Introduction

A commonly held view among drug discovery scientists is that “potency is the easy part.” According to this view, it is simple to find compounds that bind to the desired target with nanomolar affinity and exert a desirable biological effect, i.e. are “active” or “potent.” Unfortunately, potency is necessary but not sufficient; as Ralph Hirschmann said, “Discovering an active compound is relatively easy, discovering an important new drug remains unbelievably difficult [

1]. The challenges that must be overcome to produce a useful medicine are well understood: demonstrating pharmacological benefit; achieving sufficient selectivity, DMPK, and safety; being able to manufacture the medicine; designing and executing appropriate clinical trials; understanding the true medical benefit versus alternative therapies; and so forth. Successful drug discovery teams understand and address these diverse challenges using a wide variety of strategies [

2].

Potency is here defined as the concentration of drug required to achieve a given biological effect in a biochemical or cellular assay, while efficacy is the degree of pharmacological response at a given dose [

3]. [

Figure 1]. Both potency and efficacy measure the effect of a drug; they are functional readouts. Conversely, binding affinity is the strength or tightness of the interaction between the biomolecule and the drug.

While potency is not the whole story, being able to optimize potency dramatically enhances our ability to discover breakthrough medicines. When we can optimize the binding of our drugs to the desired target, it increases the chance of achieving the desired pharmacological response; conversely, when binding to an unintended target, it may lead to toxic effects, or to the metabolic elimination of the drug, or to a tissue distribution which prevents the drug from reaching the desired site of action. Each event, favorable or unfavorable, is driven by intermolecular interactions between the drug and a biomolecule (typically a protein or nucleic acid) in the body. Therefore, the pursuit of improved strategies to measure, predict, and modulate affinity will have profound benefits for drug discovery. I am arguing that we do not put enough effort into optimizing affinity.

For clarity, please note that I did not say “maximize” affinity. Optimal affinity depends on the specific case – the drug modality, the pharmacological mechanism of action, the kinetics of binding, and other factors. For simple inhibitors or antagonists, it will generally be true that maximal affinity is better. However, for other situations, the optimal affinity will not be the greatest achievable affinity. This will be discussed below.

To be abundantly clear, I am certainly not suggesting that the optimization of a drug’s other properties is unimportant [

3]. Successful drugs must balance multiple parameters. Drugs need to reach the site of action in high enough concentration for a long enough period to enable the desired effect. Drugs must also be safe, formulatable, and manufacturable. But any drug must first have sufficient intermolecular interactions to enable a pharmacological response.

The Advantages of Affinity

There are seven distinct advantages that result from optimizing affinity.

PROBLEM: Starting points on a drug discovery campaign are generally quite weak – often in the mid-μM or even the mM range. The conversion of these starting points to potent lead molecules, whether by de novo design, optimization of screening hits, or modification of prior known compounds, is generally a slow and error-prone process. At these early stages, the goal is to achieve the threshold level of affinity necessary to exhibit cellular potency.

BENEFIT: In addition to time saved, potent tool compounds (lacking fully optimized DMPK properties) enable rapidly evaluating and de-risking novel targets, while providing insights into possible off-target effects. The ability to rapidly achieve potency also encourages the exploration that leads to additional diverse chemical starting points, which is hugely valuable for confirming what is learned from target evaluation studies. Similar results achieved with several diverse chemotypes are inherently more trustworthy. Finally, potent tool compounds may provide early insights into possible off-target effects leading to toxicity, giving the team a head start at crafting their design strategy and experimental workflows.

- 2.

Achieve greater potency.

PROBLEM: Teams often struggle to create molecules with sufficient potency even on well-understood targets.

BENEFIT: Improved binding affinity may lead to greater potency (i.e. a pharmacological response at a lower dose) or greater efficacy (a greater pharmacological response at the same dose). See

Figure 1. Improved potency and efficacy,

when achieved without worsening the ADME properties of the drug, can lead to lower dose; this reduces the risk of off-target toxicity and may enable alternate routes of administration [

4]. Finally, greater affinity enables complex “rule-breaker” molecules to be dosed orally because, despite low oral bioavailability, sufficient concentrations can be delivered to achieve the desired pharmacological benefit. Recent compelling examples include the PCSK9 inhibitor enlicitide [

5] and the IL-23 antagonist icotrokinra [

6].

- 3.

Accelerate the lead optimization process.

