Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

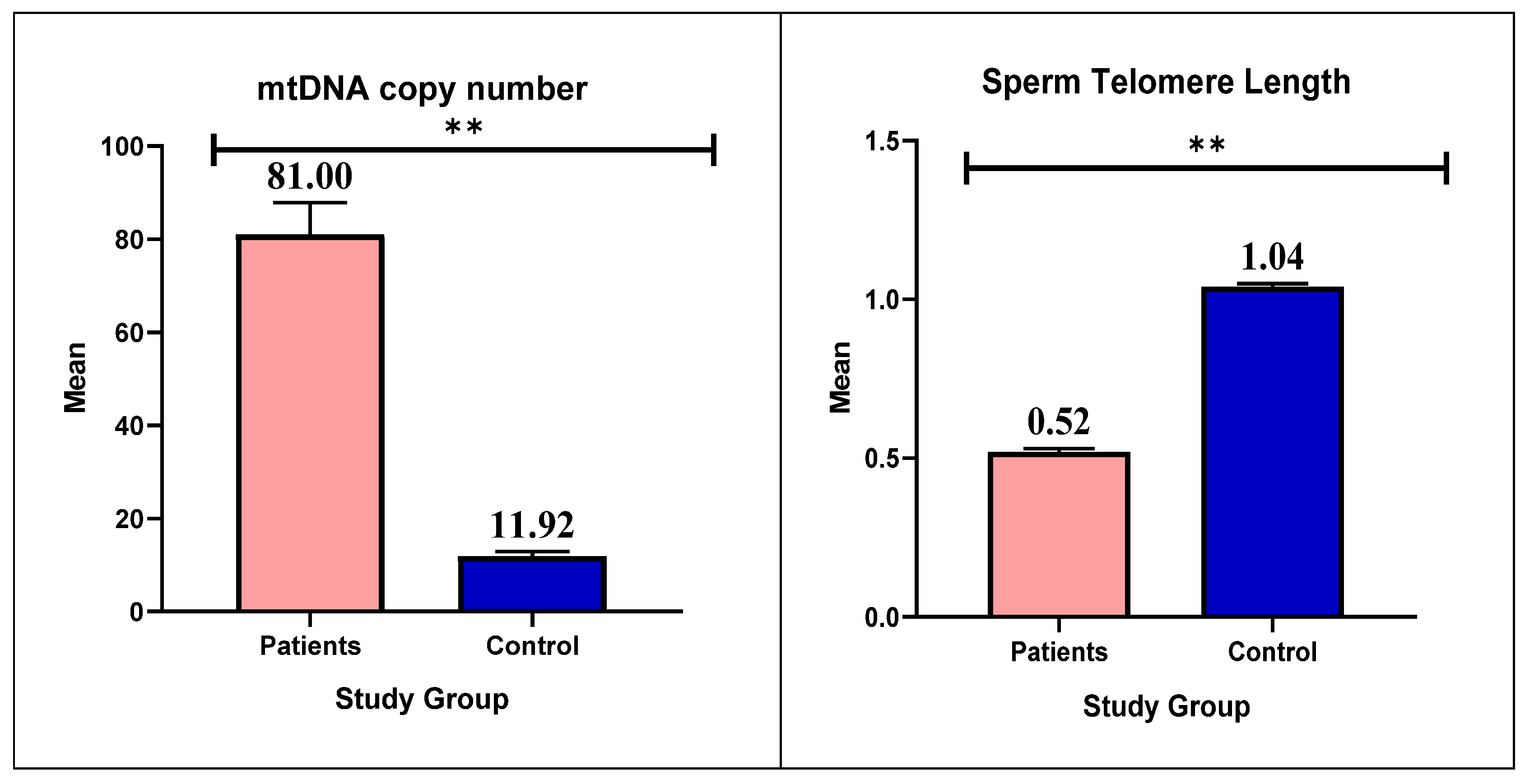

Background/Objectives: Male infertility is one of the major problems in Iraqi health and society, caused by several factors, such as acquired, environmental, and genetic factors. Awareness of the crucial role of telomeres and mitochondria in sperm production and fertility has increased in recent years. This study aimed to evaluate the association between mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) copy number and telomere length in sperm and the degree of infertility in Iraqi males. Methods: Of the 200 study participants, 50 were healthy controls and 150 were infertile. Sperm count, motility, and morphology were assessed by collecting and analyzing semen samples. After DNA extraction, the mitochondrial ND1 gene and the reference nuclear gene GAPDH were analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine the mtDNA copy number. To determine telomere length, another qPCR analysis was used. Results: The mtDNA copy number of infertile men was significantly higher than that of healthy controls with a P-value (0.001). In addition, sperm of the patients group showed a significant reduction in telomere length, (P=0.001). According to the results of the study, male infertility in Iraqi men is associated with a higher number of mtDNA copies and shorter telomere length. DNA damage or a disruption in the mitochondria energy production pathway could be the cause of this association. Conclusions: This study reveals that a higher number of mtDNA copies and shorter telomere lengths are associated with male infertility in Iraqi men. These results highlight the importance of continuing research and exploring new avenues in the field of male infertility.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

