1. Introduction

Facial Expression Recognition (FER) plays a fundamental role in affective computing, human–computer interaction, and behavioral analysis. By decoding facial muscle movements into discrete or continuous emotional states, FER enables machines to perceive and respond to human affective cues in a socially intelligent manner. Despite extensive progress in recent years, robust FER under uncontrolled conditions—such as diverse illumination, head pose, occlusion, and cultural variation—remains a persistent challenge. These variations often cause domain shifts and feature inconsistencies, severely degrading recognition performance in real-world applications [

1,

2].

Traditional CNN-based methods [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] rely on local convolutional operations, which effectively capture low-level facial details but struggle to model long-range dependencies and global emotion semantics. Recent Transformer architectures, such as the Vision Transformer (ViT) [

8], introduce global self-attention mechanisms that provide powerful context modeling ability for FER. However, pure Transformer models often overlook fine-grained structural information and frequency-related cues that are crucial for distinguishing subtle or compound expressions (e.g.,

fear vs.

surprise). Moreover, most existing approaches focus on single-domain representations and lack adaptive strategies to integrate spatial, semantic, and spectral features into a unified feature space. This deficiency also limits their robustness when transferring across datasets or cultural domains, which is essential for practical affective computing systems.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a unified multi-domain feature enhancement and fusion framework for robust facial expression recognition and cross-domain generalization. The framework employs a ViT-based encoder for global semantic extraction and introduces three complementary branches—channel, spatial, and frequency—to jointly capture semantic, structural, and spectral cues. Furthermore, an adaptive Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module is developed to align and integrate heterogeneous representations across domains, leading to consistent and illumination-robust emotion understanding. In addition to within-dataset evaluation, we perform extensive cross-domain validation experiments among KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB to assess the transferability and generalization of the proposed method.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

A unified multi-domain FER framework. We design an end-to-end framework that combines ViT-based global context modeling with domain-specific feature extraction in the channel, spatial, and frequency domains, enabling complementary and robust representation learning.

A cross-domain feature enhancement and fusion module (CDFEF). We propose an adaptive multi-scale fusion mechanism that effectively integrates heterogeneous features from multiple domains, achieving semantic alignment and illumination robustness for expression understanding.

Comprehensive experiments with cross-domain validation. Extensive experiments on KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB demonstrate that our method outperforms state-of-the-art CNN-, Transformer-, and ensemble-based models in both intra-domain accuracy and cross-domain generalization, validating the effectiveness of the proposed framework under diverse conditions.

By unifying multi-domain feature learning, adaptive cross-domain fusion, and systematic cross-dataset validation, the proposed method bridges the gap between global semantic abstraction and fine-grained local discrimination, providing a robust and generalizable solution for real-world facial expression recognition.

2. Related Work

2.1. Foundations and Datasets for Facial Expression Recognition

Facial Expression Recognition (FER) originates from the basic emotion theory proposed by Ekman and Friesen, which suggests that human facial expressions convey universal emotional states across cultures [

9]. Based on this theoretical foundation, several benchmark datasets have been developed, such as CK+ [

10] and KDEF [

11], which were captured under controlled laboratory settings and provide standardized, high-quality samples for model training and validation. With the advent of deep learning, research focus has shifted toward more challenging “in-the-wild’’ datasets, such as FER2013 [

12] and RAF-DB [

13], which include variations in illumination, pose, occlusion, and ethnicity. More recently, the ABAW challenge has expanded FER toward multi-task affective computing, integrating categorical recognition with valence–arousal estimation, action unit detection, and emotional intensity prediction [

14]. Comprehensive surveys have reviewed the evolution of deep FER, identifying key challenges such as label uncertainty, identity bias, occlusion sensitivity, and domain generalization limitations [

1,

2]. Moreover, region-specific datasets such as the East Asian Facial Expression Database [

15] highlight cultural and demographic variations that further motivate research on cross-domain modeling and generalization.

2.2. Learning with Noisy and Ambiguous Labels

Facial expression data are inherently ambiguous due to subtle emotional differences and subjective labeling. Barsoum

et al. introduced the idea of training deep networks with crowd-sourced label distributions to better capture annotator disagreement and uncertainty [

16]. Li

et al. proposed reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning to enhance model robustness under noisy labeling conditions and improve discriminative representation in the wild [

17,

18]. Inspired by these studies, our work focuses on robust representation learning at the feature level: by designing complementary branches in channel, spatial, and frequency domains and integrating them via adaptive cross-domain fusion, the model can effectively mitigate ambiguity arising from label noise and subjective variability.

2.3. From CNNs to Transformers and Ensemble Models

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have long served as the backbone for FER tasks, with representative architectures including AlexNet [

3], VGG [

4], ResNet [

5], DenseNet [

6], and EfficientNet [

7]. Subsequent works improved these backbones through architectural refinements such as attention mechanisms for emphasizing emotion-relevant regions [

19,

20], pose-guided face alignment for geometric consistency [

21], and multi-task learning frameworks for joint expression and action unit modeling [

22]. Temporal and multi-scale hybrid models (e.g., CNN–LSTM combinations) [

23], dual-branch or integrated CNNs [

24,

25], and feature optimization techniques [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31] further enhanced model expressiveness and stability. With the emergence of Transformer architectures, the Vision Transformer (ViT) [

8] demonstrated strong global context modeling capabilities and has been increasingly applied to FER. Recent transformer-based and ensemble approaches such as Gimefive [

32] and the Attention-Enhanced Ensemble [

33] have improved interpretability and robustness through multi-head attention and model fusion. In addition, a variety of Vision Transformer-based architectures have been specifically tailored for FER, including self-supervised ViT models, attentive pooling mechanisms, hybrid or hierarchical transformer designs, and unified cross-domain FER benchmarks with adversarial graph learning [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. These ViT-based methods further confirm the effectiveness of transformer backbones for modeling global context in facial expressions, but they typically focus on a single feature domain and lack explicit multi-domain enhancement and fusion.

Similar ideas of attention-based multi-domain modeling have also been successfully applied to non-stationary spatio-temporal financial systems using graph attention networks [

39], which further supports the effectiveness of attention-driven architectures under distribution shifts. In parallel, deep learning–based multi-scale and lightweight perception models (e.g., hybrid CNN–Transformer backbones and optimized YOLO variants) have been extensively explored in image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping, crop monitoring, and agricultural robotics, including sensor-to-insight pipelines for plant traits, full-chain potato production analysis, real-time cotton boll and flower recognition, tomato detection and quality assessment, blueberry maturity estimation, and intelligent weeding robots [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. These cross-domain studies collectively indicate that robust feature extraction, multi-scale modeling, and generalization across acquisition conditions are key requirements not only in FER but also in other safety-critical visual perception tasks.

Following this trend, our method adopts the ViT-B encoder to extract global semantic features while introducing multi-branch local enhancement modules to recover fine-grained spatial and frequency-domain cues that Transformers typically overlook.

2.4. Robustness and Cross-Domain Generalization

Enhancing robustness and cross-domain generalization remains a critical research direction in FER. Umer

et al. analyzed the trade-off between data augmentation and deep feature stability, emphasizing that excessive augmentation may distort underlying feature distributions [

46]. Architectural improvements such as anti-aliasing and shift-invariant convolutional designs have been proven effective in mitigating sampling bias and spatial instability [

47,

48], while knowledge-transferred fine-tuning with anti-aliasing further enhances performance under limited data conditions [

49]. Furthermore, the widespread use of facial masks during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted FER’s vulnerability to occlusion and domain discrepancies [

50]. These findings collectively motivate our introduction of frequency-domain modeling to capture illumination- and texture-robust features, and our cross-domain fusion module to align and integrate heterogeneous cues across domains.

Beyond generic robustness considerations, several recent studies have explicitly focused on handling occlusions, head-pose variations, and fine-grained spectral cues in FER. Liu et al. proposed a patch attention convolutional vision transformer that selectively emphasizes informative facial patches for FER under occlusion [

51]. Sun et al. combined appearance features with geometric landmarks in a transformer framework to improve recognition in the wild [

52]. Liang et al. designed a convolution–transformer dual-branch network to jointly address head-pose changes and occlusions [

53]. Wang et al. introduced region attention networks that focus on discriminative local facial regions, achieving strong robustness to pose variations and occlusions [

54]. Tang et al. further exploited frequency-domain representations through a frequency neural network for FER, demonstrating that frequency cues and subtle texture variations are critical under illumination changes and complex real-world conditions [

55]. These works collectively support our design choice of combining spatial, channel, and frequency-domain modeling to enhance robustness against occlusion, pose variation, and domain shifts.

These findings collectively motivate our introduction of frequency-domain modeling to capture illumination- and texture-robust features, and our cross-domain fusion module to align and integrate heterogeneous cues across domains. Beyond intra-dataset robustness, cross-domain facial expression recognition has been systematically studied using unified evaluation benchmarks and adversarial graph-based representation learning [

38], highlighting that substantial distribution shifts exist among different FER datasets and motivating the need for architectures with stronger cross-domain generalization.

In parallel, robustness and conditional fault tolerance have also been extensively investigated in interconnection networks and Cayley-graph-based topologies [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62], highlighting the importance of structural reliability when designing systems that must remain functional under perturbations.

Limitations of Existing Methods and Motivation. Despite considerable progress, several challenges persist in current FER research: (1) most CNN- or Transformer-based models focus on a single feature domain and neglect the complementary relationships between spatial, channel, and frequency representations; (2) inconsistent feature distributions across domains and varying expression intensities lead to performance degradation in unconstrained scenarios; and (3) current feature fusion strategies largely rely on static concatenation or simple weighting, lacking adaptive enhancement mechanisms. To address these issues, we propose a multi-domain feature enhancement and fusion framework that jointly models channel–spatial–frequency interactions and achieves adaptive cross-domain integration, thereby improving both discriminative accuracy and generalization under diverse illumination, identity, and expression conditions.

