Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Imperative for High-Resolution Climate Projections and the Rise of Machine Learning

1.1. Positioning This Review in the Literature

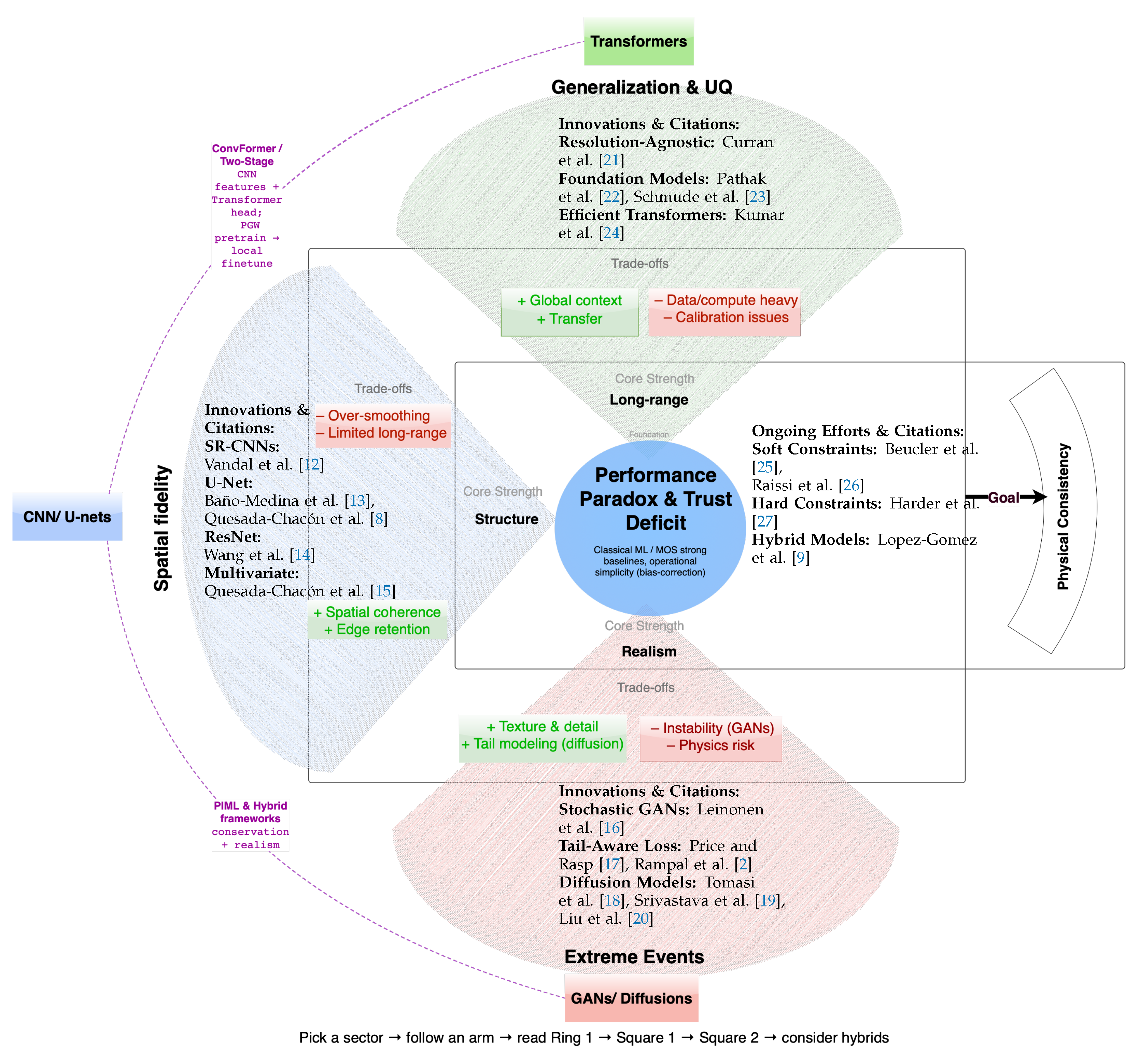

- Creating a novel taxonomy that explicitly maps different classes of ML models—from CNNs and GANs to Transformers and Diffusion Models—to the specific downscaling challenges they are best suited to address.

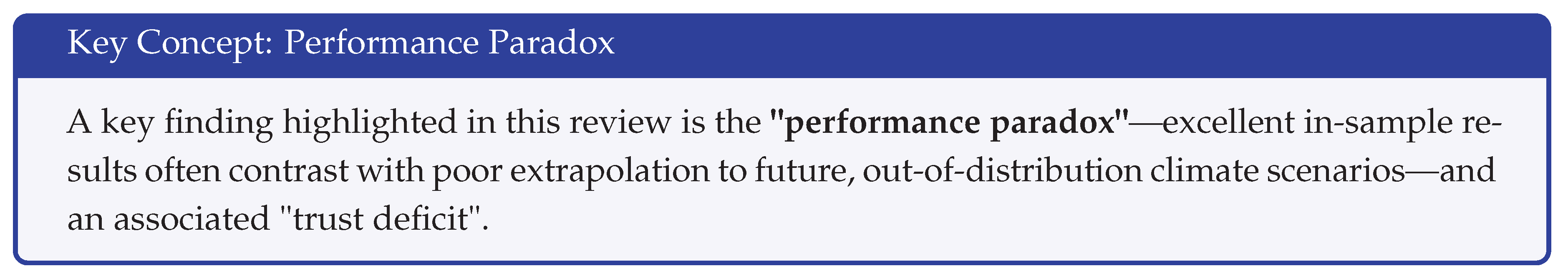

- Conducting a critical analysis of the “performance paradox,” where high statistical skill on historical data often fails to translate to robust performance under the non-stationary conditions of future climate change.

- Proposing a practical evaluation protocol and charting clear, targeted research priorities to guide the community towards developing more physically consistent, trustworthy, and operationally viable models.

1.2. Overview of the Review’s Scope and Objectives

- RQ1: Evolution of Methodologies: How have ML approaches for climate downscaling evolved from classical algorithms to the current deep learning architectures, and what are the primary capabilities and intended applications of each major model class?

- RQ2: Persistent Challenges: What are the critical, cross-cutting challenges that limit the operational reliability of contemporary ML downscaling models, particularly regarding their physical consistency, generalization under non-stationary climate conditions, and overall trustworthiness?

- RQ3: Emerging Solutions and Future Trajectories: What methodological frontiers including physics-informed learning (PIML), robust uncertainty quantification (UQ), and explainable AI (XAI)—hold the most promise for addressing these key challenges and guiding future research?

2. Scope and Approach

3. Background: The Downscaling Problem

3.1. The Scale Gap in Climate Modeling and the Need for Downscaling

3.2. Limitations of Traditional Downscaling Methods

3.2.1. Dynamical Downscaling (DD)

3.2.2. Statistical Downscaling (SD)

3.3. Emergence and Promise of ML in Transforming Statistical Downscaling

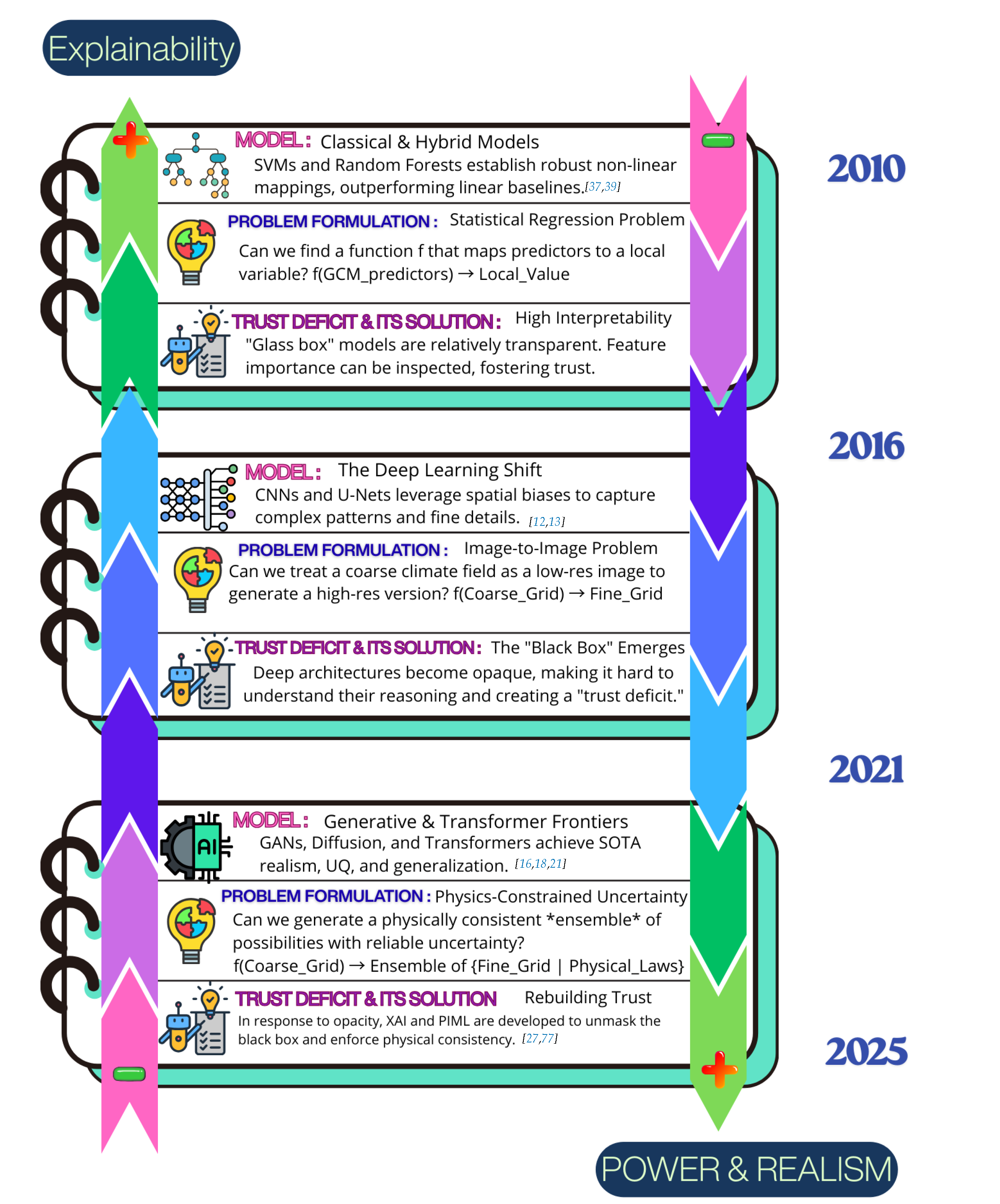

4. The Evolution of Machine Learning Approaches in Climate Downscaling

4.1. Early Applications and Classical ML Benchmarks

4.2. The Deep Learning Paradigm Shift

4.2.1. Pioneering Work with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

4.2.2. Architectural Innovations

U-Nets

Residual Networks (ResNets)

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

- Strengths:

- GANs have shown promise for generating outputs with improved perceptual quality, sharp gradients, and in some cases better representation of fine-scale variability and heavy-tailed statistics compared to models trained solely with pixel-wise losses like Mean Squared Error (MSE) [32]. StyleGAN-family architectures achieve low Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores across large-scale benchmarks, highlighting their strength for perceptually realistic textures [56,57]. Conditional GANs (CGANs), such as MSG-GAN-SD by Accarino et al. [58], demonstrate direct applicability to downscaling by conditioning generation on low-resolution input. While some studies report more realistic precipitation or temperature fields using CGANs [59], consistent advantages in reproducing extremes remain preliminary and context-dependent.

