1. Introduction

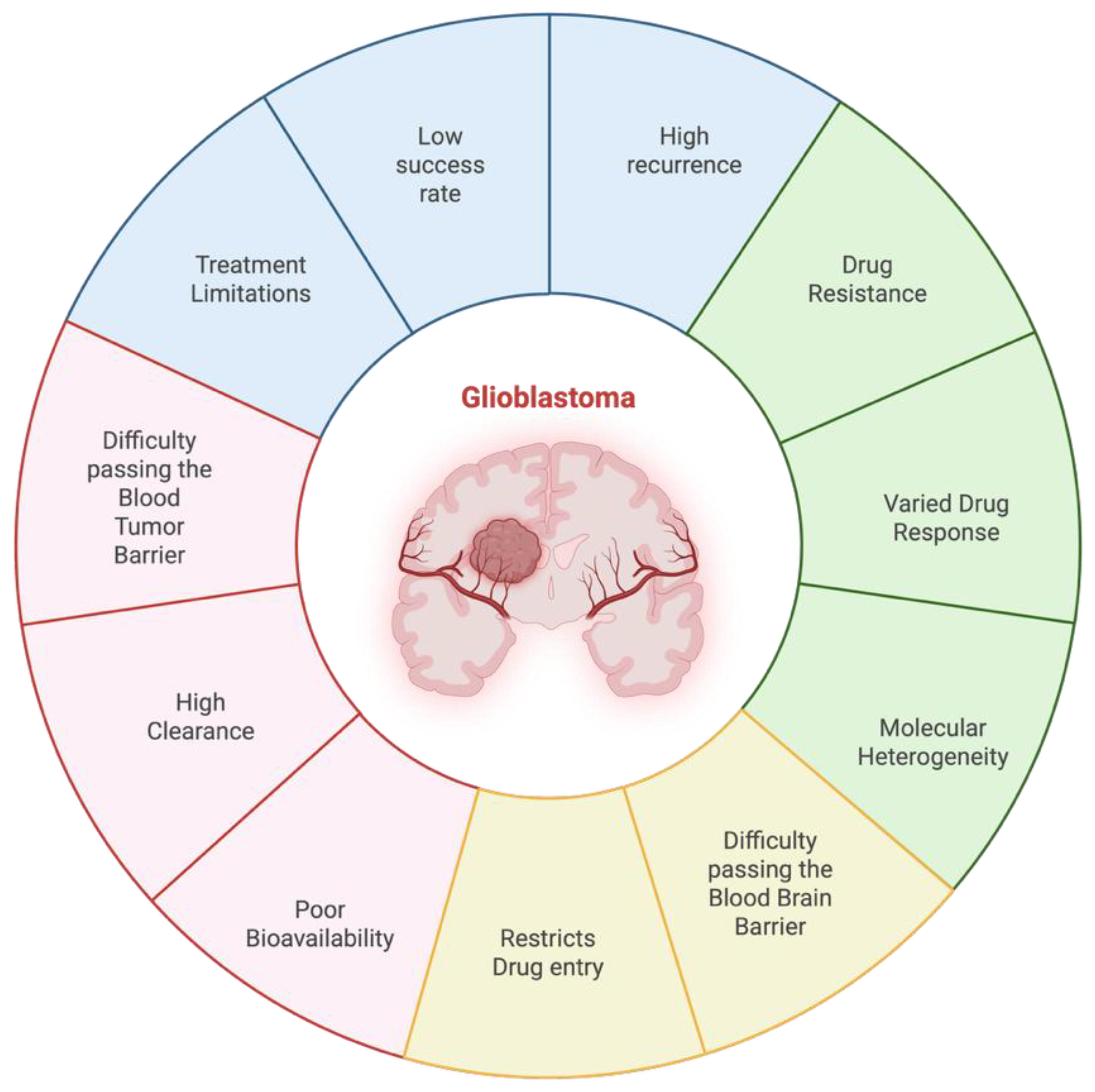

Drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) is a major challenge because of its complex protective mechanism such as blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood–tumor barrier (BTB). These barriers are critical in the regulation of homeostasis as they have selectivity to restrict harmful substances from easily accessing brain structures. However, these protective properties also significantly limit therapeutic agent penetration and the treatment of CNS disorders, such as brain tumors [

1] (

Figure 1). Despite great progress in the fields of neurosciences, molecular biology and pharmacology, the success rate for central nervous system (CNS) drug development is largely disappointing. Only ∼8.2% of drug candidates advance to clinical use, mainly resulting from problems such as poor bioavailability, high clearance of the compound in vivo, and difficulty in crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Therefore, the development of drug delivery systems for CNS diseases such as GBM is important to enhance drug efficacy and patient survival. Emerging drug delivery approaches, such as nanotechnology-based systems, convection-enhanced delivery, and ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption, hold promise in addressing these challenges [

2].

One of the most prevalent and malignant tumors in the central nervous system is glioblastoma (GBM). All tumors originating from the brain’s intrinsic glial cells and supporting tissue are classified as GBM. Every year, about 19 out of 0.1 million people worldwide receive a diagnosis of primary brain tumors and central nervous system (CNS) cancers. 17% of these diagnosed patients have GBM [

3,

4]. Although considered an uncommon disease, glioblastoma (GBM) is still a highly fatal illness; on average, patients survive only 12 to 15 months after initial diagnosis [

5]. GBM is characterized by a rapid proliferation of cells and extensive migration of tumor cells into the surrounding brain, making it impossible to fully remove the tumor [

6]. Whereas improvements have been made in current treatment modalities such as radiotherapy, temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy and maximal safe surgical resection, glioblastoma still presents a high recurrence rate. This is largely due to intra-tumoral molecular heterogeneity, restrictive function of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the ability of the tumor to evade host immunity by means of a localized immunosuppressive environment; all serving as major obstacles for effective treatment [

7].

Solving the issues in drug delivery to glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is critically important for enhancing therapeutic effectiveness, and survival among patients. One of the major obstacles is the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which prevents the passage of most therapeutic drugs into the brain, reducing efficacy of standard therapy [

8]. In addition, the molecular heterogeneity of GBM leads to drug resistance and tumor recurrence because cancer cells in the same tumors might have different responses to therapy [

9]. Recent advancements in nanotechnology have developed smart nanocarriers which are able to cross the BBB and target tumor cells specifically, providing a promising way for improved drug delivery [

10]. Moreover, EVs have risen to the fore as safe and natural drug delivery vehicles (DRVs) that provide direct access to GBM cells with a therapeutic load while escaping immunological clearance and biological blockade [

11]. Overcoming these delivery challenges is essential to developing more effective GBM therapies and improving long-term clinical outcomes.

