1. Introduction

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a major cause of cardiovascular mortality worldwide [

1,

2]. Risk stratification is the cornerstone of management, with current guidelines recommending immediate reperfusion therapy only for massive PE, defined by the presence of systemic hypotension [

3,

4,

5]. However, the diagnosis of PE may represent a significant clinical challenge, particularly in patients who are hemodynamically stable and present with minimal or nonspecific symptoms. The detection of a mobile thrombus traversing the right heart-often a serpentine clot referred to as a “thrombus in transit” - is universally recognized as a powerful, independent predictor of adverse outcomes, with reported mortality rates approaching 80% when left untreated [

6,

7,

8]. Despite this, current international guidelines do not advocate for routine systemic thrombolysis in intermediate-high–risk PE, leaving management decisions in such scenarios highly individualized and clinically demanding [

3].

This case aims to illustrate the diagnostic complexity and therapeutic challenges posed by an intermediate-high–risk pulmonary embolism complicated by a large, mobile intracardiac thrombus, in a patient with minimal clinical symptoms.

In this case report, we present the clinical situation of a male patient who experienced a single transient episode of severe dyspnea, with paraclinical and laboratory findings revealing lactic metabolic acidosis and ischemic hepatorenal impairment. The values of cardiac biomarkers are moderately elevated, but nonspecific for the life-threatening conditions initially considered in the differential diagnosis, such as myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, or aortic dissection. Point-of-care-ultrasound transthoracic echocardiography (POCUS –TTE) was highly suggestive of pulmonary embolism, revealing a large, mobile intracardiac thrombus prolapsing through the tricuspid valve, which prompted further confirmatory imaging and underscored the challenges of therapeutic management.

2. Materials and Methods

All clinical data, images, and video materials are presented in accordance with institutional ethical standards, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans. All information has been managed in compliance with the European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), ensuring full protection of patient identity and privacy.

Point-of-Care Blood Analysis

Point-of-care (POC) blood testing was performed to evaluate cardiac biomarkers and arterial blood gases. Peripheral venous blood was collected in heparinized syringes for the determination of cardiac biomarkers, including troponin, N-terminal pro–B-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), and D-dimer, using the PATHFAST® analyzer (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Arterial blood samples were obtained in heparinized syringes for blood gas analysis, which was carried out using the Stat Profile PRIME® analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA, USA). All measurements were performed according to the manufacturers’ standard operating procedures and institutional laboratory quality control protocols.

The complete blood count, serum biochemistry, and coagulation profile were analyzed at the Central Laboratory of the Cluj-Napoca County Emergency Clinical University Hospital, Cluj, Romania.

Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed as a point-of-care (POCUS) examination using a Versana Active ultrasound system (General Electric Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The examination included standard parasternal long- and short-axis, apical four-chamber, and subcostal views. The assessment focused on right ventricular size and function, estimation of systolic pulmonary artery pressure, and the detection of intracardiac thrombi or other potential causes of acute right heart strain.

Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA)

Computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) was performed using a General Electric 8-slice IMA 660 scanner, with intravenous administration of Omnipaque™ 350 contrast agent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Case Presentation

3.1. Clinical Summary

A 65-year-old male called emergency medical services for progressive exertional dyspnea and fatigue over the previous four days, culminating on the day of admission in a transient episode of severe dyspnea, chest pain, peripheral cyanosis, and mottled, cold skin, with an oxygen saturation (SpO₂) of 76%. Upon arrival at the Emergency Department, his vital signs were within normal limits: SpO₂ 98% on room air, heart rate 108 bpm (sinus tachycardia), and blood pressure 139/104 mmHg. His past medical history included an ischemic stroke without residual deficits, chronic venous insufficiency with prior varicose vein surgery, and no other known cardiovascular or respiratory disease. Chronic home medication consisted of Aspirin (Aspenter®), Atorvastatin (Atoris®), Pentoxifylline, and Diosmin-Hesperidin (Detralex®). Comprehensive physical examination across all systems revealed no abnormal clinical findings at presentation.

3.2. Diagnostic Findings

The electrocardiogram (ECG) performed upon admission showed sinus rhythm at 100 bpm, a biphasic P wave in lead V₁, an S₁Q₃ pattern, prominent P waves in leads II and III (“P pulmonale”), and signs of acute right ventricular overload with anterior T-wave inversions.

Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.437, PaCO₂ 20.9 mmHg, PaO₂ 86.8 mmHg, SaO₂ 95%, lactate 6 mmol/L, BE −10.1 mmol/L, HCO₃⁻ 14.27 mmol/L, A–a DO₂ 31.7 mmHg, a/A ratio 0.7, and PaO₂/FiO₂ = 415 (O₂Hb 92.5%). The results indicate a mixed acid–base disorder, consisting of lactic metabolic acidosis and concomitant respiratory alkalosis, with a near-normal pH (= 7.44) reflecting partial compensation between the two opposing mechanisms. Overall oxygenation was preserved at the time of sampling (PaO₂/FiO₂ = 415), however, a mildly increased alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient (A–a DO₂) suggested a ventilation–perfusion mismatch, consistent with a suspected pulmonary embolism.

Complete blood count revealed leukocytosis (15.400/µL) with neutrophilia (11.270/µL), and a high-sensitivity C-reactive protein exceeding 30 mg/L. Biochemical testing revealed hepatic cytolysis with liver enzyme levels approximately twice the upper normal limit, incipient renal impairment (creatinine 1.70 mg/dL, urea 87 mg/dL) associated with reduced glomerular filtration rate, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH = 521 U/L), findings suggestive of systemic circulatory insufficiency with impaired tissue oxygenation.

Cardiac biomarkers revealed a markedly positive D-dimer (3.76 µg/mL), which, while nonspecific, could not rule out active thrombosis and raised suspicion for venous thromboembolism or other acute prothrombotic states. Myocardial injury was indicated by elevated Troponin I (119 ng/mL), a finding that may reflect right ventricular strain secondary to pulmonary embolism, but could also occur in acute coronary syndromes or myocarditis. The severity of ventricular wall stress was further supported by a markedly increased NT-proBNP level (15.136 pg/mL), consistent with acute ventricular overload and pressure elevation.

The assessment of clinical probability for pulmonary embolism using standardized risk scores revealed discordant results. Wells’ criteria yielded a score of 1.5 points, classifying the patient in the low-risk group, corresponding to an estimated 1.3% probability of PE in an Emergency Department population. In contrast, the revised Geneva score revealed a total of 6 points, placing the patient in the moderate-risk group, with an estimated 20–30% incidence of PE.

