Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Myocardial Infarction Induced by Terminal Ischemia or Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury does not Cause Osteopenia in Mice or Rats

2.2. Pressure Overload-Induced Heart Failure Reduces Cortical Bone Mineral Density

2.3. TAC-Induced Bone Loss is Likely not Caused by Hypoperfusion

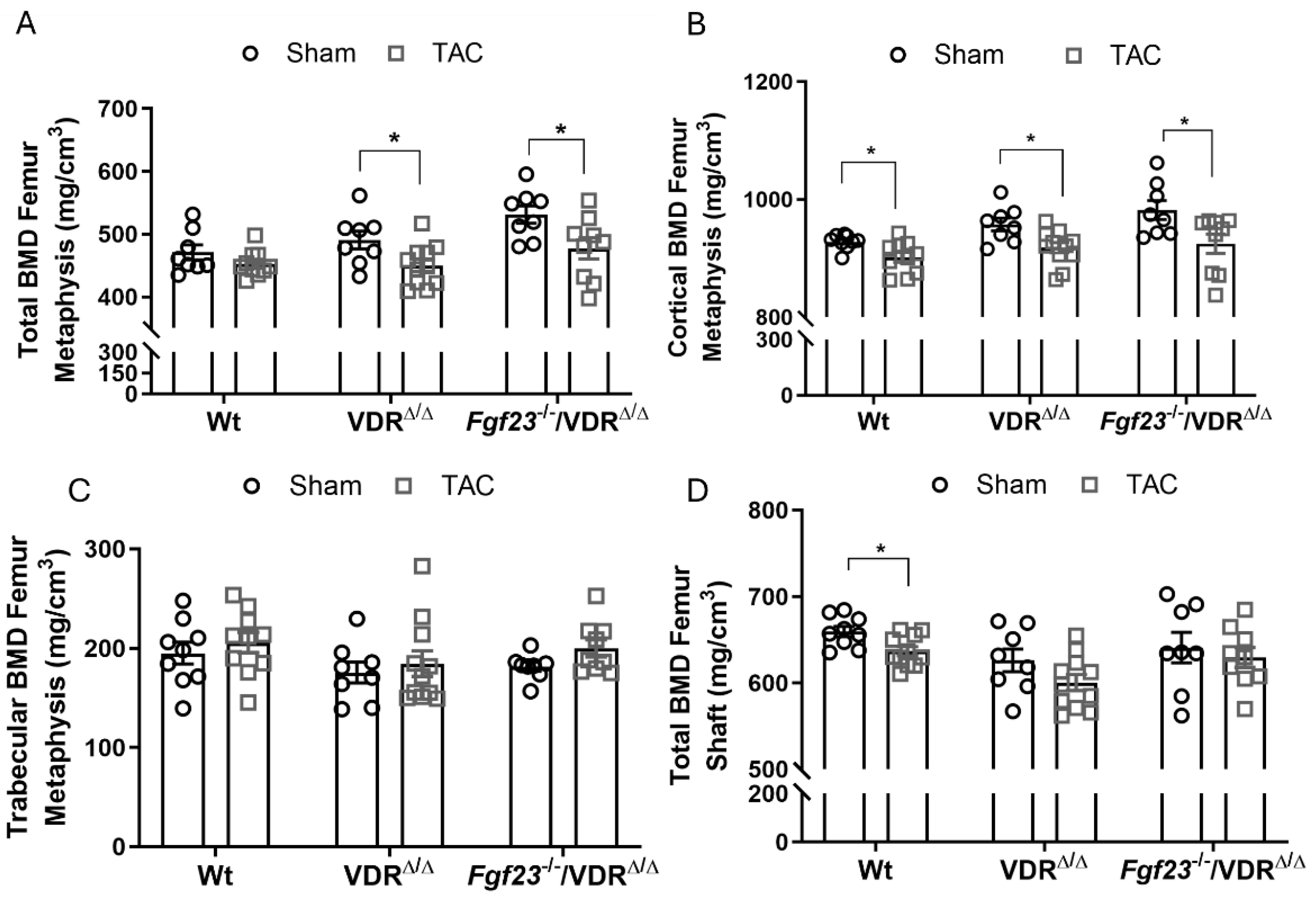

2.4. FGF23 Lacks Essential role in TAC–Induced Osteopenia

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

4.2. Animals

4.3. Myocardial Infarction in Mice

4.4. Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats

4.5. Transverse Aortic Constriction

4.6. Transthoracic Doppler Echocardiography

4.7. Serum and Urine Biochemistry

4.8. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT)