2. Understanding Glioblastoma Drug Delivery Updates

2.1. Current Treatment Limitations in Glioblastoma Therapy

The standard of care for patients that have been newly diagnosed with Glioblastoma is the Stupp Protocol. This protocol consists of maximal safe resection and radiotherapy with concurrent and adjuvant TMZ (a mono-alkylating agent). Since most recurrences of Glioblastomas occur within 2-3 cm from where the first lesion was, maximal safe resection is guaranteed to enhance survival rates regardless of the patient’s age and the molecular status of the tumor. There are multiple brain mapping techniques which are used before the operation to help enable safe resection. These techniques are functional MRI, navigated transcranial magnetic simulation (nTMS), magneto-encephalography, and diffusion tract imaging. In addition, multiple tools are used during surgery to help improve the degree of resection and to diminish residual tumor volume. One of those tools is fluorescence-based visualization of the tumor using 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA). However, despite the clinical benefits of 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA), its use is associated with several limitations, including a heightened risk of false-positive fluorescence signals, substantial cost, potential toxicity, and challenges related to its administration. Moreover, its diagnostic utility is primarily confined to high-grade gliomas, limiting its effectiveness in detecting lower-grade tumors. Therefore, it is often combined with intraoperative ultrasound (ioUS) or intraoperative MRI (ioMRI) for optimal results. Although carmustine wafers may be applied during surgery to prolong survival, they are not part of the standard protocol due to limited efficacy, safety concerns, and tolerability issues [

12].

2.2. Comparative Analysis of Traditional vs. Innovative Approaches

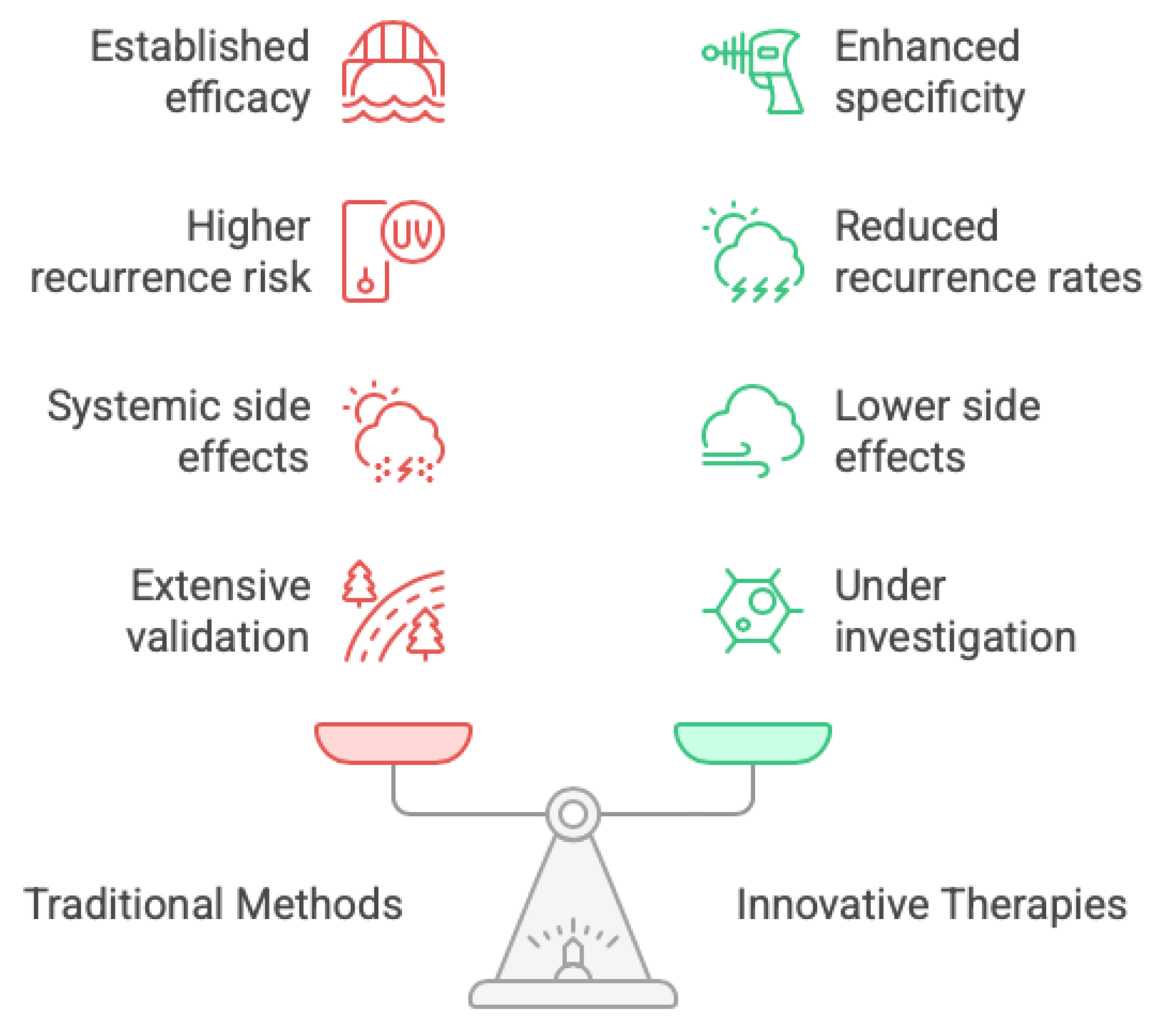

As mentioned above the current traditional methods to treat glioblastomas are those that make up the Stupp protocol which are: surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy (

Figure 2). The surgery aspect, which may be considered the most critical in GBM therapy, involves maximal safe resection of the tumor, however it is quite challenging to resect the tumor fully due to its aggressive nature, and this is what makes the recurrence of glioblastomas strongly probable. The second aspect of the Stupp protocol is postoperative radiation therapy. Both surgical resection and radiotherapy contribute to improved overall survival in GBM patients. Additionally, radiotherapy offers the added advantage of aiding in the control of residual tumor growth following surgical intervention [

12]. Finally, the last aspect of the Stupp protocol is chemotherapy, specifically TMZ administration. TMZ in combination with radiotherapy enhances survival rates. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of TMZ varies widely among different patients, as some patients may develop a resistance to TMZ. Along with those disadvantages come the common side effects which accompany most chemotherapeutic drugs such as fatigue, nausea, immunosuppression, and an overall decrease in the patient’s quality of life [

13].

