Introduction

Modern theories of aging are based on a close connection of this process with disruptions in the interaction of a living organism’s genome with the exposome—a complex set of environmental exposures, including physical, chemical, and biological factors.

The evolutionarily shaped systems of interaction between the exposome and the living organism underlie the organism’s adaptation to changing environmental conditions.

With age, the body’s adaptive responses decline, which leads to a disruption in its regenerative and protective capabilities, resulting in the development of age-associated diseases and a deterioration in overall health [

1].

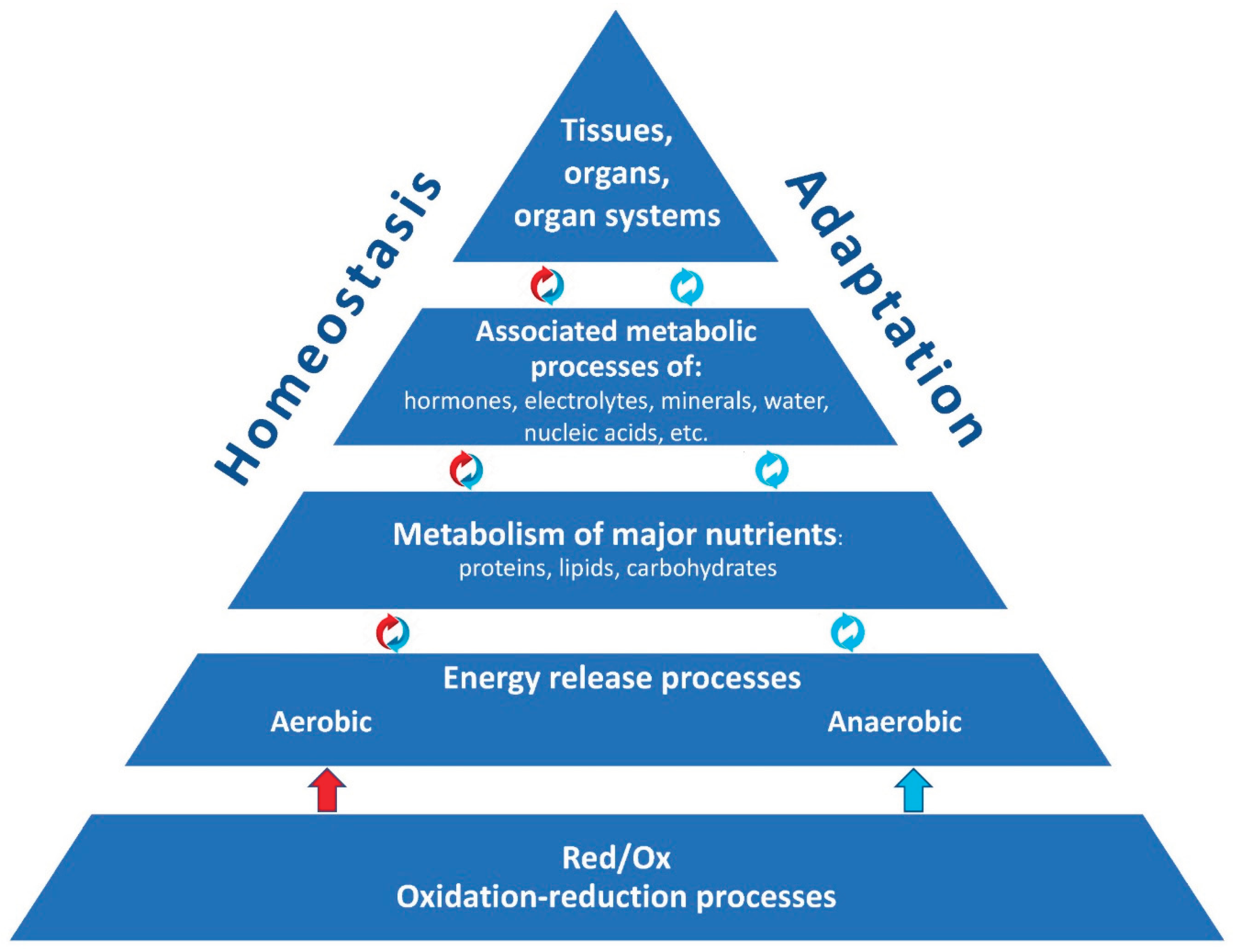

The body’s adaptive processes are inextricably intertwined with oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions, as they ensure the release of energy for life activity and homeostasis maintenance. Actually, redox reactions, their sufficient and necessary activity, are the foundation upon which the whole body’s structural and metabolic organization, homeostasis, and adaptive capacities are based (

Figure 1).

Mitochondria play a key role in maintaining homeostasis and in the processes of the organism’s adaptation to external and internal environmental changes, releasing energy through the coupling of redox reactions with the formation of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). Adaptive changes in the mitochondria themselves help the body respond to stress, hypoxia, and other negative impacts, influencing metabolism, defense mechanisms, and behavioral responses.

However, mitochondria are the main sources and targets of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which predetermines their important role in the aging process. Impaired mitochondrial quality and dynamics (fission and fusion processes), as well as a decrease in the activity of antioxidant systems such as the thioredoxin system and the NADPH-dependent system, lead to accumulation of damage that accelerates cellular and tissue aging.

Oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions are an integral part of balanced metabolism and physiological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and death. The physicochemical basis of the redox reaction is electron transfer (a chemical entity capable of donating electrons is a reducing agent, and a chemical entity capable of accepting electrons is an oxidizing agent).

Disruption of redox status and antioxidant defense greatly contributes to the development of age-associated diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders, and also leads to decreased cell viability. These factors point to the importance of maintaining mitochondrial functions and, above all, redox homeostasis for a potential slowing of the aging process [

2].

The basis of the cellular aging process is a disruption of mitochondrial quality control, including the mechanisms responsible for the removal of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy. A decreased mitophagy efficiency leads to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, thereby accelerating cellular aging.

Oxidative stress and redox imbalance result in damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, which affects the aging phenotype, including loss of cellular function and a higher likelihood of triggering cell death.

In this regard, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of redox modulation as a promising approach to the development of innovative geroprotectors—substances that can contribute to extending lifespan.

The Role of Mitochondria and Redox Status in Cellular Function

Mitochondria play a central role in cellular energy metabolism. They ensure production of up to 90% of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through oxidative phosphorylation. This energy production mechanism is accompanied by the formation of ROS as a byproduct.

When ROS levels exceed a cell’s antioxidant capacity, oxidative stress occurs, which can lead to various consequences, including damage to cellular structures and serious impairment of their functions [

3].

At the molecular level, redox status is determined by the balance between oxidizing and reducing agents, which affects the state of cellular molecules—proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. ROS, including superoxide (O

2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), are produced during normal cellular metabolism, especially in mitochondria, where they are byproducts of oxidative phosphorylation [

4].

At the same time, low concentrations of these compounds can perform important functions in redox signaling, regulating key cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [

5]. At normal concentrations, they act as intracellular signaling molecules; for example, hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion are important factors involved in the control of insulin synthesis and secretion in pancreatic β-cells.

