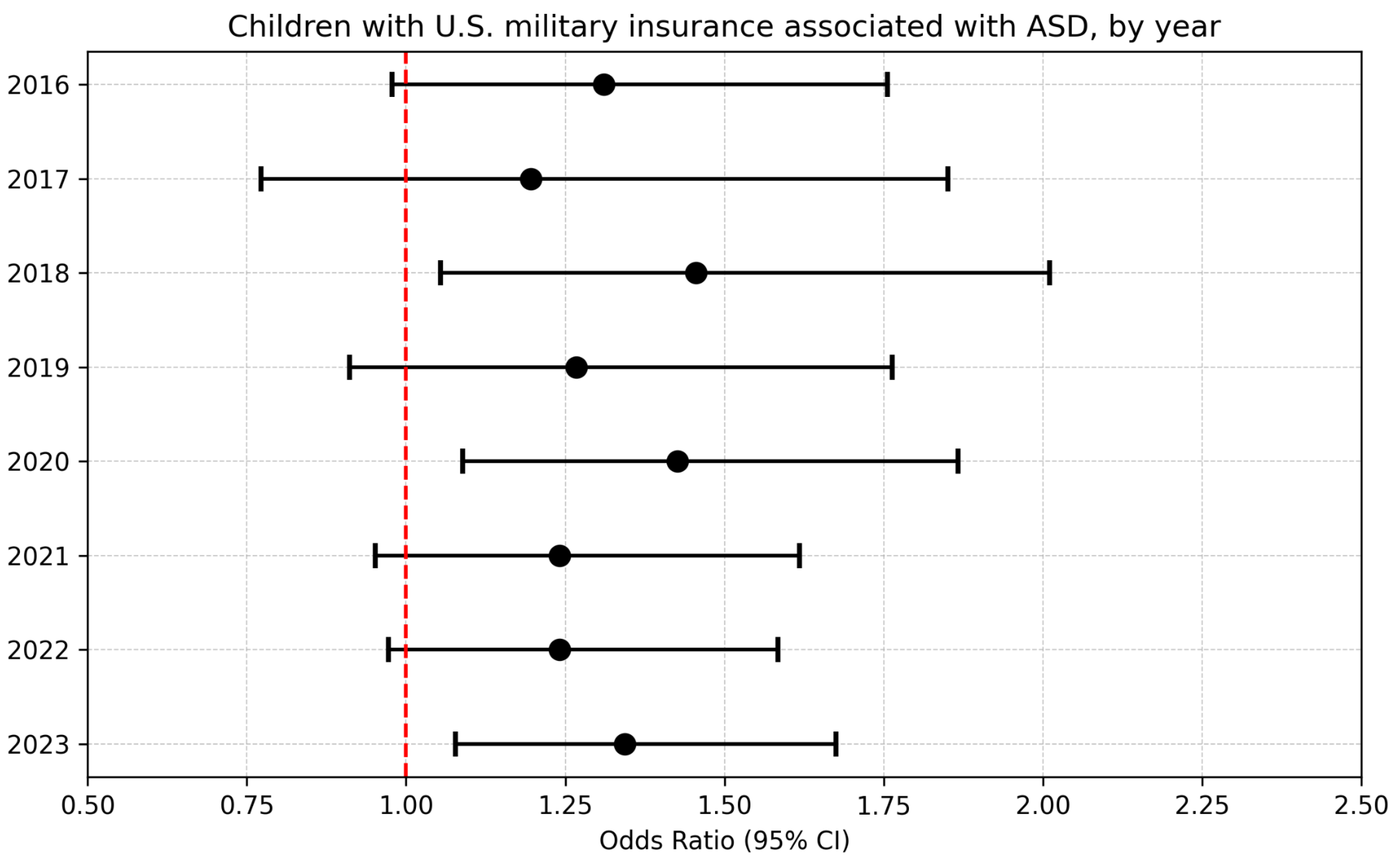

The yearly delineation of ASD prevalence among military insured children is observed in