PROBLEM: Drug discovery is a frustrating multi-parameter optimization process. While other properties such as bioavailability are being optimized, affinity can be lost, requiring additional rounds of optimization. Even in late-stage lead optimization, a high percentage of compounds lack the requisite affinity to become drug candidates.

BENEFIT: Maintaining the desired levels of affinity and selectivity while optimizing other properties reduces the time and cost of lead optimization and enables exploration of additional lead series. Note also that if fewer resources are needed to optimize the drug candidate, that enables putting effort into additional lead series.

- 4.

Optimize selectivity against closely related targets.

PROBLEM: Even in well-studied and successful gene families such as the kinases and GPCRs, selectivity remains a major challenge. (For precision oncology medicines, we sometimes require selective binding to

mutated forms of the target of interest [

7].) Compounds that bind to closely related “anti-targets” may be too toxic or require dose reduction to avoid toxicity, thereby lowering their effectiveness. In addition, the drugs may not account for human genetic variation either in the targets (leading to lack of benefit) or the anti-targets (leading to toxicities) within those genetic sub-populations.

BENEFIT: Reducing interactions with “anti-targets” eliminates promiscuous molecules and leads to safer medicines. Future selectivity challenges involve the design of

polypharmacological [

8] agents or

proteoform-specific [

9] agents – molecules that bind to a specific conformation, multi-target complex, or post-translationally modified form of a protein.

- 5.

Embolden teams to pursue synthetically challenging compounds.

PROBLEM: Structure-activity relationships are inevitably quite complex. Even “trivial” changes, such as adding a methyl [

10] or fluorine [

11] can have profound effects but be difficult to synthesize. Naturally, more extensive chemical medications are often more problematic. (This is why continued investment in advancing the art of chemical synthesis is crucial. [

12,

13]) Any synthetically challenging molecules will be deprioritized without a compelling case.

BENEFIT: A greater ability to predict affinity would embolden a team to rise to the synthetic challenge. In the best case, it would enable synthesis of a superior compound that would otherwise never be made.

- 6.

Explore diverse chemical space.

PROBLEM: It is well understood that any given chemical series may ultimately fail, so finding multiple, diverse, novel, attractive chemotypes that offer fundamentally different molecular solutions to the design problem increases the odds of producing a clinical candidate. Many teams do, at the hit to lead stage, pursue multiple series to identify a preferred chemotype. However, even if a team begins with several interesting chemical series, these are typically winnowed out rapidly, and teams rarely put significant efforts on multiple series in the late lead optimization stage.

BENEFIT: Identifying and pursuing multiple, diverse, novel, attractive chemotypes is one of the best ways to increase the odds of producing a clinical candidate. Having multiple leads provides both insurance (in case the first series fails) and the potential for better medicines (if the second series ultimately proves superior). Therefore, teams with a superior understanding of affinity gain a considerable advantage because they can navigate the exploratory process far more effectively.

- 7.

Avoid the “avoid-ome.”

PROBLEM: The ADME properties and potential safety liabilities of drug candidates are dependent on the interactions of drug candidates with a large and diverse class of proteins such as cytochrome P450s, organic anion transporters, hERG, PXR, serum albumin, and so forth. At a rough estimate there are on the order of a thousand such proteins throughout the body, with more than 250 well characterized in the liver alone [

14]. The size and diversity of this set of anti-targets, which has been called the “avoid-ome,” [

15] creates a daunting kind of selectivity challenge for drug discovery teams.

BENEFIT: By reducing or eliminating the interactions that drug candidates make with anti-targets responsible for undesirable ADME/tox consequences, we can expect both more and better drug candidates. Gradually, the three-dimensional structures of these avoid-ome proteins will be solved, and reliable high-throughput, low-cost assays will be developed to measure the interactions of our drugs with these anti-targets. Our ability to minimize the interactions of our drug candidates with the avoid-ome targets will dramatically speed the lead optimization process.

Possible Objections to an Emphasis on Affinity

It is worth considering a wide range of possible objections to the emphasis that I am placing on affinity. The following list summarizes many discussions with scientists around the world during the past decade.

Objection: You are casting drug discovery as a problem of binding affinity and ignoring everything else - that is your hammer.

No. I am not suggesting that we ignore other properties! I agree that many other complex properties contribute to achieving low dose effective medicines. However, intermolecular interactions drive biological consequences; understanding binding is fundamental. I am arguing that somewhat more emphasis should be placed on optimizing these interactions.