Excessive ROS production, on the contrary, leads to damage to DNA, proteins, lipids, and other macromolecules, organelles and cells, their dysfunction, disruption of cellular homeostasis, and cell death. For example, the hydroxyl radical is considered a particularly reactive oxidant that can destroy phospholipids in cell membranes and proteins.

Antioxidants such as glutathione, ascorbic acid, and tocopherols act as protective agents, neutralizing excessive ROS and preventing damage to cell components.

Glutathione, for instance, exists in two forms: reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG), and the ratio of these forms serves as an important marker of cell redox status.

The normal functioning of antioxidant systems depends on the presence of ROS molecules such as NADPH, which provides reducing equivalents for the synthesis of GSH and other antioxidants. Redox status imbalance may result in oxidative stress, which is associated with the pathogenesis of various diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and tumor development.

Oxidative stress occurs when ROS levels exceed the cells’ ability to neutralize them, which can lead to damage to cell components, including DNA, proteins, and lipids. Such damage can initiate signaling cascades that lead to the activation of proliferative and apoptotic pathways, which can eventually contribute to disease development.

Maintaining an optimal redox status is crucial for normal function of cells and their ability to adapt to exogenous and endogenous stressors.

Activation of redox signaling can result in increased production of transcription factors, such as NRF2, which regulate the expression of genes responsible for antioxidant synthesis and other protective mechanisms.

Mitochondria, as the main source of ROS generation, interact with peroxisomes, which are involved in lipid metabolism and hydrogen peroxide detoxification. Thus, mitochondria and peroxisomes form a complex network of redox signals that determines cellular viability.

This interaction enables cells to adapt to changes in the microenvironment and maintain redox homeostasis. For example, under oxidative stress conditions, peroxisomes can enhance hydrogen peroxide degradation, thereby decreasing ROS levels, which helps protect mitochondria and other cellular structures from damage [

6].

To maintain redox homeostasis, mitochondria contain antioxidant enzymes—superoxide dismutase and peroxiredoxins. These enzymes play a key role in neutralizing ROS, preventing their accumulation and thereby protecting cellular structures from oxidative damage.

The effectiveness of mitochondrial antioxidant systems is critical for maintaining cellular function and preventing pathological conditions. Redox imbalances occurring through changes in mitochondrial membrane permeability and overexpression of various caspases can lead to the activation of cell death pathways that trigger apoptosis or necrosis.

Thus, extensive evidence suggests that mitochondria are key organelles involved in aging mechanisms and represent promising targets for developing new therapeutic approaches aimed at ensuring normal cellular function and slowing the aging process.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Inflammaging

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are involved in the mechanisms of aging and pathogenesis of age-associated diseases.

Mitochondrial dysfunction results in excessive ROS production, damaging mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and disrupting energy metabolism [

7]. Such changes initiate the activation of inflammatory signaling cascades through the formation of NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasomes, which contribute to the development of inflammaging [

8]. This vicious cycle, where damage caused by oxidative stress continues to impair mitochondrial function, creates conditions for the progression of various pathologies.

These processes are closely associated with inflammaging—a chronic aseptic inflammation that triggers cellular aging through forming a specific immunophenotype, which is characterized by a molecular imbalance—predominant proinflammatory cytokine production and a lack of endogenous geroprotectors [

9].

Inflammaging, as a consequence of innate immune activation via mitochondrial-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), becomes chronic and accelerates tissue aging. The role of inflammaging in the development of age-associated pathologies has been described in detail for neurodegenerative processes, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, autoimmune processes, sarcopenia [

10,

11,

12], and other pathologies.

Molecular Logistics of Mitochondrial Aging: The Contribution of Membrane Proteins

Mitochondrial aging is associated with disruptions in mitochondria structure, function, and proteostasis (the process of maintaining a sufficient protein pool for cell activity), leading to decreased energy metabolism and the development of age-associated diseases.

Mitochondrial membrane proteins play a key role in maintaining the dynamics, quality, and integrity of mitochondria, and their dysfunction triggers and catalyzes aging processes.

These proteins are essential in regulating the fusion of organelles which are crucial for maintaining mitochondrial dynamics and functional integrity. The processes of fission and fusion allow mitochondria to adapt to changes in metabolic conditions, ensuring the removal of damaged areas and organelle renewal [

13].

These mechanisms are critical for preventing the accumulation of damaged mitochondria which can disrupt cellular energetics and contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases.

Dysfunction of proteins on both the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes can result in significant disruptions in mitochondrial dynamics. For example, dysfunction of the proteins that are responsible for mitochondrial fusion can lead to the formation of long, undivided mitochondria (the effect of abnormality of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)), which makes their renewal and the removal of damaged areas more difficult. At the same time, disruptions in such proteins as MFN1 and MFN2 (Mitofusins 1 and 2) can prevent the restoration of mitochondrial function and promote the degradation of mitochondria. The accumulation of damaged mitochondria caused by these disruptions leads to a decrease in membrane potential and an increase in ROS production [

14].

Excessive ROS production can cause oxidative stress, which, in turn, exacerbates mitochondrial dysfunction and initiates cellular damage cascades which contribute to the development of aging-related diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic disruptions.

Some membrane proteins, such as the sorting and assembly machinery protein (SAM50) and ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 3 (ATAD3), play a key role in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and trigger the removal of damaged mitochondrial DNA. These proteins are involved in the endosomal-autophagic pathway which ensures the degradation of damaged mitochondria and prevents the accumulation of mutations, which is critical for maintaining the functional integrity of mitochondria and cell viability [

15].

As mentioned above, the efficiency of mitochondrial quality control mechanisms is directly linked to proteostasis—the system that ensures the proper folding, assembly, and degradation of proteins. Proteostasis is important for maintaining the functional activity of mitochondrial proteins, and its disruptions may result in the accumulation of misfolded or damaged proteins, which contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and accelerates the aging processes. Thus, maintaining proteostasis and the functional activity of membrane proteins is a crucial factor in preventing mitochondrial dysfunction and associated diseases.

The mitochondrial quality control system is responsible for the regulation and operation of a complex mechanism that ensures the selective removal of damaged or misfolded proteins. This supports the functional integrity of organelles. Mitochondrial-derived compartments (MDCs) and mitophagy play a key role in this process. MDCs function as specialized structures that are involved in the degradation of membrane proteins, ensuring their sorting and removal from the mitochondria.

This process also prevents the accumulation of damaged proteins in cells. The efficiency of mitophagy depends on various signaling pathways, including the activation of proteins such as PINK1 and Parkin, which are responsible for identifying and marking damaged mitochondria for subsequent removal. Disruptions in proteostasis and mitophagy are associated with accelerated aging and the development of neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, which points to the need of maintaining their functional activity to prevent cellular dysfunction [

16].