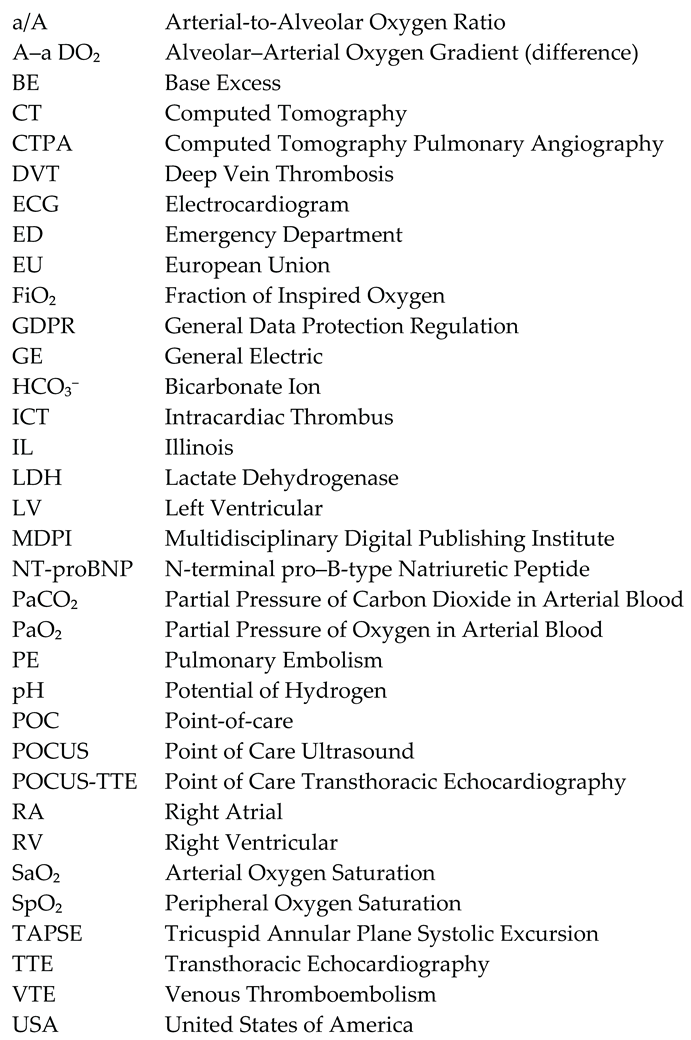

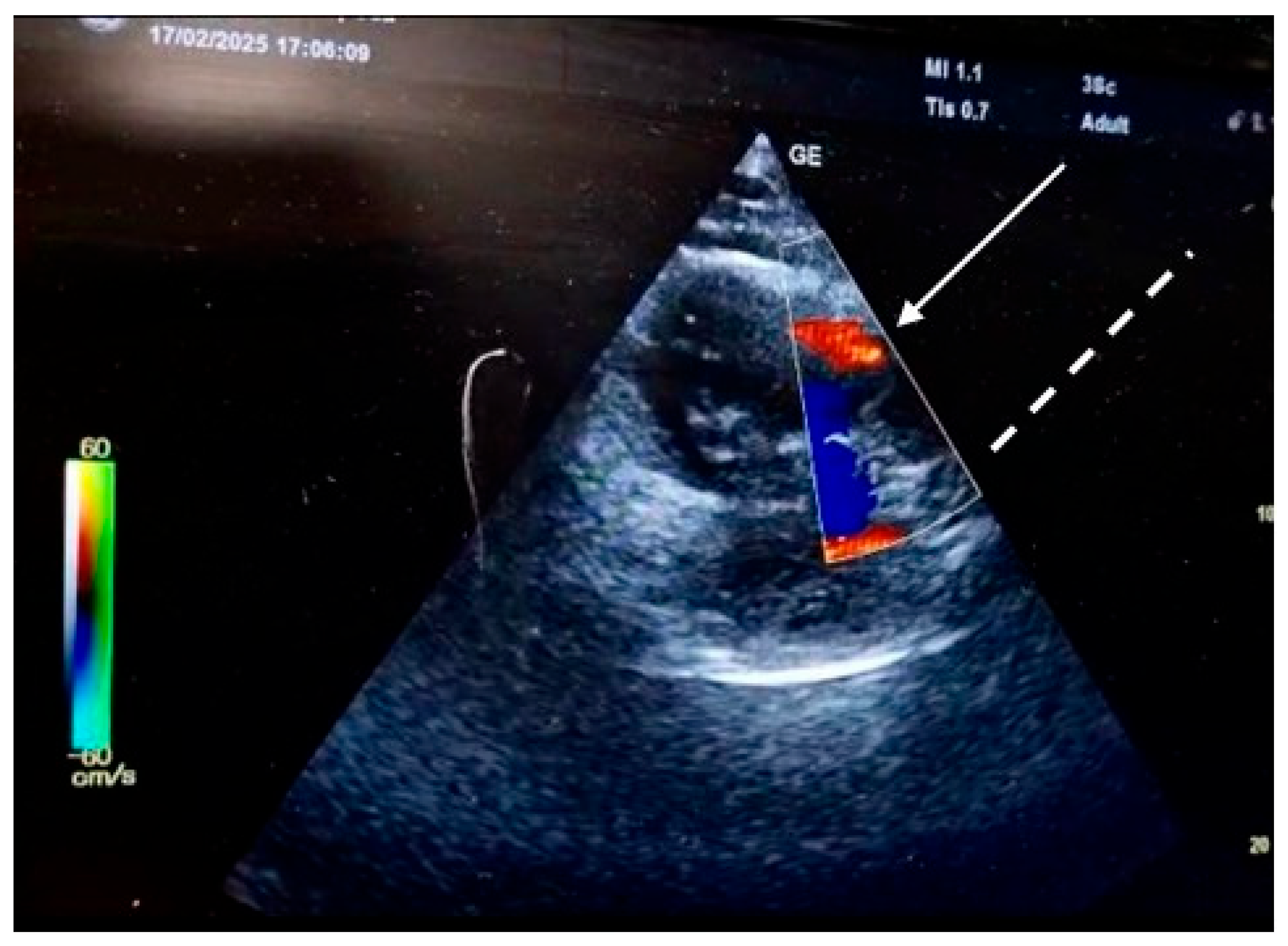

In the absence of any anamnestic or clinical evidence suggestive of pulmonary or myocardial infection (rapid influenza A/B and COVID-19 tests were also negative), acute myocardial infarction, or aortic dissection, and considering the laboratory findings, the clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism became increasingly prominent, prompting the immediate performance of transthoracic echocardiography. Point-of-care transthoracic echocardiography (POCUS-TTE) confirmed the physiological impact of acute right ventricular strain (

