Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Instruments

2.2. Synthesis of Triterpenoids Derivatives

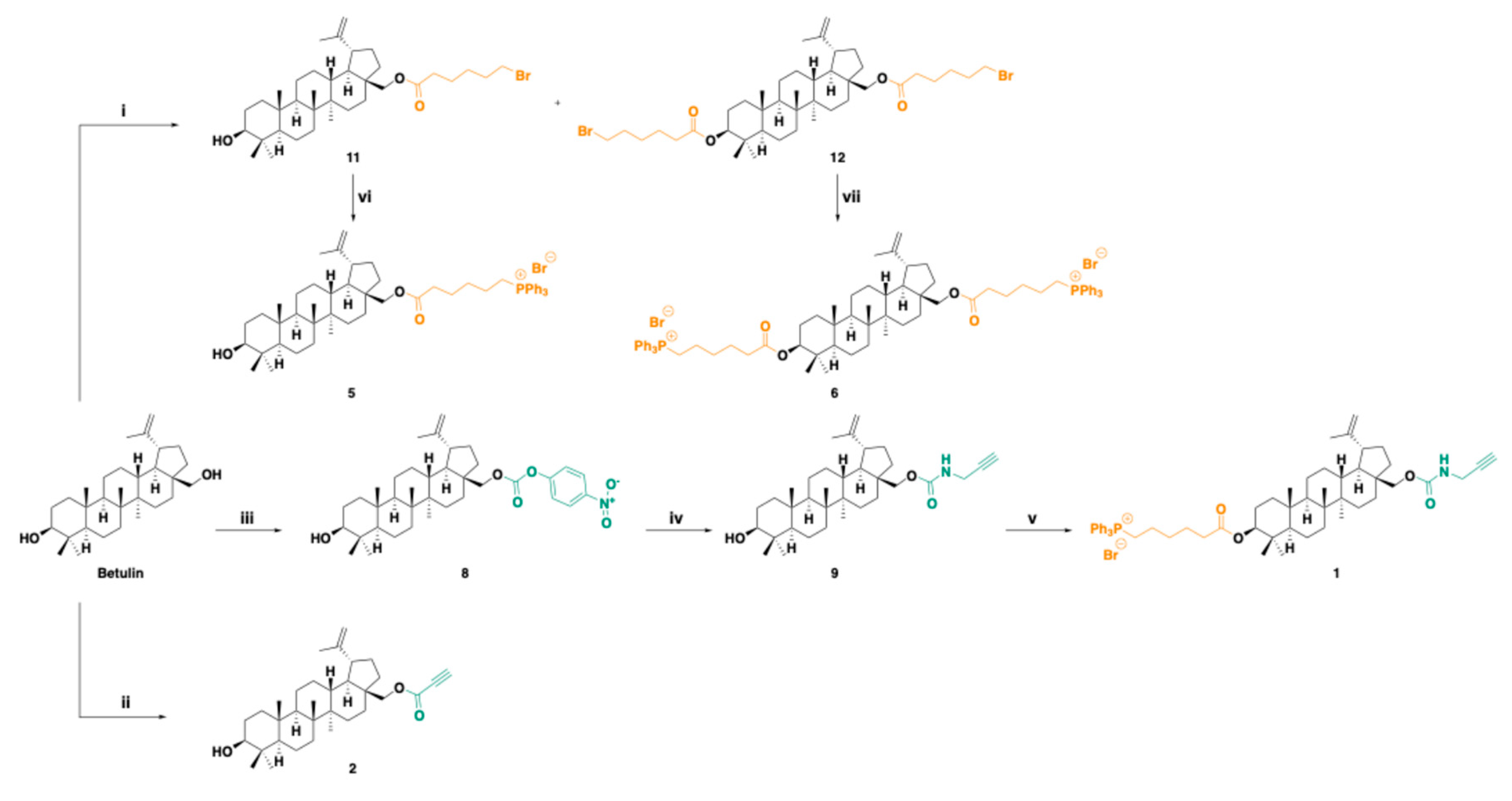

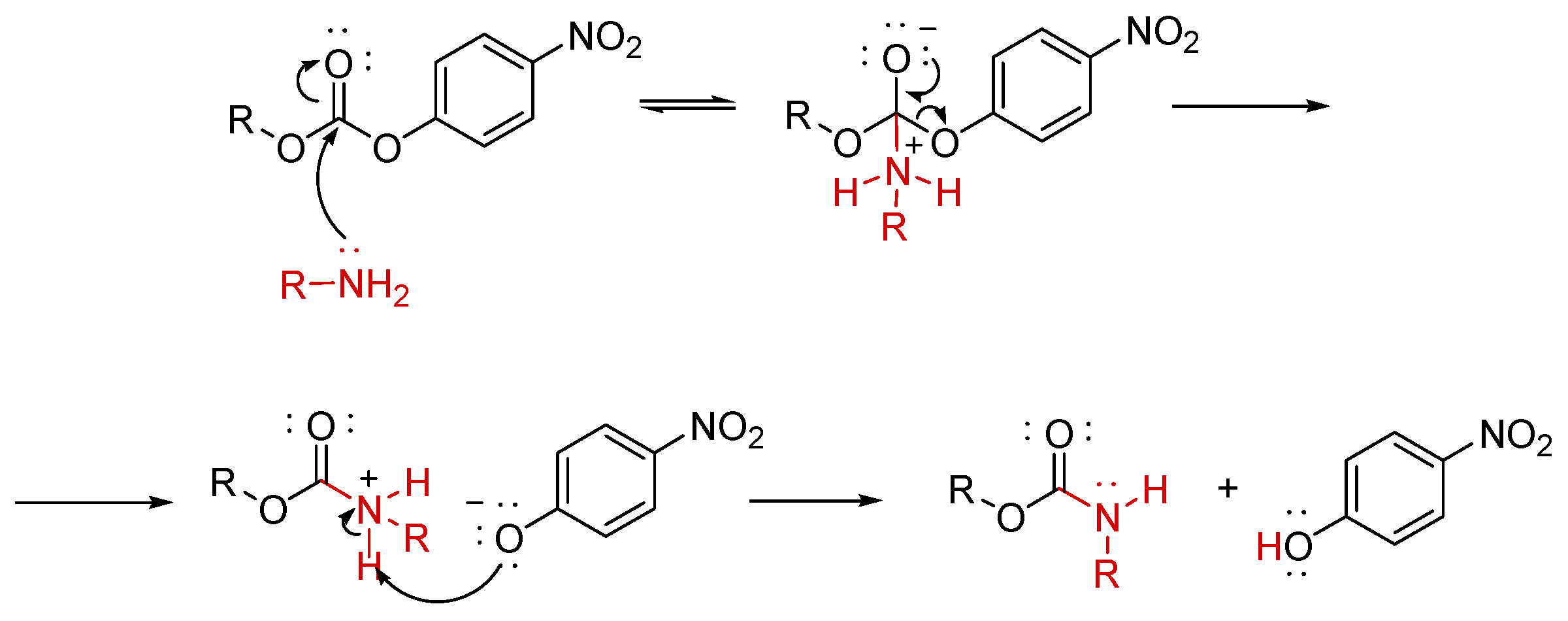

2.2.1. Synthesis of Betulin (BET) Derivatives

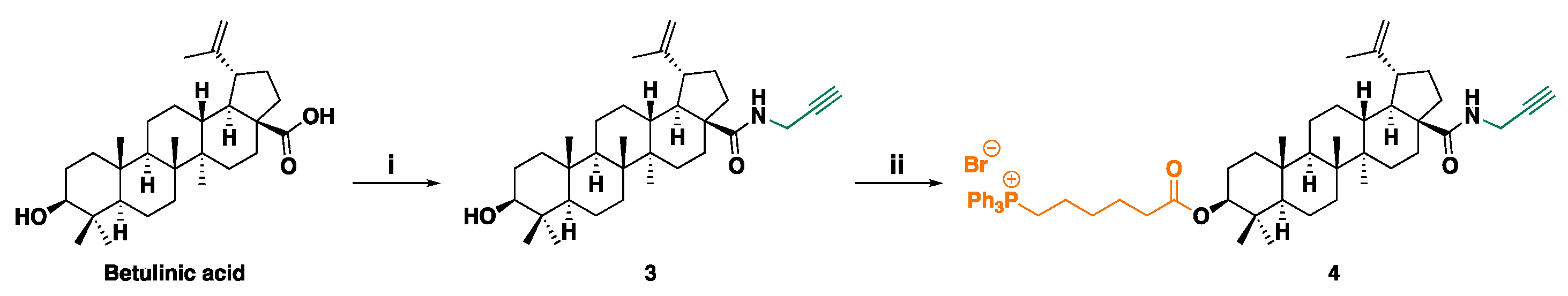

2.2.2. Synthesis of Betulinic Acid (BA) Derivatives

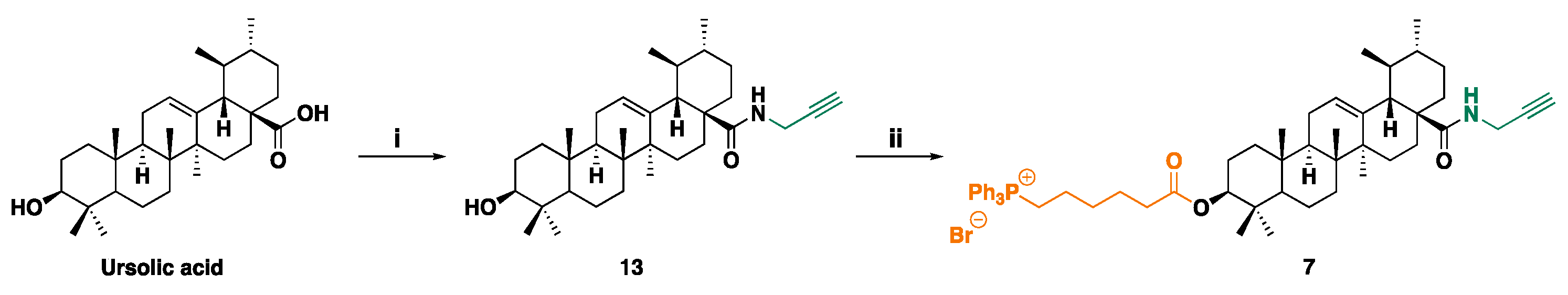

2.2.3. Synthesis of Ursolic Acid (UA) Derivatives

2.3. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy of BA, BET, UA and Compounds 1-7

