Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

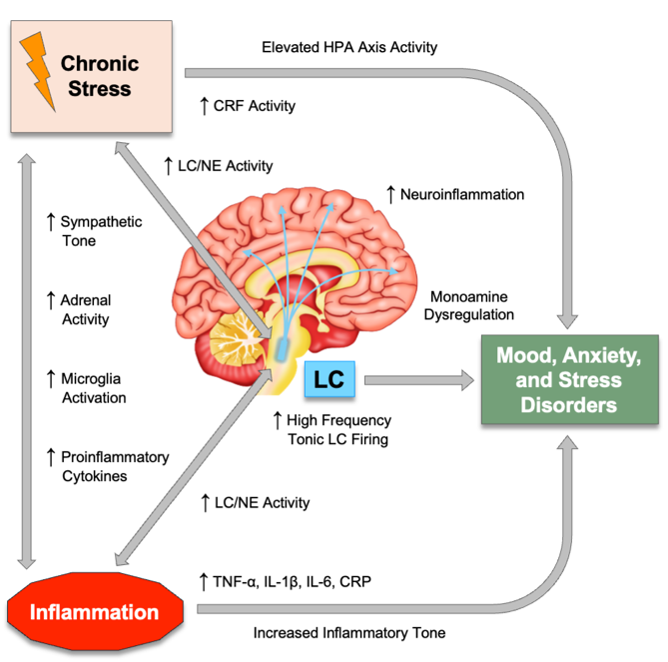

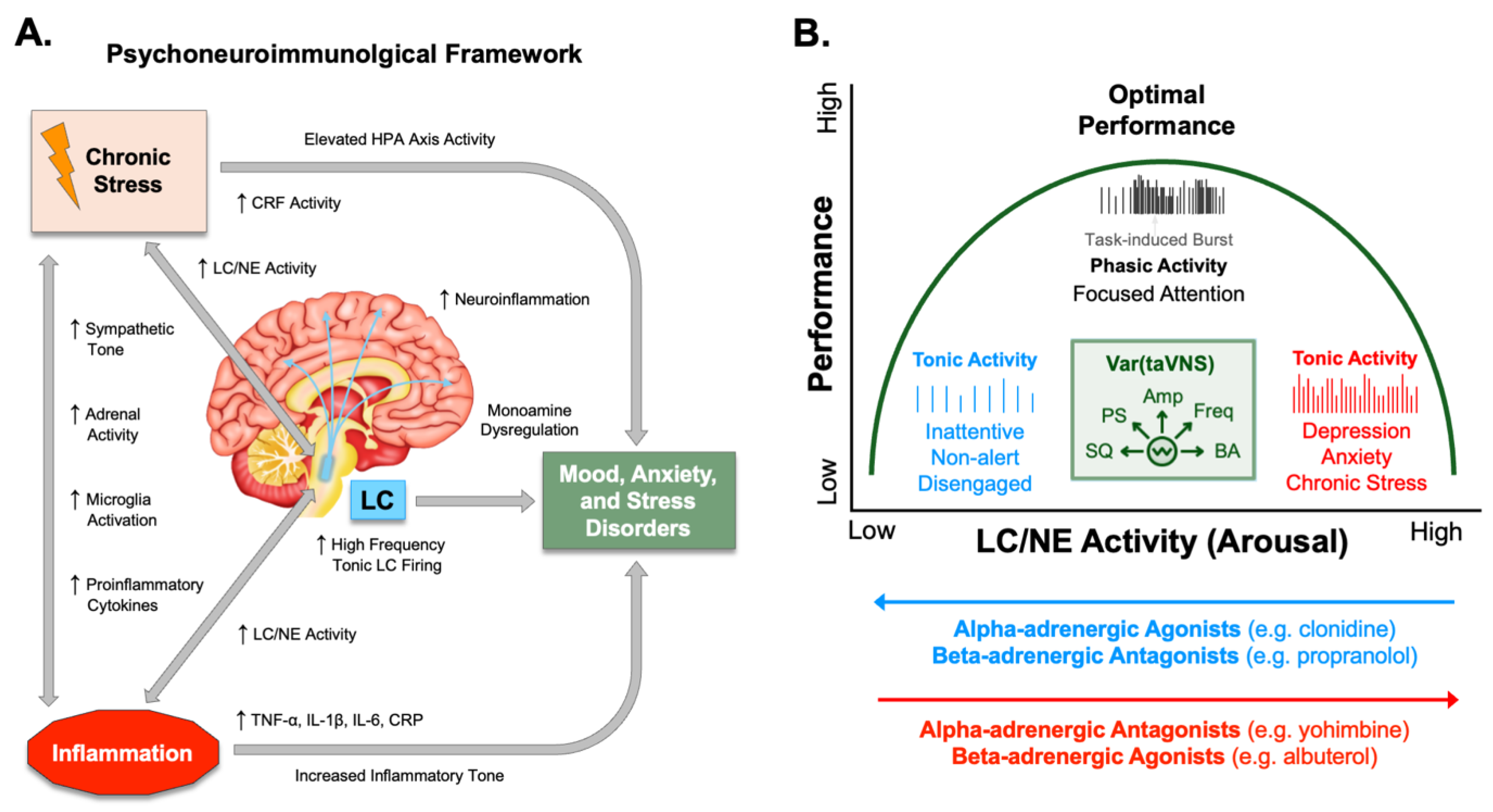

Psychophysiological Arousal and Noradrenergic Activity in Anxiety and Depression

Inflammatory Signatures of Anxiety, Stress, and Mood Disorders

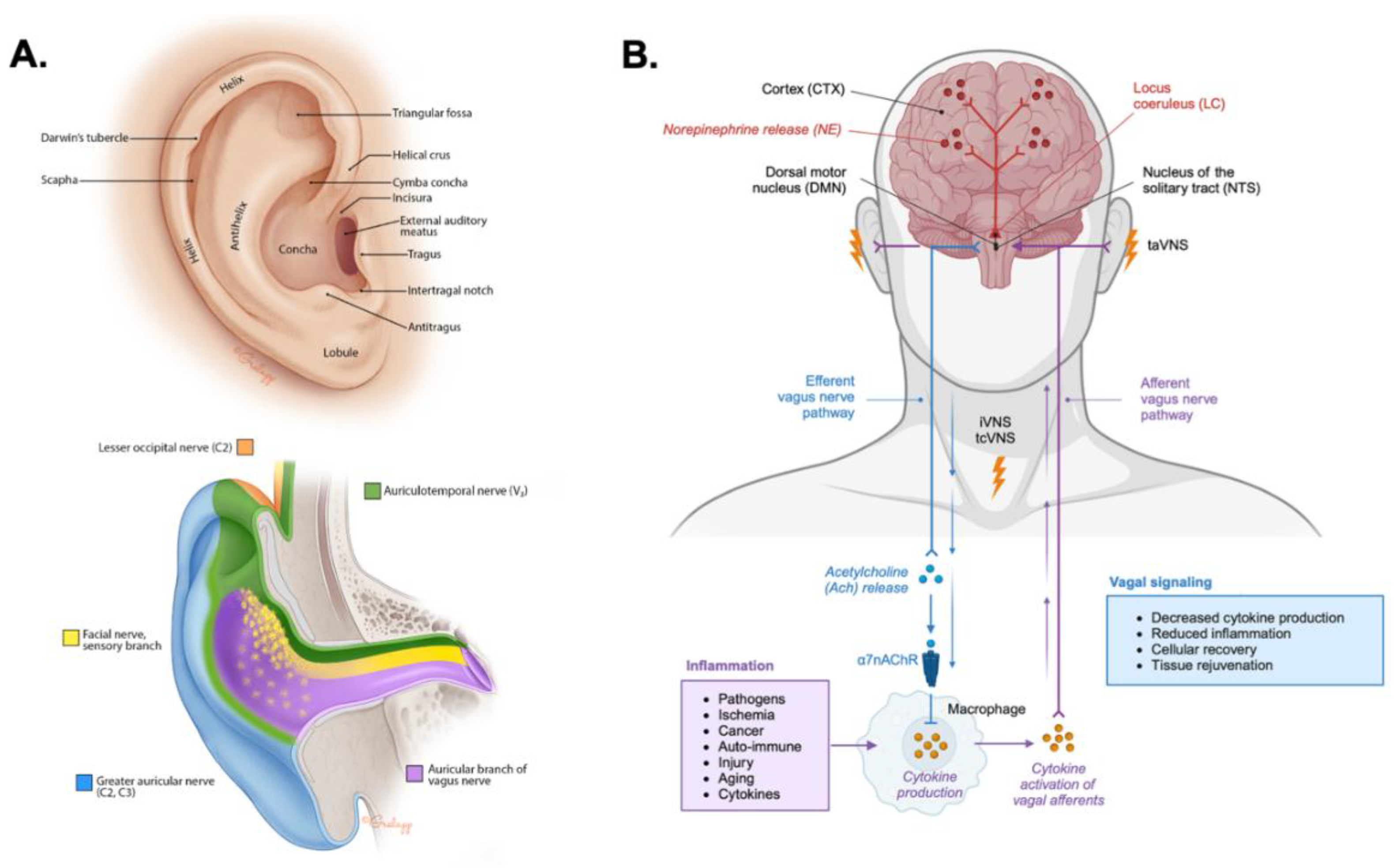

Anatomical Basis for taVNS

Ascending Modulation of Noradrenergic Signaling by taVNS

Modulation of the Descending Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway by taVNS

| Mechanistic Pathway | Neurobiological and Physiological Effects |

|---|---|

| Ascending Neuromodulation | Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) activates afferent vagal fibers from the external ear projecting to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). The NTS then modulates activity in the locus coeruleus (LC), leading to widespread release of norepinephrine (NE). This helps to stabilize mood and arousal, as well as enhance attention, cognitive control, and facilitates neuroplasticity related to learning and memory. |

| Descending Anti-Inflammatory Modulation | Afferent vagal activation triggers the efferent cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP). Activation of the CAP involves the release of acetylcholine (ACh), which binds to α7 nicotinic ACh receptors (α7nAChR) on peripheral immune cells like macrophages to inhibit the activation of NF-κB and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. |