Objection: How can you measure affinity in a relevant way? Experiments in a test tube do not incorporate the complex environment within a living organism.

I agree one must be mindful of the risk that a simple biochemical measurement will not capture important subtleties of the intermolecular environment in which the drug interacts with its target. However, empirical evidence shows there is a reasonable correlation between biochemical affinity and cellular potency; biochemical measurements generally provide valuable information.

Objection: Lead optimization teams achieve potency already – what is the problem?

The process is

highly inefficient. Even on late-stage projects, a significant percentage (typically one-third to two-thirds) of the compounds being made do not bind with sufficient affinity and selectivity to become drug candidates [

16].

The process is painfully slow. Teams will typically spend at least a year – and usually much longer -- optimizing their lead compounds [

16].

Most teams put significant effort only into a single lead series, increasing the risk of failure.

Many teams fail to produce a development candidate, especially when working on challenging targets.

Objection: More potent drugs will hit structurally related anti-targets harder, leading to toxicology risks.

Objection: Isn’t the real point that you need to improve potency – the activity of compounds in cellular assays?

Yes, cellular potency will help achieve an effective low-dose medicine [

Figure 1], and in most cases, greater affinity will help achieve greater cellular potency. Further, for agonists, being able to optimize the precise intermolecular interactions between ligand and target will help produce the desired pharmacological effects.

Objection: What about phenotypic programs with unknown targets?

Objection: My biggest problem is target selection and biological validation.

Often the best way to assess a target is with “tool” compounds, which complement information available from human genetics or knock-out or knock-down technologies. Such tool compounds must be reasonably potent, selective, and ideally possess DMPK properties suitable (not optimized) for dosing in a target animal. Shortening the time required to produce such tool compounds would dramatically improve the target validation process.

Objection: My biggest problem is toxicology.

Optimized affinity (coupled with maintaining excellent ADME properties) will enable a lower dose, reducing the chance of random off-target toxicities.

Improved selectivity against neighboring “anti-targets” also reduces toxicological risk.

Having multiple structurally distinct chemotypes increases the chance of project success because toxic effects seen in preclinical studies often differ between chemical series.

Eliminating interactions with “avoid-ome” targets will further reduce toxicological risk and improve ADME.

Objection: How does affinity help me with respect to novel modalities such as glues and heterobifunctionals?

The field of proximity enhancement is progressing rapidly [

17]. Such drugs share a common mechanistic trait: they form ternary complexes with two biomolecules. The analysis of such three-body systems is complex and counter-intuitive [

18]. Understanding the mechanisms of protein degradation are equally challenging [

19]. In such complex three-body systems, a deeper understanding of the relationship between the strength of the intermolecular interactions and the resulting pharmacology will guide the design of optimal compounds. This is also why advances in chemoproteomics [

20] and biophysics [

21] are so crucial.

Objection: How does affinity apply to drugs with long residency times?

The binding of covalent compounds depend on molecular recognition to form the necessary reaction intermediates on a reasonable time scale. Further, the binding of slow off-rate reversible inhibitors generally involves protein conformational changes which depend on favorable intermolecular interactions between drug and protein.

Objection: How does affinity apply to agonists?

Objection: Late stage, idiosyncratic tox can arise for many reasons, none of which can currently be predicted. How do you address this?

While relatively rare, this is indeed a serious medical issue. Understanding the underlying mechanisms driving such events, and learning how to avoid them, is a challenging problem that is likely to continue to plague the field for several decades.

Indirectly, a deeper understanding of affinity enables the generation of multiple diverse chemotypes which are unlikely to suffer from the same idiosyncratic effects. However, since idiosyncratic toxicity may not appear until late in clinical trials, the availability of multiple chemotypes at the research stage may not offer immediate relief. What will have a far greater impact will be the ability to identify the potential for idiosyncratic toxicology at the preclinical stage, assisted by a deeper understanding of the avoid-ome and the ability to predict the range of possible human metabolites with greater accuracy.

Objection: How does this help me with biologics?

Potency and selectivity are equally relevant to the design of biologics.

For biologic drugs that form multimeric complexes (ADCs, bispecifics, and the like) understanding the intermolecular interactions will be equally challenging – and equally important – as in small molecule proximity enhancing medicines.

