Introduction

Severe inherited diseases represent a significant health challenge. In particular, despite representing a fraction of the total genetic disease burden, about 7,000 distinct rare monogenic diseases affect more than 300-400 million people worldwide and 30 million people in the United States alone[

1]. Yet, only about 5% of these conditions have an FDA-approved treatment[

2].

Moreover, the development of somatic gene therapies, which aim to treat the disease in an existing patient, has encountered significant and persistent safety hurdles. Recent high-profile setbacks in 2025, such as the FDA placing a clinical hold on Sarepta Therapeutics' Elevidys program following patient deaths from acute liver failure, and Intellia Therapeutics pausing its Phase 3 CRISPR trial due to a serious liver-related adverse event, highlight the profound risks associated with post-natal intervention. This reality leaves prevention as the most effective strategy for mitigating the devastating consequences of these disorders.

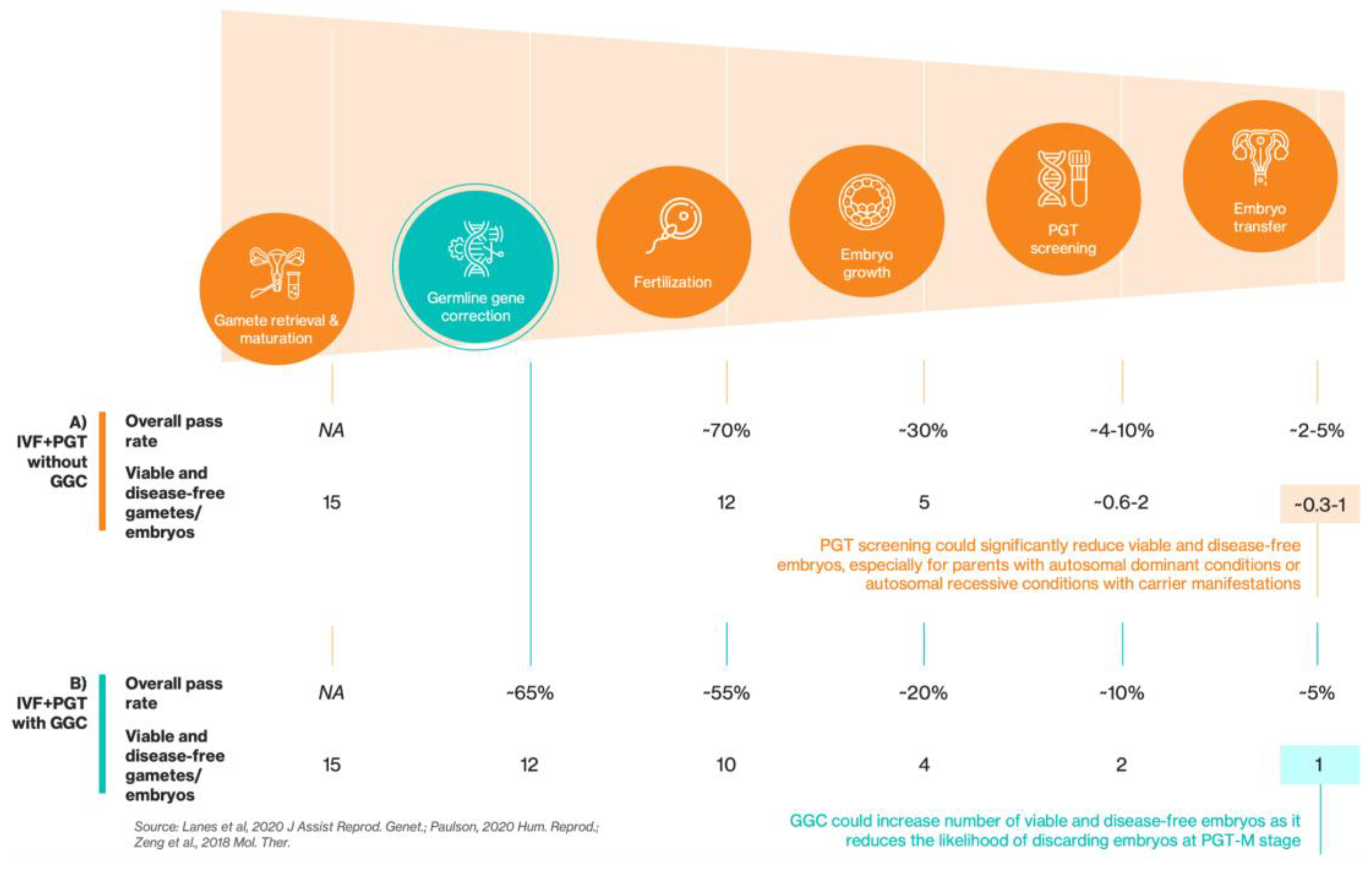

For decades, the primary tool for preventing genetic diseases pre-birth has been preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), the only tool used alongside

in vitro fertilization (IVF) to allow for the selection of embryos free of a disease-causing mutation before implantation[

