1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), represents one of the most significant global public health challenges of recent decades. Since its emergence in December 2019, the infection has spread worldwide, resulting in hundreds of millions of cases and substantial mortality. On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern due to its rapid transmission and the profound strain placed on healthcare systems [

1,

2].

Although the acute phase of the pandemic has abated following widespread natural infection and vaccination, increasing evidence indicates that many individuals experience persistent or newly emerging manifestations beyond the acute illness, collectively termed post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) or long COVID [

3,

4]. These manifestations include fatigue, cognitive impairment, respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms, and a range of metabolic and endocrine disturbances, reflecting the multisystemic impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection [

4,

5,

6]. The endocrine system appears particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2-related injury, and these long-term effects may significantly affect quality of life, healthcare utilization, and productivity [

5,

6]. SARS-CoV-2 exerts systemic effects beyond the respiratory tract, largely through its use of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is highly expressed in pancreatic β-cells and thyroid follicular cells [

7]. Mechanisms proposed for endocrine involvement include direct cytopathic injury, cytokine-driven inflammation, oxidative stress, and longer-term immune dysregulation [

8,

9].

The interaction between COVID-19 and glucose metabolism is particularly complex and bidirectional. Individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM) are at increased risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes [

10,

11], while accumulating evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 infection may precipitate newly diagnosed diabetes or destabilize pre-existing disease [

12,

13]. Meta-analyses report a 40–65% increased risk of incident diabetes following COVID-19, affecting both type 1 and type 2 phenotypes [

14,

15]. Poor glycemic control during acute infection is also associated with higher rates of complications such as septic shock, acute kidney injury, and cardiovascular events [

16]. Recent large-cohort studies also confirm prolonged post-COVID metabolic instability and an elevated long-term risk of dysglycemia.

Thyroid dysfunction has likewise been widely reported among COVID-19 survivors. The high expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in the thyroid supports its susceptibility to viral injury [

6], while exaggerated immune activation may result in subacute thyroiditis, transient thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, or autoimmune thyroid disease such as Hashimoto thyroiditis or, less frequently, Graves’s disease [

17,

18]. Importantly, transient inflammatory thyroiditis must be distinguished from persistent autoimmune thyroid disease, which reflects long-term immune activation rather than temporary inflammatory changes. Recent evidence indicates that a subset of patients develops persistent thyroid autoimmunity, potentially through molecular mimicry involving thyroid antigens such as TPO and Tg [

19,

20]. While SARS-CoV-2 infection is increasingly recognized as a potential trigger for endocrine autoimmunity [

21,

22], major gaps remain. Most studies have follow-up durations of only 6–24 months, and very few extend beyond three years [

21,

22,

23].

A 4-year post-infection reassessment is particularly valuable, as it extends well beyond the expected resolution of viral thyroiditis and stress-induced metabolic disturbances. This longer interval allows the identification of delayed autoimmune manifestations and late-emerging endocrine dysfunctions that shorter observation windows may fail to capture. Based on these considerations, the present study reassessed a cohort of adults hospitalized for COVID-19 in 2020–2021 to evaluate metabolic and thyroid status four years after the initial infection. The primary objective of this study was to determine the 4-year prevalence of post-COVID endocrine sequelae, specifically: (i) incident type 2 diabetes and (ii) thyroid autoimmunity in adults previously free of endocrine disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study was designed as a retrospective observational cohort study conducted at a single centre, the Clinical Hospital of Pneumophthisiology and Infectious Diseases in Brasov, Romania. The study population was selected from the hospital's electronic database and included adult patients (≥18 years) hospitalized with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR or antigen testing between August 1, 2020, and July 31, 2021. Out of all hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during this period, 1009 adult patients without a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disorders were selected.

Initially, the inclusion criteria for the post-COVID follow-up phase targeted only those patients who had experienced severe or critical forms of the disease, based on the hypothesis that they would be at higher risk for endocrine sequelae. Subsequently, due to low participation, the eligibility criteria were broadened to include all patients from the initial cohort, regardless of acute disease severity. This necessary mid-study adjustment may have introduced selection bias, and this limitation is acknowledged.

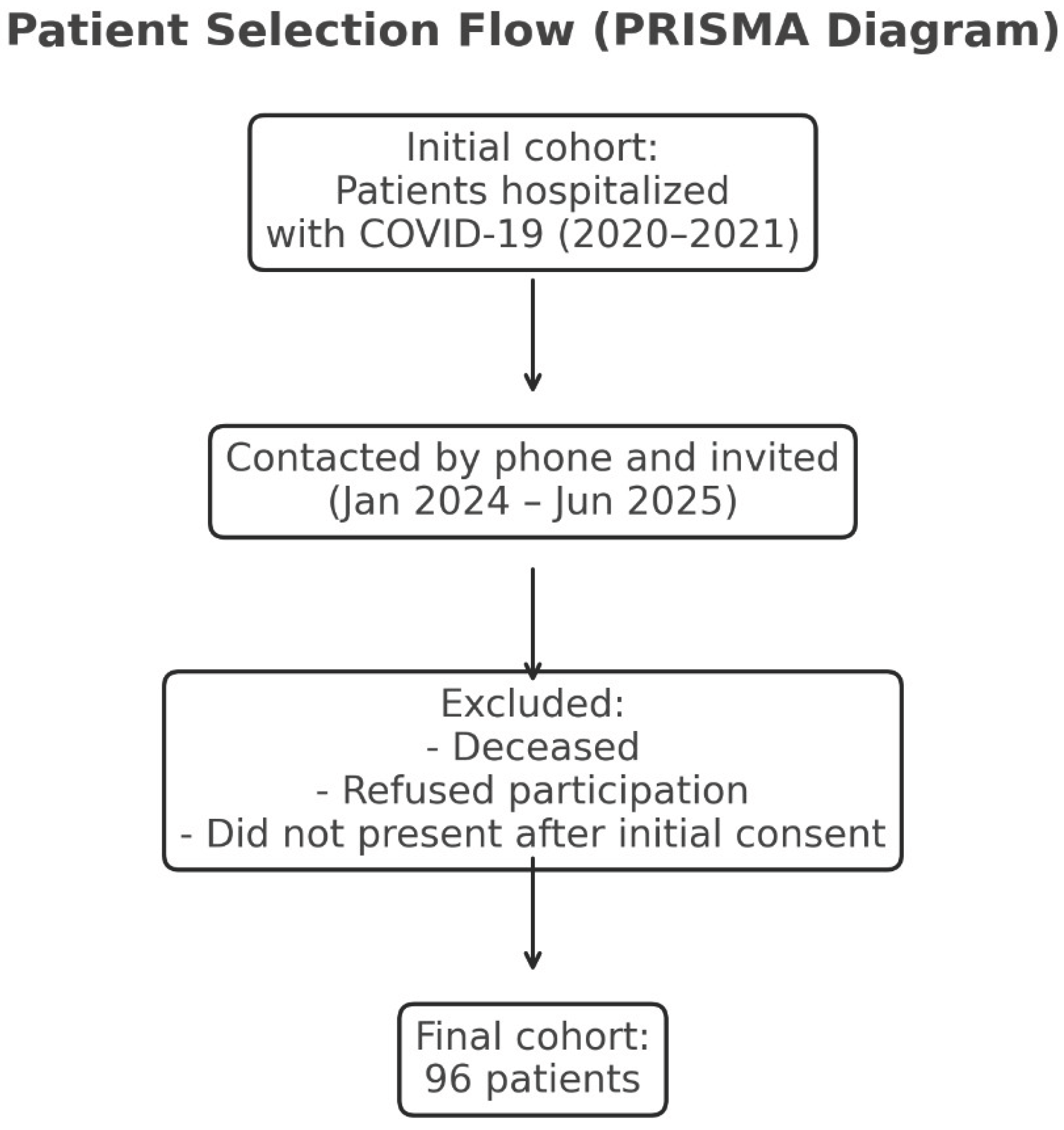

Between January 2024 and June 2025, eligible patients were contacted by phone and invited to participate in a clinical and paraclinical reassessment at the same hospital. Of the 1009 eligible patients, 96 formed the final study group. The low number of participants completing reassessment (96 of 1009) resulted from non-random loss to follow-up, including mortality, inability to contact patients, and reluctance to return for in-person evaluation ( figure 1). Such non-random attrition may affect cohort representativeness and is addressed as a study limitation.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Hospital of Pneumophthisiology and Infectious Diseases in Brasov (approval no. 9328/June 20, 2024) and by the Ethics Committee of the “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu (approval no. 16/November 25, 2022). COVID-19 diagnosis was based on clinical presentation and confirmed by laboratory testing.

Figure 1.

Legend: PRISMA-style flowchart showing patient recruitment and inclusion process. The final cohort consisted of 96 eligible participants after exclusion of deceased patients, non-responders, and those who did not attend follow-up evaluation.

Figure 1.

Legend: PRISMA-style flowchart showing patient recruitment and inclusion process. The final cohort consisted of 96 eligible participants after exclusion of deceased patients, non-responders, and those who did not attend follow-up evaluation.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data preprocessing was performed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365), followed by statistical analysis in Python 3.11 using pandas 2.2, NumPy 1.26, SciPy 1.11, and statsmodels 0.14. Group comparisons between categorical variables were conducted using Pearson’s chi-square test. Given the limited sample size of the follow-up cohort and the small number of outcome events, multivariable logistic regression models could not be reliably implemented without generating unstable or overfitted estimates. Therefore, all inferential results should be interpreted as unadjusted and exploratory. For analyses involving multiple hypotheses, p-values were corrected using the Benja-mini–Hochberg false discovery rate procedure, with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. Plots were created using Matplotlib 3.8 and Seaborn 0.13, and Excel was used in parallel for tabulation and cross-checking

2.3. Aim and Objectives

The primary aim of the study was to determine the prevalence of long-term endocrine sequelae, specifically incident type 2 diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity, four years after COVID-19. Secondary aims included examining (i) the association between acute COVID-19 severity and long-term endocrine outcomes, (ii) the predictive value of admission hyperglycemia for later T2D, and (iii) demographic and clinical factors linked to endocrine sequelae. The underlying hypothesis was that patients hospitalized for COVID-19, even in the absence of prior endocrine disease, might experience delayed disturbances in glucose metabolism and thyroid autoimmunity, potentially leading to persistent clinical consequences and an impact on overall health status.

