1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), represents one of the most significant global public health events of recent decades. Since its emergence in December 2019, the infection has spread worldwide, leading to hundreds of millions of cases and substantial mortality. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern due to its rapid transmission and its profound strain on healthcare systems [

1,

2].

Although the acute phase of the pandemic has abated following widespread natural infection and vaccination, increasing evidence indicates that many individuals experience persistent or newly emerging symptoms beyond the acute illness, collectively known as post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) or long COVID [

3,

4]. These manifestations are diverse and include fatigue, cognitive impairment, respiratory and cardiovascular dysfunction, as well as metabolic and endocrine abnormalities [

4,

5,

6]. The endocrine system appears particularly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2-associated injury, and these long-term effects can significantly impact quality of life, healthcare utilization, and economic productivity [

5,

6].

SARS-CoV-2 exerts systemic effects beyond the respiratory tract, largely due to its use of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is highly expressed in several endocrine tissues, including pancreatic β-cells and thyroid follicular cells [

7]. Proposed mechanisms of endocrine involvement include direct cytopathic effects, immune-mediated injury driven by cytokine release, oxidative stress, and persistent immune dysregulation [

8,

9].

The interaction between COVID-19 and glucose metabolism is particularly complex and bidirectional. Individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) are at increased risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes [

10,

11], while accumulating evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 infection may precipitate newly diagnosed diabetes or destabilize pre-existing disease [

12,

13]. Meta-analyses report a 40–65% increased risk of incident diabetes following COVID-19, affecting both type 1 and type 2 phenotypes [

14,

15]. Poor glycemic control during acute infection is also associated with higher rates of complications such as septic shock, acute kidney injury, and cardiovascular events [

16].

Thyroid dysfunction has likewise been widely reported among COVID-19 survivors. The high expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the thyroid supports its susceptibility to viral injury [

6], while exaggerated immune activation may lead to subacute thyroiditis, transient thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, or autoimmune thyroid disease, including Hashimoto and, more rarely, Graves disease [

17,

18]. Although many changes are reversible, recent evidence indicates that a subset of patients develops persistent thyroid autoimmunity, potentially through molecular mimicry involving thyroid antigens such as TPO and Tg [

19,

20].

While SARS-CoV-2 infection is increasingly recognized as a potential trigger for endocrine autoimmunity [

21,

22], major gaps remain. Most studies have limited follow-up durations of 6 to 24 months, and only a few extend beyond three years [

21,

22,

23]. Long-term data are essential for developing evidence-based strategies for surveillance and early intervention in endocrine complications after COVID-19.

Based on these considerations, the present study reassessed a cohort of adults hospitalized for COVID-19 in 2020–2021, evaluating metabolic and thyroid status four years after the initial infection. The primary objective was to determine the prevalence of incident type 2 diabetes and post-COVID thyroid autoimmunity and to examine potential associations between acute-phase severity and long-term endocrine outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study was designed as a retrospective observational cohort study conducted at a single center, the Clinical Hospital of Pneumophthisiology and Infectious Diseases in Brașov, Romania. The study population was selected from the hospital's electronic database and included adult patients (≥18 years) hospitalized with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR or antigen testing between August 1, 2020, and July 31, 2021. Out of all hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during this period, 1009 adult patients without a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disorders were selected.

Initially, the inclusion criteria for the post-COVID follow-up phase targeted only those patients who had experienced severe or critical forms of the disease, based on the hypothesis that they would be at higher risk for endocrine sequelae. Subsequently, due to recruitment difficulties and the limited number of patients willing to undergo follow-up evaluation, the eligibility criteria were expanded to include any eligible patient from the initial cohort, regardless of the clinical severity of the initial COVID-19 illness.

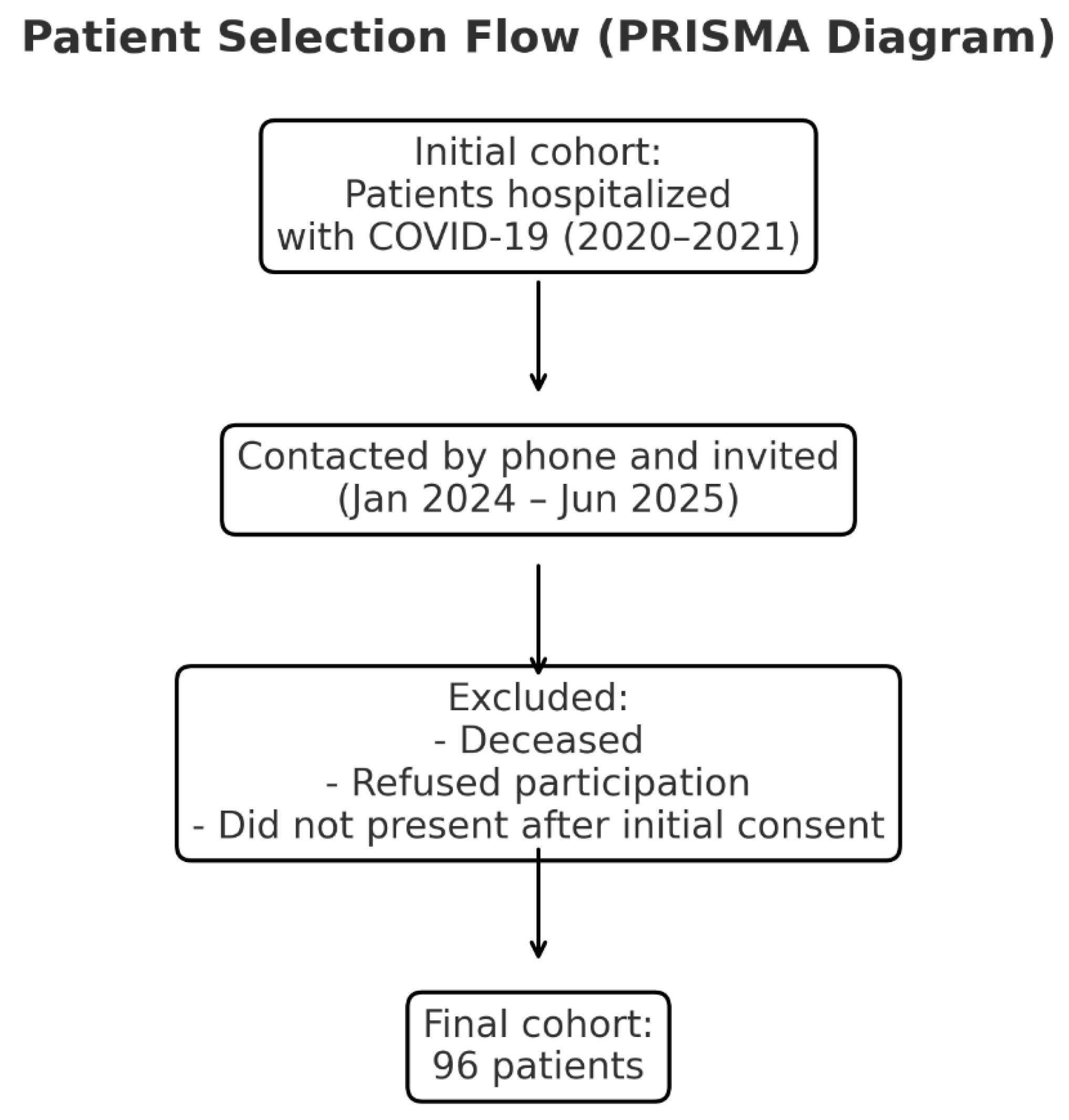

Between January 2024 and June 2025, eligible patients were contacted by phone and invited to participate in a clinical and paraclinical reassessment at the same hospital. Of the 1009 eligible patients, 96 formed the final study group. The remaining patients either died during the follow-up period, declined participation, or did not attend the scheduled evaluation despite initially agreeing verbally.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital of Pneumophthisiology and Infectious Diseases in Brașov (approval no. 9328/June 20, 2024) and by the Ethics Committee of the “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu (approval no. 16/November 25, 2022). COVID-19 diagnosis was based on clinical presentation and confirmed by laboratory testing.

Figure 1.

Legend: PRISMA-style flowchart showing patient recruitment and inclusion process. The final cohort consisted of 96 eligible participants after exclusion of deceased patients, non-responders, and those who did not attend follow-up evaluation.

Figure 1.

Legend: PRISMA-style flowchart showing patient recruitment and inclusion process. The final cohort consisted of 96 eligible participants after exclusion of deceased patients, non-responders, and those who did not attend follow-up evaluation.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data were initially compiled in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365). Preprocessing included column trimming, normalization of category labels and internal consistency checks between marginal totals and unions. Statistical analyses were performed in Python 3.11 using pandas 2.2, NumPy 1.26, SciPy 1.11, and statsmodels 0.14. Group comparisons used Pearson’s chi-square test. Where multiple hypotheses were assessed, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate procedure with a two-sided significance threshold of alpha equals to 0.05. Visualization was generated with Matplotlib 3.8 and Seaborn 0.13. Excel was also used in parallel for quick tabulations and charts to cross-check results.

2.3. Aim and Objectives

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of long-term endocrine sequelae in patients with a history of COVID-19, with a specific focus on the development of diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction—whether functional, autoimmune, or structural—four years after the acute infection. The underlying hypothesis was that patients hospitalized for COVID-19, even in the absence of prior endocrine disease, might experience delayed disturbances in glucose metabolism and thyroid autoimmunity, potentially leading to persistent clinical consequences and an impact on overall health status.