3]. However, as a technology of selection, its success depends entirely on the availability of a sufficient number of disease-allele-free, high-quality embryos. This limitation is particularly acute for autosomal dominant conditions, for couples with limited ovarian reserve and in cases of maternally-inherited mitochondrial diseases where all embryos will be affected.

Pre-birth gene correction, also known as germline gene correction (GGC), is an experimental approach that contrasts with current embryonic selection strategies used in reproductive medicine by directly repairing the genome of an embryo carrying a pathogenic mutation. This process employs genome-editing tools, such as the CRISPR-Cas9 system[

4] and its higher-precision derivatives[

5,

6], to repair the pathogenic DNA sequence.

As shown in

Figure 1A, the journey from oocyte retrieval to embryo transfer is a biological gauntlet, especially for patients with monogenic diseases. The steep attrition rate at every stage of IVF means that ~80% of initial oocytes do not result in a viable embryo[

7]. This inherent inefficiency is compounded by the unyielding probabilities of Mendelian genetics. For fully penetrant autosomal dominant conditions, 50% of embryos will be affected. In cases of autosomal recessive inheritance where the heterozygous state is not asymptomatic (i.e., ‘carrier manifestations’ exist), such as in Alport syndrome (COL4A3 and COL4A4)[

8] and phenylketonuria (PKU)[

9], even when just one parent is a carrier, 50% of embryos will inherit the pathogenic allele and thus be at risk for these carrier-associated symptoms. For other recessive monogenic conditions where both parents are carriers, 25% will be affected. When combined with the baseline rate of aneuploidy of ~50%, which increases dramatically with maternal age[

10], the final number of euploid, viable and genetic disease-free embryos available for transfer can easily drop to <1 embryo per IVF cycle (assuming occurrence of aneuploidy is independent of disease gene inheritance pattern and that euploid embryos are preferred), despite starting with the retrieval of 18 oocytes, which is the maximum amount recommended for an optimal live birth rate[

11]. This reality forces many (especially older) couples into multiple physically demanding and emotionally draining IVF cycles with a low overall live birth rate per cycle[

12].

GGC could fundamentally improve the IVF journey by making healthy embryos available for implantation where none may have existed before (

Figure 1B). By directly repairing the disease-causing mutation, GGC can transform an affected embryo into an unaffected one, preventing it from being discarded. This increases the number of viable, disease-allele-free embryos, making a successful transfer more likely. If integrated into existing in vitro fertilization (IVF) and PGT workflows, GGC would represent a mechanism for genetic correction rather than embryonic selection.

Results

To assess the potential of GGC, we estimated the number of disease-affected embryos that could be corrected for four severe monogenic diseases: sickle cell disease, cystic fibrosis, Marfan syndrome, and Huntington’s disease. Our analysis (

Table 1) establishes a sliding range of impact by modeling two scenarios: 1)

A conservative floor, which would consider the number of at-risk couples who currently have access to and utilize technologies like IVF and PGT. This provides a baseline for the immediate, real-world impact if GGC were introduced today, and 2)

A potential ceiling, which models the full potential of an integrated IVF-GGC-PGT pathway by assuming broad, equitable, and affordable access for all at-risk couples. Achieving this vision is a long-term goal that would require overcoming significant current barriers, such as the high cost of IVF and the lack of healthcare infrastructure in many regions in the United States. This expansion would be driven by major investments in public health, supportive regulatory policies, and transparent public engagement to foster trust and acceptance of this technology.

Sickle cell disease (SCD), one of the most common severe genetic diseases globally, is inherited in a recessive manner. The underlying genetic cause for the majority of SCD cases is a missense mutation (p.Glu6Val, c.20A>T) in the Hemoglobin Subunit Beta (

HBB) gene, leading to the production of an abnormal hemoglobin, known as hemoglobin S (HbS). Under low-oxygen conditions, HbS polymerizes, causing red blood cells to deform into their characteristic rigid, sickle shape[

13]. From a technical standpoint, correcting the canonical HBB p.Glu6Val (c.20A>T) mutation presents a clear target. This specific A-to-T transversion is now correctable using recently developed T-to-A base editors[

14], providing a direct repair strategy.

