1. Introduction

As mobile robots and autonomous driving systems continue to expand into complex environments, the requirements for accuracy and robustness in long-term autonomous navigation using Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) systems have become increasingly stringent [

1]. Odometry, as the fundamental pose estimation module of SLAM, is susceptible to cumulative drift caused by sensor noise, environmental dynamics, and data association errors [

2,

3].Without timely correction, this drift can lead to map distortion and trajectory deviation, ultimately resulting in navigation failure. Loop Closure Detection (LCD) serves as a global constraint mechanism by identifying when a robot revisits a previously mapped location, making it a key technique for correcting accumulated errors and maintaining global consistency between the map and trajectory [

4].

Existing loop closure detection methods can be categorized into three types according to sensor modality: LiDAR-based, vision-based, and multi-sensor fusion approaches. LiDAR-based methods rely on high-precision 3D geometric information, exhibiting strong stability under varying illumination and in textureless scenes. Representative works such as Scan Context [

5], Scan Context++ [

6], and Contour Context [

7] construct global descriptors to enable fast matching. However, due to the inherent sparsity of LiDAR point clouds, these methods struggle to represent spatial features adequately in long-range or unstructured environments, which may result in missed loop detections [

8]. Vision-based methods [

9] leverage the rich texture and color information of images to distinguish between visually similar scenes, yet they are highly sensitive to illumination changes and seasonal variations, often suffering from a significant drop in matching accuracy under strong lighting, rain, or other adverse weather conditions [

10].

Each single-sensor modality has its limitations in specific environments.Nevertheless, LiDAR and vision sensors are inherently complementary: LiDAR provides stable, illumination-invariant 3D geometric structures, while cameras capture fine-grained texture details to distinguish similar structures [

11,

12]. Most existing fusion methods operate at the feature level, where image and point cloud features are independently extracted and then aligned or associated via homomorphic transformation [

13], projection [

14], or attention mechanisms [

15] to achieve cross-modal integration. In contrast, decision-level fusion methods combine independent detection results from different sensors to avoid false matches caused by single-sensor noise, effectively leveraging their respective advantages to enhance overall robustness [

16,

17].

To address the limitations of single-modality systems and the shortcomings of existing fusion strategies, this paper proposes a LiDAR–vision deep fusion loop closure detection algorithm. The primary objective is to establish a tight correlation between geometric and textural information, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of loop detection in complex environments.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Spatiotemporal Alignment and Depth Completion Framework: A unified process is designed to achieve spatial alignment of LiDAR point clouds and camera images via extrinsic calibration, handle sampling rate discrepancies through timestamp interpolation, and complete depth estimation of visual keypoints using neighborhood search. This enables the construction of 3D visual features as a foundation for cross-modal fusion.

Hybrid Feature Descriptor Construction: A fusion descriptor combining LiDAR geometric triangle descriptors (representing spatial topology) and visual BRIEF descriptors (representing local texture) is developed. Efficient loop candidate retrieval is achieved via hash indexing, balancing matching efficiency and discriminability. An improved RANSAC-based geometric verification method is further introduced to suppress noise and reduce false matches.

Comprehensive Evaluation on Public Datasets: Extensive experiments are conducted on the KITTI and NCLT datasets to validate the proposed algorithm’s effectiveness across urban, mixed indoor–outdoor, and seasonally varying environments, demonstrating its potential as a robust solution for long-term autonomous navigation in SLAM systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Loop Closure Detection Based on Single Modality

LiDAR-based loop closure detection methods can generally be divided into two categories: direct point cloud matching and feature descriptor matching. Direct matching methods such as ICP [

18] and NDT [

19] estimate relative poses by iteratively optimizing point correspondences , but their high computational cost makes them unsuitable for real-time applications. Descriptor-based methods extract global or local features to reduce data dimensionality and have become the mainstream approach. Among global descriptor methods, Scan Context [

5] projects 3D point clouds into an azimuth–radial grid and encodes the maximum height in each cell to achieve rotation-invariant matching. Scan Context++ [

6] further improves robustness by introducing sub-descriptors to handle translation and rotation sensitivity, but its adaptability to non-spherical LiDARs remains limited. Local descriptor methods such as LinK3D [

20] and BoW3D [

8] employ a Bag-of-Words (BoW) framework that utilizes local geometric features for fast retrieval. However, in sparse regions, feature redundancy can lead to false detections. Map Closure [

21] constructs LiDAR density maps for loop detection, showing strong viewpoint robustness, but compressing 3D structures into 2D maps leads to loss of spatial information and incomplete scene representation [

22].

Vision-based loop closure detection, typically formulated as Visual Place Recognition (VPR), identifies revisited locations through image feature matching. Among local feature methods, SURF [

23] achieves scale and rotation invariance but is computationally expensive. ORBcombines FAST corner detection and BRIEF descriptors, balancing efficiency and robustness, and is widely used in systems such as ORB-SLAM [

1]. Global feature methods such as HOG [

24] and PHOG [

25] capture image gradient distributions to describe structural information but are sensitive to local detail changes. To improve efficiency, researchers have proposed Bag-of-Words (BoW) models such as DBoW2 [

9], which use K-means clustering to build a visual vocabulary and TF–IDF weighting to enhance discriminability for fast retrieval. However, BoW models suffer from a fixed vocabulary problem, limiting generalization to unseen scenes. FAB-MAP 2.0 [

26] introduces probabilistic modeling of word co-occurrence to improve large-scale adaptability, but its reliance on SURF features leads to slow extraction, restricting real-time performance.

