1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major global public health concern (1). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), if no effective action is taken, AMR could become one of the leading causes of death by 2050, potentially causing up to 10 million deaths annually, with a particularly severe impact in sub-Saharan Africa (sSA) (2).

This global threat is exemplified by the rapid emergence of resistance to newly introduced antibiotics: for instance, following the introduction of third-generation cephalosporins in the late 1970s, the first Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) were detected in Germany (3–5).

Today, ESBL-producing bacteria are increasingly common, particularly among Enterobacterales such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) (5–7). The WHO classifies Salmonella isolates from blood as priority pathogens requiring global surveillance in the fight against AMR (1). NTS is a leading cause of invasive infections in sub-Saharan Africa, (7–10). In 2017, Stanaway et al. estimated that 535,000 (95% uncertainty interval 409,000–705,000) cases of invasive NTS occurred globally, with the highest incidence in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among children younger than 5 years old (34·3 [23·2–54·7] cases per 100,000 person-years) (11).

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the blood culture surveillance network has reported increasing resistance patterns among NTS isolates, particularly resistance to third-generation cephalosporins (12,13). This situation is of high concern as over 95% of empirical treatments for suspected bacteremia at Saint Luc Hospital (Kisantu Health Zone, one of the surveillance sites in DRC) rely on third-generation cephalosporins (14).

The present study aims to describe the prevalence, epidemiological characteristics, resistance profiles, and temporal dynamics of ESBL-producing NTS isolated from blood cultures collected at Saint Luc Hospital. This work addresses an existing research gap, as recent data on ESBL-producing NTS remain scarce, with most available studies dating back several years (15).

