1. Introduction

Tinnitus is the experience of sound without the presence of an external stimulus [

1]. Individuals experiencing tinnitus report an unspecified acoustic sound such as ringing, pulsing, buzzing, or clicking [

2]. Episodes of tinnitus may be acute (single-episode), intermittent, or chronic persistent (defined as lasting at least 3 months), which can last for many years [

3,

4]. Risk factors include hearing loss, ototoxic medication, head injury, and depression [

5] Due to variations in the definition of tinnitus and differences in studied populations, reported prevalence varies. In a 2022 meta-analysis of 83 publications, the pooled prevalence of any tinnitus was 14.4% among the general population worldwide, suggesting that tinnitus affects more than 740 million adults globally and is perceived as a distressing symptom by more than 120 million people [

6]. This percentage corresponds with the findings of the European Tinnitus Survey (12 countries; n=11 427), in which the pooled prevalence of any tinnitus was 14.7%. In the same survey, 16.5% of respondents in Poland reported experiencing any form of tinnitus, and 5.8% reported experiencing "bothersome" tinnitus [

7]. A second epidemiological survey of adults in Poland (n=10 349) found that tinnitus lasting more than 5 minutes was reported by 20.1% of the population and constant tinnitus was reported by 4.8% [

8].

Tinnitus is a heterogeneous condition, with some people experiencing only mild discomfort and others having a significant negative impact on their cognitive abilities and emotional state [

1,

9]. It can lead to sleep disturbance and concentration problems [

10] which can have a negative impact on quality of life [

9]. It can also be exacerbated by audiovestibular symptoms such as hearing loss. In addition, the intensity and chronicity of tinnitus symptoms are perpetuated by comorbidities such as stress, anxiety, or depressive mood [

11,

12].

Therefore, treatment strategies for chronic tinnitus must be interdisciplinary. To date, there is no causal therapy of chronic tinnitus and no recommendation for drug therapy in national and international clinical practice guidelines. Cognitive behavioural therapy has the highest level of evidence for reducing tinnitus-related distress.

In Germany and other countries, medicinal products containing EGb 761

® - the dried extract of Ginkgo biloba leaves - as active substance are approved for the symptomatic or adjuvant treatment of patients with tinnitus of vascular or involutive origin. A mediation analysis indicated that EGb 761

® could be considered as an adjunctive treatment for tinnitus in elderly patients with dementia, with additional benefit in those with symptoms of depression or anxiety [

13]. The present exploratory study investigated whether these comorbidities influence the effectiveness of EGb 761

® in chronic tinnitus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The primary objective of this multicentre, single-arm, open-label, exploratory clinical trial was to investigate whether comorbidities influence the treatment effect of EGb 761

® in terms of improvement and response rates. The secondary objective was to identify the patient groups that would derive the greatest benefit from EGb 761

® treatment. The publication manuscript was written in accordance with the STROBE checklist (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) [

14].

The trial comprised a screening visit up to seven days prior to enrolment, a baseline visit, a control visit after 12 weeks, and a final study visit at week 24 ± 1. Telephone calls were scheduled for weeks 6 and 18 to assess adverse events and changes in concomitant medications. At the initial screening stage, patients underwent a diagnostic evaluation of tinnitus, encompassing an ear, nose, and throat examination. Subsequently, patients’ subjective hearing acuity was assessed with pure tone audiometry across a range of frequencies and volumes. At each study visit (baseline, week 12, and week 24), patients completed various questionnaires (see below).

2.2. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Silesian Medical Chamber in Katowice and conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was prospectively registered at ISRCTN – The UK’s Clinical Study Registry (ISRCTN83863387, registration date October 14, 2016).

2.3. Participants

Patients were recruited in 12 investigational sites specialised to otorhinolaryngology or internal medicine in Poland between October 2016 and April 2017. Adults with unilateral or bilateral chronic tinnitus lasting for at least 3 months rated as grade 2 or 3 according to the Biesinger classification [

15], with or without hearing loss, were eligible for inclusion., The criteria for the Biesinger classification are:

Grade 2: tinnitus is mainly perceived in silence and is bothersome when the patient is under stress or strain.

Grade 3: tinnitus causes permanent impairment of the patient’s personal and professional life; there is also presence of an emotional, cognitive, or physical disorder.

Patients were excluded if they had tinnitus due to Ménière’s disease, vestibular schwannoma, otosclerosis, acute or chronic otitis media or acute vestibular neuritis. Patients were also excluded if they had received cognitive behavioural therapy or tinnitus retraining within six months of the baseline visit, had an ongoing psychiatric illness or severe cardiac, circulatory, renal or hepatic disease, or had received any other treatment for tinnitus within two weeks of the baseline visit.

2.4. Trial Medication

Patients were instructed to take one film-coated tablet containing 120 mg of the proprietary extract EGb 761® (manufactured by Dr. Willmar Schwabe in Karlsruhe, Germany) twice daily for 24 weeks. EGb 761® is a dry extract from the leaves of the Ginkgo biloba tree. One film-coated tablet is adjusted to contain 26.4–32.4 mg of ginkgo flavonoids and 6.48–7.92 mg of terpene lactones.

2.5. Outcomes

The main outcomes related to tinnitus were the 52-item version of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) [

16], the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) [

17], and the 11-point box scales for tinnitus loudness and tinnitus annoyance at week 12 and week 24 and their differences to baseline. The 11-point box scales range from 0 (indicating the absence of tinnitus, or a lack of annoyance, respectively) to 10 (representing the perception of extremely loud tinnitus or a high level of annoyance, respectively). It is a variant of the visual analogue scale, which is a valuable tool for assessing subjective experiences in individuals with chronic tinnitus [

18]. Furthermore, the abbreviated TQ Mini score, comprising 12 items, was calculated to evaluate whether the abbreviated scale would be helpful in future research. It is easier to complete and has been shown to have similar qualities in terms of reliability and discriminatory power [

19]. The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) is a self-report instrument designed to assess functional impairment in work, home, and family responsibilities on a 10-point numerical rating scale [

20].