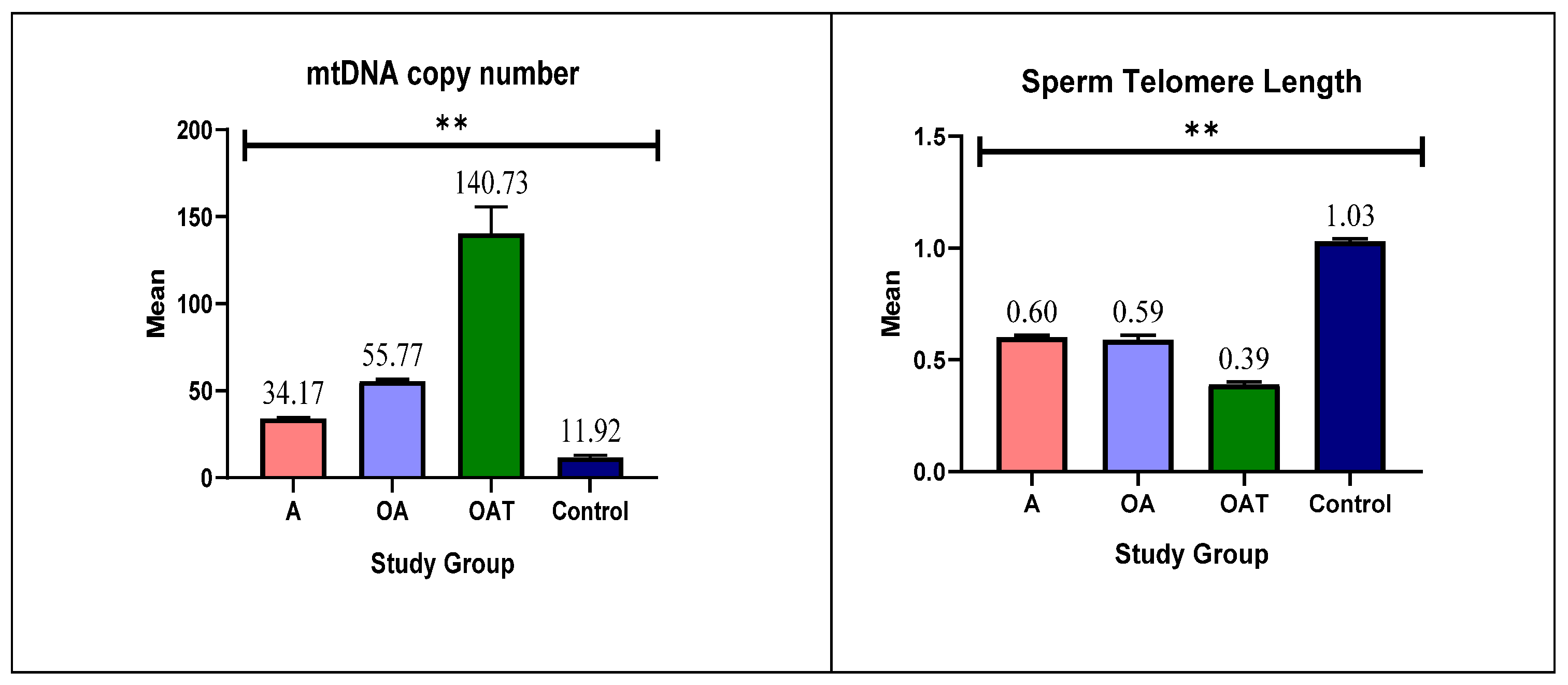

- Group 1 (A): 49 men with asthenozoospermia

- Group 2 (OA): 44 men with oligoasthenozoospermia

- Group 3 (OAT): 57 men with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Semen Analysis

2.4. Sperm DNA Extraction, Purity and Concentration

2.5. Quantification of Sperm mtDNA Copy Number by Real-Time PCR

2.5.1. Principle

2.5.2. Procedure

2.6. Quantification of Sperm Telomere Length (STL) Expression by qPCR

2.6.1. Principles

2.6.2. Procedure and Reaction Components

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Age of the Study Groups

| Parameters | Group | Mean | Std. Error Mean | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Patients | 33.047 | 0.81 | 0.1 N.S |

| Control | 30.880 | 1.43 |

3.2. Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Seminal Fluid Parameters