2. Results

2.1. Blood culture Outcomes and NTS isolation

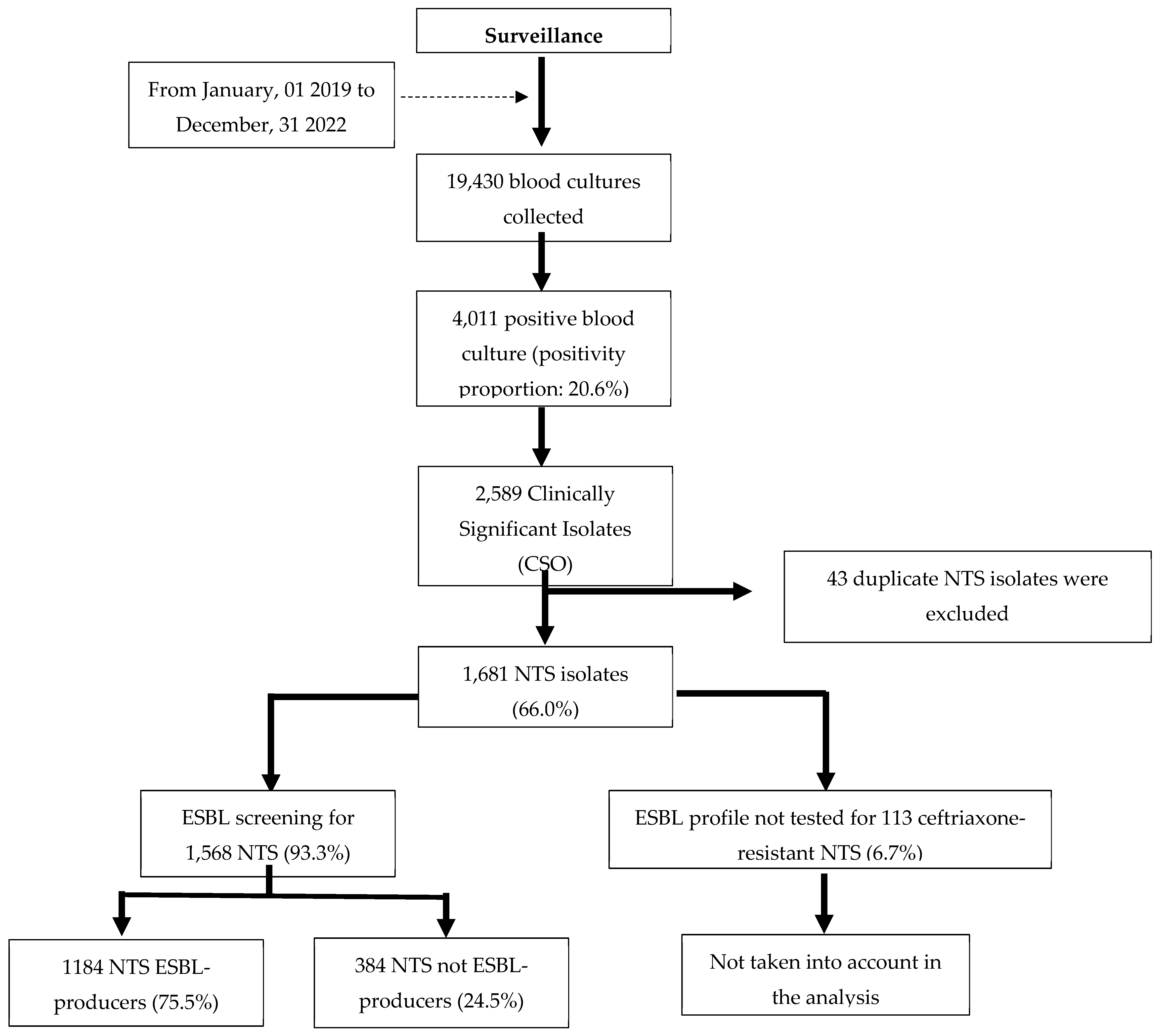

Figure 1.

Breakdown of blood culture results obtained at Saint Luc Hospital.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of blood culture results obtained at Saint Luc Hospital.

Between January 2019 and December 2022, a total of 19,430 blood cultures were collected at Saint Luc Hospital. Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) represented the majority of clinically significant isolates, with a substantial proportion confirmed as ESBL-producers (75.5%).

2.2. Epidemiologic characteristics of patients with ESBL-NTS Bacteremia

Table 1.

Epidemiologic characteristics of patients with ESBL-NTS cases.

Table 1.

Epidemiologic characteristics of patients with ESBL-NTS cases.

| Characteristics |

Total number of NTS

(n=1,568) |

Number of ESBL-NTS (n=1,184) |

Percentage

(%) |

95% CI (%) |

| Age group |

|

|

|

|

| Less than 24 months |

1,094 |

853 |

78.0 |

75.4–80.3 |

| From 24 months to 59 months |

350 |

245 |

70.0 |

65.0–74.6 |

| From 5 to 14 years |

87 |

59 |

67.8 |

57.4–77.0 |

| Aged 15 years and over |

37 |

27 |

73.0 |

57.0–84.6 |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

839 |

641 |

76.4 |

73.5–79.3 |

| Female |

729 |

543 |

74.5 |

71.2–77.7 |

The majority of ESBL-producing NTS isolates were from children under 5 years (1,098 of 1,184; 92.7%), including nearly 72% from those under 24 months. The proportions of ESBL remained high across all age groups (67.8–78.0%), slightly higher in children under 24 months (78.0%; 95% CI: 75.4–80.3). Proportions were similar between boys (76.4%) and girls (74.5%).

2.3. Temporal Trends in ESBL production (2019 to 2022)

Table 2.

Quarterly (Q) distribution of ESBL producing NTS isolates (n=1,568).

Table 2.

Quarterly (Q) distribution of ESBL producing NTS isolates (n=1,568).

