2.1. Determinants of Dynamic Capital Structure Adjustment

The study of optimal capital structure has evolved from a static to a dynamic framework, laying a solid theoretical foundation for this study. Early classical theories, such as the capital structure irrelevance theory (MM theory) proposed by Modigliani and Miller (1958) [

19] in the late 1950s and the subsequent introduction of the ‘taxed MM theory’, opened the way for modern capital structure research. Since then, preferential financing theory, agency theory, and static trade-off theory have been developed, which together reveal how internal factors such as taxes, bankruptcy costs, information asymmetry, and agency conflicts determine the static optimal capital structure.

However, the above static theories have difficulty in explaining why, in reality, firms' capital structures consistently deviate from the theoretical optimum. These theories also do not explain why firms do not immediately adjust to the target level. To fill this theoretical gap, Fischer et al. (1989) [

20] proposed the dynamic trade-off theory of capital structure. This theory states that firms are not always in the optimal state. Each firm has an optimal target capital structure. When a firm's capital structure deviates from this target, it will adjust its debt-to-equity ratios to bring them to, or close to, the target level [

9,

20,

21,

22]. Obviously, the more a firm's capital structure converges to the target, the more it favours enhancement of the firm's value [

23]. However, many factors affect how firms actually adjust their capital structures. These factors influence both the speed of adjustment [

8] and the extent to which actual structures deviate from targets [

24]. For example, firms incur adjustment costs due to market frictions such as agency costs and information asymmetry. Firms will only adjust their capital structure when the expected benefit exceeds the adjustment cost. The speed of adjustment depends on the balance between these benefits and costs [

25,

26,

27].

The focus of this study is primarily on external environmental factors affecting enterprises. Existing studies have shown that the macroeconomic environment [

9,

10,

28], the legal environment [

11], economic policy uncertainty [

12] and other factors have a significant impact on the adjustment of the capital structure of enterprises. For example, the macroeconomic environment affects the speed and scale of the adjustment of the capital structure of enterprises. Enterprises generally speed up the adjustment faster and on a larger scale in the boom period, and slowly adjust in the recession period [

9,

10,

28]. The institutional environment also plays an important role. Öztekin and Flannery (2012) [

11] found that the better the legal system, the smaller the adjustment cost and the faster the adjustment speed. Economic policy uncertainty makes it difficult for enterprises to predict future policies and government assistance, which may make enterprises adopt a more prudent capital structure strategy to avoid potential shock [

12]. Other factors, such as the marketization process and fiscal and monetary policy, are also found to have an impact on the capital structure decision-making of enterprises [

29,

30]. Firstly, the external environment can influence the investment opportunity of the enterprises, change the external business risk and capital demand of the enterprises, and thus influence the income of adjusting the capital structure [

28]. On the other hand, the change of external environment may influence the availability and cost of the financing, and thus the cost of the adjustment of the capital structure [

26]. These changes may, on affect the feasibility and convenience of adjusting the capital structure of the enterprises [

31].