In addition to quantifying the burden of long-term endocrine complications, the study sought to investigate several key aspects of this association. First, we examined whether the severity of the acute COVID-19 episode influences the subsequent risk of developing diabetes or thyroid autoimmunity. We additionally assessed whether stress-induced hyperglycemia during hospitalization could predict the later onset of type 2 diabetes. Moreover, the role of demographic and clinical factors—including age, sex, and comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia—was explored in relation to endocrine outcomes. Given possible shared pathogenic pathways, we also evaluated the interplay between thyroid dysfunction and new-onset diabetes following COVID-19. Finally, by identifying the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine disorder, we aimed to estimate the cumulative long-term endocrine burden associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants in this study were adults with a confirmed history of COVID-19 who had been hospitalized during the period 2020–2021 and who did not have a prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease at the time of their initial admission. Only patients who agreed to take part in the follow-up evaluation and attended the scheduled clinical assessment four years after the acute episode were included. Individuals were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, were pregnant at the time of reassessment, or had a documented history of pre-existing diabetes or thyroid pathology prior to COVID-19 infection. Additional exclusion criteria included patients who died during the interim period, those who declined participation, and individuals who could not be contacted for the 4-year evaluation.

2.5. Data Collection and Procedures

Data were collected at two time points: (i) during the acute COVID-19 hospitalization and (ii) at a 4-year post-infection reassessment (

Table 1).

2.5.1. Acute Phase Data (Hospital Admission, 2020–2021)

Clinical data collected during hospitalization included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, presenting symptoms, disease severity, treatment received, oxygen or ventilatory support, length of stay, and clinical outcome. Laboratory parameters included admission blood glucose, inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen, ESR), hematological and coagulation indices (white blood cells, lymphocytes, platelets, D-dimer), tissue injury markers (AST, ALT, LDH), and renal function tests (urea, creatinine). Imaging investigations included chest X-ray or baseline and follow-up thoracic CT, along with the lowest recorded peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) in room air.

2.5.2. Four-Year Reassessment (2024–2025)

Four years after the acute episode, the participants underwent clinical and laboratory reassessment. Data collected included demographic information, updated medical history, and laboratory tests such as fasting glucose, inflammatory and hematologic markers, tissue injury markers, and renal function tests. Thyroid function was evaluated through TSH, FT4, FT3, and thyroid autoantibodies (anti-TPO, anti-Tg). Thyroid ultrasound was performed to determine structural changes including patterns suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis, nodules, or cysts.

2.6. Severity Classification of COVID-19

COVID-19 severity was classified based on national and international guidelines [

24,

25]. Mild cases were defined by upper respiratory symptoms without hypoxemia or radiological evidence of pneumonia. Moderate cases presented radiologic pneumonia without hypoxemia (SpO₂ > 94%). Severe disease included pneumonia with at least one of the following: respiratory rate > 30/min, severe respiratory distress, or SpO₂ < 90%. Critical cases included patients with respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, septic shock, or acute thrombotic events.

2.7. Analytical Approach

To evaluate the relationship between acute COVID-19 severity and the risk of long-term endocrine sequelae, patients were grouped into four categories (mild, moderate, severe, and critical), and the prevalence of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity at 4 years was compared across groups to explore potential severity-dependent effects. The predictive value of stress-induced hyperglycemia at admission for subsequent diabetes was examined by comparing the incidence of diabetes among patients with hyperglycemia versus normoglycemia during hospitalization.

To identify risk factors associated with post-COVID endocrine sequelae, subgroup analyses were performed based on sex, age (<60 vs. ≥60 years), pre-existing comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia), and acute COVID-19 severity. The analyses specifically investigated: (i) the influence of sex on thyroid autoimmunity, (ii) age-related susceptibility to metabolic and immune dysregulation, (iii) the role of comorbidities, particularly obesity and dyslipidemia, in the development of new-onset diabetes, and (iiii) the possible link between severe/critical COVID-19, systemic inflammation, corticosteroid use, and long-term endocrine dysfunction.

The relationship between thyroid autoimmunity and post-COVID diabetes was explored by stratifying patients based on thyroid autoantibodies and diabetes status to evaluate potential co-occurrence. The overall post-COVID endocrine burden was estimated by calculating the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine disorder (type 2 diabetes and/or autoimmune thyroiditis).

3. Results

The final study cohort included 96 non-diabetic patients without previously known thyroid disease, all of whom had been hospitalized for COVID-19 during 2020–2021 and were re-evaluated four years after the acute episode.

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The cohort consisted of 44 men (45.8%) and 52 women (54.2%), with a balanced sex distribution. Patient age ranged from 35 to 77 years. The largest age group was 60–69 years (33.3%), followed by 50–59 years (25.0%) and 40–49 years (22.9%). Only 14.6% of the participants were aged 70 or older, and the youngest group (30–39 years) accounted for 4.2% of the study population. This age distribution likely reflects the fact that moderate to severe COVID-19, associated with a higher risk of endocrine sequelae, was more frequently observed in middle-aged and older adults, consistent with existing literature.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients by age group.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients by age group.

| Age group (years) |

Number of patients (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| 30–39 |

4 |

4.2% |

| 40–49 |

22 |

22.9% |

| 50–59 |

24 |

25.0% |

| 60–69 |

32 |

33.3% |

| ≥70 |

14 |

14.6% |

Regarding the severity of the disease during the acute phase of COVID-19, almost half of the patients (46.9%) had experienced severe or critical disease, while the remaining 53.1% had mild or moderate forms. This distribution ensured the inclusion of a significant proportion of patients at high risk of long-term complications, while preserving statistical relevance through the inclusion of less severe cases.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to acute COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to acute COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical severity |

Number of patients |

Percentage (%) |

| Mild |

26 |

27.1% |

| Moderate |

25 |

26.0% |

| Severe |

37 |

38.5% |

| Critical |

8 |

8.3% |

3.2. Relationship Between Acute COVID-19 Severity and the Risk of Subsequent Endocrine Disorders

3.2.1. Post-COVID-19 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

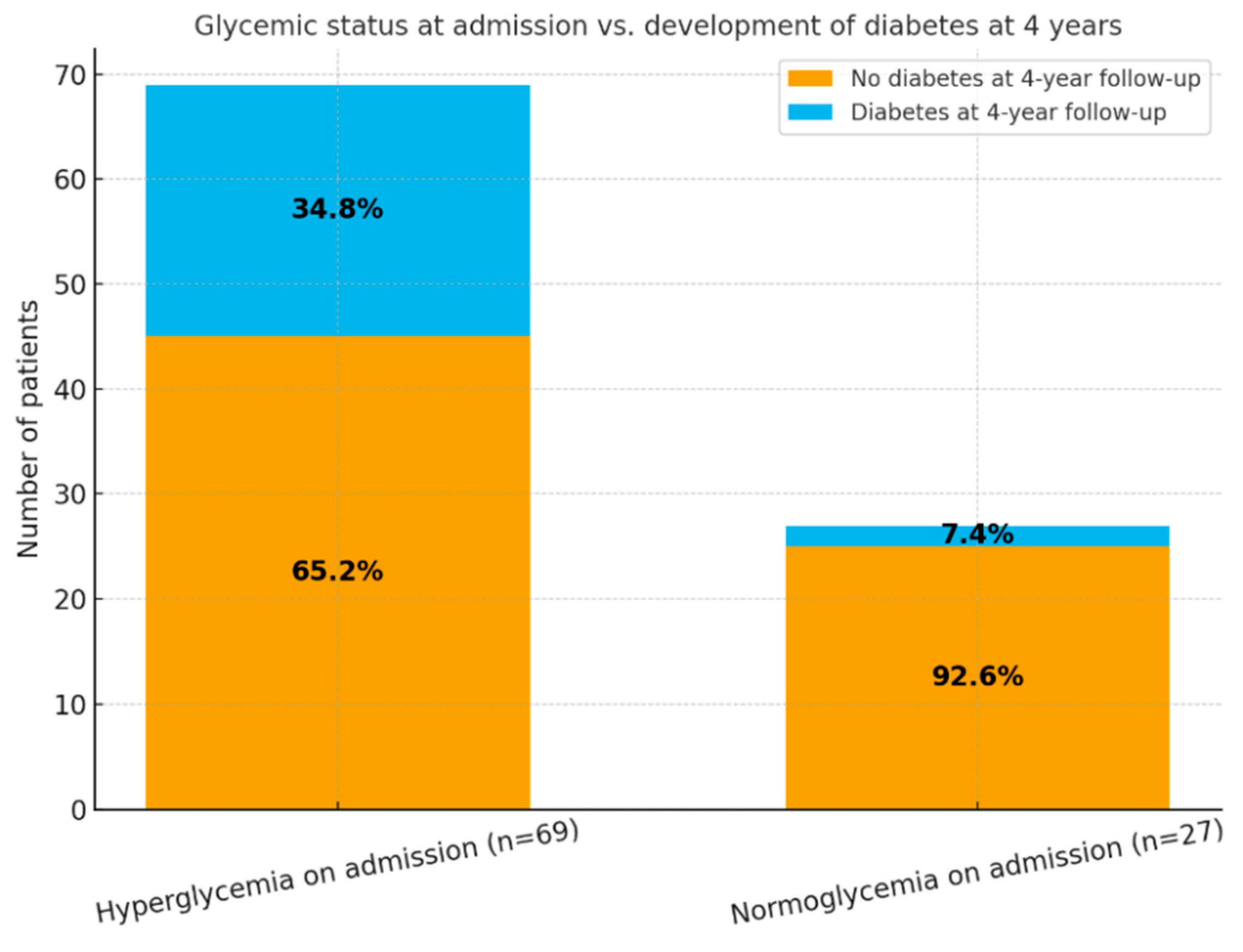

At the time of hospitalization for acute COVID-19, 69 patients (71.9%) presented with hyperglycemia, while 27 patients (28.1%) were normoglycemic. At the 4-year follow-up, 26 patients (27.1%) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Of these, 24 patients originated from the hyperglycemic group, accounting for 34.8% of this subgroup, while only 2 patients (7.4%) from the normoglycemic subgroup developed diabetes.

