Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- –

- We propose a novel deep learning architecture that integrates Transformer-based temporal modeling with Gaussian mixture connectivity to learn spatiotemporal EEG representations without handcrafted features.

- –

- We introduce an -Rényi mutual-information regularizer that enforces representation diversity across attention and connectivity components, reducing redundancy and supporting interpretability.

- –

- We develop a multi-level interpretability scheme combining attention-based channel relevance, Gaussian kernel class activation maps, and structured ablation analysis to reveal neurophysiological patterns associated with ADHD.

- –

- We conduct extensive experiments using subject-group cross-validation and comparative baselines, demonstrating competitive performance and strong interpretability on a pediatric EEG ADHD dataset.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kernel Methods and Functional Mapping

2.2. Matrix-Based -Rényi Entropy and Mutual Information

- –

- Nonparametric: no assumptions on the underlying EEG distribution.

- –

- Differentiable: allows end-to-end learning with backpropagation.

- –

- Redundancy control: high MI between kernel-induced representations is penalized, encouraging disentangled connectivity patterns across spatial scales.

2.3. Multi-Scale Gaussian Kernel Connectivity

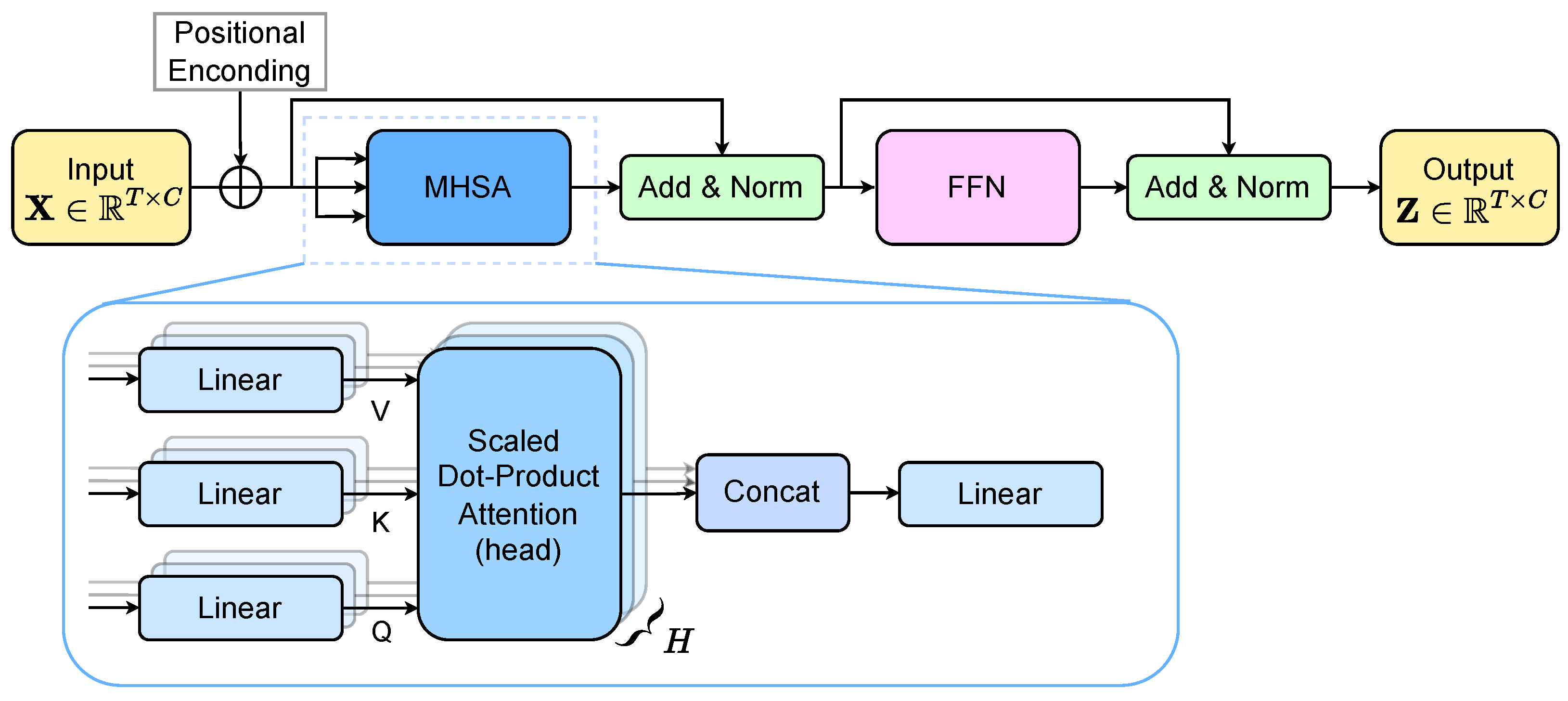

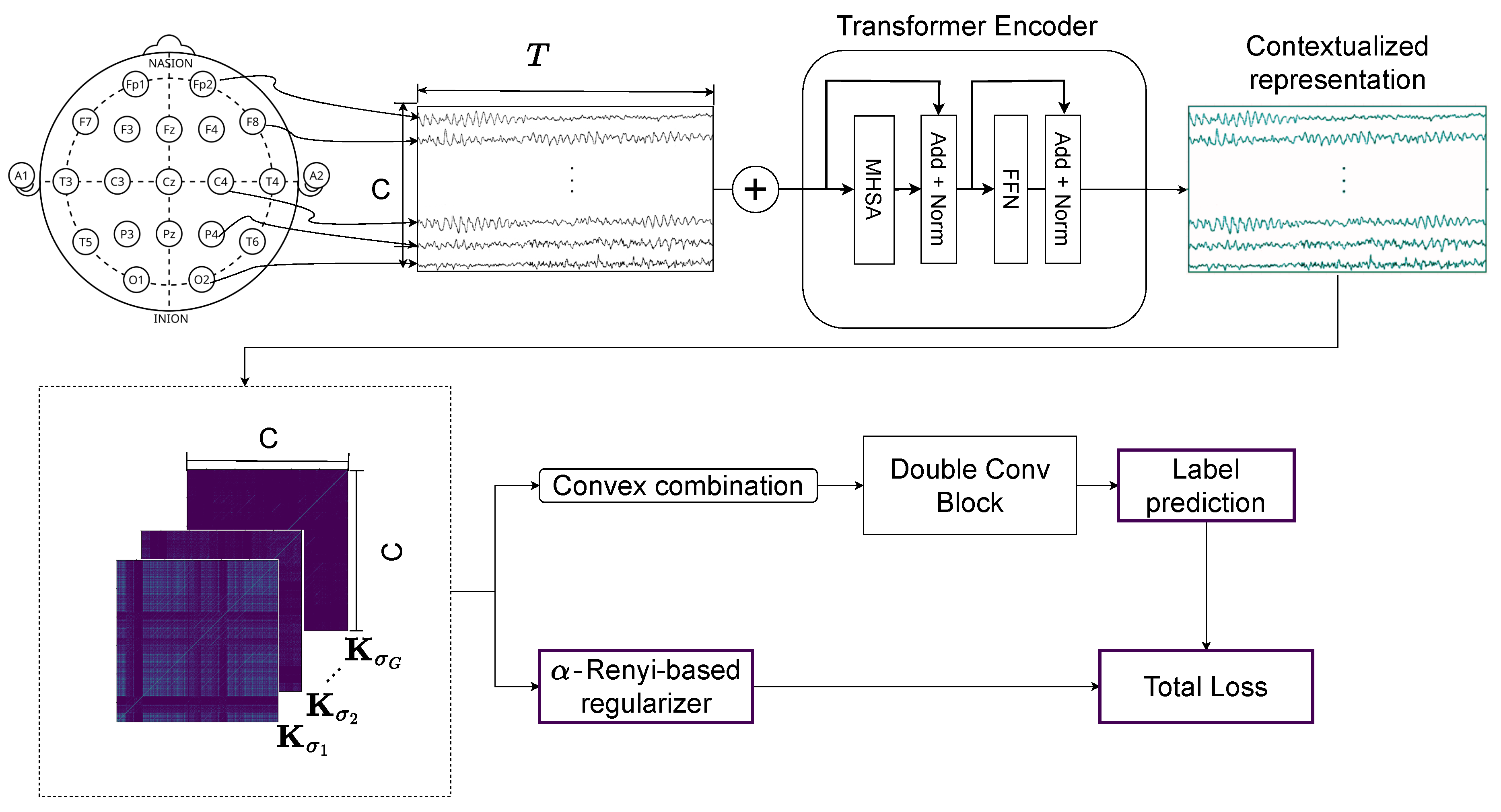

2.4. Transformer and Multi-Kernel Gaussian Connectivity Network with -Rényi Regularization

3. Experimental Set-Up

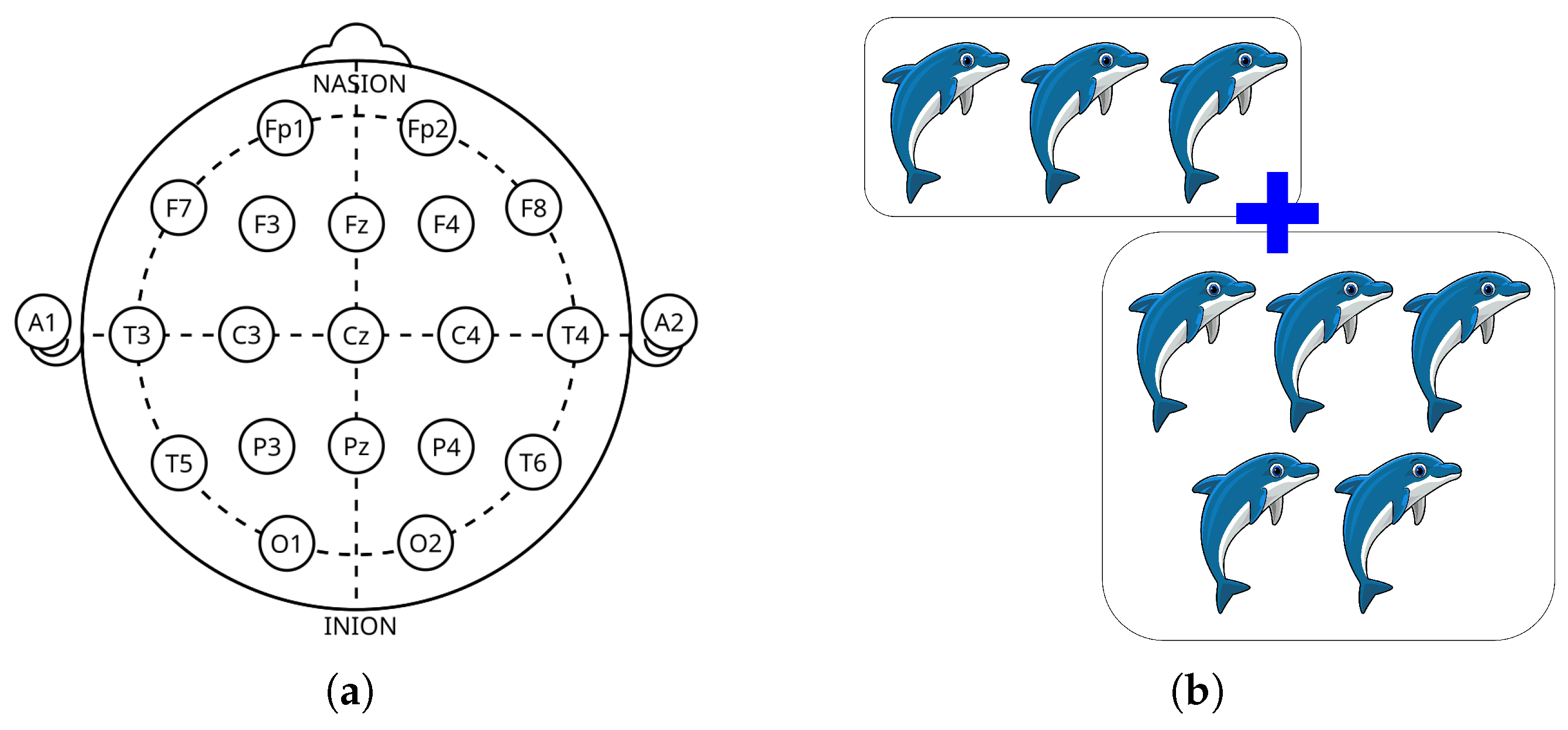

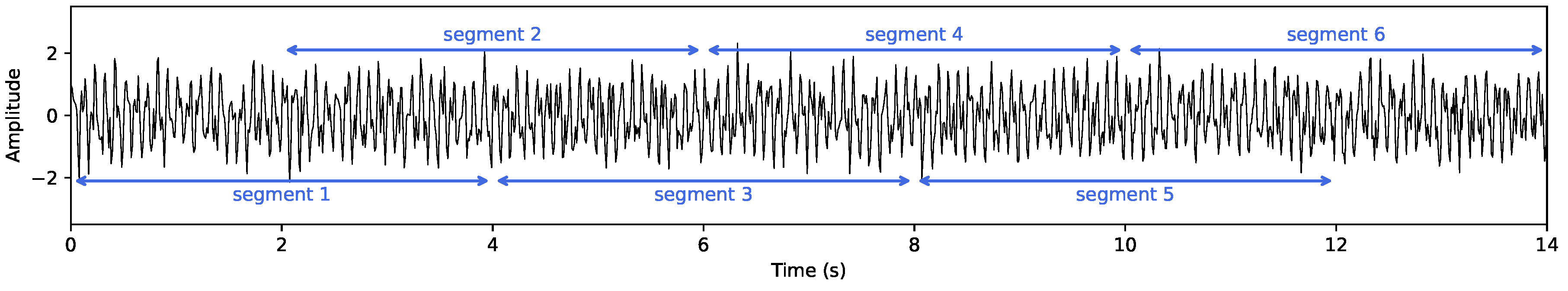

3.1. Tested ADHD Dataset

3.2. Assessment, Model Comparison, and Training Details

- –

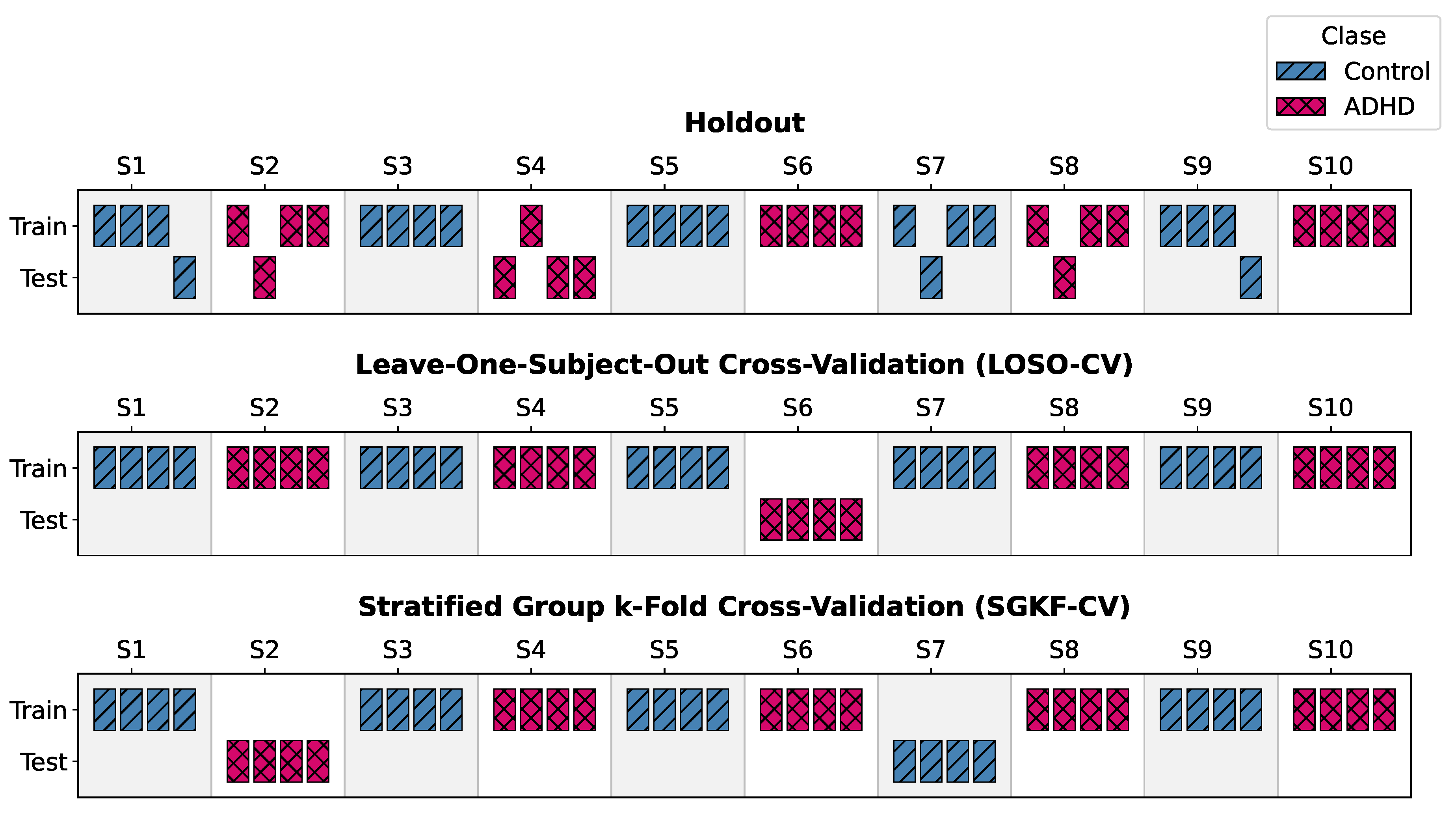

- Leave-One-Subject-Out Cross-Validation (LOSO-CV). At each iteration, data from a single subject were held out exclusively for testing, while the remaining subjects formed the training set. This is repeated N times so that each participant serves as the test set once.