2.2. LiDAR–Vision Fusion for Loop Closure Detection

Multimodal fusion methods combine LiDAR geometric information with visual texture to overcome the limitations of single modalities. According to the fusion level, these methods can be categorized as feature-level fusion and decision-level fusion. Decision-level fusion methods, such as MSF-SLAM [

16], integrate LiDAR and visual loop closure results through logical operations (e.g., OR fusion). Although this improves robustness, it fails to fully exploit cross-modal feature correlations and remains vulnerable to false detections caused by a single modality. iBTC [

27] introduces binary visual descriptors to assist LiDAR matching and achieves real-time performance but lacks deep feature-level interaction.

Feature-level fusion methods have received greater attention. CoRAL [

12] generates elevation maps from LiDAR data and fuses them with projected RGB image features, aggregating multimodal representations via a NetVLAD layer. However, this approach depends heavily on deep learning and large amounts of labeled data. MinkLoc++ [

28] designs a specialized feature extraction module that jointly learns point cloud and image features to generate multimodal descriptors, but it is sensitive to calibration errors. BEV Fusion [

11] projects image features onto a bird-eye-view (BEV) plane for fusion with LiDAR BEV features, though projection bias can occur in non-flat terrains. Additionally, some approaches incorporate attention mechanisms [

29] to model cross-modal dependencies, but their high computational complexity limits their use on embedded platforms.

In summary, existing fusion approaches still face challenges such as low cross-modal alignment accuracy, insufficient feature fusion depth, and limited robustness. To address these problems, this paper proposes a LiDAR–vision deep fusion loop closure detection algorithm that integrates spatiotemporal alignment, depth completion, hybrid descriptor construction, and improved RANSAC-based geometric verification, providing a novel solution for enhancing loop closure detection performance.

3. Method

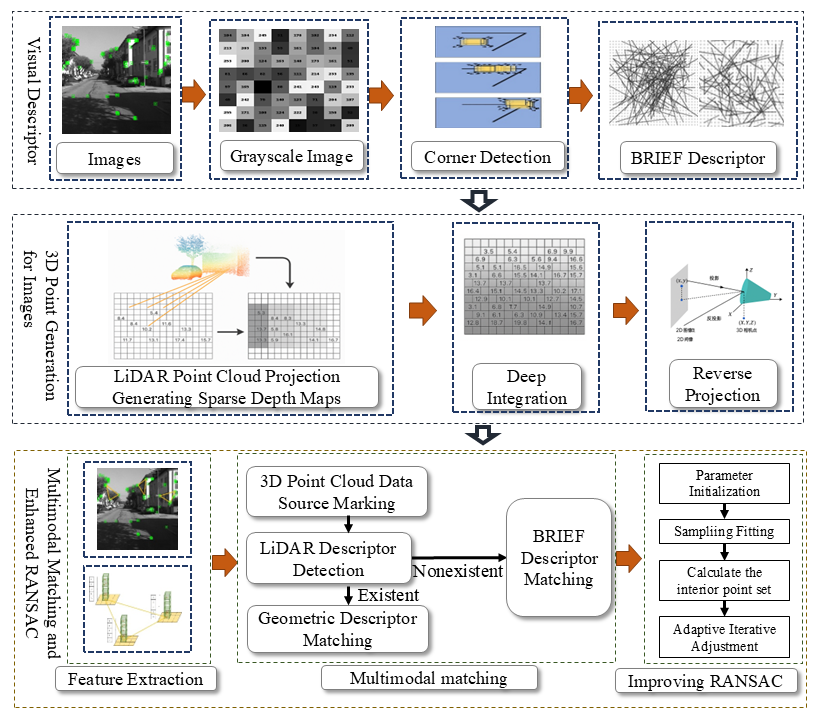

Figure 1 illustrates the algorithm workflow. First, Harris corners are detected from input images with BRIEF descriptors extracted. Depth information of keypoints is obtained via LiDAR point cloud projection to generate a sparse depth map, where invalid depths are completed to form a fused depth map, which is then back-projected into 3D space. Triangular descriptors with binary descriptors are constructed based on LiDAR and visual keypoints. For matching, LiDAR geometric descriptors are prioritized, with visual descriptors used as supplements when unavailable. An improved RANSAC algorithm is applied for geometric verification, incorporating a matching error weighting mechanism to enhance matching accuracy and robustness of transformation estimation.

3.1. Visual Feature Extraction and Depth Completion

Harris corner detection identifies corners by analysing grey-level changes within local windows [

30]. For each detected Harris keypoint, N random pairs of pixels

are sampled within its neighborhood, and a binary test is defined as:

where

denotes the grey-scale intensity of pixel

p . The concatenation of all

N binary tests forms the BRIEF descriptor, which is compact in storage and enables efficient matching.

After projecting LiDAR points onto the image plane, the generated depth map contains many blank areas, requiring depth completion for visual keypoints. This process begins with

spatiotemporal alignment of the LiDAR and camera data. Because LiDAR and camera operate at different sampling frequencies, for each image frame, two LiDAR scans with timestamps closest to the image are found, and linear interpolation is applied to obtain the interpolated LiDAR point cloud at the image timestamp, ensuring temporal consistency. Given the extrinsic calibration parameters, each LiDAR point

is transformed into the camera coordinate system

as:

where

and

are the rotation matrix and translation vector from LiDAR to camera, respectively.

