Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

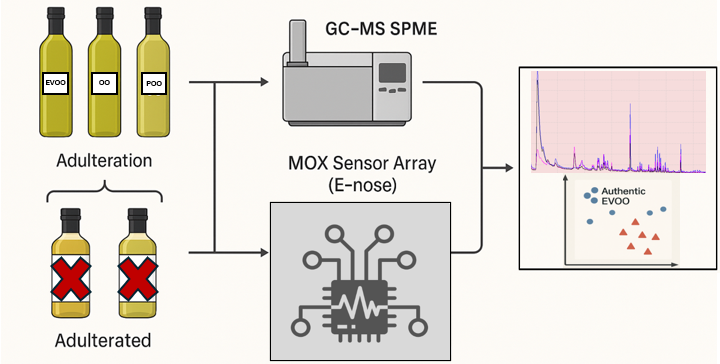

2.1. Experiment Design

2.2. Sample Preparation and Characterization of Oil Samples

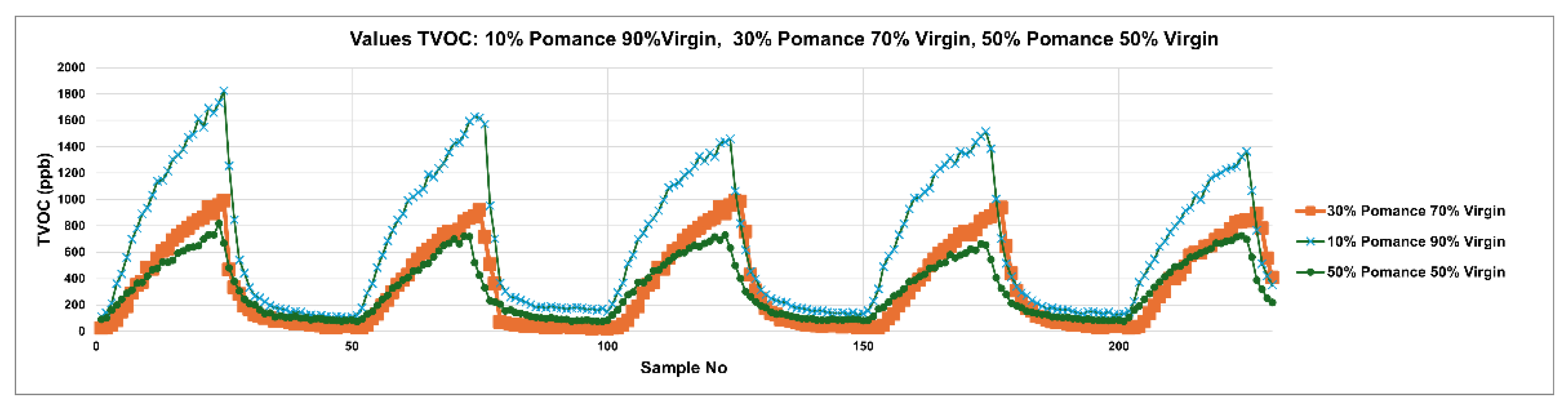

- 50% mixtures: three samples, obtained by combining 50 mL of POO with 50 mL of EVOO DOP; 50 mL of OO with 50 mL of EVOO DOP; and 50 mL of OO with 50 mL of POO.

- 30% mixtures: two samples, one consisting of 30 mL of POO and 70 mL of EVOO DOP, and the other of 30 mL of POO and 70 mL of OO.

- 10% mixtures: two samples, one containing 10 mL of POO and 90 mL of EVOO DOP, and the other 10 mL of POO and 90 mL of OO.

