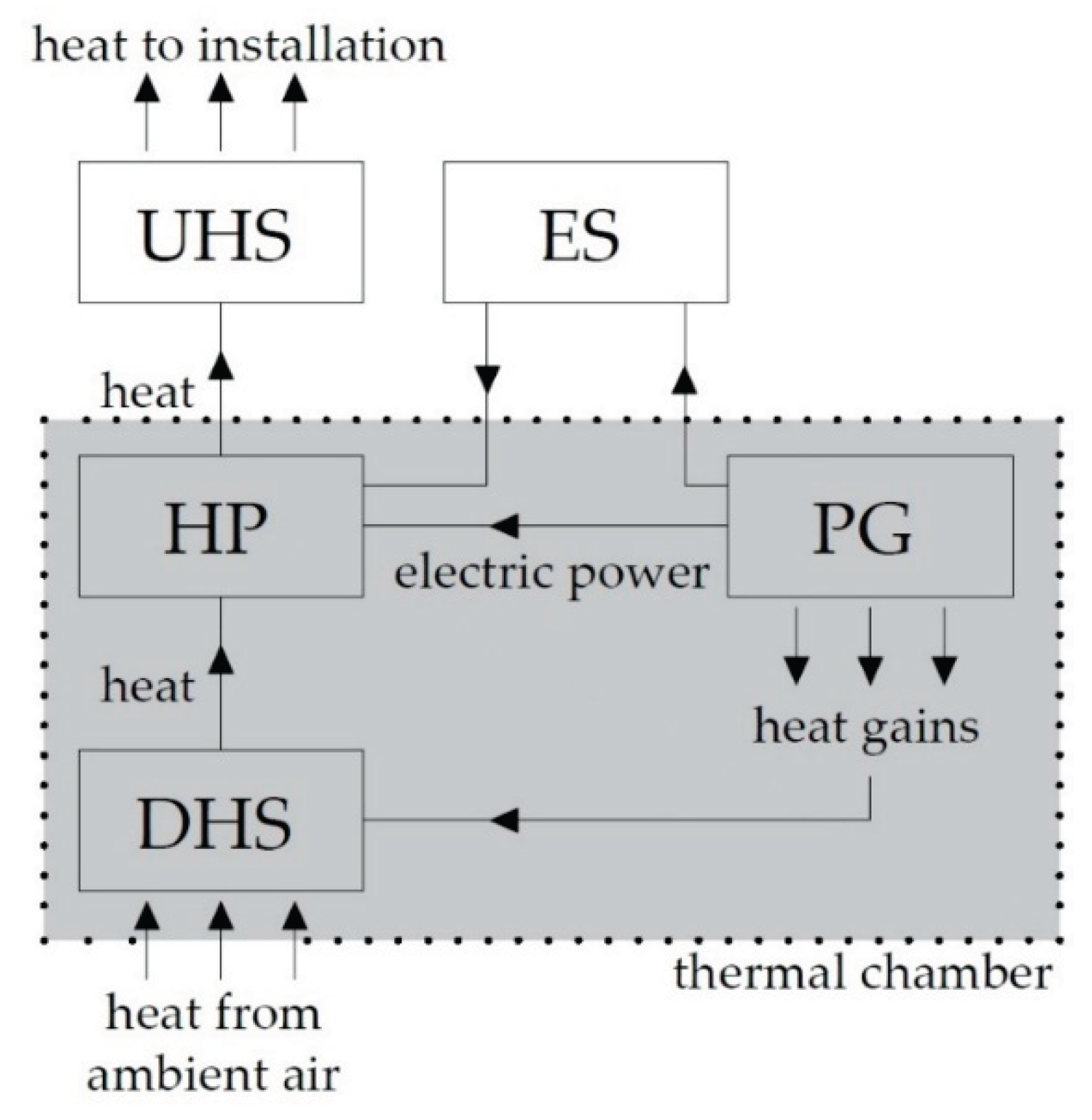

In this study, a theoretical model of the system’s operation is presented, complemented by an experimental component that enabled empirical verification of the assumed performance parameters of the generator set under controlled conditions, including generator output, the amount of waste heat produced, and the rate of thermal-chamber heating.

