Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

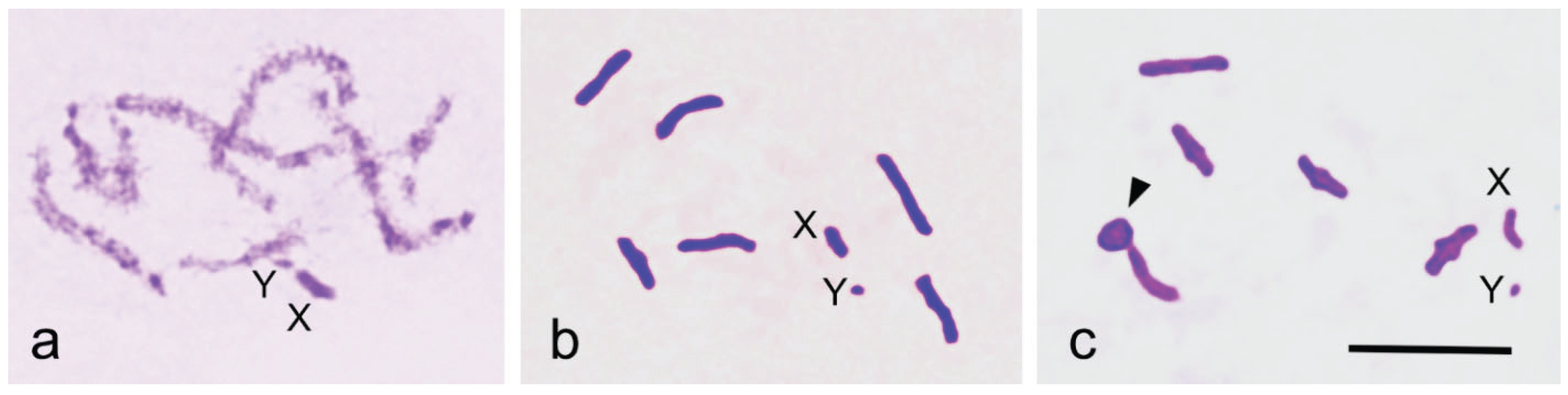

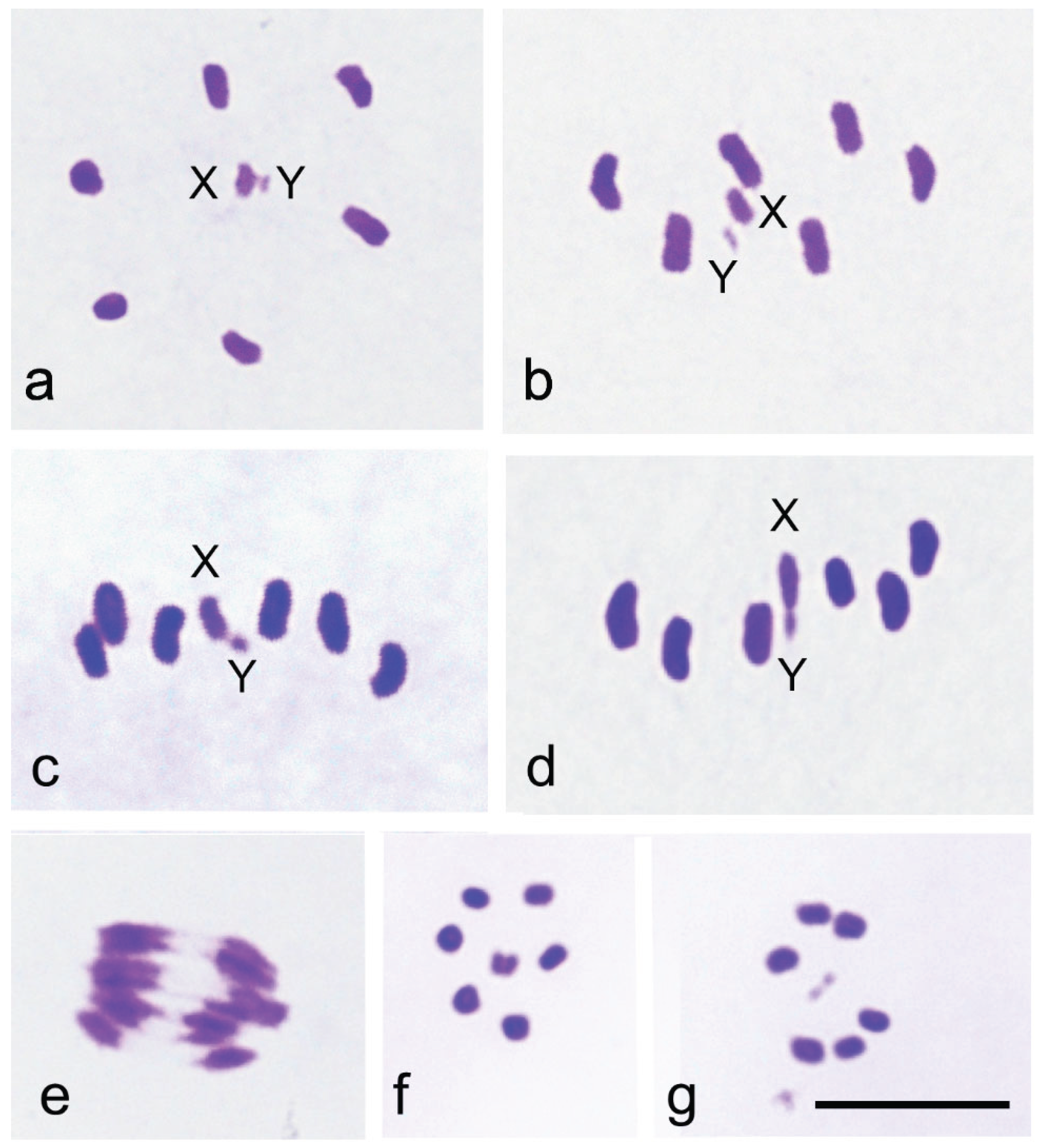

The family Sisyridae, the Spongilla-flies, is notable for its phylogenetic position as a basal group within Neuroptera. Using the improved Schiff-Giemsa method, we analysed the behaviour of the sex chromosomes X and Y during male meiosis in Sisyra nigra (Retzius 1738). The diploid chromosome number in males was 2n = 12 + XY. In pachytene, X and Y chromosomes appeared positively heteropycnotic and loosely paired. In early diakinetic nuclei, autosomal bivalents typically exhibited one distally located chiasma, although bivalents with two chiasmata were occasionally observed. The X and Y univalents were isopycnotic with the autosomes, with the X considerably larger than the Y. During the first meiotic division, metaphase plates were radial, with autosomal bivalents forming a ring and X and Y univalents positioned centrally, well separated from each other. In metaphase cells, X and Y were located at the equator, strongly indicating their amphitelic orientation. However, they later formed a pseudobivalent from which X and Y segregated simultaneously with autosomal half bivalents at anaphase I. This achiasmatic segregation mechanism, touch-and-go pairing, has now been observed for the first time in a species carrying chromosomes with a localised centromere. At the second metaphase, two cell types were observed: one with the X chromosome and the other with the Y chromosome. The behaviour of the sex chromosomes in S. nigra is notably different from that in other Neuroptera, where sex chromosomes exhibit syntelic orientation and distance pairing at metaphase I. The unusual mechanism of sex chromosome segregation in the family Sisyridae aligns well with molecular phylogenetic findings concerning the family’s basal position within the order Neuroptera.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insects

