Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

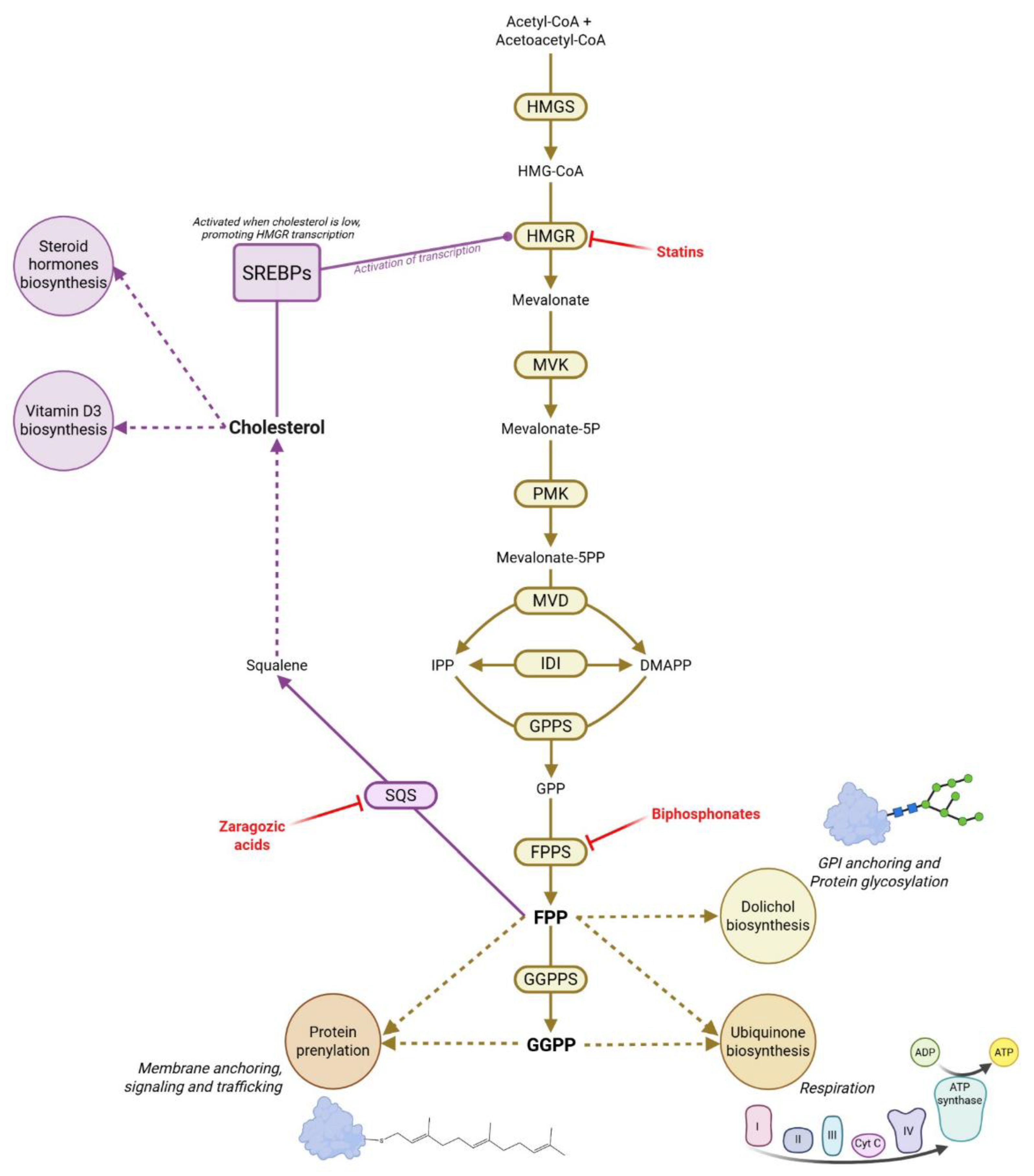

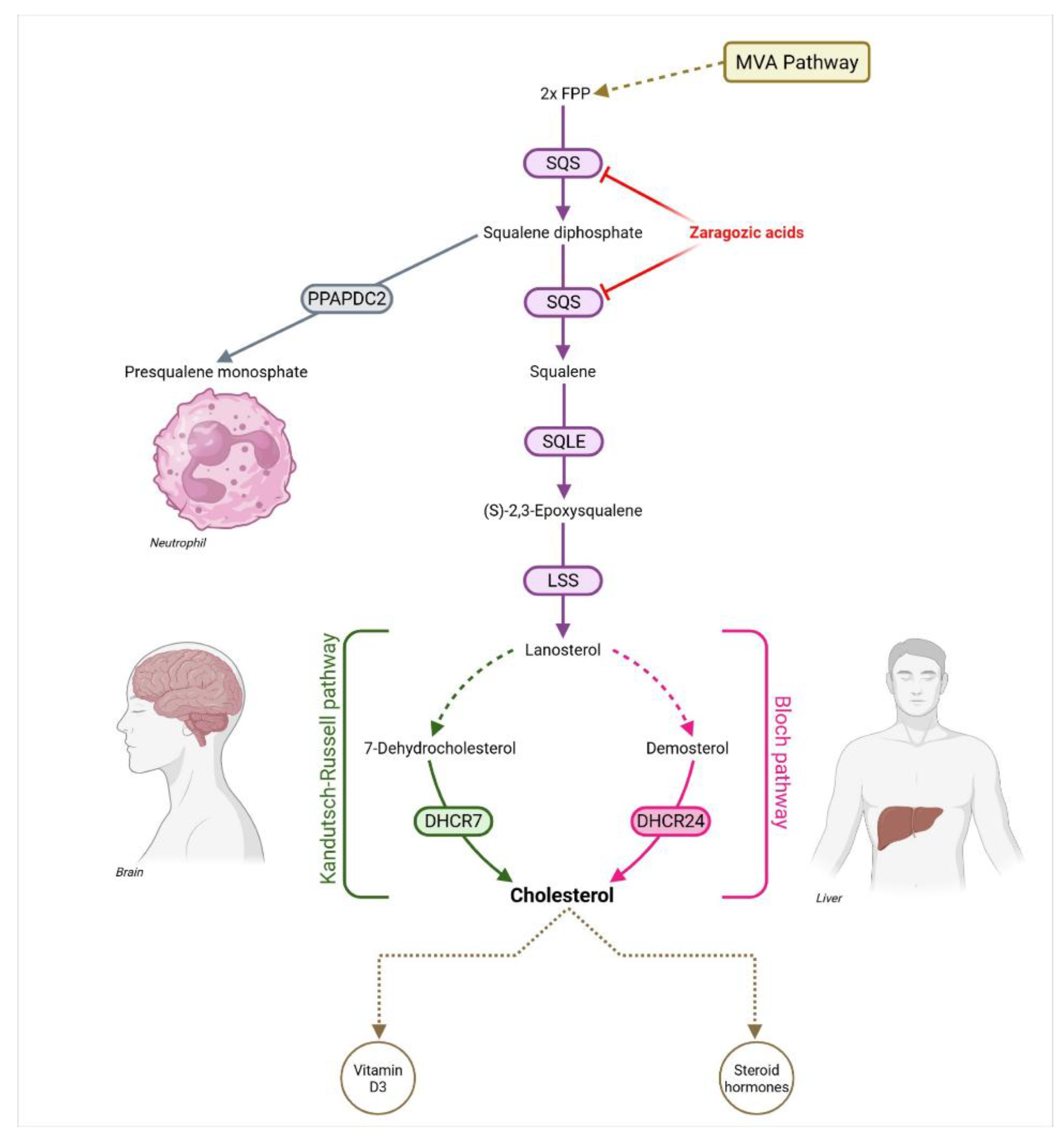

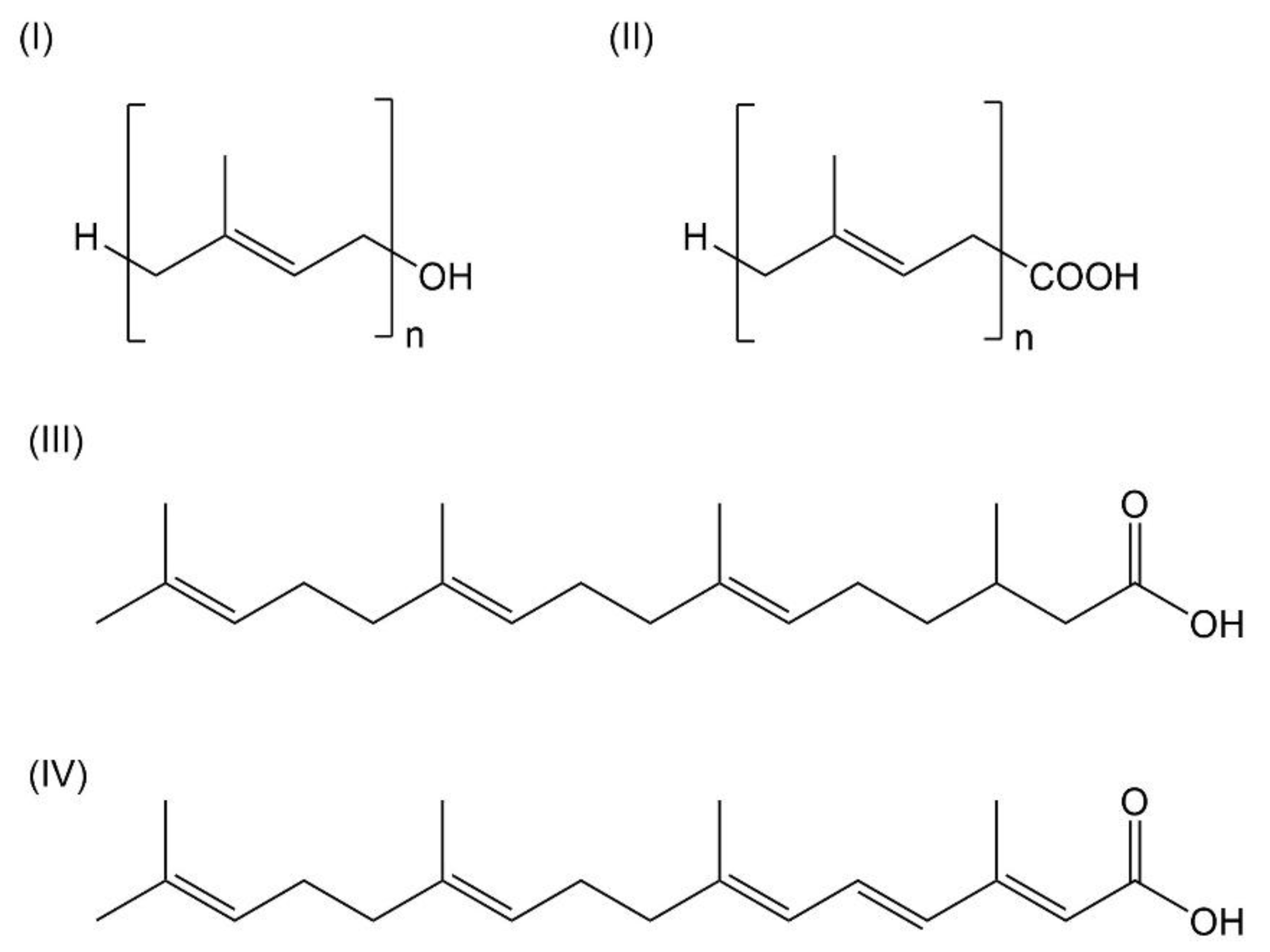

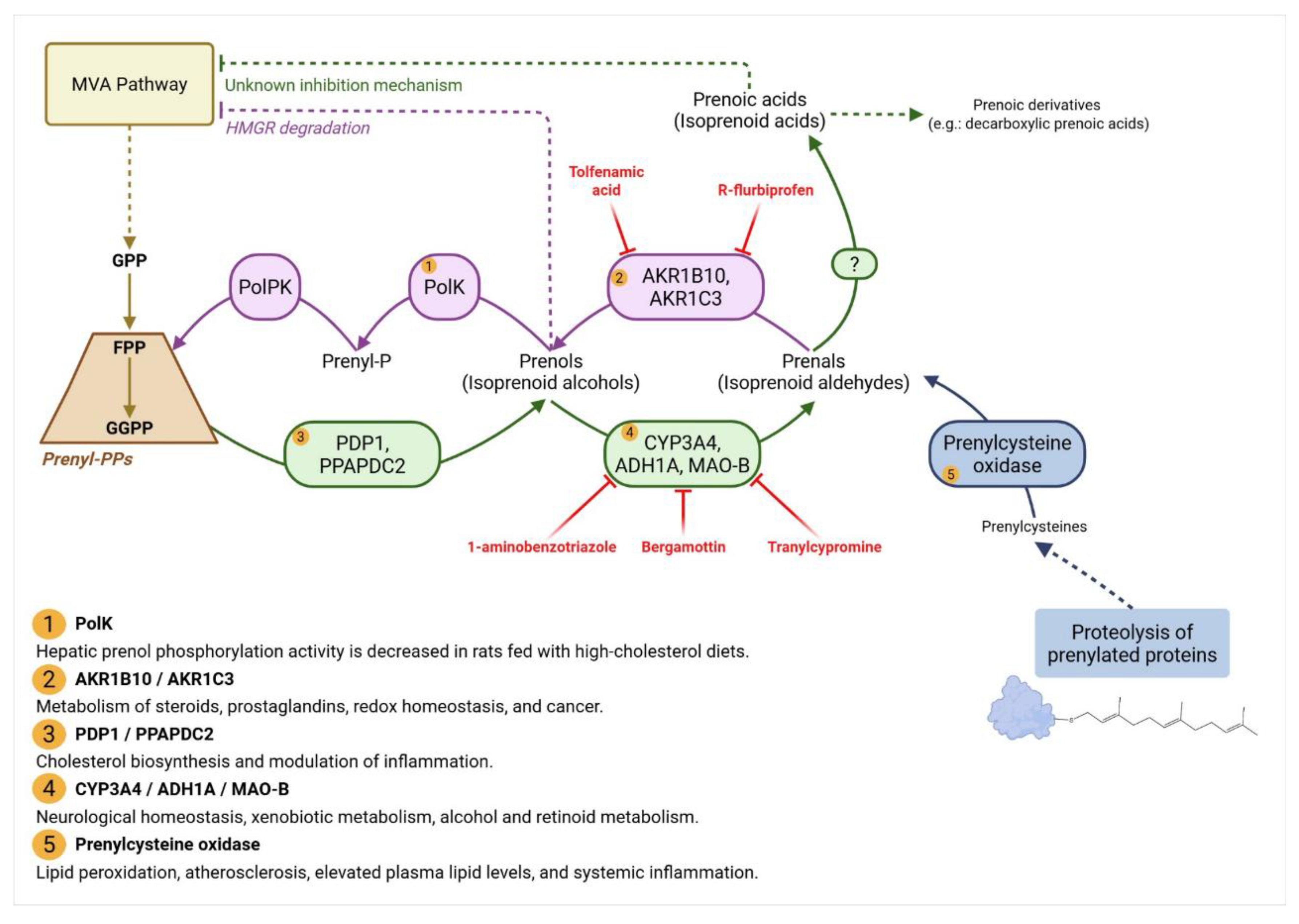

Acyclic terpene derivatives are well known as components of plant essential oils and insect hormones, yet their active biosynthesis also occurs in mammals. The terpenic alcohols—or prenols—geranylgeraniol (GGOH) and farnesol (FOH), together with their prenoic acids and derivatives, were identified in mammalian cells over sixty years ago but remain largely overlooked. These metabolites display diverse biological functions: they induce autophagy, inhibit tumor growth and inflammation, suppress cholesterol synthesis, enhance insulin sensitivity and cognition, regulate sexual characteristics, and promote healthy aging. In mammals, prenols arise from an age-dependent, bidirectional pathway that interconverts polyprenyl diphosphates, prenols, and prenoic acids. They can be oxidized into aldehydes and carboxylic acids or reconverted into diphosphate forms for use in protein prenylation and in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone, cholesterol, and dolichol. While enzymes catalyzing polyprenyl diphosphate dephosphorylation and oxidation steps have been partly characterized, the kinases mediating their reverse phosphorylation remain unidentified. This review summarizes current advances in the understanding of prenol metabolism in mammals, emphasizing its role in metabolic regulation, disease prevention, and longevity. By integrating biochemical and physiological evidence, we highlight the emerging view that these small terpenes constitute a fundamental yet underexplored layer of metabolic control. Greater attention to this pathway may reveal novel strategies for maintaining metabolic health and mitigating age-related disorders.