These findings suggest a significant association between acute-phase hyperglycemia during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the later development of persistent glycemic abnormalities. Specifically, hyperglycemic patients had an approximately fivefold higher risk of developing diabetes compared to those who were normoglycemic at admission. This highlights the predictive potential of stress-induced hyperglycemia during acute COVID-19 for long-term metabolic dysfunction.

Table 4 and

Figure 2 illustrate the evolution of glycemic status in relation to the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Overall, the results emphasize the need for periodic monitoring of glucose profiles in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, even after full clinical recovery, to enable early detection of post-infectious diabetes mellitus.

Patients who exhibited hyperglycemia upon hospital admission for COVID-19 had a significantly higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4-year follow-up compared to those with normal blood glucose levels at admission.

The distribution of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases at 4 years after acute COVID-19, stratified by clinical severity, showed that patients with severe forms of COVID-19 had the highest prevalence of diabetes (40.5%), followed by those with moderate forms (32.0%). Among patients who experienced critical COVID-19, the prevalence was 12.5%, while only 7.7% of those with mild disease developed diabetes. These findings suggest a correlation between the initial severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Table 5.

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4 years according to COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 5.

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4 years according to COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical Severity |

Number of Patients (n) |

T2DM Cases (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Mild |

26 |

2 |

7.7% |

| Moderate |

25 |

8 |

32.0% |

| Severe |

37 |

15 |

40.5% |

| Critical |

8 |

1 |

12.5% |

Given that hyperglycemia at admission is more commonly observed in severe COVID-19 cases, these findings highlight that stress-induced hyperglycemia during the acute phase of the infection may have represented an important risk factor for the later development of diabetes. Indeed, the majority of T2DM cases at 4 years occurred in patients who already exhibited elevated glucose levels during initial hospitalization.

3.2.2. Post-COVID-19 Thyroid Alterations: Functional and Structural Changes

At the 4-year follow-up, the assessment of thyroid alterations revealed notable differences based on the clinical severity of the initial COVID-19 episode. In patients who experienced mild COVID-19 (n = 26), 2 patients (7.7%) were diagnosed with autoimmune thyroiditis, 8 patients (30.8%) presented thyroid nodules, and 4 patients (15.4%) had thyroid cysts. Serologic testing revealed elevated anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) in 10 patients (38.5%), thyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg) in 12 patients, and dual antibody positivity (anti-TPO + anti-Tg) in 4 patients. Among patients with moderate COVID-19 (n = 25), 6 patients (24%) developed autoimmune thyroiditis, 5 (20%) showed thyroid nodules, and 6 (24%) had thyroid cysts. Anti-TPO positivity was observed in 9 patients (36%), anti-Tg in 7 patients, and dual positivity in 5 patients. In the group with severe disease (n = 37), 6 patients (16.2%) had autoimmune thyroiditis, 6 (16.2%) thyroid nodules, and 13 patients (35.1%) thyroid cysts. Elevated anti-TPO levels were detected in 12 patients (32.4%), anti-Tg antibodies in 9 patients, and dual positivity in 3 cases. Among patients with a critical form of COVID-19 (n = 8), 2 patients (25%) developed autoimmune thyroiditis, and 1 patient (12.5%) presented thyroid nodules, with no thyroid cysts observed. Notably, this group showed the highest rate of anti-TPO positivity (5 patients, 62.5%). Anti-Tg antibodies were detected in 2 patients, and dual antibody positivity in 1 patient.

Overall, thyroid abnormalities, whether structural (nodules, cysts) or immunological (anti-TPO, anti-Tg positivity), were more frequent among patients with moderate and severe COVID-19. However, even patients who had experienced mild forms of the disease showed a notable degree of thyroid involvement, underscoring the persistent risk of endocrine dysregulation in the post-COVID period.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of thyroid involvement by initial COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of thyroid involvement by initial COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical Severity |

Autoimmune Thyroiditis n (%) |

Thyroid Nodules n (%) |

Thyroid Cysts n (%) |

Anti-TPO+ n (%) |

Anti-Tg+ n (%) |

Double Positivity (Anti-TPO + Anti-Tg) n (%) |

| Mild (n = 26) |

2 (7.7%) |

8 (30.8%) |

4 (15.4%) |

10 (38.5%) |

12 (46.2%) |

4 (15.4%) |

| Moderate (n = 25) |

6 (24.0%) |

5 (20.0%) |

6 (24.0%) |

9 (36.0%) |

7 (28.0%) |

5 (20.0%) |

| Severe (n = 37) |

6 (16.2%) |

6 (16.2%) |

13 (35.1%) |

12 (32.4%) |

9 (24.3%) |

3 (8.1%) |

| Critical (n = 8) |

2 (25.0%) |

1 (12.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (62.5%) |

2 (25.0%) |

1 (12.5%) |

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of thyroid alterations observed four years after primary SARS-CoV-2 infection, stratified by the clinical severity of the initial COVID-19 episode. A significant prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity markers (anti-TPO and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies) was observed across all severity categories, with a trend toward higher values among patients who had severe or critical disease.

Structural abnormalities—including thyroid nodules and cysts—were also frequent, particularly among patients with moderate and severe forms of COVID-19. The critical group showed the highest rate of anti-TPO positivity (over 60%), suggesting a potential link between the severity of the acute inflammatory response and long-term thyroid autoimmunity.

Importantly, the data indicate that post-COVID thyroid impairment, both structural and immunological, is not confined to severe cases, as alterations were also detected in patients with mild disease. This underscores the relevance of long-term endocrine follow-up after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

3.3. Identification of Risk Factors for Post-COVID Endocrine Sequelae

The roles of sex, age, comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia), and severity of the acute COVID-19 episode were assessed in relation to the risk of developing post-COVID type 2 diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroiditis. The risk factor analysis revealed a significant association between advanced age, hypertension, and severe/critical acute COVID-19 and the subsequent development of type 2 diabetes.

Among the 96 evaluated patients, 26 (27.1%) were diagnosed with newly onset diabetes mellitus. Patients who developed post-COVID diabetes were more frequently older (≥60 years: 61.5% vs. 38.6%, p = 0.04) and hypertensive (73.0% vs. 35.7%, p = 0.002). In addition, a significantly higher proportion of these patients had experienced severe or critical forms of COVID-19 during hospitalization (76.9% vs. 42.9%, p = 0.005). Female sex (p = 1.000) and obesity (p = 0.38) were not associated with post-COVID diabetes. Further statistical testing confirmed significant associations between diabetes onset and hypertension (p = 0.002768) as well as severe/critical COVID-19 (p = 0.005359). Age ≥60 years showed a trend toward significance but did not reach the threshold (p = 0.08888).

Autoimmune thyroiditis was identified in 37 patients (38.5%). Unlike the findings observed for diabetes, none of the evaluated variables were significantly associated with autoimmune thyroiditis: female sex (p = 0.35), age ≥60 years (p = 0.46), hypertension (p = 0.27), obesity (p = 1.000), or initial COVID-19 severity (p = 1.000). Individual statistical analyses confirmed the absence of significant associations (all p > 0.25).

Overall, patients aged ≥60 years, those with hypertension, and those who had severe or critical COVID-19 exhibited a significantly higher probability of developing type 2 diabetes four years after the acute infection. In contrast, autoimmune thyroiditis did not correlate with any of the studied demographic or clinical factors, although a tendency toward higher prevalence was observed among women and older patients. These results suggest that post-COVID metabolic and autoimmune processes may be driven by partially distinct mechanisms, with specific risk profiles for each endocrine outcome. While acute disease severity and metabolic comorbidities, particularly hypertension,appear to be key determinants of post-COVID glycemic dysregulation, the development of thyroid autoimmunity may be influenced by additional immunologic or genetic factors.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of risk factors associated with post-COVID Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of risk factors associated with post-COVID Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis.

| Factor evaluated |

Post-COVID Type 2 Diabetes (n = 26) |

No Diabetes (n = 70) |

Post-COVID Autoimmune Thyroiditis (n = 37) |

No Thyroid Involvement (n = 59) |

| Severe / Critical COVID-19 |

p = 0.005359 |

p = 0.1338 |

p = 1.000 |

p = 0.6397 |

| Hypertension (HTA) |

p = 0.002768 |

p = 0.05067 |

p = 0.2720 |

p = 0.2732 |

| Obesity |

p = 0.3870 |

p = 0.6860 |

p = 1.000 |

p = 1.000 |

| Female sex |

p = 1.000 |

p = 1.000 |

p = 0.3588 |

p = 0.4327 |

| Age ≥ 60 years |

p = 0.08888 |

p = 0.2282 |

p = 0.4622 |

p = 0.5296 |

3.4. Association Between Thyroid Dysfunction and Post-COVID Diabetes Mellitus

A bidirectional analysis was performed to explore the relationship between autoimmune thyroid involvement and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) after SARS-CoV-2 infection, in order to assess a potential shared pathogenic link between the two endocrine disorders. The findings revealed a high prevalence of post-COVID endocrine abnormalities, with a notable proportion of patients presenting either thyroid autoimmunity, post-COVID diabetes, or both conditions simultaneously.