Carrier frequency of SCD is high in many populations: E.g., up to 1 in 4 in parts of Africa like the northeastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo[

15] and up to 1 in 3 in parts of India like the Nilgiris region[

16]. This results in a large number of affected births. Indeed, recent data indicate about 515,000 babies are born with SCD every year worldwide[

17]. In the United States, SCD occurs in about 1 out of every 365 African American births[

18]. The carrier status, known as sickle cell trait, is present in approximately 1 in 13 African American babies, highlighting a significant at-risk population within the country[

18].

Our analysis, in a conservative floor estimate, suggests that GGC could correct approximately ~35 embryos each year that would otherwise be discarded, providing a tangible, immediate benefit for families already pursuing assisted reproductive technologies. In the potential ceiling scenario, GGC could correct an estimated ~855-1,140 embryos annually, a figure corresponding to the prevention of nearly every new case of SCD in the US each year.

Given the high prevalence of SCD in other parts of the globe, the US figures represent only a fraction of GGC’s true potential. With approximately 515K babies born with SCD worldwide each year, the global “potential ceiling” for GGC is immense. Extrapolating from our model, a universally accessible IVF-GGC-PGT pathway could theoretically correct hundreds of thousands of embryos annually, offering a preventative solution for many nations facing high SCD prevalence.

Translating this theoretical potential into reality faces significant challenges. The regions with the highest prevalence of SCD often have the least access to the advanced reproductive technologies required for this intervention[

19]. Realizing the global promise of GGC would necessitate overcoming significant barriers, including the lack of healthcare infrastructure, the absence of comprehensive newborn or carrier screening programs to identify at-risk couples, and the high cost and limited availability of IVF itself. Therefore, while GGC presents a powerful technical solution, its equitable global deployment remains a long-term goal dependent on major investments in public health and infrastructure.

Beyond SCD, several other severe genetic conditions highlight the breadth of impact that GGC could achieve. Cystic fibrosis (CF), for example, is one of the most common lethal recessive disorders that causes thick, sticky mucus to build up in the lungs, pancreas, and other organs, leading to breathing and digestive problems[

20]. Technical feasibility for CF primarily centers on correcting the most common pathogenic variant, a 3-bp deletion known as F508del in the

CFTR gene[

20]. This type of indel mutation is not amenable to standard base editing. Instead, it requires more complex approaches like prime editing or homology-directed repair (HDR) to precisely re-insert the missing codon. Proof-of-concept studies in patient-derived airway epithelial cells has shown that correction is possible with an optimized prime editing strategy[

21]. Our conservative floor estimate suggests ~25 affected embryos could be corrected each year. The potential ceiling is far greater, with the possibility of rescuing ~540-720 embryos annually and transforming the outlook for at-risk families.

Huntington’s disease is a fatal autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder that causes progressive loss of movement, cognition, and psychiatric stability[

22]. The genetic target in Huntington’s disease, an expanded CAG trinucleotide repeat in the

HTT gene, presents a unique technical challenge. Unlike single-nucleotide variants, the therapeutic goal is to contract the repeat sequence to a non-pathogenic length (<36 repeats)[

22]. A recent and promising strategy uses base editing to reduce the repetitiveness of the repeat without excising it by introducing interruptions into the CAG repeat sequences and mimicking stable, non-pathogenic alleles that naturally occur in the population[

23]. Our analysis estimates a conservative application of GGC within the current IVF-using population could correct approximately ~10 embryos each year. In an ideal scenario with broad access, the potential ceiling for impact rises to ~280-375 corrected embryos annually in the US. While the number of embryos corrected is higher than the number of live births with Huntington’s disease, these HD-free embryos could substantially enhance the chances of disease-free live birth per IVF cycle for at-risk couples, thereby reducing the need for at-risk couples to go through multiple IVF cycles.

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition affecting connective tissue[

24] and is caused by a wide range of mutations in the

FBN1 gene, many of which are point mutations well-suited for gene correction. The technical plausibility of this approach has been demonstrated directly in human embryos. For instance, a pathogenic missense mutation (c.605G>A) was successfully corrected using a cytidine base editor[

25]. The immediate impact of GGC is a conservative floor of ~35 corrected embryos annually for families already using IVF. The potential ceiling, assuming widespread adoption, is an estimated ~865-1,150 corrected embryos per year.