For depth completion, a neighborhood search is applied: a sparse depth map records the LiDAR-derived depth for each pixel. For keypoints without valid depth, the nearest valid depth pixel within a window is found and assigned to the keypoint; if no valid value exists, the keypoint is discarded to prevent invalid matches.

According to the pinhole camera model, each keypoint with completed depth

is back-projected into 3D space as a visual keypoint

:

where

denote the pixel coordinates, and

are the intrinsic parameters of the camera.

3.2. Multimodal Feature Fusion and Matching

To fuse LiDAR geometric and visual texture features, triangular descriptors are constructed based on LiDAR keypoints and 3D visual keypoints, respectively. For LiDAR triangular descriptors: after preprocessing LiDAR point clouds, FAST corner detection is used to extract keypoints. For each keypoint, two neighboring keypoints are selected to form a triangle, with three side lengths calculated and vertex height encodings recorded to form geometric descriptors. For visual triangular descriptors: triangles are constructed from 3D visual keypoints using the same method, with side lengths calculated and vertex BRIEF descriptors recorded to form visual texture descriptors.

For LiDAR keypoint extraction: first, LiDAR scans are accumulated into submaps, which are voxelized. Voxels belonging to planes are identified based on the proportion of planar points, then merged into larger planes. Non-planar voxels are projected onto adjacent planes along their normals to form projection images. Keypoints are extracted by finding pixels with the highest density in local regions of these images, denoted as .

The hash key for the constructed LiDAR and visual triangle descriptors is computed as

where

,

p is a large prime number and

B denotes the hash table size. For each triangular descriptor in the current frame, the hash key is calculated to retrieve similar descriptors from the hash table. The top 50 candidate loop frames are selected based on descriptor similarity (using height-encoded Hamming distance for LiDAR and BRIEF Hamming distance for vision).

3.3. Improved RANSAC-Based Geometric Verification

Traditional RANSAC estimates the transformation matrix by randomly sampling point pairs and using a fixed threshold to determine inliers, which makes it sensitive to noise and mismatches [

31]. To improve robustness, a weighted error mechanism is introduced. For each candidate correspondence pair

, the transformation

maximizing the weighted inlier count is found as

where

is a weight function defined as

and

is a decay parameter controlling the influence of error magnitude on the weight. This soft weighting allows each correspondence to contribute proportionally to its residual, improving stability in noisy data.

Finally, validated loop constraints are incorporated into the SLAM pose graph for global optimization. In the graph, nodes represent robot keyframe poses

, and edges represent odometry and loop constraints. The optimization objective is formulated as

where

and

denote the sets of odometry and loop-closure edges, respectively, and

and

are the corresponding error terms. This optimization corrects accumulated drift and ensures global trajectory consistency within the SLAM system.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup and Datasets

We evaluated the proposed algorithmic framework on two publicly available datasets: the KITTI dataset [

32] and the NCLT dataset [

33]. For the KITTI dataset, sequences 00, 02, 05, 07, and 08 were selected, which contain 10 Hz 64-line LiDAR point clouds and 10 Hz camera image data. For the NCLT dataset, sequences NCLT1 (2012-01-15), NCLT2 (2012-05-26), NCLT3 (2012-11-04), and NCLT4 (2012-12-01) were used, which contain 10 Hz 32-line LiDAR point clouds and 5 Hz camera image data. In the experiments, we compared our method with four representative algorithms: the density-map-based Map Closure [

21], the BEV contour–based Contour Context [

7], the bag-of-words–based DBoW2 [

9], and the binary feature–aided fusion method iBTC [

27]. All experiments were conducted on a consumer-grade desktop computer running Ubuntu 20.04, equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400 CPU and 16 GB RAM.

The evaluation metrics used to assess loop closure detection performance include Precision, Recall, and F1-score, which are defined as , , and , respectively. Here, TP denotes the number of correctly detected loops (true positives), FP denotes the number of false loop detections (false positives), and FN denotes the number of missed loops (false negatives).