With age, structural and functional changes are observed in the protein complexes of the respiratory chain and ATP synthase, resulting in a reduced efficiency of energy metabolism. These changes can be caused by both the accumulation of damaged proteins and disruptions in mitochondrial fission and fusion, which impedes mitochondrial population renewal and increases the likelihood of oxidative stress.

Dysfunction of the protein complexes of the respiratory chain leads to decreased ATP synthesis, which has a negative impact on cellular energy metabolism and contributes to the development of various pathologies, including age-associated neurodegenerative diseases [

17].

Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), which are formed between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), play an important role in regulating numerous cellular processes, including lipid metabolism, calcium homeostasis, and autophagy. These structures mediate the interaction between mitochondria and the ER, enabling the coordination of metabolism and signals between the two organelles.

MAM dysfunction may lead to disruption of these processes, which, in turn, contributes to cellular senescence and the development of associated diseases, such as metabolic syndrome and neurodegenerative disorders.

Maintaining the functional activity of membrane proteins, effective control of mitochondrial quality and dynamics, and the integrity of mitochondria-associated membranes is crucial for ensuring cellular homeostasis and slowing the aging processes [

18].

Molecular Geroprotectors: Modern Approaches to Slowing Senescence

Geroprotectors are substances that slow the aging process, improve quality of life, and reduce the risk of developing age-associated diseases. Furthermore, geroprotectors should stimulate the synthesis of signaling molecules whose expression decreases with age [

19].

The development and widespread implementation of molecular and cellular technologies in biomedicine have helped identify a number of potential compounds that could act as geroprotectors [

20].

Among these, flavonoids are the most common class of substances demonstrating geroprotective activity. Thus, the administration of flavonoid C- and O-glycosides isolated from an aerial part of

L. hedysaroides into a culture of HuTu80 cancer cells resulted in the inhibition of the α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase enzyme which is a recognized therapeutic target in oncology [

21].

Another promising flavonoid, dihydroquercetin, isolated from coniferous plants, is a potential herbal remedy for preventing the aging processes. A study of the effects of a modified form of this substance on the central nervous system (CNS) of animals of different ages, for neuroinflammation modeling, demonstrated a therapeutic effect of dihydroquercetin [

22].

The administration of dihydroquercetin contributed to the improvement of morphological parameters of blood vessels in the substantia nigra of the brain, including their total length, area, and number of bifurcations. Furthermore, a pronounced effect was observed in older animals under conditions of intense neuroinflammation. A study assessing the effectiveness of polyphenols on the rate of H

2O

2 generation in rats with liver injury showed that dihydroquercetin, pinosylvin, and dihydromyricetin reduced mitochondrial ROS production, demonstrating the antioxidant effect of these substances [

23].

Another well-known polyphenol, resveratrol, also has geroprotective potential. The main beneficial effects of this substance include cardioprotective, vasodilatory, and antidiabetic actions [

24]. Studies of resveratrol modifications have shown their cytoprotective effect, mediated through various molecular mechanisms. Thus, monomethylresveratrol reduced the caspase-3 activity and effectively removed superoxide through mitophagy. Oxyresveratrol also induced cytoprotection, but without mitophagy activation [

24].

A randomized clinical trial of the effects of short-term resveratrol treatment of patients with hypertension showed increased levels of nitric oxide, a key molecule in vasodilation, but this did not lead to blood pressure reduction [

25].

Regretfully, all of the above-mentioned flavonoids have limited clinical application due to a number of factors, including low solubility and bioavailability, the need for purification and labor-intensive extraction from plants, as well as the lack of epidemiological studies of this group of substances [

26].

A major problem with flavonoids is their poor pharmacokinetics, and therefore the biosynthesis of modified flavonoids with more favorable biophysical and pharmacokinetic properties for clinical application is an important task in modern geriatrics [

27].

Of course, one of the previously mentioned processes involved in the development of pathological aging is inflammaging. The NF-κB signaling pathway is a key link in the interplay of inflammation and aging processes—its hyperactivation leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines and the development of a chronic inflammatory phenotype. The use of substances that inhibit this pathway, with maintaining a balance between reducing inflammation and preserving physiological immune responses, is a promising option for fighting pathological aging.

Melatonin is a geroprotector and a circadian rhythm regulator, exhibiting powerful antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activity. A study of melatonin effects on the NF-κB signaling pathway revealed its limited impact, yet melatonin is capable of inhibiting biomolecules controlled by this pathway.

The combined use of melatonin and anticancer drugs such as temozolomide and cisplatin significantly reduced tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [

28], and also helped reduce the toxic effects of cytostatic drugs and tissue destruction by inhibiting COX-2 production [

29]. Melatonin has also been shown to stimulate lifespan in

Drosophila melanogaster, with the greatest effect observed in mutant lines

(Sod and

mus210), which confirms the ability of this geroprotector to detoxify free radicals and decrease oxidative stress [

30].

Bioavailable geroprotectors are represented by a group of low molecular weight antioxidants—vitamins A, E, and C. Retinol, a vitamin A derivative, is believed to be one of the most effective substances for fighting against skin aging. Retinol can stimulate collagen synthesis, inhibit matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, reduce oxidative stress, and modulate the expression of skin renewal genes [

31].

Research into the effects of these vitamins on T-cell proliferation, oxidative status, and cytokine production in older adults demonstrated that administration of vitamins C and E significantly improved these parameters, reducing intracellular oxidative stress which is observed in elderly people due to depletion of the GSH system [

32].

Furthermore, vitamin C stimulates the activity of several transcription factors (Nrf2, Ref-1, AP-1), which promotes the expression of genes encoding antioxidant proteins. Its another function is to support the action of other exogenous antioxidants, primarily polyphenols [

33].

Rapamycin, an immunosuppressant and mTOR inhibitor, is a key regulator of cellular growth, metabolism, and aging. Rapamycin binds to its receptor, the cytoplasmic protein FKBP12 (FK-binding protein 12), after which this complex verifies the FRB domain (FKBP12-Rapamycin binding domain) of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), leading to destabilization of the complex.

Moreover, rapamycin is capable of suppressing the response to IL-2, preventing the activation of T and B cells. The inhibition of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling increases lifespan in yeast, worms, flies, and mice [

34]. Rapamycin also improves the condition of mice in an inflammaging model, with positive effects including improved long-term memory, better neuromuscular coordination, and restoration of tissue architecture [

35]. The use of rapamycin as a geroprotector is still at the stage of clinical trials, while researchers are looking for the optimal dosage regimen and its analogs with milder side effects.

So, despite the impressive geroprotective potential demonstrated by compounds from the flavonoid group, mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin), and circadian rhythm regulators (melatonin), their widespread clinical use faces such challenges as low bioavailability, side effects, and the lack of large-scale randomized trials in humans.

Redox Status Modulation During Aging: Prevention of Accelerated Organ and Tissue Involution

A change in redox status is viewed as one of the key triggers for the development of accelerated and pathological aging, and its targeted modulation can be a strategy for slowing these processes and maintaining the functional activity of tissues at an evolutionarily determined level [

36]. The most promising strategy for maintaining the balance between oxidative and reductive processes in the body during aging is the activation of the endogenous antioxidant system.

