1. Introduction. Topological Transitions and Dual Symmetry of Two-Dimensional

Systems

As is well known, topological phase transitions have been discovered in various materials and have been applied to explain the different physical phenomena [

1,

2,

3]. Recently the theory of topological phase transition was used for explanation of integer Quantum Hall Effect [

4,

5]. The aim of this paper is to study phase transitions in a new class of materials—non-dissipative systems such as disordered LC networks—with possible applications to metamaterials [

6,

7]. For this we study the two-phase two-dimensional system, consisting of reactance - of inductors L and capacitors C (non-dissipative elements) with its random placement. At first glance, it seems that percolation in this disordered system has a simple way: a cluster would be formed from all non-dissipative phases because the principle of minimal Joule heat does not apply here:

Thus, in the studied non-dissipative case

. However, the situation is more complex and interesting: the percolation cluster is formed from phases only certain type due to shielding of the electric field. The transition from one percolation cluster to another takes the form of a topological transition.

The paper is structured as follows. In the second part the model of LC disordered system was introduced. In the third part the results of investigations, including the new topologic invariants for this problem, were reported. The fourth part concludes the paper. The discussions of obtained results were given.

2. Model of Disordered System, Consisting of Randomly Connected Inductors L and Capacitors C

The key feature of the two-dimensional DC equations and Ohm’s law, which describe a two-dimensional conducting medium, is their internal symmetry:

where

and

local electric current and electric field,

is the conductivity of the medium, that they have internal symmetry – the invariance relatively to linear rotational transformations [

8,

9,

10]:

Here

is a unit vector normal to the plane.

To understand the nature of the rotational symmetry in a two-dimensional system and to demonstrate it, let us consider a chessboard system. This system has three permutation symmetries: 1) an interchange of white and black color cells of chessboard (1↔2) – see

Figure 1.

2) an interchange of white and black color cells of chessboard (1↔2) in its positions and change of the direction of normal vector as (1↔2) and 3) the change of the direction of normal vector only as A disordered system with randomly placed cells possesses the same permutation symmetries – see Appendix A.

According to Dykhne’s method, which described in details in Appendix A, the effective conductivity of the two-phase random medium consisting of non-dissipative resistances - capacitances and inductors is described by the equation:

where

is the conductivity of the i-th component;

is the effective conductivity of the percolation cluster formed mainly the resistors

;

is the effective conductivity of the percolation cluster formed mainly by the resistors

. More details see in Appendix A.

However, this solution (1) is not valid at the percolation threshold

, because in this case one must use the rotational transformations (A2) with another coefficients

. Consequently, the following expression for the effective conductivity is obtained from equation (A6):

The key feature of this solution is that the effective conductivity is a real value. This result is unexpected and interesting: although the medium consists of non-dissipative elements (inductors and capacitors), dissipation nevertheless appears. The analogous result firstly was obtained in [

8], see too [

10]. The physical sense is clear - the dissipation of energy is connected with the excitations of set of LC circuits. At first sight, formula (3) may seem to contradict result (5), but these results are analogous to those for the Quantum Hall effect, where the off-diagonal component

exhibits a plateau and the diagonal component has a non-zero value

at the transition point. And to explain these results the approach of topological phase transitions was applied [

11,

12,

13].

Below we introduce a model of a disordered system, consisting of randomly connected inductance L and capacitance C. The problem of the effective conductivity of this disordered system was studied. To analyze this, we applied the exact Dykhne’s approach, which based on the rotational symmetry of two-dimensional medium. (This method was described in details in Appendix A.) According to this approach, to calculate the effective conductivity of the disordered system, consisting of randomly connected inductances L and capacitances C it is necessary to find the symmetric transformations system to itself or dual system.