2.4. Multivariate Analysis of ATR-FTIR and 13C NMR Spectral Data

2.4.1. ATR-FTIR Spectral Data

2.5. Potentiometric Titrations of Compound 1 and 4-7

2.5.1. Preparation of a 0.1 M Perchloric Acid Volumetric Solution

2.6. Optical Microscopy Analyses

2.7. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Analysis

2.8. Microbiology

2.8.1. Microorganisms

2.8.2. Determination of the MICs

3. Results and Discussion

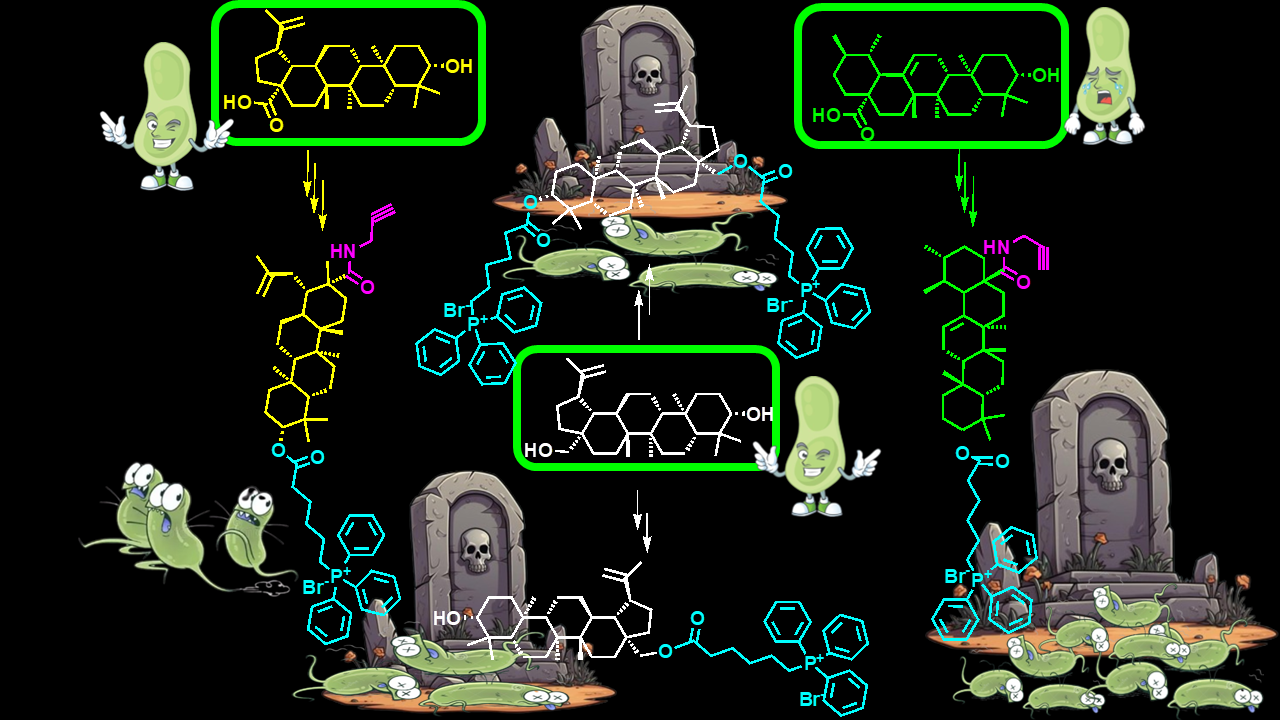

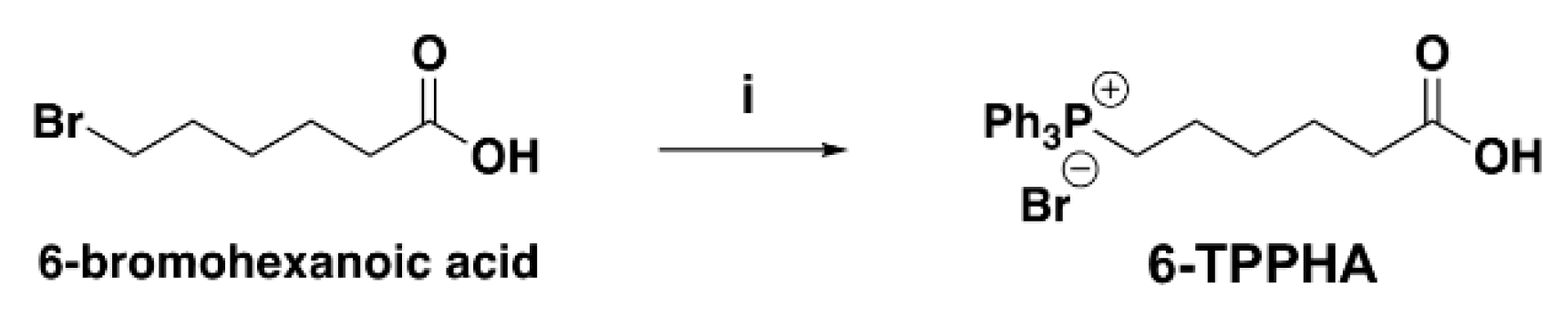

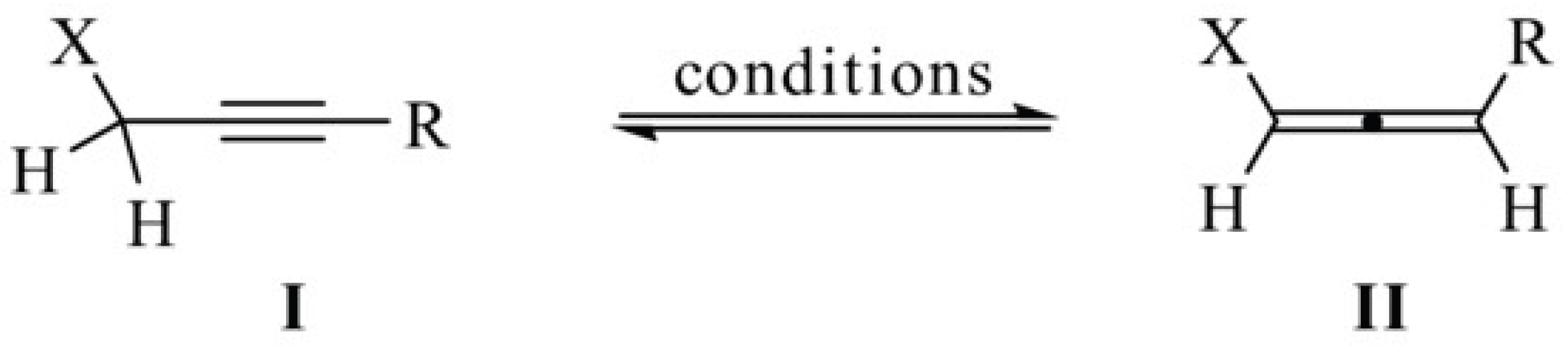

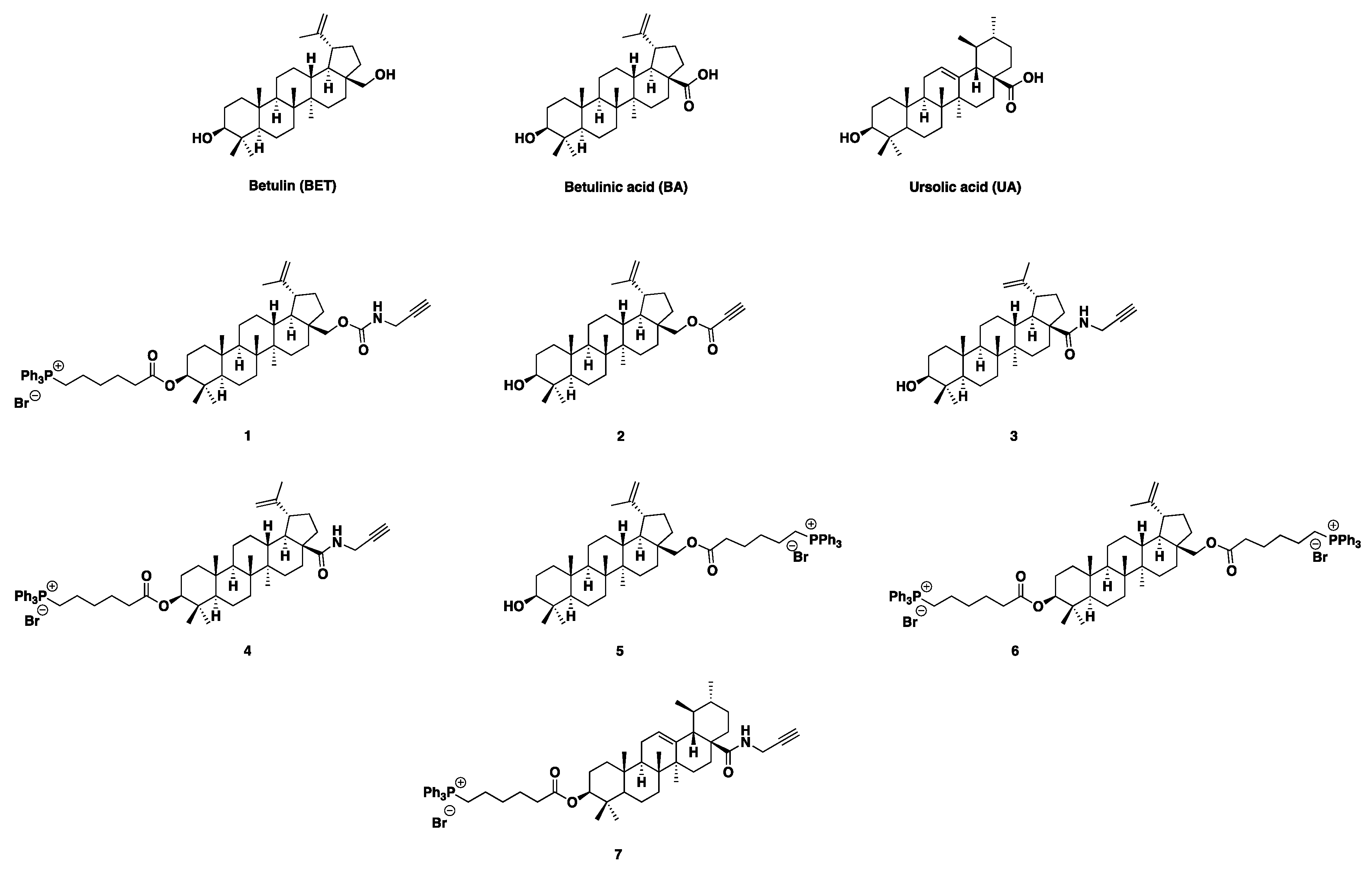

3.1. Synthesis of Triterpenoids Derivatives

3.1.1. Synthesis of BET Derivatives

3.1.2. Synthesis of BA Derivatives

3.1.3. Synthesis of UA Derivatives

3.2. ATR-FTIR Spectra of BA, BET, UA and Compounds 1-7

3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of ATR-FTIR and 13C NMR Spectral Data