Besides the Stupp protocol, there have been developments in GBM therapy which led to new innovative treatment techniques, some of which are Targeted Therapy, Immunotherapy, and Combination Therapies [

13]. Targeted Therapy consists of targeting specific molecular pathways involved in the development of glioblastomas. For example, drugs like Erlotinib which are epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors can be used to interrupt the signaling pathways that are necessary for the tumor’s growth. Another example is the drug Bevacizumab which is a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor that inhibits the angiogenesis of the tumor leading the tumor to having no blood supply and hence diminishing its growth [

14]. One main issue faced with targeted therapy is the heterogeneity of Glioblastomas implying that its effects may not be generalized among the population of patients with GBM [

13]. Another innovative technique is immunotherapy, which aim to enrich the body’s immune system’s ability to recognize and attack tumor cells. This can be done by using drugs such as Nivolumab which is a checkpoint inhibitor. This class of drug works by blocking proteins whose normal role is preventing the immune cells from attacking cancer cells, so inhibiting these proteins allows for more immune cells to ablate cancer cells. Immunotherapy also can be delivered by Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell therapy. This method includes the ex vivo editing of T cells to express specific receptors that allow the T cells to identify and attack glioblastoma tissue. But immunotherapy has its limitations. First, the glioblastoma microenvironment is immunosuppressive and may prevent the development of productive anti-tumor immunity. Another major problem that we have encountered, as it occurs in targeted therapies as well, is the very high heterogeneity of glioblastomas [

15]. This heterogeneity makes difficult the implementation of treatments valid for all patients, given that therapeutic responses can strongly vary between patients with diverse molecular and genetic imbalanced tumors.

Another touchstone intervention is that of combination therapy. The aim of combinatorial therapy is to reach the effective combination of multiple treatment techniques, which range from traditional chemotherapy or radiotherapy, to new and emerging options, such as immunotherapy or targeted therapies. This multimodal strategy is expected to act by synergism to enhance its therapeutic effects and overcome resistance encountered with mono-therapies [

12]. Nonetheless, as with other treatments, combined therapy is not without drawbacks. A limitation of this construct is the potential for enhanced toxicity due to a combination of therapeutic approaches. It is therefore important for patients to be carefully monitored and managed during their course of treatment in order to maintain safety and tolerability [

13]. A comparison of the traditional and innovative treatments suggests that based on low specificity, conventional treatments are more likely to instigate recurrences, whereas due to their high selectivity and specificity, novel therapies have a greater potential in specifically destroying glioblastoma cells and consequently in lowering the rate of recurrence. Moreover, novel therapies in general have a better side effect profile since they are targeted agents and carry less risk of systemic adverse effects (although it can happen). A second, more fundamental distinction lies in the depth of clinical validation: conventional therapeutic modalities are underpinned by extensive, rigorously controlled trials that delineate both efficacy and safety across large, heterogeneous patient cohorts, whereas extracellular-vesicle-based interventions currently lack comparable evidence. In contrast, innovative treatments are still under investigation and may produce variable responses depending on individual patient characteristics.

3. Overview of Recent Breakthroughs in Drug Delivery Methods for Glioblastoma

3.1. Nanoparticles and Nanotechnology

Treating, diagnosing, and managing gliomas has undergone a revolution due to the field of nanotechnology. This change is mostly ascribed to more recent developments in bioengineering, easier access to medications, and the capacity to specifically target cancer cells. Because of their small size, large surface area, unique structural features, binding affinity, ability to penetrate cell membranes or tissues, and long elimination half-life in the circulation, nanoparticles (NPs) are becoming more and more used in the field of cancer therapeutics and diagnostics. Their high surface-to-volume ratio enhance their therapeutic effectiveness by delivering tiny biomolecules like proteins, nucleic acids, and medications to the target region. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier has been shown to be improved by a number of strategies, many of which involve disrupting the BBB. Consequently, the integrity of the cerebral microvasculature is compromised by this disruption. The administration of anticancer drugs via polymers or lipid NPs is one method that shows promise [

16].

The use of certain nanoparticles in glioblastoma monotherapy has given promising results.

Eugenio et al. demonstrated that silver/silver chloride nanoparticles (Ag/AgCI-NPs) significantly inhibited the proliferation of GBM02 glioblastoma cells, with efficacy surpassing that of temozolomide, particularly at higher nanoparticle concentrations. Kesinostat, a histone deacetxase inhibitor has the ability to cause apoptosis, improve cell differentiation, and induce cell cycle arrest but has limited application due to inadequate delivery. Nevertheless, Kesinostat encapsulation in poly (D, L-lactide)-b-methoxy poly (ethylene glycol) nanoparticles produced favorable results, increasing the survival rates of experimental animals [

16]. Human serum albumin nanoparticles containing chlece-aluniou phthalocyanine (AlCIPc) on U87MG cells were used in order to investigate various light sources in photodynamic treatment. Apoptosis was the major mode of cell death in all cases, according to flow cytometry analysis [

17].

Reaching the tumor site without harming the healthy tissues is one of the major problems in cancer treatment. The BBB is the primary obstacle to medication delivery in malignant gliomas.

Additionally, P-glycoprotein lowers the drug’s effective concentration by pumping the utilized medications out of the cell using ATP. It is possible to combine medications used to treat glioblastoma into NPs and functionalize them with different ligands to allow them to cross and target the BBB. Apart from appropriate administration, medication stability rises and unfavorable side effects are somewhat decreased [

16]. Moreover,

Table 1 compares the IC₅₀ values of different nanoparticle formulations across various glioblastoma cell models.

Nanocarriers can be engineered from a variety of materials, including organic compounds, metals. minerals, and polymers. These nanosystems have been utilized to deliver a range of anticancer agents-such as temozolomide, paclitaxel, docetaxel, cisplatin, doxorubicin, curcumin, and nucleic acids directly to the brain, enhancing drug bioavailability and targeting efficiency.

Despite their therapeutic promise, however, there remain serious safety concerns. Importantly, a critical translational barrier remains the unresolved risk that certain nanoparticle formulations may act as carcinogenic initiators or induce genotoxic injury. Further studies are needed to address these concerns in order to safely translate nanoparticle-based therapeutics into the clinic [

16].

3.2. Convection-Enhanced Delivery (CED)

Passage of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is one of the common problems in drug delivery to gliomas. An approach that bypasses the BBB, and allows for direct distribution within the brain, is convection-enhanced delivery (CED) which can deliver drugs to the brain that are normally blocked by this barrier [

18]. The CED process is designed to confine more than 99% of the therapeutic payload within the tumor bed, effectively sparing the surrounding brain from exposure by circumventing the blood–brain barrier rather than traversing it. To accomplish this, a stereotactic infusion cannula is accurately aimed at the target and a controlled positive pressure difference is used to distribute the infusate across brain parenchyma. In contrast, most traditional drug delivery systems largely depend on a passive diffusion mechanism where molecular size directly dictates tissue penetration and distribution—and can thereby impose significant obstacles for larger therapeutic agents. On the other hand, CED offers a significant advantage in that drug distribution which is predominantly influenced by hydrostatic pressure gradients as opposed to molecular size, allowing for the delivery of a broader range of therapeutic agents [

19].