| N° |

Quarter/Year |

Total number of NTS |

Total number of ESBL-producers NTS |

Observed % |

Predicted % |

95% CI (%) |

| 1 |

Q1/2019 |

70 |

10 |

14.3 |

11.9 |

10.0–14.1 |

| 2 |

Q2/2019 |

63 |

16 |

25.4 |

13.5 |

11.3–15.9 |

| 3 |

Q3/2019 |

81 |

58 |

71.6 |

15.2 |

12.8–17.9 |

| 4 |

Q4/2019 |

166 |

137 |

82.5 |

17.0 |

14.4–20.0 |

| 5 |

Q1/2020 |

291 |

228 |

78.4 |

19.1 |

16.2–22.3 |

| 6 |

Q2/2020 |

68 |

56 |

82.4 |

21.3 |

18.2–24.8 |

| 7 |

Q3/2020 |

58 |

49 |

84.5 |

23.8 |

20.4–27.5 |

| 8 |

Q4/2020 |

143 |

107 |

74.8 |

26.4 |

22.7–30.3 |

| 9 |

Q1/2021 |

145 |

130 |

89.7 |

29.2 |

25.3–33.4 |

| 10 |

Q2/2021 |

31 |

28 |

90.3 |

32.1 |

28.0–36.5 |

| 11 |

Q3/2021 |

38 |

22 |

57.9 |

35.2 |

30.9–39.8 |

| 12 |

Q4/2021 |

81 |

54 |

66.7 |

38.4 |

33.9–43.2 |

| 13 |

Q1/2022 |

142 |

112 |

78.9 |

41.8 |

37.1–46.6 |

| 14 |

Q2/2022 |

83 |

78 |

94.0 |

45.2 |

40.4–50.1 |

| 15 |

Q3/2022 |

43 |

41 |

95.3 |

48.7 |

43.8–53.5 |

| 16 |

Q4/2022 |

65 |

58 |

89.2 |

52.1 |

47.2–57.0 |

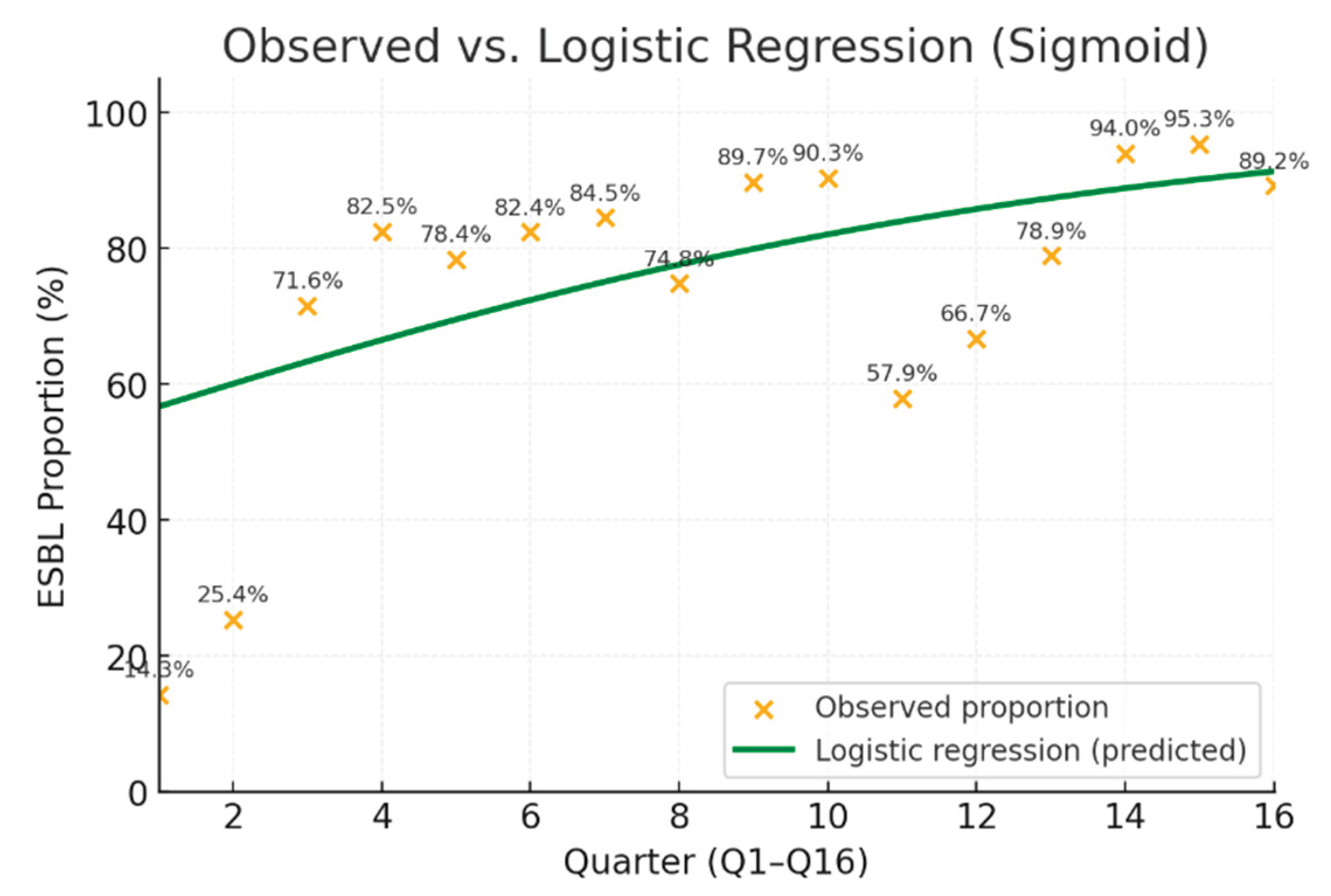

A clear increasing trend in ESBL prevalence was observed, from 14.3% in Q1/2019 to 95.3% to Q3/2022.

Figure 2.

Result of time analysis from 2019 to 2022.

Figure 2.

Result of time analysis from 2019 to 2022.

Logistic regression showed a significant upward trend in ESBL producers over time (β = 0.139, OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.11–1.19, p < 0.001), indicating a 15% increase in odds per additional quarter.

2.4. Resistance Profile of ESBL-NTS (n=1,184)

Table 3.

Resistance Profile of ESBL-NTS to antibiotics.

Table 3.

Resistance Profile of ESBL-NTS to antibiotics.

| Antibiotics/Resistance mechanism |

Resistance

% (n=1,184) |

| Ampicillin |

100.0 |

| Ceftriaxone/cefotaxime |

100.0 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

98.8 |

| Chloramphenicol |

99.2 |

| Ciprofloxacin |

94.3 |

| Imipenem/meropenem |

0.0 |

| XDR |

94.1 |

| PDR |

6.3 |

| |

|

Among ESBL-producing NTS isolates, resistance to conventional antibiotics was high, whereas susceptibility to carbapenems was retained. The majority of isolates exhibited an Extensively Drug-Resistance (XDR) profile (94.1%), and 6.3% were Pan-Drug-Resistance (PDR).

It should be noted that azithromycin susceptibility testing was performed only between September 2021 and December 2022 for 345 isolates, among which 6.4% exhibited resistance; these data are not included in the main table.

3. Discussion