2.2. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

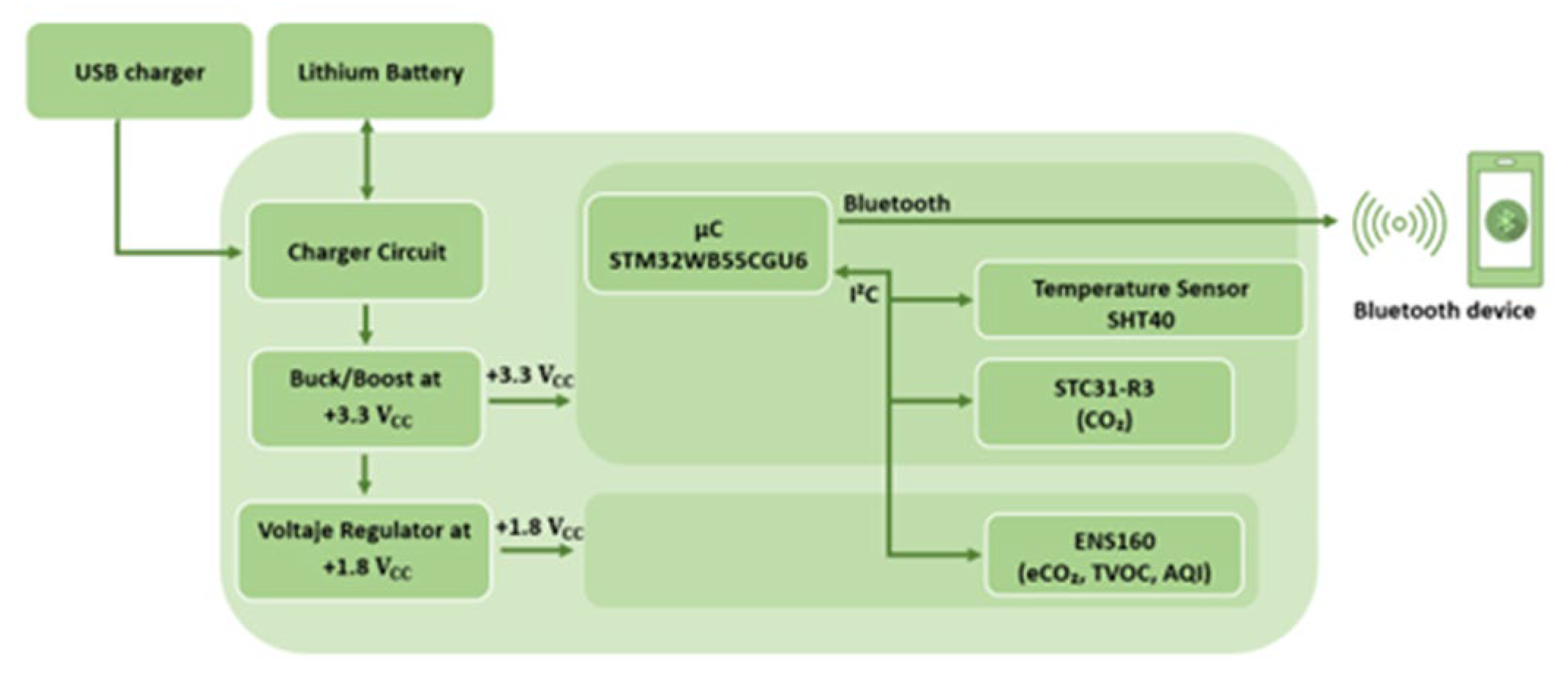

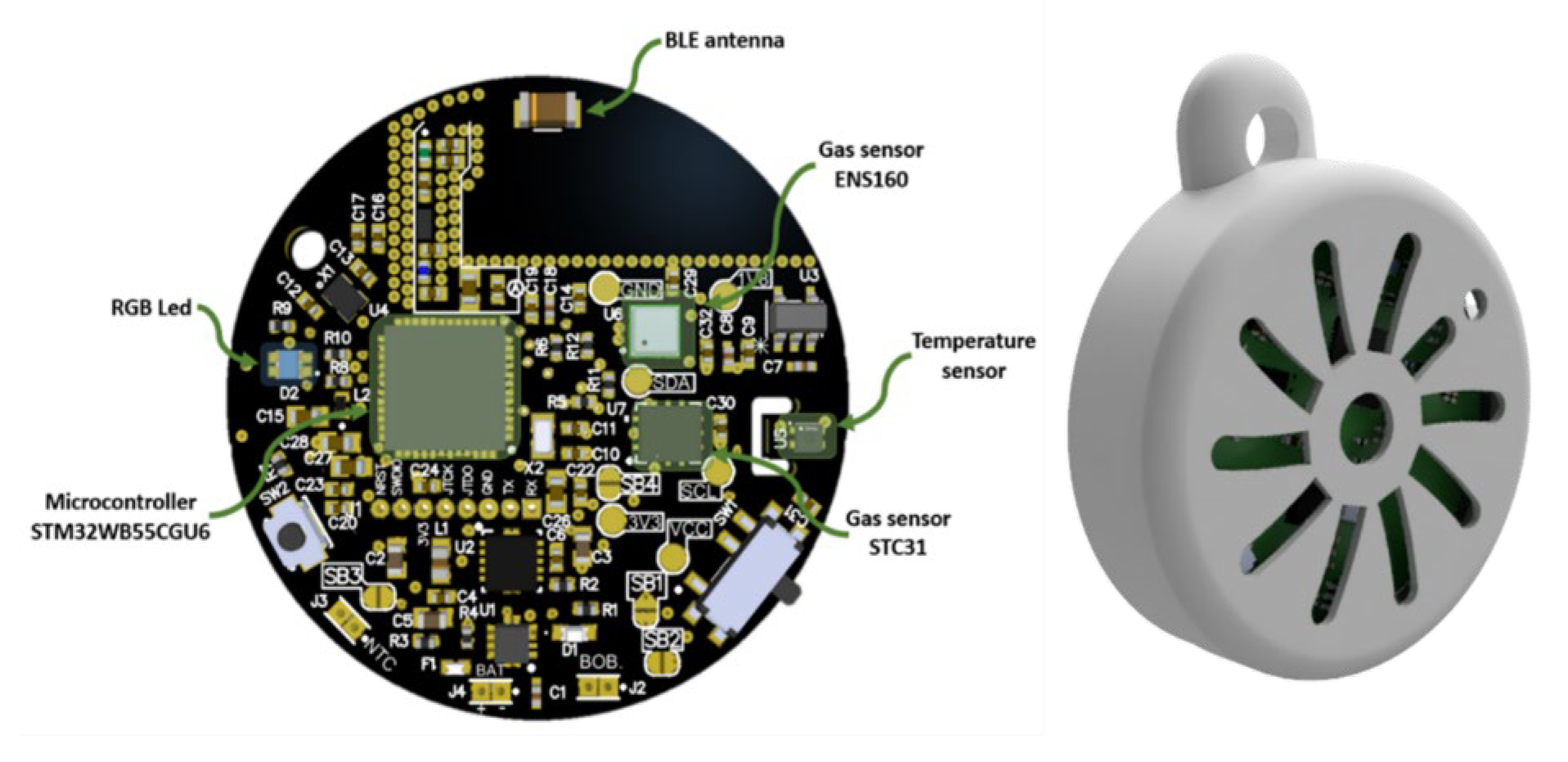

2.3. Electronic Nose Set Up

3. Results and Discussion

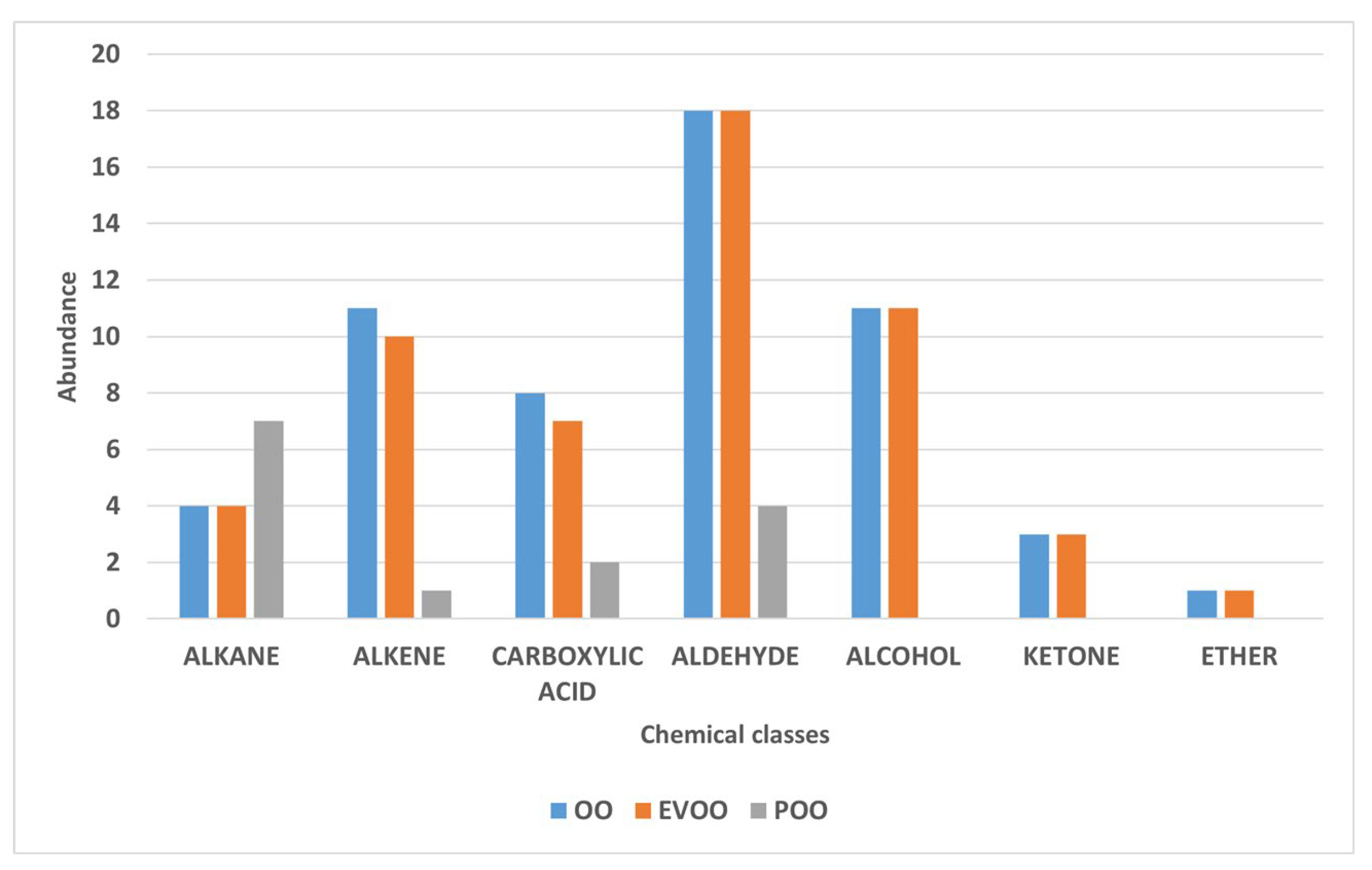

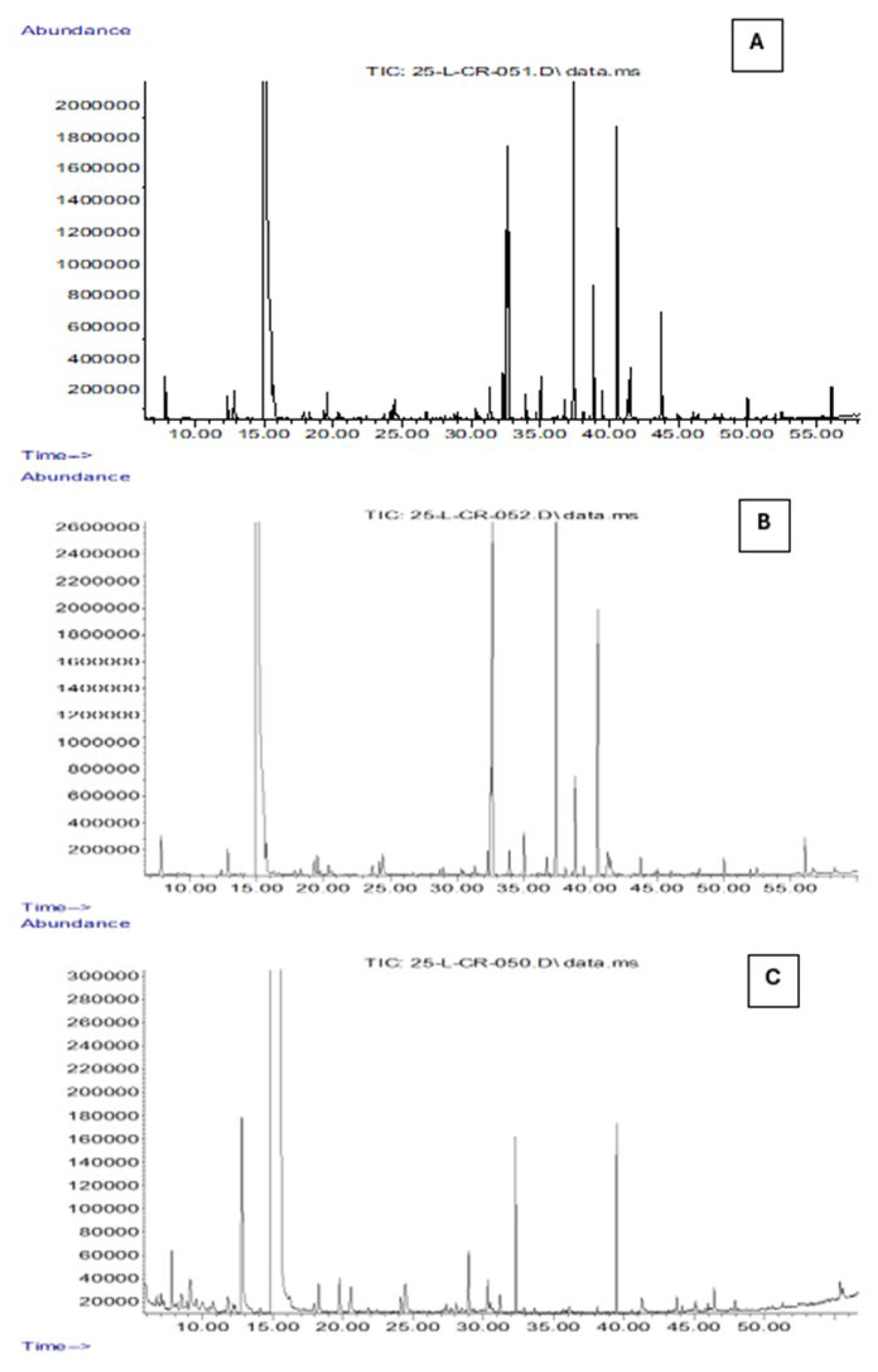

3.1. Characterization and Comparison of the Volatile Components of Pure Oils Using SPME-GC-MS

3.2. Measurement Setup

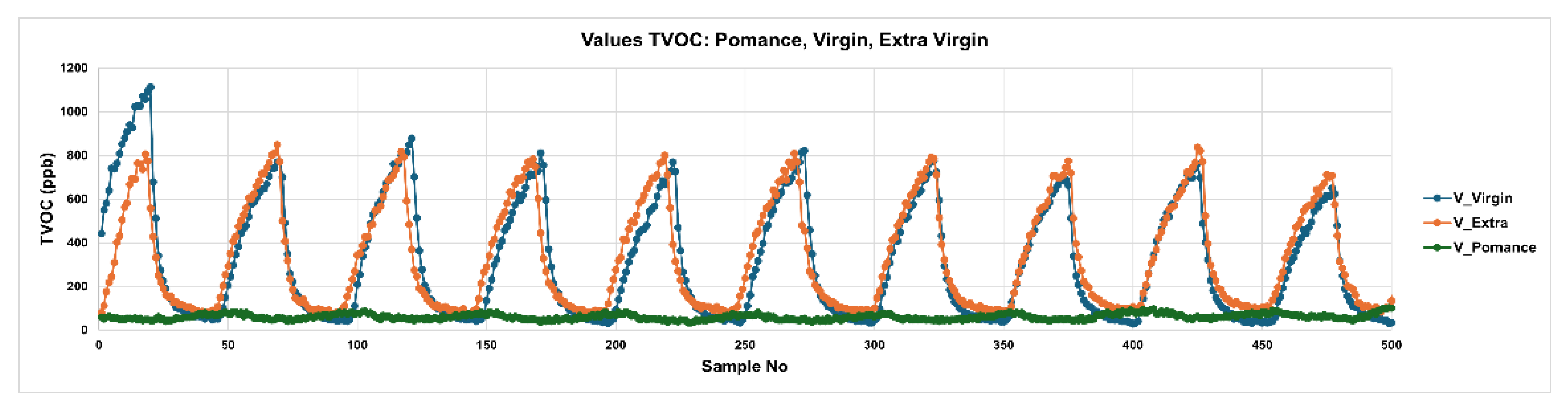

3.2.1. Temporal Response of the Sensors

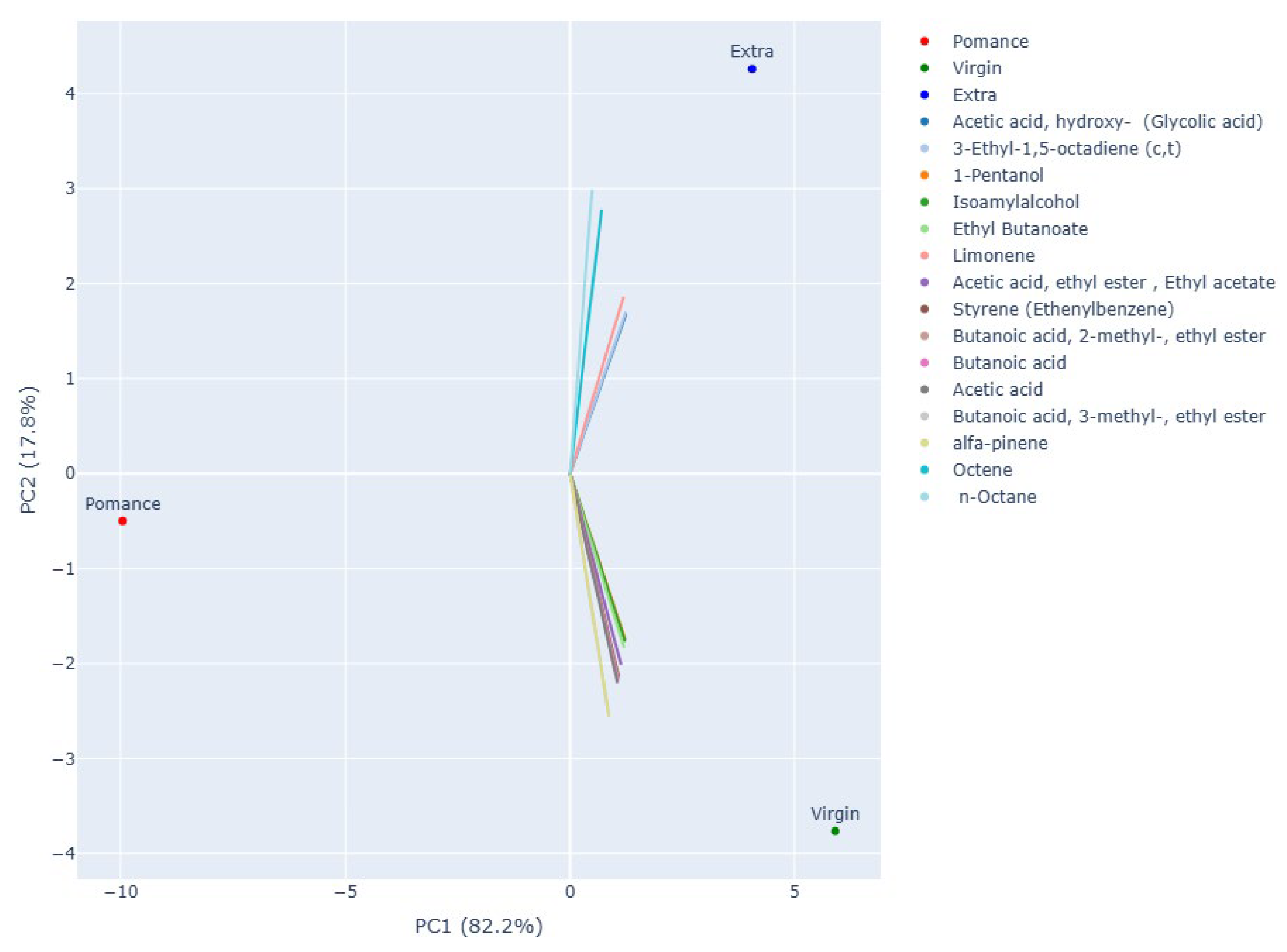

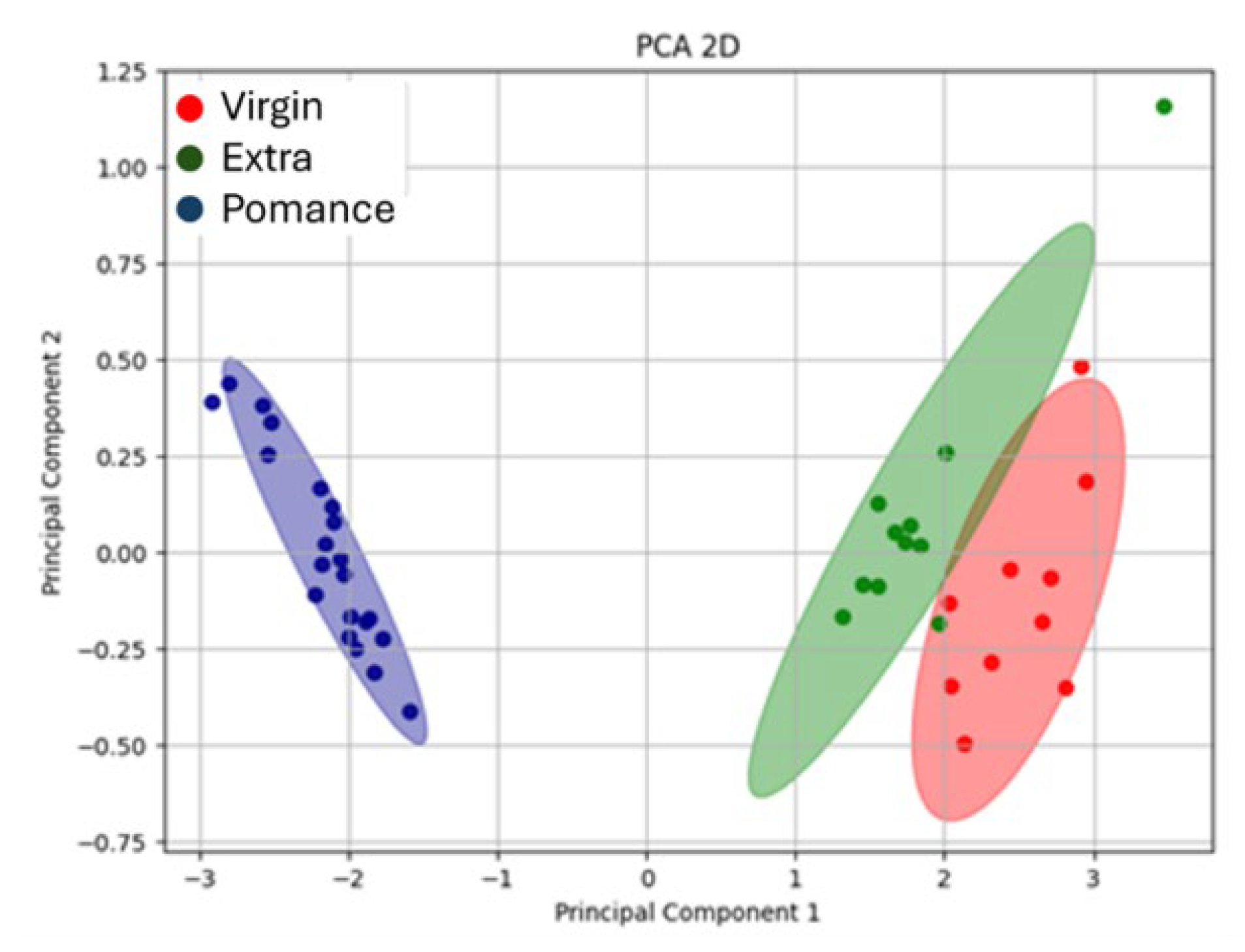

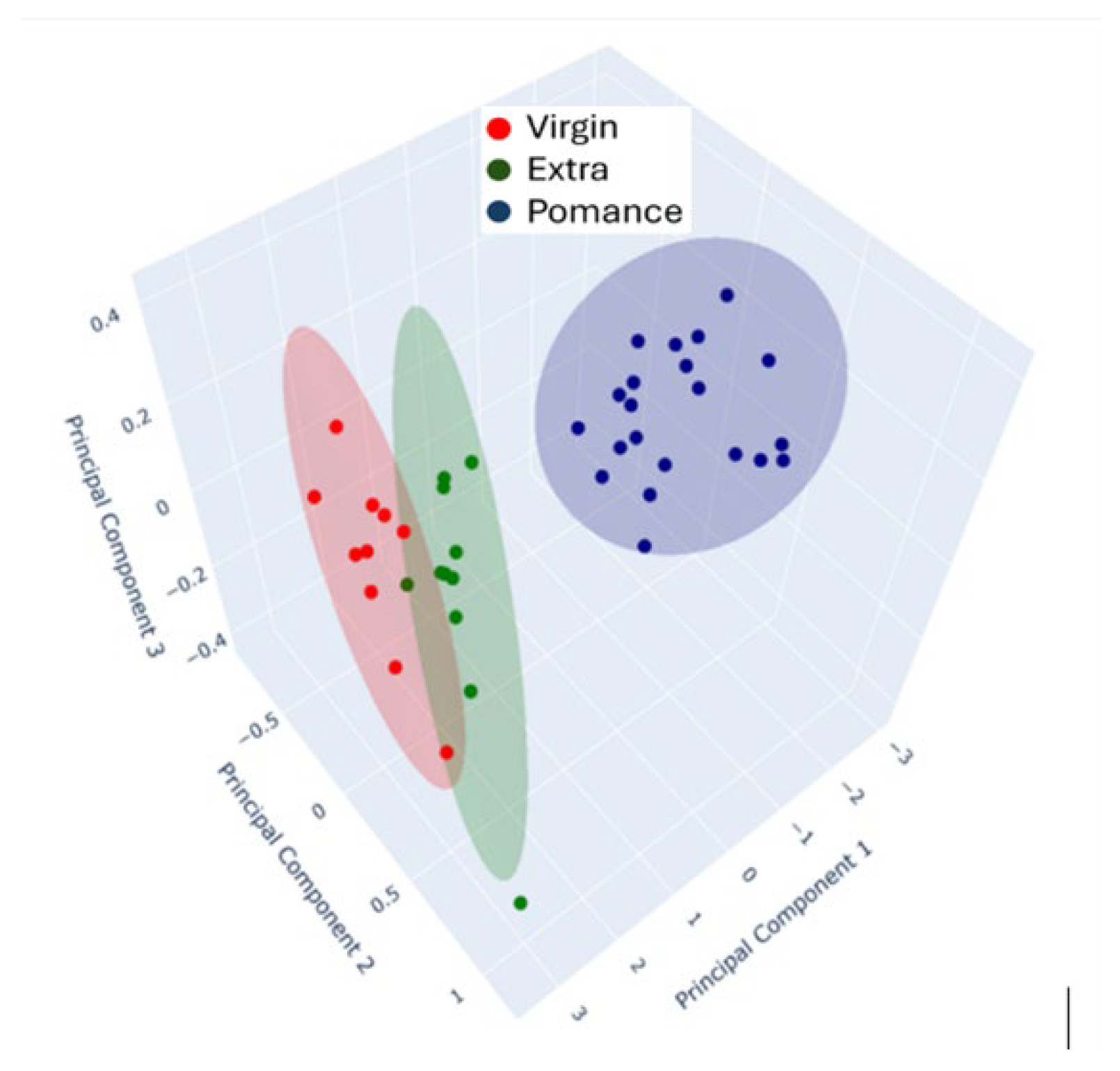

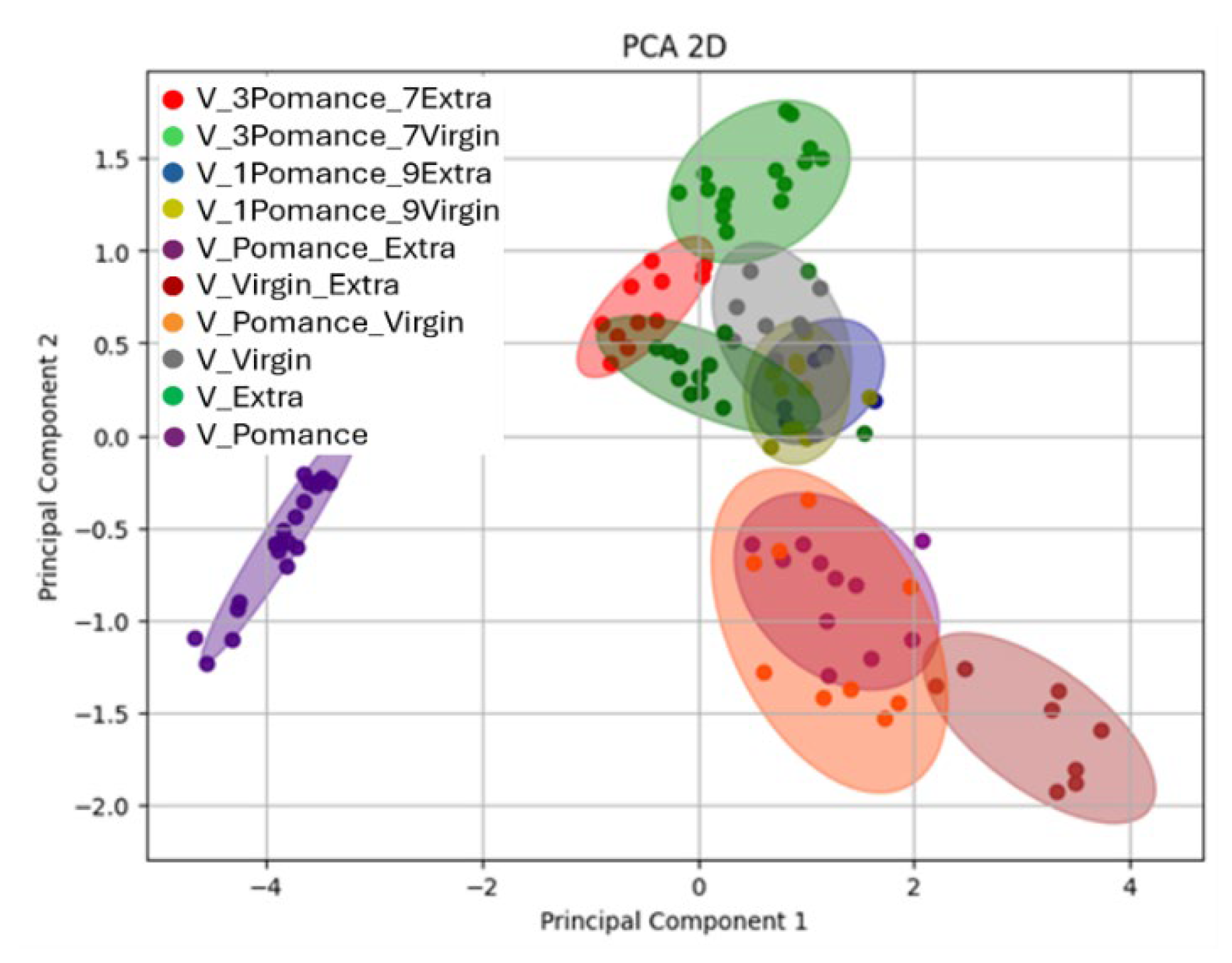

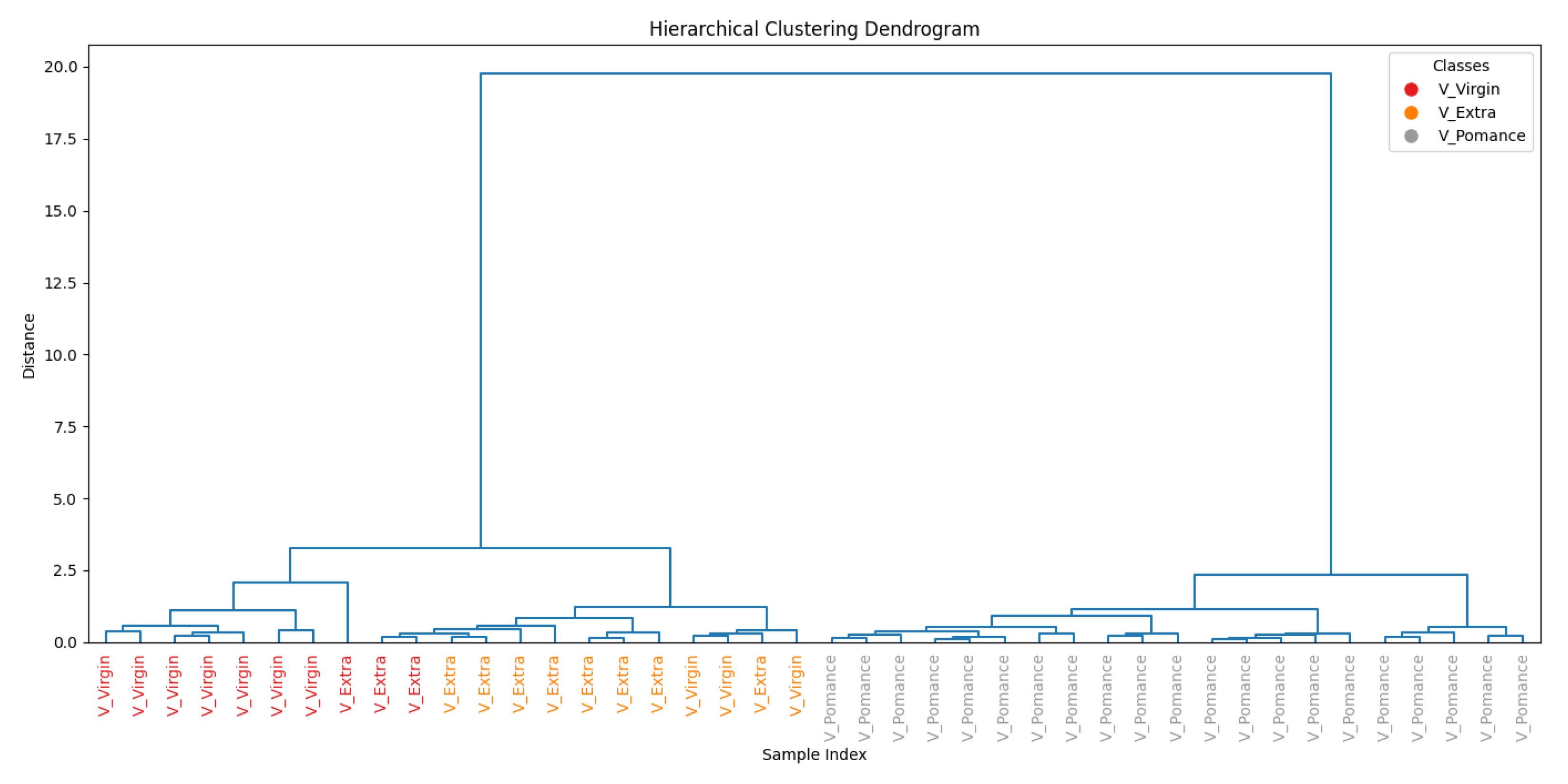

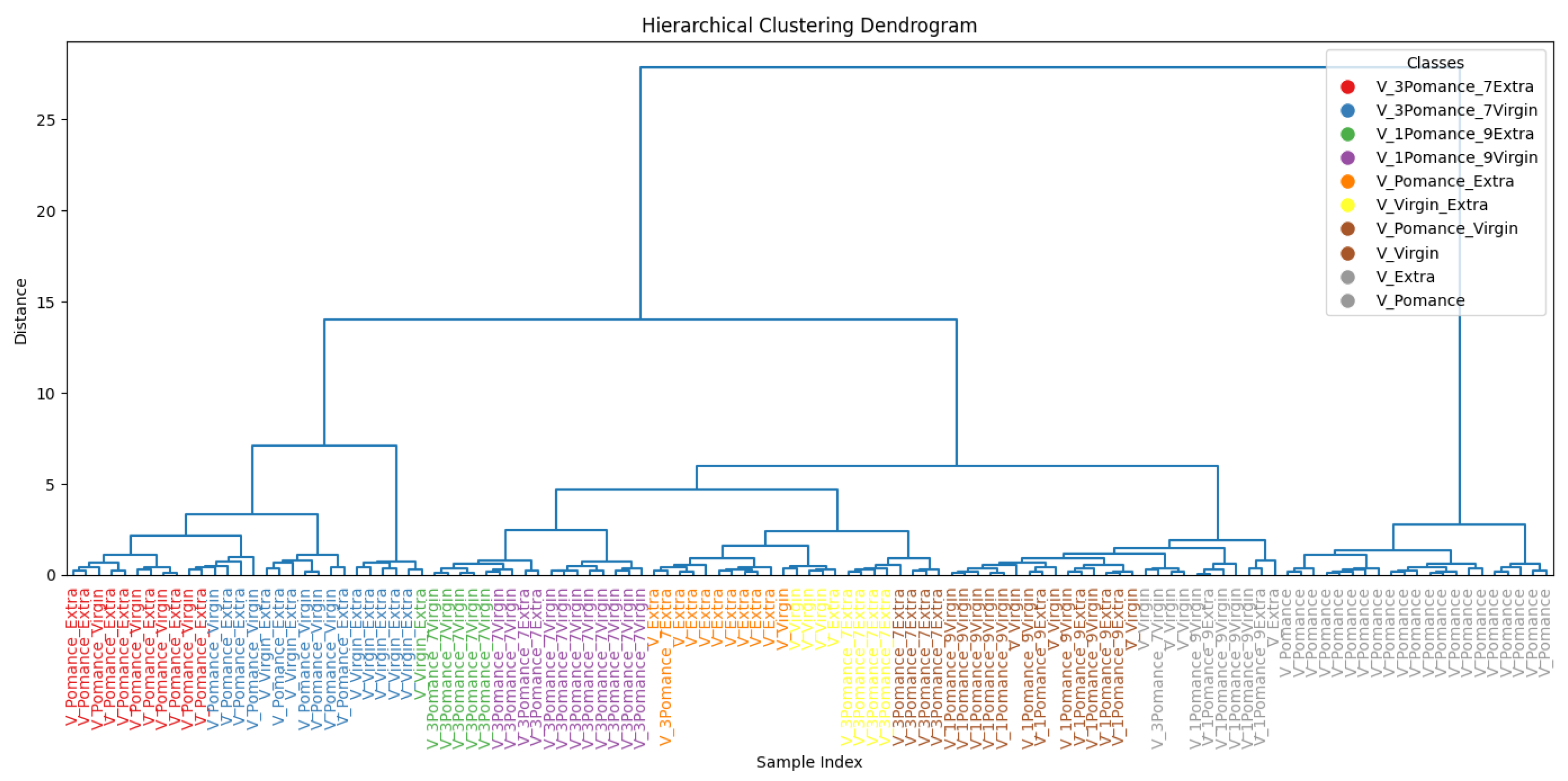

3.3. Discrimination of Oil Samples Using a MOX Sensor-Based Device

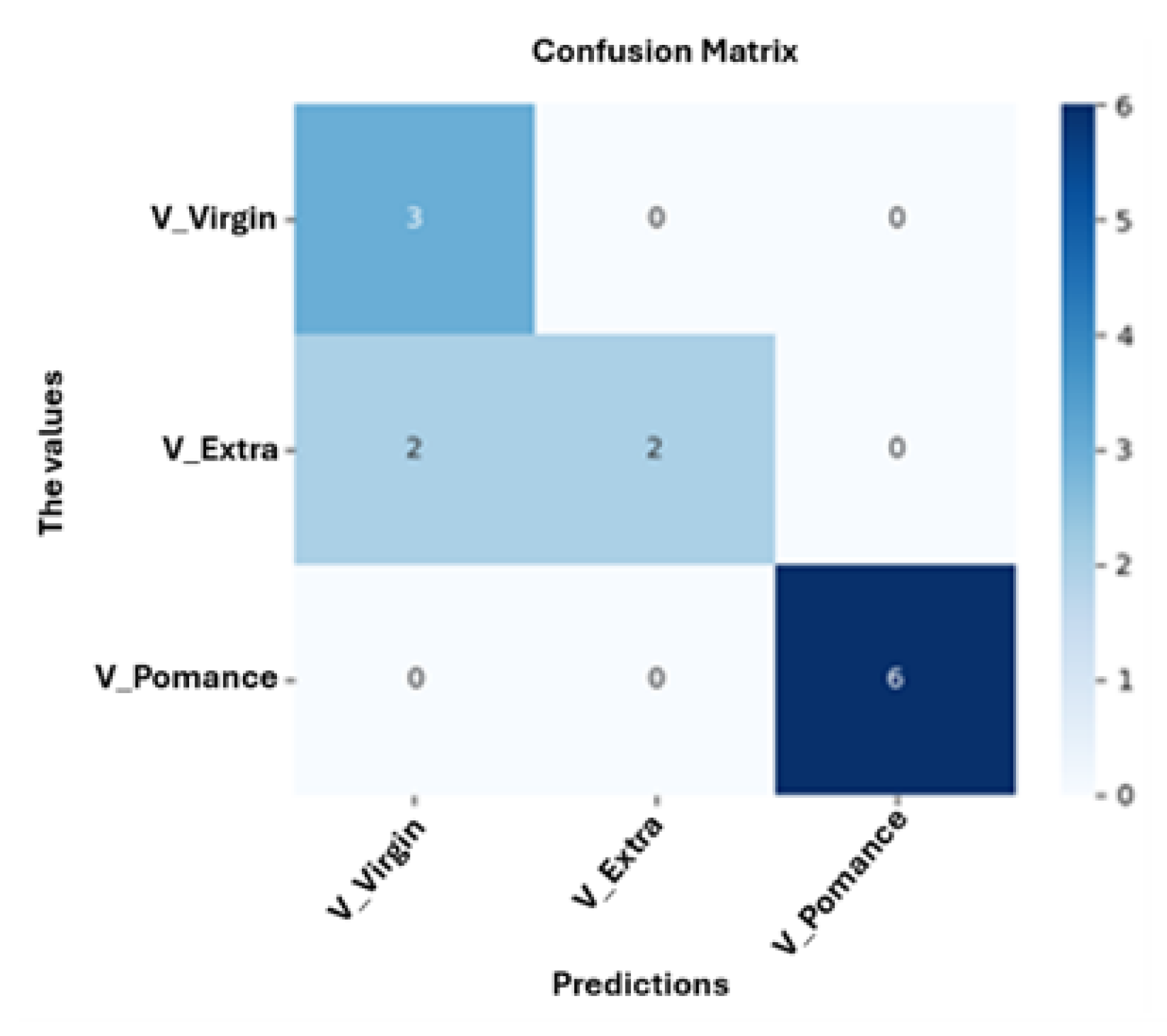

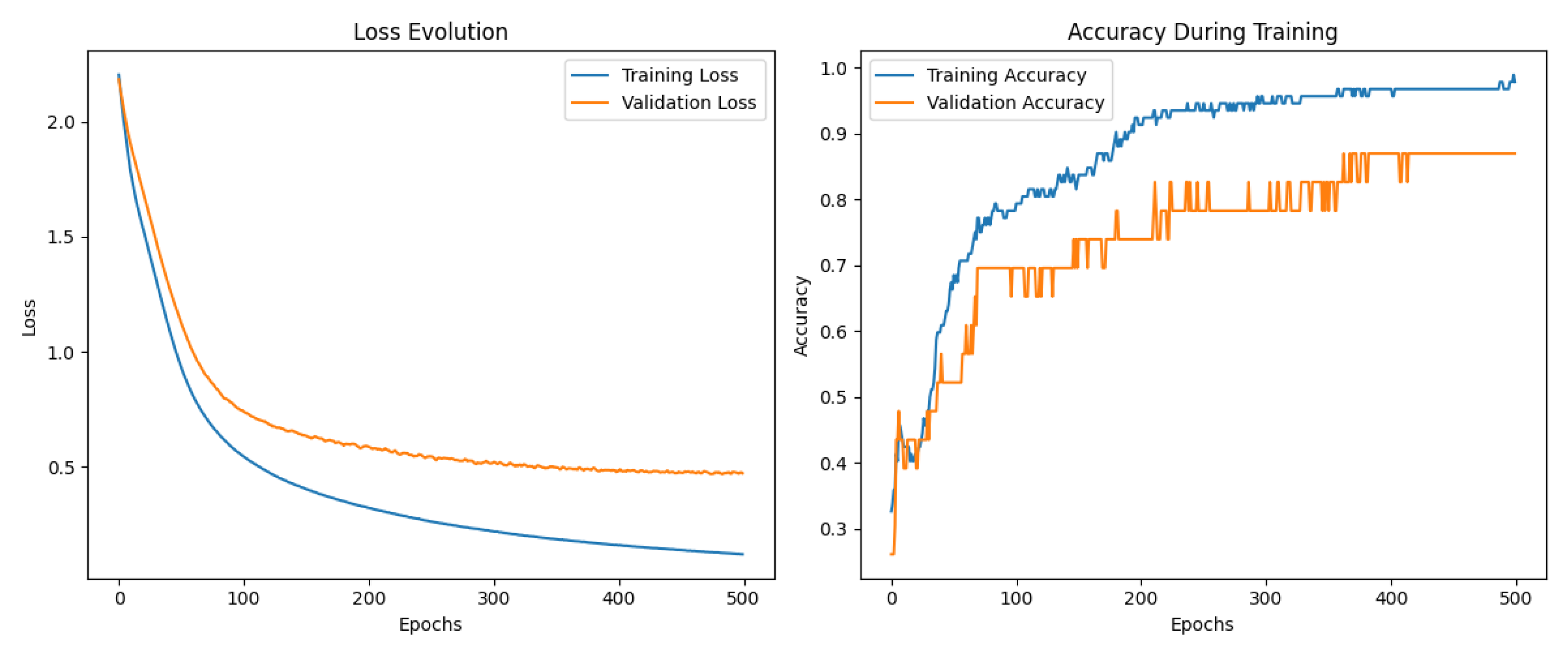

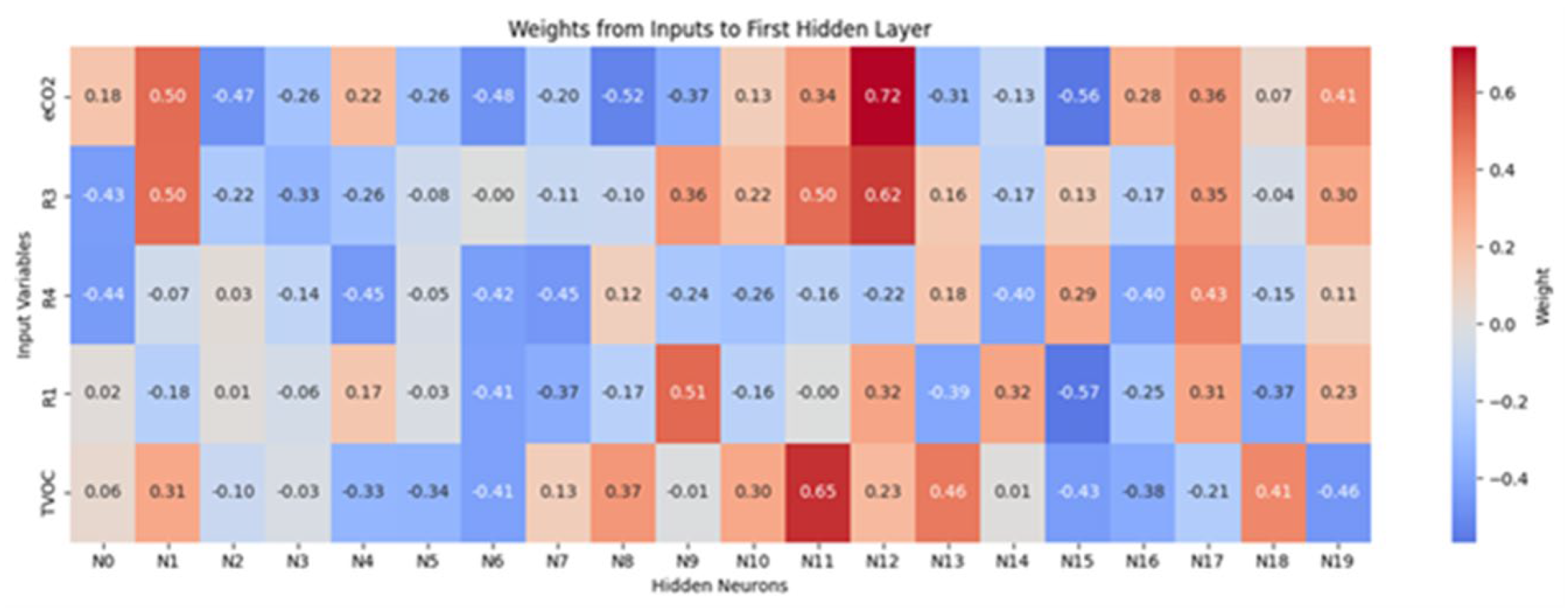

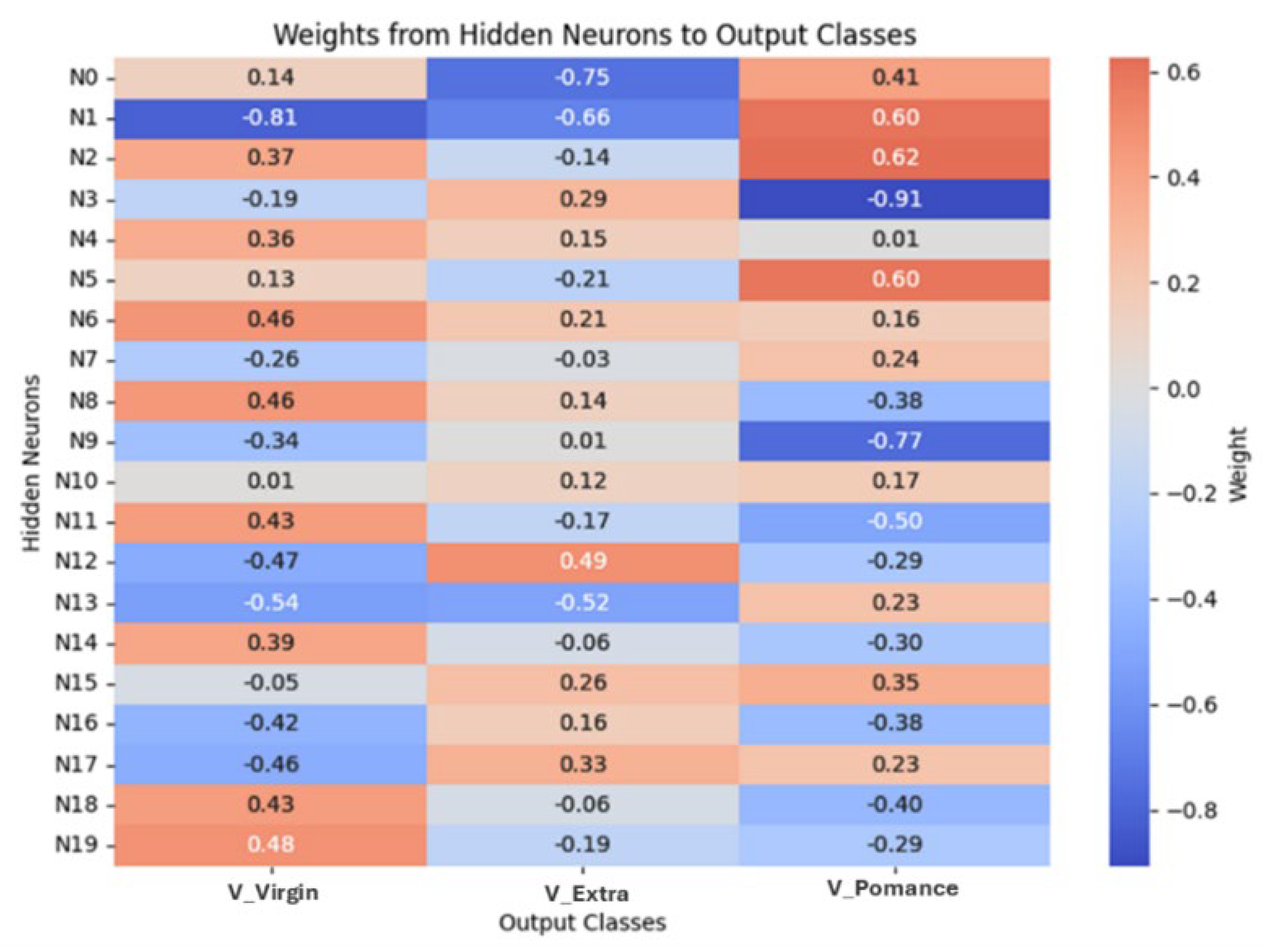

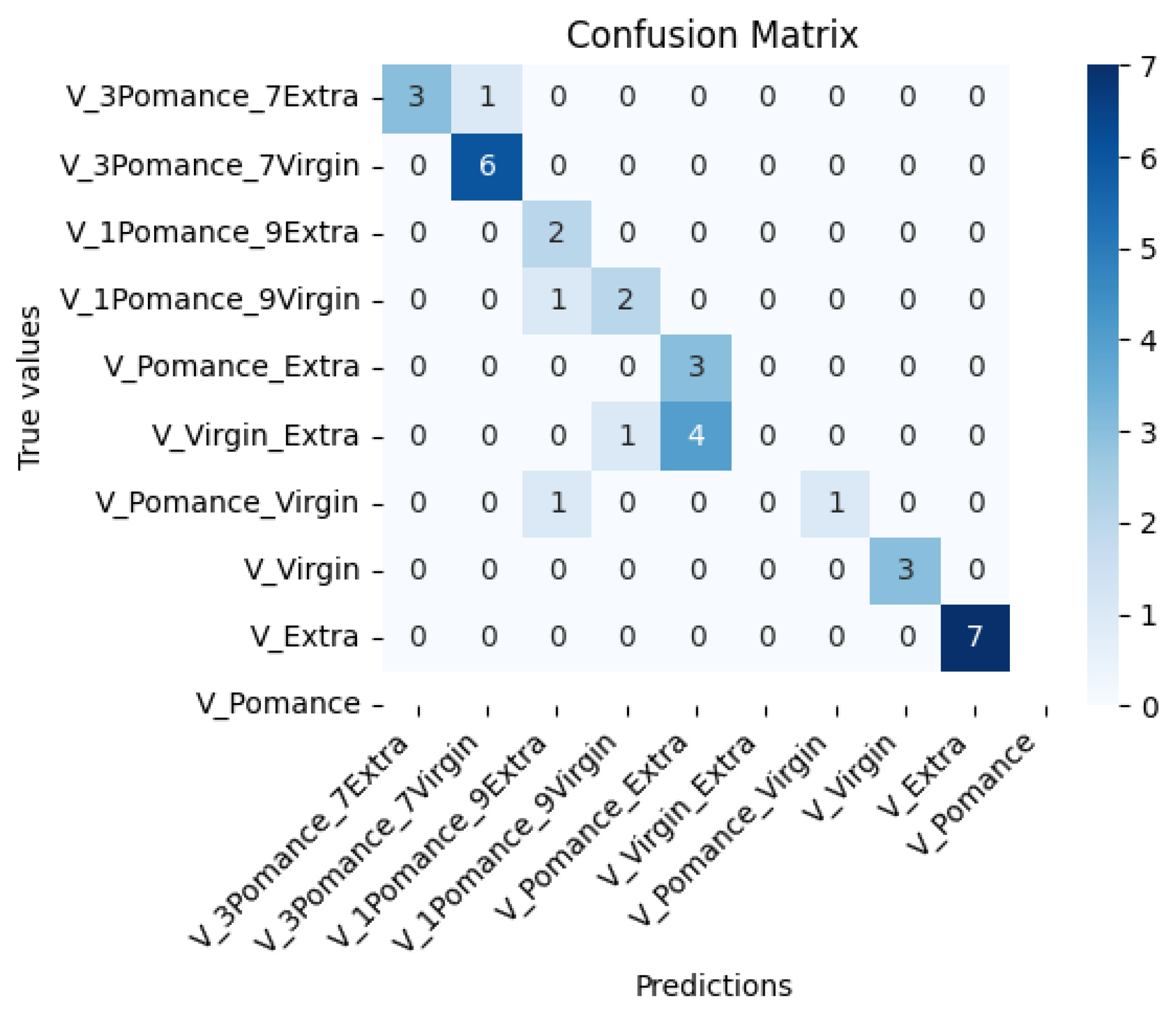

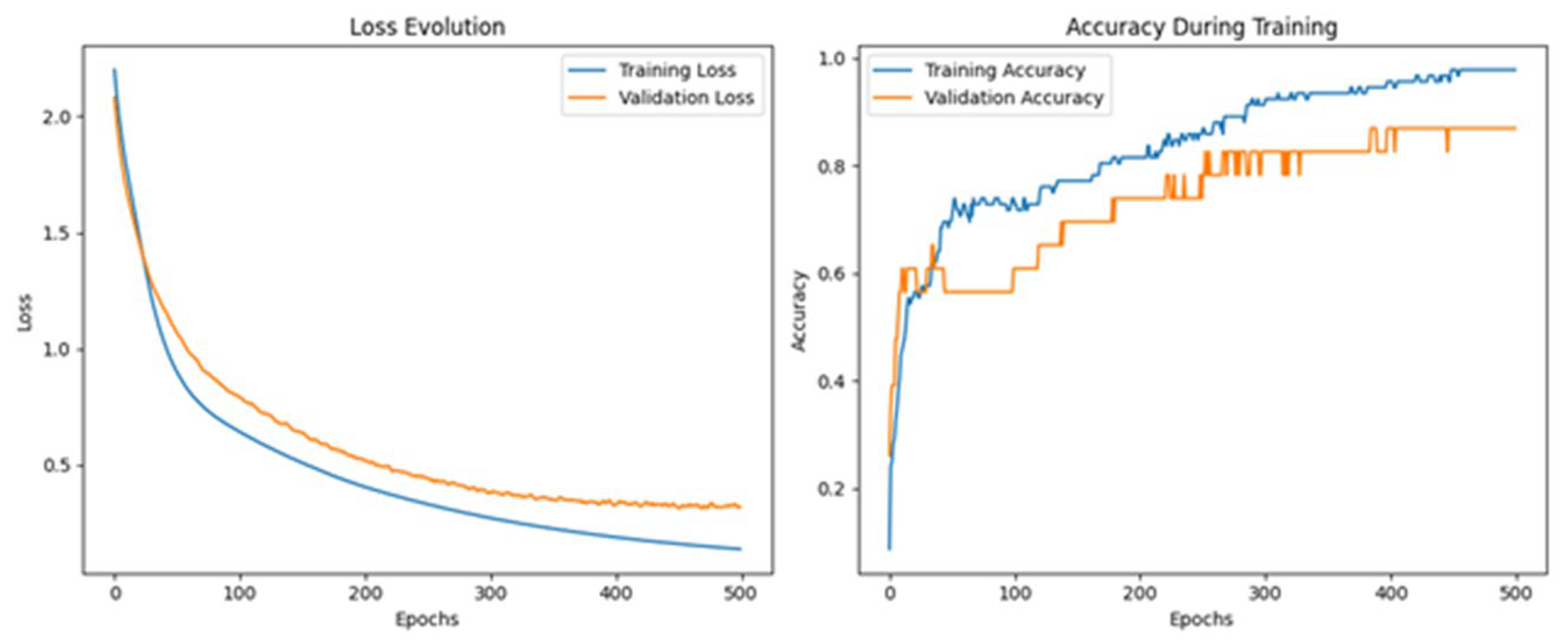

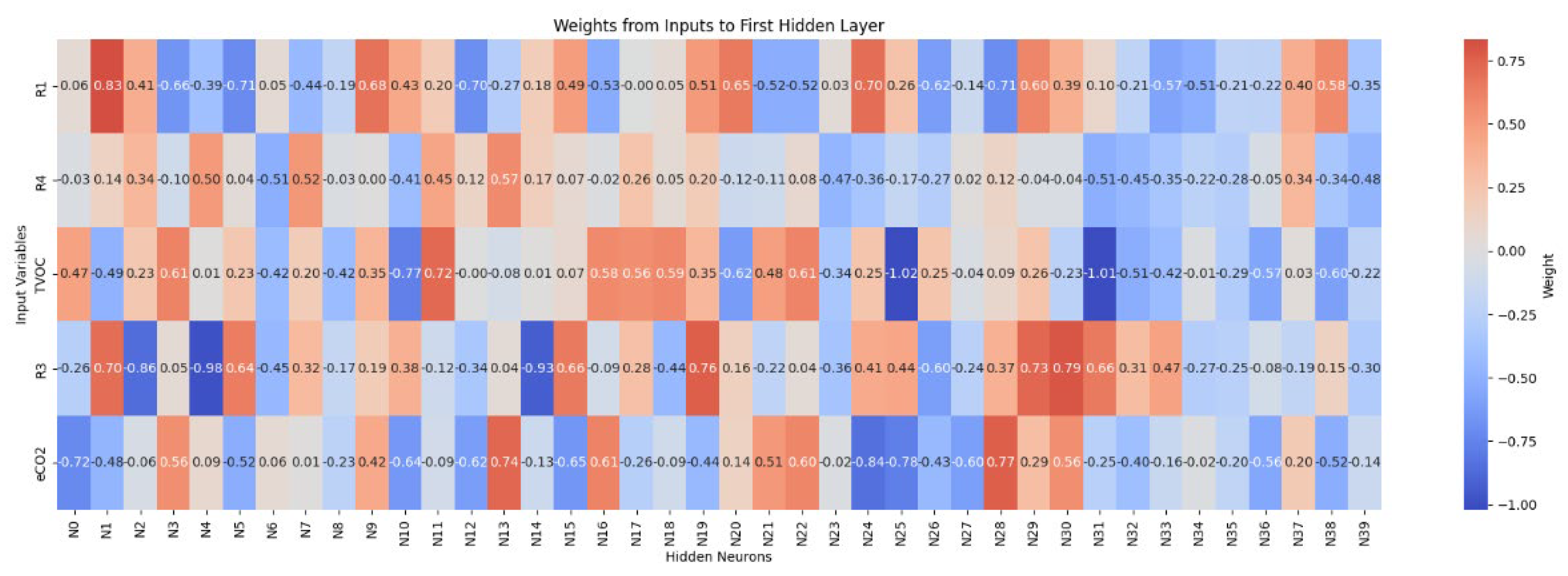

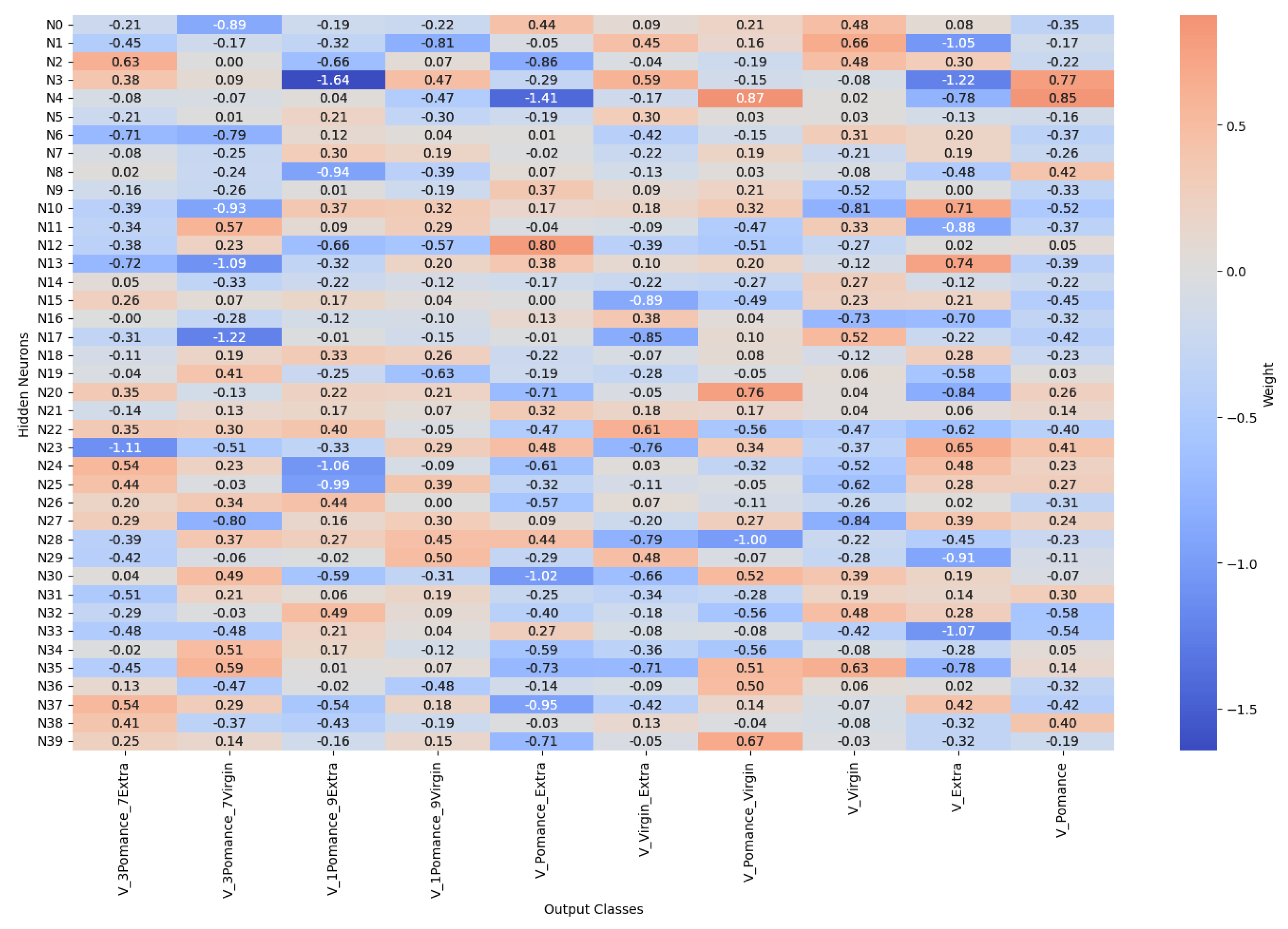

3.4. Multilayer Perceptron Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borzì, A.M.; Biondi, A.; Basile, F.; Luca, S.; Vicari, E.S.D.; Vacante, M. Olive oil effects on colorectal cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Crespo, M.C.; López de Las Hazas, M.C.; Visioli, F.; Dávalos, A. Olive oil consumption and its repercussions on lipid metabolism. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 952–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Lopez-Moreno, J.; Gomez-Delgado, F.; Lopez-Miranda, J. Extra virgin olive oil: More than a healthy fat. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 72 (Suppl 1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, C.; Papageorgiou, L.; Papakonstantinou, E.; Hagidimitriou, M.; Vlachakis, D. Olive oil polyphenols in neurodegenerative pathologies. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1195, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, C.; Mendes, L. Protected designation of origin (PDO), protected geographical indication (PGI) and traditional speciality guaranteed (TSG): A bibliometric analysis. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapoulouzi, M.; Agriopoulou, S.; Koidis, A.; Proestos, C.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Varzakas, T. Recent advances in analytical methods for the detection of olive oil oxidation status during storage along with chemometrics, authenticity and fraud studies. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, M.R.; Aboonajmi, M.; Ghasemi Varnamkhasti, M. Fraud detection and quality assessment of olive oil using ultrasound. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, R.; Mascini, M.; Faberi, A.; Sergi, M.; Compagnone, D.; Di Martino, V.; Carradori, S.; Pittia, P. Comparison of IRMS, GC-MS and E-nose data for the discrimination of saffron samples with different origin, process and age. Molecules 2019, 24, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowska, A.; Wąsowicz, E.; Jeleń, H.H. Differentiation of wines according to grape variety and geographical origin based on volatiles profiling using SPME-MS and SPME-GC/MS methods. Food Chem. 2016, 213, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmo-García, L.; Polari, J.J.; Li, X.; Bajoub, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Wang, S.C.