2.2. Slide Preparation

2.3. Slide Staining

2.2. Documentation

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Withycombe, C.L. Some Aspects of the Biology and Morphology of the Neuroptera. With Special Reference to the Immature Stages and Their Possible Phylogenetic Significance. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 1925, 72, 303–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Winterton, S.L.; Yang, D. The First Mitochondrial Genomes of Antlion (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) and Split-Footed Lacewing (Neuroptera: Nymphidae), with Phylogenetic Implications of Myrmeleontiformia. Int J Biol Sci 2014, 10, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, J. The Mitochondrial Genome of Gatzara Jezoensis (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) and Phylogenetic Analysis of Neuroptera. Biochem Syst Ecol 2017, 71, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Li, X.X.; Zhai, Q.; Bozdoğan, H.; Yin, X.M. The Mitochondrial Genomes of Neuropteridan Insects and Implications for the Phylogeny of Neuroptera. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilikopoulos, A.; Misof, B.; Meusemann, K.; Lieberz, D.; Flouri, T.; Beutel, R.G.; Niehuis, O.; Wappler, T.; Rust, J.; Peters, R.S.; et al. An Integrative Phylogenomic Approach to Elucidate the Evolutionary History and Divergence Times of Neuropterida (Insecta: Holometabola). BMC Evol Biol 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Garzón-Orduña, I.J.; Winterton, S.L.; Yan, Y.; Aspöck, U.; Aspöck, H.; Yang, D. Mitochondrial Phylogenomics Illuminates the Evolutionary History of Neuropterida. Cladistics 2017, 33, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.S.; Winterton, S.L.; Breitkreuz, L.C.V. Phylogeny and Evolution of Neuropterida: Where Have Wings of Lace Taken Us? Annu Rev Entomol 2018, 63, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarkin, V.N.; Perkovsky, E.E. An Interesting New Species of Sisyridae (Neuroptera) from the Upper Cretaceous Taimyr Amber. Cretac Res 2016, 63, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintala, Teemu.; Kumpulainen, Tomi.; Ahlroth, Petri. Suomen Verkkosiipiset; Hyönteistarvike TIBIALE Oy, 2014; ISBN 9789526754451.

- Hughes-Schrader, S. Segregational Mechanisms of Sex Chromosomes in Spongilla-Flies (Neuroptera: Sisyridae). Chromosoma 1975, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naville, A.; de Beaumont, J. Recherches Sur Les Chromosomes Des Névroptères. Arch. Anat. Microsc. Morph. Exp. 1933, 29, 1–173. [Google Scholar]

- Naville, A.; De Beaumont, J. Recherches Sur Les Chromosomes Des Névroptères. Archives d’Anatomie Microscopique 1936, 32, 271–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Schrader, S. Segregational Mechanisms of Sex Chromosomes in Megaloptera (Neuropteroidea). Chromosoma 1980, 81, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Schrader, S. Distance Segregation and Compound Sex Chromosomes in Mantispids (Neuroptera: Mantispidae). Chromosoma 1969, 27, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S. The Nonsignificance of Distance Pairing for the Regular Segregation of the Sex Chromosomes in Hemerobius Marginatus Male. (Hemerobidae, Neuroptera). Hereditas 1986, 105, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, V.G.; Krivokhatsky, V.N.; Khabiev, G.A. Chromosome Numbers in Antlions (Myrmeleontidae) and Owlflies (Ascalaphidae) (Insecta, Neuroptera). Zookeys 2015, 538, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, V.G.; Khabiev, G.N.; Anokhin, B.A. Cytogenetic Study on Antlions (Neuroptera, Myrmeleontidae): First Data on Telomere Structure and RDNA Location. Comp Cytogenet 2016, 10, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, G.R.; Crowley, L.M.; McCulloch, J. The Genome Sequence of the Black Spongefly, Sisyra Nigra (Retzius, 1783). Wellcome Open Res 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCulloch, J.; Crowley, L.M. The Genome Sequence of a Spongefly, Sisyra Terminalis (Curtis, 1854). Wellcome Open Res 2024, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Nokkala, S. Chromosomes and Their Meiotic Behavior in Two Families of the Primitive Infraorder Dipsocoromorpha (Heteroptera). Hereditas 1996, 125, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.B. The Cell in Development and Heredity; 3rd ed.; McMillan: New York, 1925.

