1. Introduction

Embedded systems are specialized computing systems that perform dedicated functions within larger mechanical or electrical systems. Their pervasive presence in critical infrastructures, medical devices, automotive electronics, and Internet of Things (IoT) networks demands stringent security measures. The rising sophistication of cyberattacks targeting these systems calls for robust mechanisms to ensure their reliable and secure operation from the moment they power on. Secure bootloaders play a pivotal role in this landscape by safeguarding the integrity of firmware and thwarting unauthorized modifications. This introduction provides an overview of embedded system security, emphasizing the need for secure boot mechanisms and the challenges associated with maintaining firmware integrity.

1.1. Overview of Embedded System Security

Embedded system security encompasses a variety of strategies and technologies designed to protect embedded devices from cyber threats and attacks. Unlike general-purpose computing devices, embedded systems often operate in constrained environments with limited resources and are frequently deployed in physically accessible or remote locations. Consequently, the security paradigm for these systems must integrate hardware and software protections, including cryptographic techniques, secure coding practices, hardware trust anchors, and runtime protections. The goal is to defend against threats such as malware insertion, unauthorized firmware alterations, denial-of-service attacks, and data breaches. Maintaining confidentiality, integrity, and availability in embedded systems ensures their correct and trustworthy operation throughout their lifecycle.

1.2. Need for Secure Boot Mechanisms

One of the cornerstone components in embedded system security is the secure boot process. A secure boot mechanism guarantees that the device starts only with verified and trusted software, preventing the execution of manipulated or malicious firmware. This is of paramount importance because the firmware controls the hardware and software behavior of embedded devices, and any compromise at this level can lead to complete system failure or exploitation. Secure boot mechanisms establish a chain of trust that roots from immutable hardware elements, verifying each successive code component before execution. By doing so, they protect against persistent threats, enable safe firmware updates, and ensure compliance with regulatory security standards, which are increasingly demanded in critical and commercial embedded applications.

1.3. Challenges in Firmware Integrity Protection

Despite the critical importance of secure boot mechanisms, maintaining firmware integrity presents several challenges. Embedded systems often have limited processing power and memory, which constrains the choice of cryptographic algorithms and security protocols. Additionally, attackers may attempt sophisticated firmware tampering techniques such as injection of malicious code, replay attacks, or rollback to vulnerable firmware versions. Ensuring the secure storage of cryptographic keys in a tamper-resistant manner and defending against physical attacks poses further difficulties. Secure boot implementations must also manage the complexity of diverse hardware platforms and development frameworks, all while minimizing performance overhead and ensuring a seamless user experience. Balancing these factors requires careful design and integration of cryptographic validation mechanisms within the secure bootloader framework.

2. Literature Survey on Secure Bootloaders in Embedded Systems

The development and implementation of secure boot mechanisms in embedded systems have been extensively researched and diversified based on target application domains, hardware capabilities, and security requirements. This survey reviews key methodologies and approaches published in academic and industry literature, focusing on their advantages, limitations, and specific cryptographic validation methods used to protect firmware integrity.

Table 1.

Comparison Table of Methodologies and Articles.

Table 1.

Comparison Table of Methodologies and Articles.

| Reference / Source |

Bootloader Security Approach |

Cryptographic Mechanism |

Device/Application Focus |

Strengths |

Limitations |

| Article A: Promwad (2025) |

Hardware-rooted secure boot with chained verification |

ECDSA digital signatures |

General embedded devices |

Strong hardware root of trust, layered verification |

Higher resource consumption on low-end MCUs |

| Article B: Analog Devices (2025) |

Secure boot combined with secure firmware update |

RSA signatures with hash validation |

Industrial control systems |

Supports secure firmware update lifecycle |

Larger signature size, impacts boot time |

| Article C: Beningo (2021) |

Lightweight secure bootloader for resource-constrained devices |

HMAC for firmware integrity |

IoT devices, sensor nodes |

Low resource overhead, simple implementation |

Limited to symmetric key, potential key exposure |

| Article D: Foundries.io (2024) |

Open-source secure boot with hardware TPM integration |

ECC-based digital signatures |

Automotive and IoT systems |

TPM integration enhances hardware security |

Dependency on TPM availability |

| Article E: TheEmbeddedKit (2025) |

Secure boot with rollback protection via monotonic counters |

SHA-256 hashing and version counters |

Consumer electronics |

Effective rollback attack prevention |

Requires secure storage for counters |

Promwad (2025) emphasizes a hardware-rooted chain of trust with ECDSA digital signatures ensuring each boot stage is verified cryptographically. Its layered approach suits complex embedded systems but may strain low-resource devices.

Analog Devices (2025) integrates secure boot with secure firmware updates, using RSA signatures for authenticity checks throughout firmware lifecycle, tailored for industrial systems requiring robust update security.

Beningo (2021) proposes a lightweight secure bootloader using HMAC, ideal for IoT devices with limited processing power, though it uses symmetric keys which pose key management challenges.

Foundries.io (2024) outlines an open-source approach utilizing hardware TPMs for key storage and ECC signatures, balancing strong cryptographic assurance with accessible hardware security modules mainly for automotive and IoT.

TheEmbeddedKit (2025) focuses on rollback protection, implementing monotonic counters alongside hashing to prevent downgrade attacks, a critical feature for consumer electronics where firmware version control is essential.

This survey collectively illustrates various techniques and trade-offs in secure bootloader designs for embedded systems, highlighting how cryptographic validation methods adapt to different constraints and security goals.

3. Fundamentals of Secure Bootloaders

Secure bootloaders serve as a critical security foundation in embedded systems by ensuring that the firmware executing on a device is both authentic and unmodified. At their core, secure bootloaders use cryptographic validation mechanisms, typically digital signatures and hashes, to verify the integrity and provenance of the firmware before allowing the device to operate. This fundamental approach prevents the execution of malicious or tampered code that could compromise device functionality or leak sensitive information. Secure bootloaders anchor device trust from the earliest code executed, forming an unbroken chain of trust rooted in immutable hardware elements such as eFuses, ROM, or Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs). This establishes a verifiable boundary between a device’s hardware and software, critical for any security-sensitive embedded application.