2.5. methodology

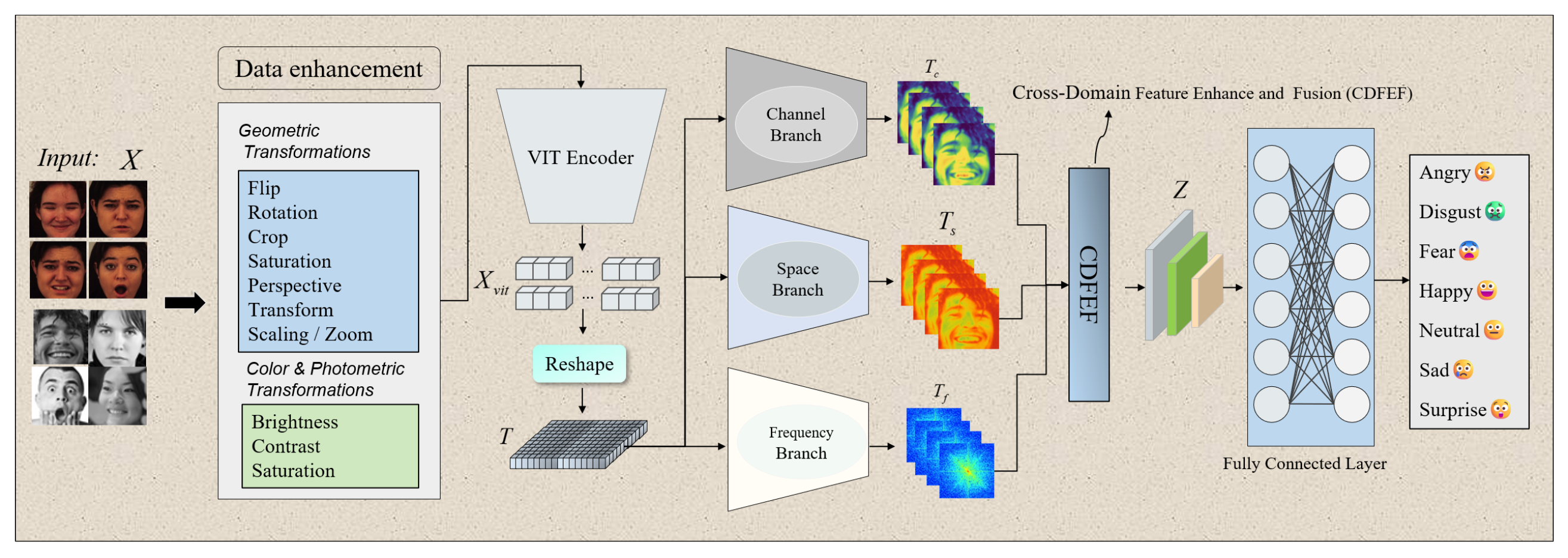

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the proposed framework aims to achieve robust facial expression recognition through multi-domain feature enhancement and adaptive fusion. The model mainly consists of five key modules: (1) a

Data Enhancement Module for geometric and photometric augmentation to improve data diversity and robustness; (2) a

Vision Transformer (ViT) Encoder that extracts high-level global representations from enhanced images; (3) three complementary feature extraction branches, including the

Channel Branch,

Space Branch, and

Frequency Branch, which respectively emphasize inter-channel relationships, spatial saliency, and frequency-domain textures; (4) a

Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module that adaptively integrates multi-domain features into a unified representation; and (5) a

Fully Connected Classification Layer that predicts seven discrete emotion categories:

Angry,

Disgust,

Fear,

Happy,

Neutral,

Sad, and

Surprise.

This unified multi-domain design enables the model to combine geometric, photometric, and frequency cues, thereby improving its discriminative capability and generalization under varying facial expressions and illumination conditions.

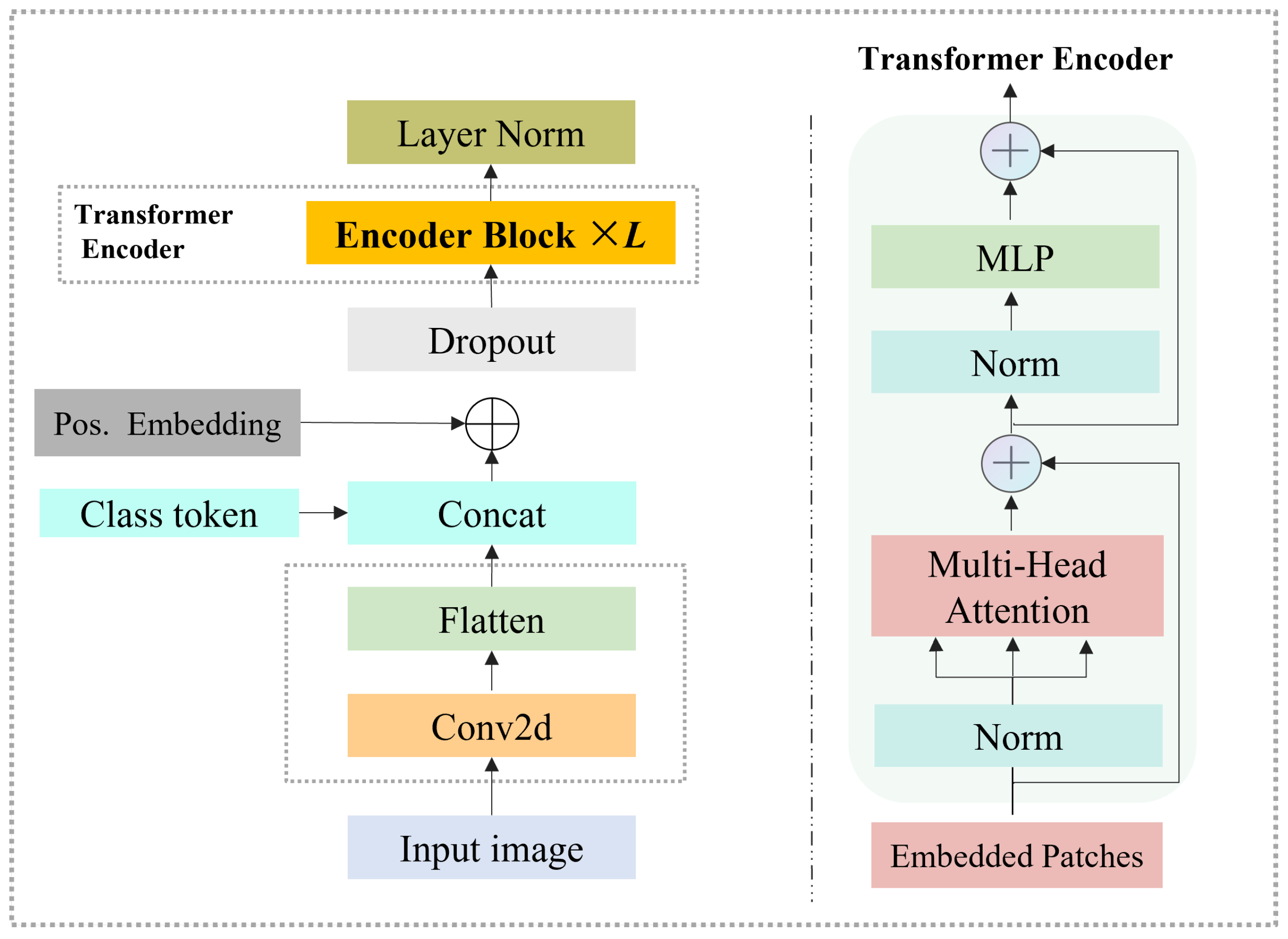

2.6. Vision Transformer (ViT) Encoder

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder is employed to extract global contextual representations from input facial images and generate high-level semantic embeddings. Unlike convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that depend on local receptive fields, ViT leverages self-attention to model long-range dependencies among image patches, effectively capturing both holistic consistency and subtle variations in facial expressions.

Given an input image

, it is divided into non-overlapping patches of size

. The number of patches is calculated as:

where

N denotes the total number of patches. Each patch is linearly projected into a feature embedding of dimension

D via a convolutional layer:

To preserve spatial order and global identity, a learnable class token

and positional embedding

are added to the input sequence:

where

denotes concatenation.

The sequence

is then processed by

L stacked Transformer encoder blocks. Each block consists of a Multi-Head Self-Attention (MSA) module and a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), both with residual connections and layer normalization. The

l-th block is formulated as:

where

denotes layer normalization, ensuring feature stability and improved gradient flow.

Within the MSA operation, each token is projected into query, key, and value matrices:

where

are learnable parameters. The attention weights are computed as:

After passing through all encoder blocks, the final output of the ViT encoder is given by:

where the first token (

class token) represents the global semantic summary of the image, while the remaining tokens encode localized spatial features. The output

serves as the shared representation for subsequent multi-branch feature extraction.

In this study, we adopt the

ViT-B variant of the Vision Transformer [

8], which provides a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and representation capability for facial expression analysis.

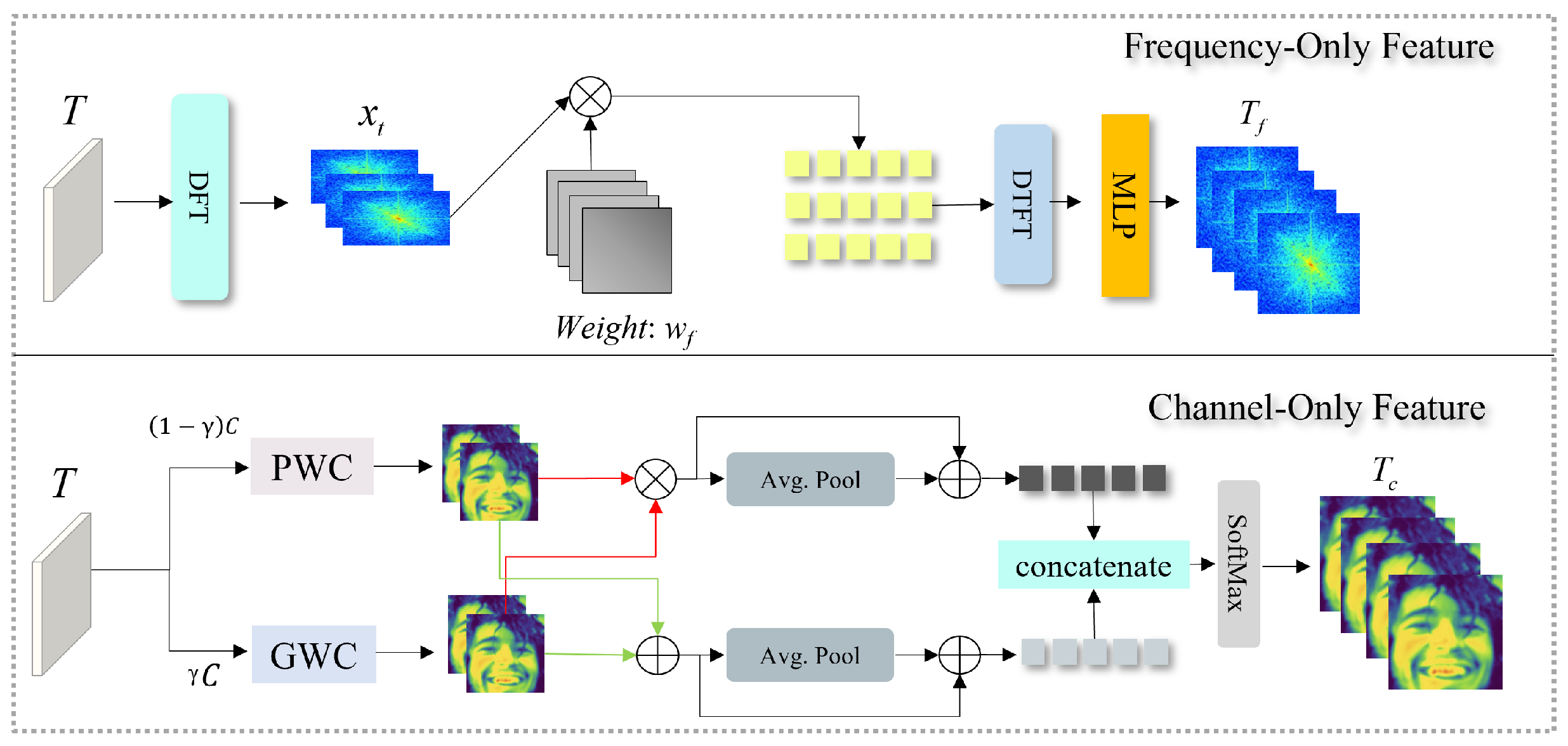

2.7. Multi-Branch Feature Extraction Module

Facial expressions exhibit rich variations across spatial, spectral, and semantic dimensions. While the ViT encoder provides a global context representation, it tends to lose fine-grained emotional cues such as micro-expressions, edge textures, and local shading patterns that are critical for differentiating subtle emotions (e.g., fear vs. surprise). To address this, we design a multi-branch feature extraction module that decomposes the latent feature into multiple complementary subspaces, each responsible for encoding a distinct type of expressive information.