In addition to quantifying the burden of long-term endocrine complications, the study sought to investigate several key aspects of this association. First, we examined whether the severity of the acute COVID-19 episode influences the subsequent risk of developing diabetes or thyroid autoimmunity. We additionally assessed whether stress-induced hyperglycaemia during hospitalization could predict the later onset of type 2 diabetes. Moreover, the role of demographic and clinical factors, including age, sex, and comorbidities such as hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidaemia, was explored in relation to endocrine outcomes. Given possible shared pathogenic pathways, we also evaluated the interplay between thyroid dysfunction and new-onset diabetes following COVID-19. Finally, by identifying the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine disorder, we aimed to estimate the cumulative long-term endocrine burden associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants in this study were adults with a confirmed history of COVID-19 who had been hospitalized during the period 2020–2021 and who did not have a prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease at the time of their initial admission. Only patients who agreed to take part in the follow-up evaluation and attended the scheduled clinical assessment four years after the acute episode were included. Individuals were excluded if they were younger than 18 years, were pregnant at the time of reassessment, or had a documented history of pre-existing diabetes or thyroid pathology prior to COVID-19 infection. Additional exclusion criteria included patients who died during the interim period, those who declined participation, and individuals who could not be contacted for the 4-year evaluation.

Incident diabetes was defined according to ADA criteria as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL measured at the 4-year reassessment. HbA1c could not be measured for participants, therefore diagnosis relied exclusively on fasting glucose values. Positivity for thyroid autoantibodies was defined based on manufacturer reference thresholds: anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) >10 IU/mL and anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) >95 IU/mL.

2.5. Data Collection and Procedures

Data were collected at two time points: (i) during the acute COVID-19 hospitalization and (ii) at a 4-year post-infection reassessment (table 1).

2.5.1. Acute Phase Data (Hospital Admission, 2020–2021)

Clinical data collected during hospitalization included demographic characteristics, comorbidities, presenting symptoms, disease severity, treatment received, oxygen or ventilatory support, length of stay, and clinical outcome. Laboratory parameters included admission blood glucose, inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen, ESR), haematological and coagulation indices (white blood cells, lymphocytes, platelets, D-dimer), tissue injury markers (AST, ALT, LDH), and renal function tests (urea, creatinine). Imaging investigations included chest X-ray or baseline and follow-up thoracic CT, along with the lowest recorded peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) in room air.

2.5.2. Four-Year Reassessment (2024–2025)

Four years after the acute episode, the participants underwent clinical and laboratory reassessment. Data collected included demographic information, updated medical history, and laboratory tests such as fasting glucose, inflammatory and hematologic markers, tissue injury markers, and renal function tests. Thyroid function was evaluated through TSH, FT4, FT3, and thyroid autoantibodies (anti-TPO, anti-Tg). Thyroid ultrasound was performed to determine structural changes including patterns suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis, nodules, or cysts. All ultrasound examinations were performed by a single senior endocrinologist using a standardized scanning protocol. Although formal intra-observer variability testing was not carried out, consistency was ensured by having the same operator conduct all assessments.

Table 1.

Variables collected at admission and at 4-year post-COVID evaluation.

Table 1.

Variables collected at admission and at 4-year post-COVID evaluation.

| Time Point |

Variable Type |

Variables Collected |

| Acute COVID-19 Admission |

Demographic Data |

Age, sex |

| |

Medical History |

Cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, metabolic, hepatic comorbidities |

| |

Clinical Data |

Presenting symptoms, disease severity, oxygen therapy or non-invasive ventilation requirement, length of hospital stay, treatments administered, clinical outcome |

| |

Laboratory Parameters |

Admission glucose, inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen, ESR), hematologic and coagulation markers (leukocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, D-dimer), tissue injury markers (AST, ALT, LDH), renal function (urea, creatinine) |

| |

Imaging Investigations |

Chest X-ray or chest CT (at admission, during hospitalization, and at discharge), lowest recorded peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂ in room air) |

| 4-Year Post-COVID Evaluation |

Demographic Data |

Age, sex |

| |

Medical History |

Cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, metabolic, hepatic comorbidities – previously existing or developed after acute COVID-19 |

| |

Laboratory Parameters |

Fasting glucose, HbA1c, inflammatory markers (CRP, ferritin, fibrinogen, ESR), hematologic and coagulation markers (leukocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, D-dimer), tissue injury markers (AST, ALT, LDH), renal function (urea, creatinine) |

| |

Thyroid Function and Autoimmunity |

TSH, FT4, FT3, thyroid autoantibodies (anti-TPO, anti-Tg) |

| |

Imaging Investigations |

Thyroid ultrasound (identification of autoimmune thyroiditis features, thyroid nodules, thyroid cysts) |

2.6. Severity Classification of COVID-19

COVID-19 severity was classified based on national and international guidelines [

24,

25]. For clarity, mild cases were defined as upper respiratory symptoms without radiologic pneumonia or hypoxemia. Moderate disease involved radiological pneumonia with SpO₂ >94%. Severe cases required the presence of respiratory distress, respiratory rate >30/min, or SpO₂ <90%. Critical illness included respiratory failure requiring ventilatory support, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, or major thrombotic events.

2.7. Analytical Approach

To evaluate the relationship between acute COVID-19 severity and the risk of long-term endocrine sequelae, patients were grouped into four categories (mild, moderate, severe, and critical), and the prevalence of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity at 4 years was compared across groups to explore potential severity-dependent effects. The predictive value of stress-induced hyperglycaemia at admission for subsequent diabetes was examined by comparing the incidence of diabetes among patients with hyperglycaemia versus normoglycemia during hospitalization.

To identify risk factors associated with post-COVID endocrine sequelae, subgroup analyses were performed based on sex, age (<60 vs. ≥60 years), pre-existing comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia), and acute COVID-19 severity. The analyses specifically investigated: (i) the influence of sex on thyroid autoimmunity, (ii) age-related susceptibility to metabolic and immune dysregulation, (iii) the role of comorbidities, particularly obesity and dyslipidaemia, in the development of new-onset diabetes, and (iiii) the possible link between severe/critical COVID-19, systemic inflammation, corticosteroid use, and long-term endocrine dysfunction.

The relationship between thyroid autoimmunity and post-COVID diabetes was explored by stratifying patients based on thyroid autoantibodies and diabetes status to evaluate potential co-occurrence. The overall post-COVID endocrine burden was estimated by calculating the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine disorder (type 2 diabetes and/or autoimmune thyroiditis).

3. Results

Of the 1009 initially eligible adults previously free of diabetes and endocrine disease, 96 completed the 4-year reassessment. Among the remaining 913 patients, 115 had died within four years of the initial COVID-19 hospitalization, 501 could not be contacted, and 297 declined in-person reassessment. This substantial non-random attrition may introduce follow-up bias and is addressed in the Limitations section.

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

The cohort consisted of 44 men (45.8%) and 52 women (54.2%), with a balanced sex distribution. Patient age ranged from 35 to 77 years. The median age of the cohort was 58 years (IQR 49–66). The largest age group was 60–69 years (33.3%), followed by 50–59 years (25.0%) and 40–49 years (22.9%). Only 14.6% of the participants were aged 70 or older, and the youngest group (30–39 years) accounted for 4.2% of the study population (table 2). This age distribution likely reflects the fact that moderate to severe COVID-19, associated with a higher risk of endocrine sequelae, was more frequently observed in middle-aged and older adults, consistent with existing literature.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients by age group.

Table 2.

Distribution of patients by age group.

| Age group (years) |

Number of patients (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| 30–39 |

4 |

4.2% |

| 40–49 |

22 |

22.9% |

| 50–59 |

24 |

25.0% |

| 60–69 |

32 |

33.3% |

| ≥70 |

14 |

14.6% |

Legend: Age distribution of patients included in the study, expressed as absolute numbers and percentages of the total cohort (n = 96).

Regarding the severity of the disease during the acute phase of COVID-19 in the reassessed cohort (n = 96), almost half of the patients (46.9%) had experienced severe or critical disease, while the remaining 53.1% had mild or moderate forms (table 3). This distribution ensured the inclusion of a significant proportion of patients at high risk of long-term complications, while preserving statistical relevance through the inclusion of less severe cases.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to acute COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to acute COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical severity |