In terms of clinically significant bacteria, non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is the leading cause of bloodstream infections at Saint Luc Hospital in Kisantu. This is consistent with findings from previous surveillance studies in Kisantu, DRC and other regions of sSA, particularly among pediatric populations (7,9,10,12,13,16).

The 75.5% proportion of ESBL production among NTS isolates in this study marks a sharp increase compared to historical data: 0% in 2010-2011 (Phoba et al.), and less than 2% from DRC between 2007-2021 (Lunguya et al.) (13,17). This trend highlights the alarming progression of resistance, likely driven by antibiotic overuse or misuse, as well as by changes associated with evolving serotypes (10,14). The proportion of ESBL-producing NTS isolates would likely have been slightly higher if all 113 isolates had been tested for ESBL production.

Most ESBL-producing NTS isolates were recovered from children under 5 years of age, particularly those under 24 months of age, confirming their greater vulnerability to invasive infections. This finding is consistent with the usual pattern of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections, which predominantly affect young children, and supports previous observations reported by several authors, including Tack et al. and Kalonji et al. in DRC. (10,12). However, the proportion of ESBL-producing isolates did not differ significantly across age groups or sex, suggesting a widespread dissemination of resistant strains within the population.

The quarterly analysis revealed a significant upward trend in ESBL-NTS prevalence over the study period, although the effect of time may be influenced by other unmeasured factors. These findings suggest a potential role of antibiotic selective pressure, which reinforces the importance of careful and controlled antimicrobial use (14).

Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) isolates were detected at very high proportions in the present study, in contrast to the low proportions reported by Tack et al. for NTS isolates from Kisantu between 2015-2017 (10). The high proportions of XDR and PDR isolates may be explained by the co-occurrence of plasmid-borne resistance genes, with ESBL genes frequently associated with other resistance determinants, thereby promoting the emergence of multidrug-resistant profiles (18). The level of resistance to ciprofloxacin was significantly elevated in comparison to previously documented statistics from the DRC and other African regions (9,10,12,13,17). This sharp increase may reflect a growing selective pressure due to the widespread use of fluoroquinolones and raises concern about the future efficacy of this class of antibiotics.