As shown in

Figure 3, this module consists of two main branches — a

Channel Branch and a

Frequency Branch. The Channel Branch focuses on semantic inter-channel dependencies, capturing correlations among activation maps that correspond to emotional muscle regions (such as the eyebrows, lips, and nasolabial folds). In contrast, the Frequency Branch extracts spectral and structural information in the frequency domain, emphasizing edge contours, wrinkle density, and contrast changes that are often discriminative under varying illumination and expression intensity. Together, these branches yield domain-specific representations

and

, which are later fused in the Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module.

2.7.1. Channel Branch

The Channel Branch is designed to enhance inter-channel relationships and reduce redundancy among features derived from different receptive fields. Given the input feature map

T, we employ two complementary convolutions: a

Point-Wise Convolution (PWC) for global aggregation and a

Group-Wise Convolution (GWC) for local specialization. These two operations ensure that the model can simultaneously capture both cross-channel global statistics and localized emotional activations. The process can be mathematically formulated as:

where

controls the proportion between local and global channel features, determining how the feature capacity is distributed between the PWC and GWC pathways. As discussed in Table 5, the model achieves its most stable and accurate performance when

, indicating that a balanced allocation between global aggregation and local specialization yields optimal cross-channel feature representation.

The outputs from the two paths are aggregated through a residual fusion mechanism and average pooling:

which summarizes the channel activation strength across spatial positions. Subsequently, the pooled responses are concatenated and normalized by a Softmax operation to generate the final channel-wise attention mask:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. The resulting feature

adaptively emphasizes emotion-sensitive channels (e.g., regions activated by smile lines or eyebrow raises) and suppresses irrelevant or redundant activations, enabling the network to focus on semantically meaningful emotional cues.

2.7.2. Frequency Branch

Facial expressions are often characterized by localized structural changes such as wrinkles, muscle deformations, and lighting reflections. While spatial features describe pixel-level arrangements, frequency-domain representations provide complementary insights into how expression intensity modulates texture energy and periodicity. To capture these cues, we introduce the

Frequency Branch, which transforms

T into the frequency domain using a 2D Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT):

Each frequency coefficient in

represents an oscillation pattern corresponding to specific textural variations (e.g., high frequencies for edges and wrinkles, low frequencies for smooth shading). To adaptively control the contribution of different spectral components, a learnable weighting mask

is applied:

The reweighted spectral representation is then processed by an inverse DFT (IDFT) and a lightweight Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to reconstruct frequency-enhanced spatial features:

The output thus encodes frequency-aware information, preserving the structural fidelity of fine-grained expressions while maintaining robustness to lighting and contrast shifts. Specifically, low-frequency bands capture smooth global illumination variations, whereas high-frequency bands capture sharp structural boundaries — both essential for emotion classification under real-world conditions.

By combining and , this module achieves a complementary integration of semantic and structural cues. Such multi-domain representations enable the model to generalize across varying facial morphologies, occlusions, and expression intensities — key challenges in robust facial expression recognition.

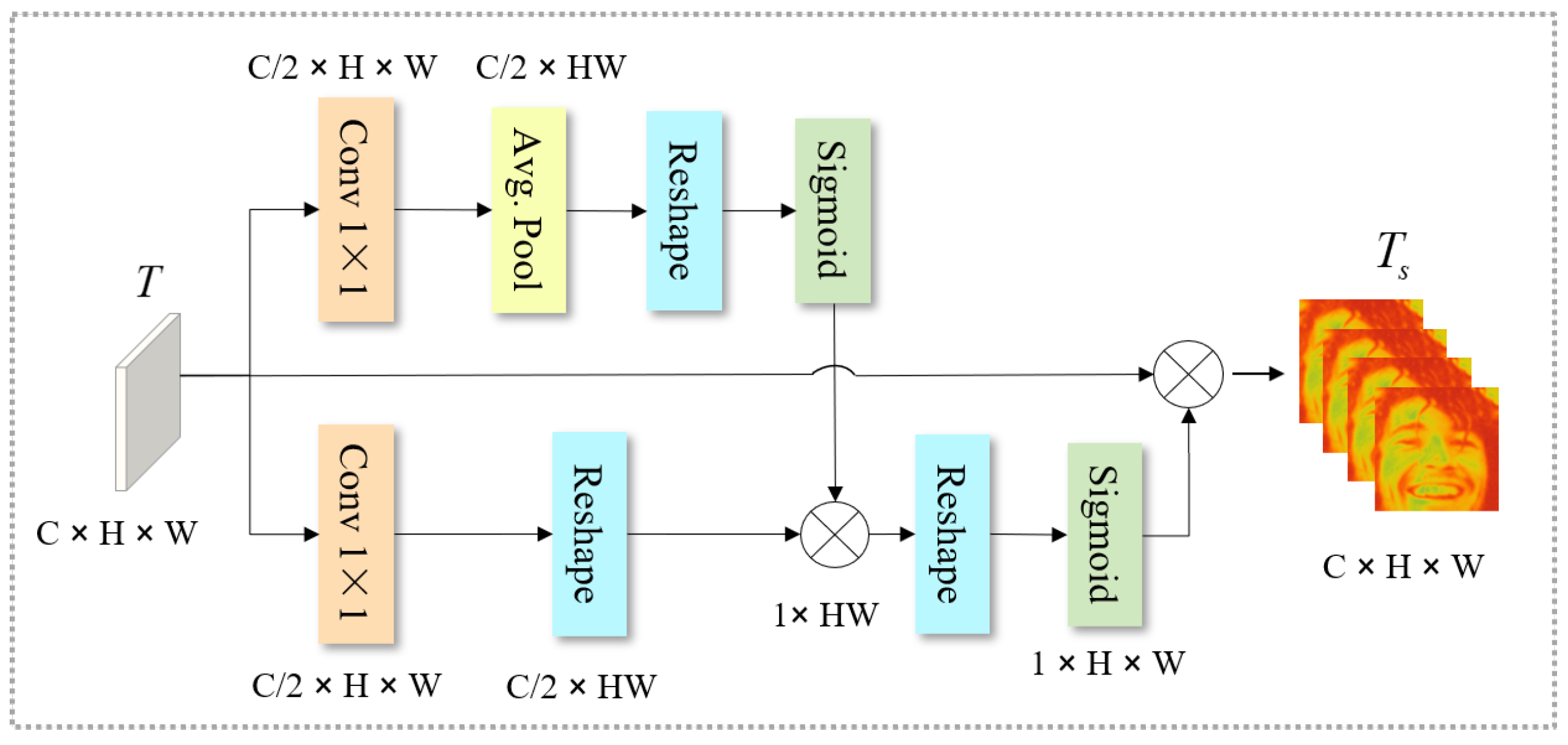

2.7.3. Space Branch

While the Channel and Frequency branches focus on inter-channel dependencies and spectral texture cues, the Space Branch is designed to highlight emotion-relevant spatial regions on the face, such as the eyes, eyebrows, and mouth corners, which play a dominant role in visual affect perception. This branch enhances spatially discriminative regions and suppresses background or identity-irrelevant areas by learning a pixel-wise attention map.

Given the encoded feature map

, two parallel

convolutional layers are first applied to reduce the channel dimension to

and generate two intermediate representations:

The first feature branch (

) undergoes global spatial pooling to capture overall intensity statistics, followed by reshaping and activation:

where

denotes the sigmoid function. Here,

serves as a coarse spatial attention prior that encodes global emotional saliency distribution across facial regions.

Meanwhile, the second path (

) preserves fine-grained spatial details and is reshaped directly to align with the attention prior. The attention map is then refined through an element-wise interaction between the two paths:

where

represents the learned spatial weighting mask that adaptively adjusts the contribution of each pixel position.

Finally, this attention mask is broadcast and multiplied with the original feature map

T to obtain the spatially enhanced feature:

where

emphasizes discriminative facial regions while suppressing irrelevant background pixels.

This design allows the model to automatically focus on regions of high expressive significance (e.g., eyebrow raises, mouth openings, or eye contractions), which are crucial for distinguishing between visually similar emotions such as fear and surprise. Moreover, by leveraging both global (via pooling) and local (via convolutional response) spatial cues, the Space Branch ensures stable performance under pose and lighting variations.

Figure 4.

Structure of the Space Branch. Two parallel convolutional paths generate global and local spatial responses, which are fused to form a spatial attention map that highlights emotion-relevant regions. The enhanced feature captures pixel-level spatial saliency crucial for facial expression recognition.

Figure 4.

Structure of the Space Branch. Two parallel convolutional paths generate global and local spatial responses, which are fused to form a spatial attention map that highlights emotion-relevant regions. The enhanced feature captures pixel-level spatial saliency crucial for facial expression recognition.

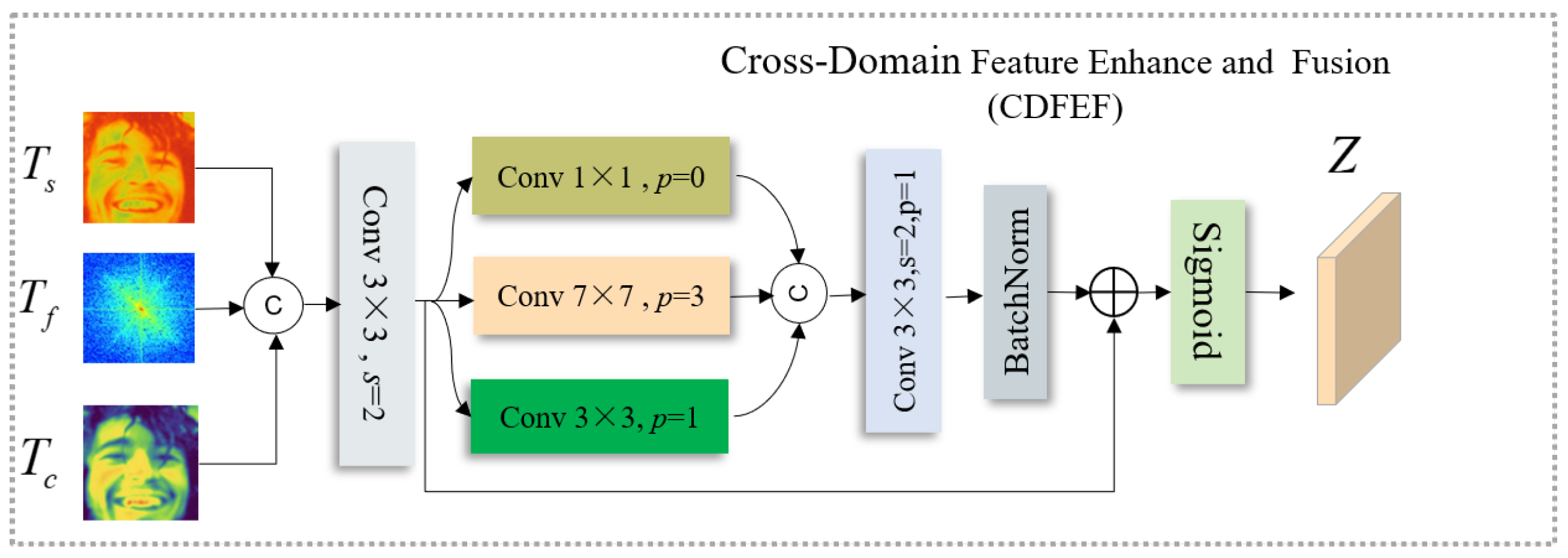

2.8. Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF)

Although the Channel, Space, and Frequency branches capture complementary aspects of emotional features, their representations reside in distinct domains and exhibit heterogeneous distributions. To achieve semantic alignment and enhance inter-domain complementarity, we propose the

Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module. As shown in

Figure 5, this module adaptively integrates spatial, spectral, and semantic cues into a unified representation

Z, which serves as the foundation for the final emotion classification layer.