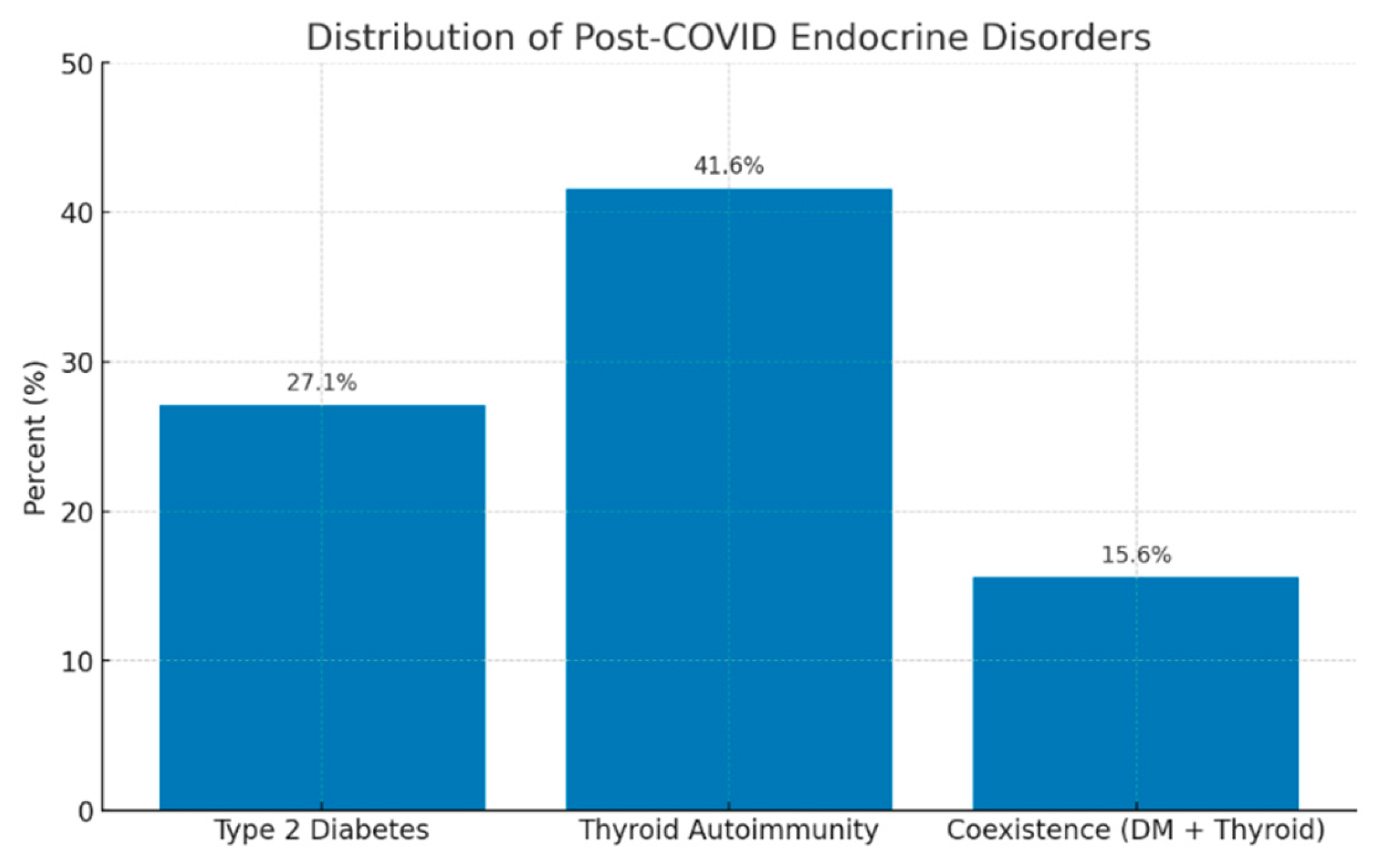

Overall, 41.6% of patients demonstrated evidence of thyroid autoimmunity (defined as positive anti-TPO and/or anti-Tg antibodies and/or ultrasound features consistent with autoimmune thyroiditis), while 27.0% were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus at the 4-year follow-up. Interestingly, 15.6% of the cohort exhibited coexistence of both conditions (diabetes + thyroid autoimmunity), suggesting a possible overlapping pathogenic pathway, potentially driven by post-viral immune dysregulation or persistent systemic inflammation.

In total, 47.9% of the patients developed at least one endocrine disorder, whereas 52.1% did not present any detectable endocrine sequelae.

These findings support the hypothesis of a possible interaction between post-COVID autoimmune thyroid dysfunction and type 2 diabetes, with both conditions likely sharing common immune-mediated mechanisms triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Overall, the findings highlight the need for integrated endocrine monitoring in patients with a history of COVID-19, particularly in those with positive thyroid autoantibodies or stress-induced hyperglycemia at admission.

Table 8.

Distribution of post-COVID endocrine outcomes in the study cohort.

Table 8.

Distribution of post-COVID endocrine outcomes in the study cohort.

| Endocrine outcome |

n (%) |

| No endocrine disorder |

50 (52.1%) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis only |

30 (31.2%) |

| Type 2 diabetes only |

10 (10.4%) |

| Both diabetes + thyroid autoimmunity |

15 (15.6%) |

Figure 4.

Legend: Distribution of post-COVID endocrine disorders. The bar chart illustrates the prevalence of the main endocrine alterations identified four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thyroid autoimmunity was the most frequent finding (41.6%), followed by type 2 diabetes mellitus (27.0%), while the coexistence of both conditions was observed in 15.6% of patients. These results indicate a high prevalence of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions and suggest potential shared pathogenic mechanisms, likely mediated by persistent systemic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

Figure 4.

Legend: Distribution of post-COVID endocrine disorders. The bar chart illustrates the prevalence of the main endocrine alterations identified four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thyroid autoimmunity was the most frequent finding (41.6%), followed by type 2 diabetes mellitus (27.0%), while the coexistence of both conditions was observed in 15.6% of patients. These results indicate a high prevalence of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions and suggest potential shared pathogenic mechanisms, likely mediated by persistent systemic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

3.5. Global Endocrine Impact at Four-Year Follow-Up

To assess the overall endocrine impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection, we examined the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine dysfunction, type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or autoimmune thyroiditis, at the four-year follow-up following the acute COVID-19 episode.

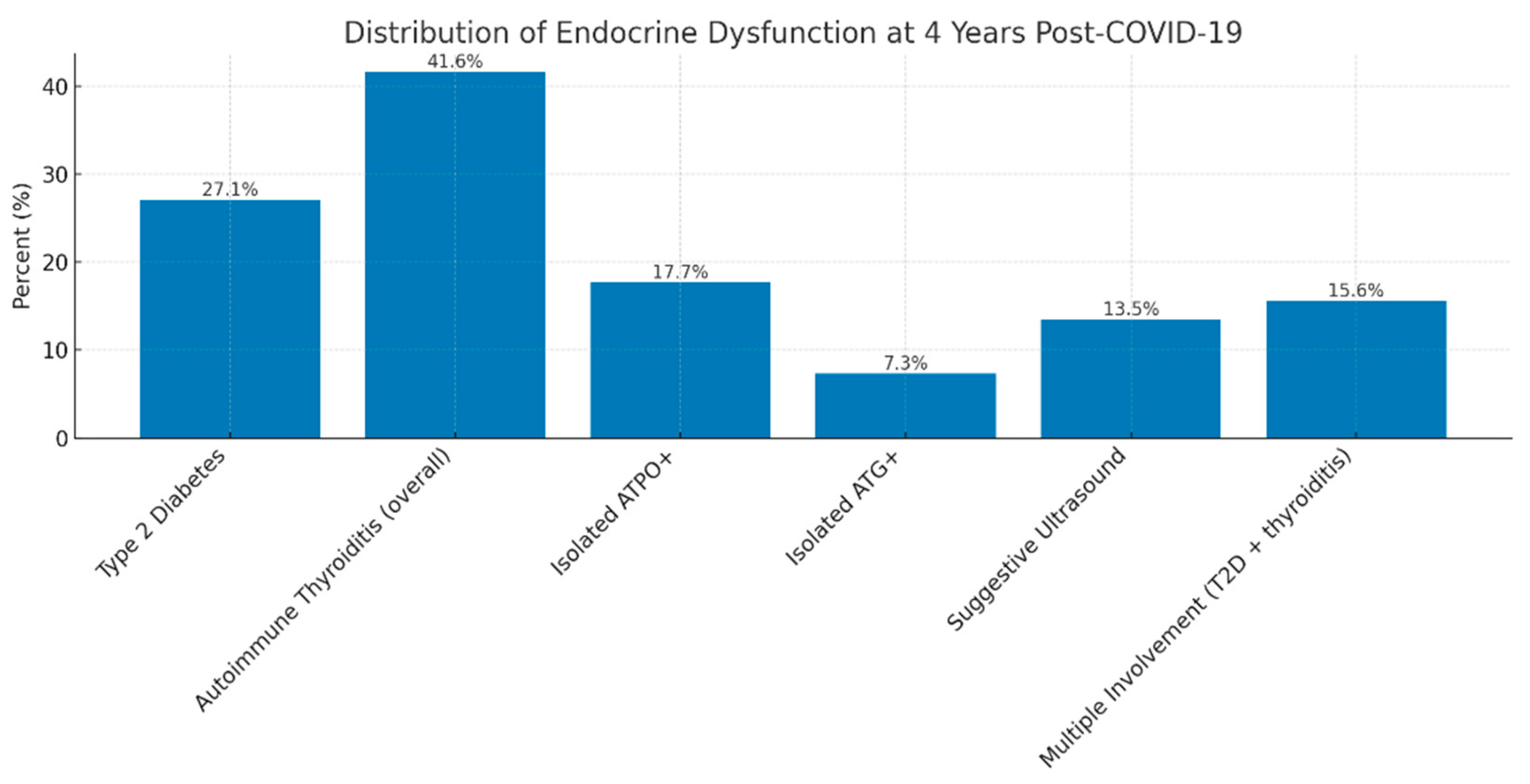

Among the 96 patients who completed reassessment, 46 (47.9%) presented a new-onset or persistent endocrine abnormality. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in 26 patients (27.1%). Serological and/or ultrasound markers of autoimmune thyroiditis were identified in 37 patients (38.5%), of whom 17 (17.7%) had isolated anti-TPO positivity, 7 (7.3%) had isolated anti-Tg positivity, and 13 (13.5%) showed ultrasound features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis (diffuse hypoechogenicity, parenchymal heterogeneity, increased vascularity). Thus, nearly half of the reassessed cohort exhibited at least one endocrine dysfunction four years after COVID-19, highlighting the substantial cumulative burden of long-term endocrine sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 5.