Although the CLSI does not currently recommend routine susceptibility testing of azithromycin for NTS, the proportion of resistant isolates observed in this study was low (6.4%) (19). As one of the few antibiotics accessible to patients, azithromycin represents one of the limited therapeutic options still available, although it is a “Watch group” antibiotic (20), its use is supported by only a few clinical guidelines, and only as an oral treatment in the non-acute phase of the disease (15,21). Our results revealed no resistance to carbapenems, but access to these antibiotics remains limited for the population of Kisantu due to their high cost, consistent with observations from other studies conducted in certain African countries (22).

Strengths and study limitations:

In the context of this temporal dynamics analysis, the potential impact of confounding factors has not yet been assessed and remains to be evaluated in future work. Blood cultures were embedded in routine patient care and a national surveillance project, ensuring consistent and uninterrupted sampling. This study represents the first investigation in the DRC to examine the temporal trends of ESBL-producing NTS isolates.

Molecular characterization of the isolates, including confirmation of the ESBL genes involved, has not yet been performed and remains a step for future investigation. Azithromycin resistance was tested for only a small subset of NTS isolates and Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values were not determined; however, a previous study demonstrated an excellent correlation between disk diffusion results and MIC values (23). Serotype determination was not performed; nevertheless, Salmonella Typhi was reliably distinguished from non-typhoidal Salmonella using biochemical reactions.

4. Materials and methods

Study Design:

A retrospective observational study was conducted at Saint Luc Hospital in Kisantu, DRC, from January 2019 to December 2022. This investigation is part of the national AMR surveillance Network established by the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB) in collaboration with the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp (ITM) (10,12,13). The surveillance system, initiated in 2007, has been running continuously and involves the systematic collection of blood cultures from all patients presenting with suspected bacteremia. For the purpose of this study, the inclusion criterion was all patients with a positive blood culture for non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS). Analyses excluded patients with bacteremia due to any other bacteria, including Salmonella Typhi. Deduplication was performed at the isolate level to ensure that only one isolate per episode of bloodstream infection per patient was included. An episode was defined as any blood culture collected within a period of ≤14 days from the same patient. In addition, NTS isolates for which the ESBL profile had not been not investigated by the laboratory, despite showing resistance to ceftriaxone. Some of the data were collected during the implementation of the Severe Typhoid in Africa (SETA) study in Kisantu (2017-2020) and additional data were collected at the beginning of the implementation of the Effect of a Novel Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine in Africa (THECA) study (2021-2022) (24,25).

Study site:

Saint Luc Hospital is the only general referral hospital in Kisantu Health Zone, located in the Province of Kongo Central (southwestern part of the DRC), approximately 121 km from the capital, Kinshasa. The health zone of Kisantu covers an area of about 2,400 km2, with a total population of approximately 190,000 inhabitants of which 45% reside in semi-urban areas. The health zone is currently subdivided into 18 health areas, each comprising a health center responsible for patient care and referral to the hospital in accordance with national guidelines (10).

Since 2007, the hospital has been part of the national surveillance network for bacterial antibiotic resistance, with integration of blood cultures into routine clinical practice (10,13,26). Plasmodium falciparum malaria, one of the main risk factors for the occurrence of NTS invasive infections, remains endemic in Kisantu Health Zone, as in the rest of the country (27,28).

Sample collection

Blood cultures were collected from patients presenting at Saint Luc Hospital of Kisantu with clinical suspicion of bloodstream infections. Collection procedures followed standardized protocols, including those described by Tack et al. (10).

