Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

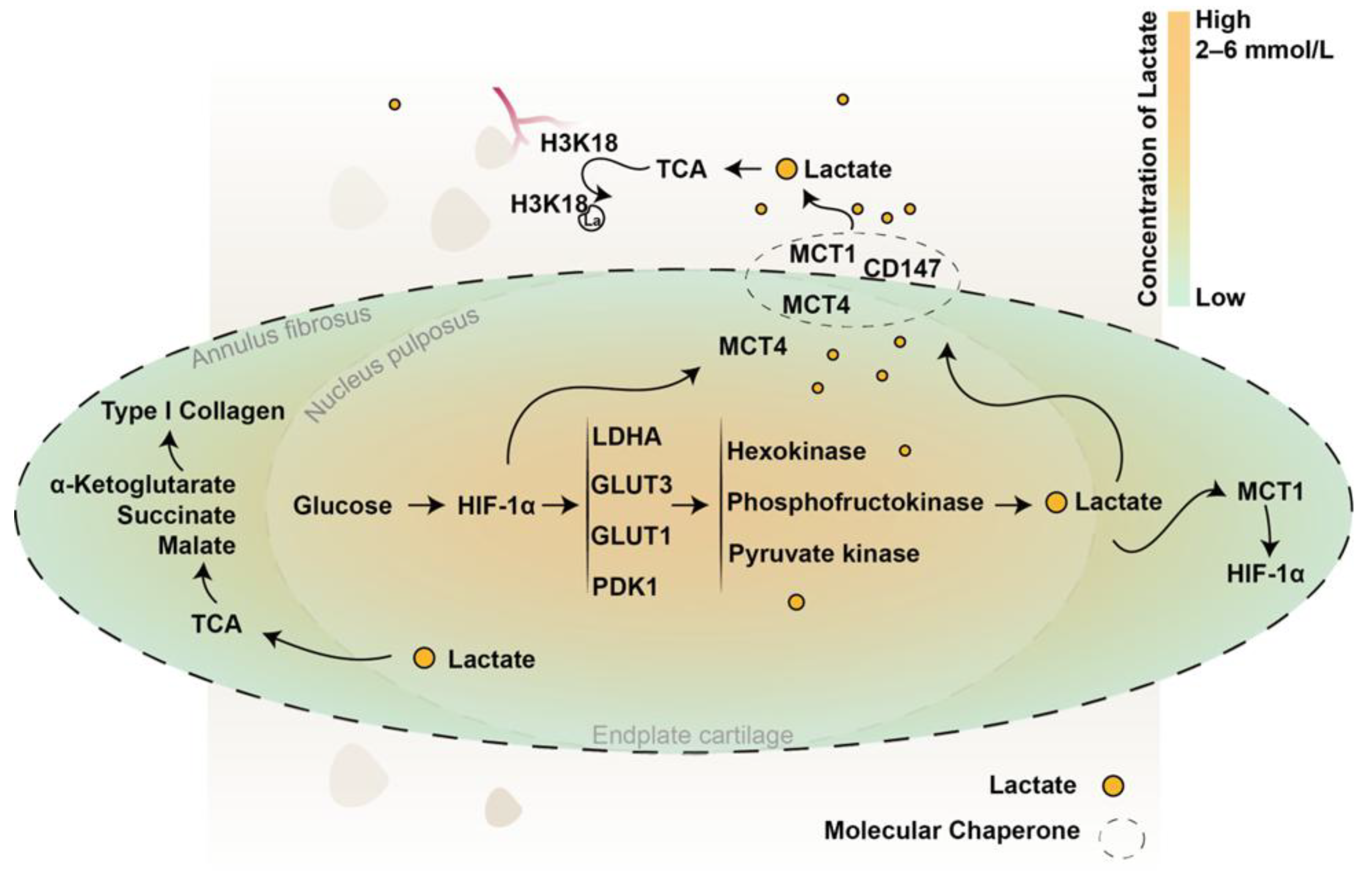

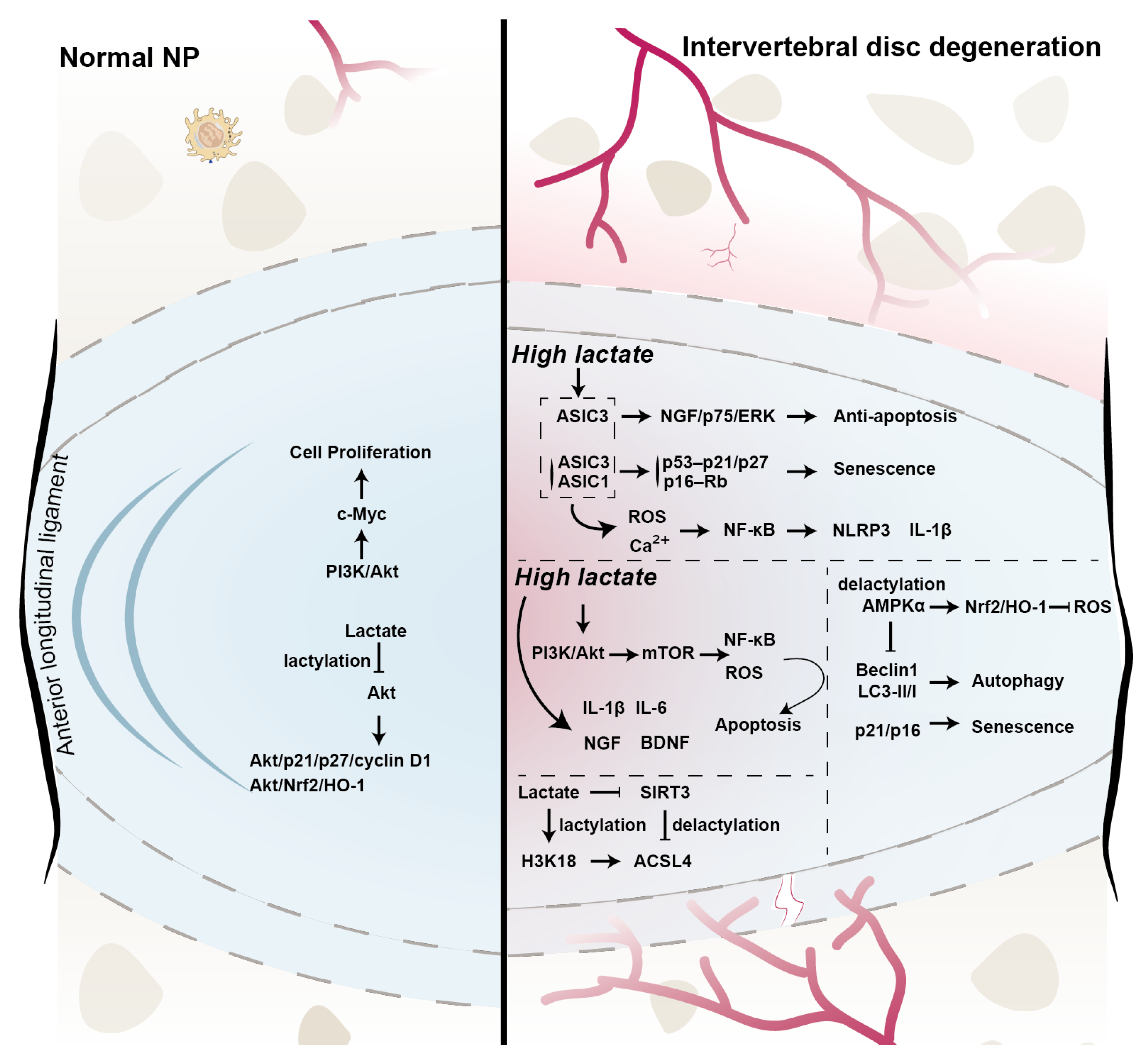

2. IVD Lactate Production

3. IVD Lactate Transport, Accumulation, and Clearance

4. New Roles of Lactate in IVD

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

| ACAN | Aggrecan |

| AF | Annulus fibrosus |

| ASICs | Acid-sensing ion channels |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| B2R | B2 receptor |

| CBX3 | Chromobox protein homolog 3 |

| CEP | Cartilage endplate |

| CEPCs | Cartilage endplate progenitor cells |

| CD147 | Cluster of differentiation 147 |

| CEST | Chemical exchange saturation transfer |

| c-Myc | Cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene |

| COL2A1 | Collagen type II alpha 1 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| EAE | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ECAR | Extracellular acidification rate |

| EMMPRIN | Matrix metalloproteinase inducer |

| EPs | Endplate chondrocytes |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead Box Protein O1 |

| FRDEGs | Ferroptosis-related differentially expressed genes |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| GLUT3 | Glucose transporter 3 |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GAG | Glycosaminoglycan |

| GPR81 | G protein–coupled receptor 81 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| G6P | Glucose-6-phosphate |

| H3K18 | Histone H3 lysine 18 |

| HDACs | Histone deacetylases |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 alpha |

| IVD | Intervertebral disc |

| IDD | Intervertebral disc degeneration |

| IAF | Inner annulus fibrosus |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| Kla | Lysine lactylation |

| Kac | Lysine acetylation |

| K310 | Lysine 310 |

| KATs | Lysine acetyltransferases |

| LBP | Low back pain |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A |

| LDHB | Lacate dehydrogenase B |

| LDH5 | Lactate dehydrogenase 5 |

| LOx | Lactate oxidase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LRGs | Lactylation-related genes |

| MCT | Monocarboxylate transporter |

| MMP3 | Matrix metalloproteinase 3 |

| MMP2 | Matrix metalloproteinase 2 |

| MMP9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| MMP13 | Matrix metalloproteinase 13 |

| MRS | Magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| NP | Nucleus pulposus |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NAD⁺ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| OAF | Outer annulus fibrosus |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase / Protein kinase B |

| pan-Kla | Global lysine lactylation |

| PDK1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| PC | Pyruvate carboxylase |

| PH | Pleckstrin homology |

| p75NTR | p75 neurotrophin receptor |

| p53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| p21 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| p27 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B |

| p16 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| RCD | Regulated cell death |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SLC16A3 | Solute Carrier Family 16 Member 3 |

| SIRT3 | Sirtuin 3 |

| S536 | Serine 536 |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| TBHP | Tert-butyl hydroperoxide |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| TZ | Transition zone |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