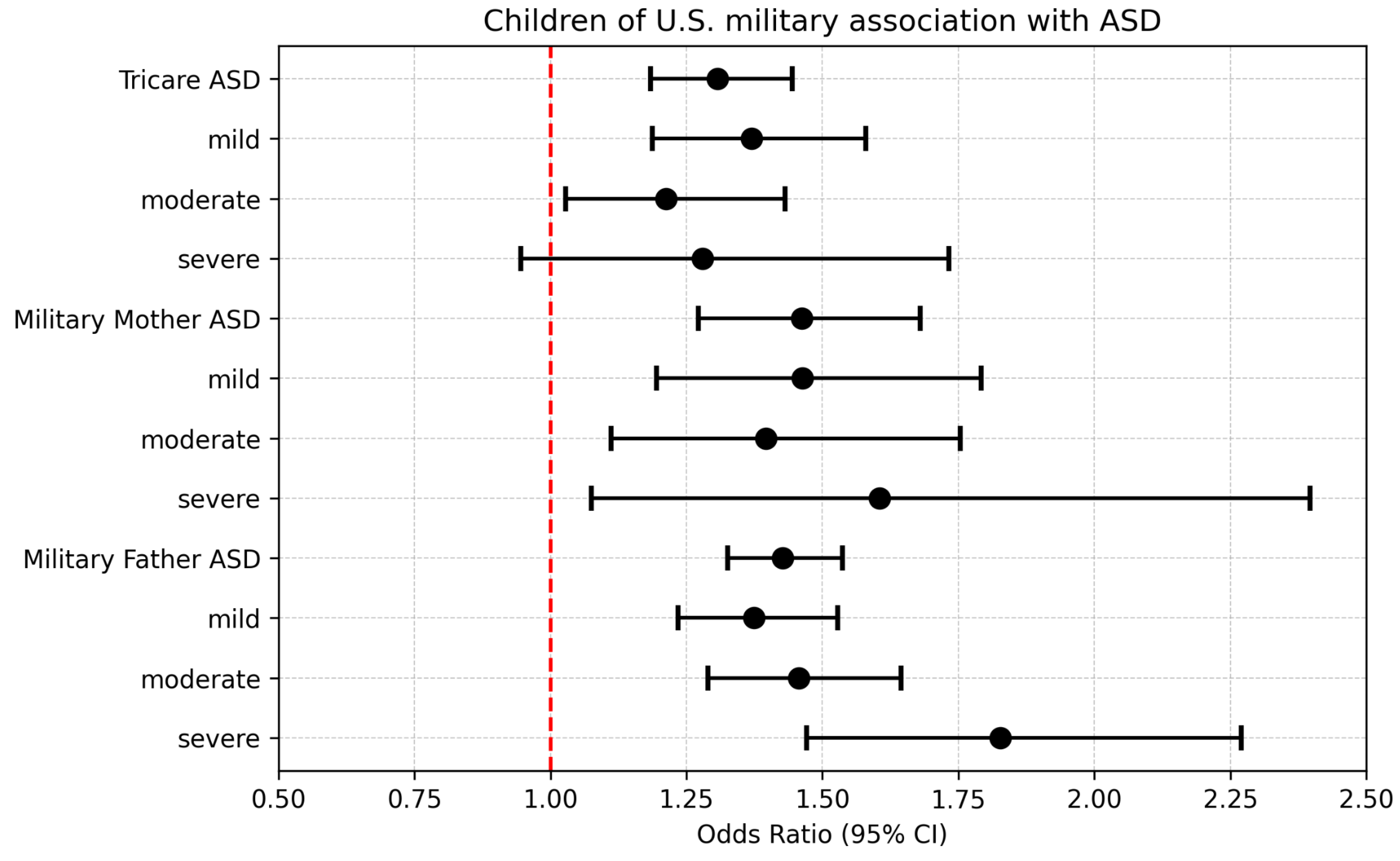

Figure 2. Of note, for all years measured, the ratio of ASD children is greater for Tricare (or other military insurance) covered children than the civilian counterpart insurance coverage. The ASD determination of severity (mild, moderate or severe) as it relates to U.S. military association is observed in

Figure 3, and shows a greater association for children of U.S. military servicemembers than the civilian counterparts, statistically significantly so in every category and sub-category except for severe ASD children covered by U.S. military insurance.

US Military Service

Maternal:

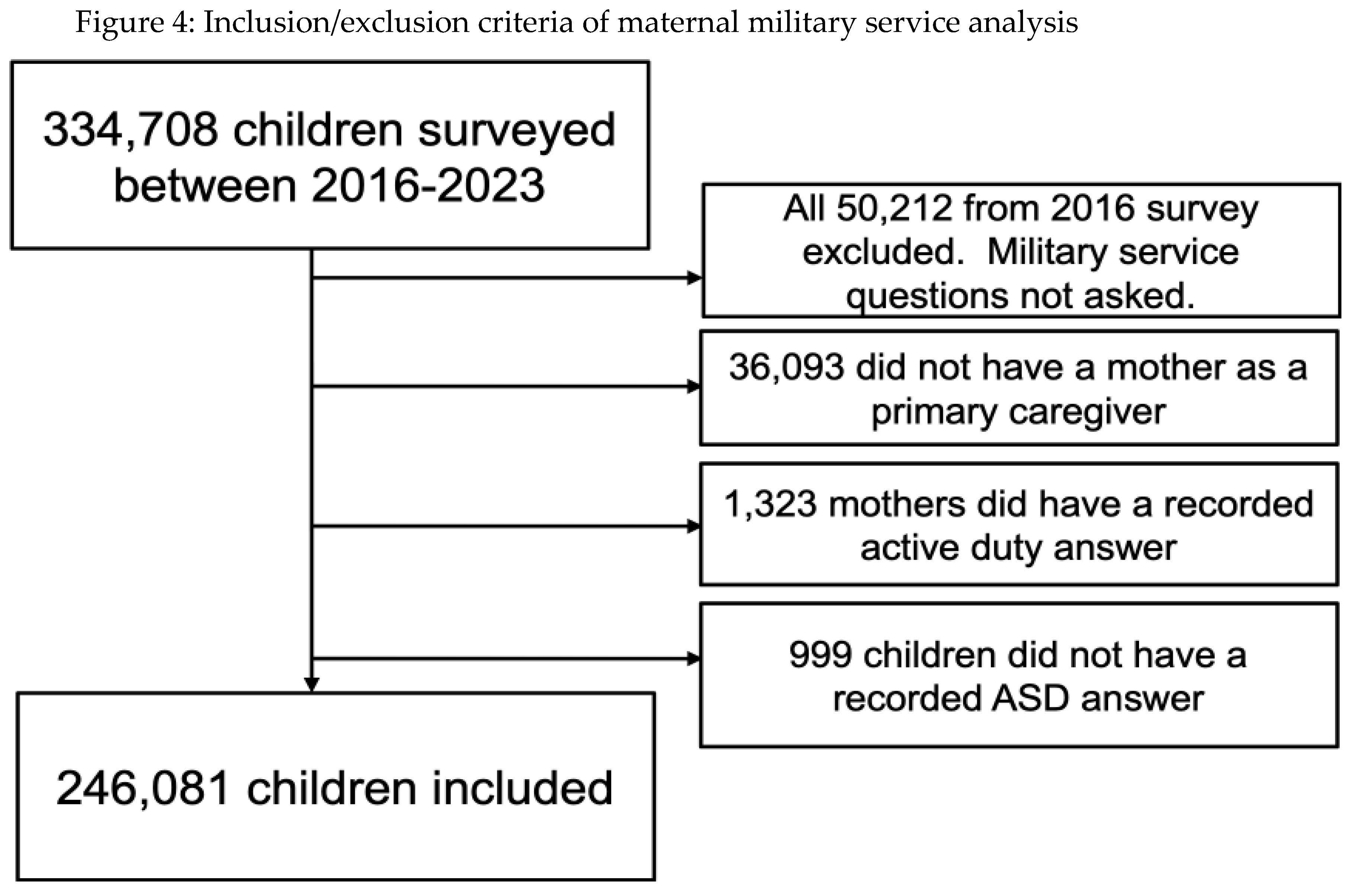

In the 8 years of the USCB’s NSCH caregivers of 334,708 children have been surveyed, military service of the mother was not asked in the first year (excludes 50,212 children). The study excluded 36,093 children who did not have a mother as a primary caregiver, 1,323 children whose questionnaire did not record an answer for the mother’s active duty question, and 999 children whose questionnaire did not record an answer for ASD. This yields 246,081 children who were successfully surveyed where ASD may be related to active duty status of a mother (

Figure 4).

In those 7 years 241,417 mothers were designated as non-military by their response (

Table 1), and 7,552 (or 3.229%) were reported to have ASD children (Supplemental Table S4).