Discussion

Taken together, these conditions demonstrate the benefit of integrating GGC with IVF and PGT. This new approach fundamentally shifts the paradigm from selection to correction. This reframing has both clinical and ethical implications, recasting embryo intervention as therapeutic rather than enhancement-based. For families at risk, the path forward transcends the uncertainty of conceiving a healthy embryo. Instead, GGC acts as a crucial rescue mechanism and increases the number of embryos that are negative for the disease genotype, potentially improving the probability of transfer and live birth of a disease-free newborn.

While the quantitative estimates outlined above illustrate GGC’s transformative potential, their realization depends on establishing rigorous safety validation and thoughtful ethical governance. Translating a germline intervention from theoretical modeling to clinical practice demands standards of precision, oversight, and societal accountability exceeding those applied to most other biomedical innovations. The promise of expanded reproductive autonomy should therefore be pursued in parallel with transparent public engagement, regulatory clarity, and continued research into the long-term effects of germline modification. These considerations define the framework within which GGC can progress responsibly from scientific feasibility to clinical reality.

The clinical rationale for GGC should be accompanied by a systematic evaluation of its biological risks, governance requirements, and societal implications. Moving from preclinical feasibility to potential clinical applications requires not only technological refinement but also a robust ethical framework that ensures transparency, accountability, and access.

A central consideration is the management of biological and technical risks. Despite promising preclinical data, responsible clinical translation requires addressing key biological risks, including: 1) Off-target effects: Unintended cleavage of DNA at sites similar to the target sequence. This risk is being progressively mitigated by the development of high-fidelity editors and sophisticated computational prediction tools. Large, unintended genetic alterations at or near the target site could occur, including deletions, rearrangements, or even chromosome loss. This risk is being mitigated by the development of new generation editors to reduce large deletions and translocations; and 2) On-target efficiency / Mosaicism: An embryo containing a mixture of edited, unedited, and incorrectly edited cells, which undermines the therapeutic goal. This risk could be mitigated by controlling the timing of gene editing to target oocytes before fertilization, optimizing delivery formats and editing reagents, and enhancing precise repair mechanisms during editing.

These critical risks provide an essential roadmap for the next phase of research[

26]. The immediate goal is to enhance GGC techniques and develop comprehensive analytical methods to generate the robust safety and efficacy data required to evaluate any potential clinical application. Governance will need to evolve in parallel with technical progress. Oversight mechanisms should include harmonized international standards for preclinical validation, independent registries for reporting all embryo-editing studies, and transparent data-sharing to facilitate reproducibility and public trust. Clear regulatory criteria will be required to define when a germline intervention moves from exploratory research to a clinically eligible protocol.

Some inherent limitations of this modeling study exist, which necessarily relies on imperfect data and simplifying assumptions. For one, the use of age-adjusted diagnostic frequency as a substitute for true birth incidence is a notable limitation, especially for conditions with delayed or variable onset, such as Huntington's disease. This metric captures the number of individuals diagnosed in a given year, not the number of infants born with the pathogenic variant. It is therefore confounded by several factors, including the natural history of the disease (i.e., the typical age of onset), changes in diagnostic awareness and criteria over time, and the mortality rate among carriers who may die from unrelated causes before a diagnosis is ever made. This creates a potential discrepancy between the annual number of new diagnoses and the actual number of newborns who carry the genetic mutation. Future research could refine these estimates by moving beyond diagnostic proxies. Furthermore, the expansion of newborn sequencing programs to include the genetic markers for these conditions would eventually provide direct, real-world data, eliminating the need for such estimations entirely.

Another limitation is the application of a single, nationwide 2.6% IVF utilization rate across all conditions to establish the conservative floor estimate. This approach assumes uniform access to and use of assisted reproductive technologies, which does not reflect the complex realities of the US healthcare landscape. In practice, IVF utilization varies significantly based on socioeconomic status, geographic location, state-level insurance mandates for fertility treatment, and racial or ethnic background. Consequently, our conservative floor may not accurately capture the real-world potential of GGC for specific disease populations whose access to IVF may be higher or lower than the national average. Future models should incorporate stratified IVF utilization data that accounts for the specific demographic and socioeconomic profiles of the patient populations for each disease. This would allow for a more precise estimation of the conservative floor by aligning IVF access rates with the populations most at risk.