Number of patients |

Percentage (%) |

| Mild |

26 |

27.1% |

| Moderate |

25 |

26.0% |

| Severe |

37 |

38.5% |

| Critical |

8 |

8.3% |

3.2. Relationship Between Acute COVID-19 Severity and the Risk of Subsequent Endocrine Disorders

3.2.1. Post-COVID-19 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

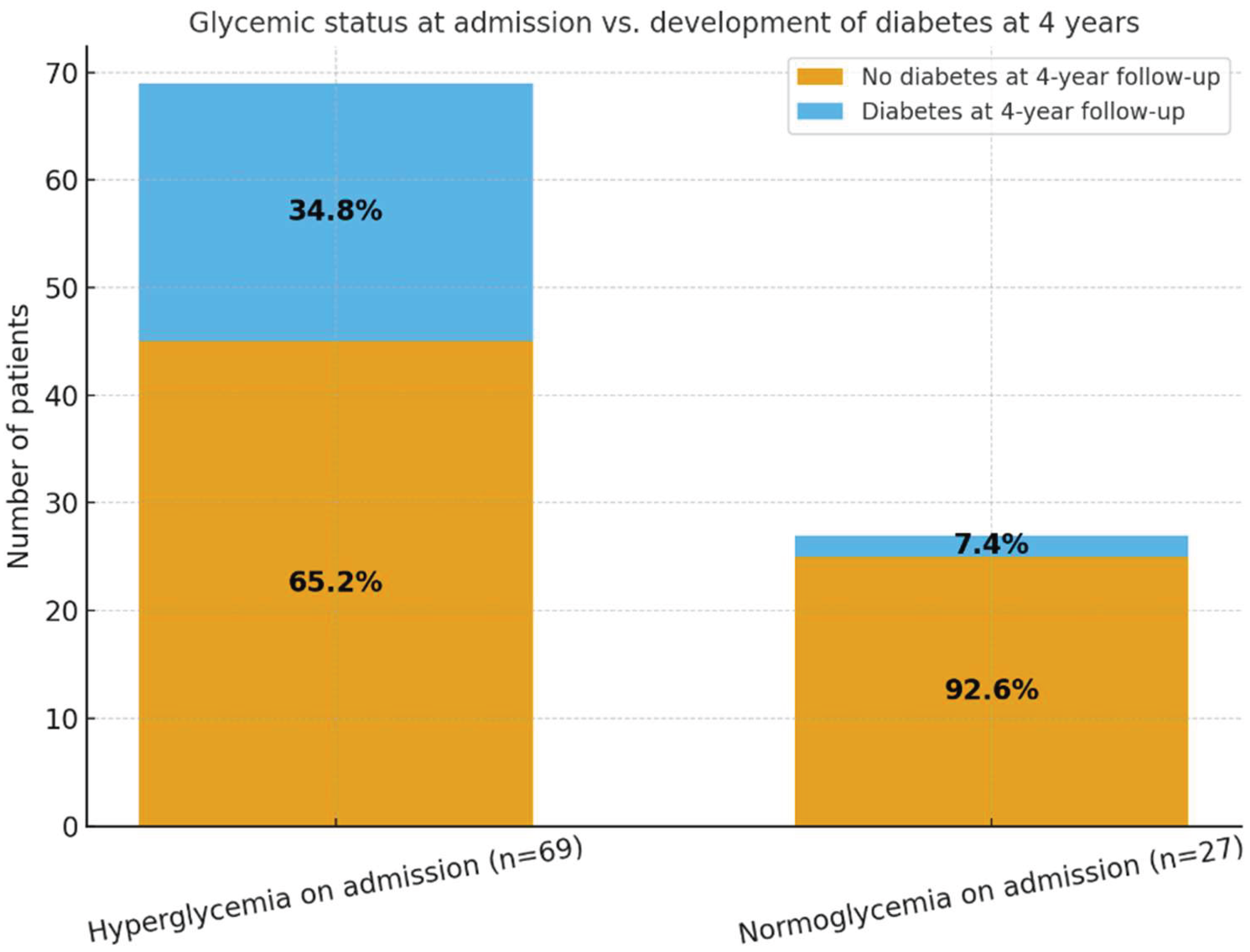

At the time of hospitalization for acute COVID-19, 69 patients (71.9%) presented with hyperglycemia, while 27 patients (28.1%) were normoglycemic. Admission glucose values were obtained at presentation, prior to the initiation of corticosteroid therapy, thereby minimizing steroid-related confounding. At the 4-year follow-up, 26 patients (27.1%) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Of these, 24 patients originated from the hyperglycaemic group, accounting for 34.8% of this subgroup, while only 2 patients (7.4%) from the normoglycemic subgroup developed diabetes.

These findings suggest a significant association between acute-phase hyperglycemia during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the later development of persistent glycaemic abnormalities. Specifically, hyperglycaemic patients had an approximately fivefold higher risk of developing diabetes compared to those who were normoglycemic at admission. This highlights the predictive potential of stress-induced hyperglycaemia during acute COVID-19 for long-term metabolic dysfunction.

Table 4 and

Figure 2 illustrate the evolution of glycaemic status in relation to the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Diabetes at follow-up was diagnosed based solely on fasting plasma glucose, as HbA1c measurements were not available.

Overall, the results emphasize the need for periodic monitoring of glucose profiles in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, even after full clinical recovery, to enable early detection of post-infectious diabetes mellitus.

Patients who exhibited hyperglycemia upon hospital admission for COVID-19 had a significantly higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4-year follow-up compared to those with normal blood glucose levels at admission. Of the 96 reassessed patients, 77 (80.2%) received corticosteroid therapy during hospitalization, predominantly dexamethasone, reflecting standard-of-care management for moderate-to-severe COVID-19. This high rate of exposure aligns with the clinical composition of the cohort, in which 46.9% had severe or critical forms of COVID-19. The substantial corticosteroid use is important for interpreting hyperglycemia patterns, although the development of long-term diabetes exceeded the proportion expected from steroid-induced transient dysglycemia alone.

The distribution of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) cases at 4 years after acute COVID-19, stratified by clinical severity, showed that patients with severe forms of COVID-19 had the highest prevalence of diabetes (40.5%), followed by those with moderate forms (32.0%). Among patients who experienced critical COVID-19, the prevalence was 12.5%, while only 7.7% of those with mild disease developed diabetes. These findings suggest a correlation between the initial severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Table 5.

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4 years according to COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 5.

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus at 4 years according to COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical Severity |

Number of Patients (n) |

T2DM Cases (n) |

Percentage (%) |

| Mild |

26 |

2 |

7.7% |

| Moderate |

25 |

8 |

32.0% |

| Severe |

37 |

15 |

40.5% |

| Critical |

8 |

1 |

12.5% |

A clear severity–diabetes gradient was observed, with T2DM prevalence increasing alongside the severity of the initial COVID-19 episode: mild (7.7%, 2/26), moderate (32.0%, 8/25), severe (40.5%, 15/37), and critical (12.5%, 1/8). Given that hyperglycemia at admission is more commonly observed in severe COVID-19 cases, these findings highlight that stress-induced hyperglycemia during the acute phase of the infection may have represented an important risk factor for the later development of diabetes. Indeed, the majority of T2DM cases occurred in patients who already exhibited elevated glucose levels during initial hospitalization (table 5).

3.2.2. Post-COVID-19 Thyroid Alterations: Functional and Structural Changes

At the 4-year follow-up, the assessment of thyroid alterations revealed notable differences based on the clinical severity of the initial COVID-19 episode. In patients who experienced mild COVID-19 (n = 26), 2 patients (7.7%) were diagnosed with autoimmune thyroiditis, 8 patients (30.8%) presented thyroid nodules, and 4 patients (15.4%) had thyroid cysts. Serologic testing revealed elevated anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) in 10 patients (38.5%), thyroglobulin antibodies (anti-Tg) in 12 patients, and dual antibody positivity (anti-TPO + anti-Tg) in 4 patients. Among patients with moderate COVID-19 (n = 25), 6 patients (24%) developed autoimmune thyroiditis, 5 (20%) showed thyroid nodules, and 6 (24%) had thyroid cysts. Anti-TPO positivity was observed in 9 patients (36%), anti-Tg in 7 patients, and dual positivity in 5 patients. In the group with severe disease (n = 37), 6 patients (16.2%) had autoimmune thyroiditis, 6 (16.2%) thyroid nodules, and 13 patients (35.1%) thyroid cysts. Elevated anti-TPO levels were detected in 12 patients (32.4%), anti-Tg antibodies in 9 patients, and dual positivity in 3 cases. Among patients with a critical form of COVID-19 (n = 8), 2 patients (25%) developed autoimmune thyroiditis, and 1 patient (12.5%) presented thyroid nodules, with no thyroid cysts observed. Notably, this group showed the highest rate of anti-TPO positivity (5 patients, 62.5%). Anti-Tg antibodies were detected in 2 patients, and dual antibody positivity in 1 patient (table 6).

Overall, thyroid abnormalities, whether structural (nodules, cysts) or immunological (anti-TPO, anti-Tg positivity), were more frequent among patients with moderate and severe COVID-19. However, even patients who had experienced mild forms of the disease showed a notable degree of thyroid involvement, underscoring the persistent risk of endocrine dysregulation in the post-COVID period. Because thyroid ultrasound was not performed during the acute COVID-19 hospitalization and pre-infection imaging was unavailable, it was not possible to determine whether the thyroid nodules or cysts identified at the 4-year assessment were newly developed or pre-existing. However, all patients with a known history of thyroid disease, regardless of etiology, were excluded from the study cohort, reducing the likelihood of including individuals with previously diagnosed structural abnormalities.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of thyroid involvement by initial COVID-19 clinical severity.

Table 6.

