1. Introduction

Worldwide, health systems face an accelerating shortage of nursing staff. Driven by demographic change, population aging, and the growing prevalence of chronic diseases, the demand for professional and long-term care continues to increase, while the available workforce is declining. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 17% of the global nursing workforce is aged 55 years or older and therefore expected to retire within the next decade [

1]. To merely maintain the current level of care provision, 4.7 million new nurses will need to be trained and employed by 2030—significantly more will be required to close existing workforce gaps and meet the rising demands for care [

1]. This imbalance poses a threat to the continuity, quality, and safety of care delivery for vulnerable populations, particularly in nursing homes.

Digital transformation is increasingly viewed as a crucial strategy to meet these challenges. Digital tools can support nurses, improve interdisciplinary communication, and enhance access to remote medical expertise, thereby contributing to better patient outcomes and reducing workload burdens. The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrated the potential of telecare and teleconsultation to maintain care continuity, reduce avoidable transfers, and provide remote expertise under constrained conditions. Digital solutions have the potential not only to ease the workload of care professionals but also to maintain and enhance the quality of care [

2,

3]. Digital nursing technologies (DNT) have been identified as a promising solution to address staff shortages [

4].

While digital tools are well established in hospitals and medical practices, long-term care facilities have often been neglected in innovation processes. Systematic reviews consistently highlight barriers, including insufficient technical infrastructure, lack of interoperability, unclear reimbursement pathways, and uncertainties related to regulation and data protection [

2,

5,

6]. Beyond structural challenges, successful implementation requires more than technology. Little is known about how such systems can be effectively implemented and integrated into everyday nursing home practice. Existing studies often focus on technological feasibility or clinical outcomes, whereas evidence on participatory, context-sensitive implementation approaches remains scarce. Literature emphasizes that nursing staff participation in design, strong leadership, organizational support, and context-sensitive adaptation are key factors in the success of digital health adoption [

7,

8,

9]. Understanding how digital interventions are adopted, adapted, and sustained in real-world, long-term care settings is essential for informing future scale-up efforts.

The CareConnect project was developed to address these issues: Two nursing homes in Germany established a telecare system that staff could use for nursing and medical questions regarding their residents, providing timely remote expertise and demonstrating a possible way of implementing digital innovations in long-term care facilities. The scope of application and corresponding use cases were jointly defined in accordance with the study design. The study’s objective was to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and early adoption of a telecare system in nursing homes, enabling sector-spanning interprofessional collaboration and identifying key facilitators, barriers, and perceived effects on care delivery, communication, and digital competencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A participatory implementation design was applied over 15 months (June 2024–August 2025), involving a university hospital, two nursing homes (NH A and NH B), and four medical practices. The NHs were a convenience sample and recruited via direct contact and represented two contrasting long-term care facilities: one smaller facility with limited baseline digital infrastructure, and one larger facility with existing Wi-Fi and specialized wards for ventilated residents.

The study followed the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (

StaRI), distinguishing between the telecare intervention and the implementation strategy [

10]. The telecare intervention consisted of scheduled video consultations and interdisciplinary case discussions supported by diagnostic devices. Further specifications of the intervention were part of the iterative co-design process.

The implementation strategy comprised participatory co-design, training, iterative testing, and structured feedback loops.

2.2. Implementation Strategy

The implementation strategy was conceptually informed by key domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), with particular emphasis on stakeholder engagement

, iterative refinement

, and capacity building [

11]. The implementation process consisted of three iterative phases, each linked to an anticipated mechanism of change and expected to support the integration of telecare into routine practice:

- 1.

Needs assessment and co-design: At the beginning, three interdisciplinary workshops were held with nursing staff, physicians, and IT specialists to identify care needs, communication barriers, and expectations regarding telecare and its use cases. The mechanism of change employed was stakeholder engagement, expected to increase acceptability and workflow fit. Based on the workshop findings, the project team developed an initial telecare concept tailored to the organizational routines and technical capabilities of both NHs. The expected outcome was a jointly developed, contextually adapted telecare concept that defined contact types, scheduling structures, and equipment requirements.

- 2.