In addition, this conservative floor model assumes that all at-risk couples within this group would be candidates for GGC, but it does not account for the specific adoption rate of PGT-M (PGT for monogenic disorders). There is a lack of comprehensive data on what percentage of couples, who are already using IVF and are known carriers for a severe genetic disease, proceed with PGT-M. This decision can be influenced by additional costs, provider awareness, genetic counseling, and patient preference. Therefore, the "conservative floor" calculation could be improved with more granular data on PGT-M adoption rates for specific disease populations. This would provide a more precise baseline of the immediate patient group that would be candidates for an integrated IVF-GGC-PGT pathway.

Furthermore, this study’s “potential ceiling” estimates rely on an efficacy benchmark of 60-80% for GGC, derived from two preclinical studies. This simplification, necessitated by the early stage of GGC technology and the limited availability of comprehensive efficacy data, is a limitation because GGC efficiency is not a fixed value; it can vary depending on the specific gene target, the type of mutation being corrected, and the editing technology employed (e.g., base vs. prime editors). As more preclinical studies become available, further modeling could create more robust projections by incorporating a wider range of efficacy rates from this expanded dataset.

In conclusion, pre-birth gene correction, also known as germline gene correction (GGC), offers a transformative alternative to IVF+PGT alone for preventing severe genetic diseases. By directly repairing the underlying mutation, it moves beyond the probabilistic limitations of embryo selection that leave many families without a viable path to parenthood. While PGT has provided an invaluable foundation, GGC unlocks new possibilities by expanding the pool of viable, disease-free embryos. Estimation across high-burden conditions such as sickle cell disease, Marfan syndrome, Huntington’s disease, and cystic fibrosis highlights this potential. In the US alone and for just these four diseases, this technology could correct hundreds to thousands of embryos each year that would otherwise carry these severe conditions, offering families a tangible hope for a healthy child.

While the path to clinical translation should be guided by rigorous safety evaluation and robust ethical governance, the scientific trajectory is increasingly clear. Off-target effects and mosaicism are being addressed through successive generations of precision editing tools, and frameworks for responsible regulation are taking shape. In this context, GGC should not be viewed merely as an experimental possibility but as a profound opportunity to expand reproductive autonomy and prevent avoidable suffering, provided that ongoing research continues to demonstrate reproducible precision and safety. If responsibly developed and equitably deployed, the integrative IVF-GGC-PGT could reshape reproductive medicine, offering hope to families for whom current options remain insufficient.

Materials & Methods

Model Overview and Key Assumptions

The estimations presented in

Table 1 were derived from a model designed to quantify the potential annual impact of GGC in the United States for four severe monogenic diseases: sickle cell disease (SCD), cystic fibrosis (CF), Marfan syndrome (MFS) and Huntington’s disease (HD). The model calculates the number of embryos that could be corrected from a disease-causing genotype to a healthy one, under two distinct scenarios: 1)

Conservative floor: This scenario estimates the immediate impact of GGC if it were made available to the current population of at-risk couples who already utilize IVF and PGT. It is based on the current IVF usage rate in the US; and 2)

Potential ceiling: This scenario models an idealized future where an integrated IVF-GGC-PGT pathway is affordable and accessible to all at-risk couples in the US, assuming a high GGC efficacy rate.

The model relies on several key parameters derived from publicly available data and established clinical literature as cited, including US birth statistics, disease diagnostic frequency, IVF utilization rates, and standard IVF attrition rates. All numerical estimates are intended for illustrative purposes and are not clinical projections.

Calculation of Annual Births with Condition

The total number of annual births affected by each condition in the United States was estimated.

For SCD, the calculation was stratified by ethnicity due to varying incidence. Based on 3.6 million annual US live births, we estimated the number of African American births (3.6M × 13.9% = 500,400) and Hispanic births (3.6M × 25.3% = 910,800)[

27]. Using the respective incidence rates of 1 in 365 for African Americans and 1 in 16,300 for Hispanics[

18], the total estimated annual births with SCD is approximately 1,425 (500,400/365 + 910,800/16,300 ≈ 1,425).

For CF, the number of affected births was estimated using an incidence of 1 in 4,000 newborns (via newborn screening)[

20] applied to the total annual live births (3.6M / 4,000 ≈ 900).

For MFS, the number of affected births was estimated using the occurrence of 1 in 5,000 live births [

24] applied to the total annual live births (3.6M / 5,000 ≈ 720).