Comparative analysis of thyroid involvement by initial COVID-19 clinical severity.

| Clinical Severity |

Autoimmune Thyroiditis n (%) |

Thyroid Nodules n (%) |

Thyroid Cysts n (%) |

Anti-TPO+ n (%) |

Anti-Tg+ n (%) |

Double Positivity (Anti-TPO + Anti-Tg) n (%) |

| Mild (n = 26) |

2 (7.7%) |

8 (30.8%) |

4 (15.4%) |

10 (38.5%) |

12 (46.2%) |

4 (15.4%) |

| Moderate (n = 25) |

6 (24.0%) |

5 (20.0%) |

6 (24.0%) |

9 (36.0%) |

7 (28.0%) |

5 (20.0%) |

| Severe (n = 37) |

6 (16.2%) |

6 (16.2%) |

13 (35.1%) |

12 (32.4%) |

9 (24.3%) |

3 (8.1%) |

| Critical (n = 8) |

2 (25.0%) |

1 (12.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (62.5%) |

2 (25.0%) |

1 (12.5%) |

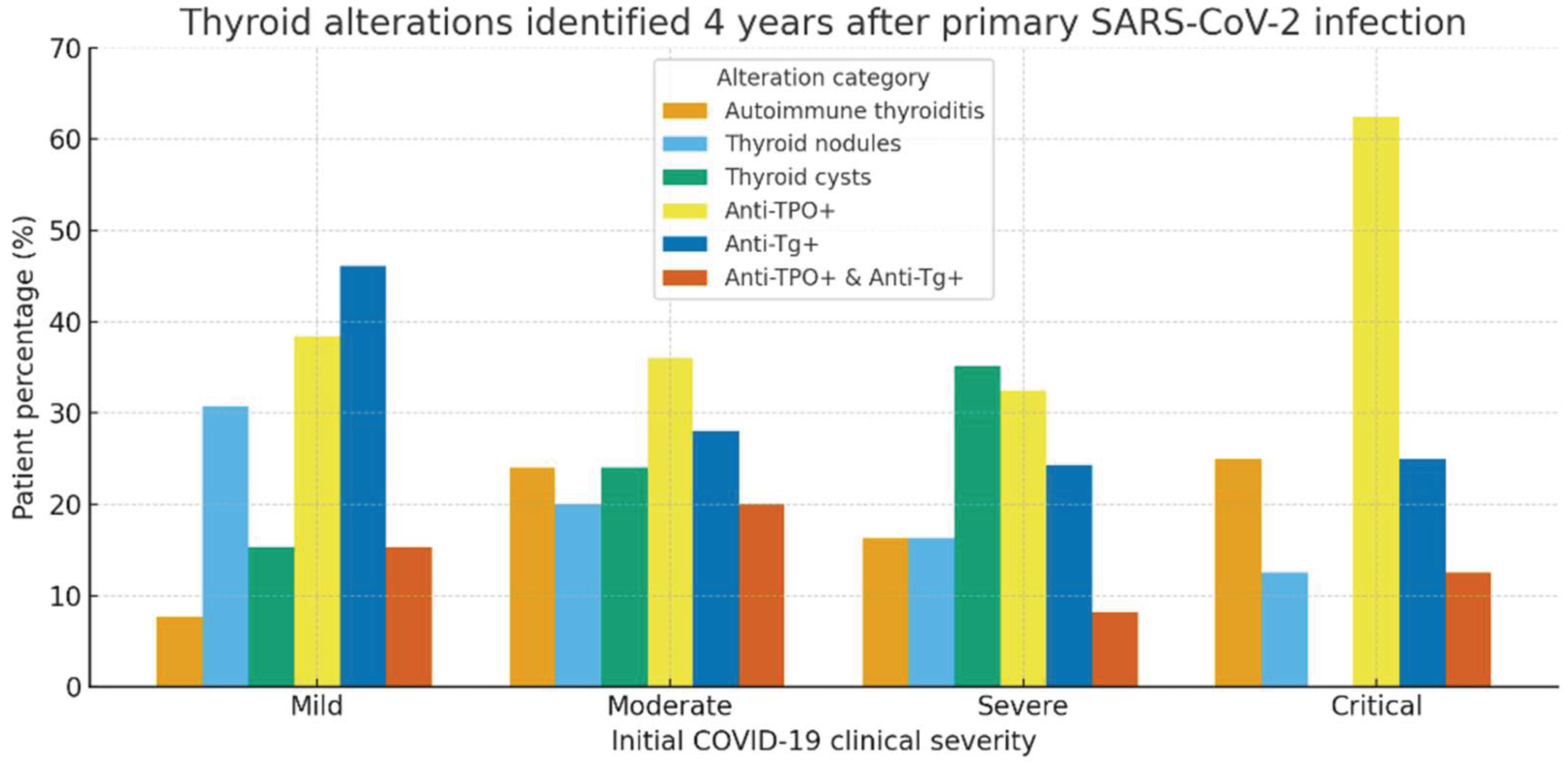

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of thyroid alterations observed four years after primary SARS-CoV-2 infection, stratified by the clinical severity of the initial COVID-19 episode. A significant prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity markers (anti-TPO and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies) was observed across all severity categories, with a trend toward higher values among patients who had severe or critical disease.

Structural abnormalities, including thyroid nodules and cysts, were also frequent, particularly among patients with moderate and severe forms of COVID-19. The critical group showed the highest rate of anti-TPO positivity (over 60%), suggesting a potential link between the severity of the acute inflammatory response and long-term thyroid autoimmunity.

Importantly, the data indicate that post-COVID thyroid impairment, both structural and immunological, is not confined to severe cases, as alterations were also detected in patients with mild disease. This underscores the relevance of long-term endocrine follow-up after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

3.3. Identification of Risk Factors for Post-COVID Endocrine Sequelae

The roles of sex, age, comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia), and the severity of the acute COVID-19 episode were assessed in relation to the risk of developing post-COVID type 2 diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroiditis. Overall, 26 of the 96 patients (27.1%) were diagnosed with newly onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patients who developed post-COVID diabetes were more frequently older (≥60 years: 61.5% vs. 38.6%, p = 0.04) and hypertensive (73.0% vs. 35.7%, p = 0.002). In addition, a substantially higher proportion had experienced severe or critical COVID-19 during hospitalization (76.9% vs. 42.9%, p = 0.005). Female sex (p = 1.000) and obesity (p = 0.38) were not associated with diabetes onset. These findings were confirmed through additional statistical testing, which demonstrated significant associations with hypertension (p = 0.002) and severe/critical disease (p = 0.005), while age ≥60 years showed only a trend toward significance (p = 0.08) (table 7).

Autoimmune thyroiditis was identified in 37 patients (38.5%). To more accurately characterize the spectrum of thyroid involvement, autoimmune thyroiditis was stratified into isolated serologic autoimmunity versus ultrasound-confirmed disease. Among these 37 patients, 24 (64.9%) exhibited isolated anti-TPO and/or anti-Tg antibody positivity without ultrasound abnormalities, while 13 patients (35.1%) demonstrated ultrasound features consistent with autoimmune thyroiditis (diffuse hypoechogenicity, parenchymal heterogeneity, or increased vascularity). None of the evaluated variables, including female sex (p = 0.35), age ≥60 years (p = 0.46), hypertension (p = 0.27), obesity (p = 1.000), or acute COVID-19 severity (p = 1.000), showed significant associations with either isolated antibody positivity or ultrasound-confirmed autoimmune thyroiditis (all p > 0.25).

Taken together, these results indicate that patients aged ≥60 years, those with hypertension, and those who experienced severe or critical COVID-19 are at substantially increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes four years after infection. In contrast, thyroid autoimmunity did not correlate with demographic factors, comorbidities, or acute disease severity, suggesting that metabolic and autoimmune mechanisms following SARS-CoV-2 infection may be driven by distinct pathogenic pathways. While post-COVID glycemic dysregulation appears closely linked to cardiometabolic vulnerability and systemic stress during acute illness, the development of thyroid autoimmunity may reflect individual immunologic predispositions or delayed post-viral immune activation.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of risk factors associated with post-COVID Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of risk factors associated with post-COVID Type 2 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis.

