Introduction

In August of this year, the newspaper Folha de SP filed a lawsuit against OpenAI so that the company responsible for developing ChatGPT stopped collecting and using, without authorization and payment, the vehicle's content

1. The action of the Brazilian daily repeated the American The New York Times which, in 2023, took the same measure. In the case of The Guardian, the fight turned into a partnership. After appealing to the courts two years ago against the developer of ChatGPT, the newspaper signed a contract with OpenAI to, according to the technology company, bring "high-quality journalism to global ChatGPT users from The Guardian's editorial content".

2

The difficulties of large outlets in not knowing how to deal with the effects promoted by AI companies in journalistic activity are also present within newsrooms. While the management of the outlets fears further loss of revenue and audience, journalists express enthusiasm about the use of AI in their routines, as well as concerns about algorithm biases, risks of loss of editorial autonomy, job closures (Cools and Vreese 2025; Sangyon and Jaemin 2025; Cools and Diakopoulos 2024). In a public letter, Financial Time columnist Rana Foroohar recently expressed concern about the agreement reached between the newspaper and OpenAI to train AI models of the technology company from the content generated by the FT: "I am very skeptical that AI will seriously benefit anyone other than Big Tech in the short and medium term" (Foroohar, 2025).

The current scenario of the uses of AI reflects what we can call a technological paradox of journalism. Historically, this activity held dominance over the technical apparatuses that supported its practice – such as the printing press, in the case of the printed newspaper, and electromagnetic transmission, on radio and television. These technologies not only enabled the production and dissemination of content, but also contributed to the consolidation of a professional, institutional and commercial field.

With digital technologies, this scenario is radically transformed: most of the technological apparatus of communication now belongs to another economic sector, led by large technology companies, with their own logics and interests. The decoupling between journalistic activity and the control of its technical infrastructure generates internal tensions and divergent views on the consequences for this professional activity and for the informational environment.

Essentially, the paradox is constituted by a perspective that digital innovations represent a revitalizing opportunity, which would allow journalism to reinvent itself, as a practice, institution and business. The same technological revolution implies profound challenges and structural threats to journalism. The precariousness of journalistic work, the dependence on large digital platforms, the difficulty of monetization in the face of the "zero marginal cost" of information, and the amplification of disinformation are some of the latent concerns, which would manifest themselves in the tension between a look at innovation and another at the risks and challenges that still persist (De-Lima-Santos and Salaverría 2021; Salaverría 2019; Bell and Owen 2017).

This dynamic forces a redefinition of the boundaries and institutional role of journalism, requiring professionals to have new skills to work in a media ecosystem increasingly dominated by algorithms and large technology companies, which in turn generates anxiety and fear of replacement in some newsrooms (Deuze and Witschge, 2017; Ekström and Westlund 2019). Not only risks, but also profound changes in professional culture driven by choices and decisions in the processes of production and distribution of information that take into account the use of new technologies (Ekström, Ramsälv and Westlund 2022).

The well-documented context of the technological paradox demonstrates, in this sense, the need for a better understanding of how journalists, urged to use more and more digital technologies, reflect this tension. This is an important analytical key, but still little explored. Journalists' perceptions legitimize decisions and professional choices that can both accelerate the use of digital technologies controlled by big techs, and that transform the activity and institutional role of journalism, and can be a factor with the potential to guide alternative paths of less dependence or, in the last case, with innovations specific to the sector (Wu and Jiajia 2024).

It is essential, therefore, to examine how these professionals perceive the innovation landscape. What factors can be mobilized to explain the way in which journalists evaluate the relationship with digital technology? Is it possible to speak of a technological paradox present in the perceptions of these professionals? To answer these questions, this article uses Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to map explanatory dimensions adopted by a group of journalists in Brazil about the relationship of these professionals with digital technology. To this end, we applied a survey (n=230) in 2023 to assess habits and perceptions about the use of technologies in work routines, as well as evaluations of the relationship with big techs. From the data, we developed CFA and EFA tests to identify the factors.

Next, we examine three issues. The first of them sought to verify the existence of latent factors that could reasonably explain the set of journalists' perceptions in relation to technologies. The second evaluated the predominance of a more optimistic than critical view of the use of technologies and, finally, a last one verified the internal consistency of the critical dimension presented by journalists in relation to digital technologies.

The results are promising because they illustrate an analytical dimension that is still little examined about the transformations that journalism is going through, especially in the Brazilian context, in the face of innovations in digital technology. Although it is a study with limitations, since the results cannot be extrapolated beyond the sample used, the tests identify the existence of two distinct factors that guide the way in which the technological paradox is organized among journalists. This evidence can support new studies on the impacts of technologies in the journalistic field, especially by presenting an empirical map through which press professionals elaborate their choices in the face of the digital transformation scenario.

Two Paradigms

The emergence of an optimistic paradigm about the effects of technology in the journalistic field, especially in the digital age phase, has been driven by a series of studies in the last three decades that have mapped the process of adaptation of professional practices and the business model of media companies in the face of digital transformation. From this perspective, alignment with new technological and communicational frontiers was pointed out both as a crucial point for survival and professional relevance, as well as a chance to expand the capabilities offered by digital platforms and other technological innovations (Nilsen and Ganter 2022; Pavlik 2013; Anderson, Bell and Shirky 2012).

While these studies acknowledge the negative impacts on journalism funding, most of them argue that digital platforms are essential distribution channels that allow journalistic content to reach vast global audiences, with very low replication costs, through "overdistribution" (Bell and Owen 2017; Anderson, Bell and Shirky 2012). The low cost of production and distribution has driven, in this sense, the emergence of digital native media, including non-profit organizations and specialized vehicles, which explore new sources of revenue, such as subscription models, paywalls, and crowdfunding (DalBen 2020; García-Orosa, López-García and Vázquez-Herrero 2020; Anderson, Bell and Shirky 2012). This diversification of funding modes offered greater editorial autonomy compared to traditional models based exclusively on advertising (García-Orosa, López-García, and Vázquez-Herrero 2020).

López-García and Gutiérrez-Caneda (2024) observe, for example, that high-tech journalism is already a reality that defines the debate on innovation, requiring the sector to continuously adapt and anticipate the future for its permanence. Automated journalism, employing software and algorithms, in this sense, is part of this process and has the potential to free journalists from repetitive and low-complexity tasks (DalBen 2020; Anderson, Bell and Shirky 2012). Additionally, the intensive use of technology would not impact trust in journalism. Wölker and Powell (2018) argue that the perceived credibility of the source in automated or combined journalistic articles is similar to that of human articles, which would suggest a promising acceptance of these technologies by the audience.

Digital transformation, from this perspective, has benefited journalism, increasing efficiency and productive capacity. Professionals present new possibilities to carry out more complex and interpretive activities (Whittaker 2019). The analysis of large volumes of data, or big data, through data journalism and Artificial Intelligence tools, expands the possibilities of in-depth investigations, the crossing of information, and the identification of patterns that would be unfeasible for human capacity (DalBen 2020; Cheruiyot, Baack and Ferrer-Conill 2019; Palomo, Teruel and Blanco-Castilla 2019; De-Lima-Santos and Salaverría 2021). Studies such as Ureta, Fernández, and Sjøvaag (2023) reinforce this perspective, highlighting the effervescence of AI research that predicts new options for the flow of news, collection, and distribution of content, adapting the epistemology of the profession itself.

Collaboration and engagement with the audience are also relevant strategic axes in the digital age scenario. This environment favors new forms of collaborative work, whether internally in newsrooms, with multidisciplinary teams that include programmers and data analysts, or externally with the participation of individuals, collectives, and other organizations (DalBen, 2020; Anderson, Bell, and Shirky, 2012; García-Orosa, López-García and Vázquez-Herrero, 2020). Crowdsourcing and citizen journalism, for example, make it possible to collect and verify information in real time and from different sources.

The relevance of audience knowledge is underlined by Corzo and Salaverría (2019), who analyze how web analytics influences the construction of news in digital native media, allowing a strategic adaptation of content to the needs of the audience. Digital platforms would also promote an unprecedented level of audience engagement, allowing direct interaction, feedback, and the co-creation of content that would respond to users' needs (DalBen, 2020; García-Orosa, López-García, and Vázquez-Herrero, 2020; Bell and Owen, 2017). In this context of technological transformation, the role of the journalist evolves into that of curator and contextualizer of the content generated by the public, adding journalistic value (Anderson, Bell, and Shirky, 2012).

For Steensen and Westlund (2021), the discourse marked by technological optimism presents analytical weaknesses. The first of these is the tendency towards technological determinism, which presupposes a direct causal relationship between technology and journalistic practice, attributing to technology the central and inevitable role of transforming agent. This technology-centric approach can obscure other relevant factors influencing changes in journalism. The second limitation is the overvaluation of skills and technological resources, suggesting that such skills are more determinant than they are actually shown in the daily practice of journalists. And finally, this discourse is based on the assumption that every new technology will necessarily bring benefits to journalism — a premise that deserves to be questioned based on empirical evidence.

Although focused on the technological perspective, the era of digital innovation has also raised a critical face in the specialized literature, revealing negative impacts on journalism. One of the points addressed suggests that the dominance of platforms and algorithms has led journalism to a reconfiguration of its role, its structure and its own sustainability, often to the detriment of its traditional values and civic relevance (Bell and Owen, 2017; Christofoletti, 2025; Anderson, Bell and Shirky, 2012). One of the most salient impacts is the sharp financial deterioration of newspaper companies. The internet, and in particular big techs like Alphabet/Google and Meta/Facebook, have disintegrated the traditional advertising-based business model by centralizing vast portions of ad revenue online.

The hope that digital advertising, driven by a vast number of users, could fund quality journalism proved to be an illusion, as revenue remains concentrated on the platforms (Bell and Owen, 2017). In addition, the spread of free services through platforms has created a mentality in the public that information should not be paid for, harming subscriber bases and the willingness of new generations to pay for journalism. The non-remuneration of journalistic companies and journalists for the use and republication of their content on the platforms further aggravates this financial crisis (Christofoletti, 2025).

Technology also causes a significant loss of institutional value and editorial control by news organizations. Digital platforms have progressively assumed the role of publishers, controlling the audience, determining what is seen, and even influencing journalistic formats and genres that "take off". This transfer of content to third-party platforms often occurs with no guarantee of financial return, resulting in brand dilution, lack of access to audience data, and migration of advertising revenue (Bell and Owen, 2017). The opacity of the platforms' algorithms prevents effective strategic planning and grants disproportionate control over the distribution of information. Ultimately, the act of publishing, hosting, and monetizing content may cease to be a core activity of news organizations.

In addition, credibility and public trust in journalism are eroded by the digital ecosystem. By prioritizing the viralization of content — without correlation with journalistic quality — platforms become fertile ground for the proliferation of fake news and misinformation. Journalism with civic value, which checks those in power, is passed over for a system that values scale and shareability" (Bell and Owen, 2017). Algorithmic filtering reinforces "filter bubbles", isolating users in environments where they only accept information that corroborates their beliefs, regardless of its veracity, undermining public discourse based on common narratives and accepted truths (Pariser, 2012; Whittaker, 2019).

Technology also directly impacts journalistic practices and the professional health of journalists. The automation of routine and low-complexity tasks, although seen as efficiency, generates anxiety and the fear of replacement by robots, especially in newsrooms that lack programmers and an in-depth understanding of human-machine interaction (DalBen, 2020; Anderson, Bell, and Shirky, 2012). Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt (2019) point to a significant theoretical gap, where the machine as a communicative source in automated journalism does not receive adequate attention, complicating the fundamental questions about the interaction between humans and news in a field dominated by anthropomorphic models.

In the platformized scenario of communication, the role of the journalist migrates from primary producer to curator and contextualizer of a deluge of information generated by the public, changing the essential function of reporting and requiring new "hard skills" in data and programming, often neglected in training. The pressure to generate traffic from an incessant search for attention from the transient public with flashy publications leads to the waste of money on redundant activities (Anderson, Bell, and Shirky, 2012).

Journalism's growing reliance on social media intermediation is therefore seen as a point of great concern. Nielsen and Ganter (2018) draw attention to the fact that journalistic companies adhere to the logic of networks without measuring the risks of the asymmetric relationship with digital platforms. The phenomenon of the "platformization of journalism", which consists of the search for the commodification of content oriented to circulate on platforms controlled by big techs and their algorithms, is now a reality (Poell; Nieborg, 2020; Silva et al., 2020, Van Dijck; Poell; Waal, 2018). The relationship with big techs is quite unequal, since the platforms have established a dominant position in the attention economy, controlling the distribution of content and audience monetization, directly affecting the advertising business model of traditional journalism (Ramírez 2021).

In summary, this set of studies brings evidence of technological paradox. At the same time that digital transformation is pointed out as a solution for journalism, with more diversification, new skills and opportunities, on the other hand, the negative impacts on journalism are well documented.

The Perception of Journalists

With fewer resources to subsidize its business and increasingly part of a scenario in which digital technologies have become an element of daily life, journalism is today faced with a difficult choice between an adhesion that can result in more losses of space and economic and social value, or an adaptation in which it can preserve its activity, without renouncing the gains from the use and application of these technologies.

From this perspective, a significant set of studies has sought to map journalists' perceptions of the impacts or uses of a diversity of technologies, with findings that contribute to a better understanding of the issue. Among these topics, how journalists see the use of Artificial Intelligence and automation stands out (Cools and Claes 2025; Sangyon and Jung 2025; Wang et al., 2024; De Lima-Santos et al, 2024; Cools and Diakopoulos 2024; Belair-Gagnon 2023; Wu et al. 2018); the impact of audience metrics and market pressures (Ekström, Ramsälv and Westlund 2022; Pithan et al. 2020; Belair-Gagnon et al. 2020; Belair-Gagnon, Zamith and Holton 2020).

Other topics also present in studies that analyze the perception of journalists evaluated the uses and effects of technologies on professional culture and journalistic identity (Christofoletti, 2019; Belair-Gagnon, Zamith and Holton 2020; Träsel 2014); innovation, sustainability and business models (De-Lima-Santos et al. 2022; Westlund et al. 2020) in addition to the relationship of journalists with audiences (Ekström, Ramsälv and Westlund 2022; Coddington et al. 2021; Cunha 2020).

Although they are focused on the perceptions of professionals, this set of studies tends to map the use or effects of a specific technology, such as AI, the application of metrics, and the relationship with social networks. Despite identifying in their findings the positive and negative dimensions of the relationship between journalism and digital technologies, there remains, in our view, a gap that consists of an aggregate understanding of journalists' perception of technologies and that considers the paradox of their effects, as much of the literature has been pointing out in the last 30 years.

In our view, this is a relevant key to understanding how journalists have or have not adhered to the most optimistic paradigm of the use and application of technologies, many of them produced and controlled by large technology companies. In this sense, this research is aligned with the notion that journalists' perception of technology is not one-dimensional, but composed of different attitudes that can both reflect enthusiasm due to efficiency gains and opportunities, and a more critical view, which dialogues with the risks and concerns about the consequences of uses and interactions with technologies and companies in this sector. But how are these dimensions organized and to what extent do they differ?

In this context, this study examines three questions:

Q1: Do journalists present latent factors about the effects of technologies?

Q2: Do journalists assign different weights to these latent factors?

Q3: Are there differences in the internal cohesion of these factors?

The examination of these questions offers not only evidence for a deeper discussion of the interaction between journalists and technology, but, above all, for discussing, at an aggregate level, the technological paradox of journalism. As noted, this paradox consists of the widespread view that journalism needs to adapt to technologies controlled by big techs, which, in turn, are pointed out as the main factor with negative impacts on the journalistic field. The way in which the beliefs and perceptions of the professional field dialogue with these dimensions is a fundamental point and should be better examined.

Methodology

The data used in this research was collected between February 5 and April 30, 2023, through an online questionnaire directed to journalists' groups on WhatsApp, as well as from calls on social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter (today, X). In these two channels, participants were asked to share in other groups of journalists. At the end of the three months of collection, 230 respondents who declared themselves journalists participated. To participate, the respondent had to identify himself with an e-mail account and name, information used to control possible duplications in the answers.

The questionnaire presented a battery of 27 questions, organized into three groups: 1- Characteristics of the respondent, 2- Uses of Technology and 3- Perceptions. The first sought to map the participant's profile, such as age, state, gender, color/race, and size of the organization for which they worked. The Perceptions group, which is the basis of this article, brought a set of ten statements in which journalists presented answers on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All the data of the questionnaire answers were automatically stored in an electronic spreadsheet. After the end of data collection on April 30, two variables were reclassified.

Table 1.

Sample Profile.

| Gender |

N |

% |

| Male |

129 |

56 |

| Female |

100 |

44 |

| Total |

229 |

100 |

| Age group |

N |

% |

| Up to 20 years |

8 |

3,4 |

| 20 to 30 years |

67 |

29,1 |

| 30 to 40 years |

60 |

26 |

| 40 to 50 years old |

45 |

19,5 |

| More than 50 years |

50 |

21,7 |

| Total |

230 |

100 |

| Region |

N |

% |

| Midwest |

14 |

6,1 |

| Northeast |

69 |

30,1 |

| North |

2 |

0,9 |

| Southeast |

133 |

58,1 |

| South |

11 |

4,8 |

| Total |

229 |

100 |

In the study, we adopted the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), we used the answers on a Likert scale of 10 questions of the questionnaire that sought to measure the level of agreement and disagreement of journalists in various aspects of the relationship with the uses of technology or interactions with large technology companies. Three questions (Q19, Q20 and Q22) had the answer scale inverted, so that the semantic direction of the utterance corresponded to the positive meaning.

Table 2.

Summary table of questions and adjustments.

Table 2.

Summary table of questions and adjustments.

| Question |

Question wording (answers on the Likert scale 1=Strongly Disagree to 5=Strongly Agree) |

Semantic direction |

Scale adjustment |

| Q18 |

Technology is an ally of journalism, with the potential to transform this activity, making it more efficient and creative. |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q19 |

Technology tends to reduce journalistic independence, limiting the work of professionals because it is oriented towards the search for an audience, without a focus on creativity |

Refusal |

Inverted |

| Q20 |

Big techs (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple) do more harm to journalism than good |

Refusal |

Inverted |

| Q21 |

Big techs are an opportunity to finance journalism |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q22 |

The idea of what is news has changed for the worse after the internet and the emergence of social networks |

Refusal |

Inverted |

| Q23 |

The use of robots in the production of journalistic texts brings more advantages than disadvantages |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q24 |

As everyone is hit by a lot of information on a daily basis because of the intense use of social networks, it is up to contemporary journalism to focus on analyzing and producing in-depth reports |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q25 |

The journalistic activity (production and editing of content) must now also be concerned with the business strategies of the journalistic organization (boosting audience, seeking new subscribers, promoting events that attract advertisers) |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q26 |

The journalist must be multidisciplinary and willing to learn other areas of knowledge such as technology, leadership, sales and business |

Positive |

Maintained |

| Q27 |

The use of algorithms by journalistic organizations should be a priority because it helps in the production and dissemination of content |

Positive |

Maintained |

Data Analysis

The first test of this study consisted of verifying whether there was sufficient correlation in the matrix composed of the ten questions used in the analysis, in order to allow us to continue with the application of factor analysis. For this, the Bartlett sphericity test was used. The result presented a p-value lower than 0.0001, indicating significant correlations, thus validating the analysis.

Next, we applied the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) test to verify the adequacy of the sample for factor analysis, that is, to evaluate the degree of partial correlation between the items of the scale so that it is possible to group them into factors. The index ranges from 0 to 1, with values above 0.6 being considered acceptable, while values above 0.7 indicate good adequacy. In the test, the value obtained reached 0.708, suggesting that the data present sufficient correlations to justify the application of factor analysis.

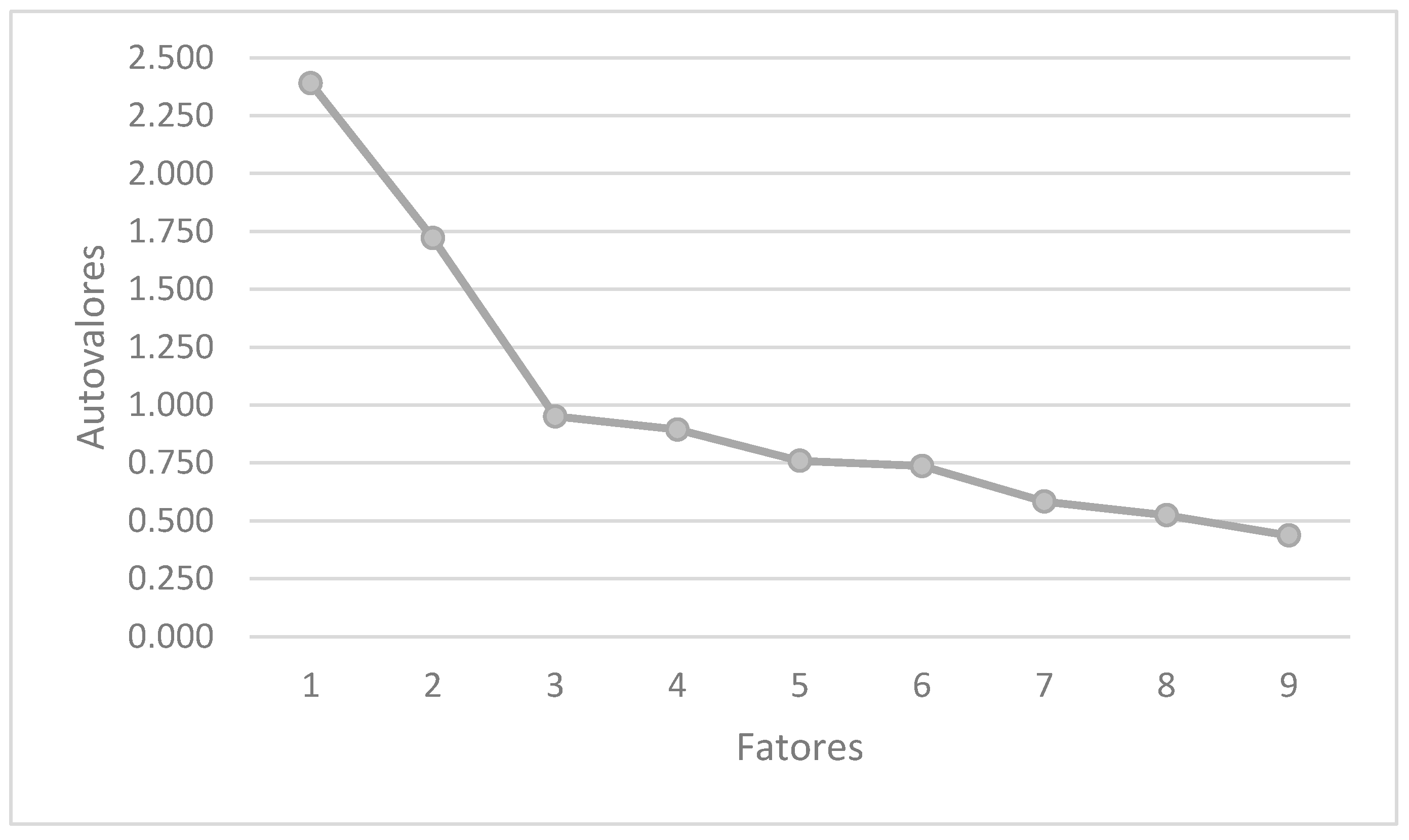

Next, we identified the latent structure of the scale items, using the eigenvalues-based extraction method. The procedure consists of adjusting the factorial model to the data and extracting the eigenvalues of each component. The results indicated the existence of eigenvalues higher than 1 — specifically 2.39 and 1.72 — which, according to Kaiser's criterion, would justify the retention of two main factors. In other words, these two factors explain a significant proportion of the total variance of the data, while the others presented values lower than 1, suggesting that they do not contribute substantially to the latent structure.

Figure 1.

Extraction of eigenvalues. Source: the author.

Figure 1.

Extraction of eigenvalues. Source: the author.

The analysis of the factor loadings of each item, based on the oblimin rotational model, showed greater parsimony, i.e., explaining the data well with less complexity; conceptual clarity, in the sense that the factors represent two well-defined poles, and better adequacy of the load distribution, with the items grouped more consistently, with less ambiguity possible. During the tests, Q23 was excluded from the analysis because it presented strong ambivalence in the factor loading. Among the Factor 2 loads, Q18 showed less consistent force, below the limit of 0.400, even so, we decided to keep it, as we will discuss when analyzing the Cronbach tests.

With the questions and loads defined, we named Factor 1 as "Innovative and Strategic Journalism" considering questions 21, 24, 25, 26 and 27. This set of questions suggests a more enthusiastic perspective on the use or impact of technologies on journalistic practices. In this group are, for example, issues such as the perception of the relationship with big techs, the focus on the analysis and depth of journalistic production, in addition to business strategies, the need for multidisciplinarity and the use of algorithms. These are questions, therefore, that suggest a professional posture that identifies opportunities in the context of technological innovation.

With the set of questions defined by the factor loadings of Factor 2, in turn, we named this group as "Digital Skepticism". In this group, there are questions 18, 19, 20 and 22. These questions address a more critical view of the uses and impacts of technology in journalism, with questions about the idea of technology as an ally of journalism, journalistic independence, the losses generated in the performance of big techs and the negative view of the concept of news in the environment of digital networks.

Table 3.

Summary of factor loadings.

Table 3.

Summary of factor loadings.

| Question |

Summary of the statement |

Innovation and Strategy |

Digital Skepticism |

| Q18 |

Technology as an ally of journalism |

0.185 |

0.358 |

| Q21 |

Big techs as a funding opportunity |

0.400 |

0.165 |

| Q24 |

Focus on analysis and depth |

0.403 |

-0.230 |

| Q25 |

Business strategies in journalism |

0.706 |

-0.014 |

| Q26 |

Journalist's multidisciplinarity |

0.695 |

-0.096 |

| Q27 |

Priority in the use of algorithms |

0.649 |

0.156 |

| Q19 |

Technology limits journalistic independence |

0.055 |

0.515 |

| Q20 |

Big techs bring more harm than good |

0.017 |

0.487 |

| Q22 |

The idea of news has worsened with social networks |

-0.17 |

0.496 |

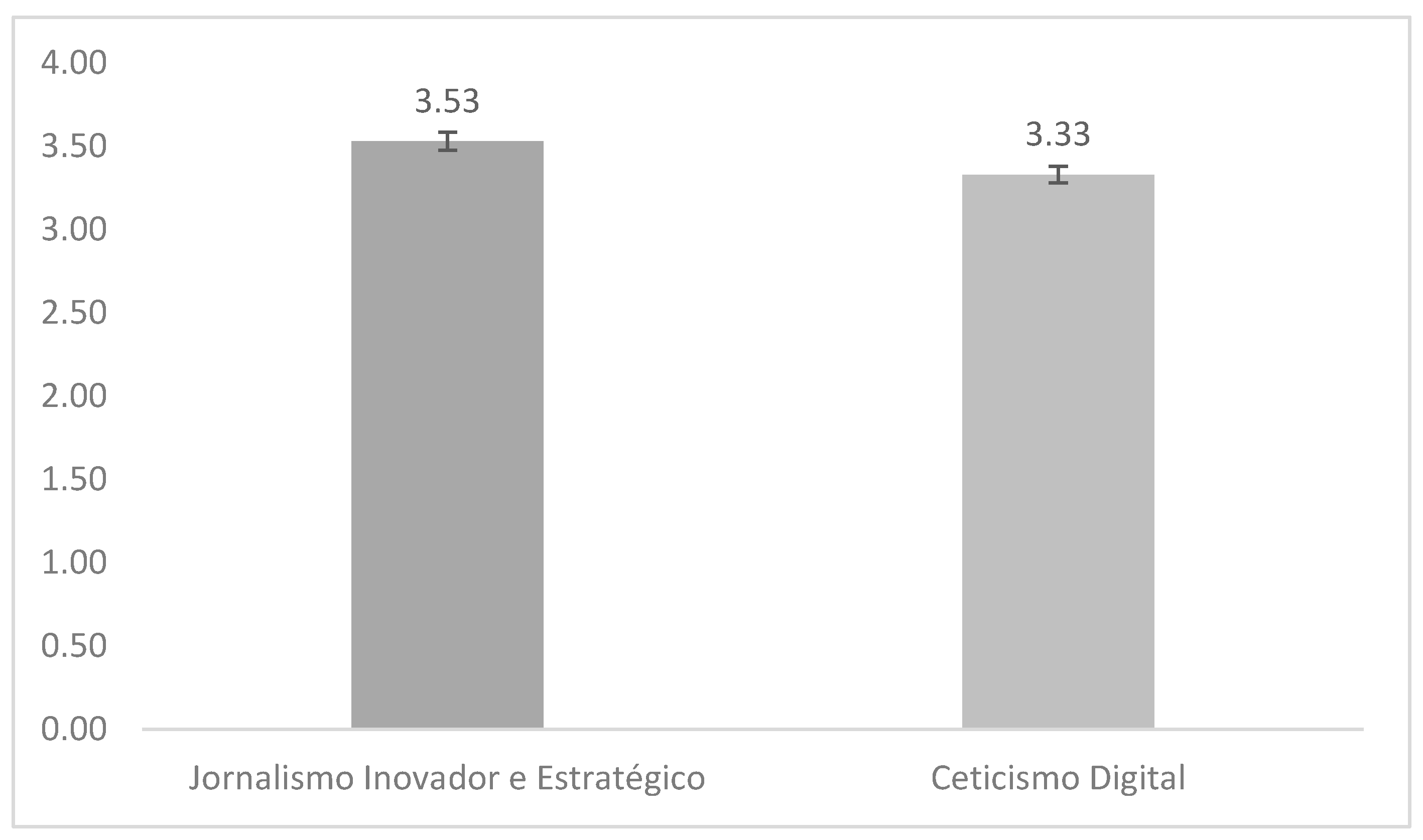

From the confirmed two-factor structure (Q1), we proceed to examine Q2, which investigates whether journalists attribute greater weight to one dimension to the detriment of the other. To this end, we performed the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess the normality of the factor scores. The results (p=0.05) indicated a violation of the assumption of normality, leading to the application of the non-parametric Wilcoxon test to compare the mean scores of the two factors.

The test detected a statistically significant difference between the two factors (p < 0.01). In other words, respondents evaluated the two sets of questions differently. The Wilcoxon test indicated, however, that the effect size is moderate (RBC = 0.247). In other words, the magnitude of the difference between the scores reflects a consistent, although not accentuated, trend of superiority of factor 1 in relation to factor 2. In this sense, as the average of the first factor is significantly higher compared to the second factor, we also found evidence that helps to answer Q2. Journalists not only resort to two interpretative dimensions about the relationship of this activity with technology, but also tend to agree more with the Innovative and Strategic perspective than with Digital Skepticism.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the mean and standard error. Source: the author. Note: The calculation of the Standard Error of the Mean serves exploratory purposes, allowing the evaluation of the stability of the means observed within the group of participants. Innovative and Strategic Journalism (M = 3.53; SD = 0.83) e Digital Skepticism (M = 3.33; SD = 0.75), based on responses from 230 participants. The error bars represent the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM), calculated as SD/√n. resulting in 0.054 for Journalism and 0.049 for Skepticism.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the mean and standard error. Source: the author. Note: The calculation of the Standard Error of the Mean serves exploratory purposes, allowing the evaluation of the stability of the means observed within the group of participants. Innovative and Strategic Journalism (M = 3.53; SD = 0.83) e Digital Skepticism (M = 3.33; SD = 0.75), based on responses from 230 participants. The error bars represent the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM), calculated as SD/√n. resulting in 0.054 for Journalism and 0.049 for Skepticism.

As a complement to EFA, we performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), with the objective of testing the previously identified two-factor structure. The results of the CFA indicated that the covariance between the factors did not reach statistical significance (p=0.854). Although the EFA used an oblique rotation (Oblimin), the confirmatory model suggests that the two dimensions (Innovation and Skepticism) can be treated as independent constructs.

This is an important finding, as it contradicts the expectation that optimism and skepticism would be correlated poles of the same attitude. In fact, the test demonstrates that journalists internalize the technological paradox into two coexisting and statistically distinct dimensions of perception. In other words, statistical independence means that a journalist's attitude toward innovation does not predict his or her attitude toward skepticism. The two attitudes coexist, but are motivated or perceived separately by journalists.

The results of the CFA indicated that the items have high and statistically significant factor loadings in their respective factors, corroborating the validity of the proposed structure. In addition, we saw that the factors are independent. The model's global fit indices, in turn, revealed a moderate fit (CFI = 0.875; RMSEA = 0.075), demonstrating that, although the factorial structure is theoretically consistent and statistically plausible, there is room for refinements in the model.

After confirming the two-factor structure, we applied Cronbach's alpha test to assess the internal consistency of each dimension. The Innovative and Strategic Journalism factor showed a high alpha (α = 0.701), indicating homogeneity in the responses. The Digital Skepticism factor, however, registered a lower value (α = 0.504). Additional tests with cumulative exclusion of items in Factor 2 resulted in minimal variations in the coefficient, suggesting that the low consistency would not be concentrated in a single item. but possibly in the heterogeneity of the data. The tests with cumulative exclusions also allowed us to decide to maintain Q18, which presented a factor load that was not so high, but whose exclusion had little impact on the Cronbach test.

The comparison of the two Cronbach results responds to Q3 (internal consistency of factors). There is evidence that the critical view has less internal consistency. That is, the critical dimension to the use of technologies presents a low cohesion in comparison with the innovation and strategy dimension.

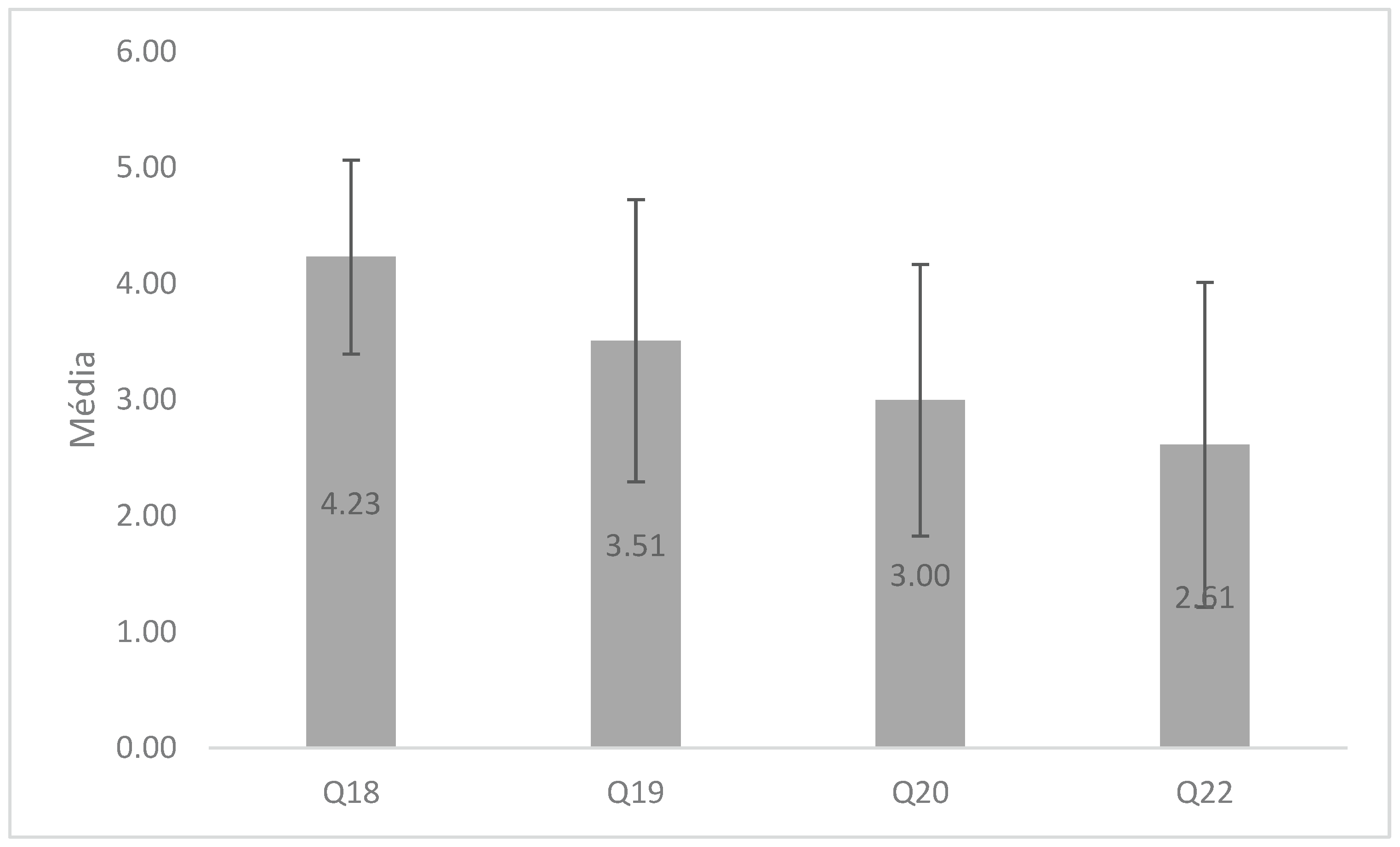

The low Cronbach value for the skepticism factor led to a more specific analysis of the questions in this group, in order to better understand the behavior of the data. In general, the distribution of the means and standard deviations of questions 18, 19, 20 and 22 show the existence of discrepancies in critical perceptions among journalists, a finding relevant to the scope of this study.

Q18 had a mean of 4.23 and a low SD (0.84), indicating strong agreement and low dispersion among respondents. Journalists tend to present a positive and more consensual view of technology as an ally of journalism, a view therefore with low digital skepticism. In the other questions, we noticed a greater degree of divergence from the respondents. Q19 had a mean of 3.51 and SD of 1.21, i.e., a behavior that points to a moderate agreement, but with high dispersion. In this sense, it is possible to say that there is a critical view, however, less consolidated, due to divergent opinions about the impact of technology. This behavior is similar to that recorded in Q20, which measured respondents' perception of the effects of big techs on journalism. The mean was 3.0 with an SD of 1.17, indicating an even less clear position with high dispersion. In other words, journalists presented a more ambivalent view of the impact of big tech companies.

Figure 3.

Mean and standard deviation of the Digital Skepticism questions. Source: the author. Note: The error bars represent the Standard Deviation (SD) of the responses, indicating the Data dispersion: Q18 (M = 4.23; SD = 0.84). Q19 (M = 3.51; DP = 1.21). Q20 (M = 3.00; DP = 1.17) and Q22 (M = 2.61; DP = 1.40).

Figure 3.

Mean and standard deviation of the Digital Skepticism questions. Source: the author. Note: The error bars represent the Standard Deviation (SD) of the responses, indicating the Data dispersion: Q18 (M = 4.23; SD = 0.84). Q19 (M = 3.51; DP = 1.21). Q20 (M = 3.00; DP = 1.17) and Q22 (M = 2.61; DP = 1.40).

Finally, Q22, which measured journalists' perception of the changes for the worse in the idea of what is news after the arrival of social networks, had a lower average (2.61) and SD of 1.40. In this case, respondents tended to agree less with the statement (low critical view). In addition, the high value of the DP suggests great dispersion in the answers, which may indicate the existence of groups with divergent views — some more critical, others less so. The data, therefore, point to a fragmented perception among journalists on the issue of news and social networks.

This set of data demonstrates that the critical perspective of journalists, except for limitations in the interpretation of the questions answered, tends to present a lower consistency due to the different views of the respondents and, therefore, less congruent (Digital Skepticism), a behavior captured in the low value of the Cronbach test. On the other hand, the journalists who participated in the sample have a more optimistic and more consistent understanding of the positive effects of technology in this professional field (Innovation and Strategy), as suggested by the result of the high Cronbach test.

Discussion

The technological paradox has today constituted one of the critical points of the performance of the journalistic field. While the technologies of news production and distribution (press, radio and TV) were under its domination, journalism was able to constitute itself not only as a company concentrated in the information market, but also as a space for the development of a professional activity, with routines, values, roles and attributions. The institutionalization of journalism, that is, the recognition of its space of action and its responsibility in mediating public debate, stems from this double process that occurred throughout the twentieth century.

The emergence of digital communication technologies in the mid-1990s, however, represented a turning point in a growing and profound transformation of journalism as a company, professional activity and institution. In the specialized literature, the turning point occurs when the mastery of production and distribution technologies, above all, leaves the journalistic field and passes to large technology companies, the so-called big techs. Whether in the processes of investigation, interaction or news distribution, journalism today finds itself dependent, to a large extent, on the technologies of big techs, with their own interests and logics.

From this perspective, the technological paradox of journalism occurs due to the choices of the professional field. On the one hand, journalism sees the expansion of digital technology as an opportunity to reinvent and transform the activity. However, this same movement greatly expands the dependence on technologies under the domain of companies and the institutional role hitherto attributed to journalism.

This study presents findings that contribute to a deepening of this debate. Unlike other surveys that evaluated journalists' perceptions of specific technologies, such as AI, social networks, platforms, among others, without a more comprehensive view of the beliefs of these professionals, which often legitimize and have repercussions on the more structural choices of the field, our study sought to direct the gaze to this issue. How do journalists perceive the uses of technologies?

Based on data from the survey applied to 230 Brazilian professionals, we applied a series of statistical tests to verify three hypotheses. In the first of these, with the application of Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, we found evidence that the journalists who participated in our sample have a two-factor structure in their relationship with technology, clearly distinguishing between an enthusiastic perspective and a critical view.

This finding clearly illustrates the presence of the technological paradox. The professionals are aligned with two visions. The first of them seeks to identify opportunities for the activity, companies and even for the institutional space of the activity (Innovative and Strategic Journalism), while in the second the journalists are less optimistic (Digital Skepticism) with technology. This first finding confirms what the literature in the field has pointed out, that is, the existence of uses of technologies that can expand the potential of journalism, as well as the identification of numerous negative effects on the profession, its practices and the survival of companies.

A second equally relevant finding showed that the optimistic view is significantly stronger than the critical view. This data indicates something worrying. The technological paradox is being reinforced, with journalists showing an inclination in favor of greater use and interaction of the apparatus controlled by big tech companies. The eminently positive perception of the uses of these devices suggests a professional field more open to innovation, a highly relevant fact, however, it also reveals an attitude that tends to subdue the risks and negative consequences of the unequal relationship with big techs, or even its impacts of an ethical nature.

The findings of Ekström, Ramsälv, and Westlund (2022) reveal, for example, significant epistemological implications of the appropriation of audience analyses in data-driven journalistic culture, supporting the hypothesis that technology affects the profession, its values, and beliefs. The research demonstrated that metrics have emerged as a superior standard in determining the epistemic value of news, i.e., what is considered valuable knowledge for the public, shaping strategies, guidelines and discussions in the newsroom, as well as the training, evaluations and rewards of individual journalists. In particular, the internal metric of completed reads has become a sophisticated KPI (Key Performance Indicator), driving not only clicks but reader engagement (Ekström, Ramsälv, and Westlund 2022)

In the Brazilian context, Christofoletti (2019) identified in turn that there is an intrusive predisposition of journalists, facilitated by technology, in the use of reserved databases and instant messages. There would also be uncertainty among journalists about the ethical and legal limits of the use of new tools such as drones to capture images, a practice that would reveal a blurring of the "boundaries between ethical slippage and crime" (Christofoletti 2019, 193). From this perspective, a low critical view in the use of technologies raises a succinct question not only about the survival of the journalistic company, but also issues that affect and transform journalistic activity and its role as an institution.

The third finding of this research is directly related to the second. The problematization of the critical perspective, that is, of the Digital Skepticism factor, confirmed that this dimension has a lower internal consistency (α = 0.501) than the Innovation and Strategy factor (α = 0.701), suggesting that, among professionals, there is less agreement on the negative impacts of digital technology.

The analysis of the questions that group the perspective of Digital Skepticism expresses these differences well, not only due to the high variability between the questions, such as average agreement rates that ranged from 4.23 to 2.61, on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In short, journalists are more certain of the positive effects of the use of technologies than of the negative impacts. Again, this finding illustrates a concern pointed out in other studies.

This understanding, however, needs to be combined with another finding. It is crucial to analyze the proximity of the averages together. Although the Wilcoxon test (Q2) found a significant difference between Factor 1 and Factor 2, this difference has only a moderate effect size (). In other words, the dimensions are not profoundly distant in terms of prevalence. This finding, combined with the statistical independence verified in the CFA, suggests that the technological paradox manifests itself as two equally present postures, reinforcing that journalists do not move on a single continuum. The paradox is, therefore, the coexistence of these disconnected postures: the journalist can perceive the use of a technology as positive and, simultaneously, maintain his perception of the risks.

This proximity dialogues with the findings of other studies that have identified journalists' concerns about the use of AI. The desire to use innovations can often filter through digital skepticism, in this case, translated by the level of confidence of professionals in the application of an emerging technology, such as Artificial Intelligence. Wu and Li (2024) argue that, despite a high willingness of journalists to use AI, this acceptance is significantly and negatively impacted by the perception of several risks, including functional risks related to the limitations of AI. In this sense, the authors note that trust in technology acts as a key mediating factor in journalists' uses of AI (Wu and Li, 2024).

Although our findings have limitations, as it is the analysis of a convenience sample that does not allow us to extrapolate its conclusions, we have consistent evidence that the technological paradox discussed in several studies is present in the perception of the Brazilian journalists who participated in this study. This data suggests that these professionals, although they have greater agreement on the positive effects of the use of digital technologies, would not fit into a type of uncritical optimism.

However, although they also present a critical view, the mean of this factor was not only lower, but also very close to the midpoint of the scale, indicating a greater ambivalence of the professionals in the critical dimension. We believe that these findings contribute to a more nuanced view of the relationship between journalism and digital technologies, indicating the need for further studies, especially longitudinal research that examines the behavior of these two dimensions.

Notes

The author declares that there are no relevant conflicts of interest for the content of this article.

This study used Artificial Intelligence to assist in the production of programming code in python for data analysis and critical review of statistical findings. AI was also used for grammar review of the text.

The research data will be available as soon as the study is published in a peer-reviewed academic journal.

References

- Anderson, C. W., Emily Bell, and Clay Shirky. 2012. Post-Industrial Journalism: Adapting to the Present. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

- Bell, E., and T. Owen. 2017. The Platform Press: How Silicon Valley Reengineered Journalism. New York: Columbia Journalism School.

- Belair-Gagnon, Valerie, Rodrigo Zamith, and Avery E. Holton. 2020. “Role Orientations and Audience Metrics in Newsrooms: An Examination of Journalistic Perceptions and their Drivers.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1215–1229. [CrossRef]

- Cheruiyot, David, Stefan Baack, and Raul Ferrer-Conill. 2019. “Data Journalism Beyond Legacy Media: The Case of African and European Civic Technology Organizations.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1215–29. [CrossRef]

- Christofoletti, Rogério. 2019. "Perceptions of Brazilian journalists about privacy." Matrices 13(2): 179–197. [CrossRef]

- Christofoletti, Rogério. 2025. "Threats of digital platforms to journalism: contributions to regulation." Advanced Studies 39 (113). [CrossRef]

- Cools, Hannes, and Nicholas Diakopoulos. 2024. “Uses of Generative AI in the Newsroom: Mapping Journalists’ Perceptions of Perils and Possibilities.” Journalism Practice, August, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Cools, Hannes, and R. Vreese. 2025. “From Automation to Transformation with AI-Tools: Exploring the Professional Norms and the Perceptions of Responsible AI in a News Organization.” Digital Journalism. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Rodrigo. 2020. "Journalism, Data Visualization and Perception About Readers." Brazilian Journalism Research 16 (3): 1–18. [CrossRef]

- DalBen Furtado, Silvia. 2020. "Automated Journalism in Brazil: analysis of three bots on Twitter." Brazilian Journalism Research 16 (3): 476–501. [CrossRef]

- De-Lima-Santos, M. F., and R. Salaverría. 2021. “From Data Journalism to Artificial Intelligence: Challenges Faced by La Nación to Implement Computer Vision in News Reporting.” Palabra Clave, in press.

- Deuze M, Witschge T. 2017. “Beyond journalism: theorizing the transformation of journalism. Journalism” 19(2):165–181. [CrossRef]

- De-Lima-Santos, Mathias-Felipe. 2022. “ProPublica’s Data Journalism: How Multidisciplinary Teams and Hybrid Profiles Create Impactful Data Stories.” Media and Communication 10 (1): 5–15. [CrossRef]

- De-Lima-Santos, Mathias-Felipe, and Lucia Mesquita. 2021. “In a Search for Sustainability: Digitalization and Its Influence on Business Models in Latin America.” In Journalism, Data and Technology in Latin America, edited by Ramón Salaverría and Mathias-Felipe De-Lima-Santos, 55–96. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Ekström, Mats, Amanda Ramsälv, and Oscar Westlund. 2021. “Data-driven news work culture: reconciling tensions in epistemic values and practices of news.” Journalism 23 (4): 761–772.

- García-Orosa, Berta, Xosé López-García, and Jorge Vázquez-Herrero. 2020. “Journalism in Digital Native Media: Beyond Technological Determinism.” Media and Communication 8 (2): 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, Rasmus K., and Sarah A. Ganter. 2022. The Power of Platforms: Shaping Media.

- Oh, Sangyon and Jaemin Jung. 2025. “Harmonizing Traditional Journalistic Values With Emerging AI Technologies: A Systematic Review of Journalists’ Perception.” Media and Communication 13: Article 9495. [CrossRef]

- Pariser, Eli. 2012. The Invisible Filter: What the Internet Is Hiding From You. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

- Pithan, Liana Haygert, Janaína Kalsing, and Vivian Augustin Eichler. 2020. "Journalists' perception of work under the influence of audience metrics." Studies in Journalism and Media 17(1): 1–20.

- Poell, T. , and D. Nieborg. 2020. “Platforms and Cultural Production: Remapping the Digital Media Industries.” Social Media + Society 6 (4). [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, Diego García. 2021. "Journalism in the Attention Economy: the relationship between digital platforms and journalistic organizations." Advanced Studies 39 (113). [CrossRef]

- Salaverría, Ramón, and Mathias-Felipe De-Lima-Santos, eds. 2021. Journalism, Data and Technology in Latin America. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65860-1_3. [CrossRef]

- São Paulo, Folha. 2024. "Is artificial intelligence about to kill what's left of journalism?"https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2024/05/a-inteligencia-artificial-esta-prestes-a-matar-o-que-resta-do-jornalismo.

- Steensen, Steen, and Oscar Westlund. 2020. What is Digital Journalism Studies? London; New York: Routledge.

- Träsel, Marcelo. 2014. "Data-driven journalism: approximations between journalistic identity and hacker culture." Studies in Journalism and Media 11(1): 291–304. [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell and Martijn de Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Nova York: Oxford University Press.

- Westlund, Oscar, Arne H. Krumsvik, and Seth C. Lewis. 2020. “Competition, Change, and Coordination and Collaboration: Tracing News Executives’ Perceptions About Participation in Media Innovation.” Journalism Studies 22 (1): 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, Jason. 2019. Tech Giants, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of Journalism. Routledge Research in Journalism. Londres: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Wölker, David, and Tobias Powell. 2018. “Algorithms in the Newsroom: News Readers’ Perceived Credibility and Selection of Automated Journalism.” Journalism 22 (1): 85–104.

- Wu, Qiong, and Jiajia Li. 2024. “Journalists' Technological Trust and Willingness to Use Generative AI: A Perspective Based on Risk Perception Theory.” Paper presented at 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction (ICHCI), September 2024.

- Wu, Shangyuan, Edson C. Tandoc Jr., and Charles T. Salmon. 2018. “Journalism Reconfigured.” Journalism Studies. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).