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cellular Mechanisms of Aging

1.2. The Mevalonate Pathway at the Heart of Metabolic Control

2. Discovery and Characterization of Prenols and Prenoic Acids Biosynthesis

2.1. Occurrence of Prenols and Prenoic Acids Biosynthesis Across Animal and Microbial Life

2.2. Prenoic Acid Biosynthesis from Prenols: A Converging Pathway Linking Inflammation, Cancer, Hormonal Control, Lipid Homeostasis, and Cell Signaling

2.3. The Missing kinases of Prenols: A Key Regulator of Isoprenoid Homeostasis?

3. Metabolic Effects of Prenols and Prenoic Acids

3.1. Prenols

3.1.1. Geraniol

3.1.2. Farnesol

3.1.3. Geranylgeraniol

3.2. Prenoic Acids

3.2.1. Geranoic Acid

3.2.2. Farnesoic Acid

3.2.3. Geranylgeranoic Acid and Related Compounds

4. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

- Acetyl-CoA – Acetyl-coenzyme A

- ADH1A – Alcohol dehydrogenase 1A

- AGEs – Advanced glycation end-products

- AKR1B10 – Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10

- AKR1C3 – Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3

- Akt – Protein kinase B

- AMPK – AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATF4 – Activating transcription factor 4

- Bax – Bcl-2-associated X protein

- Bcl-2 – B-cell lymphoma 2 (anti-apoptotic protein)

- cAMP/PKA – Cyclic adenosine monophosphate / protein kinase A

- CHOP – C/EBP homologous protein

- c-MYC – Cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene

- COX-2 – Cyclooxygenase-2

- CYP3A4 – Cytochrome P450 3A4