| Factor evaluated |

Post-COVID Type 2 Diabetes (n = 26) |

No Diabetes (n = 70) |

Post-COVID Autoimmune Thyroiditis (n = 37) |

No Thyroid Involvement (n = 59) |

| Severe / Critical COVID-19 |

p = 0.005 |

p = 0.13 |

p = 1.00 |

p = 0.63 |

| Hypertension (HTA) |

p = 0.002 |

p = 0.05 |

p = 0.27 |

p = 0.27 |

| Obesity |

p = 0.38 |

p = 0.68 |

p = 1.0 |

p = 1.00 |

| Female sex |

p = 1.00 |

p = 1.00 |

p = 0.35 |

p = 0.43 |

| Age ≥ 60 years |

p = 0.08 |

p = 0.22 |

p = 0.46 |

p = 0.52 |

3.4. Association Between Thyroid Dysfunction and Post-COVID Diabetes Mellitus

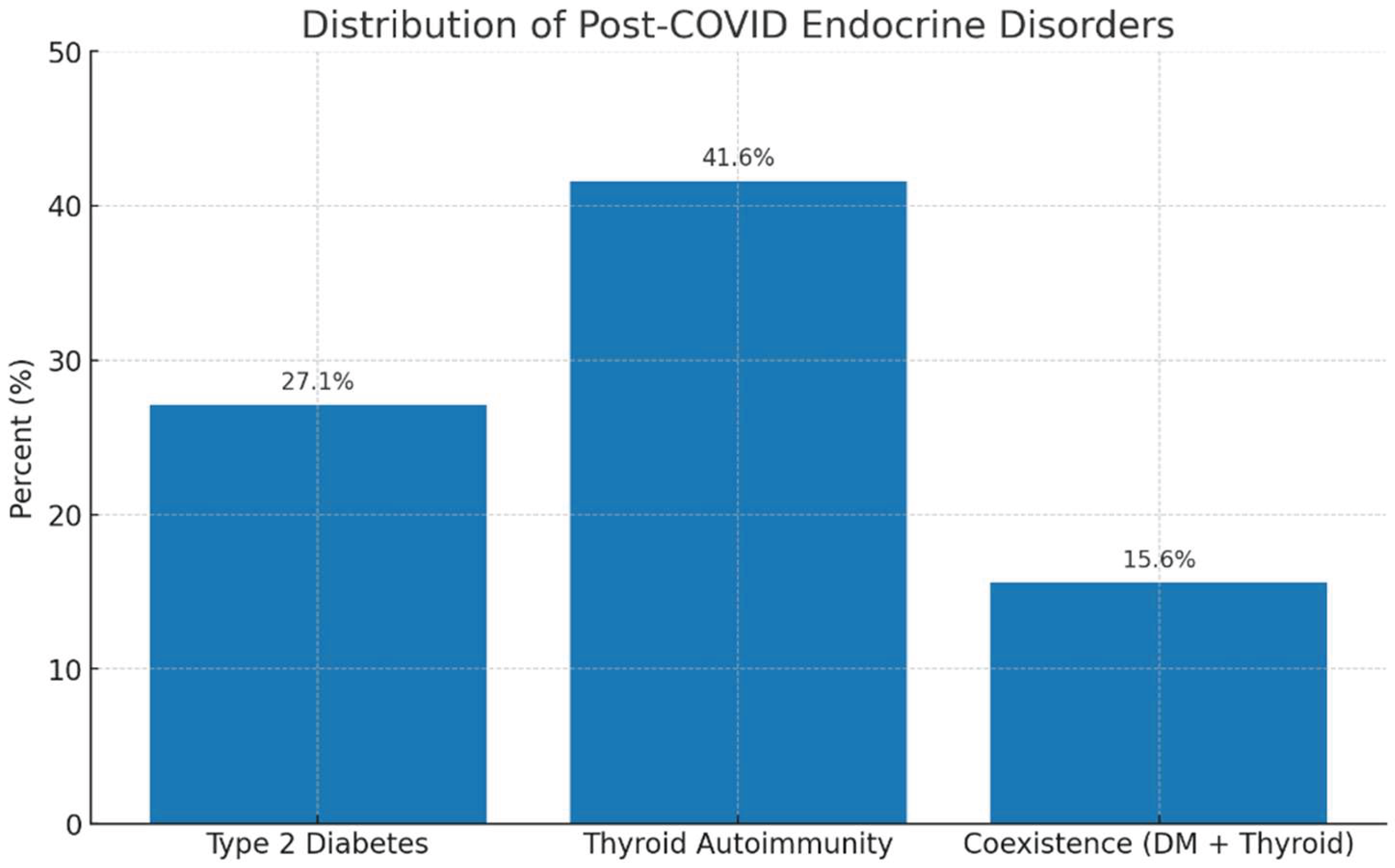

A bidirectional analysis was performed to explore the relationship between autoimmune thyroid involvement and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with the aim of assessing a potential shared pathogenic mechanism. Thyroid autoimmunity was identified in 40 out of 96 patients (41.6%), while 26 out of 96 patients (27.1%) were diagnosed with T2DM. Importantly, 15 patients (15.6%) exhibited coexistence of both conditions. Among the 40 patients with thyroid autoimmunity, 15 (37.5%) also had T2DM, whereas among the 26 patients with T2DM, 15 (57.7%) demonstrated thyroid autoimmunity, indicating a substantial bidirectional overlap between the two endocrine outcomes. In total, 46 out of 96 patients (47.9%) developed at least one endocrine disorder, either autoimmune thyroiditis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or both, while 50 patients (52.1%) showed no detectable endocrine sequelae at 4 years (table 8). This high combined burden suggests that SARS-CoV-2 infection may trigger long-lasting disturbances in both metabolic and immune pathways. These observations support the hypothesis of interconnected post-COVID endocrine dysregulation, potentially mediated by persistent inflammatory activity or delayed autoimmune mechanisms. The findings underscore the importance of integrated long-term endocrine monitoring in COVID-19 survivors, particularly among those who exhibited stress-induced hyperglycemia during hospitalization or who demonstrate thyroid autoantibodies at follow-up.

These proportional relationships indicate a substantial overlap between metabolic and autoimmune sequelae after COVID-19. Overall, the findings highlight the need for integrated endocrine monitoring in patients with a history of COVID-19, particularly in those with positive thyroid autoantibodies or stress-induced hyperglycemia at admission.

Table 8.

Distribution of post-COVID endocrine outcomes in the study cohort.

Table 8.

Distribution of post-COVID endocrine outcomes in the study cohort.

| Endocrine outcome |

n (%) |

| No endocrine disorder |

50 (52.1%) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis only |

30 (31.2%) |

| Type 2 diabetes only |

10 (10.4%) |

| Both diabetes + thyroid autoimmunity |

15 (15.6%) |

Figure 4.

Legend: The bar chart illustrates the prevalence of the main endocrine alterations identified four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thyroid autoimmunity was the most frequent finding (41.6%), followed by type 2 diabetes mellitus (27.0%), while the coexistence of both conditions was observed in 15.6% of patients. These results indicate a high prevalence of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions and suggest potential shared pathogenic mechanisms, likely mediated by persistent systemic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

Figure 4.

Legend: The bar chart illustrates the prevalence of the main endocrine alterations identified four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thyroid autoimmunity was the most frequent finding (41.6%), followed by type 2 diabetes mellitus (27.0%), while the coexistence of both conditions was observed in 15.6% of patients. These results indicate a high prevalence of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions and suggest potential shared pathogenic mechanisms, likely mediated by persistent systemic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

3.5. Global Endocrine Impact at Four-Year Follow-Up

To assess the overall endocrine impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection, we examined the proportion of patients who developed at least one endocrine dysfunction, type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or autoimmune thyroiditis, at the four-year follow-up following the acute COVID-19 episode.

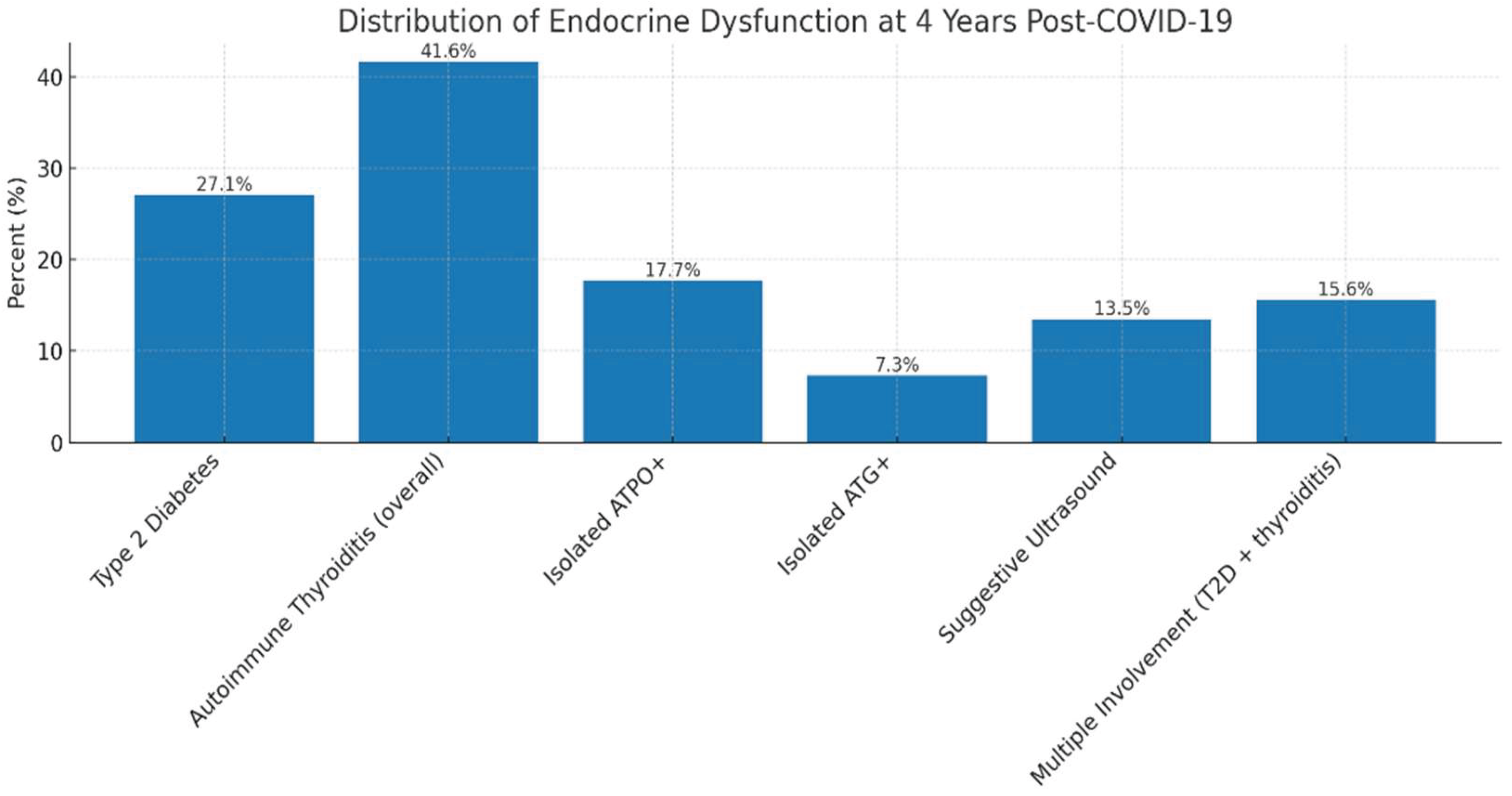

Among the 96 patients who completed reassessment, 46 (47.9%) presented a new-onset or persistent endocrine abnormality. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in 26 patients (27.1%). Serological and/or ultrasound markers of autoimmune thyroiditis were identified in 37 patients (38.5%), of whom 17 (17.7%) had isolated anti-TPO positivity, 7 (7.3%) had isolated anti-Tg positivity, and 13 (13.5%) showed ultrasound features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis (diffuse hypoechogenicity, parenchymal heterogeneity, increased vascularity). Thus, nearly half of the reassessed cohort exhibited at least one endocrine dysfunction four years after COVID-19, highlighting the substantial cumulative burden of long-term endocrine sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection (table 9).

Table 9.

Summary of endocrine outcomes four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 96).

Table 9.

Summary of endocrine outcomes four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 96).

| Endocrine outcome |

n |

% |

| No endocrine disorder |

50 |

52.1% |

| Any endocrine disorder |

46 |

47.9% |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus only |

11 |

11.5% |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis only |

21 |

21.9% |

| Coexistence: diabetes + thyroid autoimmunity |

15 |

15.6% |

| Breakdown of thyroid autoimmunity (n = 37) |

|

|

| Isolated anti-TPO positivity |

17 |

17.7% |

| Isolated anti-Tg positivity |

7 |

7.3% |

| Ultrasound-confirmed autoimmune thyroiditis |

13 |

13.5% |

Figure 6.