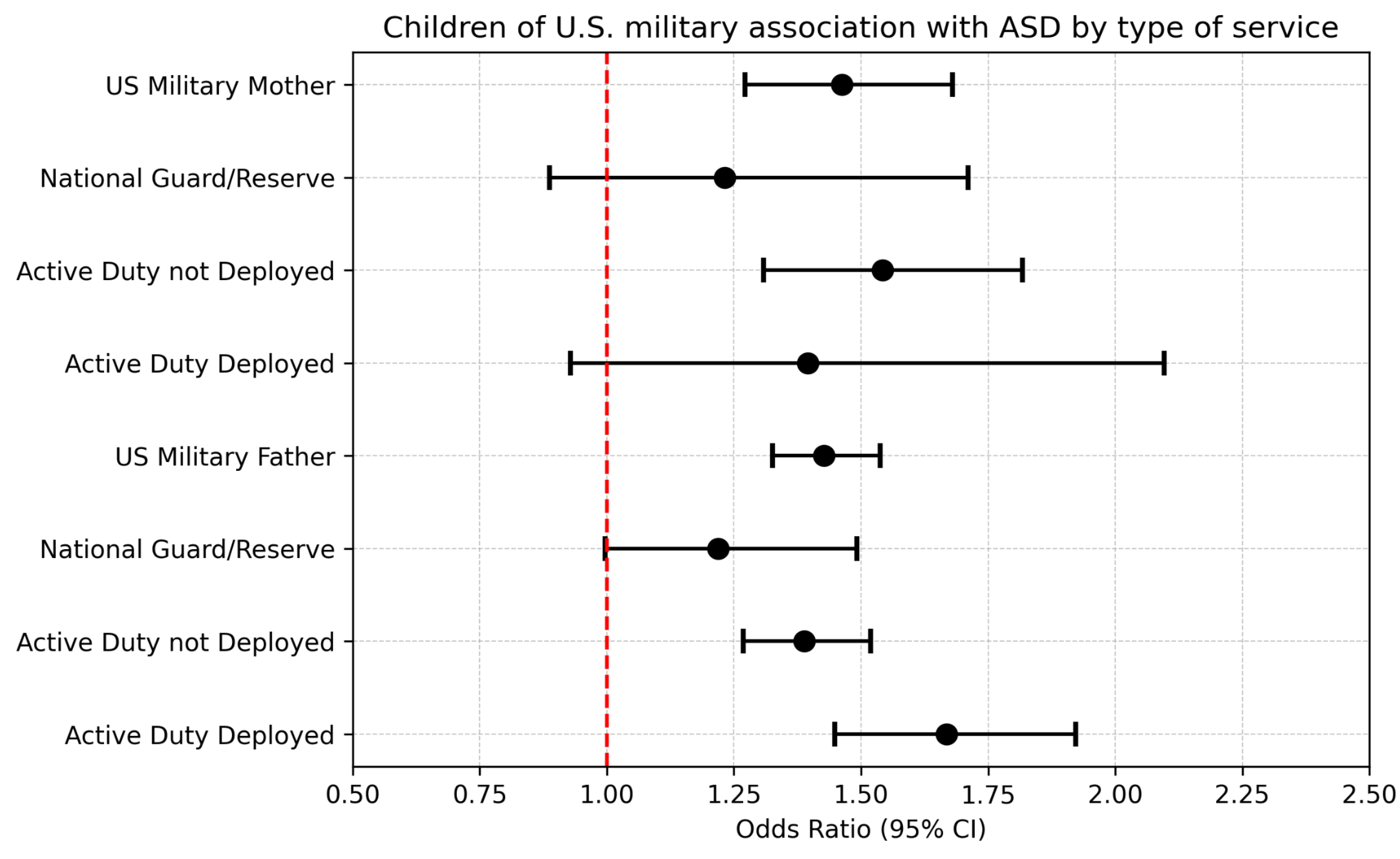

In those same years, 969 mothers were designated as National Guard/Reserve military service, and 38 (or 4.082%) were reported to have ASD children. That yields a non-statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.2640 (0.8880-1.7497, p-value=0.1645) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.2320 (0.8875-1.7104, p-value=0.2125) (

Figure 5).

Active duty not deployed mothers numbered 3,210, and 156 (or 5.108%) were reported to have ASD children. That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.5818 (1.3358-1.8617, p-value<0.0001) and an adjusted statistically significant odds ratio of 1.5420 (1.3083-1.8174, p-value<0.0001).

Active duty and deployed mothers numbered 485, and 25 (or 5.435%) were reported to have ASD children. That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.6830 (1.0770-2.5184, p-value=0.0176) and a non-statistically adjusted odds ratio of 1.3951 (0.9282-2.0968, p-value=0.1092).

For any level of a mother’s military service (National Guard/Reserve, Active Duty Not Deployed, and Active Duty Deployed) the statistically significant adjusted odds ratio is 1.4619 (1.2720-1.6801, p-value<0.0001). As seen in

Figure 3, for mild ASD it’s OR=1.4633 (1.1954-1.7914, p-value=0.0002); for moderate ASD it’s OR=1.3962 (1.1115-1.7539, p-value=0.0041); for severe ASD it’s OR=1.6050 (1.0750-2.3963, p-value=0.0207).