Training and technical onboarding: Following the co-design phase, all participating nurses received hands-on training on the use of the telecare system (including the certified video consultation software and additional diagnostic devices like otoscopes, dermatoscopes, and ECGs). The training sessions functioned as multiplier trainings, enabling internal dissemination of skills. Test runs were incorporated to ensure technical readiness and familiarize users with the workflow. The mechanism of change was capacity building, expected to increase digital competence and reduce uncertainty.

- 3.

Implementation and continuous feedback: During the 11-month implementation phase, teleconsultations and interdisciplinary case discussions were conducted in routine care. The process was accompanied by three structured feedback rounds, in which nursing staff provided input on usability, technical challenges, perceived benefits, and workflow obstacles. Through this iterative refinement, the implementation strategy was adapted to the feedback, where applicable, aiming to achieve the expected outcome of progressively integrating telecare into daily routines.

Each component targeted a specific mechanism of change, which was assessed in the process evaluation.

2.3. Data Sources

Data were derived from four different sources:

Telecare documentation: The standardized documentation in project-specific spreadsheets completed by physicians after each telecare contact included date of contact, reason for contact, diagnostic instruments used, outcome/treatment decision, and need for re-contact. Furthermore, physicians’ evaluation of the digital suitability of the contact and the technical reliability was measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

Structured online nurse survey: This anonymous survey was offered to nurses after every telecare contact from May to August 2025. This survey captured the total frequencies of contacted professionals and the reason for the contact. Nurses’ assessment of the usefulness of the contact, the extent to which the problem could be resolved, and the technical reliability was measured using a 5-point Likert scale.

Researcher observations: Field notes were taken during workshops, training sessions, test runs, and feedback meetings.

Semi-structured participant feedback was obtained during regular round-table discussions and short debriefings during the implementation phase.

These complementary data sources provided the empirical basis for analyzing usage patterns, progress in implementation, and user experiences during the implementation phase.

2.4. Process Evaluation

The process evaluation examined whether the implementation strategy operated through the anticipated mechanisms of change (engagement, capacity building, workflow integration, iterative refinement), whether these mechanisms were observable in practice, and how contextual factors shaped adoption (technical infrastructure, staffing, organizational routines, changes in scheduling, workflows, device handling). Process outcomes were assessed in terms of staff engagement, technical readiness, competence development, and the degree to which telecare became integrated into daily routines. The evaluation also documented the barriers and facilitators that emerged during implementation and was transferred to a telecare implementation model.

2.5. Analytical Framework

Quantitative Analysis: Structured variables such as the number and characteristics of telecare contacts, the reasons for consultation, the diagnostic tools used, and assessments of digital suitability were extracted from the project-specific spreadsheets and analyzed descriptively (absolute and relative frequencies, means, ranges where applicable) to characterize usage patterns and the perceived appropriateness of telecare. No inferential statistics were performed.

Qualitative Analysis: Data about the implementation strategy and process evaluation were examined using systematic document analysis. The data primarily consisted of operational and factual notes, with a study focused on descriptive coding rather than interpretive theme development. This analysis identified emerging challenges, technical issues, workflow adaptations, nurses’ perceptions, contextual factors influencing implementation, and observable barriers and facilitators.

Findings were combined to provide an understanding of the feasibility of implementation, user acceptance, and perceived value, as well as the mechanisms influencing adoption and the contextual determinants of telecare uptake.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained, and informed consent was obtained from all participants involved.

3. Results

Results are presented in the order of the sequential phases of the implementation process. Quantitative usage data are integrated with qualitative observations and participant feedback to illustrate adoption patterns, practical experiences, and contextual influences. The findings reflect both implementation outcomes (e.g., acceptability, feasibility, adoption, digital suitability) and process mechanisms (stakeholder engagement, capacity building, iterative refinement, workflow integration).