Figure 1A and

Figure 1B), demonstrating severe right ventricular dilation (46 mm below the tricuspid annulus), markedly reduced systolic function (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, TAPSE = 12 mm), and paradoxical interventricular septal motion resulting in a “D-shaped” left ventricle - findings consistent with acute right ventricular pressure overload (RV/RA gradient = 40 mmHg) (

Figure 2). Crucially, a large, highly mobile, serpentine thrombus was visualized within the right atrium, with its free-floating end prolapsing toward the tricuspid valve orifice

. The concomitant presence of asymptomatic left popliteal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was also documented, with the thrombus exhibiting a non-adherent proximal end and an unstable, mobile pattern, further supporting the diagnosis of massive pulmonary embolism

.

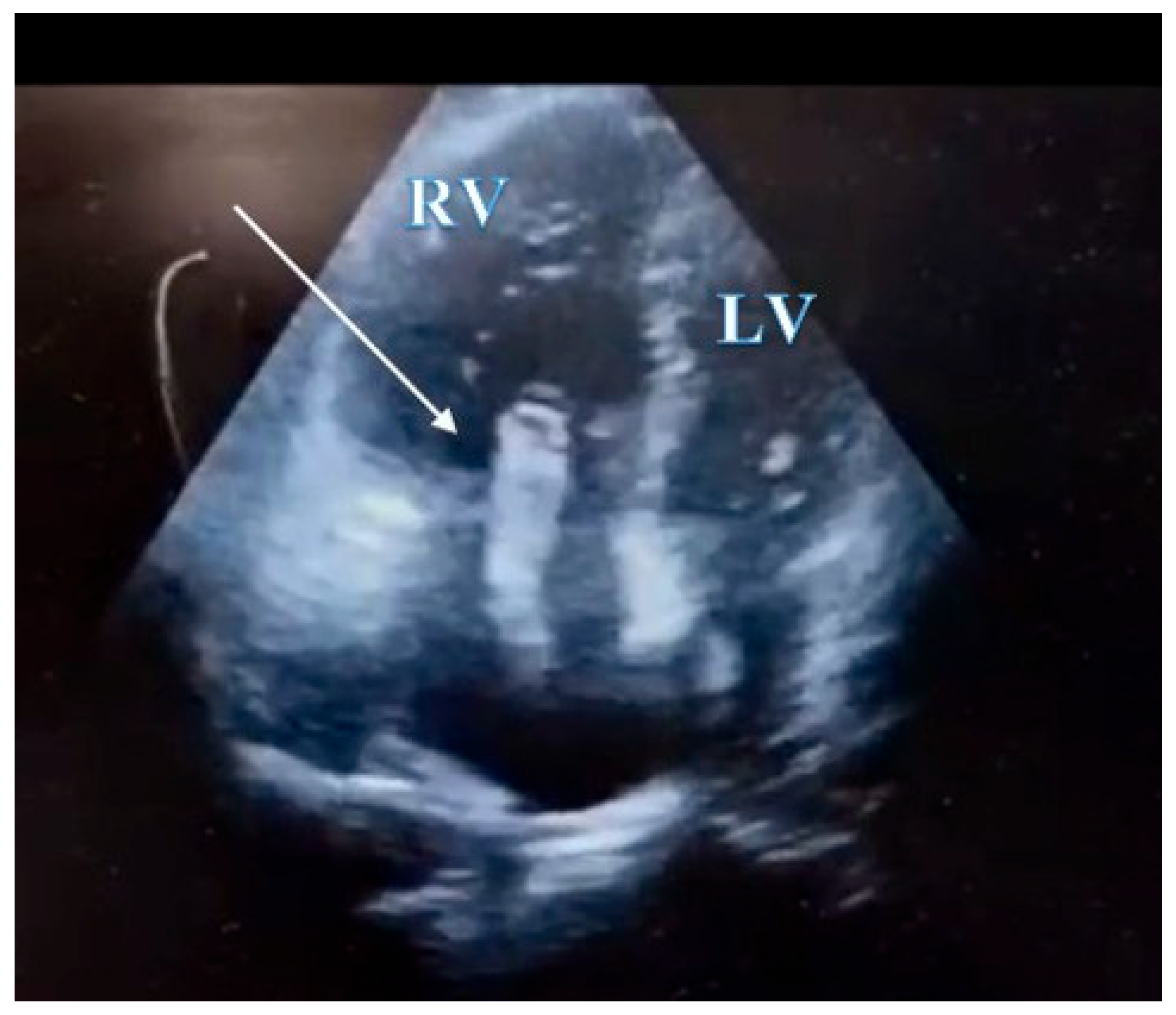

Given that the therapeutic decision depended on the presence or absence of pulmonary embolism and on the extent of vascular involvement secondary to thrombosis, and taking into account the patient’s hemodynamic stability, a pulmonary Computed Tomography (CT) angiography (CTPA) was performed. CTPA revealed a massive pulmonary embolism with extensive bilateral clot burden, confirming the underlying diagnosis, at a much more extensive level than initially anticipated by the medical team (

Figure 3).

3.3. Therapeutic Management and Outcome

In light of the extreme risk associated with the mobile intracardiac thrombus (ICT) and the high thrombotic burden of pulmonary embolism, the decision was made to bypass delayed interventions (surgical or catheter-based embolectomy) and to initiate rapid full-dose systemic thrombolysis (Alteplase 100 mg administered over 2 hours, the patient weighing more than 65 kg) directly in the Emergency Department, under continuous respiratory and hemodynamic monitoring (we mention the absence of absolute and relative contraindications to the administration of fibrinolytic therapy).