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Study of the minor fraction of virgin olive oil by a multi-class GC-MS approach: Comprehensive quantitative characterization and varietal discrimination potential. Food Res. Int. 2019, 125, 108649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, D.L.; Morales, M.T.; Aparicio, R. Olive and olive oil. In Handbook of Olive Oil: Analysis and Properties; Hui, Y.H., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Chapter 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, C.; Portolés, T.; Johnsen, L.G.; Danielsen, M.; Beltran, J. Classification of olive oil quality and organoleptic attributes by untargeted GC-MS and multivariate statistical analysis. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; García-González, D.L.; Morales, M.T.; Lobo-Prieto, A.; Romero, I. Comparison of two validated analytical methods for the determination of volatile compounds in extra virgin olive oil: GC-FID vs. GC-MS. Talanta 2018, 187, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeta, E.; Núñez-Carmona, E.; Sberveglieri, V. A review: Applications of MOX sensors from air quality monitoring to biomedical diagnosis and agro-food quality control. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeta, E.; de Chiara, M.L.V.; Cefola, M.; Caruso, I.; Genzardi, D.; Núñez-Carmona, E.; Pace, B.; Palumbo, M.; Sberveglieri, V. Quality monitoring of table grapes stored in controlled atmosphere using an S3+ MOS nanosensor device. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 227, 113587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbatangelo, M.; Núñez-Carmona, E.; Duina, G.; Sberveglieri, V. Multidisciplinary approach to characterizing the fingerprint of Italian EVOO. Molecules 2019, 24, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, R.; Núñez-Carmona, E.; Genzardi, D.; Pandolfi, S.; Sberveglieri, V.; Mousavi, S. Volatile