- Limitations:

- GANs are notoriously challenging to train due to issues like mode collapse (where the generator produces limited varieties of samples) and training instability [32]. Evaluating GAN performance can also be difficult, as traditional pixel-wise metrics may not fully capture perceptual quality. Moreover, while GANs can produce visually appealing results, some studies suggest they might not always accurately capture the full statistical distribution of the high-resolution data, which is critical for scientific applications [19]. The extrapolation of GANs for downscaling precipitation extremes in warmer, future climates remains an active area of research and concern. A notable application of GAN-based frameworks is the Super-Resolution for Renewable Energy Resource Data with Climate Change Impacts (Sup3rCC) model developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [60]. Sup3rCC employs a generative machine learning approach, specifically leveraging GANs, to downscale Global Climate Model (GCM) data to produce 4-km hourly resolution fields for variables crucial to the energy sector, such as wind, solar irradiance, temperature, humidity, and pressure, for the contiguous United States under various climate change scenarios. The model learns realistic spatial and temporal attributes by training on NREL’s historical high-resolution datasets (e.g., National Solar Radiation Database, Wind Integration National Dataset Toolkit) and then injects this learned small-scale information into coarse GCM inputs. This methodology is designed to be computationally efficient compared to traditional dynamical downscaling while providing physically realistic high-resolution data tailored for studying climate change impacts on energy systems, renewable energy generation, and electricity demand. It’s important to note that Sup3rCC is designed to represent the historical climate and future climate scenarios, rather than specific historical weather events [60].

Diffusion Models

- Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs): To mitigate the high computational cost of operating in pixel space, LDMs, such as those explored by Tomasi et al. [18], perform the diffusion process in a compressed latent space [63]. This significantly reduces training and sampling costs. For downscaling, LDMs have demonstrated the ability to mimic kilometer-scale dynamical model outputs (e.g., COSMO-CLM simulations) with remarkable fidelity for variables like 2m temperature and 10m wind speed, outperforming U-Net and GAN baselines in spatial error, frequency distributions, and power spectra [18].

- Spatio-Temporal and Video Diffusion: Recognizing the temporal nature of climate data, models like Spatio-Temporal Video Diffusion (STVD) extend video generation techniques to precipitation downscaling [19]. These frameworks often use a two-step process: a deterministic module (e.g., a U-Net) provides an initial coarse prediction, and a conditional diffusion model learns to add the high-frequency residual details. In initial experiments, STVD was reported to outperform GANs in capturing accurate statistical distributions and fine-grained precipitation structures, particularly those influenced by topography.

- Hybrid Dynamical-Generative Downscaling: A state-of-the-art paradigm combines the strengths of physical models and generative AI. As proposed by Lopez-Gomez et al. [9], this approach uses a computationally cheap RCM to dynamically downscale ESM output to an intermediate resolution. A generative diffusion model then refines this output to the final target resolution. This hybrid method leverages the physical consistency and generalizability of the RCM and the sampling efficiency and textural fidelity of the diffusion model. This approach not only reduces computational costs by over 97% compared to full dynamical downscaling but also produces more accurate uncertainty bounds and better captures spectra and multivariate correlations than traditional statistical methods.

- Distributional Correction: To better capture extreme events, recent work has focused on aligning the generated distribution with the target distribution, particularly in the tails. Liu et al. [20] introduced a Wasserstein penalty into a score-based diffusion model to improve the representation of extreme precipitation, demonstrating more reliable calibration across intensities.

Spatiotemporal Models (LSTMs, ConvLSTMs, Transformers)

-

LSTMs/ConvLSTMs: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [67], a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), are designed to capture long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data. Convolutional LSTMs (ConvLSTMs) [68] extend LSTMs by replacing fully connected operations with convolutional operations, enabling them to process spatio-temporal data where inputs and states are 2D or 3D grids [68,69]. These models are particularly relevant for downscaling precipitation sequences or forecasting river runoff using atmospheric forcing.Strengths: Explicitly model temporal sequences and dependencies, crucial for variables with memory effects. Hybrid CNN-LSTM models can leverage the spatial feature extraction capabilities of CNNs and the temporal modeling strengths of LSTMs, often outperforming standalone models [69].Limitations: Standard LSTMs might struggle with very high-dimensional spatial inputs unless effectively combined with convolutional structures. Training these complex recurrent architectures can also be demanding. While ConvLSTMs are better suited for spatio-temporal data, their ability to capture very long-range spatial dependencies might be limited compared to other architectures like Transformers.

-

Transformers: Originally developed for natural language processing [70], Transformer architectures, particularly Vision Transformers (ViTs) [71] and their variants, are increasingly being adopted for climate science applications, including downscaling [22]. Their core mechanism, self-attention, allows the model to weigh the importance of all other locations in the input when making a prediction for a single location. This enables the modeling of global context and long-range spatial dependencies (i.e., teleconnections), a critical advantage over the local receptive fields of CNNs.Key innovations and applications in downscaling include:

- −

- Architectural Adaptations: Models like SwinIR (Swin Transformer for Image Restoration) and Uformer have been adapted from computer vision for downscaling temperature and wind speed, demonstrating superior performance over CNN baselines like U-Net [72]. For precipitation, PrecipFormer utilizes a window-based self-attention mechanism and multi-level processing to significantly reduce computational overhead while effectively capturing the localized and dynamic nature of rainfall [24].

- −

- Resolution-Agnostic and Zero-Shot Downscaling: A significant frontier is the development of models that can generalize across different resolutions without retraining. Curran et al. [21] demonstrated that a pretrained Earth Vision Transformer (EarthViT) could be trained to downscale from 50km to 25km and then successfully applied to a 3km resolution task in a zero-shot setting (i.e., without any fine-tuning on the new resolution). This capability is crucial for operational efficiency, as it avoids the costly process of retraining models for every new GCM or grid configuration [21]. Research comparing various architectures found that a Swin-Transformer-based approach combined with interpolation surprisingly outperformed neural operators in zero-shot downscaling tasks in terms of average error metrics [73].

- −

- Foundation Models: The power and scalability of the Transformer architecture have made it the backbone for emerging foundation models in weather and climate science. Models like FourCastNet [22], Prithvi-WxC [23], and ORBIT-2 [74] are pre-trained on massive climate datasets (e.g., decades of ERA5 reanalysis). While primarily designed for forecasting, their learned representations of Earth system dynamics make them promising candidates for downscaling via fine-tuning. This paradigm shifts the task from training a specialized model from scratch to adapting a large, pre-trained model, which may enhance transferability and reduce data requirements for specific downscaling tasks, though this remains an active area of research [23,75]. This paradigm shifts the task from training a specialized model from scratch to adapting a large, pre-trained model, which can enhance transferability and reduce data requirements for specific downscaling tasks.

Strengths: Transformers excel at modeling long-range spatial and temporal dependencies, a key physical aspect of the climate system. They show strong potential for transfer learning and zero-shot generalization, which could dramatically reduce the computational burden of downscaling large, multi-model ensembles. Recent benchmarks indicate that Transformer architectures can achieve competitive or superior performance in zero-shot generalization across resolutions compared to some neural operator approaches [21,73]. While these findings are promising, they represent early results rather than a settled state-of-the-art, and broader validation across datasets and variables will be necessary. ViTs and their adaptations like PrecipFormer [24] (which uses window-based self-attention and multi-level processing for efficiency) and EarthViT [21] have shown promise in capturing complex spatio-temporal patterns. They exhibit good potential for transferability, especially when combined with CNNs in hybrid architectures [28]. Foundation models built on Transformers, such as Prithvi WxC [23] and ORBIT-2 [74], are being developed for multi-task downscaling across various variables and geographies. FourCastNet[22], another transformer-based model, is a weather emulator designed to resolve and forecast high-resolution variables like surface wind speed and precipitation.Limitations: The primary challenge is the quadratic computational complexity of the self-attention mechanism ( where N is the number of input patches), which can be prohibitive for very high-resolution data. However, innovations like window-based attention (Swin, PrecipFormer) and other efficient attention mechanisms are actively addressing this bottleneck [24]. Practically, their data-hungry nature means they benefit most from large-scale pre-training, making foundation models a key pathway for their effective use.

