1. Introduction

Clinical note summarization, such as standardization of patient handoffs, can improve the continuity of care by reducing communication errors and supporting clinical workflow [

1]. Large language models (LLM) offer a promising opportunity to automate the summarization of clinical documentation [

2,

3], potentially alleviating these challenges. This research brief addresses concerns regarding the accuracy, completeness, and reliability of LLM-generated summaries in clinical practice.

2. Methods

Progress notes from 385 pediatric Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit (CVICU) patients treated at a tertiary pediatric health system in Southern California were retrieved and deidentified for the study. The use of these notes was approved under IRB #230571. For each patient, all original progress notes were combined into a single file to keep the full clinical context available to the LLM.

The summaries of the patient notes were generated using the Mistral 7B LLM via AWS Bedrock. Prompts were formatted according to the iPASS handoff framework [

4]. Readability was assessed using Flesch Reading Ease [

5], Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level [

6], Gunning Fog Index [

7], SMOG Index [

8], Automated Readability Index [

9], and Dale-Chall Score [

10]. In parallel, cosine similarity was computed between each original note and its corresponding summary using vector embeddings to evaluate how well the model preserved core semantic content.

Clinician evaluation was conducted on a stratified random sample of 10 patient summaries by three pediatric resident physicians (post-graduate year (PGY) 1-3). Each resident rated the summaries on a 5-point Likert scale across three domains: completeness (inclusion of key clinical information), correctness (factual accuracy and absence of hallucinations), and conciseness (brevity without omitting critical details). Rating rubrics were standardized and distributed prior to evaluation to ensure consistency.