olfactory profiles of Umbrian extra virgin olive oils and their discrimination through MOX chemical sensors. Sensors 2022, 22, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritsakis, A.; Markakis, P. Olive oil: A review. Adv. Food Res. 1988, 31, 453–482. [Google Scholar]

- Bulatović, S.; Ilić, M.; Šolević Knudsen, T.; Milić, J.; Pucarević, M.; Jovančićević, B.; Vrvić, M.M. Evaluation of potential human health risks from exposure to volatile organic compounds in contaminated urban groundwater in the Sava River aquifer, Belgrade, Serbia. Environ. Geochem. Health 2022, 44, 3451–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, P.; Neumann, H.; Jackstell, R.; Beller, M. Industrially applied and relevant transformations of 1,3-butadiene using homogeneous catalysts. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2023, 1, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; He, J.; Lemonidou, A.A.; Li, X.; Lercher, J.A. Aqueous-phase hydrodeoxygenation of bio-derived phenols to cycloalkanes. J. Catal. 2011, 280, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nonane—Compound summary. PubChem Compound. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/nonane.

- Cilia, G.; Flaminio, S.; Quaranta, M. A novel and non-invasive method for DNA extraction from dry bee specimens. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, K.; Salavastru, C.; Eren, S.; et al. Einfluss von Diabetes auf ästhetische Eingriffe. Dermatologie 2025, 76, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, H.; Eggersdorfer, M. Ketones. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.; Astudillo, C.A.; Fernández-Palacios, E.; Cataldo, F.; Tenreiro, C.; Gabriel, D. Evolution of physico-chemical parameters, microbial diversity and VOC emissions of olive oil mill waste exposed to ambient conditions in open reservoirs. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Good Scents Company. Flavor and fragrance information catalog. The Good Scents Company Database 2009. Available online: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com/data/rw1042361.html.

- Cserháti, T.; Forgács, E. Flavor (flavour) compounds: Structures and characteristics. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 2509–2517. [Google Scholar]

- Üçüncüoğlu, D.; Sivri-Özay, D. Geographical origin impact on volatile composition and some quality parameters of virgin olive oils extracted from the “Ayvalık” variety. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hua, L.; Fu, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Xu, G.; Ni, Q.; Zhang, Y. Rapid identification of adulteration in extra virgin olive oil via dynamic headspace sampling and high-pressure photoionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6775–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, L.; Binello, A.; Cravotto, G. Efficient capture of cannabis terpenes in olive oil during microwave-assisted cannabinoid decarboxylation. Molecules 2024, 29, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorption of ethyl butyrate and octanal constituents of orange essence by polymeric adsorbents. [da verificare: mancano autori, testata, anno e pagine].

- Ziqiang, C.; Mingtao, M.; Xingguang, C.; Zhengcong, P.; Hua, L.; Jian, L.; Dianhui, W. Characterization of volatile compound differences of Shaoxing Huangjiu aged for different years using GC-E-nose, GC–MS, and GC-IMS. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Good Scents Company. Ethyl isovalerate. The Good Scents Company Database. Available online: http://www.thegoodscentscompany.com.