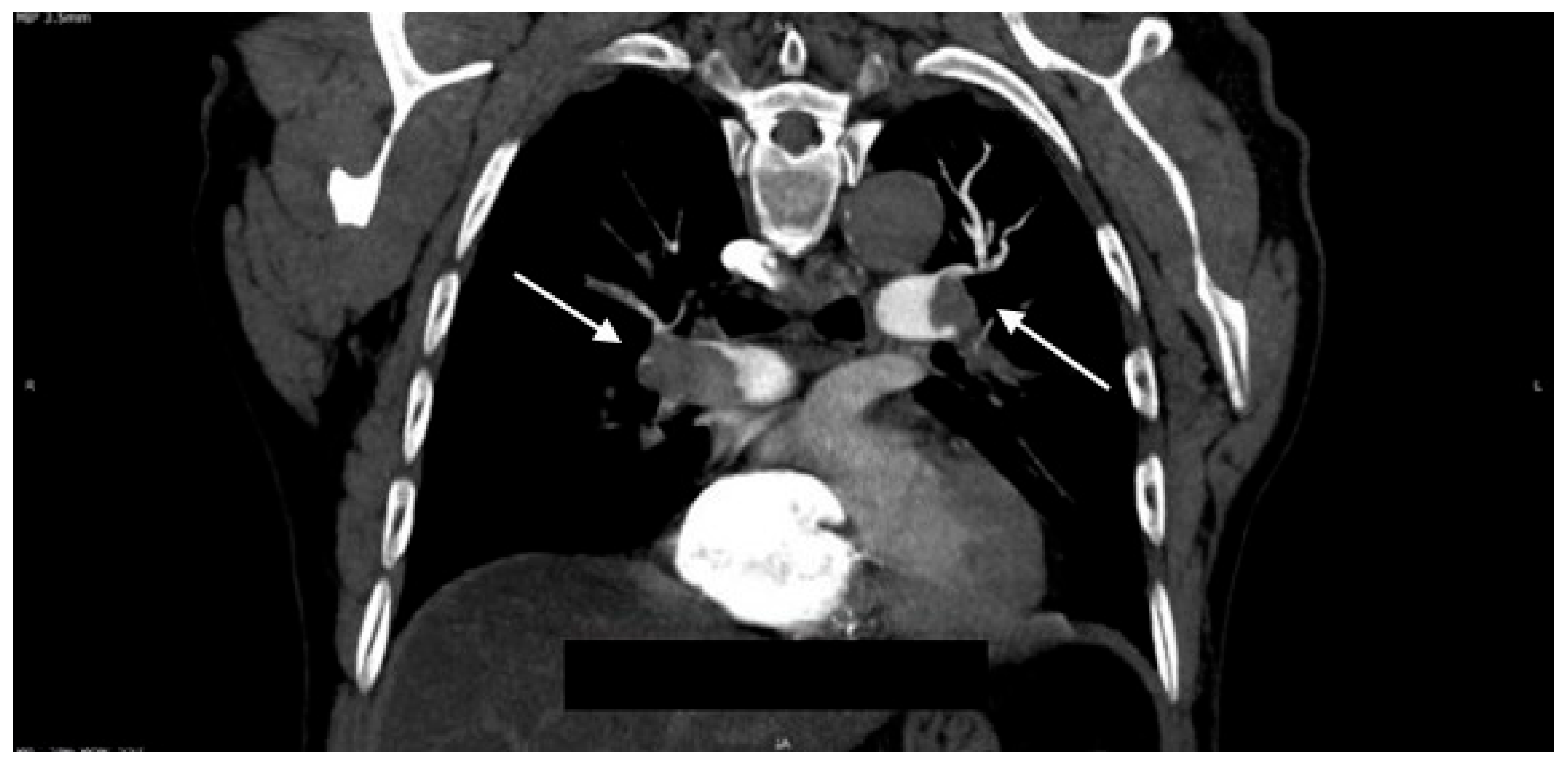

Safety surveillance during and immediately after the infusion confirmed the absence of major bleeding complications, with specific exclusion of intracranial hemorrhage. A follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram performed two hours after thrombolysis initiation confirmed the primary therapeutic endpoint - complete resolution of the mobile right atrial thrombus. Additionally, there was evidence of partial reversal of right ventricular pressure overload, demonstrated by a reduction of the RV/RA gradient from 40 mmHg to 28 mmHg (

Figure 4).

The patient was subsequently transitioned to oral anticoagulation with a Factor Xa inhibitor (Apixaban) for a planned six-month course and referred for comprehensive hematological evaluation to investigate possible underlying thrombophilia or other prothrombotic conditions.

4. Discussion

The management of acute pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a major clinical challenge, particularly when complicated by a mobile right atrial thrombus (thrombus in transit), a condition associated with an exceptionally high risk of mortality if left untreated [

3,

6]. The presence of such a thrombus indicates ongoing embolization and represents an extreme-risk anatomical phenotype, even in patients who initially present as hemodynamically stable. Reported mortality rates for untreated right-heart thrombi range from 27% to over 80%, underscoring the urgency of immediate recognition and intervention [

6,

9].

In the present case, the diagnostic process was notably complex due to the atypical and transient clinical presentation, which consisted of nonspecific symptoms such as progressive exertional dyspnea and fatigue, without overt hemodynamic or respiratory failure. Such paucisymptomatic profiles are not uncommon in submassive or intermediate-high–risk PE and can easily lead to a superficial diagnostic approach or initial misdiagnosis (e.g., pneumonia, heart failure, or anxiety-related dyspnea), delaying the initiation of potentially life-saving therapy. The combination of elevated but nonspecific biomarkers (Troponin, NT-proBNP, D-dimers) and subtle clinical findings emphasized the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and proceeding to early imaging.