3.1. Bootloader Architecture in Embedded Devices

The architecture of bootloaders in embedded systems is designed to progressively initialize hardware and load firmware components with increasing privilege and trust. Typically, the boot process begins with a hardware-anchored root of trust executing immutable code stored in read-only memory (Boot ROM). This initial stage verifies the signature of the next-stage bootloader using cryptographic keys securely stored in hardware. Subsequent bootloader stages perform further verification and load the operating system kernel or application firmware, each step confirming signatures and hashes of the loaded code. This layered architecture ensures that only validated, trusted firmware executes throughout system startup. Additionally, bootloaders may incorporate functionalities such as rollback protection, secure firmware update management, and dynamic key management to enhance security over the device’s operational lifecycle.

3.2. Role of Bootloaders in the Startup Chain of Trust

Bootloaders form a vital link in the embedded system’s startup chain of trust, a hierarchical sequence of verification steps that guarantees software authenticity at every layer. Starting from the root of trust embedded in hardware, each boot component cryptographically verifies the next before handing over control. This creates an unbroken chain ensuring that no unauthorized or altered code runs during or after boot. The bootloader executes critical trust decisions early, affirming firmware integrity and preventing compromised images from gaining execution control. By enforcing this chain of trust, bootloaders facilitate secure firmware updates, protect against persistent threats, and provide a foundation upon which other security features, such as secure communication or cryptographic key provisioning, can safely rely.

3.3. Typical Vulnerabilities in Traditional Bootloaders

Traditional or non-secure bootloaders often rely on weaker validation such as checksums and do not verify cryptographic signatures, leaving them vulnerable to several critical security risks. Attackers can exploit these bootloaders by injecting malicious firmware, conducting reverse engineering, or performing replay and rollback attacks. Without a robust verification mechanism, unauthorized firmware can run freely, leading to system compromise, data leakage, or device bricking. Furthermore, traditional bootloaders may lack secure key storage, allowing key extraction or tampering. They also often do not enforce version control to prevent rollback to older, vulnerable firmware versions. These vulnerabilities underscore the importance of designing secure bootloaders with strong cryptographic safeguards and hardware-rooted trust models to defend embedded systems effectively.

4. Cryptographic Foundations for Secure Boot

Secure boot relies fundamentally on cryptographic principles to ensure that embedded devices boot only trustworthy, untampered firmware.

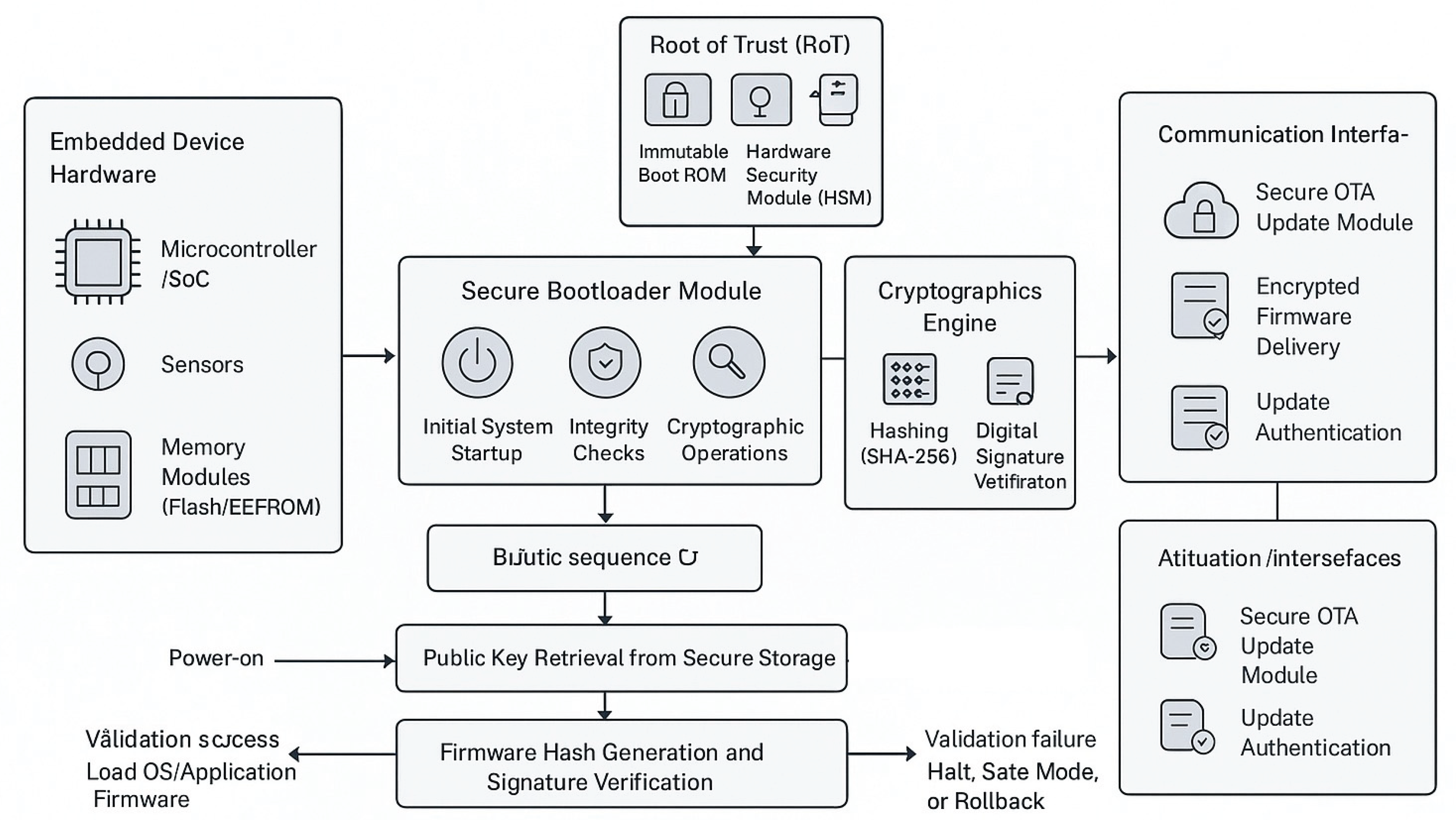

Figure 1.

Cryptographic Secure Bootloader Architecture for Embedded System Integrity Assurance.

Figure 1.

Cryptographic Secure Bootloader Architecture for Embedded System Integrity Assurance.

This cryptographic foundation combines both symmetric and asymmetric techniques, leveraging digital signatures and hash functions for validation. Key generation, storage, and management constitute critical components to maintain the security of these cryptographic operations throughout the device lifecycle. Together, these elements enable secure bootloaders to establish and uphold an unbroken chain of trust beginning at immutable hardware roots.