- Gokbulut, I.; Karabulut, I. SPME–GC–MS detection of volatile compounds in apricot varieties. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-R.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, K.-S. Volatile flavor components in Bogyojosaeng and Suhong cultivars of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch.). Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2000, 5, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Boch, R.; Shearer, D.A.; Stone, B.C. Identification of isoamyl acetate as an active component in the sting pheromone of the honey bee. Nature 1962, 195, 1018–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, A.V.; Singh, P.K.; Krishnan, N.; et al. Characterization of phytoconstituents of vital herbal oils by GC–MS and LC–MS/MS and their bioactivities. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhu, L.; Shang, H.; Xuan, X.; Lin, X. Effects of combined ε-polylysine and high hydrostatic pressure treatment on microbial qualities, physicochemical properties, taste, and volatile flavor profile of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 3610–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoz, E.; Paraster, H.; Moazeni, R. Analysis of olive fruit essential oil: Application of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry combined with chemometrics. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdock, G.A. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients, 5th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; ISBN 0-8493-3034-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, M.; Ota, Y.; Ito, M. Diversity in principal constituents of plants with a lemony scent and the predominance of citral. J. Nat. Med. 2022, 76, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Davies, N.; Corkrey, R.; Wilson, A.J.; Mathews, A.M.; Westmore, G.C. ROC curve analysis links volatile organic compounds in potato foliage to thrips preference, cultivar and plant age. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, T.D.; Dai, D.O.; Hoi, T.M.; Ogunwande, I.A. Essential oils from five species of Annonaceae from Vietnam. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1934578X1300800228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissermel, K.; Arpe, H.-J.; Lindley, C.R. Industrial Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003; pp. 341–344. ISBN 3-527-30578-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, E.; Ledbetter, C.A. Comparative study of the aromatic profiles of two different plum species: Prunus salicina Lindl. and Prunus simonii L. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1994, 65, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlpaintner, C.; Schulte, M.; Falbe, J.; Lappe, P.; Weber, J. Aldehydes, aliphatic. In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.L.; Ito, Y.; Yamasaki, M. Response of the oak ambrosia beetle Platypus quercivorus (Coleoptera: Platypodinae) to volatiles from fresh and dried leaves. Arthropod-Plant Interact. 2025, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, T.; Monsempès, C.; Demondion, E.; Chatterjee, A.; Kostal, L.; Lucas, P. Stimulus duration encoding occurs early in the moth olfactory pathway. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one. PubChem. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one.

- Dourou, A.M.; Brizzolara, S.; Famiani, F.; Tonutti, P. Changes in volatile organic composition of olive oil extracted from cv. 'Leccino' fruit subjected to ethylene treatments at different ripening stages. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3981–3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, J.F.; Mainland, J.D.; Jaeger, S.R.; Adipietro, K.A.; Matsunami, H.; Newcomb, R.D. Genetic variation in the odorant receptor OR2J3 is associated with the ability to detect the “grassy” smelling odor, cis-3-hexen-1-ol. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adiani, V.; Ambolikar, R.; Gupta, S. Utilization of gamma irradiation for development of shelf-stable mint coriander sauce. Food Meas. 2025, 19, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUPAC. Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book); The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2014; p. 745. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymer, R.; Jessa, S.M.; Cooper, W.J.; Olson, M.B. The effects of diatom polyunsaturated aldehydes on embryonic and larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicology 2025, 34, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hieu, L.D.; et al. Chemical composition of essential oils from four Vietnamese species of Piper (Piperaceae). J. Oleo Sci. 2014, 63, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-Y.; Zhao, P.; Cheng, X.-L.; Xiu, Z.-L. Enhanced production of 2,3-butanediol from sugarcane molasses. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 175, 3014–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, D.R. Organic Chemistry Demystified; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 359. ISBN 0-07-148710-7. [Google Scholar]

- De Conti, A.; Tryndyak, V.; Koturbash, I.; Heidor, R.; Kuroiwa-Trzmielina, J.; Ong, T.P.; Beland, F.A.; Moreno, F.S.; Pogribny, I.P. The chemopreventive activity of the butyric acid prodrug tributyrin in experimental rat hepatocarcinogenesis is associated with p53 acetylation and activation of the p53 apoptotic signaling pathway. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W. Floral scents and fruit aromas: Functions, compositions, biosynthesis, and regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 860157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. Soapy taste of coriander linked to genetic variants. Nature 2012, 486, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Clark, R.E.; Fu, Z.; Lee, B.W.; Crowder, D.W. Insect alarm pheromones in response to predators: Ecological trade-offs and molecular mechanisms. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 128, 103514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Pan, X.; Shi, J.; Ye, H.; Guan, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, J.-J. Formation of urocanic acid versus histamine from histidine in chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus) fillets as determined by a mixed-mode HPLC method. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 142, 107431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Bai, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Meng, R.; Guo, N. Inhibitory effect of non-Saccharomyces Starmerella bacillaris CC-PT4 isolated from grape on MRSA growth and biofilm. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2025, 17, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, M.; Awad, M.A.; Shadidizaji, A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.A.; Warda, M. In vivo and in silico insights into the antidiabetic efficacy of EVOO and hydroxytyrosol in a rat model. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 135, 109775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprea, E.; Gasperi, F.; Betta, E.; Sani, G.; Cantini, C. Variability in volatile compounds from lipoxygenase pathway in extra virgin olive oils from Tuscan olive germplasm by quantitative SPME/GC-MS. J. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 53, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procida, G.; Cichelli, A.; Lagazio, C.; Conte, L.S. Relationships between volatile compounds and sensory characteristics in virgin olive oil by analytical and chemometric approaches. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboredo-Rodríguez, P.; González-Barreiro, C.; Cancho-Grande, B.; Simal-Gándara, J. Aroma biogenesis and distribution between olive pulps and seeds with identification of aroma trends among cultivars. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vico, L.; Belaj, A.; Sánchez-Ortiz, A.; Martínez-Rivas, J.M.; Pérez, A.G.; Sanz, C. Volatile compound profiling by HS-SPME/GC-MS-FID of a core olive cultivar collection as a tool for aroma improvement of virgin olive oil. Molecules 2017, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Pietro, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive compounds and quality of extra virgin olive oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Chamorro, F.; Pereira, A.G.; Carrera-Casais, A.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Carpena, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Evolution of flavors in extra virgin olive oil shelf-life. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Replicate (R) | Techniques | Sample Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVOO (20mL for GC-MS); EVVO (50mL for e-nose) | |||

| R1 | GC-MS SPME; | 1 | |

| e-nose | |||

| EVOO (20mL for GC-MS); EVVO (50mL for e-nose) | R2 | GC-MS SPME; | 2 |

| e-nose | |||

| EVOO (20mL for GC-MS); EVVO (50mL for e-nose) | R3 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

3 |

| POO (50mL) | R1 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

4 |

| POO (50mL) | R2 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

5 |

| POO (50mL) | R3 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

6 |

| OO (50mL) | R1 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

7 |

| OO (50mL) | R2 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

8 |

| OO (50mL) | R3 | GC-MS SPME; e-nose |

9 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) POO | R1 | e-nose | 10 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) POO | R2 | e-nose | 11 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) POO | R3 | e-nose | 12 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) OO | R1 | e-nose | 13 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) OO | R2 | e-nose | 14 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) EVOO + (50 mL) OO | R3 | e-nose | 15 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) POO + (50 mL) OO | R1 | e-nose | 16 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) POO + (50 mL) OO | R2 | e-nose | 17 |

| 50% adulteration: (50mL) POO + (50 mL) OO | R3 | e-nose | 18 |

| 30% adulteration: (70mL) EVOO + (30 mL) OO | R1 | e-nose | 19 |

| 30% adulteration: (70mL) EVOO + (30 mL) OO | R2 | e-nose | 20 |

| 30% adulteration: (70mL) EVOO + (30 mL) OO | R3 | e-nose | 21 |

| 30% adulteration: (30mL) POO + (70 mL) OO | R1 | e-nose | 22 |

| 30% adulteration: (30mL) POO + (70 mL) OO | R2 | e-nose | 23 |

| 30% adulteration: (30mL) POO + (70 mL) OO | R3 | e-nose | 24 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) EVVOO | R1 | e-nose | 25 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) EVVOO | R2 | e-nose | 26 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) EVVOO | R3 | e-nose | 27 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) OO | R1 | e-nose | 28 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) OO | R2 | e-nose | 29 |

| 10% adulteration: (10mL) POO + (90 mL) OO | R3 | e-nose | 30 |

| Sensor | Manufacturer | Type | Signal Measured |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHT40 | Sensirion | Temperature/ Humidity |

Temperature (°C), Relative humidity (%) |

| ENS160 | Sensirion | MOX | Eco2 (ppm), TVOCs (ppm), Air quality Index (AQI), Four resistive elements (Ohms) |

| STC31-R3 | Sensirion | CO2 sensor | CO2 (% vol) |

| data | data | data |

| OO | EVOO | POO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code: 25-L-CR051 |

Code: 25-L-CR052 |

Code: 25-L-CR050 |

||||

| RT | Volatile compounds | CAS | Absolute area | Absolute area | Absolute area | Description |

| 5,76 | Heptane | 142-82-5 | nd* | nd | 9,66E+05 | Linear saturated hydrocarbon composed of a straight chain of seven carbon atoms fully saturated with hydrogen [19]. |

| 7,82 | n-Octane | 111-65-9 | 1,50E+07 | 1,61E+07 | 2,75E+06 | Single chain of eight carbon atoms bonded to eighteen hydrogen atoms [19]. |

| 8,52 | Cyclohexane, 1,3-dimethyl-, cis- | 638-04-0 | nd | nd | 1,26E+06 | Chemical compound; six-carbon cycloalkane with methyl groups at positions 1 and 3. Exists as two geometric isomers: cis and trans [20]. |

| 9,52 | Octene | 111-66-0 | 1,11E+06 | 1,22E+06 | nd | Linear alpha-olefin with double bond at position 1. Industrially produced from ethylene; used as comonomer in polyethylene and in hydroformylation to produce linear aldehydes [21]. |

| 11,83 | Ethylcyclohexane | 1678-91-7 | nd | nd | 1,20E+06 | Saturated hydrocarbon: ethyl group bound to a cyclohexane ring. Found in petroleum as a naphthene; produced by hydrogenation of ethylbenzene or hydrodeoxygenation of lignin [22]. |

| 12,20 | n-Nonane | 111-84-2 | nd | nd | 2,50E+05 | Straight-chain alkane; colorless liquid with sharp odor. Volatile oil component and plant metabolite; insoluble in water. Found in various plant species [23]. |

| 12,34 | Acetic acid, ethyl ester , Ethyl acetate | 141-78-6 | 8,59E+06 | 2,51E+06 | 3,90E+05 | Sweet-smelling, colorless, flammable ester of ethanol and acetic acid. Widely used as a solvent in paints, nail polish, decaffeination, perfumes, and wine; also used for insect collection [24]. |

| 12,82 | Acetic acid, hydroxy- (Glycolic acid) | 79-14-1 | 1,41E+07 | 1,52E+07 | 1,27E+07 | Functions as a metabolite and keratolytic agent. Used in cosmetics and dermatology; safe up to 10% (pH ≥ 3.5) in consumer products [25]. |

| 13,79 | Pentanal | 110-62-3 | 9,87E+05 | 1,06E+06 | nd | Alkyl aldehyde; colorless volatile liquid with fruity, nutty odor. Produced via hydroformylation of butene; used in fragrance synthesis and as intermediate for plasticizers [26]. |

| 14,07 | butanal, 3-methyl | 590-86-3 | 8,20E+05 | 9,58E+05 | nd | Branched aldehyde with a methyl group at position 3; volatile compound found in olives. Acts as flavoring agent, plant metabolite, and product of yeast metabolism [27]. |

| 15,70 | Hexane, 1-methoxy- (Hexyl methyl ether) | 4747-07-3 | 1,57E+07 | 1,76E+07 | nd | Colorless liquid with characteristic odor. Contains a methyl group bonded to a hexane chain via oxygen; primarily used as a solvent [25]. |

| 16,70 | 3-buten-1-ol | 627-27-0 | 8,32E+05 | 1,27E+06 | nd | Organic compound belonging to the class of unsaturated alcohols. In the food sector, it can be detected as a volatile compound in certain vegetable oils [25]. |

| 17,85 | 3-pentanone | 96-22-0 | 3,56E+06 | 1,89E+06 | nd | Also known as diethyl ketone, is a simple symmetrical dialkyl ketone, with an odor like that of acetone [28]. |

| 17,95 | 3-methylbutanal | 590-86-3 | 1,03E+06 | 8,49E+05 | nd | Aldehyde, a colorless liquid and found in low concentrations in many types of food. Commercially it is used as a reagent to produce pharmaceuticals, perfumes and pesticides [29]. |

| 18,28 | Decane | 124-18-5 | 3,28E+06 | 3,06E+06 | 1,60E+06 | Linear molecule of 10 carbons with a non-define scent found in olive oil [30]. |

| 19,31 | 3-Ethyl-1,5-octadiene (c,t) | 105-54-4 | 3,72E+06 | 6,72E+06 | nd | 3-ethyl-1,5-octadiene is an alkadiene that is 1,5-octadiene substituted by an ethyl group at position 3. Has a non-define scent [3]. |