3. The Topological Phase Transition

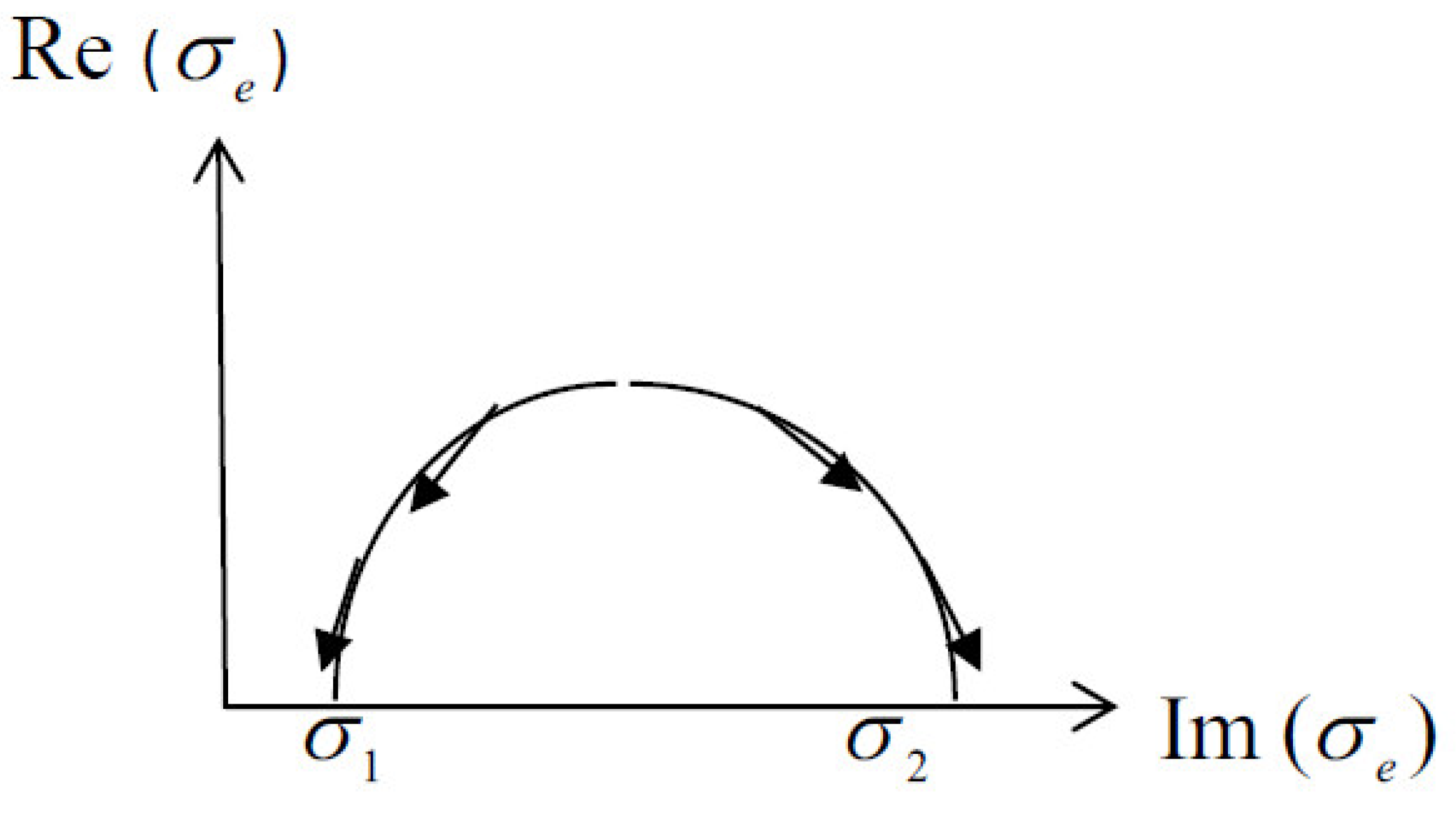

To examine this transition in more detail, let us consider formulas (A5) and (A6) in the case of third permutation so in general case we obtain the semi- circle relation:

This is a semi-circle relation because only the case with a positive real part of the conductivity is considered:

- see

Figure 2.