Legend: Distribution of endocrine dysfunctions four years after COVID-19. The bar chart displays the prevalence of different types of endocrine alterations identified at four-year follow-up. These findings underscore both the persistence and heterogeneity of long-term endocrine disturbances after COVID-19, supporting the hypothesis of shared mechanisms involving chronic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

Figure 6.

Legend: Distribution of endocrine dysfunctions four years after COVID-19. The bar chart displays the prevalence of different types of endocrine alterations identified at four-year follow-up. These findings underscore both the persistence and heterogeneity of long-term endocrine disturbances after COVID-19, supporting the hypothesis of shared mechanisms involving chronic inflammation and post-infectious immune dysregulation.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that SARS-CoV-2 infection may have sustained endocrine implications extending several years beyond the acute illness. Our results reinforce emerging evidence that COVID-19 can disrupt endocrine and metabolic homeostasis, affecting organs such as the pancreas and thyroid [

7,

10].

4.1. General Considerations on the Persistent Endocrine Implications of SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The present study provides a detailed assessment of endocrine status in previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients, evaluated four years after the acute episode. To our knowledge, this represents one of the longest follow-up investigations addressing post-COVID endocrine health, extending beyond the 6–24-month timeframe explored in most existing studies and enabling the identification of late-emerging metabolic and autoimmune disturbances [

5,

6]

At the time of reassessment, 27% of patients without a prior history of diabetes met diagnostic criteria for type 2 diabetes mellitus. This proportion aligns with the increased risk of post-COVID diabetes documented in large population-based studies [

13,

26], but its persistence at four years post-infection suggests that metabolic disturbances may remain long after clinical recovery.

A particularly relevant finding is the association between acute-phase hyperglycemia and subsequent diabetes development. Among patients who presented with hyperglycemia at admission (70.8%), 22.1% developed diabetes by the 4-year follow-up, compared with only 7.4% of initially normoglycemic patients. These results support the hypothesis that COVID-19–related stress hyperglycemia reflects an underlying metabolic vulnerability, amplified by systemic inflammation and the host immune response to viral infection [

12,

26].

Thyroid analysis revealed a high prevalence of autoimmune markers in patients with no previous thyroid disease: 29.8% had elevated anti-TPO antibodies, 17.8% had anti-thyroglobulin antibodies (ATG), and 19% showed ultrasound features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis. These rates exceed those expected in the general population (≈10–15%) and are consistent with findings from Asian and European cohorts assessed 6–12 months post-COVID [

18,

21,30].

The persistence of these abnormalities four years after infection suggests that thyroid autoimmunity may be a delayed or chronic process, even in the absence of overt symptoms. Notably, higher rates of ATPO positivity and structural thyroid changes were observed among patients who experienced moderate, severe, or critical COVID-19, reinforcing the link between systemic inflammatory burden and post-infectious thyroid autoimmunity [

20,

22].

Overall, the findings indicate that a substantial proportion of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients exhibit persistent or newly developed metabolic dysfunction, thyroid autoimmunity, and, in some cases, structural thyroid alterations detectable on ultrasound at four years post-infection. These observations support the concept that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a trigger for long-lasting endocrine disturbances, mediated by systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and possibly direct viral effects on endocrine tissues [

8,

9,

19].

The defining strength of this study lies in the unusually long interval between the initial COVID-19 infection and the time of evaluation, offering a rare perspective on the very long-term endocrine consequences of the disease. By jointly assessing thyroid function, autoimmune markers, and glucose metabolism, the study provides strong evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection can leave detectable endocrine footprints even four years after the acute episode. These findings support the need for periodic monitoring of endocrine function in patients with a history of COVID-19, particularly those who experienced severe disease or hyperglycemia during hospitalization [

6,31]. Implementing late post-infection metabolic and thyroid screening protocols may enable early detection and appropriate management of delayed endocrine complications.

4.2. New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus as a Metabolic Sequela of COVID-19

In our cohort, 27% of patients without a prior history of diabetes mellitus (DM) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at the 4-year post-infection reassessment. While this proportion is higher than the incidence typically reported within the first 6–24 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, it remains directionally consistent with trends observed in large external cohorts. Wander et al. reported a 40–60% relative excess risk of new-onset diabetes and an excess burden of 13–15 additional cases per 1000 persons at 12 months in more than 2.8 million U.S. veterans [32], including non-hospitalized individuals. Similarly, Xie and Al-Aly demonstrated persistent elevations in diabetes risk at 12–24 months across the U.S. Veterans Affairs system, with a clear severity-dependent gradient [

13,

26]. European analyses, including nationwide data from Germany, further identified incidence rate ratios of 1.2–1.6 for post-COVID diabetes compared with non-COVID respiratory infections [33].

However, the higher incidence observed in our study must be interpreted in the context of important population differences. Unlike most large-scale administrative cohorts, our sample consisted exclusively of adults who had been hospitalized for COVID-19, nearly half of whom experienced severe or critical acute illness, known risk factors for stress hyperglycemia, endocrine disruption, and cardiometabolic deterioration [

12,

16]. Additionally, our study population was older on average and had a higher burden of cardiometabolic comorbidities (particularly hypertension), both of which increase baseline vulnerability to dysglycemia. These differences in clinical profile and disease severity likely contribute to the higher cumulative rate of incident diabetes observed at the 4-year evaluation.

Several potential mechanisms may explain the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and post-infectious diabetes mellitus. In the first place, direct viral injury to pancreatic β-cells appears to play a central role. SARS-CoV-2 can infect pancreatic islet cells through ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors, leading to cytopathic effects, impaired insulin secretion, and altered β-cell gene expression. These changes may reduce the functional β-cell reserve and accelerate the transition from prediabetes to overt diabetes [

8,34,35]. Then, another mechanism involves the systemic inflammatory response, or “cytokine storm”, characteristic of acute COVID-19, which can further disrupt glucose homeostasis. Elevated proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α interfere with insulin signaling pathways, particularly the insulin receptor substrate/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (IRS/PI3K/AKT) pathway, leading to reduced glucose uptake and increased insulin resistance, promote lipolysis and hepatic gluconeogenesis, and decrease peripheral insulin sensitivity [

10,36]. Persistent low-grade inflammation after recovery may maintain this dysglycemic state. Additionally, post-infectious insulin resistance and mitochondrial dysfunction represent another pathway linking COVID-19 to chronic hyperglycemia. Endothelial injury, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial abnormalities induced by SARS-CoV-2 can aggravate hepatic and muscular insulin resistance, impair glucose utilization, and blunt compensatory β-cell responses [

9,37,38]. Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that COVID-19 may exert long-lasting metabolic effects extending well beyond the acute phase of infection.

4.3. Admission Hyperglycemia as a Predictor of Long-Term Diabetes

In our cohort, composed exclusively of adults hospitalized for COVID-19 without any previously known metabolic disorders, prediabetes, or dysglycemia, 71.9% of patients presented with hyperglycemia at the time of hospital admission. Among these individuals, 33.3% were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at the 4-year reassessment. This pattern suggests that admission hyperglycemia may result from two distinct but overlapping mechanisms: (i) true acute stress hyperglycemia driven by the inflammatory and neuroendocrine surge of COVID-19, and (ii) previously unrecognized prediabetes that becomes clinically apparent in the context of acute metabolic stress. Distinguishing between these mechanisms is essential. Acute stress hyperglycemia is typically transient and mediated by cytokine-induced insulin resistance, catecholamine and cortisol excess, and temporary β-cell dysfunction. In contrast, unrecognized prediabetes reflects a pre-existing metabolic abnormality that is “unmasked” during severe infection. Because HbA1c could not be measured during the initial hospitalization, a definitive distinction could not be made retrospectively.

Of note, 80.2% of the cohort received systemic corticosteroids during hospitalization. While glucocorticoids can induce transient hyperglycemia, the incidence of diabetes at 4 years (27.1%) was higher than expected from steroid effects alone, and most diabetes cases occurred in individuals who were already hyperglycemic at admission, prior to steroid therapy. These observations suggest that corticosteroids may have contributed to acute dysglycemia, but the long-term metabolic sequelae likely reflect underlying vulnerability and COVID-19–related inflammatory stress.

Our results align with Zhu et al., who reported that patients with admission glucose >140 mg/dL had more than twice the risk of developing diabetes compared with normoglycemic individuals [39]. This supports the concept that admission hyperglycemia is not only a marker of acute disease severity, but also a surrogate indicator of latent dysglycemia and a predictor of long-term metabolic deterioration after COVID-19 [40]. Stress hyperglycemia likely arises from excessive activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, elevated cortisol secretion, and severe cytokine-mediated insulin resistance [

8,

10,36]. In individuals with unrecognized baseline metabolic impairment, these processes may exceed β-cell compensatory capacity and hasten progression to overt diabetes

. Persistent inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction further contribute to long-term glycemic dysregulation [37,38]. These findings highlight the clinical importance of hyperglycemia detected at hospital admission, even in patients without prior metabolic disease [40].

Patients presenting with elevated blood glucose during acute COVID-19 infection should undergo long-term metabolic monitoring, even if normoglycemia is restored at discharge. Recommended follow-up assessments include HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, and lipid profile testing at 3–6 months post-discharge, and annually thereafter, to enable early detection of new-onset diabetes or prediabetes [

12]. Enhanced vigilance is particularly warranted in individuals with established cardiometabolic risk factors, such as older age, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or corticosteroid exposure during the acute illness. Implementing such strategies may facilitate timely lifestyle modifications and, where necessary, pharmacologic intervention to mitigate progression to overt diabetes mellitus.