The assessment of anxiety and depression was conducted using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [

21]. A HADS anxiety subscore of 11 points or more was considered to indicate anxiety, while a score of less than 11 points was defined as normal or subsyndromal anxiety. A HADS depression subscore of 8 points or less was defined as normal, while scores of 8 points or more were defined as either subsyndromal or abnormal. Stress levels were measured with a validated Polish translation of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ). The questionnaire comprises 30 items, designed to assess subjective stress experienced over the preceding four weeks. From the sum score, an index can be derived which ranges from 0 to 1 [

22]. An index of < 0.45 was defined as no stress, while an index ≥ 0.45 was considered as abnormal stress level.

Pure tone audiometry (air conduction) was used to determine the subject’s hearing thresholds. This method involves the application of a range of frequency-specific pure tones to which the patient responds. Patients were classified according to World Health Organisation criteria. They were considered mildly impaired if their hearing threshold (average of 500 Hz, 1000 Hz, 2000 Hz and 4000 Hz in the better ear) was 26–40 decibel hearing level (dB HL), moderate impairment 41–60 dB HL and severe impairment was 61–80 dB HL [

23]. A binary variable was used for the analysis which distinguishes between no impairment (25 dB and less) and at least slight hearing impairment (26 dB and above).

For the responder analysis, a ‘slight’ response was defined as an improvement of at least 15% between baseline and week 24, while a ‘moderate’ response was defined as an improvement of at least 30%. This is reasonable, given that a minimally clinically important difference of 12 points is considered for the total TQ score change from baseline [

24]. With a baseline score of almost 40 in the study population, this equates to an improvement of around 30%. The ‘overall response’ criterion was defined as an improvement of at least 30% in three of the four main treatment outcomes.

Safety and tolerability outcomes included the frequency and nature of adverse events (AEs) and the results of the physical examination, safety laboratory tests (haematology, clinical chemistry including liver function and blood coagulation parameters), and vital signs which were documented at screening and week 24.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

In view of the absence of clarity regarding the factors that influence the treatment effect of EGb 761®, no confirmatory hypothesis was formulated. Consequently, no formal sample size calculation was carried out. A number of 160 patients plus about 10% potential drop-outs, in total 175 patients seemed adequate for the analyses.

TQ total score, THI total score, tinnitus loudness and tinnitus annoyance as the main treatment outcomes were assessed through the implementation of an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model. In this model, the value observed at each follow-up visit served as the dependent variable, while the baseline value was utilised as a covariate. The TQ mini score and the SDS total score were analysed in the same way.

Any missing values at week 24 were replaced by the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. For variables composed of single-item variables, the LOCF was applied on an item-by-item basis. Missing values at week 12 were not replaced by baseline values.

Continuous outcomes were described by the number of evaluable observations (N), arithmetic mean (mean) and standard deviation (SD). P-values of the ANCOVA models are presented.

Baseline characteristics and safety outcomes are presented by absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and by means with standard deviations for continuous variables.

The treatment effects were examined in subgroups defined by baseline comorbidities, namely anxiety, hearing impairment, stress and depression. The differences of treatment effects between subgroups with and without hearing impairment, with and without depression or stress are presented by adjusted means, standard errors of adjusted means, and p-values for changes within subgroups as well as adjusted means differences, standard errors of adjusted mean differences, and p-values for the comparison of subgroups. The comparison of treatment effects between patients with and without anxiety was performed without adjustment for baseline scores.

Responder rates are presented as percentages based on the sample size of the full analysis set. Overall responders were characterized using stepwise regression analysis with the prognostic factors ‘age’, ‘sex’ and the baseline comorbidities hearing loss, anxiety (HADS anxiety, categorized), stress (PSQ, categorized) and depression (HADS depression, categorized). The significance levels for entry into the model and for staying in the model were set to alpha = 0.1. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals and p-values were computed for factors included into the logistic regression model.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.4). P-values <0.05 are considered statistically significant. no adjustment has been made for multiplicity, on account of the exploratory nature of the analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