3.1. The Construction of Percolation Cluster in the Case of LC Systems with Non-Dissipative Components

According to formula (6), on the line

, there exist the two stable points

and

, corresponding to the solutions (3). As the value of

decreases, the trajectory toward these solutions follows the semicircle. From the left part of this line the solution of the equation will go to the stable point

and from the right part of this line the solution will go to the point

according to the

Figure 2.

One solution

corresponds to the creation of a percolation cluster of capacitances, and the other solution

corresponds to the creation of a percolation cluster of inductors. It is unexpected that the percolation cluster is formed from a phase of only one type. As described above, all phases are non-dissipative, and it seems possible to form a cluster from both phases since there is no restriction from physical laws such as the minimization of Joule heat dissipation (1). To analyze equation (3) and understand why only one of the two solutions is realized, let us consider the distribution of the electric fields in the studied disordered two-phase LC system. For this aim let’s calculate the following quantity:

After averaging over two phases the following expression is obtained:

Then after averaging over second phase so the another expression is obtained:

In the case when the percolation cluster is formed from 1 phase the effective conductivity is equal to:

and

. Consequently from (9) the following result is followed:

This result means that the percolation cluster forms only from the first non-dissipative phase and electric current does not flow through the second non-dissipative phase. In the other case, when the percolation cluster forms only from the second phase, let us calculate a different quantity:

After averaging over two phases the following expression is obtained:

In the case when the percolation cluster is formed from 2 phase the effective conductivity is equal to and . Consequently from (12) the following result is followed:

Then after averaging over first phase so the another expression is obtained:

Thus, the electric field in the first phase is zero:

These formulae (10) and (14) explain the behavior of electric current in disordered LC systems and the existence of two different values of effective conductivities, which are determined by the conductivity of only one phase. In other words, although both phases are non-dissipative, the percolation cluster is formed exclusively by one phase, and the other phase does not participate in forming this percolation cluster. This is not obvious, and the physical reason the current does not flow through the second phase is the shielding of the electric field within it. Consequently, one can speak of the existence of two distinct percolation clusters composed of different phases. The existence of two distinct and non-mixing phases, such as inductors L and capacitors C, is connected to their different physical properties, namely their different phase shifts relative to the applied electric field . Usually in the classical case, phase shift does not influence transport phenomena, but in the case studied here, this is not true. The reason for this unusual behavior is the transition between solutions, which takes the form of a topological transition.