3.2. Preliminary Experimental Verification

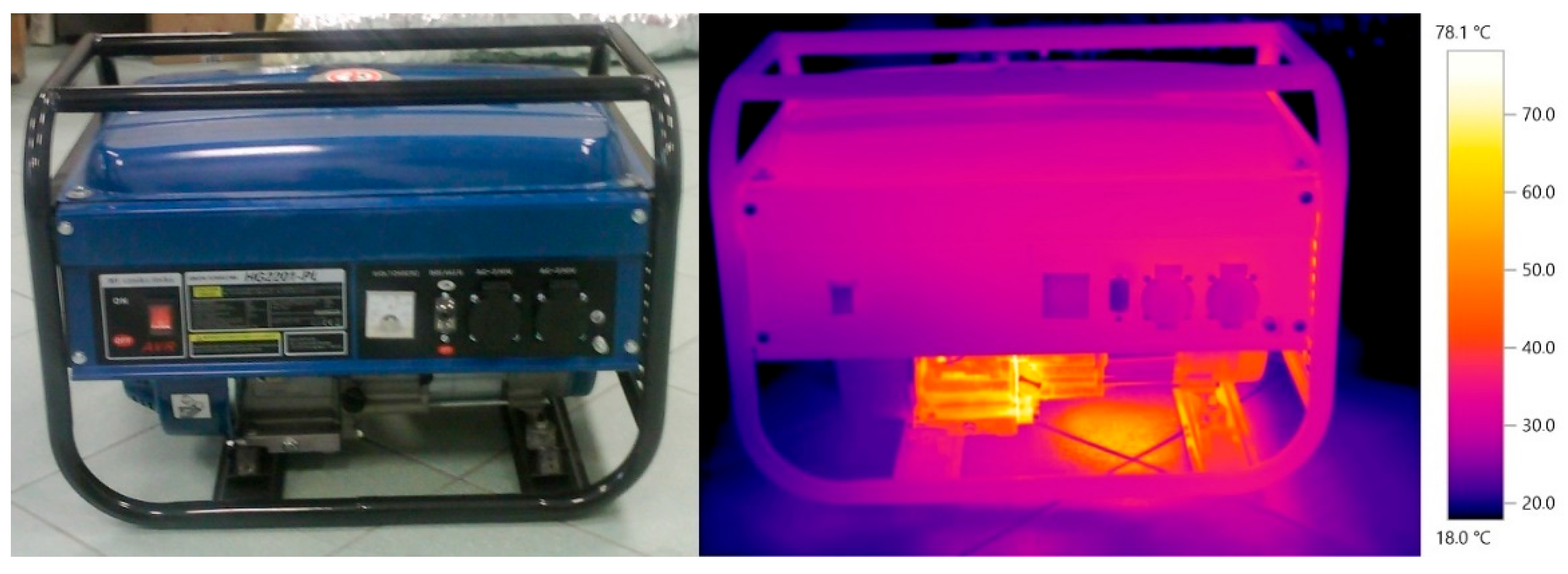

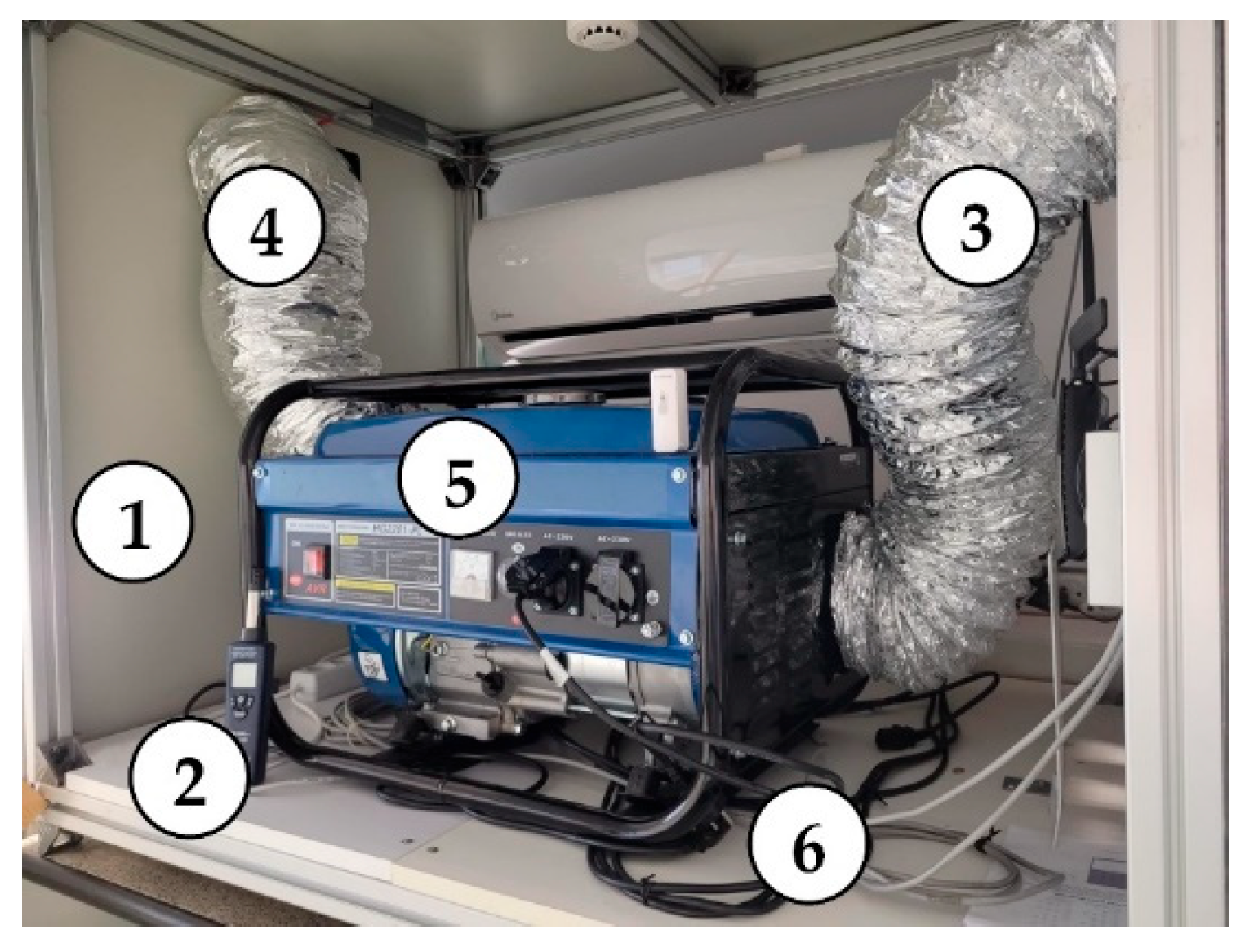

As part of the experimental stage, the generator set with parameters listed in

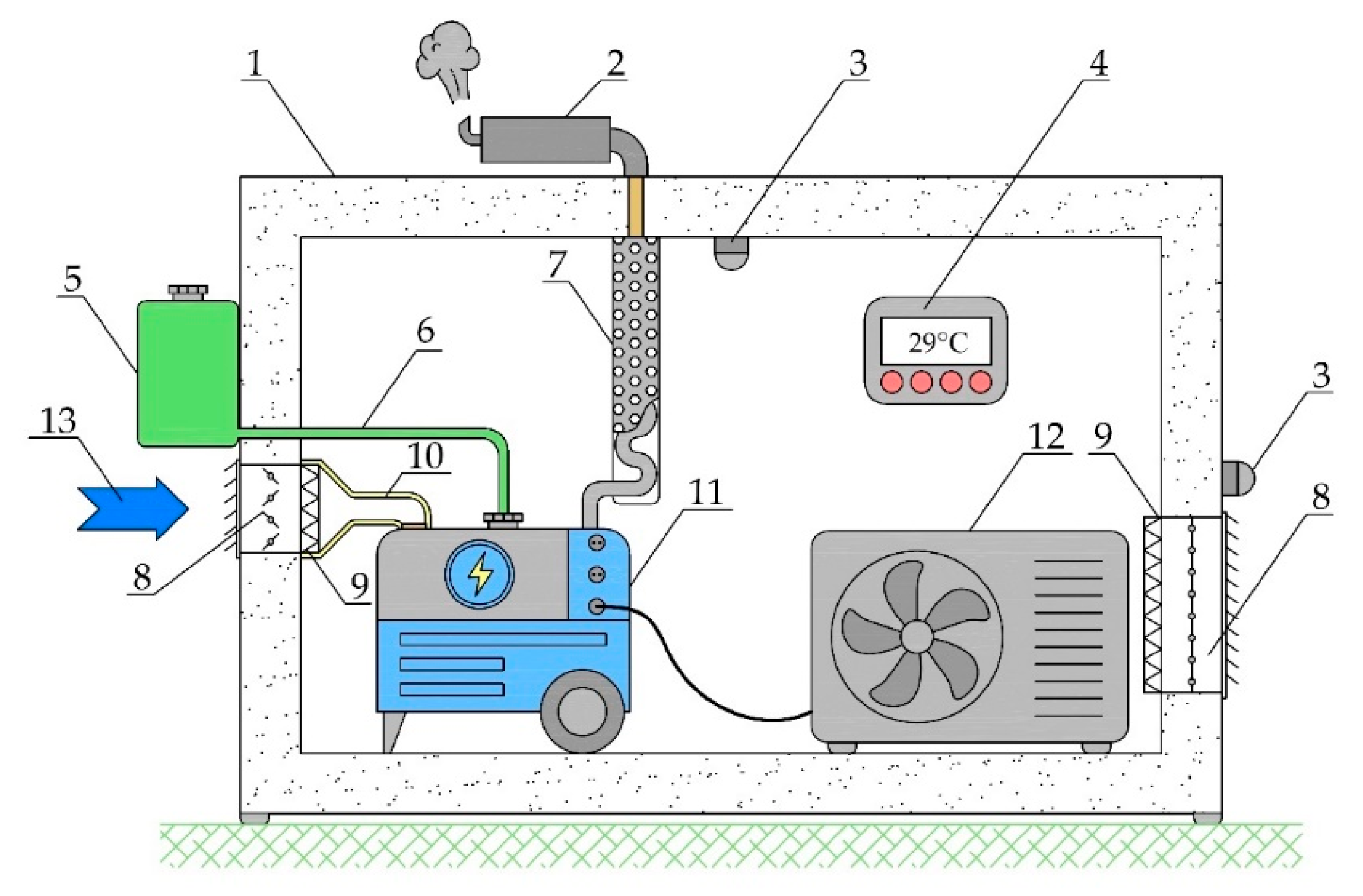

Table 1 was placed inside a thermally insulated chamber equipped with an air supply duct for the engine and an exhaust-gas removal system. The chamber insulation was constructed using mineral wool placed between two layers of steel-clad composite panels, providing an overall thermal efficiency of approximately 95% for a temperature difference of 60 K (−20°C outside and +40°C inside the chamber). The chamber dimensions were 1.5×1.2×1.2 m, resulting in a total internal volume of 2.16 m³.

Inside the chamber, Pt1000 resistance temperature sensors were installed within the working space to ensure accurate measurements of temperature distribution and temporal changes during generator operation, as well as to monitor the temperature outside the chamber. A 2000 W electric heater was connected as the electrical load for the generator. The layout of the experimental setup is shown in

Figure 4.

The purpose of this stage was to determine the distribution of electrical power and thermal power generated by the generator set. Electrical energy was measured using an electricity consumption meter, whereas the amount of thermal energy was determined based on the temperature increase inside the insulated thermal chamber. At this stage, the heat pump itself was not included in the verification process.

During the experimental investigation, the air temperature inside the thermal chamber was measured at the beginning and at the end of the generator’s operation, which enabled the determination of the temperature increase ΔT and, consequently, the calculation of the thermal power generated by the unit. The initial air temperature inside the chamber was 20°C. The measurements were continued until the internal temperature reached 50°C. This temperature is fully sufficient to supply the heat pump’s low-temperature heat source for the production of heat at temperatures exceeding 50°C. The decision to limit the temperature was also motivated by safety considerations, particularly the risk of gasoline vapour ignition in the generator’s fuel tank at elevated temperatures.