Let

denote the channel, spatial, and frequency features, respectively. These features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a fused tensor:

To balance feature scale and capture cross-domain contextual dependencies, a

convolution with stride

is first applied to reduce redundancy and aggregate local correlations:

Then, a set of

multi-scale convolutional filters with different kernel sizes is employed to extract hierarchical contextual information from

. Specifically, we use

,

, and

convolution kernels to capture short-, mid-, and long-range dependencies, respectively:

where

p denotes the padding size ensuring spatial consistency.

The outputs of the three scales are concatenated and further refined through a convolutional fusion layer followed by batch normalization:

To strengthen the residual learning ability and prevent information loss, a shortcut connection from

to the normalized feature is introduced, and the result is activated by a sigmoid function to generate the final enhanced feature representation:

where

denotes the sigmoid activation. The resulting fused feature

contains multi-scale, cross-domain information that balances local texture, global semantics, and structural frequency cues.

In the context of facial expression recognition, this fusion mechanism provides two major benefits: (1) it integrates heterogeneous features from multiple domains (appearance, structure, and spectrum) into a coherent embedding space, and (2) it adaptively emphasizes expression-relevant cues while suppressing illumination- or identity-related noise. Consequently, the CDFEF module produces a semantically consistent and discriminative representation, significantly improving emotion recognition performance across varying subjects and lighting conditions.

2.9. Classification Head and Optimization Objective

After cross-domain fusion, the enhanced feature representation encapsulates spatial, spectral, and semantic information that collectively describe the facial expression. To perform emotion classification, Z is first flattened and passed into a fully connected (FC) layer that maps the fused feature into the probability space of predefined emotion categories.

Formally, the flattened vector is expressed as:

where

represents the total number of feature elements. The FC layer projects this embedding into a

K-dimensional output corresponding to

K emotion classes:

where

and

are learnable parameters, and

denotes the predicted class probabilities. In this study,

corresponding to seven basic emotion categories:

Angry,

Disgust,

Fear,

Happy,

Neutral,

Sad, and

Surprise.

2.9.1. Optimization Objective

The network is optimized using the standard cross-entropy loss, which measures the divergence between predicted probabilities

and the one-hot encoded ground truth label

y:

To further stabilize convergence and enhance robustness against inter-subject variations and subtle expression differences, we additionally apply

-based weight regularization, yielding the total optimization objective:

where

is a regularization coefficient controlling the trade-off between classification accuracy and model generalization. This objective function ensures that the model not only maximizes the likelihood of correct emotion predictions but also mitigates overfitting caused by dataset imbalance and limited expression diversity. During training, the AdamW optimizer is employed with a cosine learning rate schedule to maintain stable convergence and preserve the discriminative geometry of the fused representation

Z.

3. Experiments

3.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted to evaluate the proposed multi-domain facial expression recognition framework under consistent and reproducible conditions. The model was implemented in the PyTorch deep learning framework and trained on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB VRAM), Intel i9-13900K CPU, and 64 GB RAM. We used the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of , a weight decay coefficient of , and a batch size of 32. The learning rate was adjusted using a cosine annealing schedule for smooth convergence over 100 epochs.

For data preprocessing, all input images were resized to pixels and normalized to zero mean and unit variance. To enhance model generalization and prevent overfitting, data augmentation strategies were applied, including random horizontal flipping, rotation, cropping, and color-based photometric adjustments such as brightness, contrast, and saturation perturbation. The Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder was initialized with official pretrained weights released by the authors, while the three feature extraction branches and the CDFEF module were trained from scratch. A dropout rate of 0.3 was used in the classification head to improve robustness, and early stopping based on validation accuracy was applied to select the optimal model checkpoint. Unless otherwise specified, all quantitative results reported in this paper are obtained from the validation sets of the respective datasets.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively assess the performance of the proposed framework, four standard classification metrics were adopted: Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Accuracy. These metrics collectively measure the predictive reliability, sensitivity, and overall recognition capability of the model.

(1) Precision. Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive:

where TP and FP represent the number of true positives and false positives, respectively.

(2) Recall. Recall measures the proportion of correctly identified positive samples among all actual positive samples:

where FN denotes the number of false negatives.

(3) F1-score. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced evaluation metric for scenarios with uneven class distributions:

(4) Accuracy. Accuracy reflects the overall proportion of correctly predicted samples in the dataset:

For all evaluations, Precision, Recall, and F1-score are reported as macro-averaged results across the seven emotion categories (Angry, Disgust, Fear, Happy, Neutral, Sad, and Surprise) to ensure fairness under class imbalance.

3.3. Datasets

To comprehensively evaluate the performance and generalization ability of the proposed multi-domain facial expression recognition framework, three widely used facial expression datasets were adopted: the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) [

11], the Facial Expression Recognition 2013 (FER2013) dataset [

12], and the Real-world Affective Face Database (RAF-DB) [

13]. These datasets collectively cover both controlled laboratory conditions and in-the-wild environments, providing a balanced benchmark for assessing recognition robustness under varying illumination, pose, and expression intensity.

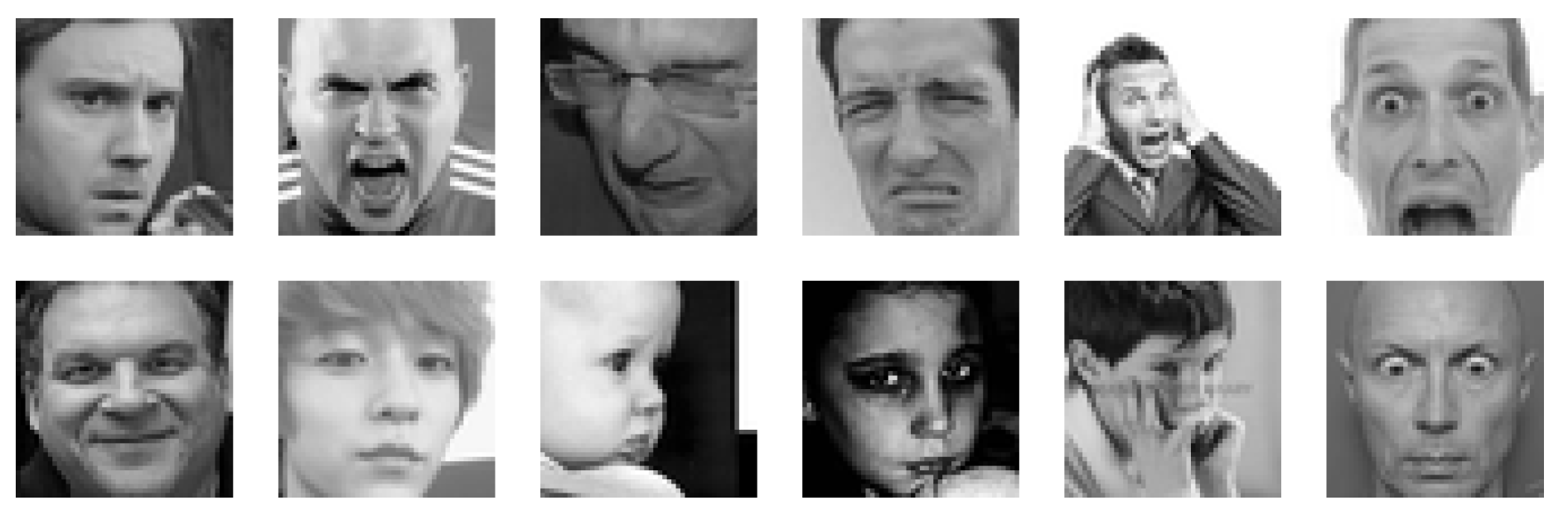

1) Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF). KDEF is a classic laboratory-controlled facial expression dataset, developed by the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. It contains 4900 high-quality color photographs of 70 individuals (35 male and 35 female), each displaying seven basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, neutrality, sadness, and surprise. All images are captured under consistent illumination and frontal viewpoints, making KDEF ideal for baseline training and for evaluating the model’s ability to learn clear and canonical emotional representations. Representative samples are shown in

Figure 6.

2) Facial Expression Recognition 2013 (FER2013). FER2013 is a large-scale facial expression benchmark released during the ICML 2013 Representation Learning Challenge. It includes 35,887 grayscale facial images of

resolution, each manually annotated into seven emotion categories identical to KDEF. Compared with controlled datasets, FER2013 presents a significantly higher degree of variability in pose, lighting, and occlusion, thus serving as a more challenging in-the-wild benchmark for evaluating the robustness of expression recognition models. Sample images are visualized in

Figure 7.

3) Real-world Affective Face Database (RAF-DB). RAF-DB is a real-world facial expression dataset designed for unconstrained emotion recognition. It contains approximately 30,000 diverse facial images collected from the Internet, covering wide variations in age, gender, ethnicity, head pose, and illumination. Each image is annotated by multiple human raters to ensure label reliability. RAF-DB is considered one of the most comprehensive datasets for affective computing, providing a strong foundation for evaluating model performance under real-world conditions. Representative samples are illustrated in

Figure 8.

Overall, these three datasets complement each other: KDEF provides clean and structured emotion samples, FER2013 introduces moderate noise and variation, and RAF-DB reflects the complexity of natural environments. Their combination enables a thorough validation of the proposed model’s accuracy, robustness, and generalization ability.

3.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed framework, we compared it with a series of representative state-of-the-art models, including AlexNet [

3], VGG [

4], ResNet [

5], DenseNet [

6], EfficientNet [

7], ViT [

8], and ensemble-based models such as Gimefive [

32] and the Attention-Enhanced Ensemble [

33]. All models were trained under identical configurations to ensure fairness, and the ViT encoder in our framework was initialized from official pretrained weights. The compared methods followed their respective official training settings and evaluation protocols.