| 19,55 | Methyl 3(Z)-Hexenyl Ether | 70220-06-3 | 8,87E+06 | 7,83E+06 | nd | Fragrance and flavoring agent with green, fruity, slightly floral scent; methyl ether of (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol; used in flavors, fragrances, and potentially in coatings [31]. |

| 20,18 | alfa-pinene | 80-56-0 | 4,41E+05 | nd | nd | Bicyclic monoterpene, a volatile organic compound commonly found in essential oils from conifers and various aromatic plants. It exhibits anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and bronchodilator properties, making it useful in traditional and pharmaceutical applications [32]. |

| 21,48 | Ethyl Butanoate | 105-54-4 | 1,03E+06 | 3,34E+05 | nd | It is soluble in propylene glycol, paraffin oil, and kerosene. It has a fruity odor and is a key ingredient used as a flavor enhancer in processed orange juices. It also occurs naturally in many fruits, albeit at lower concentrations [33]. |

| 22,42 | Butanoic acid, 2-methyl-, ethyl ester | 7452-79-1 | 1,73E+06 | 3,44E+05 | nd | Also known as ethyl 2-methylbutyrate. It is a fruity-scented volatile ester, used as a flavoring agent and naturally found in wines, strawberries, blueberries, apples and olive [34]. |

| 23,43 | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, ethyl ester | 108-64-5 | 4,33E+05 | nd | nd | It has a fruity odor and flavor and is used in perfumery and as a food additive [35]. |

| 24,44 | Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 8,60E+06 | 1,12E+07 | 2,11E+06 | Also called hexanaldehyde or caproaldehyde, it is an alkyl aldehyde. Its scent resembles freshly cut grass, with a powerful, penetrating characteristic fruity odor and taste. It occurs naturally and contributes to the flavor in green peas [36]. |

| 24,65 | 1-Propanol, 2-methyl- | 78-83-1 | 2,21E+06 | 1,31E+06 | nd | Also called isobutanol. It’s produced by the carbonylation of propylene. Has ethereal, winey and cortex notes [37]. |

| 26,74 | Isoamyl acetate | 123-92-2 | 2,87E+06 | 1,10E+06 | nd | Colorless liquid, slightly soluble in water, highly soluble in organic solvents. Strong banana-like odor; used as food flavoring. Naturally from bananas or synthetically produced; also, a bee alarm pheromone [38]. |

| 27,20 | methyl laureate | 111-82-0 | 5,01E+05 | 5,61E+05 | nd | Fatty acid methyl ester of lauric acid; occurs in olive, fruits (e.g., grape, melon, pineapple), cheeses, wines, and spirits. Used as a flavoring agent; classified as a fatty acid ester [39]. |

| 27,44 | 2-pentenal | 623-36-9 | 6,24E+05 | 6,81E+05 | nd | Aldehyde found in cigarette smoke, virgin olive oil, and milk. It has a role as a plant metabolite [40]. |

| 28,72 | 1-Penten-3-ol | 616-25-1 | 1,66E+06 | 1,80E+06 | nd | Alcohol with pungent horseradish-like odor and tropical notes when diluted; used to enhance green, cucumber, melon, berry, and vegetable accords in fragrances [40]. |

| 30,33 | Dodecane | 112-40-3 | 3,50E+06 | 2,26E+06 | 1,29E+06 | Linear branched molecule consisting of decane with 12 carbon atoms. It is a clear colorless liquid isolated from the essential oils of various plants including Zingiber officinale (ginger). It has a role as a plant metabolite is a natural product found in Erucaria microcarpa, with a balsamic scent found in olive oil [41]. |

| 30,50 | Heptanal | 111-71-7 | 1,28E+06 | 1,67E+06 | 3,60E+05 | Aliphatic aldehyde; colorless liquid with strong fruity odor. Naturally found in ylang-ylang, clary sage, lemon, bitter orange oils, and in olives at low levels [42]. |

| 31,18 | Limonene | 138-86-3 | 8,53E+05 | 9,85E+05 | 7,20E+05 | Limonene is a volatile hydrocarbon, a cycloolefin classified as a cyclic monoterpene, lemon-like odor that can be found in the rind of citrus fruits [43]. |

| 31,34 | Isoamyl alcohol | 123-51-3 | 1,12E+07 | 3,88E+06 | nd | Isomeric alcohol: natural ester used in banana oil and as flavoring, also present in black truffle aroma. By-product of cereal fermentation, found in alcoholic beverages; component of hornet alarm pheromone [44]. |

| 32,55 | 2-hexenal | 505-57-7 | 4,98E+07 | 3,06E+07 | nd | 2-Hexenal is a chemical compound of the aldehyde group. Imparts fresh, green, and natural top note in fruity floral types. Apple, berry, and other fruit flavors. Also, citrus flavors, especially orange juice [41]. |

| 32,65 | 3,5-dimethyl-4-aza-4-heptene | 38836-40-7 | 8,56E+07 | 1,32E+08 | nd | Heterocyclic compound containing a nitrogen atom as part of a seven-membered ring, with two methyl groups attached to the carbon atoms at positions 3 and 5, and an ethyl group and a methyl group attached to the carbon at position 4 [44]. |

| 33,65 | 1-Pentanol | 71-41-0 | 7,32E+05 | 2,58E+05 | nd | It’s an alcohol with five carbon atoms. Pungent, fermented, bready, yeasty, fusel, winey and solvent-like smell [41]. |

| 33,94 | Trans-β-Ocimene | 3779-61-1 | 6,83E+06 | 7,88E+06 | nd | β-Ocimene is trans-3,7-dimethyl-1,3,6-octatriene. Exists in two stereoisomeric forms, cis and trans, with respect to the central double bond. The ocimenes are often found naturally as mixtures of the various forms. Complex note, mainly herbal lavender with green citrus, metallic and mango nuances [45]. |

| 34,69 | Styrene (Ethenylbenzene) | 100-42-5 | 2,11E+06 | 4,40E+05 | nd | Aromatic hydrocarbon. The vinyl group attached to the aromatic ring is highly reactive, as the ring can delocalize charges and unpaired electrons to the ortho and para positions through various resonance forms [46]. |

| 35,04 | n-hexyl acetate | 142-92-7 | 1,15E+07 | 1,32E+07 | nd | Hexyl acetate is the acetate ester of hexan-1-ol. Green fruity note reminiscent of apple, pear [47]. |

| 36,11 | Octanal | 124-13-0 | 9,11E+05 | 1,11E+06 | nd | Colorless fragrant liquid with fruity odor; naturally in citrus and olive oils. Used in perfumes and as a flavoring in food industry [48]. |

| 36,21 | 3-hydroxy-2-butanone | 513-86-0 | 2,05E+06 | 8,07E+05 | nd | Chemical used in food flavoring and fragrances; intermediate in microbial butanediol cycle; also serves as an aroma carrier in flavors and essences [48]. |

| 36,74 | (E)-4,8-Dimethyl-1,3,7-nonatriene | 19945-61-0 | 5,27E+06 | 5,85E+06 | nd | Alkatriene consisting of 4,8-dimethylnonane having the three double bonds in the 1-, 3- and 7-positions [49]. |

| 37,41 | 3-Hexen-1-ol, acetate, (Z)- | 3681-71-8 | 9,39E+07 | 1,34E+08 | nd | Acetate ester from acetic acid and (Z)-hex-3-en-1-ol; metabolite with green, fruity aroma; found in tea, olive, and other plants [50]. |

| 38,13 | 2-Heptenal, (E)- | 18829-55-5 | 2,57E+06 | 2,83E+06 | nd | Monounsaturated fatty aldehyde with a green, fatty aroma; found mainly in pomelo peel, soybean oil, and pulses. Acts as a plant metabolite, food flavoring, and uremic toxin [19]. |

| 38,59 | 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 110-93-0 | 1,08E+06 | 1,09E+06 | nd | Unsaturated methylated ketone; colorless liquid with citrus, fruity odor. Found as a mosquito attractant [51]. |

| 38,85 | 1-Hexanol | 111-27-3 | 3,40E+07 | 2,91E+07 | nd | It’s an organic alcohol with a six-carbon chain. Smells pungent, etherial, fuel oil, fruity and alcoholic, sweet with a green top note [52]. |

| 40,55 | 3-Hexen-1-ol, (Z)- | 928-96-1 | 7,56E+07 | 8,07E+07 | nd | Colorless oily liquid with intense grassy-green odor; produced by most plants as insect attractant. Key aroma compound in flavors and perfumes; used in fruit and vegetable notes [53]. |

| 41,29 | Nonanal | 124-19-6 | 9,32E+06 | 1,37E+07 | 9,78E+05 | It’s a formally saturated fatty aldehyde resulting from the reduction of the carboxyl group of nonanoic acid. Waxy, rose and orange peel [41]. |

| 41,50 | 2-Hexen-1-ol, (E)- | 928-95-0 | 1,59E+07 | 8,83E+06 | nd | Primary allylic alcohol derived from 2-hexene; acts as a plant metabolite. Classified as an alkenyl and allylic alcohol [54]. |

| 43,75 | Acetic acid | 64-19-7 | 3,29E+07 | 6,51E+06 | 6,72E+05 | Colorless, acidic liquid; main component of vinegar. Widely used in food, chemical industry, and as acidity regulator. Central to metabolism (acetyl group) [55]. |

| 44,88 | trans,trans-2,4-heptadienal | 4313-03-5 | 1,40E+06 | 1,02E+06 | nd | Heptadienal with double bonds at positions 2 and 4 (E,E-isomer); used as a flavoring agent [56]. |

| 46,06 | .alpha.-Copaene | 3856-25-5 | 2,30E+06 | 1,68E+06 | nd | It’s an oily liquid hydrocarbon found in several plants that produce essential oils. Scents reminiscent of honey, spicy or woody notes [57]. |

| 47,59 | 2,3-Butanediol | 513-85-9 | 1,72E+06 | 8,12E+05 | nd | Organic compound; colorless vic-diol liquid. Occurs naturally in olive oil, cocoa butter, sweet corn, and rotten mussels. Used in plastics, pesticides, and GC carbonyl compound resolution [58]. |

| 47,73 | .alpha.-terpinolene | 586-62-9 | 7,31E+05 | 7,29E+05 | nd | Natural terpene found in lilac, sage, rosemary, nutmeg, conifers, olive, and tea tree oil. Colorless to pale yellow liquid with woody, citrus-like odor; slightly bitter at high concentrations [56]. |

| 47,93 | Benzaldehyde | 100-52-7 | 1,16E+06 | 1,05E+06 | 4,73E+05 | Aromatic aldehyde; colorless volatile liquid with characteristic bitter almond odor. Naturally occurs in apricot, cherry, and almond seeds (as amygdalin precursor) [59]. |

| 48,17 | n-Octanol | 111-87-5 | 1,75E+06 | 2,19E+06 | nd | Eight-carbon alcohol; colorless liquid with characteristic odor. Hydrophobic and water-immiscible; used to determine partition coefficients of chemicals [59]. |

| 51,32 | Butanoic acid | 107-92-6 | 1,06E+06 | 2,03E+05 | nd | Carboxylic acid found esterified in natural fats and released during fat rancidification (e.g., in butter, aged cheeses, olive). Has a pungent odor at high concentration; contributes to characteristic aroma of fermented dairy at low levels. Formed via butyric fermentation of sugars and used in the synthesis of flavor and fragrance esters [60]. |

| 51,99 | Benzoic acid, methyl ester | 93-58-3 | 1,32E+06 | 1,83E+06 | nd | Methyl ester of benzoic acid; colorless liquid with pleasant floral odor. Found naturally in some plants; used in perfumes and as a scent marker in canine training. Poorly soluble in water, well soluble in organic solvents [61]. |

| 52,48 | (E)-2-Decenal | 3913-81-3 | 2,90E+06 | 3,05E+06 | nd | Oily aldehyde with strong waxy odor; occurs in coriander, meats, fruits, and various foods. Used as flavoring agent and also acts as pheromone [62]. |

| 56,09 | Farnesene | 502-61-4 | 7,92E+06 | 1,04E+07 | nd | Group of sesquiterpene isomers, including α- and β-farnesene; differ by double bond position. Found in green apple peel, cannabis, ginger, hop, and other plants. Acts as an insect alarm pheromone (e.g., aphids) and contributes to fruity, woody, and citrus aromas [63]. |

| 58,32 | Benzoic acid, 2-hydroxy-, methyl ester | 119-36-8 | 1,50E+06 | 1,97E+06 | nd | Also known as methyl salicylate; colorless liquid with characteristic odor. Found in wintergreen oil; used in flavors, fragrances, and as a counterirritant in topical medications [64]. |

| 61,44 | Benzenemethanol | 100-51-6 | 1,22E+06 | 8,37E+05 | nd | Aromatic alcohol; clear, colorless liquid with pleasant odor. Used as solvent, antioxidant, fragrance, and chemical intermediate; may cause irritation on contact [65]. |

| 62,78 | phenylethyl alcohol | 60-12-8 | 4,50E+06 | 2,12E+06 | nd | Aromatic alcohol with rose-like scent; naturally found in rose, peppermint, hyacinth, and orange blossom. Used in perfumes, soaps, and as antimicrobial agent; slightly soluble in water [66]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).