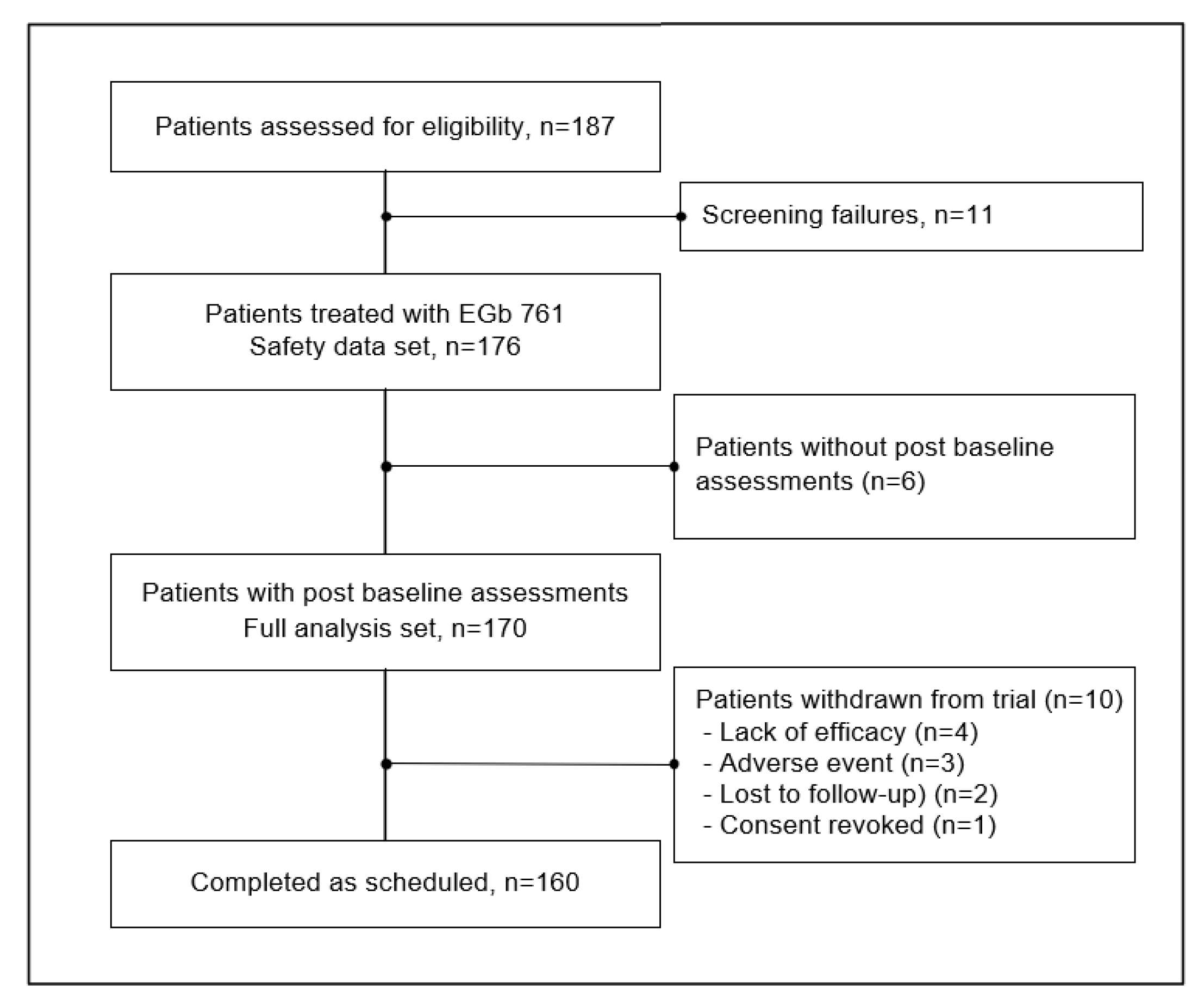

In total, 187 patients were recruited of which eleven did not successfully complete the screening phase. The remaining 176 patients started treatment with EGb 761® (safety set). A total of 16 (9.1%) patients terminated the trial prematurely during the active treatment phase. The study duration was between 9 and 210 days with a mean of 163.4 days and a standard deviation of 33.5 days (safety set, n=176). Six patients were excluded from efficacy analyses since no measurements of the efficacy outcomes after baseline were available. The full analysis set thus included 170 patients (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). For 6 of these patients no efficacy outcomes in week 12 were available and for 5 patients no efficacy assessments took place at the end of the treatment period (week 24). Missing values in week 24 were replaced by the last observation carried forward to analyse all patients taking their individual treatment periods into account. Unless otherwise stated, all results are presented for the full analysis set. Baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden..

Figure 1.

Disposition of subjects, analysis data sets.

Figure 1.

Disposition of subjects, analysis data sets.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics.

| Parameter |

Total (N=170) |

Age (years)

Mean ± SD

Min, max |

51.6 ± 13.0

21, 82 |

Gender

Female

Male |

62 (36.5%)

108 (63.5%) |

Tinnitus characteristics, n (%)†

Bilateral

Permanent

Duration > 1 year

|

87 (51.2%)

149 (87.6%)

138 (81.2%) |

| Comorbidities |

Patients with hearing impairment, n (%)

No impairment

At least mild impairment |

118 (69.4%)

52 (30.6%) |

HADS anxiety, n (%)

Normal or subsyndromal (0–10 points)

Abnormal (11–21 points)

HADS anxiety, mean ± SD |

135 (79.4%)

34 (20.0%)

7.7 ± 3.9 |

HADS depression, n (%)

Normal (0–7 points)

Subsyndromal or abnormal (8–21 points)

HADS depression, mean ± SD |

111 (65.3%)

58 (34.1%)

5.5 ± 4.0 |

PSQ (stress index), n (%)

Normal (< 0.45)

Abnormal (≥ 0.45)

PSQ stress index, mean ± SD |

112 (65.9%)

58 (34.1%)

