Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

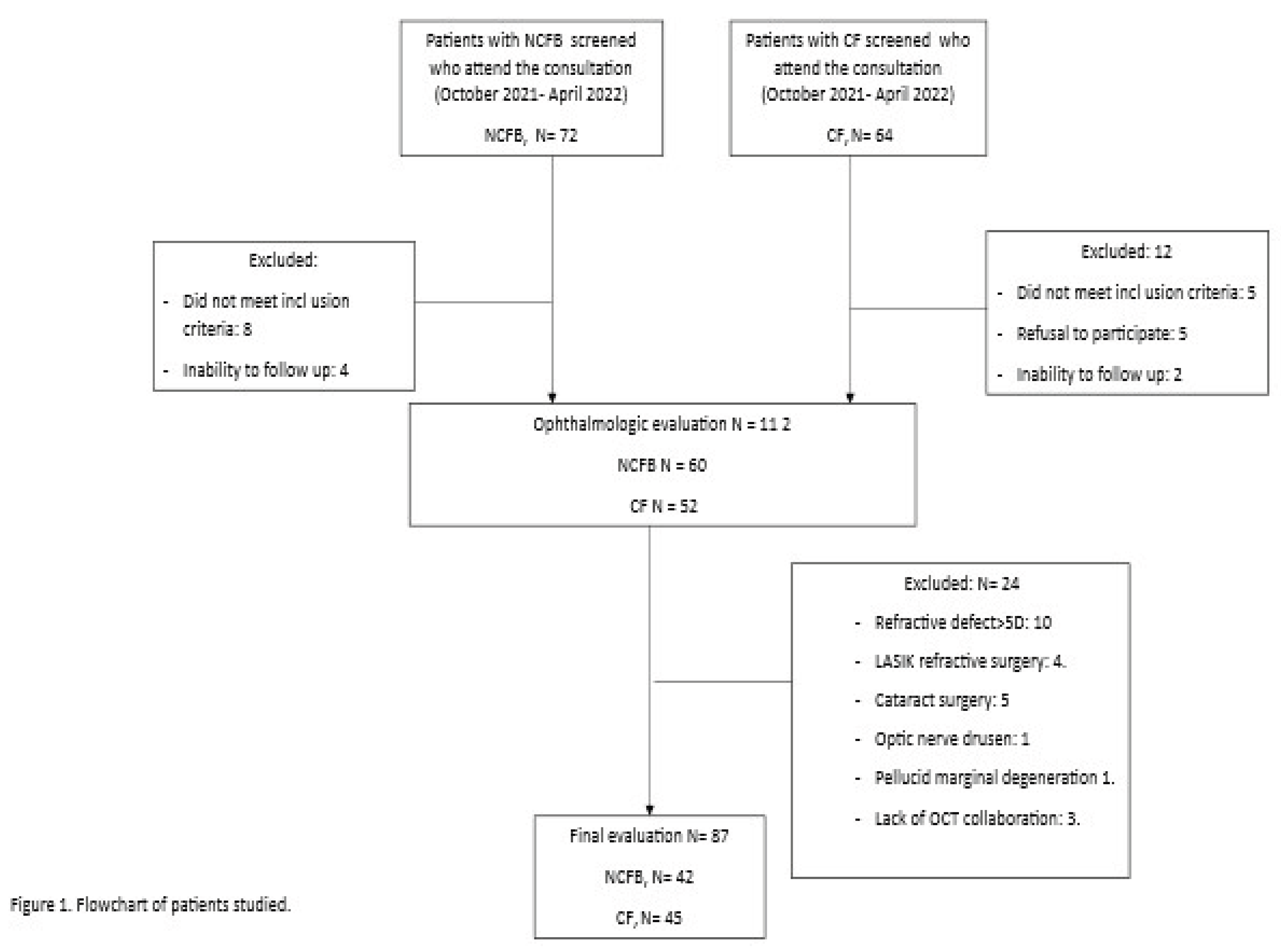

Study Design and Population

Pulmonary Evaluation: Clinical, Functional, Radiological, and Analytical Variables