4.9. Micro Computed Tomography (µCT)

4.10. Bone Histology and Histomorphometry

4.11. RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

4.12. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Roger, V.L. Myocardial infarction outcomes: “the times, they are a-changin...”. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010, 3, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostis, W.J.; Deng, Y.; Pantazopoulos, J.S.; Moreyra, A.E.; Kostis, J.B.; Myocardial Infarction Data Acquisition System Study, G. Trends in mortality of acute myocardial infarction after discharge from the hospital. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010, 3, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Buzkova, P.; Fink, H.A.; Lee, J.S.; Chen, Z.; Ahmed, A.; Parashar, S.; Robbins, J.R. Hip fractures and heart failure: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Eur Heart J 2010, 31, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrovitis, J.; Zotos, P.; Kaldara, E.; Diakos, N.; Tseliou, E.; Vakrou, S.; Kapelios, C.; Chalazonitis, A.; Nanas, S.; Toumanidis, S.; et al. Bone mass loss in chronic heart failure is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism and has prognostic significance. Eur J Heart Fail 2012, 14, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diepen, S.; Majumdar, S.R.; Bakal, J.A.; McAlister, F.A.; Ezekowitz, J.A. Heart failure is a risk factor for orthopedic fracture: a population-based analysis of 16,294 patients. Circulation 2008, 118, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, Y.; Melton, L.J., 3rd; Weston, S.A.; Roger, V.L. Association between myocardial infarction and fractures: an emerging phenomenon. Circulation 2011, 124, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, K.; Smolen, J.S. Inflammatory bone loss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Han, L.; Ambrogini, E.; Weinstein, R.S.; Manolagas, S.C. Glucocorticoids and tumor necrosis factor alpha increase oxidative stress and suppress Wnt protein signaling in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 44326–44335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavic, S.; Ford, K.; Modert, M.; Becirovic, A.; Handschuh, S.; Baierl, A.; Katica, N.; Zeitz, U.; Erben, R.G.; Andrukhova, O. Genetic Ablation of Fgf23 or Klotho Does not Modulate Experimental Heart Hypertrophy Induced by Pressure Overload. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 11298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrukhova, O.; Slavic, S.; Odorfer, K.I.; Erben, R.G. Experimental Myocardial Infarction Upregulates Circulating Fibroblast Growth Factor-23. J Bone Miner Res 2015, 30, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latic, N.; Erben, R.G. FGF23 and Vitamin D Metabolism. JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.K.; Roschger, P.; Zeitz, U.; Klaushofer, K.; Andrukhova, O.; Erben, R.G. FGF23 Regulates Bone Mineralization in a 1,25(OH)2 D3 and Klotho-Independent Manner. J Bone Miner Res 2016, 31, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjandra, P.M.; Paralkar, M.P.; Osipov, B.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhao, F.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Christiansen, B.A. Systemic bone loss following myocardial infarction in mice. J Orthop Res 2021, 39, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, H.; Uzuka, H.; Nishimiya, K.; Shimokawa, H. Treadmill exercise prevents reduction of bone mineral density after myocardial infarction in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020, 27, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Z.; Yuan, W.; Jia, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Fan, D.; Leng, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Bone mass loss in chronic heart failure is associated with sympathetic nerve activation. Bone 2023, 166, 116596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streicher, C.; Zeitz, U.; Andrukhova, O.; Rupprecht, A.; Pohl, E.; Larsson, T.E.; Windisch, W.; Lanske, B.; Erben, R.G. Long-term Fgf23 deficiency does not influence aging, glucose homeostasis, or fat metabolism in mice with a nonfunctioning vitamin D receptor. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavic, S.; Andrukhova, O.; Ford, K.; Handschuh, S.; Latic, N.; Reichart, U.; Sasgary, S.; Bergow, C.