0.389 ± 0.159 |

3.2. Effectiveness Outcomes

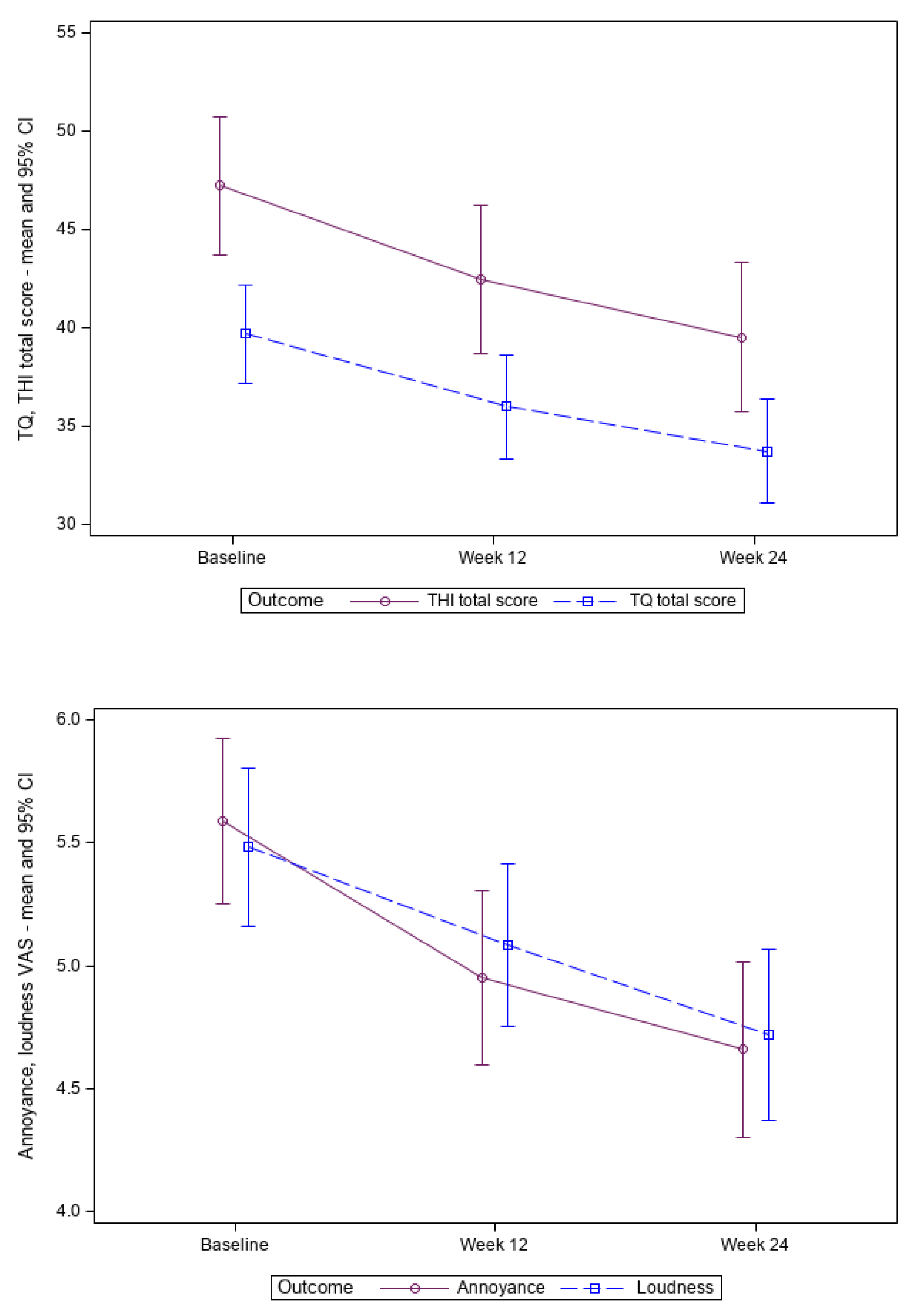

The mean values of the variables employed to assess treatment effects – the TQ total score, TQ mini, THI total score, 11-Point Box Scales for tinnitus loudness and tinnitus annoyance – exhibited a continuous decrease until weeks 12 and 24, in comparison to the baseline values (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). The difference was found to be significant at both time points (range p<0.0001 to p=0.0011, Fehler!Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). This pattern demonstrated a continuous improvement in symptoms (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.).

The SDS total score decreased from mean 8.3 points (FAS) at baseline by -1.0 ± 4.8 (SD) points until week 12 and by -1.9 ± 5.7 (SD) points until week 24, which was statistically significant (p≤0.0158 for both visits).

Table 2.

Overall treatment effects – baseline scores and improvements at weeks 12 and 24.

Table 2.

Overall treatment effects – baseline scores and improvements at weeks 12 and 24.

| Outcomes |

Baseline

(N=170) |

Improvement, Week 12

(N =164)* |

Improvement, Week 24

(N =170) |

| |

Mean (± SD) |

Mean (± SD) |

p-value |

Mean (± SD) |

p-value |

| TQ (points) |

39.7 (± 16.5) |

-3.8 (± 9.7) |

p<0.0001 |

-6.0 (± 11.9) |

p<0.0001 |

| TQ mini (12 items) |

12.4 (± 5.3) |

-1.3 (± 3.5) |

p<0.0001 |

-2.1 (± 4.2) |

p<0.0001 |

| THI (points) |

47.2 (± 23.4) |

-4.7 (± 14.7) |

p=0.0001 |

-7.7 (± 17.3) |

p<0.0001 |

| Loudness (points) |

5.5 (± 2.1) |

-0.4 (± 1.7) |

p=0.0011 |

-0.8 (± 1.9) |

p<0.0001 |

| Annoyance (points) |

5.6 (± 2.2) |

-0.7 (± 1.9) |

p<0.0001 |

-0.9 (± 2.0) |

p<0.0001 |

Figure 2.

TQ total score, THI total score, tinnitus loudness and annoyance during the trial (mean and 95% confidence interval). Abbreviations: THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire.

Figure 2.

TQ total score, THI total score, tinnitus loudness and annoyance during the trial (mean and 95% confidence interval). Abbreviations: THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire.

3.3. Subgroup Analyses by Comorbidities

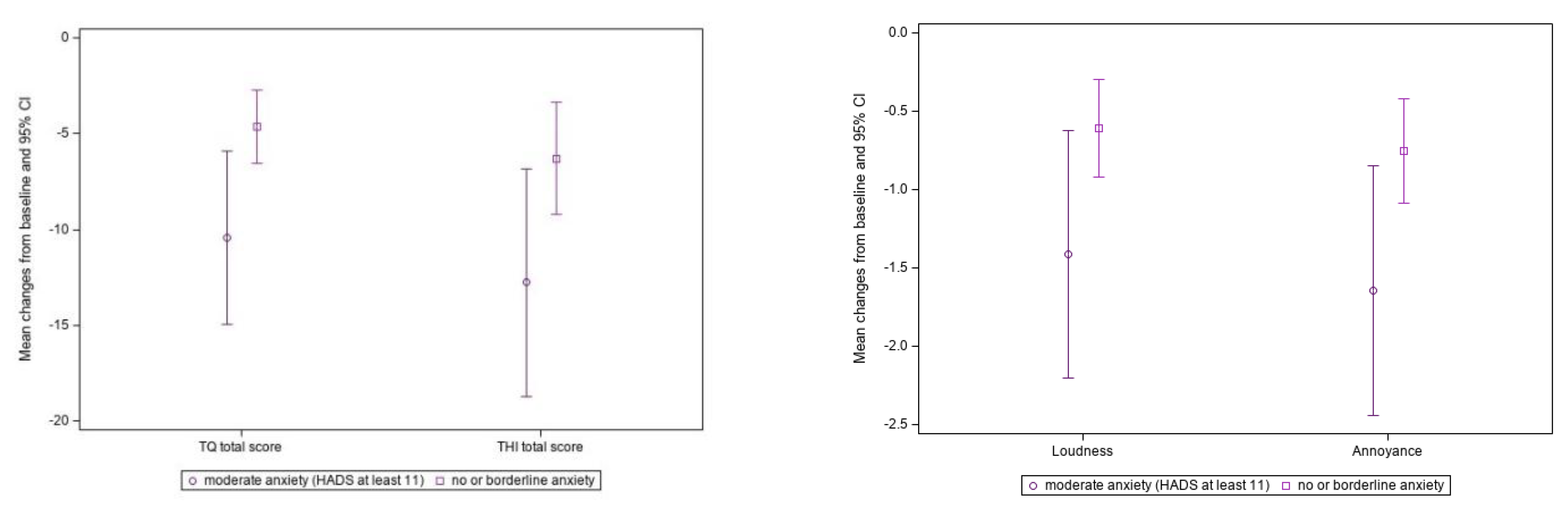

In patients with HADS anxiety scores ≥ 11 points, and in patients with subsyndromal or no anxiety, there was a significant improvement in TQ, TQ mini, THI, tinnitus loudness and tinnitus annoyance scores between baseline and week 24 (p < 0.001 for all endpoints in both subgroups) (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). Furthermore, the group with anxiety exhibited a significantly greater improvement in TQ, TQ mini and tinnitus annoyance compared to the group without or with subsyndromal anxiety (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden., Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.).