3. Results

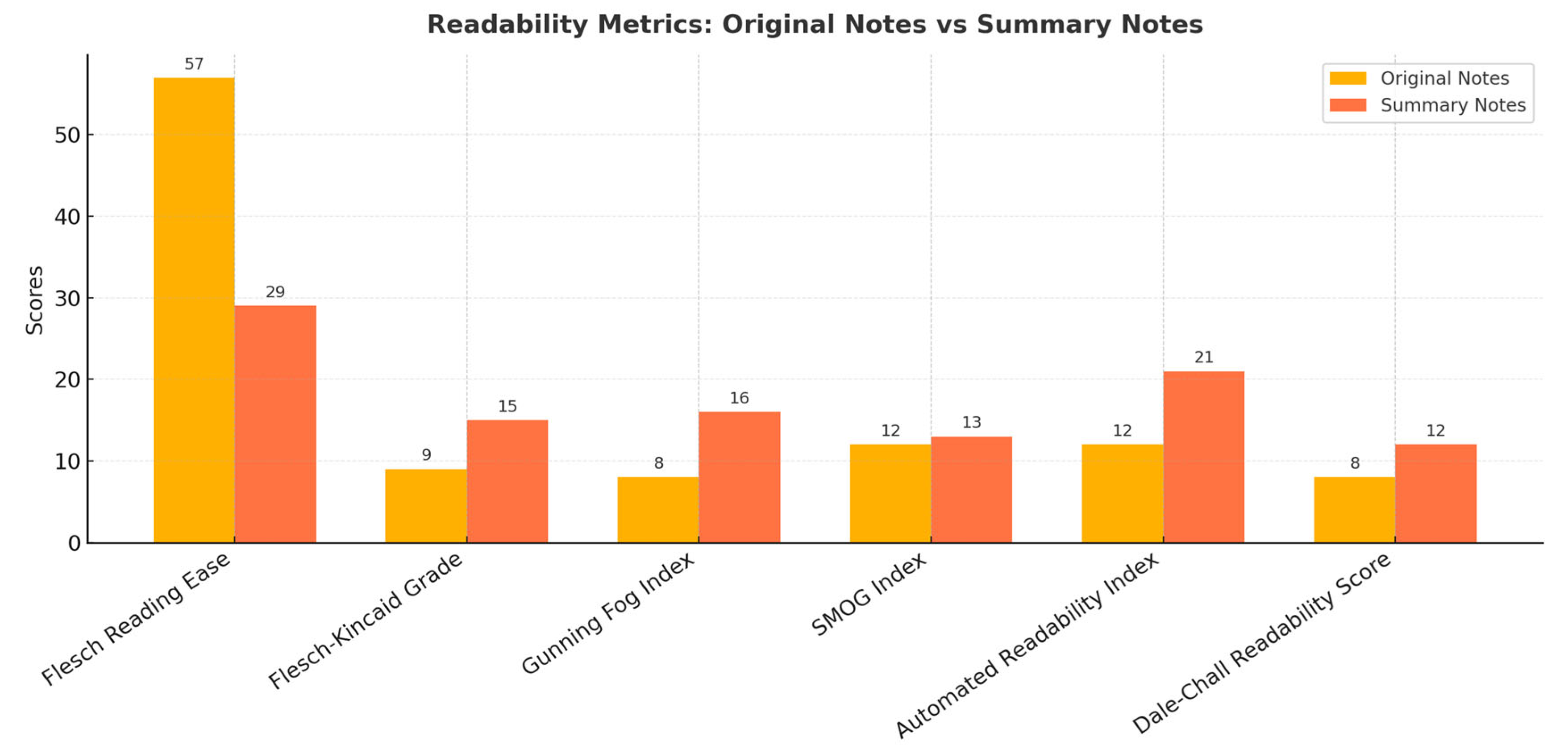

Across all six-readability metrics (

Figure 1), the original notes were easier to read and understand. The summaries required higher reading levels, scoring 15 on the Flesch-Kincaid (college-level) and 16 on the Gunning Fog (college senior), while the original notes were easier to read, with a much higher Flesch Reading Ease score of 57 (indicating easier reading) compared to 29 for the summaries (indicating harder reading) (

Figure 1).