The incorporation of non-standard amino acids and post-translational modifications (sugars, phosphates, sumoyl groups, and so forth) holds the potential to greatly increase the utility of many biologic agents. However, the intermolecular interactions of these non-standard moieties with macromolecular targets will need to be extensively studied so that we may understand their potency.

Objection: Most of my targets these days are very highly complex molecular machines where obtaining relevant structural insight is still quite challenging.

Many targets remain “undruggable” because we lack a useful chemical starting point. If a target is “un-screenable” (meaning no suitable screen can be devised and executed) or “un-ligandable” (meaning a screen is possible but fails to produce useful chemical matter), that target is de facto “undruggable.”

Even in cases with chemical matter, discerning the structure-function relationships of complex intracellular multi-component machines will remain daunting for some time.

In cases without information about the target structure(s), we can view them as comparable to phenotypic programs, for which structural insights into avoid-ome targets should assist with compound optimization by preventing ADME and tox challenges.

Finally, as the field of structural biology continues to mature, and as we further improve our ability to predict structures in silico, these complex multi-component systems will become tractable.

Discussion

An increased emphasis on affinity provides significant benefits for drug discovery in the seven distinct ways described above: Achieving multiple potent early tool compounds more quickly; making compounds with increased potency; making more selective compounds; optimizing drug candidates more quickly; pursuing more synthetically challenging compounds; expanding chemical diversity during lead optimization; and making better drugs by evading the avoid-ome: the many targets responsible for ADME and tox challenges. These benefits will occur to differing degrees at different stages of different projects.