At baseline, 42 patients had mild hearing loss, 8 had moderate hearing loss and 2 had severe hearing loss. The remaining 118 patients had no hearing impairment (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden., Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). Changes of efficacy outcomes are more pronounced in the subgroup of patients without hearing impairment compared to patients with at least mild hearing loss. The analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the subgroups in terms of change in TQ total score, THI total score, tinnitus loudness and annoyance (p>0.05). Regarding the 12 items of the TQ mini (short version of the TQ), there is a statistically significant difference between the subgroups (p=0.0486).

The effect of stress was examined using the PSQ index threshold of 0.45 (

Table S1,

Figure S1 in the Supplemental File). In the subgroups of patients with and without stress, TQ, TQ mini, THI, tinnitus loudness, and tinnitus annoyance scores decreased significantly (p ≤ 0.001 for all endpoints in both groups) by week 24. A statistically significant difference was observed in the reduction of tinnitus loudness (p = 0.0478) and tinnitus annoyance (p = 0.0403) at week 24 between the group of patients with a PSQ stress index of ≥0.45 and those with a PSQ stress index of < 0.45, indicating that patients with higher stress levels showed greater improvement.

In patients with and without abnormal HADS depression scores at baseline (

Table S2 in Supplemental File), TQ, THI, tinnitus loudness, and tinnitus annoyance scores improved significantly by week 24 (p ≤ 0.001 for all endpoints in both groups). There were no significant differences between patients with and without depression (p > 0.05 for all endpoints); patients improved to a similar extent, regardless of baseline depression.

Table 3.

Analysis of the influence of baseline anxiety on EGb 761® treatment effects.

Table 3.

Analysis of the influence of baseline anxiety on EGb 761® treatment effects.

| Outcomes |

Patients with Anxiety,

HADS ≥ 11 (n=34) |

Patients with Subsyndromal or no Anxiety,

HADS < 11 (n=135) |

Group Difference†

|

| |

Baseline

Mean ± SD

|

Improvement, Week 24

Mean ± SD, p-Value*

|

Baseline

Mean ± SD

|

Improvement, Week 24

Mean ± SD, p-Value*

|

p-Value† |

| TQ (points) |

51.0 ± 14.6 |

-10.4 ± 13.0, p<0.0001 |

35.3±14.8 |

-4.6 ± 11.2, p=0.0005 |

0.0211 |

| TQ mini (points) |

16.1 ± 4.4 |

-3.5 ± 4.3, p<0.0001 |

11.4 ± 5.1 |

-1.6 ± 4.1, p<0.0001 |

0.0263 |

| THI (points) |

66.5 ± 19.4 |

-12.8 ± 17.0, p=0.0001 |

42.3±22.2 |

-6.3 ± 17.3, p<0.0001 |

0.0536 |

| Loudness (points) |

6.1 ± 2.1 |

-1.4 ± 2.3, p=0.0009 |

5.2±2.0 |

-0.6 ± 1.8, p=0.0002 |

0.0606 |

| Annoyance (points) |

6.6 ± 2.1 |

-1.6 ± 2.3, p=0.0002 |

5.4±2.1 |

-0.8 ± 1.9, p<0.0001 |

0.0418 |

Figure 3.

Treatment effects in patients without/subsyndromal anxiety versus those with anxiety. Abbreviations: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire. (p= 0.0211/0.0.0533/0.0606/0.0408 for TQ total score/THI total score/tinnitus loudness/annoyance comparing patients with anxiety and patients with subsyndomal or no anxiety.).

Figure 3.

Treatment effects in patients without/subsyndromal anxiety versus those with anxiety. Abbreviations: HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire. (p= 0.0211/0.0.0533/0.0606/0.0408 for TQ total score/THI total score/tinnitus loudness/annoyance comparing patients with anxiety and patients with subsyndomal or no anxiety.).