The device, which usually delivers therapy in a substantially spherical manner, dispenses at approximately 0.5 to 10 µL/min. Unlike single injection application which targets up to five millimeters from the tip of the catheter, CED allows distribution of therapy up to 6 cm from the tip of catheter and provides an over-4000 fold increase in volume of distribution. Second, besides its directed application and fast delivery, CED minimizes the toxicities of systemic drug injection by offering highly specific tumor bed targeting [

20].

Despite the fact that CED has shown substantial superiority in drug delivery, several factors should be considered during its application. Procedure associated with CED catheter insertion may contribute to intra-cerebral edema. Accordingly, the majority of clinical protocols limit tumor size to 4 cm and exclude patients with posterior fossa tumors because larger lesions are often associated with neurological deterioration. In these cases, the excess volume by infusions can deteriorate intracranial pressure as undesirable rather than beneficial. Catheters are placed 1–2 cm from subarachnoid spaces and resection cavities and no closer than 0.5 cm to the ependymal surface in an effort for fewer complications and improved delivery accuracy. Furthermore, it is important for the catheter material to be tailored such that it has appropriate stiffness so as to maintain trajectory yet flexibility required for accurate delivery to a desired target location [

18].

Proceeding to the technical enhancements required for improving CED (cf.

Table 2), a significant issue remains which is the backflow of infused material along the cannula track, especially at high flow rates. This restriction happens when the pressure differential between the catheter tip and tumor tissue reaches an equilibrium and a retrograde mode occurs with diluted drug against targeted drug delivery [

18]. A solution to this problem has been to provide a stepped cannula. This altered cannula has a stepped design that acts as an anatomical back-stop, minimizing the risk of retrograde flow in both the body of the cannula and along the outer luminal tract [

19]. These developments are necessary to improve both dose accuracy and therapeutic potential.

3.3. Implantable Drug Delivery Devices

Implantable drug delivery devices (IDDDs) are a newly developed strategy to improve the treatment of GBM by enabling localized pharmacotherapy, and compensating for the blood-brain barrier (BBB) hindrance. A well-known example is the Gliadel®️ wafer, a biodegradable polymer containing carmustine (BCNU) that is implanted directly to the resection cavity after surgery for sustained local chemotherapy. It has been shown to increase survival compared with systemic chemotherapy only in clinical trials.[

21].

The progress in microfabrication technology has made it possible to implant multifunctional microdevices with capabilities of delivering multiple therapeutic agents concomitantly, which offers a full-spectrum approach for glioblastoma (GBM) therapy. For instance, 3D-printed patient-specific implants mediating the controllable release of DNA-nanocomplexes have been applied to the localized GBM treatment, indicating an opportunity for personalized medicine in this field [

22].

Nevertheless, some issues remain despite these progressions. Some implants, including the Gliadel®️ wafer, have a stiff structure that might cause suboptimal drug dispersion by cerebrospinal fluid diffusion and a mechanical mismatch with the soft brain tissue and undermine therapeutic effects. Moreover, the invasiveness of implantable devices is also an issue, as it introduces biocompatibility and infection problems that mandate rigorous surgical procedures and follow-up handling [

23].

Novel approaches are now attempting to avoid these issues by developing soft, biodegradable implants that can conform to the brain’s complex form and allow for more accurate drug delivery with less safety risk for the patient. For example, hydrogel-mediated systems have been engineered to invigorate chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in situ within the tumor microenvironment which is a novel strategical innovation for treating GBM [

24].

In summary, although IDDDs are a promising battleground against GBM, further investigation is needed to improve formulations, biocompatibility and clinical usability.

3.4. Focused Ultrasound

Focused ultrasound (FUS) is a method using concentrated beams of ultrasonic energy for highly precise targeting in the depths of the brain while avoiding damage to surrounding normal tissue. Once in the specific area, these FUS waves can cause several effects on tissues. First, high-intensity acoustic energy is sent to the tumor using focused ultrasound (FUS) to induce a sudden increase of temperature in the local region. This elevation in temperature results in irreversible cellular injury with either coagulative necrosis of tumor cells (i.e., tumour ablation). Thus, FUS achieves a tumor volume reduction with direct destruction of cancerous tissue and preservation of neighboring non-cancerous structures.

Furthermore, FUS can also improve the delivery of drugs to the tumor (

Table 3). It achieves this by briefly breaking down the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to let drugs into the tumor, where they can act on cancer cells. FUS is a safe approach to avoid complications related to invasive methods. It also allows the treatment to be seen while it is happening and makes it possible to adjust the procedure, if needed. Moreover, because FUS employs spatially confined acoustic energy, selectively engaging the target tissue while sparing adjacent neural and perilesional structures, the possibility for damaging healthy brain tissues around stimulated areas is reduced which means decreasing the probability of side effects.

Although a promising modality for the treatment of various diseases, focused ultrasound (FUS) faces a number of obstacles, and anatomic barriers are one of them. Because the skull is a dense and inhomogeneous material, it can block efficient ultrasounds propagation which could cause distortion, attenuation, or energy losses before reaching the focused position in brain tissue. This limitation may prevent the accuracy and effectiveness of FUS especially in treating deep-seated or centrally located brain tumors. Moreover, breach of the blood-brain barrier may induce inflammation, causing adverse effects and making recovery more complex [

25].

3.5. Electrochemotherapy

Electrochemotherapy (ECT) is a treatment that combines electroporation (EP), which involves the use of electrical pulses, with the injection of a chemotherapeutic drug. The electrical pulses open pores in the cell membrane, allowing increased influx and efflux of molecules. Normally cancer cells typically exhibit poor drug uptake so using this technique increases the uptake of anticancer drugs into the cancer cells [

26].

Electroporation can be broken down into three stages at the level of a single cell, first, the induction step, where the field-induced membrane potential difference reaches the critical threshold value; second, the expansion step, where membrane defects continue to exist as long as the field is present; and third, the resealing step, where the membrane repairs, which is necessary to maintain cell viability [

27]. Patients can get medication in ECT through two major methods: The medicine can be administered intravenously or intratumorally, which involves injecting the drug directly into the tumor [

26]. Administration of drugs during both the pulse and slow resealing phases results in a major increase of drug intracellular concentration. This amount is multiplied almost 100-fold when compared to conventional chemotherapy [

27].