5. The Physical Frontier: Hybrid and Physics-Informed Downscaling

5.1. The Imperative for Physical Consistency

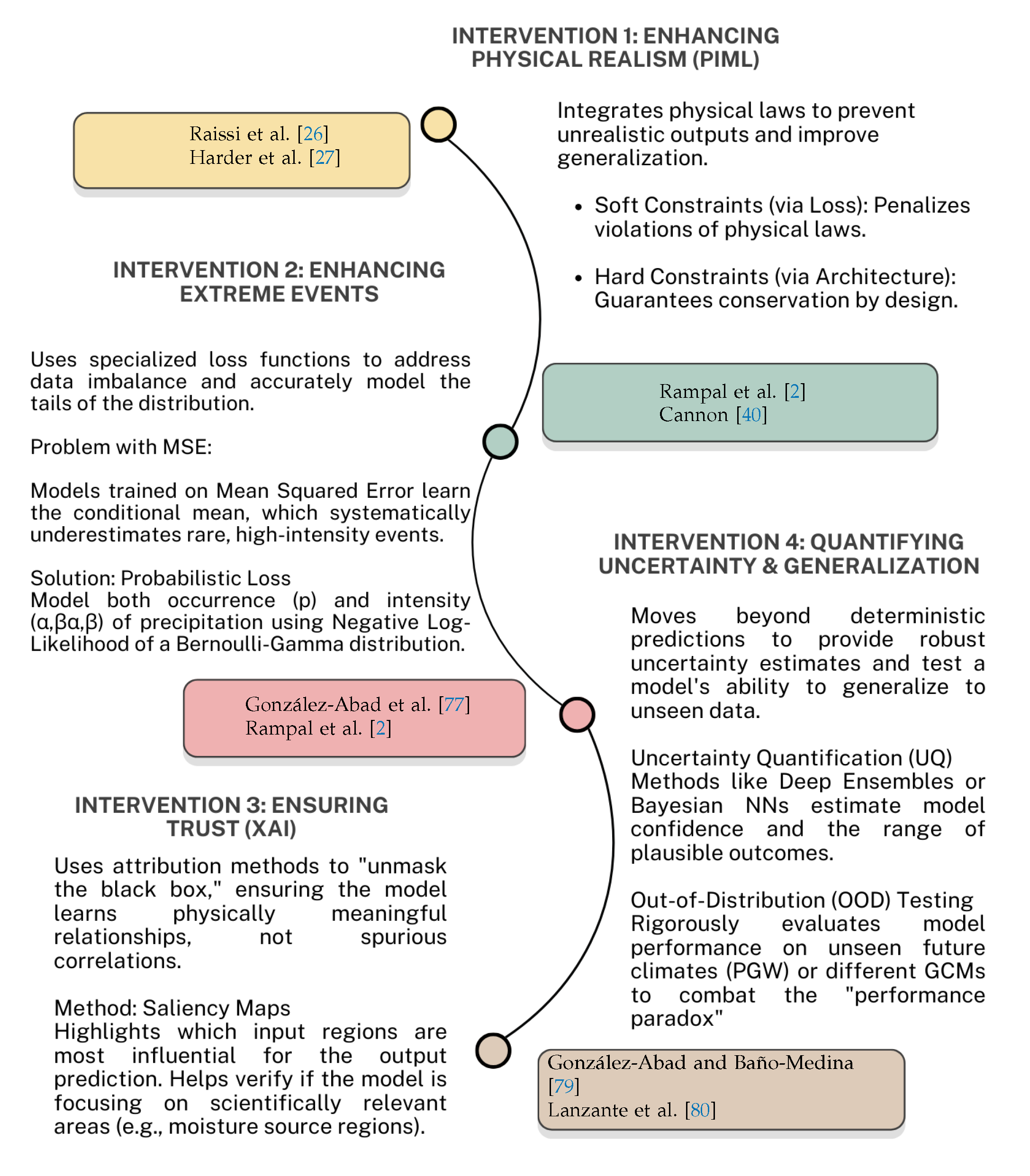

5.2. Architectural Integration of Physical Laws: PIML

- Soft Constraints

- This is the most common approach, where the standard data-fidelity loss term () is augmented with a physics-based penalty term () [78]. The total loss becomes , where is a weighting hyperparameter. is formulated as the residual of a governing differential equation (e.g., the continuity equation for mass conservation). By minimizing this residual across the domain, the network is encouraged, but not guaranteed, to find a physically consistent solution. This method is flexible and has been used to penalize violations of conservation laws [25] and to solve complex PDEs [26].A common example is enforcing mass conservation in precipitation downscaling. If x is the value of a single coarse-resolution input pixel and are the n corresponding high-resolution output pixels from the neural network, a soft constraint can be added to the loss function to penalize deviations from the conservation of mass. In other words, the sum of the smaller pixels cannot be larger than the value of the corresponding coarse pixel. The total loss, , becomes a weighted sum of the data fidelity term (e.g., Mean Squared Error, ) and a physics penalty term:where is a hyperparameter that controls the strength of the physical penalty. Minimizing this loss encourages, but does not guarantee, that the mean of the high-resolution patch matches the coarse-resolution value.

- Hard Constraints (Constrained Architectures)

-

This approach modifies the neural network architecture itself to strictly enforce physical laws by design. For example, Harder et al. [27] introduced specialized output layers that guarantee mass conservation by ensuring that the sum of the high-resolution output pixels equals the value of the coarse-resolution input pixel. Such methods provide an absolute guarantee of physical consistency for the constrained property, which can improve both performance and generalization. While more difficult to design and potentially less flexible than soft constraints, they represent a more robust method for embedding inviolable physical principles [27]. In contrast of soft consrtraints, a hard constraint enforces the physical law by design, often through a specialized, non-trainable output layer. Continuing the mass conservation example, let be the raw, unconstrained outputs from the final hidden layer of the network. A multiplicative constraint layer can be designed to produce the final, constrained outputs that are guaranteed to conserve mass:This layer rescales the raw outputs such that their sum is precisely equal to , thereby strictly enforcing the conservation law at every forward pass, without the need for a penalty term in the loss function.

5.3. Hybrid Frameworks: Merging Dynamical and Statistical Strengths

- An initial, computationally inexpensive dynamical downscaling step using an RCM to bring coarse ESM output to an intermediate resolution (e.g., from 100km to 45km). This step grounds the output in a physically consistent dynamical state.

- A subsequent generative ML step, using a conditional diffusion model, to perform the final super-resolution to the target scale (e.g., from 45km to 9km). The diffusion model learns to add realistic, high-frequency spatial details.

5.4. Enforcing Physical Realism in Practice

5.4.1. The Frontier of Physics-Informed Machine Learning (PIML)

The Promise of Physics-ML Integration

- Ensuring Conservation Laws: Models can be designed or constrained to conserve fundamental quantities like mass and energy [8].

- Maintaining Thermodynamic Consistency: Predictions can be guided to adhere to known thermodynamic relationships (e.g., between temperature, humidity, and precipitation).

- Reducing Data Requirements: By embedding prior physical knowledge, PIML models may require less training data to achieve good performance compared to purely data-driven approaches, as the physical laws provide strong regularization [26].

- Improving Extrapolation: Models that respect physical principles are hypothesized to extrapolate more reliably to unseen conditions, as these principles are expected to hold even when statistical relationships change.

Implementation Approaches for PIML

-

Hard Constraints: This approach involves modifying the neural network architecture or adding specific constraint layers at the output to strictly guarantee that certain physical laws are satisfied [27]. For example, a constraint layer could ensure that the total precipitation over a downscaled region matches the coarse-grid precipitation input, thereby enforcing water mass conservation.Advantages: Guarantees physical consistency for the enforced laws.Disadvantages: Can be more challenging to design and may limit the model’s flexibility if the constraints are too restrictive or incorrectly formulated.

-

Soft Constraints via Loss Functions: This is the more common approach, where penalty terms representing deviations from physical laws are added to the overall loss function that the model minimizes during training [26].Advantages: More flexible than hard constraints and can potentially incorporate multiple physical principles simultaneously. Easier to implement for complex, non-linear PDEs.Disadvantages: Does not strictly guarantee constraint satisfaction, only encourages it. The choice of weighting for the physics-based loss term () can be critical and may require careful tuning.

- Hybrid Statistical–Dynamical Models: As discussed previously, these models combine ML with components of traditional dynamical models [8]. ML can be used to emulate specific, computationally expensive parameterizations within an RCM, or to learn corrective terms for RCM biases. This approach inherently leverages the physical basis of the dynamical model components.

Case Studies and Results

6. Data, Variables, and Preprocessing Strategies in ML-Based Downscaling

6.1. Common Predictor Datasets (Low-Resolution Inputs)

- ERA5 Reanalysis:

- The fifth generation ECMWF atmospheric reanalysis, ERA5, is extensively used as a source of predictor variables, particularly for training models in a "perfect-prognosis" framework [83,84]. ERA5 provides a globally complete and consistent, high-resolution (relative to GCMs, typically 31 km or 0.25°) gridded dataset of many atmospheric, land-surface, and oceanic variables from 1940 onwards, assimilating a vast amount of historical observations. Its physical consistency and observational constraint make it an ideal training ground for ML models to learn relationships between large-scale atmospheric states and local climate variables. Often, models trained on ERA5 are subsequently applied to downscale GCM projections.

- CMIP5/CMIP6 GCM Outputs:

- Outputs from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) and Phase 6 (CMIP6) GCMs are indispensable when the objective is to downscale future climate projections under various emission scenarios (e.g., Representative Concentration Pathways - RCPs, or Shared Socioeconomic Pathways - SSPs). These GCMs provide the large-scale atmospheric forcing necessary for projecting future climate change. However, their coarse resolution and inherent biases necessitate downscaling and often bias correction before their outputs can be used for regional impact studies [10,84].

- CORDEX RCM Outputs:

- Data from the Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling Experiment (CORDEX) are also utilized, particularly when ML techniques are employed for further statistical refinement of RCM outputs, as RCM emulators, or in hybrid downscaling approaches. CORDEX provides dynamically downscaled climate projections over various global domains, offering higher resolution than GCMs and incorporating regional climate dynamics. However, these outputs may still require further downscaling for very local applications or may possess biases that ML can help correct.

6.2. High-Resolution Reference Datasets (Target Data)

- Gridded Observational Datasets:

- Products like PRISM (Parameter-elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model) for North America [8,85], Iberia01 for the Iberian Peninsula [86], E-OBS for Europe [87], and regional datasets like REKIS [88] are commonly used [8]. PRISM, for example, provides high-resolution (e.g., 800m or 4km) daily temperature and precipitation data across the conterminous United States, incorporating physiographic influences like elevation and coastal proximity into its interpolation [85]. These datasets are invaluable for training models in a perfect-prognosis setup, where historical observations are used as the target.

- Satellite-Derived Products:

- Satellite observations offer global or near-global coverage and are increasingly used as reference data. Notable examples include the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission’s Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) products for precipitation [89] and the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission for soil moisture [90]. GPM IMERG, for instance, provides precipitation estimates at resolutions like 0.1° and 30-minute intervals, with various products (Early, Late, and Final Run) catering to different latency and accuracy requirements [89].

- Regional Reanalyses or High-Resolution Simulations:

- In some cases, outputs from high-resolution regional reanalyses or dedicated RCM simulations (sometimes run specifically for the purpose of generating training data) are used as the "truth" data, especially when high-quality gridded observations are scarce [29].

- FluxNet:

- For variables related to land surface processes and evapotranspiration, data from the FluxNet network of eddy covariance towers provide valuable site-level observational data for model validation [91]. These towers measure exchanges of carbon dioxide, water vapor, and energy between ecosystems and the atmosphere.

6.3. Key Downscaled Variables

- Daily Precipitation and 2-meter Temperature: These are the most commonly downscaled variables due to their direct relevance for impact studies (e.g., agriculture, hydrology, health). This includes mean, minimum, and maximum temperatures.

- Multivariate Downscaling: There is a growing trend towards downscaling multiple climate variables simultaneously (e.g., temperature, precipitation, wind speed, solar radiation, humidity). This is important for ensuring physical consistency among the downscaled variables.

- Spatial/Temporal Scales: Typical downscaling efforts aim to increase resolution from GCM/Reanalysis scales of 25-100 km to target resolutions of 1-10 km, predominantly at a daily temporal resolution.