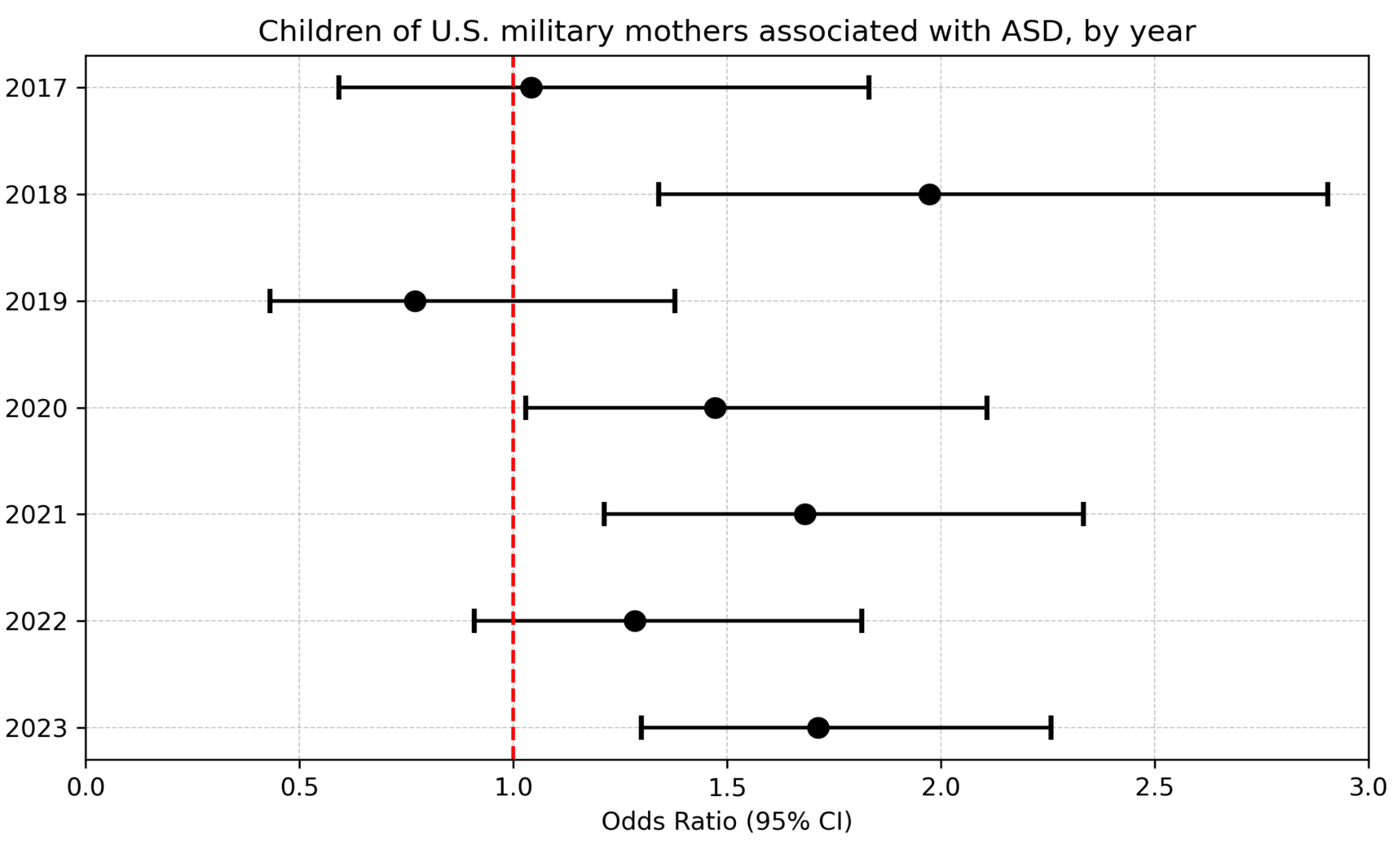

Figure 5 shows ASD diagnosis is associated with mothers of military service, an elevated risk for every type of military service. The yearly delineation of ASD prevalence among children of U.S. military mothers is observed in

Figure 6. Of note, except for 2019, all other years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military mothers than that of civilian mothers, statistically significantly so in 4 of the 7 years.

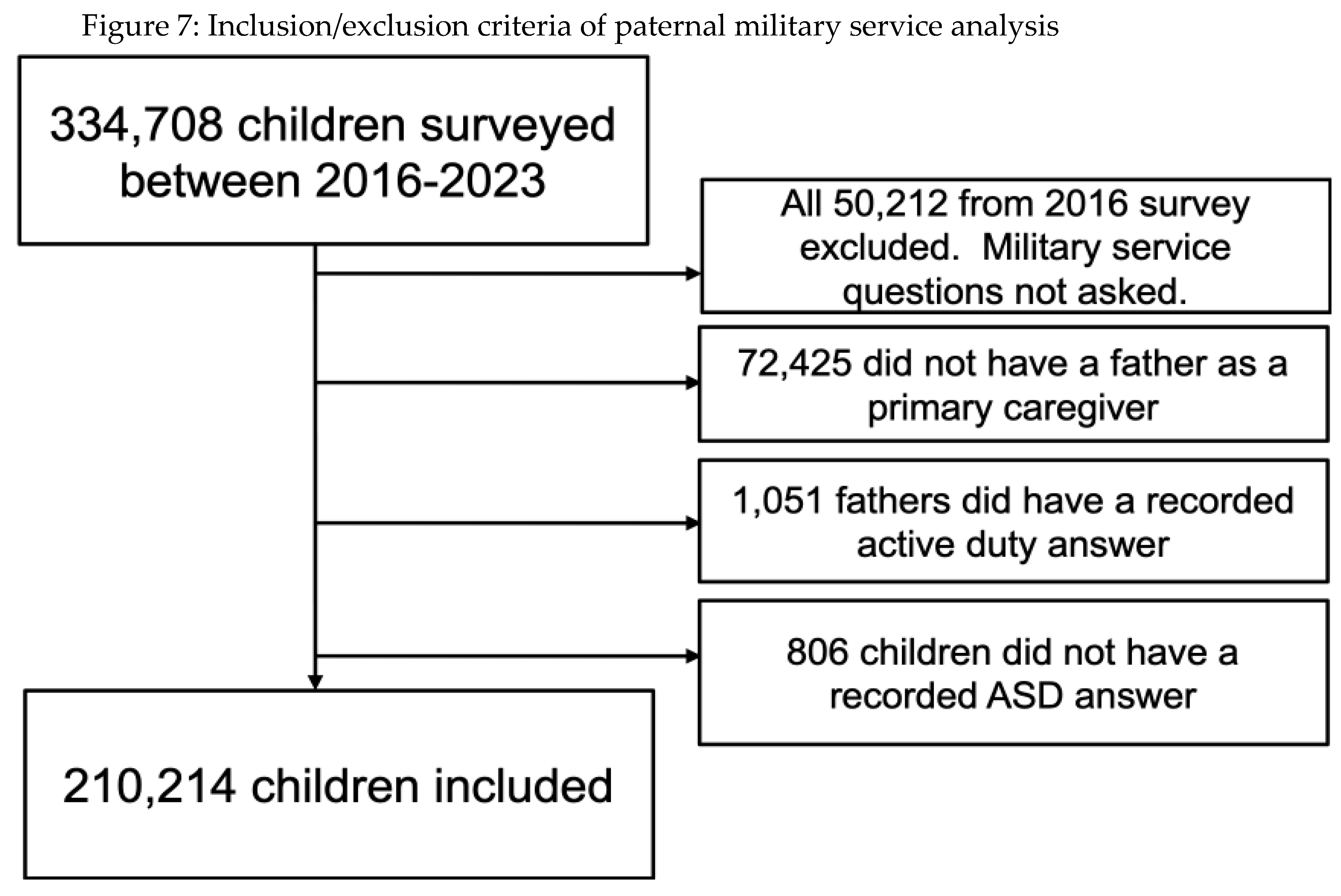

Paternal:

In the 7 years of the USCB’s NSCH caregivers of 334,708 children have been surveyed, military service of the father was not asked in the first year (excludes 50,212 children). The study excluded 72,425 children who did not have a father as a primary caregiver, 1,051 children whose questionnaire did not record an answer for the father’s active duty question, and 806 children whose questionnaire did not record an answer for ASD. This yields 246,081 children who were successfully surveyed where ASD may be related to active duty status of a father (

Figure 7).