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Kostenuik, P.J.; et al. Selective inhibition of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) in hematopoietic cells improves outcome after experimental myocardial infarction. J Mol Med (Berl) 2018, 96, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehle, C.; Bauersachs, J. Small animal models of heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2019, 115, 1838–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrukhova, O.; Slavic, S.; Smorodchenko, A.; Zeitz, U.; Shalhoub, V.; Lanske, B.; Pohl, E.E.; Erben, R.G. FGF23 regulates renal sodium handling and blood pressure. EMBO Mol Med 2014, 6, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latic, N.; Lari, A.; Sun, N.; Zupcic, A.; Oubounyt, M.; Falivene, J.; Buck, A.; Hofer, M.; Chang, W.; Kuebler, W.M.; et al. Deletion of cardiac fibroblast growth factor-23 beneficially impacts myocardial energy metabolism in left ventricular hypertrophy. NPJ Metab Health Dis 2025, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, B.; Sun, K.; Liu, N.; Tang, B.; Fang, S.; Zhu, L.; Wei, X. HIF-1alpha: Its notable role in the maintenance of oxygen, bone and iron homeostasis (Review). Int J Mol Med 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riehle, C.; Wende, A.R.; Zaha, V.G.; Pires, K.M.; Wayment, B.; Olsen, C.; Bugger, H.; Buchanan, J.; Wang, X.; Moreira, A.B.; et al. PGC-1beta deficiency accelerates the transition to heart failure in pressure overload hypertrophy. Circ Res 2011, 109, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, S.K.; Andrukhova, O.; Clinkenbeard, E.L.; White, K.E.; Erben, R.G. Excessive Osteocytic Fgf23 Secretion Contributes to Pyrophosphate Accumulation and Mineralization Defect in Hyp Mice. PLoS Biol 2016, 14, e1002427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, J.H.; Broussard, D.L. Relationship between bone mineral density and myocardial infarction in US adults. Osteoporos Int 2005, 16, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Bidirectional association between cardiovascular disease and hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2025, 25, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Moncusí, M.; El-Hussein, L.; Delmestri, A.; Cooper, C.; Moayyeri, A.; Libanati, C.; Toth, E.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Khalid, S. Estimating the Incidence and Key Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients at High Risk of Imminent Fracture Using Routinely Collected Real-World Data From the UK. J Bone Miner Res 2022, 37, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, P.; Nordstrom, A.; Jansson, J.H.; Weinehall, L.; Nordstrom, P. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased risk for myocardial infarction in men and women. Osteoporos Int 2012, 23, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjandra, P.M.; Orr, S.V.; Lam, S.K.; Kulkarni, A.D.; Chen, Y.J.; Adhikari, A.; Silverman, J.L.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Christiansen, B.A. Investigating the role of complement 5a in systemic bone loss after myocardial infarction. Bone 2025, 198, 117543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, G.; von Skrbensky, G.; Holzer, L.A.; Pichl, W. Hip fractures and the contribution of cortical versus trabecular bone to femoral neck strength. J Bone Miner Res 2009, 24, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.P.; Jian, X.Y.; Liang, D.L.; Wen, J.X.; Wei, Y.H.; Wu, J.D.; Li, Y.Q. The association between heart failure and risk of fractures: Pool analysis comprising 260,410 participants. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 977082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimai, H.P.; Muschitz, C.; Amrein, K.; Bauer, R.; Cejka, D.; Gasser, R.W.; Gruber, R.; Haschka, J.; Hasenohrl, T.; Kainberger, F.; et al. [Osteoporosis-Definition, risk assessment, diagnosis, prevention and treatment (update 2024) : Guidelines of the Austrian Society for Bone and Mineral Research]. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2024, 136, 599–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drey, M.; Otto, S.; Thomasius, F.; Schmidmaier, R. [Update of the S3-guideline on diagnostics, prophylaxis and treatment of osteoporosis]. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2023, 56, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elefteriou, F.; Ahn, J.D.; Takeda, S.; Starbuck, M.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Kondo, H.; Richards, W.G.; Bannon, T.W.; Noda, M.; et al. Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature 2005, 434, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, S.; Elefteriou, F.; Levasseur, R.; Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Parker, K.L.; Armstrong, D.; Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. Leptin Regulates Bone Formation via the Sympathetic Nervous System. Cell 2002, 111, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lary, C.W.; Hinton, A.C.; Nevola, K.T.; Shireman, T.I.; Motyl, K.J.; Houseknecht, K.L.; Lucas, F.L.; Hallen, S.; Zullo, A.R.; Berry, S.D.; et al. Association of Beta Blocker Use With Bone Mineral Density in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study: A Cross Sectional Study. JBMR Plus 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Tan, B.; Huang, P. Association of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers use with the risk of fracture in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2025, 36, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Nguyen, N.D.; Eisman, J.A.; Nguyen, T.V. Association between beta-blockers and fracture risk: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Bone 2012, 51, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, D.M.; Seeger, F.H.; Fischer, A.; Roxe, T.; Klotsche, J.; Iekushi, K.; Seeger, T.; Assmus, B.; Honold, J.; Karakas, M.; et al. Elevated levels of the mediator of catabolic bone remodeling RANKL in the bone marrow environment link chronic heart failure with osteoporosis. Circ Heart Fail 2012, 5, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamasaki, S.; Kawakami, A.; Eguchi, K.; Sasaki, H.; Sakai, H. Protein expression and functional difference of membrane-bound and soluble receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand: modulation of the expression by osteotropic factors and cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 275, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-awadh, A.N.; Delgado-Calle, J.; Tu, X.; Kuhlenschmidt, K.; Allen, M.R.; Plotkin, L.I.; Bellido, T. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling induces bone resorption in the adult skeleton by directly regulating the RANKL gene in osteocytes. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yamazaki, M.; Zella, L.A.; Shevde, N.K.; Pike, J.W. Activation of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is mediated through multiple long-range enhancers. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, 6469–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Maeda, K.; Ishihara, A.; Uehara, S.; Kobayashi, Y. Regulatory mechanism of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt signals. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2011, 16, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamme, I.; Ellinghaus, P.; Urrego, D.; Kruger, T. FGF23 expression in rodents is directly induced via erythropoietin after inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor proline hydroxylase. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0186979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszko, K.L.; Brown, S.; Pang, Y.; Huynh, T.; Zhuang, Z.; Pacak, K.; Collins, M.T. C-Terminal, but Not Intact, FGF23 and EPO Are Strongly Correlatively Elevated in Patients With Gain-of-Function Mutations in HIF2A: Clinical Evidence for EPO Regulating FGF23. J Bone Miner Res 2021, 36, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Jeinsen, B.; Sopova, K.; Palapies, L.; Leistner, D.M.; Fichtlscherer, S.; Seeger, F.H.; Honold, J.; Dimmeler, S.; Assmus, B.; Zeiher, A.M.; et al. Bone marrow and plasma FGF-23 in heart failure patients: novel insights into the heart-bone axis. ESC Heart Fail 2019, 6, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilha, S.C.; Bilha, A.; Ungureanu, M.C.; Matei, A.; Florescu, A.; Preda, C.; Covic, A.; Branisteanu, D. FGF23 Beyond the Kidney: A New Bone Mass Regulator in the General Population. Horm Metab Res 2020, 52, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, P. Higher Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Levels Are Causally Associated With Lower Bone Mineral Density of Heel and Femoral Neck: Evidence From Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokomoto-Umakoshi, M.; Umakoshi, H.; Miyazawa, T.; Ogata, M.; Sakamoto, R.; Ogawa, Y. Investigating the causal effect of fibroblast growth factor 23 on osteoporosis and cardiometabolic disorders: A Mendelian randomization study. Bone 2021, 143, 115777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, J. Fibroblast growth factor 23-mediated regulation of osteoporosis: Assessed via Mendelian randomization and in vitro study. J Cell Mol Med 2024, 28, e18551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakova, T.; Cai, X.; Lee, J.; Katz, R.; Cauley, J.A.; Fried, L.F.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Satterfield, S.; Harris, T.B.; Shlipak, M.G.; et al. Associations of FGF23 With Change in Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Risk in Older Individuals. J Bone Miner Res 2016, 31, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erben, R.G.; Soegiarto, D.W.; Weber, K.; Zeitz, U.; Lieberherr, M.; Gniadecki, R.; Moller, G.; Adamski, J.; Balling, R. Deletion of deoxyribonucleic acid binding domain of the vitamin D receptor abrogates genomic and nongenomic functions of vitamin D. Mol Endocrinol 2002, 16, 1524–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odorfer, K.I.; Walter, I.; Kleiter, M.; Sandgren, E.P.; Erben, R.G. Role of endogenous bone marrow cells in long-term repair mechanisms after myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med 2008, 12, 2867–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouxsein, M.L.; Boyd, S.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Guldberg, R.E.; Jepsen, K.J.; Muller, R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res 2010, 25, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erben, R.G.; Glosmann, M. Histomorphometry in Rodents. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1914, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serum parameter | Sham (n=12) | MI (n=12) | P value |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 46.6 ± 3.3 | 50.1 ± 2.7 | 0.41 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 150.3 ± 0.6 | 151.1 ± 4.6 | 0.86 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.10 ± 0.03 | 2.24 ± 0.07 | 0.09 |