For HD, the number of affected births was estimated using an annual age-adjusted diagnostic frequency of 6.5 per 100,000 persons in the US[

28] applied to the total annual live births (3.6M × 6.5 / 100,000 ≈ 235). Because HD is not routinely screened in newborns, age-adjusted diagnostic frequency is one proxy available for measure of frequency of birth incidence.

Scenario 1: Conservative Floor (Current Access)

The conservative floor estimate for corrected embryos was calculated using a multi-step process reflecting current clinical realities. First, the total annual births for each condition was multiplied by the average US IVF utilization rate of 2.6%[

29] to determine the number of births to couples already using assisted reproductive technology. Second, we assumed that each IVF-assisted birth resulted from one successful IVF cycle that began with the retrieval of approximately 18 oocytes, which is the maximum number recommended for optimal live birth rate[

11]. After fertilization, the number of genetically affected embryos was then calculated based on Mendelian inheritance patterns for each disease: For SCD and CF, 25% of embryos were assumed to carry the disease-causing allele; For MFS and HD, 50% of embryos were assumed to carry the disease-causing allele. Third, the number of affected embryos was multiplied by the viable embryo development rate, which is estimated to be 20% (reflecting an 80% embryo attrition rate from oocyte retrieval to viable embryo)[

7]. For autosomal recessive conditions (SCD, CF), this factor is approximately 1 (18 oocytes × 20% embryo viability × 25% affected ≈ 0.9, rounded to 1). For autosomal dominant conditions (MFS, HD), this factor is approximately 2 (18 oocytes × 20% viability × 50% affected ≈ 1.8, rounded to 2).

For example, the calculation for Huntington's disease is as follows: For each IVF-assisted birth, assuming 1 IVF cycle/birth, 18 oocytes/cycle and 20% of oocytes result in viable embryos, 18 × 20% ≈ 4 embryos are available. Of these, 50% embryos are affected by HD, 4 × 50% = 2 are HD-affected embryos. Assuming all these embryos are corrected by GGC, 2 embryos would have been corrected by GGC per birth. Given 235 annual births with HD × 2.6% IVF usage rate ≈ 5 IVF-assisted births, total embryos corrected would be 5 × 2 ≈ 10 embryos.

Scenario 2: Potential Ceiling

The potential ceiling scenario assumes universal access to a highly effective IVF-GGC-PGT pathway for all at-risk couples. This estimate was calculated by multiplying the total number of annual births with each condition by an "embryos corrected per birth" factor. The total corrected embryos are therefore the total annual births multiplied by this factor (e.g., for SCD: 1,425 births × ~1 corrected embryo/birth ≈ 1,425, which was then adjusted to ~855-1,140 to reflect an assumed 60-80%+ efficacy rate of the GGC technology itself according to recent studies[

25,

30]).

Data availability statement

Declaration of interest

DK, CT, and EH are employees of Manhattan Genomics, Inc. JRQ is a scientific contributor to Manhattan Genomics, Inc.

Footnotes:

a. In the USA, the newborn rate for sickle cell diseases (SCD) is about 1 in 365 African American births and about 1 in 16,300 Hispanic births[

18]. There were 3.6M live births in the US in 2023, of which 25.3% were Hispanic (0.91M) and 13.9% were African American (0.50M)[

27]. For African American births, ~1,425 of them are estimated to have SCD; for Hispanic births, ~56 of them are estimated to have SCD.

b. Using the 2.6% average IVF usage rate in the USA[

29], it is estimated that ~36 births with SCD were assisted by IVF. Assuming each birth was the result of 1 IVF cycle during which 18 oocytes were extracted. 25% of oocytes carry disease mutations for SCD and GGC was successful, ~4.5 oocytes would have been corrected. Given the approximately 80% attrition rate from oocyte retrieval to development of viable blastocysts, about 1 embryo per IVF cycle would have been SCD-free because the oocyte was corrected by GGC. In sum, a total of ~35 embryos would have been corrected per year in the US.

c. Assuming IVF-GGC-PGT pipeline is available to all at-risk couples and GGC is 60-80% effective at creating on-target only changes (as shown in recent study [

25,

30]), the IVF-GGC-PGT pipeline has the potential to prevent SCD in 80% of the ~1,425 births with the condition each year in the US. Given ~1 embryo corrected per birth, the total embryos corrected are ~855-1,140.

d. In the USA, Cystic Fibrosis (CF) affects 1 in every 4,000 newborns (via newborn screening)[

20]. Given the 3.6M live births, ~900 births are expected to have CF.