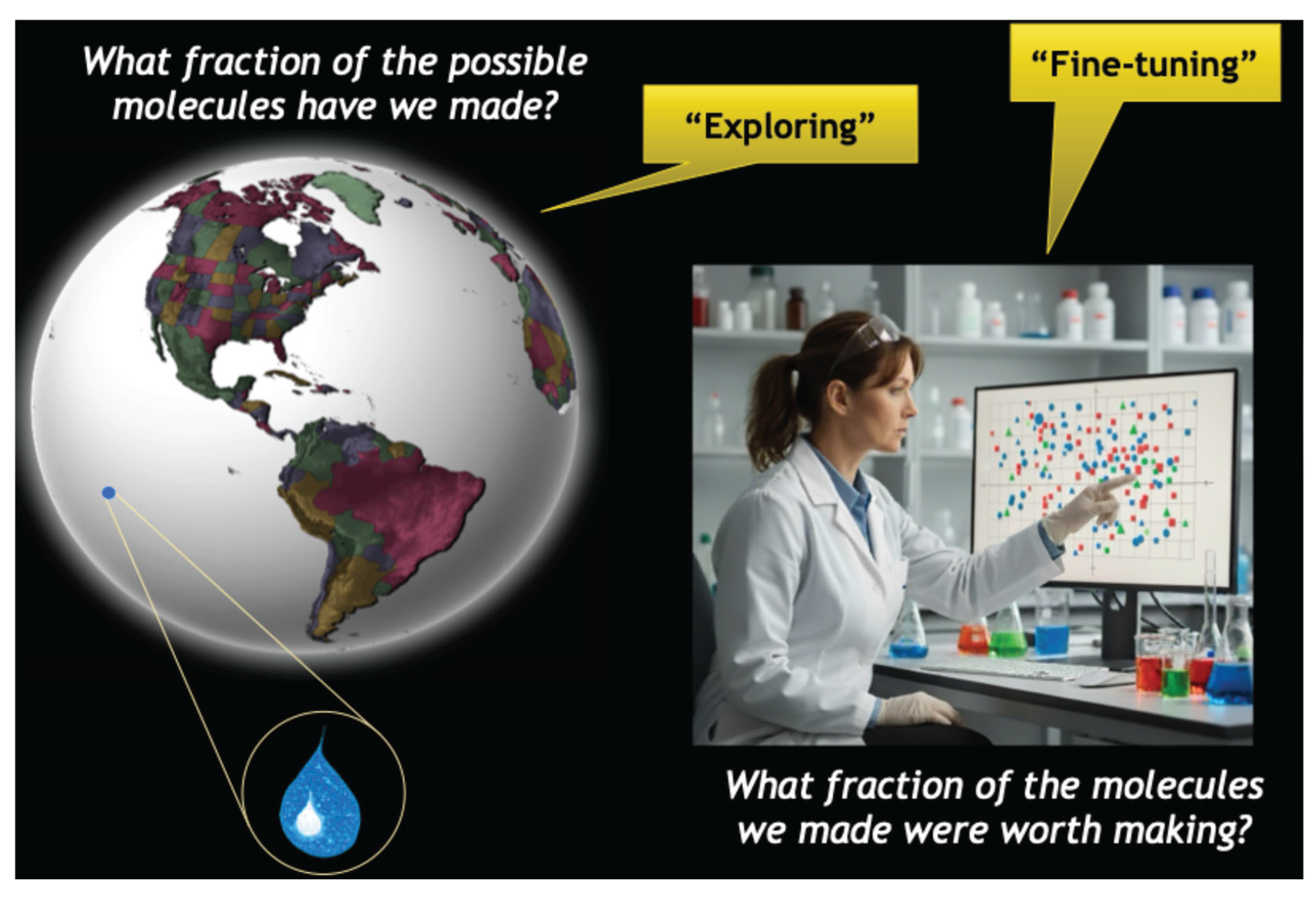

To clarify the varied ways in which these seven benefits will be realized, consider how the chemical strategy of any discovery team may be described as a mix of

exploring and

fine-tuning. [

Figure 2].

Exploring refers to sampling chemical space broadly. The operative questions are, “How much of chemical space have I explored?” and “How can I prioritize my exploration?” However, in the history of medicinal chemistry we have collectively sampled only a tiny fraction of the potential “drug space” – literally less than “a drop in the ocean.” Project teams often struggle to find multiple distinct lead series and have limited insights into how best to carry out a broader search of chemical space. Fortunately, our community appears to have overcome the destructive mindset that considered only a narrow spectrum of molecules to be “drug-like” based on arbitrarily defined “rules.” Teams are more adventurous now, and a deeper understanding of affinity helps to guide exploration.

Fine-tuning refers to our ability to make more subtle changes to optimize the properties within a lead series. The relevant question while fine-tuning is, “What fraction of the molecules I’m making are good choices?” When we choose to make specific analogs within a given series, we are attempting to optimize multiple parameters simultaneously. We must admit that we are not very effective at fine-tuning. Many project teams never produce a drug candidate, and the teams that do succeed generally make thousands of compounds during a multi-year process to select one “winner.” A deeper understanding of affinity can dramatically improve the overall efficiency of the search process.

Broadly speaking, project teams tend to explore in earlier stages and fine-tune during lead optimization. However, each of the seven affinity benefits enable both exploring and fine-tuning in diverse ways, depending on the bespoke challenges of that project. In the exploration phase, a dramatically improved chemotype may be discovered that would have otherwise been missed. In the fine-tuning stage, a more subtle understanding of affinity may enable the refinement of molecular properties within an existing series or provide impetus to pursue synthetically challenging molecules.

Understanding affinity can be challenging, especially when dealing with complex targets and novel drug modalities. Continued advances in both experimental [

20,

21] and computational [

22] methods will help us navigate such situations.

It should be obvious that it would be foolish either to pursue

poor chemical series with high affinity or to focus

solely on affinity. Rather, my point is that chemists often

stop trying to improve affinity once nanomolar levels have been achieved. While such levels are often sufficient, additional affinity may dramatically simplify the multi-parameter optimization process, especially for challenging targets. PK challenges simply become more manageable if less circulating drug is needed at the site of action to achieve the desired effect [

23]. Lower total body dose compounds also tend to be safer.

For these reasons, I am suggesting that throughout the duration of a research project, the pursuit of further intrinsic affinity gains is a sound strategy. Improved affinity,

if not offset by setbacks in ADME parameters, will generally lead to better outcomes. For this reason, rubrics such as LipE [

24] and VLE [

25] are useful

in practice, as is careful attention to half-life [

26].

I also do not wish to minimize the importance of addressing the many other challenges that plague drug discovery. In this Perspective I have already mentioned such topics as: idiosyncratic tox; the ability to run a suitable screen to identify viable chemical starting points; and the complex behaviors of proximity enhancing drugs. Some other challenges include: the effects of residency time on drug action; the subtleties of receptor pharmacology (biased signaling, partial and inverse agonism, and so forth); discerning the structure-function relationships in complex, dynamic, multi-component intracellular machines; and biological target validation. An understanding of ligand-target affinity will only partially address each of these challenges.

