Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell Culturing for Cell Lines

2.2. Extraction of Genomic DNAs, RNAs, RNCs and Proteins from Cell Lines

2.3. Genomic DNAs Sequencing

2.4. RNAs and RNCs Sequencing

2.5. Proteomics Analyzed by LC-MS/MS

2.6. DNA Sequencing Bioinformatics

2.7. RNA and RNC Sequencing Bioinformatics

2.8. Proteomic Bioinformatics

2.9. Verification of Transcript SNVs Using Sanger Sequencing

2.10. Analysis of SNVs Characteristic

2.11. Model Construction for Transcription-Dependent SNVs Calling

2.12. General Data Analysis

3. Results

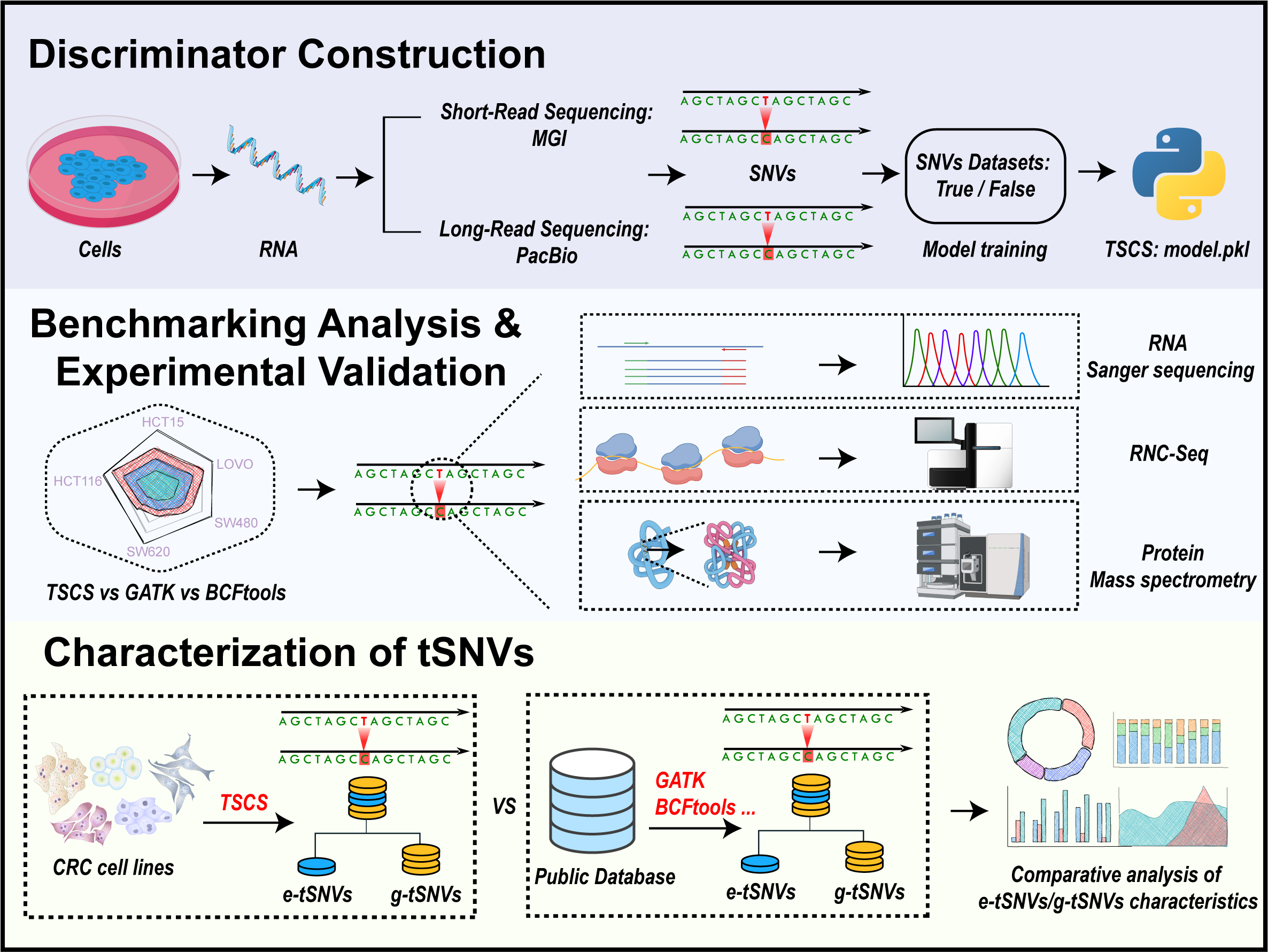

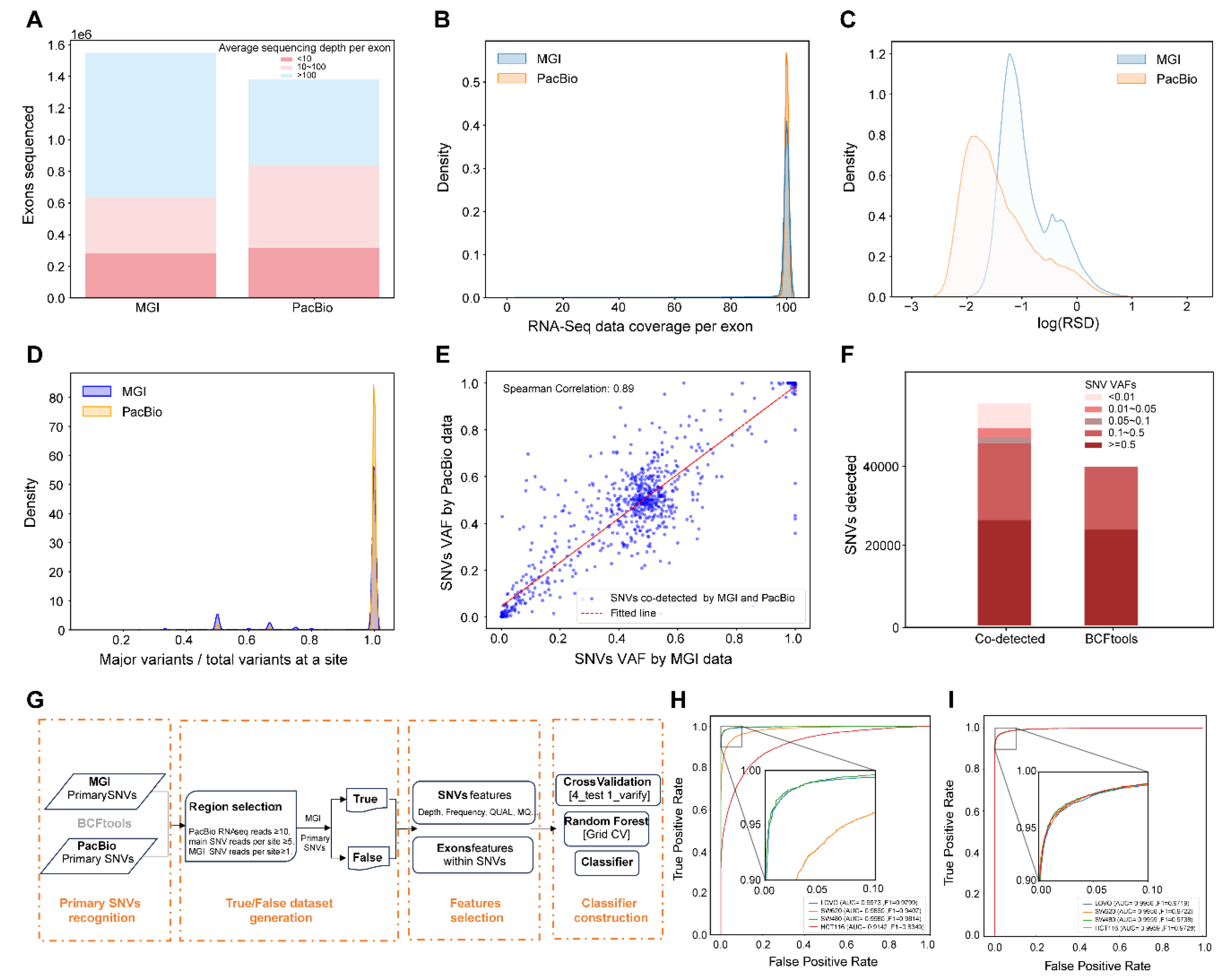

3.1. Discriminator Establishment Towards Transcript SNVs Based on Sequencing Data from MGI and PacBio

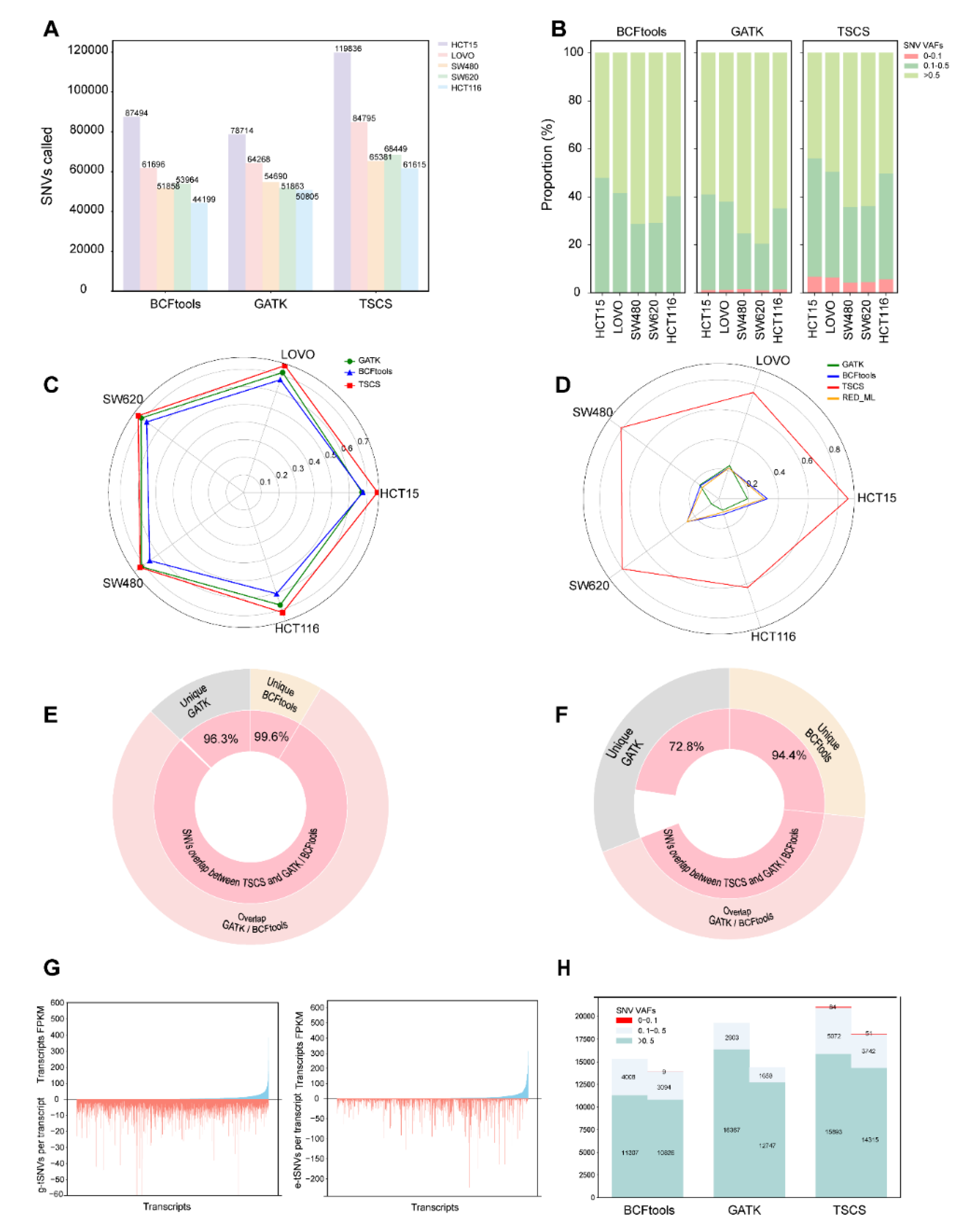

3.2. Performance Comparison of Transcript SNVs Callings Among Different Software

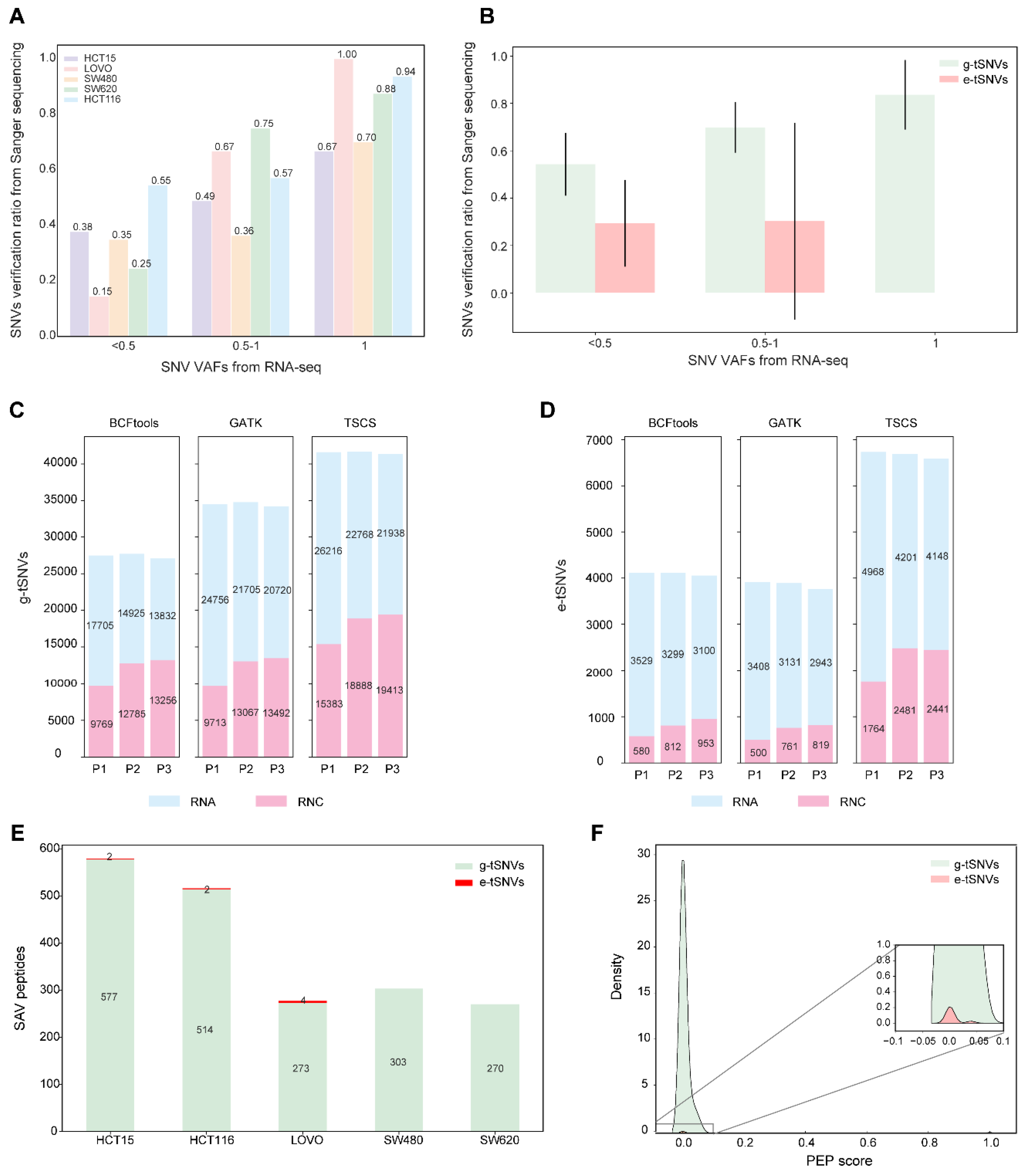

3.3. Verification of Transcript SNVs and Their Translated Products in Cell Lines

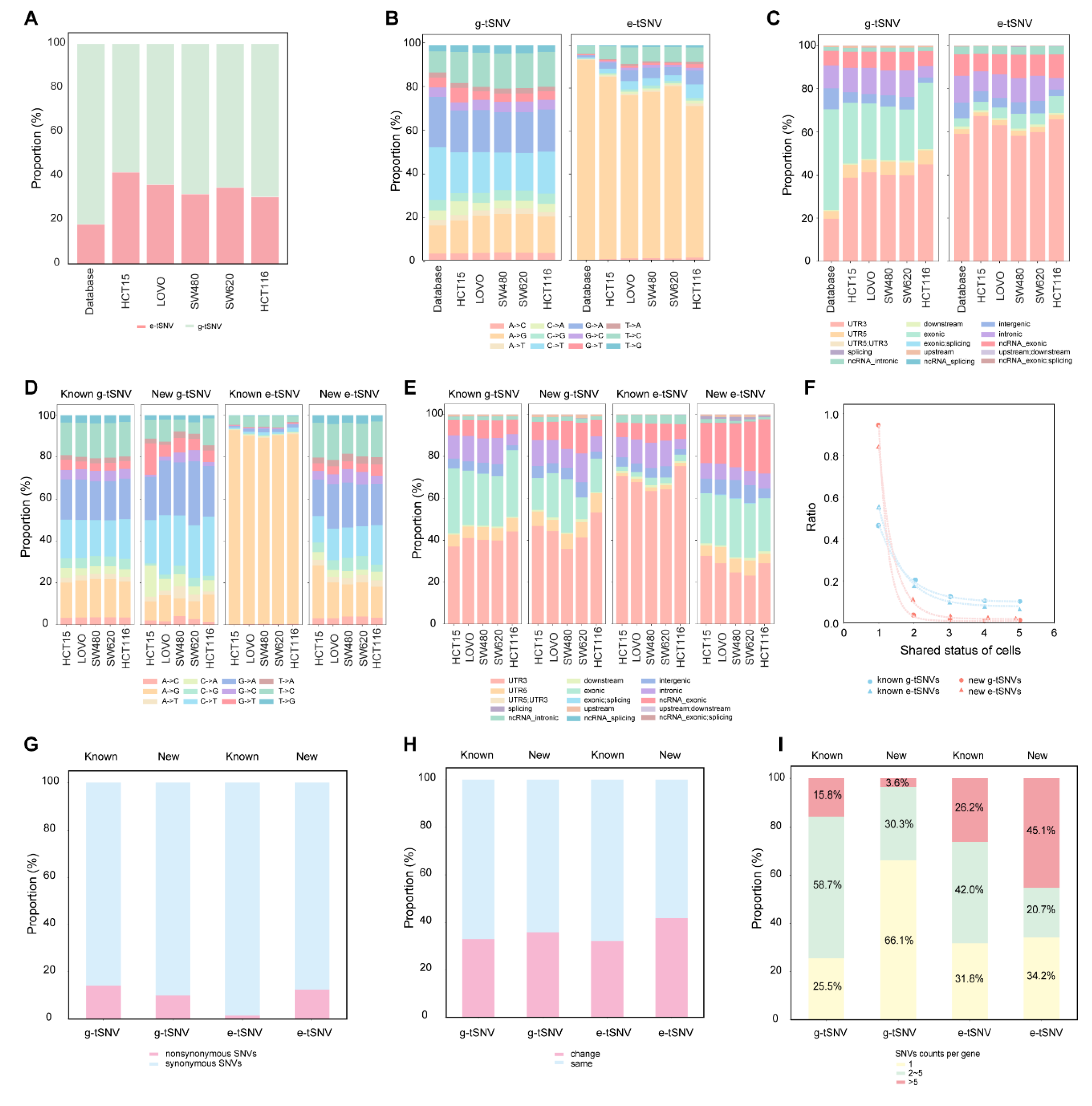

3.4. Characterization of e-tSNVs in Cancer Cell Lines

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.H.; Tokheim, C.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Sengupta, S.; Bertrand, D.; Weerasinghe, A.; Colaprico, A.; Wendl, M.C.; Kim, J.; Reardon, B.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 2018, 173, 371–385 e318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Hollstein, M.; Hainaut, P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010, 2, a001008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.D.; Parsons, D.W.; Jones, S.; Lin, J.; Sjoblom, T.; Leary, R.J.; Shen, D.; Boca, S.M.; Barber, T.; Ptak, J.; et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science 2007, 318, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincorena, I.; Raine, K.M.; Gerstung, M.; Dawson, K.J.; Haase, K.; Van Loo, P.; Davies, H.; Stratton, M.R.; Campbell, P.J. Universal Patterns of Selection in Cancer and Somatic Tissues. Cell 2017, 171, 