3.4. Responder Analysis

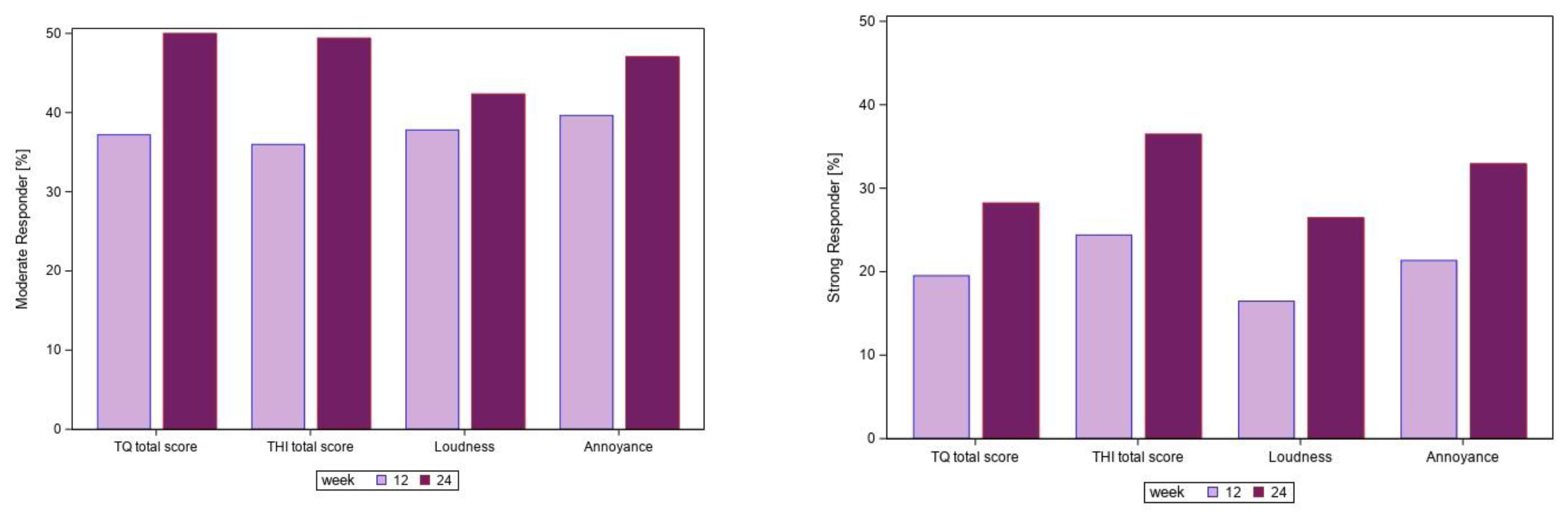

At week 24, the proportion of patients with at least 30% improvement ranged from 26.5% for tinnitus loudness to 36.5% for THI. Nearly half of the patients (42.4% for tinnitus loudness, 50% for TQ) exhibited an improvement from baseline between 15% and 30%. Approximately 50% of the patients did not experience a meaningful improvement. The results of the responder analysis are presented in Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.

An improvement of at least 30% between baseline and week 24 in at least 3 of the 4 main efficacy outcomes (overall response) was observed for 32 of 170 patients (18.8%). The most significant factors contributing to treatment response were identified as no hearing loss (odds ratio [OR] of 4.42, 95% CI [1.42; 13.70], p = 0.0102) or anxiety (HADS anxiety ≥11 points, OR of 2.62, 95% CI [1.05; 6.54], p = 0.0391). The other factors which might be correlated with anxiety or hearing impairment were not selected in the stepwise logistic regression analysis. In total 20 patients without hearing impairment suffered from anxiety. Eight of these patients (40.0%) were overall responders (improvement of at least 30% between baseline and week 24 in at least 3 of the 4 main efficacy outcomes).

Figure 4.

Responder analysis – percentage of patients with a slight or moderate response at weeks 12 and 24 (N=170).Abbreviations: THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire.

Figure 4.

Responder analysis – percentage of patients with a slight or moderate response at weeks 12 and 24 (N=170).Abbreviations: THI, Tinnitus handicap inventory; TQ, Tinnitus questionnaire.

3.5. Safety

The treatment of chronic tinnitus with EGb 761® over 24 weeks was safe and well tolerated. The mean exposure was 159 ± 35.5 days (safety analysis set, n=176). The mean drug compliance was 97.2 ± 9.3%. During treatment and the following 2 days after the last dose of EGb 761®, 37 patients (21.0%) experienced a total of 52 adverse events (AEs). The majority was classified as mild or moderate in intensity.

The most common AEs (independently of the associated causality assessment) were upper respiratory tract infection (n=6), pharyngitis (n=5), headache (n=3), palpitations (n=2), bronchitis (n=2), and influenza (n=2). One patient experienced a serious AE (acute renal colic due to urolithiasis) that was considered as unrelated to EGb 761®.

A total of 19 AEs occurred in 15 patients for which a causal relationship with EGb 761® could not be excluded and the causal relationship for the vast majority was assessed as unlikely. The most common AEs were nervous system disorders (n=4), gastrointestinal disorders and general disorders (n=3 each). All ADRs were mild or moderate in intensity and resolved by the end of the study or during follow-up. and the causal relationship for the vast majority was assessed as unlikely.

No statistically significant alterations in mean, minimum, or maximum laboratory parameters were observed between the screening visit and the week 24 visit. Heart rate and mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were similar before and after treatment with EGb 761®. No changes were observed in the physical examinations throughout the study, except for one patient who had pain and swelling of the thyroid gland at week 24. The patient was diagnosed with subacute thyroiditis, which was documented to be unrelated to EGb 761®.

4. Discussion

The present trial showed significant improvements in the main tinnitus-related outcomes (TQ total score, 12-item TQ mini, THI total score, 11-Point Box Scales for tinnitus loudness and tinnitus annoyance) after 24 weeks of treatment with EGb 761® in patients with chronic tinnitus. Noteworthy, at baseline more than 80% of patients reported a tinnitus duration of more than one year. These results indicate the effectiveness of EGb 761® in tinnitus management, regardless of the duration of the condition.

Score reductions in tinnitus-relevant measures in this study demonstrated improvements in tinnitus loudness/severity and overall severity in about half of the patients. However, statistically significant effects are not necessarily clinically relevant [

25,

26]. Positive effects should therefore be confirmed in a randomized controlled study. The good safety and tolerability of EGb 761

® demonstrated in this study are consistent with the results of previous studies and reviews [

27].

A post-hoc analysis of pooled data (n = 594) from older adults with tinnitus and mild to moderate dementia has demonstrated a close link between tinnitus, depression and anxiety [

13]. The analysis suggests that anxiety and depression may influence tinnitus severity. In the subgroup analysis of comorbidities, patients with baseline anxiety, normacusis and elevated stress level showed a significantly better response in the TQ mini. The reduction of the THI of 12.8 ± 17.0 (mean ± SD) in patients with baseline anxiety, of 8.6 ± 1.6 (adjusted mean ± SE) in patients with normal hearing and of 8.2 ± 2.3 (adjusted mean ± SE) in stressed individuals was in the range of the minimal clinically important difference of 7.8 to 12 points [

28]. In this study, baseline depression had no impact on the treatment outcomes with EGb 761

® whereas a retrospective cohort study indicated that depression severity is a predictor for treatment (other than EGb 761

®) success [

29].

An improvement of at least 30% in at least 3 of the 4 main efficacy outcomes defined as overall response was observed for 18.8% of patients. For patients without hearing loss and high anxiety levels an overall response rate of 40% was observed. These patients benefited particularly from treatment with EGb 761®.