4.2. Results on the KITTI Dataset

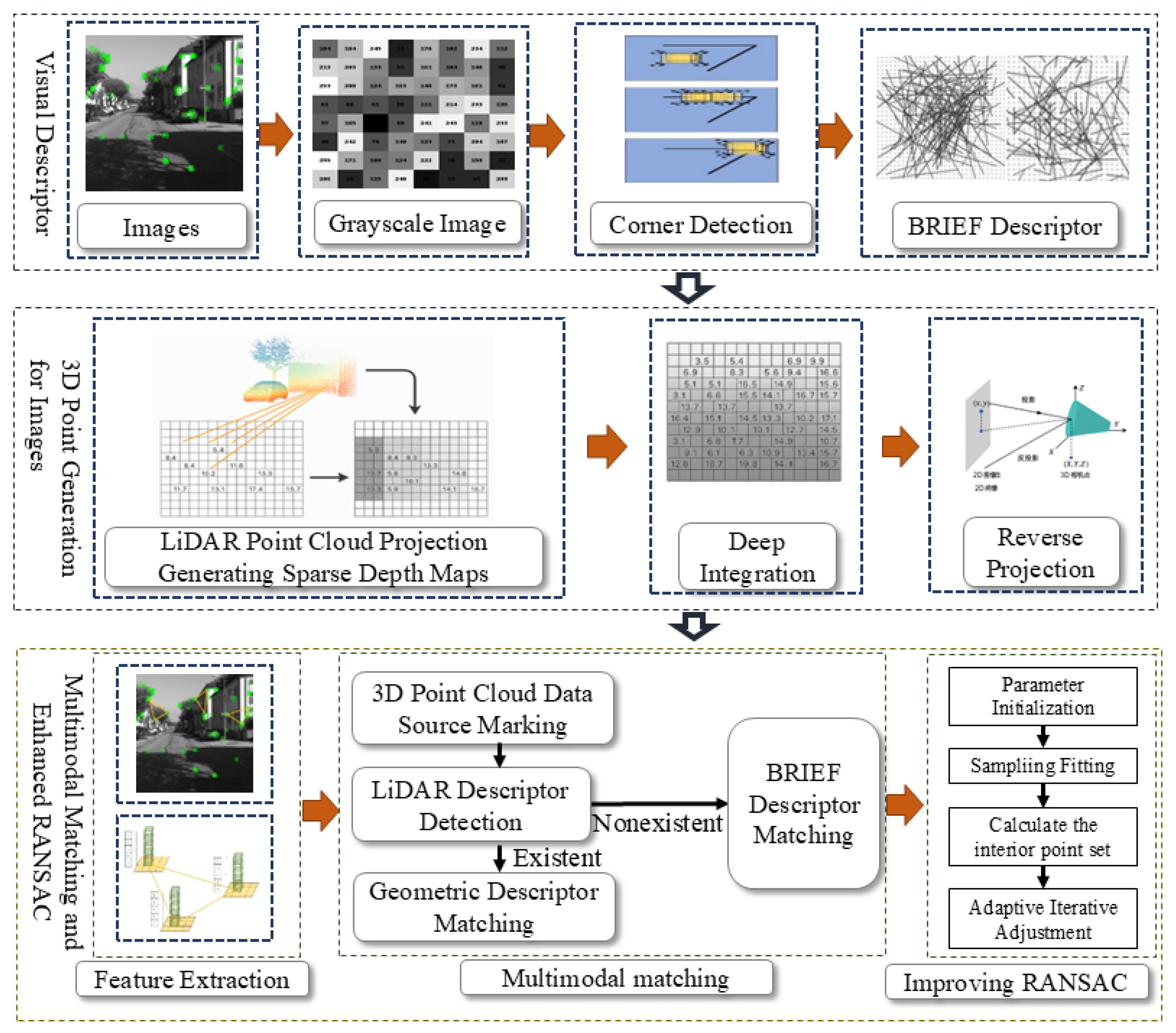

Table 1 compares the F1-scores of various algorithms on KITTI00, KITTI02, and KITTI05 sequences. The proposed algorithm achieves the highest F1-score across all three sequences, with an average of 85.28%, showing significant improvements over the LiDAR-only Map Closure and vision-only DBoW2. This is attributed to enhanced cross-modal feature correlation via depth completion, which leverages multi-sensor advantages to boost detection accuracy and robustness.

Figure 2 presents the Precision-Recall (PR) curves for each sequence. The proposed algorithm exhibits a larger enclosed area in most cases, maintaining higher precision at the same recall rate, thus outperforming others in loop closure detection performance.

Table 2 demonstrates the impact of incorporating vision into the original algorithm. It shows that the proposed algorithm, after fusing vision, increases the number of detections across all four sequences by an average of 5.25, with the maximum similarity improved by 0.38% on average. This verifies that radar-vision fusion enhances the robustness of loop closure detection. For instance, in the KITTI02 sequence with extensive tree occlusion (resulting in incomplete LiDAR point cloud features), the algorithm successfully detects more loops by supplementing visual textures.