Regarding the brain, ECT is mainly applied to the blood-brain barrier in order to make it more permeable to drugs that are otherwise unable to cross it, however intra-tumoral ECT is still under study. Bleomycin and Cisplatin are charged drugs that have shown high therapeutic efficacy in tumors when used with ECT, but they are impermeable to the blood-brain barrier; so, making the BBB more permeable using this technique would create opportunities for effective drug therapies [

28]. Regarding glioma treatments, application of intra-tumoral ECT in rat glioma showed a 69% complete response rate where 9 out of 13 rats had tumor regression. However, MRI data exposed necrosis to the area subjected to the treatment, as well as some fluid filled cavities. It was demonstrated that some risks associated with the use of ECT include edema, hemorrhage, infection, or epileptic events prompted by excitation of surrounding tissue [

28].

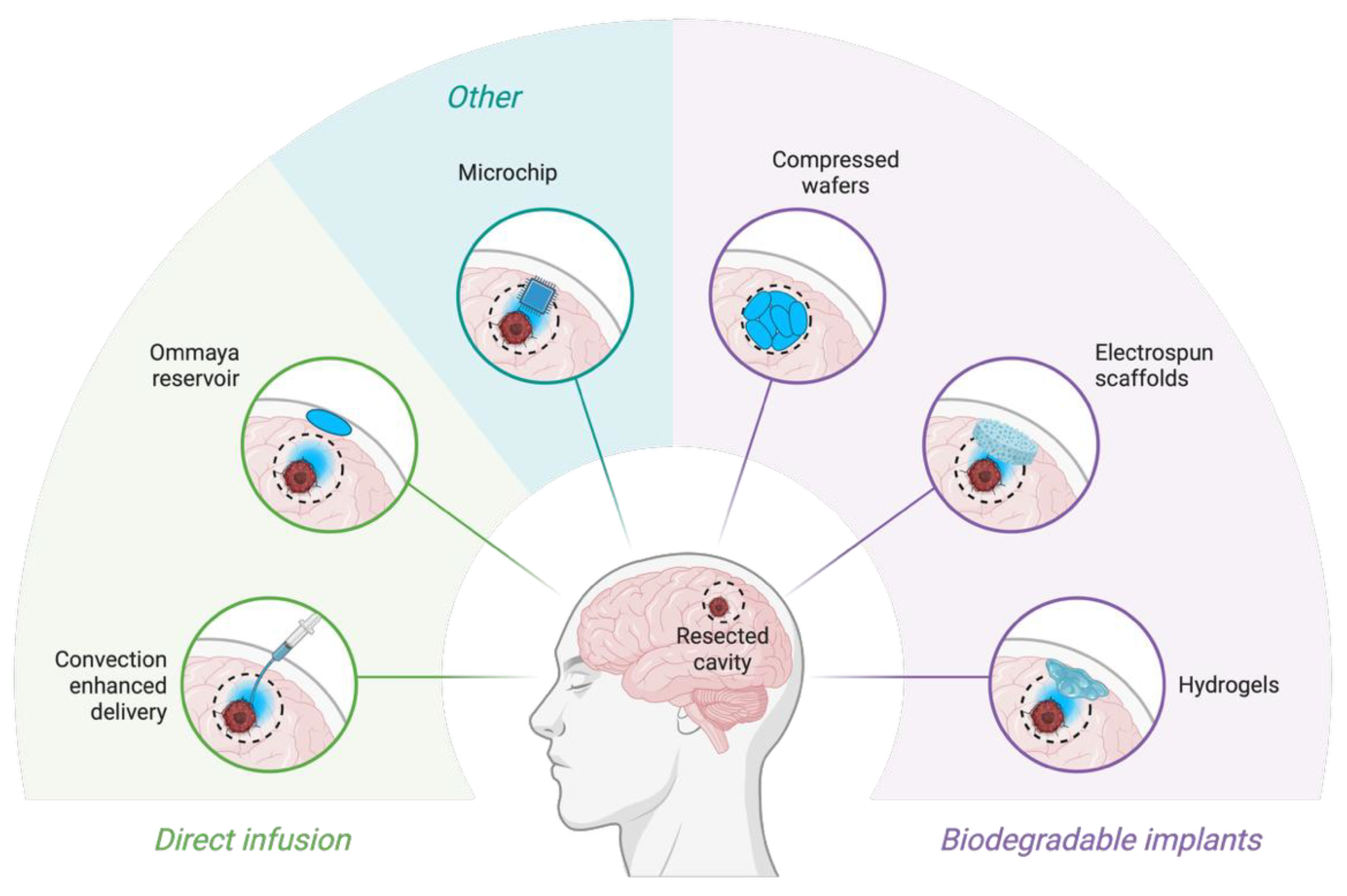

Figure 3.

Novel drug-delivery systems for glioblastoma. Schematic overview of local drug-delivery strategies applied directly into the surgical resection cavity of glioblastoma. Approaches are grouped into direct infusion systems (e.g., convection-enhanced delivery catheters, Ommaya reservoirs) and biodegradable implantable systems (e.g., hydrogels, electrospun scaffolds, compressed polymer wafers). Other emerging strategies include implantable programmable microchips allowing controlled spatiotemporal release of therapeutics. Created with Biorender (

www.biorender.com).

Figure 3.

Novel drug-delivery systems for glioblastoma. Schematic overview of local drug-delivery strategies applied directly into the surgical resection cavity of glioblastoma. Approaches are grouped into direct infusion systems (e.g., convection-enhanced delivery catheters, Ommaya reservoirs) and biodegradable implantable systems (e.g., hydrogels, electrospun scaffolds, compressed polymer wafers). Other emerging strategies include implantable programmable microchips allowing controlled spatiotemporal release of therapeutics. Created with Biorender (

www.biorender.com).

3.6. Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapies

Recently, Immunotherapy and targeted therapies have emerged, aiming to specifically disrupt molecular abnormalities within GBM cells, potentially enhancing therapeutic effectiveness while reducing side effects [

29]. One promising approach is anti-angiogenic therapy, particularly using bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Although bevacizumab extends progression-free survival in patients with recurrent GBM, it has not significantly improved overall survival in newly diagnosed cases, suggesting limitations due to compensatory angiogenic mechanisms [

30,

31].

The targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) which is often amplified or mutated in GBM is one such important therapeutic approach. Although preclinical data strongly suggested that erlotinib, gefitinib, or cetuximab would be effective against HNSCC 2 – 4, clinical trials have only shown modest effects. This partial success may be due to molecular heterogeneity of GBM and existence of compensatory signaling pathways [

21,

32].