In this context, POC transthoracic echocardiography (POCUS-TTE) proved to be a pivotal diagnostic tool, providing immediate, bedside evidence of severe right ventricular (RV) dilation and dysfunction, along with the visualization of a large, highly mobile intracardiac thrombus prolapsing through the tricuspid valve. This single finding was highly suggestive of an active embolic process, prompting urgent CT pulmonary angiography, which confirmed a massive bilateral thromboembolic burden. Emergency POC echocardiographic detection of a mobile right atrial thrombus is among the most specific and prognostically significant findings in acute PE, as it identifies an ongoing source of emboli and predicts imminent hemodynamic collapse. Several studies have demonstrated that right-heart thrombi are independently associated with increased mortality, regardless of initial blood pressure values [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Therefore, POC echocardiography serves not only as a diagnostic but also as a prognostic and decision-shaping tool, especially in the Emergency Department setting, where time-sensitive decisions are crucial [

9,

10,

11].

Our therapeutic approach diverged from the strategies employed in major clinical trials evaluating thrombolytic therapy in PE. The MOPETT trial [

12] investigated half-dose Alteplase (50 mg) in moderate PE and demonstrated a significant reduction in pulmonary hypertension and recurrence rates, without an increased risk of major bleeding. Conversely, the PEITHO trial [

13] used full-dose Tenecteplase in hemodynamically stable patients with RV dysfunction and elevated cardiac biomarkers, showing fewer episodes of hemodynamic decompensation but a higher rate of major hemorrhage, including intracranial bleeding.