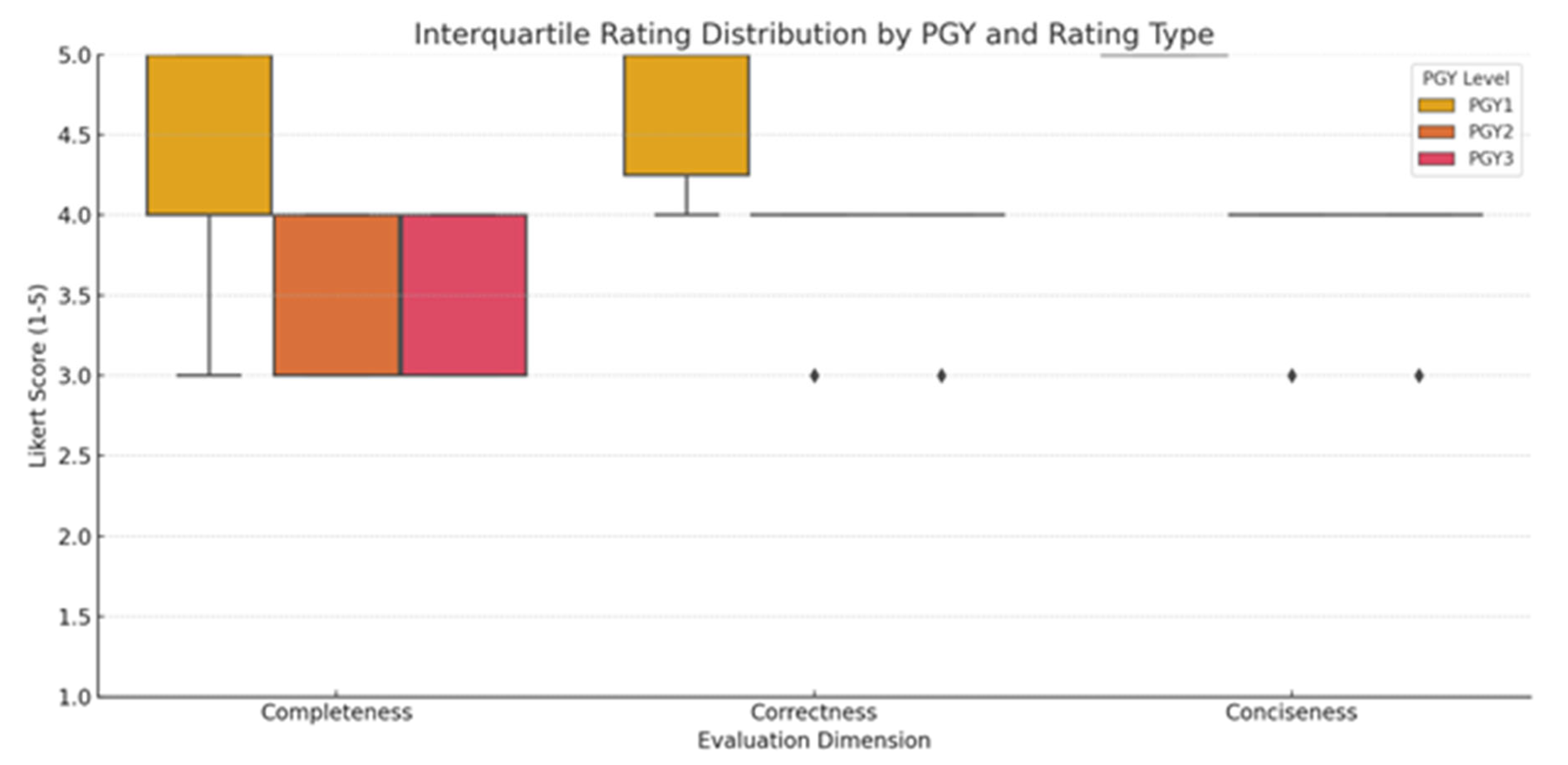

Pediatric resident evaluation scores are summarized in

Figure 2. A PGY1 resident provided consistently higher ratings across all domains, especially for correctness and conciseness, suggesting a greater tolerance for minor omissions or abstraction. In contrast, both PGY2 and PGY3 residents demonstrated greater variability in their ratings, particularly for completeness, which had higher variance (indicating more sensitive to missing or ambiguous clinical details). While conciseness received the highest average ratings overall, both PGY2 and PGY3 evaluators rated some summaries lower due to omitted context that affected interpretability

4. Discussion

The use of artificial intelligence to generate clinical summaries may result in a less readable summary of the patient. The experience may differ by clinician experience, as a junior resident often perceived the summaries generated as more useful, while senior residents were more likely to notice missing details or limitations. Summaries were notably shorter and easier to scan, appealing especially to a junior resident who favored their brevity and clarity. Despite their shorter length, the summaries were harder to read according to standard readability metrics (

Figure 1), the usability of which may be compounded by abstraction and omitted context. In addition, conciseness came at the cost of completeness, with concerns about missing clinical details. This highlights a higher expectation for contextual depth with increased clinical experience. These trends suggest that perceived summary quality is partially influenced by clinical experience and expectations of detail. LLM-generated summaries may miss important details needed by experienced clinicians or in complex cases, leading to increased cognitive burden by requiring verification against the full note set. Future research should focus on improving abstraction which may require improvements in the organization of the source documentation.

Author Contributions

Albert Kim, MDa,c, Brian Walker, MDa,c, and Sabrina Leong, MDa,c annotated the clinical notes to compare whether the summaries reflected clinician evaluations. Clinician evaluation was conducted on a stratified random sample of 10 patient summaries by three pediatric residents. Vanessa I. Klotzman, MSca,b, ran the large language model and conducted the analysis. She also drafted the initial manuscript. Louis Ehwerhemuepha, PhDa,c, and Robert B. Kelly, MDa,c, conceived the study idea, supervised the project, and contributed to manuscript proofreading and revisions. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Children’s Hospital of Orange County In-House (CHOC IH) IRB, Orange, CA (IRB Number 230571) on 16 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board because the study involved retrospective analysis of de-identified clinical data and posed minimal risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement:

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Role of Funder/Sponsor (if any)

There was no funder or sponsor for this study.

Clinical Trial Registration (if any)

There was no clinical registration.

Abbreviations

Large Language Model (LLM), Amazon Web Services (AWS)

References

- Feblowitz, J. C., Wright, A., Singh, H., Samal, L., & Sittig, D. F. (2011). Summarization of clinical information: a conceptual model. Journal of biomedical informatics, 44(4), 688-699. [CrossRef]

- Fraile Navarro, D., Coiera, E., Hambly, T. W., Triplett, Z., Asif, N., Susanto, A., ... & Berkovsky, S. (2025). Expert evaluation of large language models for clinical dialogue summarization. Scientific reports, 15(1), 1195.

- Van Veen, D., Van Uden, C., Blankemeier, L., Delbrouck, J. B., Aali, A., Bluethgen, C., ... & Chaudhari, A. S. (2024). Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nature medicine, 30(4), 1134-1142.

- Starmer, A. J., Spector, N. D., West, D. C., Srivastava, R., Sectish, T. C., Landrigan, C. P.,... & Shah, S. (2017). Integrating research, quality improvement, and medical education for better handoffs and safer care: disseminating, adapting, and implementing the I-PASS program. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(7), 319-329.

- Flesch, R. (1948). A new readability yardstick. Journal of applied psychology, 32(3), 221.

- Kincaid, J. P., et al. “Flesch-kincaid grade level.” Memphis: United States Navy (1975).

- Gunning, R. (1952). The technique of clear writing (pp. 36–37). McGraw-Hill.

- Mc Laughlin, G. H. (1969). SMOG grading-a new readability formula. Journal of reading, 12(8), 639-646.

- Smith, E. A., & Senter, R. J. (1967). Automated readability index (Vol. 66, No. 220). Aerospace Medical Research Laboratories, Aerospace Medical Division, Air Force Systems Command.

- Dale, E., & Chall, J. S. (1948). A formula for predicting readability: Instructions. Educational research bulletin, 37-54.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).