4.4. COVID-19 and Thyroid Dysfunction: Long-Term Implications

The results of our study confirm that thyroid involvement represents one of the most frequent endocrine sequelae following COVID-19. Four years after the acute episode, nearly one-third of patients exhibited markers of thyroid autoimmunity, with 29.8% testing positive for anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies and 17.8% for anti-thyroglobulin (anti-Tg) antibodies, while 19% showed ultrasonographic features suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis. These rates are higher than those reported in the general European population (10–15%) and are comparable to findings from international post-COVID cohorts [

21,30]. In an Italian study, Campi et al. reported a 15.7% prevalence of anti-TPO antibodies three months post-infection—approximately double that observed in a pre-pandemic control group (7.7%) [30]. In a Hong Kong cohort, Lui et al. identified a 1.7% incidence at six months, particularly among patients treated with interferon beta-1b [

21]. Similar data have emerged from studies in China and Italy, where post-COVID thyroid autoimmunity prevalence ranged between 12% and 25% at 6–12 months of follow-up [42-44]. By comparison, the higher values observed in our cohort may reflect persistent residual immune activation and a cumulative long-term inflammatory effect.

When compared with population-based cohorts, these rates appear considerably higher. In the general adult population, anti-TPO positivity typically ranges from 10–15% in women aged 40–60 years and 4–7% in men, while anti-Tg positivity is reported in 8–12% depending on age and sex (Wickham Survey; NHANES III; Vanderpump et al.). The prevalence of ultrasound patterns compatible with autoimmune thyroiditis in euthyroid adults is generally around 5–10%, increasing modestly with age [

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, the markedly elevated autoantibody and ultrasound positivity rates observed in this cohort suggest a potentially COVID-related increase in thyroid autoimmunity.

To enhance clarity, we summarize the main mechanisms proposed for post-COVID thyroid autoimmunity in

Table 10, integrating current evidence related to ACE2-mediated viral injury, cytokine-induced thyroiditis, molecular mimicry, and persistent immune dysregulation

Table 10.

Proposed mechanisms linking SARS-CoV-2 infection to autoimmune thyroiditis.

Table 10.

Proposed mechanisms linking SARS-CoV-2 infection to autoimmune thyroiditis.

| Direct viral cytopathic injury |

ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression enables viral entry into thyroid follicular cells |

Follicular cell destruction → antigen release (Tg, TPO) |

| Cytokine-mediated immune activation |

Cytokine storm alters immune tolerance and antigenicity |

↑ IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β; ↑ CXCL10, CCL2 → lymphocytic infiltration |

| Molecular mimicry |

Structural similarity between SARS-CoV-2 proteins and thyroid antigens |

Cross-reactive antibodies and T cells against Tg/TPO |

| Genetic predisposition |

SARS-CoV-2 may unmask subclinical autoimmunity |

HLA-DR3 / HLA-DR5 susceptibility; loss of immune tolerance |

Several mechanisms may underlie the link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the development of post-infectious autoimmune thyroiditis. One of the most plausible explanations involves the high expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 receptors in the thyroid gland. Transcriptomic and immunohistochemical analyses have demonstrated dense ACE2 expression in thyroid follicular epithelial cells, comparable to that observed in the lung, intestine, and kidney [45,46]. This expression pattern renders the thyroid susceptible to direct viral entry, allowing SARS-CoV-2 to induce local cytopathic damage through viral replication and destruction of follicular cells. As a result, intracellular thyroid antigens—particularly thyroglobulin (Tg) and thyroid peroxidase (TPO), are released into the extracellular environment, becoming targets for the immune system. This so-called antigen spillage phenomenon may trigger secondary autoimmune responses, especially in genetically predisposed individuals carrying HLA-DR3 or HLA-DR5 haplotypes. Moreover, the local inflammatory process may upregulate adhesion and co-stimulatory molecules on follicular cells, effectively transforming them into non-professional antigen-presenting cells that perpetuate thyroid autoimmunity [45,46].

Direct infection–induced cytopathic injury is further amplified by the systemic inflammatory response characteristic of acute COVID-19, commonly referred to as the “cytokine storm.” Elevated circulating levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β can alter thyroid antigen expression and increase their immunogenicity. These cytokines also promote lymphocytic infiltration into thyroid tissue via chemokines such as CXCL10 and CCL2, while disrupting peripheral immune tolerance and activating autoreactive T and B lymphocytes [47]. Persistent low-grade inflammation and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines months or even years after infection may sustain subclinical immune activation, gradually promoting the transition to chronic autoimmune thyroiditis of the Hashimoto type [47,48].

Another key mechanism is molecular mimicry, a well-established concept in post-viral autoimmunity. Structural similarities have been identified between specific regions of the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins and thyroid autoantigens such as thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase [49,50]. This molecular homology may elicit cross-reactive immune responses, whereby lymphocytes and antibodies initially directed against viral epitopes begin to recognize and attack thyroid structures. The persistent immune stimulation during acute infection amplifies this process, potentially initiating or exacerbating autoimmune thyroiditis even after viral clearance [48,49].

Finally, SARS-CoV-2 infection may reactivate latent or subclinical autoimmune thyroid dysfunction in genetically predisposed individuals. Host genetic factors, particularly HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR5 alleles, are known susceptibility markers for autoimmune thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto thyroiditis. The interplay between virus-induced immune activation, molecular mimicry, and genetic predisposition may therefore explain the persistence of thyroid autoantibodies observed in our cohort [48,50]. In such cases, the intense systemic inflammatory response during acute COVID-19 may disrupt immune homeostasis, leading to a loss of self-tolerance and contributing to the development of chronic autoimmune thyroiditis [47,48,51]. This mechanism appears more frequently in women, consistent with known sex-related immunological dimorphism.

Most longitudinal studies indicate that thyroid dysfunctions emerging during the acute phase of COVID-19 are transient. Lui et al. (Thyroid, 2023) reported that 82.4% of patients with acute thyroid abnormalities normalized within 3–6 months. However, a subset of patients develops persistent or late-onset autoimmunity, characterized by sustained elevation of anti-TPO and/or anti-Tg antibodies at follow-up, even in the absence of overt hypothyroidism [

21,43,51]. Our findings, obtained four years after infection, confirm the existence of this subset: nearly 30% of patients exhibited serological or ultrasonographic markers of autoimmune thyroiditis, supporting the concept of a delayed post-viral autoimmune phase with slow evolution.

The persistence of thyroid autoantibodies, even without overt hormonal dysfunction, carries important clinical implications, as it may predispose to the development of progressive hypothyroidism, chronic fatigue, and other subtle metabolic disturbances [52].

Recent reviews published in

Frontiers in Endocrinology (2023) have highlighted that patients with severe COVID-19 are at an increased risk of developing thyroid dysfunction, including non-thyroidal illness syndrome during the acute phase and autoimmune thyroiditis during long-term follow-up. The persistence of elevated thyroid autoantibody titters has been reported particularly among subgroups of patients with marked inflammatory responses [53]. Given these findings, periodic monitoring of thyroid function is recommended for individuals with a history of COVID-19, especially those who experienced moderate or severe disease with elevated inflammatory markers during the acute phase [

21,44]. Reevaluation should be performed 12–24 months after infection, even in the absence of clinical symptoms, and should include measurement of TSH, FT4, and FT3, assessment of anti-TPO and anti-Tg antibodies, and thyroid ultrasonography to allow early detection of structural or functional abnormalities. These manifestations reflect the systemic impact of the virus on immune–endocrine homeostasis, underscoring the potential for chronic sequelae and the importance of long-term multidisciplinary follow-up [6,55 57].

4.5. Endocrine autoimmunity – a potential link in post-COVID syndrome (PASC)

Our study provides additional evidence supporting the hypothesis that endocrine autoimmunity may represent a key component of the complex spectrum of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). This syndrome is defined by the persistence or emergence of new symptoms more than 12 weeks after the acute infection, in the absence of alternative explanations, and encompasses a wide range of systemic manifestations, including chronic fatigue, cognitive impairment (“brain fog”), respiratory dysfunction, cardiovascular involvement, and metabolic disturbances [55,56].

In this context, the thyroid and metabolic dysfunctions observed four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection may be interpreted not merely as isolated sequelae, but as endocrine expressions of long COVID syndrome. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–peripheral axes, residual inflammation, and persistent autoimmunity may account for part of the nonspecific symptomatology observed in these patients, particularly fatigue, reduced physical performance, and mild cognitive disturbances [57,58].

Thyroid autoimmunity, identified in nearly one-third of re-evaluated patients, may contribute to certain physiological alterations relevant to post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Even in the absence of overt hypothyroidism, anti-TPO and anti-Tg positivity can reflect subclinical thyroid dysfunction, which may subtly affect energy metabolism and thermoregulatory or neuromuscular pathways. Previous studies have shown that early-stage autoimmune thyroiditis can be associated with symptoms such as fatigue and impaired concentration, which partially overlap with those reported in long COVID [59,60].

Post-COVID metabolic disturbances, including new-onset diabetes and residual insulin resistance, may further contribute to systemic inflammation [

12,61]. Chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance are known to activate proinflammatory pathways and oxidative stress mechanisms, potentially reinforcing low-grade inflammation [62,63]. These interconnected processes may help explain why some individuals exhibit prolonged metabolic or constitutional symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection [48], although our study did not assess clinical PASC manifestations directly.

Overall, while our data indicate a high prevalence of endocrine abnormalities four years after COVID-19, the relationship between these findings and specific PASC symptoms remains hypothetical and requires future studies incorporating symptom-based assessments.

Patients presenting with persistent fatigue, exercise intolerance, or cognitive disturbances should be evaluated for subclinical hypothyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity, while post-infectious glycemic monitoring may help prevent delayed diagnosis of post-COVID diabetes mellitus. Implementing a multidisciplinary follow-up protocol involving infectious disease specialists, endocrinologists, and rehabilitation experts could significantly improve functional outcomes and quality of life in these patients [60]. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of recognizing endocrine autoimmunity as a potential driver of long-term systemic symptoms in post-COVID syndrome and underscore the need for integrated clinical management strategies.