References

- Murray, C. J.; et al. The state of US health, 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013, 310, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livshits, G.; Popham, M.; Malkin, I.; Sambrook, P.N.; Macgregor, A.J.; Spector, T.; Williams, F.M. Lumbar disc degeneration and genetic factors are the main risk factors for low back pain in women: the UK Twin Spine Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011, 70, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Chu, G.; Yu, Z.; Ji, Z.; Kong, F.; Yao, L.; Wang, J.; Geng, D.; Wu, X.; Mao, H. The role of ferroptosis in intervertebral disc degeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1219840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattappa, G.; Li, Z.; Peroglio, M.; Wismer, N.; Alini, M.; Grad, S. Diversity of intervertebral disc cells: phenotype and function. J Anat 2012, 221, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silagi, E.S.; Novais, E.J.; Bisetto, S.; Telonis, A.G.; Snuggs, J.; Le Maitre, C.L.; Qiu, Y.; Kurland, I.J.; Shapiro, I.M.; Philp, N.J.; et al. Lactate Efflux From Intervertebral Disc Cells Is Required for Maintenance of Spine Health. J Bone Miner Res 2020, 35, 550–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silagi, E.S.; Schipani, E.; Shapiro, I.M.; Risbud, M.V. The role of HIF proteins in maintaining the metabolic health of the intervertebral disc. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021, 17, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Chen, P.; Reeves, R.A.; Buchweitz, N.; Niu, H.; Gong, H.; Mercuri, J.; Reitman, C.A.; Yao, H.; Wu, Y. Diffusivity of Human Cartilage Endplates in Healthy and Degenerated Intervertebral Disks. J Biomech Eng 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshima, H.; Urban, J.P. The effect of lactate and pH on proteoglycan and protein synthesis rates in the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1992, 17, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpa, B.T.; Rajasekaran, S.; Easwaran, M.; Murugan, C.; Algeri, R.; Sri Vijay Anand, K.S.; Mugesh Kanna, R.; Shetty, A.P. ISSLS PRIZE in basic science 2023: Lactate in lumbar discs-metabolic waste or energy biofuel? Insights from in vivo MRS and T2r analysis following exercise and nimodipine in healthy volunteers. Eur Spine J 2023, 32, 1491–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Liang, H.; Du, Z.; Liu, Q.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Wu, D.; Zhou, X.; Song, Y.; Yang, C. Altered Metabolism and Inflammation Driven by Post-translational Modifications in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Research 2024, 7, 0350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hartman, R.; Han, C.; Zhou, C.M.; Couch, B.; Malkamaki, M.; Roginskaya, V.; Van Houten, B.; Mullett, S.J.; Wendell, S.G.; et al. Lactate oxidative phosphorylation by annulus fibrosus cells: evidence for lactate-dependent metabolic symbiosis in intervertebral discs. Arthritis Res Ther 2021, 23, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faubert, B.; Li, K.Y.; Cai, L.; Hensley, C.T.; Kim, J.; Zacharias, L.G.; Yang, C.; Do, Q.N.; Doucette, S.; Burguete, D.; et al. Lactate Metabolism in Human Lung Tumors. Cell 2017, 171, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Morscher, R.J.; Jang, C.; Teng, X.; Lu, W.; Esparza, L.A.; Reya, T.; Le, Z.; Yanxiang Guo, J.; et al. Glucose feeds the TCA cycle via circulating lactate. Nature 2017, 551, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A.; Curl, C.C.; Leija, R.G.; Osmond, A.D.; Duong, J.J.; Arevalo, J.A. Tracing the lactate shuttle to the mitochondrial reticulum. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54, 1332–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsingas, M.; Tsingas, K.; Zhang, W.; Goldman, A.R.; Risbud, M.V. Lactate metabolic coupling between the endplates and nucleus pulposus via MCT1 is essential for intervertebral disc health. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.F.; Wang, G.; Ding, L.; Bai, Z.R.; Leng, Y.; Tian, J.W.; Zhang, J.Z.; Li, Y.Q.; Ahmad; Qin, Y.H.; et al. Lactate-upregulated NADPH-dependent NOX4 expression via HCAR1/PI3K pathway contributes to ROS-induced osteoarthritis chondrocyte damage. Redox Biol 2023, 67, 102867. [CrossRef]