Laboratory analysis

Upon reception in the laboratory, blood culture bottles (BacT/ALERT, bioMérieux, Marcy-L’Etoile, France) were incubated at 37 °C for up to seven days. Daily monitoring was performed to detect color changes at the base sensor of the bottles, indicating microbial growth. Any positive bottle was immediately removed from the incubator and processed for further analysis. Identification of NTS isolates was performed using standard biochemical methods (13), based on two specific biochemical characteristics that allowed us to exclude Salmonella Typhi: the ability to metabolize citrate on Simmons citrate medium and positive ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) activity.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by the Kirby Bauer disk diffusion method using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, updated annually from 2019 to 2022 (29–32). ESBL production was detected using the combined disk method, a ≥5 mm increase in the diameter of the inhibition zone around a cefotaxime or ceftazidime disk when combined with clavulanic acid, compared to the zone produced by the same disk(s) without clavulanic acid (29–32). In addition, the antibiotic panel tested included ampicillin (10µg), ceftriaxone (30µg)/cefotaxime(30µg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75µg), chloramphenicol (30µg), pefloxacin (5µg), azithromycin (15µg) and imipenem (10µg)/meropenem (10µg).

Resistance to fluoroquinolones, particularly ciprofloxacin, was assessed based on the resistance observed to pefloxacin (29–32).

Azithromycin was introduced in the laboratory in September 2021, following the surge in resistance among NTS and the promising susceptibility results reported by Tack et al. (2022) (23). In the present study, for the interpretation of azithromycin susceptibility testing results, we applied the clinical breakpoints defined by CLSI for Salmonella Typhi in 2021 and 2022 (29–32), as recommended given the absence of validated breakpoints for non-typhoidal Salmonella. This approach is supported by Tack et al. (2022), who highlighted the relevance of the Salmonella Typhi ECOFF for guiding azithromycin susceptibility interpretation in NTS isolates (23). Ultimately, azithromycin susceptibility was assessed for only 345 NTS isolates out of the total collection of NTS ESBL-producers.

The non typhoidal Salmonella were characterized as follows:

XDR (Extensively Drug-Resistance): co-resistance to ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone and pefloxacin (10).

PDR (Pan-Drug-Resistance): co-resistance to ampicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone, pefloxacin, and azithromycin (10).

Data collection and Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded in Excel 2016 and analyzed using Stata 18 (StataCorp, College station, TX, USA) and RStudio (version 2025.09.1+401; Posit Software, PBC).

The dependent variable was the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) by non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS). Independent variables included the date of blood culture collection, patient age, sex, and the resistance profile of NTS to various antibiotics Descriptive statistics were presented using frequency tables and figures. Only the first isolate per bloodstream infection episode was considered for analysis, and control blood culture cases were also excluded.

Patients were categorized into four age groups: <2 years, 2–4 years, 5–14 years, and ≥15 years. For each group, the proportion of ESBL-producing NTS isolates was calculated by dividing the number of ESBL isolates by the total number of NTS isolates. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for distributions by age group and sex, allowing assessment of both relative prevalence and absolute burden.

The temporal evolution of the proportion of non-typhoidal Salmonella producing ESBL between 2019 and 2022 was analyzed using logistic regression. Data were aggregated by quarter, considering for each period the total number of isolates and the number of ESBL-producing isolates.

The dependent variable was ESBL presence, expressed as the number of events out of the total isolates. Time (t), coded from 0 to 15 for the 16 consecutive quarters, was used as the explanatory variable.

A binomial logistic regression model was fitted according to the formula Logit(pt)=β0 + β1 x t, where pt represents the probability of observing an ESBL isolate in quarter t.

A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied.

Resistance proportions for each antibiotic were calculated among ESBL-producing isolates.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights a critical and escalating public health concern in Kisantu, DRC, due to the high prevalence of ESBL-producing NTS bacteremia between 2019 and 2022. More than three-quarters of all NTS isolates were ESBL-producers. While the proportions of ESBL-producing isolates were relatively similar across all age groups, children under 5 years, particularly those under 24 months, carried the highest absolute burden. Similar proportions between sexes indicate widespread dissemination of resistant strains throughout the population.

The temporal analysis demonstrated a statistically significant increase in ESBL prevalence, suggesting a growing selective pressure likely driven by widespread empirical use of third-generation cephalosporins. Additionally, the high proportions of XDR and PDR further restrict available therapeutic options and raise urgent concerns regarding the effectiveness of first-line antibiotics.

In contrast, no resistance to carbapenems was observed, and azithromycin resistance remained low, although its role in NTS treatment remains to be clarified by further clinical studies.

These findings underscore the urgent need to strengthen AMR surveillance, implement rational antibiotic prescribing policies, and invest in molecular studies to better understand resistance mechanisms. In addition, vaccination together with targeted interventions, is crucial to protect vulnerable pediatric populations and preserve the effectiveness of remaining treatment options.