6.4. Feature Engineering and Selection

- Static Predictors:

- High-resolution static geographical features such as topography (including elevation, slope, and aspect), land cover type, soil properties, and climatological averages are frequently incorporated as additional predictor variables. These features provide crucial local context that is often unresolved in coarse-scale GCM or reanalysis outputs. For instance, orography heavily influences local precipitation patterns and temperature lapse rates, while land cover affects surface energy balance and evapotranspiration [44,85]. The inclusion of these static predictors allows ML models to learn how large-scale atmospheric conditions interact with local surface characteristics to produce fine-scale climate variations.

- Dynamic Predictors:

- For specific variables like soil moisture, dynamic predictors such as Land Surface Temperature (LST) and Vegetation Indices (e.g., NDVI, EVI) derived from satellite remote sensing are often used, as these variables capture short-term fluctuations related to surface energy and water balance [92].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Collinearity:

- When dealing with a large number of potential predictors, dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are sometimes employed to reduce the number of input features while retaining most of the variance. This can help to mitigate issues related to collinearity among predictors and reduce computational load. Regularization techniques (e.g., L1 or L2 regularization) embedded within many ML models also implicitly handle collinearity by penalizing large model weights.

6.5. Data Preprocessing Challenges

- Data-Scarce Areas: A significant hurdle is the availability of sufficient high-quality, high-resolution reference data for training and validation, especially in many parts of the developing world or in regions with complex terrain where observational networks are sparse [93].

- Imbalanced Data for Extreme Events: Extreme climatic events (e.g., heavy precipitation, heatwaves) are, by definition, rare. This leads to imbalanced datasets where extreme values are underrepresented, potentially biasing ML models (trained with standard loss functions like MSE) to perform well on common conditions but poorly on these critical, high-impact events. This issue often hinders models from learning the specific characteristics of extremes.

- Ensuring Domain Consistency: Predictor variables derived from GCM simulations may exhibit different statistical properties (e.g., means, variances, distributions) and systematic biases compared to reanalysis data (like ERA5) often used for model training. This mismatch, known as a domain or covariate shift, can degrade model performance and is a critical preprocessing consideration. This occurs because GCMs often have systematic biases and different statistical properties than reanalysis data, even for historical periods, thereby violating the assumption that training and application data are drawn from the same distribution. Techniques such as bias correction of GCM predictors, working with anomalies by removing climatological means from both predictor and predictand data to focus on changes, or more advanced domain adaptation methods are employed to mitigate this critical issue and enhance consistency [94].

- Quality Control and Gap-Filling: Observational and satellite-derived datasets frequently require substantial preprocessing steps, including quality control to remove erroneous data, and gap-filling techniques (e.g., interpolation) to handle missing values due to sensor malfunction or environmental conditions (like cloud cover for satellite imagery) [95].

7. A Prescriptive Protocol for Model Evaluation

7.1. Protocol for Precipitation Downscaling

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): Report as a baseline metric for average error, but acknowledge its limitations in penalizing realistic high-frequency variability.

- Fraction Skill Score (FSS): This is the primary metric [96] for spatial accuracy. FSS should be reported for multiple intensity thresholds and spatial scales to assess performance across different event types. Based on common practice in forecast verification, we recommend thresholds relevant to hydrological impacts depending on usual severity of precipitation in that area and return period, for instance 1, 5, and 20 mm/day. The analysis should show FSS as a function of neighborhood size, with recommended spatial scales of the area in hand. We can take 10, 20, 40, and 80 km as an example; however, these values need to be carefully chosen to identify the scale at which the forecast becomes skillful.

- High-Quantile Error: To specifically evaluate performance on extremes, report the bias or absolute error for a high quantile of the daily precipitation distribution, such as the 99th or 99.5th percentile. This directly measures the model’s ability to capture the magnitude of rare, intense events.

- Power Spectral Density (PSD): Plot the 1D radially-averaged power spectrum of the downscaled precipitation fields against the reference data. This is a critical diagnostic for spatial realism. An overly steep slope indicates excessive smoothing, while a shallow slope or bumps at high frequencies can indicate unrealistic noise or GAN-induced artifacts.

- Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS): For probabilistic models (e.g., GAN or Diffusion ensembles), the CRPS [97] is the gold-standard metric for overall skill, as it evaluates the entire predictive distribution. It should be reported as the primary probabilistic skill score.

7.2. Protocol for Temperature Downscaling

- RMSE and Bias: Report the overall Root Mean Squared Error and Mean Bias (downscaled minus reference) as standard metrics of accuracy and systematic error.

- Power Spectral Density (PSD): As with precipitation, the PSD is crucial for ensuring that the downscaled temperature fields contain realistic spatial variability and are not overly smoothed by the model.

- Distributional Metrics (e.g., Wasserstein Distance): Compare the full probability distributions of downscaled and reference temperatures using a robust metric like the Wasserstein Distance. This provides a more complete picture of performance than just comparing means and variances, capturing shifts in the shape and tails of the distribution.

- Reliability Diagram (for probabilistic models): If the model produces probabilistic forecasts (e.g., ensembles), a reliability diagram is essential. It plots the observed frequency of an event against the forecast probability, providing a direct visual assessment of calibration. A well-calibrated model should lie along the 1:1 diagonal line.

7.3. Comparative Analysis and State-of-the-Art

- For spatial structure and deterministic accuracy, U-Net and ResNet-based CNNs remain strong contenders, particularly for smoother variables like temperature. Their inductive bias for local patterns is highly effective for learning topographically-induced climate variations [8].

- For probabilistic outputs and UQ, Diffusion models are emerging as the state-of-the-art due to their stable training and ability to generate high-fidelity, diverse ensembles [9,18]. They often outperform GANs on distributional metrics. As a simple, strong baseline for epistemic uncertainty, report deep ensembles [99] with CRPS and reliability diagnostics.

- For transferability and zero-shot generalization, Transformer-based foundation models represent the cutting edge. Their ability to learn from vast, diverse datasets enables generalization to new resolutions and regions with minimal fine-tuning, a critical capability for operational scalability [21].