4.1. Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Cryptographic Techniques

Symmetric cryptography uses a single shared secret key for both encryption and decryption, resulting in efficient computation with low resource overhead. However, its use in secure bootloaders is limited by key distribution and management challenges, especially in devices vulnerable to physical access attacks. Asymmetric cryptography, more commonly used in secure boot, employs a private-public key pair; the private key signs the firmware image securely offline, while the public key embedded in the device verifies the signature during boot. This separation of keys enhances security by ensuring that private keys never reside on the device, thereby mitigating risks of key exposure. Algorithms commonly used include RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), with ECC favored for embedded systems due to its smaller key sizes and higher efficiency.

4.2. Digital Signatures and Hash Functions

Digital signatures form the cornerstone of cryptographic verification in secure bootloaders. Firmware images are hashed using cryptographic hash functions such as SHA-256 or SHA-512, producing a fixed-size digest representing the firmware content. This digest is then signed using the private key to generate a digital signature. During boot, the bootloader recomputes the firmware hash and uses the stored public key to verify the signature. A successful verification confirms both the integrity (unchanged firmware) and authenticity (from trusted source) of the firmware. This two-step validation process prevents unauthorized code execution, ensuring only firmware signed by trusted authorities is allowed to run.

4.3. Key Generation, Storage, and Management Strategies

The security of a secure boot process is heavily dependent on robust key management. Private keys used for signing firmware must be generated and stored securely offline, often in hardware security modules or secure key vaults. Correspondingly, public keys or their hashes are embedded in device hardware as root of trust elements, commonly stored in immutable memory structures such as eFuses, One-Time Programmable (OTP) memory, or Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs). To prevent key compromise, secure bootloaders also implement techniques including key revocation, key rotation, and secure key provisioning during manufacturing. Some systems leverage hardware protections like secure elements or Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) to isolate keys and cryptographic operations from software attacks, balancing security with the resource constraints typical in embedded devices.

5. Secure Bootloader Workflow and Trust Establishm

The secure bootloader workflow is designed to initiate the device startup process by establishing a foundational trust environment where only authenticated firmware is allowed to run. This process is anchored in a hardware root of trust, which holds immutable cryptographic keys and initiates the verification of firmware images. When the device is powered on, the bootloader begins by hashing the firmware image

using a cryptographic hash function

, producing a digest

. It then verifies a digital signature

associated with the firmware image, which is generated using the private key

of the signer, by checking it with the corresponding public key

stored securely in the hardware. Mathematically, signature verification can be expressed as:

where

is a boolean indicating the success or failure of verification. Only if

does the bootloader proceed to execute the firmware, thereby ensuring trust establishment at the initial stage of device operation.

5.1. Verification of Firmware Authenticity

Firmware authenticity is confirmed by digital signature verification which guarantees that the firmware originated from a trusted source. The firmware producer signs the firmware hash

with their private key

, creating the signature

. On the device, the secure bootloader recalculates the hash

and applies the public key

to validate the signature

:

If the decrypted signature matches the computed hash , the firmware authenticity is verified. This process prevents the execution of firmware that has been forged or maliciously altered.

5.2. Integrity Validation Using Cryptographic Hashes

Integrity validation ensures the firmware has not been modified since it was signed. The cryptographic hash function

possesses properties such as collision resistance and preimage resistance that guarantee even small changes in firmware produce a vastly different hash value. Integrity checking involves computing

of the loaded firmware and matching it against the trusted hash embedded within or validated via signature. Any discrepancy signifies corruption or tampering, prompting the bootloader to halt or enter recovery operations. The collision-resistant property of

implies for any distinct

:

This property is crucial for the effectiveness of firmware integrity protection.

5.3. Ensuring Non-Repudiation and Secure Updates

Non-repudiation ensures that the entity that signed the firmware cannot deny their signature, enforced through secure cryptographic signatures. Secure bootloaders enable secure firmware updates by verifying updated images before execution. Incorporating version control and rollback protection mechanisms prevents attackers from loading older compromised firmware. This is commonly managed via a version number

or monotonic counter stored securely:

Only firmware images with a version number exceeding the current version are accepted, preventing rollback attacks. These secure update mechanisms must be integrated with cryptographic validations to maintain device trustworthiness throughout its operational life.

5.4. .Multi-Stage Bootloader Security Models

Many embedded systems employ multi-stage bootloaders to incrementally verify various components. The first stage bootloader, anchored in hardware root of trust, verifies the second-stage bootloader’s signature and integrity. Each subsequent stage authenticates the next, propagating the chain of trust until the operating system or main application is reached. Mathematically, for stages

, stage

verifies:

where

is the firmware at stage

,

is its signature, and

is the public key from the previous stage. This hierarchical model improves security granularity and compartmentalizes trust decisions, making it more resilient against attacks targeting individual boot stages.

In essence, secure bootloader workflows combine cryptographic hashing, digital signatures, and rigorous verification procedures to establish a robust chain of trust and maintain firmware authenticity, integrity, and secure update capability throughout embedded system startup.

6. Firmware Protection Against Tampering

Protecting firmware against tampering is critical to maintaining the security and functionality of embedded systems. Firmware tampering involves unauthorized modifications that can introduce malicious code or disrupt normal operation. Secure bootloaders use a combination of cryptographic validation methods, including digital signatures and hash verification, to ensure that only authorized firmware versions execute. These protections ensure that any modification during transmission, storage, or execution is detected immediately, preventing attackers from compromising the device integrity. The immutability of firmware can be further enforced using hardware-based protections such as secure memory regions or fused bits that guard cryptographic keys and firmware content.

6.1. Attack Vectors Targeting Bootloaders and Firmware

Bootloaders and firmware are frequent targets for attackers due to their critical role in the device startup and operation. Common attack vectors include firmware injection attacks where malicious code is inserted into the firmware image, replay attacks that involve loading previous vulnerable firmware versions, and fault injection attacks aimed at bypassing verification processes. Physical tampering, side-channel attacks to extract cryptographic keys, and exploitation of software vulnerabilities in the bootloader also present significant threats. Failure to address these vulnerabilities can lead to unauthorized control, data breaches, or device bricking.