3.4. mtDNA Copy Number and Telomere Length

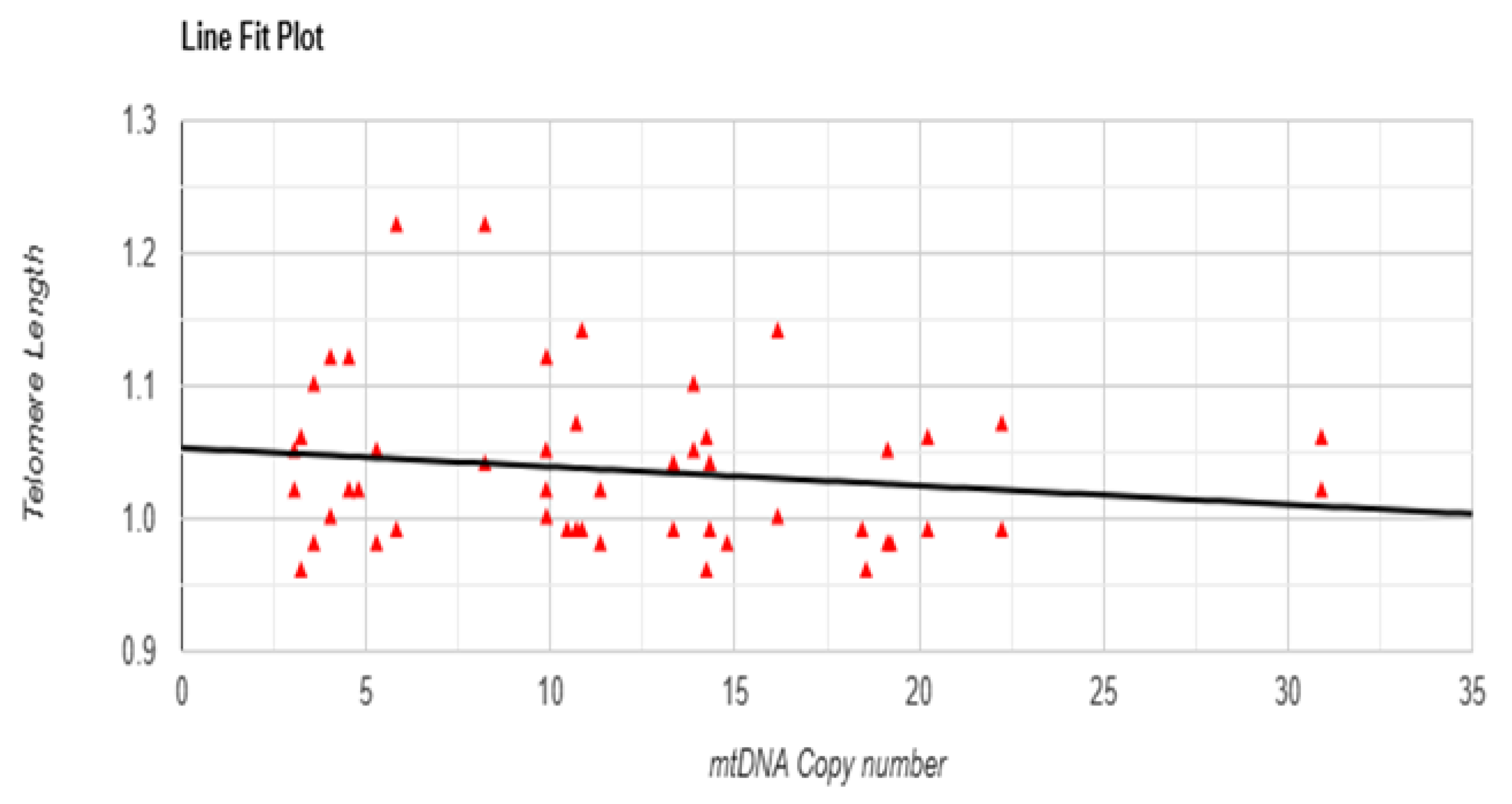

3.5. Correlation Test Between mtDNA Copy Number and Telomere Length

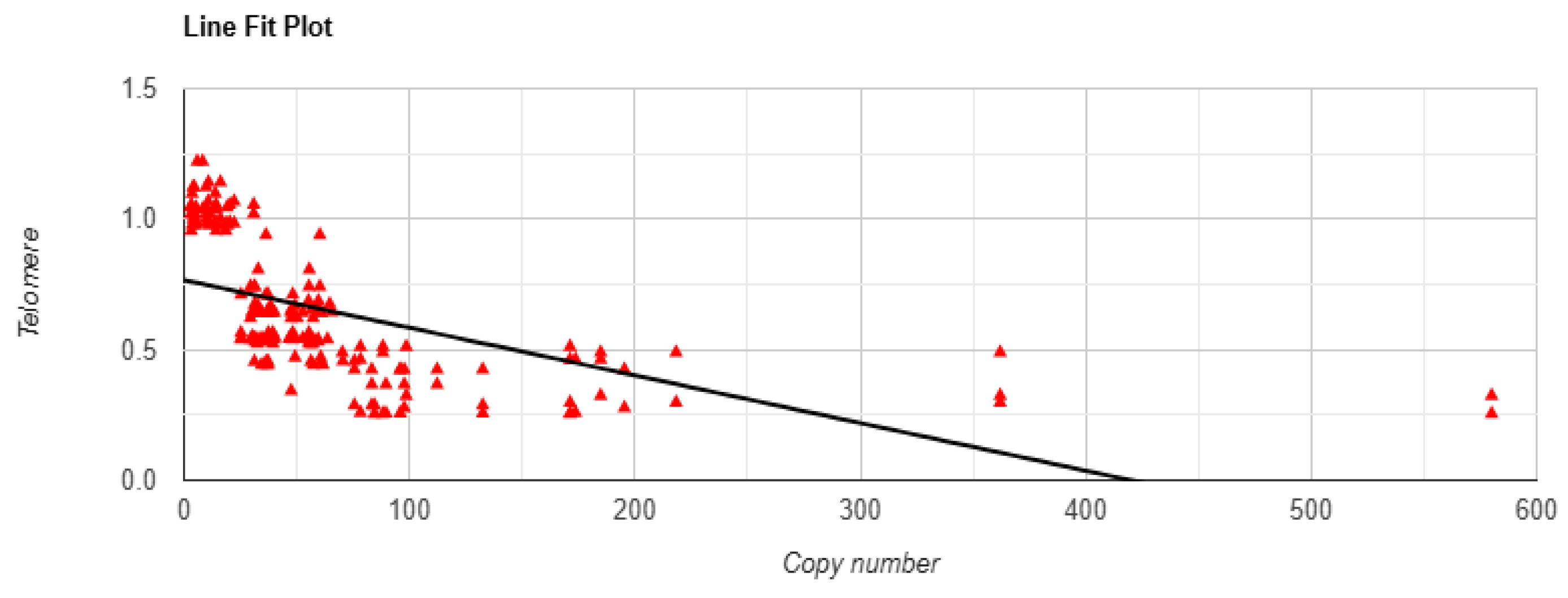

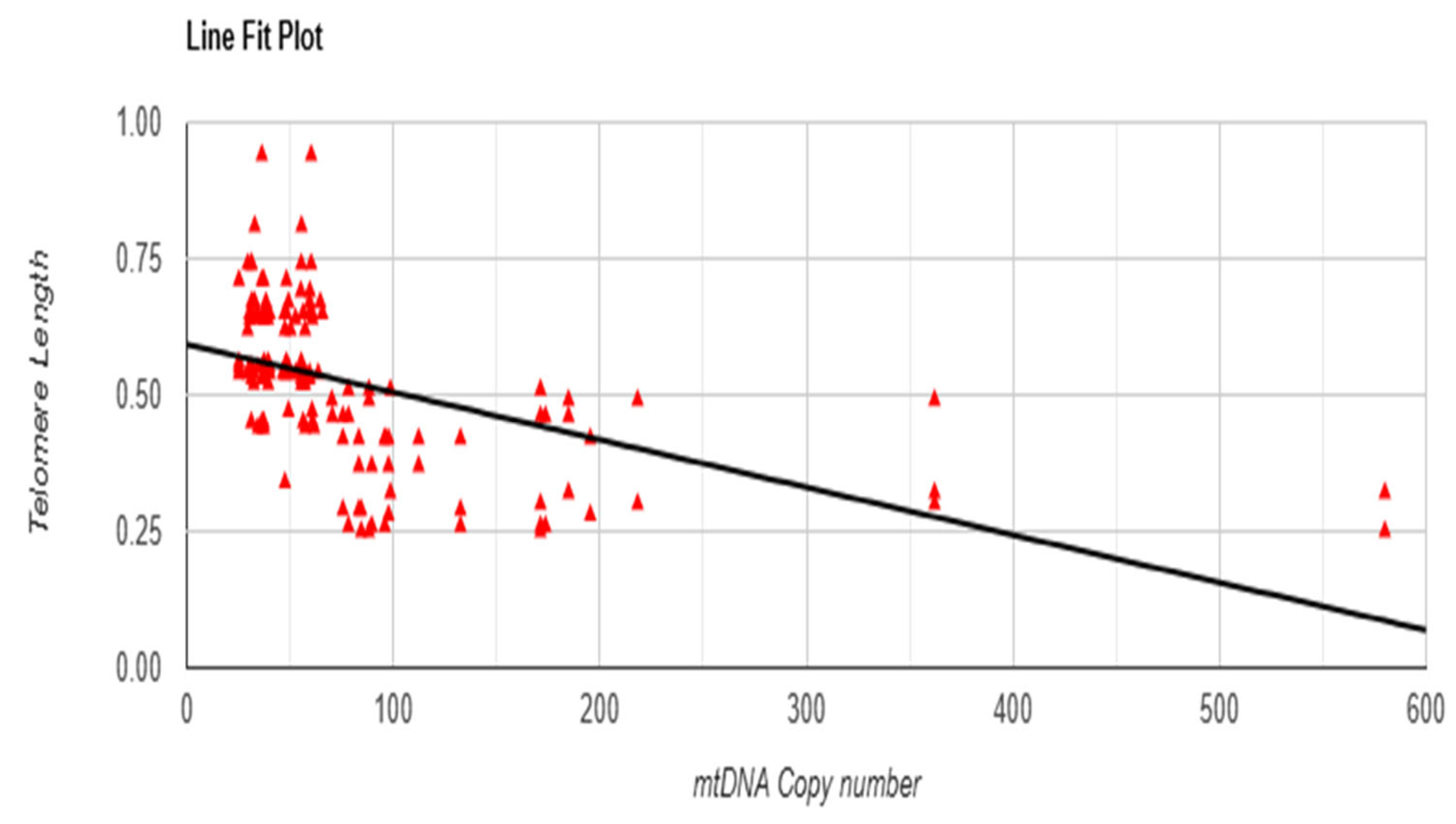

3.6. Linear Regression Test Between mtDNA Copy Number and Telomere Length

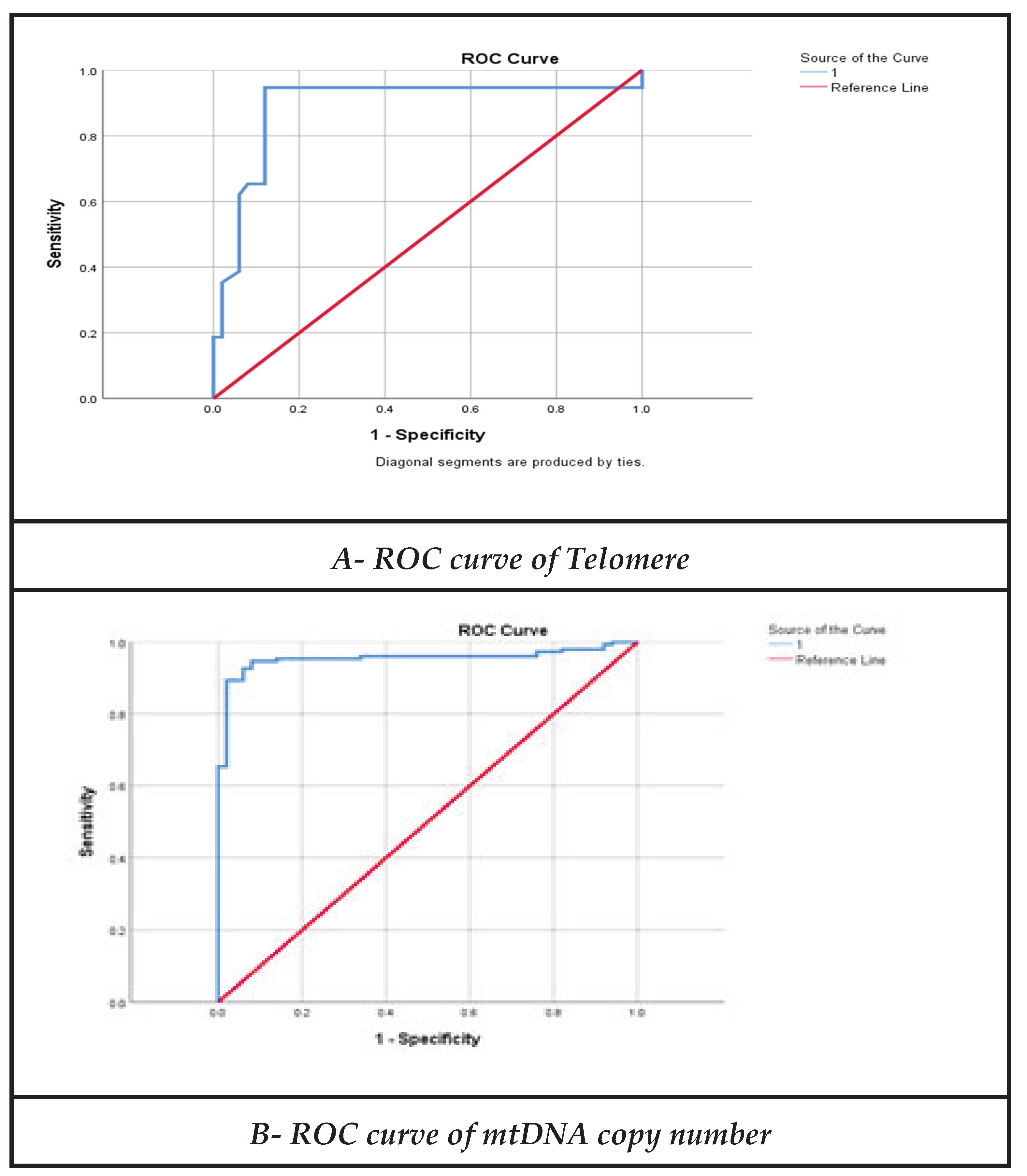

3.7. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Clinical Trial Number

Disclosure statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dourou, P.; Gourounti, K.; Lykeridou, A.; Gaitanou, K.; Petrogiannis, N.; Sarantaki, A. Quality of life among couples with a fertility related diagnosis. Clin. Pract.2023; 13: 251–63. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Baliu-Souza, T.; Turner, K.; Nadiminty, N.; Rambhatla, A.; Agarwal, A.; Krawetz, S.A.; Dupree, J.M.; Saltzman, B.; Schon, S.B.; et al. Sperm centriole assessment identifies male factor infertility in couples with unexplained infertility – a pilot study. Eur. J. Cell Biol.2022; 101: 151243. [CrossRef]