- DHCR24 – 24-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- DHCR7 – 7-Dehydrocholesterol reductase

- DMAPP – Dimethylallyl diphosphate

- ERK – Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FP – Farnesyl monophosphate

- FPP – Farnesyl diphosphate

- FPPS – Farnesyl diphosphate synthase

- FXR – Farnesoid X receptor

- GGP – Geranylgeranyl monophosphate

- GGPP – Geranylgeranyl diphosphate

- GGPPS – Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase

- GOH - Geraniol

- GPP – Geranyl diphosphate

- GPPS – Geranyl diphosphate synthase

- HMG-CoA – 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- HMGR – 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase

- HMGS – 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase

- HO-1 – Heme oxygenase-1

- IDI – Isopentenyl-diphosphate isomerase

- IL-1β – Interleukin-1 beta

- IL-6 – Interleukin-6

- iNOS – Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IPP – Isopentenyl diphosphate

- JNK – c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- K⁺ – Potassium ion

- KLF4 – Krüppel-like factor 4

- MAO-B – Monoamine oxidase B

- MAPK – Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR – Mechanistic target of rapamycin

- MVA – Mevalonate

- MVK – Mevalonate kinase

- NAD⁺ – Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form)

- NF-κB – Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NLRP3 – NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3

- Nrf2 – Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- OCT4 – Octamer-binding transcription factor 4

- PARP – Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PDP1 / PPAPDC2 – Pyrophosphatase/phosphatase domain-containing protein 2