3.2. The Topologic Transition from One to Another Phase in the Non-Dissipative Component Case. Topologic Invariants

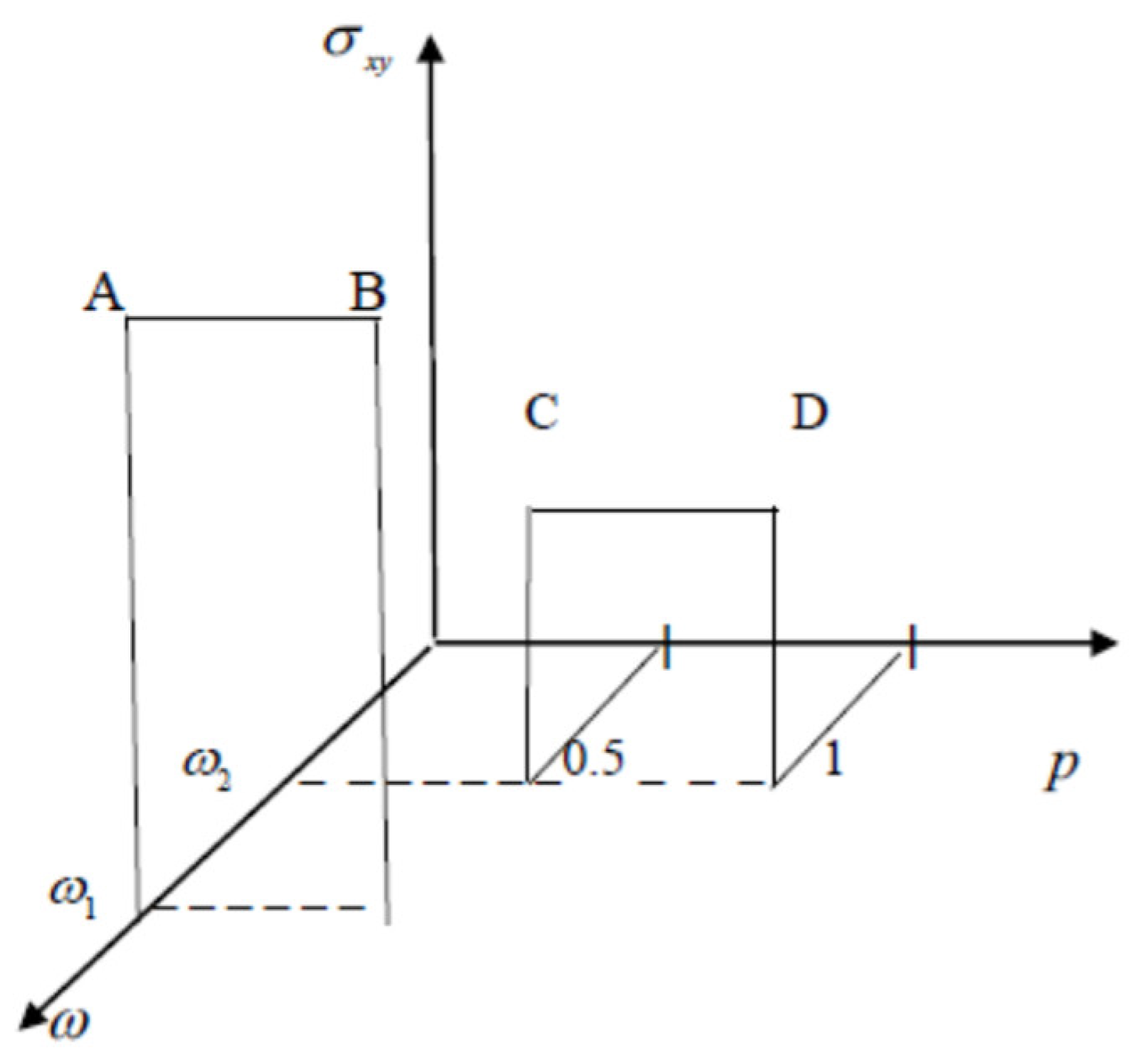

So according the formula (4) the effective conductivity has a step-like dependence at the projection for a plane

at fixed frequency – see

Figure 3. Let’s consider the transition from one solution to another solution (4), which occur at the percolation threshold