6.2. Anti-Rollback Mechanisms

Anti-rollback mechanisms are designed to prevent attackers from downgrading firmware to older, vulnerable versions that might have known security flaws. This is typically achieved by maintaining a monotonic version counter

stored securely in non-volatile memory:

Before accepting a firmware update, the secure bootloader verifies that the update’s version number is strictly greater than the currently installed version. This mechanism ensures only firmware with newer or equal versions are accepted, effectively blocking rollback attacks. Secure storage of the version counter is crucial to prevent attackers from resetting it to bypass this protection.

6.3. Secure Firmware Update Protocols

Secure firmware update protocols combine cryptographic verification and secure communication methods to guarantee that firmware updates are authentic and transmitted securely. Protocols often include signing the firmware image with private keys, secure key exchange methods to protect transmission, and integrity checks with cryptographic hashes. Additionally, these protocols support atomic updates where the device can revert to a known good state if the update process is interrupted, preventing bricking. Secure update processes also incorporate rollback protection and may include encryption of firmware payloads to protect confidentiality.

6.4. Runtime Protection and Continuous Integrity Checks

Beyond secure boot, runtime protection mechanisms are essential for continuously verifying the firmware’s integrity during device operation. These mechanisms detect unauthorized modifications or code injections that occur after the boot process. Techniques include periodic re-computation and verification of firmware hashes, memory protection units (MPUs) that restrict access to code sections, and anomaly detection systems that signal unexpected behavior. Continuous integrity checks fortify the system’s trustworthiness by enabling early detection and response to potential compromises during runtime, ensuring the embedded system remains secure throughout its lifecycle.

Together, these layers of protection from cryptographic validation at boot to runtime integrity verification form a comprehensive defense against tampering and attacks on embedded system firmware.

7. Hardware-Assisted Security Enhancements

In embedded systems, hardware-assisted security enhancements provide foundational trust and robust protection against firmware tampering and key compromise. These technologies leverage dedicated secure hardware components to isolate cryptographic operations and key storage from the general device environment, reducing exposure to software-based attacks and physical tampering.

7.1. Trusted Platform Modules (TPM) in Embedded Devices

Trusted Platform Modules (TPM) are specialized secure chips designed to create, store, and manage cryptographic keys securely and to provide hardware-rooted security functions. TPMs generate keys inside a tamper-resistant environment, ensuring private keys never leave the module. They support cryptographic operations such as digital signing, encryption, and attestation, enabling secure boot processes by establishing a hardware root of trust. TPMs also provide secure storage for firmware measurements and platform configuration, facilitating integrity verification throughout device operation. Their standardization by the Trusted Computing Group (TCG) makes TPM widely adoptable and interoperable in embedded security implementations.

7.2. Hardware Security Modules (HSM)

Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) are dedicated physical devices or components designed for high-assurance cryptographic key management and processing. They offer tamper-resistant environments where keys are generated, stored, and used internally, preventing key extraction even if the larger system is compromised. HSMs perform essential cryptographic functions such as key generation, digital signing, and encryption within isolated secure boundaries. Their stringent physical and logical security features include tamper detection, tamper response (e.g., zeroization of keys), and certified compliance (such as FIPS 140-2). In embedded systems, HSMs facilitate secure firmware provisioning, cryptographic operations during secure boot, and runtime protections, thus elevating overall system security.

7.3. ARM TrustZone and Secure Execution Environments

ARM TrustZone technology provides a hardware-based security extension in ARM processors that partitions a system into two worlds: the secure world and the non-secure world. The secure world runs trusted software, including secure bootloaders and security services, isolated from the non-secure world that executes normal applications. This isolation protects cryptographic keys and sensitive operations from compromise by malware or faults in the non-secure environment. TrustZone enables secure storage of cryptographic materials, secure interrupt handling, and enforcement of access control policies. By segregating security-critical code execution, TrustZone strengthens the integrity of the boot process and continuous protection of sensitive firmware components.

7.4. Use of PUFs (Physically Unclonable Functions) for Key Security

Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) exploit inherent manufacturing variations in integrated circuits to produce unique, device-specific responses that can serve as hardware fingerprints. PUFs generate cryptographic keys on-demand rather than storing them in memory, significantly reducing risk of key extraction or duplication. In secure boot and embedded security, PUFs enable secure key derivation and device authentication without the need for non-volatile key storage. This property enhances resistance against physical attacks such as invasive probing or side-channel analysis. When integrated with secure bootloaders, PUFs provide a resilient hardware root of trust and underpin cryptographic key generation tightly bound to the physical device.

8. Industrial Implementations of Secure Bootloader...

8.1. Secure Boot in Automotive ECUs

In automotive embedded systems, Electronic Control Units (ECUs) require secure bootloaders to ensure firmware integrity and protect against unauthorized modifications. A notable case is the development of an ISO 21434-compliant secure bootloader for automotive ECUs which included AES-128 encryption, Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA), and CRC-32 for data integrity verification. The solution supported both CAN and LIN communication protocols for ECU flashing and integrated tightly with Hardware Security Modules (HSM) provided on microcontrollers. It validated digital signatures for every firmware flashing attempt, safeguarding vehicle systems such as powertrain, infotainment, and motor control modules. Tools like Vector CANoe and Vflash were used for validation, while MISRA C-2012 coding standards ensured compliance and safety.

8.2. IoT Devices with Cryptographically Verified Boot

In IoT applications, secure boot mechanisms employ cryptographically verified boot processes to maintain device trustworthiness in constrained environments. Solutions like wolfBoot enable retrofitting existing legacy bootloaders incrementally by embedding signature verification routines. Firmware is authenticated using ECC or RSA signatures with SHA-256 hashes stored in tamper-resistant hardware such as TPMs, which prevent execution of unauthorized or revoked firmware. This approach ensures continuous security for remote IoT devices vulnerable to physical access and cyberattacks, providing features such as secure boot, firmware signing, and rollback prevention while maintaining compatibility with existing communication protocols like CAN.

8.3. Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Examples

In industrial control systems, secure bootloaders contribute to operational reliability by enforcing firmware authenticity and integrity as part of critical infrastructure protection. Industrial implementations integrate secure boot with cryptographic modules synchronized with hardware roots of trust and secure update mechanisms compliant with industry standards. Multi-stage bootloaders are common, where each stage verifies the next, ensuring an unbroken chain of trust from power-on through application loading. These implementations often incorporate hardware security modules and secure execution environments such as ARM TrustZone to isolate security-critical operations and enforce continuous integrity checks in the control environment.