Ophthalmologic Evaluation. Anatomical and Functional Variables

Statistical Analysis

Severity Scores

Results

Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quiroga-Garza, M.E.; Ruiz-Lozano, R.E.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, L.A.; Khodor, A.; Ma, S.; Komai, S.; et al. Lessons Learned From Ocular Graft versus Host Disease: An Ocular Surface Inflammatory Disease of Known Time of Onset. Eye Contact Lens. 2024, 50, 212–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Deokar, K.; Sinha, B.P.; Keena, M.; Desai, G. Ocular manifestations of common pulmonary diseases: a narrative review. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis Arch Monaldi Mal Torace. 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, P.; Jiménez, L.; Martínez, J.; Alba, C.; Girón, M.V.; Olveira, G.; et al. Dry eye disease and morphological changes in the anterior chamber in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2025 Jan 7;S1569-1993(24)01860-5.

- Huang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Liao, T.; Xiao, X.; et al. Association between asthma and dry eye disease: a meta-analysis based on observational studies. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e045275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, V.S.R.R.; Patel, V.K.; De Rubis, G.; Paudel, K.R.; Gupta, G.; Chellappan, D.K.; et al. Exploring the role of the ocular surface in the lung-eye axis: Insights into respiratory disease pathogenesis. Life Sci. 2024 Jul 15;349:122730.

- Choi, H.; McShane, P.J.; Aliberti, S.; Chalmers, J.D. Bronchiectasis management in adults: state of the art and future directions. Eur Respir J. 2024, 63, 2400518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.F.; Karamooz, E. Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Olivas JD, Oscullo G, Martínez-García MÁ. Etiology of Bronchiectasis in the World: Data from the Published National and International Registries. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 5782.

- Doumat, G.; Aksamit, T.R.; Kanj, A.N. Bronchiectasis: A clinical review of inflammation. Respir Med. 2025 Aug;244:108179.

- Wang, X.; Olveira, C.; Girón, R.; García-Clemente, M.; Máiz, L.; Sibila, O.; et al. Blood Neutrophil Counts Define Specific Clusters of Bronchiectasis Patients: A Hint to Differential Clinical Phenotypes. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HGrasemann y, F. Ratjen, «Cystic Fibrosis», N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 389, n.o 18, pp. 1693-1707, 2023,.

- Mall, M.A.; Burgel, P.R.; Castellani, C.; Davies, J.C.; Salathe, M.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L. Cystic fibrosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COlveira «Inflammation Oxidation Biomarkers in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: The Influence of, A.z.i.t.h.r.o.m.y.c.i.n.; et al. COlveira et al «Inflammation Oxidation Biomarkers in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: The Influence of, A.z.i.t.h.r.o.m.y.c.i.n.».; Eurasian, J. Med., vol. 49, n.o 2, pp. 118-123, jun. 2017.

- Schäfer, J.; Griese, M.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Hartl, D. Pathogenesis, imaging and clinical characteristics of CF and non-CF bronchiectasis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantin, A.M.; Hartl, D.; Konstan, M.W.; Chmiel, J.F. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease: Pathogenesis and therapy. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2015, 14, 419–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Villa, C.; Dobarganes, Y.; Olveira, C.; Girón, R.; García-Clemente, M.; et al. Systemic Inflammatory Biomarkers Define Specific Clusters in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Large-Cohort Study. Biomedicines. 2022, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarogoulidis, P.; Papanas, N.; Kioumis, I.; Chatzaki, E.; Maltezos, E.; Zarogoulidis, K. Macrolides: from in vitro anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties to clinical practice in respiratory diseases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, M.A.; Davies, J.C.; Donaldson, S.H.; Jain, R.; Chalmers, J.D.; Shteinberg, M. Neutrophil serine proteases in cystic fibrosis: role in disease pathogenesis and rationale as a therapeutic target. Eur Respir Rev. 2024, 33, 240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Metersky, M.; Aliberti, S.; Morgan, L.; Fucile, S.; Lauterio, M.; et al. Neutrophilic inflammation in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir Rev. 2025, 34, 240179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A.K.; Nelson, E.J.R. Role of innate immunity and systemic inflammation in cystic fibrosis disease progression. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, E.A.; Nichols, D.P.; Chmiel, J.F. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis: An update. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018 Nov;53(S3):S30–50.