3.1. Needs Assessment and Co-Design

3.1.1. Contextual Characteristics of Participating Nursing Homes

The NH involved (A and B) had different areas of focus. NH A was a smaller facility caring for 56 people, with an emphasis on dementia care, located in the central part of a German city where the study took place. NH A was adequately covered by care due to the presence of a general practitioner located nearby. Additionally, other medical specialists, such as dermatologists and dentists, were available for nursing home visits, but at varying frequencies. NH A lacked pre-existing Wi-Fi infrastructure and accelerated Wi-Fi implementation, demonstrating a high intrinsic motivation to become part of the digitalization process and introduce telecare. NH B was considerably larger, caring for approximately 171 residents, located in the same city, but not centrally. It offered two special wards with intensive long-term care for people in a persistent vegetative state or the need for mechanical ventilation. This nursing home also had a very good coverage of care by several general practitioners and some specialists, like neurologists and an anesthesiologist, for the ventilated patients. NH B had a preexisting Wi-Fi infrastructure and a nursing documentation system known for its interoperability options. These contextual differences informed the co-design process and shaped expectations regarding the integration of telecare.

3.1.2. Workshop Findings

During the initial interdisciplinary kick-off workshop (n = 25), participants tested the preselected telecare equipment, discussed potential use cases, and reflected on care challenges. Despite broadly adequate general practitioner coverage, staff in both homes highlighted gaps in access to specialist care: “We have good connections with general practitioners, but we lack specialist contacts for our intensive care cases.” (NH B). Additionally, with existing opportunities for nursing home visits by specialist nurses, it was stated that the frequency of care was partially inadequate, mainly in cases of acute situations. Both nursing homes agreed on the need for infectious disease consultations: “When residents show signs of infection on a Friday or Wednesday, we are struggling to organize a timely medical assessment or receive medication.” (NH A, NH B agreed). Furthermore, the opportunity for spontaneous telecare contacts with other professionals was discussed. It was contrasted with the better predictability of scheduled meetings, and the participants weighed the two concepts against each other.

Institution-specific workshops (NH A: n = 6; NH B: n = 8) further specified local needs and barriers. Common barriers included the unreliable availability of specialists, perceived reluctance from some hospital physicians, variable staff confidence in handling the system, and concerns regarding Wi-Fi stability. These findings informed the first draft of the telecare concept shown in

Table 1.

The research team led contact with various hospital departments to fulfill the drafted telecare concept. The NHs themselves led contact with the general physicians of the NHs. Discussions with hospital departments indicated that not all specialties were willing to provide telecare due to concerns about clinical suitability. This led to a refinement of the concept, and the study partners agreed on scheduled (rather than spontaneous) sessions to ensure predictable workflows. The resulting final concept for the 11-month implementation phase is shown in

Table 2.

3.2. Training/Onboarding

After conceptualization, the necessary hardware and software of the telecare system were established in both NHs. The technical provider conducted five training sessions across the two sites, enabling selected staff to act as multipliers for internal training in accordance with the legal requirements of the Medical Devices Act. Additional internal sessions were held in both homes to teach practical procedures, including preparing wound images, uploading medication plans, and assembling diagnostic devices. Physicians also provided focused training on the safe use of otoscopes, wound cameras, and oral diagnostic tools. In total, 37 nurses completed the formal training (14 in NH A and 23 in NH B).

After the training, a testing phase was added to offer the possibility for involved nurses and other medical professionals to test the system and telecare workflows without patients. This phase revealed substantial technical issues, including non-functional interfaces with the nursing documentation system, failed image transfers, and calibration problems with diagnostic devices. After resolving those issues with the technical provider’s assistance, active usage of the telecare system commenced in study month five.

3.3. Implementation and Continuous Feedback

During the implementation phase, teleconsultations and interdisciplinary case discussions were conducted according to the schedule outlined in

Table 2. Three structured round-table discussions supported ongoing reflective monitoring. Nurses provided input on usability, technical issues, perceived benefits, and barriers. Key qualitative observations included improved communication (

“The communication with the physicians is always respectful and we were able to solve problematic cases jointly”, NH A) and time savings (

“It would cost us a lot more time to arrange a transport and accompaniment for our residents to a practice than the telecare contact does”, NH B). They enhanced technical and diagnostic skills among nursing staff (

“By now I know how the system works, it’s no problem for us to teach the physicians [who are not used to the system yet]”, NH B;

“I feel like a little expert now using the oral scanner and the dentist is always available via video and will directly tell me if a missed a spot [in the mouth]”, NH A). Nurses reported increasing confidence as the telecare system was in use for longer periods. Reported barriers included staff absences, difficulties finding substitutes for scheduled sessions, and recurrent technical issues such as login errors, server interruptions, or failed data transfers. Across both NHs, telecare was perceived as particularly suitable for acute care situations (e.g., respiratory infections, wounds, medication questions), dermatology follow-ups, and dental assessments. In intensive care settings, telecare supported the evaluation of secretion management, therapy progress, ventilation adjustments, and assessments of weaning potential.