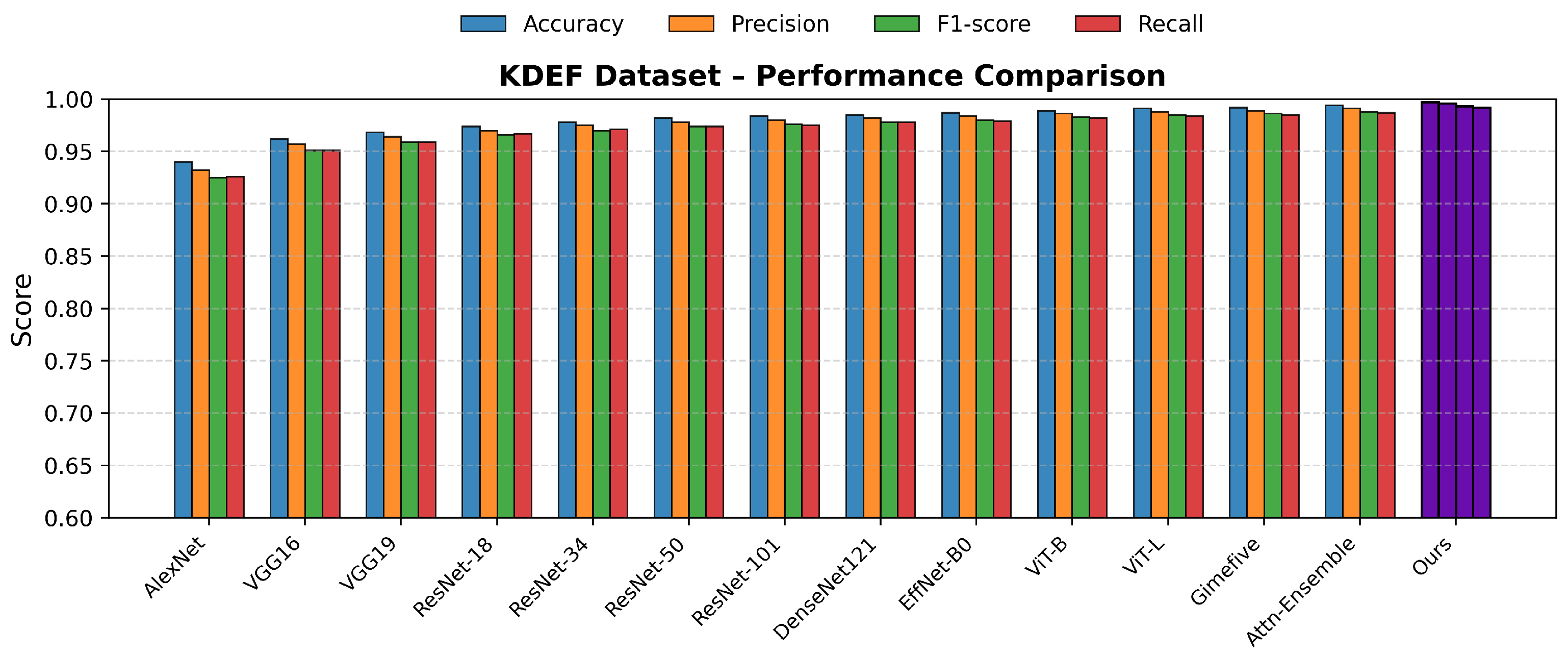

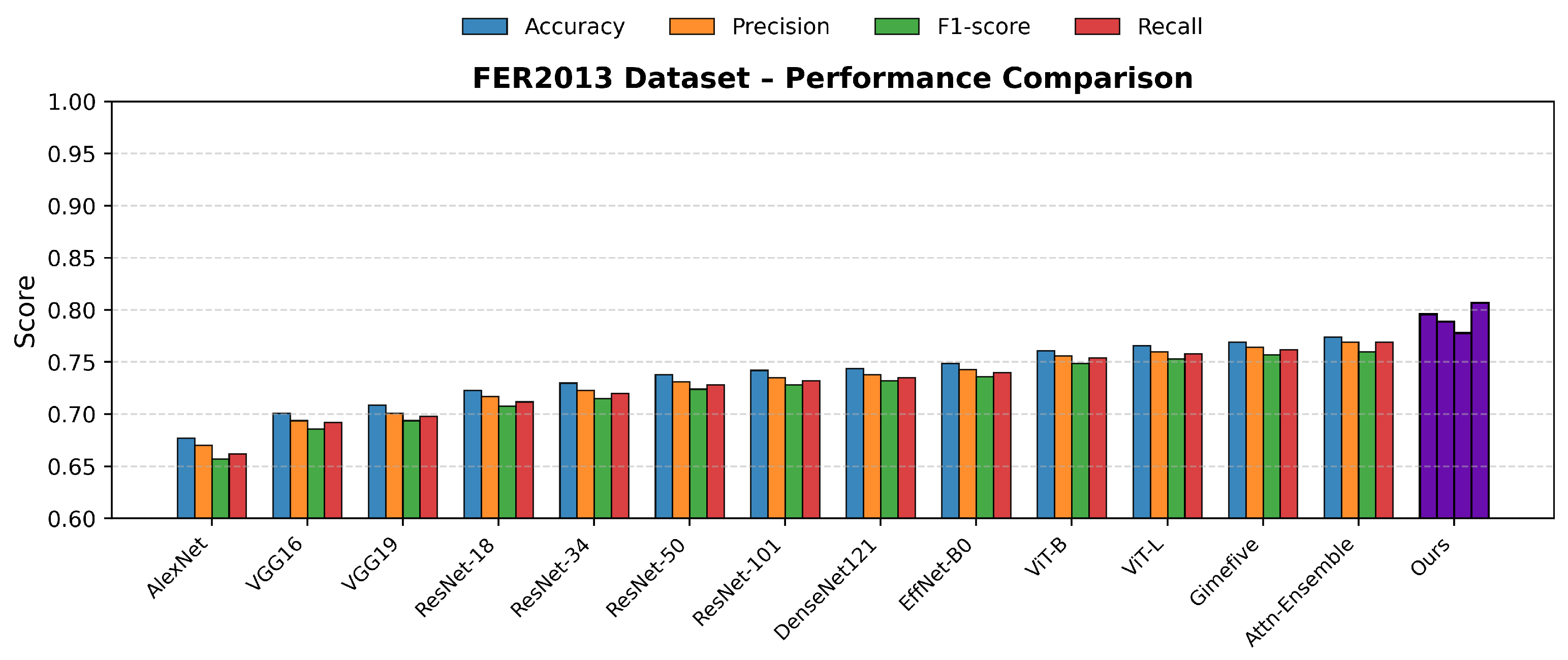

Table 1 summarizes the

best single-run results of all compared models. The proposed method achieves the highest performance on all four evaluation metrics and across all datasets, demonstrating its superior feature representation and generalization capability.

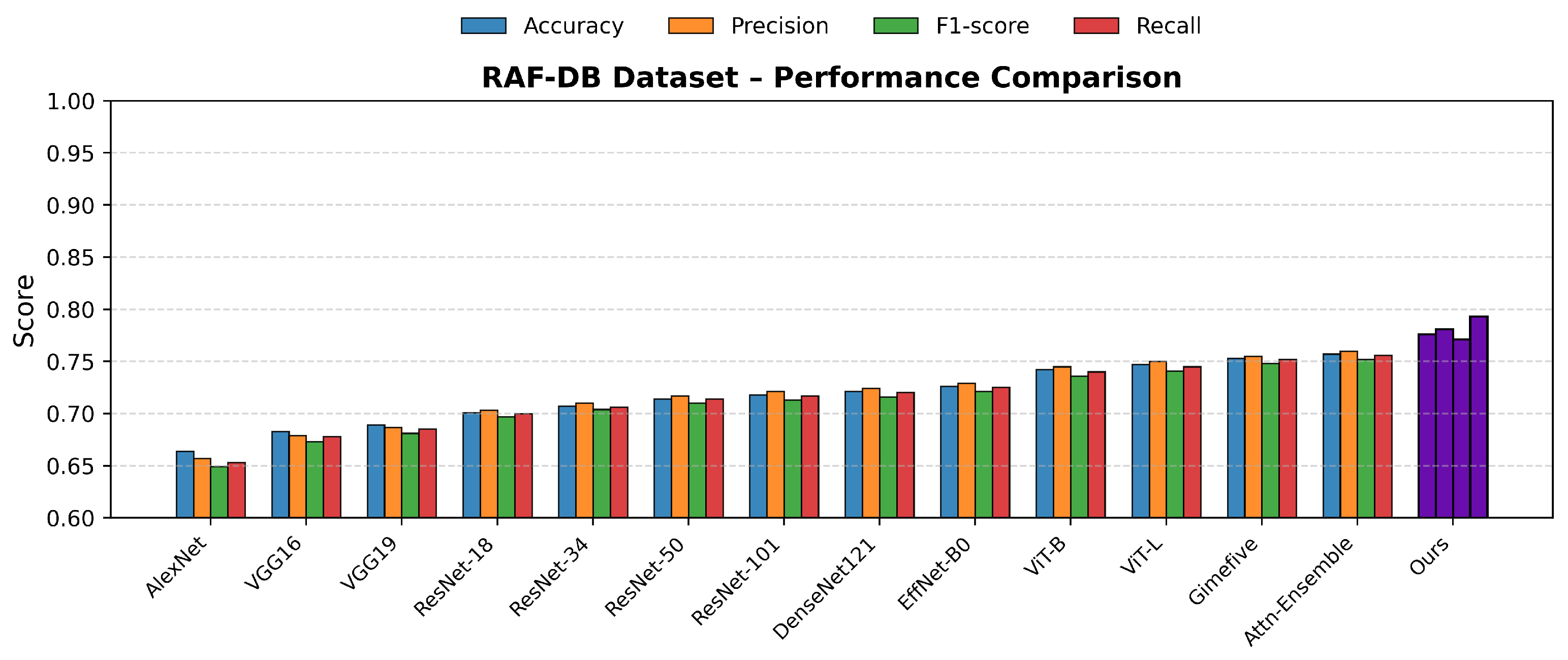

Specifically, on the KDEF dataset, our model achieves an Accuracy of 0.997 and an F1-score of 0.993, indicating near-perfect recognition under controlled conditions. On FER2013 and RAF-DB, which contain larger pose, illumination, and expression variations, our approach still reaches the best Accuracy values of 0.796 and 0.776, respectively, outperforming the second-best method (Attention-Enhanced Ensemble) by 0.9% and 1.9%. These best single-run results validate the effectiveness of the proposed Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module in handling both structured and unconstrained facial expression data.

The subsequent

Table 2 (Statistical Stability Analysis) further examines the consistency of these optimal results under repeated experiments, confirming that the proposed model maintains both high performance and strong reproducibility across multiple training runs. To facilitate intuitive comparison across different benchmarks, we visualize the detailed results in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, which illustrate the performance of various models across four standard evaluation metrics (

Accuracy,

Precision,

F1-score, and

Recall) on the KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB datasets, respectively. These plots clearly show that the proposed Multi-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion Transformer (MDFEFT) consistently achieves the highest performance among all competing methods. In particular, our method maintains near-perfect recognition on KDEF, and demonstrates significant robustness improvements on FER2013 and RAF-DB, indicating strong adaptability to variations in pose, illumination, and expression intensity.

3.5. Statistical Stability Analysis

To further evaluate the statistical robustness of the proposed model, five independent experiments were conducted using different random seeds on the KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB datasets. Each run adopted identical hyperparameter settings, data augmentation, and optimization configurations to ensure comparability across trials. The results were reported as the mean value () and standard deviation () for four standard evaluation metrics: Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall.

As shown in

Table 2, the proposed method demonstrates stable performance across all datasets under repeated experiments. For the controlled KDEF dataset, the standard deviation remains within

–

, indicating that the model maintains reliable convergence even with varying random initializations. For the more challenging FER2013 and RAF-DB datasets, which contain greater diversity in illumination, pose, and expression, the standard deviation increases to approximately

–

, representing reasonable fluctuations due to stochastic training dynamics.