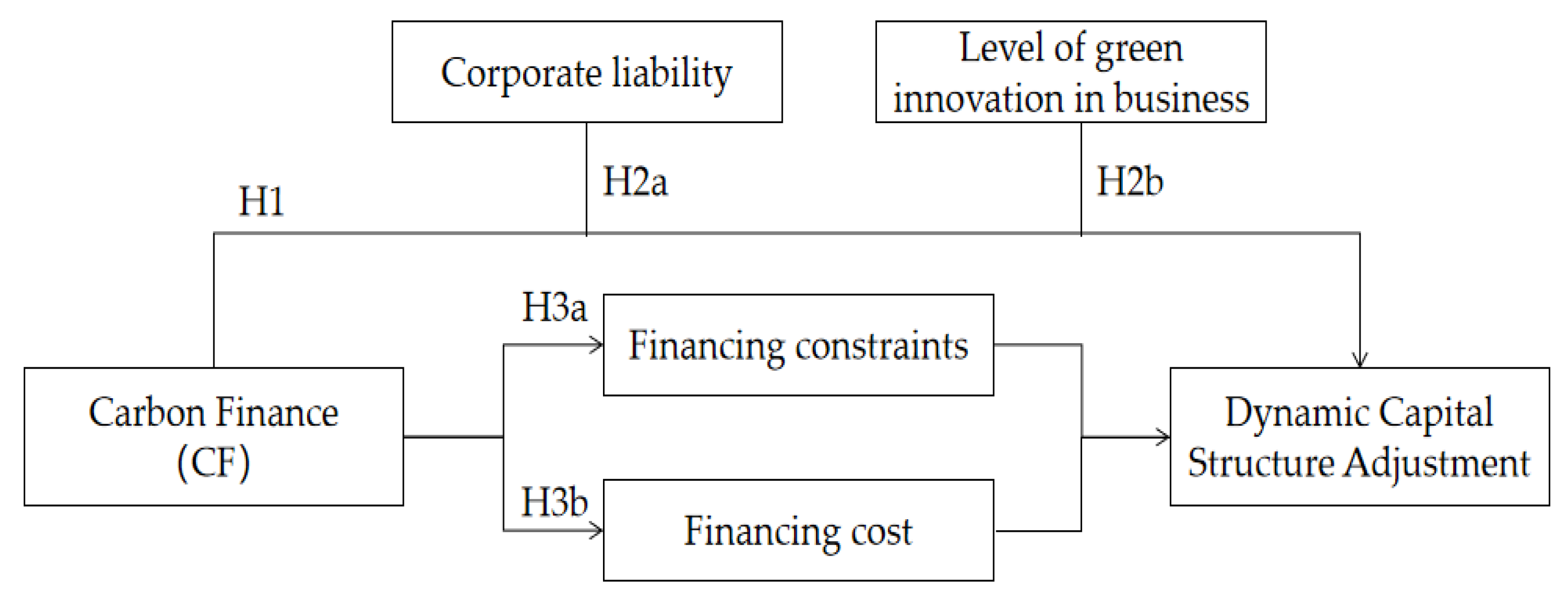

The results above show that dynamic capital structure adjustment is still a popular issue in the financial management of enterprises, which focuses on the influencing factors. As a new industry, carbon finance may have a significant impact on the external financial environment of enterprises. The study of how this changing environment leads to the change of capital structure provides a new research angle.

2.2. Research on the Impact of Carbon Finance on Enterprises

Global climate change is the most critical challenge for human society, and the transformation towards a low-carbon economy has become a strategic consensus of countries in this transition. It is the financial system that is engaged as an instrument of transformation. An effective financial system mobilizes and leverages social capital invested in energy-saving and emissions-reducing projects and in green low-carbon technologies. This provides vital financial support and innovative impetus for achieving global carbon neutrality. The concept of carbon finance originated in environmental finance at the end of the 20th century and has since become an emerging field as the low-carbon economy has developed [

32]. Scholars generally agree that carbon finance is a vital part of the global climate governance system and that its influence on the financial sector cannot be ignored [

33].

As an investment and financing activity focused on reducing carbon emissions, carbon finance centers on pricing carbon-emission rights through financial innovation. It guides the flow of funds to low-carbon technologies and applications and is attracting increasing attention from all quarters. Theoretically, academics have identified carbon finance as a key innovation in financial systems for addressing climate change. They have urged governments to formulate supporting policies to accelerate their adoption. In line with this, China has been developing the market since 2011 by launching carbon trading pilots in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Hubei, and Guangdong. These pilots began trading in 2013. After several years of smooth operation, they have accumulated valuable practical experience, laying a solid foundation for establishing a national carbon market. In this way, carbon finance actually connects the carbon market with the financial system, providing an international quality market mechanism for the price of carbon emissions rights. It also attracts social funds to the low-carbon sector by means of various financial instruments. In July 2017, the national carbon emissions rights trading market officially opened. Since then, it has developed rapidly and become the largest carbon market in the world, covering greenhouse gas emissions. This is a new stage of development in China's carbon finance, and it has great potential and far-reaching influence.

Carbon finance is attracting more and more scholars to study it profoundly. From a macro perspective, research abroad and at home on the effect of carbon finance has been carried out mainly about increasing carbon market capacity; also, the effects of reducing carbon emissions and stimulating macro-economic development have been investigated. Geng et al. (2022) [

34] state that carbon finance can promote green and inclusive economic growth by reconstructing the financial system. Fullerton and West (2002) [

35] found that carbon finance is a very rapidly growing subject which has already led to considerable reductions of greenhouse gases through ‘carbon trading and services’. Many studies have been made of the efficiency of carbon trading. Amongst others, the correctness of the following conclusions can be drawn from the studies carried out. Using a multi-actor general equilibrium model, Tang et al. (2015) [

36] found that trading in carbon emissions substantially reduced GHG emissions. Zhou and Li (2019) [

2] have seen that carbon finance helps reach low-price emissions reductions. Klemetsen et al. (2020) [