3.4. Quantitative Results

A total of 152 telecare cases with the predefined contacts were documented for 69 residents, with 31 residents receiving multiple assessments. Three unplanned additional contacts were provided by an emergency physician specialized in trauma care for two patients. The majority of interactions involved the general practitioner offering infectious disease consultations, including a wound specialist (48.7%), and the second most interactions involved dermatologists (23%). Across all cases, the high-resolution wound camera was the most used diagnostic tool (40.7%), followed by the vital signs monitor (28.9%) and the stethoscope (14.4%). 79% of telecare cases were resolved without an on-site visit (although a control via telecare or a secondary control on-site may have been needed), while 21% required resident transport (following discussion of the problem, transport was necessary to resolve it). 82% of all concerns could be managed entirely digitally (there was no need for further on-site contact).

Table 3 presents the results of telecare contacts by specialist and contact reason. Across all documented telecare contacts, physicians rated the general suitability of the cases for digital management with a mean of 4.09 (SD = 1.00) on a 5-point Likert scale, indicating that most situations were perceived as appropriate for telecare. Technical performance was evaluated favorably by physicians (mean = 4.21, SD = 1.22).

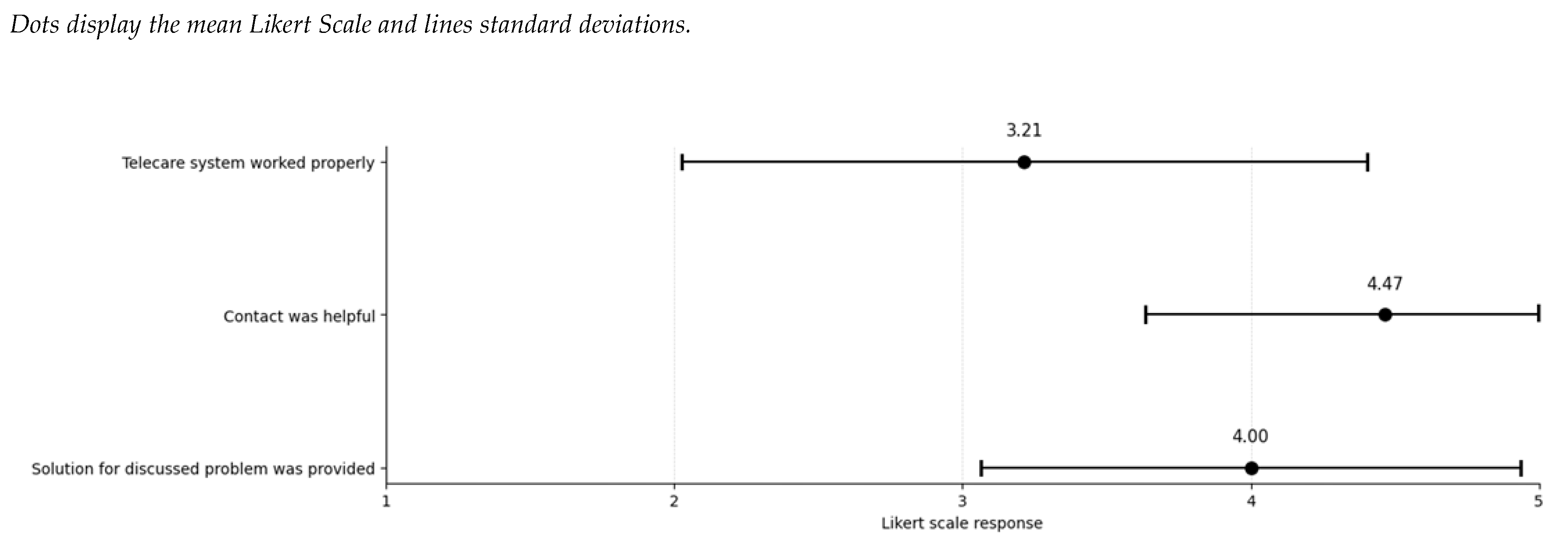

The nurse survey, with a response rate of 41.8% (n = 23 responses), supported these observations. 65.5% of evaluated telecare contacts were referred to consultations with general physicians or infectious disease specialists. The usefulness of the contacts and the extent to which the problem could be resolved consistently received high ratings on the Likert scale. In contrast, the technical functioning of the system was judged more variably compared to the physicians’ ratings.