- PDZ – PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 (protein–protein interaction domain)

- PERK – Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- PI3K – Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PMK – Phosphomevalonate kinase

- PolK – Polyprenol kinase

- PolPK – Polyprenyl phosphate kinase

- PPAR – Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PPARγ - Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RAR – Retinoic acid receptor

- RXR – Retinoid X receptor

- SAM – S-Adenosylmethionine

- SERCA – Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase

- SOX2 – SRY-box transcription factor 2

- SQLE – Squalene epoxidase

- SQS – Squalene synthase

- SREBPs – Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins

- SQS – Squalene synthase

- TNF-α – Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- UBIAD1 – UbiA prenyltransferase domain-containing protein 1

- YAP – Yes-associated protein

- α-Ketoglutarate – Alpha-ketoglutarate (a Krebs cycle intermediate)

References

- Ahmed, S. R.; Uttra, A. M.; Usman, M.; Qasim, S.; Jahan, S.; Roman, M.; Rashwan, E. K. Deciphering farnesol’s anti-arthritic and immunomodulatory potential by targeting multiple pathways: A combination of network pharmacology guided exploration and experimental verification. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2025, 77(1), 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, J. K.; Lundquist, E. A. Mutationally activated Rho GTPases in cancer. Small GTPases 2013, 4(3), 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Åberg, F.; Teclebrhan, H.; Edlund, C.; Appelkvist, E. L. Age-dependent modifications in the metabolism of mevalonate pathway lipids in rat brain. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 1995, 85(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, H.; Shidoji, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Muto, Y. Retinoid agonist activities of synthetic geranylgeranoic acid derivatives. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 1995, 209(1), 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arenas, F.; Garcia-Ruiz, C.; Fernandez-Checa, J. C. Intracellular cholesterol trafficking and impact in neurodegeneration. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2017, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschner, M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Sinitskii, A.I.; Santamaría, A.; Bornhorst, J.; Ajsuvakova, O.P.; da Rocha, J.B.T.; Skalny, A.V.; Tinkov, A.A. Isolevuglandins (isoLGs) as toxic lipid peroxidation byproducts and their pathogenetic role in human diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2021, 162, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, C.; Baetta, R.; Barbieri, S. S.; Brioschi, M.; Guarino, A.; Ghilardi, S.; Sandrini, L.; Eligini, S.; Polvani, G.; Bergman, O.; Eriksson, P.; Tremoli, E. Prenylcysteine oxidase 1, an emerging player in atherosclerosis. Communications biology 2021, 4(1), 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, N.; Huffman, D. M.; Muzumdar, R. H.; Bartke, A. The critical role of metabolic pathways in aging. Diabetes 2012, 61(6), 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M. A.; de Lima Teixeira dos Santos, A. V. T.; do Nascimento, A. L.; Moreira, L. F.; Souza, I. R. S.; da Silva, H. R.; Carvalho, J. C. T. Potential of the compounds from Bixa orellana purified annatto oil and its granules (Chronic®) against dyslipidemia and inflammatory diseases: in silico studies with geranylgeraniol and tocotrienols. Molecules 2022, 27(5), 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belakova, B.; Wedige, N. K.; Awad, E. M.; et al. Lipophilic statins eliminate senescent endothelial cells by inducing anoikis-related cell death. Cells 2023, 12(24), 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentinger, M.; Grünler, J.; Peterson, E.; Swiezewska, E.; Dallner, G. Phosphorylation of farnesol in rat liver microsomes: Properties of farnesol kinase and farnesyl phosphate kinase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 353, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratic, A.; Larsson, N. G. The role of mitochondria in aging. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013, 123(3), 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhaescu, I.; Izzedine, H. Mevalonate pathway: A review of clinical and therapeutical implications. Clinical Biochemistry 2007, 40(9-10), 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrns, M. C.; Mindnich, R.; Duan, L.; Penning, T. M. Overexpression of aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) in prostate cancer: Implications for resistance to hormone therapy and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2008, 178(1-3), 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, A.; Madyastha, K. M. Metabolism of geraniol and linalool in the rat and effects on liver and lung microsomal enzymes. Xenobiotica 1984, 14(5), 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Tripathi, A.S.; Hasan, T.; Ganesh, K.; Cordero, M.A.W.; Yasir, M.; Zaki, M.E.A.; Tripathi, P.; Mohapatra, L.; Maurya, R.K. Geraniol reverses obesity by improving conversion of WAT to BAT in high fat diet induced obese rats by inhibiting HMGCoA reductase. Nutr Diabetes 2023, 13(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; So, I.; Chun, J.N.; Jeon, J.H. The antitumor effects of geraniol: Modulation of cancer hallmark pathways (Review). Int J Oncol. 2016, 48(5), 1772–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S. Y. Inhibitory effects of geranic acid derivatives on melanin biosynthesis. Journal of Cosmetic Science 2012, 63(5), 351–358, microbialcellfactories.biomedcentral.com. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christophe, J.; Popják, G. Studies on the biosynthesis of cholesterol: XIV. The origin of prenoic acids from allyl diphosphates in liver enzyme systems. Journal of Lipid Research 1961, 2(3), 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Kim, H. J.; Kwon, J. Y.; Cho, S. Y. Beneficial effect of dietary geranylgeraniol on glucose homeostasis and bone microstructure in obese mice. Nutrition Research 2021, 93, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, D.C.; Andres, D.A.; Waechter, C.J. Farnesol is utilized for protein isoprenylation and the biosynthesis of cholesterol in mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 211, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, D.C.; Andres, D.A.; Waechter, C.J. Novel salvage pathway utilizing farnesol and geranylgeraniol for protein isoprenylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 237, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, M.; Bofill Verdaguer, I.; Mazzine Filho, M.; Santos, M. F.; Hernández, A. Isoprenoids, the versatile lipids: Their functions in intracellular membranes. In Advances in Biology; Nova Science Publishers, September 2024; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Crispim, M.; Verdaguer, I. B.; Hernández, A.; Kronenberger, T.; Fenollar, À.; Yamaguchi, L. F.; Izquierdo, L. Beyond the MEP Pathway: A novel kinase required for prenol utilization by malaria parasites. PLoS Pathogens 2024, 20(1), e1011557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Loof, A.; Marchal, E.; Rivera-Perez, C.; Noriega, F. G.; Schoofs, L. Farnesol-like endogenous sesquiterpenoids in vertebrates: the probable but overlooked functional “inbrome” anti-aging counterpart of juvenile hormone of insects? Frontiers in endocrinology 2015, 5, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Loof, A.; Schoofs, L. Mode of Action of Farnesol, the “Noble Unknown” in Particular in Ca2+ Homeostasis, and Its Juvenile Hormone-Esters in Evolutionary Retrospect. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Casado, M. E.; Quiles, J. L.; Barriocanal-Casado, E.; González-García, P.; Battino, M.; López, L. C.; Varela-López, A. The Paradox of Coenzyme Q10 in Aging. Nutrients 2019, 11(9), 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dituri, F.; Rabinowitz, J. L.; Hullin, R. P.; Gurin, S. G. Precursors of squalene and cholesterol. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1957, 229(2), 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duester, G. Families of retinoid dehydrogenases regulating vitamin A function: Production of visual pigment and retinoic acid. European Journal of Biochemistry 2000, 267(14), 4315–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Azab, E.F.; Elguindy, N.M.; Yacout, G.A.; Elgamal, D.A. Hepatoprotective Impact of Geraniol Against CCl4-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences 2020, 23(12), 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabrouty, R.; Jo, Y.; Hwang, S.; Jun, D.-J.; DeBose-Boyd, R. A. Type 1 polyisoprenoid diphosphate phosphatase modulates geranylgeranyl-mediated control of HMG CoA reductase and UBIAD1. eLife 2021, 10, e64688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Kitade, Y.; Soda, M.; Zhao, Y.; Murata, K.; El-Kabbani, O. Roles of aldo-keto reductases in the reduction of farnesal and geranylgeranial in human and murine cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2009, 178(1-3), 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, S.; Matsunaga, T.; Ohta, C.; Soda, M.; Kanamori, A.; Kitade, Y.; et al. Roles of rat and human aldo-keto reductases in metabolism of farnesol and geranylgeraniol. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2011, 191(1-3), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N. V.; Yeganehjoo, H.; Katuru, R.; DeBose-Boyd, R. A.; Morris, L. L.; Michon, R.; Yu, Z. L.; Mo, H. Geranylgeraniol suppresses the viability of human DU145 prostate carcinoma cells and the level of HMG CoA reductase; Experimental biology and medicine: Maywood, N.J., 2013; Volume 238, 11, pp. 1265–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, A.H.; Bhandari, J.; Crowell, D.N. Farnesol kinase is involved in farnesol metabolism, ABA signaling and flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 66, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliesler, S. J.; Schroepfer, G. J., Jr. Metabolism of mevalonic acid in cell-free homogenates of bovine retinas: Formation of novel isoprenoid acids. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1983, 258(24), 15062–15070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. M.; Pennock, J. F.; Marshall, I.; Rees, H. H. Biosynthesis of isoprenoid compounds in Schistosoma mansoni. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology 1993, 61(2), 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2018, 14(10), 576–590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, S.; Yamauchi, N.; Moriguchi, H.; Hippo, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Shibahara, J.; Aburatani, H. Overexpression of the aldo-keto reductase family member AKR1B10 is highly correlated with smokers’ non-small cell lung carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11(5), 1776–1785. 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukunaga, K.; Arita, M.; Takahashi, M.; Morris, A. J.; Pfeffer, M.; Levy, B. D. Identification and functional characterization of a presqualene diphosphate phosphatase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281(14), 9490–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, Z. E.; Pickering, J.; Eskiw, C. H. Better living through chemistry: Caloric restriction (CR) and CR mimetics alter genome function to promote increased health and lifespan. Frontiers in Genetics 2016, 12, 662320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J. L.; Brown, M. S. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature 1990, 343(6257), 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, S.; Preta, G.; Sheldon, I. M. Inhibiting mevalonate pathway enzymes increases stromal cell resilience to a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N. T.; Lee, C. H. Roles of Farnesyl-Diphosphate Farnesyltransferase 1 in Tumour and Tumour Microenvironments. Cells 2020, 9(11), 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagvall, L.; Baron, J. M.; Börje, A.; Weidolf, L.; Merk, H.; Karlberg, A. T. Cytochrome P450-mediated activation of the fragrance compound geraniol forms potent contact allergens. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2008, 233(2), 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, D. Aging: Overview. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2001, 928(1), 1–21. 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Kashio, S.; Murotomi, K.; Hino, S.; Kang, W.; Miyado, K.; Nakao, M.; Miura, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Namihira, M. Biosynthesis of S-adenosyl-methionine enhances aging-related defects in Drosophila oogenesis. Science Reports 2022, 12(1), 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, H. Ueber Synthesen im Thierkörper (2. mittheilung). Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 1900, 45, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooff, G. P.; Wood, W. G.; Kim, J. H.; Igbavboa, U.; Ong, W. Y.; Muller, W. E.; Eckert, G. P. Brain isoprenoids farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate are increased in aged mice. Molecular neurobiology 2012, 46(1), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S. I.; Guarente, L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends in Cell Biology 2014, 24(8), 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwao, C.; Shidoji, Y. Upregulation of energy metabolism-related, p53-target TIGAR and SCO2 in HuH-7 cells with p53 mutation by geranylgeranoic acid treatment. Biomedical Research 2015, 36(6), 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, A.; Scherer, B.; Fritz, G.; Honnen, S. Statins Induce a DAF-16/Foxo-dependent Longevity Phenotype via JNK-1 through Mevalonate Depletion in C. elegans. Aging Disease 2020, 11(1), 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jawad, M. J.; Ibrahim, S.; Kumar, M.; Burgert, C.; Li, W. W.; Richardson, A. Identification of foods that affect the anti-cancer activity of pitavastatin in cells. Oncology Letters 2022, 23(3), 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Penning, T. M. Aldo-keto reductases and bioactivation/detoxication. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2006, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiwan, N. C.; Appell, C. R.; Sterling, R.; Shen, C. L.; Luk, H. Y. The Effect of Geranylgeraniol and Ginger on Satellite Cells Myogenic State in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Current issues in molecular biology 2024, 46(11), 12299–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J. H.; Jetten, A. M. Molecular mechanisms involved in farnesol-induced apoptosis. Cancer Letters 2010, 287(2), 123–135, (Discusses farnesol and farnesoic acid in apoptosis signaling)pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B. K.; Berger, S. L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A. M.; Epel, E. S.; Sierra, F. Geroscience: Linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 2014, 159(4), 709–713. 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T. B. L. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell 2005, 120, 437–447. 50, Kuhn R., Kohler F., Kohler L. Uber methyl-oxidationen im tierkorper. Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 1936;242:171–197. 51.. [Google Scholar]