However, neither of these trials specifically addressed patients with mobile intracardiac thrombi, where the embolic risk is dynamic and potentially catastrophic. In our case, the presence of a large, serpentine, free-floating right atrial thrombus represented an extreme-risk anatomical scenario, justifying immediate reperfusion therapy despite preserved hemodynamics. Consequently, we administered full-dose systemic thrombolysis (Alteplase 100 mg over 2 hours) directly in the Emergency Department, under continuous monitoring.

Our decision contrasts with the dosing regimens used in several recent observational studies, including the work by Ömer Selim Unat et al. [

14], where half-dose Alteplase (50 mg) was employed in intermediate-high–risk PE, yielding favorable outcomes without major bleeding complications. Nonetheless, data remain limited regarding full-dose thrombolysis in hemodynamically stable patients with an intracardiac thrombus.

To our knowledge, the present case represents the

first reported instance of full-dose, emergency department–initiated Alteplase administration in a hemodynamically stable and paucisymptomatic patient with intermediate–high-risk pulmonary embolism and a mobile right atrial thrombus. A review of the available literature identified only

three previously published

cases of thrombolytic therapy in patients with pulmonary embolism and intracardiac thrombi-

two involving

hemodynamically unstable patients [

15,

16] and

one describing a

hemodynamically stable but symptomatic case with recurrent syncopal episodes [

17].

The clinical evolution strongly supports the safety and efficacy of this approach: the thrombus completely resolved within two hours post-thrombolysis, accompanied by significant improvement in RV function (RV/RA gradient decreased from 40 mmHg to 28 mmHg), without any hemorrhagic complications, including intracranial bleeding. These outcomes emphasize that, in selected patients, early full-dose systemic thrombolysis can be both feasible and effective when guided by clear anatomical and echocardiographic criteria rather than blood pressure alone.

Moreover, the feasibility of performing full-dose systemic thrombolysis directly in the Emergency Department is an important procedural message. This approach minimizes the critical door-to-needle time, prevents thrombus fragmentation and fatal embolization, and enables early hemodynamic stabilization. When performed under rigorous monitoring by an experienced emergency and cardiology team, the risk of major complications remains acceptably low.

Finally, the patient’s transition to oral anticoagulation with a Factor Xa inhibitor (Apixaban) and referral for comprehensive hematological assessment ensured adequate secondary prevention and allowed for investigation of an underlying prothrombotic state, given the patient’s prior ischemic stroke and chronic venous insufficiency. Identifying such predispositions is critical for long-term management and recurrence prevention.

In summary, this case highlights several key learning points: 1. Nonspecific clinical presentations should not exclude the diagnosis of potentially life-threatening PE; 2. Point-of-care echocardiography is an indispensable diagnostic and prognostic tool in the Emergency Department, capable of revealing RV dysfunction and mobile thrombi before hemodynamic collapse occurs; 3. Immediate, full-dose systemic thrombolysis can be justified in anatomically extreme-risk cases, even in the absence of hypotension, provided that the procedure is performed in a controlled, closely monitored environment.