Legend: Distribution of endocrine dysfunctions four years after COVID-19. The bar chart displays the prevalence of different types of endocrine alterations identified at four-year follow-up. These findings underscore both the persistence and heterogeneity of long-term endocrine disturbances after COVID-19, supporting the hypothesis of shared mechanisms involving chronic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

Figure 5.

Legend: Distribution of endocrine dysfunctions four years after COVID-19. The bar chart displays the prevalence of different types of endocrine alterations identified at four-year follow-up. These findings underscore both the persistence and heterogeneity of long-term endocrine disturbances after COVID-19, supporting the hypothesis of shared mechanisms involving chronic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study support the concept that SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to persistent endocrine consequences, even several years after the acute episode. Although the respiratory impact of COVID-19 was initially the main focus, increasing evidence has demonstrated that the virus exerts complex systemic effects, involving multiple ACE2-expressing target organs, including the pancreas and thyroid gland [

7,

10]. These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 is not solely a respiratory pathogen, but also a disruptor of endocrine and metabolic homeostasis.

4.1. General Considerations on the Persistent Endocrine Implications of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The present study provides a detailed assessment of endocrine status in previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients, evaluated four years after the acute episode. This represents one of the longest post-COVID endocrine follow-up investigations reported to date, allowing characterization of long-term endocrine sequelae well beyond the 6–24 month interval explored in most published studies [

5,

6].

At the time of reassessment, 27% of patients without a prior history of diabetes met diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes mellitus. This proportion aligns with the increased risk of post-COVID diabetes documented in large population-based studies [

13,

26], but its persistence at four years post-infection suggests that metabolic disturbances may remain long after clinical recovery.

A particularly relevant finding is the association between acute-phase hyperglycemia and subsequent diabetes development. Among patients who presented with hyperglycemia at admission (70.8%), 22.1% developed diabetes by the 4-year follow-up, compared with only 7.4% of initially normoglycemic patients. These results support the hypothesis that COVID-19–related stress hyperglycemia reflects an underlying metabolic vulnerability, amplified by systemic inflammation and the host immune response to viral infection [

12,

16].

Thyroid analysis revealed a high prevalence of autoimmune markers in patients with no previous thyroid disease: 29.8% had elevated anti-TPO antibodies, 17.8% had anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (ATG), and 19% showed ultrasound features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis, including diffuse hypoechogenicity, parenchymal heterogeneity, or hypervascularization. These rates exceed those expected in the general population (≈10–15%) and are consistent with findings from Asian and European cohorts assessed 6–12 months post-COVID [

18,

21,

27].

The persistence of these abnormalities four years after infection suggests that thyroid autoimmunity may be a delayed or chronic process, even in the absence of overt symptoms. Notably, higher rates of ATPO positivity and structural thyroid changes were observed among patients who experienced moderate, severe, or critical COVID-19, reinforcing the link between systemic inflammatory burden and post-infectious thyroid autoimmunity [

20,

22].

Overall, the findings indicate that a substantial proportion of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients exhibit persistent or newly developed metabolic dysfunction, thyroid autoimmunity, and, in some cases, structural thyroid alterations detectable on ultrasound at four years post-infection. These observations support the concept that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a trigger for long-lasting endocrine disturbances, mediated by systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and possibly direct viral effects on endocrine tissues [

8,

9,

19].

The defining strength of this study lies in the unusually long interval between the initial COVID-19 infection and the time of evaluation, offering a rare perspective on the very long-term endocrine consequences of the disease. By jointly assessing thyroid function, autoimmune markers, and glucose metabolism, the study provides strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection can leave detectable endocrine footprints even four years after the acute episode. These findings support the need for periodic monitoring of endocrine function in patients with a history of COVID-19, particularly those who experienced severe disease or hyperglycemia during hospitalization [

6,

28]. Implementing late post-infection metabolic and thyroid screening protocols may enable early detection and appropriate management of delayed endocrine complications.

4.2. New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus as a Metabolic Sequela of COVID-19

In our cohort, 27% of patients without a prior history of diabetes mellitus (DM) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at the 4-year post-infection follow-up. This proportion exceeds the incidence reported within the first 6–24 months after infection, but aligns in trend with findings from large population-based analyses. Wander et al. observed a significant increase in diabetes incidence among more than 2.8 million U.S. veterans with a history of COVID-19, reporting a relative excess risk of 40–60% and an excess burden of 13–15 new cases per 1000 persons at 12 months, including those who were not hospitalized [

29]. Subsequently, Xie and Al-Aly confirmed, in extensive cohorts from the U.S. Veterans Affairs Health System, a persistent elevation in diabetes risk at 12–24 months post-infection, with a gradient proportional to the severity of the acute illness [

13,

26]. European studies, including analyses based on German health records, have also documented incidence rate ratios ranging from 1.2 to 1.6 for new-onset diabetes following COVID-19, compared to acute respiratory infections of non-COVID origin [

30].

Several potential mechanisms may explain the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-infectious diabetes mellitus. In the first place, direct viral injury to pancreatic β-cells appears to play a central role. SARS-CoV-2 can infect pancreatic islet cells through ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors, leading to cytopathic effects, impaired insulin secretion, and altered β-cell gene expression. These changes may reduce the functional β-cell reserve and accelerate the transition from prediabetes to overt diabetes [

8,

31,

32]. Then, another mechanism involves the systemic inflammatory response, or “cytokine storm”, characteristic of acute COVID-19, which can further disrupt glucose homeostasis. Elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α interfere with insulin signaling pathways, particularly the insulin receptor substrate/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (IRS/PI3K/AKT) pathway, leading to reduced glucose uptake and increased insulin resistance, promote lipolysis and hepatic gluconeogenesis, and decrease peripheral insulin sensitivity [

10,

33]. Persistent low-grade inflammation after recovery may maintain this dysglycemic state. Additionally, post-infectious insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction represent another pathway linking COVID-19 to chronic hyperglycemia. Endothelial injury, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial abnormalities induced by SARS-CoV-2 can aggravate hepatic and muscular insulin resistance, impair glucose utilization, and blunt compensatory β-cell responses [

9,

34,

35]. Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that COVID-19 may exert long-lasting metabolic effects extending well beyond the acute phase of infection.

4.3. Admission Hyperglycemia as a Predictor of Long-Term Diabetes

In our cohort, 71.9% of patients exhibited hyperglycemia at hospital admission, and 33.3% of these individuals developed type 2 diabetes at the 4-year follow-up. This finding supports the hypothesis that stress-induced hyperglycemia serves as a marker of pre-existing metabolic vulnerability that becomes "unmasked" in the context of acute inflammation [

12,

16]. The persistence of systemic inflammation, alongside subsequent behavioral and metabolic factors, may further drive the transition to overt diabetes mellitus.

Our findings are consistent with those of Zhu et al., who demonstrated that hospitalized COVID-19 patients with blood glucose levels >140 mg/dL at admission had more than twice the risk of developing subsequent diabetes compared to normoglycemic patients [

36]. This reinforces the premise that stress-induced hyperglycemia represents not only a marker of acute disease severity, but also a metabolic predictor of long-term dysglycemia post-COVID [

37].

Stress hyperglycemia likely arises from a combination of mechanisms described earlier, compounded by excessive activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which elevates cortisol secretion and promotes hyperglycemia [

8,

10,

33]. Over time, these pathways may exceed the compensatory capacity of pancreatic β-cells, precipitating type 2 diabetes even in individuals previously considered normoglycemic. Chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction additionally contribute to sustained insulin resistance and progressive dysregulation of glucose homeostasis [

34,

35].

These findings underscore the clinical relevance of admission hyperglycemia as an early warning indicator [

37]. Patients presenting with elevated blood glucose during acute COVID-19 infection should undergo long-term metabolic monitoring, even if normoglycemia is restored at discharge. Recommended follow-up assessments include HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, and lipid profile testing at 3–6 months post-discharge, and annually thereafter, to enable early detection of new-onset diabetes or prediabetes [

12]. Enhanced vigilance is particularly warranted in individuals with established cardiometabolic risk factors, such as older age, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or corticosteroid exposure during the acute illness. Implementing such strategies may facilitate timely lifestyle modifications and, where necessary, pharmacologic intervention to mitigate progression to overt diabetes mellitus.