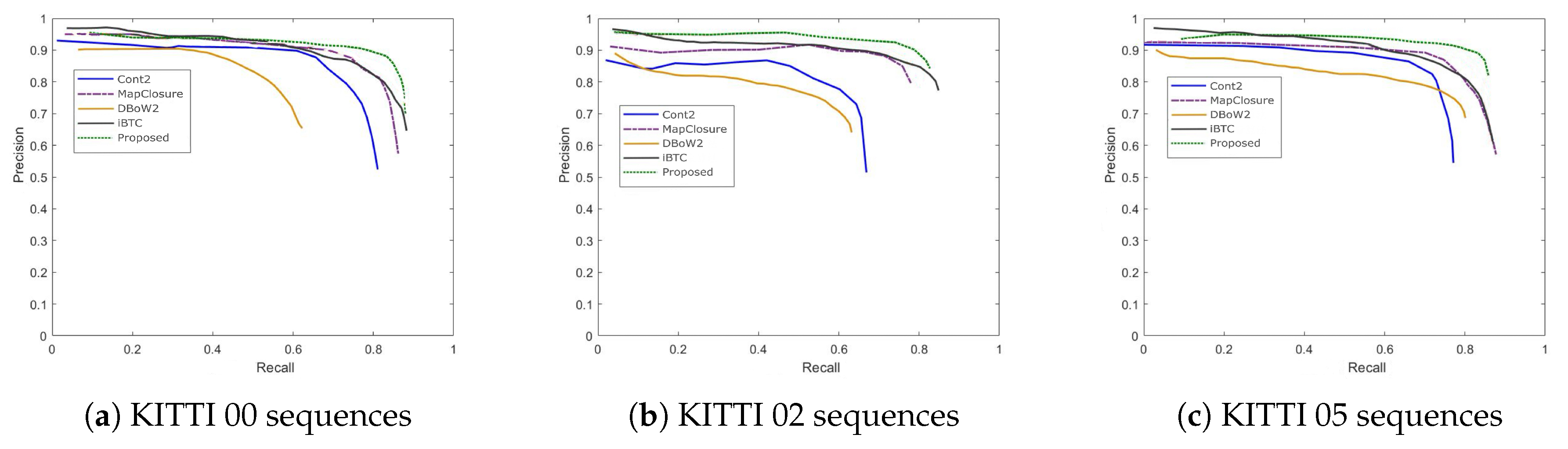

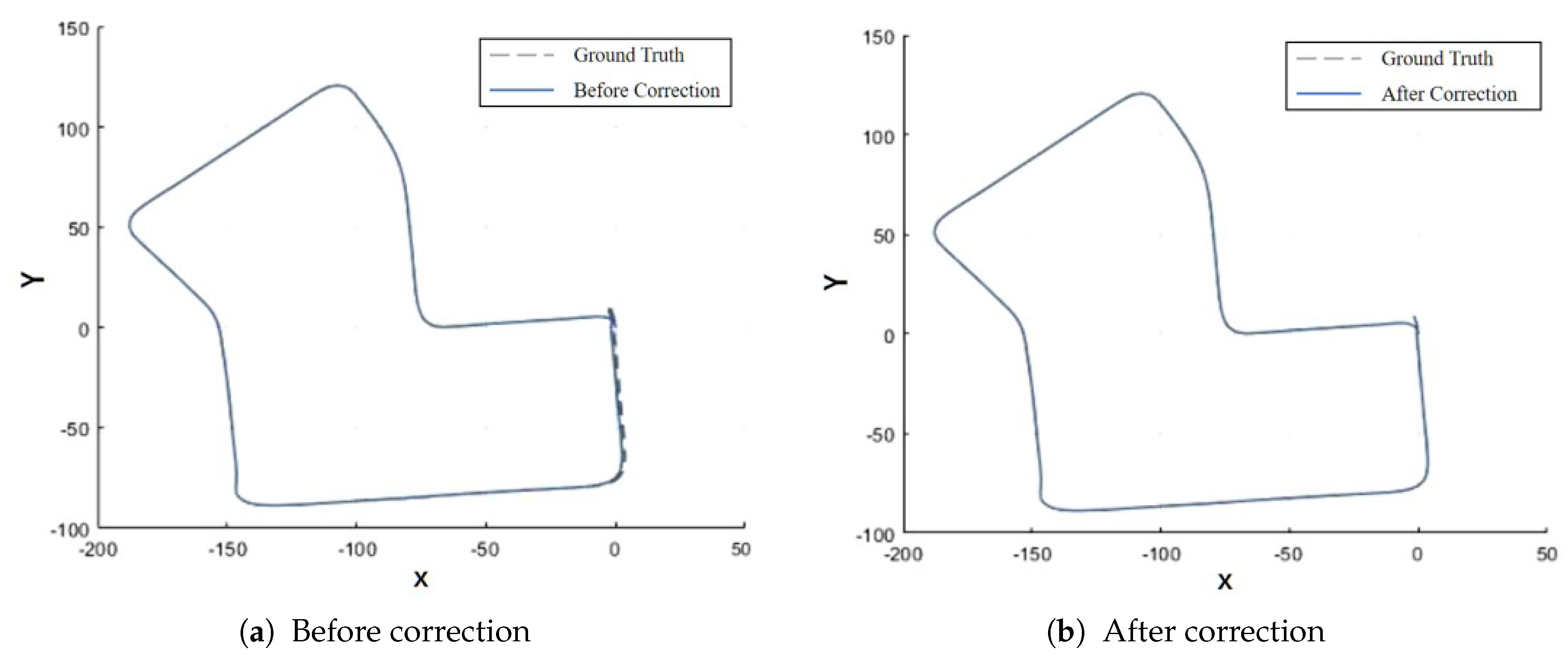

Table 3 shows the comparison of ATE before and after loop closure correction for the KITTI07 sequence when the proposed algorithm is applied to the SLAM system, with trajectory comparisons presented in

Figure 3. The corrected trajectory aligns better with the ground truth, especially in the loop region where the start and end points coincide (KITTI07 sequence). Cumulative errors are effectively suppressed: the endpoint offset reduces from 0.8m before correction to 0.4m after correction.