8.4. Security Standards and Certifications

Security standards and certifications frame the development and deployment of secure bootloaders in embedded systems. ISO/IEC standards such as ISO 21434 specifically target automotive cybersecurity requirements, mandating secure boot with cryptographic validation and rigorous testing protocols. NIST guidelines provide detailed frameworks for cryptographic key management and firmware update security. The MISRA C coding standards ensure software safety and robustness, especially in automotive and industrial domains, by enforcing strict coding practices to limit vulnerabilities. Compliance with these standards ensures secure boot solutions meet regulatory requirements, safety integrity levels, and industry best practices, facilitating trustworthiness across diverse embedded system applications.

9. Performance Considerations and Optimization in ...

9.1. Balancing Security and Boot Time

Secure bootloaders must balance robust security against system boot time, as extensive cryptographic verification can introduce latency. Typically, the bootloader performs signature verification and cryptographic hash computations during startup, which increases boot duration. Studies show that software-only secure boot implementations add approximately 4–16% additional boot time, with hardware-assisted cryptographic modules increasing this overhead to around 36% depending on device capabilities and algorithms used. Efficient algorithm selection—such as preferring ECC over RSA due to smaller key sizes and faster calculations—and staged verification can optimize boot time without compromising security.

9.2. Lightweight Cryptography for Low-Power Devices

Embedded devices with stringent power and processing constraints benefit from lightweight cryptographic algorithms specifically designed for efficiency and reduced computational burden. Algorithms such as Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) and streamlined hash functions (e.g., SHA-256) provide strong security with lower resource consumption compared to traditional RSA or SHA-1. The choice of algorithms is critical to support fast signature verification and integrity checks within limited CPU cycles and memory footprints, preserving device responsiveness and extending battery life.

9.3. Memory and Processing Constraints in Embedded Platforms

Memory and processing limitations in embedded platforms pose challenges for implementing secure bootloaders. Limited RAM and flash memory restrict the size of cryptographic libraries, firmware images, and temporary buffers used during verification. Slow or absent hardware accelerators for cryptography further elongate validation phases. Developers often accommodate these constraints by modular bootloader design, leveraging hardware security modules (HSMs) or Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) for cryptographic offloading, and optimizing code for minimal memory footprint. Additionally, ensuring the bootloader fits within read-only memory regions enhances security and reliability.

10. Challenges and Future Trends in Secure Bootloa...

10.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography for Secure Boot

The emergence of quantum computing poses a significant threat to traditional cryptographic algorithms used in secure bootloaders, such as RSA and ECDSA, which could be broken by quantum attacks. Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) aims to develop quantum-resistant algorithms to replace or supplement classical cryptography. PQC secure bootloaders integrate quantum-safe signatures like lattice-based (ML-DSA), hash-based (XMSS, LMS), or code-based schemes to verify firmware authenticity. However, PQC introduces trade-offs such as increased computational latency (due to hybrid classical and quantum-safe verification), larger signature sizes, and novel key management challenges. The hybrid transition approach—running both classical and post-quantum verifications—is common to ensure backward compatibility during migration. Further research focuses on optimizing PQC for embedded systems’ constrained resources to enable low-latency and secure boot processes.

10.2. AI-Driven Threat Detection during Boot Processes

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) techniques are being explored to augment secure boot processes by detecting anomalous behaviors indicative of tampering or pre-boot malware presence. AI-driven threat detection monitors boot sequence parameters, timing, and firmware behavior, enabling more adaptive and proactive security. This approach complements traditional cryptographic verification by identifying zero-day exploits or novel threats that evade signature-based checks. Incorporating AI requires careful design to minimize computational overhead and false positives while maintaining real-time boot operations.

10.3. Secure Over-the-Air (OTA) Bootloaders

Secure OTA bootloaders enable remote firmware updates with end-to-end cryptographic protection, ensuring authenticity and integrity throughout transmission and installation. These systems involve strong authentication methods, secure update delivery channels, rollback prevention, and fail-safe mechanisms to maintain device availability even if updates fail. OTA secure bootloaders must also accommodate network constraints, intermittent connectivity, and version control to prevent downgrade attacks. Integration with secure boot ensures that only verified updated firmware boots successfully post-installation.

10.4. Blockchain-Enabled Firmware Integrity Tracking

Blockchain technology offers a decentralized and tamper-evident ledger for logging firmware versions, update histories, and cryptographic hashes in embedded system ecosystems. Leveraging blockchain enhances transparency, traceability, and trustworthiness of firmware by providing immutable records accessible by manufacturers, service providers, and regulators. This approach supports distributed device fleets, improving security audits and compliance verification while reducing single points of failure. Challenges include blockchain scalability, latency, and managing privacy in constrained embedded environments.

11. Conclusions

In conclusion, the utilization of secure bootloaders in embedded systems plays a critical role in safeguarding device integrity and preventing firmware tampering through sophisticated cryptographic validation mechanisms. By establishing a hardware-rooted chain of trust and employing robust public key cryptography, digital signatures, and cryptographic hash functions, secure bootloaders ensure that only authenticated and untampered firmware can execute, thereby protecting against malicious code injection and rollback attacks.

Industrial implementations across domains such as automotive ECUs, IoT devices, and industrial control systems have demonstrated the effectiveness of secure bootloaders in real-world scenarios, often adhering to stringent security standards like ISO 21434, NIST guidelines, and MISRA coding practices. Hardware-assisted security features like Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs), Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), ARM TrustZone, and Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs) greatly enhance the security posture by providing tamper-resistant environments for key storage and cryptographic operations.

Performance optimization remains a vital consideration, balancing rigorous security verification with boot time and resource constraints inherent in embedded platforms. Lightweight cryptographic algorithms and hardware accelerators are commonly leveraged to achieve this balance.

Looking forward, emerging challenges such as quantum computing threats are driving the adoption of post-quantum cryptography to future-proof embedded system security. Additionally, AI-driven threat detection during boot, secure over-the-air update bootloaders, and blockchain-enabled firmware integrity tracking represent promising trends enhancing resilience and trustworthiness.

Ultimately, secure bootloaders constitute a cornerstone of modern embedded system security, enabling a trustworthy computing environment by defending the foundational firmware layer from sophisticated attacks, thereby securing the operational integrity and reliability of embedded devices.