- Legese, N.; Tura, A.K.; Roba, K.T.; Demeke, H. The prevalence of infertility and factors associated with infertility in Ethiopia: analysis of Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). PLoS One.2023;18: e0291912. [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, P.S.; Gupta, A.S. Causes and prevalence of factors causing infertility in a public health facility. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci.2019; 12: 287–93. [CrossRef]

- Katz-Wise, S.L.; Priess, H.A.; Hyde, J.S. Gender-role attitudes and behavior across the transition to parenthood. Dev. Psychol.2010; 46: 18–28. [CrossRef]

- Hussam, F.; AbdulhameedKhudair, S.; Alkhafaje, W.K.; Alnassar, Y.S.; Kaoud, R.M.; Najm Abed, A.; Jabbar, H.S.; Numan, H.A. A cross-sectional study regarding infertility among women in Iraq. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Cancer Res.2022; 8: 47–52. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, T.; Burhan, S.; Ali Hamza, N.; Kathem, A. Ratio of male to female infertility in Baghdad Al-Karkh (2015–2020). Teikyo Med. J.2021; 44: 2197–207.

- Rossmann, M.P.; Dubois, S.M.; Agarwal, S.; Zon, L.I. Mitochondrial function in development and disease. Dis Model Mech.2021;14. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Rodriguez, S. Mitochondrial DNA: inherent complexities relevant to genetic analyses. Genes (Basel).2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Moustakli, E.; Zikopoulos, A.; Skentou, C.; Bouba, I.; Tsirka, G.; Stavros, S.; Vrachnis, D.; Vrachnis, N.; Potiris, A.; Georgiou, I.; et al. Sperm mitochondrial content and mitochondrial DNA to nuclear DNA ratio are associated with body mass index and progressive motility. Biomedicines.2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Filograna, R.; Mennuni, M.; Alsina, D.; Larsson, N-G. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in human disease: the more the better? FEBS Lett.2021; 595: 976–1002. [CrossRef]

- Maggo, S.; North, L.Y.; Ozuna, A.; Ostrow, D.; Grajeda, Y.R.; Hakimjavadi, H.; Cotter, J.A.; Judkins, A.R.; Levitt, P.; Gai, X. A method for measuring mitochondrial DNA copy number in pediatric populations. Front. Pediatr.2024;12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Bu, D.; Liu, H.; Xia, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Pan, H.; Pei, P.; Zheng, X.; et al. Deletion of a 4977-bp fragment in the mitochondrial genome is associated with mitochondrial disease severity. PLoS One.2015;10: e0128624. [CrossRef]

- Faeqali Jan, M.; Muneer Al-Khafaji, H.; Hasan Al-Saadi, B.; Aneed Al-Saedi, M.K. Assessment of interleukin-8 in bronchial asthma in Iraq. Arch. Razi Inst.2021; 76: 913–23. [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, A.; Capossela, S.; Fränkl, G.; Baur, M.; Pötzel, T.; Stoyanov, J. Oxidative status predicts quality in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther.2017; 8: 3. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Smith, D.L.; Esteves, K.; Drury, S. Telomere length measurement by qPCR – summary of critical factors and recommendations for assay design. Psychoneuroendocrinology.2019; 99: 271–8. [CrossRef]

- SPSS. Statistical package for the social sciences.2019: Version 26.