Effects of taVNS on Autonomic Balance and Heart Rate Variability

Modulation of Stress, Cognition, and Emotion by taVNS

Clinical and Translational Efficacy of taVNS in Depression, Anxiety, and PTSD

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Disclosures

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

References

- Arias, D.; Saxena, S.; Verguet, S. Quantifying the global burden of mental disorders and their economic value. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C.; Buchweitz, C.; Caye, A.; Silvani, J.; Ameis, S.H.; Brunoni, A.R.; Cost, K.T.; Courtney, D.B.; Georgiades, K.; Merikangas, K.R.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability From Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence: Evidence From the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, G.M.D. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Huang, W.; Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; Zhao, C.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Dynamic changes and future trend predictions of the global burden of anxiety disorders: Analysis of 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2021 and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechter, K. The Challenge of Assessing Mild Neuroinflammation in Severe Mental Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.; Katzman, M.A. Examining the role of neuroinflammation in major depression. Psychiatry Research 2015, 229, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassamal, S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: An overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, S.; Bartlett, E.A.; Zanderigo, F.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Burke, A.; Mintz, A.; Schmidt, M.; Hauser, E.; Huang, Y.-y.; Melhem, N.; et al. Neuroinflammation, Stress-Related Suicidal Ideation, and Negative Mood in Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, M.R. Sleep and inflammation: Partners in sickness and in health. Nature Reviews Immunology 2019, 19, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.H.; Cervenka, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Kreisl, W.C.; Henter, I.D.; Innis, R.B. Neuroinflammation in psychiatric disorders: PET imaging and promising new targets. The Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sălcudean, A.; Bodo, C.-R.; Popovici, R.-A.; Cozma, M.-M.; Păcurar, M.; Crăciun, R.-E.; Crisan, A.-I.; Enatescu, V.-R.; Marinescu, I.; Cimpian, D.-M.; et al. Neuroinflammation—A Crucial Factor in the Pathophysiology of Depression—A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radtke, F.A.; Chapman, G.; Hall, J.; Syed, Y.A. Modulating Neuroinflammation to Treat Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Biomed Res Int 2017, 2017, 5071786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Cohen, J.D. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: Adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci 2005, 28, 403–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poe, G.R.; Foote, S.; Eschenko, O.; Johansen, J.P.; Bouret, S.; Aston-Jones, G.; Harley, C.W.; Manahan-Vaughan, D.; Weinshenker, D.; Valentino, R.; et al. Locus coeruleus: A new look at the blue spot. Nat Rev Neurosci 2020, 21, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, D.; Tops, M.; Bakker, A.B. The Neuroscience of the Flow State: Involvement of the Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine System. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 645498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.S.; McCall, J.G.; Charney, D.S.; Murrough, J.W. The role of the locus coeruleus in the generation of pathological anxiety. Brain Neurosci Adv 2020, 4, 2398212820930321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, B.A.S. The Locus Coeruleus: Anatomy, Physiology, and Stress-Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Eur J Neurosci 2025, 61, e70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, K.J.; Nemeroff, C.B. Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1219–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, M.; Hao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Translational Psychiatry 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, D.R.; Rapaport, M.H.; Miller, B.J. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: Comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1696–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ren, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, J. Microglia in depression: An overview of microglia in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, D.; Fernandes, A. Neuroinflammation and Depression: Microglia Activation, Extracellular Microvesicles and microRNA Dysregulation. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2015, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yirmiya, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Reshef, R. Depression as a Microglial Disease. Trends in Neurosciences 2015, 38, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, E.; Wilson, A.A.; Mizrahi, R.; Rusjan, P.M.; Miler, L.; Rajkowska, G.; Suridjan, I.; Kennedy, J.L.; Rekkas, P.V.; Houle, S.; et al. Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J. Auricular bioelectronic devices for health, medicine, and human-computer interfaces. Frontiers in Electronics 2025, 6, 1503425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Blanco, C.; Tyler, W.J. The vagus nerve: A cornerstone for mental health and performance optimization in recreation and elite sports. Frontiers in Psychology 2025, 16, 1639866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.F.; Albusoda, A.; Farmer, A.D.; Aziz, Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Journal of Anatomy 2020, 236, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.Y.; Marduy, A.; de Melo, P.S.; Gianlorenco, A.C.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.-J.; Fregni, F. Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 22055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbin, M.A.; Lafe, C.W.; Simpson, T.W.; Wittenberg, G.F.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Weber, D.J. Electrical stimulation of the external ear acutely activates noradrenergic mechanisms in humans. Brain Stimul 2021, 14, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangos, E.; Ellrich, J.; Komisaruk, B.R. Non-invasive Access to the Vagus Nerve Central Projections via Electrical Stimulation of the External Ear: fMRI Evidence in Humans. Brain Stimul 2015, 8, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I.; Johns, M.A.; Pandža, N.B.; Calloway, R.C.; Karuzis, V.P.; Kuchinsky, S.E. Three Hundred Hertz Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (taVNS) Impacts Pupil Size Non-Linearly as a Function of Intensity. Psychophysiology 2025, 62, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, O.; Fahoum, F.; Nir, Y. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Humans Induces Pupil Dilation and Attenuates Alpha Oscillations. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2021, 41, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A. Collateral benefits of studying the vagus nerve in bioelectronic medicine. Bioelectron Med 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—Linking immunity and metabolism. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2012, 8, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. Bioelectronic medicine: Preclinical insights and clinical advances. Neuron 2022, 110, 3627–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun 2005, 19, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, A.; Brines, M.; Chavan, S.S. Control of inflammation using non-invasive neuromodulation: Past, present and promise. International Immunology 2021, 34, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Jones, G.; Rajkowski, J.; Cohen, J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biological Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bockstaele, E.J.; Colago, E.E.; Valentino, R.J. Corticotropin-releasing factor-containing axon terminals synapse onto catecholamine dendrites and may presynaptically modulate other afferents in the rostral pole of the nucleus locus coeruleus in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 1996, 364, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bockstaele, E.J.; Colago, E.E.; Valentino, R.J. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: Substrate for the co-ordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrinol 1998, 10, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devilbiss, D.M.; Waterhouse, B.D.; Berridge, C.W.; Valentino, R. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Acting at the Locus Coeruleus Disrupts Thalamic and Cortical Sensory-Evoked Responses. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 2020–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koob, G.F. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biological Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulenger, J.P.; Uhde, T.W. Biological peripheral correlates of anxiety. Encephale 1982, 8, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.K.; Bannon, M.J. Stress-induced c-fos expression in the rat locus coeruleus is dependent on neurokinin 1 receptor activation. Neuroscience 1999, 94, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.E.; Yizhar, O.; Chikahisa, S.; Nguyen, H.; Adamantidis, A.; Nishino, S.; Deisseroth, K.; de Lecea, L. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nature Neuroscience 2010, 13, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, J.G.; Al-Hasani, R.; Siuda, E.R.; Hong, D.Y.; Norris, A.J.; Ford, C.P.; Bruchas, M.R. CRH Engagement of the Locus Coeruleus Noradrenergic System Mediates Stress-Induced Anxiety. Neuron 2015, 87, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, J.G.; Siuda, E.R.; Bhatti, D.L.; Lawson, L.A.; McElligott, Z.A.; Stuber, G.D.; Bruchas, M.R. Locus coeruleus to basolateral amygdala noradrenergic projections promote anxiety-like behavior. Elife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, S.L.; Bloom, F.E.; Aston-Jones, G. Nucleus locus ceruleus: New evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol Rev 1983, 63, 844–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. Forebrain norepinephrine: Role in controlled information processing in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992, 7, 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, T.W. Arousal systems and attentional processes. Biol Psychol 1997, 45, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowinski, J.; Axelrod, J. Inhibition of uptake of tritiated-noradrenaline in the intact rat brain by imipramine and structurally related compounds. Nature 1964, 204, 1318–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M.R.; Schwartz, T.L. Alpha-2 receptor agonists for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Drugs Context 2015, 4, 212286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, M.; Cao, J.L.; Han, M.H. The Role of Beta-Adrenergic Receptors in Depression and Resilience. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maletic, V.; Eramo, A.; Gwin, K.; Offord, S.J.; Duffy, R.A. The Role of Norepinephrine and Its α-Adrenergic Receptors in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Front Psychiatry 2017, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohleb, E.S.; Hanke, M.L.; Corona, A.W.; Powell, N.D.; Stiner, L.M.; Bailey, M.T.; Nelson, R.J.; Godbout, J.P.; Sheridan, J.F. β-Adrenergic receptor antagonism prevents anxiety-like behavior and microglial reactivity induced by repeated social defeat. J Neurosci 2011, 31, 6277–6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Norton, J.; Carrière, I.; Ritchie, K.; Chaudieu, I.; Ryan, J.; Ancelin, M.-L. Preliminary evidence for a role of the adrenergic nervous system in generalized anxiety disorder. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 42676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoi, K.; Sugimoto, N. The Brainstem Noradrenergic Systems in Stress, Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 2010, 22, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.K. Peripheral adrenergic activity contributes to anxiety. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, D.S.; Heninger, G.R.; Breier, A. Noradrenergic Function in Panic Anxiety: Effects of Yohimbine in Healthy Subjects and Patients With Agoraphobia and Panic Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 1984, 41, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, D.S.; Woods, S.W.; Heninger, G.R. Noradrenergic function in generalized anxiety disorder: Effects of yohimbine in healthy subjects and patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research 1989, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesse, R.M.; Cameron, O.G.; Curtis, G.C.; McCann, D.S.; Huber-Smith, M.J. Adrenergic function in patients with panic anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1984, 41, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, T.W.; Stein, M.B.; Vittone, B.J.; Siever, L.J.; Boulenger, J.