While not the whole story, affinity matters greatly – and often more than we realize. The path forward is clear. A greater emphasis on the optimization of affinity provides clear, diverse, and significant benefits and will accelerate the creation of revolutionary medicines.

References

- Hirschmann, R. Medicinal Chemistry in the Golden Age of Biology: Lessons from Steroid and Peptide Research. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 30, 1278–1301 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Murcko, M. A. What Makes a Great Medicinal Chemist? A Personal Perspective. J Med Chem 61, 7419–7424 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Brunton, L. L. . & Knollmann, B. C. . Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. (McGraw Hill, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vargason, A. M., Anselmo, A. C. & Mitragotri, S. The evolution of commercial drug delivery technologies. Nat Biomed Eng 5, 951–967 (2021).

- Johns, D. G. et al. Orally Bioavailable Macrocyclic Peptide That Inhibits Binding of PCSK9 to the Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor. Circulation 148, 144–158 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Fourie, A. M. et al. JNJ-77242113, a highly potent, selective peptide targeting the IL-23 receptor, provides robust IL-23 pathway inhibition upon oral dosing in rats and humans. Sci Rep 14, 17515 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Varkaris, A. et al. Discovery and Clinical Proof-of-Concept of RLY-2608, a First-in-Class Mutant-Selective Allosteric PI3Kα Inhibitor That Decouples Antitumor Activity from Hyperinsulinemia. Cancer Discov 14, 240–257 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ryszkiewicz, P., Malinowska, B. & Schlicker, E. Polypharmacology: new drugs in 2023–2024. Pharmacological Reports 77, 543–560 (2025).

- Aebersold, R. et al. How many human proteoforms are there? Nat Chem Biol 14, 206–214 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P. de S. M., Franco, L. S. & Fraga, C. A. M. The Magic Methyl and Its Tricks in Drug Discovery and Development. Pharmaceuticals 16, 1157 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gillis, E. P., Eastman, K. J., Hill, M. D., Donnelly, D. J. & Meanwell, N. A. Applications of Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry. J Med Chem 58, 8315–8359 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Baran, P. S. Natural Product Total Synthesis: As Exciting as Ever and Here To Stay. J Am Chem Soc 140, 4751–4755 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Gaich, T. & Baran, P. S. Aiming for the Ideal Synthesis. J Org Chem 75, 4657–4673 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Couto, N. et al. Quantification of Proteins Involved in Drug Metabolism and Disposition in the Human Liver Using Label-Free Global Proteomics. Mol Pharm 16, 632–647 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J. S. & Murcko, M. A. Structure is beauty, but not always truth. Cell 187, 517–520 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Beckers, M., Fechner, N. & Stiefl, N. 25 Years of Small-Molecule Optimization at Novartis: A Retrospective Analysis of Chemical Series Evolution. J Chem Inf Model 62, 6002–6021 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Deshaies, R. J. Multispecific drugs herald a new era of biopharmaceutical innovation. Nature 580, 329–338 (2020).

- Douglass, E. F., Miller, C. J., Sparer, G., Shapiro, H. & Spiegel, D. A. A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for Three-Body Binding Equilibria. J Am Chem Soc 135, 6092–6099 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Riching, K. M., Caine, E. A., Urh, M. & Daniels, D. L. The importance of cellular degradation kinetics for understanding mechanisms in targeted protein degradation. Chem Soc Rev 51, 6210–6221 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Niphakis, M. J. & Cravatt, B. F. Ligand discovery by activity-based protein profiling. Cell Chem Biol 31, 1636–1651 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Garbagnoli, M. et al. Biophysical Assays for Investigating Modulators of Macromolecular Complexes: An Overview. ACS Omega 9, 17691–17705 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ross, G. A. et al. The maximal and current accuracy of rigorous protein-ligand binding free energy calculations. Commun Chem 6, 222 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. R. et al. Integrating the Impact of Lipophilicity on Potency and Pharmacokinetic Parameters Enables the Use of Diverse Chemical Space during Small Molecule Drug Optimization. J Med Chem 63, 12156–12170 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Leeson, P. D. & Springthorpe, B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6, 881–890 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Roecker, A. J. et al. Pyrazole Ureas as Low Dose, CNS Penetrant Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. ACS Med Chem Lett 14, 146–155 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin, H. et al. Strategy for Extending Half-life in Drug Design and Its Significance. ACS Med Chem Lett 9, 528–533 (2018). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).