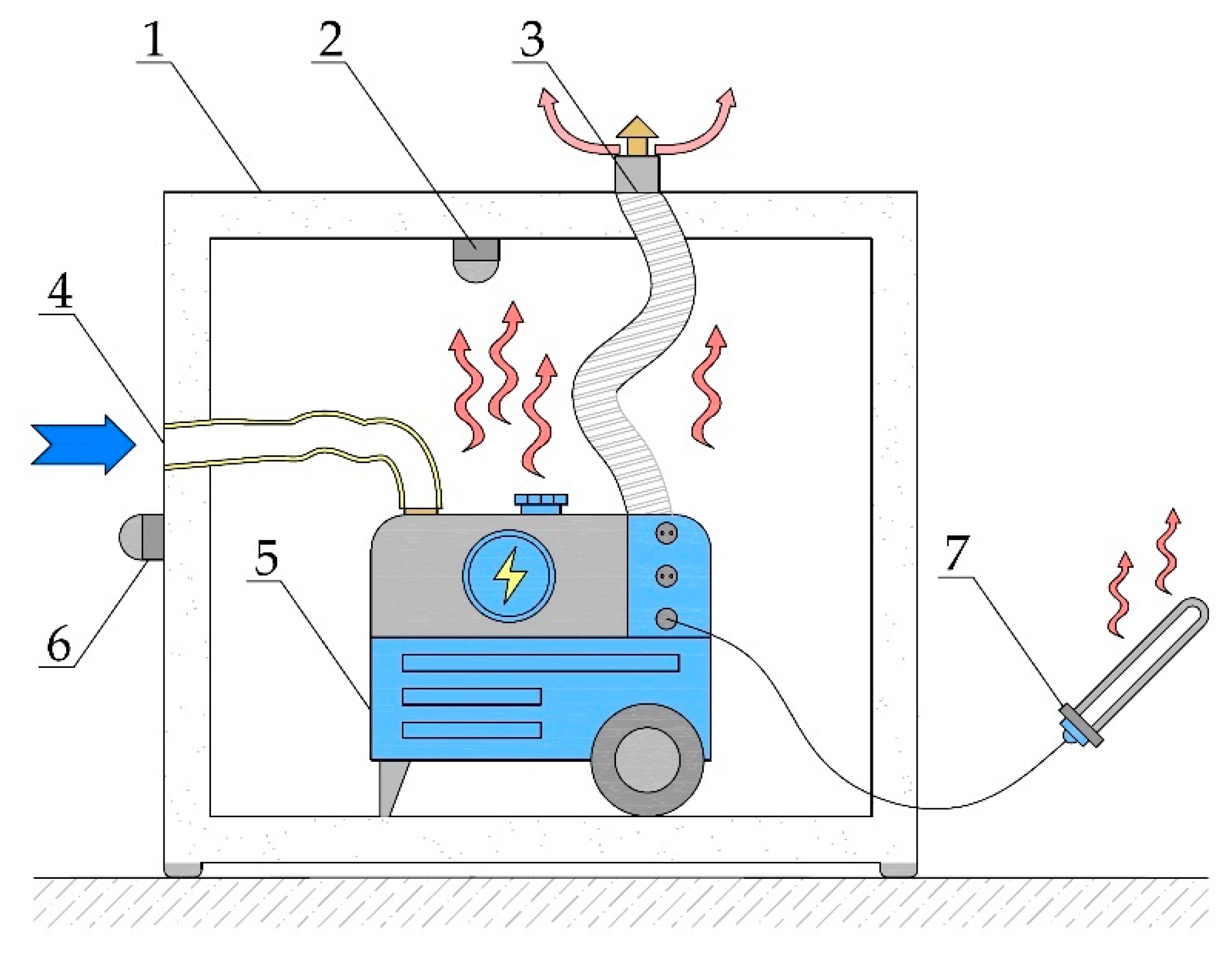

The exhaust gases were discharged outside the chamber through a flexible stainless-steel flue duct. A portion of the exhaust heat was transferred directly into the chamber through the duct walls, contributing to the overall heat gain within the enclosed space. The experimental setup is presented in

Figure 5.

Based on the measured temperature values and the corresponding operating time, the actual thermal power transferred to the air inside the chamber was determined. These results were compared with the electrical power generated by the generator set, allowing an assessment of its combined thermal-electrical performance. This comparison makes it possible to relate the obtained experimental values to the theoretical Sankey distribution for an internal combustion engine, the reference values of which are presented in

Table 2.

It should be emphasized, however, that these considerations are of a theoretical nature. The experimental tests were not carried out under rigorous laboratory conditions but served as a preliminary verification of the underlying assumptions. Therefore, the results should be regarded as indicative, providing a useful basis for further and more detailed analyses.

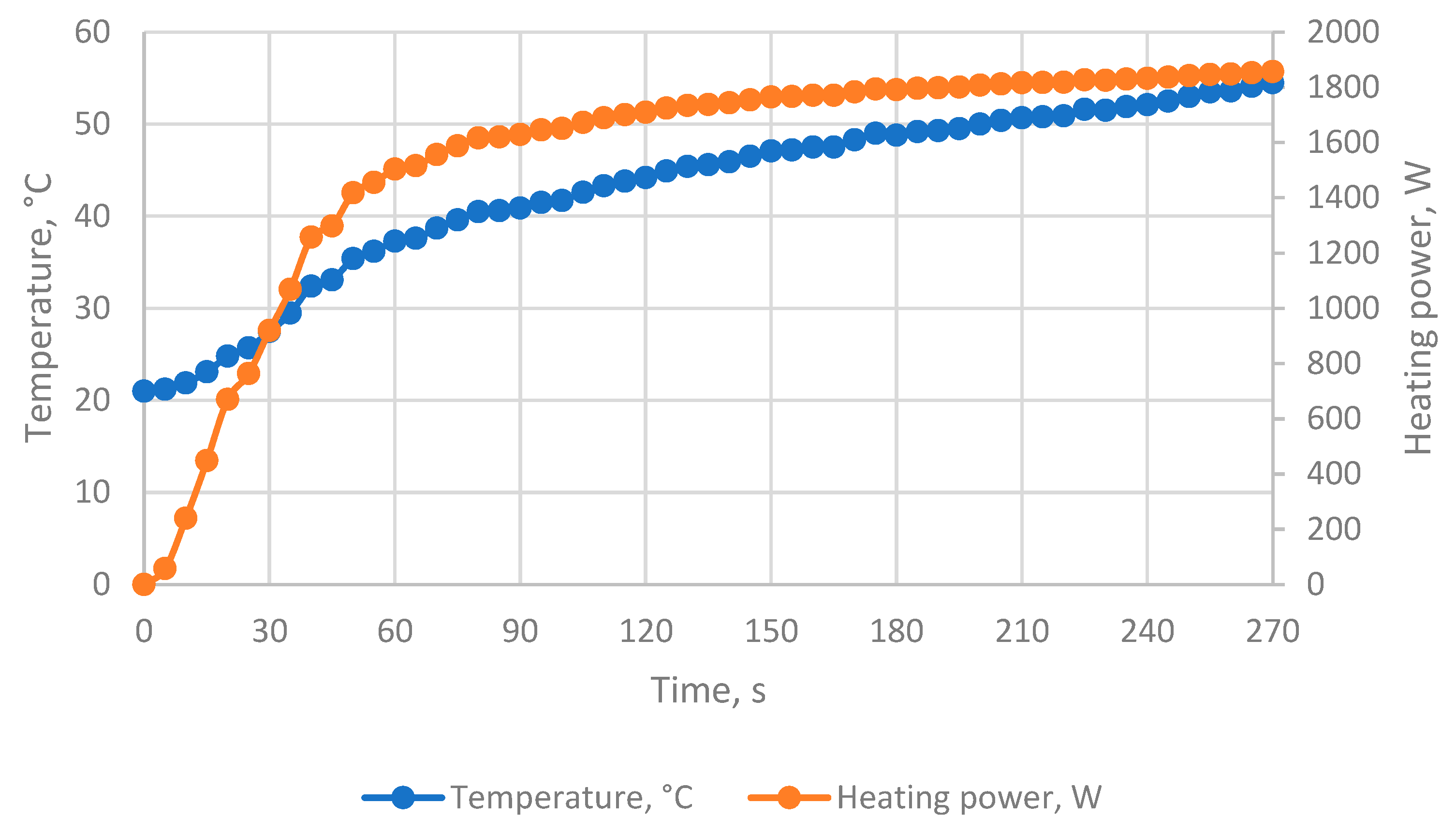

Figure 6 presents the measured temperature profile and the corresponding thermal power recovered inside the chamber, originating from the generator set, for the analysed thermal enclosure with a volume of 2.16 m³.