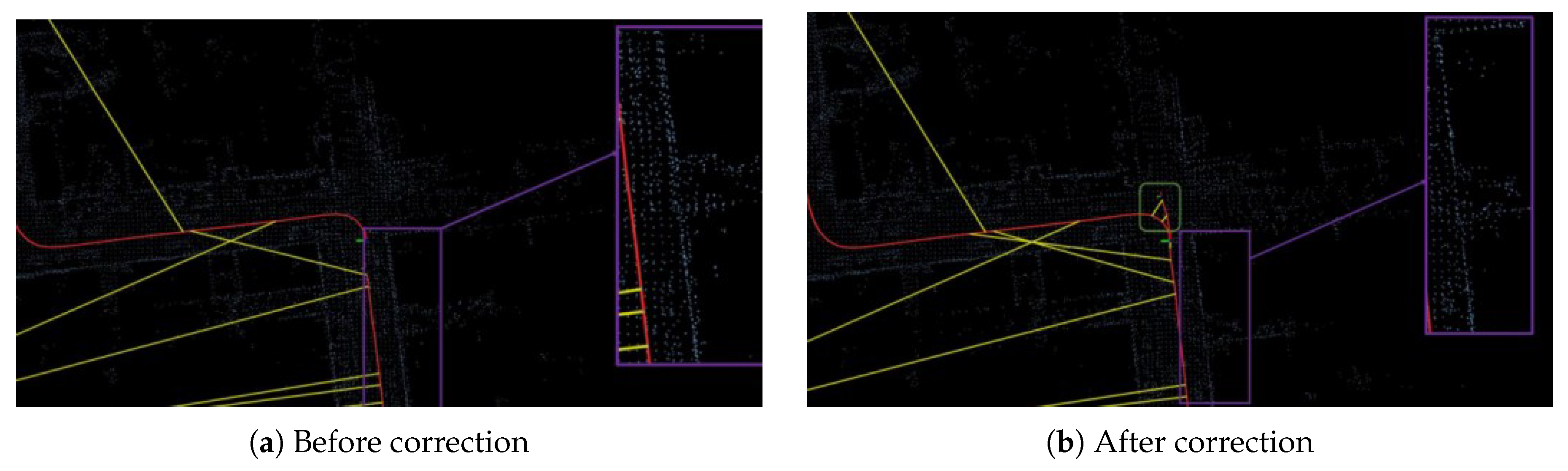

Figure 4 compares maps of the KITTI07 sequence before and after correction, revealing obvious ghosting (e.g., blurred building boundaries) in the uncorrected map versus clear boundaries post-correction, verifying the algorithm’s effectiveness in enhancing map consistency.

4.3. Results on the NCLT Dataset

The NCLT dataset includes diverse indoor–outdoor mixed environments (e.g., campus corridors, outdoor lawns) and significant seasonal variations, imposing greater challenges on the robustness of loop closure detection algorithms.

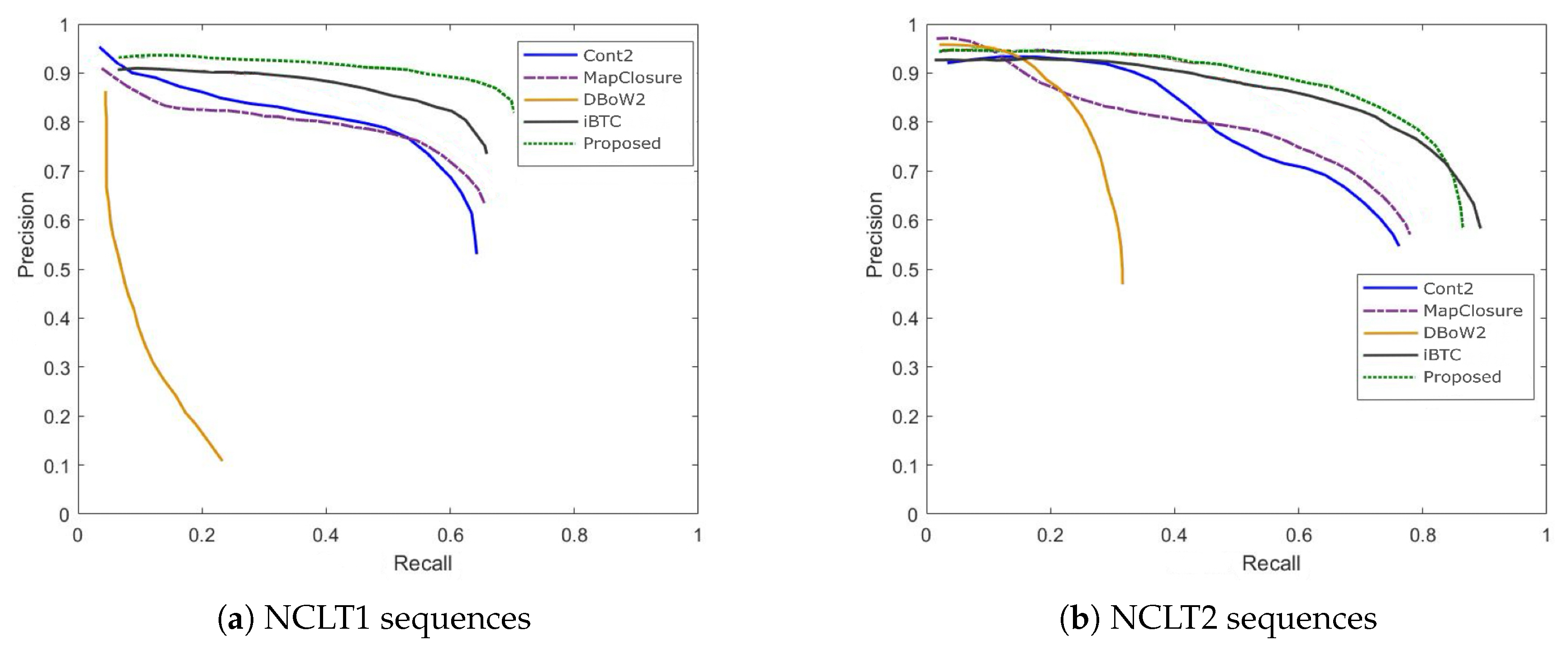

Table 4 compares the F1-scores of different methods on the NCLT1 and NCLT2 sequences, while

Figure 5 shows their corresponding Precision–Recall (PR) curves. As shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 5, the proposed algorithm achieves the highest F1-scores across both sequences, with an average of 77.63%. This represents an improvement of 10.16% over the LiDAR-only Map Closure method and 47.75% over the vision-only DBoW2 approach. Compared with the multimodal iBTC method, the proposed algorithm achieves an additional 3.61% increase in average F1-score.The improvement arises primarily from the use of the enhanced RANSAC-based geometric verification, which increases robustness against noise and environmental changes. For instance, the NCLT2 sequence contains winter snow scenes, where LiDAR point clouds are heavily affected by reflections from snow surfaces. The proposed algorithm leverages visual texture information during verification to suppress false matches and improve detection reliability.Notably, the proposed method achieves an F1-score of 0.7884 on the NCLT2 sequence—significantly outperforming all other methods demonstrating its superior adaptability and robustness in unstructured and dynamic environments.