. The graphic presentation of these transitions is presented at

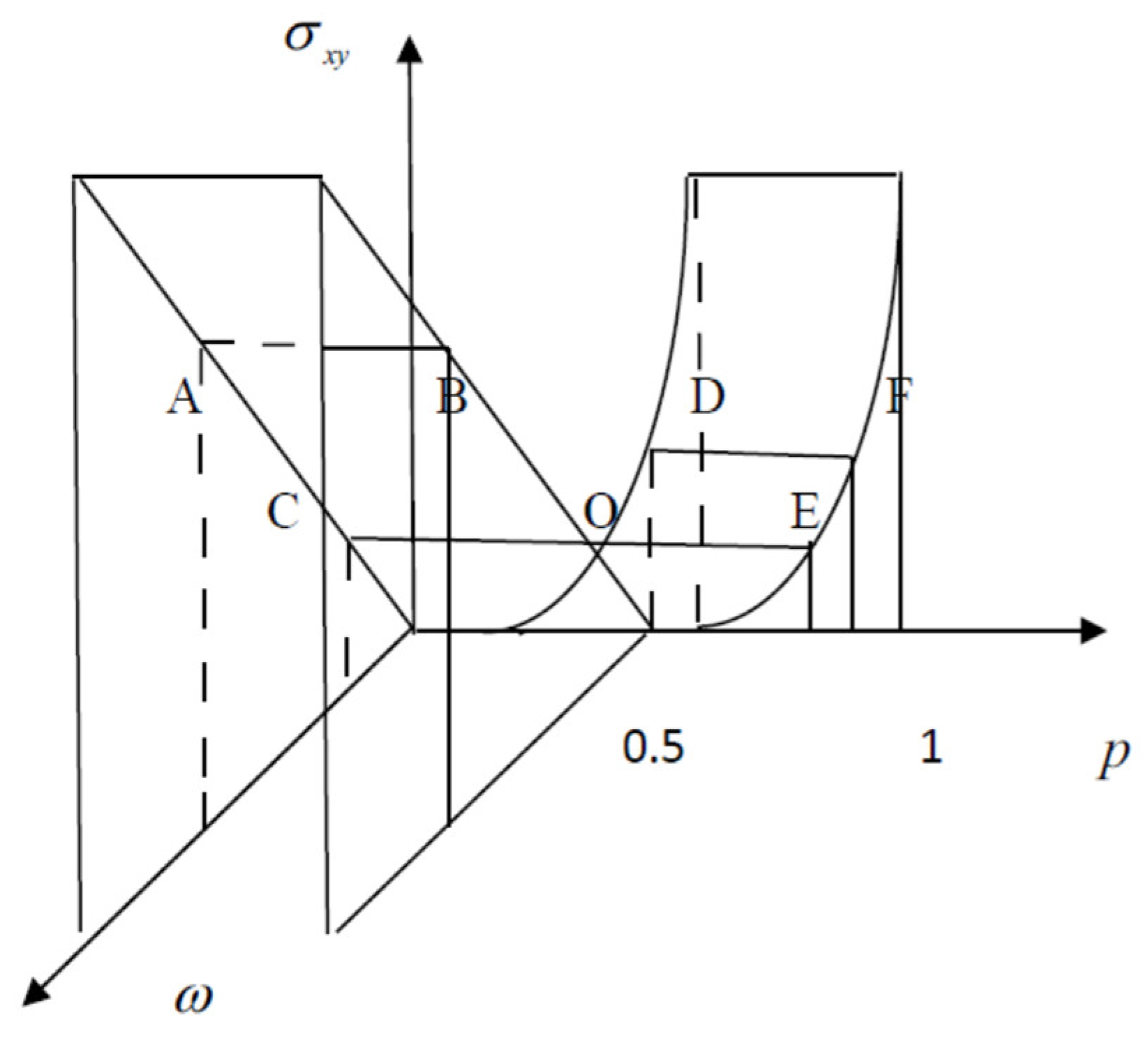

Figure 4.

Let us consider the transition from the plane of inductances L (ABCO) with impedance

to the plane of capacitances C (OEDF) with impedance

through the point O, which has a real value. This transition is possible only along the line COE at a fixed frequency

from one phase to another phase —see

Figure 4. So that there is a transition between phases similar to quantum transition such a Quantum Hall Effect [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Therefore, to calculate the topological invariant characterizing this transition, the integration must be performed along a path of constant amplitude, where only the phase changes. So the new characteristics of this transitions is phase change, measured in radians, when it passing through the real value point, and it is described by following formula [

15,

16,

17]:

Consequently, the topological invariant in the studied topological transition between non-dissipative phases is:

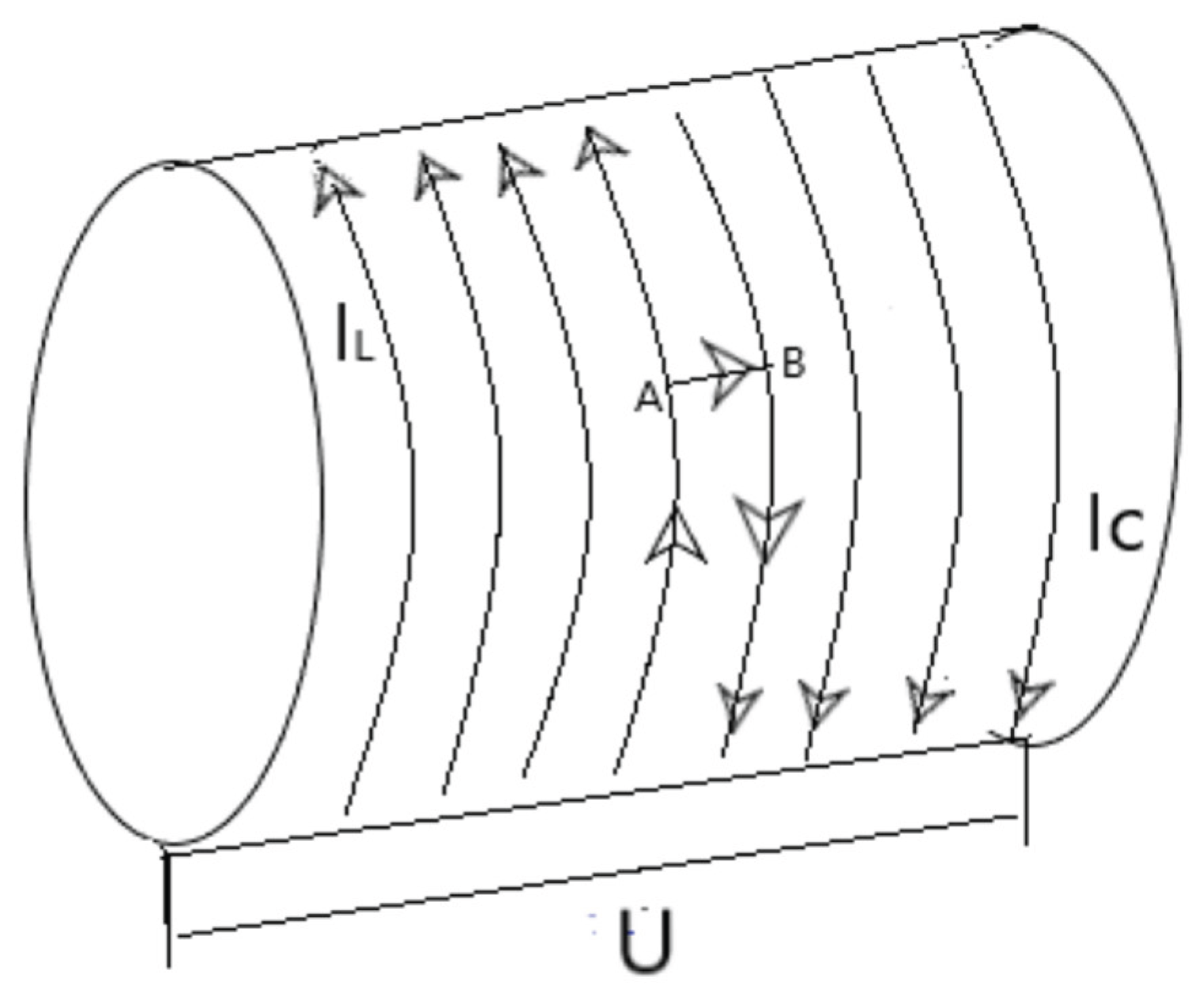

The obtained result can also be illustrated visually as follows. Consider a graphical representation of non-dissipative current flow on a cylindrical surface, similar to the current flow diagram in the quantum Hall effect regime [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Suppose that initially currents flow in the inductive phase

, which leads the applied voltage in phase by

. Then, at the phase transition point a transition occurs through a dissipative state into a new non-dissipative capacitive phase

with current lagging in phase by

. The current through the dissipative state is in phase with the applied voltage – see

Figure 5. But it is not direct way to change the direction of the current to opposite – from inductance alternative current to capacitance alternative current. For this one needs to сreate a locally oscillating circuit in which the oscillations on the inductance will be transmitted to the oscillations on the capacitance. When creating local circuits, the final Joule heat is released in the system – the energy is dissipated.