The energy balance of the device can be expressed as follows. First, the theoretical heat losses associated with the exhaust gases, the engine block, and the mechanical losses manifesting primarily as friction-related heat, must be summed. The total value of these losses equals 4665 W. If the electrical output power of the generator is 2000 W, this corresponds to a required fuel input power of approximately 6665 W. Therefore, the theoretical efficiency derived from the Sankey-type distribution of energy in the generator set is 2 000 W / 6 665 W, i.e., approximately 30.0%.

The initial slow rise in temperature and thermal output was caused by the need to heat up the cold structural surfaces of both the chamber and the generator itself. After approximately 80 seconds, the rate of heat increase became limited by the thermal capacity of the chamber. As shown in Fig. 6, the temperature begins to asymptotically approach a steady-state value, at which the balance between the heat supplied and the heat dissipated (including losses through the chamber walls) is reached. The tests were conducted under constrained experimental conditions, which do not fully represent the actual energy performance of the generator set. In the closed thermal chamber with a volume of 2.16 m³ and for a relatively short operating period of 270 seconds, the maximum recorded thermal output was 1 856 W. This value indicates a significantly lower efficiency of converting the fuel’s chemical energy into usable heat compared with the theoretical 30% assigned to engine heat losses and the additional 30% associated with exhaust gases in the Sankey model.

This discrepancy is justified, as only a fraction of the thermal energy contained in the high-temperature exhaust gases was able to transfer through the walls of the exhaust duct into the chamber within such a short exposure time. A more effective exhaust heat recovery design would therefore be required, for example, by integrating extended surface heat exchangers (finned structures) or by replacing natural convection with forced convection to increase heat transfer. Furthermore, the system likely did not reach full thermal stabilization, as the measurement was intentionally stopped once the target internal temperature of 50°C was reached. At the beginning of operation, a considerable portion of the generated thermal energy is absorbed by the generator’s own components, such as the housing, cooling system, piping, and exhaust system. These components possess their own heat capacity, and heating them requires time. Only after they reach a higher temperature does heat begin to transfer more effectively to the surrounding air inside the chamber.

If the measurement is interrupted too early, the generator may still be in its warm-up phase, meaning that a significant portion of the produced heat has not yet transferred to the air. The experimental results therefore indicate an effective thermal recovery efficiency of approximately 28%, rather than the 60% predicted by the theoretical Sankey model. Assuming the validity of the Sankey distribution, the experimental setup suggests that as much as 32% of the total thermal energy may have been lost through mechanisms such as incomplete recovery of exhaust heat and heat conduction through the chamber structure—representing the difference between the theoretical 60% and the measured 28%.

The discrepancy arises from several factors, such as excessive heat losses to the surroundings, the relatively slow heating of the generator, and an insufficient contribution of exhaust-gas heat to the chamber’s overall heat balance. Despite these differences, the key assumption has been confirmed, namely, that it is possible to achieve a high chamber temperature, which should allow the heat pump to operate with a high COP.

The obtained results are very useful, as they define the next steps required to significantly improve the performance of the proposed system consisting of a heat pump and a generator set enclosed in a thermal chamber. To increase the heat recovery ratio in future studies, it is planned, among other measures, to reduce heat losses to the environment by improving the insulation and sealing of the chamber, to increase the contribution of exhaust-gas heat by implementing a more efficient exhaust heat exchanger, and to enhance the distribution of hot air inside the chamber by using a small circulation fan.

3.3. Analysis of the Operation of the Heat Pump and Generator Set

In this section, based on real operational data from a heat pump installed in a single-family house with a floor area of 136 m², a heating demand of 6 kW, and occupied by two adults, an analysis was carried out of the thermal energy consumption for space heating, domestic hot water (DHW) preparation, and the total electrical energy consumption of a 7 kW heat pump. The heat pump was selected in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines based on the bivalent temperature. The building is equipped with a low-temperature underfloor heating system for space-heating purposes, while DHW is supplied by a 200-litre storage tank.

The heat pump supplies two main heating circuits. The first circuit covers space heating (SH) via underfloor heating, for which the required supply temperature is 35 °C. The second circuit is responsible for DHW preparation and requires a higher supply temperature of 55 °C. The difference in required temperatures between these circuits has a direct impact on the heat pump’s coefficient of performance (COP).

The outdoor unit of the heat pump is intended to be installed inside the thermal chamber together with the generator set, which will serve a dual function: generating electrical energy for the heat pump and household appliances, and providing waste heat to warm the air inside the chamber. The temperature inside the thermal chamber will be maintained at a minimum of 15 °C, instead of the previously tested 50 °C. Maintaining such a temperature enables the heat pump to operate with a high COP while simultaneously reducing the risk of overheating critical components, thereby lowering mechanical wear and maintenance frequency. Furthermore, operating the heat pump with a significantly higher heat-source temperature would require a continuous supply of large amounts of waste heat from the generator. Such a condition can only be sustained during high generator loads, which would result in excessive overproduction of electrical energy—uneconomical if the household does not have sufficient electrical demand.

By maintaining a temperature of 15 °C in the thermal chamber during the heating season, the system operates both efficiently and economically, while also extending the service life of its components. During the summer and transitional periods, outdoor air temperatures exceed 15 °C; therefore, the heat pump will extract heat directly from outside air rather than from the chamber, which also ensures a high COP.