Figure 1 displays the average ratings of the nurses, along with the standard deviation, for the three assessed aspects.

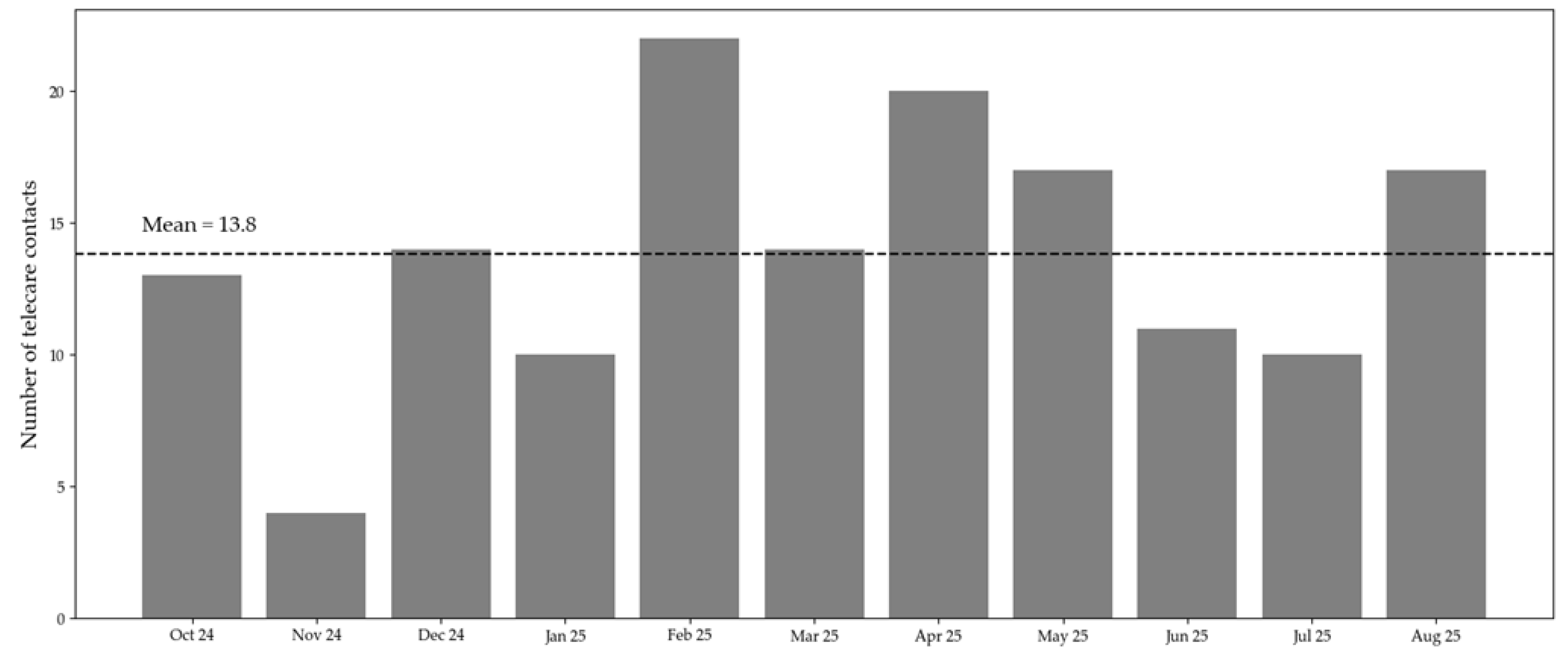

Usage patterns of the telecare system over time are displayed in

Figure 2. There were fewer contacts in November 2024 and June and July 2025. Additional researchers’ notes revealed a staff shortage due to a wave of illness and public holidays. Those months were challenging for the NHs regarding maintaining routine care, and additional tasks like telecare could not be prioritized during these times.