- Felix, C.M.; Lee, S.; Levin, M.H.; Verkman, A.S. Pro-Secretory Activity and Pharmacology in Rabbits of an Aminophenyl-1,3,5-Triazine CFTR Activator for Dry Eye Disorders. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017, 58, :4506–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakouras, P.; Kanakis, M.; Diamantea, F.; Tzetis, M.; Koutsandrea, C.; Papaconstantinou, D.; et al. Ophthalmologic manifestations of adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021 Apr 8;11206721211008780.

- Ozarslan Ozcan, D.; Kurtul, B.E.; Ozcan, S.C.; Elbeyli, A. Increased Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Levels in Patients with Dry Eye Disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022, 30, 588–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Ganesan, K.; Shi, G. Identification of inflammatory markers as indicators for disease progression in primary Sjögren syndrome. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2024, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba-Linero, C.; Rodriguez Calvo De Mora, M.; Lavado Valenzuela, R.; Pascual Cascón, M.; Martín Cerezo, A.; Álvarez Pérez, M.; et al. Ocular surface characterization after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A prospective study in a referral center. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association, «World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects», JAMA, vol. 310, n.o 20, pp. 2191-2194, nov. 2013,.

- P. T et al., «C-Reactive Protein Concentration in Steady-State Bronchiectasis: Prognostic Value of Future Severe Exacerbations. Data From the Spanish Registry of Bronchiectasis (RIBRON)», Arch. Bronconeumol., vol. 57, n.o 1, ene. 2021.

- J. Roca et al., «Spirometric reference values from a Mediterranean population», Bull. Eur. Physiopathol. Respir., vol. 22, n.o 3, pp. 217-224, 198.

- PAgarwala y, S.H. Salzman, «Six-Minute Walk Test: Clinical Role, Technique, Coding, and Reimbursement», Chest, vol. 157, n.o 3, pp. 603-611, mar. 2020.

- M. Bhalla et al., «Cystic fibrosis: scoring system with thin-section CT», Radiology, vol. 179, n.o 3, pp. 783-788, jun. 1991.

- DB Reiff, A. U. Wells, D. H. Carr, P. J. Cole, y D. M. Hansell, «CT findings in bronchiectasis: limited value in distinguishing between idiopathic and specific types», Am. J. Roentgenol. 1976, vol. 165, n.o 2, pp. 261-267, 1995.

- Directrices para el envío de especímenes a los laboratorios clínicos para el diagnóstico biológico. 2009.

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Arita, R.; Chalmers, R.; Djalilian, A.; Dogru, M.; Dumbleton, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017, 15, 539–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RM Schiffman, M. D. Christianson, G. Jacobsen, J. D. Hirsch, y B. L. Reis, «Reliability and Validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index», Arch. Ophthalmol., vol. 118, n.o 5, pp. 615-621, may 2000,.

- AJ Bron, V. E. Evans, y J. A. Smith, «Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests», Cornea, vol. 22, n.o 7, pp. 640-650, oct. 2003.

- RSambursky, W.F. Davitt, M. Friedberg, y S. Tauber, «Prospective, multicenter, clinical evaluation of point-of-care matrix metalloproteinase-9 test for confirming dry eye disease», Cornea, vol. 33, n.o 8, pp. 812-818, ago. 2014.

- Messmer, E.M.; von Lindenfels, V.; Garbe, A.; Kampik, A. Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Testing in Dry Eye Disease Using a Commercially Available Point-of-Care Immunoassay. Ophthalmology. 2016, 123, 2300–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Bonaccio et al., «A score of low-grade inflammation and risk of mortality: prospective findings from the Moli-sani study», Haematol. Roma, vol. 101, n.o 11, pp. 1434-1441, 2016.