In this study, treatment response was seen in patients with anxiety and those without hearing loss. In the latter, decreased inhibition due to partial cochlear neural degeneration is thought to trigger hyperactivity in the central nervous system as a possible pathogenetic mechanism [

30]. The mechanism of action of EGb 761

® may involve a global inhibitory process that helps to counteract tinnitus. In an animal model of noise-induced tinnitus, three weeks of treatment with EGb 761

® resulted in an improvement in behavioural signs of tinnitus that was accompanied by a persistent recovery of auditory thresholds back to pre-trauma conditions. Auditory brainstem response wave analyses indicated an increase in response to low stimulus intensities and a decrease to high intensity stimulation in EGb 761

® treated animals [

31].

Dysregulation of neurotransmitters [

32] including dopamine is involved in the pathogenesis of tinnitus as well as in mood disorders such as anxiety, stress or depression [

33]. In a rat stress model, EGb 761

® normalises brain dopamine and norepinephrine levels in the brain and plasma stress hormones. Enhancement of the dopaminergic system by EGb 761

® has been reported both in animals and isolated cochlea cells. Moreover, cholinergic neurotransmission is modulated by repeated administration likely via elevating muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the hippocampus [

32]. Results from a placebo-controlled clinical trial of EGb 761

® in older adults with subjective memory impairment also suggested an enhancement of prefrontal dopaminergic activity [

34]. Consistent with these findings, the dopaminergic drugs pramipexole, sulpiride, and melatonin have been reported to improve subjective tinnitus [

35,

36]. However, these data require further evaluation and have not been incorporated into treatment guidelines.

Other studies investigating the efficacy of Ginkgo biloba extracts for the treatment of tinnitus have yielded mixed results. In a randomised controlled trial, EGb 761

® and pentoxifylline were similarly effective in reducing tinnitus loudness and annoyance [

37]. An older systematic literature review of eight placebo-controlled trials concluded that EGb 761

® was significantly more effective than placebo in the treatment of tinnitus [

38]. A review of 15 studies using different Ginkgo biloba products for the treatment of tinnitus found conflicting results [

39], and a Cochrane review of 2022 concluded that there is uncertainty about the benefits and harms of Ginkgo biloba for the treatment of tinnitus when compared to placebo [

40]. However, the efficacy of a plant extract depends on its composition, which is influenced by the manufacturing process, the bioavailability of its active compounds, and its dosage [

41]. Products made from the same plant species using different production processes may not be bioequivalent and thus findings from studies of one specific extract should not be generalised to other products and vice versa [

41].

There are several limitations to the interpretation of trial results. In general, studies without randomisation and without control groups have inherent biases, making it difficult to assess the effect of treatment. In addition to pharmacological effects, non-specific effects and the natural history of the disease may have contributed to the outcome. The design was chosen as it reflects the treatment situation in everyday clinical practice with the aim of generating hypotheses and descriptive statistical analysis. Since there is limited information on whether causes, risk factors, chronicity, characteristics of tinnitus and associated features influence the treatment effect of EGb 761®, this approach is reasonable. Consistent results from analyses of different tinnitus-related outcomes support the validity and integrity of the data. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to further investigate the hypotheses generated by this study.

5. Conclusions

Treatment with EGb 761® significantly improved all tinnitus-related outcomes for nearly half of the patients with chronic tinnitus. The enhancement of a central inhibitory mechanism may underlie the clinical effect. Patients without hearing loss and high levels of anxiety demonstrated the most favourable treatment response. Therefore, EGb 761® treatment for chronic tinnitus could be an interesting option for these patients.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L., I.U., P.S. and S.S.; investigation G.L., I.U., P.S., S.S., B.M. and P.B.; data curation, G.L., I.U., P.S., S.S., B.M. and P.B.; formal analysis, S.S., B.M., P.B.; writing—original draft preparation B.M., P.B. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, G.L., I.U., P.S., S.S., B.M. and P.B.; visualization, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The trial, medical writing services, and publication were funded by Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The three randomized clinical trials included in this analysis were performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the relevant Ethics Committees (Ethics Committee of the Ukraine State Pharmacological Centre, No. 5.12-153/KE, 27 May 2003; Ethics Committee of the Ukraine State Pharmacological Centre, No. 5.12-523/KE, 26 December 2005; Ethics Committee of the Federal Service on Surveillance in Healthcare and Social Development of the Russian Federation, No. EK-33848, 20 May 2008).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the clinical trials that were included in this analysis. All patient data used in this research was provided in anonymized form.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because raw data cannot be shared both due to ethical reasons and to data protection laws. To the extent permitted by law, the study data required for validation purposes have been disclosed on corresponding databases. Reasonable requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research and its subsequent publication were funded by Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Conflicts of Interest

GL, IU, PS received grants for the conduct of the trial and honoraria from Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany. SS is an employee of Dr. Willmar Schwabe GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany. PB and BM declare nor competing interests.