An impact on the KEAP1-NRF2 signaling pathway (a regulator of antioxidant gene transcription) activates GSH production and associated enzyme systems (glutathione-S-transferase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase), as well as SOD enzymes, catalase, and heme oxygenase-1 [

37]. Thus, the targeted pharmacological activation of NRF2 in endothelial progenitor cells of aged mice protects these cells from oxidative stress, reduces their biological dysfunction, and decreases NLRP3 inflammasome expression [

38].

In birds with high levels of ROS, activation of this pathway is an adaptive mechanism for combating oxidative stress [

39]. In male fruit flies, mutations leading to loss of function of the KEAP1 gene have a significant positive effect on resistance to oxidative stress and lifespan [

40].

A major protective antioxidant mechanism activated by the KEAP1-NRF2 system is the induction of the expression of GPX2, PRDX2, TXN1, and SRXN1 genes, whose biological role is to maintain redox homeostasis through the activation of GCLC, GSLM, and GST, which are involved in GSH biosynthesis; while NQO1 and CYP2A6 are involved in xenobiotics detoxification [

41].

Another important function of this pathway is the regulation of GSH synthesis: its activation leads to the expression of the genes encoding the catalytic subunits of glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCLC) and glutathione synthetase (GSS), which are key enzymes in GSH synthesis, also resulting in increased activity of glutathione reductase (GSR), which restores oxidized glutathione.

NRF2 knockout (NRF2

−/−) mouse offspring exhibited low intracellular and extracellular GSH levels in astrocytes as compared to glial cells cultured from NRF2 wild-type (NRF2

+/+) offspring [

42]. It is important to account for the dual role of prolonged and excessive NRF2 activation: it can promote malignant cell survival and chemotherapy resistance [

43]. Therefore, approaches aimed at its temporary or cyclic activation, mimicking the body’s natural rhythms, are believed to be promising.

Another way to activate the endogenous antioxidant system is to replenish the NAD+ pool, an essential cofactor for many enzymatic reactions. Its level is critical for sirtuin synthesis and DNA repair. The NAD+ level decreases significantly with age, and this is also one of the causes of aging and the development of age-associated diseases.

Aging has been shown to be accompanied by a decrease in the NAD

+/NADH ratio in human plasma due to the depletion of NAD

+ stores, rather than as a consequence of an increase in NADH content [

44].

Sirtuins (SIRT1-6) are NAD

+-dependent deacetylases that catalyze the removal of the acetyl group from lysines on histones and proteins, playing a key role in regulating genome stability, energy homeostasis, and signaling mechanisms for anti-stress and geroprotective functions [

45].

It has been established that individuals with low SIRT1 levels in childhood are prone to the development of premature cardiovascular dysfunction in adulthood [

46]. NAD

+ deficiency during aging leads to oxidative tissue damage, decreased metabolism, disruption of circadian rhythms, and the development of mitochondrial dysfunction due to dysregulation of sirtuin expression and disruption of signaling pathways that involve p53, NF-κB, PGC-1α, and HIF-1α [

47].

The development of these pathophysiological mechanisms shortens lifespan. It has been noted that increasing intracellular NAD

+ levels can be a therapeutic strategy for combating pathological aging. However, the intake of NAD

+ appears to be ineffective as it is not absorbed by cells. Therefore, it is advisable to use this strategy by increasing the levels of NAD

+ precursors (nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinamide riboside) and controlling the biosynthesis of this molecule [

44,

47].

Glutathione as a Key Molecule for Redox Status Modulation

Glutathione (GSH) is considered a central component and a major orchestrator of cellular redox status. This universal molecule is present in all cells in high concentrations, and its level and the ratio of its reduced (GSH) to oxidized (GSSG) forms are viewed as an integral indicator of oxidative stress, which plays a key role in aging mechanisms. Detailed investigation into GSH metabolism and functions should be the basis for the development of geroprotective strategies.

The intracellular distribution of GSH is dynamic: it is synthesized only in the cytoplasm, and transporter proteins distribute GSH throughout organelles [

48]. The outer mitochondrial membrane contains a large number of porins (voltage-dependent anion-selective channels, or VDACs), while the inner membrane contains oxoglutarate and dicarboxylate transporters that transport GSH into mitochondria.

GSH relocalization into the nucleus occurs through nuclear pores—receptor complexes associated with Bcl-2 expression. GSH is also found in the endoplasmic reticulum, where it diffuses into the cytoplasm, being activated by Sec61.

Intracellular/extracellular GSH exchange occurs through the functioning of VDACs involving OATPs (organic anion-transporting polypeptides), CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator), and MRPs (multidrug resistance proteins).

The mitochondrial GSH pool is particularly important, as mitochondria are the main source of ROS in aging. When the level of the mitochondrial GSH pool decreases even slightly, cells become susceptible to oxidative damage, and this may trigger intrinsic mechanisms of apoptosis and necrosis. This level decreases by almost 50% with aging [

49].

A key property of GSH is its ability to undergo oxidation and reduction. Three GSH pools are distinguished: reduced, oxidized (GSSG), and conjugates with numerous exogenous and endogenous compounds. And the GSH/GSSG ratio reflects the cellular redox status. A shift toward an increased proportion of GSSG is a key marker of oxidative stress.

The formation of GSSG may be associated with the direct interaction of GSH with ROS. GSH can neutralize hydroxyl radicals (•OH), hydroperoxide radicals (НО2•), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitroxyl radicals (NO•), and peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−) thanks to the presence of “traps” in the form of a thiol group (-SH). Two GSH molecules donate a hydrogen atom, forming a GSSG dimer (2GSH → GSSG + 2 H+), thereby reducing the ROS molecule. The oxidized form can then be reconverted into two GSH molecules via glutathione reductase and NADPH (GSSG + NADPH + H⁺ → 2 GSH + NADP⁺).

Besides its direct interaction with ROS and RNS, GSH is a cofactor for a number of enzymes that enhance its antioxidant properties. One of such enzymes is glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which catalyzes the reduction of H2O2 and hydroxyperoxides to H2O and ROH alcohol. In this reaction, GSH acts as an electron donor.

Glutathione reductase (GR) is an enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of oxidized GSSG to its active form, using NADPH as an H+ source. The reaction catalyzed by GR is a source of GSH in the cytosol and some organelles. Glutathione S-transferase (GSTs) catalyzes the conjugation of GSH with a wide range of compounds, which are often formed through cytochrome P450 metabolism.

These reactions detoxify metabolic products, making them water-soluble and more easily excreted. Considerable attention has been paid to glutaredoxins (GRx), small proteins that reduce protein disulfides using GSH as an electron donor.

Glutaredoxin-catalyzed de/glutathionylation is an important event in signal transduction, serving as a primary protective mechanism against the irreversible oxidation of cysteine residues. The age-related decline in the activity of enzymes (a cofactor of which is GSH) further exacerbates redox disorders, impeding GSH restoration from GSSG and cellular antioxidant defense.