4.4. COVID-19 and Thyroid Dysfunction: Long-Term Implications

The results of our study confirm that thyroid involvement represents one of the most frequent endocrine sequelae following COVID-19. Four years after the acute episode, nearly one-third of patients exhibited markers of thyroid autoimmunity, with 29.8% testing positive for anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies and 17.8% for anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) antibodies, while 19% showed ultrasonographic features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis. These rates are higher than those reported in the general European population (10–15%) and are comparable to findings from international post-COVID cohorts [

21,

27]. In an Italian study, Campi et al. reported a 15.7% prevalence of anti-TPO antibodies three months post-infection—approximately double that observed in a pre-pandemic control group (7.7%) [

27]. In a Hong Kong cohort, Lui et al. identified a 1.7% incidence at six months, particularly among patients treated with interferon beta-1b [

21]. Similar data have emerged from studies in China and Italy, where post-COVID thyroid autoimmunity prevalence ranged between 12% and 25% at 6–12 months of follow-up [

39,

40,

41]. By comparison, the higher values observed in our cohort may reflect persistent residual immune activation and a cumulative long-term inflammatory effect.

Several mechanisms may underlie the link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development of post-infectious autoimmune thyroiditis. One of the most plausible explanations involves the high expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors in the thyroid gland. Transcriptomic and immunohistochemical analyses have demonstrated dense ACE2 expression in thyroid follicular epithelial cells, comparable to that observed in the lung, intestine, and kidney [

42,

43]. This expression pattern renders the thyroid susceptible to direct viral entry, allowing SARS-CoV-2 to induce local cytopathic damage through viral replication and destruction of follicular cells. As a result, intracellular thyroid antigens—particularly thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO), are released into the extracellular environment, becoming targets for the immune system. This so-called

antigen spillage phenomenon may trigger secondary autoimmune responses, especially in genetically predisposed individuals carrying HLA-DR3 or HLA-DR5 haplotypes. Moreover, the local inflammatory process may upregulate adhesion and co-stimulatory molecules on follicular cells, effectively transforming them into non-professional antigen-presenting cells that perpetuate thyroid autoimmunity [

42,

43].

Direct infection–induced cytopathic injury is further amplified by the systemic inflammatory response characteristic of acute COVID-19, commonly referred to as the “cytokine storm.” Elevated circulating levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β can alter thyroid antigen expression and increase their immunogenicity. These cytokines also promote lymphocytic infiltration into thyroid tissue via chemokines such as CXCL10 and CCL2, while disrupting peripheral immune tolerance and activating autoreactive T and B lymphocytes [

44]. Persistent low-grade inflammation and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines months or even years after infection may sustain subclinical immune activation, gradually promoting the transition to chronic autoimmune thyroiditis of the Hashimoto type [

44,

45].

Another key mechanism is molecular mimicry, a well-established concept in post-viral autoimmunity. Structural similarities have been identified between specific regions of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins and thyroid autoantigens such as thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase [

46,

47]. This molecular homology may elicit cross-reactive immune responses, whereby lymphocytes and antibodies initially directed against viral epitopes begin to recognize and attack thyroid structures. The persistent immune stimulation during acute infection amplifies this process, potentially initiating or exacerbating autoimmune thyroiditis even after viral clearance [

45,

46].

Finally, SARS-CoV-2 infection may reactivate latent or subclinical thyroid autoimmunity in genetically predisposed individuals. Host genetic factors may further modulate the risk of post-COVID thyroid autoimmunity. Previous studies have identified HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR5 alleles as major susceptibility markers for autoimmune thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The interplay between viral-induced immune activation, molecular mimicry, and genetic predisposition could therefore explain the persistence of thyroid autoantibodies observed in our cohort [

45,

47]. In such cases, the intense systemic inflammatory response and immune activation during acute COVID-19 may destabilize immune homeostasis, leading to loss of self-tolerance [

44,

45,

48]. This mechanism is more frequently described in women, reflecting sex-specific immunological dimorphism and potentially accounting for the higher incidence of autoimmune thyroiditis observed in our cohort.

Most longitudinal studies indicate that thyroid dysfunctions emerging during the acute phase of COVID-19 are transient. Lui et al. (

Thyroid, 2023) observed that 82.4% of patients with acute thyroid abnormalities returned to normal within 3–6 months. However, a subset of patients develop persistent autoimmunity, characterized by sustained elevation of anti-TPO and/or anti-Tg antibody titers at successive follow-up evaluations, even in the absence of overt clinical hypothyroidism [

21,

40,

48]. Our findings, obtained four years after infection, confirm the existence of this subset: nearly 30% of patients exhibit serological or ultrasonographic markers of autoimmune thyroiditis, suggesting a late post-viral autoimmune phase with slow evolution.The persistence of thyroid autoantibodies, even in the absence of overt hormonal dysfunction, may have significant clinical implications, increasing the risk of progressive hypothyroidism, fatigue, and subtle metabolic disturbances [

49].

Recent reviews published in

Frontiers in Endocrinology (2023) have highlighted that patients with severe COVID-19 are at an increased risk of developing thyroid dysfunction, including non-thyroidal illness syndrome during the acute phase and autoimmune thyroiditis during long-term follow-up. The persistence of elevated thyroid autoantibody titers has been reported particularly among subgroups of patients with marked inflammatory responses [

50]. Given these findings, periodic monitoring of thyroid function is recommended for individuals with a history of COVID-19, especially those who experienced moderate or severe disease with elevated inflammatory markers during the acute phase [

21,

41]. Re-evaluation should be performed 12–24 months after infection, even in the absence of clinical symptoms, and should include measurement of TSH, FT4, and FT3, assessment of anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibodies, and thyroid ultrasonography to allow early detection of structural or functional abnormalities. Post-COVID thyroid involvement should be interpreted within the broader context of SARS-CoV-2–induced endocrine disturbances, which may also encompass new-onset diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, and hypothalamic–pituitary axis dysfunctions [

51]. These manifestations reflect the systemic impact of the virus on immune–endocrine homeostasis, underscoring the potential for chronic sequelae and the importance of long-term multidisciplinary follow-up [

6,

49,

51].

4.5. Endocrine Autoimmunity – A Potential Link in Post-COVID Syndrome (PASC)

Our study provides additional evidence supporting the hypothesis that endocrine autoimmunity may represent a key component of the complex spectrum of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). This syndrome is defined by the persistence or emergence of new symptoms more than 12 weeks after the acute infection, in the absence of alternative explanations, and encompasses a wide range of systemic manifestations, including chronic fatigue, cognitive impairment (“brain fog”), respiratory dysfunction, cardiovascular involvement, and metabolic disturbances [

52,

53].

In this context, the thyroid and metabolic dysfunctions observed four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection may be interpreted not merely as isolated sequelae, but as endocrine expressions of long COVID syndrome. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–peripheral axes, residual inflammation, and persistent autoimmunity may account for part of the nonspecific symptomatology observed in these patients, particularly fatigue, reduced physical performance, and mild cognitive disturbances [

54,

55].

Thyroid autoimmunity, identified in nearly one-third of re-evaluated patients, may play a central role in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying PASC. Even in the absence of overt hypothyroidism, the presence of anti-TPO and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies may be associated with subclinical thyroid dysfunction, potentially impacting energy metabolism, thermoregulation, and neuromuscular function [

56]. Studies have shown that patients with early-stage autoimmune thyroiditis can experience symptoms such as chronic fatigue, concentration difficulties, and mood disturbances, features that closely resemble those described in long COVID [

56,

57].

Post-COVID metabolic alterations, including new-onset diabetes and persistent insulin resistance, may amplify systemic inflammation and contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced exercise capacity [

12,

58]. Chronic hyperglycemia activates proinflammatory pathways (NF-κB, IL-6, TNF-α) and induces oxidative stress, sustaining a state of low-grade inflammation characteristic of PASC [

59]. This supports an integrated pathogenic model in which acute SARS-CoV-2 infection acts as a trigger for endocrine autoimmunity and dysfunction, while residual inflammation and metabolic disturbances contribute to symptom persistence [

45]. Furthermore, potential correlations can be drawn between endocrine autoimmunity and persistent symptomatology. Chronic fatigue may reflect subclinical hypothyroidism or subtle alterations in energy metabolism, whereas cognitive disturbances (“brain fog”) may be associated with impaired neurotransmission and cerebral glucose metabolism. Exercise intolerance and muscle weakness could be exacerbated by insulin resistance and altered thyroid hormone activity, while autonomic symptoms (tachycardia, anxiety, heat intolerance) may arise from combined neuroendocrine and autoimmune dysregulation [

56,

58,

59]. Lui et al. (2021) reported that patients with post-COVID thyroid dysfunction more frequently experience fatigue and concentration difficulties, even in the absence of persistent abnormalities in TSH or FT4 levels [

56]. Similarly, recent metabolic studies have confirmed the role of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance in sustaining post-COVID symptoms [

58,

59].

Patients presenting with persistent fatigue, exercise intolerance, or cognitive disturbances should be evaluated for subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity, while post-infectious glycemic monitoring may help prevent delayed diagnosis of post-COVID diabetes mellitus. Implementing a multidisciplinary follow-up protocol involving infectious disease specialists, endocrinologists, and rehabilitation experts could significantly improve functional outcomes and quality of life in these patients [

60]. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of recognizing endocrine autoimmunity as a potential driver of long-term systemic symptoms in post-COVID syndrome and underscore the need for integrated clinical management strategies.

4.6. Interaction Between Metabolic and Thyroid Axes and Risk Factors for Post-COVID Endocrine Sequelae

There is a close interrelationship between thyroid function and glucose metabolism, both systems being regulated through interconnected hormonal mechanisms. Thyroid hormones influence insulin sensitivity, hepatic glucose production, and basal metabolic rate, whereas insulin and metabolic status modulate the peripheral conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) [

60,

61]. Hypothyroidism, even in its subclinical form, leads to reduced insulin clearance, decreased expression of glucose transporters (GLUT-4), and increased insulin resistance at both muscular and hepatic levels [

62]. Conversely, hyperthyroidism enhances hepatic gluconeogenesis and protein catabolism, thereby promoting hyperglycemia [

59]. These bidirectional alterations explain the high prevalence of glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus among patients with thyroid dysfunction [

59,

61]. In the post-COVID context, where autoimmune thyroid involvement and persistent insulin resistance may coexist, a vicious endocrine–metabolic cycle can develop. Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress induce both thyroid autoimmunity and impaired insulin sensitivity; in turn, chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance sustain low-grade inflammation, perpetuating thyroid injury [

58,

59].