- Kodaira, Y.; Kusumoto, T.; Takahashi, T.; Matsumura, Y.; Miyagi, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Sagami, H. Formation of lipid droplets induced by 2, 3-dihydrogeranylgeranoic acid distinct from geranylgeranoic acid. Acta Biochimica Polonica 2007, 54(4), 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaira, Yuichi; et al. Formation of (R)-2, 3-dihydrogeranylgeranoic acid from geranylgeraniol in rat thymocytes. The journal of biochemistry 2002, 132.2, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, R.; Köhler, F.; Köhler, L. Über Methyl-Oxidationen im Tierkörper. Hoppe-Seyler’s Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie 1936, 242, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzu, B.; Cüce, G.; Ayan, I.Ç.; Gültekin, B.; Canbaz, H.T.; Dursun, H.G.; Şahin, Z.; Keskin, I.; Kalkan, S.S. Evaluation of Apoptosis Pathway of Geraniol on Ishikawa Cells. Nutrition and Cancer 2021, 73(11-12), 2532–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D. M. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 2012, 149(2), 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, H. R.; Popjak, G. Studies on the biosynthesis of cholesterol. 10. Mevalonic kinase and phosphomevalonic kinase from liver. Biochemical Journal 1960, 75.3, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wong, C. C.; Fu, L.; Chen, H.; Zhao, L.; Li, C.; Yu, J. Squalene epoxidase drives NAFLD-induced hepatocellular carcinoma and is a pharmaceutical target. Science translational medicine 2018, 10(437), eaap9840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153(6), 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Guenthner, T.; Gan, L. S.; Humphreys, W. G. CYP3A4 induction by xenobiotics: biochemistry, experimental methods and impact on drug discovery and development. Current drug metabolism 2004, 5(6), 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Wińska, K.; Grabarczyk, M. One Hundred Faces of Geraniol. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 25(14), 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannick, J. B.; Del Giudice, G.; Lattanzi, M.; Valiante, N. M.; Praestgaard, J.; Huang, B.; Klickstein, L. B. mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6(268), 268ra179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuzzi, A.; Piscianz, E.; Valencic, E.; Kleiner, G.; Vecchi Brumatti, L.; Monasta, L.; Crovella, S. Geranylgeraniol rescues neuron-like cells from mevalonate pathway blockade: link to inflammasome inhibition. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17(3), 365. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuzzi, A.; Pontillo, A.; Leo, L. D.; Tommasini, A.; Decorti, G.; Not, T.; Ventura, A. Natural isoprenoids are able to reduce inflammation in a mouse model of mevalonate kinase deficiency. Pediatric Research 2008, 64(2), 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Odaka, Y.; Ogawa, N.; Nakamoto, K.; Kuninaga, H. Identification of geranic acid, a tyrosinase inhibitor in lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56(2), 597–601, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, T.; Takakura, N.; Urata, M.; Muramatsu, Y.; Tsuboi, M.; Yasuda, K.; Addison, W. N.; Zhang, M.; Matsuo, K.; Nakatomi, C.; Shigeyama-Tada, Y.; Kaneuji, T.; Nakamichi, A.; Kokabu, S. Geranylgeraniol Induces PPARγ Expression and Enhances the Biological Effects of a PPARγ Agonist in Adipocyte Lineage Cells. In vivo (Athens, Greece) 2018, 32(6), 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meigs, TE; Roseman, DS; Simoni, RD. Regulation of 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase degradation by the nonsterol mevalonate metabolite farnesol in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271, 7916–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriyala, S.; Subramanian, T.; Panchatcharam, M.; Ren, H.; McDermott, M. I.; Sunkara, M.; et al. Functional characterization of the atypical integral membrane lipid phosphatase PDP1/PPAPDC2 identifies a pathway for interconversion of isoprenols and isoprenoid phosphates in mammalian cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285(18), 13918–13929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitake, M.; Ogawa, H.; Uebaba, K.; Shidoji, Y. Increase in plasma concentrations of geranylgeranoic acid after turmeric tablet intake by healthy volunteers. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 2010, 46(3), 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.; Morales, A.; Llacuna, L.; Lluis, J. M.; Terrones, O.; Basanez, G.; Fernández-Checa, J. C. Mitochondrial cholesterol contributes to chemotherapy resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer research 2008, 68(13), 5246–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Saito, A. Prevention of second primary tumors by an acyclic retinoid in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 340(13), 1046–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeini, S.H.; Mavaddatiyan, L.; Kalkhoran, Z.R.; Taherkhani, S.; Talkhabi, M. Alpha-ketoglutarate as a potent regulator for lifespan and healthspan: Evidences and perspectives. Experimental Gerontology 2023, 175, 112154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicka, B.; Kruk, J. Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics 2010, 1797(9), 1587–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P. J.; Marcus, A. H.; Bazan, N. G. Farnesol stimulates differentiation in epidermal keratinocytes via PPARα activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275(15), 11484–11491. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, A.; Reddy, P.; Martinez-Redondo, P.; Platero-Luengo, A.; Hatanaka, F.; Hishida, T.; Belmonte, J. C. I. In vivo amelioration of age-associated hallmarks by partial reprogramming. Cell 2016, 167(7), 1719–1733.e12. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Sakimoto, Y.; Imai, K.; Senoo, H.; Shidoji, Y. Induction of an incomplete autophagic response by cancer-preventive geranylgeranoic acid (GGA) in a human hepatoma-derived cell line. The Biochemical journal 2011, 440(1), 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onono, F.; Subramanian, T.; Sunkara, M.; Subramanian, K. L.; Spielmann, H. P.; Morris, A. J. Efficient use of exogenous isoprenols for protein isoprenylation by MDA-MB-231 cells is regulated independently of the mevalonate pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288(38), 27444–27455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, S. E.; Hohl, R. J. Farnesol and geranylgeraniol: prevention and reversion of lovastatin-induced effects in NIH3T3 cells. Lipids 2002, 37(2), 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.Y.; Feyzullazade, N.; Dağ, İ.; Şengel, T. The investigation of in vitro effects of farnesol at different cancer cell lines. Microscopy Research and Technique 2022, 85(8), 2760–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. S.; Kwon, J. K.; Kim, H. R.; Kim, H. J.; Kim, B. S.; Jung, J. Y. Farnesol induces apoptosis of DU145 prostate cancer cells through the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2014, 33(5), 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, T. M.; Burczynski, M. E.; Jez, J. M.; Hung, C. F.; Lin, H. K.; Ma, H.; Ratnam, K. Human 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms (AKR1C1–AKR1C4) of the aldo-keto reductase superfamily: functional plasticity and tissue distribution reveals roles in the inactivation and formation of male and female sex hormones. Biochemical Journal 2003, 351 Pt 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, M.P.; Crespo, R.; de Bravo, M.G. Geraniol and simvastatin show a synergistic effect on a human hepatocarcinoma cell line. Cell Biochemistry and Function 2011, 29(6), 452–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popják, G.; Cornforth, R.; Clifford, K. Inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis by farnesoic acid and its analogues. The Lancet 1960, 275(7137), 1270–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, F.D.; Herman, G.E. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. Journal of Lipid Research 2011, 52(1), 6–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajendran, P.; Al-Saeedi, F.J.; Ammar, R.B.; Abdallah, B.M.; Ali, E.M.; Al Abdulsalam, N.K.; Tejavat, S.; Althumairy, D.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Alamer, S.A.; Bekhet, G.M.; Ahmed, E.A. Geraniol attenuates oxidative stress and neuroinflammation-mediated cognitive impairment in D galactose-induced mouse aging model. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16(6), 5000–5026. [Google Scholar]