- Martínez-García, M.A.; Olveira, C.; Máiz, L.; Girón RMa Prados, C.; de la Rosa, D.; et al. Bronchiectasis: A Complex, Heterogeneous Disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019, 55, 427–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Clemente, M.; de la Rosa, D.; Máiz, L.; Girón, R.; Blanco, M.; Olveira, C.; et al. Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection on Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Airway Diseases. J Clin Med. 2020, 9, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Nelson, J.D.; Azar, D.T.; Belmonte, C.; Bron, A.J.; Chauhan, S.K.; de Paiva, C.S.; Gomes, J.A.P.; Hammitt, K.M.; Jones, L.; Nichols, J.J.; Nichols, K.K.; Novack, G.D.; Stapleton, F.J.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Wolffsohn, J.S.; Sullivan, D.A. TFOS DEWS II Report Executive Summary. Ocul Surf. 2017, 15, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalwani, A.Y.; Hafez, S.Y.; Alsubaie, N.; Rayani, K.; Alqanawi, Y.; Alkhomri, Z.; Hariri, S.; Jambi, S. Assessment of leukocyte and systemic inflammation index ratios in dyslipidemia patients with dry eye disease: a retrospective case‒control study. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Iruzubieta, J.; Sanchez Hernandez, M.C.; Dávila, I.; Leceta, A. The Importance of Preventing and Managing Tear Dysfunction Syndrome in Allergic Conjunctivitis and How to Tackle This Problem. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2023, 33, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Villa, C.; Dobarganes, Y.; Olveira, C.; Girón, R.; García-Clemente, M.; Máiz, L.; Sibila, O.; Golpe, R.; Menéndez, R.; Rodríguez-López, J.; Prados, C.; Martinez-García, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.L.; de la Rosa, D.; Duran, X.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Barreiro, E. Phenotypic Clustering in Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis Patients: The Role of Eosinophils in Disease Severity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.J.; Oscullo, G.; He, M.Z.; Xu, D.Y.; Gómez-Olivas, J.D.; Martinez-Garcia, M.A. Significance and Potential Role of Eosinophils in Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023, 11, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Fraga, J.; Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A.; Calonge, M.; González-García, M.J.; López-Miguel, A.; López-de la Rosa, A.; García-Vázquez, C.; Calder, V.; Stern, M.E.; Fernández, I. Severity, therapeutic, and activity tear biomarkers in dry eye disease: An analysis from a phase III clinical trial. Ocul Surf. 2018, 16, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Direct and indirect costs of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis to adults in Beijing, China. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022, 12, e12148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Soni, D.; Saxena, H.; Stevenson, L.J.; Karkhur, S.; Takkar, B.; Vajpayee, R.B. Impact of corneal refractive surgery on the precorneal tear film. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2804–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirfar, M.; Brown, A.H.; Sulit, C.A.; Corbin, W.M.; Ronquillo, Y.C.; Hoopes, P.C. Corneal Refractive Surgery Considerations in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator-Related Disorders. Int Med Case Rep J. 2022 Nov 9;15:647-656.

- Schneider-Futschik, E.K.; Zhu, Y.; Li, D.; Habgood, M.D.; Nguyen, B.N.; Pankonien, I.; Amaral, M.D.; Downie, L.E.; Chinnery, H.R. The role of CFTR in the eye, and the effect of early highly effective modulator treatment for cystic fibrosis on eye health. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2024 Nov;103:101299.

| All (N=87) | CF (n=45) | NCFB (n=42) |

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.5±10.5 | 33.4±9.7 | 40.5±11.6 | 0.003 | ||

| Gender, M, n (%) | 42 (48.3) | 25 (55.6) | 20 (47.6) | 0.459 | ||

| Height (cm) | 167.2±9.6 | 166.0±9.8 | 168.6±9.4 | 0.223 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 67.2±16.8 | 66.2±19.1 | 68.3±14.1 | 0.556 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8±5.1 | 23.7±5.8 | 24.0±4.4 | 0.741 | ||

| Total exacerbations in the previous year | 1.1±1.4 | 1.3±1.7 | 0.81±0.97 | 0.112 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median [IQR] | 1 [1-2] | 1 [1-2] | 1 [1-1] | 0.058 | ||