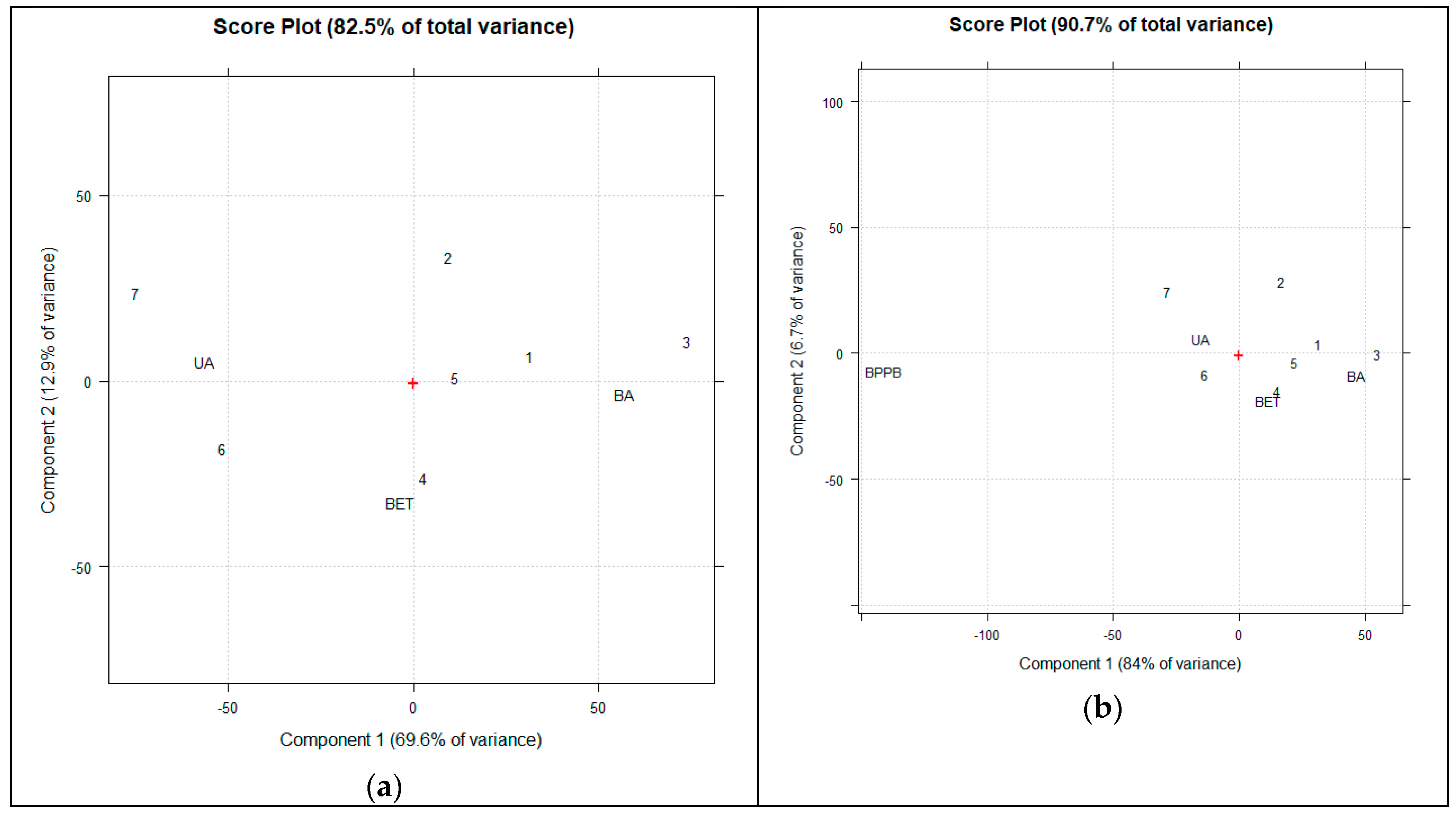

3.3.1. PCA of ATR-FTIR Spectral Data

3.3.2. PCA of 13C NMR Spectral Data

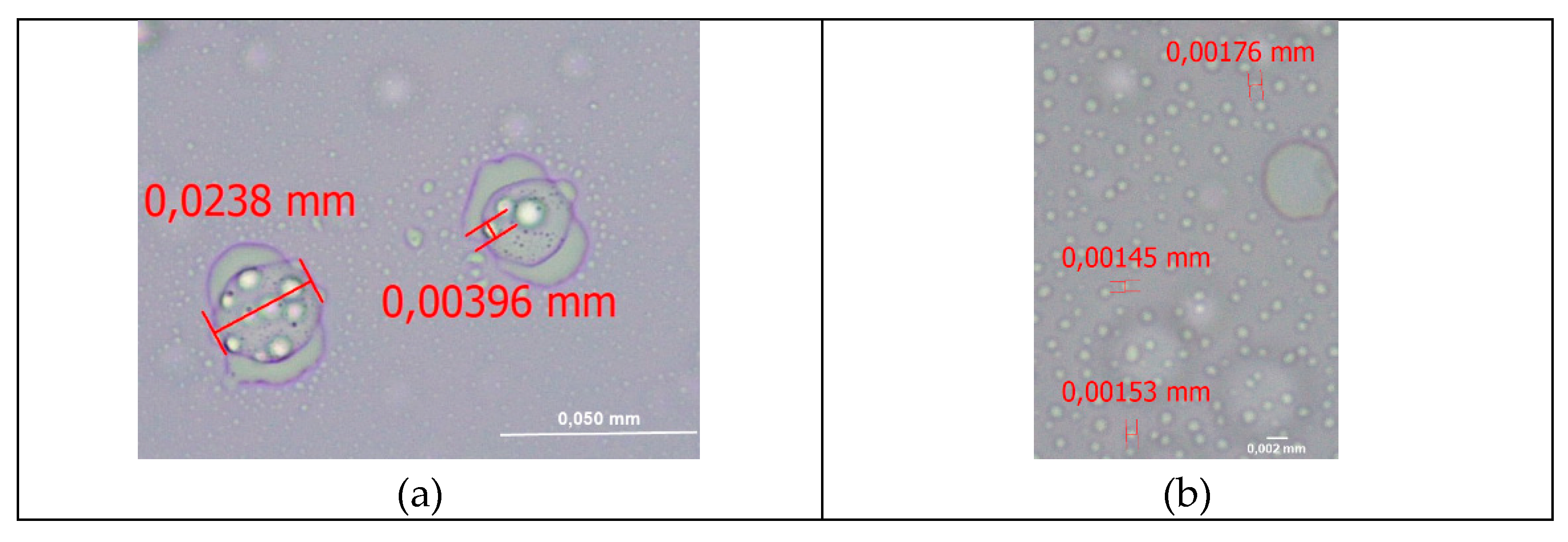

3.4. Optical Microscopy Analyses

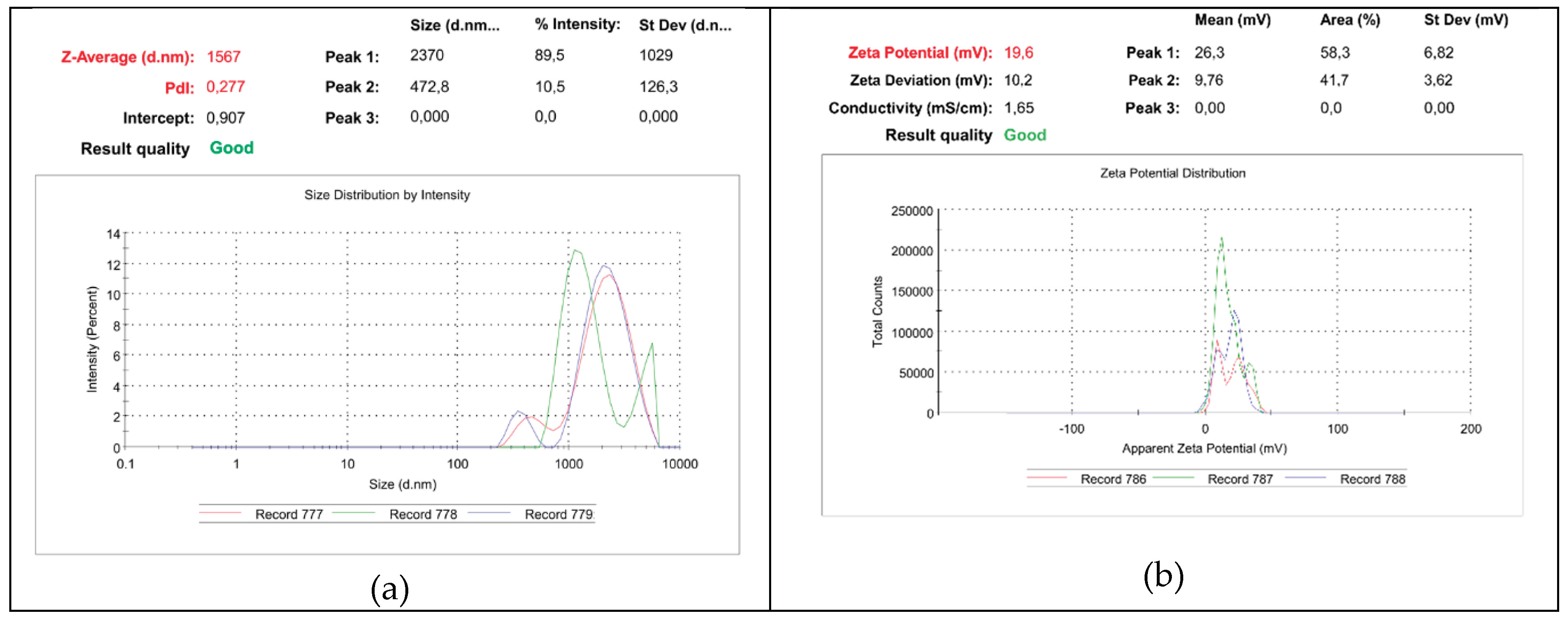

3.5. Particle Size, ζ-p, and PDI of 6

3.6. Non-Aqueous Potentiometric Titration of Compounds 1 and 4-7

3.7. Antibacterial Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandrasekhar, D.; Joseph, C.M.; parambil, J.C.; Murali, S.; Yahiya, M.; K, S. Superbugs: An Invicible Threat in Post Antibiotic Era. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R. Superbug Infection. J Drug Metab Toxicol 2018, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicky, P.-H.; Poiraud, J.; Alves, M.; Patrier, J.; d’Humières, C.; Lê, M.; Kramer, L.; de Montmollin, É.; Massias, L.; Armand-Lefèvre, L.; et al. Cefiderocol Treatment for Severe Infections Due to Difficult-to-Treat-Resistant Non-Fermentative Gram-Negative Bacilli in ICU Patients: A Case Series and Narrative Literature Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.H.; Khare, K.; Saxena, P.; Debnath, P.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Yadav, D. A Review on Colistin Resistance: An Antibiotic of Last Resort. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.T.; López-Medrano, F. Cefiderocol, a New Antibiotic against Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Rev Esp Quimioter 2021, 34 Suppl 1, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakonstantis, S.; Rousaki, M.; Kritsotakis, E.I. Cefiderocol: Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Resistance, Heteroresistance and In Vivo Emergence of Resistance. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Zuccari, G.; Bacchetti, F.; Torazza, C.; Milanese, M.; Siciliano, C.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Piatti, G.; Schito, A.M. Synthesized Bis-Triphenyl Phosphonium-Based Nano Vesicles Have Potent and Selective Antibacterial Effects on Several Clinically Relevant Superbugs. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajic, I.; Tomic, N.; Lukovic, B.; Jovicevic, M.; Kekic, D.; Petrovic, M.; Jankovic, M.; Trudic, A.; Mitic Culafic, D.; Milenkovic, M.; et al. A Comprehensive Overview of Antibacterial Agents for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria: The Current Landscape, Development, Future Opportunities, and Challenges. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Molecular Bioscience Explainer: What Is a Superbug and Why Should We Be Worried?; Australia, 2017.

- García-Solache, M.; Rice, L.B. The Enterococcus: A Model of Adaptability to Its Environment. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitus, M.; Rewane, A.; Perera, T.B. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci; 2024.

- Chiang, H.-Y.; Perencevich, E.N.; Nair, R.; Nelson, R.E.; Samore, M.; Khader, K.; Chorazy, M.L.; Herwaldt, L.A.; Blevins, A.; Ward, M.A.; et al. Incidence and Outcomes Associated With Infections Caused by Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci in the United States: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017, 38, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Murray, B.E.; Rice, L.B.; Arias, C.A. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2016, 30, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Hidalgo, N.; Escolà-Vergé, L. Enterococcus Faecalis Bacteremia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 74, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, T.F.; Coelho, S.S.; Foletto, V.S.; Bottega, A.; Serafin, M.B.; Machado, C. de S.; Franco, L.N.; Paula, B.R.; Hörner, R. Alternatives for the Treatment of Infections Caused by ESKAPE Pathogens. J Clin Pharm Ther 2020, 45, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Brullo, C.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, A.M. Pyrazole-Based Water-Soluble Dendrimer Nanoparticles as a Potential New Agent against Staphylococci. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdogan, B. Antibacterial Susceptibility of a Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Strain Isolated at the Hershey Medical Center. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2003, 52, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiodras, S.; Gold, H.S.; Sakoulas, G.; Eliopoulos, G.M.; Wennersten, C.; Venkataraman, L.; Moellering, R.C.; Ferraro, M.J. Linezolid Resistance in a Clinical Isolate of Staphylococcus Aureus. The Lancet 2001, 358, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peykov, S.; Kirov, B.; Strateva, T. Linezolid in the Focus of Antimicrobial Resistance of Enterococcus Species: A Global Overview of Genomic Studies. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bayer, A.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Daum, R.S.; Fridkin, S.K.; Gorwitz, R.J.; Kaplan, S.L.; Karchmer, A.W.; Levine, D.P.; Murray, B.E.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Adults and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2011, 52, e18–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour El-Din, H.T.; Yassin, A.S.; Ragab, Y.M.; Hashem, A.M. Phenotype-Genotype Characterization and Antibiotic-Resistance Correlations Among Colonizing and Infectious Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Recovered from Intensive Care Units. Infect Drug Resist 2021, Volume 14, 1557–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Available online: Https://Www.Eucast.Org/Ast_of_bacteria/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Alfei, S.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, A.M. Synthesis, Characterization and Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal Effects of Ammonium Methyl and Ammonium Ethyl Styrene-Based Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Castellaro, S.; Taptue, G.B. Synthesis and NMR Characterization of Dendrimers Based on 2, 2-Bis-(Hydroxymethyl)-Propanoic Acid (Bis-HMPA) Containing Peripheral Amino Acid Residues for Gene Transfection. Organic Communications 2017, 10, 144–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Castellaro, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Polyester-Based Dendrimers Containing Peripheral Arginine or Mixed Amino Acids as Potential Vectors for Gene and Drug Delivery. Macromol Res 2017, 25, 1172–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Taptue, G.B.; Catena, S.; Bisio, A. Synthesis of Water-Soluble, Polyester-Based Dendrimer Prodrugs for Exploiting Therapeutic Properties of Two Triterpenoid Acids. Chinese Journal of Polymer Science 2018, 36, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifer, C.W.; Wollish, E.G. Potentiometric Titration of Salts of Organic Bases in Acetic Acid. Anal Chem 1952, 24, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Catena, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Fourth Generation Polyester-based Dendrimers with Cationic Amino Acids-modified Crown as Promising Water Soluble Biomedical Devices. Polym Adv Technol 2018, 29, 2735–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, F.; Schito, A.M.; Milanese, M.; Castellaro, S.; Alfei, S. Anti Gram-Positive Bacteria Activity of Synthetic Quaternary Ammonium Lipid and Its Precursor Phosphonium Salt. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlala, S.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Gondwe, M.; Oyedeji, O.O. Ursolic Acid and Its Derivatives as Bioactive Agents. Molecules 2019, 24, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, E.; Świtalska, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Bębenek, E. New Difunctional Derivatives of Betulin: Preparation, Characterization and Antiproliferative Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xie, Y.; Qi, J.; Ren, Z.; Coluccini, C.; Coghi, P. Development of New Amide Derivatives of Betulinic Acid: Synthetic Approaches and Structural Characterization. Molbank 2025, 2025, M2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csuk, R.; Barthel, A.; Sczepek, R.; Siewert, B.; Schwarz, S. Synthesis, Encapsulation and Antitumor Activity of New Betulin Derivatives. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2011, 344, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bębenek, E.; Chrobak, E.; Wietrzyk, J.; Kadela, M.; Chrobak, A.; Kusz, J.; Książek, M.; Jastrzębska, M.; Boryczka, S. Synthesis, Structure and Cytotoxic Activity of Acetylenic Derivatives of Betulonic and Betulinic Acids. J Mol Struct 2016, 1106, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemann, J.; Heller, L.; Perl, V.; Kluge, R.; Ströhl, D.; Csuk, R. Betulinic Acid Derived Hydroxamates and Betulin Derived Carbamates Are Interesting Scaffolds for the Synthesis of Novel Cytotoxic Compounds. Eur J Med Chem 2015, 106, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drag Betulinic Acid Exhibits Stronger Cytotoxic Activity on the Normal Melanocyte NHEM-Neo Cell Line than on Drug-Resistant and Drug-Sensitive MeWo Melanoma Cell Lines. Mol Med Rep 2009, 2. [CrossRef]