- Rekha, K.R.; Sivakamasundari, R.I. Geraniol Protects Against the Protein and Oxidative Stress Induced by Rotenone in an In Vitro Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem Res. 2018, 43(10), 1947–1962, Epub 2018 Aug 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekhof, W. R.; Nickerson, K. Quorum sensing in Candida albicans: farnesol versus farnesoic acid. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, W. B. Fatty aldehyde and fatty alcohol metabolism: Review and importance for epidermal structure and function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2014, 1841(3), 377–392pmc, ncbi.nlm.nih.govpmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roullet, J.B.; Spaetgens, R.L.; Burlingame, T.; Feng, Z.P.; Zamponi, G.W. Modulation of neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels by farnesol. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274(36), 25439–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinsztein, D. C.; Marino, G.; Kroemer, G.; Sapir, A.; Tsur, A.; Koorman, T.; Ching, K.; Mishra, P.; Bardenheier, A.; Sternberg, P. W. Autophagy and aging. Cell 2011, 146, 682–695. 72, Sapir, A., Tsur, A., Koorman, T., Ching, K., Mishra, P., Bardenheier, A., … Sternberg, P. W. (2014). Controlled sumoylation of the mevalonate pathway enzyme HMGS-1 regulates metabolism during aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(37), E3880–E3889.. [Google Scholar]

- Sakane, C.; Shidoji, Y. Reversible upregulation of tropomyosin-related kinase receptor B by geranylgeranoic acid in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Journal of neuro-oncology 2011, 104, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, A.; Tsur, A.; Koorman, T.; Ching, K.; Mishra, P.; Bardenheier, A.; Sternberg, P. W. Controlled sumoylation of the MEVALONATE pathway enzyme HMGS-1 regulates metabolism during aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111(37), E3880–E3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, W. D.; Saputri, F. C.; Widodo, N. geranylgeraniol inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in microglial cells via NF-κB modulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(19), 10543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S.; Zimmermann, A.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Eisenberg, T.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Andryushkova, A.; Pendl, T.; Harger, A.; Madeo, F. Metabolites in aging and autophagy. Microbial Cell 2014, 1(4), 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M. M.; Elsabrouty, R.; Seemann, J.; Jo, Y.; DeBose-Boyd, R. A. The prenyltransferase UBIAD1 is the target of geranylgeraniol in degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Elife 2015, 4, e05560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C. L.; Chyu, M. C.; Pence, B. C.; Yeh, J. K. Effect of geranylgeraniol and green tea polyphenols on glucose homeostasis and bone in obese mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(2), 979. [Google Scholar]

- Shidoji, Y.; Ogawa, H. Natural occurrence of cancer-preventive geranylgeranoic acid in medicinal herbs. Journal of Lipid Research 2004, 45(6), 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidoji, Y.; Tabata, Y. Unequivocal evidence for endogenous geranylgeranoic acid biosynthesized from mevalonate in mammalian cells. Journal of Lipid Research 2019, 60(3), 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidoji, Yoshihiro. Geranylgeranoic acid, a bioactive and endogenous fatty acid in mammals: a review. Journal of Lipid Research 2023, 64.7, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimano, H.; Sato, R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: convergent physiology—divergent pathophysiology. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017, 13(12), 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sláma, K. Insect hormones: more than 50-years after the discovery of insect juvenile hormone analogues (JHA, juvenoids). Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 2013, 6(4), 257–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, S.R.; Li, R.; Dhahbi, J.M.; Yamakawa, A.; Mote, P.; Bodmer, R.; Ocorr, K.; Williams, R.T.; Wang, Y.; Ablao, K.P. Statin treatment increases lifespan and improves cardiac health in Drosophila by decreasing specific protein prenylation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7(6), e39581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindola, H. M.; Fernandes, F. R.; Dos Santos, M. H.; Braga, F. C.; Vieira Filho, S. A. Antinociceptive effect of geranylgeraniol isolated from Pterodon pubescens. Journal of Natural Medicines 2010, 64(4), 402–408. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, Y.; Shidoji, Y. Hepatic monoamine oxidase B is involved in endogenous geranylgeranoic acid synthesis in mammalian liver cells. Journal of Lipid Research 2020, 61(5), 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y.; Omori, M.; Shidoji, Y. Age-dependent decrease of hepatic geranylgeranoic acid content in C3H/HeN mice and its oral supplementation prevents spontaneous hepatoma. Metabolites 2021, 11(9), 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y.; Uematsu, S.; Shidoji, Y. Supplementation with geranylgeranoic acid during mating, pregnancy and lactation improves reproduction index in C3H/HeN mice. Journal of Pet Animal Nutrition 2020, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B. L.; Chin, K. Y. Potential role of geranylgeraniol in managing statin-associated muscle symptoms: a COVID-19 related perspective. Frontiers in Physiology 2023, 14, 1246589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshima, K.; Kondo, T. Analytical method for determination of allylic isoprenols in rat tissues by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry following chemical derivatization with 3-nitrophtalic anhydride. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2008, 47(3), 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetali, S. D. Terpenes and isoprenoids: a wealth of compounds for global use. Planta 2019, 249(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonini, C.; Segatto, M.; Pallottini, V. Impact of sex and age on the mevalonate pathway in the brain: A focus on effects induced by maternal exposure to exogenous compounds. Metabolites 2020, 10(8), 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Sandu, O.; Peppa, M.; Goldberg, T.; Vlassara, H. Diet-derived advanced glycation end products are major contributors to the body’s AGE pool and induce inflammation in healthy subjects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2005, 1043, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, S.; Bostedor, R.; Kurtz, M. M.; Bergstrom, J. D.; Bansal, V. S. Massive production of farnesol-derived dicarboxylic acids in mice treated with the squalene synthase inhibitor zaragozic acid A. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 1998, 355(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin, H.E.; Lincoln, K.; Moshiri, F.; Jensen, P.K.; Qi, Q.; Venkatesh, T.V.; Last, R.L. The Arabidopsis vitamin E pathway gene5-1 mutant reveals a critical role for phytol kinase in seed tocopherol biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2006, 18, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, I.; Pereira, S.; Ugalde, A. P.; et al. Combined treatment with statins and aminobisphosphonates extends longevity in a mouse model of human premature aging. Nature Medicine 2008, 14(7), 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, I. B.; Crispim, M.; Hernández, A.; Katzin, A. M. The Biomedical Importance of the Missing Pathway for Farnesol and Geranylgeraniol Salvage. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 27(24), 8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, N. M.; Wanders, R. J. A.; Poll-The, B. T.; Saudubray, J. M.; Jakobs, C. The metabolism of phytanic acid and pristanic acid in man: a review. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 1998, 21, 697–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vom Dorp, K.; Hölzl, G.; Plohmann, C.; Eisenhut, M.; Abraham, M.; Weber, A.P.; Dörmann, P. Remobilization of phytol from chlorophyll degradation is essential for tocopherol synthesis and growth of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015, 27, 2846–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanders, R. J.; Jakobs, C.; Skjeldal, O. H. Refsum disease. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease 2001, 2, 3303–3321. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Shidoji, Y.; Muto, Y.; Ohishi, N.; Yagi, K. Effects of geranylgeranoic acid in bone: induction of osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of osteoclast formation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2002, 17(1), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, D.; Aboushadi, N.; Shackelford, J.E.; Krisans, S.K. Metabolism of farnesol: Phosphorylation of farnesol by rat liver microsomal and peroxisomal fractions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 230, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J. E.; Burmeister, L.; Brooks, S. V.; Chan, C. C.; Friedline, S.; Harrison, D. E.; Miller, R. A. Rapamycin slows aging in mice. Aging Cell 2012, 11(4), 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. M. Physiology of insect diapause. IV. The brain and prothoracic glands as an endocrine system in the Cecropia silkworm. Biologial Bulletin 1952, 103, 120–138. 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. M. The juvenile hormone of insects. Nature 1956, 178, 212–213. 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. M.; Moorhead, L. V.; Pulis, J. F. Juvenile hormone in thymus, human placenta and other mammalian organs. Nature 1959, 183(4658), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L. D.; Cleland, M. Factors influencing incorporation of mevalonic acid into cholesterol by rat liver homogenates. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1957, 96(1), 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Lin, Z.; Yu, K. Geraniol-mediated osteoarthritis improvement by down-regulating PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and MAPK signals: In vivo and in vitro studies. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 86, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuta, S.; Shidoji, Y. TLR4-mediated pyroptosis in human hepatoma-derived HuH-7 cells induced by a branched-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid, geranylgeranoic acid. Bioscience Reports 2020, 40(4), BSR20194118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youdim, M. B. H.; Bakhle, Y. S. Monoamine oxidase: Isoforms and inhibitors in Parkinson’s disease and depressive illness. British Journal of Pharmacology 2006, 147(S1), S287–S296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Ning, N.; He, F.; Xu, J.; Zhao, H.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y. Targeted Delivery of Geraniol via Hyaluronic Acid-Conjugation Enhances Its Anti-Tumor Activity Against Prostate Cancer. International Journal Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, D. V.; Czarnecka-Herok, J.; Vernier, M.; et al. Cholesterol biosynthetic pathway induces cellular senescence through ERRα. NPJ Aging 2024, 10(5), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Biological activity | References |