References

- Van Hoof, L.; Kleinjung, T.; Cardon, E.; Van Rompaey, V.; Peter, N. The correlation between tinnitus-specific and quality of life questionnaires to assess the impact on the quality of life in tinnitus patients. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 969978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, B.; Hesse, G.; Sattel, H.; Kratzsch, V.; Lahmann, C.; Dobel, C. S3 Guideline: Chronic Tinnitus: German Society for Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery e. V. (DGHNO-KHC). HNO 2022, 70, 795–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkart, M.; Brueggemann, P.; Szczepek, A.J.; Frank, D.; Mazurek, B. Intermittent tinnitus-an empirical description. HNO 2019, 67, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langguth, B.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Cederroth, C.R. Therapeutic Approaches to the Treatment of Tinnitus. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 59, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguley, D.; McFerran, D.; Hall, D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013, 382, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarach, C.M.; Lugo, A.; Scala, M.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Cederroth, C.R.; Odone, A.; Garavello, W.; Schlee, W.; Langguth, B.; Gallus, S. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Tinnitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.; Lugo, A.; Akeroyd, M.A.; Schlee, W.; Gallus, S.; Hall, D.A. Tinnitus prevalence in Europe: A multi-country cross-sectional population study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022, 12, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabijanska, A.; Rogowski, M.; Bartnik, G.; Skarzynski, H. Epidemiology of tinnitus and hyperacusis in Poland. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Tinnitus Seminar; The Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Centre: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 415–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rademaker, M.M.; Essers, B.A.B.; Stokroos, R.J.; Smit, A.L.; Stegeman, I. What Tinnitus Therapy Outcome Measures Are Important for Patients?- A Discrete Choice Experiment. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 668880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Gallus, S.; Hall, D.A.; Kleinjung, T.; Langguth, B.; Maruotti, A.; Meyer, M.; Norena, A.; Probst, T.; Pryss, R.; et al. Editorial: Towards an Understanding of Tinnitus Heterogeneity. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, B.; Boecking, B.; Dobel, C.; Rose, M.; Brüggemann, P. Tinnitus and Influencing Comorbidities. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 2023, 102, S50–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinska-Blizniewska, H.; Olszewski, J. [Tinnitus and depression]. Otolaryngol Pol 2009, 63, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, P.; Grando Sória, M.; Brandes-Schramm, J.; Mazurek, B. The influence of depression, anxiety and cognition on the treatment effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® in patients with tinnitus and dementia: A mediation analysis. J Clin Med 2021, 10, 3151–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 2007, 4, e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, E.; Heiden, C.; Greimel, V.; Lendle, T.; Hoing, R.; Albegger, K. [Strategies in ambulatory treatment of tinnitus]. HNO 1998, 46, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, W.; Goebel, G. A psychometric study of complaints in chronic tinnitus. J Psychosom Res 1992, 36, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.W.; Jacobson, G.P.; Spitzer, J.B. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996, 122, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamchic, I.; Langguth, B.; Hauptmann, C.; Tass, P.A. Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am J Audiol 2012, 21, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueggemann, P.; Goebel, G.; Boecking, B.; Hofrichter, N.; Rose, M.; Mazurek, B. [Analysis of items on the short forms of the tinnitus questionnaire: Mini-TQ-12 and Mini-TQ-15]. HNO 2023, 71, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Harnett-Sheehan, K.; Raj, B.A. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996, 11, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale--a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997, 42, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenstein, S.; Prantera, C.; Varvo, V.; Scribano, M.L.; Berto, E.; Luzi, C.; Andreoli, A. Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res 1993, 37, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Davis, A.C.; Hoffman, H.J. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull World Health Organ 2019, 97, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.A.; Mehta, R.L.; Argstatter, H. Interpreting the Tinnitus Questionnaire (German version): What individual differences are clinically important? Int J Audiol 2018, 57, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.A.; Haider, H.; Szczepek, A.J.; Lau, P.; Rabau, S.; Jones-Diette, J.; Londero, A.; Edvall, N.K.; Cederroth, C.R.; Mielczarek, M.; et al. Systematic review of outcome domains and instruments used in clinical trials of tinnitus treatments in adults. Trials 2016, 17, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boecking, B.; Brueggemann, P.; Kleinjung, T.; Mazurek, B. All for One and One for All? - Examining Convergent Validity and Responsiveness of the German Versions of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ), Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), and Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI). Front Psychol 2021, 12, 596037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Schlaefke, S. Efficacy and tolerability of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® in dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Interv Aging 2014, 9, 2065–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelke, M.; Basso, L.; Langguth, B.; Zeman, F.; Schlee, W.; Schoisswohl, S.; Cima, R.; Kikidis, D.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Bruggemann, P.; et al. Estimation of Minimal Clinically Important Difference for Tinnitus Handicap Inventory and Tinnitus Functional Index. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukas, C.F.; Mazurek, B.; Brueggemann, P.; Junghofer, M.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Dobel, C. A retrospective two-center cohort study of the bidirectional relationship between depression and tinnitus-related distress. Commun Med 2024, 4, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilkov, V.; Caswell-Midwinter, B.; Zhao, Y.; de Gruttola, V.; Jung, D.H.; Liberman, M.C.; Maison, S.F. Evidence of cochlear neural degeneration in normal-hearing subjects with tinnitus. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 19870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, P.; Tziridis, K.; Buerbank, S.; Schilling, A.; Schulze, H. Therapeutic Value of Ginkgo biloba Extract EGb 761(R) in an Animal Model (Meriones unguiculatus) for Noise Trauma Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0157574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.W.; Lehner, M.D.; Dietz, G.P.H.; Schulze, H. Pharmacologic treatments in preclinical tinnitus models with special focus on Ginkgo biloba leaf extract EGb 761®. Mol Cell Neurosci 2021, 116, 103669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecina, M.; Sikora, M.; Avery, E.T.; Heffernan, J.; Pecina, S.; Mickey, B.J.; Zubieta, J.K. Striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor-mediated neurotransmission in major depression: Implications for anhedonia, anxiety and treatment response. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 27, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S.M.; Ruge, H.; Schindler, C.; Burkart, M.; Miller, R.; Kirschbaum, C.; Goschke, T. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® on cognitive control functions, mental activity of the prefrontal cortex and stress reactivity in elderly adults with subjective memory impairment - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Hum Psychopharmacol 2016, 31, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Santiago, A.M.; Esteban-Ortega, F. Sulpiride and melatonin decrease tinnitus perception modulating the auditolimbic dopaminergic pathway. J Otolaryngol 2007, 36, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sziklai, I.; Szilvassy, J.; Szilvassy, Z. Tinnitus control by dopamine agonist pramipexole in presbycusis patients: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Laryngoscope 2011, 121, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, K.; Šejna, I.; Skutil, J.; Hahn, A. Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761® versus pentoxifylline in chronic tinnitus: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2018, 40, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Boetticher, A. Ginkgo biloba extract in the treatment of tinnitus: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2011, 7, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, D.; Han, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, X.; Dong, Y. Herbal medicines in the treatment of tinnitus: An updated review. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1037528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereda, M.; Xia, J.; Scutt, P.; Hilton, M.P.; El Refaie, A.; Hoare, D.J. Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, 11, CD013514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulic, Z.; Lehner, M.D.; Dietz, G.P.H. Ginkgo biloba leaf extract EGb 761((R)) as a paragon of the product by process concept. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1007746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).