In our cohort, a partial overlap was observed between patients with thyroid autoimmunity and those diagnosed with post-COVID diabetes, suggesting the presence of shared pathogenic mechanisms. This association aligns with evidence from previous studies showing that persistent systemic inflammation, a hallmark of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, can sustain both thyroid autoimmunity and metabolic dysregulation through overlapping immune–endocrine pathways [

51]. Furthermore, recent comprehensive reviews have highlighted that COVID-19–related thyroid disorders often coexist with insulin resistance and other components of metabolic dysfunction, supporting a bidirectional link between autoimmune and metabolic sequelae [

55].

Risk factor analysis in our cohort indicates that the occurrence of post-COVID endocrine sequelae, both new-onset diabetes mellitus and thyroid autoimmunity, is not a random phenomenon but rather reflects the interplay between individual predisposition and the severity of systemic inflammation during the acute phase of infection. Female sex was associated with a higher prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity, confirming the increased immunological susceptibility of women to autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [

56].

Likewise, older patients (≥60 years) more frequently exhibited diabetes and thyroid dysfunction, which can be explained by immunosenescence, decreased β-cell reserve, and preexisting metabolic comorbidities [

6]. The severity of acute COVID-19 emerged as the strongest predictor of long-term endocrine disturbances, consistent with previous recommendations emphasizing the need for endocrine follow-up in patients with severe disease [

6]. Our results align with the findings of Xie and Al-Aly, who demonstrated a progressive increase in the risk of incident diabetes proportional to the severity of the initial infection [

13]. Regarding thyroid involvement, Campi et al. and Lui et al. described a similar association between the intensity of the acute inflammatory response (“cytokine storm”) and persistently elevated anti-TPO titers at 6–12 months after infection [

21,

55]. Moreover, obesity and dyslipidemia were correlated with an increased risk of post-COVID diabetes, reinforcing their role as preexisting metabolic vulnerability factors. These comorbidities amplify the inflammatory response and insulin resistance, creating a favorable background for chronic glycemic disturbances following severe infectious stress [

10,

58].

Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that severe forms of COVID-19, intense systemic inflammation, and adverse metabolic profiles act synergistically to determine long-term endocrine risk. Identifying these determinants enables the definition of a post-COVID endocrine risk profile, useful for guiding targeted screening strategies and implementing individualized endocrine follow-up protocols for high-risk patients [

62].

4.7. The Significance of the Cumulative Endocrine Burden After COVID-19

The high proportion of patients exhibiting endocrine dysfunctions four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection reflects the systemic and long-lasting impact of COVID-19 on metabolic and immune homeostasis. The finding that nearly one in two individuals presented with an endocrine abnormality, either metabolic or autoimmune, suggests that post-COVID syndrome displays a multisystemic behavior with a marked endocrine tropism. These results are consistent with international observations reporting an increased prevalence of new-onset diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection [

26,

27]. Prospective studies have shown that systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis can disrupt metabolic and immune regulation, triggering persistent autoimmune processes [

14,

53]. The concomitant presence of diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity in approximately 18% of patients supports the hypothesis of a post-COVID immunometabolic phenotype characterized by interrelated endocrine disturbances mediated through shared inflammatory mechanisms. This profile may resemble virus-induced polyautoimmune syndromes described after other infections (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus), but with broader clinical expression due to the multisystemic tropism of SARS-CoV-2 [

45,

63].

From a clinical standpoint, these findings justify the inclusion of systematic endocrine evaluations in post-COVID follow-up protocols, not only to monitor isolated disturbances (such as thyroid or glucose abnormalities), but also to quantify the overall endocrine impact of infection. An integrated surveillance algorithm including fasting glucose, HbA1c, TSH, FT4, and anti-TPO/anti-Tg antibody testing could contribute to the early identification of such abnormalities and to reducing the long-term metabolic and functional burden.

4.8. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the relatively small sample size of patients re-evaluated (96 out of 1009 initially hospitalized individuals) may limit the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Although the participation rate (≈9%) is comparable to that of other long-term post-pandemic cohorts, a potential selection bias cannot be excluded. Individuals who agreed to participate in follow-up may have been more health-conscious or symptomatic, which could have resulted in an overestimation of the true prevalence of post-COVID endocrine abnormalities. Second, the monocentric nature of the study limits the external validity of the results, as demographic, genetic, and therapeutic differences across regions could influence outcomes. The absence of a control group composed of individuals without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection precludes direct comparison of the prevalence of new-onset diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity with that in the general population. Nevertheless, indirect comparisons with published international data offer a valuable interpretive framework and reinforce the plausibility of the observed associations. Another limitation is the single follow-up point at four years post-infection, without intermediate assessments (e.g., at 6, 12, or 24 months). It remains uncertain whether the abnormalities detected represent early post-infectious changes that persisted over time or late-onset phenomena arising from chronic inflammatory and autoimmune processes. Additionally, the potential confounding effect of corticosteroid therapy used during severe forms of COVID-19 must be acknowledged. Glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, may induce transient hyperglycemia, exacerbate insulin resistance, and accelerate the progression from prediabetes to overt diabetes in susceptible individuals. Given the lack of detailed data on cumulative dose and duration, the potential confounding effect of corticosteroid exposure on the observed association between COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus cannot be entirely excluded [

36].

Furthermore, post-pandemic behavioral changes may represent additional risk factors for metabolic disturbances. Reduced physical activity, weight gain, sleep disruption, unhealthy dietary patterns, and chronic psychological stress may independently contribute to the development of insulin resistance and endocrine dysfunctions [

65].

Despite these limitations, the present study provides a distinctive long-term perspective on endocrine sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection, representing one of the longest follow-up periods reported to date. By integrating serological and ultrasonographic assessments of both metabolic and thyroid axes, this work contributes valuable evidence regarding the sustained impact of COVID-19 on endocrine homeostasis and highlights the need for continued multidisciplinary follow-up in affected individuals.

4.9. Future Directions

The results of this study outline several priority areas for future research. To precisely define the temporal trajectory of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions, prospective studies with periodic assessments of glucose metabolism, thyroid function, and other endocrine axes (adrenal, gonadal) are needed. Expanding research to a multicenter level would allow for more representative findings and enable comparisons across regional, genetic, and therapeutic differences. The implementation of dedicated clinical registries would facilitate the systematic collection of data regarding the prevalence, types, and progression of endocrine disorders, support international comparisons, and inform public health policies aimed at the long-term monitoring of COVID-19 survivors. Based on the current observations, inclusion of fasting glucose, HbA1c, TSH, FT4, and anti-thyroid antibody testing in the standard follow-up protocol for post-COVID patients is warranted. A multidisciplinary approach involving specialists in infectious diseases, endocrinology, immunology, and rehabilitation could optimize early diagnosis and functional recovery in these patients.

5. Conclusions

Four years after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, our findings demonstrate that COVID-19 may have long-lasting endocrine consequences, even in individuals without prior endocrine disease. The high prevalence of newly diagnosed diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity supports the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 acts as a long-term trigger of immunometabolic dysregulation rather than a purely respiratory pathogen.

Disease severity and acute-phase hyperglycemia were strong predictors of subsequent diabetes, while nearly one-third of patients exhibited persistent thyroid autoimmunity, suggesting a chronic or delayed autoimmune process driven by residual inflammation.

These results emphasize the need for structured long-term endocrine follow-up of COVID-19 survivors, particularly those with moderate or severe disease. Periodic evaluation of glucose and thyroid function may enable early detection and management of post-infectious endocrine sequelae, highlighting that long COVID represents a systemic condition with enduring metabolic and autoimmune implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R. and V.B.; methodology, L.R.; software, V.M.; validation, L.R., M.E.C. and V.B.; formal analysis, L.R.; investigation, L.R. and L.G.C; resources, L.R. and L.G.C; data curation, L.R and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.; writing—review and editing, L.R and V.B..; visualization, L.R. , V.M and M.E.C.; supervision, V.B.; project administration, L.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital of Pneumophthisiology and Infectious Diseases in Brașov (approval no. 9328/June 20, 2024) and by the Ethics Committee of the “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu (approval no. 16/November 25, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their clinical and biochemical re-evaluation.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACE2 |

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 |

| ATG |

Anti-Thyroglobulin Antibodies |

| ATPO |

Anti-Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies |

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| FT3 |

Free Triiodothyronine |

| FT4 |

Free Thyroxine |

| HbA1c |

Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis |

| IFN |

Interferon |

| IL 6 |

Interleukin 6 |

| IR |

Insulin Resistance |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NTIS |

Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome |

| PASC |

Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 |

| RAAS |

Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| Tg |

Thyroglobulin |

| TMPRSS2 |

Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TPO |

Thyroid Peroxidase |

| TSH |

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

References

- Hiscott J, Alexandridi M, Muscolini M, Tassone E, Palermo E, Soultsioti M, Zevini A. The global impact of the coronavirus pandemic. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Pollard CA, Morran MP, Nestor-Kalinoski AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a global health crisis. Physiol Genomics. 2020;52(11):549–557. [CrossRef]