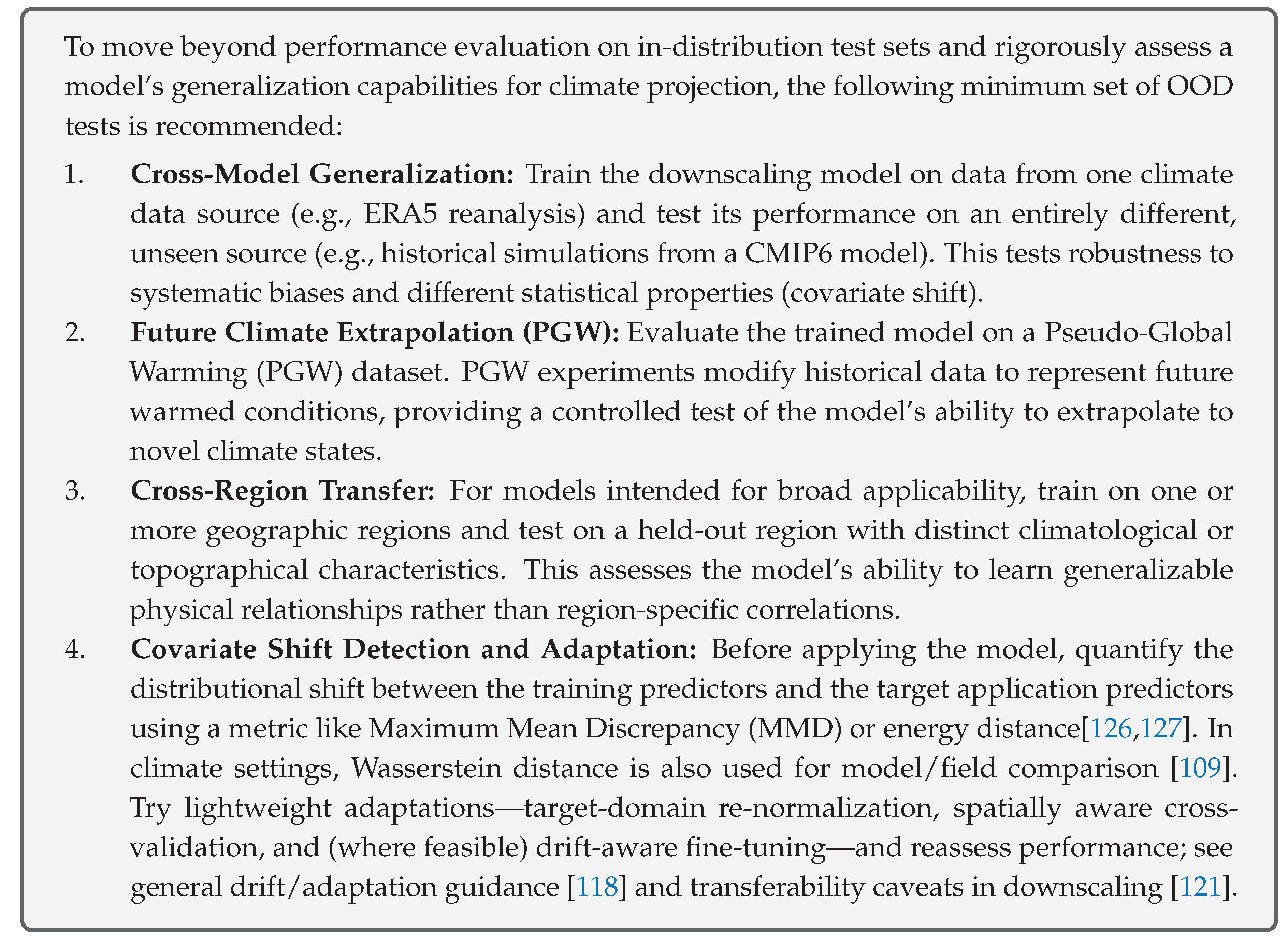

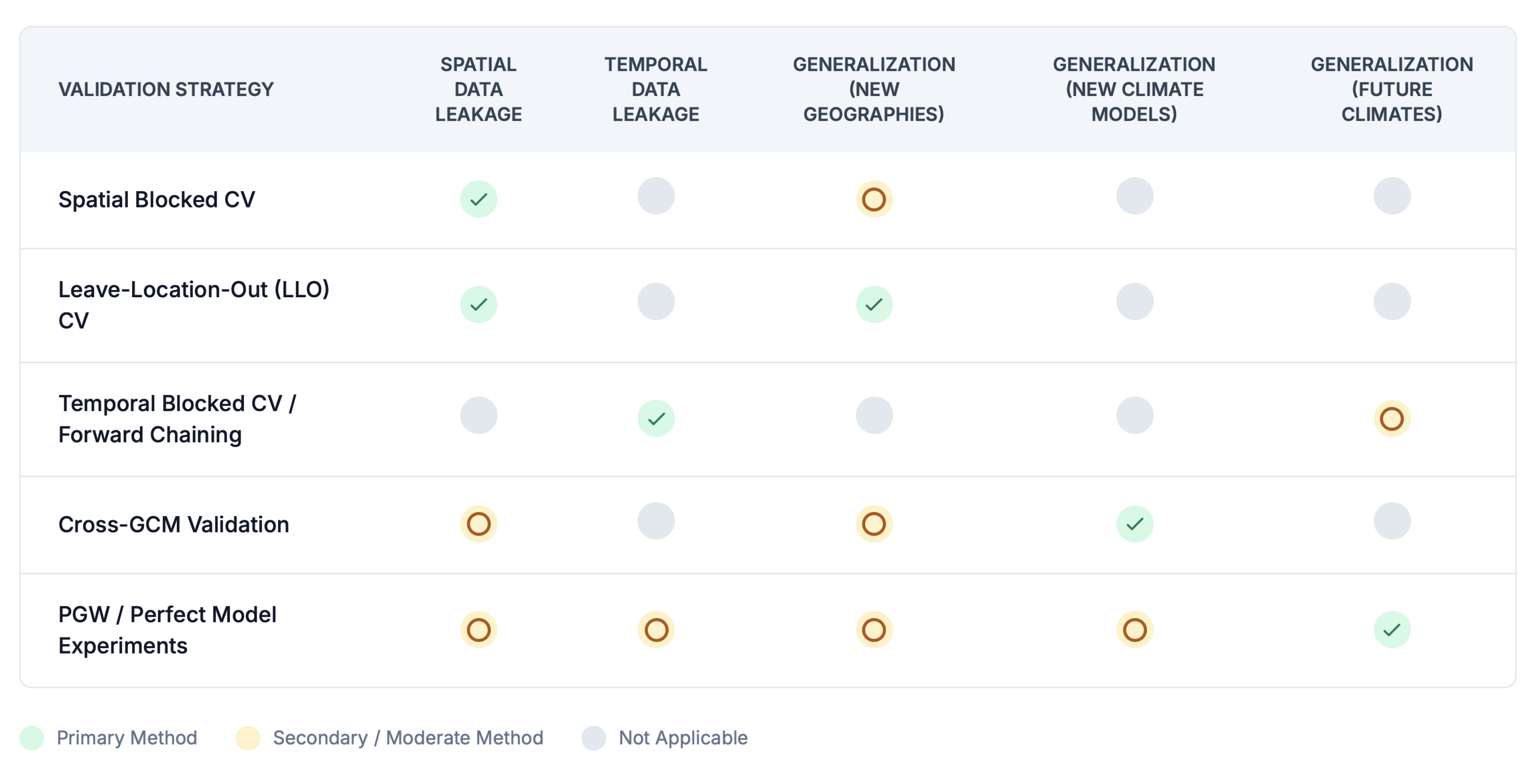

7.4. Validation Under Non-Stationarity

7.4.1. Pseudo-Global Warming (PGW) Experiments

7.4.2. Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation

- Models might be pre-trained on large, diverse datasets (e.g., multiple GCMs, long historical records) to learn general, invariant features of atmospheric processes.

- These pre-trained models can then be fine-tuned on smaller, target-specific datasets (e.g., data for a particular region, a specific future period, or a new GCM) [28]. This approach can lead to better generalization and reduce the amount of target-specific data needed for training. However, careful validation is crucial to ensure that the transferred knowledge is beneficial and does not introduce biases from the source domain. Prasad et al. [28] demonstrated that pre-training on diverse climate datasets can enhance zero-shot transferability for some downscaling tasks, but fine-tuning often remains necessary for optimal performance on distinct target domains like different GCM outputs.

7.4.3. Process-Informed Architectures and Predictor Selection

- Encoding known physical relationships into the network architecture: This might involve designing specific layers or connections that mimic physical processes or constraints.

- Using physically-motivated predictor variables: Selecting input variables that have a clear and robust physical link to the predictand (e.g., thermodynamic variables like potential temperature, specific humidity, or large-scale circulation indices known to influence local weather) rather than relying on a large set of potentially collinear or causally weak predictors.

7.4.4. Validation Strategies for Non-Stationary Conditions

- Perfect Model Framework (Pseudo-Reality Experiments): In this setup, output from a high-resolution GCM or RCM simulation is treated as the “perfect” truth [80]. Coarsened versions of this output are used to train the ML downscaling model, which then attempts to reconstruct the original high-resolution “truth”. This framework allows for testing the ML model’s ability to downscale under different climate states (e.g., historical vs. future periods from the same GCM/RCM), as the “truth” is known for all periods. This is crucial for evaluating extrapolation capabilities.

- Cross-GCM Validation: Models are trained on a subset of available GCMs and then tested on GCMs that were not included in the training set. This assesses the model’s ability to generalize to climate model outputs with different structural characteristics and biases.

- Temporal Extrapolation (Out-of-Sample Testing): Using the most recent portion of the historical record or specific periods with distinct climatic characteristics (e.g., the warmest historical years as proxies for future conditions) exclusively for testing, after training on earlier data [8]. This provides a more stringent test of generalization than random cross-validation.

- Process-Based Evaluation: Beyond statistical metrics, evaluating whether the downscaled outputs maintain plausible physical relationships between variables (e.g., temperature–precipitation scaling, wind–pressure relationships) and accurately represent key climate processes (e.g., diurnal cycles, seasonal transitions, extreme event characteristics) under different climate conditions. XAI techniques can play a role here in verifying if the model is relying on physically sound mechanisms.

7.5. A Multi-Faceted Toolkit for Model Evaluation

Uncertainty Baselines

7.6. Operational Relevance: Beyond Statistical Skill

- Computational Cost: Dynamical downscaling is exceptionally expensive, limiting its use for large ensembles. ML offers a computationally cheaper alternative by orders of magnitude [9,112]. However, costs vary within ML: inference with CNNs is fast, while the iterative sampling of diffusion models is slower. Training large foundation models requires massive computational resources, but once trained, fine-tuning and inference can be efficient [23]. The hybrid dynamical-generative approach offers a compelling trade-off, drastically cutting the cost of the most expensive part of the physical simulation pipeline [9].

- Interpretability: As discussed in Section 9.2.2, the "black-box" nature of deep learning is a major barrier to operational trust. The ability to use XAI tools to verify that a model is learning physically meaningful relationships, rather than spurious "shortcuts," is crucial for deployment in high-stakes applications.

- Robustness and Generalization: The single most important factor for operational relevance is a model’s ability to generalize to out-of-distribution(OOD) data, namely future climate scenarios. As detailed in Section 9.1, models that fail under covariate or concept drift are not operationally viable for climate projection. Therefore, rigorous OOD evaluation using techniques like cross-GCM validation and Pseudo-Global Warming (PGW) experiments is a prerequisite for deployment.

- Baselines: Always include strong classical comparators (e.g., BCSD/quantile-mapping and LOCA) as default references alongside modern DL models; these remain common operational choices in hydrologic and climate-services pipelines [33,34]. Formal assessments and national products continue to operationalize statistical interfaces between GCMs and impacts—bias adjustment and empirical/statistical downscaling (e.g., LOCA2, STAR-ESDM)—as default pathways, which underscores why ML downscalers must demonstrate clear, application-relevant added value [113,114].

8. Critical Investigation of Model Performance and Rationale

8.1. Rationale for Model Choices

- CNNs/U-Nets for Spatial Patterns:

- These architectures are predominantly chosen for their proficiency in learning hierarchical spatial features from gridded data. Convolutional layers are adept at identifying local patterns, while pooling layers capture broader contextual information. U-Nets, with their encoder-decoder structure and skip connections, are particularly favored for tasks requiring precise spatial localization and preservation of fine details, making them well-suited for downscaling variables like temperature and precipitation where spatial structure is paramount [8].

- LSTMs/ConvLSTMs for Temporal Dependencies:

- When the temporal evolution of climate variables and their sequential dependencies are critical (e.g., for daily precipitation sequences or hydrological runoff forecasting), LSTMs and ConvLSTMs are preferred due to their recurrent nature and ability to capture long-range temporal patterns.

- GANs/Diffusion Models for Realistic Outputs and Extremes:

- These generative models are selected when the objective is to produce downscaled fields that are not only statistically accurate but also perceptually realistic, with sharp gradients and a better representation of the full statistical distribution, including extreme events [8].

- Transformers for Long-Range Dependencies:

8.2. Factors Contributing to Model Success

- Appropriate Architectural Design: Matching the model architecture to the inherent characteristics of the data and the downscaling task is paramount. For instance, CNNs are well-suited for gridded spatial data, while LSTMs excel with time series. The incorporation of architectural enhancements like residual connections and the skip connections characteristic of U-Nets have proven crucial for training deeper models and preserving fine-grained spatial detail.

- Effective Feature Engineering: The performance of ML models is significantly boosted by the inclusion of relevant predictor variables. In particular, incorporating high-resolution static geographical features such as topography, land cover, and soil type provides essential local context that coarse-resolution GCMs or reanalysis products inherently lack. This allows the model to learn how large-scale atmospheric conditions are modulated by local surface characteristics.

- Quality and Representativeness of Training Data: The availability of sufficient, high-quality, and representative training data is fundamental. Data augmentation techniques, such as rotation or flipping of input fields, can expand the training set and improve model generalization, especially for underrepresented phenomena like extreme events [14,115].

- Appropriate Loss Functions: The choice of loss function used during model training significantly influences the characteristics of the downscaled output. While standard loss functions like MSE are common, they can lead to overly smooth predictions and poor representation of extremes. Tailoring loss functions to the specific task—for example, using quantile loss, Bernoulli-Gamma loss for precipitation (which models occurrence and intensity separately), Dice loss for imbalanced data, or the adversarial loss in GANs for perceptual quality—can lead to substantial improvements in capturing critical aspects of the climate variable’s distribution [8]. Studies show that L1 and L2 loss functions perform differently depending on data balance, with L2 often being better for imbalanced data like precipitation [116].

- Rigorous Validation Frameworks: The use of robust validation strategies, including out-of-sample testing and standardized evaluation metrics beyond simple error scores (e.g., the VALUE framework [117]), is crucial for assessing true model skill and generalizability.

8.3. Factors Hindering Model Learning

- Overfitting: Models may learn noise or spurious correlations present in the specific training dataset, leading to excellent performance on seen data but poor generalization to unseen data. This is a common issue, especially with highly flexible DL models and limited or non-diverse training data.