- Manosalva, C.; Quiroga, J.; Hidalgo, A.I.; Alarcon, P.; Anseoleaga, N.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Burgos, R.A. Role of Lactate in Inflammatory Processes: Friend or Foe. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 808799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Xu, Z.G.; Tu, H.; Hu, F.; Dai, J.; Chang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, H.; et al. Lactate Is a Natural Suppressor of RLR Signaling by Targeting MAVS. Cell 2019, 178, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, N.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, Q.; Cong, X. Lactylation: the novel histone modification influence on gene expression, protein function, and disease. Clin Epigenetics 2024, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Mang, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, X.; Tong, Z.; Yang, Q.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.; et al. Histone Lactylation Boosts Reparative Gene Activation Post-Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res 2022, 131, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, T.; Yin, H.; Gao, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Jin, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell 2024, 187, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S.; Maroudas, A.; Urban, J.P.; Selstam, G.; Nachemson, A. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc: solute transport and metabolism. Connect Tissue Res 1981, 8, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; Smith, S.; Fairbank, J.C. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004, 29, 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffosse, J.M.; Accadbled, F.; Molinier, F.; Bonnevialle, N.; de Gauzy, J.S.; Swider, P. Correlations between effective permeability and marrow contact channels surface of vertebral endplates. J Orthop Res 2010, 28, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; Holm, S.; Maroudas, A.; Nachemson, A. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc: effect of fluid flow on solute transport. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.M.; Hargens, A.R.; Garfin, S.R. Intervertebral disc nutrition. Diffusion versus convection. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.J.; Ito, K.; Nolte, L.P. Fluid flow and convective transport of solutes within the intervertebral disc. J Biomech 2004, 37, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Menage, J.; Urban, J.P. Biochemical and structural properties of the cartilage end-plate and its relation to the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989, 14, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, E.M.; Fairbank, J.C.; Winlove, C.P.; Urban, J.P. Oxygen and lactate concentrations measured in vivo in the intervertebral discs of patients with scoliosis and back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, A.G.; Schaaf, R.; Walchli, B.; Boos, N. Temporo-spatial distribution of blood vessels in human lumbar intervertebral discs. Eur Spine J 2007, 16, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunhagen, T.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Fairbank, J.C.; Urban, J.P. Intervertebral disk nutrition: a review of factors influencing concentrations of nutrients and metabolites. Orthop Clin North Am 2011, 42, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, D.; Grad, S. Advancing the cellular and molecular therapy for intervertebral disc disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015, 84, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachemson, A.; Lewin, T.; Maroudas, A.; Freeman, M.A. In vitro diffusion of dye through the end-plates and the annulus fibrosus of human lumbar inter-vertebral discs. Acta Orthop Scand 1970, 41, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroudas, A.; Stockwell, R.A.; Nachemson, A.; Urban, J. Factors involved in the nutrition of the human lumbar intervertebral disc: cellularity and diffusion of glucose in vitro. J Anat 1975, 120, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, J.P.; Holm, S.; Maroudas, A. Diffusion of small solutes into the intervertebral disc: as in vivo study. Biorheology 1978, 15, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Urban, J.P.; Evans, H.; Eisenstein, S.M. Transport properties of the human cartilage endplate in relation to its composition and calcification. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996, 21, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horner, H.A.; Urban, J.P. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Basic Science Studies: Effect of nutrient supply on the viability of cells from the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001, 26, 2543–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalash, W.; Ahrens, S.R.; Bardonova, L.A.; Byvaltsev, V.A.; Giers, M.B. Patient-specific apparent diffusion maps used to model nutrient availability in degenerated intervertebral discs. JOR Spine 2021, 4, e1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comandatore, A.; Franczak, M.; Smolenski, R.T.; Morelli, L.; Peters, G.J.; Giovannetti, E. Lactate Dehydrogenase and its clinical significance in pancreatic and thoracic cancers. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Xu, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.T.; Wang, J.; Chen, G.F.; Chen, W.B.; Liu, J.; Huang, G.B.; Sun, W.J.; et al. Astrocytic lactate dehydrogenase A regulates neuronal excitability and depressive-like behaviors through lactate homeostasis in mice. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.B.; Urban, J.P. Evidence for a negative Pasteur effect in articular cartilage. Biochem J 1997, 321 Pt 1, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, S.R.; Jones, D.A.; Ripley, R.M.; Urban, J.P. Metabolism of the intervertebral disc: effects of low levels of oxygen, glucose, and pH on rates of energy metabolism of bovine nucleus pulposus cells. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoulet, M.; Bouchez, C.L.; Paumard, P.; Ransac, S.; Cuvellier, S.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Mazat, J.P.; Devin, A. Cell energy metabolism: An update. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2020, 1861, 148276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavricka, J.; Broz, P.; Follprecht, D.; Novak, J.; Krouzecky, A. Modern Perspective of Lactate Metabolism. Physiol Res 2024, 73, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Gao, X.; Levene, H.B.; Brown, M.D.; Gu, W. Influences of Nutrition Supply and Pathways on the Degenerative Patterns in Human Intervertebral Disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016, 41, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.; Guttapalli, A.; Narayan, S.; Albert, T.J.; Shapiro, I.M.; Risbud, M.V. Normoxic stabilization of HIF-1alpha drives glycolytic metabolism and regulates aggrecan gene expression in nucleus pulposus cells of the rat intervertebral disk. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007, 293, C621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Liu, Z.; Yao, J.; Huang, S.; Ding, X.; Yu, H.; Lin, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, F. HIF-1alpha regulated GLUT1-mediated glycolysis enhances Treponema pallidum-induced cytokine responses. Cell Commun Signal 2025, 23, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risbud, M.V.; Schipani, E.; Shapiro, I.M. Hypoxic regulation of nucleus pulposus cell survival: from niche to notch. Am J Pathol 2010, 176, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Kong, D.; Zhang, X.; Xia, S.; Liang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, J.; et al. Canonical Wnt signaling promotes HSC glycolysis and liver fibrosis through an LDH-A/HIF-1alpha transcriptional complex. Hepatology 2024, 79, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierans, S.J.; Taylor, C.T. Regulation of glycolysis by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF): implications for cellular physiology. J Physiol 2021, 599, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukane, D.M.