37] and Colmer et al. (2025) [

38] both found that schemes leading to trading in carbon emissions caused a substantial reduction in the emissions of the regulated factories, and enabled a direct effect on the level of emissions. Further from this, Gao (2023) [

39] used county based satellite data from China to show that carbon finance helps promote low-carbon economic growth to a further extent, and pointed to the importance of financial mechanisms. Ren and Fu (2019) [

40] have shown that measures like those referred to can also improve regional total factor productivity, leading thereby to greater economic effect. From the viewpoint of green economic efficiency Liao et al. (2020) [

41] have shown that carbon emissions trading causes green economic growth by stimulating innovation. These conclusions have been confirmed Jiang et al. (2023) [

7], who have seen that carbon finance is of great help to the attainment of qualitative high economic growth.

In addition to looking at the macro-level effects of carbon finance on emissions control and economic results, researchers have also studied the micro-level effects on the corporation with regard to profitability, corporate value, technology and R&D expenditures. Thus Chan et al (2013) [

42] studied the relationship between carbon emission rights versus corporate value, and found that carbon rights policies had a significantly positive influence on the value of major polluter enterprises. Oestreich and Tsiakas (2015) [

43] found that carbon trading raised cash flows for low-emission firms but increased risk on stock markets for high emissions firms. However, some contrary opinions exist. Koch and Bassen (2013) [

44] used a discounted cash flow (DCF) model, which demonstrated that most power companies had carbon risk premiums and capital costs post-entry into carbon trading schemes, which had an adverse effect on equity value. Shen and Huang (2019) [

15] using event study methodology also found that participation in corporate carbon trading activities enhanced firm value over the short term but that this was insignificant over the long term. On the impact of carbon finance on corporate technological innovation, the studies referred to in the literature tend overall to lend support to the view that there are indeed incentive effects. Calel and Dechezleprêtre (2016) [

45] report that enterprises taking part in carbon emissions trading showed appreciably higher levels of technological innovation. On the other hand, Chen et al (2017) [

46] found that the effects of carbon emissions trading were heterogeneous in their influence on the corporate innovation capacity, in that while there was a positive effect on the technic technological innovation workings, vis-a-vis regulated enterprises, there was an adverse effect among non-regulated enterprises. Extending this work, Lin et al (2018) [

47] examined the effects of the Chinese carbon trading market on the corporate technological innovation, this from the viewpoint of carbon pricing, finding that this drew both a promotional effect and a dislocation effect, the higher the carbon price, the more did the promotional effect of the carbon trading system exert a positive dynamism on technological innovation. In terms of methodology, Cui et al (2018) [

48] used a triple difference approach to examine the effects of carbon emission rights and concluded that pilot carbon trading schemes tended to enhance low-carbon technological innovation among enterprises. Particularly it was revealed that this effect of stimulating innovation was even greater the more the pilot carbon trading activity went on. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2019) [

49] confirmed that pilot enterprises exhibited significantly higher levels of low-carbon innovation following the implementation of carbon trading pilot schemes. Further examining market conditions, Hu et al. (2020) [

50] demonstrated that the catalytic role of carbon emission rights in corporate technological innovation is more pronounced in markets with greater liquidity and reduced product competition. Regarding R&D expenditure, numerous scholars have also conducted research. For example, Liu and Zhang (2017) [

51] demonstrated that carbon emission rights effectively stimulate R&D expenditure among pilot enterprises, particularly among large-scale firms. Further confirmation that carbon emissions trading pilot schemes primarily motivate corporate innovation through product R&D and cost channels was provided by Guo and Xiao (2020) [

52], effectively boosting R&D investment among micro-enterprises.

However, there remains a notable gap in research regarding the influence of carbon finance on corporate financing decisions as a financial tool in addressing firms’ decision-making. Our research is most closely connected to Campiglio (2016) [

53], who gives the best general understanding of the function of green finance in low-carbon financing through real analysis of carbon finance. In this paper, Campiglio (2016) [

53] notes the opportunity to discuss concrete obstacles related to corporate behaviors of transition to low-carbon, a possible problem of high risk and low return in the innovation link. Campiglio (2016) [

53] proposes the establishment of new-specific financial institutions or of confirmed additional capital market policies distinct from the normal structures of interest rates to meet financial supply purposes. This research emphasizes the fact that if carbon finance makes advancement possible, it can reduce financial constraints a lot in the progress of time of transition to low-carbon. We have widened this literature again to think over the profit within the variable constitutional financial structure of the carbon finance.