- Martins, W.K.; Gomide, A.B.; Costa, É.T.; Junqueira, H.C.; Stolf, B.S.; Itri, R.; Baptista, M.S. Membrane Damage by Betulinic Acid Provides Insights into Cellular Aging. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2017, 1861, 3129–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuco, V.; Supino, R.; Righetti, S.C.; Cleris, L.; Marchesi, E.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; Formelli, F. Selective Cytotoxicity of Betulinic Acid on Tumor Cell Lines, but Not on Normal Cells. Cancer Lett 2002, 175, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricovac, D.; Dehelean, C.A.; Pinzaru, I.; Mioc, A.; Aburel, O.-M.; Macasoi, I.; Draghici, G.A.; Petean, C.; Soica, C.; Boruga, M.; et al. Assessment of Betulinic Acid Cytotoxicity and Mitochondrial Metabolism Impairment in a Human Melanoma Cell Line. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, S.K.; Kiełbus, M.; Rivero-Müller, A.; Stepulak, A. Comprehensive Review on Betulin as a Potent Anticancer Agent. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordyjewska, A.; Ostapiuk, A.; Horecka, A.; Kurzepa, J. Betulin and Betulinic Acid: Triterpenoids Derivatives with a Powerful Biological Potential. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 18, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csuk, R. Targeting Cancer by Betulin and Betulinic Acid. In Novel Apoptotic Regulators in Carcinogenesis; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2012; pp. 267–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bildziukevich, U.; Kvasnicová, M.; Šaman, D.; Rárová, L.; Šlouf, M.; Wimmer, Z. Cytotoxicity and Nanoassembly Characteristics of Aromatic Amides of Oleanolic Acid and Ursolic Acid. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 20938–20948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, C.; Solairaja, S.; Dunna, N.R.; Venkatabalasubramanian, S. Toxicity, Safety, and Pharmacotherapeutic Properties of Ursolic Acid: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Perspectives against Lung Cancer. Curr Bioact Compd 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiolo, J.; Graikioti, D.G.; Barbieri, C.L.; Joray, M.B.; Antoniou, A.I.; Vera, D.M.A.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Carpinella, M.C. Novel Betulin Derivatives as Multidrug Reversal Agents Targeting P-Glycoprotein. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yin, F.; Hu, J.; Ju, Y. Cu 2+ -Triggered Shrinkage of a Natural Betulin-Derived Supramolecular Gel to Fabricate Moldable Self-Supporting Gel. Mater Chem Front 2021, 5, 4764–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boryczka, S.; Michalik, E.; Jastrzebska, M.; Kusz, J.; Zubko, M.; Bębenek, E. X-Ray Crystal Structure of Betulin–DMSO Solvate. J Chem Crystallogr 2012, 42, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmer, A.; Heinze, T. Reactive Norbornene- and Phenyl Carbonate-Modified Dextran Derivatives: A New Approach to Selective Functionalization. React Funct Polym 2025, 208, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, I.-H.; Kim, E.Y.; Park, H.-R.; Jeon, S.-E. Aminolyses of 4-Nitrophenyl Phenyl Carbonate and Thionocarbonate: Effect of Modification of Electrophilic Center from CO to CS on Reactivity and Mechanism. J Org Chem 2006, 71, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boryczka, S.; Bębenek, E.; Wietrzyk, J.; Kempińska, K.; Jastrzębska, M.; Kusz, J.; Nowak, M. Synthesis, Structure and Cytotoxic Activity of New Acetylenic Derivatives of Betulin. Molecules 2013, 18, 4526–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bębenek, E.; Jastrzębska, M.; Kadela-Tomanek, M.; Chrobak, E.; Orzechowska, B.; Zwolińska, K.; Latocha, M.; Mertas, A.; Czuba, Z.; Boryczka, S. Novel Triazole Hybrids of Betulin: Synthesis and Biological Activity Profile. Molecules 2017, 22, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, H.; Li, D.; Lou, H.; Fan, P. Mitochondria-Targeted Lupane Triterpenoid Derivatives and Their Selective Apoptosis-Inducing Anticancer Mechanisms. J Med Chem 2017, 60, 6353–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsepaeva, O.V.; Nemtarev, A.V.; Abdullin, T.I.; Grigor’eva, L.R.; Kuznetsova, E.V.; Akhmadishina, R.A.; Ziganshina, L.E.; Cong, H.H.; Mironov, V.F. Design, Synthesis, and Cancer Cell Growth Inhibitory Activity of Triphenylphosphonium Derivatives of the Triterpenoid Betulin. J Nat Prod 2017, 80, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsepaeva, O.V.; Nemtarev, A.V.; Grigor’eva, L.R.; Voloshina, A.D.; Mironov, V.F. Esterification of Betulin with ω-Bromoalkanoic Acids. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2015, 51, 1318–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommera, H.; Kaluđerović, G.N.; Kalbitz, J.; Paschke, R. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of Novel Betulinic Acid and Betulin Derivatives. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2010, 343, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migglautsch, A.K.; Willim, M.; Schweda, B.; Glieder, A.; Breinbauer, R.; Winkler, M. Aliphatic Hydroxylation and Epoxidation of Capsaicin by Cytochrome P450 CYP505X. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 6199–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, J.; Namito, Y.; Matsubara, R.; Hayashi, M. Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure (8 S,9 S,10 R,6 Z )-Trihydroxyoctadec-6-Enoic Acid. J Org Chem 2017, 82, 5146–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, R.; Fei, H.; Zhou, M. Mitochondria-Targeting Phosphorescent Iridium( <scp>iii</Scp> ) Complexes for Living Cell Imaging. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 16872–16879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.K.; Marrache, S.; Harn, D.A.; Dhar, S. Mito-DCA: A Mitochondria Targeted Molecular Scaffold for Efficacious Delivery of Metabolic Modulator Dichloroacetate. ACS Chem Biol 2014, 9, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang Thi, T.A.; Kim Tuyet, N.T.; Pham The, C.; Thanh Nguyen, H.; Ba Thi, C.; Thi Phuong, H.; Van Boi, L.; Van Nguyen, T.; D’hooghe, M. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Evaluation of Novel Amide–Triazole-Linked Triterpenoid–AZT Conjugates. Tetrahedron Lett 2015, 56, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjala, L.; Alakurtti, S.; Ahola, T.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Tammela, P. Betulin-Derived Compounds as Inhibitors of Alphavirus Replication. J Nat Prod 2009, 72, 1917–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang Thi, T.A.; Kim Tuyet, N.T.; Pham The, C.; Thanh Nguyen, H.; Ba Thi, C.; Thi Phuong, H.; Van Boi, L.; Van Nguyen, T.; D’hooghe, M. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Evaluation of Novel Amide–Triazole-Linked Triterpenoid–AZT Conjugates. Tetrahedron Lett 2015, 56, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, Q.; Si, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Pentacyclic Triterpene α -Cyclodextrin Conjugates as HCV Entry Inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 2016, 124, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, Q.; Si, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Synthesis and Anti-HCV Entry Activity Studies of Β-Cyclodextrin–Pentacyclic Triterpene Conjugates. ChemMedChem 2014, 9, 1060–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludeña Huaman, M.A.; Tupa Quispe, A.L.; Huamán Quispe, R.I.; Serrano Flores, C.A.; Robles Caycho, J. A Simple Method to Obtain Ursolic Acid. Results Chem 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daasch, L.; Smith, D. Infrared Spectra of Phosphorus Compounds. Anal Chem 1951, 23, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonia, R.; Insuasty, D.; Laali, K.K. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Propargyl Derivatives, and Their Application as Synthetic Intermediates and Building Blocks †. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Brullo, C.; Caviglia, D.; Zuccari, G. Preparation and Physicochemical Characterization of Water-Soluble Pyrazole-Based Nanoparticles by Dendrimer Encapsulation of an Insoluble Bioactive Pyrazole Derivative. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. Considerable Improvement of Ursolic Acid Water Solubility by Its Encapsulation in Dendrimer Nanoparticles: Design, Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Oliveri, P.; Malegori, C. Assessment of the Efficiency of a Nanospherical Gallic Acid Dendrimer for Long-Term Preservation of Essential Oils: An Integrated Chemometric-Assisted FTIR Study. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 8891–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccacci, F.; Sennato, S.; Rossi, E.; Proroga, R.; Sarti, S.; Diociaiuti, M.; Casciardi, S.; Mussi, V.; Ciogli, A.; Bordi, F.; et al. Aggregation Behaviour of Triphenylphosphonium Bolaamphiphiles. J Colloid Interface Sci 2018, 531, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Valenti, G.; Domenicotti, C. Synthesis of Polystyrene-Based Cationic Nanomaterials with Pro-Oxidant Cytotoxic Activity on Etoposide-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Zuccari, G.; Caviglia, D.; Brullo, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Pyrazole-Enriched Cationic Nanoparticles as New Promising Antibacterial Agent by Mutual Cooperation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E. The Role of Surface Charge in Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Medical Nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine 2012, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Spallarossa, A.; Lusardi, M.; Zuccari, G. Successful Dendrimer and Liposome-Based Strategies to Solubilize an Antiproliferative Pyrazole Otherwise Not Clinically Applicable. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri-Fink, A.; Chastellain, M.; Juillerat-Jeanneret, L.; Ferrari, A.; Hofmann, H. Development of Functionalized Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Interaction with Human Cancer Cells. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2685–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambhrunkar, S.; Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Shrotri, A.; Endo-Munoz, L.; Moreau, J.; Lu, G.; Yu, C. Stepwise Pore Size Reduction of Ordered Nanoporous Silica Materials at Angstrom Precision. J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135, 8444–8447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mccrate, J.M.; Lee, J.C.-M.; Li, H. The Role of Surface Charge on the Uptake and Biocompatibility of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles with Osteoblast Cells. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinc, A.; Battaglia, G. Exploiting Endocytosis for Nanomedicines. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5, a016980–a016980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvil, Byron. Titrations in Nonaqueous Solvents. Anal Chem 1982, 54, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seher, A. Dr. I. Gyenes, C. Sc. (Chim.), Titrationen in Nichtwäßrigen Medien, 3. Neubearb. u. Erg. Aufl., 701 S., 206 Abb., 108 Tab., Gln., Ferdinand Enke Verlag, Stuttgart 1970, Preis: 84.—DM. Fette, Seifen, Anstrichmittel 1973, 75, 232–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šafařík, L.; Stránský, Z.; Svehla, G.; Burns, D.T. Titrimetric Analysis in Organic Solvents (Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, Vol. XXII). Anal Chim Acta 1987, 201, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascellani, Giuseppe. ; Casalini, Claudio. Use of Mercuric Acetate in Potentiometric Titrations in a Nonaqueous Medium. Anal Chem 1975, 47, 2468–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulani, M.S.; Kamble, E.E.; Kumkar, S.N.; Tawre, M.S.; Pardesi, K.R. Emerging Strategies to Combat ESKAPE Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.B. Federal Funding for the Study of Antimicrobial Resistance in Nosocomial Pathogens: No ESKAPE. J Infect Dis 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, B.; Cagide, F.; Borges, F.; Simões, M. Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity of Novel Quaternary Ammonium and Phosphonium Salts. J Mol Liq 2024, 401, 124616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Zuegg, J.; Elliott, A.G.; Baker, M.; Braese, S.; Brown, C.; Chen, F.; G. Dowson, C.; Dujardin, G.; Jung, N.; et al. Metal Complexes as a Promising Source for New Antibiotics. Chem Sci 2020, 11, 2627–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, A.; Ramu, S.; Lowe, G.J.; Dinh, H.; Semenec, L.; Elliott, A.G.; Zuegg, J.; Deckers, A.; Jung, N.; Bräse, S.; et al. Platinum Cyclooctadiene Complexes with Activity against Gram-positive Bacteria. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 3165–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M. From Nanobiotechnology, Positively Charged Biomimetic Dendrimers as Novel Antibacterial Agents: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, A.M. Positively Charged Polymers as Promising Devices against Multidrug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, A.M.; Alfei, S. Antibacterial Activity of Non-Cytotoxic, Amino Acid-Modified Polycationic Dendrimers against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Other Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacteria. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, A.M.; Piatti, G.; Caviglia, D.; Zuccari, G.; Alfei, S. Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal Activity of a Synthetic Random Copolymer Based on 2-Methoxy-6-(4-Vinylbenzyloxy)-Benzylammonium Hydrochloride. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Piatti, G.; Caviglia, D.; Schito, A. Synthesis, Characterization, and Bactericidal Activity of a 4-Ammoniumbuthylstyrene-Based Random Copolymer. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurjar, M. Colistin for Lung Infection: An Update. J Intensive Care 2015, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, Z.; Zuo, W.; Zhu, M. S-Alkylated Sulfonium Betulin Derivatives: Synthesis, Antibacterial Activities, and Wound Healing Applications. Bioorg Chem 2025, 154, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, G.C.S.; dos Santos Maia, M.; de Souza, T.A.; de Oliveira Lima, E.; dos Santos, L.E.C.G.; Silva, S.L.; da Silva, M.S.; Filho, J.M.B.; da Silva Rodrigues Junior, V.; Scotti, L.; et al. Antimicrobial Potential of Betulinic Acid and Investigation of the Mechanism of Action against Nuclear and Metabolic Enzymes with Molecular Modeling. Pathogens 2023, 12, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schito, A.M.; Caviglia, D.; Piatti, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Zuccari, G.; Schito, G.C.; Alfei, S. Efficacy of Ursolic Acid-Enriched Water-Soluble and Not Cytotoxic Nanoparticles against Enterococci. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seferyan, M.A.; Saverina, E.A.; Frolov, N.A.; Detusheva, E.V.; Kamanina, O.A.; Arlyapov, V.A.; Ostashevskaya, I.I.; Ananikov, V.P.; Vereshchagin, Anatoly.N. Multicationic Quaternary Ammonium Compounds: A Framework for Combating Bacterial Resistance. ACS Infect Dis 2023, 9, 1206–1220. [CrossRef]