3.5. Facilitators and Barriers

Several factors supported the implementation of telecare in both NHs. The early involvement of nursing staff in the co-design phase played a central role, as it created a sense of ownership and ensured that the emerging telecare workflows were aligned with the realities of daily care. Practical, hands-on training, combined with the availability of technical support, further contributed to growing digital competence and confidence among staff. The advanced skills of nurses using the telecare system enabled them to train physicians on the system, thereby enhancing the confidence aspect. Over time, the regular feedback rounds established a reliable structure for identifying and resolving technical or organizational issues, allowing the telecare model to be adjusted where necessary. Participants also emphasized that respectful and solution-oriented communication with physicians helped create a positive working atmosphere and reinforced their motivation to engage with the system. Also, nurses reported that residents showed a surprisingly high acceptance of the telecare system. Residents were curious about trying the digital contacts and felt adequately treated by the connected medical professionals.

Additionally, barriers to implementation were identified. Technical limitations, including unreliable electronic prescription transmission to pharmacies, led to delays in care processes. Legal and reimbursement constraints, such as lower reimbursement rates for video consultations compared to home visits and difficulties in processing health insurance cards, hindered the consistent participation of external physicians.

Furthermore, organizational and structural factors affected the scalability of the intervention. Its effectiveness was highly dependent on local conditions, and procedures that functioned well within the participating NHs, like sticking to the scheduled timeslots, were not readily transferable to other settings, like practices. Finally, interoperability issues between information systems and heterogeneous interpretations of data protection regulations across institutions further complicated implementation.

3.6. Future Needs/ Need for Long-Term Implementation

At the end of the intervention phase, each NH was invited to talk about the translation of the telecare concept into routine care. Nurses and NH management agreed that several internal, general, and political conditions are necessary to maintain the intervention (telecare workflows and diagnostic support) as well as the implementation strategy (training, feedback structures, and adaptation mechanisms).

Internal and organizational aspects mentioned included the need for a stable technical infrastructure, continuous training and support, and smooth integration of telecare into daily workflows. Participants emphasized the importance of interoperable interfaces with nursing documentation systems and the compatibility of devices and software solutions. Ongoing capacity building and the inclusion of digital and telemedical competencies in staff education were viewed as essential for long-term use.

Financial and regulatory conditions were identified as decisive external factors. Participants emphasized the absence of clear reimbursement structures for teleconsultations in long-term care, as well as the lack of funding for licenses, maintenance, and technical equipment. While physicians have reimbursement opportunities for NH, there is no way to get compensated for the additional effort, except during funded projects. They also emphasized the need for clear and uniform guidance on documentation, data protection, and patient consent procedures.

System-level interoperability challenges, particularly limited data exchange between nursing homes, practices, hospitals, and pharmacies, were seen as barriers to scaling the intervention. Seamless data transfer was considered necessary to avoid redundant documentation and ensure continuity of care. Finally, strategic and political support were discussed as a precondition for sustainable implementation. Participants considered the integration of telecare into national or regional digital health strategies, along with consistent coordination between policymakers, insurers, and professional associations, to be essential for future scaling. Regular evaluations of outcomes, user satisfaction, and process quality were considered necessary to ensure long-term quality and acceptance.

4. Discussion

This study examined the early implementation of a telecare system in two long-term care facilities and identified the factors influencing its feasibility, acceptability, and integration into daily care. Overall, telecare was perceived as helpful by nurses. Physicians rated most cases suitable for complete digital contacts. Telecare facilitated timely medical assessments for residents and improved interprofessional communication. Nurses reported increasing digital confidence and competence over time, which reflects the mechanisms targeted by the implementation strategy, namely engagement, capacity building, workflow integration, and iterative refinement. The study design, with its participatory approach, was welcomed by the involved participants and demonstrated high compliance among those involved from the outset, although onboarding of additional staff later proved more challenging. Feedback loops allowed for ongoing technical and workflow adjustments, consistent with the adaptive nature of implementation in complex care environments.