References

- Sharma, T., Reddy, D. N., Kaur, C., Godla, S. R., Salini, R., Gopi, A., & Baker El-Ebiary, Y. A. (2024). Federated Convolutional Neural Networks for Predictive Analysis of Traumatic Brain Injury: Advancements in Decentralized Health Monitoring. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 15(4). [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, S., Joshi, S. S., Sharma, S., Radhakrishnan, M., Krishna, K. M., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Additive manufacturing of FeCrAl alloys for nuclear applications-A focused review. Nuclear Materials and Energy, 40, 101702. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu Kavin, B., Karki, S., Hemalatha, S., Singh, D., Vijayalakshmi, R., Thangamani, M., ... & Adigo, A. G. (2022). Machine learning-based secure data acquisition for fake accounts detection in future mobile communication networks. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022(1), 6356152. [CrossRef]

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2021, February). Automatic classification and accuracy by deep learning using cnn methods in lung chest X-ray images. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1055, No. 1, p. 012099). IOP Publishing.

- Vidyabharathi, D., Mohanraj, V., Kumar, J. S., & Suresh, Y. (2023). Achieving generalization of deep learning models in a quick way by adapting T-HTR learning rate scheduler. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 27(3), 1335-1353. [CrossRef]

- Arul Selvan, M. (2025). Detection of Chronic Kidney Disease Through Gradient Boosting Algorithm Combined with Feature Selection Techniques for Clinical Applications.

- Kuchukuntla, M., Palanivel, V., & Madhubabu, A. (2023). Tofacitinib citrate-loaded nanoparticle gel for the treatment of alopecia areata: Response surface design, formulation and in vitro-in vivo characterization. Recent Advances in Drug Delivery and Formulation: Formerly Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation, 17(4), 314-331. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, G., Kuppusamy, S., & Aswathanarayanan, M. (2025). Sustainable crop recommendation system using seasonally adaptive recursive spectral convolutional neural network for responsible agricultural production. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 16(1), 2509619. [CrossRef]

- Raja, A. S., Peerbasha, S., Iqbal, Y. M., Sundarvadivazhagan, B., & Surputheen, M. M. (2023). Structural Analysis of URL For Malicious URL Detection Using Machine Learning. Journal of Advanced Applied Scientific Research, 5(4), 28-41. [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, B., & Thangamani, M. (2020). An efficient Pearson correlation based improved random forest classification for protein structure prediction techniques. Measurement, 162, 107885. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T. R., & Kavitha, C. (2013). Web user interest prediction framework based on user behavior for dynamic websites. Life Sci. J, 10(2), 1736-1739.

- Jawaharlal, S., Subramanian, S., Palanivel, V., Devarajan, G., & Veerasamy, V. (2024). Cyclodextrin-based nanosponges as promising carriers for active pharmaceutical ingredient. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 38(1), e23597. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M. W., & Nirmala, D. K. (2016). Agile development methods for online training courses web application development. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN, 0973-4562.

- Kumar, R. D., Saravanan, K., Nallusamy, C., & Sakthivel, K. (2025, April). Transformative Ai-Driven Tamil Sign Language Recognition and Speech Synthesis Using ViT-CNN. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications Theme: Healthcare and Internet of Things (AIMLA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2019). Lung segmentation in chest X-ray images using Canny with morphology and thresholding techniques. Int. j. adv. innov. res, 6(1), 1-7.

- Geeitha, S., & Thangamani, M. (2018). Incorporating EBO-HSIC with SVM for gene selection associated with cervical cancer classification. Journal of medical systems, 42(11), 225. [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2020). A survey on recent trends in content based image retrieval system. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11), 961-965.

- Ramesh, T. R., Raghavendra, R., Vantamuri, S. B., Pallavi, R., & Easwaran, B. (2023). IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF VANET COMMUNICATION USING FEDERATED PEER-TO-PEER LEARNING. ICTACT Journal on Communication Technology, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J., Radhakrishnan, M., Palaniappan, S., Krishna, K. M., Biswas, K., Srinivasan, S. G., ... & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Cr content dependent lattice distortion and solid solution strengthening in additively manufactured CoFeNiCrx complex concentrated alloys–a first principles approach. Materials Today Communications, 40, 109485. [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, K., Arularasi, S., Gopinath, S., Vinoth, M., Kowsalya, G., & Lalitha, S. (2025, April). Deep Learning-Based Approach for Accurate Plant Disease Identification Using Image Analysis. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications Theme: Healthcare and Internet of Things (AIMLA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Thangamani, M., & Thangaraj, P. (2010). Integrated Clustering and Feature Selection Scheme for Text Documents. Journal of Computer Science, 6(5), 536. [CrossRef]

- Boopathy, D., & Balaji, P. (2023). Effect of different plyometric training volume on selected motor fitness components and performance enhancement of soccer players. Ovidius University Annals, Series Physical Education and Sport/Science, Movement and Health, 23(2), 146-154.

- Venkatesan, P., Subrahmanyam, P. V. R. S., & Pratap, D. R. (2010). Spectrophotometric determination of pure amitriptyline hydrochloride through ligand exchange on mercuric ion. Int J ChemTech Res, 2(1), 54-56.

- Jaishankar, B., Ashwini, A. M., Vidyabharathi, D., & Raja, L. (2023). A novel epilepsy seizure prediction model using deep learning and classification. Healthcare analytics, 4, 100222. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T. R., Sreevani, N., Babu, G. J. S., Singh, N., & Kareem, A. (2024, November). Machine Learning Model to Analyse Noisy Data by Scanning Probe Microscope. In 2024 Second International Conference Computational and Characterization Techniques in Engineering & Sciences (IC3TES) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Ramya, K., Vaidyanathan, V., Suriyaa, M., Senthilselvi, A., & Selvan, M. A. (2025, August). Automated Attendance Monitoring System using Real-Time Facial Recognition and Python based Computer Vision Techniques. In 2025 8th International Conference on Circuit, Power & Computing Technologies (ICCPCT) (pp. 1703-1708). IEEE.

- Niasi, K. S. K., Kannan, E., & Suhail, M. M. (2016). Page-level data extraction approach for web pages using data mining techniques. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, 7(3), 1091-1096.

- Karthikeyan, K., Geetha, B. G., Sakthivel, K., Vignesh, S., Hemalatha, S., & Meena, M. (2025, April). Exploring Machine Learning Algorithms for Identifying Optimal Features to Predict Childbirth Modes. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications Theme: Healthcare and Internet of Things (AIMLA) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2019). Automatic thresholding for segmentation in chest X-ray images based on green channel using mean and standard deviation. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE), 8(8), 695-699.