| P (mmol/L) | 3.42 ± 0.2 | 3.67 ± 0.3 | 0.48 |

| K (mmol/L) | 4.93 ± 0.4 | 5.93 ± 1 | 0.38 |

| PTHa (pg/ml) | 134.0 ± 18.4 | 149.8 ± 25.07 | 0.65 |

| Parameter | Sham (n=8) | MI (n=7) | P value |

| Femoral metaphysis total BMD (mg/cm3) | 451.9 ± 4.4 | 440.5 ± 6.8 | 0.17 |

| Femoral metaphysis trab. BMD (mg/cm3) | 154.1 ± 7.4 | 151.3 ± 7.8 | 0.8 |

| Femoral shaft total BMD (mg/cm3) | 651.9 ± 6.3 | 644.2 ± 9.0 | 0.5 |

| L4 total BMD (mg/cm3) | 400.6 ± 7.3 | 403.5 ± 4.1 | 0.7 |

| L4 trabecular BMD (mg/cm3) | 239.9 ± 6.1 | 242.1 ± 4.3 | 0.8 |

| L4 cortical BMD (mg/cm3) | 516.2 ± 4.6 | 523.2 ± 4.6 | 0.3 |

| Parameter | Sham (n=7) | TAC (n=9) | P value |

| Bone volume (%) | 4.25 ± 0.55 | 3.81 ± 0.38 | 0.51 |

| Trabecular Thickness (µm) | 26.9 ± 1.1 | 27.9 ± 0.7 | 0.46 |

| Trabecular Separation (µm) | 652.9 ± 68.3 | 763.6 ± 84.6 | 0.35 |

| MAR (µm/day) | 1.35 ± 0.14 | 1.53 ± 0.09 | 0.28 |

| BFR/BS (µm3/µm2/d) | 0.055 ± 0.013 | 0.050 ± 0.008 | 0.74 |

| N.Oc/B.Pm (#/mm) | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.08* | 0.03 |

| Osteoid Width (µm) | 2.13 ± 0.19 | 2.54 ± 0.17 | 0.12 |

| Osteoid maturation time (days) | 1.74 ± 0.28 | 1.72 ± 0.17 | 0.96 |

| Parameter | Sham (n=5-7) | TAC (n=6-9) | P value |

| Bone volume (%) | 25.9 ± 2.2 | 21.4 ± 1.2 | 0.07 |

| Trabecular Thickness (µm) | 49.61 ± 2.2 | 42.83 ± 1.7* | 0.03 |

| Trabecular Separation (µm) | 145.6 ± 9.6 | 158.6 ± 6.1 | 0.25 |

| MAR (µm/day) | 1.75 ± 0.13 | 1.46 ± 0.05 | 0.05 |

| BFR/BS (µm3/µm2/d) | 0.033 ± 0.008 | 0.024 ± 0.012 | 0.57 |

| N.Oc/B. Pm (#/mm) | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 1.16 ± 0.18 | 0.45 |

| Osteoid Width (µm) | 2.54 ± 0.17 | 2.45 ± 0.14 | 0.69 |

| Osteoid maturation time (days) | 1.41 ± 0.11 | 1.74 ± 0.09* | 0.04 |

| Parameter | Sham (n=7-12) | TAC (n=11) | P value |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) | 53.13 ± 2.52 | 61.02 ± 3.27 | 0.65 |

| Na (mmol/L) | 148.3 ± 0.81 | 151.3 ± 0. 87 | 0.02 |

| Ca (mmol/L) | 2.27 ± 0.03 | 2.29 ± 0.04 | 0.67 |

| P (mmol/L) | 2.66 ± 0.18 | 3.13 ± 0.18 | 0.08 |

| K (mmol/L) | 4.39 ± 0.26 | 3.97 ± 0.19 | 0.22 |

| Urinary DPD/Crea (nM/mM) a | 7.62 ± 1.36 | 10.31 ± 1.67 | 0.25 |

| PTH (pg/ml)b | 110 ± 28.4 | 112.3 ± 28.4 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).