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Urban, J.P. Computation of coupled diffusion of oxygen, glucose and lactic acid in an intervertebral disc. J Biomech 2007, 40, 2645–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Nunes, A.; Simoes-Sousa, S.; Pinheiro, C.; Miranda-Goncalves, V.; Granja, S.; Baltazar, F. Targeting lactate production and efflux in prostate cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2020, 1866, 165894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonglack, E.N.; Messinger, J.E.; Cable, J.M.; Ch'ng, J.; Parnell, K.M.; Reinoso-Vizcaino, N.M.; Barry, A.P.; Russell, V.S.; Dave, S.S.; Christofk, H.R.; et al. Monocarboxylate transporter antagonism reveals metabolic vulnerabilities of viral-driven lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdzik, M.; Szelag-Pieniek, S.; Grzegolkowska, J.; Lapczuk-Romanska, J.; Post, M.; Domagala, P.; Mietkiewski, J.; Oswald, S.; Kurzawski, M. Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 (MCT1) in Liver Pathology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Narumi, K.; Furugen, A.; Iseki, K. Transport function, regulation, and biology of human monocarboxylate transporter 1 (hMCT1) and 4 (hMCT4). Pharmacol Ther 2021, 226, 107862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, A.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, H.; Lei, J.; Yan, C. Structural basis of human monocarboxylate transporter 1 inhibition by anti-cancer drug candidates. Cell 2021, 184, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Afonso, J.; Sharma, D.; Gupta, R.; Kumar, V.; Rani, R.; Baltazar, F.; Kumar, V. Targeting monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) in cancer: How close are we to the clinics? Semin Cancer Biol 2023, 90, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Aria, S.; Maquet, C.; Li, S.; Dhup, S.; Lepez, A.; Kohler, A.; Van Hee, V.F.; Dadhich, R.K.; Freniere, M.; Andris, F.; et al. Expression of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 is required for virus-specific mouse CD8(+) T cell memory development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2306763121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, P.; Wilson, M.C.; Heddle, C.; Brown, M.H.; Barclay, A.N.; Halestrap, A.P. CD147 is tightly associated with lactate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 and facilitates their cell surface expression. EMBO J 2000, 19, 3896–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.K.; Arendt, B.K.; Jelinek, D.F. CD147 regulates the expression of MCT1 and lactate export in multiple myeloma cells. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3175–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovenzi, C.D.; Hamilton, J.; Tassone, P.; Johnson, J.; Cognetti, D.M.; Luginbuhl, A.; Keane, W.M.; Zhan, T.; Tuluc, M.; Bar-Ad, V.; et al. Prognostic Indications of Elevated MCT4 and CD147 across Cancer Types: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 242437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Sorensen, E.E.; Ponniah, M.; Thorlacius-Ussing, J.; Crouigneau, R.; Larsen, T.; Borre, M.T.; Willumsen, N.; Flinck, M.; Pedersen, S.F. MCT4 and CD147 colocalize with MMP14 in invadopodia and support matrix degradation and invasion by breast cancer cells. J Cell Sci 2024, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.E.; Murray, A.B.; Lomelino, C.L.; Mboge, M.Y.; Mietzsch, M.; Horenstein, N.A.; Frost, S.C.; McKenna, R.; Becker, H.M. Disruption of the Physical Interaction Between Carbonic Anhydrase IX and the Monocarboxylate Transporter 4 Impacts Lactate Transport in Breast Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Kong, Z.; Miao, J.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Y.; Zeng, L. Emerging roles of lactate in acute and chronic inflammation. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halestrap, A.P. Monocarboxylic acid transport. Compr Physiol 2013, 3, 1611–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, V.L.; Mina, E.; Van Hee, V.F.; Porporato, P.E.; Sonveaux, P. Monocarboxylate transporters in cancer. Mol Metab 2020, 33, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Baeza, Y.; Sandoval, P.Y.; Alarcon, R.; Galaz, A.; Cortes-Molina, F.; Alegria, K.; Baeza-Lehnert, F.; Arce-Molina, R.; Guequen, A.; Flores, C.A.; et al. Monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4) is a high affinity transporter capable of exporting lactate in high-lactate microenvironments. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 20135–20147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Tchernyshyov, I.; Semenza, G.L.; Dang, C.V. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab 2006, 3, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Davies, A.J.; Halestrap, A.P. The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is up-regulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1alpha-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 9030–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsorno, K.; Ginggen, K.; Ivanov, A.; Buckinx, A.; Lalive, A.L.; Tchenio, A.; Benson, S.; Vendrell, M.; D'Alessandro, A.; Beule, D.; et al. Loss of microglial MCT4 leads to defective synaptic pruning and anxiety-like behavior in mice. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Hsieh, M.K.; Hu, Y.J.; Bit, A.; Lai, P.L. Monocarboxylate transporter 1-mediated lactate accumulation promotes nucleus pulposus degeneration under hypoxia in a 3D multilayered nucleus pulposus degeneration model. Eur Cell Mater 2022, 43, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmarco, L.M.; Rone, J.M.; Polonio, C.M.; Fernandez Lahore, G.; Giovannoni, F.; Ferrara, K.; Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Li, N.; Sokolovska, A.; Plasencia, A.; et al. Lactate limits CNS autoimmunity by stabilizing HIF-1alpha in dendritic cells. Nature 2023, 620, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junger, S.; Gantenbein-Ritter, B.; Lezuo, P.; Alini, M.; Ferguson, S.J.; Ito, K. Effect of limited nutrition on in situ intervertebral disc cells under simulated-physiological loading. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009, 34, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malandrino, A.; Noailly, J.; Lacroix, D. The effect of sustained compression on oxygen metabolic transport in the intervertebral disc decreases with degenerative changes. PLoS Comput Biol 2011, 7, e1002112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Tan, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhou, S.; Luo, F.