- Haykir, N.I.; Nizan Shikh Zahari, S.M.S.; Harirchi, S.; Sar, T.; Awasthi, M.K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Applications of Ionic Liquids for the Biochemical Transformation of Lignocellulosic Biomass into Biofuels and Biochemicals: A Critical Review. Biochem Eng J 2023, 193, 108850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S. Shifting from Ammonium to Phosphonium Salts: A Promising Strategy to Develop Next-Generation Weapons against Biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, F.O.; Duru, K.C.; Li, E.; Kovaleva, E.G.; Tsurkan, M.V. Pharmacological Potential of Betulin as a Multitarget Compound. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakurtti, S.; Mäkelä, T.; Koskimies, S.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J. Pharmacological Properties of the Ubiquitous Natural Product Betulin. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2006, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, J.B.; Vianna, M.H.; Ferreira, T.G.; de, O. Lemos, A.S.; Souza, T. de F.; Campos, L.M.; Paula, P. de L.; Andrade, N.B.; Gamarano, L.R.; Queiroz, L.S.; et al. Enhanced Antitumor and Antibacterial Activities of Ursolic Acid through β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexation. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 12906–12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Shang, X.; Huang, W.; Ang, S.; Li, D.; Wong, W.-L.; Hong, W.D.; Zhang, K.; et al. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Novel Ursolic Acid Derivatives as Potential Antibacterial Agents against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). Bioorg Chem 2025, 154, 107986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do Nascimento, P.G.G.; Lemos, T.L.G.; Bizerra, A.M.C.; Arriaga, A.M.C.; Ferreira, D.A.; Santiago, G.M.P.; Braz-Filho, R.; Costa, J.G.M. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Ursolic Acid and Derivatives. Molecules 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolska, K.; Grudniak, A.; Fiecek, B.; Kraczkiewicz-Dowjat, A.; Kurek, A. Antibacterial Activity of Oleanolic and Ursolic Acids and Their Derivatives. Open Life Sci 2010, 5, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrafi, A.; Wasilewski, A. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of New Betulin Derivatives. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 17719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Nawrot, D.A.; Alakurtti, S.; Ghemtio, L.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Tammela, P. Screening and Characterisation of Antimicrobial Properties of Semisynthetic Betulin Derivatives. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugiņina, J.; Kroškins, V.; Lācis, R.; Fedorovska, E.; Demir, Ö.; Dubnika, A.; Loca, D.; Turks, M. Synthesis and Preliminary Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Water Soluble Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Phosphonates. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 28031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu (Similie), D.; Bora, L.; Avram, Ștefana; Turks, M.; Muntean, D.; Danciu, C. Assessment of the Antiproliferative, Cytotoxic, Antimigratory, Antimicrobial, and Irritative Potential of Novel Phosphonate Derivatives of Betulinic Acid. In Proceedings of the INT-DOC-RES.; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, September 16 2025; p. 1.