GSH depletion is known to be associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity develop when antioxidant defenses are impaired in patients with Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [

50,

51,

52].

Studies show that geroprotective strategies aimed at modulation of GSH and related enzymes can be highly effective. So, immune system function has been shown to correlate with the state of the GSH system: higher levels of GPx, GR, and GSH, and lower values of GSSG and the GSSG/GSH ratio, improve peripheral blood leukocyte counts in subjects [

50].

Thus, these findings convincingly demonstrate that GSH is not just a biomarker but also a master regulator of redox status, and its dysfunction underlies many age-associated diseases. This makes the GSH system a key target for geroprotective interventions.

Strategies aimed at maintaining GSH synthesis, restoring the GSH/GSSG ratio, and enhancing the activity of the enzymatic systems it controls appear to be a scientifically sound and promising approach to preventing accelerated age-related organ and tissue involution.

Glutathione-Based Drugs: A Targeted Geroprotective Effect on Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Two medicines have been added to the Russia State Pharmacopoeia, the active ingredient of which is GSSG and its derivative, and a derivative of GSSG and inosine, inosine-glycyl-cysteinyl-glutamate disodium, which have pronounced antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties.

Inosine and GSSG, as part of inosine-glycyl-cysteinyl-glutamate disodium, are complementary in both pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic terms. At the cellular level, the complementarity of GSSG and inosine is expressed in that GSSG increases the affinity of A1, A2A, and A3 receptors for inosine.

A direct or indirect effect of GSSG on inosine-sensitive receptors is manifested in the formation of disulfide cross-links in the structure of the cell surface domain of the receptor protein (inosine-sensitive receptors have at least one disulfide cross-link in their functionally active conformation).

The combined action of these substances at the cellular level translates into positive changes at the tissue or organ level, and throughout the body.

The developed drugs have the ability to maintain cellular redox balance, and they can be viewed as potential geroprotectors for the prevention and treatment of age-associated diseases, as well as for maintaining health throughout life.

Both drugs activate the glutathione antioxidant system, which helps reduce oxidative stress and maintain cellular energy metabolism (GSH, as a major antioxidant, plays a key role in neutralizing free radicals and protecting cells from damage caused by oxidative stress).

Drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine affect the intracellular concentration of calcium ions (Ca²⁺) in macrophages by activating phospholipase A2 and the arachidonic acid cascade. Inhibition of phospholipase A2 with 4-bromophenacyl bromide and glucocorticosteroids such as prednisolone and dexamethasone has been shown to significantly suppress the Ca²⁺ responses induced by these drugs. These findings highlight the role of phospholipase A2 in signaling pathways associated with GSSG-based and GSSG-derivative-and-inosine-based drugs [

53,

55].

In addition to its antioxidant properties, GSSG-based and inosine-based drugs also exhibit functions of regulating energy metabolism and GABA receptor ligands [

54]. This promotes the restoration of cognitive functions and reduces the effects of toxic and hypoxic damage to the central nervous system.

Studies in patients with acute conditions such as toxic coma and pancreatitis, demonstrated the ability of GSSG-based and GSSG-derivative-inosine-based drugs to accelerate recovery and improve metabolic parameters, which may serve as an indirect indication of their potential for maintaining optimal quality of life during aging.

Haloperidol (a Sigma-1 receptor antagonist) has also been found to suppress the Ca²-response induced by a derivative drug based on GSSG and inosine in macrophages, which points to the involvement of sigma-1 receptors in its action [

56]. The GSSG-based drug in the study demonstrated the ability to prevent pathological changes caused by toxic effects of cytostatics, including developmental, cognitive, and adaptive disorders in animal offspring.

These findings point to the important role of the GSSG-based drug, and especially the GSSG derivative and inosine, in protecting cells from oxidative and mitochondrial stress, which is critical for maintaining mitochondrial function [

57]. A drug based on GSSG and inosine demonstrated obvious hepatoprotective properties in patients with toxic liver injury, which is associated with maintaining mitochondrial metabolism and reducing cellular damage [

58].

The GSSG-based drug shows potential for molecular prevention of inflammaging, contributing to the correction of immune disorders and reducing the severity of chronic inflammation. It also improves the effectiveness of antibacterial therapy and promotes the elimination of pathogens, which contributes to a decrease in chronic inflammation levels [

59].

In studies using skin disease (psoriasis) models, a GSSG-based drug corrected the expression of cell cycle proteins associated with inflammation and proliferation, thereby reflecting its role in regulating inflammatory processes [

60].

It has been shown that the age-related decrease in GSH levels and imbalance in its system play an important role in the development of oxidative stress leading to pathological aging.

Thus, a targeted impact on the GSH system is one of the most substantiated approaches to geroprotection. Pharmacological solutions based on GSSG, GSSG derivatives, and inosine, as GSSG pharmaceutical forms, are promising agents for correcting redox status by a targeted impact on the GSH system.

Unlike direct administration of GSH, which is poorly absorbed, GSSG serves as a substrate for reduction to active GSH by the GR enzyme, effectively increasing the intracellular GSH concentration. Moreover, GSSG administration becomes a natural signal of oxidative stress for the cell and can indirectly activate the NRF2 pathway.

Activation of the NRF2 pathway, as described above, stimulates not only the cellular antioxidant defense via GSH but also recruits SOD enzymes, catalase, and heme oxygenase-1. It is important to note that unlike direct and persistent activation of NRF2, which may have negative consequences, GSSG administration seems to mimic natural physiological signals, resulting in temporary and balanced activation of this pathway.

Thus, drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine not only replenish the GSH pool but also stimulate the production of numerous enzymes involved in combating cellular oxidative stress. For instance, toxic liver damage resulting from the metabolism of anti-tuberculosis drugs and accompanied by ROS production was reduced by the administration of these drugs [

61]. In patients with fatty liver disease combined with liver fibrosis, the administration of a drug based on GSSG and inosine significantly reduced the disease severity, exerting an anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effect [

62].

Liver damage resulting from ethanol detoxification was also corrected by a drug based on GSSG derivative and inosine. It significantly reduced the activity of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and direct bilirubin three hours after administration. The same study showed improved metabolism, with a decrease in lactate levels and an increase in potassium content in the blood electrolyte profile [

63].

Correction of toxic liver damage demonstrates the ability of these drugs to protect organs from injuries, the mechanisms of which are similar to the processes of accelerated organ involution with aging. It was also shown that administration of a GSSG-based drug altered GR activity in influenza: after treatment, it decreased but remained higher than in the group of subjects receiving only antiviral therapy [

64].

This may be evidence of an increase in the activity of GSH system enzymes and a potential enhancement of cellular antioxidant defense.

Chronic alcohol intoxication is associated with changes in the functional and metabolic activity of peripheral blood neutrophils, which are typical of an inflammatory response and characterized by increased oxygen-dependent activity and decreased cell phagocytic activity. The use of a GSSG-based drug as an antioxidant resulted in normalization of granulocyte functional activity parameters in an animal model of combined experimental acute pancreatitis and chronic alcohol intoxication [

65].