- Nokkala, S. The Mechanisms behind the Regular Segregation of the M-Chromosomes in Coreus Marginatus L. (Coreidae, Hemiptera). Hereditas 1986, 105, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozeva, S.; Nokkala, S. Chromosome Numbers, Sex Determining Systems, and Patterns of the C-Heterochromatin Distribution in 13 Species of Lace Bugs (Heteroptera, Tingidae). Folia Biologica (Krakow) 2001, 49, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ueshima, Norihiro. Animal Cytogenetics 3. Insecta 5. Hemiptera II : Heteroptera; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin-Stuttgart, 1979; ISBN 344326008X.

- Smith, S.G.; Virkki, Niilo. Animal Cytogenetics 3. Insecta 5: Coleoptera; Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin-Stuttgart, 1978; ISBN 3443260071.

- Virkki, N. Sex Chromosomes and Karyotypes of the Alticidae (Coleoptera). Hereditas 1970, 64, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkki, N. Proximal vs. Distal Collochores in Coleopteran Chromosomes. Hereditas 1989, 110, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, H.; Dietz, R.; RÖbbelen, C. Die Spermatocytenteilungen Der Tipuliden. Chromosoma 1961, 12, 116–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuge, H. Morphological Studies on the Structure of Univalent Sex Chromosomes during Anaphase Movement in Spermatocytes of the Crane Fly Pales Ferruginea. Chromosoma 1972, 39, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuge, H. The Three-Dimensional Architecture of Chromosome Fibres in the Crane Fly. Chromosoma 1985, 91, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuge, H. The Arrangement of Microtubules and the Attachment of Chromosomes to the Spindle during Anaphase in Tipulid Spermatocytes. Chromosoma 1974, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuge, H.; Bastmeyer, M.; Steffen, W. A Model for Chromosome Movement Based on Lateral Interaction of Spindle Microtubules. J Theor Biol 1985, 115, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S.; Kuznetsova, V.; Maryańska-Nadachowska, A. Achiasmate Segregation of a B Chromosome from the X Chromosome in Two Species of Psyllids (Psylloidea, Hemiptera). Genetica 2000, 108, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, E.; Halkka, O. The Mode of Meiosis in the Psyllina. Chromosoma 1963, 14, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, V.G.; Nokkala, S.; Maryanska-Nadachowska, A. Karyotypes, Sex Chromosome Systems and Male Meiosis in FInnish Psyllids (Homoptera; Psylloidea). Folia Biologica (Krakow) 1997, 45, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Maryańska-Nadachowska, A.; Taylor, G.S.; Kuznetsova, V.G. Meiotic Karyotypes and Structure of Testes in Males of 17 Species of Psyllidae: Spondyliaspidinae (Hemiptera: Psylloidea) from Australia. Aust J Entomol 2001, 40, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S.; Nokkala, C. Interaction of B Chromosomes with A or B Chromosomes in Segregation in Insects. Cytogenet Genome Res 2004, 106, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S.; Grozeva, S.; Kuznetsova, V.; Maryanska-Nadachowska, A. The Origin of the Achiasmatic XY Sex Chromosome System in Cacopsylla Peregrina (Frst.) (Psylloidea, Homoptera). Genetica 2003, 119, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo Carvalho, A.; Koerich, L.B.; Clark, A.G. Origin and Evolution of Y Chromosomes: Drosophila Tales. Trends in Genetics 2009, 25, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Schrader, S. Segregational Mechanisms of Sex Chromosomes in Spongilla-Flies (Neuroptera: Sisyridae). Chromosoma 1975, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S. The Meiotic Behaviour of B-Chromosomes and Their Effect on the Segregation of Sex Chromosomes in Males of Hemerobius Marginatus L. (Hemerobidae, Neuroptera). Hereditas 1986, 105, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokkala, S. The Mechanisms behind the Regular Segregation of Autosomal Univalents in Calocoris Quadripunctatus (Vil.) (Miridae, Hemiptera). Hereditas 1986, 105, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).