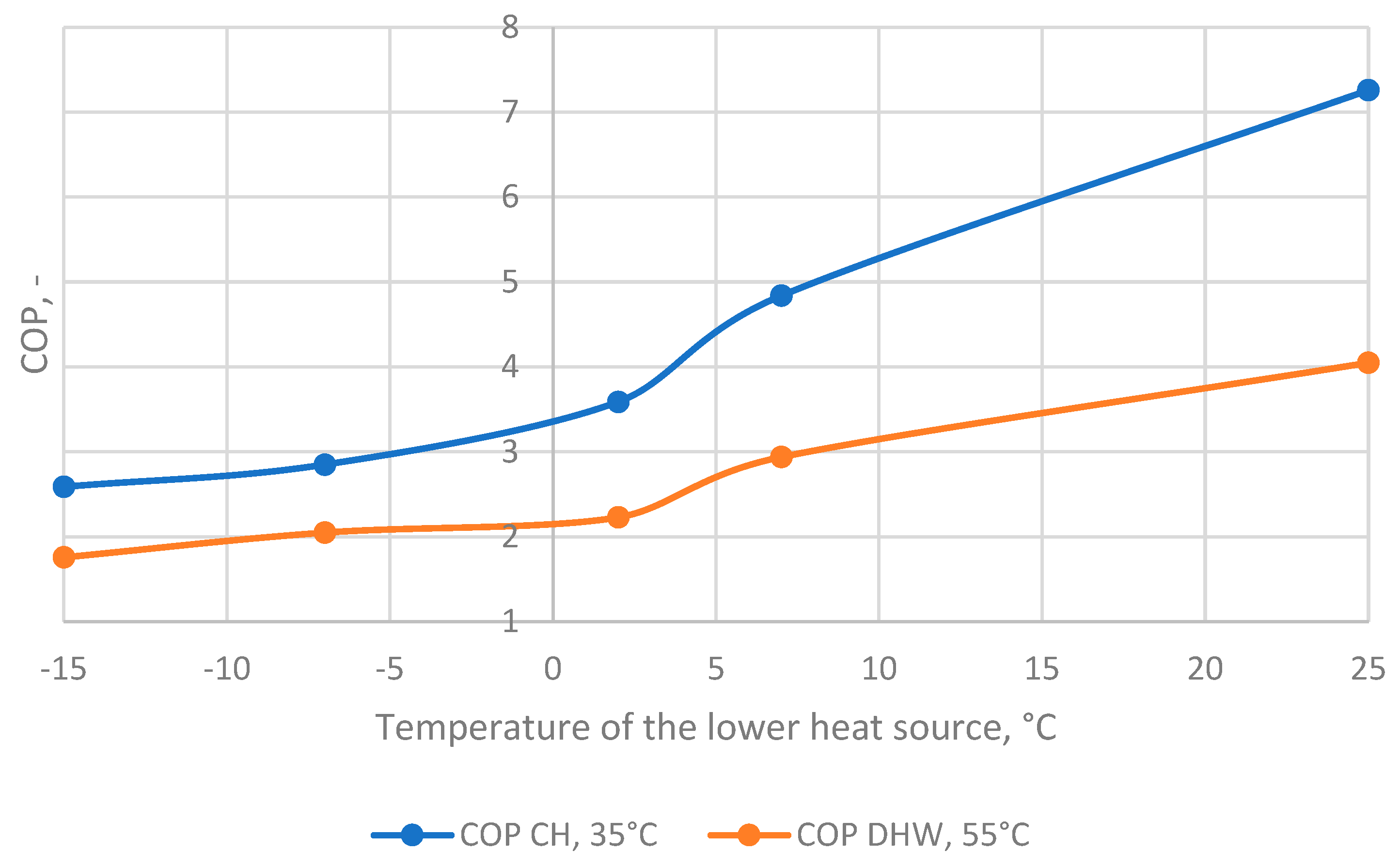

Figure 7 presents the COP characteristics of the heat pump for the space-heating and DHW circuits at different outdoor temperatures.

This plot illustrates the variation in heat pump performance as a function of the operating temperature. For the lower supply temperature required by the space-heating system (35 °C), the COP is higher, indicating more efficient energy use. Conversely, for the higher temperature required for domestic hot water preparation (55 °C), the COP is lower due to the increased energy demand. For the subsequent analyses, the relevant COP values are those corresponding to the average temperatures during the summer and transitional periods, as well as those for the heating season, assuming a heat-source temperature not lower than 15 °C. These values were approximated from the manufacturer’s performance chart. For example, during the heating season, the COP is approximately 6 for space heating (SH) at the operating point A15/W35, and approximately 3.5 for domestic hot water (DHW) production at the operating point A15/W55. Analogous COP values were determined for the summer period.

The daily amount of required heating capacity for domestic hot water preparation was calculated using the following formula:

where:

PDHW – required heating capacity for DHW preparation, kW

V – water tank capacity, 200 dm3

cw – specific heat of water, 4,2 kJ/kgK

ρ – water density for average water temperatures between 10°C and 55°C, 995,3 kg/m3

τw – time required to heat water in the tank, 2h

ΔT – the difference in temperature between cold and hot water, 45K

The time required to heat the water in the storage tank, τw, was assumed to be 2 hours, with two heating cycles per day: at 5:00 in the morning and at 20:00 in the evening. Therefore, for the purpose of calculating the heating capacity of the heat pump for domestic hot water (DHW) preparation, a value of 5.24 kW operating for 2 hours per day should be used. During this period, the heat pump does not supply heat to the space-heating system during the heating season, as DHW production has priority.

Table 3 presents the monthly data related to the domestic hot water heating system.

The annual heat demand for domestic hot water preparation amounts to 3,825 kWh.

In the case of space heating, the heat demand depends significantly on the outdoor temperature. The relationship below defines this dependence based on the maximum heating demand of 6 kW, as previously assumed, at the design outdoor temperature of 20°C for the selected location (Podkarpackie region, Poland). By introducing an additional boundary condition that marks the end of the heating season at an outdoor temperature of 16°C, the heat demand as a function of outdoor temperature can be expressed as follows:

where:

PCH(Tout) – heat demand for heating purposes, kW

Tout – outside temperature, °C

In

Table 4, the data related to the heat supply system for space heating are presented.

The seasonal heat demand during the heating period (from October to April) for space heating (CH) is 11,045 kWh. Outside the heating season (from May to September), the heat pump does not produce heat for space heating and operates solely to meet the demand for domestic hot water (DHW).

The analysis of these results makes it possible to assess the seasonal energy consumption and the operating costs of the heat pump, providing a basis for optimizing the operation of the system depending on the current demand for space heating and domestic hot water in the building.

For the correct selection of a generator set that will supply only the heat pump with a heating capacity of 7 kW, a traditional approach would require considering the electrical power demand of the heat pump under the most challenging outdoor conditions, i.e., at the bivalent temperature of -11°C. In the proposed solution, however, the heat pump should be sized according to the temperature of the low-temperature heat source, which is assumed to be 15°C inside the thermal chamber.