The experiment provided important evidence of a geroprotective targeted effect of drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine through normalization of mitochondrial protein expression. Administration of the drugs to older rats resulted in increased expression of proteins—TOM 20 and 70, VDAC, DRP1, Parkin, PINK1, and prohibitin—which are major regulators of mitochondrial function (mitochondrial fission, mitochondrial DNA stability, and protection against alterations in the internal potential of the mitochondrial membrane) [

66,

67].

A study of the effect of these two drugs on the expression of key signaling molecules involved in inflammaging mechanisms showed that the primary target of the geroprotective action of the drug based on the GSSG derivative and inosine is prohibitin, while the targets of the geroprotective action of the GSSG-based drug are telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) and prohibitin. The administration of the drugs into the endometrial cell culture under conditions of inflammaging modeling resulted in a return of the expression values of hTERT and prohibitin markers to the values of the control group, which pointed to the activation of repair processes and cells’ fight against oxidative stress [

68].

Further comprehensive studies of drugs based on GSSG and its derivatives will help clarify the mechanism of their effect on the expression of key signaling gerotropic molecules and, thereby, expand indications for their use as therapeutic agents for the prevention of premature aging and for the treatment of age-associated diseases.

These clinical and experimental data demonstrate that correction of the GSH system with GSSG-based drugs is effective for a wide range of pathologies associated with oxidative stress, from toxic liver damage to viral infections. Their ability to restore redox balance and cellular function confirms the high potential of drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine as proven geroprotective agents.

Conclusions

Numerous studies confirm that mitochondrial dysfunction and associated redox status imbalance are major pathogenetic factors in the aging process. Disruption of mitochondrial quality control, defects in mitophagy, and the accumulation of dysfunctional organelles initiate oxidative stress, which then leads to macromolecular damage and chronic systemic inflammation (inflammaging), which creates the foundation for the development of a wide range of age-associated diseases.

In this context, strategies aimed at modulating redox homeostasis appear to be a very promising approach to the development of geroprotectors.

The glutathione system plays a pivotal role in maintaining cellular redox status, where the GSH/GSSG ratio is an indicator of oxidative stress. The age-dependent decline in the mitochondrial GSH pool and the activity of associated enzymes (glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, and glutathione-S-transferase) critically impairs antioxidant defenses, increasing cellular vulnerability to apoptosis and necrosis.

An overview of various classes of geroprotective compounds, including flavonoids, NRF2 pathway activators (KEAP1-NRF2), NAD+ level and sirtuin modulators, and mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin), has shown their significant potential in experimental models. However, their clinical application is limited by pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and a lack of large-scale randomized trials.

In this context, drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine are of particular interest. Unlike exogenous GSH, GSSG is effectively absorbed by cells, acting as a substrate for glutathione reductase, and can indirectly activate the NRF2 pathway, potentiating the expression of a wide range of antioxidant and detoxifying genes. Experimental and clinical data demonstrate their efficiency in correcting pathologies associated with oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, including toxic liver damage, neurodegenerative processes, and immune disorders, which becomes evident in normalization of biochemical markers, improved mitochondrial biogenesis, and enhanced activity of glutathione system enzymes.

It seems interesting and promising to conduct a theoretical analysis of the role of redox balance in aging from the perspective of V.M. Dilman’s concept [

69] and, on these grounds, formulate prospects for developing a line of modern innovative geroprotectors based on glutathione as a base molecule.

V.M. Dilman’s concept of aging views this process as a systemic and largely programmed shift in the regulation of homeostasis. In contrast to theories that explain aging through the accumulation of molecular damage, V.M. Dilman draws attention to neuroendocrine regulation. According to him, the key element is a decrease in the sensitivity of the hypothalamus to feedback signals from hormones and mediators.

As a result, there occurs a shift of the “set points” of metabolic processes and adaptive mechanisms. In practical terms, this means that with age, the body becomes increasingly less able to maintain balance, respond to stress stimuli, and control cellular processes.

It is this systemic drift of regulation that underlies the most common age-associated diseases. V.M. Dilman distinguished four groups of such pathologies: oncological diseases (resulting from loss of control over cell proliferation), atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases (resulting from impairments in lipid metabolism and vascular tone), type II diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome (associated with insulin resistance), and, finally, osteoporosis and degenerative changes in the musculoskeletal system.

These diseases are essentially different manifestations of a single mechanism—a systemic shift in regulation. Modern biology of aging confirms many of V.M. Dilman’s ideas. Today, scientists identify twelve signs of aging, including genomic instability, telomere shortening, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, chronic inflammation, deregulated nutrient sensitivity, and others. These signs can be viewed as modules of the aging program described by V.M. Dilman. Central among them is the disruption of redox homeostasis.

Redox regulation is a universal mechanism for controlling biological processes. Reversible oxidation of sulfur- and selenium-containing residues in proteins acts as a switch that determines the activity of enzymes, receptors, and ion channels.

Under normal conditions, the redox balance is within the eustress range, when ROS perform signaling functions and participate in the regulation of cellular processes. With age, however, there occurs a shift toward distress, where ROS begin to exert a damaging effect, promoting inflammation, apoptosis, and tissue damage. This shift disrupts the fine-tuning of regulatory systems, including the neuroimmunoendocrine cellular and molecular networks, and becomes a key factor in the progression of age-dependent pathologies.

In this regard, GSSG mimetics—molecules that mimic the functions of oxidized glutathione—are of particular interest. Glutathione is a major cellular antioxidant and regulator of redox homeostasis, and its oxidized form (GSSG) plays a pivotal role in switching cellular programs. The use of GSSG mimetics can induce a state of hormesis, increasing the body’s resilience to stress impacts, and in pathological conditions, it can transfer the system from distress back to eustress. The primary mechanism here consists of modulating the redox balance of the diffuse neuroimmunoendocrine system.

Functional effects of a GSSG mimetic have been confirmed by certain experimental data.

First, it activates antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase, reducing oxidative stress.

Second, it influences the regulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and ferroptosis, thereby maintaining a balance between cell survival and renewal.

Third, a GSSG mimetic affects gene expression through activation of the Nrf2 transcription factor, leading to increased synthesis of antioxidant proteins and detoxification enzymes, including glutathione-S-transferase and haptoglobin.

Fourth, it helps reduce inflammatory processes, which are closely associated with oxidative stress and are considered a critical driver of aging.

The main advantage of GSSG mimetics is their ability to function not only as a geroprotector but also as an enhancer of drug action. The sensitivity of pharmacological targets to drug action can be increased through redox tuning of the proteome—subtle modification of receptors, ion channels, and enzymes. This helps achieve a therapeutic effect with lower drug doses, reducing toxicity and decreasing the risk of adverse reactions. This approach is particularly important in gerontology, where patients often face polypharmacy and drug-induced complications.