- –

- Stratified Group k-Fold Cross-Validation (SGKF-CV). A subject-wise stratified k-fold scheme () was employed. For each fold, 24 subjects (12 ADHD, 12 controls) were reserved for testing, and the remaining 96 subjects formed the training set. Stratification maintained class balance across folds.

- –

- CNN-based Architectures (ShallowConvNet [32], EEGNet [29]): These models represent compact, efficient, and widely adopted CNNs designed specifically for end-to-end EEG processing. They serve as a baseline to evaluate the performance of standard deep learning approaches that do not explicitly model connectivity or long-range temporal dependencies with attention.

- –

- Hybrid Architecture (CNN-LSTM [33]): This model combines CNNs with recurrent neural networks (LSTMs). It provides a point of comparison for evaluating T-GARNet’s Transformer-based approach against more traditional methods for modeling temporal sequences.

- –

- Attention-based Architecture (Multi-Stream Transformer [19]): This model also uses Transformers, but processes spectral, spatial, and temporal streams independently. It serves as a critical baseline to evaluate the benefits of T-GARNet’s integrated architecture, where temporal attention and spatial connectivity modeling are directly linked.

- –

- Classical Machine Learning Pipeline (ANOVA-PCA SVM [38]): This model represents a traditional, non-end-to-end approach involving explicit feature engineering, selection, and classification. It provides a baseline to quantify the performance gains achieved by deep learning methodologies.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Performance Under the LOSO–CV Protocol