4. Discussion

In this work, we have studied current flow in a two-dimensional system of randomly connected circuit elements. It has been shown that the effective conductivity is constant (independent of phase concentration) and is equal to either the capacitive reactance or the inductive reactance—see formula (3) and

Figure 4. The step-like dependency of the effective conductivity at fixed frequency and arbitrary phase concentrations appears strange and unexpected. But as we have shown above, the classical quantization in disordered LC systems is connected with the shielding of the electric field in such systems. Although all phases are non-dissipative and there is no governing principle like the minimization of Joule heat to form a percolation cluster, the capacitive and inductive reactance phases have different phase shifts relative to the electric field. This difference prevents the formation of a percolation cluster from different non-dissipative components. In other words, this result shows that there may be another principle governing percolation in non-dissipative systems.

The important feature of the studied phase transition is appearance of the finite effective resistance at the percolation threshold appears in a system, consisting of the non-dissipative elements as inductivities and capacities, placed randomly in the system and randomly connected between them. The emergence of a dissipative state with finite resistance can be understood as follows. Let the initial phase through which the current flows consist of inductors, then all the energy is concentrated in the inductors . In order for current to flow through another phase, in our studied case the capacitive phase, it is necessary to transfer this energy to the capacitances , and for this it is necessary to excite local oscillations in the circuits, creating by the random connection of inductances and capacitances into the local LC circuit during which the energy will be transferred from the inductors to the capacitances. But for this it is necessary to create and excite local circuits, joining of inductance and capacitance into the circuit. After excitation of these oscillating circuits the energy from inductances transfer to capacitances and the transition from percolation cluster, consisting of inductances, to new percolation cluster, consisting of capacitances, is occurred. The finite Joule heat is dissipated at the excitation of a set of local oscillating circuits. Then it becomes clear how the transition from one percolation cluster to another occurs and why the finite Joule heat is released. It seems interesting to generalize these results for a case of multi-phase system and study the topological transitions in the many-phase case.

In our opinion, the obtained results can be applied in the study of metamaterials (materials with a negative refractive index). As is known, metamaterials are constructed from inductances and capacitances so the obtained results may be used to explain some properties of metamaterails and may be to show the direction of further investigations of metamaterials, for example, to search the features of the its properties near the percolation threshold. From our results the step-like behavior and stability of response for alternative electromagnetic field follow near this threshold. But this paper investigates only the two-dimensional case while the meta-materials are three-dimensional materials so there are some questions of direct applicability of use of obtained results. Nevertheless the some physical mechanisms as creation and excitation of local oscillatory circuits may be conserved and as result the integral Joule heat is dissipated near percolation threshold. Far from the percolation transition region the local oscillatory circuits are excited but not are connected in the global percolation cluster and after averaging over volume their contribution into the dissipation should be negligible. So it is interesting to study properties of metamaterials when its components will be near percolation threshold over concentration and search the classical analogs of quantum transitions in the class of meta-materials. And the one of the important questions is the dissipation in three-dimensional system, consisting of non-dissipative components ? In analogy with two-dimensional case the finite Joule heat is possible at percolation threshold and the percolation cluster must have the equal quantities of inductances and capacitances. And as a result the local oscillating circuits may be create from inductances and capacitances and excite. The dissipation of Joule heat is arise in the case of the global connectivity of excited oscillating circuits.

Another feature of global connectivity in the three-dimensional case there is the existence of two independent percolation clusters simultaneously and this circumstance may be lead to new type transitions between these independent percolation clusters. It is not obviously and further research is needed to study this problem

In other words, the transition from one non-dissipative state of the system, described by conduction, to another non-dissipative state, described by a different value, is possible only through the excitation of the circuit, i.e., through the dissipative state at the point of topological transition.