Thus, the combination of V.M. Dilman’s ideas and modern concepts of redox status can be considered as a holistic model of aging as a process of loss of regulatory sensitivity and homeodynamic balance.

Within this system, GSSG mimetics act as core molecules: they simultaneously correct fundamental mechanisms of aging and enhance the action of existing drugs. This makes them a primary geroprotective tool for the prevention and treatment of age-associated diseases.

Therefore, the targeted modulation of the GSH system using drugs based on GSSG and GSSG derivative and inosine can be viewed as a valid pathogenetic strategy for targeted geroprotection aimed at slowing cellular senescence and maintaining the functional homeostasis of organs and tissues.

Prospects for further research include an in-depth investigation of molecular mechanisms of glutathione derivative action and controlled clinical trials to evaluate their effectiveness directly in the context of prolonging human life expectancy and quality of life.

References

- Sies H, Mailloux RJ, Jakob U. Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024;25:701–19. [CrossRef]

- Meng J, Lv Z, Qiao X, et al. The decay of Redox-stress Response Capacity is a substantive characteristic of aging: Revising the redox theory of aging. Redox Biol 2017;11:365–74. [CrossRef]

- Palma FR, He C, Danes JM, et al. Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase: What the Established, the Intriguing, and the Novel Reveal About a Key Cellular Redox Switch. Antioxid Redox Signal 2020;32:701–14. [CrossRef]

- Mailloux RJ. An Update on Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Antioxidants 2020;9:472. [CrossRef]

- Ježek P, Holendová B, Plecitá-Hlavatá L. Redox Signaling from Mitochondria: Signal Propagation and Its Targets. Biomolecules 2020;10:93. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov A V., Margreiter R, Ausserlechner MJ, et al. The Complex Interplay between Mitochondria, ROS and Entire Cellular Metabolism. Antioxidants 2022;11:1995. [CrossRef]

- Bottje WG. Oxidative metabolism and efficiency: the delicate balancing act of mitochondria. Poult Sci 2019;98:4223–30. [CrossRef]

- Ježek P, Dlasková A, Engstová H, et al. Mitochondrial Physiology of Cellular Redox Regulations. Physiol Res 2024:S217–42. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese V, Santoro A, Monti D, et al. Aging and Parkinson’s Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med 2018;115:80–91. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, et al. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:576–90. [CrossRef]

- Zuo L, Prather ER, Stetskiv M, et al. Inflammaging and Oxidative Stress in Human Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:4472. [CrossRef]

- Livshits G, Kalinkovich A. Inflammaging as a common ground for the development and maintenance of sarcopenia, obesity, cardiomyopathy and dysbiosis. Ageing Res Rev 2019;56:100980. [CrossRef]

- Giacomello M, Pyakurel A, Glytsou C, et al. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020;21:204–24. [CrossRef]

- Tábara L-C, Segawa M, Prudent J. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2025;26:123–46. [CrossRef]

- Sen A, Kallabis S, Gaedke F, et al. Mitochondrial membrane proteins and VPS35 orchestrate selective removal of mtDNA. Nat Commun 2022;13:6704. [CrossRef]

- Hughes AL, Hughes CE, Henderson KA, et al. Selective sorting and destruction of mitochondrial membrane proteins in aged yeast. Elife 2016;5. [CrossRef]

- Miwa S, Kashyap S, Chini E, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2022;132. [CrossRef]

- Janikiewicz J, Szymański J, Malinska D, et al. Mitochondria-associated membranes in aging and senescence: structure, function, and dynamics. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:332. [CrossRef]

- Moskalev AA. Potential Geroprotectors-From Bench to Clinic 2023;88:2101–8. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-de-la-Cruz JA, Rivero-Segura NA, Alvarez-Sánchez ME, et al. Network Pharmacology and Machine Learning Identify Flavonoids as Potential Senotherapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2025;18:1176. [CrossRef]

- Tarbeeva DV, Pislyagin EA, Menchinskaya ES, Berdyshev DV, Kalinovskiy AI, Grigorchuk VP, Mishchenko NP, Aminin DL, Fedoreyev SA. Polyphenolic Compounds from Lespedeza bicolor Protect Neuronal Cells from Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Apr 3;11(4):709. [CrossRef]

- Orlova SV, Tatarinov VV, Nikitina EA, Sheremeta AV, Ivlev VA, Vasil’ev VG, Paliy KV, Goryainov SV. Bioavailability and Safety of Dihydroquercetin (Review). Pharm Chem J. 2022;55(11):1133-1137. [CrossRef]

- Guan Y, Li L, Yang R, Lu Y, Tang J. Targeting mitochondria with natural polyphenols for treating Neurodegenerative Diseases: a comprehensive scoping review from oxidative stress perspective. J Transl Med. 2025 May 23;23(1):572. [CrossRef]

- Varga K, Paszternák A, Kovács V, et al. Differential Cytoprotective Effect of Resveratrol and Its Derivatives: Focus on Antioxidant and Autophagy-Inducing Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:11274. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei E, Rezaei M, Mahmoodi M, et al. Preliminary, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled cross-over study with resveratrol in hypertensive patients. Sci Rep 2025;15:31297. [CrossRef]

- Amawi H, Ashby CR, Tiwari AK. Cancer chemoprevention through dietary flavonoids: what’s limiting? Chin J Cancer 2017;36. [CrossRef]

- Sajid M, Channakesavula CN, Stone SR, et al. Synthetic Biology towards Improved Flavonoid Pharmacokinetics. Biomolecules 2021;11:754. [CrossRef]

- Tang H, Dai Q, Zhao Z, et al. Melatonin Synergises the Chemotherapeutic Effect of Temozolomide in Glioblastoma by Suppressing NF-κB/COX-2 Signalling Pathways. J Cell Mol Med 2025;29. [CrossRef]

- Badawy AM, Ibrahim M, Taha M, et al. Melatonin Mitigates Cisplatin-Induced Submandibular Gland Damage by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Fibrosis. Cureus 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed MZ, Khatoon R, Talat F, Alam MM, Tabassum H, Parvez S. Melatonin Mitigates Rotenone-Induced Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Drosophila melanogaster Model of Parkinson’s Disease-like Symptoms. ACS Omega. 2023 Feb 20;8(8):7279-7288. [CrossRef]

- Quan T. Human Skin Aging and the Anti-Aging Properties of Retinol. Biomolecules 2023;13:1614. [CrossRef]

- Bouamama S, Merzouk H, Medjdoub A, et al. Effects of exogenous vitamins A, C, and E and NADH supplementation on proliferation, cytokines release, and cell redox status of lymphocytes from healthy aged subjects. Https://DoiOrg/101139/Apnm-2016-0201 2017;42:579–87. [CrossRef]

- Gęgotek A, Skrzydlewska E. Ascorbic acid as antioxidant. Vitam Horm 2023;121:247–70. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny M V. Rapamycin for longevity: opinion article. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:8048. [CrossRef]

- Correia-Melo C, Birch J, Fielder E, et al. Rapamycin improves healthspan but not inflammaging in nfκb1−/− mice. Aging Cell 2019;18:e12882. [CrossRef]