5. Conclusions

A mobile right atrial thrombus complicating massive pulmonary embolism constitutes a true cardiovascular emergency, even in the absence of systemic hypotension or shock. This case demonstrates that point-of-care ultrasonography, combined with prompt full-dose systemic thrombolysis initiated directly in the Emergency Department, can be both feasible and life-saving in selected patients with intermediate-high–risk PE and extreme-risk anatomical features. Although current guidelines do not formally endorse thrombolysis for intermediate-high–risk PE, this experience supports an individualized approach guided by real-time echocardiographic and anatomical findings rather than hemodynamic parameters alone. Early diagnosis through emergency POC echocardiography, rapid initiation of reperfusion therapy, and comprehensive post-thrombolytic follow-up are essential components of optimal management aimed at improving survival and preventing recurrence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. 1. Cardiology Consultation, 2. CT Pulmonary Angiography findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Adela Golea and Raluca M. Tat; methodology, Raluca M. Tat, Adela Golea and Ștefan C. Vesa; software, Ștefan C. Vesa; validation, Adela Golea, Mirela Stoia and Ștefan C. Vesa; resources, Raluca M. Tat and Carina Adam; data curation, Raluca M. Tat and Adela Golea; writing—original draft preparation, Adela Golea and Raluca M. Tat; writing—review and editing, Sonia Luka, Carina Adam and Ștefan C. Vesa; visualization, Mirela Stoia and Sonia Luka; supervision, Raluca M. Tat and Adela Golea; project administration, Raluca M. Tat and Adela Golea; funding acquisition, Ștefan C. Vesa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this case report, as it describes a single patient’s clinical course and management without any experimental intervention. This is consistent with institutional policy and international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient provided informed consent for the publication of anonymized clinical data and images.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report, including all relevant clinical information and imaging data.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the preparation of this manuscript are included in the publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all patients who have expressed their willingness to contribute to medical research and thereby support the advancement of clinical knowledge.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Rokosh, R.S.; Ranganath, N.; Yau, P.; Rockman, C.; Sadek, M.; Berland, T.; Jacobowitz, G.; Berger, J.; Maldonado, T.S. High Prevalence and Mortality Associated with Upper Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis in Hospitalized Patients at a Tertiary Care Center. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 65, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, C.R.; Baciewicz, F.A. Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathophysiology of Pulmonary Embolism. Int. J. Angiol. 2024, 33, 076–081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinides, S.V.; Meyer, G.; Becattini, C.; Bueno, H.; Geersing, G.J.; Harjola, V.-P.; Huisman, M.V.; Humbert, M.; Jennings, C.S.; Jiménez, D.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 543–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, K.; D’aRsigny, C.L. Risk stratification of acute pulmonary embolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 3016–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishna, A.M.; Reddi, V.; Belford, P.M.; Alvarez, M.; Jaber, W.A.; Zhao, D.X.; Vallabhajosyula, S. Intermediate-Risk Pulmonary Embolism: A Review of Contemporary Diagnosis, Risk Stratification and Management. Medicina 2022, 58, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Martínez LE, Uriona Villarroel JE, Exaire Rodríguez JE, Mendoza D, Martínez Guerra ML, Pulido T, Bautista E, Castañón A, Sandoval J. Tromboembolia pulmonar masiva, trombo en tránsito y disfunción ventricular derecha [Massive pulmonary embolism, thrombus in transit, and right ventricular dysfunction]. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2007 Jan-Mar;77(1):44-53. Spanish. [PubMed]

- Pappas, A.J.; Knight, S.W.; McLean, K.Z.; Bork, S.; Kurz, M.C.; Sawyer, K.N. Thrombus-in-Transit: A Case for a Multidisciplinary Hospital-Based Pulmonary Embolism System of Care. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 51, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.L.D.; Salah, Z.; Halpern, N.A.M. Intracardiac Thrombus in Transit Detected by Point-of-Care Ultrasound. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2022, 45, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, A.; Farooqui, S.M.; Hussain, S.T.; Vandyck, K. Right heart thrombus in transit: Raising bar in the management of cardiac arrest. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 41, 101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterwalder, J.; Polyzogopoulou, E.; Hoffmann, B. Point-of-Care Ultrasound—History, Current and Evolving Clinical Concepts in Emergency Medicine. Medicina 2023, 59, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alerhand, S.; Sundaram, T.; Gottlieb, M. What are the echocardiographic findings of acute right ventricular strain that suggest pulmonary embolism? Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2021, 40, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, M.; Bay, C.; Skrocki, L.; Rahimi, F.; Mehdipour, M. Moderate Pulmonary Embolism Treated With Thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2013, 111, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, G.; Vicaut, E.; Danays, T.; Agnelli, G.; Becattini, C.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Bluhmki, E.; Bouvaist, H.; Brenner, B.; Couturaud, F.; et al. Fibrinolysis for Patients with Intermediate-Risk Pulmonary Embolism. New Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1402–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unat, Ö.S.S.; Korkmaz, P.; Çinkooğlu, A.; Can, Ö.; Soydan, E.; Bayraktaroğlu, S.; Çok, G.; Savaş, R.; Akarca, F.K.; Nalbantgil, S.; et al. Comparison of half-dose alteplase and LMWH in intermediate-high risk pulmonary embolism: a single-center observational study. Egypt. Hear. J. 2025, 77, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, K.; Negi, P.; Asotra, S.; Dev, M. Right atrial free-floating thrombus in a patient with acute pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, P.G.; Hegde, N.N.; Shah, S. Thrombus-in-transit involving all four chambers of the heart in a patient presenting with acute pulmonary embolism. J. Cardiol. Cases 2022, 26, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Rodrigo, A.; Martín-Torres, J.M.; Cano-Carratalá, S. Free-floating thrombus in transit in a patient with recurrent syncope. Emergencias 2025, 33, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).