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc.2008; 3: 1101–8. [CrossRef]

- Riedel, G.; Rüdrich, U.; Fekete-Drimusz, N.; Manns, M.P.; Vondran, F.W.R.; Bock, M. An extended ΔCT-method facilitating normalisation with multiple reference genes suited for quantitative RT-PCR analyses of human hepatocyte-like cells. PLoS One.2014; 9: e93031. [CrossRef]

- Mengel-From, J.; Thinggaard, M.; Dalgård, C.; Kyvik, K.O.; Christensen, K.; Christiansen, L. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood cells declines with age and is associated with general health among elderly. Hum. Genet.2014; 133: 1149–59. [CrossRef]

- Rahman Aisyah, C.; Mizuno, Y.; Masuda, M.; Iwamoto, T.; Yamasaki, K.; Uchida, M.; Kariya, F.; Higaki, S.; Konishi, S. Association between sperm mitochondrial DNA copy number and concentrations of urinary cadmium and selenium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.2024; 202: 2488–2500. [CrossRef]

- VahediRaad, M.; Firouzabadi, A.M.; TofighiNiaki, M.; Henkel, R.; Fesahat, F. The impact of mitochondrial impairments on sperm function and male fertility: a systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol.2024; 22: 83. [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Braga, P.C.; Rebelo, I.; Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, M.G. Mitochondria quality control and male fertility. Biology (Basel).2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Virk, G.; Ong, C.; du Plessis, S.S. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J. Mens Health.2014; 32: 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Wai, T.; Ao, A.; Zhang, X.; Cyr, D.; Dufort, D.; Shoubridge, E.A. The role of mitochondrial DNA copy number in mammalian fertility. Biol. Reprod.2010; 83: 52–62. [CrossRef]

- Mai, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Han, B.; Sun, Z. A narrative review of mitochondrial dysfunction and male infertility. Transl.Androl. Urol.2024;13(9): 2134–2145. [CrossRef]

- Song, G.J.; Lewis, V. Mitochondrial DNA integrity and copy number in sperm from infertile men. Fertil. Steril.2008; 90: 2238–44. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Huffman, A.; Brandon, N.; Labrie, S.; Tougias, E.; Lynch, K.; Rahil, T.; Sites, C.K.; Pilsner, J.R. Associations of sperm mitochondrial DNA copy number and deletion rate with fertilization and embryo development in a clinical setting. Hum.Reprod.2019; 34(1): 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Kauppila, T.E.S.; Motori, E.; Li, X.; Atanassov, I.; Folz-Donahue, K.; Bonekamp, N.A.; Albarran-Gutierrez, S.; Stewart, J.B.; Larsson, N.-G. Increased total mtDNA copy number cures male infertility despite unaltered mtDNA mutation load. Cell Metab.2017; 26: 429-436.e4. [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulos, E.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Kalliora, C.; Fragou, D.; Docea, A.O.; Vakonaki, E.; Tsoukalas, D.; Calina, D.; Buga, A.M.; Georgiadis, G.; et al. The association of female and male infertility with telomere length (review). Int. J. Mol. Med.2019; 44: 375–389. [CrossRef]

- Darmishonnejad, Z.; Tavalaee, M.; ZareiKheirabadi, M.; Zohrabi, D.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. Relationship between sperm telomere length and sperm quality in infertile men. Andrologia.2020;52: e13546. [CrossRef]

- Amir, S.; Vakonaki, E.; Tsiminikaki, K.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Michopoulou, V.; Flamourakis, M.; Kalliantasi, K.; Karzi, V.; Fragkiadaki, P.; Renieri, E.A; et al. Sperm telomere length: diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in male infertility (review). World Acad. Sci. J.2019; 1: 259–263. [CrossRef]

- Margiana, R.; Gupta, R.; Al-Jewari, W.M.; Hjazi, A.; Alsaab, H.O.; Mustafa, Y.F.; Singh, R.; Thaibt, R.; Alkhayyat, S.; Ibrahim, A.J. Evaluation of telomere length, reactive oxygen species, and apoptosis in spermatozoa of patients with oligospermia. Cell Biochem. Funct.2024;42: e3935. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, V.S.; Shahid, M.; Deo, P.; Fenech, M. Reduced SIRT1 and SIRT3 and lower antioxidant capacity of seminal plasma is associated with shorter sperm telomere length in oligospermic men. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2024;25. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, K.; Vatsalaswamy, P.; Manvikar, P. The association of male infertility with telomere length: a case control study. Indian J. Clin. Anat. Physiol.2021; 8: 325–32. [CrossRef]