In those 7 years 187,646 fathers of children were designated as non-military by their response (

Table 1), and 4,981 (or 2.727%) were reported to have ASD (Supplemental Table S6).

In those same years, 3,061 fathers of children were designated as National Guard/Reserve military service, and 102 (or 3.447%) were reported to have ASD. That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.2641 (1.0253-1.5436, p-value=0.0236) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.2193 (0.9965-1.4920, p-value=0.0541) (

Figure 5).

Active duty not deployed fathers numbered 14,802, and 556 (or 3.903%) were reported to have ASD children. That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.4313 (1.3067-1.5654, p-value<0.0001) and an adjusted statistically significant odds ratio of 1.3879 (1.2677-1.5194, p-value<0.0001).

Active duty and deployed fathers numbered 4,705, and 218 (or 4.858%) were reported to have ASD children. That yields a statistically significant unadjusted odds ratio of 1.7817 (1.5436-2.0478, p-value<0.0001) and a statistically adjusted odds ratio of 1.6686 (1.4488-1.9218, p-value<0.0001).

For any level of a father’s military service (National Guard/Reserve, Active Duty Not Deployed, and Active Duty Deployed) the statistically significant adjusted odds ratio is 1.4274 (1.3255-1.5371, p-value<0.0001). As seen in

Figure 3, for mild ASD it’s OR=1.3737 (1.2347-1.5284, p-value<0.0001); for moderate ASD it’s OR=1.4564 (1.2898-1.6445, p-value<0.0001); for severe ASD it’s OR=1.8273 (1.4712-2.2695, p-value<0.0001).

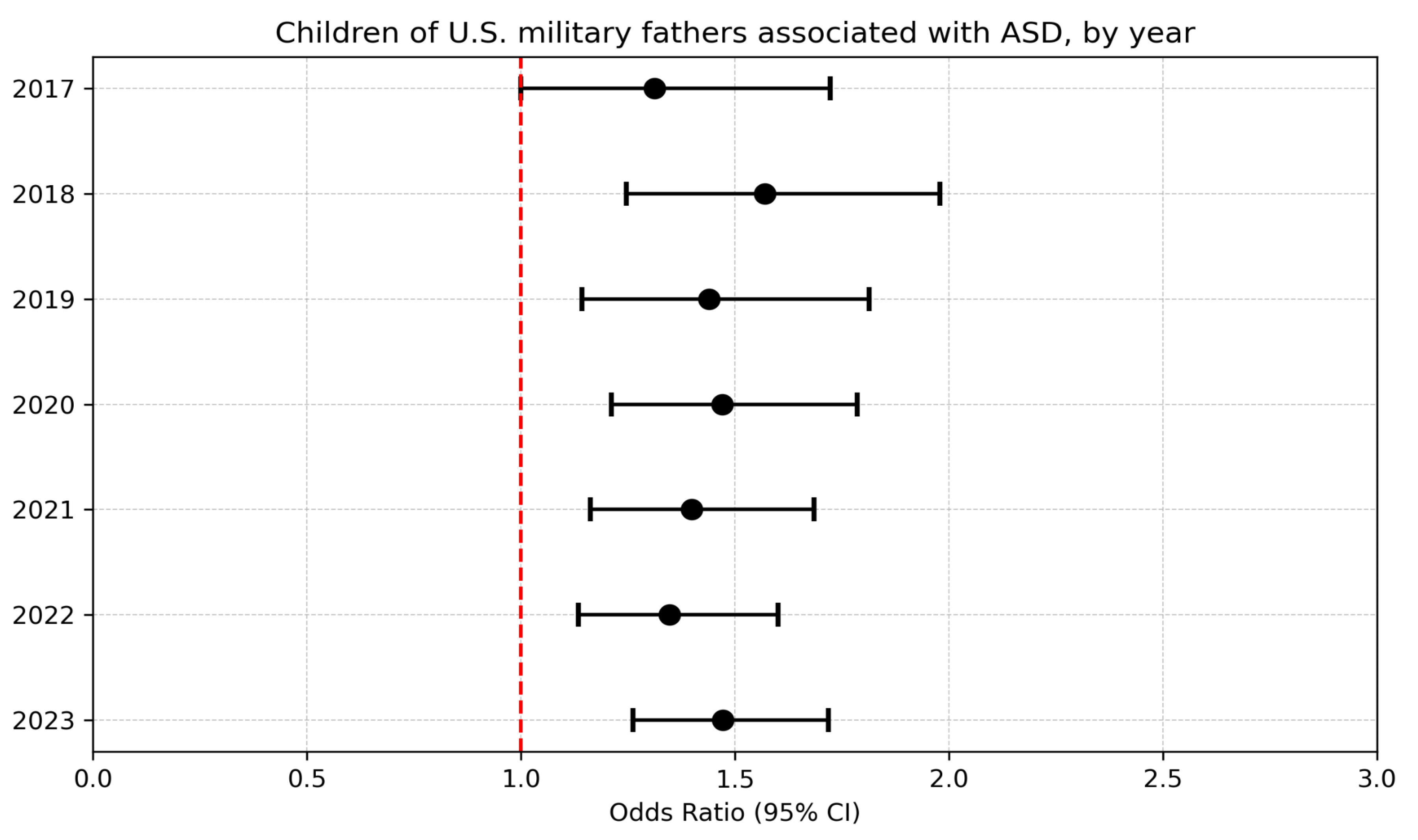

Figure 5 shows ASD diagnosis is associated with fathers of military service, an elevated risk for every type of military service. Importantly, the rate of association increases with the level of engagement (ordered by: National Guard/Reserve; Active Duty not Deployed; Active Duty Deployed). The yearly delineation of ASD prevalence among children of U.S. military fathers is observed in