Compared with the best single-run results in

Table 1, the mean Accuracy shows only a marginal decrease of about 1–2%, remaining within acceptable statistical tolerance. This result confirms that the proposed method provides not only superior recognition accuracy but also excellent reproducibility and robustness across multiple independent runs. Such statistical consistency further validates the stability and reliability of the proposed framework for practical facial expression recognition in real-world scenarios.

3.6. Ablation Study

To assess the individual contributions of each component, we performed ablation experiments on the KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB datasets. We systematically removed (1) the three-branch feature extraction module (Channel, Space, and Frequency branches) and (2) the Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module, while maintaining identical training configurations to the full model.

3.7. Ablation Study of Proposed Method

As shown in

Table 3, both the three-branch module and the CDFEF module are crucial to the overall performance. Removing the three-branch module leads to a noticeable performance drop on all datasets, with Accuracy decreases of about 1.0–1.2%, reflecting its essential role in extracting complementary information from the channel, spatial, and frequency domains.

Similarly, removing the CDFEF module results in consistent declines across all datasets, with Accuracy reductions from 0.997 to 0.991 on KDEF, from 0.786 to 0.775 on FER2013, and from 0.756 to 0.751 on RAF-DB. This demonstrates that the CDFEF module effectively enhances cross-domain feature interaction and adaptive fusion.

Overall, the full model achieves the best performance across all metrics and datasets, confirming that the combination of multi-branch feature extraction and cross-domain fusion significantly strengthens discriminative feature representation and generalization under diverse facial expressions and illumination conditions.

3.8. Ablation on Three Complementary Feature Extraction Branches

To further examine the contribution of each feature extraction branch and their joint effects, we conducted detailed ablation experiments on the Channel, Space, and Frequency branches. Each branch is responsible for modeling distinct feature dimensions: the Channel Branch captures inter-channel dependencies, the Space Branch emphasizes spatial saliency, and the Frequency Branch extracts high-frequency texture representations. We additionally investigated the impact of removing two branches simultaneously to evaluate their complementarity.

As shown in

Table 4, each branch contributes meaningfully to the model’s overall performance. When removing individual branches, all datasets exhibit performance degradation, with the Frequency Branch removal causing the largest drop due to the loss of discriminative high-frequency texture cues.

When two branches are removed simultaneously, the decline becomes more pronounced and nearly additive. For instance, removing both Space and Frequency branches reduces Accuracy from 0.997 to 0.981 on KDEF, from 0.786 to 0.761 on FER2013, and from 0.756 to 0.738 on RAF-DB. This confirms that the three branches provide complementary representations and that their integration enables a richer, more stable encoding of facial expression information.

The full model achieves the highest overall performance, validating the effectiveness of the joint multi-domain representation strategy that combines spatial, channel, and frequency-level cues for robust facial emotion recognition.

3.9. Effect of the Channel Allocation Ratio

To investigate the balance between global and local channel modeling in the Channel Branch, we conducted an extensive ablation study on the channel allocation ratio

. This parameter controls the proportion between the local feature pathway (Group-Wise Convolution, GWC) and the global aggregation pathway (Point-Wise Convolution, PWC), determining how the network allocates capacity between fine-grained local cues and holistic statistics. We evaluated

values from 0.1 to 1.0 across three datasets. FER2013 achieves the best performance at

, while KDEF and RAF-DB achieve their highest performance at

. Detailed quantitative results are reported in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, moderate values of

yield the most balanced performance across all datasets. Specifically, the optimal range

consistently achieves high accuracy and stable generalization. On FER2013,

produces the highest Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall (0.786, 0.779, 0.768, and 0.787, respectively), suggesting that in-the-wild data benefit from slightly stronger local specialization. For KDEF and RAF-DB, the balanced configuration

achieves the best overall results (KDEF: 0.997, 0.996, 0.993, 0.992; RAF-DB: 0.756, 0.761, 0.751, 0.773), indicating that controlled or moderately unconstrained conditions prefer an even distribution between local and global representations. Very small or large

values lead to performance degradation due to over-aggregated global statistics or excessive local fragmentation. Overall, the model maintains strong stability and accuracy in the range

, highlighting the adaptive capability of the Channel Branch to balance global–local information under different domain conditions.

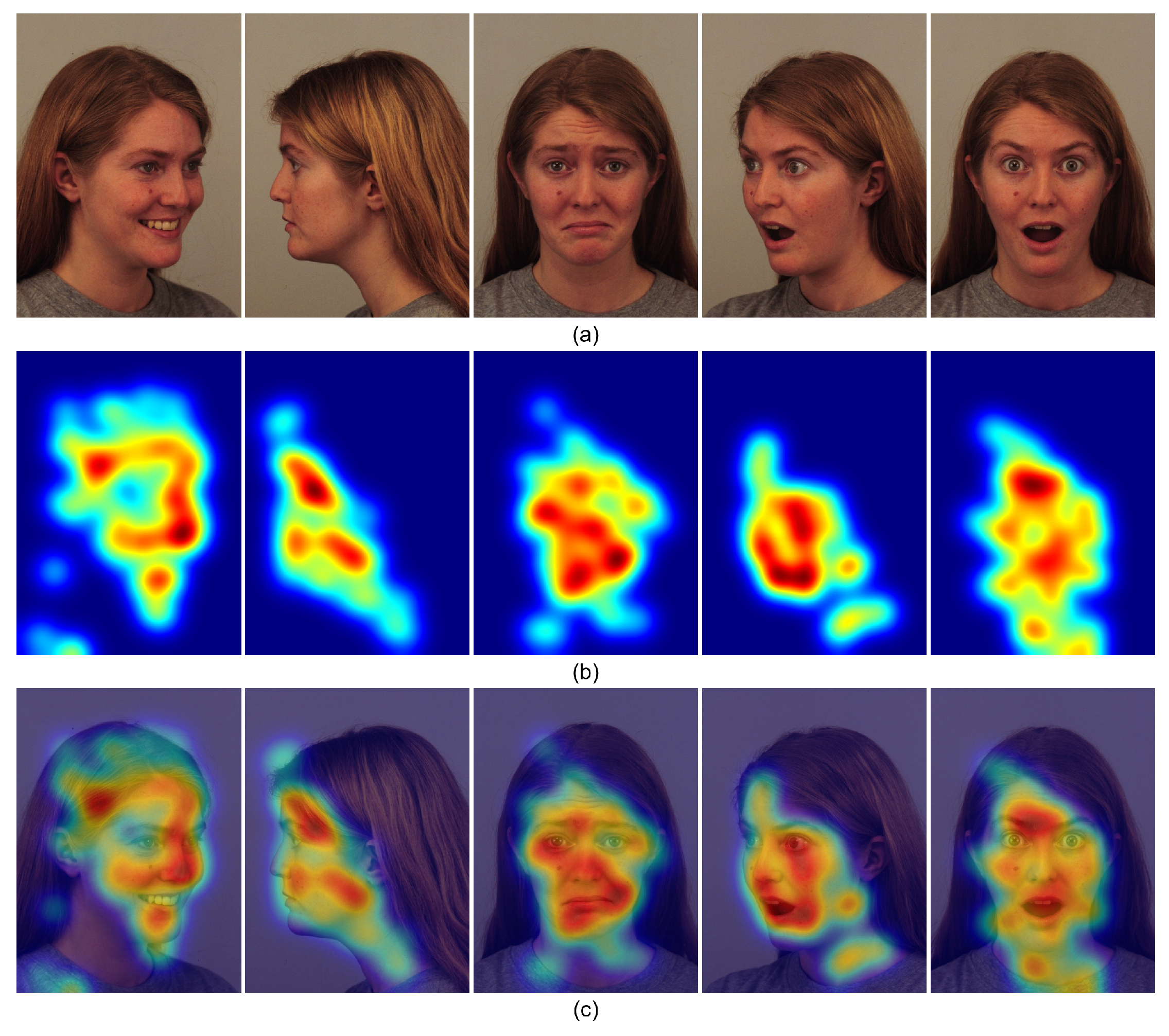

3.10. Visual Explanation via Grad-CAM

To further interpret the decision-making behavior of the proposed model, we employ Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) [

63] to visualize the class-discriminative regions that most contribute to emotion prediction. As illustrated in

Figure 12, each sample consists of three components: The heatmaps are extracted from the last feature layer of the

Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module, highlighting spatial regions that exhibit the highest gradient responses with respect to the predicted emotion class. This provides an intuitive visualization of how the model focuses on discriminative facial regions during inference.

As shown in

Figure 12, the model predominantly attends to semantically meaningful facial areas such as the eyes, mouth, and forehead, which are highly correlated with emotional expressions. For example, in the cases of

Happiness and

Surprise, the model focuses on the corners of the mouth and raised eyebrows, while for

Sadness or

Fear, the attention shifts toward the eyes and brow regions. These visual explanations demonstrate that the

CDFEF module effectively aggregates multi-branch features and highlights key emotional regions, aligning the model’s internal attention patterns with human-perceptible cues. Such consistency between semantic activation and emotional relevance verifies both the interpretability and robustness of the proposed architecture.

3.11. Cross-Domain Generalization Experiments

To further evaluate the domain transferability and robustness of the proposed framework, we conducted cross-domain generalization experiments among the three datasets: KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB. Each dataset was used as a source domain for training and then tested on the other two as target domains (KDEF→FER2013, KDEF→RAF-DB, FER2013→KDEF, FER2013→RAF-DB, RAF-DB→KDEF, RAF-DB→FER2013). All models were trained under identical configurations without any fine-tuning on the target domain, ensuring a fair and consistent comparison of cross-domain generalization performance.

As shown in

Table 6, the overall cross-domain performance drops significantly compared to within-domain training, highlighting the challenges of domain shift in facial expression recognition. When trained on the controlled KDEF dataset, the model exhibits limited generalization to more diverse domains such as FER2013 and RAF-DB, with Accuracy values of 0.572 and 0.586, respectively. This drop can be attributed to the restricted variation of KDEF in lighting, pose, and emotion intensity. Models trained on FER2013 show comparatively stronger transfer to KDEF (Accuracy 0.642), as the in-the-wild training data exposes the model to richer visual diversity. However, the same model still struggles on RAF-DB (Accuracy 0.594) due to annotation differences and fine-grained emotion definitions. Similarly, models trained on RAF-DB achieve moderate transfer to KDEF (Accuracy 0.627) but perform poorly on FER2013 (Accuracy 0.559), reflecting asymmetric domain complexity and texture distribution mismatches between datasets.

Overall, these results confirm that despite the proposed model’s adaptive feature extraction and fusion design, a notable performance degradation persists under unseen domain shifts. This demonstrates the importance of incorporating explicit domain alignment or contrastive adaptation mechanisms to further enhance cross-domain emotional representation learning.

4. Conclusion and Future Work

This paper presented a unified Multi-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion Transformer (MDFEFT) framework for robust and cross-domain facial expression recognition. The proposed approach integrates a ViT-based global encoder with three complementary branches—channel, spatial, and frequency—to jointly capture global semantics, local saliency, and spectral texture cues. An adaptive Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module was further designed to align and integrate heterogeneous features, thereby achieving illumination-robust and domain-consistent emotional representations. Comprehensive experiments conducted on three benchmark datasets (KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB) demonstrated that MDFEFT achieves superior accuracy and generalization performance compared with existing CNN-, Transformer-, and ensemble-based methods. Specifically, the proposed method attains 99.7%, 79.6%, and 77.6% accuracy on KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB, respectively, surpassing the strongest baselines by up to 2.2%. Moreover, cross-domain validation results confirm that MDFEFT maintains strong transferability and robustness across distinct datasets.