- Torra-Massana, M.; Barragán, M.; Bellu, E.; Oliva, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Vassena, R. Sperm telomere length in donor samples is not related to ICSI outcome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet.2018; 35: 649–57. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Zha, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z.; Li, M.. New insights from bidirectional Mendelian randomization: causal relationships between telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in aging biomarkers. Aging (Albany NY).2024; 16: 7387–404. [CrossRef]

- Tyrka, A.R.; Carpenter, L.L.; Kao, H.-T.; Porton, B.; Philip, N.S.; Ridout, S.J.; Ridout, K.K.; Price, L.H. Association of telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number in a community sample of healthy adults. Exp. Gerontol.2015; 66: 17–20. [CrossRef]

- Moustakli, E.; Zikopoulos, A.; Skentou, C.; Dafopoulos, S.; Stavros, S.; Dafopoulos, K.; Drakakis, P.; Georgiou, I.; Zachariou, A. Association of obesity with telomere length in human sperm. J. Clin. Med.2024; 13:2150. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-J.; Pang, M.-G. Mitochondrial functionality in male fertility: From spermatogenesis to fertilization. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland)2021;10: 10010098. [CrossRef]

| Primer | Sequence (5ʹ→3ʹ direction) | Products Size bp | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ND1 for Copy number using qPCR (58 °C) | |||

| Forward | ATTCGATGTTGAAGCCTGAGACT | 108 | [13] |

| Reverse | TGACCCTTGGCCATAATATGATT | ||

| GAPDH for Copy number using qPCR (58 °C) | |||

| Forward | TGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCC | 120 | [14] |

| Reverse | TCCTTCCACGATACCAAAG | ||

| Telomere primer (55 °C) | |||

| Forward | CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT | [15] | |

| Reverse | GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT | ||

| Single Copy gene Reaction (SCR) primers (55 °C) | |||

| Forward | CAGCAAGTGGGAAGGTGTAATCC | 78 | [15] |

| Reverse | CCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGTACAA | ||

| Parameters | Group | Chi-square | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Control | ||||

| Family History | Yes | 67 (44.67%) | 1 (2%) | 30.42 | 0.001** |

| No | 83 (55.33%) | 49 (98%) | |||

| Alcohol | Yes | 66 (44%) | 6 (12%) | 16.67 | 0.001** |

| No | 84 (56%) | 44 (88%) | |||

| Smoking | Yes | 48 (32%) | 21 (42%) | 1.66 | 0.2. |

| No | 102 (68%) | 29 (58%) | |||

| Treatment | Yes | 102 (68%) | 12 (24%) | 29.62 | 0.001** |

| No | 48 (32%) | 38 (76%) | |||

| Wife Miscarriage |

Yes | 25 (16.67%) | 0 | 9.52 | 0.002 |

| No | 125 (83.33%) | 50 (100%) | |||

| Education Level | No. Edu | 62 (41.33%) | 7 (14%) | 84.46 | 0.001** |

| P.S | 11 (7.33%) | 0 | |||

| S.S | 57(38%) | 2 (4%) | |||

| University | 20 (13.33%) | 41 (82%) | |||

| Infertility Duration | 1-5 Years | 74 (49.33%) | 0 | 200.00 | 0.001** |

| 6-10 Years | 32 (21.33%) | 0 | |||

| ˃10 years | 44(29.33%) | 0 | |||

| No | 0 | 50 | |||

| Parameters | Group | Mean | Std. Error Mean | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (ml) | Patients | 3.110 | 0.14 | 0.001** |

| Control | 4.590 | 0.12 | ||

| Sperm count (million/ ml) | Patients | 15.947 | 1.59 | 0.001** |

| Control | 39.800 | 2.44 | ||

| Character | Patients | Control | ||

| Morphology of Sperm | Normal | 100 (66.67%) | 50 | 0.001** |

| Abnormal | 50 (33.33%) | 0 | ||

| Sperm Motility | PR | 89 (59.33%) | 50 | 0.001** |

| NP | 30 (20%) | 0 | ||

| IM | 31 (20.67%) | 0 |

| Parameters | Area | Cutoff | Explanation | P- value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA Copy number |

0.954 | 25.24 | Excellent | 0.001** | 95% | 92% |

| Sperm Telomere Length | 0.89 | 0.95 | Very Good | 0.001** | 95% | 88% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).