Figure 8. Of note, for all years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military fathers than that of civilian fathers, statistically significantly so in 6 of the 7 years.

Discussion

The USCB, officially the Bureau of the Census, is an agency within the US Department of Commerce. The NSCH results present a large disparity in ASD prevalence between children of US military families and their civilian family counterparts.

The health disparity described herein is seriously concerning. Children covered by military insurance are 30.73% more likely to have ASD. A surveyed child with a military service mother is 46.19% more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than a non-military service mother. A surveyed child with a military service father is 42.74% more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than a non-military service father. That the added risk also increases with the severity of ASD (e.g. children of military service fathers 37.37% more likely for mild ASD, 45.64% more likely for moderate ASD, and 82.73% more likely for severe ASD) implies an underlying mechanism that is a severity-response to exposure.

There are non-health related possible reasons for observing the disparity highlighted in this analysis. A counter-hypothesis is survey bias, that caregivers of ASD children and of a military service family may be more likely to complete a USCB NSCH survey. Alternatively selection bias, active duty mothers or fathers (past or present) may be more likely to adopt ASD children.

Another counter-hypothesis is the possibility that the factors that lead to military recruitment amplify the risk factors for having an ASD child. Though the Autism Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network have recently reported [

4] characteristics aligned with recent correlation in ASD (such as race and social determinants of health) which may align with US military recruitment, these findings are not consistent over past years and are not punctuated enough to explain the dramatic disparity found in this study. Additionally, a bias of medical diagnosis practices may predilect ASD diagnoses.

Though the causal network of ASD is not fully defined, toxic exposures play a large part in metabolic and neurologic dysfunction [

5]. US military members are exposed to toxins and toxic environments beyond the typical civilian toxic exposure. Examples such as: Camp Lejuene’s water contamination [

6]; perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) [

7,

8]; expanded vaccinations, especially in Areas of Responsibility [

9]. Childhood ASD and its relationship to toxic exposure to the child or through the mother or father due to military service is a hypothesis that cannot be ignored and must be investigated.

Conclusions

This analysis inspected the USCB’s NSCH data and found a statistically significant signal to ASD and the US military. Over a course of 8 years, children contemporaneously covered by Tricare (or other military insurance) were 30.73% more likely than civilian insurance coverage to be diagnosed with ASD. Over the course of 7 years, children of mothers with any military service were 46.19% more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than children of non-military service mothers, with with the greatest portion diagnosed with severe autism (46.33% for mild ASD, 39.62% for moderate ASD, and 60.50% for severe ASD). Commensurately, children of fathers with any military service were 42.74% more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than children of non-military service fathers, with increasing severity (37.37% for mild ASD, 45.64% for moderate ASD, and 82.73% for severe ASD). Though there are several explanations for the results of this analysis, child exposure to toxins, either directly or through their parents, cannot be ignored and must be investigated with all due haste. Such an investigation with domain-specific data would ideally link the mother-child and father-child medical records and include suspected or shared toxic exposure of either mother or father and their children.

References

- Organization for Autism Research & Southwest Autism Research and Resource Center (2010). Life Journey through Autism: A Guide for Military Families. https://researchautism.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/A_Guide_for_Military_Families-1.pdf.

- Chikezie-Darron, O., Sakai, J., & Tolson, D. (2025). Analysis of Disparities in Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Military Health System Pediatrics Population. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 1080. [CrossRef]

- Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. (n.d.). The National Survey of Children's Health. https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/NSCH.

- Shaw KA, Williams S, Patrick ME; et al. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ 2025;74(No. SS-2):1–22. [CrossRef]

- Modabbernia, A. , Velthorst, E. & Reichenberg, A. Environmental risk factors for autism: An evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Molecular Autism 8, 13 (2017). [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Camp Lejeune water contamination. https://www.va.gov/disability/eligibility/hazardous-materials-exposure/camp-lejeune-water-contamination/. Archived at: http://archive.today/2025.11.18-214359/https://www.va.gov/disability/eligibility/hazardous-materials-exposure/camp-lejeune-water-contamination/.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/pfas.asp. Archived at: http://archive.today/2025.11.18-214412/https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/pfas.asp.

- Jiwon Oh, Deborah H. Bennett, Antonia M. Calafat, Daniel Tancredi, Dorcas L. Roa, Rebecca J. Schmidt, Irva Hertz-Picciotto, Hyeong-Moo Shin, Prenatal exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in association with autism spectrum disorder in the MARBLES study, Environment International, Volume 147, 2021, 106328, ISSN 0160-4120. [CrossRef]

- Defense Health Agency. (n.d.). Vaccine recommendations by AOR. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Health-Readiness/Immunization-Healthcare/Vaccine-Recommendations/Vaccine-Recommendations-by-AOR. Archived at: http://archive.today/2025.11.18-215258/https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Health-Readiness/Immunization-Healthcare/Vaccine-Recommendations/Vaccine-Recommendations-by-AOR.

