A. Particles

1. Single Particle. The model quantum system in this paper is a single particle. Single particles are easy to work with and single-particle results are readily extended to multi-element systems. Hence, much of what we say in this paper about a “particle” applies to quantum systems more widely. Although we seldom identify the species of particles in this text, note that every particle belongs to one species or another. The species may be elementary, e.g., an electron or photon, or composite, e.g., a hydrogen or fluorine atom. The species sets the degrees-of-freedom per particle, the number of different ways the particle can store and transfer energy, momentum, angular momentum,… It equals the number of independent quantum states per particle. The latter fixes in part the dimension (number of independent axes, size of the basis) needed to generate the state space or Hilbert space of a quantum system. We discuss these concepts below.

2. CM Waves and Particles. QM “particles”, notoriously, act at times like CM particles, at times like CM waves. Regardless of size, a CM particle can be treated formally as if it occupied a single point in space at each instant in time. That point, for massive (i.e., non-zero mass) particles, is its center-of-gravity (c.g.) A CM particle travels thru space-time in a 1D trajectory with one velocity at each point along the trajectory. When two particle trajectories intersect, the particles often simply bounce off each other, preserving their integrity thereby. (They may also undergo a chemical, nuclear,… reaction, transforming into different species.) In sum, classical particles are hard, compact entities like bullets, pebbles, or seeds that hold together, resist combination, and move on well-defined paths.

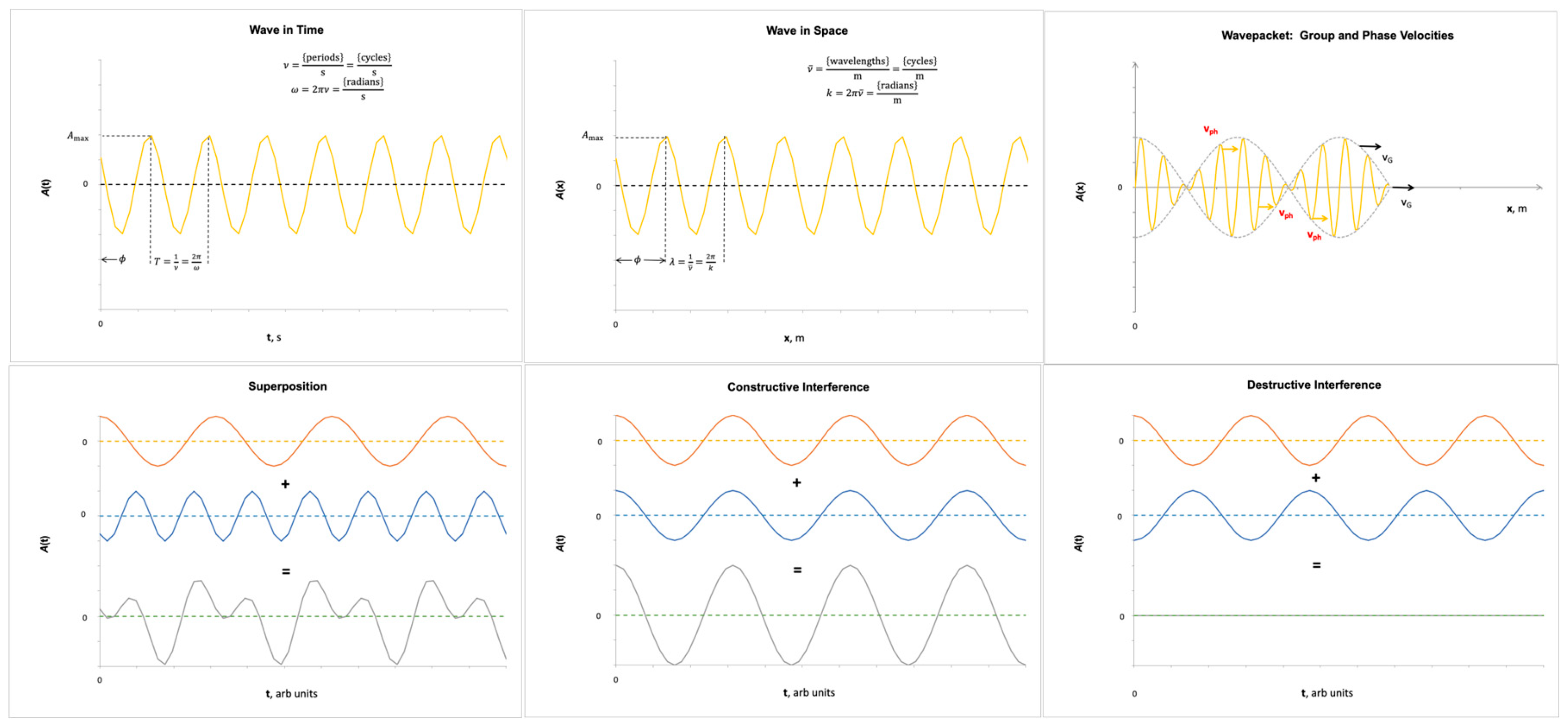

Structure and behavior of a CM wave, in contrast, are never captured by a single point. A wave rather spreads (

Figure 1), often in rhythmic peaks and troughs, across space and time. Its

wavelength is the scale of spread in space, its

frequency the scale of spread in time. Instead of trajectories, waves travel in 1D or 2D

wavefronts. Waves, moreover, have

two velocities. Wave

group velocity is the rate at which single pulses (contiguous feature aggregates) of the wave,

wave groups or

wavepackets, propagate thru space.

is also the velocity of the wavefront and of the

envelope surrounding a wavepacket. Phase velocity

is the rate at which any single feature (e.g., the crest of one peak) moves within or between wave groups. For monochromatic (single-wavelength, single-frequency)

electromagnetic waves (

light)

and

, where

is the speed of light in vacuum and

light-speed in any particular medium. When waves collide they do

not preserve their integrity. Rather, they merge, they

superpose or

interfere. When waves merge, their coincident amplitudes add algebraically point-by-point. Positive adds to positive to make higher peaks; negative adds to negative for deeper troughs (

constructive interference). Positive and negative aligned amplitudes, however, wholly or partially cancel each other out (

destructive interference). Constructive and destructive interference can result in complicated waveforms with multiple frequency components. Critically, constructive can become destructive interference (and

vice-versa) when a (left or right) phase shift of one or both summing waves turns peaks wholly or partly into troughs (and

vice-versa). Hence, the (leading or lagging) phase determines the outcome of superposition independently from and as much as intrinsic variation in the (positive or negative) wave amplitude. In sum, we think of waves as fusible, diffuse entities like swell on the beach, audio tones, or mechanical vibrations that dissipate, readily combine, and propagate in fronts.

3. Complex Numbers. Both CM and QM waves are well modelled using complex numbers. Complex numbers are widely used in Physics in scenarios where two independent algebraically signed factors (like phase and amplitude of a wave) determine an outcome. In CM, complex numbers are a mathematical convenience. In QM complex numbers are undeniably indispendable in everyday practice. One debates whether they are ultimately just mathematical tools or of deep significance. This subsection detours briefly from the main theme to introduce complex numbers and to motivate their use.

As neuroscientists know from MRI and elsewhere, a complex number is a number of the form (). is the base of the imaginary number system. In polar form, a complex number is . The norm, length, magnitude, or modulus of is . Every complex number has a conjugate, , formed by replacing wherever it appears by . has the same length as , . A related expression much used in QM is . (In general .) Complex numbers can be represented as vectors on the complex plane with the real axis serving as and the imaginary as . A limitation to this analogy is that one can divide by any non-zero complex number , but never by a 1D number-array vector.

Hard-headed people ask, “How can a number be imaginary!? What’s that supposed to mean!?” Here is one answer, a way to intuit complex numbers in physics. Complex numbers are often used in CM scenarios where some quantity (charge, energy,…) shuttles periodically between two independent modes. One mode is assigned to the real, the other to the imaginary axis. Complex numbers are used when the real axis alone is insufficient to keep track of everything that is going on with a phenomenon.

As example, take a series AC electrical circuit. The circuit is driven by a power supply or other source. It generates, as they typically do, an AC voltage that varies in time as a complex sinusoid, e.g., . (A “sinusoid” is a function from the family of constant, trigonometric, exponential, or related functions.) is the maximum amplitude of the signal and its frequency. The source is attached to a resistor , a capacitor , and an inductor all connected in a row. If we attach the twin leads of a voltmeter across it measures the real part of the voltage . ( is called the dissipative component of the circuit since it dissipates the electrical energy put into it by the source immediately.) If we place the leads across together the voltmeter measures the imaginary part of the voltage . ( is the reactive component; it reacts to input energy by storing it temporarily. stores magnetic energy on the timescale ; stores electric energy on the timescale .) Since , both real and imaginary parts oscillate smoothly between and . The magnitude of the total voltage remains constant as it shuttles between positive and negative real and imaginary components. At , the full voltage is across ; the voltage across is 0, it only exists in potentia. But later, at , the voltage is 0 and only exists in potentia while the voltage is . Later still, at , the situation again reverses. For a metaphysical perspective related to QM, suppose is very low, the circuit oscillates so slowly you can touch it and pull back before the voltage changes much. If you grabbed the resistor bare-handed and grounded at when its voltage was near zero, you’d feel nothing. Very little voltage would be in the real mode. Most would be imaginary. It would not yet be part of reality for you. But if you hung on, by the voltage would be fully back in the real mode and shock you! Hence, imaginary numbers have real consequences. Intriguingly, you might never feel the shock, e.g., if someone cut the wire before the heavy voltage hit. In that sense, the potential voltage in the imaginary mode is not real. In the normal course of events, however, eventually the voltage will rise and shock you if you don’t let go. Endlessly many physical events in the world run similar cyclic courses. Thus, effects represented by imaginary numbers do exist in a pragmatic sense. They reflect what can and usually does happen. The same hard-headed soul who scoffed at imaginary numbers would be the first to scold you for playing with live wires!

Complex numbers show quantitative linkages between physical modes in space and time. An element of time is inevitably present in practical measurements. Even flash photography requires non-zero time to register an image. As ultra-precise as time metrology has become, physics still cannot eliminate time from its models. Complex numbers are highly apt for capturing, especially rhythmic, variations of CM quantities in time. In QM, the probability amplitude (see below) for observing a particle in a certain quantum state may act like a vector of constant length rotating rhythmically around the complex plane. One interpretation of this is that particle properties (like voltages in AC circuits) oscillate in and out of reality. An alternative, holistic, interpretation is that QM information is shuttled between one mode for information manifest by a single particle and another for information banked in in the statistical ensemble to which the particle belongs.

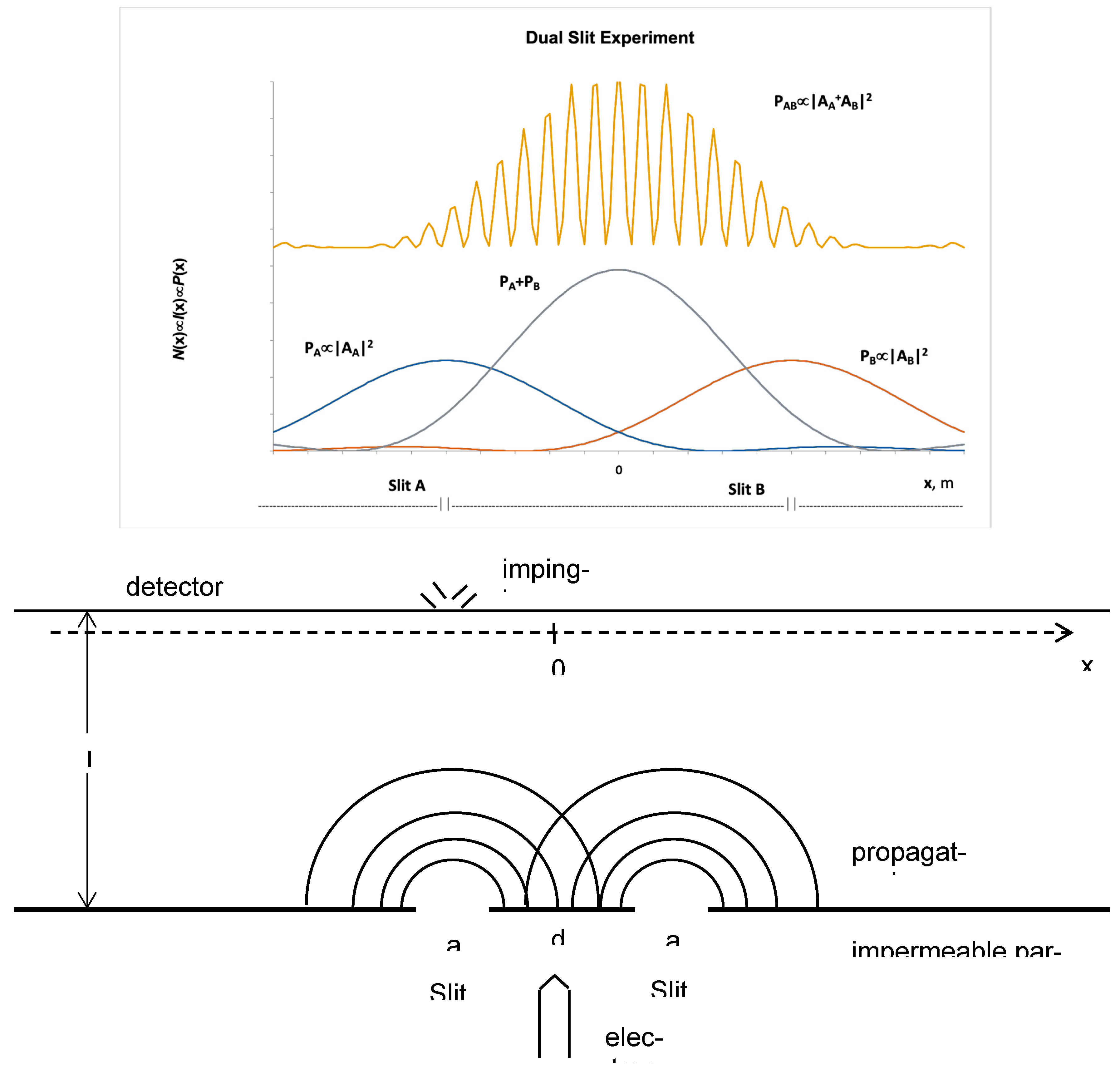

4. Dual-Slit Experiment: Wave-Particle Duality. Feynman (e.g., Feynman & Hibbs 2010) famously used the Dual-Slit Experiment to illustrate Wave-Particle Duality and the need for complex numbers in QM. We discuss this briefly for the case of electrons (

Figure 2; Jönsson et al. 1961). With parameters modified, similar results are obtained for all QM particles, including photons (Young 1804), neutrons (Zeilinger et al. 1988), atoms (Carnal & Mlynek 1991), even buckyballs (Arndt et al. 1999)! In the Dual-Slit Experiment, an electron gun fires electrons thru one or both of a pair of identical narrow (even for an electron) vertical slits (A,B) cut in an otherwise impermeable thin partition. (Either the gun slides horizontally on a track to line-up in the middle or behind either slit or the dimensions are so small the gun need not move.) The horizontal gap between the slits is modestly wider than the slits themselves. Slit height can be taken as infinite. A screen mounted ~1 m opposite registers the impact of each electron making it thru the slit and across the distance. After firing many electrons, the impacts form a spatial pattern or distribution across the screen. The horizontal (

) component of the distribution is of prime interest.

, the number of impacts at each

in a given time interval is proportional to the electron beam intensity

and to the probability

of an impact at

. If we run the experiment with A open and B covered or

vice-versa (single-slit paradigm), we get the distributions

, respectively,

. If we open both slits (dual-slit paradigm), we get

.

First we observe that, no matter which slit(s) are open, we

always detect

individual electrons impacting at the screen. (As implied above, the same happens when one does the experiment with light, individual photons are registered at the screen.) This suggests electrons (and photons, etc.) are discrete CM

particles. This conclusion, however, is contradicted by the mathematical form of the distributions

,

, and

. If electrons were CM particles,

would be a flat line segment of constant height and width

located directly across from A and aligned with it. Outside this segment, the probability of observing an electron impact would be 0. The same curve would result for

, only shifted to the right to align with B.

would consist of both segments side-by-side, separated by

. In reality,

and

are not constant functions, but given by

Single-Slit Diffraction Probability Distributionswhere

is the maximum electron wave amplitude. (Other symbols defined in text and

Figure 2). These are variants of the sinc function (

). The maxima of these distributions do occur opposite their respective slits, yet many electrons impact left and right of the slits. The distributions are a kind of

diffraction pattern. Diffraction is typical behavior for several kinds of CM waves. It results from the bending of a wave as it passes thru an

aperture, like Slits A and B.

is a more complicated sinc

Dual-Slit Diffraction Probability Distribution

It indicates diffraction combined with interference (

Figure 1). It suggests that electrons emerge from A and B as coincident waves that interfere with each other constructively and destructively as they propagate to yield peaks and troughs at the target. This is again CM wave behavior. Thus,

,

, and

suggest electrons are CM waves. Hence, the Dual-Slit Experiment provides clear evidence that electrons (and other QM particles) act sometimes like CM waves and sometimes like CM particles.

Now, for water waves, the level of the water surface is the quantity bobbing up-and-down. For sound waves, it is the air pressure level. In AC circuits, it is voltage or current. If we say that QM particles act at least partly like CM waves, what exactly is waving for a QM particle? In >100 years, QM has still not answered this question satisfactorily. Since Eqs. (1-2) are for probabilities, perhaps QM waves are probability waves? This, however, is not quite accurate. If electrons moved in probability waves, for both slits open the distribution would be simply

(

Figure 2 teal). But the actual distribution

. These quantities cannot be equal. For probabilities are always

positive numbers. Adding them could never generate the troughs in the interference pattern. The electron wave is instead a

probability amplitude , a complex number that, multiplied by

, is proportional to a probability, e.g.,

,

. For both slits open,

. Only by adding

and

as complex numbers can we reproduce the empirically observed interference pattern. Thus, the Dual-Slit Experiment shows the necessity of complex probability amplitudes to describe QM particles.

A couple remarks on Wave-Particle Duality. The wave properties of QM particles have statistical character. That is, they emerge when large numbers of particles are observed. If we run the dual-slit paradigm and place two additional detectors right in front of A and B, we always see a single electron emerge from one or the other slit, as if the electrons are acting like CM particles. I.e., we never see the electron split half going thru each slit. But without the extra two detectors and examining large numbers of electrons, the screen impacts always distribute themselves in an interference pattern. It is as if the electrons were diffracting as they passed thru each slit and interfering with themselves as they passed thru both slits, in the manner of CM waves. Amazingly, this happens even if the electrons are fired one-by-one, hours, even days apart! I.e., results are unaffected by the mere passage of time. In QM, all particles act like waves for certain measurements and like particles in certain other measurements. As Feynman explains, whenever there are exclusive alternative paths available to a QM particle, e.g., when we can know with certainty the electron has gone thru A or B, we see particle behavior. Whenever we have interfering alternative paths, e.g., we cannot know whether the electron has gone thru A or B, we see wave behavior. Note that it is not about what we do or do not know in a particular instance, it is about what we fundamentally can or cannot know, given the paradigm. Intriguingly, quantum systems never exhibit both wave- and particle-character in the same measurement. Perhaps this is a consequence of the way experimental designs make sharp distinctions between what can and cannot be known. Finally, one is not restricted to two vertical slits, one may carve apertures of any shape and size into the partition and measure the resulting impact distributions. A deep insight is that the diffraction pattern is, in general, the complex Fourier Transform of the aperture function (the shape and size of the aperture across ).

5. Consequences of Wave-Particle Duality. We present two key consequences of Wave-Particle Duality.

The first is the Planck-Einstein Quantum of Action

Planck-Einstein Quantum of Action

Eq. (3) gives the total energy of a single QM particle (especially of a photon of monochromatic light). The higher the particle frequency , the greater its energy. is Planck’s constant, a universal constant of Nature central to QM. Among other things, multiples of (the reduced Planck’s constant ) represent the quanta (smallest possible amounts in Nature) of angular momentum (torque or “rotational force” applied over time) or of action (energy applied over time). Eq. (3) reflects the particle-character of QM particles. Thus, energy and angular momentum come in packets (particles) of a minimum size.

The second result is the de Broglie Hypothesis. Although their mass is zero, photons have not only energy, but also linear momentum . The latter is given by

de Broglie Linear Momentum of a QM Particle

Thus, the longer the wavelength, the smaller the momentum; the shorter the wavelength, the greater the momentum. In a revolutionary departure from CM, the de Broglie Hypothesis also applies to massive particles, e.g., electrons, protons,… A particle of mass moving at velocity has (non-relativistically) momentum . Per Eq. (4), every such particle has a wavelength . (Note that here is the group velocity of the particle wave.) QM experiments consistently show that light acts like particles with energy given by Eq. (3) and momentum given by Eq. (4). Further experiments confirm that massive particles like electrons, neutrons, etc. have wavelengths given by Eq. (4) and can be focused, refracted, diffracted, etc. just like light waves.

C. Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

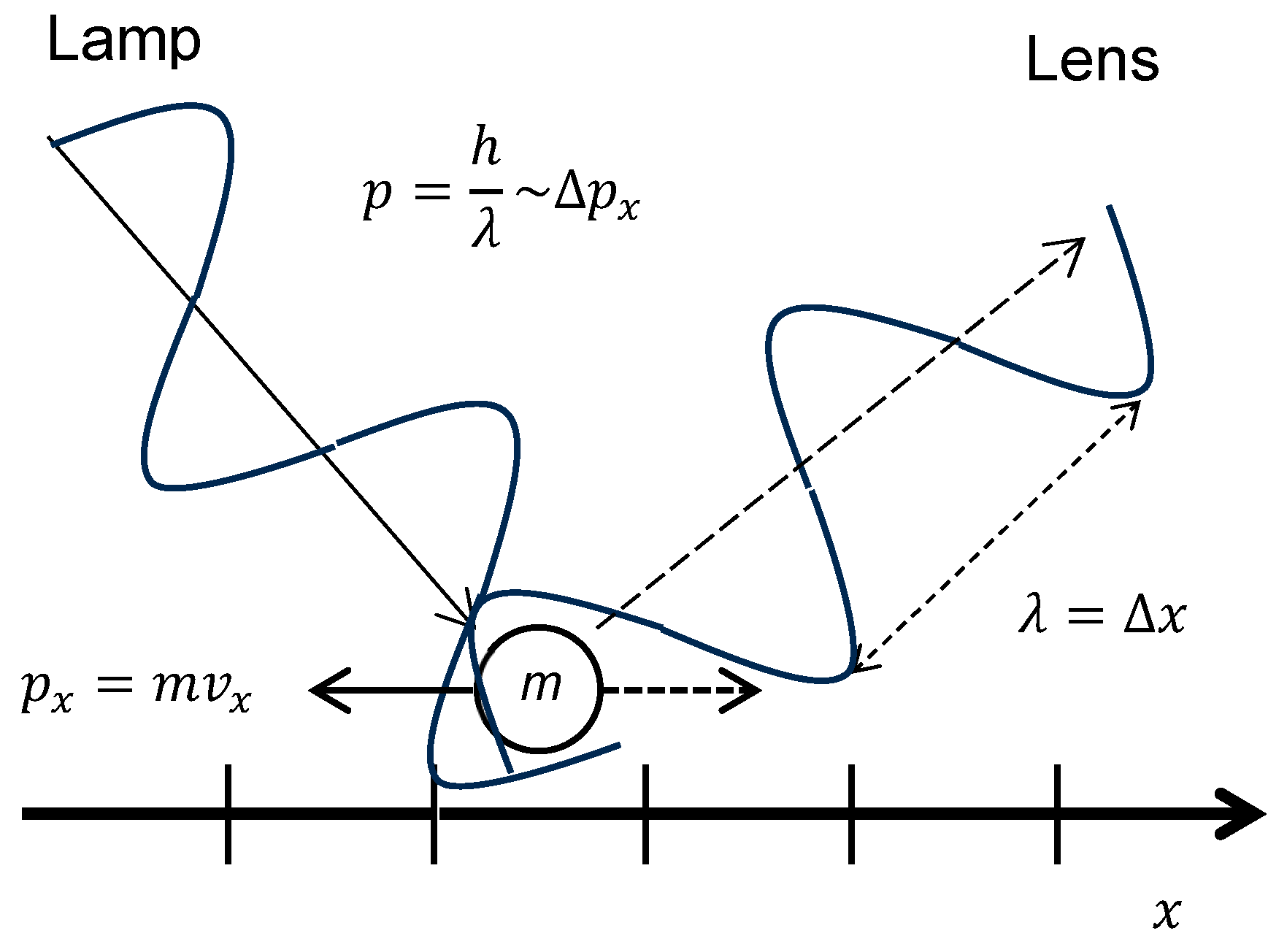

1. Supermicroscope Gedankenexperiment. This Gedankenexperiment (thought experiment;

Figure 3) is overused and has been critiqued. Nonetheless, it is a familiar and intuitive way to ease into QM, to introduce the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. The main idea of the Uncertainty Principle is that we can never know

everything about a particle. This is seldom explained in full. Specifically, it means that there exist specific pairs of properties (

non-commuting observables) that cannot both be measured together with unlimited precision. They can both be

measured together to be sure, only each is tagged thereby with an uncertainty, a physically irresolvable doubt as to what its true value is. Either one, moreover,

can be measured with perfect precision (zero uncertainty), but only at the expense of

infinite uncertainty for the other. Specific pairs of

other properties (

commuting observables) like (non-relativistic) mass and charge are fine, they

can both be measured together with unlimited precision. So much information can be known about the particle. But since non-commuting observables do exist, they imply we can never know everything about a quantum system. The non-commuting observables, furthermore, include some of the most important properties, such as position and momentum, time and energy.

The Gedankenexperiment attempts to measure particle position and (thru its velocity) momentum simply by viewing the particle thru an extremely strong optical microscope. We take the simplest case: A particle moves, backwards or forwards, in a straight line, i.e., in 1D. Its position along the line is called and its momentum along the line .The microscope has a graticule, an array of fine horizontal and vertical lines dividing its field-of-view into square cells, between the particle and the eye. We use it as a ruler to measure position. The number of cells the particle flies past per second is its velocity . times the known mass of the particle equals . The microscope lamp shines (monochromatic) light on the particle. The light returns an image of (“resolves”) it, revealing what we want to know. But, notoriously, there are two problems. The first is position. In CM or QM optics, the shortest distance a light wave can resolve is its own wavelength . One wavelength is essentially the width of the brushstroke when you are painting with light. Thus , the uncertainty in the position measurement. To minimize we pick the shortest possible wavelength. But this evokes the second problem, momentum. To image the particle, the light must contact the particle (technically, approach it within a collision cross-section). Now we may think of light as a harmless intervention. Looking under the hood of a car with a flashlight, for example, we do not expect the flashlight beam to rot the hoses! Yet everyday life equally tells us that sunlight warms, grows crops, bleaches fabrics, causes sunburn, etc. Such things happen because, even in CM, light waves have energy. In fact, they also have momentum, enough momentum to change things on the microscopic level of our particle. In imaging the particle, it recoils from the light shone upon it. I.e., some of the momentum of the light gets transferred to the particle. If still, it may start moving; if moving, it may speed-up, slow-down, or change direction. I.e., its velocity will be altered, rendering the measurement of its original momentum less certain. The greater the momentum of the incoming light, the more the momentum uncertainty . To minimize , we pick the lowest momentum light we can. But our particle is a quantum system. In QM, the weakest light we can shine is one photon. Per Eq. (4), the momentum of a photon is . This is inversely proportional to wavelength. Therefore, the shorter the wavelength we choose to minimize , the greater will be; the longer the wavelength we choose to minimize , the greater . We never get both and to zero. This applies not just for the Supermicroscope, but for any experiment. It is impossible to pin-down both position and momentum exactly. We can never know everything about the particle.

2. Uncertainty Relations. The Uncertainty Principle formalizes the foregoing trade-off. Its best known version is the Position-Momentum Form

Position-Momentum Uncertainty Relation

Position and momentum appear here as 3D vectors (bold). The “⋅” denotes the dot product, also known as scalar product or inner product, of the two vectors. Eq. (5) is the famous statement that the more precisely we measure the position of a particle, the less precisely we measure its momentum and vice-versa. I.e., the best-case scenario is . If 0 we must have for their product still to equal . If we know exactly where the particle is, we have no idea how fast it is going. Conversely, 0 implies . If we know exactly how fast the particle is going, we have no idea where it is.

The next best-known version is the Time-Energy Form

Time-Energy Uncertainty Relation

where is the time of observation of the particle and its total energy. Similar to Eq. (5), the more precisely we quantify the timescale of a particle, the less precisely we know its energy and vice-versa. (Note some do not consider the Time-Energy Form a bona fide uncertainty relation, since is technically not a QM operator, but a parameter, and for other reasons. But no one denies its pervasive accuracy and utility.) The Uncertainty Principle in all its forms is a consequence of the wave-character of light and matter. Note interestingly that, in Eq. (5), and are evaluated at a specific time, , they cannot both be known simultaneously; in Eq. (6), and are evaluated at a specific place, , they cannot both be known co-locally.

Comment 3: Regarding Eq. (6), the literature frequently uses the phrase “particle of definite energy” without explanation. This refers to the case , . “Definite energy” means “fixed, constant” energy. This important case includes all stable atoms and molecules in free space or in materials. Energies of such particles can be measured precisely. But—looking at the particle alone-- it is impossible to know how old it is. Did it pop into existence 1 ns ago? Has it been around 3 billion years? No way to tell, . The quantum state of such particles, like a classical thermodynamic equilibrium state, is ahistorical. QM particles of definite energy and equilibrium states are among the stopped clocks of Nature. (More precisely, in QM, the particle clock rotates in time thru a complex plane in Hilbert space in a way that cannot change the probability of a measurement value.) Clocks of Nature run forward when CM systems undergo irreversible processes, when QM systems undergo measurement (an irreversible process), or when undisturbed QM systems forward-evolve in time. Clocks of Nature (re)start when low-probability, large-amplitude fluctuations bring systems out of equilibrium. Thus, the Time-Energy Form characterizes particle stability.

Comment 4: It is insightful to distinguish between the physical content and the mathematical content of QM. Deciding, for example, whether to write partial differential equations, as Schrödinger did, or to write matrix equations, as Heisenberg did, is part of the mathematical content. So long as our model is empirically sound and logically coherent, we may configure the mathematical content as we please. The physical content of QM or of any theory, in contrast, is dictated by Nature. The Uncertainty Principle forms part of the physical content of QM. The quantum world is not just invisible due to technological limitations, it is fundamentally invisible as a law of physics. We never see the complete exact state of the particle, part of it always remains hidden. Nor can we predict exactly what the particle will do under all circumstances.

3. Philosophical Aspects. The metaphysical implications of the Uncertainty Principle are far reaching. The act of measuring certain physical quantities

unavoidably changes the measurement. Ultimately, an Observer cannot be perfectly passive, but rather perforce influences the measurement of key essential physical quantities (position, momentum; time, energy,…) This general proposition is formalized as von Neumann’s

Process 2 (von Neumann 1932), the arbitrary choice of the Observer. The Observer constructs the apparatus, decides which observables to measure, how to measure them, and in which order. The Observer’s free choices, moreover, unavoidably affect the outcome values (the set of eigenvalues) measured in the experiment. There is

nothing in the formalism of QM to dictate this choice. One cannot eliminate the Observer completely. von Neumann’s

Process 1, in contrast, is

quantum randomness, randomness of the quantum system itself. Those aspects of the system that we cannot measure exactly, we treat as random because that is the most rigorous way to reflect behavior that is objectively independent from us. If we fundamentally cannot know what is happening with a system below a certain level, then anything is possible for the system, up to that level. Even the tightest experimental design, most flawless execution, cannot eliminate this randomness. Thus, QM leaves room both for human free will and for random processes. The Laplacian dream (or nightmare) of a fully determined Universe is forlorn. In accepting the Uncertainty Principle, we surrender aspirations of perfect precision. Yet, we win Eqs. (5-6) (and other Relations). These quantitative formulae have innumerably enabled the construction of devices, interpretation of data, and elaboration of physical theories over the last century. Thus, the Uncertainty Principle is a splendid example of “turning a weakness into a strength” in science. Finally, all cannot be known precisely about the particle, it is always at least partly concealed from us. All we see of a particle is the macroscopic measured value (the eigenvalue) it manifests at the end of each measurement. What the particle does

between measurements is invisible to us because the particle state gets shifted around by the measurement process itself. That part is hidden means the particle inhabits a (usually microscopic) quantum world only partially accessible to us macroscopic humans (

Figure 6). A deep philosophical implication of the Heisenberg Principle is thus that the only world we can experience fully and directly is the macroscopic one we live in. Even if we take a picture of a single atom with, e.g., atomic force microscopy (AFM), we are technically not seeing the atom itself, only a macroscopic image of it. The Heisenberg Principle multiply entails profound metaphysics.

E. Quantum State

1. Quantum State-- Dirac Notation. A quantum state is a complex vector. “Vector”, depending on context, refers to a 1D number array, as in linear algebra, or to an algebraic function, as in calculus. “Complex” means the elements of the array or the arguments and/or outputs of the function are complex numbers. Dirac bra-ket notation is favored for denoting complex vectors and other quantities in QM. A quantum state in Dirac notation, for example, is most often written inside a right-pointing triangular bracket, in which case it is called a “ket”. E.g., for a quantum state written as a 1D array of complex components. If is a function, we may also write it as a ket, e.g., , where we have written in this case as an explicit function of time . We can also write inside a left-pointing bracket and call it a “bra”. A bra is the adjoint () of a ket. The adjoint of any matrix in linear algebra is the new matrix created by taking the complex conjugate and reversing the indices of (transposing) every element inside the original. Thus, element becomes for all elements. For a column vector, the transpose means lying it on its side to become a row vector. Thus, . For a row vector, the transpose is stood upright, thus, . If is a function, the adjoint is simply the conjugate, e.g., .

2. Quantum State-- Complex Number Character. Complex numbers are broadly used in QM, to the point where and are twin earmarks of QM equations. Equations of Relativity Theory, in contrast, make scant use of complex numbers. This may relate to the enduringly unresolved philosophical differences between the two theories. There are several reasons for using complex numbers in QM.

First, the probability distribution of a quantum system derives from its quantum state . But where does come from? Every quantum state comes from solving the Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation

Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation (Schrödinger Picture)

under any BCs or initial conditions (ICs) imposed upon the quantum system in question. Much as Newton’s Second Law of Motion is the heart and soul of CM, the Schrödinger Equation is the major axiom upon which QM and, by extension, much of physics, lies. Eq. (7) is the time-dependent form, written for a pure state (see below) and an isolated system. Eq (7) admits complex solutions by the laws of differential equations. But, for most choices of , pure real or pure imaginary solutions are disallowed. Hence, quantum states typically must be complex vectors or functions.

As an important aside, multiple solutions typically satisfy Eq. (7). When available, BCs and ICs narrow the choice, though not always to a single quantum state. The laws of differential equations allow that every linear combination (sum of multiples) of solutions to a differential equation is itself a further solution to that equation. E.g., if

and

are solutions to Eq. (7), then

(

) is an equally valid solution. The physical correlates of this fact are rarely discussed. Here’s what it means for the example of the Supermicroscope (

Figure 3). We chose an arbitrary distance between hash marks and an arbitrary orientation of graticule lines. But Nature needn’t respect our arbitrary choice. Rather, a particle floats any direction the constraints allow. Hence, any set of solutions we obtain must accommodate arbitrary variation in scaling (multiplication of quantum states by constants) and direction (summing of quantum states).

in Eq. (7) is the Hamiltonian or Hamilton operator. Operators in QM are denoted by a carat or hat (^) above a quantity. In QM, operators represent all observables, among other roles. They are written variously as -by- matrices, e.g., , or as analytic expressions, e.g., (total energy operator). (We do not go into how such expressions are derived.) Operators are thought of as transforms or “functions of functions” that replace one vector or function with another, e.g., . If is a vector, may rotate, stretch or compress, and/or carry out other operations on to turn it into the vector . If and are expressions, may apply differentiation, multiplication by a variable or constant, and other operations on to turn it into another function. E.g., for and , we get . The operator is an observable. It takes on different forms depending on the system. In QM, is commonly the sum of the kinetic energy operator and the potential energy operator

Hamilton Operator

and equals the total energy . Hence, thru Eq. (7), the total energy of a quantum system drives its time-evolution. As in Relativity Theory, in QM we see a special relationship between time and energy and one between position and momentum (they are non-commuting pairs).

Secondly, as mentioned, observables in QM supply the eigenstates . becomes one of these eigenstates upon measurement. The corresponding eigenvalue is the value of the observable actually obtained. Like , all observables in QM are operators. In particular, they are Hermitian operators. If operator is a matrix, being Hermitian means it equals its own adjoint

Hermitian Operator

If the operator is a function-of-a-function, e.g., , the adjoint is the complex conjugate . Additionally, in taking the adjoint, one “postpones” instead of “preponing” the operator. E.g., in Dirac notation . The Hermitian operator is a variation on the concept of a symmetric operator, an operator equal to its own transpose . Real symmetric operators are a subset of Hermitian operators. For QM, an important property of an Hermitian operator is that, though its elements may be real or complex, all its eigenvalues must be real. The values of observables obtained in actual experiments are typically real numbers (outside of quadrature detection of MRI signals, phasor analysis of electrical circuits as above, etc.) Thus, real eigenvalues aptly represent them. A happy coincidence is that “real” in the sense of “real numbers” overlaps here with “real” in the sense of “real life”. But, as mentioned, the elements of an Hermitian operator can be complex. Some important QM operators, moreover, e.g., , contain explicitly as a factor. So, again, complex numbers must be allowed in QM.

Third, Hilbert space—the space in which quantum states live (

Figure 6)-- is a complex linear vector space.

Fourth, the Hilbert space of a quantum system maps all its possible quantum states . This will take a bit to explain. Any good map has a scale and a compass to help navigate. For a Hilbert space, these are provided by its inner product, mentioned in Eq. (5). In Dirac notation, the inner product of two quantum states is

Inner Product of Two Quantum States

The inner product is our compass, it tells whether any two vectors point in the same or different directions. In particular, if , then implying . So parallel vectors have real positive inner products. If two vectors are anti-parallel (pointing opposite), , and their inner product is real and negative. If and are linearly independent (li), they are orthogonal or perpendicular. Then . The scale, or metric, of a Hilbert space is also supplied by the inner product. In particular, the norm of a quantum state is the square-root of its inner product with itself. For a vector quantum state in Dirac notation, this is

Norm of Quantum State Vector

The inner product tells us how long each vector is and, thus, scales the Hilbert space. A vector is normalized (made into a unit vector) by dividing it by its own length . The are the expansion coefficients and . If are functions, e.g., , rather than as sums of products, the above quantities are formulated as integrals over the interval (often ) over which are defined). The inner product is . (Double, triple, etc. integrals are used for higher-order dimensions.) The norm is . The normalized function is . In any case, complex numbers are embodied in the definition of the inner product. Therefore, complex numbers are needed in QM. Of signal importance, moreover, the probability of a particle being in quantum state is proportional to which involves the adjoint.

Finally, the full range of QM phenomena can only be incorporated into complex states. Thus, probability amplitudes in QM are complex while probabilities are always real numbers. Quantum states exhibit wavelike behavior that is only accurately reproduced using complex probability amplitudes, not real probabilities (

Figure 2). Above we said that complex numbers are used in CM when a quantity can be expressed in two independent modes. For wave-phenomena, for example a 1D wave, there is one mode for vertical displacement (rise and fall) and one for horizontal offset (phase). The two axes of the complex plane accommodate these two modes in a way the real axis alone could not. In particular, it allows for proper summation of waves, including quantum states. Probability amplitudes (quantum states) of single particles sum to yield the probability amplitudes (quantum states) of composite particles they form. For example, the quantum states of 54 electrons and two nuclei are summed to compose the quantum state of an HI molecule. When one sums quantum states, they superpose and interfere with each other in the manner of complex numbers. These superimpositions and interferences strengthen and weaken (even to the point of zeroing-out) the various composite quantum states to yield resultant states consistent with experiment. The phase thereby is critical. If two waves are in-phase, they interfere constructively; out-of-phase, they interfere destructively. Hence, the complex character of the quantum state, among other things, is essential in accounting for the construction of composite particles.

3. Probability Amplitude.

a.

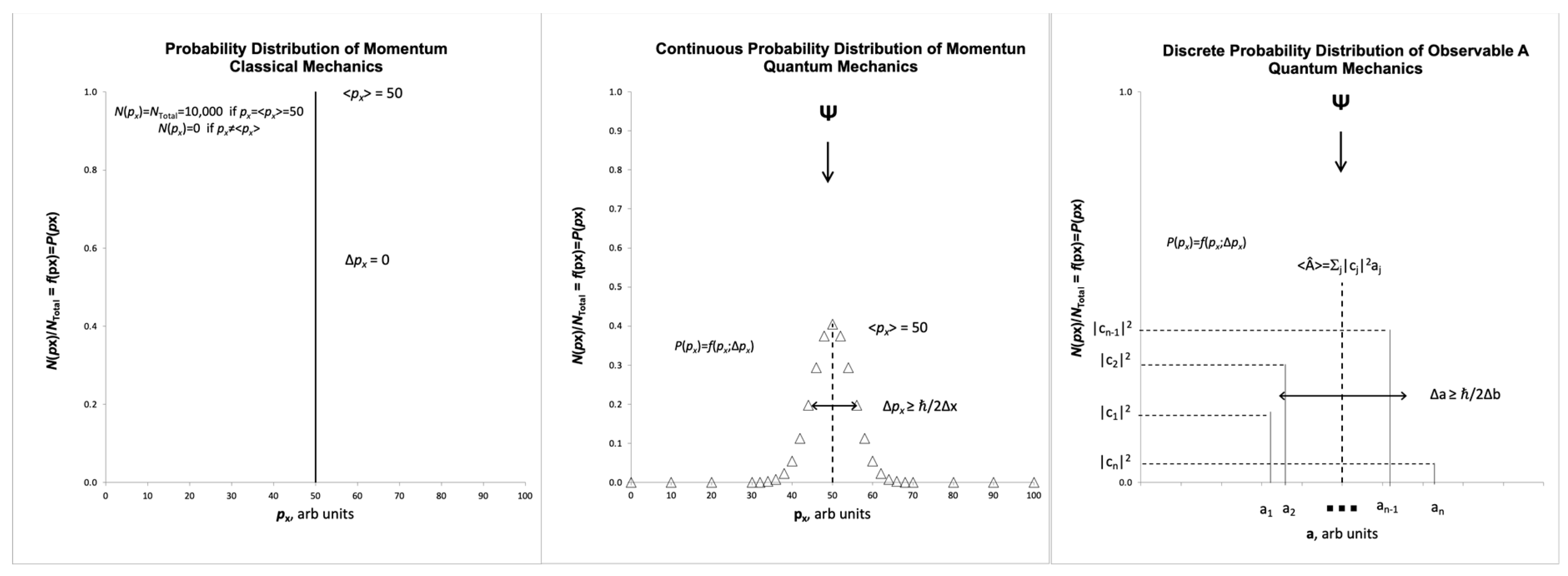

Is a Probability Amplitude. In the probability theory of CM (

Figure 6), a particle occupies the point

in state space (see below) corresponding to its present physical state with certainty (

). The particle occupies all other points

in the space (all other possible combinations of, e.g., position and momentum it could have) with

. If we measure some particle property, e.g., observable

, we obtain with certainty one fixed value

for that observable.

will be the value of

at point

. The probability theory of QM is more intricate. A particle occupies a point in state space (now called Hilbert space) corresponding to its quantum state

. But, unlike

,

offers not one, but multiple (2 to ∞, depending on the quantum system) different values

of

that could be observed with

. The values

are supplied by

and are the eigenvalues of

. Each eigenvalue

is associated with its own quantum state

. The

are the eigenstates of

. The eigenstates are in the same Hilbert space as

. In fact, taken together, they form a complete coordinate system, a basis, for that Hilbert space. That implies that

can be resolved into these eigenstates, i.e., expressed as a vector sum of them

. The expansion coefficients

tell how much (in a complex-number sense)

overlaps with each of the eigenstates. The greater the overlap, the higher the probability a given

will be observed. But the probability is not

, but rather

. In any case, both quantum randomness from

(Process 1) and the Observer’s choice or measurement procedure from

(Process 2) contribute to each observed outcome.

The probabilities of the eigenstates and eigenvalues of the particle are returned by only indirectly. is not a probability function per se. Rather it is a probability amplitude function. As oft heard, probabilities are real numbers on the interval [0,1]. A probability function returns one such value for each set of inputs. A probability amplitude function returns a probability amplitude for each set of inputs. While probabilities are real numbers, QM probability amplitudes are typically complex numbers, an important distinction.

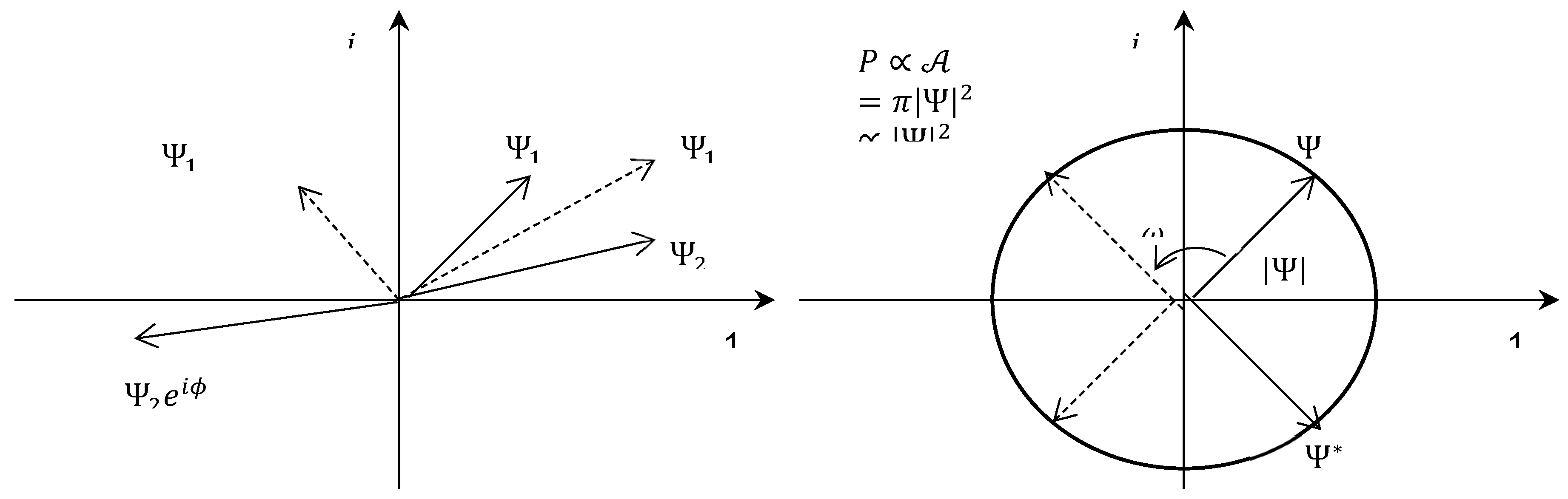

In particular, the probability of a particle being in quantum state

is proportional not to

but to

. Thus,

itself has the nature of a “square-root of a probability”! A probability is already a purely mathematical entity. When we take its square-root we get something really abstract. This underscores the existence of an aphysical side of

. Here’s one coarse way one might understand it (

Figure 5). In QM a quantum state is conventionally “defined only up to an arbitrary (or irrelevant) phase”. To illustrate this seldom well-explained phrase, let us return to the example of a particle of definite energy. Here the quantum state rotates about the origin on the complex plane as time passes with frequency

. The probability amplitude or quantum state is

. In the course of one period

, the vector traces out a circular disc of radius

. If we calculate

, we see that the phase factor

has no effect on the probability. Nor can it be measured directly. The definition of a quantum state calls for it to have an impact of some kind on some measurable quantity. Hence, all the vectors at all the different timepoints along the circle of rotation on the complex plane are, as far as measurement is concerned, the

same quantum state. One says, the quantum state is “defined only up to an irrelevant phase”. (The exact phase of the wavefunction is the information that the Heisenberg Principle renders invisible to us.) That means only the length—the norm of the probability amplitude

-- matters. Thus, for certain purposes, one can let

, the vector aligned with the real axis, stand in for all

. But here is the point that helps one grasp probability amplitude. The vector is equiprobable all around the disc. Therefore it is reasonable to represent the probability of the quantum state with

, the

area of the disc. The modulus of the quantum state

is not an area but a

length on the complex plane. It is only natural for a length to be a square-root of an area. Therefore, a probability amplitude is something like a square-root of a probability. That’s one way one might understand the complex probability amplitude.

Why is

a probability

amplitude? Why not simply a probability? As we saw in

Figure 2, one answer is that probability amplitudes and not probabilities lead QM to predict the full set of correct empirical results. If you take

to be a probability, you get wrong answers. Probability amplitudes in QM are complex while probabilities are always real. As discussed above, the full range of physical phenomena can only be incorporated into complex states. Probability amplitudes, moreover, enlarge the field of possible quantum states. They allow, for example, inclusion of quantum states that present the same probability distribution for one observable, but different probability distributions for another. Thus, there are multiple grounds for using complex probability amplitudes rather than real probabilities for quantum states.

b. Quantum State and Information. represents the particle while in the invisible quantum world. preserves physical information about the particle. This includes information the Observer may not measure or even be aware of. As implied above for the Dual-Slit Experiment, the important thing in distinguishing between exclusive and interfering alternatives is not whether or not one knows the path a particle has taken but whether or not that information is knowable. conveys the information from one measurement to the next. Whether embodies all knowable information about the particle or whether there could be additional information lurking somewhere outside the quantum state is a matter of debate in QM. has both physical and aphysical, purely mathematical aspects. Physically, is the QM version of the CM state of a particle. It is a function of the particle species, particle properties, and experimental conditions. vests some of the information it carries into the macroscopic world each time we measure an observable on the particle. This occurs solely in the form of one of the eigenvalues of the observable. Even there which eigenvalues can be measured is determined by the observable. Apart from some input into the number of eigenstates, mainly influences the probability of observing each eigenvalue. If we reserve the word “physical” to things we can measure, is also aphysical as information and probabilities are arguably aphysical entities. Moreover, between measurements, dwells in a quantum world that is in part fundamentally obscure to measurement.

c. Physical or Aphysical? The aphysical side of pertains to the selection of which eigenvalue emerges in any single experimental run. On the one hand, we only obtain the eigenvalue for the observable we opt to measure (Process 2). On the other hand, the eigenvalue we get is a random choice out of the full set of eigenvalues the observable has to offer (Process 1). In this sense, QM measurement is like a random function . Neuroscientists will recall such functions from statistics. Rather than a fixed value of , each put in returns a value randomly selected from the range of , e.g., . In QM, the selection is from the range of eigenvalues. implements this random choice by carrying within itself the probability distribution for all the eigenstates. This distribution comes out of the projection of onto each of the eigenstates supplied by the apparatus, by the observable. (We shall occasionally use “apparatus” and “observable” interchangeably, but note that some apparatuses can measure multiple observables.) And probability is a mathematical construct. Probability is directly related to Shannon information (Shannon 1948), the latter is essentially “improbability”. In neuroscience, Rolls (2016) gives an example of how aphysical information, and therefore probability, can be. The information provided by the answer to the question “Where is Reading with respect to London?” increases progressively as the question is phrased “East or West?”, “North, East, South, or West?”, “North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, or Northwest?”, and so on. I.e., it depends on the context, the arbitrary coordinate system imposed by the question. This is similar to the way the result of a QM experiment depends on which question is asked, on the apparatus. So one can take the point-of-view that probability and are devoid of physical significance. (Since this aphysical side of exists, QM is sometimes called a “mathematical” rather than a “physical” theory.) As it is impossible to fill the gaps in knowledge about between measurements with hard data, QM fills them with probability, creature of mathematical fancy. But mathematics, fortunately, is a systematic way to be fanciful. models the particle systematically by retaining physical information vested in it during its history (preparation, past measurements,…) whilst rigorously respecting the random character of its future behavior.

Meanwhile, there are reasons to think of as physical. As mentioned, like a CM physical state, a quantum state by definition must be something that somehow affects experimental outcomes; in QM the effect is via probability, but there is an effect nonetheless. Also, is often formulated explicitly as a function of a physical variable The dependence of on these physical variables is evidence that itself is physical. As mentioned, the quantum state of a particle carries (perhaps unpopulated) degrees-of-freedom with itself as the particle travels thru space-time. These degrees-of-freedom can be filled with bona fide physical quantities like energy, momentum,… This is further evidence for a physical side of . Like a vector, the quantum state exists independently from the various coordinate systems we choose to cast it in. It even carries knowledge about the quantum system that we may, at least momentarily, be unaware of. These factors also hint at an objective, independent physical existence for . There are further arguments one could advance, which we shall not go into. Our conclusion is that is an ontologico-epistemological hybrid (compare Halvorson 2019).

A QM experiment manifests the actual and, in so doing, takes a slice, a projection, of a quantum state which spans not the actual, but the possible. The possible space that spans is an epistemological space, i.e., a space of what we can know, of what can be made actually manifest. But the fact that can be made manifest from every projection angle implies that is also ontological. Furthermore, one can argue (Bowman 2008) that not only quantum states but also QM operators have ontological character since they carry their eigenvectors and eigenvalues around with them to apply them to arbitrary state vectors.

Comment 6: CM phenomena like waves in fluids like water are well described with complex amplitudes. In CM, complex amplitudes reflect actual physical properties like the height of water above baseline, but their use is considered a mere mathematical convenience. In QM, complex amplitudes represent plausibly aphysical “square-roots of probabilities” and it is debated whether their use is a convenience or reflects intrinsic reality. To strengthen the motivation for using complex probability amplitudes in QM, let us play a variation on a theme by Stuart Kaufman. Imagine we are pondering the whereabouts of a friend on the road. We say, “He is in Albuquerque”. Thence, everyone agrees, “He is not in Santa Fe”. It would be rare, but equally valid, to say, “If he were in Albuquerque, he would not be in Santa Fe.” I.e., logically, conditional statements can also be mutually exclusive. Now if we shift from possibilities to probabilities we can say, “the more he could be in Albuquerque, the less he would be in Santa Fe.” This has something of the flavor of complex probability amplitudes in QM. Quantitatively, they implement reinforcing and diminishing relationships of available possible, but not yet experimentally realized, states of a quantum system.

Comment 7: A further point. Natural languages, e.g., Latin, German, English,… can subtly influence our grasp of the physical world. Arguably, the Theory of Relativity, for example, advanced physics by overcoming certain unspoken prejudices inherent in everyday language. In Latin, German, English,,,, space and time are baked into syntax in various ways. The adverbs “Where?” and “When?” have separate special roles. Verbs are conjugated by time, not by place. One distinguishes temporal vs. locative prepositions. And so on. But Special Relativity proffers space-time. A Where can become a When, a When can become a Where in defiance of the semantic implications of the foregoing grammatical conventions. Similarly, in everyday language, things, designated by nouns, occupy and move thru space and emerge, persist, and fade over time. Actions, designated by verbs, occupy time and are suffered by or undertaken by things. But in Special Relativity mass, characteristic of things, is equivalent to energy, characteristic of actions. QM, peradventure, extends this process. Everyday language predisposes us to contrast things that are for certain (indicative mood) vs. things that are not but could be (conditional mood). Perhaps the efficacy of QM complex probability amplitudes in making accurate empirical predictions is telling us that Nature speaks not only in the indicative but also in the conditional mood. This idea is not as capricious as it may sound. QM typically deals with systems so small, so fast, etc. we can barely measure them. QM stands routinely at the Heisenberg Limits. We are not quite sure whether a particle in this realm is really there or not. It flits on the edge of existence. Yet, the invisible properties of such particles undeniably influence real macroscopic events in the world, manifest thru particle eigenvalues. Hence, it seems reasonable to surmise that Nature speaks indicative mood for post-measurement eigenvalues, but conditional mood for probability amplitudes between measurements.

Comment 8: A metaphysical double-humility underlies QM. On the one hand, QM insists reality has an unavoidable subjective component (Process 2); we humans can never assume a “God’s eye view” of complete neutrality in observing the world. On the other hand, thru quantum randomness (Process 1) QM retains Material Objectivity. Within the limits of particle species and experimental conditions, the objective quantum system acts as it pleases. It is epistemologically impossible for us to know exactly what that is in advance. Thus, QM produces a pleasing paradox that addresses the ancient philosophical question: Is the world objective or subjective? Our measurement interventions represent an irrepressible subjective component of reality that nudges Nature to act in a random way beyond our control, i.e., objectively. Thus, we are humbled in that we cannot avoid interfering in Nature

and in that there are aspects of Nature beyond our control.

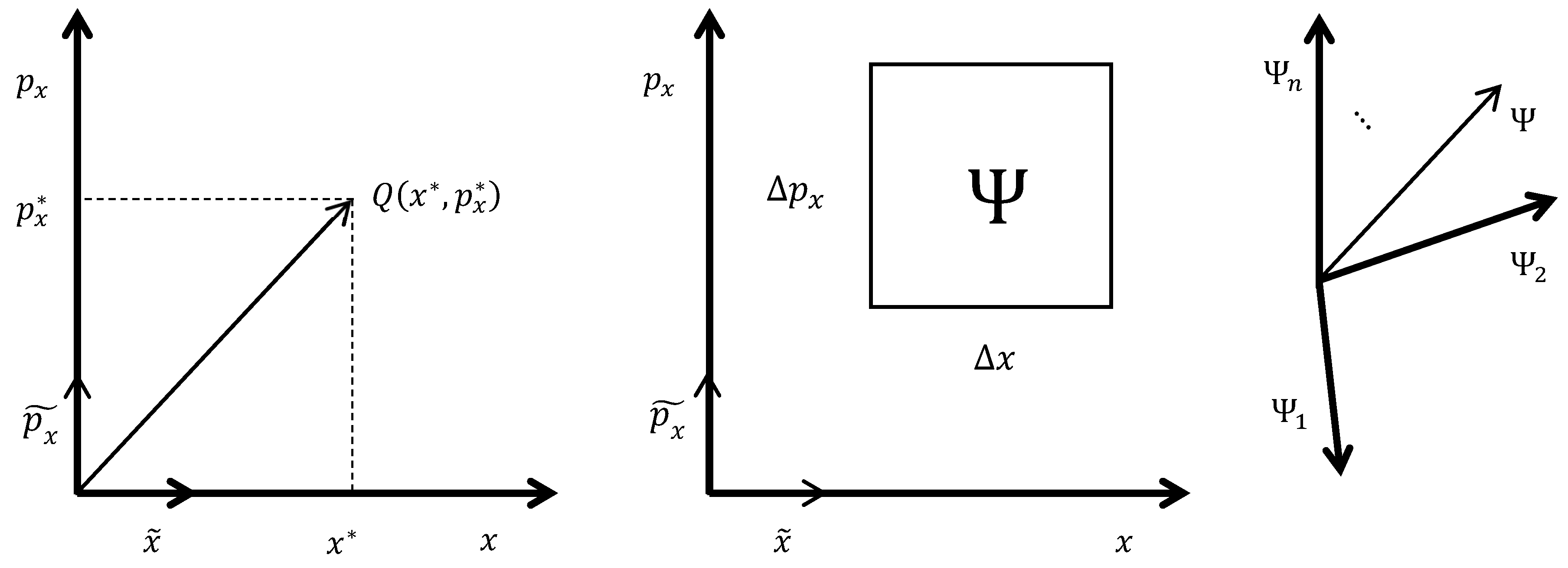

Figure 6.

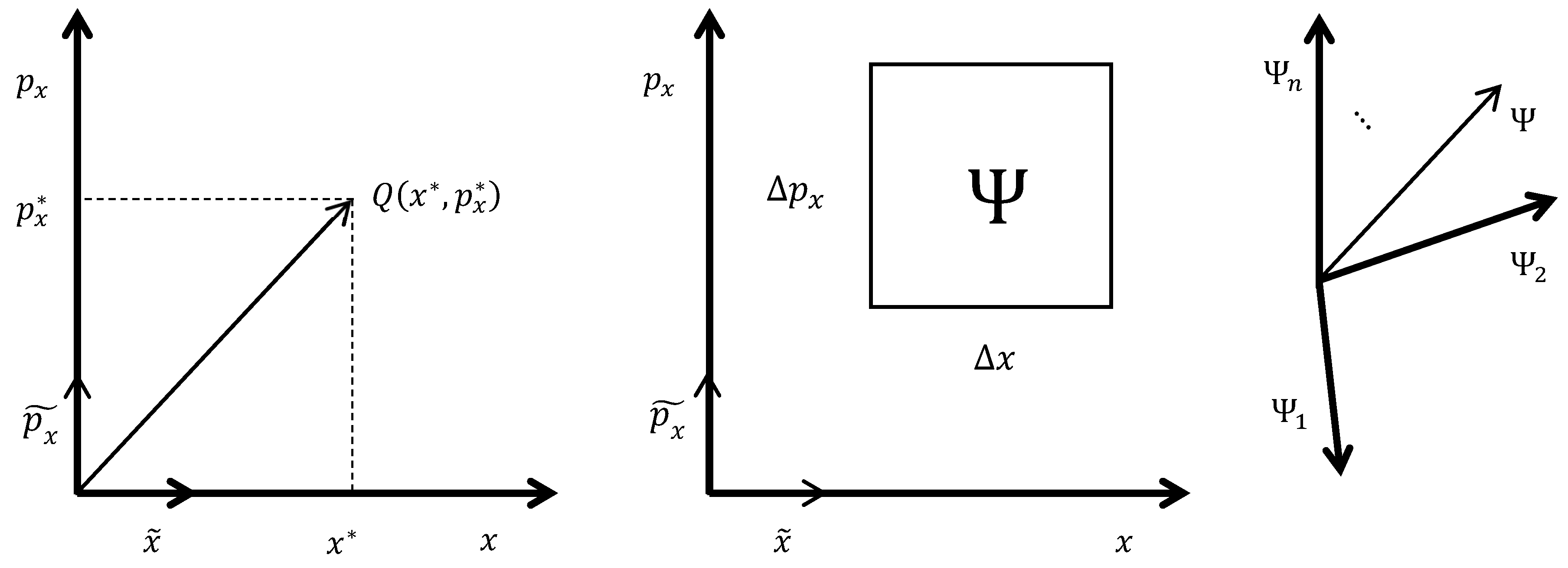

(Left) position-momentum phase-space in CM for a single particle moving back-and-forth in one dimension with momentum . The phase-space is sectioned by a coordinate system (basis) with - and -axes. For particles in 3D, there are three dimensions of position and three of momentum per particle, for axes total in the basis. In 2D, we measure the value pair . That tells us the system occupies physical state . Ideally, when the uncertainties of both and are zero, the state is a point in phase-space. Each point is a different state of the system. Phase-spaces are linear vector spaces, so each point is also a vector (unique arrow from the Origin), like that to . The vectors and along the coordinate axes are perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other, linearly independent (li) from each other. For convenience, they are normalized (unit vectors; “~”), i.e., each divided by a constant to make its length equal 1. Linear combinations (sums of multiples) of and can generate any point in the 2D space. Any set of basis-vectors that can recreate the space that way is called a complete set or a basis. To span (recreate) the vector space, the number of basis-vectors must equal at least the dimension of the space and all basis-vectors must be li. When all basis-vectors are li and normalized, they form an orthonormal basis. (Center) the same phase-space for a QM particle. Now we cannot measure any variable pair exactly. Rather their uncertainties map-out a region in phase-space. The Uncertainty Principle specifies . Hence, the minimum area of the region is . One can draw similar boxes for and other non-commuting observable pairs. The quantum state occupied by the particle lives inside the box, a quantum world fundamentally invisible to humans and their instruments. (Right) all possible quantum states the particle could occupy are mapped out in a Hilbert space, the QM version of phase-space. Every quantum system has a Hilbert space. The dimension of a Hilbert space is the minimum number of li subspaces needed to span it, i.e., the size of its basis. It also equals the sum across species of the degrees-of-freedom (independent quantum states) per particle times the number of particles in the system. ranges 2-. (The figure shows a finite for illustrative purposes, but, in actuality, the Supermicroscope has .) The subspaces in a basis are typically rays, i.e., axes or 1D-subspaces, each spanned by a unit vector. Each subspace is a quantum state unto itself. Infinitely many different bases span a Hilbert space; one need merely pick another set of li axes for an equally valid alternative basis. Commonly, the basis chosen is one made-up of the eigenstates of whatever measurement variable (observable) is currently being measured. Any quantum state in the Hilbert space can be resolved into these eigenstates .

Figure 6.

(Left) position-momentum phase-space in CM for a single particle moving back-and-forth in one dimension with momentum . The phase-space is sectioned by a coordinate system (basis) with - and -axes. For particles in 3D, there are three dimensions of position and three of momentum per particle, for axes total in the basis. In 2D, we measure the value pair . That tells us the system occupies physical state . Ideally, when the uncertainties of both and are zero, the state is a point in phase-space. Each point is a different state of the system. Phase-spaces are linear vector spaces, so each point is also a vector (unique arrow from the Origin), like that to . The vectors and along the coordinate axes are perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other, linearly independent (li) from each other. For convenience, they are normalized (unit vectors; “~”), i.e., each divided by a constant to make its length equal 1. Linear combinations (sums of multiples) of and can generate any point in the 2D space. Any set of basis-vectors that can recreate the space that way is called a complete set or a basis. To span (recreate) the vector space, the number of basis-vectors must equal at least the dimension of the space and all basis-vectors must be li. When all basis-vectors are li and normalized, they form an orthonormal basis. (Center) the same phase-space for a QM particle. Now we cannot measure any variable pair exactly. Rather their uncertainties map-out a region in phase-space. The Uncertainty Principle specifies . Hence, the minimum area of the region is . One can draw similar boxes for and other non-commuting observable pairs. The quantum state occupied by the particle lives inside the box, a quantum world fundamentally invisible to humans and their instruments. (Right) all possible quantum states the particle could occupy are mapped out in a Hilbert space, the QM version of phase-space. Every quantum system has a Hilbert space. The dimension of a Hilbert space is the minimum number of li subspaces needed to span it, i.e., the size of its basis. It also equals the sum across species of the degrees-of-freedom (independent quantum states) per particle times the number of particles in the system. ranges 2-. (The figure shows a finite for illustrative purposes, but, in actuality, the Supermicroscope has .) The subspaces in a basis are typically rays, i.e., axes or 1D-subspaces, each spanned by a unit vector. Each subspace is a quantum state unto itself. Infinitely many different bases span a Hilbert space; one need merely pick another set of li axes for an equally valid alternative basis. Commonly, the basis chosen is one made-up of the eigenstates of whatever measurement variable (observable) is currently being measured. Any quantum state in the Hilbert space can be resolved into these eigenstates .

F. State Space

1. CM Phase-Space. How QM arises from the Uncertainty Principle is illustrated with an idea (

Figure 6) of Planck’s (1916). To understand this, we first discuss CM

phase-space, or

state space. State spaces are much used in thermodynamics, Planck’s field. Every CM system has an abstract state space “floating alongside” the actual physical space occupied by the system.

Figure 6 shows the state space for a single particle in the Supermicroscope of

Figure 3. It has two axes (two dimensions) for the two degrees-of-freedom of the particle. One axis is for position

(back-and-forth along a straight line); the other for momentum

. For

particles moving in 3D, instead of one particle in 1D, we would have three coordinate axes for the position

and three for the momentum

of each particle in the system. Hence, the state space would have

axes. Further axes, e.g., if there are electromagnetic fields, are added as relevant. Going back to

Figure 6, in the ideal CM case, both

and

can be measured exactly. Thus, at any time

they specify a

point in state space, the state

, of the particle. If desired, one can reslice the space into different axes and express the state in terms of a new pair of variables, e.g.,

. Thereby, only the axes change, the point (the state itself) remains the same. For the physical information the state carries about the particle includes information not expressed explicitly, perhaps even unknown to the Observer. Each point represents a different state and the space is the collection of all possible states the system

could occupy.

In

linear algebra, the second major branch of mathematics used in QM, CM state space is a

linear vector space. It consists of points and coordinate axes. One deep insight of linear algebra regards points: each point in a vector space is analogous to a

vector is analogous to a

function. It is easy to see that points are related to vectors. A vector is a directed line segment (arrow) from the Origin to the point in question, e.g., the vector to

in

Figure 6. Points and vectors are equivalent as there is one and only one vector to each (and every) point in a space. Indeed, one often denotes a vector by the coordinates of its point, e.g.,

. But how do points relate to functions? Well, point

in

Figure 6 is labelled explicitly as a function

. Every point in the space could be labelled that way, its coordinates serving as the argument of the function. A unique state is assigned to each point like the one-to-one correspondence between points and values of a function. Readers may recall this idea from the elementary definition of a function

: “

is a rule assigning to every point

another point

“. In QM and elsewhere one can, moreover, define vector spaces called

function spaces, in which each vector is a function, like

or

, rather than an ordered row or column of numbers like

. Thus, points, vectors, and functions in vector spaces are intimately connected.

A second deep insight of linear algebra is that coordinate systems are analogous to matrices are analogous to operators (transforms). A coordinate system or complete set of axes, also called a

representation, is a way of mapping out a linear vector space. The Observer, especially in QM, has freedom in choosing a representation, with a couple restrictions we get into below. In choosing each axis, we assign a

basis-vector rooted at the Origin and parallel to that axis. The axis itself is a

ray, a 1D subspace of the vector space. (Vector spaces can also have 2D and higher-dimensional subspaces with multiple basis-vectors, but we touch on this only lightly.) Any point along a ray between 0 and

may serve as basis-vector. But it is convenient to normalize each basis-vector, i.e., to multiply it by a constant that makes its length equal 1, in the units of the axis. The first restriction is that all the basis-vectors be mutually li, i.e., orthogonal. It means no one basis-vector is a linear combination (sum of non-zero multiples) of any or all of the others. The physical correlate of this restriction in CM is that each axis of the state space represent an

independent measurement variable. E.g, no basis-vector should be simply a double or half of another, nor the simple sum of two other basis-vectors, etc. The second restriction is that the basis (the full complement of basis-vectors)

span the space. I.e., by linear combinations of one to all basis-vectors it should be possible to generate every point in the space. Moreover, the basis should contain the

minimum number of vectors needed to span the space. The physical correlate of this restriction is that a state space should accommodate any conceivable combination of measurement results that could come up in Nature (completeness) without

a priori bias towards or against any of them (objectivity). If our basis is both orthogonal and normalized, we call it orthonormal. The vector pair

in

Figure 6 is an orthonormal basis. A complete set of basis-vectors clearly forms a coordinate system. These basis-vectors can also easily be arrayed one-by-one into the rows or columns of a matrix. So we see how matrices and coordinate systems are equivalent. Operators, like

in

, are functions-of-functions. Each function

fed into

yields a unique function

. Matrices, like

in

, carry out operations or transformations on a vector

when they left-multiply it, producing a unique vector

. We’ve already said that vectors are equivalent to functions, so clearly a matrix is equivalent to a kind of function-of-functions, an operator. Transformations perfomed include such things as rescaling the length of

, rotating it, inverting it, and more complicated effects. A further subtle insight underscores the equivalence of operators, matrices, and coordinate systems. From one point-of-view, a transform rescales, rotates, etc. a vector

within a fixed coordinate system; but from an equally valid point-of-view,

stays constant while the coordinate system itself is changed by the transformation. From the latter perspective, one can readily assent that a transform in a sense

is a coordinate system. Especially when one contemplates the identity matrix

Identity Matrix (Transform)

The identity matrix, , which leaves every vector fully unchanged, is formally considered a transform unto itself. In QM, especially when working with function spaces, rather than as matrices, we often write operators as analytic expressions, for example, for the position operator or for the momentum operator in the -direction. (We will not go into how these expressions are derived.) Thus, coordinate systems, matrices, and operators in vector spaces are intimately connected.

Comment 9: One technical subtlety of vectors is important to philosophy. Above we said, if we transform to , the state does not change, only the axes. This is an intrinsic quality of vectors (and other tensors), they exist independently from the coordinate system in which they are expressed, and concomitant arbitrary human choices of scale and direction of axes. This independence is one reason for using tensors to denote physical quantities (forces, fields,…) in CM. The objective existence of these quantities free from human whim inheres in the vector space formalism. With the Theory of Relativity, Einstein believed he had attained the age-old philosophical goal of a truly objective model of Nature. This objectivity is implemented in the Theory in part through the tensor formalism. Inverted, this objective quality of tensors implies the existence of human freedom in choosing a set of axes arbitrarily to map out a linear vector space.

2. QM Hilbert Space. Returning to Planck’s idea, consider plotting the state of a quantum system, our particle under the Supermicroscope, on the phase-space of

Figure 6. Even ideally in QM,

and

cannot both be measured exactly together. Instead, each has an uncertainty

. Thus, rather than a point, they specify a

region of area

in state space at time

.

Per Eq. (5) the smallest possible area of this region is

. Between measurements, the system quantum state

dwells in this box unseen. Upon measurement, it manifests as any combination of values in the box of

Figure 6.

Per Planck, CM phase-space is insufficient for quantum systems.

In

lieu of a CM phase-space, every QM system has a Hilbert space (

Figure 6). Unlike CM state space, which is clearly abstract, it is debated whether Hilbert space is abstract or possesses some kind of reality. Like phase-space, Hilbert space is a linear vector space. It consists of vectors (points, functions) and coordinate axes (operators, matrices). Every quantum state

the particle could possibly occupy is a vector in the Hilbert space and every vector in the Hilbert space is a quantum state. Thus, Hilbert space enables one to map quantum states as single points rather than as regions of phase-space. Like a CM state, a quantum state carries physical information about the particle, including information unknown to the Observer. But while a phase-state carries

all the physical information about the particle in CM, whether this is true or not for a quantum state is again debated (Einstein’s hidden variables). Just as a CM transform, e.g., from

in

Figure 6 to

, leaves a CM state unchanged, a transform from one representation to another leaves a QM state

unchanged. For example, one of the probability distributions in

Figure 4 was derived from quantum state

expressed as a function of

,

, the

momentum representation. The selfsame quantum state can be written as

, the

position representation. Each relevant observable for the quantum system, in fact, has its own representation. Each still harbors information about all observables. Thus, its Hilbert space accommodates every quantum state a quantum system could possibly occupy.

Via the quantum state, the Hilbert space indicates the probability distribution for every variable that can be measured for the system.

Like phase-space, a Hilbert space is parcellated by coordinate systems (bases), matrices, or operators. Any vector in Hilbert space spans a ray, the line that runs thru it, a 1D subspace. (Alternatively, the vector, together with one or more others, can span a plane or higher-dimensional subspace.) Every point (every quantum state) along a ray can be converted into every other point by multiplying it by an appropriate constant. (The same applies if the Hilbert space is populated by functions rather than points. Then a ray consists of a set of functions that differ from each other only by multiplicative constants.) Thus, all quantum states in a ray are linearly dependent (ld) on each other. The usual choice to represent the ray as a basis-vector is the unit vector, created by dividing any non-zero vector in the ray by its own magnitude. Any set of li basis-vectors large enough to span the Hilbert space is a basis, a scheme for dividing the space into subspaces. The minimum number of basis-vectors needed is the dimension of the total Hilbert space (). The dimension derives from the particle species (quantum states per particle), the number of particles of each species, and the conditions imposed (e.g., any external fields) for the quantum system. Any basis chosen by the Observer is equally valid. But a very common and useful choice in QM is a basis formed by the eigenstates of whatever observable is curently being measured or discussed. In CM, a measurement variable, an observable is a single axis, a 1D coordinate system insufficient to span the space. A state is specified by the values of multiple observables, each along its own axis. But in QM, an observable is a multi-axis coordinate system. It is a basis for the Hilbert space, a way of dividing it up, a selective (and incomplete) perspective on it. Each axis thereby is a quantum state, in fact an eigenstate of the observable. For an observable is equivalent to a matrix or operator and matrices and operators have eigenstates and eigenvalues.

As we said, in QM Hilbert spaces are typically complex. How does one imagine that? The usual approach is to handle it as a pure mathematical abstraction. But here is one way you might visualize a complex Hilbert space (

Figure 7). The key is to think of a regular rectangular coordinate system, a set of real axes. Each axis represents a different quantum state. But each real axis has its

own extra imaginary axis sticking out orthogonal to it. Rather than, say, there being

real axes for the

quantum states in the basis of an

-dimensional Hilbert space and one imaginary axis shared by all the real axes; no, there are

real and

imaginary axes. The phase of the individual quantum state is the angular displacement in the complex plane from its own real axis towards its own imaginary axis. Since, as discussed, the phase has no effect on the probability distribution of the individual quantum state, it is usual to draw the axes, if one draws them at all, at the zero-phase, i.e., pure real, position. Yet, the phase is significant when one sums quantum states, when quantum states evolve, etc.

G. Measurement, Observables and Other Operators

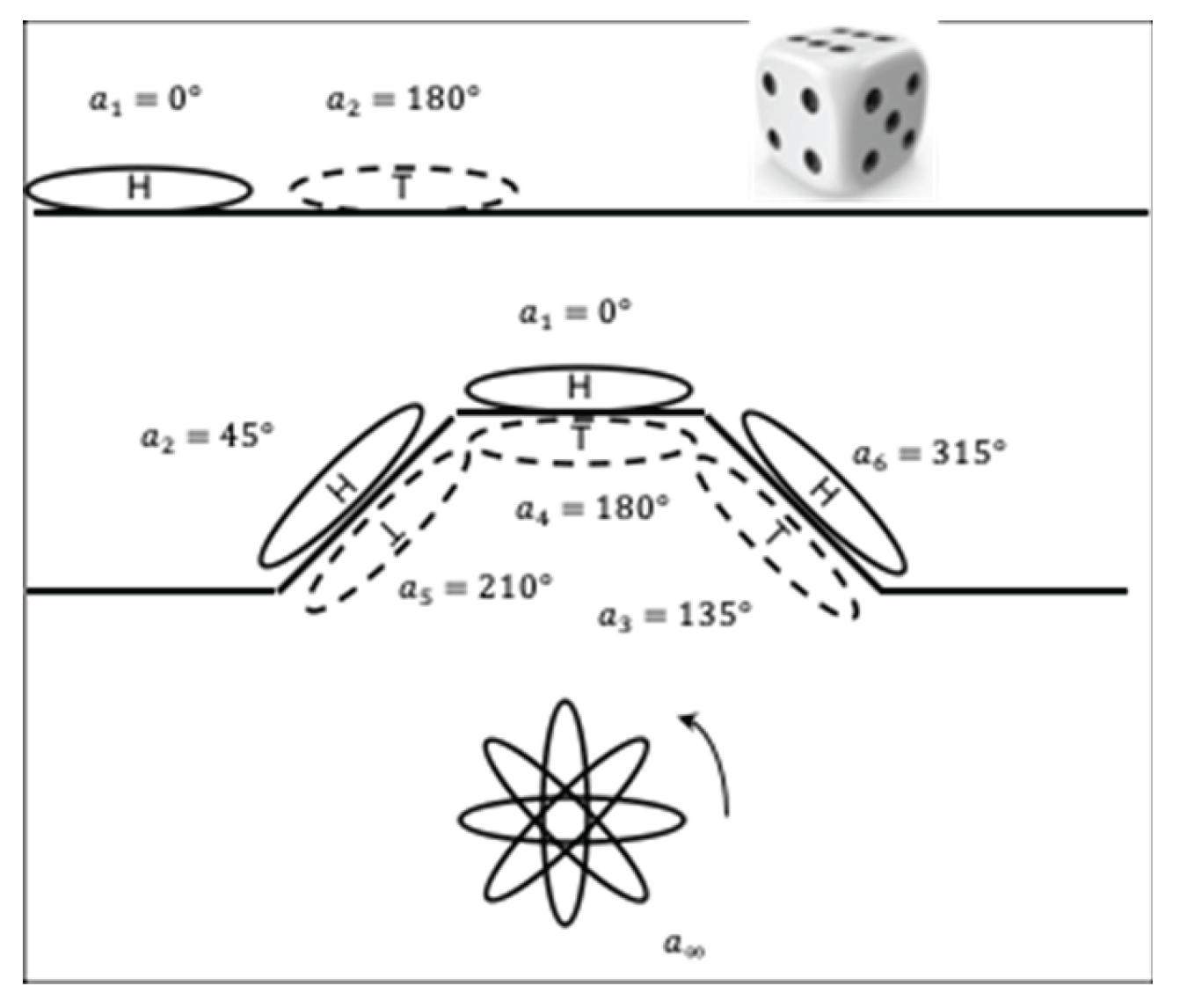

1. Effect of the Apparatus on the Outcome. In

Figure 8, CM scenarios illustrate how an experimental apparatus sets the eigenvalues (possible outcomes) of a QM experiment. Flipping a coin is an everyday act, but also a very simple experiment. The coin is the sample, representing our quantum system. The coin has two different sides, like an electron with spin

. This shows the contribution of the particle species to the possible outcomes. Were the obverse and the reverse of the coin identical, the number of possible outcomes would be halved. The apparatus might consist of the air and a tabletop. This represents the QM observable, the Hermitian operator. The tabletop forces the falling coin into the eigenstates heads (H) with eigenvalue

or tails (T;

), where our outcome is the ccw angle the coin makes with the tabletop. The main point is, whatever angle the coin was landing at just before impacting the table, the flat tabletop forces it into eigenvalue

or

and into eigenstate H or T. The same experiment with a die has six equiprobable outcomes, underlining the fact that the system itself provides the primary probability distribution. As a further scenario, imagine our table has outer wings, slopes, and a plateau (

Figure 8). Then we can measure heads-up states

and tails-up states

. Note that the outer wings enhance the probability of

, by increasing their surface areas. This shows that the apparatus, in addition to setting eigenvalues, can also influence the distribution. Finally, if our apparatus consists of air and a blitz camera, we can capture infinitely many eigenstates of the system (the coin spinning in air) with eigenvalues

.

Comment 10: In O’Neill & Schoth (2023) we introduced an algebra for fractal geometries. There is an analogy between measurement in fractals and QM measurement (including entanglement, Part III). The analogy extends to the extraction of meaning from a mental concept. In each area it involves superimposition of direction and/or scaling onto a system.

Figure 8 illustrates how an apparatus imposes a basis (coordinate frame) onto a QM system. The choice of observable fixes the range of answers to the question posed by the experiment. The allowable eigenstates are preferred coordinate axes and the corresponding eigenvalues are scalings along these axes. A different apparatus (different observable) allows a different set of eigenvalues and eigenvectors. A measurement brings the system state out of a random field of possible answers into a determined state.

Measurements undertaken on fractal systems work rather the same. A famous question (Mandelbrot 1967) in fractals is, “How long is the Coast of Britain?” The answer depends on the size of your ruler. If it is 20 km long, you get a certain value. If it is 10 km, you get a different, larger answer. If it is the size of a boulder, you get a much, much larger answer. If it is the size of a grain of sand, you get an enormously larger answer. And so on. Scale inheres neither in QM nor in fractal systems. Rather it is imposed from outside. The analogy continues in that both fractal and QM systems have internal structure. In QM, we have particle degrees-of-freedom, e.g., possible spin states; in fractals we have the fractal dimension and fixed ratios between segment lengths that hold for all scales. If fractal geometry is intrinsic to Nature (Mandelbrot 1982), then it is perhaps unsurprising that quantum systems, to be measured, require external imposition of scale from the apparatus. That the apparatus imposes scale on the quantum system it measures again reflects a holism of Nature, she does not reval her character in the absence of an apparatus and even then only as gauged by the apparatus.

In outr theory of higher brain functions (O’Neill & Schoth 2023), information similarly possesses internal structure, but is free of meaning. Consciousness must superpose a context onto information in order to extract meaning from it. Meaning is dependent on context similar to the length of a fractal structure depending on the size of the ruler or a QM eigenvalue depending on the choice of measurement variable. In our earlier work, thereby, “context” means applying multiple coordinate (attribute) axes, each with its own scale. Meaning is the answer obtained for the context applied. Further, it is the quantity that gets (or can be) exported for action (behavior). The contrast of the - vs. -representation in QM compares with the sentence vs. context representation of concepts in our theory. Such representation allows calibration of action using the scales of context, including past time context pulled up from memory. Thus, in higher brain functions, in fractals, and in QM, the measured value (eigenvalue) depends on the apparatus.

Comment 11: Smolin (2019) and many others have asked, what is special about measurement? Aren’t measuring devices and the people who use them ultimately made of QM particles that obey the Schrödinger Equation and other QM rules? Here is what is special about QM measurement: To conduct a measurement is to stake an epistemological position. In the Dual-Slit Experiment (

Figure 2), for example, one assumes the two slits are perfectly parallel and perfectly perpendicular to the screen. The slit edges are perfectly sharp and infinitely high. All dimensions remain constant throughout the experiment. The screen registers every arriving electron without error. It is perfectly smooth with uniform properties across its surface. Etc. In reality none of these assumptions are true. There are tiny bumps on the screen, etc. Ultimately, one could pursue all such irregularities down to the quantum level. In actual design, however, they (including quantum effects within the measurement device) are rolled into the

measurement error of the experiment. In principle, at least in the first design stage of a QM experiment, only the subject (the sample) is regarded as quantum; the parts of the measurement apparatus are treated as in

CM. Moreover, in Feynman’s formulation of QM (Feynman & Hibbs 2010), the CM action plays as important a role as the QM action

to which it is characteristically normed.