Integrins, primarily αvβ3 and αvβ5 are critical for GBM invasion and angiogenesis. The integrin inhibitor cilengitide, initially considered effective, failed to improve survival in Phase III clinical trials. This exhibits the difficulty translating preclinical successes to clinical efficacy [

31,

33].

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a critical driver of glioblastoma (GBM) progression and therapy resistance. Lately, efforts have been focused on modulating such microenvironment as a therapeutic approach to increase the efficacy of treatment and have focused mainly on tumor-associated macrophages, and stromal elements [

31,

34]. Immunotherapy approaches targeting immune checkpoints (PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4) have also been investigated but have generally been disappointing due to GBM’s profoundly immunosuppressive microenvironment [

35,

36]. Current research emphasizes combination therapies, including targeted agents with immunotherapies or conventional treatments, to circumvent resistance mechanisms [

32,

36]. Despite significant challenges such as the blood-brain barrier, molecular heterogeneity, and resistance, targeted therapies continue to be vigorously investigated. Innovative drug-delivery methods, personalized therapeutic strategies, and combination approaches represent future directions to potentially improve patient outcomes in GBM [

31,

36].

4. Future Prospects and Challenges

4.1. Potential Future Developments in CNS Drug Delivery Research

Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier has proven to be one of the most prominent challenges in the treatment of brain tumors, many trends in research have been surfacing concerning this issue.

Liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, non-polymeric micelles, lipoplex, dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles, polymeric micelles, nanotubes, silica nanoparticles, quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, and magnetic nanoparticles are examples of the various compositions of nanoparticles, which are solid colloidal particles of matter with sizes ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers [

37]. Nanotechnology is an essential tool when developing new systems for the efficient delivery of potential therapeutic and diagnostic compounds to specific areas of the brain, because they reduce the adverse side effects associated with non-specific drug distribution, increase drug concentration at the desired site of action, and, consequently, improve therapeutic effectiveness [

38]. Loading medications onto nanoparticles allows them to pass the blood-brain barrier without blocking its chemical composition. Nanoparticles’ physicochemical and biomimetic features determine their ability to traverse the BBB. Evaluating the chemical composition of nanoparticles is crucial for minimizing their toxicity when used in clinical settings. So far, evidence supports the notion of nanoparticle-assisted medication delivery [

37].

Another advancement is the use of exosomes in crossing the blood-brain barrier. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane-bound nanoscale bodies secreted by almost all types of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. EVs are further classified as ectosomes and exosomes, ectosomes bud directly from the plasma membrane into the extracellular matrix while exosomes form intraluminal bodies through double plasma membrane invagination from multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [

39]. Exosomes are capable of delivering both hydrophilic and hydrophobic medications, and their drug-carrying capability is exceptional. They are an excellent drug delivery vehicle for a variety of diseases, including brain disorders, due to their advantages in tumor homing ability, extended blood circulation half-life, excellent BBB traversal, lower toxicity, hypo-immunogenicity, and reflection of the “inheritance” from the parent cell and cellular affinity [

39]. In recent years, artificially created exosomes have emerged as superior to natural exosomes in terms of large-scale production, uniform isolation, drug encapsulation, stability, and quality assurance. Manufactured exosomes are regarded as potentially excellent carriers for chemical and biological therapies, as we can control the circulation time and selectivity [

40]. However, exosomes are not always beneficial, in fact they may contribute to cancer metastasis to the brain, cancer cells create a large number of exosomes, which help cancer cells migrate, invade, and metastasize via angiogenesis. Tumor-cell-derived exosomes can interact with vascular tissues, including the brain vasculature, making them more susceptible to angiogenic stimuli and metastasis. Furthermore, exosomes generated from cancer cells carry immunosuppressive proteins that inhibit immune system processes and encourage tumor growth [

40].

4.2. Anticipated Challenges and Hurdles in Translating Research into Clinical Applications

A study analyzing CNS drugs in clinical trials between 1990 and 2012 revealed that these drugs were 45% less likely to succeed in Phase III trials compared to non-CNS drugs. Additionally, 46% of CNS drugs failed because they did not show greater efficacy than a placebo[

41]. The primary objective of the Phase III “REGAL” trial, which aimed to demonstrate an extension in progression-free survival by comparing cediranib alone, cediranib combined with lomustine, and placebo in patients with recurrent glioblastoma (GBM), was not achieved [

42]. Rindopepimut, a drug targeting the EGFRvIII mutation, effectively increased patients’ progression-free survival to 10–15 months and overall survival to 22–26 months, compared to just 6 and 15 months, respectively, reported in previous studies [

43]. However, it did not increase overall survival in a bigger Phase III trial, since the control group performed better than the treatment group (20.0 months vs. 20.1 months) [

44]. Trials will continue despite this setback, highlighting the challenges involved in introducing novel treatments. A recent study showed that differences between the tumor microenvironment in in vitro and in vivo models create significant obstacles in developing new drugs for glioblastoma (GBM) using lab-grown models [

45]. Several critical limitations must be considered when evaluating a drug’s efficacy. The drug has to be delivered to the tumor effectively achieving therapeutic levels without getting away in normal tissue. For example, the clinical trial that evaluated lapatinib was unsuccessful due to an inadequate drug level in patients [

46]. Moreover, to develop drugs for CNS-alleviating diseases, it is crucial to cross the BBB (or blood–brain barrier) effectively with a balance of molecular size and lipid-solubility. Intratumoral injections may solve this problem, but it has critical shortcomings in that they are time consuming, not widely accepted by oncologists and trapping biosafety concerns.

A retrospective analysis of EGFR inhibitors offers some understanding why the latter did not pan out in clinical GBM trials. These agents were effective in the laboratory setting, but EGFR inhibitors, including erlotinib and gefitinib, have not led to better clinical response. This shortfall has been attributed to inadequate CNS accumulation: efflux pumps such as P-glycoprotein and ABCG2 actively expel the compounds from the brain parenchyma, preventing attainment of therapeutic levels [

47,

48].

In addition to pharmacokinetic hurdles, recent progress in the development of drugs for GBM has encountered formidable barriers. Low clinical trial accrual (in part by classifying GBM as an orphan disease) has limited the statistical confirmation of modest, yet clinically important improvements. Further difficulties involve ensuring appropriate definition of clinical endpoints, obtaining efficient patient stratification for prognostic factors and choosing a relevant control arm [

46].

Furthermore, the risk and cost of surgery make monitoring molecular features in brain tumors more difficult. It is therefore of utmost importance to establish non-imaging methods to evaluate drug efficacy, also because some therapies could decrease tumor growth and not its overall size [

13].