-P.; Klein, E.; Mellman, T.A. Behavioral and Physiologic Effects of Short-term and Long-term Administration of Clonidine in Panic Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 1989, 46, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, J.D.; Liebowitz, M.R.; Gorman, J.M.; Fyer, A.J.; Dillon, D.J.; Campeas, R.B.; Davies, S.O.; Martinez, J.; Klein, D.F. Noradrenergic function in panic disorder effects of intravenous clonidine pretreatment on lactate induced panic. Biological Psychiatry 1992, 31, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sevilla, J.A.; Zis, A.P.; Hollingsworth, P.J.; Greden, J.F.; Smith, C.B. Platelet α2-Adrenergic Receptors in Major Depressive Disorder: Binding of Tritiated Clonidine Before and After Tricyclic Antidepressant Drug Treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 1981, 38, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier Meana, J.; Barturen, F.; Garcia-Sevilla, J.A. <em>α</em><sub>2</sub>-Adrenoceptors in the brain of suicide victims: Increased receptor density associated with major depression. Biological Psychiatry 1992, 31, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordway, G.A.; Schenk, J.; Stockmeier, C.A.; May, W.; Klimek, V. Elevated agonist binding to α2-adrenoceptors in the locus coeruleus in major depression. Biological Psychiatry 2003, 53, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottingham, C.; Wang, Q. α2 adrenergic receptor dysregulation in depressive disorders: Implications for the neurobiology of depression and antidepressant therapy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2012, 36, 2214–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, N.L.; McDonald, M.P.; Limbird, L.E. The α<sub>2A</sub>-Adrenergic Receptor Plays a Protective Role in Mouse Behavioral Models of Depression and Anxiety. The Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uys, M.M.; Shahid, M.; Harvey, B.H. Therapeutic Potential of Selectively Targeting the α2C-Adrenoceptor in Cognition, Depression, and Schizophrenia—New Developments and Future Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2017, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extein, I.; Tallman, J.; Smith, C.C.; Goodwin, F.K. Changes in lymphocyte beta-adrenergic receptors in depression and mania. Psychiatry Research 1979, 1, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Brown, R.P.; Halper, J.P.; Sweeney, J.A.; Kocsis, J.H.; Stokes, P.E.; Bilezikian, J.P. Reduced Sensitivity of Lymphocyte Beta-Adrenergic Receptors in Patients with Endogenous Depression and Psychomotor Agitation. New England Journal of Medicine 1985, 313, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.N.; Sudershan, P.; Davis, J.M. BETA ADRENERGIC RECEPTOR FUNCTION IN DEPRESSION AND THE EFFECT OF ANTIDEPRESSANT DRUGS. Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica 1985, 56, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.L.; Charney, D.S.; Woods, S.W.; Heninger, G.R.; Tallman, J. Lymphocyte β-adrenergic receptor binding in panic disorder. Psychopharmacology 1988, 94, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurel Gorman, A.; Dunn, A.J. β-adrenergic receptors are involved in stress-related behavioral changes. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1993, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M.E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol 2007, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïd-Sadier, N.; Ojcius, D.M. Alarmins, inflammasomes and immunity. Biomed J 2012, 35, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.K.; Kavelaars, A.; Heijnen, C.J.; Dantzer, R. Neuroinflammation and Comorbidity of Pain and Depression. Pharmacological Reviews 2014, 66, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O'Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, E.; Jaafari, N.; Hashemian, F. On inflammatory hypothesis of depression: What is the role of IL-6 in the middle of the chaos? Journal of Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasik, J.; Schiweck, C.; Drexhage, H.A. A Sticky Situation: The Link Between Peripheral Inflammation, Neuroinflammation, and Severe Mental Illness. Biological Psychiatry 2023, 93, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, W.E.; Shanahan, L.; Worthman, C.; Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Generalized anxiety and C-reactive protein levels: A prospective, longitudinal analysis. Psychol Med 2012, 42, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Niedzwiedz, C.L. The association of anxiety and stress-related disorders with C-reactive protein (CRP) within UK Biobank. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity Health 2022, 19, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-d.; Chang, Y.-h.; Xie, X.-t.; Wang, X.-y.; Ma, H.-y.; Liu, M.-c.; Zhang, H.-m. PET Imaging Unveils Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms in Psychiatric Disorders: From Microglial Activation to Therapeutic Innovation. Molecular Neurobiology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.J.; Cassidy, F.; Naftolowitz, D.; Tatham, N.E.; Wilson, W.H.; Iranmanesh, A.; Liu, P.Y.; Veldhuis, J.D. Pathophysiology of hypercortisolism in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2007, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.-d.; Rizak, J.; Feng, X.-l.; Yang, S.-c.; Lü, L.-b.; Pan, L.; Yin, Y.; Hu, X.-t. Prolonged secretion of cortisol as a possible mechanism underlying stress and depressive behaviour. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 30187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, C.F.; Nemeroff, C.B. Hypercortisolemia and depression. Psychosom Med 2005, 67 (Suppl 1), S26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; McVey Neufeld, K.-A. Gut–brain axis: How the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends in Neurosciences 2013, 36, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; et al. Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression: Unveiling the Relationships and Management Options. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, M.; Qi, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; et al. A diet high in sugar and fat influences neurotransmitter metabolism and then affects brain function by altering the gut microbiota. Translational Psychiatry 2021, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwin Thanarajah, S.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Lee, J.; Winter, N.R.; Stein, F.; Lippert, R.N.; Hanssen, R.; Schiweck, C.; Fehse, L.; Bloemendaal, M.; et al. Soft Drink Consumption and Depression Mediated by Gut Microbiome Alterations. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Association between dietary sugar intake and depression in US adults: A cross-sectional study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2018. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, J.; Mayer, D.E.; Chen, S.; Mayer, E.A. Role of diet and its effects on the gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of mental disorders. Translational Psychiatry 2022, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackler, R.K. Ear Surgery Illustrated: A Comprehensive Atlas of Otologic Microsurgical Techniques, 1st edition ed.; Thieme: 2019; p. 1297.