In future work, several directions will be explored to further enhance model efficiency and adaptability. First, we plan to develop a lightweight version of MDFEFT for real-time applications on edge and mobile devices. Second, we aim to incorporate self-supervised domain adaptation strategies to improve generalization under unseen cultural or environmental conditions. Finally, extending the current framework to multi-modal emotion analysis by integrating facial, audio, and physiological signals represents a promising avenue for achieving comprehensive affective understanding in real-world human–computer interaction systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.S. and M.-J.-S.W.; methodology, K.L.S. and M.-J.-S.W.; software, K.L.S.; validation, K.L.S. and M.-J.-S.W.; formal analysis, K.L.S.; investigation, K.L.S.; resources, M.-J.-S.W.; data curation, K.L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.S.; writing—review and editing, K.L.S. and M.-J.-S.W.; visualization, K.L.S.; supervision, M.-J.-S.W.; project administration, M.-J.-S.W.; funding acquisition, M.-J.-S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was fully covered by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study uses only publicly available datasets and involves no human participants, interventions, or prospectively collected data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study uses only publicly available datasets and involves no human participants or personally identifiable data collection.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the technical and administrative support provided by the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1) for English language refinement and assistance in improving the clarity of expression. The authors have carefully reviewed, verified, and edited all AI-assisted content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FER |

Facial Expression Recognition |

| ViT |

Vision Transformer |

| MDFEF |

Multi-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion |

| CDFEF |

Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion |

| DFT |

Discrete Fourier Transform |

| IDFT |

Inverse Discrete Fourier Transform |

| MSA |

Multi-Head Self-Attention |

| MLP |

Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| GWC |

Group-Wise Convolution |

| PWC |

Point-Wise Convolution |

| FC |

Fully Connected (Layer) |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| RA F-DB |

Real-world Affective Face Database |

| KDEF |

Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces Dataset |

References

- Ko, B. A brief review of facial emotion recognition based on visual information. Sensors 2018, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Deep facial expression recognition: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 13, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2012). Curran Associates, Inc., 2012, pp. 1097–1105. Introduced the AlexNet architecture, winner of ILSVRC 2012. [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2015. Introduced VGG16 and VGG19 architectures.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity mappings in deep residual networks. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer; 2016; pp. 630–645. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017, pp. 4700–4708. Proposed DenseNet for feature reuse and gradient flow efficiency. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR, 2019, pp. 6105–6114. Introduced compound scaling for CNN width, depth, and resolution.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021. Proposed the Vision Transformer (ViT), applying transformer architecture to image patches.

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Kanade, T.; Saragih, J.M.; Ambadar, Z.; Matthews, I.A. The extended Cohn-Kanade dataset (CK+): A complete dataset for action unit and emotion-specified expression. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), San Francisco, CA, USA; 2010; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, D.; Flykt, A.; Öhman, A. The Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF). Technical report, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychology Section, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 1998. Available at: https://www.kdef.se/.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Erhan, D.; Carrier, P.L.; Courville, A.; Mirza, M.; Hamner, B.; Cukierski, W.; Tang, Y.; Thaler, D.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Challenges in Representation Learning: A report on three machine learning contests. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Neural Information Processing (ICONIP 2013), Daegu, Korea, 2013; pp. 117–124. Dataset: Facial Expression Recognition 2013 (FER2013). [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Reliable Crowdsourcing and Deep Locality-Preserving Learning for Unconstrained Facial Expression Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019, 28, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollias, D.; Tzirakis, P.; Baird, A.; Cowen, A.; Zafeiriou, S. ABAW: Valence-Arousal estimation, expression recognition, action unit detection & emotional reaction intensity estimation challenges. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, Canada; 2023; pp. 5889–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, L.; Liu, J. Towards East Asian facial expression recognition in the real world: A new database and deep recognition baseline. Sensors 2022, 22, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barsoum, E.; Zhang, C.; Canton-Ferrer, C.; Zhang, Z. Training deep networks for facial expression recognition with crowd-sourced label distribution. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI), Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W.; Du, J. Reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning for expression recognition in the wild. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA; 2017; pp. 2584–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Deng, W. Reliable crowdsourcing and deep locality-preserving learning for unconstrained facial expression recognition. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019, 28, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Cui, J. Recognition of teachers’ facial expression intensity based on Convolutional Neural Network and attention mechanism. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 226437–226444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.N.; Cherukuri, K.T. Visual attention based composite dense neural network for facial expression recognition. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2022, 13, 16229–16242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, Y. Facial expression recognition using pose-guided face alignment and discriminative features based on deep learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 69267–69277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Gu, Y.; Hu, M.; Ren, F. Multi-task and Attention Collaborative Network for Facial Emotion Recognition. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2021, 16, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Chenniappan, P.; Devaraj, S.; Madian, N.N. Novel deep learning model for facial expression recognition based on maximum boosted CNN and LSTM. IET Image Processing 2020, 14, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurav, S.; Gidde, P.; Saini, R.; Singh, S. Dual integrated convolutional neural network for real-time facial expression recognition in the wild. The Visual Computer 2022, 38, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurav, S.; Saini, R.; Singh, S. EmNet: A deep integrated convolutional neural network for facial emotion recognition in the wild. Applied Intelligence 2021, 51, 5543–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.; Kumar, M. AutoFER: PCA and PSO based automatic facial emotion recognition. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 3039–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; et al. . FER-net: Facial expression recognition using deep neural net. Neural Computing and Applications 2021, 33, 9125–9136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lima, B. Facial expression recognition via ResNet-50. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2021, 2, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, D.D.S.A. An efficient facial emotion recognition system using novel deep learning neural network-regression activation classifier. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 17543–17568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, A.; Asghar, Z.M.; Ali, M.; Batool, U. An efficient deep learning technique for facial emotion recognition. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 1649–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentoumi, M.; Daoud, M.; Benaouali, M.; Ahmed, T.A. Improvement of emotion recognition from facial images using deep learning and early stopping cross-validation. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 29887–29917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kawka, L. Gimefive: Towards interpretable facial emotion classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.15662. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, T.; Yasir, M.; Choi, C. Attention-enhanced optimized deep ensemble network for effective facial emotion recognition. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2025, 119, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Sun, K.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Self-supervised vision transformer-based few-shot learning for facial expression recognition. Information Sciences 2023, 634, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Guo, G. Vision Transformer With Attentive Pooling for Robust Facial Expression Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2023, 14, 3244–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Xiao, Z. Enhanced Hybrid Vision Transformer with Multi-Scale Feature Integration and Patch Dropping for Facial Expression Recognition. Sensors 2024, 24, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bie, M.; Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Song, K.; Che, X. Swin-FER: Swin Transformer for Facial Expression Recognition. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Pu, T.; Wu, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, L.; Lin, L. Cross-Domain Facial Expression Recognition: A Unified Evaluation Benchmark and Adversarial Graph Learning. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 44, 9887–9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.L.; An, H.Y.; Yao, Y.; Su, W.C.; Li, G.; Saifullah. ; Sun, B.F.; Wang, M.J.S. FSTGAT: Financial Spatio-Temporal Graph Attention Network for Non-Stationary Financial Systems and Its Application in Stock Price Prediction. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Qu, H.R.; Su, W.H. From sensors to insights: Technological trends in image-based high-throughput plant phenotyping. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, 101257. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.F.; Su, W.H. The application of deep learning in the whole potato production Chain: A Comprehensive review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.F.; Qin, Y.M.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, M.; Schardong, I.B.; Cui, K. RA-CottNet: A Real-Time High-Precision Deep Learning Model for Cotton Boll and Flower Recognition. AI 2025, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xi, X.; Wu, A.Q.; Wang, R.F. ToRLNet: A Lightweight Deep Learning Model for Tomato Detection and Quality Assessment Across Ripeness Stages. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huihui, S.; Rui-Feng, W. BMDNet-YOLO: A Lightweight and Robust Model for High-Precision Real-Time Recognition of Blueberry Maturity. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1202. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.F.; Tu, Y.H.; Li, X.C.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhao, C.T.; Yang, C.; Su, W.H. An Intelligent Robot Based on Optimized YOLOv11l for Weed Control in Lettuce. In Proceedings of the 2025 ASABE Annual International Meeting. American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers; 2025; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Umer, S.; Rout, K.R.; Nappi, M. Facial expression recognition with tradeoffs between data augmentation and deep learning features. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2022, 13, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. Making Convolutional Networks Shift-Invariant Again. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2019, pp. 7324–7334.

- Xiao, Z.X. Delving deeper into Anti-aliasing in ConvNets. International Journal of Computer Vision 2023, 131, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; et al. . Knowledge transferred fine-tuning: convolutional neural network is born again with anti-aliasing even in data-limited situations. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 68384–68396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, F.A.; Cimmino, L.; Mocanu, B.C.; Narducci, F.; Pop, F. The limitations for expression recognition in computer vision introduced by facial masks. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2023, 82, 11305–11319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hirota, K.; Dai, Y. Patch Attention Convolutional Vision Transformer for Facial Expression Recognition with Occlusion. Information Sciences 2023, 619, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Chai, L.; Sun, H. Appearance and Geometry Transformer for Facial Expression Recognition in the Wild. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2023, 107, 108583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z. A Convolution–Transformer Dual Branch Network for Head-Pose and Occlusion Facial Expression Recognition. The Visual Computer 2023, 39, 2277–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, X.; Yang, J.; Meng, D.; Qiao, Y. Region Attention Networks for Pose and Occlusion Robust Facial Expression Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 29, 4057–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Facial Expression Recognition Using Frequency Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yang, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Conditional fault tolerance in a class of Cayley graphs. International Journal of Computer Mathematics 2016, 93, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, M. Sufficient conditions for graphs to be maximally 4-restricted edge connected. Australas. J Comb. 2018, 70, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, M. A Note on the Connectivity of m-Ary n-Dimensional Hypercubes. Parallel Processing Letters 2019, 29, 1950017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiang, D.; Wang, S. Connectivity and diagnosability of leaf-sort graphs. Parallel Processing Letters 2020, 30, 2040004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xu, S.; Jiang, J.; Xiang, D.; Hsieh, S.Y. Global reliable diagnosis of networks based on Self-Comparative Diagnosis Model and g-good-neighbor property. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2025, 103698. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, D.; Hsieh, S.Y.; et al. G-good-neighbor diagnosability under the modified comparison model for multiprocessor systems. Theoretical Computer Science 2025, 1028, 115027. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, L.; Zhang, F. The maximum forcing number of a polyomino. Australas. J. Combin 2017, 69, 306–314. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Cogswell, M.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Why did you say that? arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.07450. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed facial expression recognition framework, which integrates data enhancement, ViT-based feature encoding, three-domain feature extraction, cross-domain fusion (CDFEF), and final emotion classification.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed facial expression recognition framework, which integrates data enhancement, ViT-based feature encoding, three-domain feature extraction, cross-domain fusion (CDFEF), and final emotion classification.

Figure 2.

Structure of the Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder. The input image is divided into patches, embedded through convolution, combined with positional encodings, and processed by stacked Transformer encoder blocks to produce the global representation .