5. Conclusions

This paper discusses the possible employment of nanoparticles (NPs) as novel therapeutic solutions for a highly aggressive disease, glioblastoma, known to be extremely difficult to tackle despite different pathologies. Drug-loaded NPs were found to be able to selectively deliver drug into AD hallmark amyloid plaques. In the same way, nanoparticles stimulate drug penetration into brain tissue through the EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect and represent a major moving forward in treatment of glioblastoma. The efficacy of nanoparticles depends mainly on their physical characteristics and size, which can determine the capability of nanoparticle to penetrate biological barriers and exert intended therapeutic effect [

49].

Contrastingly, despite encouraging preclinical results, there is a rareness of clinical investigations of the potential for nanoparticle integration in radiation oncologic practice. The enormity of the challenge here comes because there are many different types of nanoparticles that have been considered in the research community and they can differ drastically, including mass (size), geometry (shape) and surface functionality. This diversity adds a level of complexity in interpreting their uptake mechanisms, the biological pathways for radiation sensitization, extracorporeal clearance and potential toxicologic attributes. Therefore, substantial in-depth preclinical research is required to discover the best nanoparticle formulations and dosing schedules suited for this clinical development. Despite encouraging preclinical data, several unresolved issues continue to obstruct clinical translation and limit real-world utility [

50].

To date, the major roadblocks have been keeping track of vital molecular pathways and the finding of novel drugs which are targeted. The introduction of molecular profiling and patient stratification techniques into routine clinical practice offers hope that future trials with rationally targeted therapies may demonstrate improved results. The development of novel treatments largely relies on appropriate identification of therapeutic targets, suitable drug candidates and dependable biomarkers for patient selection in early clinical studies [

51].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Frederic Harb; Methodology, Frederic Harb; Investigation, Nicole Al Fidawi, Cecile Z. Attieh, Lara Baghdadi, Chahine El Bekai, and Safaa Sayadi; Resources, Nicole Al Fidawi, Cecile Z. Attieh, Lara Baghdadi, Chahine El Bekai, and Safaa Sayadi; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Nicole Al Fidawi, Cecile Z. Attieh, Lara Baghdadi, Chahine El Bekai, and Safaa Sayadi; Writing – Review and Editing, Hilda E. Ghadieh, François Sahyoun, Ghassan Nabbout, Sami Azar, and Frederic Harb; Visualization, Nicole Al Fidawi, Cecile Z. Attieh, Lara Baghdadi, Chahine El Bekai, and Safaa Sayadi; Supervision and Project Administration, Frederic Harb.

Funding

No external funding was received for this study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interest information

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this work. No author has any financial or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the manuscript.

References

- Nahirney PC, Tremblay ME. Brain Ultrastructure: Putting the Pieces Together. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. 2021 Feb 18 [cited 2025 July 19];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.

- Miller, G. Is Pharma Running Out of Brainy Ideas? Science. 2010 July 30;329(5991):502–4.

- Gutkin A, Cohen ZR, Peer D. Harnessing nanomedicine for therapeutic intervention in glioblastoma. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016 Nov 1;13(11):1573–82.

- Urbańska K, Sokołowska J, Szmidt M, Sysa P. Review Glioblastoma multiforme – an overview. Współczesna Onkol. 2014;5:307–12.

- Thakkar JP, Dolecek TA, Horbinski C, Ostrom QT, Lightner DD, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Epidemiologic and Molecular Prognostic Review of Glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014 Oct 1;23(10):1985–96.

- Bastiancich C, Danhier P, Préat V, Danhier F. Anticancer drug-loaded hydrogels as drug delivery systems for the local treatment of glioblastoma. J Controlled Release. 2016 Dec;243:29–42.

- Janjua TI, Rewatkar P, Ahmed-Cox A, Saeed I, Mansfeld FM, Kulshreshtha R, et al. Frontiers in the treatment of glioblastoma: Past, present and emerging. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021 Apr;171:108–38.

- Arvanitis CD, Ferraro GB, Jain RK. The blood–brain barrier and blood–tumour barrier in brain tumours and metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020 Jan;20(1):26–41.

- Dhiman A, Rana D, Benival D, Garkhal K. Comprehensive insights into glioblastoma multiforme: drug delivery challenges and multimodal treatment strategies. Ther Deliv. 2025 Jan 2;16(1):87–115.

- Hersh AM, Alomari S, Tyler BM. Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advances in Nanoparticle Technology for Drug Delivery in Neuro-Oncology. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 9;23(8):4153.

- Du R, Wang C, Zhu L, Yang Y. Extracellular Vesicles as Delivery Vehicles for Therapeutic Nucleic Acids in Cancer Gene Therapy: Progress and Challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Oct 19;14(10):2236.

- Obrador E, Moreno-Murciano P, Oriol-Caballo M, López-Blanch R, Pineda B, Gutiérrez-Arroyo J, et al. Glioblastoma Therapy: Past, Present and Future. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Feb 21;25(5):2529.

- Shergalis A, Bankhead A, Luesakul U, Muangsin N, Neamati N. Current Challenges and Opportunities in Treating Glioblastoma. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 July;70(3):412–45.

- An Z, Aksoy O, Zheng T, Fan QW, Weiss WA. Epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma: signaling pathways and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2018 Mar;37(12):1561–75.

- Yasinjan F, Xing Y, Geng H, Guo R, Yang L, Liu Z, et al. Immunotherapy: a promising approach for glioma treatment. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2023 Sept 7 [cited 2025 July 20];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1255611/full.

- Ghaznavi H, Afzalipour R, Khoei S, Sargazi S, Shirvalilou S, Sheervalilou R. New insights into targeted therapy of glioblastoma using smart nanoparticles. Cancer Cell Int [Internet]. 2024 May 7 [cited 2025 July 20];24(1). Available from: https://cancerci.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12935-024-03331-3.

- Davanzo NN, Pellosi DS, Franchi LP, Tedesco AC. Light source is critical to induce glioblastoma cell death by photodynamic therapy using chloro-aluminiumphtalocyanine albumin-based nanoparticles. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2017 Sept;19:181–3.

- Kang JH, Desjardins A. Convection-enhanced delivery for high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol Pract. 2022 Jan 25;9(1):24–34.

- Faraji AH, Rajendran S, Jaquins-Gerstl AS, Hayes HJ, Richardson RM. Convection-Enhanced Delivery and Principles of Extracellular Transport in the Brain. World Neurosurg. 2021 July;151:163–71.