- Hamed, S., Mesleh, A., & Arabiyyat, A. (2021). Breast cancer detection using machine learning algorithms. International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, 10(11), 4-11. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, V., Sumalatha, A., Reddy, D. N., Ahamed, B. S., & Udayakumar, K. (2024, October). Exploring Decentralized Identity Verification Systems Using Blockchain Technology: Opportunities and Challenges. In 2024 5th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Boopathy, D., & Balaji, D. P. Training outcomes of yogic practices and aerobic dance on selected health related physical fitness variables among tamilnadu male artistic gymnasts. Sports and Fitness, 28.

- Valliappan, K., Vaithiyanathan, S. J., & Palanivel, V. (2013). Direct chiral HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of warfarin enantiomers and its impurities in raw material and pharmaceutical formulation: application of chemometric protocol. Chromatographia, 76(5), 287-292. [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, A., & Thamilarasi, V. (2023, March). Classification of lung chest X-ray images using deep learning with efficient optimizers. In 2023 IEEE 13th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) (pp. 0465-0469). IEEE.

- Marimuthu, M., Mohanraj, G., Karthikeyan, D., & Vidyabharathi, D. (2023). RETRACTED: Safeguard confidential web information from malicious browser extension using Encryption and Isolation techniques. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 45(4), 6145-6160. [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Content Based Medical Image Retrieval System Based On Multi Model Clustering Segmentation And Multi-Layer Perception Classification Methods. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 12(7).

- Ramya, K., Rithwik, R., VIjaay, E. M., Kumar, S., Senthilselvi, A., & Selvan, M. A. (2025, August). Climate-Aware Plant Phenotyping and Crop Suitability Prediction Using CNN+ XGBoost. In 2025 8th International Conference on Circuit, Power & Computing Technologies (ICCPCT) (pp. 1921-1925). IEEE.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2021). U-NET: convolution neural network for lung image segmentation and classification in chest X-ray images. INFOCOMP: Journal of Computer Science, 20(1), 101-108.

- Gangadhar, C., Chanthirasekaran, K., Chandra, K. R., Sharma, A., Thangamani, M., & Kumar, P. S. (2022). An energy efficient NOMA-based spectrum sharing techniques for cell-free massive MIMO. International Journal of Engineering Systems Modelling and Simulation, 13(4), 284-288. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T. R., Kumar, K., Asha, V., Kumar, S. N., Kumar, M., & Kareem, A. (2024, November). Implementing RNN and LSTM Models to Electrical Load Predictions. In 2024 Second International Conference Computational and Characterization Techniques in Engineering & Sciences (IC3TES) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Sakthivel, K., Ashwin, J., Poongodi, K., & Oviya, S. (2025, March). Image Analysis for Historical Knowledge Discovery and Preservation. In 2025 International Conference on Visual Analytics and Data Visualization (ICVADV) (pp. 895-900). IEEE.

- Raja, M. W. (2024). Artificial intelligence-based healthcare data analysis using multi-perceptron neural network (MPNN) based on optimal feature selection. SN Computer Science, 5(8), 1034. [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, R., Vidyabharathi, D., Kumar, S. S., Mali, M., Arunkumar, M., Aravinth, S. S., ... & Tesfayohanis, M. (2023). [Retracted] Wearable Sensor-Based Edge Computing Framework for Cardiac Arrhythmia Detection and Acute Stroke Prediction. Journal of Sensors, 2023(1), 3082870. [CrossRef]

- Surendiran, R., Aarthi, R., Thangamani, M., Sugavanam, S., & Sarumathy, R. (2022). A systematic review using machine learning algorithms for predicting preterm birth. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 70(5), 46-59. [CrossRef]

- Thamilarasi, V., Naik, P. K., Sharma, I., Porkodi, V., Sivaram, M., & Lawanyashri, M. (2024, March). Quantum computing-navigating the frontier with Shor’s algorithm and quantum cryptography. In 2024 International conference on trends in quantum computing and emerging business technologies (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Juliet, P. S., & Janani, V. (2025, May). Detecting Apple and Maize Plant Diseases using GAN and GNN. In 2025 Global Conference in Emerging Technology (GINOTECH) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Radhakrishnan, M., Sharma, S., Palaniappan, S., Pantawane, M. V., Banerjee, R., Joshi, S. S., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Influence of thermal conductivity on evolution of grain morphology during laser-based directed energy deposition of CoCrxFeNi high entropy alloys. Additive Manufacturing, 92, 104387. [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S., Kumar, A. K. V., Reddy, D. N., Pathipati, H., Priyadarsini, N. I., & Ramisetti, L. N. B. (2025). Modeling of chimp optimization algorithm node localization scheme in wireless sensor networks. Int J Reconfigurable & Embedded Syst, 14(1), 221-230. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T. R., Sharma, A. K., Balaji, T., & Umamaheswari, S. (2025). Utilizing Quantum Networks to Ensure the Security of AI Systems in Healthcare. In AI and Quantum Network Applications in Business and Medicine (pp. 353-370). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

- Venkatesan, P., Manavalan, R., & Valliappan, K. (2011). Preparation and evaluation of sustained release loxoprofen loaded microspheres. Journal of basic and clinical pharmacy, 2(3), 159.

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2021). Multi Model Clustering Segmentation and Intensive Pragmatic Blossoms (Ipb) Classification Method based Medical Image Retrieval System. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(3), 7841-7852.

- Thamilarasi, V., & Roselin, R. (2019). Survey on Lung Segmentation in Chest X-Ray Images. The International Journal of Analytical and Experimental Modal Analysis, 1-9.

- Selvam, P., Faheem, M., Dakshinamurthi, V., Nevgi, A., Bhuvaneswari, R., Deepak, K., & Sundar, J. A. (2024). Batch normalization free rigorous feature flow neural network for grocery product recognition. IEEE Access, 12, 68364-68381. [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel, K., Kowsalya, A., Durgadevi, M., & Dhaneswar, R. C. (2025, January). Hybrid Deep Learning for Proactive Driver Risk Prediction and Safety Enhancement. In 2025 International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems for Collaborative Intelligence (ICMSCI) (pp. 1572-1577). IEEE.