Table 5 presents the comparison of loop closure detection performance on the NCLT dataset before and after removing the visual modality from the proposed algorithm. As shown, integrating visual information leads to consistent improvements across all four sequences, with an average increase of 42.75 detected loops and an average rise of 0.56% in maximum similarity.These results confirm the algorithm’s enhanced capability for loop recognition in complex environments. For example, in the NCLT1 sequence, where dense tree occlusions cause sparse LiDAR point clouds and incomplete geometric features, the proposed method successfully identifies more loop closures by incorporating visual texture cues. This demonstrates the effectiveness of LiDAR–vision fusion in improving detection completeness and robustness under challenging outdoor conditions.

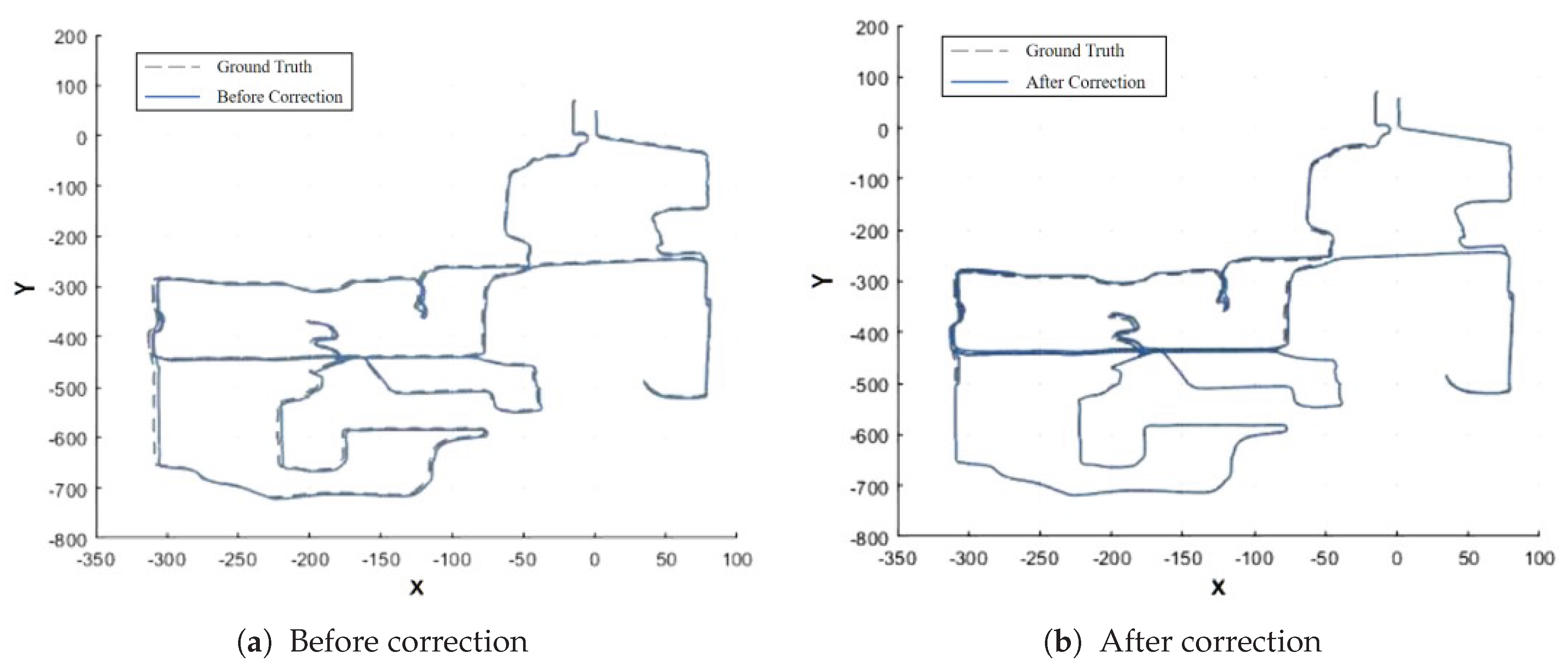

Table 6 compares the ATE before and after loop closure correction on the NCLT4 sequence, and