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(4):e102–7. [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiński Ł, Chylińska M, Banecka-Majkutewicz Z. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on the endocrine system. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1214143. [CrossRef]

- Pal R, Joshi A, Bhadada S.K., Banerjee M., Vaikkakara S., Mukhopadhyay S. Endocrine follow-up during post-acute COVID-19: Practical recommendations based on available clinical evidence. Endocrine Practice. 2022 Apr;28(4):425–432. [CrossRef]

- Bindom S.M., Lazartigues E. The sweeter side of ACE2: Physiological evidence for a role in diabetes. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2009 Apr;302(2):193–202. [CrossRef]

- Wu CT, Lidsky PV, Xiao Y, Lee IT, Cheng R, Nakayama T, Jiang S, Demeter J, Bevacqua RJ, Chang CA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects human pancreatic β cells and elicits β cell death: Implications for new-onset diabetes. Cell Metab. 2021;33(11):2100–2115.e10. [CrossRef]

- Georgieva E, Ivanov I, Angelov A, Tsvetkova D, Vasileva E, Ilieva Y, Kiselova-Kaneva Y, Traykov T, Yanev S, Vladimirova-Kitova L, et al. COVID-19 complications: oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial and endothelial dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(19):14876. [CrossRef]

- Drucker DJ. Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(3):457–70. [CrossRef]

- Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Jul;14(4):395–403. [CrossRef]

- Montefusco L., Ben Nasr M., D’Addio F., Loretelli C., Rossi A., Pastore I., Plebani L., Zuccotti G.S., Fiorina P. Acute and long-term disruption of glycometabolic control after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Metab. 2021 Jun;3(6):774–785. [CrossRef]

- Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: a cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2022 May;10(5):311–321. [CrossRef]

- Chourasia P, Goyal L, Kansal D, Roy S, Singh R, Mahata I, Das S, Singh A, Kumar P, Tiwari P. Risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus as a post-COVID-19 condition and possible mechanisms: A scoping review. J Clin Med. 2023 Feb 1;12(3):1159. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Wang Q, Tong Y, Hao J, Huang Y, Xiong Z, Zhang W, Zhang X, Liu J, Chen J. The impact of COVID-19 on incidence and clinical outcomes of new-onset diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28114. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Huang J, Zhu G, Liu Y, Xiao H, Zhou Q, Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Li Y, Zhao Y. Elevation of blood glucose level predicts worse outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001476. [CrossRef]

- Scappaticcio L, Pitoia F, Esposito K, Piccardo A, Trimboli P. Impact of COVID-19 on the thyroid gland: an update. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(4):803–815. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Kim SY, Kim TH, Kim HK, Lee J, Lee S, Park S, Choi J, Kim JH, Shin DY. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19: a systematic review. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2021;36(5):904–911. [CrossRef]

- Anbardar N, Sadeghi E, Fatemi A. Thyroid disorders and COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1535169. [CrossRef]

- Panesar A, Singh S, Patel R, Kaur P, Shah M, Reddy R, Gupta N, Mehta A, Khan S, Gill H. Thyroid function during and after COVID-19 infection. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1477389. [CrossRef]

- Lui DTW, Lee CH, Chow WS, Lee ACH, Tam AR, Fong CHY, Law CY, Leung EKH, To KKW, Tan KCB. Thyroid dysfunction in relation to immune profile, disease status, and outcome in 191 patients with COVID-19. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):e926–e935. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri R.M., Campennì A., Deandreis D., Siracusa M., Tozzoli R., Petranović Ovčariček P., Trimarchi F., Giovanella L., Lania A., Martino E. SARS-CoV-2-related immune-inflammatory thyroid disorders: facts and perspectives. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17(8):737–759. [CrossRef]

- Szczerbiński Ł, Chylińska M, Banecka-Majkutewicz Z. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on the endocrine system. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1214143.

- Romanian Ministry of Health. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Treatment Protocol—January 2022. Available online:https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/250463 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Romanian Ministry of Health. Treatment Protocol for Infection with SARS-CoV-2—June 2023. Available online:https://lege5.ro/gratuit/geztonzzgq3ts/protocolul-de-tratament-al-infectiei-cu-virusul-sars-cov-2-din-22062023 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature Med. 2021;27:601–615. [CrossRef]

- Campi I, Bulgarelli I, Dubini A, Perego GB, Tortorici E, Torlasco C, Torresani E, Rocco R, Magni D, Galliani I. Thyroid autoimmunity after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(9):e3841–e3850. [CrossRef]

- Puig-Domingo M, Marazuela M, Giustina A. COVID-19 and endocrine diseases. A statement from the European Society of Endocrinology. Endocrine. 2020;68(1):2–5. [CrossRef]

- Wander PL, Lowy E, Beste LA, Tulloch-Palomino L, Korpak A, Peterson AC, Boyko EJ. The incidence of diabetes among 2,808,106 veterans with COVID-19. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(4):782–789. [CrossRef]

- Rathmann W, Kuss O, Kostev K. Incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes after COVID-19. Diabetologia. 2022;65(6):949–954. [CrossRef]

- Tang X, Uhlén P, Zhang W, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the pancreas promotes pancreatic inflammation and β cell apoptosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1102448. [CrossRef]

- Steenblock C, Todorov V, Kanczkowski W, Eisenhofer G, Schedl A, Wong ML, Licinio J, Bauer M, Young AH, Gainetdinov RR. Post-COVID-19 diabetes: mechanisms, manifestations, and implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(10):597–607. [CrossRef]

- Lim S, Bae JH, Kwon HS, Nauck MA. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: from pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2021;17(1):11–30. [CrossRef]

- Ceriello A, Stoian AP, Rizzo M. COVID-19 and diabetes: What is the link? Metabolism. 2020 Sep;108:154256. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Elekhnawy E, Mostafa-Hedeab G, Negm WA, Qusty N, Batiha GE, De Waard M, Saad HM, Albogami SM. COVID-19 and insulin resistance: a narrative review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1139974. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X, Qin JJ, Zhang XJ, Cai J, Li H. Association of Blood Glucose Control and Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19 and Pre-existing Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metabolism. 2020 Jun;31(6):1068–1077.e3. [CrossRef]

- Rodina L, Monescu V, Caplan LG, Cocuz ME, Bîrluțiu V. Admission hyperglycemia as an early predictor of severity and poor prognosis in COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized adults. J Clin Med. 2025;14(20):7289. [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani D, Khunti K, Nafilyan V, Maddox T, Humberstone B, Diamond I, Banerjee A. Post-COVID syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021 Mar 31;372:n693. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Zhou W, Xu W. Thyroid Function Analysis in 50 Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Study. Thyroid. 2021 Jan 1;31(1):8–11. [CrossRef]

- Muller I, Cannavaro D, Dazzi D, Covelli D, Mantovani G, Muscatello A, Ferri E, Iacobello C, Sarti L, Rotondi M, Mirani M, Persani L, Fugazzola L. SARS-CoV-2-related atypical thyroiditis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Sep;8(9):739–741. [CrossRef]

- Lisco G, De Tullio A, Jirillo E, Giagulli V.A, De Pergola G, Guastamacchia E, Triggiani V. Thyroid and COVID-19: A Review on Pathophysiological, Clinical and Organizational Aspects. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021 Sep;44(9):1801–1814. [CrossRef]

- Rotondi M, Coperchini F, Ricci G, Denegri M, Croce L, Ngnitejeu S.T, Villani L, Magri F, Latrofa F, Chiovato L. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE-2 mRNA in thyroid cells: A clue for COVID-19-related subacute thyroiditis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021 May;44(5):1085–1090. [CrossRef]

- Lazartigues E, Qadir M.M.F, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Endocrine Significance of SARS-CoV-2’s Reliance on ACE2. Endocrinology. 2020 Sep 1;161(9):bqaa108. [CrossRef]

- Croce L, Gangemi D, Ancona G, Liboà F, Bendotti G, Minelli L, Chiovato L, Giavoli C. The cytokine storm and thyroid hormone changes in COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021 May;44(5):891–904. [CrossRef]

- Brancatella A, Viola N, Santini F, Latrofa F. COVID-induced thyroid autoimmunity. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023 Mar;37(2):101742. [CrossRef]

- Vojdani A, Kharrazian D. Potential antigenic cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissue with a possible link to an increase in autoimmune diseases. Clin. Immunol. 2020 Aug;217:108480. [CrossRef]

- Benvenga S, Guarneri F. Molecular mimicry and autoimmune thyroid disease. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2016 Dec;17(4):485–498. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri R.M, Campennì A, Siracusa M, Frazzetto G, Gullo D. Subacute thyroiditis in a patient infected with SARS-CoV-2: An endocrine complication linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hormones (Athens). 2021 Mar;20(1):219–221. [CrossRef]

- Mateu-Salat M, Urgell E, Chico A. SARS-CoV-2 as a trigger for autoimmune disease: Report of two cases of Graves’ disease after COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020 Oct;43(10):1527–1528. [CrossRef]

- Rossini A, Cassibba S, Perticone F, Benatti S.V., Venturelli S, Carioli G, Ghirardi A, Rizzi M, Barbui T, Trevisan R, Ippolito S. Increased prevalence of autoimmune thyroid disease after COVID-19: A single-center, prospective study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 8;14:1126683. [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan M.V., McGroder C, Stevens J.S., Cook J.R., Nordvig A.S., Shalev D, Sehrawat T.S., et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021 Apr;27(4):601–615. [CrossRef]

- Davis H.E., Assaf G.S., McCorkell L., Wei H., Low R.J., Re’em Y., Redfield S., Austin J.P., Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine. 2021 Aug;38:101019. [CrossRef]