Figure 2.

Structure of the Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder. The input image is divided into patches, embedded through convolution, combined with positional encodings, and processed by stacked Transformer encoder blocks to produce the global representation .

Figure 3.

Structure of the multi-branch feature extraction module. The Channel Branch (bottom) enhances inter-channel dependencies via Point-Wise and Group-Wise convolutions, while the Frequency Branch (top) captures spectral texture information through Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and learnable weighting. Both branches produce domain-specific features and , forming the foundation for cross-domain fusion.

Figure 3.

Structure of the multi-branch feature extraction module. The Channel Branch (bottom) enhances inter-channel dependencies via Point-Wise and Group-Wise convolutions, while the Frequency Branch (top) captures spectral texture information through Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and learnable weighting. Both branches produce domain-specific features and , forming the foundation for cross-domain fusion.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module. The channel (), spatial (), and frequency () features are concatenated and processed by multi-scale convolutions, followed by normalization, residual enhancement, and sigmoid activation to produce the unified fused representation Z.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Cross-Domain Feature Enhancement and Fusion (CDFEF) module. The channel (), spatial (), and frequency () features are concatenated and processed by multi-scale convolutions, followed by normalization, residual enhancement, and sigmoid activation to produce the unified fused representation Z.

Figure 6.

Example facial images from the KDEF dataset captured under controlled laboratory conditions, covering seven basic emotions with uniform lighting and frontal pose.

Figure 6.

Example facial images from the KDEF dataset captured under controlled laboratory conditions, covering seven basic emotions with uniform lighting and frontal pose.

Figure 7.

Example images from the FER2013 dataset collected in the wild, exhibiting large variations in facial pose, illumination, and occlusion.

Figure 7.

Example images from the FER2013 dataset collected in the wild, exhibiting large variations in facial pose, illumination, and occlusion.

Figure 8.

Sample facial images from the RAF-DB dataset captured under real-world conditions, showing diverse demographics, poses, and illumination variations.

Figure 8.

Sample facial images from the RAF-DB dataset captured under real-world conditions, showing diverse demographics, poses, and illumination variations.

Figure 9.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the KDEF dataset.

Figure 9.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the KDEF dataset.

Figure 10.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the FER2013 dataset.

Figure 10.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the FER2013 dataset.

Figure 11.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the RAF-DB dataset.

Figure 11.

Performance comparison across four evaluation metrics on the RAF-DB dataset.

Figure 12.

Grad-CAM visualization of the proposed model: (a) original facial images; (b) corresponding Grad-CAM activation heatmaps; and (c) overlay results showing the model’s attention focus.

Figure 12.

Grad-CAM visualization of the proposed model: (a) original facial images; (b) corresponding Grad-CAM activation heatmaps; and (c) overlay results showing the model’s attention focus.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison (best single-run results) of different models on three benchmark datasets (KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB) across four evaluation metrics.

Table 1.

Quantitative comparison (best single-run results) of different models on three benchmark datasets (KDEF, FER2013, and RAF-DB) across four evaluation metrics.

| Dataset |

Method |

Accuracy |

Precision |

F1-score |

Recall |

| KDEF |

AlexNet |

0.940 |

0.932 |

0.925 |

0.926 |

| VGG16 |

0.962 |

0.957 |

0.951 |

0.951 |

| VGG19 |

0.968 |

0.964 |

0.959 |

0.959 |

| ResNet-18 |

0.974 |

0.970 |

0.966 |

0.967 |

| ResNet-34 |

0.978 |

0.975 |

0.970 |

0.971 |

| ResNet-50 |

0.982 |

0.978 |

0.974 |

0.974 |

| ResNet-101 |

0.984 |

0.980 |

0.976 |

0.975 |

| DenseNet121 |

0.985 |

0.982 |

0.978 |

0.978 |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

0.987 |

0.984 |

0.980 |

0.979 |

| ViT-B |

0.989 |

0.986 |

0.983 |

0.982 |

| ViT-L |

0.991 |

0.988 |

0.985 |

0.984 |

| Gimefive |

0.992 |

0.989 |

0.986 |

0.985 |

| Attention-Enhanced Ensemble |

0.994 |

0.991 |

0.988 |

0.987 |

| Ours (Proposed) |

0.997 |

0.996 |

0.993 |

0.992 |

| FER2013 |

AlexNet |

0.677 |

0.670 |

0.657 |

0.662 |

| VGG16 |

0.701 |

0.694 |

0.686 |

0.692 |

| VGG19 |

0.709 |

0.701 |

0.694 |

0.698 |

| ResNet-18 |

0.723 |

0.717 |

0.708 |

0.712 |

| ResNet-34 |

0.730 |

0.723 |

0.715 |

0.720 |

| ResNet-50 |

0.738 |

0.731 |

0.724 |

0.728 |

| ResNet-101 |

0.742 |

0.735 |

0.728 |

0.732 |

| DenseNet121 |

0.744 |

0.738 |

0.732 |

0.735 |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

0.749 |

0.743 |

0.736 |

0.740 |

| ViT-B |

0.761 |

0.756 |

0.749 |

0.754 |

| ViT-L |

0.766 |

0.760 |

0.753 |

0.758 |

| Gimefive |

0.769 |

0.764 |

0.757 |

0.762 |

| Attention-Enhanced Ensemble |

0.774 |

0.769 |

0.760 |

0.769 |

| Ours (Proposed) |

0.796 |

0.789 |

0.778 |

0.807 |

| RAF-DB |

AlexNet |

0.664 |

0.657 |

0.649 |

0.653 |

| VGG16 |

0.683 |

0.679 |

0.673 |

0.678 |

| VGG19 |

0.689 |

0.687 |

0.681 |

0.685 |

| ResNet-18 |

0.701 |

0.703 |

0.697 |

0.700 |

| ResNet-34 |

0.707 |

0.710 |

0.704 |

0.706 |

| ResNet-50 |

0.714 |

0.717 |

0.710 |

0.714 |

| ResNet-101 |

0.718 |

0.721 |

0.713 |

0.717 |

| DenseNet121 |

0.721 |

0.724 |

0.716 |

0.720 |

| EfficientNet-B0 |

0.726 |

0.729 |

0.721 |

0.725 |

| ViT-B |

0.742 |

0.745 |

0.736 |

0.740 |

| ViT-L |

0.747 |

0.750 |

0.741 |

0.745 |

| Gimefive |

0.753 |

0.755 |

0.748 |

0.752 |

| Attention-Enhanced Ensemble |

0.757 |

0.760 |

0.752 |

0.756 |

| Ours (Proposed) |

0.776 |

0.781 |

0.771 |

0.793 |

Table 2.

Statistical stability results (mean ± standard deviation ) of the proposed model over five independent runs.

Table 2.

Statistical stability results (mean ± standard deviation ) of the proposed model over five independent runs.

| Dataset |

Accuracy |

Precision |

F1-score |

Recall |

| KDEF |

0.97 ± 0.04 |

0.97 ± 0.03 |

0.96 ± 0.03 |

0.96 ± 0.03 |

| FER2013 |

0.77 ± 0.05 |

0.77 ± 0.05 |

0.75 ± 0.05 |

0.78 ± 0.06 |

| RAF-DB |

0.76 ± 0.04 |

0.76 ± 0.04 |

0.75 ± 0.04 |

0.77 ± 0.05 |

Table 3.

Ablation results with dataset-styled left column. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall for different configurations.

Table 3.

Ablation results with dataset-styled left column. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall for different configurations.

| Dataset |

Configuration |

Acc. |

Prec. |

F1 |

Rec. |

| KDEF |

w/o Three-Branch Module |

0.985 |

0.982 |

0.977 |

0.977 |

| w/o CDFEF Module |

0.991 |

0.988 |

0.984 |

0.983 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.997 |

0.996 |

0.993 |

0.992 |

| FER2013 |

w/o Three-Branch Module |

0.763 |

0.756 |

0.746 |

0.760 |

| w/o CDFEF Module |

0.775 |

0.769 |

0.758 |

0.783 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.786 |

0.779 |

0.768 |

0.787 |

| RAF-DB |

w/o Three-Branch Module |

0.741 |

0.746 |

0.735 |

0.753 |

| w/o CDFEF Module |

0.751 |

0.757 |

0.746 |

0.765 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.756 |

0.761 |

0.751 |

0.773 |

Table 4.

Ablation results of removing single or multiple feature extraction branches on three datasets. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall.

Table 4.

Ablation results of removing single or multiple feature extraction branches on three datasets. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall.

| Dataset |

Configuration |

Acc. |

Prec. |

F1 |

Rec. |

| KDEF |

w/o Channel Branch |

0.991 |

0.988 |

0.985 |

0.984 |

| w/o Space Branch |

0.988 |

0.985 |

0.981 |

0.981 |

| w/o Frequency Branch |

0.986 |

0.983 |

0.979 |

0.979 |

| w/o Channel + Space |

0.983 |

0.980 |

0.976 |

0.975 |

| w/o Channel + Frequency |

0.982 |

0.979 |

0.975 |

0.974 |

| w/o Space + Frequency |

0.981 |

0.978 |

0.974 |

0.973 |

| w/o All Branches |

0.978 |

0.975 |

0.971 |

0.971 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.997 |

0.996 |

0.993 |

0.992 |

| FER2013 |

w/o Channel Branch |

0.777 |

0.770 |

0.760 |

0.781 |

| w/o Space Branch |

0.773 |

0.766 |

0.755 |

0.776 |

| w/o Frequency Branch |

0.768 |

0.761 |

0.750 |

0.771 |

| w/o Channel + Space |

0.765 |

0.758 |

0.747 |

0.769 |

| w/o Channel + Frequency |

0.763 |

0.756 |

0.745 |

0.767 |

| w/o Space + Frequency |

0.761 |

0.754 |

0.743 |

0.765 |

| w/o All Branches |

0.758 |

0.751 |

0.740 |

0.762 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.786 |

0.779 |

0.768 |

0.787 |

| RAF-DB |

w/o Channel Branch |

0.748 |

0.754 |

0.744 |

0.763 |

| w/o Space Branch |

0.745 |

0.751 |

0.741 |

0.759 |

| w/o Frequency Branch |

0.743 |

0.749 |

0.739 |

0.757 |

| w/o Channel + Space |

0.740 |

0.746 |

0.736 |

0.754 |

| w/o Channel + Frequency |

0.739 |

0.745 |

0.735 |

0.752 |

| w/o Space + Frequency |

0.738 |

0.744 |

0.734 |

0.751 |

| w/o All Branches |

0.735 |

0.741 |

0.731 |

0.748 |

| Full Model (Ours) |

0.756 |

0.761 |

0.751 |

0.773 |

Table 5.

Ablation of the channel allocation ratio on three datasets. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall. The optimal range is , where FER2013 peaks at , while KDEF and RAF-DB peak at .

Table 5.

Ablation of the channel allocation ratio on three datasets. Each block reports Accuracy, Precision, F1-score, and Recall. The optimal range is , where FER2013 peaks at , while KDEF and RAF-DB peak at .

| Dataset |

|

Acc. |

Prec. |

F1 |

Rec. |

| KDEF |

0.1 |

0.988 |

0.985 |

0.981 |

0.981 |

| 0.2 |

0.992 |

0.989 |

0.985 |

0.984 |

| 0.3 |

0.995 |

0.993 |