Figure 1.

Tricare and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. We exclude 1,536 of covered children with no response to the ASD question (33 of whom were covered by Tricare). We exclude 1,556 for no response to insurance coverage. Of those, 80 additionally had no response to the ASD question, 1,428 responded to no ASD, 9 indicated ASD and no severity. Of the remaining excluded ASD children, 19 were mild, 15 were moderate, and 5 were severe.

Figure 1.

Tricare and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. We exclude 1,536 of covered children with no response to the ASD question (33 of whom were covered by Tricare). We exclude 1,556 for no response to insurance coverage. Of those, 80 additionally had no response to the ASD question, 1,428 responded to no ASD, 9 indicated ASD and no severity. Of the remaining excluded ASD children, 19 were mild, 15 were moderate, and 5 were severe.

Figure 2.

ASD disposition of Tricare or other military insurance currently covered children. For all years measured, the ratio of ASD children is greater for Tricare children than the civilian counterpart insurance coverage, statistically significantly so in 3 of the 8 years (Supplemental Table S3).

Figure 2.

ASD disposition of Tricare or other military insurance currently covered children. For all years measured, the ratio of ASD children is greater for Tricare children than the civilian counterpart insurance coverage, statistically significantly so in 3 of the 8 years (Supplemental Table S3).

Figure 3.

Children of U.S. military servicemembers with ASD by type of association (U.S. military insurance (Supplemental Table S2), maternal military service (Supplemental Table S4), and paternal military service (Supplemental Table S6)) and severity (mild, moderate, severe). For all years measured, the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military servicemembers than the civilian counterparts, statistically significantly so in every category and sub-category except for severe ASD children covered by U.S. military insurance.

Figure 3.

Children of U.S. military servicemembers with ASD by type of association (U.S. military insurance (Supplemental Table S2), maternal military service (Supplemental Table S4), and paternal military service (Supplemental Table S6)) and severity (mild, moderate, severe). For all years measured, the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military servicemembers than the civilian counterparts, statistically significantly so in every category and sub-category except for severe ASD children covered by U.S. military insurance.

Figure 4.

Active duty and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. All 50,212 from the 2016 survey were excluded as the military service question was not asked. Of children on record, 36,093 did not have a mother as a primary caregiver. Of the remaining, 1,323 did not have a recorded active duty answer and 999 children did not have a recorded ASD answer.

Figure 4.

Active duty and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. All 50,212 from the 2016 survey were excluded as the military service question was not asked. Of children on record, 36,093 did not have a mother as a primary caregiver. Of the remaining, 1,323 did not have a recorded active duty answer and 999 children did not have a recorded ASD answer.

Figure 5.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military mothers and fathers (past or present) is associated with the type of military service (National Guard/Reserve, Active Duty not Deployed, and Active Duty Deployed). For all service types measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents.

Figure 5.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military mothers and fathers (past or present) is associated with the type of military service (National Guard/Reserve, Active Duty not Deployed, and Active Duty Deployed). For all service types measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents.

Figure 6.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military mothers (past or present) by year. Except for 2019, all other years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents, statistically significantly so in 4 of the 7 years.

Figure 6.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military mothers (past or present) by year. Except for 2019, all other years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents, statistically significantly so in 4 of the 7 years.

Figure 7.

Active duty and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. All 50,212 from the 2016 survey were excluded as the military service question was not asked. Of children on record, 72,425 did not have a father as a primary caregiver. Of the remaining, 1,051 did not have a recorded active duty answer and 806 children did not have a recorded ASD answer.

Figure 7.

Active duty and ASD inclusion criteria. The USCB surveyed 334,708 children between 2016 and 2023. All 50,212 from the 2016 survey were excluded as the military service question was not asked. Of children on record, 72,425 did not have a father as a primary caregiver. Of the remaining, 1,051 did not have a recorded active duty answer and 806 children did not have a recorded ASD answer.

Figure 8.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military fathers (past or present) by year. For all years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents, statistically significantly so in 6 of the 7 years (Supplemental Table S5).

Figure 8.

The ASD disposition in children of U.S. military fathers (past or present) by year. For all years measured the ratio of ASD children is greater for children of U.S. military parents than that of civilian parents, statistically significantly so in 6 of the 7 years (Supplemental Table S5).

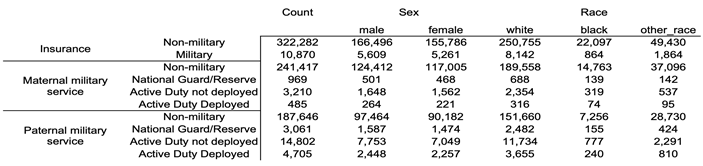

Table 1.

Absolute count of all children, by sex, and by race for the three groups studied. Age distributions for child and parent (where relevant) included in Supplemental Table S1.

Table 1.

Absolute count of all children, by sex, and by race for the three groups studied. Age distributions for child and parent (where relevant) included in Supplemental Table S1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).