1029–1041 e1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Kim, J.; Haradhvala, N.J.; Huang, M.N.; Tian Ng, A.W.; Wu, Y.; Boot, A.; Covington, K.R.; Gordenin, D.A.; Bergstrom, E.N.; et al. Author Correction: The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 2023, 614, E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, I.X.; Li, Y.; Bruzel, A.; Richards, A.L.; Toung, J.M.; Cheung, V.G. Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. Science 2011, 333, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Hawke, D.H.; Yu, S.; Han, L.; Zhou, Z.; Mojumdar, K.; Jeong, K.J.; Labrie, M.; et al. A-to-I RNA Editing Contributes to Proteomic Diversity in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 817–828 e817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Aroya, S.; Levanon, E.Y. A-to-I RNA Editing: An Overlooked Source of Cancer Mutations. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 789–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayir, A. RNA modifications as emerging therapeutic targets. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2022, 13, e1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, E.; Regina, T.M.; Brennicke, A.; Quagliariello, C. REDIdb: the RNA editing database. Nucleic Acids Res 2007, 35, D173–D177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, A.; Baranov, P.V. DARNED: a DAtabase of RNa EDiting in humans. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1772–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, G.; Li, J.B. RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, D109–D113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picardi, E.; D’Erchia, A.M.; Lo Giudice, C.; Pesole, G. REDIportal: a comprehensive database of A-to-I RNA editing events in humans. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45, D750–D757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Yu, H.; Samuels, D.C.; Yue, W.; Ness, S.; Zhao, Y.Y. Single-nucleotide variants in human RNA: RNA editing and beyond. Brief Funct Genomics 2019, 18, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, H.T.; Schaffer, A.A.; Kaniewska, P.; Alon, S.; Eisenberg, E.; Rosenthal, J.; Levanon, E.Y.; Levy, O. A-to-I RNA Editing in the Earliest-Diverging Eumetazoan Phyla. Mol Biol Evol 2017, 34, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikura, K. A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016, 17, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navaratnam, N.; Sarwar, R. An overview of cytidine deaminases. Int J Hematol 2006, 83, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazak, L.; Haviv, A.; Barak, M.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Deng, P.; Zhang, R.; Isaacs, F.J.; Rechavi, G.; Li, J.B.; Eisenberg, E.; et al. A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes. Genome Res 2014, 24, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.H.; Li, Q.; Shanmugam, R.; Piskol, R.; Kohler, J.; Young, A.N.; Liu, K.I.; Zhang, R.; Ramaswami, G.; Ariyoshi, K.; et al. Dynamic landscape and regulation of RNA editing in mammals. Nature 2017, 550, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskol, R.; Ramaswami, G.; Li, J.B. Reliable identification of genomic variants from RNA-seq data. Am J Hum Genet 2013, 93, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castel, S.E.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Mohammadi, P.; Banks, E.; Lappalainen, T. Tools and best practices for data processing in allelic expression analysis. Genome Biol 2015, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duitama, J.; Srivastava, P.K.; Mandoiu, II. Towards accurate detection and genotyping of expressed variants from whole transcriptome sequencing data. BMC Genomics 2012, 13 Suppl 2, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Baheti, S.; Shameer, K.; Thompson, K.J.; Wills, Q.; Niu, N.; Holcomb, I.N.; Boutet, S.C.