4.2. Performance Under the SGKF–CV Protocol

4.3. Statistical Significance Analysis

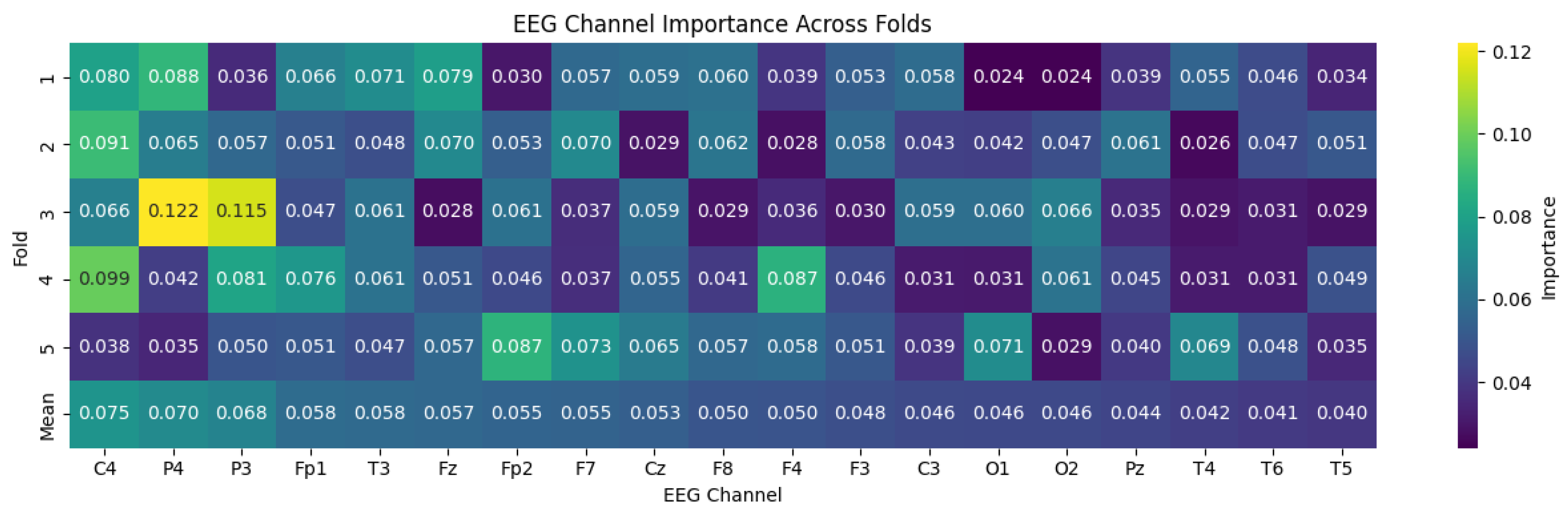

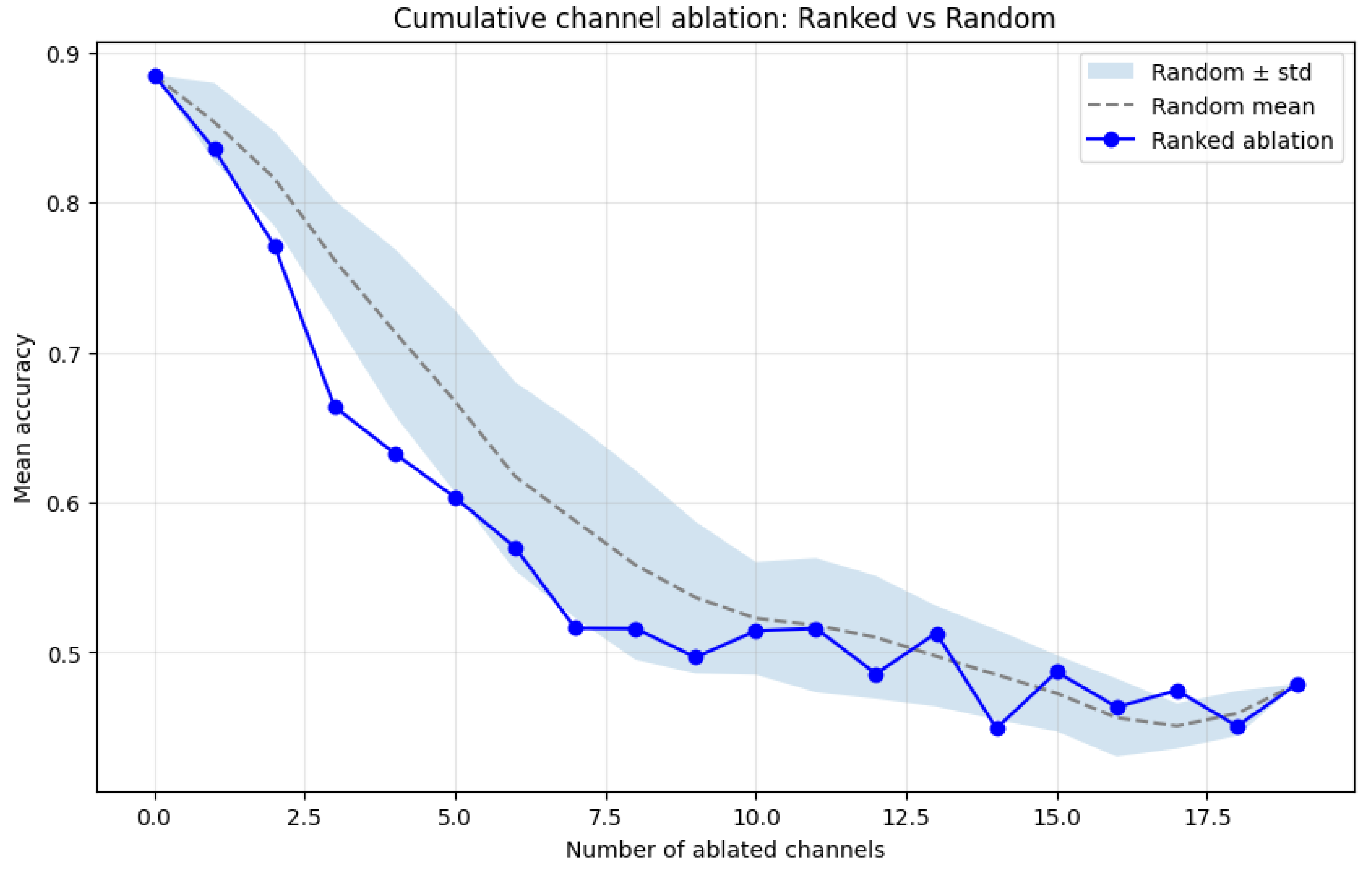

4.4. Transformer-Based Channel Importance Analysis

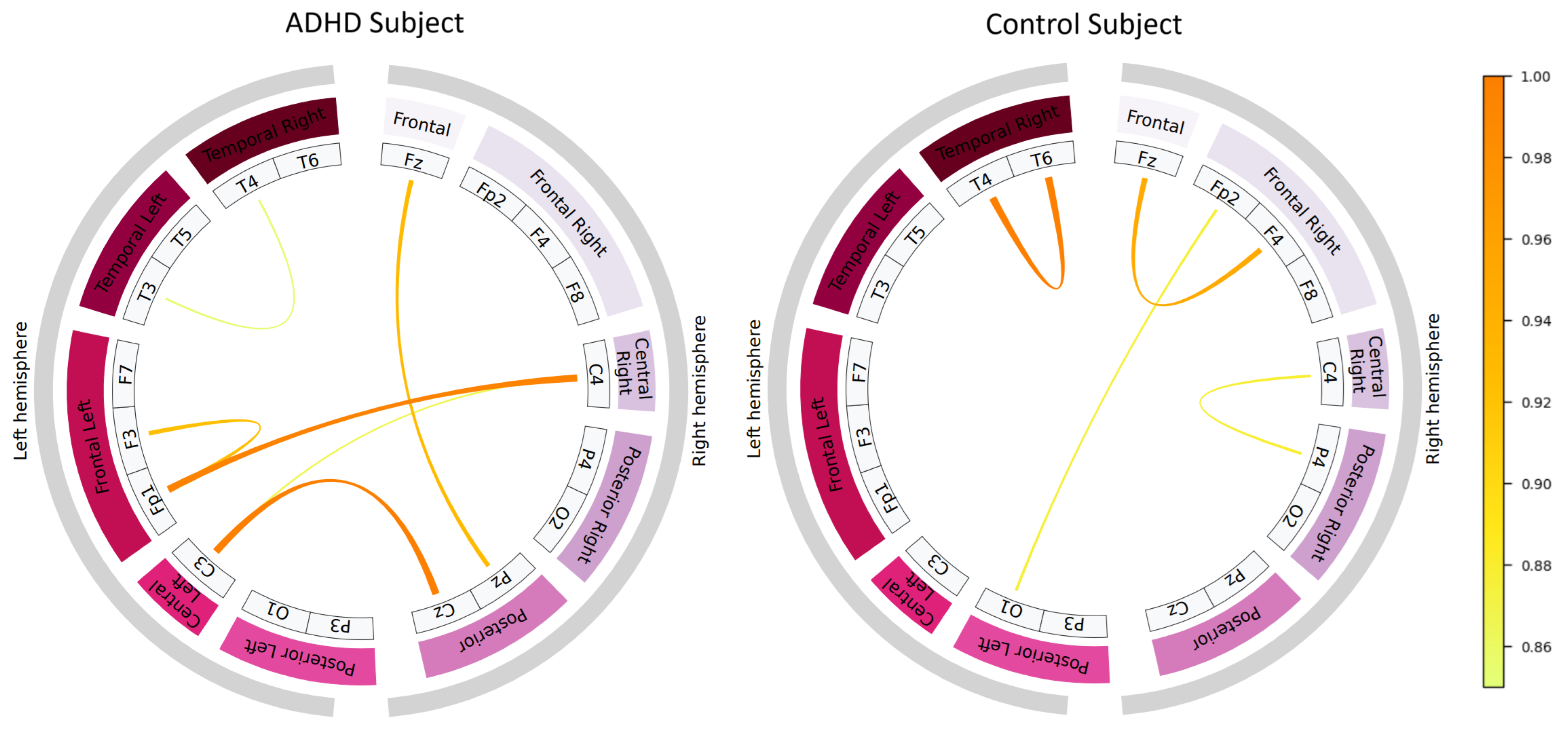

4.5. Learned Connectivity Patterns

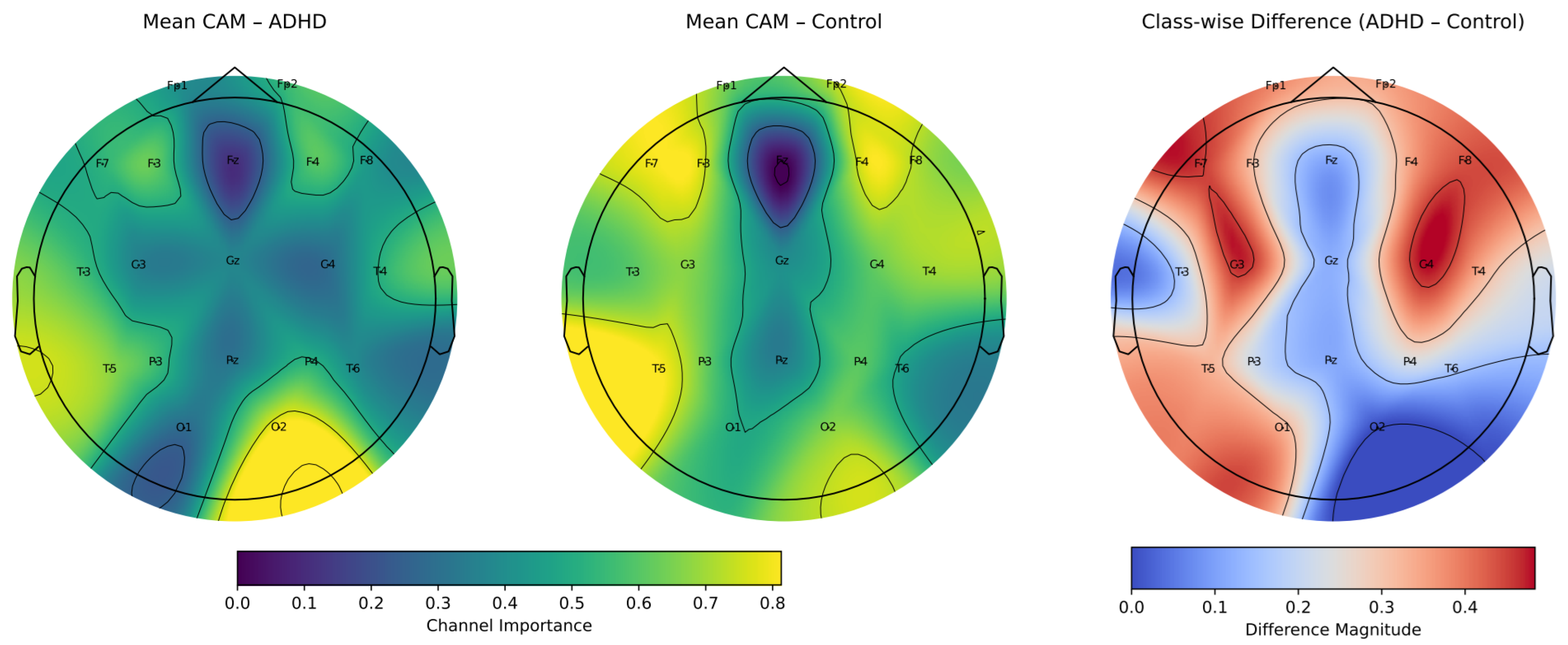

4.6. Class–Wise Spatial Relevance via Grad-CAM++

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Asherson, P. ADHD across the lifespan. Medicine 2024, 52, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, G.; Demelash, S.; Gizachew, Y.; Tsegay, L.; Alati, R. The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Journal of affective disorders 2023, 339, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Poppi, C.; Arcolin, E.; Cutino, A.; Ferri, P.; D’Amico, R.; Filippini, T. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: A systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 2021, 33, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Plas, N.E.; Noordermeer, S.D.; Oosterlaan, J.; Luman, M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Predictors of Adult Psychiatric Outcomes of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hurjui, I.A.; Hurjui, R.M.; Hurjui, L.L.; Serban, I.L.; Dobrin, I.; Apostu, M.; Dobrin, R.P. Biomarkers and Neuropsychological Tools in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: From Subjectivity to Precision Diagnosis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, A.; Altınkaynak, M.; Dolu, N.; İzzetoğlu, M.; Pektaş, F.; Özmen, S.; Demirci, E.; Batbat, T. Combining functional near-infrared spectroscopy and EEG measurements for the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neural Computing and Applications 2020, 32, 8367–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.Q.; Vera, V.D.G.; Quintero, M.J.R. Diagnosis of ADHD in children with EEG and machine learning: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical and Health 2025, 36, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. Artificial intelligence in ADHD assessment: a comprehensive review of research progress from early screening to precise differential diagnosis. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2025, 8, 1624485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Y.; Li, X. A deep learning framework for identifying children with ADHD using an EEG-based brain network. Neurocomputing 2019, 356, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, A.; He, Y.; Contreras-Vidal, J.L. Deep learning for electroencephalogram (EEG) classification tasks: a review. Journal of neural engineering 2019, 16, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, A.B.; Flaherty, B.P. A framework for characterizing heterogeneity in neurodevelopmental data using latent profile analysis in a sample of children with ADHD. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders 2022, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadithy, S.S.; Abdalkafor, A.S.; Al-Khateeb, B. Emotion recognition in EEG Signals: Deep and machine learning approaches, challenges, and future directions. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2025, 196, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Y. DMMR: Cross-subject domain generalization for EEG-based emotion recognition via denoising mixed mutual reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 628–636.