Figure 6 illustrates the corresponding trajectory comparison.The NCLT4 sequence includes long indoor corridors (textureless regions) as well as open outdoor areas, posing significant challenges for loop closure detection. By leveraging LiDAR–vision fusion, the proposed algorithm effectively addresses both the lack of LiDAR features in indoor textureless regions and the visual matching errors caused by strong illumination in outdoor scenes.After applying loop closure correction, the trajectory deviation in the indoor corridor section is reduced from approximately 1.2 m before correction to 0.8 m after correction, indicating that the proposed method significantly improves pose accuracy and consistency in mixed indoor–outdoor environments.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposes a radar-visual depth fusion algorithm for loop closure detection in SLAM systems, addressing limitations of single-modality methods and flaws in existing fusion approaches. It achieves effective "geometry-texture" information association through spatiotemporal alignment, depth completion, hybrid feature fusion, and improved RANSAC verification. Limitations remain in dynamic environment robustness, depth fusion mechanisms, real-time performance, and embedded adaptation, which require further improvements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and M.L.; methodology, B.L.; software, R.C. and Y.Z.; validation, B.L. and M.L.; formal analysis, B.L. and P.W.; investigation, B.L. and R.C.; resources, B.L.; data curation, R.C. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, B.L., Y.Z. and M.L. ;visualization, R.C. and M.L.; supervision, B.L. and P.W.; project administration, B.L. and P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A Robust and Versatile Monocular Visual-Inertial State Estimator. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Gong, C.; Zhao, S. Multi-Sensor Information Fusion with Multi-Scale Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks for Abnormal Vibration Diagnosis of Rolling Mill. Machines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Long, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, B.; Qiu, T.Z. Semantic Constellation Place Recognition Algorithm Based on Scene Text. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2025, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, A. Scan Context: Egocentric Spatial Descriptor for Place Recognition Within 3D Point Cloud Map. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2018; pp. 4802–4809. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Choi, S.; Kim, A. Scan Context++: Structural Place Recognition Robust to Rotation and Lateral Variations in Urban Environments. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2022, 38, 1856–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Shen, S. Contour Context: Abstract Structural Distribution for 3D LiDAR Loop Detection and Metric Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023; pp. 8386–8392. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, F. BoW3D: Bag of Words for Real-Time Loop Closing in 3D LiDAR SLAM. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 8, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-López, D.; Tardos, J.D. Bags of Binary Words for Fast Place Recognition in Image Sequences. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2012, 28, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Tao, S.; Liu, X.; Babiarz, A.; Yu, F.R. CD-SLAM: A Real-Time Stereo Visual–Inertial SLAM for Complex Dynamic Environments With Semantic and Geometric Information. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Amini, A.; Yang, X.; Mao, H.; Rus, D.L.; Han, S. BEVFusion: Multi-Task Multi-Sensor Fusion with Unified Bird’s-Eye View Representation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023; pp. 2774–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, W.; Cui, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R. CORAL: Colored structural representation for bi-modal place recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2021; pp. 2084–2091. [Google Scholar]

- Vora, S.; Lang, A.H.; Helou, B.; Beijbom, O. PointPainting: Sequential Fusion for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020; pp. 4603–4611. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, X.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Tao, W. LIF-Seg: LiDAR and Camera Image Fusion for 3D LiDAR Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024, 26, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fu, H.; Tai, C.L. TransFusion: Robust LiDAR-Camera Fusion for 3D Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; He, Z.; Yang, Y.; Nie, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, M. MSF-SLAM: Multi-Sensor-Fusion-Based Simultaneous Localization and Mapping for Complex Dynamic Environments. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 19699–19713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wen, C.; Manoj Prakhya, S.; Yin, H.; Zhou, R.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Bai, H.; Wang, Y. Multimodal Features and Accurate Place Recognition With Robust Optimization for Lidar–Visual–Inertial SLAM. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besl, P.; McKay, N.D. A method for registration of 3-D shapes. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1992, 14, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, P.; Strasser, W. The normal distributions transform: a new approach to laser scan matching. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2003) (Cat. No.03CH37453), Vol. 3; 2003; pp. 2743–2748. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Zhu, F. LinK3D: Linear Keypoints Representation for 3D LiDAR Point Cloud. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 2128–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Guadagnino, T.; Mersch, B.; Vizzo, I.; Stachniss, C. Effectively Detecting Loop Closures using Point Cloud Density Maps. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2024; pp. 10260–10266. [Google Scholar]

- Pirotti, F.; Ravanelli, R.; Fissore, F.; Masiero, A. Implementation and assessment of two density-based outlier detection methods over large spatial point clouds. Open Geospatial Data, Software and Standards 2018, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. SURF: Speeded Up Robust Features. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2006; Leonardis, A.; Bischof, H.; Pinz, A., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg; 2006; pp. 404–417. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), Vol. 1; 2005; pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Guo, L.; Jin, L.; Huang, Q. A novel feature extraction method using Pyramid Histogram of Orientation Gradients for smile recognition. In Proceedings of the 2009 16th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2009; pp. 3305–3308. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, M.; Newman, P. Appearance-only SLAM at large scale with FAB-MAP 2.0. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2011, 30, 1100–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Zheng, C.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, S.; Xue, K.; Zhang, F. iBTC: An Image-Assisting Binary and Triangle Combined Descriptor for Place Recognition by Fusing LiDAR and Camera Measurements. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 9, 10858–10865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, J.; Wysoczańska, M.; Trzcinski, T. MinkLoc++: Lidar and Monocular Image Fusion for Place Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN); 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Miao, Z.; Liu, T.; Zhan, X.; Hao, D.; Ma, C. LIFT: Learning 4D LiDAR Image Fusion Transformer for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 17151–17160. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.G.; Stephens, M.J. A Combined Corner and Edge Detector. In Proceedings of the Alvey Vision Conference; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: a paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The KITTI dataset. Int. J. Rob. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlevaris-Bianco, N.; Ushani, A.K.; Eustice, R.M. University of Michigan North Campus long-term vision and lidar dataset. International Journal of Robotics Research 2015, 35, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).