- Khurana, R.K.; Watabiki, S.; Hebel, J.R.; Toro, R.; Nelson, E. Cold face test in the assessment of trigeminal-brainstem-vagal function in humans. Ann Neurol 1980, 7, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapi, D.; Scuri, R.; Colantuoni, A. Trigeminal Cardiac Reflex and Cerebral Blood Flow Regulation. Front Neurosci 2016, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwly, C.; Golanov, E.; Chowdhury, T.; Erne, P.; Schaller, B. Trigeminal cardiac reflex: New thinking model about the definition based on a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, W.J.; Boasso, A.M.; Mortimore, H.M.; Silva, R.S.; Charlesworth, J.D.; Marlin, M.A.; Aebersold, K.; Aven, L.; Wetmore, D.Z.; Pal, S.K. Transdermal neuromodulation of noradrenergic activity suppresses psychophysiological and biochemical stress responses in humans. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 13865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, S.P.; Raab, M.; Backschat, S.; Smith, D.J.C.; Javelle, F.; Laborde, S. The diving response and cardiac vagal activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneton, W.M.; Gan, Q. The Mammalian Diving Response: Inroads to Its Neural Control. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whayne, T.F., Jr.; Killip, T. , 3rd. Simulated diving in man: Comparison of facial stimuli and response in arrhythmia. J Appl Physiol 1967, 22, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Verma, S.; Vishwakarma, S.K. Anatomic basis of Arnold's ear-cough reflex. Surg Radiol Anat 1986, 8, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekdemir, I.; Aslan, A.; Elhan, A. A clinico-anatomic study of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve and Arnold's ear-cough reflex. Surg Radiol Anat 1998, 20, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kiyokawa, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Okada, R.; Maehara, T.; Akita, K. Origin, course and distribution of the nerves to the posterosuperior wall of the external acoustic meatus. Anat Sci Int 2014, 89, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuker, E.T.; Filler, T.J. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin Anat 2002, 15, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakunina, N.; Kim, S.S.; Nam, E.-C. Optimization of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Using Functional MRI. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2017, 20, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Park, J.; Wilson, G.; Liu, B.; Kong, J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at 1 Hz modulates locus coeruleus activity and resting state functional connectivity in patients with migraine: An fMRI study. NeuroImage: Clinical 2019, 24, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Priovoulos, N.; Prokopiou, P.C.; Verhey, F.R.; Poser, B.A.; Ivanov, D.; Sclocco, R.; Napadow, V.; Jacobs, H.I. Locus coeruleus fMRI response to transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation is coupled to changes in salivary alpha amylase. Brain Stimul 2025, 18, 1205–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.-H.; Nahas, Z.; Lomarev, M.; Denslow, S.; Lorberbaum, J.P.; Bohning, D.E.; George, M.S. A review of functional neuroimaging studies of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). Journal of Psychiatric Research 2003, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, A.M.; Dyve, S.; Jakobsen, S.; Alstrup, A.K.O.; Gjedde, A.; Doudet, D.J. Acute Vagal Nerve Stimulation Lowers α2 Adrenoceptor Availability: Possible Mechanism of Therapeutic Action. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 2015, 8, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-T.; Gaulding, S.J.; Dancel, C.L.E.; Thorn, C.A. Local activation of α2 adrenergic receptors is required for vagus nerve stimulation induced motor cortical plasticity. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 21645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neifert, C.; Danaphongse, T.; Pillai, S.; Razack, A.; Kilgard, M.; Hays, S. Beta-receptor blockades during high-intensity vagus nerve stimulation enable enhanced cortical plasticity, and provide insight into the mechanism of VNS-mediated plasticity. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 2025, 18, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Hu, L. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Facilitates Cortical Arousal and Alertness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.-K.; Jia, B.-H.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.-Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhou, Z.-G.; Bi, Y.-Z.; Wu, M.-Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.-L.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Modulates the Prefrontal Cortex in Chronic Insomnia Patients: fMRI Study in the First Session. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13, 827749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Cho, M.J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in disorders of consciousness: A mini-narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e31808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Chen, C.; Falahpour, M.; MacNiven, K.H.; Heit, G.; Sharma, V.; Alataris, K.; Liu, T.T. Effects of Sub-threshold Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Cingulate Cortex and Insula Resting-state Functional Connectivity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuser, M.P.; Teckentrup, V.; Kühnel, A.; Hallschmid, M.; Walter, M.; Kroemer, N.B. Vagus nerve stimulation boosts the drive to work for rewards. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgewell, C.; Heaton, K.J.; Hildebrandt, A.; Couse, J.; Leeder, T.; Neumeier, W.H. The effects of transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation on cognition in healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychology 2021, 35, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ma, Y.; Du, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C.; Luo, Y.; Chen, L.; Gao, D.; Li, X.; Xu, K.; et al. Immediate Modulation of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 923783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeska, C.; Klepzig, K.; Hamm, A.O.; Weymar, M. Ready for translation: Non-invasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits psychophysiological indices of stimulus-specific fear and facilitates responding to repeated exposure in phobic individuals. Translational Psychiatry 2025, 15, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, J.-K.; Zhong, G.-L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.-N.; Wang, L.; Li, S.-Y.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Zhao, B.; et al. Prolonged Longitudinal Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Effect on Striatal Functional Connectivity in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Sciences 2022, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colzato, L.; Beste, C. A literature review on the neurophysiological underpinnings and cognitive effects of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation: Challenges and future directions. Journal of Neurophysiology 2020, 123, 1739–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, R.; Ventura-Bort, C.; Hamm, A.; Weymar, M. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) enhances conflict-triggered adjustment of cognitive control. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 2018, 18, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.J.; O'Neal, A.G.; Cohen, R.A.; Lamb, D.G.; Porges, E.C.; Bottari, S.A.; Ho, B.; Trifilio, E.; DeKosky, S.T.; Heilman, K.M.; et al. The Effects of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Functional Connectivity Within Semantic and Hippocampal Networks in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Fang, J.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Rong, P. Treating Depression with Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2018, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Zhang, G.-Z.; Wang, X.-X.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Woelfer, M.; Walter, M.; Wang, L. Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, P.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Fang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Vangel, M.; Sun, S.; et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: A nonrandomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2016, 195, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.; Akan, A.; Mueller, M.R. Transcutaneous Stimulation of Auricular Branch of the Vagus Nerve Attenuates the Acute Inflammatory Response After Lung Lobectomy. World Journal of Surgery 2020, 44, 3167–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, F.I.; Souza, P.H.L.; Uehara, L.; Ritti-Dias, R.M.; Oliveira da Silva, G.; Segheto, W.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Fregni, F.; Corrêa, J.C.F. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Improves Inflammation but Does Not Interfere with Cardiac Modulation and Clinical Symptoms of Individuals with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Life 2022, 12, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, X.; Wu, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces cytokine production in sepsis: An open double-blind, sham-controlled, pilot study. Brain Stimulation 2023, 16, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguenard, A.L.; Tan, G.; Rivet, D.J.; Gao, F.; Johnson, G.W.; Adamek, M.; Coxon, A.T.; Kummer, T.T.; Osbun, J.W.; Vellimana, A.K.; et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation for mitigation of inflammation and vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage: A single-institution randomized controlled trial. J Neurosurg 2025, 142, 1720–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurido-Soto, O.J.; Tan, G.; Nielsen, S.S.; Huguenard, A.L.; Donovan, K.; Xu, I.; Giles, J.; Dhar, R.; Adeoye, O.; Lee, J.-M.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Reduces Inflammatory Biomarkers and May Improve Outcomes after Large Vessel Occlusion Strokes: Results of the Randomized Clinical Trial NUVISTA. medRxiv 2025, 2025.2003.2006.25323500. [CrossRef]