- Loh, H.W.; Ooi, C.P.; Oh, S.L.; Barua, P.D.; Tan, Y.R.; Acharya, U.R.; Fung, D.S.S. ADHD/CD-NET: automated EEG-based characterization of ADHD and CD using explainable deep neural network technique. Cognitive Neurodynamics 2024, 18, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. An end-to-end deep learning model for EEG-based major depressive disorder classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41337–41347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, S.K.; Acharya, U.R. An explainable and interpretable model for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children using EEG signals. Computers in biology and medicine 2023, 155, 106676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtyari, M.; Mirzaei, S. ADHD detection using dynamic connectivity patterns of EEG data and ConvLSTM with attention framework. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 76, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarion, G.; Sparacino, L.; Antonacci, Y.; Faes, L.; Mesin, L. Connectivity analysis in EEG data: a tutorial review of the state of the art and emerging trends. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, A.; Imtiaz, M.H. Automatic identification of children with ADHD from EEG brain waves. Signals 2023, 4, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookshire, G.; Kasper, J.; Blauch, N.M.; Wu, Y.C.; Glatt, R.; Merrill, D.A.; Gerrol, S.; Yoder, K.J.; Quirk, C.; Lucero, C. Data leakage in deep learning studies of translational EEG. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1373515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Singh, B.K. Classification of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder using Wigner-Ville time-frequency and deep expEEGNetwork feature-based computational models. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and BCI 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; Covino, A.; Cristaldi, L.; Frosolone, M. A systematic review on feature extraction in electroencephalography-based diagnostics and therapy in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sensors 2022, 22, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, T.; Sujatha, S. Common Spatial Pattern based Feature Extractor with Hybrid LinkNet-SqueezeNet for ADHD Detection from EEG Signal. Progress in Engineering Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TaghiBeyglou, B.; Hasanzadeh, N. ADHD diagnosis in children using common spatial pattern and nonlinear analysis of filter banked EEG. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE). IEEE; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- González, C.; Ortiz, E.; Escobar, J. , Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder classification with EEG and machine learning. In Neuroimaging Techniques; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 479–498.

- Bathula, D.R.; Benet Nirmala Bathula, A. Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging. In Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging; Springer, 2024; pp. 1–22.

- Moghaddari, M.; Lighvan, M.Z.; Danishvar, S. Diagnose ADHD disorder in children using convolutional neural network based on continuous mental task EEG. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 197, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tong, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R. SCANet: An Innovative Multiscale Selective Channel Attention Network for EEG-Based ADHD Recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of neural engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chu, Y.; Li, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X. AMEEGNet: attention-based multiscale EEGNet for effective motor imagery EEG decoding. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2025, 19, 1540033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Ushiba, J. Deep residual convolutional neural networks for brain–computer interface to visualize neural processing of hand movements in the human brain. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2022, 16, 882290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Human brain mapping 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Jing, X.; Yokoi, H.; Huang, W.; Zhu, M.; Chen, S.; Li, G. Towards high-accuracy classifying attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders using CNN-LSTM model. Journal of Neural Engineering 2022, 19, 046015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Jia, S.; Lun, X.; Hao, Z.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, R.; Lv, J. GCNs-net: a graph convolutional neural network approach for decoding time-resolved eeg motor imagery signals. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 35, 7312–7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushiyant.; Mathur, V.; Kumar, S.; Shokeen, V. REEGNet: A resource efficient EEGNet for EEG trail classification in healthcare. Intelligent Decision Technologies 2024, 18, 1463–1476. [CrossRef]

- Sujatha Ravindran, A.; Contreras-Vidal, J. An empirical comparison of deep learning explainability approaches for EEG using simulated ground truth. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 17709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Ling, S.S.H.; Wong, J.K.W. Exploring the frontier: Transformer-based models in EEG signal analysis for brain-computer interfaces. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 178, 108705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvigne, V.; Wannous, H.; Vandeborre, J.P.; Ris, L.; Dutoit, T. Spatio-temporal analysis of transformer based architecture for attention estimation from eeg. In Proceedings of the 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). IEEE; 2022; pp. 1076–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Vafaei, E.; Hosseini, M. Transformers in EEG Analysis: A review of architectures and applications in motor imagery, seizure, and emotion classification. Sensors 2025, 25, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudler-Flam, J. Rényi mutual information in quantum field theory. Physical Review Letters 2023, 130, 021603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Murillo, D.G.; Álvarez-Meza, A.M.; Castellanos-Dominguez, C.G. Kcs-fcnet: Kernel cross-spectral functional connectivity network for eeg-based motor imagery classification. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Giraldo, L.G.S.; Jenssen, R.; Principe, J.C. Multivariate Extension of Matrix-Based Rényi’s α-Order Entropy Functional. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2019, 42, 2960–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guella, J.C. On Gaussian kernels on Hilbert spaces and kernels on hyperbolic spaces. Journal of Approximation Theory 2022, 279, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Llamas, L.R.; Guardado-Medina, R.O.; Garcia, A.; Mendez-Vazquez, A. Kernel Learning by Spectral Representation and Gaussian Mixtures. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, J.C. Information Theoretic Learning: Renyi’s Entropy and Kernel Methods. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2010, 27, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, L.; Principe, J.C. A Matrix-Based Framework for Rényi’s Entropy and Mutual Information Using Operators. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2015, 63, 3551–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kschischang, F.R. The wiener-khinchin theorem. The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Toronto 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.P. Probabilistic machine learning: an introduction; MIT press, 2022.