e. Using the 2.6% average IVF usage rate, it’s estimated that ~25 births were assisted by IVF. Using the same assumptions in b, about 1 embryo would have been corrected by GGC per IVF. Therefore, a total of ~25 embryos would have been corrected.

f. Using the same assumptions in c, given ~1 embryo corrected per birth, the total embryos corrected are ~540-720.

g. Marfan syndrome (MFS) occurs in 1 of 5,000 live births[

24]. Given the 3.6M live births in the US, ~720 births are expected to have Marfan syndrome in the USA.

h. Using the 2.6% average IVF usage rate in the USA, it is estimated that ~19 births with MFS were assisted by IVF. Assuming each birth was the result of 1 IVF cycle during which 18 oocytes were extracted, 50% of oocytes carry disease mutation for MFS and GGC was successful, ~9 oocytes would have been corrected. Given the ~80% IVF attrition rate (from extraction to embryo development), about 2 embryos per IVF cycle would have been MFS-free because the oocyte was corrected by GGC. In sum, a total of ~35 embryos would have been corrected.

i. Using the same assumptions in c, given ~2 embryos corrected per birth and 60-80% GGC success rate, the total embryos corrected are ~865-1,150.

j. In the USA, Huntington’s disease (HD) is diagnosed in 6.5 per 100,000 persons each year[

28]. Because HD is not routinely screened in newborns, age-adjusted diagnostic frequency is a proxy available for measure of frequency of birth incidence. See limitation of this approach in the “Study limitation” section. Given the 3.6M live births in the US, ~235 births are expected to have HD.

k. Using the 2.6% average IVF usage rate, it’s estimated that ~6 births with HD were assisted by IVF. Using the same assumptions in h, about 2 embryos per IVF cycle would have been HD-free because the oocyte was corrected by GGC. In sum, a total of ~10 embryos would have been corrected per year in the US.

l. Using the same assumptions in c, given ~2 embryos corrected per birth and 60-80% GGC success rate, the total embryos corrected are ~280-375. While the number of embryos corrected is higher than the number of live births with Huntington’s disease, these disease-allele-free embryos could substantially enhance the chances of disease-free live birth per IVF cycle for at-risk couples.

References

- Marwaha, S., Knowles, J.W., and Ashley, E.A. (2022). A guide for the diagnosis of rare and undiagnosed disease: beyond the exome. Genome Med. 14, 23. [CrossRef]

- Fermaglich, L.J., and Miller, K.L. (2023). A comprehensive study of the rare diseases and conditions targeted by orphan drug designations and approvals over the forty years of the Orphan Drug Act. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 18, 163. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K. (2021). Pre-implantation genetic testing: Past, present, future. Reprod. Med. Biol. 20, 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Ran, F.A., Hsu, P.D., Wright, J., Agarwala, V., Scott, D.A., and Zhang, F. (2013). Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308.

- Gaudelli, N.M., Komor, A.C., Rees, H.A., Packer, M.S., Badran, A.H., Bryson, D.I., and Liu, D.R. (2017). Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471.

- Anzalone, A.V., Randolph, P.B., Davis, J.R., Sousa, A.A., Koblan, L.W., Levy, J.M., Chen, P.J., Wilson, C., Newby, G.A., Raguram, A., et al. (2019). Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, S., and Patrizio, P. (2017). Embryo wastage rates remain high in assisted reproductive technology (ART): a look at the trends from 2004-2013 in the USA. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 34, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Deltas, C., Savva, I., Voskarides, K., Papazachariou, L., and Pierides, A. (2015). Carriers of autosomal recessive Alport syndrome with thin basement membrane nephropathy presenting as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in later life. Nephron 130, 271–280. [CrossRef]

- Hames, A., Khan, S., Gilliland, C., Goldman, L., Lo, H.W., Magda, K., and Keathley, J. (2023). Carriers of autosomal recessive conditions: are they really “unaffected?” J. Med. Genet. 61, 1–7.

- Paulson, R.J. (2020). Hidden in plain sight: the overstated benefits and underestimated losses of potential implantations associated with advertised PGT-A success rates. Hum. Reprod. 35, 490–493. [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, G., Homburg, R., Jayaprakasan, K., Raperport, C.J., Huirne, J.A.F., Acharya, S., Racich, P., Ahmed, A., Gudi, A., Govind, A., et al. (2023). Correlation of IVF outcomes and number of oocytes retrieved: a UK retrospective longitudinal observational study of 172 341 non-donor cycles. BMJ Open 13, e064711. [CrossRef]

- Gunnala, V., Irani, M., Melnick, A., Rosenwaks, Z., and Spandorfer, S. (2018). One thousand seventy-eight autologous IVF cycles in women 45 years and older: the largest single-center cohort to date. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 35, 435–440. [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.A., and Carlberg, K. (1993). Sickle cell disease. In GeneReviews(®) (University of Washington, Seattle).