| Geraniol | Antioxidant activity | El Azab et al., 2020; Mączka et al., 2020 |

| Anti-inflammatory effect | Wu et al., 2020 | |

| Anticancer activity | Mączka et al., 2020; Kuzu et al., 2021; Cho et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2024 | |

| Synergistic inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis/MVA pathway regulation | Polo et al., 2011 | |

| Anti-obesity effect (browning of white adipose tissue) | Chand et al., 2023 | |

| Neuroprotective effect | Rajendran et al., 2024; Rekha & Sivakamasundari, 2018 | |

| Farnesol | Anticancer activity (apoptosis, mitochondrial depolarization, ER stress, selective cytotoxicity) | Park et al., 2014; Joo et al., 2010; Öztürk et al., 2022 |

| Induction of autophagy | Öztürk et al., 2022 | |

| Anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic effects (NF-κB pathway inhibition) | Joo & Jetten, 2010; Ahmed et al., 2025 | |

| HMGR degradation / regulation of mevalonate pathway | Meigs et al., 1996 | |

| Geranylgeraniol | Hormonal modulation (increased steroid hormones levels) | Ho et al., 2018; Gheith et al., 2023 |

| GGOH protects muscle fibers in type 2 diabetic rats by supporting muscle regeneration, improving glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity / gut microbiota modulation | Ho et al., 2018; Gheith et al., 2023; Jiwan et al., 2024 | |

| Anti-inflammatory and mitochondrial-supportive effects | Chung et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2023; Tan & Chin, 2023 | |

| Neuroprotective effects | Marcuzzi et al., 2016; Saputra et al., 2021 | |

| Analgesic | Spindola et al., 2010 | |

| HMGR degradation / regulation of mevalonate pathway | Fernandes et al., 2013 | |

| Anticancer |

| Compound | Biological activity | References |

| Geranoic acid | Tyrosinase inhibitor | Masuda et al. 2008; Choi et al., 2012 |

| Farnesoic acid | PPARα activation (lipid metabolism and anti-inflammatory regulation) | Rizzo, 2014; O’Brien et al., 2000 |

| Enhanced fatty acid oxidation and reduced triglycerides | Rizzo, 2014; O’Brien et al., 2000 | |

| Promotion of keratinocyte differentiation / skin homeostasis | O’Brien et al., 2000; Rizzo, 2014 | |

| Regulation of the MVA pathway | Rizzo, 2014 | |

| Geranylgeranoic acid and its derivatives | Selective antitumor and pro-apoptotic effects in liver cancer cells; pyroptosis | Shidoji & Tabata, 2019; Shidoji & Ogawa, 2004; Yabuta & Shidoji, 2020 |

| Induction of ER stress and proteostasis disruption (cytotoxic autophagy) | Okamoto et al., 2011; Iwao & Shidoji, 2015 | |

| Reversal of glycolytic to oxphos effect | Iwao & Shidoji, 2015 | |

| Hepatoprotective and anticarcinogenic effects in vivo | Tabata et al., 2021 | |

| Induction of cellular differentiation | Kodaira et al., 2007; Sakane & Shidoji, 2011 | |

| Stimulation of osteoblastic activity / inhibition of osteoclastogenesis | Wang et al., 2002 | |

| Enhanced fertility and embryonic development after dietary supplementation | Tabata et al., 2020 | |

| Physiological roles in hepatic, reproductive, and thymic functions — Shidoji, 2023 | Shidoji, 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).