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Kachergus, J.M.; et al. The eSNV-detect: a computational system to identify expressed single nucleotide variants from transcriptome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koboldt, D.C.; Zhang, Q.; Larson, D.E.; Shen, D.; McLellan, M.D.; Lin, L.; Miller, C.A.; Mardis, E.R.; Ding, L.; Wilson, R.K. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 2012, 22, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2013, 43, 11–11 10 11-11 10 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.; Weirick, T.; Dimmeler, S.; Uchida, S. RNAEditor: easy detection of RNA editing events and the introduction of editing islands. Brief Bioinform 2017, 18, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Y.; Yan, S.; Xing, Q.; Tian, W. SPRINT: an SNP-free toolkit for identifying RNA editing sites. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3538–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, E.; Pesole, G. REDItools: high-throughput RNA editing detection made easy. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1813–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechotta, M.; Wyler, E.; Ohler, U.; Landthaler, M.; Dieterich, C. JACUSA: site-specific identification of RNA editing events from replicate sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 2017, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Liu, D.; Li, Q.; Lei, M.; Xu, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Ren, S.; Li, W.; Xia, M.; et al. RED-ML: a novel, effective RNA editing detection method based on machine learning. Gigascience 2017, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Seo, J.H.; Min, S.; Park, J.; Cho, S.R.; Kim, H.H. Deep learning models to predict the editing efficiencies and outcomes of diverse base editors. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhao, C.; Ren, C.; An, G.; Mei, C.; Bo, X.; Shu, W. Accurate identification of RNA editing sites from primitive sequence with deep neural networks. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Sharma, P.C. Next generation sequencing-based emerging trends in molecular biology of gastric cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2018, 8, 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom, P.G.; Steijger, T.; Sipos, B.; Grant, G.R.; Kahles, A.; Ratsch, G.; Goldman, N.; Hubbard, T.J.; Harrow, J.; Guigo, R.; et al. Systematic evaluation of spliced alignment programs for RNA-seq data. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steijger, T.; Abril, J.F.; Engstrom, P.G.; Kokocinski, F.; Consortium, R.; Hubbard, T.J.; Guigo, R.; Harrow, J.; Bertone, P. Assessment of transcript reconstruction methods for RNA-seq. Nat Methods 2013, 10, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, A.; Madrigal, P.; Tarazona, S.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Cervera, A.; McPherson, A.; Szczesniak, M.W.; Gaffney, D.J.; Elo, L.L.; Zhang, X.; et al. A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol 2016, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharon, D.; Tilgner, H.; Grubert, F.; Snyder, M. A single-molecule long-read survey of the human transcriptome. Nat Biotechnol 2013, 31, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio Sequencing and Its Applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cui, Y.; Jin, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, G.; Yin, X.; He, Q.Y.; Zhang, G. Translating mRNAs strongly correlate to proteins in a multivariate manner and their translation ratios are phenotype specific. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41, 4743–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, P.; Bansal, V. Longshot enables accurate variant calling in diploid genomes from single-molecule long read sequencing. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Han, Y.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Ning, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Jin, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; et al. Long-read sequencing reveals the landscape of aberrant alternative splicing and novel therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Genome Med 2023, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Ghaemmaghami, S.; Newman, J.R.; Weissman, J.S. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 2009, 324, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calviello, L.; Mukherjee, N.; Wyler, E.; Zauber, H.; Hirsekorn, A.; Selbach, M.; Landthaler, M.; Obermayer, B.; Ohler, U. Detecting actively translated open reading frames in ribosome profiling data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman, M.; Russell, P.; Ingolia, N.T.; Weissman, J.S.; Lander, E.S. Ribosome profiling provides evidence that large noncoding RNAs do not encode proteins. Cell 2013, 154, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, K.; Mertins, P.; Zhang, B.; Hornbeck, P.; Raju, R.; Ahmad, R.; Szucs, M.; Mundt, F.; Forestier, D.; Jane-Valbuena, J.; et al. A Curated Resource for Phosphosite-specific Signature Analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2019, 18, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, Z.; Chambers, M.C.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Shaddox, K.F.; Kim, S.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2014, 513, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Schlegl, J.; Hahne, H.; Gholami, A.M.; Lieberenz, M.; Savitski, M.M.; Ziegler, E.; Butzmann, L.; Gessulat, S.; Marx, H.; et al. Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the human proteome. Nature 2014, 509, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaudel, M.; Verheggen, K.; Csordas, A.; Raeder, H.; Berven, F.S.; Martens, L.; Vizcaino, J.A.; Barsnes, H. Exploring the potential of public proteomics data. Proteomics 2016, 16, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, N.; He, Y.; Pong, R.; Lin, D.; Lu, L.; Law, M. Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012, 2012, 251364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantscheff, M.; Schirle, M.; Sweetman, G.; Rick, J.; Kuster, B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: a critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem 2007, 389, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitteringham, N.R.; Jenkins, R.E.; Lane, C.S.; Elliott, V.L.; Park, B.K. Multiple reaction monitoring for quantitative biomarker analysis in proteomics and metabolomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009, 877, 1229–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kall, L.; Storey, J.D.; MacCoss, M.J.; Noble, W.S. Posterior error probabilities and false discovery rates: two sides of the same coin. J Proteome Res 2008, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherry, S.T.; Ward, M.H.; Kholodov, M.; Baker, J.; Phan, L.; Smigielski, E.M.; Sirotkin, K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, J.G.; Bamford, S.; Jubb, H.C.; Sondka, Z.; Beare, D.M.; Bindal, N.; Boutselakis, H.; Cole, C.G.; Creatore, C.; Dawson, E.; et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D941–D947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.S.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, S.; Hong, D.; Park, H.; Shin, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, W.C.; Kim, S.; Yu, S.B.; et al. Extensive genomic and transcriptional diversity identified through massively parallel DNA and RNA sequencing of eighteen Korean individuals. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Li, G.; Greer, C.; Peng, G.; Xiao, X. Accurate identification of A-to-I RNA editing in human by transcriptome sequencing. Genome Res 2012, 22, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.R. The classification of amino acid conservation. J Theor Biol 1986, 119, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Henikoff, S.; Ng, P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc 2009, 4, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, A.; Beal, K.; Keenan, S.; McLaren, W.; Pignatelli, M.; Ritchie, G.R.; Ruffier, M.; Taylor, K.; Vullo, A.; Flicek, P. The Ensembl REST API: Ensembl Data for Any Language. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, L.J.; O’Bleness, M.S.; Davis, J.M.; Dickens, C.M.; Anderson, N.; Keeney, J.G.; Jackson, J.; Sikela, M.; Raznahan, A.; Giedd, J.; et al. DUF1220-domain copy number implicated in human brain-size pathology and evolution. Am J Hum Genet 2012, 91, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, C.P.; Maggi, L.B.; Jr Weber, J.D. The Role of RNA Editing in Cancer Development and Metabolic Disorders. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Yaacov, N.; Bazak, L.; Buchumenski, I.; Porath, H.T.; Danan-Gotthold, M.; Knisbacher, B.A.; Eisenberg, E.; Levanon, E.Y. Elevated RNA Editing Activity Is a Major Contributor to Transcriptomic Diversity in Tumors. Cell Rep 2015, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, C.H.; Chan, T.H.; Chow, R.K.; Song, Y.; Liu, M.; Yuan, Y.F.; Fu, L.; Kong, K.L.; et al. Recoding RNA editing of AZIN1 predisposes to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med 2013, 19, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, F.; Rossetti, C.; Tomaselli, S.; Cifaldi, L.; Lezzerini, M.; Pezzullo, M.; Boldrini, R.; Massimi, L.; Di Rocco, C.M.; Locatelli, F.; et al. ADAR2-editing activity inhibits glioblastoma growth through the modulation of the CDC14B/Skp2/p21/p27 axis. Oncogene 2013, 32, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, J.M.; Emeson, R.B. Functions and mechanisms of RNA editing. Annu Rev Genet 2000, 34, 499–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.M.; Wallis, S.C.; Pease, R.J.; Edwards, Y.H.; Knott, T.J.; Scott, J. A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine. Cell 1987, 50, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Quadros, E.V.; Regec, A.; Zittoun, J.; Rothenberg, S.P. Congenital transcobalamin II deficiency due to errors in RNA editing. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2002, 28, 134–142, discussion 143-135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberberg, G.; Lundin, D.; Navon, R.; Ohman, M. Deregulation of the A-to-I RNA editing mechanism in psychiatric disorders. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).