Author: Contributions: Conceptualization: Jules Mbuyamba, Octavie Lunguya; Methodology: Jules Mbuyamba, Octavie Lunguya; Data Curation: Edmonde Bonebe, Marie-France Phoba, Lisette Mbuyi-Kalonji; Formal Analysis: Glody-Nickel Mbaa, Jules Mbuyamba,; Investigation: Jules Mbuyamba, Daniel Vita, Edmonde Bonebe, Gaelle Nkoji, Marie-France Phoba, Lisette Mbuyi-Kalonji, Mohamadou Siribie, Birkneh Tilahun Tadesse, Anne-Sophie, Jan Jacobs and Octavie Lunguya; Supervision: Octavie Lunguya; Writing—Original Draft: Jules Mbuyamba; Writing—Review & Editing: All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Belgian Directorate of Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid (DGD) through the Framework Agreement between the Belgian DGD and the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Belgium. Additional support was provided by the SETA (Severe Typhoid in Africa) project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number OPP1127988), and by the THECA (The Effect of a Novel Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine in Africa: a multicenter study in Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo) project supported by the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) (grant number RIA2017S-2027).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is part of the national AMR surveillance program in the DRC. Ethical approvals were obtained from the Kinshasa School of Public Health Ethics Committee (ESP/CE/073/2015, ESP/CE/074/2015, ESP/CE/092/2021), the Institutional Review Board of ITM Antwerp (IRB/AB/AC/098, IRB/AB/AC/053, IRB/AB/AC/111) and University Hospital Antwerp Ethics Committee (B30020084213).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study analyzed anonymized data collected through routine national multicenter surveillance of bacteremia and antimicrobial resistance at the Kisantu site. No direct patient intervention was performed.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study come from an extract of the database of the National Multicenter Surveillance Network for Bacteremia and Antimicrobial Resistance, specifically corresponding to the Kisantu site. The full database is held by the National Institute of Biomedical Research (INRB), in the Department of Bacteriology and Research. The datasets analyzed are not publicly available due to confidentiality and ethical restrictions but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with authorization from the surveillance network coordinators.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of Saint Luc Hospital in Kisantu and the team of the National Institute for Biomedical Research (INRB) for their technical support and contribution to the antimicrobial resistance surveillance network. The authors further acknowledge the support and collaboration of the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Antwerp, for its continuous technical assistance and involvement in the coordination of the surveillance activities. The authors acknowledge the use of the artificial intelligence tool ChatGPT to assist in grammar. All content generated by the AI was carefully reviewed and validated by the authors, who take full responsibility for the scientific accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the analysis or interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CLSI |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CSO |

Clinically significant isolate |

| DRC |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

| ECOFF |

Epidemiological cut-off |

| ESBL |

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase |

| INRB |

Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale |

| ITM |

Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp |

| NTS |

non-typhoidal Salmonella

|

| ODC |

Ornithine decarboxylase |

| PDR |

Pan-Drug-Resistance |

| Q |

Quarter |

| sSA |

sub-Saharan Africa |

| SETA |

Severe Typhoid in Africa |

| THECA |

The Effect of a Novel Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine in Africa |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| XDR |

Extensively Drug-Resistance |

References

- Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system: manual for early implementation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015.

- no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections-en.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections-en.pdf.

- Adedeji, WA. The treasure called antibiotics. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2016 Dec;14(2):56–7.

- Gaynes, R. The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 May;23(5):849–53.

- Cattoir, V. Les nouvelles beta-lactamases a spectre etendu (blse). 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh S, Fatima J, Shakil S, Rizvi SMohdD, Kamal MA. Antibiotic resistance and extended spectrum beta-lactamases: Types, epidemiology and treatment. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015 Jan 1;22(1):90–101.

- Crump JA, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Gordon MA, Parry CM. Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Laboratory Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Antimicrobial Management of Invasive Salmonella Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015 Oct;28(4):901–37.

- Kim JH, Tack B, Fiorino F, Pettini E, Marchello CS, Jacobs J, et al. Examining geospatial and temporal distribution of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease occurrence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and modelling study. BMJ Open. 2024 Mar 14;14(3):e080501.