- Banu, S. S., Niasi, K. S. K., & Kannan, E. (2019). Classification Techniques on Twitter Data: A Review. Asian Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 8(S2), 66-69. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, V., Upender, T., Ruby, E. K., Deepalakshmi, P., Reddy, D. N., & SN, A. (2024, October). Machine Learning Approaches for Advanced Threat Detection in Cyber Security. In 2024 5th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Reddy, D. N., Venkateswararao, P., Vani, M. S., Pranathi, V., & Patil, A. (2025). HybridPPI: A Hybrid Machine Learning Framework for Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (IJEEI), 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, M., Sharma, S., Palaniappan, S., & Dahotre, N. B. (2024). Evolution of microstructures in laser additive manufactured HT-9 ferritic martensitic steel. Materials Characterization, 218, 114551. [CrossRef]

- Boopathy, D., Singh, S. S., & PrasannaBalaji, D. EFFECTS OF PLYOMETRIC TRAINING ON SOCCER RELATED PHYSICAL FITNESS VARIABLES OF ANNA UNIVERSITY INTERCOLLEGIATE FEMALE SOCCER PLAYERS. EMERGING TRENDS OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND SPORTS SCIENCE.

- Thamilarasi, V., Asaithambi, A., & Roselin, R. (2025). ENHANCED ENSEMBLE SEGMENTATION OF LUNG CHEST X-RAY IMAGES BY DENOISING AUTOENCODER AND CLAHE. ICTACT Journal on Image & Video Processing, 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Saraswathi, R. J., Mahalingam, T., Devikala, S., Ramesh, T. R., & Sivakumar, K. (2024). Beyond the Current State of the Art in Electric Vehicle Technology in Robotics and Automation. J. Electrical Systems, 20(4s), 2282-2291.

- Inbaraj, R., & Ravi, G. (2020). Content Based Medical Image Retrieval Using Multilevel Hybrid Clustering Segmentation with Feed Forward Neural Network. Journal of Computational and Theoretical Nanoscience, 17(12), 5550-5562. [CrossRef]

- Satheesh, N., & Sakthivel, K. (2024, December). A Novel Machine Learning-Enhanced Swarm Intelligence Algorithm for Cost-Effective Cloud Load Balancing. In 2024 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Sivakumar, T., Venkatesan, P., Manavalan, R., & Valliappan, K. (2007). Development of a HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of losartan potassium and atenolol in tablets. Indian journal of pharmaceutical sciences, 69(1).

- Narmatha, C., Thangamani, M., & Ibrahim, S. J. A. (2020). Research scenario of medical data mining using fuzzy and graph theory. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering, 9(1), 349-355.

- Vidyabharathi, D., & Mohanraj, V. (2023). Hyperparameter Tuning for Deep Neural Networks Based Optimization Algorithm. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, 36(3). [CrossRef]

- Mubsira, M., & Niasi, K. S. K. (2018). Prediction of Online Products using Recommendation Algorithm.

- Sureshkumar, T. (2015). Usage of Electronic Resources Among Science Research Scholars in Tamil Nadu Universities A Study.

- RAJA, M. W., PUSHPAVALLI, D. M., BALAMURUGAN, D. M., & SARANYA, K. (2025). ENHANCED MED-CHAIN SECURITY FOR PROTECTING DIABETIC HEALTHCARE DATA IN DECENTRALIZED HEALTHCARE ENVIRONMENT BASED ON ADVANCED CRYPTO AUTHENTICATION POLICY. TPM–Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 32(S4 (2025): Posted 17 July), 241-255.

- Rao, A. S., Reddy, Y. J., Navya, G., Gurrapu, N., Jeevan, J., Sridhar, M., ... & Anand, D. High-performance sentiment classification of product reviews using GPU (parallel)-optimized ensembled methods. [CrossRef]

- Thamilarasi, V. A Detection of Weed in Agriculture Using Digital Image Processing. International Journal of Computational Research and Development, ISSN, 2456-3137.

- Kamatchi, S., Preethi, S., Kumar, K. S., Reddy, D. N., & Karthick, S. (2025, May). Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm Optimised Convolutional Neural Networks for Improved Pancreatic Cancer Detection. In 2025 3rd International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Karuppusamy, C., & Venkatesan, P. (2017). Role of nanoparticles in drug delivery system: a comprehensive review. Journal of Pharmaceutical sciences and Research, 9(3), 318.

- Jayalakshmi, N., & Sakthivel, K. (2024, December). A Hybrid Approach for Automated GUI Testing Using Quasi-Oppositional Genetic Sparrow Search Algorithm. In 2024 International Conference on Innovative Computing, Intelligent Communication and Smart Electrical Systems (ICSES) (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Sureshkumar, T., Charanya, J., Kumaresan, T., Rajeshkumar, G., Kumar, P. K., & Anuj, B. (2024, April). Envisioning Educational Success Through Advanced Analytics and Intelligent Performance Prediction. In 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP) (pp. 1649-1654). IEEE.

- Ramesh, T. R., Jackulin, T., Kumar, R. A., Chanthirasekaran, K., & Bharathiraja, M. (2024). Machine learning-based intrusion detection: A comparative analysis among datasets and innovative feature reduction for enhanced cybersecurity. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(12s), 200-206.

- Palaniappan, S., Sharma, S., Radhakrishnan, M., Krishna, K. M., Joshi, S. S., Banerjee, R., & Dahotre, N. B. (2025). Process thermokinetics influenced microstructure and corrosion response in additively in-situ manufactured Ti-Nb-Sn and Ti-Nb alloys. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 152, 427-441. [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, M., Vidhya, G., Dhaynithi, J., Mohanraj, G., Basker, N., Theetchenya, S., & Vidyabharathk, D. (2021). Detection of Parkinson’s disease using Machine Learning Approach. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(5), 2544-2550.

- Niasi, K. S. K., & Kannan, E. (2016). Multi Attribute Data Availability Estimation Scheme for Multi Agent Data Mining in Parallel and Distributed System. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 11(5), 3404-3408.

- Thangamani, M., & Thangaraj, P. (2013). Fuzzy ontology for distributed document clustering based on genetic algorithm. Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences, 7(4), 1563-1574. [CrossRef]

- Nimma, D., Rao, P. L., Ramesh, J. V. N., Dahan, F., Reddy, D. N., Selvakumar, V., ... & Jangir, P. (2025). Reinforcement Learning-Based Integrated Risk Aware Dynamic Treatment Strategy for Consumer-Centric Next-Gen Healthcare. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics. [CrossRef]

- Charanya, J., Sureshkumar, T., Kavitha, V., Nivetha, I., Pradeep, S. D., & Ajay, C. (2024, June). Customer Churn Prediction Analysis for Retention Using Ensemble Learning. In 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT) (pp. 1-10). IEEE.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).