The coefficient of performance (COP) of the heat pump at the operating point A15/W55 (i.e., 15°C heat source and 55°C heat sink temperature for DHW production) is COP = 3.5. The COP at the operating point A15/W35 (i.e., 15°C heat source and 35°C heat sink temperature for CH) is COP = 6.

This means that in order to generate 6 kW of heating power for space heating or 5.24 kW for domestic hot water, the heat pump consumes 1 kW of electrical power for CH and 1.50 kW for DHW. It also follows that the heat pump must extract 5 kW of heat from the low-temperature source for CH, and 3.74 kW for DHW.

Considering only the heat pump’s electrical power demand, and in order to ensure stable operation of the generator while minimizing overload risk, a safety margin should be applied; therefore, the electrical power of the generator should be no less than approx. 2.0 kW. In case of excess generated electrical energy, the surplus may be stored in a battery system or used to cover domestic electrical loads. If the generator cannot supply the required electrical power, the system should allow the heat pump to be powered from the energy storage unit, ensuring uninterrupted operation, or alternatively from the electrical grid.

The heat generated by the generator (treated as waste heat) will be used to warm the thermal chamber housing the outdoor unit of the heat pump. In this manner, it will serve as the heat pump’s low-temperature heat source, ensuring stable operating conditions. Based on the measurements, approximately 28% of the energy produced by the generator can be recovered as heat originating from both engine thermal losses and a portion of the exhaust heat. Assuming an electrical efficiency of 30%, this means that 30% of the fuel energy becomes electrical output, while the remaining 42% constitutes unrecovered losses.

This represents a significant heat loss when compared with Sankey-based theoretical distributions, where up to 60% of the fuel energy should be recoverable, and only about 10% constitutes losses. Therefore, further calculations in this work consider three operating variants. Variant I reflects the experimentally obtained waste heat recovery efficiency of 28%. Variant II assumes an intermediate recovery efficiency of 45%, which may be realistically achievable after several improvements, such as enhanced thermal insulation of the chamber or a more efficient exhaust heat exchanger. Variant III corresponds to the theoretical Sankey assumptions, with a 60% waste heat recovery rate.

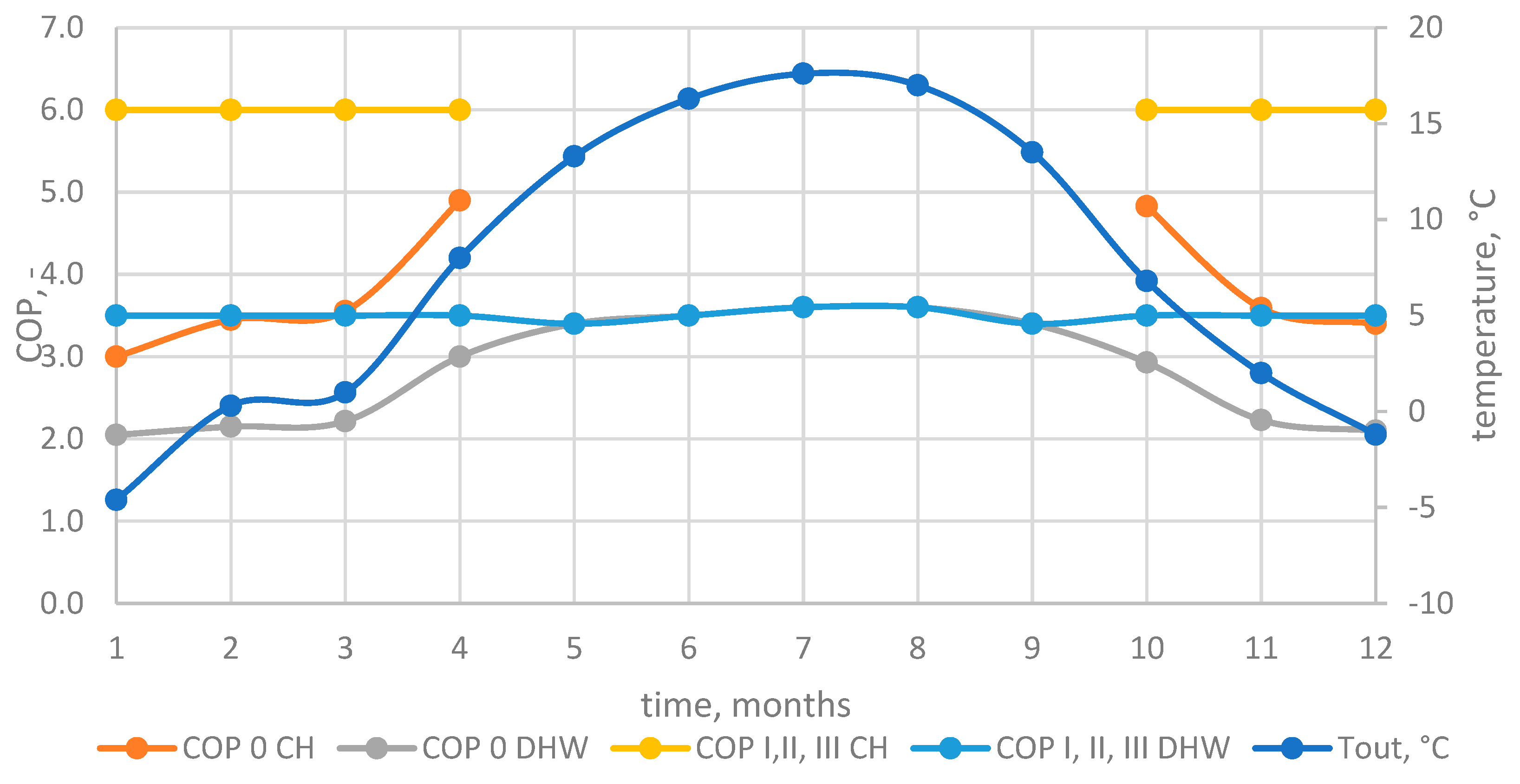

Variants I-III are additionally compared with Variant 0, in which the heat pump operates conventionally, meaning it is powered directly from the electrical grid and extracts heat from outdoor air. Consequently, the COP depends on the ambient temperature.

Figure 8 presents the COP values for each analyzed variant.