| Etiology of bronchiectasis, n (%) | - | |||||

|

- | - | 9 (21.4) | |||

|

- | - | 7 (16.7) | |||

|

- | - | 2 (4.8) | |||

|

- | - | 1 (2.4) | |||

|

- | - | 23 (54.8) | |||

|

||||||

|

- | 15 (33.3) | - | - | ||

|

- | 19 (42.2) | - | - | ||

|

- | 11 (24.4) | - | - | ||

|

||||||

|

62.4±24.7 | 56.7±23.4 | 68.5±24.9 | 0.025 | ||

|

70.4±19.3 | 66.5±19.4 | 74.5±18.5 | 0.055 | ||

|

84.9±16.4 | 81.6±15.5 | 88.4±16.8 | 0.053 | ||

|

97.0±1.9 | 96.9±2.0 | 97.2±1.9 | 0.534 | ||

|

94.4±4.5 | 94.0±4.6 | 95.0±4.4 | 0.244 | ||

|

0.0±1.0 | -0.4±1.0 | 0.4±0.8 | <0.001 | ||

|

||||||

|

4.6±4.3 | 5.3±5.0 | 3.8±3.3 | 0.101 | ||

|

16.0±5.4 | 14.8±6.2 | 17.3±4.1 | 0.029 | ||

|

||||||

|

7340.5±2120.2 | 7548±2438 | 7117.7±1717.5 | 0.347 | ||

|

56.8±10.5 | 55.4±12.0 | 58.3±8.5 | 0.197 | ||

|

3.4±2.6 | 3.7±2.8 | 3.1±2.3 | 0.271 | ||

|

51.7±43.1 | 48.2±32.6 | 55.1±51.6 | 0.495 | ||

|

352.0±100.0 | 327.2±90.0 | 368.7±104.4 | 0.144 | ||

|

9.1±14.3 | 9.5±14.1 | 8.6±14.7 | 0.794 | ||

|

134.4±27.8 | 138.3±27.8 | 129.7±27.4 | 0.162 | ||

|

43 (49.4) | 25 (55.6) | 18 (42.9) | 0.236 |

| All (N=87) | CF (n=45) |

NCFB (n=42) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.5±10.5 | 33.4±9.7 | 40.5±11.6 | 0.003 |

| Gender, Male, n (%) | 42 (48.3) | 25 (55.6) | 20 (47.6) | 0.459 |

| Sphere | -0.86±2.17 | -0.90±2.17 | -0.60±2.33 | 0.538 |

| Cylinder | -0.77±0.69 | -0.75±0.69 | -0.78±0.70 | 0.803 |

| Cylinder axis | 88.4±55.2 | 82.8±52.6 | 94.8±58.1 | 0.329 |

| SE | -1.1±2.17 | -1.17±2.16 | -1.10±2.21 | 0.868 |

| BCVA | 1.0±0.05 | 1.01±0.06 | 1.00±0.02 | 0.109 |

| IOP (mmHg) | 17.4±2.6 | 17.6±2.8 | 17.1±2.30 | 0.431 |

| T-BUT<10s, n (%) | 41 (47.1) | 25 (55.6) | 16 (38.1) | 0.103 |

| T-BUT (s) | 10 [8-20] | 9 [8-17.5] | 12.5 [6.75-20] | 0.043 |

| ST1<10, n (%) | 34 (39.1) | 18 (40.0) | 16 (38.1) | 0.856 |

| ST1 (mm) | 14 [8-21] | 11 [4.5-24] | 13,5 [6-23.25] | 0.750 |

| OSDI>13, n (%) | 21 (24.2) | 9 (20.0) | 12 (28.6) | 0.351 |

| Visual symptoms, n (%) | 0.033 | |||

|

59 (67.8) | 26 (57.8) | 33 (78.6) | |

|

23 (26.4) | 14 (31.1) | 9 (21.4) | |

|

5 (5.7) | 5 (11.1) | 0 (0) | |

|

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0(0) | |

|

1.32±0.62 | 1.33±0.64 | 1.31±0.60 | 0.859 |

|

21 (24.1) | 11 (24.4) | 10 (23.8) | 0.945 |

|

- | 24 (60) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).