-

Poor Generalization (The "Transferability Crisis"), Covariate Shift, Concept Drift, and Shortcut Learning: A major and persistent challenge is the failure of models to extrapolate reliably to conditions significantly different from those encountered during training. This ’transferability crisis’ is the core of the "performance paradox" and is rooted in the violation of the stationarity assumption. It can be rigorously framed using established machine learning concepts:

- −

- Covariate Shift: This occurs when the distribution of input data, , changes between training and deployment, while the underlying relationship remains the same [118]. In downscaling, this is guaranteed when applying a model trained on historical reanalysis (e.g., ERA5) to the outputs of a GCM, which has its own systematic biases and statistical properties. It also occurs when projecting into a future climate where the statistical distributions of atmospheric predictors (e.g., mean temperature, storm frequency) have shifted.

- −

- Concept Drift: This is a more fundamental challenge where the relationship between predictors and the target variable, , itself changes [118]. Under climate change, the physical processes linking large-scale drivers to local outcomes might be altered (e.g., changes in atmospheric stability could alter lapse rates). A mapping learned from historical data may therefore become invalid.

- −

- Shortcut Learning: This phenomenon provides a mechanism to explain why models are so vulnerable to these shifts [119]. Models often learn "shortcuts"—simple, non-robust decision rules that exploit spurious correlations in the training data instead of the true underlying physical mechanisms [119]. For example, a model might learn to associate a specific GCM’s known regional cold bias with a certain type of downscaled precipitation pattern. This shortcut works perfectly for that GCM but fails completely when applied to a different, unbiased GCM or to the real world, leading to poor OOD performance. The finding by González-Abad et al. [77] that models may rely on spurious teleconnections is a prime example of shortcut learning in this domain.

The difficulty in generalizing to these OOD conditions is therefore a core impediment. High performance on historical, in-distribution test data provides no guarantee of reliability for future projections, necessitating strategies focused on robustness, physical understanding, and OOD detection. - Lack of Physical Constraints: Purely data-driven ML models, optimized solely for statistical accuracy, can produce outputs that are physically implausible or inconsistent (e.g., violating conservation laws). This lack of physical grounding can severely limit the trustworthiness and utility of downscaled projections.

- Data Limitations: Insufficient training data, particularly for rare or extreme events, remains a significant bottleneck. Data scarcity in certain geographical regions also poses a challenge for developing globally applicable models. Furthermore, the lack of training data that adequately represents the full range of potential future climate states can hinder a model’s ability to project future changes accurately.

- Inappropriate Model Complexity: Choosing an inappropriate level of model complexity can be detrimental. Models that are too simple may underfit the data, failing to capture complex relationships. Conversely, overly complex models are prone to overfitting, may be more difficult to train, and can be computationally prohibitive.

- Training Difficulties (e.g., Vanishing/Exploding Gradients): In very deep neural networks, especially plain CNNs without architectural aids like residual connections, the gradients used for updating model weights can become infinitesimally small (vanishing) or excessively large (exploding), hindering the learning process.

- Input Data Biases and Inconsistencies: Systematic biases present in GCM outputs, or inconsistencies between the statistical characteristics of training data (e.g., reanalysis) and application data (e.g., GCM outputs from a different model or future period), representing a significant covariate shift as discussed previously, can significantly degrade downscaling performance. Preprocessing steps, such as bias correction of predictors or working with anomalies by removing climatology, are often crucial for mitigating these issues [80].

8.4. Comparative Analysis of ML Approaches

9. Overarching Challenges in ML-Based Climate Downscaling

9.1. Transferability and Domain Adaptation: The Achilles’ Heel

- Extrapolation to Future Climates: Models trained exclusively on historical climate data often struggle to perform reliably when applied to future climate scenarios characterized by significantly different mean states, altered atmospheric dynamics, or novel patterns of variability. Studies by Hernanz et al. [121] demonstrated catastrophic drops in CNN performance when applied to future projections or GCMs not included in the training set. The models may learn statistical relationships that are valid for the historical period but do not hold under substantial climate change.

- Cross-GCM/RCM Transfer: Due to inherent differences in model physics, parameterizations, resolutions, and systematic biases, ML models trained to downscale the output of one GCM or RCM often exhibit degraded performance when applied to outputs from other climate models. This limits the ability to readily apply a single trained downscaling model across a multi-model ensemble.

- Spatial Transferability: A model developed and trained for a specific geographical region may not transfer effectively to other regions with different climatological characteristics, topographic complexities, or land cover types. Local adaptations are often necessary, which can be data-intensive.

- Domain Adaptation Techniques: These methods aim to explicitly adapt a model trained on a "source" domain (e.g., historical data from one GCM) to perform well on a "target" domain (e.g., future data from a different GCM) where labeled high-resolution data may be scarce or unavailable [8].

- Training on Diverse Data: A common strategy is to pre-train ML models on a wide array of data encompassing multiple GCMs, varied historical periods, and diverse geographical regions. The hypothesis is that exposure to greater variability will help the model learn more robust and invariant features that generalize better. For instance, Prasad et al. [28] found that training on diverse datasets (ERA5, MERRA2, NOAA CFSR) led to good zero-shot transferability for some tasks, though fine-tuning was still necessary for others, such as the two-simulation transfer involving NorESM data.

- Pseudo-Global Warming (PGW) Experiments: This approach involves training or evaluating models using historical data that has been perturbed to mimic certain aspects of future climate conditions (e.g., by adding a GCM-projected warming signal). This allows for a more systematic assessment of a model’s extrapolation capabilities under changed climatic states.

-

Causal Machine Learning: There is growing interest in developing ML approaches that aim to learn underlying causal physical processes rather than just statistical correlations. Such models are hypothesized to be inherently more robust to distributional shifts.The challenge of transferability implies that simply achieving high accuracy on a historical test set is insufficient. For ML-downscaled projections to be credible for future climate impact assessments, models must demonstrate robustness across different climate states and sources of climate model data.

Case Studies (Quantitative Case Studies)

- Cross-model transfer (temperature UNet emulator). In a pseudo-reality experiment, daily RMSE for a UNet emulator rose from ∼0.9°C when evaluated on the same driving model used for training (UPRCM) to ∼2–2.5°C when applied to unseen ESMs; for warm extremes (99th percentile) under future climate, biases were mostly within C but reached up to C in some locations, and were larger than a linear baseline [121].

- GAN downscaling artifacts (near-surface winds). Deterministic GAN super-resolution exhibited systematic low-variance (low-power) bias at fine scales and, under some partial frequency-separation settings, isolated high-power spikes at intermediate wavenumbers; allowing the adversarial loss to act across all frequencies restored fine-scale variance, but it also raised pixelwise errors via the double-penalty effect.” [98].

- Classical SD variability & bias pitfalls (VALUE intercomparison). In a 50+ method cross-validation over Europe, several linear-regression SD variants showed very large precipitation biases—sometimes worse than raw model outputs—while some MOS techniques systematically under- or over-estimated variability (e.g., ISI-MIP under, DBS over), underscoring that method class alone does not guarantee robustness [5].

9.2. Physical Consistency and Interpretability

9.2.1. Ensuring Physically Plausible Outputs

-

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Constrained Learning:

- −

- Soft Constraints: This approach involves incorporating penalty terms into the model’s loss function that discourage violations of known physical laws. The total loss becomes a weighted sum of a data-fidelity term and a physics-based regularization term (e.g., ). Physics-informed loss functions have been explored to guide models towards more physically realistic solutions. While soft constraints can reduce the frequency and magnitude of physical violations, they may not eliminate them entirely and can introduce a trade-off between statistical accuracy and physical consistency [25].

- −

- Hard Constraints: These methods aim to strictly enforce physical laws by design, either by modifying the neural network architecture itself or by adding specialized output layers that ensure the predictions satisfy the constraints. Harder et al. [27] introduced additive, multiplicative, and softmax-based constraint layers that can guarantee, for example, mass conservation between low-resolution inputs and high-resolution outputs. Such hard-constrained approaches have been shown to not only ensure physical consistency but also, in some cases, improve predictive performance and generalization [27]. The rationale for PINNs includes reducing the dependency on large datasets and enhancing model robustness by ensuring physical consistency, especially in data-sparse regions or for out-of-sample predictions [26]. Recent work explores Attention-Enhanced Quantum PINNs (AQ-PINNs) for climate modeling applications like fluid dynamics, aiming for improved accuracy and computational efficiency [128].

- Hybrid Dynamical-Statistical Models: Another avenue is to combine the strengths of ML with traditional physics-based dynamical models (RCMs). This can involve using ML to emulate computationally expensive components of RCMs, to statistically post-process RCM outputs (e.g., for bias correction or further downscaling), or to develop hybrid frameworks where ML and dynamical components interact [8,29]. For example, "dynamical-generative downscaling" approaches combine an initial stage of dynamical downscaling with an RCM to an intermediate resolution, followed by a generative AI model (like a diffusion model) to further refine the resolution to the target scale. This leverages the physical consistency of RCMs and the efficiency and generative capabilities of AI [9]. Such hybrid models aim to achieve a balance between computational feasibility, physical realism, and statistical skill.

9.2.2. Explainable AI (XAI): Unmasking the "Black Box"

9.2.2.1. The Need for Interpretability

- Model Validation and Debugging: Understanding which input features a model relies on can help identify if it has learned scientifically meaningful relationships or if it is exploiting spurious correlations or artifacts in the training data. Understanding which input features a model relies on can help identify if it has learned scientifically meaningful relationships or if it is exploiting spurious correlations or artifacts in the training data - a phenomenon of shortcut learning where models may appear "right for the wrong reasons".

- Scientific Discovery: XAI can potentially reveal novel insights into climate processes by highlighting unexpected relationships learned by the model.

- Building Trust: Transparent models whose decision-making processes align with physical understanding are more likely to be trusted by domain scientists and policymakers.

- Identifying Biases: XAI can help uncover hidden biases in the model or the data it was trained on.

9.2.2.2. Common XAI Techniques Applied to Downscaling

- Saliency Maps and Feature Attribution: Methods like Integrated Gradients, DeepLIFT, and Layer-Wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) aim to attribute the model’s output (e.g., a high-resolution pixel value) back to the input features (e.g., coarse-resolution predictor fields), highlighting which parts of the input were most influential [8]. González-Abad et al. [77] introduced aggregated saliency maps for CNN-based downscaling, revealing that models might rely on spurious teleconnections or ignore important physical predictors. LRP has been adapted for semantic segmentation tasks in climate science, like detecting tropical cyclones and atmospheric rivers, to investigate whether CNNs use physically plausible input patterns [129].

- Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM): This technique produces a coarse localization map highlighting the important regions in the input image for predicting a specific class (or, adapted for regression, a specific output value) [130]. While useful for visualization, Grad-CAM may not differentiate well between input variables [129].