- Nie C, Li Y, Li R, et al. Distinct biological ages of organs and systems identified from a multi-omics study. Cell Rep 2022;38:110459. [CrossRef]

- Biswas M, Chan JY. Role of Nrf1 in antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression and beyond. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2009;244:16. [CrossRef]

- Wang R, Liu L, Liu H, et al. Reduced NRF2 expression suppresses endothelial progenitor cell function and induces senescence during aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11:7021. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione GM, Xu Z, Zhou L, et al. Adaptation of the master antioxidant response connects metabolism, lifespan and feather development pathways in birds. Nat Commun 2020;11:2476. [CrossRef]

- Spiers JG, Breda C, Robinson S, et al. Drosophila Nrf2/Keap1 Mediated Redox Signaling Supports Synaptic Function and Longevity and Impacts on Circadian Activity. Front Mol Neurosci 2019;12:86. [CrossRef]

- Ngo V, Duennwald ML. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022;11:2345. [CrossRef]

- He J, Hewett SJ. Nrf2 Regulates Basal Glutathione Production in Astrocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26:687. [CrossRef]

- Su H, Yang F, Fu R, et al. Cancer cells escape autophagy inhibition via NRF2-induced macropinocytosis. Cancer Cell 2021;39:678-693.e11. [CrossRef]

- Clement J, Wong M, Poljak A, et al. The Plasma NAD+ Metabolome Is Dysregulated in “Normal” Aging. Rejuvenation Res 2019;22:121–30. [CrossRef]

- Hong JY, Lin H. Sirtuin Modulators in Cellular and Animal Models of Human Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:735044. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Miguelez P, Looney J, Thomas J, et al. Sirt1 during childhood is associated with microvascular function later in life. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020;318:H1371–8. [CrossRef]

- Xie N, Zhang L, Gao W, et al. NAD+ metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:227. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Meza H, Vilchis-Landeros MM, Vázquez-Carrada M, et al. Cellular Compartmentalization, Glutathione Transport and Its Relevance in Some Pathologies. Antioxidants 2023;12:834. [CrossRef]

- Suh JH, Heath SH, Hagen TM. Two subpopulations of mitochondria in the aging rat heart display heterogenous levels of oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2003;35:1064–72. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Del Cerro E, Martinez de Toda I, Félix J, et al. Components of the Glutathione Cycle as Markers of Biological Age: An Approach to Clinical Application in Aging. Antioxidants 2023;12:1529. [CrossRef]

- Kim K. Glutathione in the Nervous System as a Potential Therapeutic Target to Control the Development and Progression of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Antioxidants 2021, Vol 10, Page 1011 2021;10:1011. [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund G, Peana M, Maes M, et al. The glutathione system in Parkinson’s disease and its progression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;120:470–8. [CrossRef]

- Krutetskaya ZI, Kurilova LS, Naumova AA, et al. Involvement of small G proteins and vesicle traffic in the glutoxim and molixan effects on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in macrophages. Doklady Biological Sciences 2014;457:252–4. [CrossRef]

- Muzurov K V., Antushevich AE, Antonov VG, et al. Molixan efficasy in acute severe corvalol poisoning. Emergency Medical Care 2017;18:73–7. [CrossRef]

- Krutetskaya ZI, Milenina LS, Naumova AA, et al. Phospholipase A2 inhibitors modulate the effects of glutoxim and molixan on the intracellular Ca2+ level in macrophages. Dokl Biochem Biophys 2015;465:374–6. [CrossRef]

- Krutetskaya ZI, Milenina LS, Naumova AA, et al. Sigma-1 receptor antagonist haloperidol attenuates Ca2+ responses induced by glutoxim and molixan in macrophages. Dokl Biochem Biophys 2017;472:74–6. [CrossRef]

- Freeman LC, Ting JP --Y. The pathogenic role of the inflammasome in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem 2016;136:29–38. [CrossRef]

- Buzanov D V., Lodyagin AN, Shikalova IA, et al. Peptidergic and adenosinergic drugs administration to comatose patients caused by alcohol consumption on early hospital period. Toxicological Review 2024;32:224–32. [CrossRef]

- Fimiani V, Cavallaro A, Ainis T, Baranovskaia G, Ketlinskaya O, Kozhemyakin L. Immunomodulatory effect of glutoxim on some activities of isolated human neutrophils and in whole blood. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2002;24(4):627-38. [CrossRef]

- Krutetskaya ZI, Melnitskaya AV, Antonov VG, Nozdrachev AD. Sigma-1 Receptor Antagonists Haloperidol and Chlorpromazine Modulate the Effect of Glutoxim on Na+ Transport in Frog Skin. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2019;484(1):63-65. [CrossRef]

- Krutetskaya ZI, Milenina LS, Naumova AA, Antonov VG, Nozdrachev AD. 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitor zileuton inhibits Ca(2+)-responses induced by glutoxim and molixan in macrophages. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2016;469(1):302-4. [CrossRef]

- Kozhemyakin LA, Chalisova NI, Ketlinskaya OS, Penniyainen VA, Komashnya AV, Nozdrachev AD. The effect of hexapeptide Glutoxim on tissue explant development in organoid cultures. Dokl Biol Sci. 2004;398:376-8. [CrossRef]

- Shikalova IA, Lodyagin AN, Antonov VG, et al. Results of a Multicenter Study on the Efficacy and Safety of Inosine Glycyl-Cysteinyl-Glutamate Disodium in the Treatment of Acute Ethanol Poisoning. Russian Sklifosovsky Journal “Emergency Medical Care” 2022;11:444–56. [CrossRef]

- Tomic A, Pollard AJ, Davis MM. Systems Immunology: Revealing Influenza Immunological Imprint. Viruses. 2021 May 20;13(5):948. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Liu L, Lu T, Sui Y, Zhang C, Wang Y, Zhang T, Xie Y, Xiao P, Zhao Z, Cheng C, Hu J, Chen H, Xue D, Chen H, Wang G, Kong R, Tan H, Bai X, Li Z, McAllister F, Li L, Sun B. Gut microbiota aggravates neutrophil extracellular traps-induced pancreatic injury in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Nat Commun. 2023 Oct 4;14(1):6179. [CrossRef]

- Kvetnoy I. Mitochondrial Proteins as Molecular Targets For Glutathione-Based Drugs. Am J Biomed Sci Res 2022;15:452–9. [CrossRef]

- Kvetnoy IM, Mironova ES, Krylova YS, et al. Mitochondria proteins of cardiomyocytes as molecular targets of the preparation V007. Molekulyarnaya Meditsina (Molecular Medicine) 2021;19:31–6. [CrossRef]

- Mironova E. Glutathione Medicines as Geroprotectors: Molecular Effects in Inflammaging Model. Am J Biomed Sci Res 2024;23:289–300. [CrossRef]

- Dilman В.М. The Grand Biological Clock (Science For Everyone) Mir Books. 1989. 208 p.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).