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, B.; et al. Inhibition of aberrant Hif1alpha activation delays intervertebral disc degeneration in adult mice. Bone Res 2022, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benneker, L.M.; Heini, P.F.; Alini, M.; Anderson, S.E.; Ito, K. 2004 Young Investigator Award Winner: vertebral endplate marrow contact channel occlusions and intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristova, G.I.; Jarzem, P.; Ouellet, J.A.; Roughley, P.J.; Epure, L.M.; Antoniou, J.; Mwale, F. Calcification in human intervertebral disc degeneration and scoliosis. J Orthop Res 2011, 29, 1888–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Videman, T.; Battie, M.C. Lumbar vertebral endplate lesions: prevalence, classification, and association with age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012, 37, 1432–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Cisewski, S.E.; Wegner, N.; Zhao, S.; Pellegrini, V.D., Jr.; Slate, E.H.; Yao, H. Region and strain-dependent diffusivities of glucose and lactate in healthy human cartilage endplate. J Biomech 2016, 49, 2756–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Gu, W.Y. Effects of mechanical compression on metabolism and distribution of oxygen and lactate in intervertebral disc. J Biomech 2008, 41, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, J.; Ding, T.; Chen, H.; Wan, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W. HIF-1alpha protects nucleus pulposus cells from oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial impairment through PDK-1. Free Radic Biol Med 2024, 224, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z. LDHA-Mediated Glycolytic Metabolism in Nucleus Pulposus Cells Is a Potential Therapeutic Target for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 9914417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; An, R.; Xiang, Q.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Song, Y.; Liao, Z.; Li, S.; Hua, W.; Feng, X.; et al. Acid-sensing ion channels regulate nucleus pulposus cell inflammation and pyroptosis via the NLRP3 inflammasome in intervertebral disc degeneration. Cell Prolif 2021, 54, e12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trone, M.A.R.; Stover, J.D.; Almarza, A.; Bowles, R.D. pH: A major player in degenerative intervertebral disks. JOR Spine 2024, 7, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, H.T.J.; Hodson, N.; Baird, P.; Richardson, S.M.; Hoyland, J.A. Acidic pH promotes intervertebral disc degeneration: Acid-sensing ion channel -3 as a potential therapeutic target. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 37360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, S.; Wilkins, R.J.; Urban, J.P. The effect of extracellular pH on matrix turnover by cells of the bovine nucleus pulposus. Eur Spine J 2003, 12, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadala, G.; Ambrosio, L.; Russo, F.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V. Interaction between Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Intervertebral Disc Microenvironment: From Cell Therapy to Tissue Engineering. Stem Cells Int 2019, 2019, 2376172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, N.V.; Hartman, R.A.; Patil, P.R.; Risbud, M.V.; Kletsas, D.; Iatridis, J.C.; Hoyland, J.A.; Le Maitre, C.L.; Sowa, G.A.; Kang, J.D. Molecular mechanisms of biological aging in intervertebral discs. J Orthop Res 2016, 34, 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, P.; Du, Y.; Hecker, P.; Zhou, S.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cartilage Endplate-Targeted Engineered Exosome Releasing and Acid Neutralizing Hydrogel Reverses Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Adv Healthc Mater 2025, 14, e2403315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, A.H.; Twomey, J.D. Cellular mechanobiology of the intervertebral disc: new directions and approaches. J Biomech 2010, 43, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, W.M.; Hood, K.E. The cellular and molecular biology of the intervertebral disc: A clinician's primer. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2014, 58, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.J.; Fazzalari, N.L. The elastic fibre network of the human lumbar anulus fibrosus: architecture, mechanical function and potential role in the progression of intervertebral disc degeneration. Eur Spine J 2009, 18, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaeipoueinak, M.; Mordechai, H.S.; Bangar, S.S.; Sharabi, M.; Tipper, J.L.; Tavakoli, J. Structure-function characterization of the transition zone in the intervertebral disc. Acta Biomater 2023, 160, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; Maroudas, A. Swelling of the intervertebral disc in vitro. Connect Tissue Res 1981, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; McMullin, J.F. Swelling pressure of the lumbar intervertebral discs: influence of age, spinal level, composition, and degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Justiz, M.A.; Flagler, D.; Gu, W.Y. Effects of swelling pressure and hydraulic permeability on dynamic compressive behavior of lumbar annulus fibrosus. Ann Biomed Eng 2002, 30, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.; Maroudas, A.; Bayliss, M.T.; Dillon, J. Swelling pressures of proteoglycans at the concentrations found in cartilaginous tissues. Biorheology 1979, 16, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, B.A.; Guilak, F.; Setton, L.A.; Zhu, W.; Saed-Nejad, F.; Ratcliffe, A.; Weidenbaum, M.; Mow, V.C. Compressive mechanical properties of the human anulus fibrosus and their relationship to biochemical composition. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994, 19, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.Y.; Mao, X.G.; Foster, R.J.; Weidenbaum, M.; Mow, V.C.; Rawlins, B.A. The anisotropic hydraulic permeability of human lumbar anulus fibrosus. Influence of age, degeneration, direction, and water content. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999, 24, 2449–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perie, D.; Korda, D.; Iatridis, J.C. Confined compression experiments on bovine nucleus pulposus and annulus fibrosus: sensitivity of the experiment in the determination of compressive modulus and hydraulic permeability. J Biomech 2005, 38, 2164–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selard, E.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Urban, J.P. Finite element study of nutrient diffusion in the human intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003, 28, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukane, D.M.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Urban, J.P. Analysis of nonlinear coupled diffusion of oxygen and lactic acid in intervertebral discs. J Biomech Eng 2005, 127, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, F.; Afonso, J.; Costa, M.; Granja, S. Lactate Beyond a Waste Metabolite: Metabolic Affairs and Signaling in Malignancy. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. The lactate shuttle during exercise and recovery. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1986, 18, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A. Lactate production under fully aerobic conditions: the lactate shuttle during rest and exercise. Fed Proc 1986, 45, 2924–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S. Lactate Shuttles in Neuroenergetics-Homeostasis, Allostasis and Beyond. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G.A. Cell-cell and intracellular lactate shuttles. J Physiol 2009, 587, 5591–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karchevskaya, A.E.; Poluektov, Y.M.; Korolishin, V.A. Understanding Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Background Factors and the Role of Initial Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Zhao, X.J.; Du, Y.; Dong, Y.; Song, X.; Zhu, Y. Lipid metabolic disorders and their impact on cartilage endplate and nucleus pulposus function in intervertebral disk degeneration. Front Nutr 2025, 12, 1533264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, B.; Liu, L.T.; Liu, M.H.; Wang, J.; Li, C.Q.; Zhang, Z.F.; Chu, T.W.; Xiong, C.J. Utilization of stem cells in alginate for nucleus pulposus tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 2014, 20, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Deng, X.; Shi, D.; Wu, F.; Liang, H.; Huang, D.; Shao, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect Nucleus Pulposus Cells from Compression-Induced Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Mitochondrial Pathway. Stem Cells Int 2017, 2017, 9843120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Deng, G.; Ma, J.; Huang, X.; Yu, J.; Xi, Y.; Ye, X. Transplantation of Hypoxic-Preconditioned Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Retards Intervertebral Disc Degeneration via Enhancing Implanted Cell Survival and Migration in Rats. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 7564159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Fu, H.; Mao, D.; Chen, W.; Lan, L.; Wang, C.; Hu, K.; et al. NBS1 lactylation is required for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature 2024, 631, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Sun, S.; Zhang, P.; Luo, Z.; Feng, T.; Cui, Z.; Zhu, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Lactylation of METTL16 promotes cuproptosis via m(6)A-modification on FDX1 mRNA in gastric cancer. Nature communications 2023, 14, 6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raychaudhuri, D.; Singh, P.; Chakraborty, B.; Hennessey, M.; Tannir, A.J.; Byregowda, S.; Natarajan, S.M.; Trujillo-Ocampo, A.; Im, J.S.; Goswami, S. Histone lactylation drives CD8(+) T cell metabolism and function. Nature immunology 2024, 25, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Che, Y.; Gao, C.; Zhu, L.; Gao, J.; Vo, N.V. Immune exposure: how macrophages interact with the nucleus pulposus. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1155746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Li, F.; Lin, W.; Han, L.; Wang, J.; Yan, C.; Sun, J.; Ji, C.; Shi, J.; Sun, K. Integrating Bulk RNA and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Identifies and Validates Lactylation-Related Signatures for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e70262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, J.; Xiang, T.; Xu, H.; Zhou, X.; Wei, K.; Dai, J. Systematic analysis of lysine lactylation in nucleus pulposus cells. iScience 2024, 27, 111157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Han, W.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Qin, T.; Zhang, C.; Shi, M.; Han, S.; Gao, B.; et al. Glutamine suppresses senescence and promotes autophagy through glycolysis inhibition-mediated AMPKalpha lactylation in intervertebral disc degeneration. Communications biology 2024, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.M.; Cole, P.A. Targeting lysine acetylation readers and writers. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.F.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, L.Z.; Lv, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Yu, F.L.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, T.Y.; Xin, F.; et al. Sirt1 blocks nucleus pulposus and macrophages crosstalk by inhibiting RelA/Lipocalin 2 axis. J Orthop Translat 2025, 50, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsetti, A.; Illi, B.; Gaetano, C. How epigenetics impacts on human diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2023, 114, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, H.; Qin, J.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xian, C.J.; Miao, D.; et al. p16 deficiency attenuates intervertebral disc degeneration by adjusting oxidative stress and nucleus pulposus cell cycle. eLife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.J.; Shi, P.L.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Wu, X.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Wang, C.; Lu, J. Preclinical development of a microRNA-based therapy for intervertebral disc degeneration. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Lin, X.; Dong, W.; Huang, W.; Jiang, W.; Lin, L.; Qiu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Song, Z.; et al. SIRT1 alleviates senescence of degenerative human intervertebral disc cartilage endo-plate cells via the p53/p21 pathway. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 22628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, P.; Watson, B.; Toci, M.; Tran, V.A.; Johnston, S.; Tsingas, M.; Barve, R.A.; Mitra, R.; Loeser, R.F.; Collins, J.A.; et al. Sirt6 deficiency promotes senescence and age-associated intervertebral disc degeneration in mice. Bone Res 2025, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Bian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, G.; Li, G. Metformin activates AMPK/SIRT1/NF-kappaB pathway and induces mitochondrial dysfunction to drive caspase3/GSDME-mediated cancer cell pyroptosis. Cell cycle 2020, 19, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, P.; Cao, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Su, H.; Nashun, B. Hypoxic in vitro culture reduces histone lactylation and impairs pre-implantation embryonic development in mice. Epigenetics Chromatin 2021, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Lv, X.; Thompson, E.W.; Ostrikov, K.K. Histone lactylation: epigenetic mark of glycolytic switch. Trends Genet 2022, 38, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Yruela, C.; Zhang, D.; Wei, W.; Baek, M.; Liu, W.; Gao, J.; Dankova, D.; Nielsen, A.L.; Bolding, J.E.; Yang, L.; et al. Class I histone deacetylases (HDAC1-3) are histone lysine delactylases. Sci Adv 2022, 8, eabi6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Fan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tu, F.; Gill, P.S.; Ha, T.; Liu, L.; Williams, D.L.; et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhou, X. Lactylation, an emerging hallmark of metabolic reprogramming: Current progress and open challenges. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 972020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Hu, H.; Liu, M.; Zhou, T.; Cheng, X.; Huang, W.; Cao, L. The role and mechanism of histone lactylation in health and diseases. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 949252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Ding, L. Effects of lactylation on the hallmarks of cancer (Review). Oncol Lett 2025, 30, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellen, K.E.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; Sachdeva, U.M.; Bui, T.V.; Cross, J.R.; Thompson, C.B. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 2009, 324, 1076–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, T.; Mackay, L.; Sproul, D.; Karim, M.; Culley, J.; Harrison, D.J.; Hayward, L.; Langridge-Smith, P.; Gilbert, N.; Ramsahoye, B.H. Lactate, a product of glycolytic metabolism, inhibits histone deacetylase activity and promotes changes in gene expression. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, 4794–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Zhong, H.; Cheng, L.; Li, L.P.; Zhang, D.K. Post-translational protein lactylation modification in health and diseases: a double-edged sword. J Transl Med 2024, 22, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, S.; Qu, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Lactylation: a Passing Fad or the Future of Posttranslational Modification. Inflammation 2022, 45, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Virus-Induced Histone Lactylation Promotes Virus Infection in Crustacean. Advanced science 2024, 11, e2401017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, E.Q.; Ray, J.D.; Zerio, C.J.; Trujillo, M.N.; McDonald, D.M.; Chapman, E.; Spiegel, D.A.; Galligan, J.J. Sirtuin 2 Regulates Protein LactoylLys Modifications. Chembiochem 2021, 22, 2102–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, H.; Li, C.; Dai, C.; Pan, Y.; Ding, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Zang, J.; Mo, X. SIRT2 functions as a histone delactylase and inhibits the proliferation and migration of neuroblastoma cells. Cell Discov 2022, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, R.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.H. Acid-sensing Ion Channels: Implications for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2023, 24, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunder, S.; Vanek, J.; Pissas, K.P. Acid-sensing ion channels and downstream signalling in cancer cells: is there a mechanistic link? Pflugers Arch 2024, 476, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, H.; Ji, Q.; Cheng, X.; Thorne, R.F.; Hondermarck, H.; Liu, X.; Shen, C. ASIC1 and ASIC3 mediate cellular senescence of human nucleus pulposus mesenchymal stem cells during intervertebral disc degeneration. Aging (Albany NY) 2021, 13, 10703–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, F.R.; Xu, R.S.; Hu, W.; Jiang, D.L.; Ji, C.; Chen, F.H.; Yuan, F.L. Acid-sensing ion channel 1a-mediated calcium influx regulates apoptosis of endplate chondrocytes in intervertebral discs. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2014, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llibre, A.; Kucuk, S.; Gope, A.; Certo, M.; Mauro, C. Lactate: A key regulator of the immune response. Immunity 2025, 58, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Kuei, C.; Yu, J.; Shelton, J.; Sutton, S.W.; Li, X.; Yun, S.J.; Mirzadegan, T.; et al. Lactate inhibits lipolysis in fat cells through activation of an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR81. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 2811–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langin, D. Adipose tissue lipolysis revisited (again!): lactate involvement in insulin antilipolytic action. Cell Metab 2010, 11, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, G.A. Brain lactate metabolism: the discoveries and the controversies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012, 32, 1107–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Inman, D.M. Reduced AMPK activation and increased HCAR activation drive anti-inflammatory response and neuroprotection in glaucoma. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zeng, S.; Huang, M.; Qiu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhan, Z.; Liang, L.; Yang, X.; Xu, H. Inhibition of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase suppresses fibroblast-like synoviocytes-mediated synovial inflammation and joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Pharmacol 2017, 174, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebayehu, D.; Spence, A.J.; Qayum, A.A.; Taruselli, M.T.; McLeod, J.J.; Caslin, H.L.; Chumanevich, A.P.; Kolawole, E.M.; Paranjape, A.; Baker, B.; et al. Lactic Acid Suppresses IL-33-Mediated Mast Cell Inflammatory Responses via Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1alpha-Dependent miR-155 Suppression. J Immunol 2016, 197, 2909–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caslin, H.L.; Abebayehu, D.; Abdul Qayum, A.; Haque, T.T.; Taruselli, M.T.; Paez, P.A.; Pondicherry, N.; Barnstein, B.O.; Hoeferlin, L.A.; Chalfant, C.E.; et al. Lactic Acid Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Mast Cell Function by Limiting Glycolysis and ATP Availability. J Immunol 2019, 203, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yu, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ren, R.; Nie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Kang, H. Genkwanin alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration via regulating ITGA2/PI3K/AKT pathway and inhibiting apoptosis and senescence. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 133, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.H.; Song, J.; Shangguan, W.J.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Shao, J.; Zhang, Y.H. Melatonin mitigates matrix stiffness-induced intervertebral disk degeneration by inhibiting reactive oxygen species and melatonin receptors mediated PI3K/AKT/NF-kappaB pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2024, 327, C1236–C1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Ma, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, J.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Wei, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. Bradykinin protects nucleus pulposus cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced damage and delays intervertebral disc degeneration. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 134, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risbud, M.V.; Fertala, J.; Vresilovic, E.J.; Albert, T.J.; Shapiro, I.M. Nucleus pulposus cells upregulate PI3K/Akt and MEK/ERK signaling pathways under hypoxic conditions and resist apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Qi, Y.; Lou, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Chang, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. Lactic acid promotes nucleus pulposus cell senescence and corresponding intervertebral disc degeneration via interacting with Akt. Cell Mol Life Sci 2024, 81, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Alexander, P.G.; Feng, P.; Zhang, J. An Analysis of AMPK and Ferroptosis in Cancer: A Potential Regulatory Axis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 36618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, Q.; Ma, J.; Wang, L.; Quan, Z. Targeting Ferroptosis Holds Potential for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Therapy. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, W. Identification and validation of ferroptosis-related gene signature in intervertebral disc degeneration. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1089796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Peng, J.; Ding, F. 1,25(OH)(2)D(3) inhibits ferroptosis in nucleus pulposus cells via VDR signaling to mitigate lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 7968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Luo, R.; Li, S.; Li, G.; Wang, K.; Liao, Z.; Wang, B.; Ke, W.; Xiang, Q.; et al. Ferroportin-Dependent Iron Homeostasis Protects against Oxidative Stress-Induced Nucleus Pulposus Cell Ferroptosis and Ameliorates Intervertebral Disc Degeneration In Vivo. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 6670497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Shi, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, S.; Han, L.; Li, F.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Kang, Z.; et al. Glycolysis-Derived Lactate Induces ACSL4 Expression and Lactylation to Activate Ferroptosis during Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Advanced science 2025, 12, e2416149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, X.; Huang, B.; Shan, Z.; Liu, J.; Fan, S.; et al. Homocysteine induces oxidative stress and ferroptosis of nucleus pulposus via enhancing methylation of GPX4. Free Radic Biol Med 2020, 160, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).