- Sperring CP, Argenziano MG, Savage WM, Teasley DE, Upadhyayula PS, Winans NJ, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of immunomodulatory therapy for high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncol Adv [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 July 19];5(1). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/noa/article/doi/10.1093/noajnl/vdad044/7134128.

- Lee J, Cho HR, Cha GD, Seo H, Lee S, Park CK, et al. Flexible, sticky, and biodegradable wireless device for drug delivery to brain tumors. Nat Commun. 2019 Nov 15;10(1):5205.

- Hauck M, Hellmold D, Kubelt C, Synowitz M, Adelung R, Schütt F, et al. Localized Drug Delivery Systems in High-Grade Glioma Therapy—From Construction to Application. Adv Ther. 2022 Aug;5(8):2200013.

- Cha GD, Jung S, Choi SH, Kim DH. Local Drug Delivery Strategies for Glioblastoma Treatment. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2022;10(3):151.

- Wang K, Chen Y, Ahn S, Zheng M, Landoni E, Dotti G, et al. GD2-specific CAR T cells encapsulated in an injectable hydrogel control retinoblastoma and preserve vision. Nat Cancer. 2020 Oct 12;1(10):990–7.

- Roberts JW, Powlovich L, Sheybani N, LeBlang S. Focused ultrasound for the treatment of glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2022 Apr;157(2):237–47.

- Bendix MB, Houston A, Forde PF, Brint E. Electrochemotherapy and immune interactions; A boost to the system? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022 Sept;48(9):1895–900.

- Tasu JP, Tougeron D, Rols MP. Irreversible electroporation and electrochemotherapy in oncology: State of the art. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2022 Nov;103(11):499–509.

- Jenkins EPW, Finch A, Gerigk M, Triantis IF, Watts C, Malliaras GG. Electrotherapies for Glioblastoma. Adv Sci [Internet]. 2021 Sept [cited 2025 July 19];8(18). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/advs.202100978.

- Chen SF, Kau M, Wang YC, Chen MH, Tung FI, Chen MH, et al. Synergistically Enhancing Immunotherapy Efficacy in Glioblastoma with Gold-Core Silica-Shell Nanoparticles and Radiation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023 Dec;Volume 18:7677–93.

- Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, et al. Bevacizumab plus Radiotherapy–Temozolomide for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014 Feb 20;370(8):709–22.

- Yaghi NK, Gilbert MR. Immunotherapeutic Approaches for Glioblastoma Treatment. Biomedicines. 2022 Feb 11;10(2):427.

- Shen Y, Thng DKH, Wong ALA, Toh TB. Mechanistic insights and the clinical prospects of targeted therapies for glioblastoma: a comprehensive review. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024 Apr 13;13(1):40.

- Stupp R, Hegi ME, Gorlia T, Erridge SC, Perry J, Hong YK, et al. Cilengitide combined with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CENTRIC EORTC 26071-22072 study): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014 Sept;15(10):1100–8.

- Quail DF, Joyce JA. The Microenvironmental Landscape of Brain Tumors. Cancer Cell. 2017 Mar;31(3):326–41.

- Filley AC, Henriquez M, Dey M. Recurrent glioma clinical trial, CheckMate-143: the game is not over yet. Oncotarget. 2017 Oct 31;8(53):91779–94.

- Medikonda R, Dunn G, Rahman M, Fecci P, Lim M. A review of glioblastoma immunotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2021 Jan;151(1):41–53.

- Achar A, Myers R, Ghosh C. Drug Delivery Challenges in Brain Disorders across the Blood–Brain Barrier: Novel Methods and Future Considerations for Improved Therapy. Biomedicines. 2021 Dec 4;9(12):1834.

- Pinheiro RGR, Coutinho AJ, Pinheiro M, Neves AR. Nanoparticles for Targeted Brain Drug Delivery: What Do We Know? Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Oct 28;22(21):11654.

- Rehman FU, Liu Y, Zheng M, Shi B. Exosomes based strategies for brain drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2023 Feb;293:121949.

- Abdelsalam M, Ahmed M, Osaid Z, Hamoudi R, Harati R. Insights into Exosome Transport through the Blood–Brain Barrier and the Potential Therapeutical Applications in Brain Diseases. Pharmaceuticals. 2023 Apr 10;16(4):571.

- Kesselheim AS, Hwang TJ, Franklin JM. Two decades of new drug development for central nervous system disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015 Dec;14(12):815–6.

- Batchelor TT, Mulholland P, Neyns B, Nabors LB, Campone M, Wick A, et al. Phase III Randomized Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Cediranib As Monotherapy, and in Combination With Lomustine, Versus Lomustine Alone in Patients With Recurrent Glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Sept 10;31(26):3212–8.

- Swartz AM, Li QJ, Sampson JH. Rindopepimut: A Promising Immunotherapeutic for the Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Immunotherapy. 2014 June;6(6):679–90.

- Weller M, Butowski N, Tran DD, Recht LD, Lim M, Hirte H, et al. Rindopepimut with temozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed, EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastoma (ACT IV): a randomised, double-blind, international phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Oct;18(10):1373–85.

- Miller TE, Liau BB, Wallace LC, Morton AR, Xie Q, Dixit D, et al. Transcription elongation factors represent in vivo cancer dependencies in glioblastoma. Nature. 2017 July;547(7663):355–9.

- Reardon DA, Galanis E, DeGroot JF, Cloughesy TF, Wefel JS, Lamborn KR, et al. Clinical trial end points for high-grade glioma: the evolving landscape. Neuro-Oncol. 2011 Mar 1;13(3):353–61.

- Agarwal S, Sane R, Gallardo JL, Ohlfest JR, Elmquist WF. Distribution of Gefitinib to the Brain Is Limited by P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2)-Mediated Active Efflux. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010 July;334(1):147–55.

- De Vries NA, Buckle T, Zhao J, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Van Tellingen O. Restricted brain penetration of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib due to the drug transporters P-gp and BCRP. Invest New Drugs. 2012 Apr;30(2):443–9.

- Anwar F, Al-Abbasi FA, Naqvi S, Sheikh RA, Alhayyani S, Asseri AH, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Nanomedicine in Management of Alzheimer’s Disease and Glioma. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023 May;Volume 18:2737–56.

- Rancoule C, Magné N, Vallard A, Guy JB, Rodriguez-Lafrasse C, Deutsch E, et al. Nanoparticles in radiation oncology: From bench-side to bedside. Cancer Lett. 2016 June;375(2):256–62.

- Touat M, Idbaih A, Sanson M, Ligon KL. Glioblastoma targeted therapy: updated approaches from recent biological insights. Ann Oncol. 2017 July;28(7):1457–72.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).