- Nasrabadi, A.M. EEG Data for ADHD/Control Children. https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/eeg-data-adhd-control-children, 2020. Consultado: 2022-11-18.

- Zimmerman, D.W.; Zumbo, B.D. Relative power of the Wilcoxon test, the Friedman test, and repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks. The Journal of Experimental Education 1993, 62, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhage, N.; Nanda, N.; Olsson, C.; Henighan, T.; Joseph, N.; Mann, B.; Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Conerly, N.; et al. A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits. Technical report, Anthropic, 2021. Transformer Circuits Thread.

- Cao, M.; Martin, E.; Li, X. Machine learning in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: new approaches toward understanding the neural mechanisms. Translational Psychiatry 2023, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.N.; Khan, N. Enhanced cross-dataset electroencephalogram-based emotion recognition using unsupervised domain adaptation. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2025, 184, 109394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source | IEEE DataPort [50] |

|---|---|

| Total Subjects | 121 children (61 ADHD, 60 control) |

| Age Range | 7–12 years |

| ADHD Group | 48 boys, 12 girls; mean age = 9.62 ± 1.75 years |

| Control Group | 50 boys, 10 girls; mean age = 9.85 ± 1.77 years |

| Diagnosis | DSM-IV, maximum 6 months of Ritalin use |

| EEG Channels | 19 (10–20 system): Fz, Cz, Pz, C3, T3, C4, T4, Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8, P3, P4, T5, T6, O1, O2 |

| Reference Electrodes | A1 and A2 (earlobes) |

| Sampling Rate | 128 Hz |

| Task Protocol | Cartoon-based visual attention task; 5–16 characters per image; continuous presentation based on response speed |

| Model | Trainable Params. | CNN | LSTM/RNN | Attention | Connectivity | Raw Data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShallowConvNet [32] | 33762 | yes | no | no | no | yes | Shallow convolutional architecture with squaring and log activations to approximate power features. |

| EEGNet [29] | 1666 | yes | no | no | no | yes | Compact architecture using depthwise and separable convolutions optimized for EEG decoding. |

| CNN-LSTM [33] | 8752 | yes | yes | no | no | yes | Convolutional feature extractor followed by recurrent layers for temporal modeling. |

| ANOVA-PCA SVM [19] | N/A | no | no | no | no | no | Handcrafted feature extraction and statistical dimensionality reduction with SVM classifier. |

| Multi-Stream Transformer [38] | 574082 | no | no | yes | no | no | Transformer encoders applied independently to spectral, spatial, and temporal inputs. |

| T-GARNet (this work) | 6942 | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | Transformer temporal modeling, Gaussian kernel connectivity, and Rényi entropy regularization. |

| Model | ACC (%) |

|---|---|

| EEGNet | |

| CNN–LSTM | |

| ShallowConvNet | |

| Multi–Stream Transformer | |

| ANOVA–PCA SVM | |

| T-GARNet (This work) |

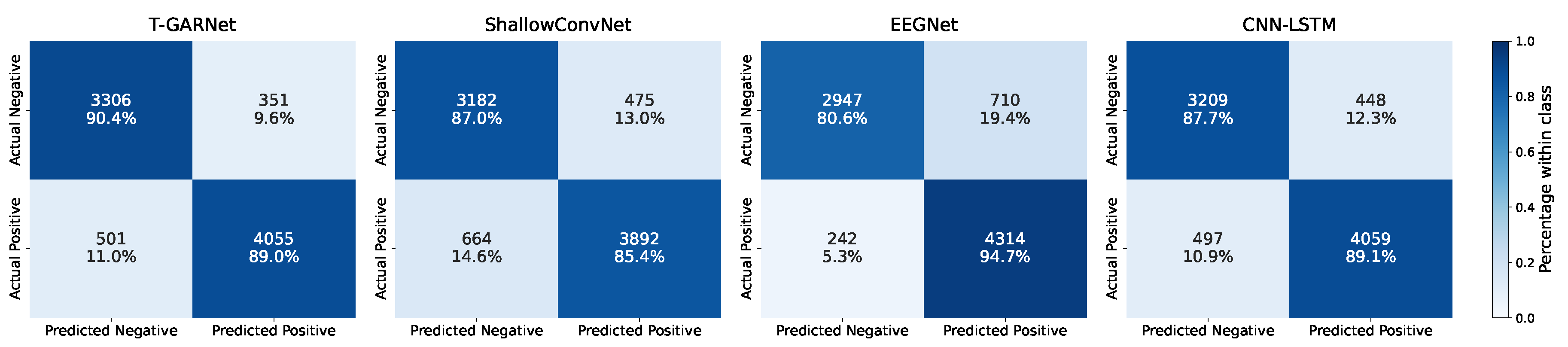

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Recall (%) | Precision (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ShallowConvNet | 84.67 ± 0.66 | 84.90 ± 0.53 | 86.15 ± 0.63 |

| EEGNet | 87.88 ± 1.26 | 87.12 ± 1.19 | 88.45 ± 1.53 |

| CNN-LSTM | 86.31 ± 2.12 | 86.01 ± 2.22 | 86.59 ± 2.07 |

| Multi-Stream Transformer | 74.05 ± 0.57 | 72.76 ± 0.69 | 74.68 ± 0.52 |

| ANOVA-PCA SVM | 66.47 ± 0.00 | 65.82 ± 0.00 | 66.59 ± 0.00 |

| T-GARNet (This work) | 88.32± 0.92 | 88.02± 0.97 | 88.65± 0.98 |

| Model | Avg. Rank | Wins (out of 50) | Significant vs T-GARNet |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-GARNet (proposed) | 2.28 | 19 | — |

| EEGNet | 2.36 | 9 | No |

| CNN-LSTM | 2.41 | 18 | No |

| ShallowConvNet | 3.12 | 4 | No |

| Multi-Stream Transformer | 5.24 | 0 | Yes |

| ANOVA-PCA SVM | 5.59 | 0 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).