- Ye, L., Zhao, D., Li, J., Wang, Y., Li, B., Yang, Y., Hou, X., Wang, H., Wei, Z., Liu, X., et al. (2024). Glycosylase-based base editors for efficient T-to-G and C-to-G editing in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 1538–1547. [CrossRef]

- Agasa, B., Bosunga, K., Opara, A., Tshilumba, K., Dupont, E., Vertongen, F., Cotton, F., and Gulbis, B. (2010). Prevalence of sickle cell disease in a northeastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo: what impact on transfusion policy? Transfus. Med. 20, 62–65. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K., Krishnamurti, L., and Jain, D. (2024). Sickle cell disease in India: the journey and hope for the future. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2024, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Sickle Cell Disease Collaborators (2023). Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 10, e585–e599.

- CDC (2024). Data and Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. Sickle Cell Disease (SCD). https://www.cdc.gov/sickle-cell/data/index.html.

- Chambers, G.M., Dyer, S., Zegers-Hochschild, F., de Mouzon, J., Ishihara, O., Banker, M., Mansour, R., Kupka, M.S., and Adamson, G.D. (2021). International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies world report: assisted reproductive technology, 2014. Hum. Reprod. 36, 2921–2934. [CrossRef]

- Scotet, V., L’Hostis, C., and Férec, C. (2020). The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis: Incidence, survival and impact of the CFTR gene discovery. Genes (Basel) 11, 589. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.A., Hemez, C., Lei, L., Traore, S., Kulhankova, K., Newby, G.A., Doman, J.L., Oye, K., Pandey, S., Karp, P.H., et al. (2025). Systematic optimization of prime editing for the efficient functional correction of CFTR F508del in human airway epithelial cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 9, 7–21. [CrossRef]

- Faquih, T.O., Aziz, N.A., Gardiner, S.L., Li-Gao, R., de Mutsert, R., Milaneschi, Y., Trompet, S., Jukema, J.W., Rosendaal, F.R., van Hylckama Vlieg, A., et al. (2023). Normal range CAG repeat size variations in the HTT gene are associated with an adverse lipoprotein profile partially mediated by body mass index. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 1741–1752. [CrossRef]

- Matuszek, Z., Arbab, M., Kesavan, M., Hsu, A., Roy, J.C.L., Zhao, J., Yu, T., Weisburd, B., Newby, G.A., Doherty, N.J., et al. (2025). Base editing of trinucleotide repeats that cause Huntington’s disease and Friedreich's ataxia reduces somatic repeat expansions in patient cells and in mice. Nat. Genet. 57, 1437–1451. [CrossRef]

- Marfan syndrome and congenital heart conditions (2009). https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/marfan-syndrome-and-congenital-heart-conditions.

- Zeng, Y., Li, J., Li, G., Huang, S., Yu, W., Zhang, Y., Chen, D., Chen, J., Liu, J., and Huang, X. (2018). Correction of the Marfan syndrome pathogenic FBN1 mutation by base editing in human cells and heterozygous embryos. Mol. Ther. 26, 2631–2637. [CrossRef]

- Amato, P., Mikhalchenko, A., and Mitalipov, S. (2025). The case for germline gene correction: state of the science. Fertil. Steril. 124, 22–29. [CrossRef]

- CDC (2025). Births and Natality. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm.

- Bruzelius, E., Scarpa, J., Zhao, Y., Basu, S., Faghmous, J.H., and Baum, A. (2019). Huntington’s disease in the United States: Variation by demographic and socioeconomic factors: HUNTINGTON'S DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES. Mov. Disord. 34, 858–865.

- ASRM (2025). US IVF usage increases in 2023, leads to over 95,000 babies born. American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). https://www.asrm.org/news-and-events/asrm-news/press-releasesbulletins/us-ivf-usage-increases-in-2023-leads-to-over-95000-babies-born/.

- Marti-Gutierrez, N., Liang, D., Chen, T., Lee, Y., Ma, H., Koski, A., Mikhalchenko, A., Heitner, S.B., Kang, E., Amato, P., et al. (2020). Gene conversion in human embryos induced by gene editing. Fertil. Steril. 114, e35. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).