Our findings demonstrate that telecare is feasible and acceptable in long-term care facilities. Still, its successful implementation depends on a set of process- and context-related factors, which aligns with existing evidence [

12,

13]. The results are consistent with former studies, which emphasize the iterative nature of digital adoption and the importance of active stakeholder participation, training, and technical adaptation [

4,

14,

15]. The result, in which later-onboarded staff expressed more uncertainty, is supported by Normalization Process Theory, which emphasizes that early shared understanding and collective commitment are strong predictors of sustained adoption [

16].

4.1. Implications

Based on our findings and the broader policy landscape, several strategic recommendations can be derived to enable the long-term, scalable integration of telecare into long-term care facilities. Regarding the sustainability of the intervention as a first step, telecare should be routinely reimbursable for NHs nationwide, including coverage of license, maintenance, and technical infrastructure costs. Furthermore, interoperable data interfaces between nursing documentation systems, outpatient and inpatient electronic records, and pharmacy systems should be legally mandated to eliminate double documentation and data silos. National initiatives, such as Germany’s Digitalization Strategy [

17] and the newly obligatory use of the Telematics Infrastructure (TI) [

18], as well as the emerging European Health Data Space (EHDS) [

19], support this. However, NHs require practical guidance and financial support to implement these requirements effectively. Embedding telecare competencies into nursing education and establishing continuous evaluation structures will be essential to maintain quality and acceptance over time. This will also support the scalability of the implementation strategy, which will require standardized digital infrastructure, structured capacity building for long-term care facilities, and cross-sector coordination among NHs, physicians, hospitals, and technical providers.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include its well-working participatory design, the use of multiple complementary data sources, and the real-world nature of the implementation context. The evaluation captured both quantitative indicators of use and qualitative observations regarding mechanisms of change. As part of a pilot program funded by the Statutory Health Insurance Association (German: GKV) [

20], the study contributes to ongoing discussions on the future role of telecare in German long-term care.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this pilot study involved only two long-term facilities in a single region and lacked a control group, thereby limiting its generalizability. Second, due to funding constraints, the implementation period was restricted to 11 months, which precludes conclusions about long-term adoption. Third, the data relied partly on self-reports from nurses and physicians, making recall and social desirability bias possible. Finally, both NHs had relatively favorable organizational conditions, including stable physician networks. Barriers and facilitators may differ in regions with less medical support, lower digital readiness, or more constrained resources, which may affect the transferability of the implementation experiences observed.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that telecare is feasible and well-accepted in NH workflows when supported by a participatory and iterative implementation strategy. The co-design approach enabled infrastructure, processes, and competencies to evolve in tandem with users need, resulting in enhanced communication, growing digital confidence of nurses, and more efficient care coordination. However, long-term implementation will require the establishment of stable reimbursement structures, interoperable documentation systems, and continuous professional development that is embedded within the organizational culture.

At the policy level, telecare should be recognized as a routine element of Germany’s digital health ecosystem and supported through harmonized regulation, financing, and data standards across sectors. Future research should investigate scalability, clinical and economic outcomes, and the alignment of implementation strategies with evolving national and European digital health infrastructures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and J.CB.; methodology, M.H.; software, M.H.; validation, M.H., F.G; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, M.H., S.R., J.D., S.D., T.P.S., P.J., A.B., J.M.F., D.K., A.Y.; resources, J.C.B., A.B., D.K., A.Y.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, F.G., S.R.; visualization, M.H.; supervision, J.C.B.; project administration, S.R, M.V., T.N.; funding acquisition, M.H., J.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GKV-Spitzenverband as part of the model program under § 125a of SGB XI (Social Security Code XI), grant number D_030_ST. The APC was funded by Healthcare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of University Hospital RWTH Aachen (EK 24-290).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating nurses and nursing homes, as well as nursing home residents, for enabling our study. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Grammarly and OpenAI’s ChatGPT-5 language models to assist with language refinement in the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFIR |

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| DNT |

Digital nursing technologies |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EHDS |

European Health Data Space |

| GKV |

German: Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung |

| NH |

Nursing Home |

| SGB |

German: Sozialgesetzbuch |

| TI |

Telematics Infrastructure |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| |

Linear dichroism |

References

- World Health Organization. State of the World’s Nursing 2020: Investing in Education, Jobs and Leadership; 978-92-4-000327-9; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020.