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Based on cooperative game theory, SHAP values explain the prediction of an instance by computing the contribution of each feature to the prediction [131]. SHAP has been noted for its ability to reveal features that degrade forecast accuracy, though it may inaccurately rank significant features in some contexts [132].

9.2.2.3. Challenges in XAI for Climate Downscaling

- Faithfulness and Plausibility: Ensuring that explanations truly reflect the model’s internal decision-making process (faithfulness) and are consistent with physical understanding (plausibility) is challenging [133]. Different XAI methods can yield different, sometimes conflicting, explanations for the same prediction [134].

- Relating Attributions to Physical Processes: While methods like integrated gradients are mathematically sound, the resulting attribution maps can be difficult to directly relate to specific, understandable physical processes or mechanisms.

- Standardization: Methodologies and reporting standards for XAI in climate downscaling remain inconsistent, making comparisons across studies difficult. Different XAI methods can yield conflicting explanations for the same prediction, and there is a lack of consensus on benchmark metrics, hindering systematic evaluation [133].

- Beyond Post Hoc Explanations: Current XAI often provides post hoc explanations. There is a growing call to move towards building inherently interpretable models or to integrate interpretability considerations into the model design process itself, drawing lessons from how dynamical climate models are understood at a component level. This involves striving for "component-level understanding" where model behaviors can be attributed to specific architectural components or learned representations.

9.3. Representation of Extreme Events

The Challenge

- Data Imbalance: Extreme events are rare by definition, leading to their under-representation in training datasets—an issue long recognized in extreme value analysis [108]. Models optimized to minimize average error across all data points may thus prioritize fitting common, non-extreme values, effectively “smoothing over” or underestimating extremes. In precipitation downscaling, tail-aware training (e.g., quantile losses) has been used precisely to counter this tendency [135]; empirical studies also note that standard DL architectures can underestimate heavy precipitation and smooth spatial variability in extremes [44,121].

- Loss Function Bias: MSE loss, for example, penalizes large errors quadratically, which might seem beneficial for extremes. However, because extremes are infrequent, their contribution to the total loss can be small, and the model may learn to predict values closer to the mean to minimize overall MSE, thereby underpredicting the magnitude of extremes. This regression-to-the-mean behavior under quadratic criteria is well documented in hydrologic error decompositions [136]; tail-focused alternatives such as quantile (pinball) losses offer a direct mitigation [135].

- Failure to Capture Compound Extremes: Models may also struggle to capture the co-occurrence of multiple extreme conditions (e.g., concurrent heat and drought), which requires learning cross-variable dependence structures. Reviews of compound events highlight the prevalence and impacts of such co-occurrences and the difficulty for standard single-target pipelines to reproduce them [137,138]; see also evidence on changing risks of concurrent heat–drought in the U.S. [139].

Specialized Approaches for Extremes

-

Tailored Loss Functions: Using loss functions that give more weight to extreme values or are specifically designed for tail distributions. Examples include:

- −

- Weighted Loss Functions: Assigning higher weights to errors associated with extreme events (e.g., the term in Eq. 1 from the original document [140]).

- −

-

Quantile Regression: Quantile Regression (QR) offers a powerful approach by directly modeling specific quantiles of a variable’s conditional distribution, which inherently allows for a detailed focus on the distribution’s tails and thus on extreme values. For instance, Quantile Regression Neural Networks (QRNNs), as implemented by Cannon [40], provide a flexible, nonparametric, and nonlinear method. This approach avoids restrictive assumptions about the data’s underlying distribution shape, a significant advantage for complex climate variables like precipitation where parametric forms are often inadequate. A key feature of the QRNN presented is its ability to handle mixed discrete-continuous variables, such as precipitation amounts (which include zero values alongside a skewed distribution of positive amounts). This is achieved through censored quantile regression, making the model adept at representing both the occurrence and varying intensities of precipitation, including extremes.Cannon [40] notes this was the first implementation of a censored quantile regression model that is nonlinear in its parameters. Furthermore, the methodology allows for the full predictive probability density function (pdf) to be derived from the set of modeled quantiles. This enables more comprehensive probabilistic assessments, such as estimating arbitrary prediction intervals, calculating exceedance probabilities for critical thresholds (i.e., performing extreme value analysis), and evaluating risks associated with different outcomes. To enhance model robustness and mitigate overfitting, especially when data for extremes might be sparse, Cannon [40] incorporates techniques like weight penalty regularization and bootstrap aggregation (bagging). The practical relevance to downscaling is demonstrated through an application to a precipitation downscaling task, where the QRNN model showed improved skill over linear quantile regression and climatological forecasts. Importantly, the paper also suggests that QRNNs could be a "viable alternative to parametric ANN models for nonstationary extremes", a crucial consideration for climate change impact studies where the characteristics of extreme events are expected to evolve. The Quantile-Regression-Ensemble (QRE) algorithm trains members on distinct subsets of precipitation observations corresponding to specific intensity levels, showing improved accuracy for extreme precipitation [141].

- −

- Bernoulli-Gamma or Tweedie Distributions: For precipitation, which has a mixed discrete-continuous distribution (zero vs. non-zero amounts, and varying intensity), loss functions based on these distributions (e.g., minimizing Negative Log-Likelihood - NLL) can better model both occurrence and intensity, including extremes [141].

- −

- Dice Loss and Focal Loss: Explored for handling sample imbalance in heavy precipitation forecasts, with Dice Loss showing similarity to threat scores and effectively suppressing false alarms while improving hits for heavy precipitation [140].

- Generative Models (GANs and Diffusion Models): These models, by learning the underlying data distribution, can be better at generating realistic extreme events compared to deterministic regression models [32]. Diffusion models, in particular, have shown promise in capturing fine spatial features of extreme precipitation and reproducing intensity distributions more accurately than GANs or CNNs [142].

- Data Augmentation: Techniques to artificially increase the representation of extreme events in the training data, as used in the SRDRN model [14].

- Architectural Modifications: Designing model architectures or components specifically to handle extremes, such as the gradient-guided attention model for discontinuous precipitation by Xiang et al. [81] or multi-scale gradient processing in GANs. Beyond tailored loss functions and data augmentation, the architectural choices within generative frameworks and other advanced models are also pivotal for addressing the severe class imbalance inherent in extreme events and for capturing their unique characteristics. For instance, some GAN variants, such as evtGAN, integrate Extreme Value Theory to better model the tails of distributions associated with rare events. Other architectural improvements, like the use of multi-scale gradients in MSG-GAN-SD, aim for more stable training dynamics, which is a general challenge in GANs [58,123]. Diffusion models, while noted for their stable training and ability to capture fine spatial details of extremes such as precipitation [29], might inherently be better at representing multimodal distributions and capturing tail behavior due to their iterative refinement process. This could make them less prone to the averaging effects that often cause simpler architectures to underestimate extremes. Similarly, attention mechanisms in Transformers, if appropriately designed, could learn to focus on subtle precursors or localized features indicative of rare, high-impact events, thereby complementing specialized loss functions in a synergistic manner. Effectively tackling extreme events thus necessitates a holistic approach where the model architecture itself is capable of learning and representing the complex, often subtle, features that characterize these rare phenomena, rather than relying solely on adjustments to the loss function or data handling.

- Extreme Value Theory (EVT) Integration: Combining ML with EVT provides a statistical framework for modeling the tails of distributions. For instance, evtGAN [123] combines GANs with EVT to model spatial dependencies in temperature and precipitation extremes [123]. Models using Generalized Pareto Distribution (GPD) for tails can incorporate covariates from climate models to improve estimates [108].

9.4. Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)

Sources of Uncertainty

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: Represents inherent randomness or noise in the data and the process being modeled (e.g., unpredictable small-scale atmospheric fluctuations).

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Arises from limitations in model knowledge, including model structure, parameter choices, and limited training data. This uncertainty is, in principle, reducible with more data or better models.

- Scenario Uncertainty: Uncertainty in future greenhouse gas emissions and other anthropogenic forcings.

- GCM Uncertainty: Structural differences among GCMs lead to a spread in projections even for the same scenario.

- Downscaling Model Uncertainty: The statistical downscaling model itself introduces uncertainty.

UQ Approaches in ML Downscaling

-

Ensemble Methods:

- −

- Deep Ensembles: Training multiple instances of the same DL model with different random initializations (and potentially variations in training data via bootstrap sampling) and then combining their predictions to estimate both the mean and the spread (uncertainty) [79,143]. DeepESD [10] is an example of a CNN ensemble framework that quantifies inter-model spread from multiple GCM inputs and internal model variability. Deep ensembles can improve UQ, especially for future periods, by providing confidence intervals [79]. The optimal number of models in an ensemble for improving mean and UQ is often found to be around 3-6 models [79].

- −

- Multi-Model Ensembles (MMEs): Applying a downscaling model to outputs from multiple GCMs to capture inter-GCM uncertainty.

-

Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs): These models learn a probability distribution over their weights, rather than point estimates. By sampling from this posterior distribution, BNNs can provide probabilistic predictions that inherently quantify both aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty [144]. Techniques like Monte Carlo dropout are often used as a practical approximation to Bayesian inference in deep networks [144]. Bayesian AIG-Transformer and Precipitation CNN (PCNN) are examples of models incorporating these techniques for downscaling wind, and precipitation [143,145].Strengths: Provide a principled way to decompose uncertainty into aleatoric and epistemic components.Weaknesses: Can be computationally more expensive to train and sample from compared to deterministic models or simple ensembles.

- Generative Models for Probabilistic Output: GANs and Diffusion Models can, in principle, learn the conditional probability distribution and generate multiple plausible high-resolution realizations for a given low-resolution input, thus providing a form of ensemble for UQ. Diffusion models, in particular, are noted for their ability to model complex distributions effectively [32].

- Quantile Regression: As mentioned for extremes, models that predict quantiles of the distribution (e.g., Quantile Regression Neural Networks [40]) directly provide information about the range of possible outcomes.

Challenges in UQ

- Computational Cost: Probabilistic methods like BNNs and large ensembles can be computationally intensive.

- Validation of Uncertainty: Validating the reliability of uncertainty estimates, especially for future projections where ground truth is unavailable, is a significant challenge. Pseudo-reality experiments are often used for this [79].

- Communication of Uncertainty: Effectively communicating complex, multi-faceted uncertainty information to end-users and policymakers is crucial but non-trivial.