Based on the heat demand for space heating and domestic hot water preparation, as well as the corresponding COP values, the electrical energy demand was determined for each analyzed variant. The results for the individual variants are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

In each of the analyzed variants, the total annual heat demand remains the same at approximately 14 870 kWh, of which 11 046 kWh corresponds to space heating (CH) and 3 824 kWh to domestic hot water preparation (DHW). The differences between the variants relate to the consumption of electrical energy. In Variant 0, where the heat pump is powered by electricity from the grid and the temperature of the heat source depends directly on outdoor conditions, the total annual electricity consumption amounts to approximately 4,538 kWh (including 3 127 kWh for heating and 1 411 kWh for hot water preparation).

In Variants I–III, where the temperature of the low-temperature heat source is maintained at a constant 15°C using waste heat recovered from the generator set, the annual electricity consumption decreases to approximately 2 939 kWh (1 845 kWh for heating and 1 094 kWh for domestic hot water). This reduction results directly from the improved COP of the heat pump operating under stable thermal conditions.

Table 7 presents the input data used for further analysis in Variants I, II, and III. As mentioned earlier, these variants differ primarily in the efficiency of waste heat recovery from the generator set: Variant I assumes 28%, Variant II 45%, and Variant III 60%. The level of heat recovery directly determines the amount of electrical energy that the generator must produce, since the system’s priority is to supply sufficient heat to the thermal chamber to maintain the target temperature of 15°C. Consequently, in Variant I (characterized by the lowest recovery efficiency) the generator must operate longer or at a higher load to meet the thermal requirements of the chamber, resulting in higher fuel consumption compared to Variants II and III. These differences translate directly into the operating costs of the system, which are examined in detail in the subsequent part of the study.

The operating costs for Variant 0 result directly from the electricity consumption of the heat pump for space heating and domestic hot water preparation. An electricity price of 0.28 €/kWh was assumed for the analysis.

Table 8 presents the annual operating costs for Variant 0.

The total cost of space heating and domestic hot water preparation in Variant 0 amounts to 1 271 €/year.

To calculate the fuel consumption for Variants I-III, it was assumed that 1 liter of diesel fuel provides 10 kWh of chemical energy [

31,

32]. The generator set converts part of this energy into electricity and part into waste heat, which in the analyzed system is utilized as the low-temperature heat source for the heat pump.

In the calculations, the electrical efficiency of the generator was assumed to be 30%, while the efficiency of waste heat recovery depends on the considered variant and amounts to 28% (Variant I), 45% (Variant II), and 60% (Variant III).

The total amount of heat that must be supplied to the heat pump’s low-temperature source during the heating season was determined based on the energy balance of the heat pump, as the difference between the total heat delivered by the pump and the electrical energy consumed by the compressor. Then, knowing the recovery efficiency, the chemical energy of the fuel required to deliver this amount of heat was calculated using the following relation:

where:

Qfuel – chemical energy of fuel, kWh,

QL – heat from the lower heat source, kWh,

ηrec – heat recovery efficiency from the unit, %.

The low-temperature heat (Q

L) represents the amount of energy that the heat pump must extract from the environment (or, in this case, from the generator set) in order to deliver the required thermal output for space heating and domestic hot water preparation. The value of Q

L depends on the coefficient of performance (COP) and can be expressed as:

Next, the amount of fuel consumed was determined using the following formula:

The obtained result was then multiplied by the unit price of the fuel (1.40 €/l), which made it possible to determine the operational cost of the generator set.

The fuel consumption for the non-heating season was calculated in an analogous manner; however, in this case, heat recovery is not required. During the summer period, the generator operates solely to produce electricity necessary to supply the heat pump during domestic hot water preparation.

Table 9 presents the results for variants I-III. The designation X-IV refers to the results for the heating season (October to April), while V-IX refers to the results for the summer season (May to September).

As the efficiency of waste-heat recovery increases, a clear decrease in fuel consumption is observed. For Variant I, with a recovery efficiency of 28%, the annual diesel consumption (FC total) amounts to 4 007 liters, whereas for Variant II (45%) it decreases to 2 551 liters, and for Variant III (60%) it is reduced further to 1 952 liters. This corresponds to annual fuel costs (Ctotal) of 5 610 €, 3 571 €, and 2 733 €, respectively. At the same time, the amount of electrical energy generated by the generator set decreases with increasing heat recovery efficiency. Over the entire year, the total electrical energy production (Eel total) equals 12 020 kWh, 7 652 kWh, and 5 854 kWh for Variants I, II, and III, respectively. The amount of surplus electrical energy (Eel +) is 9 086 kWh in Variant I, 4 719 kWh in Variant II, and 2 920 kWh in Variant III.

These results indicate that the surplus electrical energy may significantly exceed the typical annual electricity consumption in a household for powering electrical appliances such as consumer electronics, home appliances, and lighting, which for a four-person household typically amounts to 3 000-4 000 kWh/year [

33,

34]. In Variant III, the surplus energy is comparable to this demand; in Variant II, it should fully cover it with some reserve; whereas in Variant I, the surplus remains substantially higher. Detailed planning of how to utilize the excess energy— including the analysis of self-consumption strategies, the use of energy storage systems, and potential export of energy to the grid—lies beyond the scope of this study and will be the subject of future research.

The analysis of four operating variants of the system, a conventional configuration (Variant 0) and three configurations with waste-heat recovery (Variants I-III), revealed clear differences both in operating costs and in the overall energy performance of the system. Variant 0, in which the heat pump operates under traditional conditions and is supplied with electricity from the grid, is characterized by the lowest unit cost of energy but also by the highest electricity consumption, resulting from operation at variable and often low outdoor air temperatures.

The remaining variants are significantly more expensive to operate than the baseline Variant 0. In Variants I-III, the dominant cost factor is the fuel consumed by the generator set. However, it should be emphasized that these variants generate substantial amounts of surplus electrical energy, demonstrating that the system can cover not only the heat pump’s demand but also a considerable portion, and in some configurations even the entirety, of the household’s electrical consumption. On the other hand, this surplus requires appropriate management, for example through the use of energy storage systems, electric heaters for additional water heating, or control strategies aimed at increasing on-site self-consumption. These aspects were not the subject of detailed analysis at this stage of the research. Among the configurations with waste-heat recovery, Variant III is the most economical, with an annual cost of 2 733 €, which is the closest to the cost of the conventional Variant 0 (1 271 €), while at the same time providing full independence from the electrical grid.