- Hesampour, F.; Tshikudi, D.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Ghia, J.E. Exploring the efficacy of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) in modulating local and systemic inflammation in experimental models of colitis. Bioelectron Med 2024, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xin, C.; Wang, Y.; Rong, P. Anti-neuroinflammation effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation against depression-like behaviors via hypothalamic α7nAchR/JAK2/STAT3/NF-κB pathway in rats exposed to chronic unpredictable mild stress. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023, 29, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, S.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Wei, Q.; Min, L.; Rong, P. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation ameliorates adolescent depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors via hippocampus glycolysis and inflammation response. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024, 30, e14614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Rong, P.; Wang, J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation alleviates inflammation-induced depression by modulating peripheral-central inflammatory cytokines and the NF-κB pathway in rats. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 16, 1536056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D.; Gurel, N.Z.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Shandhi, M.H.; Rapaport, M.H.; Nye, J.A.; Pearce, B.D.; Vaccarino, V.; Shah, A.J.; Park, J.; et al. Application of Noninvasive Vagal Nerve Stimulation to Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2020, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on HRV in healthy young people. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.A.; Mary, D.A.; Witte, K.K.; Greenwood, J.P.; Deuchars, S.A.; Deuchars, J. Non-invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Healthy Humans Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity. Brain Stimulation 2014, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, H.; Edama, M.; Kawanabe, Y.; Hirabayashi, R.; Sekikne, C.; Akuzawa, H.; Ishigaki, T.; Otsuru, N.; Saito, K.; Kojima, S.; et al. Effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at left cymba concha on experimental pain as assessed with the nociceptive withdrawal reflex, and correlation with parasympathetic activity. Eur J Neurosci 2024, 59, 2826–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuberos Paredes, E.; Goyes, D.; Mak, S.; Yardimian, R.; Ortiz, N.; McLaren, A.; Stauss, H.M. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits mental stress-induced cortisol release-Potential implications for inflammatory conditions. Physiol Rep 2025, 13, e70251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, S.; Ottaviani, C.; Verkuil, B.; Kappen, M.; Baeken, C.; Vanderhasselt, M.-A. Effects of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation on cognitive and autonomic correlates of perseverative cognition. Psychophysiology 2023, 60, e14250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roy, B.; Martin-Krumm, C.; Gille, A.; Jacob, S.; Vigier, C.; Laborde, S.; Claverie, D.; Besnard, S.; Trousselard, M. Evaluation of taVNS for extreme environments: An exploration study of health benefits and stress operationality. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1286919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, W.J.; Wyckoff, S.; Hearn, T.; Hool, N. The Safety and Efficacy of Transdermal Auricular Vagal Nerve Stimulation Earbud Electrodes for Modulating Autonomic Arousal, Attention, Sensory Gating, and Cortical Brain Plasticity in Humans. bioRxiv 2019, 732529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferstl, M.; Teckentrup, V.; Lin, W.M.; Kräutlein, F.; Kühnel, A.; Klaus, J.; Walter, M.; Kroemer, N.B. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation boosts mood recovery after effort exertion. Psychological Medicine 2022, 52, 3029–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, U.; Knops, L.; Laborde, S.; Klatt, S.; Raab, M. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation May Enhance Only Specific Aspects of the Core Executive Functions. A Randomized Crossover Trial. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2020, 14, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlaja, M.; Failla, L.; Peräkylä, J.; Hartikainen, K.M. Reduced Frontal Nogo-N2 With Uncompromised Response Inhibition During Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation—More Efficient Cognitive Control? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2020, 14, 561780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A.; Fischer, R.; Borges, U.; Laborde, S.; Achtzehn, S.; Liepelt, R. The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on cognitive control in multitasking. Neuropsychologia 2023, 187, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena-Chamorro, P.; Espinoza-Palavicino, T.; Barramuño-Medina, M.; Romero-Arias, T.; Gálvez-García, G. Impact of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on cognitive flexibility as a function of task complexity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2025, 19, 1569472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, X.; Ding, F.; Zhang, R.; Becker, B.; Kendrick, K.M.; Zhao, W. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation enhanced emotional inhibitory control via increasing intrinsic prefrontal couplings. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2024, 24, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zheng, C.; Jin, M.; Dong, Q.; Zhu, L.; Tian, F. Exploring the Alleviating Effects of taVNS on Negative Emotions: An EEG Study. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Bort, C.; Wirkner, J.; Wendt, J.; Hamm, A.O.; Weymar, M. Establishment of Emotional Memories Is Mediated by Vagal Nerve Activation: Evidence from Noninvasive taVNS. The Journal of Neuroscience 2021, 41, 7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, R.; Özden, A.V.; Nişancı, O.S.; Yıldız Kızkın, Z.; Demirkıran, B.C. The effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on visual memory performance and fatigue. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 2023, 69, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2001, 42, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porges, S.W. Cardiac vagal tone: A neurophysiological mechanism that evolved in mammals to dampen threat reactions and promote sociality. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Schiweck, C.; Jamalambadi, H.; Meyer, K.; Brandt, E.; Schneider, M.; Aichholzer, M.; Qubad, M.; Bouzouina, A.; Schillo, S.; et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation improves emotional processing. Journal of Affective Disorders 2025, 372, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-J.; Lee, Y.-S.; Hong, K.H.; Choi, H.; Song, J.-J.; Hwang, H.-J. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on stress regulation: An EEG and questionnaire study. Frontiers in Digital Health 2025, 7, 1593614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Croce, P.; Lanzone, J.; Boscarino, M.; Zappasodi, F.; Tombini, M.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Assenza, G. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Modulates EEG Microstates and Delta Activity in Healthy Subjects. Brain Sciences 2020, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, P.; Wang, R.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Ge, S. The Neural Basis of the Effect of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Emotion Regulation Related Brain Regions: An rs-fMRI Study. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 4076–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, J.; Sun, J.; Guo, C.; Du, Z.; Chen, L.; Luo, Y.; Gao, D.; Hong, Y.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve immediate stimulation treatment for treatment-resistant depression: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13, 931838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-P.; Liao, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Qu, M.; Lv, X.-Y.; Fang, J.-L.; Liu, C.-H. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation modulating the brain topological architecture of functional network in major depressive disorder: An fMRI study. Brain Sciences 2024, 14, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; O'Leary, G.H.; Thompson, S.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Comprehensive Review of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Depression. Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society 2022, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, B.W.; Austelle, C.W. The Future Is Noninvasive: A Brief Review of the Evolution and Clinical Utility of Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing) 2022, 20, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, J.R.; LaMacchia, Z.M.; Alderete, J.F.; Maestas, A.; Nguyen, K.; O’Hara, R.B. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Efficacy, Applications, and Challenges in Mood Disorders and Autonomic Regulation—A Narrative Review. Military Medicine 2025, usaf063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, M.; Antosik-Wójcińska, A.; Dominiak, M.; Święcicki, Ł. Use of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) in the treatment of drug-resistant depression - a pilot study, presentation of five clinical cases. Psychiatria Polska 2021, 55, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Rong, P.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Hou, X.; Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation vs Citalopram for Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Trial. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2022, 25, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, E.; Nowak, M.; Kiess, O.; Biermann, T.; Bayerlein, K.; Kornhuber, J.; Kraus, T. Auricular transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in depressed patients: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996) 2013, 120, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deligiannidis, K.M.; Robakis, T.; Homitsky, S.C.; Ibroci, E.; King, B.; Jacob, S.; Coppola, D.; Raines, S.; Alataris, K. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder with peripartum onset: A multicenter, open-label, controlled proof-of-concept clinical trial (DELOS-1). Journal of Affective Disorders 2022, 316, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austelle, C.W.; Cox, S.S.; Connolly, D.J.; Baker Vogel, B.; Peng, X.; Wills, K.; Sutton, F.; Tucker, K.B.; Ashley, E.; Manett, A.; et al. Accelerated Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Inpatient Depression and Anxiety: The iWAVE Open Label Pilot Trial. Neuromodulation 2025, 28, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Sabers, A.; Martiny, K. Transcutaneous Vagal Nerve Stimulation in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Feasibility Study. Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society 2022, 25, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeska, C.; Richter, J.; Wendt, J.; Weymar, M.; Hamm, A.O. Promoting long-term inhibition of human fear responses by non-invasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation during extinction training. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, S.A.; Lamb, D.G.; Porges, E.C.; Murphy, A.J.; Tran, A.B.; Ferri, R.; Jaffee, M.S.; Davila, M.I.; Hartmann, S.; Baumert, M.; et al. Preliminary evidence of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation effects on sleep in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Sleep Research 2024, 33, e13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, D.F.; Engineer, N.D.; McIntyre, C.K. Rapid remission of conditioned fear expression with extinction training paired with vagus nerve stimulation. Biol Psychiatry 2013, 73, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurel, N.Z.; Wittbrodt, M.T.; Jung, H.; Shandhi, M.M.H.; Driggers, E.G.; Ladd, S.L.; Huang, M.; Ko, Y.A.; Shallenberger, L.; Beckwith, J.; et al. Transcutaneous cervical vagal nerve stimulation reduces sympathetic responses to stress in posttraumatic stress disorder: A double-blind, randomized, sham controlled trial. Neurobiol Stress 2020, 13, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, R.R.; Robertson, N.M.; McIntyre, C.K.; Rennaker, R.L.; Hays, S.A.; Kilgard, M.P. Vagus nerve stimulation enhances fear extinction as an inverted-U function of stimulation intensity. Experimental Neurology 2021, 341, 113718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.D. Vagal Nerve Stimulation for Patients With Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders and Addictions. Journal of Health Service Psychology 2023, 49, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.; Badran, B.; Huffman, S.; Dancy, M.; Kautz, S.; George, M. At-home telemedicine controlled taVNS twice daily for 4 weeks reduces long COVID symptoms of anxiety and fatigue. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation 2021, 14, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.A.; Brites, R.; Fraião, G.; Pereira, G.; Fernandes, H.; de Brito, J.A.A.; Pereira Generoso, L.; Maziero Capello, M.G.; Pereira, G.S.; Scoz, R.D.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation modulates masseter muscle activity, pain perception, and anxiety levels in university students: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1422312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shan, A.-d.; Wan, C.-h.; Cao, X.-y.; Yuan, Y.-s.; Ye, S.-y.; Gao, M.-x.; Gao, L.-z.; Tong, Q.; Gan, C.-t.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation improves anxiety symptoms and cortical activity during verbal fluency task in Parkinson's disease with anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, 361, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Abathsagayam, K.; Suganthirababu, P.; Alagesan, J.; Vishnuram, S.; Vasanthi, R.K. Effect of vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on anxiety and sleep disturbances among elderly health care workers in the post COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2024, 78, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.; Hunter, S.; Cottrell, H.; Dar, R.; Takahashi, N.; Ferguson, B.J.; Valter, Y.; Porges, E.; Datta, A.; Beversdorf, D.Q. Remotely supervised at-home delivery of taVNS for autism spectrum disorder: Feasibility and initial efficacy. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1238328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferstl, M.; Kühnel, A.; Klaus, J.; Lin, W.M.; Kroemer, N.B. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation conditions increased invigoration and wanting in depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2024, 132, 152488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.M.; Van der Does, W.; Thayer, J.F.; Brosschot, J.F.; Verkuil, B. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation reduces spontaneous but not induced negative thought intrusions in high worriers. Biological Psychology 2019, 142, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Zhai, Y.; Wu, Q.-Q.; Huang, W.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Y.-H.; Xu, L.-Y. Effect of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Protracted Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms in Male Alcohol-Dependent Patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12, 678594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Zhan, S.; Rong, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, A. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Could Improve the Effective Rate on the Quality of Sleep in the Treatment of Primary Insomnia: A Randomized Control Trial. Brain Sciences 2022, 12, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.-N.; Liu, X.-H.; Cai, W.-S. Preventive noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation reduces insufficient sleep-induced depression by improving the autonomic nervous system. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 173, 116344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottari, S.A.; Trifilio, E.R.; Rohl, B.; Wu, S.S.; Miller-Sellers, D.; Waldorff, I.; Hadigal, S.; Jaffee, M.S.; Ferri, R.; Lamb, D.G.; et al. Optimizing transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation parameters for sleep and autonomic function in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder with or without mild traumatic brain injury. Sleep 2025, 48, zsaf152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, T.; Hösl, K.; Kiess, O.; Schanze, A.; Kornhuber, J.; Forster, C. BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. Journal of Neural Transmission 2007, 114, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.-X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, G.-L.; Rong, P.-J.; Fang, J.-L. The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on treatment-resistant depression monitored by resting-state fMRI and MRS: The first case report. Brain Stimulation 2019, 12, 377–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Rong, P.; Hong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Park, J.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates amygdala functional connectivity in patients with depression. J Affect Disord 2016, 205, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-K.; Li, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Xiao, X.; Hou, X.-B.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.-N.; Zhai, W.-H.; Fang, J.-L. Mapping the modulating effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on voxel-based analyses in patients with first-episode major depressive disorder: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2023, 45, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).