4.6. Interaction Between Metabolic and Thyroid Axes and Risk Factors for Post-COVID Endocrine Sequelae

There is a close interrelationship between thyroid function and glucose metabolism, both systems being regulated through interconnected hormonal mechanisms. Thyroid hormones influence insulin sensitivity, hepatic glucose production, and basal metabolic rate, whereas insulin and metabolic status modulate the peripheral conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3) [64,65]. Hypothyroidism, even in its subclinical form, leads to reduced insulin clearance, decreased expression of glucose transporters (GLUT-4), and increased insulin resistance at both muscular and hepatic levels [66]. Conversely, hyperthyroidism enhances hepatic gluconeogenesis and protein catabolism, thereby promoting hyperglycemia [62]. These bidirectional alterations explain the high prevalence of glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus among patients with thyroid dysfunction [62,65]. In the post-COVID context, where autoimmune thyroid involvement and persistent insulin resistance may coexist, a vicious endocrine–metabolic cycle can develop. Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress induce both thyroid autoimmunity and impaired insulin sensitivity; in turn, chronic hyperglycemia and insulin resistance sustain low-grade inflammation, perpetuating thyroid injury [61,62].

In our cohort, a partial overlap was observed between patients with thyroid autoimmunity and those diagnosed with post-COVID diabetes, suggesting the presence of shared pathogenic mechanisms. This association aligns with evidence from previous studies showing that persistent systemic inflammation, a hallmark of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, can sustain both thyroid autoimmunity and metabolic dysregulation through overlapping immune–endocrine pathways [54]. Furthermore, recent comprehensive reviews have highlighted that COVID-19–related thyroid disorders often coexist with insulin resistance and other components of metabolic dysfunction, supporting a bidirectional link between autoimmune and metabolic sequelae [58].

Risk factor analysis in our cohort suggests that the development of post-COVID endocrine sequelae, both new-onset diabetes mellitus and thyroid autoimmunity, reflects an interaction between individual predisposition and the inflammatory burden during acute infection. Female sex showed a higher prevalence of thyroid autoimmunity, consistent with the known increased susceptibility of women to autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto thyroiditis [59]. Older age (≥60 years) was also associated with a higher frequency of both diabetes and thyroid dysfunction, likely reflecting immunosenescence, reduced β-cell reserve, and the accumulation of metabolic comorbidities [

6]. The severity of the acute COVID-19 episode emerged as one of the strongest predictors of long-term endocrine disturbances, in line with previous large-cohort studies reporting a severity-dependent gradient in post-COVID diabetes risk [

13]. With respect to thyroid involvement, earlier findings by Campi et al. and Lui et al. indicated a similar association between heightened acute inflammatory responses and persistent elevations in anti-TPO titters at 6–12 months [

21,61]. Furthermore, obesity and dyslipidemia were associated with increased risk of post-COVID diabetes, reinforcing their role as baseline metabolic vulnerabilities that amplify inflammatory and insulin-resistant states [

10,61].

Although multivariable analysis would have strengthened these observations, it could not be performed due to the limited sample size and the small number of events in several subgroups. As a result, our conclusions rely on univariate associations, which we have interpreted with caution. Overall, these findings support the notion that severe acute disease, systemic inflammation, and adverse metabolic profiles may synergistically shape long-term endocrine risk after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Defining this risk profile may guide targeted post-COVID endocrine screening and tailored follow-up strategies for high-risk patients [66].

4.7. The Significance of the Cumulative Endocrine Burden After COVID-19

The high proportion of patients exhibiting endocrine dysfunctions four years after SARS-CoV-2 infection highlights the systemic and long-lasting impact of COVID-19 on metabolic and immune homeostasis. Nearly half of the cohort (47.9%) presented at least one endocrine abnormality, either new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus or thyroid autoimmunity, supporting the concept that post-COVID syndrome has a multisystemic profile with a marked endocrine component. These findings align with international studies reporting elevated risks of both incident diabetes and thyroid autoimmunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection [

26,

27].

When compared with non-COVID background rates in the general population, the cumulative endocrine burden in our cohort appears substantially higher. Large epidemiological studies report a 4–7% incidence of type 2 diabetes over a comparable 3–5-year period in non-infected adults [67], whereas 27.1% of our patients developed diabetes at four years. Similarly, population studies such as the Whickham Survey and NHANES III show 10–15% anti-TPO positivity in women and 4–7% in men, and 5–10% prevalence of ultrasound patterns suggestive of autoimmune thyroiditis in euthyroid adults [

27,

28,

29]. In contrast, 41.6% of our cohort had serological and/or structural markers of thyroid autoimmunity at four years.

The coexistence of thyroid autoimmunity and type 2 diabetes in 15.6% of patients further supports the notion of a post-COVID immunometabolic phenotype, in which shared mechanisms, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation, drive interrelated endocrine consequences [

14,56]. This cluster resembles post-viral polyautoimmune syndromes described after Epstein–Barr virus or cytomegalovirus infections but appears more pronounced due to the multisystemic tropism of SARS-CoV-2 [48,68].

From a clinical perspective, these results underscore the need to incorporate systematic endocrine screening into long-term post-COVID follow-up. An integrated surveillance algorithm, including fasting glucose, HbA1c, TSH, FT4, and anti-TPO/anti-Tg antibody testing, may allow early detection of emerging abnormalities and facilitate interventions aimed at reducing the long-term metabolic and functional burden of COVID-19.

4.8. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, only 96 of the 1009 initially eligible patients (9.5%) completed the 4-year reassessment. Although this follow-up rate is comparable to that reported in other long-term post-COVID studies, the substantial loss to follow-up (due to mortality, non-response, or refusal) reflects a distinctly non-random attrition pattern. This may have introduced selection bias, as participants who agreed to return for evaluation may differ systematically from those lost to follow-up, potentially leading to an overestimation of the true prevalence of post-COVID endocrine abnormalities. Consequently, subgroup analyses, particularly those stratified by age or sex, are based on small numbers and should be interpreted cautiously.

A further limitation is the absence of pre-COVID endocrine data. No baseline biochemical or ultrasonographic assessments were available, making it impossible to determine whether some of the abnormalities detected, particularly autoimmune thyroid markers, were already present in a latent, subclinical form prior to infection. Individuals with such underlying susceptibilities may have been at higher risk of severe COVID-19 and thus disproportionately represented in the hospitalized cohort. Therefore, while the study identifies post-COVID associations, it does not allow inference of causality. Establishing causal relationships would require dynamic longitudinal monitoring with measurements obtained both before and after infection, an approach that was not feasible during the pandemic.

Regarding glycemic outcomes, the temporal pattern observed in our cohort, absence of known pre-existing dysglycemia, new-onset hyperglycemia during hospitalization, and persistent abnormalities at discharge, supports a potential COVID-related contribution. In contrast, for thyroid outcomes, the lack of pre-infection antibody or ultrasound data means that undiagnosed autoimmune thyroiditis cannot be ruled out, and these findings should therefore be interpreted with appropriate caution. Thus, it is unclear whether the detected abnormalities developed early and persisted or whether they represent late-onset phenomena arising gradually over the four-year period.

Lifestyle changes during and after the pandemic, including reduced physical activity, weight gain, psychological stress, sleep disruption, and dietary modifications, may also have contributed independently to the development of metabolic abnormalities during the four-year interval [69]

Finally, multivariable regression analysis could not be performed due to the limited number of outcome events and incomplete baseline information, particularly regarding pre-infection metabolic status and cumulative steroid exposure. Under these conditions, fully adjusted models would be statistically unstable and prone to overfitting. Therefore, the associations reported should be regarded as exploratory rather than causal. Larger multicentric studies with robust pre- and post-infection data are needed to clarify the independent contribution of COVID-19 severity to long-term endocrine outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this study provides one of the longest and most comprehensive post-COVID endocrine evaluations published to date. By integrating biochemical, immunological, and ultrasonographic assessments of both metabolic and thyroid axes, it offers valuable insights into the sustained impact of SARS-CoV-2 on endocrine homeostasis and underscores the necessity of long-term, multidisciplinary follow-up in COVID-19 survivors.

4.9. Future Directions

The results of this study outline several priority areas for future research. To precisely define the temporal trajectory of post-COVID endocrine dysfunctions, prospective studies with periodic assessments of glucose metabolism, thyroid function, and other endocrine axes (adrenal, gonadal) are needed. Expanding research to a multicenter level would allow for more representative findings and enable comparisons across regional, genetic, and therapeutic differences. The implementation of dedicated clinical registries would facilitate the systematic collection of data regarding the prevalence, types, and progression of endocrine disorders, support international comparisons, and inform public health policies aimed at the long-term monitoring of COVID-19 survivors. Based on the current observations, inclusion of fasting glucose, HbA1c, TSH, FT4, and anti-thyroid antibody testing in the standard follow-up protocol for post-COVID patients is warranted. A multidisciplinary approach involving specialists in infectious diseases, endocrinology, immunology, and rehabilitation could optimize early diagnosis and functional recovery in these patients.

Abbreviations

ACE2 — Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2

ATG — Anti-Thyroglobulin Antibodies

ATPO — Anti-Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies

COVID-19 — Coronavirus Disease 2019

FT3 — Free Triiodothyronine

FT4 — Free Thyroxine

HbA1c — Glycated Hemoglobin

HPA — Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis

IFN — Interferon

IL 6— Interleukin 6

IR — Insulin Resistance

NF-κB — Nuclear Factor Kappa B

NTIS — Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome

PASC — Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19

RAAS — Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System

RT-PCR — Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

SARS-CoV-2 — Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

T2DM — Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Tg — Thyroglobulin

TMPRSS2 — Transmembrane Serine Protease 2

TNF-α — Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha

TPO — Thyroid Peroxidase

TSH — Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone