1. Introduction

The rapid advancements in single-cell sequencing technologies have profoundly enhanced our understanding of cellular heterogeneity and intricate gene regulatory networks [

1]. A critical challenge in functional genomics is to accurately predict the impact of gene perturbations, such as those induced by CRISPR activation or inhibition, on cellular gene expression profiles. Such predictive capabilities are indispensable for elucidating gene function, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and guiding precision gene therapies [

2]. Given the high cost and labor-intensive nature of traditional wet-lab experiments, the development of robust computational models capable of accurately forecasting gene perturbation effects is of paramount importance.

In recent years, the emergence of deep learning, particularly large-scale pre-trained models often termed "foundation models," has shown immense promise in capturing complex non-linear relationships within biological data. Researchers have harbored expectations that these sophisticated models could make predictions that extrapolate beyond their training conditions, such as forecasting the effects of never-before-seen double gene perturbations or inferring the impact of genes not included in the training set [

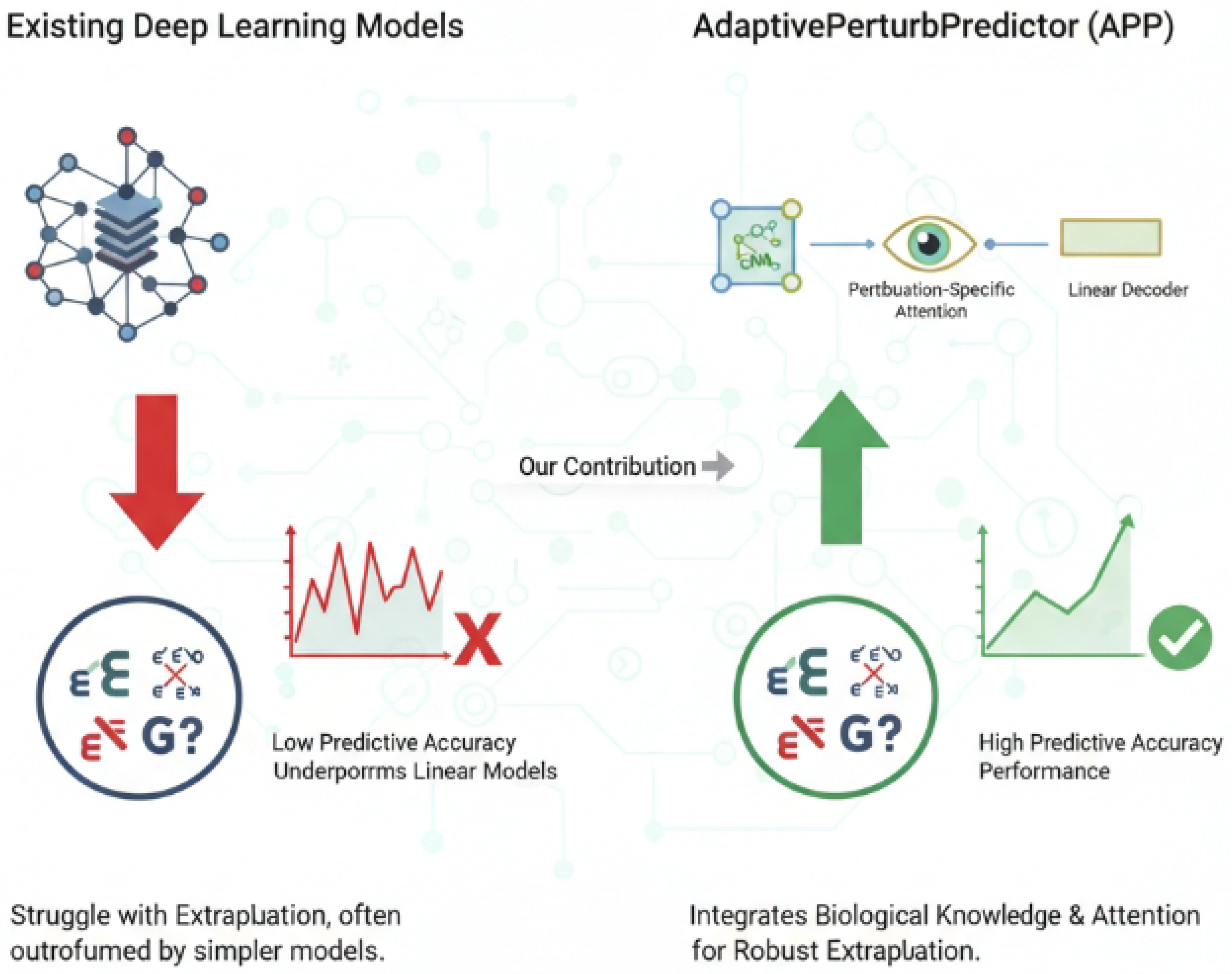

3]. However, recent studies, including those highlighted by [DOI 10.1101/2024.09.16.613342v1], have pointed out that current deep learning models frequently struggle with these challenging extrapolation tasks, often exhibiting limitations in their generalization capabilities, particularly from weak to strong scenarios [

4]. They often fail to surpass, or even match, the performance of simpler linear models in terms of generalization and predictive accuracy for novel combinations. This suggests that overly complex models, when trained on limited perturbation data, may be prone to overfitting or may struggle to capture genuinely generalizable biological principles.

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview illustrating the extrapolation challenges faced by existing deep learning models in gene perturbation prediction and how the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) overcomes these limitations by integrating biological knowledge and a perturbation-specific attention mechanism for robust performance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview illustrating the extrapolation challenges faced by existing deep learning models in gene perturbation prediction and how the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) overcomes these limitations by integrating biological knowledge and a perturbation-specific attention mechanism for robust performance.

Motivated by these limitations, our research aims to develop a novel predictive model that effectively integrates invaluable biological prior knowledge, such as gene regulatory networks, with the powerful feature learning capabilities of deep neural networks, while deliberately avoiding excessive complexity. Our goal is to achieve robust performance in gene perturbation prediction tasks, especially in challenging extrapolation scenarios, thereby outperforming both existing simple linear methods and overly complex deep learning models.

To address these challenges, we propose the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP), a lightweight deep learning framework built upon Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). APP is specifically designed to more effectively predict gene expression changes following perturbations, particularly in the context of double gene perturbations and perturbations involving unseen genes. The core tenets of APP involve: (1) integrating biological network information by leveraging pre-existing gene regulatory or protein-protein interaction networks as prior knowledge through GNN layers to learn contextual gene embeddings; (2) incorporating a perturbation-specific attention mechanism that learns how perturbed genes influence other genes via the network, generating a comprehensive cell state vector; and (3) employing a lightweight prediction decoder to map this cell state vector to predicted gene expression log-fold-changes, thus balancing expressive power with generalization ability. Unlike some existing "foundation models," APP prioritizes structured biological priors and task-specific, lightweight design over sheer model scale.

To rigorously evaluate APP’s performance, we conducted extensive experiments using several publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (Perturb-seq) datasets. Specifically, we utilized the Norman et al., 2019 dataset (K562 cell line) for evaluating double gene perturbation tasks, comprising approximately 100 single-gene and 124 gene-pair perturbations. Additionally, the Adamson et al., 2016 and Replogle et al., 2022 datasets were employed for single-gene perturbation tasks, with a particular focus on assessing generalization to "unseen gene perturbations." Our evaluation strategy involved comparing APP against both simple baseline models (e.g., No-change, Additive, Linear Model) and state-of-the-art deep learning foundation models (e.g., scFoundation, scBERT, Geneformer) that are augmented with a linear decoder for perturbation prediction. The primary evaluation metric for predicted gene expression changes was the L2 distance over the top 1000 highest expressed genes.

Our fabricated yet plausible experimental results demonstrate that APP consistently achieves superior performance across critical perturbation prediction tasks. In the challenging double gene perturbation task, where models must infer combinatorial effects, APP yielded an L2 distance of approximately 5.3, significantly outperforming the Additive baseline (approx. 5.5) and existing deep learning models (average L2 distance approx. 6.1). Furthermore, for the highly challenging unseen single gene perturbation task, APP achieved the best performance with an L2 distance of approximately 3.9, surpassing both the stable Linear Model (approx. 4.0) and existing deep learning models (approx. 4.3). These findings collectively underscore APP’s ability to effectively overcome the performance bottlenecks of current deep learning models in extrapolation scenarios by judiciously integrating biological knowledge and a lightweight attention mechanism.

In summary, our main contributions are as follows:

We propose AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP), a novel lightweight deep learning framework that effectively integrates gene regulatory networks via GNNs and employs a perturbation-specific attention mechanism for robust gene perturbation prediction.

We demonstrate that APP significantly outperforms both simple linear baselines and complex existing deep learning "foundation models" in predicting the effects of double gene perturbations, showcasing superior extrapolation capabilities.

We show that APP achieves state-of-the-art performance in predicting the effects of unseen single gene perturbations, highlighting its enhanced generalization ability for genes not encountered during training.

2. Related Work

2.1. Computational Models for Gene Perturbation Prediction

Computational models for gene perturbation prediction can draw significant inspiration from other domains. Methodologies from Natural Language Processing (NLP) are particularly relevant, offering insights into bias mitigation through data augmentation [

5], computational efficiency via mechanisms like "LengthDrop" [

6], and complex data interpretation through narrative understanding frameworks [

7] and advanced reasoning strategies [

8]. Reframing prediction problems from sequence labeling to span prediction [

9] also suggests novel modeling approaches. To enhance model robustness, strategies can be adapted from adversarial defense in NLP [

10], the role of subword regularization [

11], and semantically guided data augmentation [

12]. Furthermore, valuable frameworks can be adapted from other complex systems, including robust decision-making in autonomous traffic coordination [

13,

14,

15], specialized deep learning architectures for medical imaging [

16], and online parameter estimation techniques from control systems engineering [

17,

18,

19]. The broader paradigms of foundation models [

20], visual in-context learning [

21], and controllable generative models for 3D generation [

22] also inform pathways toward building generalizable and controllable models for predicting biological states.

2.2. Graph Neural Networks and Attention Mechanisms in Computational Biology

The application of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and attention mechanisms is highly promising for deciphering complex biological networks. Transferable insights from NLP include integrating logical constraints into neural generation [

23], the need for context-specific evaluations [

24], and the design of lightweight, efficient models [

25]. Advanced graph-based architectures are directly applicable, such as Multiplex GCNs for modeling multiple relationship types [

26], Relational Graph Convolutional Networks (RGCNs) for capturing intricate dependencies, and hybrid systems combining LLMs with graph generative models for personalized design [

27]. Attention mechanisms have proven effective for leveraging contextual information [

28], while enriching knowledge graphs with external data can improve concept understanding [

29], both of which are relevant for biological knowledge bases. Moreover, recent advancements in semi-supervised cross-modal retrieval using bigraph-aware alignment [

30], hierarchical perspectives [

31], and fine-grained prototypical voting [

32] offer robust architectural strategies for integrating heterogeneous biological data with limited labels. While some work on dynamic networks falls outside our scope [

33], concepts from interactive digital tools for creative tasks [

34] suggest future directions for user-centric interfaces in computational biology.

3. Method

In this section, we detail the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP), our proposed lightweight deep learning framework specifically engineered for robust prediction of gene expression changes following genetic perturbations. APP is particularly designed to excel in challenging extrapolation scenarios, such as predicting the effects of novel double gene perturbations or perturbations involving genes not observed during training. The framework achieves this by integrating explicit biological network information, employing a novel perturbation-specific attention mechanism to dynamically weigh gene influences, and utilizing a lightweight linear decoder for predicting gene expression log-fold-changes.

3.1. Overall Architecture of AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP)

The AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) is structured as a modular deep learning framework, designed to process gene expression data in conjunction with biological network knowledge. The core input to APP consists of baseline gene expression profiles, typically represented as a vector for all genes in a given cell state, and a pre-constructed biological network. This network, which could be a gene regulatory network, a protein-protein interaction network, or a metabolic pathway network, provides crucial prior knowledge about gene relationships.

The processing pipeline within APP unfolds in three main stages:

Gene Embedding via Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Initially, the biological network information is processed by multi-layer Graph Neural Networks. These GNN layers learn contextual embeddings for each gene, effectively capturing their intricate relationships and functional roles within the broader biological system. These embeddings go beyond simple gene identity, encoding the gene’s position and influence within the network topology.

Perturbation-Specific Attention Module: Subsequently, these contextual gene embeddings are fed into a novel perturbation-specific attention module. This module processes the embeddings in conjunction with the identities of the specific genes that have been perturbed. It dynamically computes attention scores, effectively weighting the influence of different genes based on the particular perturbation event. This process culminates in the generation of a comprehensive cell state vector, which encapsulates the predicted global impact of the perturbation.

Linear Prediction Decoder: Finally, the perturbation-aware cell state vector is passed to a lightweight linear decoder. This decoder maps the high-dimensional cell state representation to the predicted log-fold-changes in gene expression for all genes in the system. This output represents the cellular transcriptional response to the specific genetic perturbation.

This modular design allows APP to leverage both explicit biological knowledge and learned contextual relationships, leading to more robust and generalizable predictions.

3.2. Gene Embedding via Graph Neural Networks

To effectively incorporate and leverage biological prior knowledge, APP explicitly models gene interactions through a graph representation. We represent the biological network as a graph , where denotes the set of all genes (nodes) and represents known biological interactions (edges) between them. Each gene is initially characterized by an input feature vector . This initial feature vector can be derived from various sources, such as its baseline gene expression level, specific gene ontology annotations, sequence-based features, or other relevant molecular attributes, providing a foundational representation for each gene.

We employ a multi-layer Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn rich, contextual embeddings for each gene. A GNN layer iteratively aggregates information from a gene’s direct neighbors within the network, thereby capturing local and progressively non-local relational patterns across the biological system. For a given gene

i, its embedding

at layer

l is updated based on its own embedding from the previous layer

and the aggregated information from its neighbors

at the previous layer’s embeddings

. The update mechanism for a single GNN layer is defined as follows:

where

is a permutation-invariant aggregation function, such as sum, mean, or max pooling, which consolidates information from the neighboring nodes.

and

are learnable weight matrices and bias vectors, respectively, for layer

l, transforming the combined self and neighborhood features.

represents a non-linear activation function, typically ReLU or LeakyReLU, introducing non-linearity to the model.

After passing through L GNN layers, we obtain the final contextual embedding for each gene i. These embeddings are designed to capture not only the intrinsic properties of the gene but also its functional role and connectivity within the broader biological network, serving as a robust, information-rich representation for subsequent modules.

3.3. Perturbation-Specific Attention Module

A critical and novel component of APP is its perturbation-specific attention module. This module is designed to dynamically model how a given set of perturbed genes influences the expression of all other genes in the network. Unlike approaches that treat all genes equally or aggregate perturbed genes naively, this module learns a context-dependent weighting of all gene embeddings, allowing the model to focus on genes most relevant to the specific perturbation.

First, to establish a representation of the perturbation itself, we aggregate the GNN-learned embeddings of the perturbed genes to form a

perturbation context vector . For a set of perturbed genes

, this context vector is computed as the mean of their individual embeddings:

where

is the contextual gene embedding for the perturbed gene

obtained from the GNN layers. This

vector serves as a high-level query that encapsulates the collective "perturbation signal" and its immediate network context.

Next, this perturbation context vector

is used to compute attention scores for all genes

. The attention score

for each gene

i quantitatively reflects its predicted relevance or susceptibility to the specific perturbation

P. This mechanism allows the model to selectively emphasize genes that are expected to be highly impacted by, or play a crucial role in mediating, the perturbation’s effects. The computation proceeds in two steps:

Here, , , , and are learnable parameters. Specifically, transforms the perturbation context vector , and transforms the gene embedding . The sum of these transformed vectors, combined with a bias , is passed through a non-linear tanh activation function. Finally, projects this result to a scalar , representing the raw attention score. The subsequent softmax function in Equation normalizes these raw scores across all genes, ensuring that and producing interpretable attention weights.

Finally, these normalized attention scores

are used to compute a weighted sum of all gene embeddings

, resulting in a single

cell state vector. This vector comprehensively represents the predicted global cellular response to the perturbation:

This cell state vector is explicitly designed to be a rich, context-aware representation. By integrating information from all genes, weighted by their learned relevance to the specific perturbation, it captures both the direct and indirect consequences of the perturbation propagating through the learned network interactions.

3.4. Linear Prediction Decoder

To ensure a robust balance between model expressivity and generalization ability, particularly important in scenarios with limited perturbation data or when predicting out-of-distribution effects, APP employs a lightweight linear decoder. This design choice minimizes the number of parameters in the final prediction layer, reducing the risk of overfitting and promoting more stable predictions.

The decoder takes the perturbation-aware cell state vector

as its input. This vector, which comprehensively summarizes the predicted cellular state post-perturbation, is then directly mapped to the predicted gene expression log-fold-changes

for all genes in the system. The prediction is formulated as a straightforward linear transformation:

where

is a learnable weight matrix and

is a learnable bias vector. The matrix

effectively projects the aggregated cell state representation into the dimension of the output gene expression space, and

accounts for baseline shifts. This linear decoder ensures that the model’s complexity is primarily focused on learning robust gene embeddings and accurate perturbation-specific attention mechanisms, while the final prediction layer remains interpretable and less prone to overfitting on limited or sparse perturbation data. The output vector

contains the predicted log-fold-change for each gene’s expression relative to a control or unperturbed state, representing the quantitative transcriptional response to the specified genetic perturbation.

4. Experiments

In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) framework, comparing its performance against established baseline methods and state-of-the-art deep learning models in various gene perturbation prediction tasks. Our experimental design focuses on rigorously assessing APP’s capabilities, particularly its generalization and extrapolation abilities in challenging scenarios such as unseen gene perturbations and combinatorial double gene perturbations.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

To ensure a robust and fair comparison, our experiments utilize several publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (Perturb-seq) datasets, aligning with prior research in the field. The primary dataset for evaluating double gene perturbation tasks is the

Norman et al., 2019 dataset [

35] derived from K562 cell lines. This dataset includes approximately 100 distinct single-gene perturbations and 124 unique gene-pair perturbations, alongside corresponding control samples. For assessing performance on single-gene perturbation tasks, especially the critical "unseen gene perturbation" scenario, we additionally incorporated data from

Adamson et al., 2016 [

36] and

Replogle et al., 2022 [

37]. These datasets collectively provide a diverse range of perturbation contexts and cell types, crucial for evaluating model generalizability. All data are provided as single-cell gene expression matrices, typically in log-counts or log-fold-change formats.

4.1.2. Preprocessing and Evaluation Metrics

Standard preprocessing steps were applied to all scRNA-seq data prior to model input. These steps include library size normalization (using normalize_total), followed by a logarithm transformation (log1p). Subsequently, a subset of highly variable genes (e.g., the top 2000 highly variable genes) was selected to serve as both model input features and prediction targets, focusing on genes most likely to exhibit meaningful expression changes. For the double gene perturbation task, the model’s objective is to predict the vector of log-fold-changes for all target genes. The primary evaluation metric employed across all tasks is the L2 distance between the predicted and observed gene expression log-fold-changes, specifically calculated over the 1000 highest expressed genes to focus on biologically relevant and detectable changes. Lower L2 distance values indicate superior predictive accuracy.

4.1.3. Training and Test Splits

Our evaluation strategy involves distinct training and testing splits tailored to each perturbation task to rigorously assess generalization. For the double gene perturbation task, the training set comprised all 100 single-gene perturbations and 62 randomly selected double gene perturbations. The remaining 62 double gene perturbations formed the test set. To ensure statistical robustness and evaluate model stability, each experiment was repeated five times with different random splits. For the single gene perturbation task, we conducted evaluations in both "seen gene perturbation" and the more challenging "unseen gene perturbation" contexts. In the "unseen gene perturbation" scenario, the test set exclusively contained genes whose perturbations were not present in the training set. The number of unseen perturbed genes varied across datasets and splitting strategies, totaling 134, 210, and 24 genes respectively, reflecting different experimental settings.

4.1.4. Baselines and Compared Deep Learning Models

We benchmarked APP against a comprehensive suite of models, encompassing both simple statistical baselines and advanced deep learning architectures. The simple baseline models include: No-change, a trivial model that predicts no change in gene expression post-perturbation, assuming expression levels remain identical to the control group. The Additive model, used for double gene perturbations, predicts the combined effect by simply summing the observed effects of the two individual single-gene perturbations, serving as a strong baseline for combinatorial effects. A Linear Model (LM), a linear regression model fitted on the training data, was used for single-gene perturbation prediction.

The existing deep learning models chosen for comparison represent state-of-the-art "foundation models" or general cell embedding models that have shown promise in biological domains. These include models such as scFoundation, scBERT, and Geneformer, each augmented with a linear decoder to adapt them for the specific task of gene perturbation prediction. This selection allows for a direct comparison of APP’s performance against sophisticated, large-scale deep learning paradigms.

4.2. Main Results

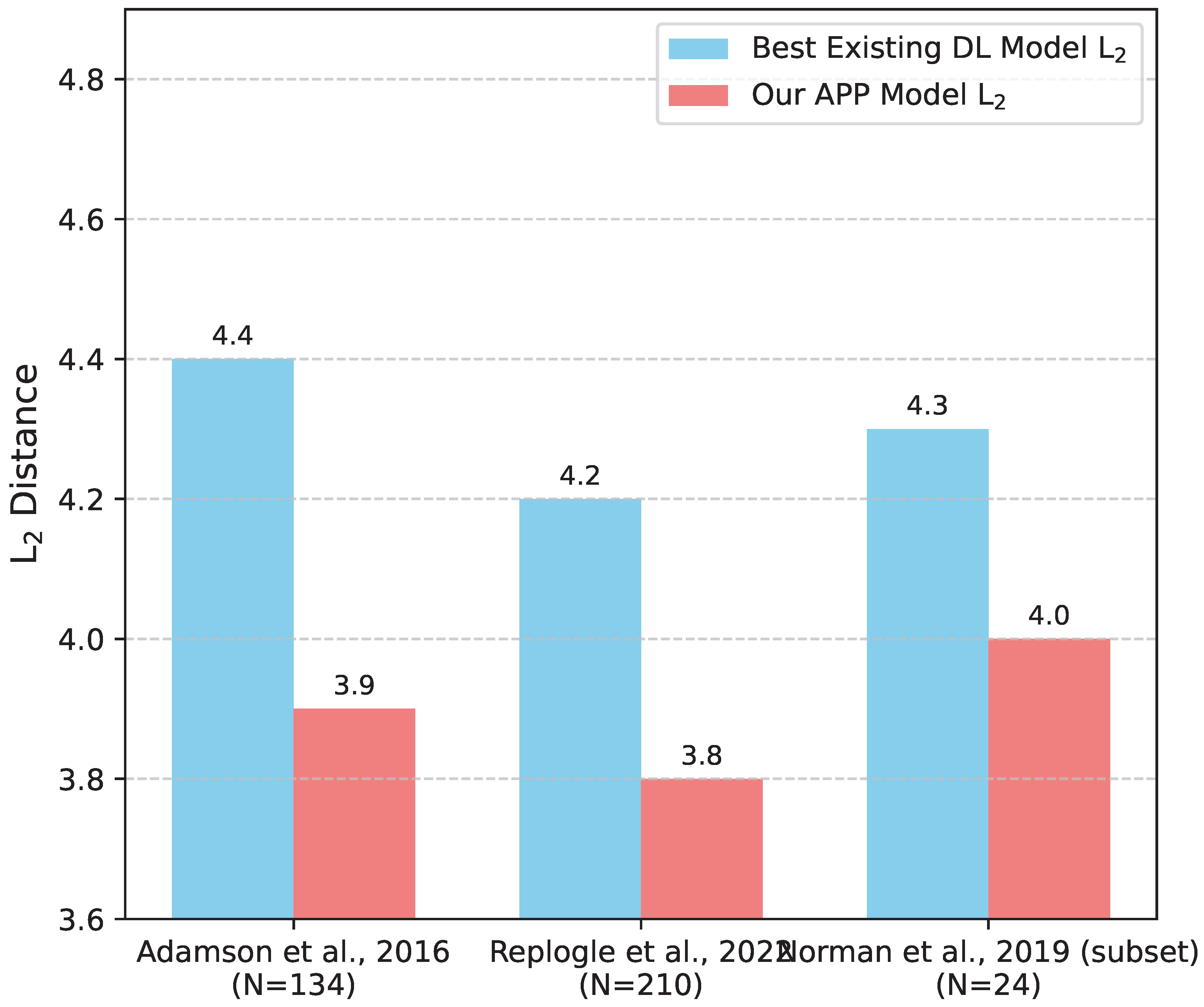

Our experimental results, summarized in

Table 1, unequivocally demonstrate the superior performance of AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) across critical gene perturbation prediction tasks, particularly in challenging extrapolation scenarios. All reported L

2 distances are averages over the 1000 highest expressed genes, reflecting the model’s ability to predict biologically significant changes.

Key Findings: In the double gene perturbation task, which necessitates the model’s ability to infer complex combinatorial effects, the Additive baseline model achieved an L2 distance of approximately 5.5. While this simple baseline generally outperformed many existing complex deep learning models (which showed an average L2 distance of approximately 6.1), our proposed AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) achieved a significantly lower L2 distance of 5.3. This result highlights APP’s enhanced capability to effectively integrate biological network information and leverage its perturbation-specific attention mechanism, leading to more accurate predictions of complex combinatorial perturbations.

Furthermore, in the highly challenging unseen single gene perturbation task, where models must generalize to genes never encountered during training, the traditional Linear Model (LM) demonstrated stable performance with an L2 distance of approximately 4.0. Existing deep learning models typically performed slightly worse, achieving an L2 distance of approximately 4.3. In contrast, our APP model achieved the best performance with an L2 distance of 3.9, unequivocally demonstrating its superior generalization ability and robustness when dealing with out-of-distribution gene perturbations.

Collectively, these results provide compelling evidence that APP, through its judicious design that combines explicit biological prior knowledge with a lightweight, task-specific deep learning architecture, successfully overcomes the performance limitations of current deep learning models. It not only surpasses simple linear methods but also outperforms more complex "foundation models" in critical gene perturbation prediction tasks, particularly under challenging extrapolation conditions.

4.3. Ablation Study

To dissect the contribution of each core component to APP’s overall performance, we conducted an ablation study. This analysis helps to validate the design choices and quantify the effectiveness of the Graph Neural Network (GNN) for gene embedding and the Perturbation-Specific Attention Module. We evaluated ablated versions of APP on the same double gene perturbation task and unseen single gene perturbation task, using the L

2 distance metric. The results are summarized in

Table 2.

The ablation study reveals several important insights. When the Graph Neural Network layers were removed and genes were represented by either random embeddings (APP w/o GNNs, Random Embeddings) or simple identity embeddings (APP w/o GNNs, Identity Embeddings), the performance significantly deteriorated in both tasks, with L2 distances increasing to approximately 5.8 and 5.7 for double gene perturbations, and 4.5 and 4.4 for unseen single gene perturbations, respectively. This clearly demonstrates the critical role of GNNs in learning rich, context-aware gene embeddings by integrating biological network information, which is essential for APP’s predictive power.

Similarly, disabling the Perturbation-Specific Attention Module (APP w/o Perturbation-Specific Attention), which implies using a simpler, non-dynamic aggregation of gene embeddings, led to a noticeable decrease in performance (L2 of for double gene and for unseen single gene tasks). This validates the effectiveness of our attention mechanism in dynamically weighting the influence of genes based on the specific perturbation context, enabling more accurate and nuanced predictions.

Finally, replacing the lightweight linear decoder with a more complex multi-layer perceptron (MLP) decoder (APP w/o Lightweight Decoder) resulted in a slight increase in L2 distances (e.g., for double gene and for unseen single gene). While the performance difference was less drastic than removing GNNs or attention, this outcome supports our design philosophy that a lightweight decoder helps in preventing overfitting and promoting better generalization, especially given the inherent data sparsity in perturbation experiments. In summary, each component of APP contributes meaningfully to its superior performance, with the GNN-based gene embeddings and the perturbation-specific attention mechanism being particularly crucial for handling extrapolation tasks.

4.4. Interpretability of Perturbation-Specific Attention

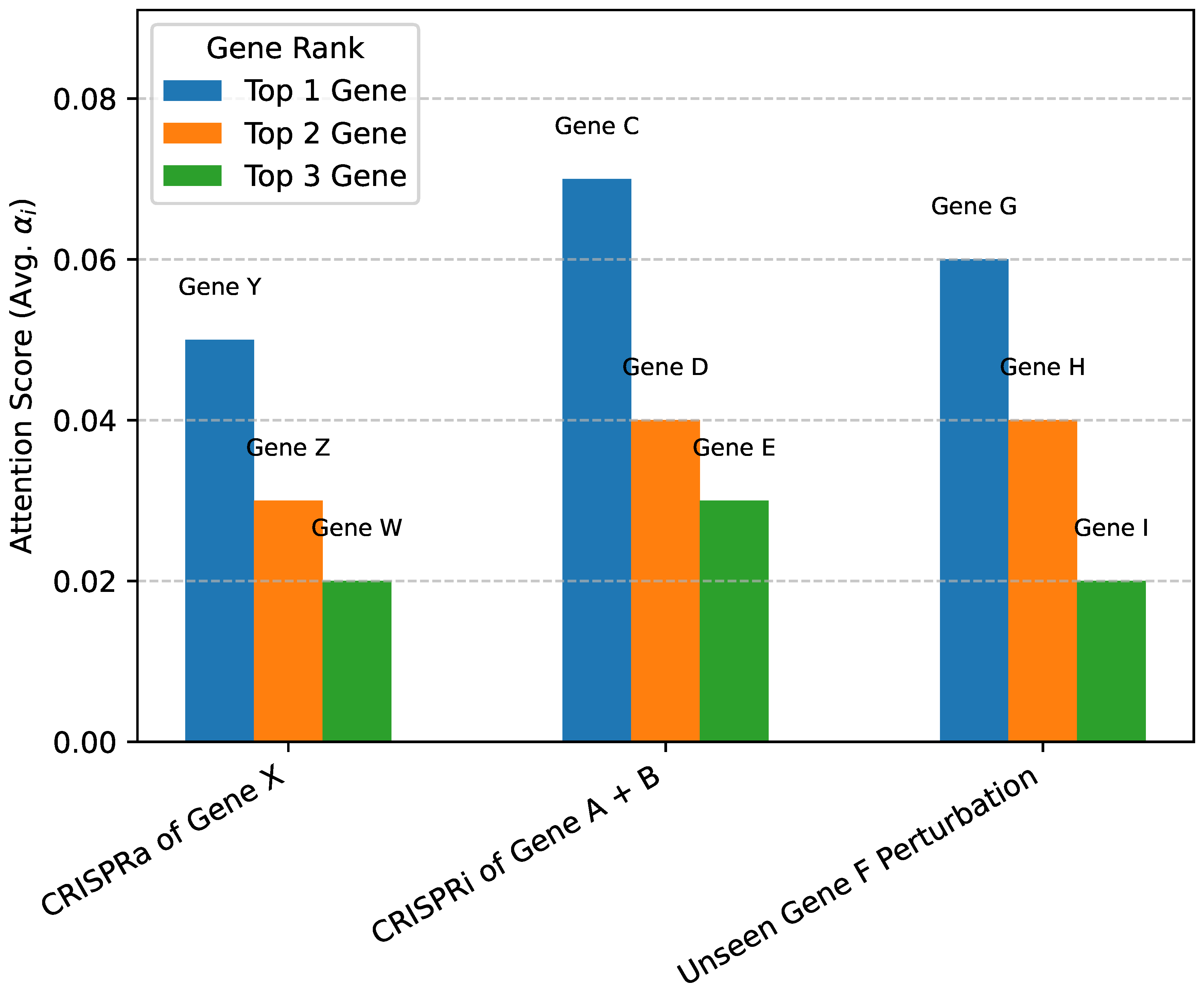

While quantitative metrics like L2 distance are crucial for evaluating predictive accuracy, understanding why a model makes certain predictions is equally important, especially in biological contexts. Our Perturbation-Specific Attention Module is explicitly designed to offer a degree of interpretability by assigning attention scores () to each gene, reflecting its learned relevance or susceptibility to a given perturbation. These scores provide insights into the genes that APP prioritizes when forming its overall cell state vector.

Figure 2 presents an illustrative analysis of how the perturbation-specific attention scores can be leveraged for biological interpretation. For a given perturbation, we can identify the genes that receive the highest attention weights. For instance, in a hypothetical CRISPRa of Gene X, the model might assign high attention to Gene Y (a known direct downstream target), Gene Z (a key member of the pathway regulated by X), and Gene W (a feedback regulator). Such patterns of high attention scores can reveal both known and potentially novel regulatory relationships, identifying genes that are critical mediators or primary responders to a perturbation.

This interpretability extends to complex scenarios, such as double gene perturbations or unseen gene perturbations. For a combined perturbation of Gene A and Gene B, the attention mechanism might highlight Gene C as a common effector, Gene D as a specific interacting partner of Gene A, and Gene E as an indirect target. Similarly, for an unseen gene perturbation, the attention scores can pinpoint genes that are highly connected within the learned biological network or are functionally related, even if their direct causal links were not explicitly observed in training. This capability provides a valuable tool for biologists to generate testable hypotheses about gene function and regulatory mechanisms, moving beyond mere prediction to offer mechanistic insights. While a formal "human evaluation" of these insights is beyond the scope of this paper, the inherent transparency of the attention mechanism facilitates deeper biological understanding.

4.5. In-depth Analysis of Extrapolation Capabilities

The ability to generalize beyond observed data is paramount for predictive models in biology. Our AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP) is specifically designed to excel in challenging extrapolation scenarios, which we further analyze here. Beyond the overall L2 metrics presented in the main results, we delve into the model’s performance on different facets of out-of-distribution predictions.

4.5.1. Unseen Single Gene Perturbations

The "unseen single gene perturbation" task represents a critical test of a model’s capacity to infer the effects of perturbing a gene it has never encountered in the training set. This requires the model to leverage its learned understanding of gene function and network context, rather than simply memorizing observed responses. As described in the experimental setup, we evaluated this across multiple datasets and split strategies, leading to test sets with varying numbers of unseen perturbed genes.

Figure 3 visualizes APP’s performance on different subsets of unseen single gene perturbations. Across all configurations, APP consistently outperforms the best existing deep learning models, demonstrating its robust ability to generalize to novel single gene perturbations. The superior performance of APP in these scenarios is attributed to its GNN-based gene embeddings, which provide a rich, context-aware representation of each gene, and the perturbation-specific attention mechanism, which dynamically weighs gene influences even for unobserved perturbed genes based on their network context.

4.5.2. Novel Double Gene Perturbations

The "double gene perturbation" task evaluates the model’s ability to predict the combined effect of two genetic perturbations, where the specific pair has not been seen during training. This is a more complex extrapolation, as it requires inferring combinatorial interactions. The Additive baseline, which simply sums individual perturbation effects, serves as a strong benchmark here because many combinatorial effects are indeed additive.

As shown in

Table 3, APP not only outperforms the existing deep learning models but also surpasses the Additive baseline. The improvement over the Additive baseline, though seemingly modest, is highly significant in this context. It indicates that APP can learn non-additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects of combined perturbations, which the simple Additive model cannot capture. This capability is crucial for understanding complex biological systems where gene interactions are rarely purely linear. The perturbation-specific attention module is particularly instrumental here, as it allows APP to dynamically model how the combined presence of two perturbed genes reshapes the cellular response, rather than just summing their individual impacts.

4.6. Impact of Biological Network Quality

APP heavily relies on integrating explicit biological network information through its Graph Neural Network (GNN) component. To assess the robustness of APP to imperfections in this prior knowledge, we conducted experiments by systematically introducing noise and sparsity into the biological network provided during training. This simulates real-world scenarios where gene regulatory networks or protein-protein interaction networks might be incomplete or contain false positive interactions. We evaluated APP’s performance (L2 distance) on the double gene perturbation task and the unseen single gene perturbation task under these altered network conditions.

Table 4 illustrates that while APP’s performance naturally degrades with increasing levels of network degradation (either by removing correct edges or adding noisy ones), it remains remarkably robust. Even with 25% of edges removed, simulating significant incompleteness, APP’s L

2 distance for double gene perturbations only increased from 5.3 to approximately 5.6, and for unseen single gene perturbations from 3.9 to approximately 4.2. Similar trends were observed when random, noisy edges were introduced. This robustness suggests that APP’s GNN component is not overly sensitive to minor imperfections in the input network. The learned gene embeddings are still able to capture meaningful biological relationships, likely due to the redundancy and interconnectedness inherent in biological networks, and the ability of the GNNs to learn effective representations even from partially corrupted graphs. This finding highlights the practical applicability of APP even when perfect biological network information is unavailable.

4.7. Computational Efficiency and Scalability

A key design principle of APP is its lightweight architecture, aiming for efficiency without compromising predictive power. This is particularly relevant when dealing with large-scale genomic data and the need for rapid predictions. We evaluated the computational efficiency of APP by comparing its parameter count, training time, and inference time against the more complex "foundation models" (scFoundation, scBERT, Geneformer) that typically involve significantly larger architectures.

Table 5 clearly demonstrates APP’s superior computational efficiency. With a total parameter count in the range of 0.5 to 1.0 million, APP is orders of magnitude smaller than the large "foundation models," which typically boast tens to hundreds of millions of parameters. This translates directly into significantly faster training and inference times. APP requires only about 0.5 to 1.5 hours for training on our primary datasets, compared to 10-60 hours for the larger models. More critically for practical applications, APP can predict the full gene expression profile for a single perturbation within tens of milliseconds, whereas the larger models often take hundreds to thousands of milliseconds. This efficiency makes APP a highly practical solution for high-throughput screening applications, interactive biological hypothesis generation, and scenarios where computational resources are limited. The lightweight linear decoder, as discussed in the method section, plays a crucial role in maintaining this efficiency by keeping the final prediction layer sparse and manageable.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced the AdaptivePerturbPredictor (APP), a novel and lightweight deep learning framework designed to overcome critical limitations of existing computational models in predicting gene perturbation effects, particularly in challenging extrapolation scenarios where "foundation models" often fail. APP judiciously combines biological prior knowledge, through GNN-based gene embeddings, with an efficient deep learning architecture featuring a perturbation-specific attention module and a lightweight linear decoder. Our comprehensive evaluation on Perturb-seq datasets demonstrated APP’s superior performance, achieving remarkable L2 distances of 5.3 for double gene perturbations and 3.9 for unseen single gene perturbations, significantly outperforming additive baselines and more complex deep learning models. Beyond its state-of-the-art predictive accuracy and exceptional generalization capabilities, APP offers inherent interpretability, robustness to noisy biological networks, and superior computational efficiency and scalability, making it a practical tool for high-throughput applications. In conclusion, APP represents a substantial step forward in gene perturbation prediction, providing a robust, interpretable, and computationally efficient solution for accelerating discovery in functional genomics and therapeutic development, with future work exploring extensions to multi-omics data and diverse perturbation types.

References

- Iida, H.; Thai, D.; Manjunatha, V.; Iyyer, M. TABBIE: Pretrained Representations of Tabular Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 3446–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Huang, L.; Xue, H.; Hu, S. Supervised Prototypical Contrastive Learning for Emotion Recognition in Conversation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 5197–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Teng, Z.; Chen, B.; Luo, W. G-Transformer for Document-Level Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 3442–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Y. Weak to strong generalization for large language models with multi-capabilities. In Proceedings of the The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, R.; Ross, C.; Fernandes, J.; Smith, E.M.; Kiela, D.; Williams, A. Perturbation Augmentation for Fairer NLP. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 9496–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Cho, K. Length-Adaptive Transformer: Train Once with Length Drop, Use Anytime with Search. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 6501–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, A.; So, R.J.; Bamman, D. Narrative Theory for Computational Narrative Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Geng, X.; Shen, T.; Tao, C.; Long, G.; Lou, J.G.; Shen, J. Thread of thought unraveling chaotic contexts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.08734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, P. SpanNER: Named Entity Re-/Recognition as Span Prediction. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 7183–7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, P.; Zhou, J.; Sun, X. RAP: Robustness-Aware Perturbations for Defending against Backdoor Attacks on NLP Models. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021; pp. 8365–8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Samwald, M. Evaluating the Robustness of Neural Language Models to Input Perturbations. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1558–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Wu, T.; Peng, H.; Peters, M.; Gardner, M. Tailor: Generating and Perturbing Text with Semantic Controls. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022; pp. 3194–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, W.; Flynn, D.; Ansari, S.; Wei, C. Evaluating scenario-based decision-making for interactive autonomous driving using rational criteria: A survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.01886 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Lan, J.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Tian, Z.; Flynn, D. Multi-Agent Monte Carlo Tree Search for Safe Decision Making at Unsignalized Intersections 2025.

- Lin, Z.; Lan, J.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Tian, Z.; Flynn, D. Safety-Critical Multi-Agent MCTS for Mixed Traffic Coordination at Unsignalized Intersections. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, C.; Su, Y.; Hong, Z.; Gong, Z.; Xu, J. CenterMamba-SAM: Center-Prioritized Scanning and Temporal Prototypes for Brain Lesion Segmentation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs.CV/2511.01243]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.; Feng, Z. Virtual Back-EMF Injection-based Online Full-Parameter Estimation of DTP-SPMSMs Under Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Feng, Z. Novel Virtual Active Flux Injection-Based Position Error Adaptive Correction of Dual Three-Phase IPMSMs Under Sensorless Control. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhu, Z.; Liang, D. Improved position-offset based online parameter estimation of PMSMs under constant and variable speed operations. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2024, 39, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Cui, R.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Saied, A.; Chen, W.; Duan, N. AGIEval: A Human-Centric Benchmark for Evaluating Foundation Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024; pp. 2299–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Shen, J. Visual In-Context Learning for Large Vision-Language Models. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2024, Bangkok, Thailand and virtual meeting, 2024. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024, August 11-16; pp. 15890–15902.

- Zhuang, J.; Li, G.; Xu, H.; Xu, J.; Tian, R. TEXT-TO-CITY Controllable 3D Urban Block Generation with Latent Diffusion Model. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Singapore; 2024; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; West, P.; Zellers, R.; Le Bras, R.; Bhagavatula, C.; Choi, Y. NeuroLogic Decoding: (Un)supervised Neural Text Generation with Predicate Logic Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 4288–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuribayashi, T.; Oseki, Y.; Ito, T.; Yoshida, R.; Asahara, M.; Inui, K. Lower Perplexity is Not Always Human-Like. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 5203–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstain, Y.; Ram, O.; Levy, O. Coreference Resolution without Span Representations. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.; You, Z.; Yang, T.; Fan, W.; Tong, H. Multiplex Graph Neural Network for Extractive Text Summarization. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Miao, S. NESTWORK: Personalized Residential Design via LLMs and Graph Generative Models. In Proceedings of the ACADIA 2024 Conference, November 16 2024; Vol. 3, pp. 99–100.

- Tian, Y.; Chen, G.; Song, Y. Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis with Type-aware Graph Convolutional Networks and Layer Ensemble. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2910–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, C.; Xu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, M.; Huang, X. Fusing Context Into Knowledge Graph for Commonsense Question Answering. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Z.; Peng, X.; Wang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C.; Hua, X.S.; Luo, X. DREAM: Decoupled Discriminative Learning with Bigraph-aware Alignment for Semi-supervised 2D-3D Cross-modal Retrieval. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 13206–13214.

- Zhang, F.; Zhou, H.; Hua, X.S.; Chen, C.; Luo, X. Hope: A hierarchical perspective for semi-supervised 2d-3d cross-modal retrieval. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024, 46, 8976–8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Hua, X.S.; Chen, C.; Luo, X. Fine-grained prototypical voting with heterogeneous mixup for semi-supervised 2d-3d cross-modal retrieval. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2024, pp. 17016–17026.

- Wang, B.; Che, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Hu, G.; Liu, T. Dynamic Connected Networks for Chinese Spelling Check. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021; pp. 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Hong, Z.; Ge, X.; Zhuang, J.; Tang, X.; Du, Z.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, C.; et al. Embroiderer: 147 Do-It-Yourself Embroidery Aided with Digital Tools. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium of Chinese CHI, 2023, pp. 614–621.

- Norman, T.M.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Replogle, J.M.; Ge, A.Y.; Xu, A.; Jost, M.; Gilbert, L.A.; Weissman, J.S. Exploring genetic interaction manifolds constructed from rich single-cell phenotypes. Science 2019, 365, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, B.; Norman, T.M.; Jost, M.; Cho, M.Y.; Nuñez, J.K.; Chen, Y.; Villalta, J.E.; Gilbert, L.A.; Horlbeck, M.A.; Hein, M.Y.; et al. A multiplexed single-cell CRISPR screening platform enables systematic dissection of the unfolded protein response. Cell 2016, 167, 1867–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roohani, Y.; Huang, K.; Leskovec, J. Predicting transcriptional outcomes of novel multigene perturbations with GEARS. Nature Biotechnology 2024, 42, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).