In our opinion, the obtained results can be used in studying the properties of metamaterials.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge prof. Dr. Ngo Son Tung and Prof. Dr Nguyen Xuan Sang for a support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. The Exact Method for Studying Disordered Conducting Media: The Dykhne Approach

In the general case of an anisotropic medium, for example, in a magnetic field, Ohm’s law has a tensor form:

Here

is a two-dimensional conductivity tensor with components

and

. Therefore, in this case, to describe the dual symmetry of two-dimensional anisotropic media, we used generalized linear transformations of rotation:

In the transformed system, primed Ohm’s law also has a tensor form. It is more convenient to reformulate the problem described above using complex variables with the imaginary unit as the local rotation by the angle . It means that we used the following notations:

and complex conductivity [

9,

10]:

After applying transformations (4), the relations between the components of the initial and primed systems in the general case are:

In the case of capacitors and inductors:

, or

Let’s apply this method to study the many-component disordered system, consisting of randomly connected inductance of L and capacitance of C,

There are three possible symmetry transformations, corresponding to permutations of the different component types and the corresponding duality relations for the effective conductivity [

17].

1) First permutation symmetry of the system: an interchange of reactance components with odd and even numeration by positions:

2) The second symmetry of the system: an interchange of reactances with odd and even numeration in its positions and change of the direction of normal vector as:

3) The third symmetry of the system: the only change of the direction of normal vector as

Here, the coefficients are determined by the conditions (3).

In this case, the primed system is macroscopically equivalent to the original and as a result the effective conductivity has determined by the equation:

References

- Berezinskii, V. L. (1971), “Destruction of long-range order in one-dimensional and two-dimensional systems having a continuous symmetry group I. Classical systems”, Sov. Phys. JETP, 1971, 32 (3), P. 493–500, Bibcode:1971JETP...32..493B.

- M. Kosterlitz and D. Thouless, “Long Range Order and Metastability in Two-Dimensional Solids and Superfluids, Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics, 1972, V. 5, Number 11, L124.

- Kosterlitz, J. M.; Thouless, D. J. “Ordering, metastability and phase transitions in two-dimensional systems”. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics. 1972, 6 (7), P. 1181–1203. Bibcode:1973JPhC....6.1181K. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Thouless, Mahito Kohmoto, MP Nightingale, M Den Nijs, Quantized Hall Conductance in a Two-Dimensional Periodic Potential, Physical Review Letters, 1982, 49(6):405.

- D. Khmeľnitskiĭ, Localization in a Field of a Two-Dimensional Random Potential, JETP Letters, 1983, Vol. 38, Issue 9, pp. 454-457.

- Shelby R. A., Smith D. R., Schultz, S., Experimental Verification of a Negative Index of Refraction. Science. 2001,292 (5514): 77-79. [CrossRef]

- Pendry John B., Negative Refraction. Contemporary Physics. 2004, 45: 191–202. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Dykhne, Conductivity of a Two-Dimensional Two-Phase System, JETP, 1970, Vol. 59, p. 110-113.

- A.M. Dykhne, Anomalous plasma resistance in a strong magnetic field, JETP, 1970, Vol. 59, pp. 641-647, 1970.

- V.E. Arkhincheev, On fixed points, invariants of Dykhne’s transformations and stability of solutions…, Letters to Journal of experimental and theoretical physics, 1998. V. 67. P. 951-958.

- D.J. Thouless, Quantization of particle transport. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 6083. [CrossRef]

- F.D.M. Haldane, Nonlinear Field Theory of Large-Spin Heisenberg Chains and Topologically Invariant ‘θ-Vacua. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 1153.

- F.D.M. Haldane, Nonlinear Field Theory of Large-Spin Heisenberg Antiferromagnets: Semiclassically Quantized Solitons of the One-Dimensional Easy-Axis Néel State, Phys. Lett. A, 1983, 93, 464 passing through the real point.

- V.E. Arkhincheev, Quantum Hall effect in inhomogeneous media: Effective characteristics and local current distribution, Journal of experimental and theoretical physics, 2000, V. 118. P.465-474.

- V.G. Boltyanskki, V.A. Efremovich, Visual topology, Мoscow: Science, 1982 (Kvant Library, Issue 21).

- V. I. Arnold, Topological invariants of algebraic functions. II, Function. Analysis and its Appendices, 1970, Volume 4, Issue 2, 1-9.

- S.E.Korshunov, Topologic transitions in superconductors, Uspekhi fizicheskih nauk, 2006, 176 №3, P.233-272.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).