- Kubek, V. Digitalisierung in der Pflege: Überblick über aktuelle Ansätze. In Digitalisierung in der Pflege: Zur Unterstützung einer besseren Arbeitsorganisation, Kubek, V., Velten, S., Eierdanz, F., Blaudszun-Lahm, A., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 15-20.

- IGES Institut. Zwischenbericht: Effizienzpotenziale durch digitale Anwendungen in der Pflege; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit: Berlin, 2022.

- Walzer, S.; Armbruster, C.; Mahler, S.; Farin-Glattacker, E.; Kunze, C. Factors Influencing the Implementation and Adoption of Digital Nursing Technologies: Systematic Umbrella Review. J Med Internet Res 2025, 27, e64616. [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.; Lau, X.K.; Ignacio, J. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of telemedicine in nursing homes: A qualitative systematic review and meta-aggregation. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2024, 21, 318-329. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L.D.; Husebo, B.S.; Vislapuu, M. Promotors and barriers to the implementation and adoption of assistive technology and telecare for people with dementia and their caregivers: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-F.; Wang, H.-H.; Chien, I.K.; Liou, J.-K.; Hung, C.-L.; Huang, C.-M.; Yang, F.-Y. Healthcare providers’ perceptions of barriers in implementing of home telecare in Taiwan: A qualitative study. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2015, 84, 277-287. [CrossRef]

- Wüller, H.; Koppenburger, A. Digitalisierung in der Pflege. In Systematische Entwicklung von Dienstleistungsinnovationen : Augmented Reality für Pflege und industrielle Wartung, Wiesche, M., Welpe, I.M., Remmers, H., Krcmar, H., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, 2021; pp. 111-124.

- Kilfoy, A.; Hsu, T.-C.C.; Stockton-Powdrell, C.; Whelan, P.; Chu, C.H.; Jibb, L. An umbrella review on how digital health intervention co-design is conducted and described. npj Digital Medicine 2024, 7, 374. [CrossRef]

- Pinnock, H.; Barwick, M.; Carpenter, C.R.; Eldridge, S.; Grandes, G.; Griffiths, C.J.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Meissner, P.; Murray, E.; Patel, A.; et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013318. [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science 2022, 17, 75. [CrossRef]

- Krick, T.; Huter, K.; Domhoff, D.; Schmidt, A.; Rothgang, H.; Wolf-Ostermann, K. Digital technology and nursing care: a scoping review on acceptance, effectiveness and efficiency studies of informal and formal care technologies. BMC Health Services Research 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J Med Internet Res 2017, 19, e367. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.E.; Allison, T.A.; Flint, L.A.; David, D.; Wertz, V.; Halifax, E.; Barrientos, P.; Ritchie, C.S. Assessing Technical Feasibility and Acceptability of Telehealth Palliative Care in Nursing Homes. Palliative Medicine Reports 2022, 3, 181-185. [CrossRef]

- Offermann, J.; Wilkowska, W.; Schaar, A.K.; Brokmann, J.C.; Ziefle, M. What Helps to Help? Exploring Influencing Human-, Technology-, and Context-Related Factors on the Adoption Process of Telemedical Applications in Nursing Homes. Springer Nature Switzerland: 2023; pp. 273-295.

- May, C.; Finch, T. Implementing, Embedding, and Integrating Practices: An Outline of Normalization Process Theory. Sociology 2009, 43, 535-554. [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Health. Germany’s Digitalisation Strategy for Health and Care; Federal Ministry of Health: Berlin, 2023.

- Federal Ministry of Health. Telematics Infrastructure (TI): Secure digital networking in the health system. Available online: https://gesund.bund.de/en/telematics-infrastructure (accessed on 14.11.2025).

- European Commission. European Health Data Space (EHDS) – Regulation Proposal; European Commission: Brussels, 2022.

- GKV Spitzenverband. Modellprogramm nach § 125a SGB XI – Telepflege. Available online: https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/pflegeversicherung/forschung/modellprogramm_125a_sgb_xi/pflege_modellprojekte_125a.jsp (accessed on.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).