- Marks F, Kalckreuth V von, Aaby P, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Tayeb MAE, Ali M, et al. Incidence of invasive salmonella disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentre population-based surveillance study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017 Mar 1;5(3):e310–23.

- Tack B, Phoba MF, Barbé B, Kalonji LM, Hardy L, Van Puyvelde S, et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bloodstream infections in Kisantu, DR Congo: Emergence of O5-negative Salmonella Typhimurium and extensive drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Apr;14(4):e0008121.

- Stanaway JD, Parisi A, Sarkar K, Blacker BF, Reiner RC, Hay SI, et al. The global burden of non-typhoidal salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Dec 1;19(12):1312–24.

- Kalonji LM, Post A, Phoba MF, Falay D, Ngbonda D, Muyembe JJ, et al. Invasive Salmonella Infections at Multiple Surveillance Sites in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2011-2014. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2015 Nov 1;61 Suppl 4:S346-353.

- Lunguya O, Lejon V, Phoba MF, Bertrand S, Vanhoof R, Glupczynski Y, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in invasive non-typhoid Salmonella from the Democratic Republic of the Congo: emergence of decreased fluoroquinolone susceptibility and extended-spectrum beta lactamases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(3):e2103.

- Tack B, Vita D, Ntangu E, Ngina J, Mukoko P, Lutumba A, et al. Challenges of Antibiotic Formulations and Administration in the Treatment of Bloodstream Infections in Children Under Five Admitted to Kisantu Hospital, Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023 Dec 6;109(6):1245–59.

- Tack B, Vanaenrode J, Verbakel JY, Toelen J, Jacobs J. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review on antimicrobial resistance and treatment. BMC Med. 2020 Jul 17;18(1):212.

- Crump JA, Nyirenda TS, Kalonji LM, Phoba MF, Tack B, Platts-Mills JA, et al. Nontyphoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease: Challenges and Solutions. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023 May;10(Suppl 1):S32–7.

- Phoba MF, Lunguya O, Mayimon DV, Lewo di Mputu P, Bertrand S, Vanhoof R, et al. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 Oct;18(10):1692–4.

- Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases: a Clinical Update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005 Oct;18(4):657–86.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [Internet]. 35st Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2025. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

- AWaRe classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use, 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.04.

- CDC. Salmonella Infection (Salmonellosis). 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 4]. Clinical Overview of Salmonellosis. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html.

- Thomson KM, Dyer C, Liu F, Sands K, Portal E, Carvalho MJ, et al. Effects of antibiotic resistance, drug target attainment, bacterial pathogenicity and virulence, and antibiotic access and affordability on outcomes in neonatal sepsis: an international microbiology and drug evaluation prospective substudy (barnards). Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Dec 1;21(12):1677–88.

- Tack B, Phoba MF, Thong P, Lompo P, Hupko C, Desmet S, et al. Epidemiological cut-off value and antibiotic susceptibility test methods for azithromycin in a collection of multi-country invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 Dec 1;28(12):1615–23.

- Greear, J. First TCV effectiveness study in Central Africa launched in the DRC [Internet]. Take on Typhoid. 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www.coalitionagainsttyphoid.org/drc-launches-tcv-study/.

- Marks F, Im J, Park SE, Pak GD, Jeon HJ, Wandji Nana LR, et al. Incidence of typhoid fever in Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Madagascar, and Nigeria (the Severe Typhoid in Africa programme): a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2024 Apr;12(4):e599–610.

- Mbuyi-Kalonji L, Hardy L, Mbuyamba J, Phoba MF, Nkoji G, Mattheus W, et al. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella from stool samples of healthy human carriers are genetically similar to blood culture isolates: a report from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1282894.

- World malaria report 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024.

- Ilombe G, Matangila JR, Lulebo A, Mutombo P, Linsuke S, Maketa V, et al. Malaria among children under 10 years in 4 endemic health areas in Kisantu Health Zone: epidemiology and transmission. Malar J. 2023 Jan 5;22:3.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [Internet]. 29st Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2019. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [Internet]. 30st Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2020. Available from: https://clsi.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [Internet]. 31st Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2021. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [Internet]. 32st Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2022. Available from: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m100/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).