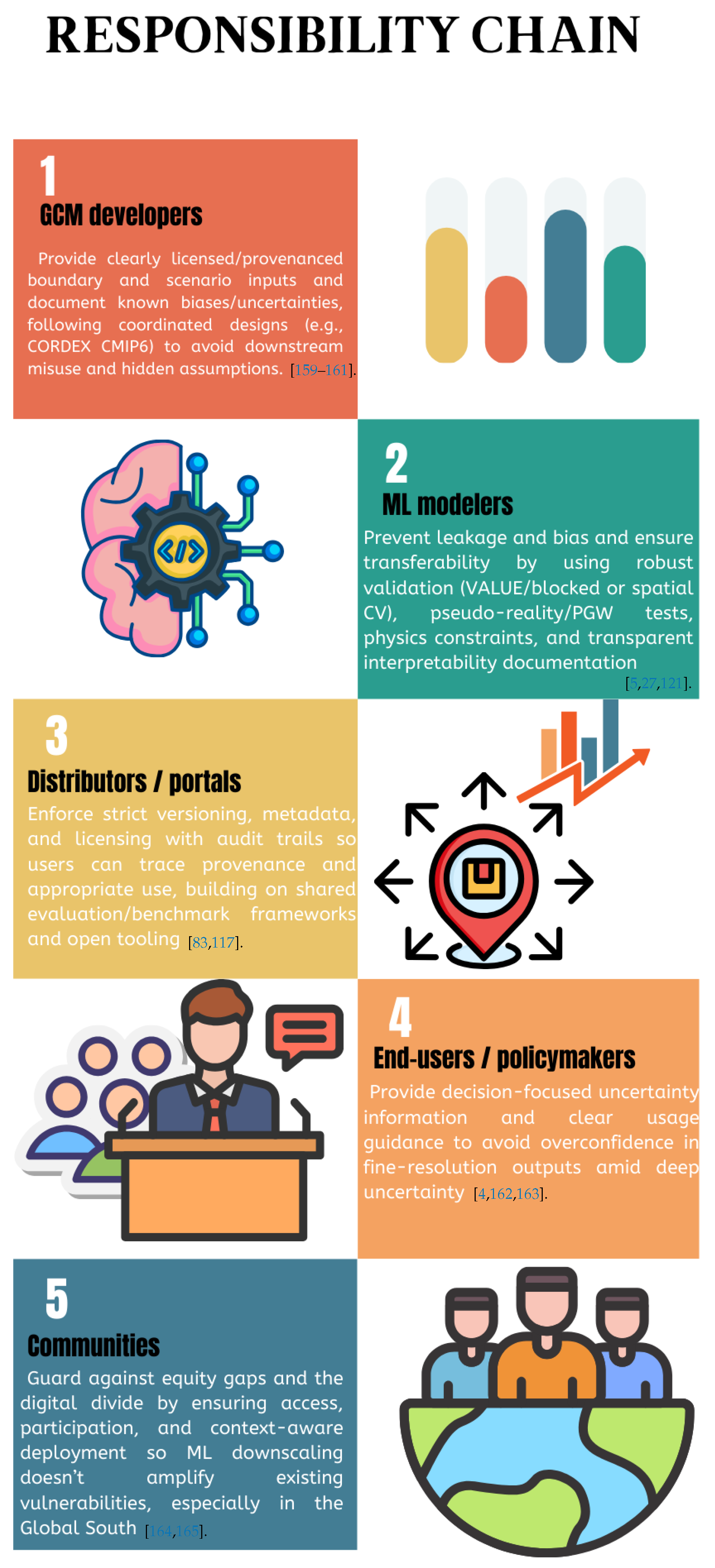

9.5. Reproducibility, Data Handling, and Methodological Rigor

-

Reproducibility: Ensuring that research findings can be independently verified is a cornerstone of scientific progress. In ML-based downscaling, this involves:

- −

- Public Code and Data: Sharing model code, training data (or clear pointers to standard datasets), and pre-trained model weights [8].

- −

- Containerization and Deterministic Environments: Using tools like Docker to create reproducible software environments and ensuring deterministic operations in model training and inference where possible [146].

- −

-

Well-Defined Train/Test Splits and Evaluation Protocols: Clearly documenting how data is split for training, validation, and testing, and using standardized evaluation protocols (like VALUE [117]) to facilitate fair comparisons across studies.Baselines. The seven-method study by Vandal et al. [1] justifies using strong linear/bias-correction baselines (BCSD, Elastic-Net, hybrid BC+ML) alongside modern DL.Spectral/structure metrics. Following Harris et al. [100] and Annau et al. [98], include power spectra/structure functions, fraction skill scores, and spatial-coherence diagnostics to detect texture hallucinations and scale mismatch.Uncertainty metrics. For probabilistic models (GAN/VAEs/diffusion), report CRPS, reliability diagrams/PIT, and quantile/interval coverage (as in [100]; [40]).Tail-aware metrics. Report quantile-oriented scores (e.g., QVSS), return-level/return-period consistency, and extreme-event FSS where relevant (cf. [124]).Explicitly include warming/OOD tests (e.g., pseudo-global-warming or future-slice validation). Rampal et al. [30] show intensity-aware losses and residual two-stage designs can improve robustness for extremes under warming.

- −

- Active Frontiers: As noted in recent papers (e.g., Quesada-Chacón et al. [8]), while reproducibility advances are being made through such efforts, consistent adoption of best practices across the community is still needed to ensure the robustness and verifiability of research findings.

-

Data Handling Issues:

- −

- Collinearity: High correlation among predictor variables can make it difficult to interpret model feature importance and can sometimes lead to unstable model training. This is addressed through feature selection techniques (e.g., PCA), regularization methods inherent in many ML models, or by careful predictor selection based on domain knowledge [132].

- −

- Feature Evaluation: Systematically evaluating the importance of different input features for downscaling performance is crucial for model understanding and simplification. XAI techniques can aid in this, but ablation studies (removing features and observing performance changes) are also common [132].

- −

- Random Initialization: The performance of DL models can be sensitive to the random initialization of model weights. Reporting results averaged over multiple runs with different initializations is good practice for robustness Quesada-Chacón et al. [8], Bano-Medina et al. [11]. In addition to seed averaging, two complementary practices help reduce sensitivity and convey uncertainty: (i) train independent replicas and aggregate them as a deep ensemble to capture variability due to different initializations González-Abad and Bano-Medina [79], Lakshminarayanan et al. [99]; and (ii) use approximate Bayesian methods such as dropout-as-Bayesian at test time to reflect parameter uncertainty Gal and Ghahramani [144].

- −

- Suppressor Variables: These are variables that, when included, improve the predictive power of other variables, even if they themselves are not strongly correlated with the predictand. Identifying and understanding their role can be complex but important for model performance [147].

-

Methodological Rigor in Evaluation:

- −

-

Beyond Standard Metrics: While RMSE is a common metric, it may not capture all relevant aspects of downscaling performance, especially for spatial patterns, temporal coherence, or extreme events. A broader suite of metrics is needed, including:

- *

- Spatial correlation, structural similarity index (SSIM) [55].

- *

- Metrics for extremes (e.g., precision, recall, critical success index for precipitation thresholds; metrics from Extreme Value Theory like GPD parameters or return levels) [8].

- *

- Metrics for distributional similarity (e.g., Earth Mover’s Distance, Kullback-Leibler divergence) [148].

- *

- Metrics for temporal coherence and spatial consistency (e.g., spectral analysis, variogram analysis, or specific metrics like Restoration Rate and Consistency Degree from TemDeep [7]). The Modified Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE) decomposes performance into correlation, bias, and variability [136,149].

- −

-

Out-of-Sample Validation: Crucially, models must be validated on data that is truly independent of the training set. This is particularly challenging for spatio-temporal climate data, which is inherently non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) due to strong spatial and temporal autocorrelation. Standard k-fold cross-validation, which randomly splits data, often violates the independence assumption. Spatial autocorrelation means that nearby data points are more similar than distant points, so random splits can lead to data leakage, where information from the validation set is implicitly present in the training set due to spatial proximity, resulting in overly optimistic performance estimates [117]. Similarly, temporal dependencies in climate time series mean that standard cross-validation can inadvertently train on future data to predict the past, which is unrealistic for prognostic applications [80]. The failure to use appropriate validation for non-IID data contributes significantly to the "performance paradox", where models appear to perform well under flawed validation schemes but fail when evaluated more rigorously or deployed on truly independent OOD data. Therefore, robust OOD validation, using specialized cross-validation techniques, is essential to assess true generalization and avoid misleading performance metrics. Such techniques include:

- *

- Spatial k-fold (or blocked) cross-validation: Data is split into spatially contiguous blocks to ensure greater independence between training and validation sets.

- *

- Leave-Location-Out (LLO) cross-validation: Entire regions or distinct geographical locations are held out for testing, providing a stringent test of spatial generalization [93].

- *

- Buffered cross-validation: A buffer zone is created around test points, and data within this buffer is excluded from training to minimize leakage due to spatial proximity [150].

- *

- Temporal (blocked) cross-validation / Forward Chaining: For time-series aspects, data is split chronologically, ensuring the model is always trained on past data and tested on future data, mimicking operational forecasting. Beyond these, ’warm-test’ periods (pseudo-future), such as those created through pseudo-global warming (PGW) experiments, are also used for extrapolation assessment [151]. Adopting these robust validation strategies is a prerequisite for accurately assessing generalization and building trust in reported model performance

9.5.1. Challenges in Benchmarking and Inter-comparison

10. Future Trajectories: Grand Challenges and Open Questions

10.1. Grand Challenge 1: Overcoming Non-Stationarity

- Foundation Models: Large, pretrained backbones learned from massive, diverse earth-system data (e.g., multiple GCMs or reanalyses) that provide broad, reusable priors; usable zero-/few-shot or with fine-tuning [23].

- Domain Adaptation and Transfer Learning: Methods to adapt models from a source to a target distribution like (historical→future, reanalysis→GCM, region A→B), including fine-tuning FMs or smaller models and explicit shift-handling techniques [28].

- Rigorous OOD Testing: Systematically using Pseudo-Global Warming (PGW) experiments and holding out entire GCMs or future time periods for validation to stress-test and quantify extrapolation capabilities [30].

- How can we formally verify that a model has learned a causal physical process rather than a spurious shortcut?

- What are the theoretical limits of generalization for a given model architecture and training data diversity?

- Can online learning systems be developed to allow models to adapt continuously as the climate evolves, mitigating concept drift in near-real-time applications?

10.2. Grand Challenge 2: Achieving Verifiable Physical Consistency

- Hybrid Dynamical-Statistical Models: Frameworks like dynamical-generative downscaling leverage a physical model to provide a consistent foundation, which an ML model then refines. This approach strategically outsources the enforcement of complex physics to a trusted dynamical core [9].

- How can we design computationally tractable physical loss terms for complex, non-differentiable processes like cloud microphysics or radiative transfer?

- What is the optimal trade-off between the flexibility of soft constraints and the guarantees of hard constraints for multi-variable downscaling?

- Can we develop methods to automatically discover relevant physical constraints from data, rather than relying solely on pre-defined equations?

10.3. Grand Challenge 3: Reliable and Interpretable Uncertainty Quantification (UQ)