- Alfei, S.; Torazza, C.; Bacchetti, F.; Milanese, M.; Passalaqua, M.; Khaledizadeh, E.; Vernazza, S.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. TPP-Based Nanovesicles Kill MDR Neuroblastoma Cells and Induce Moderate ROS Increase, While Exert Low Toxicity To-Wards Primary Cell Cultures: An in Vitro Study. IJMS 2025, 26, 4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvana Alfei; Marco Milanese; Carola Torazza; Maria Grazia Signorello; Mario Passalacqua; Cinzia Domenicotti; Barbara Marengo Tri-Phenyl-Phosphonium-Based Nano Vesicles: A New In Vitro Nanomolar-Active Weapon to Eradicate PLX-Resistant Mela-Noma Cells by a Time-Dependent Mechanism. International Journal of Molecular Science 2025.

- Alfei, S.; Giannoni, P.; Signorello, M.G.; Torazza, C.; Zuccari, G.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. The Remarkable and Selective In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Synthesized Bola-Amphiphilic Nanovesicles on Etoposide-Sensitive and -Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Zuccari, G.; Athanassopoulos, C.M.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. Strongly ROS-Correlated, Time-Dependent, and Selective Antiproliferative Effects of Synthesized Nano Vesicles on BRAF Mutant Melanoma Cells and Their Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogel Formulation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 10071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Weight (mg) | * MW | * P+ (µmol) | 0.1 N HClO4 § | ** P+ (µmol) | ** MW | *** Residuals | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 | 963.1 | 1.0383 | 10.40 | 1.0400 | 961.5 | 1.6 | 0.16 |

| 4 | 0.6 | 933.1 | 0.6430 | 6.44 | 0.6440 | 931.7 | 0.8 | 0.14 |

| 5 | 0.7 | 882.0 | 0.7936 | 7.96 | 0.7960 | 879.4 | 2.6 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 1.1 | 1321.4 | 1.6648 | 16.60 | 1.6600 | 1325.3 | 3.9 | 0.30 |

| 7 | 1.5 | 933.1 | 1.6075 | 16.20 | 1.6202 | 925.8 | 7.3 | 0.78 |

| Gram positive isolates | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | BET | BA | UA | R.A. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICs (µg/mL) | ||||||||

| S. aureus MRSA 18 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 2 | >64 | >64 | 64 | 256 (O) |

| S. epidermidis MRSE 22 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 | >64 | >64 | 32 | 128 (O) |

| E. faecalis VRE 1 * | 16 | 8 | 16 | 4 | >64 | >64 | 4 | 256 (V); 64 (T) |

| E. faecium VRE 152 * | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | >64 | >64 | 2 | 128 (V); 64 (T) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).